Key Points

Clonal signatures of TBD associate with age and the underlying genotype, and are markers of malignant clonal evolution and poor survival.

In contrast to POT1/PPM1D/TERTp mutations, Chr1q+, U2AF1S34, and TP53 somatic mutations are key drivers of cancer development in TBD.

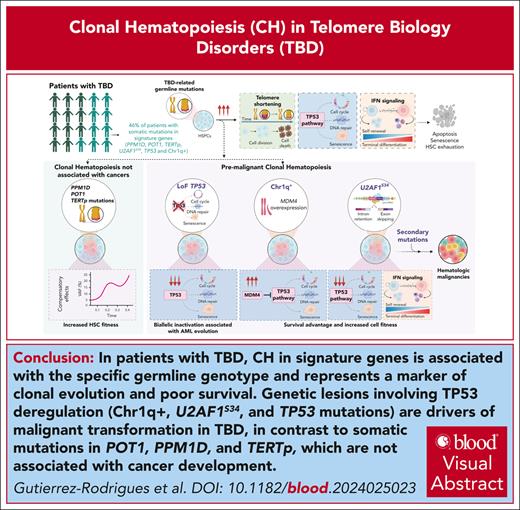

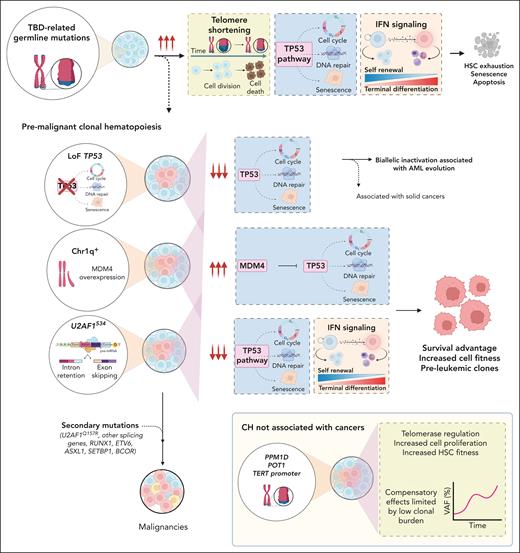

Visual Abstract

Telomere biology disorders (TBDs), caused by pathogenic germ line variants in telomere-related genes, present with multiorgan disease and a predisposition to cancer. Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) as a marker of cancer development and survival in TBDs is poorly understood. Here, we characterized the clonal landscape of a large cohort of 207 patients with TBD with a broad range of age and phenotype. CH occurred predominantly in symptomatic patients and in signature genes typically associated with cancers: PPM1D, POT1, TERT promoter (TERTp), U2AF1S34, and/or TP53. Chromosome 1q gain (Chr1q+) was the commonest karyotypic abnormality. Clinically, multiorgan involvement and CH in TERTp, TP53, and splicing factor genes were associated with poorer overall survival. Chr1q+ and splicing factor or TP53 mutations significantly increased the risk of hematologic malignancies, regardless of clonal burden. Chr1q+ and U2AF1S34 mutated clones were premalignant events associated with the secondary acquisition of mutations in genes related to hematologic malignancies. Similar to the known effects of Chr1q+ and TP53-CH, functional studies demonstrated that U2AF1S34 mutations primarily compensated for aberrant upregulation of TP53 and interferon pathways in telomere-dysfunctional hematopoietic stem cells, highlighting the TP53 pathway as a canonical route of malignancy in TBD. In contrast, somatic POT1/PPM1D/TERTp mutations had distinct trajectories unrelated to cancer development. With implications beyond TBD, our data show that telomere dysfunction is a strong selective pressure for CH. In TBD, CH is a poor prognostic marker associated with worse overall survival. The identification of key regulatory pathways that drive clonal transformation in TBD allows for the identification of patients at a higher risk of cancer development.

Introduction

Inherited bone marrow (BM) failure (BMF) syndromes (IBMFSs) are a group of diseases caused by pathogenic germ line variants (PGVs) that limit the ability of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to self-renew and differentiate.1 Although IBMFSs differ in terms of pathophysiology and clinical phenotypes, they are important causes of germ line cancer predisposition; many IBMFSs have increased risk of both solid and hematologic malignancies.1,2 One of the commonest IBMFSs, telomere biology disorders (TBDs) are caused by PGVs in telomere maintenance genes (TERT, TERC, RTEL1, TINF2, DKC1, PARN, ACD, WRAP53, NHP2, CTC1, NOP10, POT1, NAF1, ZCCHC8, and RPA1) and are characterized by abnormally short and/or dysfunctional telomeres.3,4 TBDs are phenotypically heterogenous, and their clinical manifestations include classical dyskeratosis congenita (DC), BMF, pulmonary and/or liver disease, and increased risk of head/neck squamous cell carcinoma, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).3 Disease phenotype, onset, and severity depend on the particular PGV and the mode of inheritance (autosomal dominant [AD], recessive [AR], X-linked recessive (XLR), or de novo). Patients with AD disease, except for those with germ line TINF2 mutations (classified separately as AD-TINF2 due to distinct disease phenotype), generally have better clinical outcomes.2

Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) is defined by the expansion of cells with somatic mutations or chromosomal abnormalities in blood.5 In IBMFSs, CH compensates for restricted cell fitness caused by PGVs (somatic genetic rescue [SGR]), either directly affecting the associated gene (direct or revertant SGR) or other genes involved in the affected pathway (indirect SGR).6 Although CH may initially be compensatory, it is also associated with the development of hematopoietic cancers.6,7 CH in IBMFS has been characterized in Fanconi anemia,8,9SAMD9/SAMD9L,10 Shwachman-Diamond syndrome,11,12GATA2 deficiency,13 and others.4,7 The biological and clinical relevance of CH in TBDs remains poorly understood because studies have included small cohorts of patients, limiting the identification of genotype-phenotype associations and the discovery of markers of malignant clonal evolution.4,14-19

Here, we investigated the landscape of CH by error-corrected sequencing in a large cohort of patients with TBDs across a broad spectrum of ages, affected genes, and disease phenotypes to provide insights into the role of telomere maintenance in CH development. We dissected the clinical implications of CH to improve the management of patients with TBD-related hematologic malignancies.

Methods

Patient cohort

We retrospectively studied a cohort of 207 patients with TBDs with either a (1) PGV in a telomere-related gene and short/very short telomere length (TL) in total peripheral blood (PB) or PB lymphocytes or (2) an unknown germ line defect but very short TL and strong clinical suspicion for TBD (Table 1; supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website). Patients were seen at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (n = 80), the National Cancer Institute (n = 83), and the University of São Paulo, Ribeirao Preto Medical School (n = 44) from 1997 onward. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants following the Declaration of Helsinki and under protocols approved by the involved institutional review boards (NCT00071045, NCT01328587, NCT01441037, NCT050012111, NCT03312400, NCT00027274, and CAAE 93617018.0.0000.5440).

Characteristics of 207 patients with TBD at first evaluation

| . | All . | Symptomatic patients . | Asymptomatic patients . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | Age, median (range), y . | n (%) . | Age, median (range), y . | AD non-TINF2, n (%) . | AD -TINF2, n (%) . | AR/XLR, n (%) . | Unknown, n (%) . | n (%) . | Age, median (range), y . | AD non-TINF2, n (%) . | AR/XLR, n (%) . | |

| All cohort | 207 | 27 (1-76) | 172 (83) | 27 (1-76) | 94 (45) | 24 (12) | 37 (18) | 17 (8) | 35 (17) | 36 (3-62) | 17 (8) | 18 (9) |

| Females | 91 (44) | 32 (1-72) | 70 (34) | 29 (1-72) | 40 (20) | 9 (9) | 12 (6) | 9 (9) | 21 (10) | 36 (3-62) | 11 (5) | 10 (5) |

| Genotype | ||||||||||||

| TERT | 61 (30) | 38 (3-72) | 52 (25) | 37 (3-72) | 49 (23) | — | 3 (1) | — | 9 (4) | 38 (10-62) | 9 (4) | 0 |

| TERC | 39 (19) | 32 (10-60) | 35 (17) | 33 (12-60) | 35 (17) | — | 0 | — | 4 (2) | 17 (11-60) | 4 (2) | 0 |

| RTEL1 | 37 (18) | 24 (1-75) | 22 (10) | 17 (1-75) | 9 (4) | — | 13 (6) | — | 15 (7) | 35 (3-60) | 3 (1) | 12 (6) |

| TINF2 | 24 (12) | 11 (2-71) | 24 (12) | 11 (2-71) | — | 24 (12) | — | — | 0 | — | — | — |

| DKC1 | 13 (6) | 14 (3-47) | 12 (6) | 13 (3-47) | 0 | — | 12 (6) | — | 1 (0.4) | 27 (27-27) | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| PARN | 8 (4) | 37 (6-53) | 4 (2) | 18 (6-28) | 1 (0.4) | — | 3 (1) | — | 4 (2) | 51 (45-53) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1) |

| CTC1 | 2 (1) | 25 (16-33) | 2 (1) | 25 (16-33) | 0 | — | 2 (1) | — | 0 | — | 0 | 0 |

| ACD | 3 (1.5) | 4 (3-36) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (3-3) | 0 | — | 1 (0.4) | — | 2 (1) | 20 (4-36) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| WRAP53 | 3 (1.5) | 16 (15-32) | 3 (2) | 16 (15-32) | 0 | — | 3 (1.5) | — | 0 | — | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 17 (8) | 29 (2-67) | 17 (10) | 29 (2-68) | — | — | — | 17 (8) | 0 | — | — | — |

| Phenotype at first visit | ||||||||||||

| DC/HH | 59 (28) | 14 (2-48) | 59 (28) | 14 (2-48) | 7 (3) | 18 (9) | 27 (13) | 7 (3) | — | — | — | — |

| Cytopenias | 23 (11) | 27 (8-71) | 23 (11) | 27 (8-71) | 18 (9) | 2 (1) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1) | — | — | — | — |

| MAA/SAA | 29 (14) | 22 (1-66) | 29 (14) | 22 (1-66) | 21 (10) | 2 (1) | 5 (2) | 1 (0.4) | — | — | — | — |

| BMF/PD_LD | 42 (20) | 41 (3-72) | 42 (24) | 41 (3-72) | 31 (33) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 6 (3) | — | — | — | — |

| MDS/AML∗ | 11 (5) | 43 (26-68) | 11 (5) | 43 (26-68) | 9 (9) | — | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | — | — | — | — |

| PD_LD | 8 (4) | 56 (24-75) | 8 (4) | 56 (24-75) | 8 (4) | — | 0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Solid Cancer | 14 (7) | 47 (19-60) | 13 (6) | 47 (20-55) | 8 (4) | — | 4 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 60 (60-60) | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Karyotype at first visit or during follow-up | ||||||||||||

| Abnormal | 26 (12) | 32 (3-68) | 25 (12) | 32 (3-62) | 14 (7) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 1 (0.4) | 4 | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Chr1q+ | 9 (4) | 40 (6-53) | 9 (4) | 40 (6-53) | 7 (3) | — | 2 (1) | — | 0 | — | 0 | 0 |

| –7 | 2 (1) | 48 (27-68) | 2 (1) | 48 (27-68) | 1 (0.4) | — | 1 (0.4) | — | 0 | — | 0 | 0 |

| . | All . | Symptomatic patients . | Asymptomatic patients . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | Age, median (range), y . | n (%) . | Age, median (range), y . | AD non-TINF2, n (%) . | AD -TINF2, n (%) . | AR/XLR, n (%) . | Unknown, n (%) . | n (%) . | Age, median (range), y . | AD non-TINF2, n (%) . | AR/XLR, n (%) . | |

| All cohort | 207 | 27 (1-76) | 172 (83) | 27 (1-76) | 94 (45) | 24 (12) | 37 (18) | 17 (8) | 35 (17) | 36 (3-62) | 17 (8) | 18 (9) |

| Females | 91 (44) | 32 (1-72) | 70 (34) | 29 (1-72) | 40 (20) | 9 (9) | 12 (6) | 9 (9) | 21 (10) | 36 (3-62) | 11 (5) | 10 (5) |

| Genotype | ||||||||||||

| TERT | 61 (30) | 38 (3-72) | 52 (25) | 37 (3-72) | 49 (23) | — | 3 (1) | — | 9 (4) | 38 (10-62) | 9 (4) | 0 |

| TERC | 39 (19) | 32 (10-60) | 35 (17) | 33 (12-60) | 35 (17) | — | 0 | — | 4 (2) | 17 (11-60) | 4 (2) | 0 |

| RTEL1 | 37 (18) | 24 (1-75) | 22 (10) | 17 (1-75) | 9 (4) | — | 13 (6) | — | 15 (7) | 35 (3-60) | 3 (1) | 12 (6) |

| TINF2 | 24 (12) | 11 (2-71) | 24 (12) | 11 (2-71) | — | 24 (12) | — | — | 0 | — | — | — |

| DKC1 | 13 (6) | 14 (3-47) | 12 (6) | 13 (3-47) | 0 | — | 12 (6) | — | 1 (0.4) | 27 (27-27) | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| PARN | 8 (4) | 37 (6-53) | 4 (2) | 18 (6-28) | 1 (0.4) | — | 3 (1) | — | 4 (2) | 51 (45-53) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1) |

| CTC1 | 2 (1) | 25 (16-33) | 2 (1) | 25 (16-33) | 0 | — | 2 (1) | — | 0 | — | 0 | 0 |

| ACD | 3 (1.5) | 4 (3-36) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (3-3) | 0 | — | 1 (0.4) | — | 2 (1) | 20 (4-36) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| WRAP53 | 3 (1.5) | 16 (15-32) | 3 (2) | 16 (15-32) | 0 | — | 3 (1.5) | — | 0 | — | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 17 (8) | 29 (2-67) | 17 (10) | 29 (2-68) | — | — | — | 17 (8) | 0 | — | — | — |

| Phenotype at first visit | ||||||||||||

| DC/HH | 59 (28) | 14 (2-48) | 59 (28) | 14 (2-48) | 7 (3) | 18 (9) | 27 (13) | 7 (3) | — | — | — | — |

| Cytopenias | 23 (11) | 27 (8-71) | 23 (11) | 27 (8-71) | 18 (9) | 2 (1) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1) | — | — | — | — |

| MAA/SAA | 29 (14) | 22 (1-66) | 29 (14) | 22 (1-66) | 21 (10) | 2 (1) | 5 (2) | 1 (0.4) | — | — | — | — |

| BMF/PD_LD | 42 (20) | 41 (3-72) | 42 (24) | 41 (3-72) | 31 (33) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 6 (3) | — | — | — | — |

| MDS/AML∗ | 11 (5) | 43 (26-68) | 11 (5) | 43 (26-68) | 9 (9) | — | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | — | — | — | — |

| PD_LD | 8 (4) | 56 (24-75) | 8 (4) | 56 (24-75) | 8 (4) | — | 0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Solid Cancer | 14 (7) | 47 (19-60) | 13 (6) | 47 (20-55) | 8 (4) | — | 4 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 60 (60-60) | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Karyotype at first visit or during follow-up | ||||||||||||

| Abnormal | 26 (12) | 32 (3-68) | 25 (12) | 32 (3-62) | 14 (7) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 1 (0.4) | 4 | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Chr1q+ | 9 (4) | 40 (6-53) | 9 (4) | 40 (6-53) | 7 (3) | — | 2 (1) | — | 0 | — | 0 | 0 |

| –7 | 2 (1) | 48 (27-68) | 2 (1) | 48 (27-68) | 1 (0.4) | — | 1 (0.4) | — | 0 | — | 0 | 0 |

Frequencies were calculated based on the total number of patients (n = 207).

AR/XLR, autosomal recessive or X-linked recessive; DC/HH, classical DC or Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome; SAA/MAA, severe or moderate aplastic anemia; BMF/PD_LD, both bone marrow failure and lung or liver disease; MDS/AML, myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myeloid leukemia; Chr, chromosome; –7, partial deletion of chromosome 7 or monosomy 7.

18 patients developed MDS/AML, including 11 with MDS/AML in the absence of the clinical triad at assessment, 2 with DC/HH and MDS/AML at assessment, and 5 with BMF that evolved during follow-up.

TL measurement and germ line testing

All included patients had short (<10th percentile of age-matched healthy individuals) or very short (less than first percentile) telomeres in PB lymphocytes or total leukocytes. TL was measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction and/or Southern blot analysis (in cases before 2013)20 or by flow–fluorescent in situ hybridization (Flow-FISH) performed either by Repeat Diagnostics (Vancouver, CA) or as previously described.20 For deep characterization of TL in TINF2 patients, we performed the specific telomere shortest length assay (TeSLA) using the total DNA of patients with available samples, as previously described.21

PGVs in telomere-related genes were identified in PB by whole-exome sequencing, targeted panels, or Sanger sequencing from 1997 onward, as previously described.2,22 All variants were systematically curated using the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and gene-specific criteria.2,22,23 Except for 2 patients harboring the POT1P146L variant of uncertain significance and 15 patients with unknown molecular defects, patients included in the study had germ line variants curated as pathogenic/likely pathogenic (supplemental Table 1).

Clinical assessment and scoring

For analysis, patients were grouped into different disease categories including classical DC or Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome (DC/HH), BMF alone with either severe aplastic anemia (SAA), moderate AA (MAA) or isolated cytopenias, MDS/AML, isolated pulmonary or liver disease (PD_LD), or both BMF and pulmonary or liver disease (BMF/PD_LD; Table 1; supplemental Table 2). To better characterize multiorgan involvement in TBDs and evaluate its correlation with cytopenia, we systematically scored patients from 0 to 6 based on the number of organ systems affected (skin, liver, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, vascular, and solid cancer development; supplemental Table 3).

DNA sequencing

Error-correcting sequencing (ECS) with a customized panel covering myeloid-cancer and telomere-related genes was used to retrospectively sequence patients’ PB, collected at diagnosis or the first visit, for somatic mutations at minimum variant allele frequency (VAF) of 0.5% (ArcherDX; supplemental Table 4). Similar ECS data derived from 140 age-matched healthy individuals were used as controls. De novo variants (VAF ≥0.5%) identified at any time point were tracked in available serial samples and retrospectively included in the analysis if detectable at VAF ≥0.1%. Clonal architectures were assessed by single-cell proteogenomic sequencing in available samples from 6 patients using the Mission Bio Tapestri platform protocol, as previously described.24 Single-cell proteogenomic sequencing data derived from healthy donors were used as a reference for immunophenotypic cluster analysis based on the expression of 45 protein surface markers, as previously described.24

Single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing

To dissect the functional role of U2AF1S34 on telomere-dysfunctional HSCs, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis in primary BM samples from patients with TERT or TERC mutations that were obtained from the Department of Leukemia at MD Anderson Cancer Center (patient IDs MDA-3 and MDA-19) or from National Institutes of Health (patient ID NIH-39). CD34+ cells were isolated from BM mononuclear cells as previously described.25 First, 5’ single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) analysis was performed to dissect the differential expression profile of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) harboring the U2AF1S34 mutation compared with wild-type HSPCs in BM samples from NIH-39; in this assay, the genotype of RNA transcripts was successfully identified because the mutation was near to the 5’ region. The functional impact of U2AF1S34 mutations was validated in HSPCs from TERT patients without CH overexpressing the U2AF1S34 or the U2AF1wild-type allele after lentivirus transduction. Transduced CD34+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry based on green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression and processed for 3’ scRNA-seq or bulk RNA-seq analyses. Full details are included in the supplemental Data File.

Statistics and reproducibility

For outcome analysis, patients were classified into 6 groups depending on the type of recurrent somatic mutations: those with splicing factor gene mutations (U2AF1, ZRSR2, SF3B1, and SRSF2 [n = 23]), TP53 mutations (n = 6), cytogenetic aberrations involving chromosome 1q gain (Chr1q+; n = 9); and those only with TERT promoter (TERTp; n = 15), PPM1D (n = 21), or POT1 or TINF2 somatic mutations (n = 17). Survival probabilities, censored for hematopoietic cell transplant, were calculated from the date of first visit or diagnosis using the Kaplan-Meier estimates and the Cox proportional hazard models. When comparing time-to-event distributions, the log-rank test was used to determine statistical significance. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate CH associations with clinical outcomes.

Results

General characteristics of the cohort

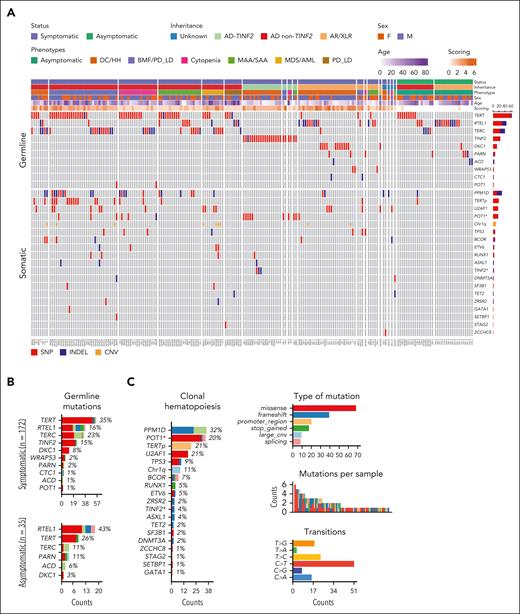

Most patients had an identified genetic cause of their TBD (190/207 [92%]) in TERT, TERC, RTEL1, TINF2, or DKC1 (Figure 1A; Table 1; supplemental Table 1). At disease presentation, most patients were symptomatic (n = 172 [83%]): 59 (34%) had classical DC/HH, 52 (30%) had BMF alone, 42 (24%) had BMF with lung or liver involvement, and 8 (5%) had PD_LD alone (Table 1). Most patients (128/172; 75%) had a system-based score of 1 or 2 (n = 107 [62%]) or >2 (n = 21 [12%]; Figure 1A) (supplemental Table 1). Inheritance patterns included AD non-TINF2 (n = 94 [45%]), AD-TINF2 (n = 24 [12%]), or AR/XLR (n = 37 [18%]). Thirty-five individuals, primarily relatives of clinically affected patients, were asymptomatic and harbored heterozygous AD (n = 18 [9%]) or AR/XLR variants of variable penetrance (n = 17 [8%]), mainly in TERT (n = 9 [26%]) and RTEL1 (n = 15 [43%]; Figure 1B). Although patients’ median age was 27 years (range, 1-76), disease manifestations such as DC/HH, BMF, and pulmonary and/or liver disease occurred in younger, middle-aged, and older patients, respectively (Table 1; supplemental Figure 1A).

The genetic landscape of 207 patients with TBD. (A) An OncoPrint plot of somatic alterations detected in 207 patients with TBD based on patients’ clinical characteristics at the time of diagnosis or first visit. The number of mutations in each gene is shown on the left side of the graph. Most patients were symptomatic, but 35 patients were asymptomatic, including 2 who had isolated findings that did not meet the criteria for disease categories used in the study (isolated mucocutaneous findings and esophageal cancer). (B) The number of PGVs in TBD-related genes based on disease status. The frequency of mutations is also shown according to the affected gene. (C) CH in patients with TBD (n = 207). The top mutated genes and frequency of mutations, the type of mutation allelic transition, and the number of mutations per patient are shown in the figure. Somatic variants were primarily missense, median number of variants per patient was 1, and mutational signatures were mainly C→T/A. Clonal profiles were derived from symptomatic patients (only 1 asymptomatic patient had CH involving PPM1D and TERTp). (D) Somatic and germ line gene-gene interactions showing the mutually exclusive or co-occurring set of mutated genes. Significant interactions by the pair-wise Fisher exact test are depicted by asterisks (P < .05). Both somatic mutations and PGVs were found in POT1 and TINF2; POT1Δ and TINF2Δ refer to sets of somatic mutations in these genes. Genomic plots were generated using the Maftools package. (E) VAF of somatic mutations identified in PB. Boxes indicate VAF frequencies and ranges relative to each mutated gene. Centerline, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles. PPM1D, TERTp, and POT1 mutations were mostly found at a median VAF of 1% (range, 0.5%-18%), 4% (range, 0.8%-32%), and 2% (range, 0.5%-39%), respectively. In contrast, U2AF1 and other MDS/AML-related mutations, mostly in splicing factors, were found at a median VAF of 11% (range, 0.8%-46%) and 4% (range, 0.5%-31%), respectively. Somatic mutations identified in patients with MDS/AML are highlighted in red. (F) Linear representations of signature CH genes mutated in our cohort. Blue and red circles represent missense and nonsense/frameshifts or splicing variants, respectively.

The genetic landscape of 207 patients with TBD. (A) An OncoPrint plot of somatic alterations detected in 207 patients with TBD based on patients’ clinical characteristics at the time of diagnosis or first visit. The number of mutations in each gene is shown on the left side of the graph. Most patients were symptomatic, but 35 patients were asymptomatic, including 2 who had isolated findings that did not meet the criteria for disease categories used in the study (isolated mucocutaneous findings and esophageal cancer). (B) The number of PGVs in TBD-related genes based on disease status. The frequency of mutations is also shown according to the affected gene. (C) CH in patients with TBD (n = 207). The top mutated genes and frequency of mutations, the type of mutation allelic transition, and the number of mutations per patient are shown in the figure. Somatic variants were primarily missense, median number of variants per patient was 1, and mutational signatures were mainly C→T/A. Clonal profiles were derived from symptomatic patients (only 1 asymptomatic patient had CH involving PPM1D and TERTp). (D) Somatic and germ line gene-gene interactions showing the mutually exclusive or co-occurring set of mutated genes. Significant interactions by the pair-wise Fisher exact test are depicted by asterisks (P < .05). Both somatic mutations and PGVs were found in POT1 and TINF2; POT1Δ and TINF2Δ refer to sets of somatic mutations in these genes. Genomic plots were generated using the Maftools package. (E) VAF of somatic mutations identified in PB. Boxes indicate VAF frequencies and ranges relative to each mutated gene. Centerline, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles. PPM1D, TERTp, and POT1 mutations were mostly found at a median VAF of 1% (range, 0.5%-18%), 4% (range, 0.8%-32%), and 2% (range, 0.5%-39%), respectively. In contrast, U2AF1 and other MDS/AML-related mutations, mostly in splicing factors, were found at a median VAF of 11% (range, 0.8%-46%) and 4% (range, 0.5%-31%), respectively. Somatic mutations identified in patients with MDS/AML are highlighted in red. (F) Linear representations of signature CH genes mutated in our cohort. Blue and red circles represent missense and nonsense/frameshifts or splicing variants, respectively.

The clonal landscape of TBDs

At the first clinic visit, 80 of the 172 symptomatic patients (46%) had 1 (n = 43 [54%]) or ≥ 2 somatic mutations (n = 37 [46%]) in PB, recurrently in PPM1D, POT1, TERTp, U2AF1, or TP53 (Figure 1A-C; supplemental Table 1). CH was present in only one asymptomatic patient (Figure 1A). Abnormal karyotypes were present in 26 of 207 patients (13%; 1 asymptomatic) and mainly involved Chr1q+ (n = 9 [35%]). Partial or complete deletion of chromosome 7 was detected in 2 of 26 patients (8%). Complex karyotype was present in 4 patients, 2 of whom had AML (supplemental Table 5).

Somatic mutations associated with specific germ line genetic defects (supplemental Figure 2). CH in TERTp and PPM1D was enriched in TERT patients, whereas POT1-CH was highly enriched in TINF2 patients (P < .05; Figure 1D). Patients with TINF2 PGVs also harbored TINF2 somatic mutations (TINF2-CH), previously shown to functionally compensate the effects of the TINF2 germ line mutation.26 Somatic mutations in splicing factor genes and TERTp were associated with AD non-TINF2 and AR/XLR diseases but were not detected in those with AD-TINF2 diseases. CH sporadically occurred in TBD patients with PGVs in RTEL1, ACD, CTC1, WRAP53, and PARN (n = 11 [14%]; Figure 1A). Typical age-related CH in DNMT3A and TET2 was only seen in 3 patients (median age, 38 years [range, 32-76]).

The median VAF of CH mutations in PB samples followed a bimodal distribution. PPM1D, TERTp, and POT1 mutations had lower VAFs (0.5%-4%) than U2AF1 and other MDS-related gene mutations (≥5%-10%; Figure 1E). All recurrent CH mutations detected in our cohort were typical of cancers and have been previously functionally validated for oncogenicity by others (Figure 1F). PPM1D mutations were all exon 6 truncations, which are known to inhibit TP53 activation, enhance HSCs' competitive fitness, and suppress the DNA damage response.27,28POT1 mutations located at the oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding fold domain are loss-of-function because they negatively regulate telomerase and increase cell proliferation and telomere elongation.29,30 All TERTp mutations were at positions –57, –124, and –146 and have been shown to activate telomerase expression.31U2AF1 mutations almost exclusively occurred at the hot spot S34. Only 2 patients had the hot spot Q157R mutation, which co-occurred with Chr1q+. Chr1q+ is also known to be oncogenic because it leads to MDM4 upregulation, which downregulates TP53 signaling and confers HSC proliferative advantage.9

Clinical associations of CH

Intrinsically connected to the specific germ line defect, distinct phenotypes and aging were also associated with CH (supplemental Table 6). CH incidence in TBDs was significantly higher than in age-matched healthy individuals (Figure 2A). The frequency of TERTp¸ splicing factors, and PPM1D mutations increased with patients’ age and were rare in pediatric cases (supplemental Figure 1B; supplemental Table 6). POT1/TINF2-CH correlated with DC/HH (odds ratio [OR] and 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 3.6 [1.3-10.2]), mainly due to co-occurrence with germ line TINF2 mutations (supplemental Tables 6 and 7). TERTp-CH frequently co-occurred with mutations in PPM1D, and both mutations correlated with BMF and multiorgan involvement (OR [95% CI], 10 [3.2-31]; and OR [95% CI], 2.8 [1.06-7.2], respectively). CH in splicing factor genes (OR [95% CI], 13.5 [3.7-49]) or Chr1q+ (OR [95% CI], 22 [4.8-99]) was associated with the development of MDS/AML (supplemental Table 7). Clinically, CH in splicing factors and Chr1q+ was associated with multiorgan involvement (higher system-based score; supplemental Figure 3), which correlated with progressive cytopenias (supplemental Figure 4). CH in splicing factors and POT1 strongly correlated with thrombocytopenia, independent of patients’ age (supplemental Table 8).

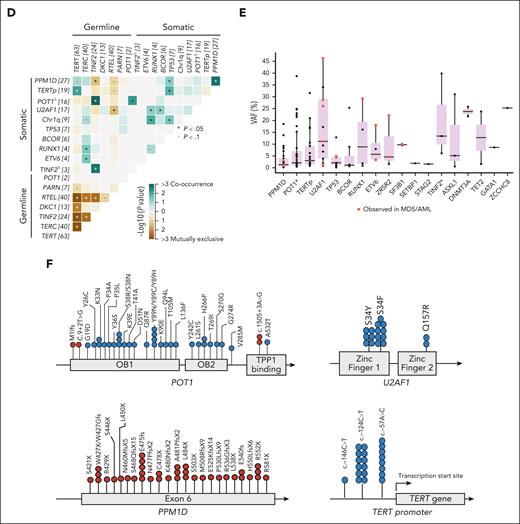

Clinical correlations with CH. (A) CH frequency (at minimum VAF of 0.5%) relative to age ranges in 207 patients with TBD (red curve) and 140 age-matched healthy donors (HDs; blue curve) screened using the same panel. CH frequency in TBDs at any age range was higher than that in HD (age 0-20 years, 22% vs 0 [P = .0359]; 21-40 years, 44% vs 4% [P = .0001]; 41-70 years, 55% vs 16% [P < .001]; >70 years, 75% vs 42% [P = .31]). (B) Kaplan-Meier curves of cumulative survival probabilities relative to the entire TBD cohort (n = 207; black curve) and disease inheritance (unknown inheritance mode [blue curve], AD-TINF2; [green curve], AD non-TINF2 [red curve], and recessive or X-linked recessive [AR/XLR; pink curve]). Survival probabilities were analyzed from patient’s date of birth. The log-rank test was used to determine statistical significance (P < .05). (C) Kaplan-Meier curves of cumulative survival probabilities based on CH types. Survival probabilities were calculated from the time of the first visit. Patients who underwent hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) were censored at the date of transplant. The log-rank test was used to determine statistical significance (P < .05). (D) Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression for OS. Variables selected by the stepwise model are shown on the right. (E) Cumulative incidence of MDS/AML in the entire cohort based on patient age (left) and the germ line mutated gene (right). Time to MDS/AML development was calculated from the time of the first visit. (F) Kaplan-Meier curves of cumulative incidence of MDS/AML in the entire cohort based on the CH types. Survival probabilities were calculated from the time of the first visit. Patients who underwent HCT were censored at the date of transplant. The log-rank test was used to determine statistical significance (P < .05). (G) Risk of MDS/AML development determined by multivariate stepwise Cox proportional hazards regression. Variables selected by the model are shown in the figure. (H) Association between CH and solid cancer development determined by multivariate logistic regression. ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; Hb, hemoglobin.

Clinical correlations with CH. (A) CH frequency (at minimum VAF of 0.5%) relative to age ranges in 207 patients with TBD (red curve) and 140 age-matched healthy donors (HDs; blue curve) screened using the same panel. CH frequency in TBDs at any age range was higher than that in HD (age 0-20 years, 22% vs 0 [P = .0359]; 21-40 years, 44% vs 4% [P = .0001]; 41-70 years, 55% vs 16% [P < .001]; >70 years, 75% vs 42% [P = .31]). (B) Kaplan-Meier curves of cumulative survival probabilities relative to the entire TBD cohort (n = 207; black curve) and disease inheritance (unknown inheritance mode [blue curve], AD-TINF2; [green curve], AD non-TINF2 [red curve], and recessive or X-linked recessive [AR/XLR; pink curve]). Survival probabilities were analyzed from patient’s date of birth. The log-rank test was used to determine statistical significance (P < .05). (C) Kaplan-Meier curves of cumulative survival probabilities based on CH types. Survival probabilities were calculated from the time of the first visit. Patients who underwent hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) were censored at the date of transplant. The log-rank test was used to determine statistical significance (P < .05). (D) Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression for OS. Variables selected by the stepwise model are shown on the right. (E) Cumulative incidence of MDS/AML in the entire cohort based on patient age (left) and the germ line mutated gene (right). Time to MDS/AML development was calculated from the time of the first visit. (F) Kaplan-Meier curves of cumulative incidence of MDS/AML in the entire cohort based on the CH types. Survival probabilities were calculated from the time of the first visit. Patients who underwent HCT were censored at the date of transplant. The log-rank test was used to determine statistical significance (P < .05). (G) Risk of MDS/AML development determined by multivariate stepwise Cox proportional hazards regression. Variables selected by the model are shown in the figure. (H) Association between CH and solid cancer development determined by multivariate logistic regression. ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; Hb, hemoglobin.

Irrespective of VAF, CH mutations, including those in POT1 known to be associated with telomere elongation in cancer cells,30 did not correlate with improved blood counts or longer telomeres in lymphocytes or total leukocytes (measured by flow-FISH). These results were confirmed by TeSLA using total DNA available from patients with germ line TINF2 mutations and multiple somatic mutations in POT1. Even a high cumulative burden of POT1-CH (>20%) did not change the distribution or length of telomeres (supplemental Figure 5). However, POT1-CH with a cumulative VAF >20% did correlate with an atypical DC phenotype, notable for the absence of the classical mucocutaneous triad, older age at symptom onset, and stable TL in serial analysis (supplemental Table 9; supplemental Figure 5).

CH, survival, and association with cancer

For the entire cohort, overall survival (OS) was 73% at age 40 years and worse for patients with AD-TINF2 or AR/XLR disease (P < .05; Figure 2B). Somatic mutations in TERTp, splicing factors genes, and TP53, as well as a higher system-based score, were associated with lower OS, independent of patient age and inheritance mode (Figures 2C-D; supplemental Figures 6-7; supplemental Table 10).

Eighteen of 207 patients (9%; 14 with MDS and 4 with AML) developed myeloid malignancies (supplemental Tables 11-12) at a median age of 40 years (range, 6-68) and a cumulative incidence of 8.6% at age 40 years. Patients with DKC1, TERC, or TERT PGVs had the highest risk of malignant transformation (cumulative incidence of 36%, 16%, and 5.3% at age 40 years, respectively [P = .001]; Figure 2E; supplemental Figure 8). Abnormal karyotypes were reported in 8 patients with MDS/AML at presentation (mainly Chr1q+; n = 4). An increased risk of MDS/AML development was significantly associated with Chr1q+ (cumulative incidence at 5 years from the initial visit of 47%), splicing factor genes (5-year cumulative incidence of 39%) or TP53 mutations (5-year cumulative incidence of 14%), independent of age (Figure 2F-G; supplemental Table 13). CH in TERTp or POT1 was not detected in patients with MDS/AML. Similar results were observed when data were analyzed by inheritance mode (supplemental Figure 9A). U2AF1S34 mutations were dominant clonal events that alone resulted in lower OS and increased risk of MDS/AML by the univariate Cox proportional model (5-year cumulative incidence of 28%; Figure 2F; supplemental Figure 9B).

Solid tumors were diagnosed in 14 patients (7%) at a median age of 48 years (range, 20-61); most frequent were head/neck squamous cell carcinoma (43%), followed by gastrointestinal (21%) and gynecologic cancers (21%; supplemental Table 14). When assessing patients with a known cancer diagnosis date (10 of 14), the cumulative incidence of solid cancers at age 40 years was 3.9%. Older age and TP53 mutations in PB were independently associated with solid cancer (OR [95% CI] of 1.05 [1-1.09] and 14.24 [1.7-118], respectively; P < .05; Figure 2H; supplemental Table 15). In contrast to CH in PPM1D/TERTp/POT1, U2AF1S34 and TP53 mutations as well as Chr1q+ were mutually exclusive events associated with malignancy development, often co-occurring with subclonal MDS-related mutations (Figure 3A).

Clonal hierarchies and dynamics. (A) Co-occurrence of CH associated with an increased risk of MDS/AML development. A Venn diagram shows the number of patients with Chr1q+, U2AF1S34, and TP53 mutations (left). Chr1q+ and U2AF1S34 or TP53 mutations were mutually exclusive in patients who developed malignancies (MDS, AML, or squamous cell carcinoma [SCC]). A patient with Coats plus syndrome had both TP53 and U2AF1S34 mutations without developing cancer (NIH-47). A graph shows the co-occurrence of Chr1q+ and U2AF1S34 with somatic mutations in other MDS-related genes (right). Chr1q+ and U2AF1S34 were always dominant clones, as a measure of VAF (right). Somatic mutations in other MDS-related genes, mainly in RUNX1, ETV6, and splicing factors, were likely subclonal. In contrast to U2AF1S34, all patients with Chr1q+ and CH in MDS-related genes developed MDS. TP53 mutations rarely co-occurred with somatic mutations in other MDS-related genes. (B) Clonal hierarchies defined by scDNA-seq analysis (left) and longitudinal analysis of mutant clones in granulocytes or total PB defined by bulk ECS (right) in 2 patients with multiple PPM1D or POT1 mutations (NIH-33 and BR-01). NIH-33 (MAA and liver disease at the age of 12) and BR-01 (MAA at age 18 years) had developed no malignancy at the last follow-up and are alive. ∗indicates PPM1D VAF in total PB from NIH-33; ∗∗indicates PPM1D VAF in PB mononuclear cells from NIH-33. An orange bar indicates the time NIH-33 was under low-dose danazol treatment. (C-D) Clonal hierarchies defined by scDNA-seq analysis (left) and longitudinal analysis of mutant clones in total PB defined by bulk ECS (right) in 3 patients with U2AF1S34 mutations (NIH-02, NIH-21, and NIH-39) (C) and in 1 patient with Chr1q+ and U2AF1Q157R mutation (NIH-11) (D). Blue and orange bars indicate the times when patients were under regular-dose or low-dose danazol treatment, respectively. NIH-21 (MAA and liver disease at the age 60 years) and NIH-39 (mild cytopenias at the age 26 years) had the U2AF1S34 mutation at VAF >20% in PB but no MDS/AML at the last follow-up. In contrast, NIH-02 (MAA and pulmonary fibrosis at the age of 39) developed MDS 2 years after the initial screening, and NIH-11 (MDS at the age 54 years), with a detectable Chr1q+ and U2AF1Q157R mutation at assessment, evolved to MDS with an excess of blasts (MDS-EB) and AML at 5.5 years of follow-up and died. Single-cell proteogenomic analysis evidenced that AML evolution coincided with the emergence of a KRAS mutation and monosomy 7 in CD34+ HSC clones harboring the Chr1q+ and U2AF1Q157R mutations (supplemental Figure 16). D, dominant clone; MAA, moderate aplastic anemia; S, subclonal clone; scDNA-seq, single-cell proteogenomic sequencing.

Clonal hierarchies and dynamics. (A) Co-occurrence of CH associated with an increased risk of MDS/AML development. A Venn diagram shows the number of patients with Chr1q+, U2AF1S34, and TP53 mutations (left). Chr1q+ and U2AF1S34 or TP53 mutations were mutually exclusive in patients who developed malignancies (MDS, AML, or squamous cell carcinoma [SCC]). A patient with Coats plus syndrome had both TP53 and U2AF1S34 mutations without developing cancer (NIH-47). A graph shows the co-occurrence of Chr1q+ and U2AF1S34 with somatic mutations in other MDS-related genes (right). Chr1q+ and U2AF1S34 were always dominant clones, as a measure of VAF (right). Somatic mutations in other MDS-related genes, mainly in RUNX1, ETV6, and splicing factors, were likely subclonal. In contrast to U2AF1S34, all patients with Chr1q+ and CH in MDS-related genes developed MDS. TP53 mutations rarely co-occurred with somatic mutations in other MDS-related genes. (B) Clonal hierarchies defined by scDNA-seq analysis (left) and longitudinal analysis of mutant clones in granulocytes or total PB defined by bulk ECS (right) in 2 patients with multiple PPM1D or POT1 mutations (NIH-33 and BR-01). NIH-33 (MAA and liver disease at the age of 12) and BR-01 (MAA at age 18 years) had developed no malignancy at the last follow-up and are alive. ∗indicates PPM1D VAF in total PB from NIH-33; ∗∗indicates PPM1D VAF in PB mononuclear cells from NIH-33. An orange bar indicates the time NIH-33 was under low-dose danazol treatment. (C-D) Clonal hierarchies defined by scDNA-seq analysis (left) and longitudinal analysis of mutant clones in total PB defined by bulk ECS (right) in 3 patients with U2AF1S34 mutations (NIH-02, NIH-21, and NIH-39) (C) and in 1 patient with Chr1q+ and U2AF1Q157R mutation (NIH-11) (D). Blue and orange bars indicate the times when patients were under regular-dose or low-dose danazol treatment, respectively. NIH-21 (MAA and liver disease at the age 60 years) and NIH-39 (mild cytopenias at the age 26 years) had the U2AF1S34 mutation at VAF >20% in PB but no MDS/AML at the last follow-up. In contrast, NIH-02 (MAA and pulmonary fibrosis at the age of 39) developed MDS 2 years after the initial screening, and NIH-11 (MDS at the age 54 years), with a detectable Chr1q+ and U2AF1Q157R mutation at assessment, evolved to MDS with an excess of blasts (MDS-EB) and AML at 5.5 years of follow-up and died. Single-cell proteogenomic analysis evidenced that AML evolution coincided with the emergence of a KRAS mutation and monosomy 7 in CD34+ HSC clones harboring the Chr1q+ and U2AF1Q157R mutations (supplemental Figure 16). D, dominant clone; MAA, moderate aplastic anemia; S, subclonal clone; scDNA-seq, single-cell proteogenomic sequencing.

Clonal dynamics, trajectories, and development of myeloid neoplasia

To determine clonal trajectories in TBDs, we performed single-cell proteogenomic analyses in available samples from patients with multiple somatic mutations in PPM1D (NIH-33), POT1 (BR-01), and U2AF1S34 (NIH-02, NIH-21, and NIH-39). Branched trajectories with CH found in independent clones were observed in patients with PPM1D and POT1 mutations (Figure 3B). In both patients, CH was selected at the HSC level and enriched in myeloid cells but also detected in up to 50% of B, natural killer, and T cells (supplemental Figures 10 and 11). In contrast, U2AF1S34 mutations were always driver mutations associated with linear trajectories of successive acquisition of other MDS-related mutations in the same clone, even without MDS/AML development (NIH-21 and NIH-39; Figure 3C). Despite their myeloid bias, these mutations were also present in B, natural killer, and T cells at variable ranges (up to 11% of genotyped cells; supplemental Figures 12-14).

Bulk ECS analysis in longitudinal PB samples from an additional cohort of 17 patients with CH showed that the clonal dynamics were largely stable, regardless of androgen treatment (median follow-up, 3 years [range, 0.5-13]; supplemental Figure 15; supplemental Table 16). Only 2 patients clonally evolved during follow-up: BR-22 developed AML with TP53 loss of heterozygosity; and NIH-11 progressed to MDS with excess blasts, with the emergence of a KRAS mutation and monosomy 7 (Figure 3D; supplemental Figure 15). Multiomics and copy-number variation analysis of single BM cells from NIH-11 showed that Chr1q+, trisomy 8, and U2AF1Q157R in CD34+ HSCs preceded the linear acquisition of monosomy 7 and KRASG12V mutation at the time of AML evolution (supplemental Figure 16).

Mechanisms underlying malignant clonal evolution

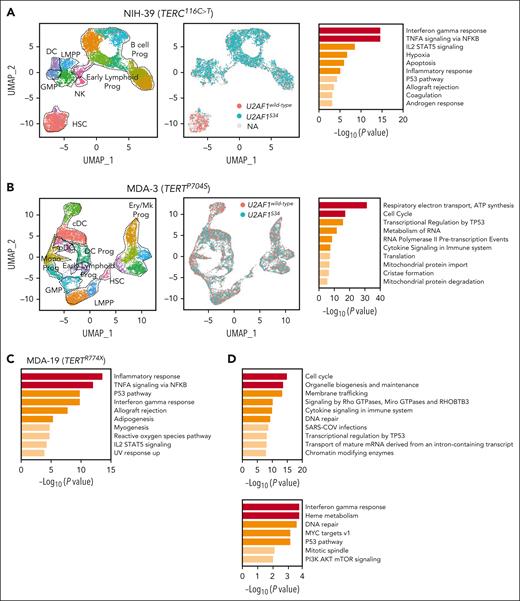

In contrast to other genes known to promote tumorigenesis through the modulation of pathways involved in telomere maintenance, the mechanisms underlying recurrent U2AF1S34 selection in TBDs were unknown. To better understand why U2AF1S34 mutations drive MDS initiation in TBDs, we performed scRNA-seq analysis in CD34+ HSPCs from a patient with a TERC PGV and without MDS who acquired a somatic U2AF1S34F mutation (NIH-39). Consistent with proteogenomic data (supplemental Figure 14), 5’ scRNA-seq analysis of CD34+ HSPCs showed that the U2AF1S34F mutations arose in early HSCs and propagated downstream in progenitor cells (Figure 4A; supplemental Figure 17A). Compared with U2AF1wild-type, early-primed U2AF1S34F HSPCs (HSCs, granulocyte-monocyte progenitors, and lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors) showed significant downregulation of genes involved in interferon (IFN) and TP53 signaling pathways (supplemental Table 17), a hallmark transcriptional signature of HSCs from patients with TBDs known to drive telomere dysfunctional HSC exhaustion.32,33 These results were further validated by long-read RNA-seq analysis (supplemental Figure 17B-C; supplemental Table 18). In vitro colony assays followed by colony genotyping showed that most myeloid colonies were U2AF1S34F mutated (supplemental Figure 17D).

RNA-seq analyses in HSPCs from patients with TBD and somatic U2AF1S34 mutations. (A) UMAP plots of 5’ scRNA-seq analysis in CD34+ HSPCs isolated from NIH-39 harboring a germ line TERC r.116C>T mutation and a somatic U2AF1S34 mutation (n = 3912 cells). Each dot represents 1 cell. Different colors indicate cluster identity (left) and the U2AF1S34 mutational status (center). Pathway enrichment analysis of genes significantly downregulated in U2AF1S34 mutant HSPCs compared with U2AF1wild-type HSPCs (P adj ≤ .05). Hallmark gene sets are shown (right). Dotted lines indicate the annotated lineage clusters. (B) UMAP plots of the 3’ scRNA-seq analysis in CD34+ HSPCs isolated from an asymptomatic patient with TBD with a pathogenic TERT p.P704S germ line mutation (MDA-3) transduced with lentiviral vectors carrying the wild-type or mutant U2AF1 allele after in vitro culture for 3 days (n = 13 674 cells). Each dot represents 1 cell. Different colors indicate cluster identity (left) and the U2AF1 mutational status (middle). Pathway enrichment analysis of genes significantly downregulated in U2AF1S34-transduced HSCs compared with those in U2AF1wild type-transduced HSCs (P ≤.01). Reactome gene sets are shown (right). Dotted lines indicate the annotated lineage clusters. (C) Pathway enrichment analysis of genes significantly downregulated in U2AF1S34-transduced CD34+ cells compared with those in U2AF1wild type -transduced CD34+ cells from another asymptomatic patient with TBD with short telomeres harboring the TERT p.R774X pathogenic mutation (MDA-19). Cells were transduced with lentiviral vectors carrying the mutant or wild-type U2AF1 allele, and after in vitro culture for 3 days, bulk RNA-seq analysis was performed (P adj ≤ .001; fold change <1). Hallmark gene sets are shown. (D) Pathway enrichment analysis from bulk RNA-seq showing the genes that underwent aberrant exon skipping (top) and intron retention (bottom) in U2AF1S34 HSPCs compared with U2AF1wild type HSPCs from panel C (P adj ≤ .05). Reactome gene sets are shown. cDCs, classic dendritic cells; DCs, dendritic cells; Ery, erythroid; GMP, granulocytic-monocytic progenitors; LMPP, lymphoid-myeloid primed progenitors; Mk, megakaryocytic; Mono, monocytic; NK, natural killer cells; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cells; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

RNA-seq analyses in HSPCs from patients with TBD and somatic U2AF1S34 mutations. (A) UMAP plots of 5’ scRNA-seq analysis in CD34+ HSPCs isolated from NIH-39 harboring a germ line TERC r.116C>T mutation and a somatic U2AF1S34 mutation (n = 3912 cells). Each dot represents 1 cell. Different colors indicate cluster identity (left) and the U2AF1S34 mutational status (center). Pathway enrichment analysis of genes significantly downregulated in U2AF1S34 mutant HSPCs compared with U2AF1wild-type HSPCs (P adj ≤ .05). Hallmark gene sets are shown (right). Dotted lines indicate the annotated lineage clusters. (B) UMAP plots of the 3’ scRNA-seq analysis in CD34+ HSPCs isolated from an asymptomatic patient with TBD with a pathogenic TERT p.P704S germ line mutation (MDA-3) transduced with lentiviral vectors carrying the wild-type or mutant U2AF1 allele after in vitro culture for 3 days (n = 13 674 cells). Each dot represents 1 cell. Different colors indicate cluster identity (left) and the U2AF1 mutational status (middle). Pathway enrichment analysis of genes significantly downregulated in U2AF1S34-transduced HSCs compared with those in U2AF1wild type-transduced HSCs (P ≤.01). Reactome gene sets are shown (right). Dotted lines indicate the annotated lineage clusters. (C) Pathway enrichment analysis of genes significantly downregulated in U2AF1S34-transduced CD34+ cells compared with those in U2AF1wild type -transduced CD34+ cells from another asymptomatic patient with TBD with short telomeres harboring the TERT p.R774X pathogenic mutation (MDA-19). Cells were transduced with lentiviral vectors carrying the mutant or wild-type U2AF1 allele, and after in vitro culture for 3 days, bulk RNA-seq analysis was performed (P adj ≤ .001; fold change <1). Hallmark gene sets are shown. (D) Pathway enrichment analysis from bulk RNA-seq showing the genes that underwent aberrant exon skipping (top) and intron retention (bottom) in U2AF1S34 HSPCs compared with U2AF1wild type HSPCs from panel C (P adj ≤ .05). Reactome gene sets are shown. cDCs, classic dendritic cells; DCs, dendritic cells; Ery, erythroid; GMP, granulocytic-monocytic progenitors; LMPP, lymphoid-myeloid primed progenitors; Mk, megakaryocytic; Mono, monocytic; NK, natural killer cells; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cells; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

To further establish a causal relationship between the U2AF1S34F mutation and the downregulation of IFN and TP53 signaling pathways, we expressed the U2AF1S34F or control U2AF1wild-type allele in CD34+ HSPCs from an asymptomatic patient with TBD harboring a pathogenic TERTP704S germ line mutation without any detectable CH (supplemental Figure 17E). Differential expression analysis showed that pathways associated with oxidative phosphorylation, IFN signaling, and TP53-mediated cell responses were significantly downregulated in U2AF1S34F and TERTP704S HSPCs (Figure 4B; supplemental Table 19) but were only mildly affected in age-matched healthy donor HSPCs overexpressing the U2AF1S34F mutation (supplemental Figure 17G). Similar results were observed by bulk RNA-seq when the U2AF1S34F mutation was transduced in HSPCs from another asymptomatic patient with TBD with short telomeres harboring the TERTR774X PGV (Figure 4C; supplemental Table 20). U2AF1S34F mutation induced aberrant exon skipping or intron retention (the types of splicing induced by U2AF1S34 mutations in MDS31) of genes involved in cell cycle, DNA repair, and TP53 regulation (Figure 4D; supplemental Tables 21 and 22). Together, these data suggest that U2AF1S34 mutations in HSPCs are compensatory SGR that overcome the deleterious effect of aberrant TP53 activation and IFN signaling induced by PGVs in telomere maintenance genes.

Discussion

The high prevalence of CH in TBDs, the limited number of recurrently mutated genes, and the biological and clinical patterns of CH trajectories are strong evidence of defective telomere maintenance as a driver of clonal selection. Clinically, CH in signature genes identified patients with TBD with progressive cytopenias, poor survival, and a higher risk of developing cancer.

Genome-wide association studies have investigated the inherited causes of CH, and variants in the TERT locus are among the top hits, suggesting a key role for telomere maintenance in CH development.34-36 Shorter telomeres, a natural consequence of aging, are also associated with CH.35,36 Thus, TBD can serve as a natural model to study the contribution of telomere maintenance and aging in CH development. We observed that impairment of specific telomere maintenance pathways, rather than abnormally short telomeres, was a key selective pressure for CH development. Although all patients in our cohort had a TL <10th percentile of age-matched controls, CH co-occurred with specific TBD PGVs. CH in PPM1D, also previously associated with shorter telomeres in healthy individuals,34,36 was mostly detected in patients in whom TERT and TERC germ line mutations impaired telomerase activity. The commonest age-related CH mutations (DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1, and JAK2), also associated with short telomeres in population studies,5,36,37 were rare in our cohort, even among older patients. In these cases, the associations of CH with shorter telomeres (though still within the normal range) may be related to other age-related mechanisms or the increased proliferative capacity of the mutant clone.

Different IBMFS appear to have a disease-specific CH profile that is related to the underlying pathophysiology (eg, EIF6 and TP53 somatic mutations in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, monosomy 7 in SAMD9/9L syndromes, and RUNX1 somatic mutations and Chr1q+ in Fanconi anemia).7,9-11,13,18,38,39 TBD disease-specific CH is also distinct from CH in immune-mediated aplastic anemia, in which recurrent somatic mutations in PIGA, the HLA locus, and BCOR/L1 are prevalent,40-42 and from standard MDS/AML, in which U2AF1 mutations are not frequent, even among splicing factor variants.43 Our data show that CH in TBD primarily involves pathways related to telomerase impairment and aberrant TP53 upregulation, demonstrating that these pathways are a major fitness constraint in telomere-dysfunctional HSCs, which are under selective pressure (Figure 5).

Distinct clonal profiles in TBDs as markers of progressive marrow failure and clonal evolution. PGVs in telomere maintenance genes cause TBDs with very short telomeres and aberrant TP53 and IFN signaling pathway activation in HSPCs, ultimately triggering HSPC senescence and apoptosis, which leads to HSC exhaustion and BMF. The clonal landscape of TBD, a marker of progressive BMF, highlights that telomerase impairment and aberrant TP53 and INF upregulation are key constraints of HSC fitness. Chr1q+ and U2AF1S34 and TP53 mutations are premalignant clonal events that increase the risk of developing hematologic malignancies mainly by suppressing TP53 pathway activation. U2AF1S34 (but not U2AF1Q157R mutations) and Chr1q+, initially compensatory and permissive of cell survival, were the main drivers of MDS/AML by ultimately allowing successive acquisition of preleukemic clonal events in other MDS-related genes. TP53 mutations were mostly associated with evolution to AML due to TP53 biallelic inactivation; these mutations are also associated with solid cancers. In contrast, PPM1D, POT1, and TERTp mutations are compensatory events that do not increase the risk of cancer development. Somatic POT1 and TERTp mutations likely overcome restricted HSC cell fitness caused by germ line TBD mutations by modulating telomerase activity and increasing cell proliferation. PPM1D mutations did not correlate with previous exposure to chemotherapies and may enhance HSCs’ competitive fitness and suppress the DNA damage response by TP53-negative regulation. The compensatory effects of these somatic mutations on hematopoiesis (eg, telomere lengthening or improved PB counts) may be limited by these mutations’ low clonal burden at the time of detection. INF, interferon; LoF, loss-of-function.

Distinct clonal profiles in TBDs as markers of progressive marrow failure and clonal evolution. PGVs in telomere maintenance genes cause TBDs with very short telomeres and aberrant TP53 and IFN signaling pathway activation in HSPCs, ultimately triggering HSPC senescence and apoptosis, which leads to HSC exhaustion and BMF. The clonal landscape of TBD, a marker of progressive BMF, highlights that telomerase impairment and aberrant TP53 and INF upregulation are key constraints of HSC fitness. Chr1q+ and U2AF1S34 and TP53 mutations are premalignant clonal events that increase the risk of developing hematologic malignancies mainly by suppressing TP53 pathway activation. U2AF1S34 (but not U2AF1Q157R mutations) and Chr1q+, initially compensatory and permissive of cell survival, were the main drivers of MDS/AML by ultimately allowing successive acquisition of preleukemic clonal events in other MDS-related genes. TP53 mutations were mostly associated with evolution to AML due to TP53 biallelic inactivation; these mutations are also associated with solid cancers. In contrast, PPM1D, POT1, and TERTp mutations are compensatory events that do not increase the risk of cancer development. Somatic POT1 and TERTp mutations likely overcome restricted HSC cell fitness caused by germ line TBD mutations by modulating telomerase activity and increasing cell proliferation. PPM1D mutations did not correlate with previous exposure to chemotherapies and may enhance HSCs’ competitive fitness and suppress the DNA damage response by TP53-negative regulation. The compensatory effects of these somatic mutations on hematopoiesis (eg, telomere lengthening or improved PB counts) may be limited by these mutations’ low clonal burden at the time of detection. INF, interferon; LoF, loss-of-function.

Although usually typical of cancers, in TBDs, CH in POT1, TERTp, and PPM1D correlated with aging and milder DC phenotypes but not with increased risk of cancer development. Consistent with previous reports,4,44 CH in these genes did not correlate with telomere elongation, blood count improvement, or phenotype reversion. As recently shown, TL measurement in specific blood cell types may be required to detect telomere elongation in mutated cells.45 Blood count recovery has also been associated with a striking POT1 clonal expansion in granulocytes of a patient with TINF2 PGV.45 Alternatively, CH may induce increased cellular proliferation, thereby reducing TL, or it could restore TL to levels required to stabilize disease in patients that would typically be more severe. Phenotypic reversion may also depend on the fitness advantage of compensatory CH; because it mainly occurred at a low VAF in our cohort, perhaps it was not sufficient to elongate telomeres or improve blood counts. Therefore, isogenic models and single-cell long-read DNA sequencing approaches may be required to further understand the impact of CH on TL.

In contrast, U2AF1S34 and TP53 mutations and Chr1q+ were mutually exclusive premalignant events that modulated TP53 signaling. Preferential selection of splicing factor mutations in TBDs, primarily U2AF1S34 but not U2AF1Q157R (perhaps due to distinct functions), has also been reported in small studies14,19 and observed in an independent cohort of 13 patients with TBD with malignancies, followed at MD Anderson Cancer Center (supplemental Table 23). Our functional studies demonstrated that U2AF1S34 mutations overcome restricted HSC fitness by downregulating the TP53 and IFN signaling pathways, which are intrinsically aberrantly activated in TBD HSPCs.32 Further studies using isogenic models are required to elucidate the specific targets involved in the downregulation of these pathways by U2AF1S34. Similar to Chr1q+, U2AF1S34 mutations ultimately drive MDS/AML development by enabling the acquisition of secondary clonal events, most commonly in RUNX1, ETV6, U2AF1Q157R, and other splicing factor genes. The latency of these mutations to MDS/AML development was variable (up to 16 and 13 years for Chr1q+ and U2AF1S34, respectively) and depended on the linear acquisition of second hits. Moreover, consistent with longitudinal studies,9,19,46,47 these mutations conferred a cellular proliferation advantage that led to clonal dominance; mutations were often stable over time, even when patients underwent androgen treatment (supplemental Figure 15).

TP53 mutations rarely co-occurred with CH in other genes and were associated with evolution to AML associated with chromosome 17p loss and TP53 biallelic inactivation. TP53 mutations in PB are also associated with solid cancers, which suggests that the TP53 pathway could be global route to cancer in multiple tissues. This observation, although occurring only in a few patients (n = 3 [of 7]), is supported by recent data showing that TP53 mutations were detected in 88% of solid tumors from patients with TBD.48

Although CH involving the TP53 pathway was associated with a higher incidence of MDS/AML (40%-50% at 5 years after the first visit), hematologic malignancies were not the main cause of death in patients with TBD. Most patients died from hematopoietic cell transplant–related complications, infections, and respiratory failure secondary to pulmonary fibrosis (supplemental Tables 23 and 24). However, we found no association between CH and pulmonary disease (supplemental Tables 6-8). Prospective studies are required to assess the clinical implications of CH detection, including the need for earlier therapeutic interventions.

In terms of diagnostics, this study found that TERTp mutations are specific markers of TBDs, a finding that could be particularly useful for patients with unknown germ line defects or variants of uncertain significance in telomere-related genes. To date, TERTp mutations have not been identified in patients with other IBMFS, immune aplastic anemia, inflammatory diseases, or healthy controls screened with a similar ECS panel.24,41,42,49,50

In conclusion, we demonstrated that CH involving deregulation of the TP53 pathway is a canonical route to malignancy in TBD, detected in 60% of patients who developed MDS/AML. Its detection, regardless of VAF, should prompt consideration of cancer development. In contrast, CH in other signature genes, otherwise typical of cancer, is not associated with malignancy in this TBD cohort. Our results suggest that the standard of care for symptomatic patients with TBD should include CH screening, to allow for clinical stratification of those at higher risk of cancer development and poorer OS. Further prospective data will be required to study the role of CH in formal cancer surveillance; however, based on our study, patients who develop mutations strongly associated with MDS/AML development, such as U2AF1S34, should be considered for increased BM examinations, and patients with TP53 mutations should prompt attention for the presence of solid malignancies. Key regulatory pathways that drive clonal transformation in telomere-dysfunctional HSCs may also be implicated in CH and MDS development in aging healthy individuals.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the study participants who made this work possible. The authors thank the DNA sequencing and Genomics Core Facility at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. The graphical abstract was made using Biorender.com.

This work was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (F.G.-R, E.M.G., R.S., B.A.P., X.M., D.H., N.S., L.A., S.K., I.D., D.J.Y., C.E.D., C.O.W., N.S.Y.), the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (M.R.N, L.J.M., N.G., B.P.A, S.A.S.), and by philanthropic contributions to the University of Texas MD Anderson MDS/AML Moon Shot. M.R.N. received funding from the Mildred-Scheel-Postdoctoral Fellowship Program by the German Cancer Aid. J.J.R.-S. is a recipient of the MD Anderson Odyssey Fellowship. This work was also supported in part by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP; grant numbers 13/08135-2 and 16/12799-1; R.T.C.) and used MD Anderson’s Advanced Cytometry and Sorting Facility, Advanced Technology Genomics Core Facility, all of which are supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center support grant (P30 CA16672).

Authorship

Contribution: F.G.-R., E.M.G., and S.C. designed the research; F.G.-R., E.M.G., N.T., N.S.Y., R.T.C., and S.C. guided the research; F.G.-R., N.T., D.H., F.S.D., N.S., B.A.S., T.-P.L., L.A., S.K., and W.Z. performed experiments; F.G.-R., E.M.G., L.F.B.C., M.R.N., L.J.M., D.V.C., B.A.P., I.D., D.J.Y., C.D.D., A.A., M.M.D.O., A.P.A., C.E.D., N.G., B.P.A., C.B., G.G.-M., M.O., E.O., E.P.P., S.A.S., N.S.Y., and R.T.C. provided patient-associated resources and/or patient samples for the studies; R.S., X.M., C.O.W., and P.V.B. performed the statistical analyses; S.P., J.L., and F.M. analyzed sequencing data; N.T. performed in vitro studies; F.G.-R. analyzed ECS and single-cell proteogenomic data; F.G.-R., E.M.G., N.T., J.J.R.-S., M.R.N., C.E.D., S.A.S., N.S.Y., G.G.-M., R.T.C., and S.C. made critical intellectual contributions throughout the project; and F.G.-R., E.M.G., N.S.Y., R.T.C., and S.C. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Simona Colla, Department of Leukemia, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, Texas 77030; email: scolla@mdanderson.org.

References

Author notes

F.G.-R., E.M.G., and N.T. equally contributed to this study.

Detailed genomic data are available in the supplemental Data. Raw clinical data cannot be publicly available due to data protection and National Institutes of Health institutional review board regulations. Data will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, with clearance by the ethics committee of involved institutions, Simona Colla (scolla@mdanderson.org).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![Clinical correlations with CH. (A) CH frequency (at minimum VAF of 0.5%) relative to age ranges in 207 patients with TBD (red curve) and 140 age-matched healthy donors (HDs; blue curve) screened using the same panel. CH frequency in TBDs at any age range was higher than that in HD (age 0-20 years, 22% vs 0 [P = .0359]; 21-40 years, 44% vs 4% [P = .0001]; 41-70 years, 55% vs 16% [P < .001]; >70 years, 75% vs 42% [P = .31]). (B) Kaplan-Meier curves of cumulative survival probabilities relative to the entire TBD cohort (n = 207; black curve) and disease inheritance (unknown inheritance mode [blue curve], AD-TINF2; [green curve], AD non-TINF2 [red curve], and recessive or X-linked recessive [AR/XLR; pink curve]). Survival probabilities were analyzed from patient’s date of birth. The log-rank test was used to determine statistical significance (P < .05). (C) Kaplan-Meier curves of cumulative survival probabilities based on CH types. Survival probabilities were calculated from the time of the first visit. Patients who underwent hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) were censored at the date of transplant. The log-rank test was used to determine statistical significance (P < .05). (D) Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression for OS. Variables selected by the stepwise model are shown on the right. (E) Cumulative incidence of MDS/AML in the entire cohort based on patient age (left) and the germ line mutated gene (right). Time to MDS/AML development was calculated from the time of the first visit. (F) Kaplan-Meier curves of cumulative incidence of MDS/AML in the entire cohort based on the CH types. Survival probabilities were calculated from the time of the first visit. Patients who underwent HCT were censored at the date of transplant. The log-rank test was used to determine statistical significance (P < .05). (G) Risk of MDS/AML development determined by multivariate stepwise Cox proportional hazards regression. Variables selected by the model are shown in the figure. (H) Association between CH and solid cancer development determined by multivariate logistic regression. ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; Hb, hemoglobin.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/144/23/10.1182_blood.2024025023/2/m_blood_bld-2024-025023-gr2.jpeg?Expires=1768126374&Signature=xAJ5wJ7WTnxkuDQM3WU5isYwl9NReC5-ihW22JgWF-ziuD2pi7aXn5qjpKS9oGq~vzSCPO70oy43yyq1GIc81Ry3gDzzcTuXzZdbIL71KPIHFdaIVG33BRuaLExVBhHm0lMO7DLUR7yp2XedrY9JPNeHWMy7XyE5JDWXwkS1kN1BjMSSaUFER4SoMU5MzmDYhrVuKVAy~z2~MJjY92i5KcVdH7ZjJlZnH7OeLTXIOi6ib6w9ZXFp5DzpYLzsa82NP4D4Hc-QUFRh-rp~peylx4xR9WML3b4n2dezK8cu~dvdwuS~jy2zbeA7bWSOEv6nyXCpJw~oCEInpcwEpgrQUg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Clonal hierarchies and dynamics. (A) Co-occurrence of CH associated with an increased risk of MDS/AML development. A Venn diagram shows the number of patients with Chr1q+, U2AF1S34, and TP53 mutations (left). Chr1q+ and U2AF1S34 or TP53 mutations were mutually exclusive in patients who developed malignancies (MDS, AML, or squamous cell carcinoma [SCC]). A patient with Coats plus syndrome had both TP53 and U2AF1S34 mutations without developing cancer (NIH-47). A graph shows the co-occurrence of Chr1q+ and U2AF1S34 with somatic mutations in other MDS-related genes (right). Chr1q+ and U2AF1S34 were always dominant clones, as a measure of VAF (right). Somatic mutations in other MDS-related genes, mainly in RUNX1, ETV6, and splicing factors, were likely subclonal. In contrast to U2AF1S34, all patients with Chr1q+ and CH in MDS-related genes developed MDS. TP53 mutations rarely co-occurred with somatic mutations in other MDS-related genes. (B) Clonal hierarchies defined by scDNA-seq analysis (left) and longitudinal analysis of mutant clones in granulocytes or total PB defined by bulk ECS (right) in 2 patients with multiple PPM1D or POT1 mutations (NIH-33 and BR-01). NIH-33 (MAA and liver disease at the age of 12) and BR-01 (MAA at age 18 years) had developed no malignancy at the last follow-up and are alive. ∗indicates PPM1D VAF in total PB from NIH-33; ∗∗indicates PPM1D VAF in PB mononuclear cells from NIH-33. An orange bar indicates the time NIH-33 was under low-dose danazol treatment. (C-D) Clonal hierarchies defined by scDNA-seq analysis (left) and longitudinal analysis of mutant clones in total PB defined by bulk ECS (right) in 3 patients with U2AF1S34 mutations (NIH-02, NIH-21, and NIH-39) (C) and in 1 patient with Chr1q+ and U2AF1Q157R mutation (NIH-11) (D). Blue and orange bars indicate the times when patients were under regular-dose or low-dose danazol treatment, respectively. NIH-21 (MAA and liver disease at the age 60 years) and NIH-39 (mild cytopenias at the age 26 years) had the U2AF1S34 mutation at VAF >20% in PB but no MDS/AML at the last follow-up. In contrast, NIH-02 (MAA and pulmonary fibrosis at the age of 39) developed MDS 2 years after the initial screening, and NIH-11 (MDS at the age 54 years), with a detectable Chr1q+ and U2AF1Q157R mutation at assessment, evolved to MDS with an excess of blasts (MDS-EB) and AML at 5.5 years of follow-up and died. Single-cell proteogenomic analysis evidenced that AML evolution coincided with the emergence of a KRAS mutation and monosomy 7 in CD34+ HSC clones harboring the Chr1q+ and U2AF1Q157R mutations (supplemental Figure 16). D, dominant clone; MAA, moderate aplastic anemia; S, subclonal clone; scDNA-seq, single-cell proteogenomic sequencing.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/144/23/10.1182_blood.2024025023/2/m_blood_bld-2024-025023-gr3.jpeg?Expires=1768126374&Signature=MJx1JGF1e1qglApJm3JcQicATND6fHUjDKBIppQ9oJwEl4CLExiRPvpcIjI4PP8eBQ28CND-R~-VNi4K5NK2Otv3MYN7CM3ZnYzKtNbvV46spqDZtQMo6YjzrC2mSoutXcSE0Gv5n~p8De9JVGadWLUvULnUMO3bnTXfP1vMCZahYdyzW-bvJDMQ9mhtahwp3D4mjUpGEsHZiVT3bI3ieRD5id0JyJwA1oTGgTtwSx7w1wUM05X7dQ4LxkAXbqRA-e6KjfjnozL5icLPKI-lo-r8cVy9fQVzeWiCxBb62F8JEnBiS82O0TUQzgx1XgYMRbij4i~U-tDaaVFdO2XZuw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal