Key Points

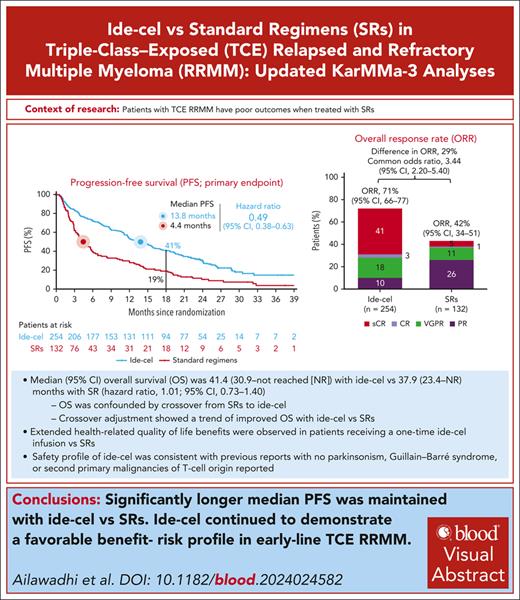

With longer follow-up, significantly longer median PFS was maintained with ide-cel vs SRs; safety remained consistent.

OS analysis was confounded by patient crossover from SRs to ide-cel; crossover adjustment showed a trend of improved OS with ide-cel vs SRs.

Visual Abstract

Outcomes are poor in triple-class–exposed (TCE) relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (R/RMM). In the phase 3 KarMMa-3 trial, patients with TCE R/RMM and 2 to 4 prior regimens were randomized 2:1 to idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel) or standard regimens (SRs). An interim analysis (IA) demonstrated significantly longer median progression-free survival (PFS; primary end point; 13.3 vs 4.4 months; P < .0001) and higher overall response rate (ORR) with ide-cel vs SRs. At final PFS analysis (median follow-up, 30.9 months), ide-cel further improved median PFS vs SRs (13.8 vs 4.4 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.38-0.63). PFS benefit with ide-cel vs SRs was observed regardless of number of prior lines of therapy, with greatest benefit after 2 prior lines (16.2 vs 4.8 months, respectively). ORR benefit was maintained with ide-cel vs SRs (71% vs 42%; complete response, 44% vs 5%). Patient-centric design allowed crossover from SRs (56%) to ide-cel upon progressive disease, confounding overall survival (OS) interpretation. At IA of OS, median was 41.4 (95% CI, 30.9 to not reached [NR]) vs 37.9 (95% CI, 23.4 to NR) months with ide-cel and SRs, respectively (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.73-1.40); median OS in both arms was longer than historical data (9-22 months). Two prespecified analyses adjusting for crossover showed OS favoring ide-cel. This trial highlighted the importance of individualized bridging therapy to ensure adequate disease control during ide-cel manufacturing. Ide-cel improved patient-reported outcomes vs SRs. No new safety signals were reported. These results demonstrate the continued favorable benefit-risk profile of ide-cel in early-line and TCE R/RMM. This trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT03651128.

Introduction

Despite therapeutic advances, patients with multiple myeloma (MM) invariably relapse, with a progressively worsening prognosis after each line of therapy.1-3 Management of relapsed MM remains challenging; patients are becoming triple-class exposed (TCE) earlier in their treatment course,4-8 with no standard of care for early TCE relapsed and refractory MM (R/RMM). Prognosis is poor with conventional therapies, with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of ∼3 to 5 months and a median overall survival (OS) of ∼9 to 22 months in this patient population.5-12

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has shown promising efficacy in patients with TCE R/RMM.13-21 In the phase 3 KarMMa-3 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03651128), idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel), a B-cell maturation antigen–directed CAR T-cell therapy was compared with standard regimens (SRs) in patients with TCE R/RMM who had received 2 to 4 prior lines of antimyeloma therapy and had disease refractory to the last regimen.13 In a prespecified KarMMa-3 interim analysis (IA) with 18.6 months median follow-up, a single ide-cel infusion demonstrated significantly longer median PFS vs SRs (13.3 vs 4.4 months), with a 51% lower risk of disease progression or death (hazard ratio [HR], 0.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.38-0.65; P < .0001).13 Ide-cel also demonstrated a significantly higher overall response rate (ORR) vs SRs (71% vs 42%; P < .0001), with deeper responses (complete response rate [CRR], 39% vs 5%, respectively).13 The safety profile of ide-cel was consistent with previous reports.13,18,19 The TCE KarMMa-3 study population included high proportions of patients with high-risk cytogenetics, Revised International Staging System for Multiple Myeloma (R-ISS) stage III disease, high tumor burden, extramedullary plasmacytoma, and triple-class–refractory (TCR) disease; ide-cel benefit was consistent across these subgroups.22 The median time from initial diagnosis to screening of ∼4 years and short median time to progression during the last previous antimyeloma therapy (∼7 months),13 which indicates the KarMMa-3 patient population had difficult-to-treat disease.

Here, we present results of the preplanned final PFS analysis of KarMMa-3 with extended follow-up (30.9 months) and the first full disclosure of interim OS. We also report PFS by number of prior lines of therapy (LoT).

Methods

Trial design and patients

The KarMMa-3 trial design has been reported previously.13 KarMMa-3 was an international, randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial that enrolled patients aged ≥18 years who had received 2 to 4 prior antimyeloma therapies including daratumumab, an immunomodulatory agent, and a proteasome inhibitor, and who had documented progressive disease (PD) ≤60 days since the last dose of prior therapy.

Randomization and treatment

Details on patient randomization, stratification factors, and treatment have been reported previously.13 Patients were randomized 2:1 to receive ide-cel (investigational arm) or 1 of 5 SRs, selected by investigators before randomization, based on most recent treatment regimen. After protocol amendment 2, a more patient-centric trial design allowed crossover so that patients randomized to SRs who had independent response committee (IRC)–confirmed PD could receive ide-cel as subsequent therapy per investigator’s discretion (supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website). During ide-cel manufacture, patients could receive ≤1 cycle of antimyeloma bridging therapy for disease control per investigator’s discretion. Bridging therapy comprised the same 5 regimens available to the SRs arm and was dependent on the most recent antimyeloma therapy. The protocol mandated a minimum 14-day washout period between bridging therapy and lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

Trial oversight

KarMMa-3 was designed by the sponsors 2seventy bio and Celgene (a Bristol Myers Squibb company), and academic investigators. The trial was conducted in accordance with the good clinical practice guidelines of the International Council for Harmonization.23 The protocol was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each participating center. All patients signed a written informed consent. The authors confirm the accurate and complete reporting of the data and assure adherence to the trial protocol. All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript and approved the final version.

End points and assessments

The primary end point was PFS, assessed by the blinded IRC per International Myeloma Working Group criteria in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population.24 Key secondary end points were ORR (partial response or better) per IRC, and OS. Additional secondary end points were CRR per IRC, minimal residual disease (MRD; assessed by next-generation sequencing at 10−5 sensitivity) status, PFS on next line of therapy (PFS2), health-related quality of life (HRQOL; supplemental Methods), and safety. PFS and OS analyses by number of prior LoT were conducted in the ITT population. Time-to-event end points were assessed from randomization to event.

Safety analyses, including CAR T-cell–related adverse events (AEs) cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and investigator-identified neurotoxicity (iiNT), were reported in the treated population (previously called the safety population13) of patients who received their randomly assigned study treatment. AEs and iiNT were graded per the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0325 or higher; CRS was graded according to the Lee criteria.26

Statistical analysis

The final PFS analysis was planned for the ITT population after 289 PFS events had occurred. An OS IA was planned at the final PFS analysis, and the final OS analysis planned after ∼222 deaths. The study has an overall power of ∼50% for the final OS analysis at a 1-sided significance level of 0.025. Because patients who crossed over from SRs to ide-cel upon PD might confound OS interpretation, 2 prespecified OS sensitivity analyses adjusting for crossover were planned and conducted: a 2-stage accelerated failure time (Weibull) model27 and a rank-preserving structural failure time model. Additionally, a post hoc inverse-probability-of-censoring weighting method was conducted (supplemental Appendix). Time-to-event analyses were performed using Kaplan-Meier (KM) methodology, and HRs were calculated from Cox proportional hazards models. Exploratory analyses included calculation of piecewise HR to understand potential nonconstant hazards and postprogression survival (time from confirmed PD to death due to any cause) in the SRs arm. Post hoc analyses of PFS and OS were conducted in the treated population and by number of prior LoT.

Results

Patients and treatment

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

In KarMMa-3, 386 patients were randomized (ide-cel, n = 254; SRs, n = 132). Baseline disease characteristics were generally balanced between treatment arms.13 Median time from initial diagnosis to screening was 4.1 (range, 0.2-21.8) years. In the ITT population, 168 (44%) patients had high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, 176 (46%) had 1q gain/amplification, 105 (27%) had high tumor burden, 93 (24%) had extramedullary plasmacytoma, and 45 (12%) had R-ISS stage III disease. Furthermore, 253 (66%) patients had TCR disease and 365 (95%) were daratumumab refractory.

Bridging therapy

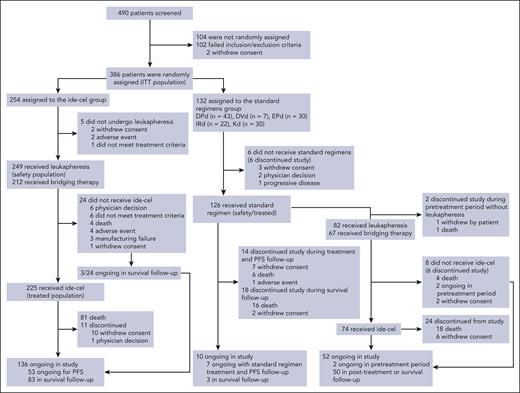

Of 254 patients randomly assigned to ide-cel, 212 (83%) received bridging therapy (Figure 1).

CONSORT diagram. In the SRs arm, 1 of 5 SRs was chosen before randomization for each patient by the investigator. The safety population included all the patients in the ITT (randomized) population who underwent leukapheresis or received bridging therapy, lymphodepleting chemotherapy, or ide-cel (ide-cel arm) or who received any dose of daratumumab, pomalidomide, lenalidomide, bortezomib, ixazomib, carfilzomib, elotuzumab, or dexamethasone (SRs arm). The treated population included all patients who received the treatment to which they were randomly assigned. Of 254 patients in the ide-cel arm in the ITT population, 249 underwent leukapheresis (safety population), 212 received bridging therapy, 227 received lymphocyte-depleting chemotherapy, and 225 received a single infusion of ide-cel. Five patients in the SRs arm had confirmed PD before treatment crossover to ide-cel was permitted after protocol amendment 2; instead, they received other subsequent antimyeloma therapies. DPd, daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone; DVd, daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; EPd, elotuzumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone; IRd, ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone; Kd, carfilzomib and dexamethasone.

CONSORT diagram. In the SRs arm, 1 of 5 SRs was chosen before randomization for each patient by the investigator. The safety population included all the patients in the ITT (randomized) population who underwent leukapheresis or received bridging therapy, lymphodepleting chemotherapy, or ide-cel (ide-cel arm) or who received any dose of daratumumab, pomalidomide, lenalidomide, bortezomib, ixazomib, carfilzomib, elotuzumab, or dexamethasone (SRs arm). The treated population included all patients who received the treatment to which they were randomly assigned. Of 254 patients in the ide-cel arm in the ITT population, 249 underwent leukapheresis (safety population), 212 received bridging therapy, 227 received lymphocyte-depleting chemotherapy, and 225 received a single infusion of ide-cel. Five patients in the SRs arm had confirmed PD before treatment crossover to ide-cel was permitted after protocol amendment 2; instead, they received other subsequent antimyeloma therapies. DPd, daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone; DVd, daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; EPd, elotuzumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone; IRd, ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone; Kd, carfilzomib and dexamethasone.

Because of protocol-constrained use of ≤1 cycle of bridging therapy, patients in the ide-cel arm who received bridging therapy received lower dose intensity treatment within 60 days of randomization than patients in the SRs arm (supplemental Table 1). The protocol requirement of a minimum 14-day washout period before lymphodepleting chemotherapy resulted in patients in the ide-cel arm having a median of 26 days without antimyeloma treatment during the first 60 days compared with 6 days in the SRs arm (supplemental Figure 1).

Treatment

Of 254 patients randomized to ide-cel, 225 received ide-cel infusion (treated population); 29 (11%) did not receive ide-cel and were enriched in high-risk disease characteristics at baseline (supplemental Table 2). Of these 29 patients, 5 did not proceed to leukapheresis (2 withdrew consent, 2 had AEs, and 1 did not meet treatment criteria) and 24 underwent leukapheresis but discontinued before ide-cel infusion (dropout; Figure 1). Dropout rates between leukapheresis and ide-cel infusion were higher in patients with greater numbers of prior LoT (4, 12.7%; 3, 10.5%; and 2, 5.3%). In the treated population, 192 (85%) patients received bridging therapy. At data cutoff (28 April 2023), 136 patients in the ide-cel arm were ongoing in the study.

Of 132 patients randomized to SRs, 126 received ≥1 dose of the assigned regimen (treated population); 6 (4.5%) did not receive study treatment (Figure 1). Of these 126 patients, 7 were ongoing on treatment with SRs and were in PFS follow-up, 3 were in survival follow-up; 32 patients discontinued from the study. Of patients randomized to SRs, 84 experienced IRC-confirmed PD and were eligible to crossover to ide-cel; of these, 2 patients discontinued during the pretreatment period and 82 (98%) underwent leukapheresis in preparation for ide-cel, with 8 not receiving ide-cel after leukapheresis (Figure 1). Therefore, of 132 patients randomized to SRs, 74 (56%) crossed over and received ide-cel; 52 were ongoing in the study, and 24 discontinued.

Efficacy

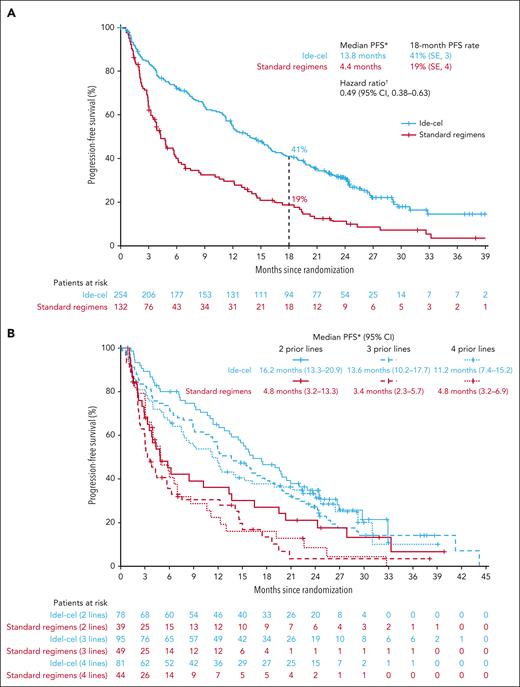

In this planned final PFS analysis, median follow-up was 30.9 months (range, 12.7-47.8). The median PFS benefit of ide-cel vs SRs was maintained from the IA (13.8 months [95% CI, 11.8-16.1] vs 4.4 months [95% CI, 3.4-5.8], respectively), representing a 51% reduction in risk of PD or death (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.38-0.63; Figure 2A). The PFS rate at 18 months was 41% (standard error, 3.2) with ide-cel and 19% (standard error, 3.8) with SR.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing progression-free survival in the intent-to-treat population and by number of prior lines of therapy. PFS overall (A; primary end point; ITT population) and by number of prior LoT (B; prespecified subgroup analysis, per protocol; ITT population). PFS was analyzed in the ITT population of all randomized patients in both arms and included early PFS events occurring between randomization and ide-cel infusion. PFS based on IMWG criteria per IRC. ∗Based on KM approach. †Stratified HR based on univariate Cox proportional hazard model. CI is 2-sided. IMWG, International Myeloma Working Group; SE, standard error.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing progression-free survival in the intent-to-treat population and by number of prior lines of therapy. PFS overall (A; primary end point; ITT population) and by number of prior LoT (B; prespecified subgroup analysis, per protocol; ITT population). PFS was analyzed in the ITT population of all randomized patients in both arms and included early PFS events occurring between randomization and ide-cel infusion. PFS based on IMWG criteria per IRC. ∗Based on KM approach. †Stratified HR based on univariate Cox proportional hazard model. CI is 2-sided. IMWG, International Myeloma Working Group; SE, standard error.

PFS benefit with ide-cel vs SRs was observed across numbers of prior LoT, with greater benefit observed in earlier lines. Median PFS was 11.2 months (95% CI, 7.4-15.2) with ide-cel vs 4.8 months (95% CI, 3.2-6.9) with SRs in patients with 4 prior LoT, 13.6 months (95% CI, 10.2-17.7) vs 3.4 months (95% CI, 2.3-5.7) in patients with 3 prior LoT, and 16.2 months (95% CI, 13.3-20.9) vs 4.8 months (95% CI, 3.2-13.3) in patients with 2 prior LoT (Figure 2B). In the treated population, median PFS was 15.7 months (95% CI, 12.5-18.9) in the ide-cel arm vs 4.4 (95% CI, 3.4-5.8) months in the SR arm (HR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.34-0.55; supplemental Figure 2).

With extended follow-up, ide-cel continued to demonstrate higher ORR vs SRs (71% vs 42%, respectively; common odds ratio, 3.44; 95% CI, 2.20-5.40; Table 1). In the ITT population, MRD-negative CRR was 22% (57/254) in the ide-cel arm vs 1% (1/132) in the SRs arm. In evaluable patients in the ITT population, MRD-negative CRR was 35% (57/163) vs 2% (1/54), respectively.

Treatment response assessed by IRC, in ITT population, and duration of response

| Time, n (%) . | Ide-cel (n = 254) . | SRs (n = 132) . |

|---|---|---|

| ORR∗ | ||

| Number of patients with response, n | 181 | 56 |

| Percentage of patients with response, % (95% CI)† | 71 (66-77) | 42 (34-51) |

| Common rate difference (95% CI)‡ | 29 (19-39) | |

| Common odds ratio‡ | 3.44 (2.20-5.40) | |

| CR rate§ | ||

| Number of patients with a CR, n | 111 | 7 |

| Percentage of patients with CR, % (95% CI)† | 44 (38-50) | 5 (2-9) |

| Common rate difference (95% CI)‡ | 38 (31-45) | |

| CR at 24 mo, n (%) | 50 (20) | 5 (4) |

| BOR, n (%) | ||

| sCR | 103 (41) | 6 (5) |

| CR | 8 (3) | 1 (1) |

| VGPR | 45 (18) | 15 (11) |

| PR | 25 (10) | 34 (26) |

| MR | 4 (2) | 8 (6) |

| SD | 31 (12) | 49 (37) |

| PD | 24 (9) | 10 (8) |

| Not evaluable/not done | 14 (6) | 9 (7) |

| Median time from randomization to response, mo (range)|| | 2.8 (1.1-13.0) | 2.1 (0.8-9.4) |

| Median DOR, mo (95% CI)¶,# | 16.6 (12.1-19.6) | 9.7 (5.5-16.1) |

| DOR rate at 18 mo, % (SE)∗∗ | 46 (3.8) | 28 (6.4) |

| MRD-negative CR rate, n/N (%)†† | 57/163 (35) | 1/54 (2) |

| 95% CI | 27.6-42.3 | 0.0-5.4 |

| Time, n (%) . | Ide-cel (n = 254) . | SRs (n = 132) . |

|---|---|---|

| ORR∗ | ||

| Number of patients with response, n | 181 | 56 |

| Percentage of patients with response, % (95% CI)† | 71 (66-77) | 42 (34-51) |

| Common rate difference (95% CI)‡ | 29 (19-39) | |

| Common odds ratio‡ | 3.44 (2.20-5.40) | |

| CR rate§ | ||

| Number of patients with a CR, n | 111 | 7 |

| Percentage of patients with CR, % (95% CI)† | 44 (38-50) | 5 (2-9) |

| Common rate difference (95% CI)‡ | 38 (31-45) | |

| CR at 24 mo, n (%) | 50 (20) | 5 (4) |

| BOR, n (%) | ||

| sCR | 103 (41) | 6 (5) |

| CR | 8 (3) | 1 (1) |

| VGPR | 45 (18) | 15 (11) |

| PR | 25 (10) | 34 (26) |

| MR | 4 (2) | 8 (6) |

| SD | 31 (12) | 49 (37) |

| PD | 24 (9) | 10 (8) |

| Not evaluable/not done | 14 (6) | 9 (7) |

| Median time from randomization to response, mo (range)|| | 2.8 (1.1-13.0) | 2.1 (0.8-9.4) |

| Median DOR, mo (95% CI)¶,# | 16.6 (12.1-19.6) | 9.7 (5.5-16.1) |

| DOR rate at 18 mo, % (SE)∗∗ | 46 (3.8) | 28 (6.4) |

| MRD-negative CR rate, n/N (%)†† | 57/163 (35) | 1/54 (2) |

| 95% CI | 27.6-42.3 | 0.0-5.4 |

Per IMWG uniform response criteria and as specified by the protocol. 95% CI was calculated using 2-sided Wald interval. Definitions of response and disease progression were modified from IMWG criteria.24 An overall response was defined as a PR or better. CR was defined as a complete response or a stringent complete response. An sCR was defined as a CR with a normal serum-free light-chain ratio and an absence of clonal plasma cells according to the IMWG response criteria.24 Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

BOR, best overall response; DOR, duration of response; IMWG, International Myeloma Working Group; MR, minimal response; PR, partial response; sCR, stringent CR; SD, stable disease; SE, standard error; VGPR, very good partial response.

Patients with PR or better.

CI is a 2-sided Wald CI.

Based on Mantel-Haenszel estimate.

Patients with CR or sCR.

In patients treated with ide-cel (n = 225), median time from ide-cel infusion to response was 1.0 months (range, 0.9-10.4).

Based on KM estimation per IRC based on IMWG criteria.

In patients with a response.

Based on the Greenwood formula.

Defined as ≥1 negative MRD value within 3 months before achieving ≥CR until PD or death. MRD was assessed by next-generation sequencing at a sensitivity of 10−5 per IMWG uniform response criteria and as specified by the protocol. 95% CI was calculated using 2-sided Wald interval. MRD-negative CR rate is shown in patients who had evaluable samples (163 in the ide-cel arm and 54 in the standard regimens arm).

After disease relapse on study treatment, 145 (57.1%) patients in the ide-cel arm and 105 (79.5%) in the SRs arm received subsequent antimyeloma therapy. Median PFS2 was 23.5 (95% CI, 18.4-27.9) vs 16.7 (95% CI, 12.2-20.3) months (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.60-1.04) in the ide-cel vs SRs arms, respectively (supplemental Figure 3).

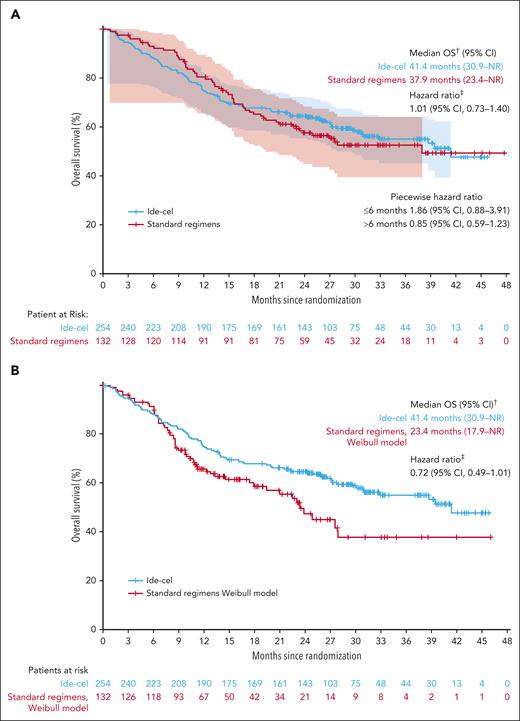

This prespecified IA of OS was conducted with 74% (164/222; ide-cel, n = 106; SRs, n = 58) of total planned OS events in the ITT population; most deaths were due to PD (ide-cel, n = 64/106 [60%]; SR, n = 37/58 [64%]); supplemental Table 3) and deaths due to AE were similar between the 2 arms (n = 17 [7%] vs n = 8 [6%], respectively). Of 17 deaths due to AEs in the ide-cel arm, 3 occurred on/after randomization but before ide-cel infusion, and 14 occurred on/after ide-cel infusion. Median OS was 41.4 (95% CI, 30.9 to not reached [NR]) months with ide-cel vs 37.9 (95% CI, 23.4 to NR) months with SRs (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.73-1.40; Figure 3A). Importantly, at data cutoff, 56% (74/132) of patients in the SRs arm had received ide-cel as subsequent therapy after IRC-confirmed PD as early as 2.9 months from randomization (median, 8.1 months [range, 2.9-36.7; interquartile range, 5.3-16.3]). Two prespecified sensitivity analyses adjusting for crossover showed a treatment benefit of ide-cel vs SRs using a 2-stage accelerated failure time (Weibull) model (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.49-1.01; Figure 3B) and a rank-preserving structural failure time model (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.58-1.88; supplemental Figure 4). A post hoc inverse-probability-of-censoring weighting model showed a trend in favor of ide-cel (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.51-1.22; supplemental Figure 5).

Kaplan-Meier curves showing overall survival in the intent-to-treat population and adjusting for crossover. OS (ITT population; A) and OS sensitivity analysis adjusted for crossover∗ (B). ∗Two-stage Weibull model without recensoring (prespecified analysis). †Based on KM approach. ‡Stratified HR is based on the univariate Cox proportional hazards model. CI is 2-sided and calculated by bootstrap method.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing overall survival in the intent-to-treat population and adjusting for crossover. OS (ITT population; A) and OS sensitivity analysis adjusted for crossover∗ (B). ∗Two-stage Weibull model without recensoring (prespecified analysis). †Based on KM approach. ‡Stratified HR is based on the univariate Cox proportional hazards model. CI is 2-sided and calculated by bootstrap method.

Because the OS KM curves crossed at 15 months, we analyzed deaths by time intervals (≤6 months, >6 to ≤12 months, or >12 months) from randomization and conducted a piecewise HR analysis of OS. Death rates by time intervals from randomization were numerically higher in the investigational arm vs SRs during the first 6 months (ide-cel, 12% [n = 30/254]; SRs, 7% [n = 9/132]; supplemental Table 4). The piecewise HR analysis of OS reflected this numeric difference in early deaths; HRs of ide-cel vs SRs were 1.86 (95% CI, 0.88-3.91) in the first 6 months and 0.85 (95% CI, 0.59-1.23) after 6 months from randomization (Figure 3A). To better understand why these patients died before they received ide-cel infusion, we assessed ide-cel manufacturing and median turn-around times and the causes of these early deaths. Median time from leukapheresis to CAR T-cell product release was similar in patients who died ≤6 months from randomization and the ITT population (35 days [range, 25-85] and 34 days [range, 24-102], respectively). In the ide-cel arm, the majority of early deaths (n = 17/30; 57%) occurred in patients who never received ide-cel treatment; of those 17 patients, 13 died because of PD (Table 2). In contrast, among patients who did receive assigned study treatment, early death rates were similar across arms (ide-cel, 5% [n = 13/254]; SRs, 7% [n = 9/132]). Most early deaths were due to PD or disease-associated complications (ide-cel, n = 18/30 [60%] vs SR, n = 6/9 [67%]; Table 2); deaths due to AEs were similar (ide-cel, 3% vs SRs, 2%; Table 2). In both treatment arms, patients who died ≤6 months from randomization were enriched for high-risk baseline disease characteristics associated with poor prognosis compared with the respective ITT populations (supplemental Table 5). Because most early deaths in the ide-cel arm occurred in patients who had not received ide-cel, we assessed OS in the treated population; median OS in the treated population was NR in both treatment arms, with a trend favoring ide-cel (analysis not adjusted for crossover; HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.58-1.18; supplemental Figure 6).

Summary of deaths in patients who died within 6 months of randomization, in the ITT population

| Parameter, n (%) . | Ide-cel (n = 254) . | SRs (n = 132) . |

|---|---|---|

| Patients who died within 6 mo of randomization | 30 (12) | 9 (7) |

| Primary cause of death | ||

| Death from AE (not otherwise specified) | 8 (3) | 3 (2) |

| Death from malignant disease or its complication | 18 (7) | 6 (5) |

| Death from other cause∗ | 4 (2) | 0 |

| Patients who did not receive study treatment and died | 17 (7) | 0 |

| Primary cause of death | ||

| Death from AE (not otherwise specified) | 3 (1) | 0 |

| Death from malignant disease or its complication | 13 (5) | 0 |

| Death from other cause | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Patients who received study treatment and died | 13 (5) | 9 (7) |

| Primary cause of death | ||

| Death from AE (not otherwise specified) | 5 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Death from malignant disease or its complication | 5 (2) | 6 (5) |

| Death from other cause | 3 (1) | 0 |

| Parameter, n (%) . | Ide-cel (n = 254) . | SRs (n = 132) . |

|---|---|---|

| Patients who died within 6 mo of randomization | 30 (12) | 9 (7) |

| Primary cause of death | ||

| Death from AE (not otherwise specified) | 8 (3) | 3 (2) |

| Death from malignant disease or its complication | 18 (7) | 6 (5) |

| Death from other cause∗ | 4 (2) | 0 |

| Patients who did not receive study treatment and died | 17 (7) | 0 |

| Primary cause of death | ||

| Death from AE (not otherwise specified) | 3 (1) | 0 |

| Death from malignant disease or its complication | 13 (5) | 0 |

| Death from other cause | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Patients who received study treatment and died | 13 (5) | 9 (7) |

| Primary cause of death | ||

| Death from AE (not otherwise specified) | 5 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Death from malignant disease or its complication | 5 (2) | 6 (5) |

| Death from other cause | 3 (1) | 0 |

All 4 cases of “death from other cause” in the ide-cel arm were reported verbatim as “unknown,” which was coded under the system organ class of “general disorder and administration site condition.”

OS benefit with ide-cel vs SRs was observed regardless of number of prior LoT, although greater benefit was observed in earlier lines. Median OS was NR months (95% CI, 32.8 to NR) with ide-cel vs NR months (95% CI, 37.9 to NR) with SR in patients with 2 prior LoT, 39.5 months (95% CI, 27.2 to NR) vs 27.6 months (95% CI, 17.9 to NR) in patients with 3 prior LoT, and 30.9 months (95% CI, 14.9 to NR) vs 23.4 months (95% CI, 15.6 to NR) in patients with 4 prior LoT, respectively (supplemental Table 6).

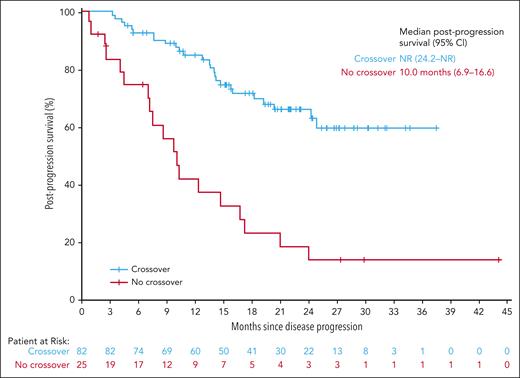

The impact of subsequent treatment with ide-cel was explored in the 82 patients in the SRs arm who crossed over to ide-cel after confirmed PD vs the 25 patients who did not; however, this was not protected by randomization and was subject to guarantee-time bias. Median postprogression survival in the SRs arm was NR (95% CI, 24.2 to NR) in patients who crossed over and 10.0 months (95% CI, 6.9-16.6) in patients who did not (Figure 4).

Kaplan-Meier curve showing postprogression survival in patients in the standard regimens arms who did or did not crossover to ide-cel. Postprogression survival in patients in the SRs arm who crossed over∗ vs did not crossover to ide-cel. ∗Based on KM methods. Patients who underwent leukapheresis with or without ide-cel infusion. Postprogression survival was defined as time from PD (IRC adjudicated) to death due to any cause.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing postprogression survival in patients in the standard regimens arms who did or did not crossover to ide-cel. Postprogression survival in patients in the SRs arm who crossed over∗ vs did not crossover to ide-cel. ∗Based on KM methods. Patients who underwent leukapheresis with or without ide-cel infusion. Postprogression survival was defined as time from PD (IRC adjudicated) to death due to any cause.

PROs

With longer follow-up since the IA,28 ide-cel demonstrated extended HRQOL benefits of a 1-time infusion with ide-cel compared with continuous treatment with SRs for the treatment of patients with TCE R/RMM. The minimally important difference for the mean change from baseline in global health status/QOL (+5), based on the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Core 30 Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ C30),29 was met for ide-cel but not for SR (supplemental Figure 7). Results were similar across patient-reported outcomes (PROs) primary domains of interest, using the EORTC QLQ-C30 (fatigue, physical functioning, pain, and cognitive functioning) and the EORTC QLQ MM Questionnaire (disease symptoms and side effects; supplemental Figure 7).

Safety

With extended follow-up, safety data remained consistent with earlier findings and no new safety signals were identified.13,18,19 In the ITT population, there was no difference in deaths due to AEs between the treatment arms (ide-cel, n = 106 [42%]; SR, n = 58 [44%]); most deaths in both arms were due to PD (64 [25%] and 37 [28%], respectively; supplemental Table 3). AEs occurred in 225 (100%) treated patients in the ide-cel arm and 124 (98%) in the SRs arm; grade 3/4 events occurred in 210 (93%) and 97 (77%), respectively (Table 3). Grade 3/4 hematologic AEs occurred in 198 (88%) patients in the ide-cel arm and 78 (62%) in the SRs arm (Table 3); most commonly neutropenia (79% vs 41%), anemia (45% vs 19%), and thrombocytopenia (42% vs 18%). Grade 3/4 infections and infestations occurred in 50 (22%) patients in the ide-cel arm and 25 (20%) in the SRs arm; most commonly pneumonia (6% vs 4%). Any-grade serious AEs occurred in 105 (47%) patients in the ide-cel arm and 52 (41%) patients in the SRs arm (Table 3).

Any-grade AEs occurring in 20% or more of patients and grade 3/4 AE occurring in 5% or more of patients, in the treated population

| Patients, n (%) . | Ide-cel (n = 225) . | SRs (n = 126) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade . | Grade 3/4 . | Any grade . | Grade 3/4 . | |

| Any AE | 225 (100) | 210 (93) | 124 (98) | 97 (77) |

| Hematologic | 204 (91) | 198 (88) | 92 (73) | 78 (62) |

| Neutropenia | 182 (81) | 177 (79) | 58 (46) | 52 (41) |

| Anemia | 131 (58) | 101 (45) | 47 (37) | 24 (19) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 121 (54) | 95 (42) | 37 (29) | 23 (18) |

| Leukopenia | 65 (29) | 64 (28) | 17 (13) | 13 (10) |

| Lymphopenia | 67 (30) | 65 (29) | 26 (21) | 24 (19) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 16 (7) | 16 (7) | 3 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Nonhematologic | ||||

| Infections and infestations | 125 (56) | 50 (22) | 72 (57) | 25 (20) |

| Pneumonia | 22 (10) | 14 (6) | 10 (8) | 5 (4) |

| Gastrointestinal | 143 (64) | 9 (4) | 66 (52) | 5 (4) |

| Nausea | 55 (24) | 2 (1) | 35 (28) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 68 (30) | 4 (2) | 31 (25) | 4 (3) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 131 (58) | 16 (7) | 81 (64) | 12 (10) |

| Fatigue | 49 (22) | 2 (1) | 44 (35) | 3 (2) |

| Pyrexia | 49 (22) | 2 (1) | 24 (19) | 1 (1) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 141 (63) | 80 (36) | 50 (40) | 16 (13) |

| Hypokalemia | 68 (30) | 12 (5) | 15 (12) | 1 (1) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 76 (34) | 49 (22) | 10 (8) | 3 (2) |

| Hypomagnesemia | 46 (20) | 2 (1) | 7 (6) | 1 (1) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 112 (50) | 14 (6) | 68 (54) | 11 (9) |

| Nervous system disorders | 104 (46) | 14 (6) | 60 (48) | 9 (7) |

| Headache | 41 (18) | 0 | 25 (20) | 1 (1) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 93 (41) | 13 (6) | 58 (46) | 7 (6) |

| Dyspnea | 27 (12) | 3 (1) | 28 (22) | 2 (2) |

| Vascular disorders | 72 (32) | 20 (9) | 30 (24) | 6 (5) |

| Hypertension | 33 (15) | 17 (8) | 15 (12) | 5 (4) |

| Immune system disorders | 202 (90) | 14 (6) | 3 (2) | 0 |

| CRS∗ | 197 (88) | 9 (4) | 0 | 0 |

| iiNT† | 34 (15) | 7 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Serious AEs | 105 (47) | 52 (41) | ||

| Patients, n (%) . | Ide-cel (n = 225) . | SRs (n = 126) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade . | Grade 3/4 . | Any grade . | Grade 3/4 . | |

| Any AE | 225 (100) | 210 (93) | 124 (98) | 97 (77) |

| Hematologic | 204 (91) | 198 (88) | 92 (73) | 78 (62) |

| Neutropenia | 182 (81) | 177 (79) | 58 (46) | 52 (41) |

| Anemia | 131 (58) | 101 (45) | 47 (37) | 24 (19) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 121 (54) | 95 (42) | 37 (29) | 23 (18) |

| Leukopenia | 65 (29) | 64 (28) | 17 (13) | 13 (10) |

| Lymphopenia | 67 (30) | 65 (29) | 26 (21) | 24 (19) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 16 (7) | 16 (7) | 3 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Nonhematologic | ||||

| Infections and infestations | 125 (56) | 50 (22) | 72 (57) | 25 (20) |

| Pneumonia | 22 (10) | 14 (6) | 10 (8) | 5 (4) |

| Gastrointestinal | 143 (64) | 9 (4) | 66 (52) | 5 (4) |

| Nausea | 55 (24) | 2 (1) | 35 (28) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 68 (30) | 4 (2) | 31 (25) | 4 (3) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 131 (58) | 16 (7) | 81 (64) | 12 (10) |

| Fatigue | 49 (22) | 2 (1) | 44 (35) | 3 (2) |

| Pyrexia | 49 (22) | 2 (1) | 24 (19) | 1 (1) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 141 (63) | 80 (36) | 50 (40) | 16 (13) |

| Hypokalemia | 68 (30) | 12 (5) | 15 (12) | 1 (1) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 76 (34) | 49 (22) | 10 (8) | 3 (2) |

| Hypomagnesemia | 46 (20) | 2 (1) | 7 (6) | 1 (1) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 112 (50) | 14 (6) | 68 (54) | 11 (9) |

| Nervous system disorders | 104 (46) | 14 (6) | 60 (48) | 9 (7) |

| Headache | 41 (18) | 0 | 25 (20) | 1 (1) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 93 (41) | 13 (6) | 58 (46) | 7 (6) |

| Dyspnea | 27 (12) | 3 (1) | 28 (22) | 2 (2) |

| Vascular disorders | 72 (32) | 20 (9) | 30 (24) | 6 (5) |

| Hypertension | 33 (15) | 17 (8) | 15 (12) | 5 (4) |

| Immune system disorders | 202 (90) | 14 (6) | 3 (2) | 0 |

| CRS∗ | 197 (88) | 9 (4) | 0 | 0 |

| iiNT† | 34 (15) | 7 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Serious AEs | 105 (47) | 52 (41) | ||

In the SRs arm, for the 69 patients who underwent leukapheresis in preparation for planned ide-cel treatment upon documented PD on standard regimen, only AEs before leukapheresis were included. All AEs were assessed from collection of informed consent for a minimum of 6 months after initiation of study treatment; grade ≥3 events continued to be recorded from month 7 until 28 days after PFS discontinuation visit, or 28 days after end-of-treatment visit for patients not continuing in PFS follow-up.

CRS was graded according to modified Lee criteria26; maximum-grade events are reported, patients could have >1 event.

Neurotoxicity includes immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome reported by investigator as a neurologic toxicity AE. No parkinsonism or Guillain-Barré syndrome were reported.

There were no additional CRS or iiNT events with ide-cel (supplemental Table 7).13 No parkinsonism or Guillain-Barré syndrome were reported and 2 (1%) patients had cranial nerve palsy not attributed to ide-cel by the investigator. Incidence per 100 patient-years of second primary malignancies (SPMs) was comparable between the ide-cel and SRs arms (3.6 [95% CI, 2.2-5.8] vs 4.1 [95% CI, 1.7-9.9], respectively). Hematologic SPMs occurred in 5 (2%) patients in the ide-cel arm (myelodysplastic syndromes, n = 4 [2%]; acute myeloid leukemia, n = 1 [<1%]); no hematologic SPMs occurred in the SRs arm or in patients in the SRs arm who received ide-cel after PD (supplemental Table 8). No SPMs of T-cell origin were reported in the ide-cel arm.

Discussion

In this final PFS analysis of KarMMa-3, ide-cel benefit was maintained,13 with substantially longer PFS and higher ORR vs SRs in patients with TCE R/RMM. Safety of ide-cel remained consistent with the IA, with no parkinsonism, Guillain-Barré syndrome, or SPMs of T-cell origin reported.13 Although there was no statistical difference in OS between ide-cel and SR treatment arms, interpretation of OS was confounded by crossover. Multiple analyses correcting for crossover consistently suggested a trend toward OS benefit with ide-cel vs SRs.

In this TCE population with poor outcomes with conventional therapies, the patient-centric KarMMa-3 study design permitted crossover from SRs to ide-cel upon confirmed PD. In total, 56% of patients randomized to SRs received ide-cel as subsequent therapy, with patients crossing over as early as 2.9 months with a median of 8.1 (interquartile range, 5.3-16.3) months from randomization to infusion, consistent with the short median PFS in the SRs arm (4.4 months). The median OS in the ide-cel (41.4 months) and SRs arms (37.9 months) were substantially longer than historical real-world data in TCE R/RMM (∼9-22 months),5-12 with longer than expected OS in the SRs arm, likely resulting from ide-cel treatment in patients who crossed over. A post hoc analysis of postprogression survival, albeit not protected by randomization and subject to guarantee-time bias,30 favored patients randomized to SRs who crossed over to ide-cel after PD vs those who did not (NR vs 10.0 months, respectively).

There was an imbalance between treatment arms in the proportion of early deaths occurring ≤6 months from randomization (ide-cel, 12%; SRs, 7%). During this period, the OS KM curves had wide and overlapping CIs (Figure 3A). The numerically higher proportion of early deaths in the investigational arm was driven largely by patients who did not receive ide-cel, and were mostly due to PD. Patients who died ≤6 months from randomization in both arms also had higher proportions of baseline disease characteristics associated with poor prognosis compared with the ITT population. In some of these patients, protocol-restricted bridging therapy insufficiently controlled the disease prior to ide-cel infusion. Patients in the ide-cel arm received lower dose intensity of bridging therapy than in the SRs arm during the first 60 days from randomization and had more days without antimyeloma therapy resulting from the protocol-required washout period between bridging therapy and ide-cel infusion. These results highlight the importance of effective bridging therapy during ide-cel manufacturing, minimizing the treatment gap prior to ide-cel infusion, and the need for appropriate tailoring of bridging therapy that reflects patient disease characteristics and prior treatment history.

Subgroup analyses by number of prior LoT showed greater ide-cel benefit in earlier lines, whereas PFS with SRs remained poor across all prior LoT investigated. Additionally, there was a trend toward greater OS benefit with ide-cel vs SRs in earlier lines. Dropout rates between leukapheresis and ide-cel infusion were lower in earlier vs later lines (5.3% vs 12.7%, respectively). Effective bridging therapy would be easier to achieve if patients were treated with ide-cel in earlier LoT given the increasing disease refractoriness at later lines. These data support the value of ide-cel, especially in earlier LoT, as an effective treatment option with a manageable safety profile in TCE R/RMM, a population with suboptimal outcomes with existing SRs, and substantial unmet clinical need.

With additional follow-up since an analysis of PROs in the IA,28 patients who received ide-cel continued to show sustained and clinically meaningful improvements in PROs, including pain, physical functioning, and fatigue, vs SRs. These outcomes were not confounded by crossover because per protocol, HRQOL data from SRs were collected only until PD and not after crossover. Therefore, the improvements in PRO data with ide-cel further substantiate the sustained benefit of 1-time ide-cel infusion in TCE R/RMM.

In this extended follow-up, the ide-cel safety profile was consistent with prior reports.13,18,19 No new safety signals were observed and no additional CRS or iiNT events were identified. The majority of deaths that occurred since the IA were due to PD (ide-cel, n = 20/31 [65%]; SRs, n = 14/24 [58%]).13 There were no differences between arms in the proportion of deaths due to AEs. Assessment of SPMs remains an important consideration in the treatment paradigm of heavily pretreated R/RMM.31 SPM incidence per 100 person-years in KarMMa-3 was comparable between the treatment arms (ide-cel, 3.6; SRs, 4.1).

The B-cell maturation antigen–directed CAR T-cell therapy ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel) has also been studied in earlier lines of R/RMM therapy; the randomized phase 3 CARTITUDE-4 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04181827) included patients with lenalidomide-refractory R/RMM who received 1 to 3 prior therapies.14 However, CARTITUDE-4 is not directly comparable with KarMMa-3 because of several differences in study design and patient populations, as evidenced by differences in median PFS observed in the control arms (KarMMa-3, 4.4 months; CARTITUDE-4, 11.8 months). Most notably, patients in KarMMa-3 were more heavily pretreated than those in CARTITUDE-4; 100% of patients in KarMMa-3 vs 26% in CARTITUDE-4 had TCE R/RMM, 66% vs 15% had TCR disease, and 95% vs 22% were daratumumab refractory (100% vs 25% were daratumumab exposed). Median number of prior regimens was 3 (range, 2-4) vs 2 (range, 1-3), respectively.13,14 Furthermore, more patients in KarMMa-3 had stage III disease at baseline (KarMMa-3, R-ISS, 12%; CARTITUDE-4, ISS, 6%). Patients randomized to cilta-cel in CARTITUDE-4 were also required to receive ≥1 cycle of bridging therapy,14 whereas in KarMMa-3, bridging therapy was restricted to ≤1 cycle and the required washout period was longer. The patient population in KarMMa-3 also had more refractory disease, making it more challenging for bridging therapy to be successful. Notably, CARTITUDE-4 did not allow crossover from standard therapies to cilta-cel upon confirmed PD. Patients in the cilta-cel arm of CARTITUDE-4 who had increased tumor burden after bridging therapy or lymphodepletion were assessed as having PD and could receive cilta-cel as subsequent therapy at the investigator’s discretion14; in KarMMa-3, these patients were permitted to remain on study. Notably in KarMMa-3, 54% (207/386) of patients were enrolled in the United States compared with 15% (64/419) in CARTITUDE-4.14 Furthermore, the proportion of Black patients enrolled in KarMMa-3 from the United States (17% [35/207]), was representative of the epidemiology of the disease in the United States, where ∼21% of patients with myeloma are Black.32 Despite the differences between trial designs and patient populations, data from KarMMa-3 and CARTITUDE-4 support the use of CAR T-cell therapies in earlier lines in patients with R/RMM.

Potential limitations of the KarMMa-3 trial have been previously reported.13 Additionally, the crossover design confounded the interpretation of OS.

With extended follow-up, PFS and ORR benefit were maintained with ide-cel and responses to ide-cel were deeper and more durable vs SRs in KarMMa-3. The short PFS in the SRs arm resulted in a substantial proportion of patient crossover from SRs, and treatment with ide-cel resulted in improved OS in both arms. Sensitivity analyses adjusting for crossover indicated a trend for improved OS with ide-cel vs SRs. The numeric difference between arms in early death events was driven mostly by patients who never received ide-cel. These data highlight the importance of appropriate bridging therapy and support its use as standard in patients awaiting infusion, with the aim of controlling or reducing disease burden during manufacture so patients have the greatest possible chance of receiving and benefiting from CAR T-cell therapy. Individualized bridging therapy including multiple cycles, followed by shorter washout periods than were mandated by the KarMMa-3 protocol, should be considered based on specific patient need. The numerically greater PFS and OS benefit with ide-cel in earlier LoT in conjunction with lower dropout rate between leukapheresis and infusion suggests that ide-cel use in earlier LoT may allow more patients to benefit from ide-cel. PROs continued to improve with ide-cel vs SRs, emphasizing the benefit of the 1-time infusion of ide-cel and subsequent long treatment-free interval compared with continuous treatment with SRs. The ide-cel safety profile remained consistent with previous reports,13,18,19 with no parkinsonism, Guillain-Barré syndrome, or SPMs of T-cell origin reported. These results confirm the benefit of a 1-time infusion of ide-cel in patients with TCE R/RMM, a population with poor outcomes with existing SRs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and families who are making the study possible and the clinical study teams who participated.

Writing and editorial assistance were provided by Nick Patterson and Simon Wigfield of Caudex, a division of Interpublic Group (IPG) Health Medical Communications, funded by Bristol Myers Squibb. This study was supported by 2seventy bio and Celgene, a Bristol Myers Squibb company.

Authorship

Contribution: S.A., B.A., A.K.N., S.M., N.C., L.J.C., I.W.A., R. Benjamin, Y.C., X.Z., M. Cook, and P.R.-O. performed research, collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; K.P., M. Cavo, R.V., R. Baz, C.C., N.R., A.B., T.P., J.F., and A.C. collected data; N.J.B., C.S., and J.P. performed research, collected data, and analyzed and interpreted data; S.S. performed research, collected data, and wrote the manuscript; P.M., S.J., F.W., L.E., and M.P.M. analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript; S.I. and M.D. collected data and analyzed and interpreted data; J.B. and D.D. performed research and analyzed and interpreted data; S.G. and A.T.-H. designed research, performed research, collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors contributed to, and approved the, presentation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.A. received research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Ascentage, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cellectar, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pharmacyclics, and Sanofi; and received consulting fees from BeiGene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cellectar, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Takeda. B.A. received consulting fees from Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Janssen; received honoraria from, and participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board with, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Sanofi; and received travel support from Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Sanofi, and Takeda. K.P. received consulting fees from AbbVie, Arcellx, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Caribou, Cellectis, Genentech, Janssen, Karyopharm, Legend, Merck, Oncopeptides, Pfizer, Precision, and Takeda. M. Cavo received honoraria and consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Karyopharm, Menarini, Sanofi, and Stemline. A.K.N. received research funding from Aduro, Amgen, Arch, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cellectis, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Karyopharm, Kite, Merck, Pfizer, and Takeda; and reports honoraria and participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board with Adaptive, Amgen, BeyondSpring, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cellectar, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Karyopharm, Oncopeptides, Optimized Natural Killer (ONK) Therapeutics, Pfizer, Sanofi, Secura, and Takeda. S.M. received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb; and reports participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board with AbbVie, Adaptive, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Oncopeptides, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, and Takeda. L.J.C. received research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech, and Janssen; received consulting fees from Adaptive, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Pfizer; and received honoraria from AbbVie, Adaptive, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Pfizer. R.V. received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Sanofi, and Takeda; and received honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Karyopharm, Legend, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda. N.J.B. received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb; received honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Forus, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Karyopharm, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda; and received payment for expert testimony from Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Karyopharm, and Pfizer. P.M. received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Sanofi, and Takeda. I.W.A. received consulting fees from Janssen; received honoraria from Takeda; and served in a leadership role with Novartis. R. Baz received research funding from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Karyopharm; received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda; and had participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board with GlaxoSmithKline. A.B. received honoraria from Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Sanofi. C.C. received research funding from Gilead and Janssen; and received honoraria from AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, and Novartis. S.J. received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Karyopharm, Legend, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Takeda; travel support from American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), American Society of Hematology (ASH), and International Myeloma Society (IMS); participated on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board with Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Sanofi; and served in a leadership role with ASH, IMS, and Society of Hematologic Oncology N.R. received research funding and consulting fees from, and served in a leadership role with, AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Caribou, GlaxoSmithKline, Immuneel, Janssen, K36 Therapeutics, Pfizer, and Sanofi. C.S. received research funding from Janssen, Novartis, and Takeda; received consulting fees from Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen. and Roche; received honoraria from Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi, and Takeda; received travel support from Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi, and Takeda; reports participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board with Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Miltenyi, Novartis, Sanofi, and Takeda; and reports receipt of equipment, materials, drugs, medical writing, gifts, or other services from Miltenyi. M.D. received research funding from Janssen; and received consulting fees and honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Sanofi, and Stemline. S.I. received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Chugai, Janssen, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda; received honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, ONO, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda; and participated on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board with Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda. J.B. received research funding from 2seventy Bio, AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, C4, Caribou, CARsgen, Cartesian, Celularity, Crispr, Fate, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Ichnos, Incyte, Janssen, Juno, K36. Karyopharm, Lilly, Novartis, Poseida, Roche, Sanofi, and Takeda; and received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Caribou, Galapagos, Janssen, K36, Kite, Legend, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Sebia, and Takeda. S.G. received research funding from Miltenyi, Omeros, and Takeda; and participated on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board with Actinuum, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Jazz, Johnson & Johnson, Kite, Novartis, Spectrum, and Takeda. A.T-H. is employed by, and holds equity in, 2seventy bio. Y.C., J.F., A.C., and M.P.M. are employed by Bristol Myers Squibb. X.Z., F.W., J.P., and D.D. are employed by, and hold equity in, Bristol Myers Squibb. L.E. is employed by, and holds equity in, Bristol Myers Squibb; and has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline. M. Cook is employed by, and holds equity in, Bristol Myers Squibb; has received honoraria from Amgen; participated on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board with Bristol Myers Squibb and GlaxoSmithKline; and reports a leadership role in UK National Cancer Research Institute Myeloma Subgroup 2020 and the Institute of Cancer and Genomic Science, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom. P.R.-O. received consulting fees from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, and Roche; received honoraria from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, and Sanofi; received travel support from Pfizer; and participated on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board with AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Oncopeptides, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sikander Ailawadhi, Mayo Clinic, 4500 San Pablo Rd S, Jacksonville, FL 32224; email: ailawadhi.sikander@mayo.edu.

References

Author notes

Presented orally (progression-free survival [PFS], response rates, overall survival, duration of response, minimal residual disease negativity, PFS2, time to next antimyeloma therapy, and safety summary data) at the 66th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, 11 December 2023 (abstract number 1028). At the request of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), efficacy and safety data were discussed at a meeting of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee, 15 March 2024; this was streamed live and posted on YouTube by the FDA.

Bristol Myers Squibb company policy on data sharing may be found at https://www.bms.com/researchers-and-partners/independent-research/data-sharing-request-process.html.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal