Key Points

Teclistamab provides clinically meaningful responses in patients with R/RMM with prior anti-BCMA treatment.

The two treatment-emergent grade ≥3 toxicities most frequently reported in patients with prior exposure to anti-BCMA therapy were cytopenias and infections

Visual Abstract

Teclistamab is a B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–directed bispecific antibody approved for the treatment of patients with triple-class exposed relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (R/RMM). In the phase 1/2 MajesTEC-1 study, a cohort of patients who had prior BCMA-targeted therapy (antibody-drug conjugate [ADC] or chimeric antigen receptor T-cell [CAR-T] therapy) was enrolled to explore teclistamab in patients previously exposed to anti-BCMA treatment. At a median follow-up of 28.0 months (range, 0.7-31.1), 40 patients with prior BCMA-targeted therapy had received subcutaneous 1.5 mg/kg weekly teclistamab. The median prior lines of treatment was 6 (range, 3-14). Prior anti-BCMA therapy included ADC (n = 29), CAR-T (n = 15), or both (n = 4). The overall response rate was 52.5%; 47.5% of patients achieved very good partial response or better, and 30.0% achieved complete response or better. The median duration of response was 14.8 months, the median progression-free survival was 4.5 months, and the median overall survival was 15.5 months. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were neutropenia, infections, cytokine release syndrome, and anemia; cytopenias and infections were the most common grade ≥3 TEAEs. Infections occurred in 28 patients (70.0%; maximum grade 3/4, n = 13 [32.5%]; grade 5, n = 4 [10%]). Before starting teclistamab, baseline BCMA expression and immune characteristics were unaffected by prior anti-BCMA treatment. The MajesTEC-1 trial cohort C results demonstrate favorable efficacy and safety of teclistamab in patients with heavily pretreated R/RMM and prior anti-BCMA treatment. This trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT03145181 and #NCT04557098.

Introduction

Advances in the treatment of patients with multiple myeloma (MM) have markedly improved overall patient survival.1 Current standard of care options include immunomodulatory drugs, proteasome inhibitors, and anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies2-4; however, many patients become refractory to these initial therapies and relapse.5,6 Thus, additional effective and well-tolerated treatments are needed for patients who develop relapsed/refractory MM (R/RMM).

B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) is an established treatment target for MM. In recent years, several BCMA-targeting agents, including chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), and bispecific antibodies, have been approved for use in patients with R/RMM who are triple-class exposed.7-10 Among apheresed patients with heavily pretreated R/RMM, overall response rates (ORRs) of 83% and 67% have been seen with ciltacabtagene autoleucel9 and idecabtagene vicleucel,11 respectively; however, CAR-T therapy has limitations regarding patient eligibility, safety, and access to treatment.12 The anti–BCMA-ADC belantamab mafodotin also demonstrated efficacy in triple-class exposed R/RMM but has since been withdrawn from the United States,13 and the European Commission recommended against renewing its marketing authorization.14

BCMA-targeting bispecific antibodies (teclistamab and elranatamab) are among the most-recently approved therapies for heavily pretreated patients with MM.15-17 Teclistamab is the first approved BCMA × CD3 bispecific antibody for the treatment of patients with triple-class exposed R/RMM,15,16 with weight-based dosing and, to our knowledge, the longest study follow-up of any bispecific antibody in MM. In the phase 1/2 MajesTEC-1 study, patients with R/RMM who were naive to BCMA-targeting therapies achieved deep and durable responses regardless of refractory status, with an ORR of 63.0% (45.5% achieving complete response [CR] or better) at a median follow-up of 22.8 months.18 The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 11.3 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 8.8-16.4), and the median duration of response (DOR) was 21.6 months (95% CI, 16.2 to not estimable [NE]).18

Emerging evidence suggests that patients who have been exposed to anti-BCMA therapy can still respond to subsequent therapy with a different BCMA-targeted treatment.19,20 Here, we present efficacy and safety data from cohort C in MajesTEC-1, which enrolled patients who had previously received noncellular and cellular BCMA-targeted therapies.

Methods

Study design and treatment

MajesTEC-1 is an ongoing, first-in-human, phase 1/2, open-label, multicohort, multicenter study of teclistamab in patients with R/RMM who were triple-class exposed (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT03145181 and NCT04557098). Details of study design, end point assessments, and analysis methods for MajesTEC-1 have been described previously.10 Eligible patients in the cohort reported here had a documented diagnosis of R/RMM per International Myeloma Working Group criteria; were triple-class exposed, including an immunomodulatory drug, a proteasome inhibitor, and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, and must have also been previously exposed to an anti-BCMA treatment, either CAR-T therapy or an ADC; had progressive, measurable disease at screening; and had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of 0 or 1.

Patients received subcutaneous teclistamab according to protocol (step-up dose 1, 0.06 mg/kg; step-up dose 2, 0.3 mg/kg; first treatment dose, 1.5 mg/kg weekly, with the option to switch to every 2 weeks dosing if patients achieved a CR or better for ≥6 months).15,16 To reduce the risk of cytokine release syndrome (CRS), patients received premedication with dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, and acetaminophen and were hospitalized for observation during both step-up doses and first full dose of teclistamab. For patients with fever (≥38°C) not attributed to any other cause, tocilizumab was considered for patients with grade 1 CRS and recommended for grade ≥2.

All patients provided informed written consent, and the MajesTEC-1 study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Council for Harmonisation. The study protocol, amendments, and relevant documents were reviewed and approved by an independent ethics committee or institutional review board at each study center.

End points and assessments

The primary end point of the phase 2 part of MajesTEC-1 was ORR,10 defined as the proportion of patients achieving partial response or better by International Myeloma Working Group criteria, based on independent review committee assessment.

Key secondary end points were very good partial response (VGPR) or better; CR or better; DOR; time to response; PFS; overall survival (OS); minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity status (10–5; as assessed in DNA samples from bone marrow aspirates, by next-generation sequencing [clonoSEQ assay, v2.0, Adaptive Biotechnologies]); and teclistamab pharmacokinetics (PK), immunogenicity, and safety.

All adverse events (AEs) were graded per the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (v4.03), excluding CRS and immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), which were both graded in accordance with American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy criteria.

Blood samples were collected for the measurement of serum teclistamab concentrations at step-up dose 1, on days 1 and 8 of cycle 1; on day 1 of cycles 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 10, and 13; and then every 6 months until end of treatment. Serum samples were analyzed for teclistamab concentrations using a validated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay format on the Meso Scale Discovery platform.

Exploratory end points included assessment of soluble BCMA (sBCMA), membrane BCMA, and the characterization of T-cell subsets and activation and exhaustion markers in peripheral blood and tumor. Additional methods are presented in the supplemental Appendix, available on the Blood website.

Statistical analysis

The sample size of cohort C was selected to collect data on efficacy and safety. Simon's 2-stage design was used to test the null hypothesis that the ORR was at most 15%, against the alternative that the ORR was at least 35% at a 1-sided significance level of .025 with 80% power. The primary analysis set includes all patients who received at least 1 dose of teclistamab in phase 2 and is used in safety and efficacy summaries. ORR and associated 2-sided 95% CIs were calculated. Kaplan-Meier methods were used to describe time-to-event end points (DOR, time to response, PFS, and OS). Safety, PK, pharmacodynamics, and immunogenicity results for patients enrolled in cohort C were compared descriptively with those of the 165 patients enrolled in the pivotal recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D) cohort. Statistical analyses were performed by the study sponsor.

Results

Patient population

As of 22 August 2023, forty patients in cohort C had received teclistamab. The median age was 64 years (range, 32-82), and 62.5% of patients were male (Table 1). Twelve of 40 patients (30.0%) had ≥1 extramedullary plasmacytomas (ie, soft tissue plasmacytomas that were not associated with bone), and 12 of 36 patients (33.3%) had high-risk cytogenetics at screening. All patients were previously exposed to ≥1 anti-BCMA treatment: 29 patients were exposed to ADC treatment, 15 to CAR-T, and 4 to both ADC and CAR-T. The median number of prior lines of therapy was 6 (range, 3-14). Overall, 34 of 40 patients (85.0%) were triple-class refractory, and 27 of 40 (67.5%) were refractory to prior BCMA-directed therapy. Teclistamab was received as the next line of therapy after ADC treatment in 10 patients (median interval of 1.4 months [range, 0.7-4.8] between BCMA-targeted ADC and teclistamab) and after CAR-T in 8 patients (median interval of 4.6 months [range, 3.0-10.6] between CAR-T and teclistamab). The other 22 patients in cohort C did not have BCMA-directed therapy as the last line of therapy before teclistamab treatment (median interval of 1.1 months [range, 0.2-2.9] between treatments).

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic . | Cohort C (N = 40) . |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 63.5 (32-82) |

| Age ≥75 y, n (%) | 3 (7.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 25 (62.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 35 (87.5) |

| African American/Black | 3 (7.5) |

| Asian | 1 (2.5) |

| Not reported | 1 (2.5) |

| Bone marrow plasma cells ≥60%∗, n (%) | 4 (10.0) |

| Extramedullary plasmacytomas ≥1†, n (%) | 12 (30.0) |

| High-risk cytogenetics,‡ n (%) | 12 (33.3) |

| ISS stage, n (%) | |

| I | 21 (52.5) |

| II | 9 (22.5) |

| III | 10 (25.0) |

| Time since diagnosis, median (range), y | 6.5 (1.1-24.1) |

| Prior lines of therapy, median (range) | 6 (3-14) |

| Prior stem cell transplantation, n (%) | 36 (90.0) |

| Exposure status, n (%) | |

| Triple-class§ | 40 (100) |

| Penta-drug|| | 32 (80.0) |

| BCMA-targeted treatment | 40 (100)¶ |

| ADC | 29 (72.5) |

| CAR-T | 15 (37.5) |

| Refractory status, n (%) | |

| Triple-class§ | 34 (85.0) |

| Penta-drug|| | 14 (35.0) |

| To last line of therapy | 34 (85.0) |

| Characteristic . | Cohort C (N = 40) . |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 63.5 (32-82) |

| Age ≥75 y, n (%) | 3 (7.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 25 (62.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 35 (87.5) |

| African American/Black | 3 (7.5) |

| Asian | 1 (2.5) |

| Not reported | 1 (2.5) |

| Bone marrow plasma cells ≥60%∗, n (%) | 4 (10.0) |

| Extramedullary plasmacytomas ≥1†, n (%) | 12 (30.0) |

| High-risk cytogenetics,‡ n (%) | 12 (33.3) |

| ISS stage, n (%) | |

| I | 21 (52.5) |

| II | 9 (22.5) |

| III | 10 (25.0) |

| Time since diagnosis, median (range), y | 6.5 (1.1-24.1) |

| Prior lines of therapy, median (range) | 6 (3-14) |

| Prior stem cell transplantation, n (%) | 36 (90.0) |

| Exposure status, n (%) | |

| Triple-class§ | 40 (100) |

| Penta-drug|| | 32 (80.0) |

| BCMA-targeted treatment | 40 (100)¶ |

| ADC | 29 (72.5) |

| CAR-T | 15 (37.5) |

| Refractory status, n (%) | |

| Triple-class§ | 34 (85.0) |

| Penta-drug|| | 14 (35.0) |

| To last line of therapy | 34 (85.0) |

IMiD, immunomodulatory drug; ISS, International Staging System; PI, proteasome inhibitor.

Includes bone marrow biopsy and aspirate.

Soft tissue plasmacytomas not associated with bone were included.

Del(17p), t(4:14), and/or t(14;16) (n = 36).

Greater than or equal to 1 PI, ≥1 IMiD, and ≥1 anti-CD38 antibody.

Greater than or equal to 2 PIs, ≥2 IMiDs, and ≥1 anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody.

Four patients had received both ADC and CAR-T.

The median follow-up was 28.0 months (range, 0.7-31.1), and the median duration of teclistamab treatment was 6.0 months (0.2-29.8). Patients discontinued treatment due to disease progression (n = 21), death (n = 9), AEs (n = 3), physician decision (n = 2), or patient refusal of further treatment (n = 1).

Ten patients switched from weekly to every 2 weeks, including 6 patients who met the prespecified (ie, response-related) criteria to switch to less frequent dosing (a response of CR or better for a minimum of 6 months per investigator assessment). Four additional patients switched from weekly to every 2 weeks dosing without meeting the protocol-defined criteria. Of these 4 patients, 2 switched to every 2 weeks dosing due to physician decision (both patients achieved CR or better at the time of the switch but did not meet the protocol-defined time to switch; 1 of these patients had progressive disease before CR so was not considered a responder), and 2 switched due to AEs of neutropenia (1 patient switched due to grade 4 neutropenia at day 322 of the study; the other switched due to grade 3 neutropenia at day 261).

Efficacy outcomes

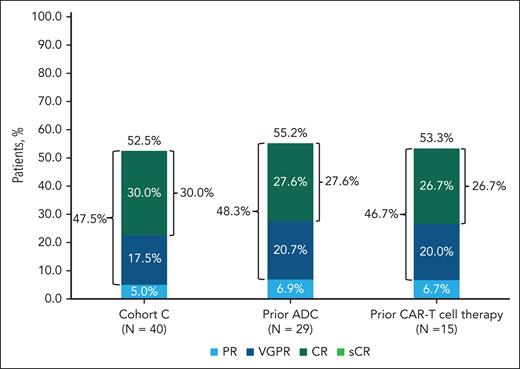

Among patients in cohort C, the ORR was 52.5% (95% CI, 36.1-68.5). Rates of VGPR or better and CR or better were 47.5% (95% CI, 31.5-63.9) and 30.0% (95% CI, 16.6-46.5), respectively (Figure 1). Efficacy was similar in patients with prior BCMA-targeted ADC (ORR, 55.2%; VGPR or better, 48.3%; CR or better, 27.6%) and CAR-T treatment (ORR, 53.3%; VGPR or better, 46.7%; CR or better, 26.7%; Figure 1). Four patients had both prior ADC and prior CAR-T treatment and were included in both groups for response. In 18 patients with prior BCMA-targeting therapy as the last line of therapy, the ORR was 55.6% (VGPR or better, 55.6%; CR or better, 33.3%); and in 22 patients who did not receive an anti-BCMA treatment as the last line of therapy, the ORR was 50.0% (VGPR or better, 40.9%; CR or better, 27.3%). In populations with high unmet need, ORRs were 58.3% (extramedullary disease) and 33.3% (high-risk cytogenetics). ORR was generally similar across subgroups (older patients; renally impaired [creatinine clearance ≤60 mL/min per 1.73 m2]), but small sample size limited the interpretation.

Response to teclistamab in patients with R/RMM who had prior BCMA-targeted therapy (ADC or CAR-T therapy). Rates of sCR, CR, VGPR, and PR in 40 patients who were treated with teclistamab are shown. Differences in percentage totals are due to rounding. Responses were assessed by an independent review committee with a cutoff date of 22 August 2023. PR, partial response; sCR, stringent CR.

Response to teclistamab in patients with R/RMM who had prior BCMA-targeted therapy (ADC or CAR-T therapy). Rates of sCR, CR, VGPR, and PR in 40 patients who were treated with teclistamab are shown. Differences in percentage totals are due to rounding. Responses were assessed by an independent review committee with a cutoff date of 22 August 2023. PR, partial response; sCR, stringent CR.

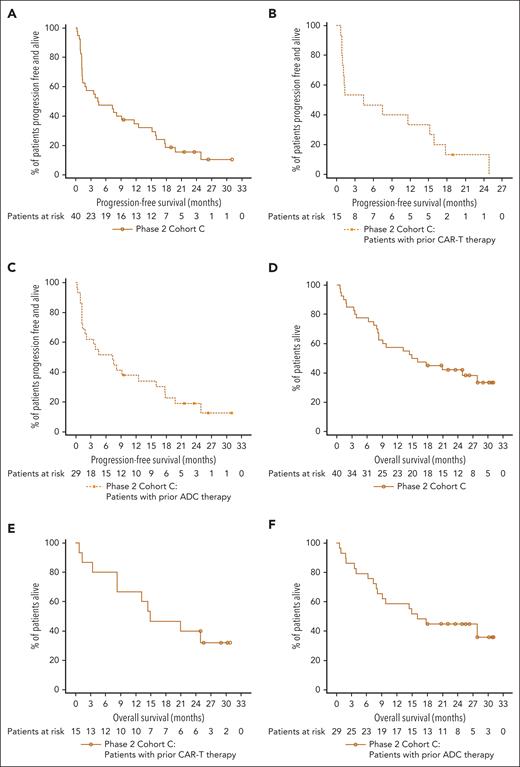

Responses occurred early, deepened over time, and were durable (Figure 2). The median time to first response was 1.2 months (range, 0.2-4.9), the time to best response was 2.9 months (range, 1.1-12.3), and the time to CR or better was 4.0 months (range, 2.1-12.3). The median DOR was 14.8 months (95% CI, 8.0-22.6; supplemental Figure 1A), and the 12-month event-free rate was 61.2% (95% CI, 37.1-78.4). Among patients with CR or better (n = 12), the median DOR was 16.7 months (95% CI, 11.3 to NE). With a median follow-up of 26.3 months (range, 3.6-31.1) among the 21 responders, 5 patients (23.8%) maintained their response to teclistamab, and 3 were still on treatment at clinical cutoff. The median PFS (mPFS) was 4.5 months (95% CI, 1.3-11.6), and the median OS was 15.5 months (95% CI, 8.3-27.9; Figure 3A; 3D). Among 15 patients who received prior CAR-T, the median DOR was 14.4 (95% CI, 2.6 to NE; supplemental Figure 1B), mPFS was 4.4 months (95% CI, 0.9-15.2; Figure 3B), and median OS was 14.9 months (95% CI, 3.4 to NE; Figure 3E); and in 29 patients who received prior ADC, the median DOR was 14.8 (95% CI, 6.2-22.6; supplemental Figure 1C), mPFS was 7.3 months (95% CI, 1.3-16.0; Figure 3C), and median OS was 16.0 months (95% CI, 7.9 to NE; Figure 3F).

Responses over time with subcutaneous teclistamab. Responses in patients occurred early, deepened over time, and were durable. The median time to first response was 1.2 months (range, 0.2-4.9), time to best response was 2.9 months (range, 1.1-12.3), and time to CR or better was 4.0 months (range, 2.1-12.3). D/C, discontinued; PD, progressive disease.

Responses over time with subcutaneous teclistamab. Responses in patients occurred early, deepened over time, and were durable. The median time to first response was 1.2 months (range, 0.2-4.9), time to best response was 2.9 months (range, 1.1-12.3), and time to CR or better was 4.0 months (range, 2.1-12.3). D/C, discontinued; PD, progressive disease.

Kaplan-Meier plots of PFS and OS. Kaplan-Meier plots of PFS for overall cohort C population (N = 40) (A), patients with prior CAR-T therapy (B), and patients with prior ADC therapy (C) and OS for overall cohort C population (N = 40) (D), patients with prior CAR-T therapy (E), and patients with prior ADC therapy (F). The mPFS was 4.5 months (95% CI, 1.3-11.6) in panel A. Among patients who received prior CAR-T, the mPFS was 4.4 months (95% CI, 0.9-15.2) in panel B, and in patients who received prior ADC, the mPFS was 7.3 months (95% CI, 1.3-16.0) in panel C. The median OS was 15.5 months (95% CI, 8.3-27.9) in panel D. Among patients who received prior CAR-T, the median OS was 14.9 months (95% CI, 3.4-NE) in panel E, and in patients who received prior ADC, the median OS was 16.0 months (95% CI, 7.9 to NE) in panel F.

Kaplan-Meier plots of PFS and OS. Kaplan-Meier plots of PFS for overall cohort C population (N = 40) (A), patients with prior CAR-T therapy (B), and patients with prior ADC therapy (C) and OS for overall cohort C population (N = 40) (D), patients with prior CAR-T therapy (E), and patients with prior ADC therapy (F). The mPFS was 4.5 months (95% CI, 1.3-11.6) in panel A. Among patients who received prior CAR-T, the mPFS was 4.4 months (95% CI, 0.9-15.2) in panel B, and in patients who received prior ADC, the mPFS was 7.3 months (95% CI, 1.3-16.0) in panel C. The median OS was 15.5 months (95% CI, 8.3-27.9) in panel D. Among patients who received prior CAR-T, the median OS was 14.9 months (95% CI, 3.4-NE) in panel E, and in patients who received prior ADC, the median OS was 16.0 months (95% CI, 7.9 to NE) in panel F.

The median time from last BCMA-targeted ADC treatment to first dose of teclistamab was shorter for responders (n = 16; 108.5 days [range, 39.0-988.0]) than nonresponders (n = 13; 265.0 days [range, 22.0-1144.0]). The median time from last BCMA-targeted CAR-T treatment to first dose of teclistamab was similar among responders (n = 8; 306.5 days [range, 92.0-950.0]) and nonresponders (n = 7; 303.0 days [range 116.0-579.0]). CAR-T treatment was limited to a 1-day infusion, and persistence of circulating CAR-T from prior therapy was not collected in this study, making these data challenging to interpret.

Seven of 9 patients who switched to less frequent teclistamab dosing did not have progressive disease after schedule change. Five of these 7 patients maintained response at clinical cutoff. Three of these 5 patients remained on treatment, and 2 discontinued; 1 due to a treatment-emergent AE (TEAE) of memory impairment, and 1 refused further study treatment. The other 2 patients died without confirmed disease progression.

Of the 8 of 40 patients (20.0%) who had MRD-evaluable bone marrow samples, 7 (87.5%) with CR or better achieved MRD negativity at any time at a threshold of 10–5.

Safety

The safety profile of teclistamab in cohort C was consistent with the broader MajesTEC-1 population (Table 2). All patients in cohort C experienced ≥1 TEAEs. The most common hematologic AEs were neutropenia, anemia, lymphopenia, and thrombocytopenia (Table 2). Of the 31 patients (77.5%) who had evidence of hypogammaglobulinemia, 16 (40.0%) received IV immunoglobulin treatment at any time during the study according to institutional guidelines. Among nonhematologic AEs, the most common were CRS (65.0%), constipation (37.5%), and diarrhea (37.5%). All CRS events were grade 1 or 2, with median duration of 2 days (range, 1-4; Table 3). All first events of CRS were confined to the step-up dosing schedule or cycle 1, and 12 patients (30.0%) had multiple CRS events (7 had 2 events, 4 experienced 3 events, and 1 patient had 4 events). Twenty-three patients (57.5%) received ≥1 supportive measure to treat CRS, including 12 patients (30%) who received tocilizumab. All CRS events resolved without teclistamab discontinuation.

Safety profile

| AEs ≥10%, n (%) . | Cohort C (N = 40) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade . | Grade 3/4 . | Grade 5 . | |

| Hematologic | |||

| Neutropenia | 28 (70.0) | 26 (65.0) | 0 |

| Anemia | 20 (50.0) | 14 (35.0) | 0 |

| Lymphopenia | 18 (45.0) | 17 (42.5) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 18 (45.0) | 12 (30.0) | 0 |

| Nonhematologic | |||

| Infections and infestations | 28 (70.0) | 13 (32.5) | 4 (10.0) |

| CRS | 26 (65.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 15 (37.5) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Constipation | 15 (37.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 14 (35.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Injection site erythema | 13 (32.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 11 (27.5) | 0 | 0 |

| COVID-19 | 10 (25.0) | 5 (12.5) | 4 (10.0) |

| Dyspnea | 10 (25.0) | 2 (5.0) | 0 |

| Headache | 10 (25.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Asthenia | 9 (22.5) | 2 (5.0) | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal chest pain | 9 (22.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Bone pain | 8 (20.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 8 (20.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Pain in extremity | 8 (20.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Cough | 8 (20.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 7 (17.5) | 3 (7.5) | 0 |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 7 (17.5) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 7 (17.5) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Back pain | 7 (17.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 6 (15.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Hypocalcemia | 6 (15.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 6 (15.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Injection site pruritus | 6 (15.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 5 (12.5) | 2 (5.0) | 0 |

| Acute kidney injury | 4 (10.0) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (2.5) |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

| Cardiac failure | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

| Coronary artery dissection | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

| AEs ≥10%, n (%) . | Cohort C (N = 40) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade . | Grade 3/4 . | Grade 5 . | |

| Hematologic | |||

| Neutropenia | 28 (70.0) | 26 (65.0) | 0 |

| Anemia | 20 (50.0) | 14 (35.0) | 0 |

| Lymphopenia | 18 (45.0) | 17 (42.5) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 18 (45.0) | 12 (30.0) | 0 |

| Nonhematologic | |||

| Infections and infestations | 28 (70.0) | 13 (32.5) | 4 (10.0) |

| CRS | 26 (65.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 15 (37.5) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Constipation | 15 (37.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 14 (35.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Injection site erythema | 13 (32.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 11 (27.5) | 0 | 0 |

| COVID-19 | 10 (25.0) | 5 (12.5) | 4 (10.0) |

| Dyspnea | 10 (25.0) | 2 (5.0) | 0 |

| Headache | 10 (25.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Asthenia | 9 (22.5) | 2 (5.0) | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal chest pain | 9 (22.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Bone pain | 8 (20.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 8 (20.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Pain in extremity | 8 (20.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Cough | 8 (20.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 7 (17.5) | 3 (7.5) | 0 |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 7 (17.5) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 7 (17.5) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Back pain | 7 (17.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 6 (15.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Hypocalcemia | 6 (15.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 6 (15.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Injection site pruritus | 6 (15.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 5 (12.5) | 2 (5.0) | 0 |

| Acute kidney injury | 4 (10.0) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (2.5) |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

| Cardiac failure | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

| Coronary artery dissection | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

CRS

| Parameter . | Cohort C (N = 40) . |

|---|---|

| Patients with CRS, n (%)∗ | 26 (65.0) |

| Grade 1 | 21 (52.5) |

| Grade 2 | 5 (12.5) |

| Grade ≥3 | 0 |

| Patients with ≥2 CRS events, n (%) | 12 (30.0) |

| Time to onset, median (range), d | 2 (2-6) |

| Duration, median (range), d | 2 (1-4) |

| Received supportive measures†for CRS, n (%) | 23 (57.5) |

| Tocilizumab | 12 (30.0) |

| Low-flow oxygen by nasal cannula‡ | 4 (10.0) |

| IV fluids | 2 (5.0) |

| Corticosteroids | 1 (2.5) |

| Parameter . | Cohort C (N = 40) . |

|---|---|

| Patients with CRS, n (%)∗ | 26 (65.0) |

| Grade 1 | 21 (52.5) |

| Grade 2 | 5 (12.5) |

| Grade ≥3 | 0 |

| Patients with ≥2 CRS events, n (%) | 12 (30.0) |

| Time to onset, median (range), d | 2 (2-6) |

| Duration, median (range), d | 2 (1-4) |

| Received supportive measures†for CRS, n (%) | 23 (57.5) |

| Tocilizumab | 12 (30.0) |

| Low-flow oxygen by nasal cannula‡ | 4 (10.0) |

| IV fluids | 2 (5.0) |

| Corticosteroids | 1 (2.5) |

CRS was graded using American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy criteria in phase 2.

A patient could receive >1 supportive therapy.

Less than or equal to 6 L/min.

Treatment-emergent neurotoxicity events were experienced by 11 patients (9 had 1 event; 2 experienced 2 events). The most common neurotoxic event was headache (12.5%; Table 4). Of 13 events of neurotoxicity, 8 (61.5%) were resolved or recovered; 1 was recovering or resolving at data cutoff; and 4 events did not resolve (2 cases of dysgeusia, 1 of insomnia, and 1 of peripheral sensory neuropathy). Two events (5.0%) led to teclistamab dose interruption (ICANS and peripheral sensory neuropathy), but no patient had dose reductions or treatment discontinuation. Four patients (10%) experienced ICANS events (Table 4), all concurrently with CRS. ICANS events were grade 1/2 in 3 patients and grade 3 in 1 patient. All ICANS events resolved.

Neurotoxic events

| Parameter . | Cohort C (N = 40) . |

|---|---|

| Neurotoxic event∗, n (%) | 11 (27.5) |

| Headache | 5 (12.5) |

| ICANS | 4 (10.0) |

| Dysgeusia | 2 (5.0) |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 1 (2.5) |

| Insomnia | 1 (2.5) |

| Grade ≥3 events, n (%) | 1 (2.5) |

| Time to onset, median (range), d | 2 (1–29) |

| Duration, median (range), d | 2 (1–35) |

| Received supportive measures for neurotoxic events, n (%)† | 7 (17.5) |

| Tocilizumab | 2 (5.0) |

| Anakinra | 1 (2.5) |

| Dexamethasone | 1 (2.5) |

| Pregabalin | 1 (2.5) |

| Other | 6 (15.0) |

| Parameter . | Cohort C (N = 40) . |

|---|---|

| Neurotoxic event∗, n (%) | 11 (27.5) |

| Headache | 5 (12.5) |

| ICANS | 4 (10.0) |

| Dysgeusia | 2 (5.0) |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 1 (2.5) |

| Insomnia | 1 (2.5) |

| Grade ≥3 events, n (%) | 1 (2.5) |

| Time to onset, median (range), d | 2 (1–29) |

| Duration, median (range), d | 2 (1–35) |

| Received supportive measures for neurotoxic events, n (%)† | 7 (17.5) |

| Tocilizumab | 2 (5.0) |

| Anakinra | 1 (2.5) |

| Dexamethasone | 1 (2.5) |

| Pregabalin | 1 (2.5) |

| Other | 6 (15.0) |

Neurotoxic events were defined as AEs under the “nervous system disorder” or “psychiatric disorder” system organ class that were judged by the investigator to be related to study drug, including ICANS events.

Tocilizumab, anakinra, and dexamethasone were used to treat ICANS events.

Infections occurred in 28 patients (70.0%; maximum grade 3/4, n = 13 [32.5%]; grade 5, n = 4 [10%]). All 4 grade 5 infections were coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19); 3 patients had received at least 1 COVID-19 vaccination before teclistamab treatment, and 1 patient had no record of prior COVID-19 vaccination. Patient recruitment in cohort C began in October 2020, running concurrently with the COVID-19 pandemic and overlapping with peak infection and death rates worldwide, based on World Health Organization data.21

Three patients (7.5%) discontinued teclistamab due to AEs; 1 was considered treatment related by the investigator (hepatitis E virus infection). No patients had a dose reduction of teclistamab. Twenty-five patients (62.5%) died, with disease progression as the primary cause of death in 12 patients (30.0%). Of the 10 grade 5 TEAEs, 8 (20.0%) had the cause of death reported as AEs, including COVID-19 (n = 4; 10%), and 1 (2.5%) each for cardiac arrest, cardiac failure, coronary artery dissection, and sudden death. Two patients (5.0%) died due to events that investigators considered related to teclistamab treatment (1 COVID-19 and 1 cardiac arrest). The other 2 grade 5 AEs were due to disease progression. The patient who suffered cardiac arrest had ongoing pneumonia, which started 10 days before death.

PK and immunogenicity

Teclistamab Ctrough values in patients in cohort C were comparable with observed concentrations in BCMA-treatment–naive patients, and the mean teclistamab Ctrough was maintained above the maximum 90% effective concentration value identified in an ex vivo cytotoxicity assay using bone marrow mononuclear cells from patients with MM. Teclistamab serum concentrations at or within 48 hours of CRS event onset (including step-up and treatment doses) ranged from 0.070 to 8.99 μg/mL. Based on the available data (PK data cutoff 7 June 2023), there was no clear correlation between the presence or grade of CRS and teclistamab concentration. In addition, teclistamab serum concentrations were comparable in patients who experienced CRS across all grades and patients for whom CRS was not reported. No serum sample collected during a CRS event was identified to be positive for antibodies to teclistamab, indicating a lack of correlation between CRS and immunogenicity.

None of the 36 patients who were antidrug antibody evaluable in cohort C were identified as positive for antibodies to teclistamab.

sBCMA and bone marrow BCMA expression

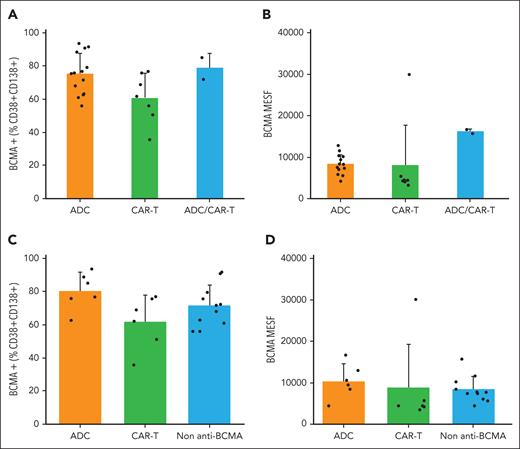

The range of baseline sBCMA in serum overlapped between patients in cohort C (2.7-1754.8 μg/L) and in BCMA-treatment–naive patients. Within the cohort C population, the median baseline sBCMA levels were lower in patients who previously received CAR-T (56.8 μg/L [range, 2.7-747.9]) vs ADC (148.3 μg/L [range, 6.2-1754.8]) anti-BCMA treatment (P = .037; Figure 4A) and in patients who responded to prior anti-BCMA treatment (87.0 [2.7-747.9] μg/L) compared with those who did not (148.3 μg/L [range, 6.4-1754.8]; P = .290; Figure 4B). After teclistamab dosing in cohort C, most responders showed a decrease in sBCMA on cycle 4 day 1 (11/14 [78.6%]), whereas the majority of nonresponders showed an increase in sBCMA on cycle 4 day 1 (3/4 [75%]) compared with baseline values. The trend from earlier studies showing greater reduction in sBCMA in patients with deeper responses to teclistamab22 was also observed in cohort C (Figure 4C), although the sample size was limited. We also examined the BCMA expression on MM cells in the bone marrow and found there was no significant difference in the percentage of tumor cells expressing BCMA or the expression level of BCMA on tumor cells in patients who previously received anti-BCMA CAR-T or ADC, either as the last prior line or any prior line (Figure 5).

Soluble BCMA levels. sBCMA levels at baseline, by any prior anti-BCMA therapies (all treated analysis set, cohort C) (A), baseline by responder to any prior anti-BCMA treatment (all treated analysis set, cohort C) (B); and percent change from baseline in sBCMA level at cycle 4 day 1 by best response as assessed by independent review committee (C). The box plots display boxes in which the top sides are quantile 3 (Q3), the center lines are median, and the bottom sides are Q1. The means are displayed as diamonds in Figure 5C. The lines extending above and below the boxes go to the maximum and minimum values that are within the upper (Q3 + 1.5 × interquartile range [IQR]) and lower fence (Q1 – 1.5 × IQR). Data points beyond the fences represent outlier values.

Soluble BCMA levels. sBCMA levels at baseline, by any prior anti-BCMA therapies (all treated analysis set, cohort C) (A), baseline by responder to any prior anti-BCMA treatment (all treated analysis set, cohort C) (B); and percent change from baseline in sBCMA level at cycle 4 day 1 by best response as assessed by independent review committee (C). The box plots display boxes in which the top sides are quantile 3 (Q3), the center lines are median, and the bottom sides are Q1. The means are displayed as diamonds in Figure 5C. The lines extending above and below the boxes go to the maximum and minimum values that are within the upper (Q3 + 1.5 × interquartile range [IQR]) and lower fence (Q1 – 1.5 × IQR). Data points beyond the fences represent outlier values.

Baseline tumor BCMA expression. Baseline tumor BCMA expression was assessed in MM cells in the bone marrow for BCMA+ (%CD38+CD138+) (A); and BCMA MESF for all patients by anti-BCMA types, any prior line (ADC, CAR-T, and ADC/CAR-T) (B); and BCMA+ (%CD38+CD138+) (C); and BCMA MESF for all patients by anti-BCMA types, last prior line (ADC, CAR-T, and non–anti-BCMA) (D). No significant difference was observed in the percentage of tumor cells expressing BCMA or the expression level of BCMA on tumor cells in patients who previously received anti-BCMA CAR-T or ADC, either as the last prior line or any prior line. MESF, molecules of equivalent soluble fluorochrome.

Baseline tumor BCMA expression. Baseline tumor BCMA expression was assessed in MM cells in the bone marrow for BCMA+ (%CD38+CD138+) (A); and BCMA MESF for all patients by anti-BCMA types, any prior line (ADC, CAR-T, and ADC/CAR-T) (B); and BCMA+ (%CD38+CD138+) (C); and BCMA MESF for all patients by anti-BCMA types, last prior line (ADC, CAR-T, and non–anti-BCMA) (D). No significant difference was observed in the percentage of tumor cells expressing BCMA or the expression level of BCMA on tumor cells in patients who previously received anti-BCMA CAR-T or ADC, either as the last prior line or any prior line. MESF, molecules of equivalent soluble fluorochrome.

Immune cell effects

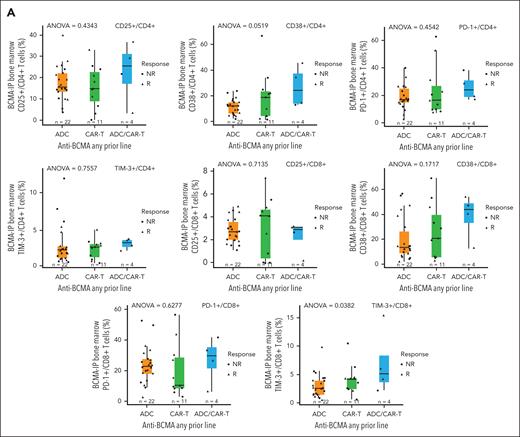

The impact of prior anti-BCMA CAR-T therapy on T-cell numbers and the activation and inhibitory receptor expression on T cells before teclistamab treatment were assessed. We hypothesized that T cells in patients receiving prior CAR-T therapy would be exhausted at baseline. Baseline CD4 and CD8 T-cell numbers trended lower in patients who received prior anti-BCMA CAR-T than in those receiving prior BCMA-ADC therapy (data not shown). However, we found that the expression of activation markers (CD25 and CD38) and inhibitory receptors (Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 [PD-1] and T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3 [TIM-3]) was not upregulated on CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from patients receiving a prior anti-BCMA CAR-T at any point during treatment, or as the last line before teclistamab treatment compared with patients receiving prior BCMA-ADC therapy (Figure 6A-B).

T-cell profile at baseline. Activation/inhibitory receptor expression on T cells was assessed for patients with any prior anti-BCMA (A) or by the last prior anti-BCMA (all treated analysis set; cohort C) (B). Baseline CD4 and CD8 T-cell numbers trended lower in patients who received prior anti-BCMA CAR-T than those receiving prior BCMA-ADC therapy. However, expression of activation markers and inhibitory receptors was not upregulated on T cells from patients receiving a prior anti-BCMA CAR-T at any point during treatment or as the last line before teclistamab treatment compared with patients receiving prior BCMA-ADC therapy. The ANOVA tests assessed differences among groups of ADC, CAR-T, and ADC/CAR-T (A) and ADC, CAR-T, and non–anti-BCMA (B). ANOVA, analysis of variance; NR, Nonresponder; R, Responder.

T-cell profile at baseline. Activation/inhibitory receptor expression on T cells was assessed for patients with any prior anti-BCMA (A) or by the last prior anti-BCMA (all treated analysis set; cohort C) (B). Baseline CD4 and CD8 T-cell numbers trended lower in patients who received prior anti-BCMA CAR-T than those receiving prior BCMA-ADC therapy. However, expression of activation markers and inhibitory receptors was not upregulated on T cells from patients receiving a prior anti-BCMA CAR-T at any point during treatment or as the last line before teclistamab treatment compared with patients receiving prior BCMA-ADC therapy. The ANOVA tests assessed differences among groups of ADC, CAR-T, and ADC/CAR-T (A) and ADC, CAR-T, and non–anti-BCMA (B). ANOVA, analysis of variance; NR, Nonresponder; R, Responder.

B-cell numbers were also evaluated, because emerging data suggest anti-BCMA therapies reduce B-cell number.23,24 We, therefore, hypothesized that prior anti-BCMA therapy may result in smaller B-cell numbers at baseline. However, patients receiving prior anti-BCMA therapies at any point during treatment did not have lower B-cell numbers at baseline than patients who were anti-BCMA naive, suggesting B-cell recovery over time (Figure 7).

B-cell numbers evaluated in patients (pivotal R2PD and cohort C) at baseline. Patients receiving prior anti-BCMA therapies at any point during treatment did not have lower B-cell numbers at baseline. These findings for patients in cohort C (n = 24) are similar to those observed for the pivotal RP2D population (anti-BCMA therapy–naive population; n = 76). RP2D, recommended phase 2 dose.

B-cell numbers evaluated in patients (pivotal R2PD and cohort C) at baseline. Patients receiving prior anti-BCMA therapies at any point during treatment did not have lower B-cell numbers at baseline. These findings for patients in cohort C (n = 24) are similar to those observed for the pivotal RP2D population (anti-BCMA therapy–naive population; n = 76). RP2D, recommended phase 2 dose.

Discussion

Generally, patients with R/RMM progress through multiple treatments, and as new treatments become more widely available, exposure to anti-BCMA therapies will become more prevalent. The outcomes of teclistamab treatment after prior anti-BCMA therapy were evaluated in cohort C of the MajesTEC-1 trial. Efficacy outcomes were similar between those who received prior BCMA-targeted ADC therapy vs CAR-T therapies. This finding suggests that responses with teclistamab can be achieved after prior T-cell redirection therapy, although additional studies with larger patient numbers are needed.

Recent real-world studies of patients who received teclistamab after prior exposure to BCMA-directed therapy have shown similar outcomes. ORRs of 53% and 59% were reported, albeit with a shorter follow-up than with cohort C (3.8 and 5.0 vs 28.0 months).25,26 Similar efficacy findings from MajesTEC-1 cohort C and real-world evidence suggest that teclistamab can provide clinically meaningful improvements to patients with R/RMM who have previously progressed on other BCMA-targeting therapies, a growing population with unmet need.

Although crosstrial comparisons should be undertaken with caution due to differences in patient eligibility criteria and study design, efficacy outcomes observed among patients from cohort C of MajesTEC-1 are similar to or compare favorably with those observed with other novel agents after anti-BCMA therapy. In studies of patients treated with non–BCMA-targeted therapies after prior exposure to anti-BCMA therapies, ORRs of 25% to 72.9% were reported with iberdomide + dexamethasone,27 selinexor-based combinations,28 cevostamab,29 forimtamig,30 and talquetamab.31 In patients treated with cevostamab, an Fc receptor–homolog 5 bispecific antibody, an ORR of 36.4% was achieved in patients with prior anti-BCMA treatment. Among bispecific antibodies targeting G protein–coupled receptor class C group 5 member D, forimtamig showed an ORR of 51.2% in BCMA-exposed patients,30 and talquetamab demonstrated ORRs of 72.9% and 56.5% in patients exposed to prior BCMA CAR-T and BCMA bispecific antibodies, respectively.31 Together, these results suggest that prior BCMA-targeted therapy does not appear to negatively affect responses to subsequent novel agents with targets other than BCMA, although it will be important to follow the durability of this response as data mature.

Response rates with BCMA-targeted therapies were generally lower in patients who had prior anti-BCMA therapies compared with BCMA-naive patients. With elranatamab, another BCMA-directed bispecific antibody, an ORR of 33.3% (vs 57.7% in BCMA-naive patients) was achieved in patients with prior exposure to anti-BCMA therapies (73% had prior ADC, and 32% had prior CAR-T).17 BCMA-exposed patients who received ciltacabtagene autoleucel had an ORR of 60% (61.5% ORR in ADC exposed and 57.1% in bispecific antibody exposed) compared with an ORR of 97% in BCMA-naive patients.20 A multicenter retrospective study showed that patients receiving prior BCMA-directed therapies before treatment with idecabtagene vicleucel had a lower ORR (74% vs 88%; P = .021) than those without prior BCMA-directed therapies.32 Generally, our data suggest teclistamab after BCMA-targeted ADCs or CAR-T is a viable treatment option. The mPFS in this population was 4.5 months, lower than the 11.3 months observed in BCMA-naive patients in the MajesTEC-1 RP2D cohort. However, an ORR of 52.5% and a CR or better rate of 30.0% were observed, which was promising given that two-thirds of the patients in cohort C were BCMA refractory, and responses were not appreciably lower than that seen in the MajesTEC-1 RP2D cohort (ORR of 63% and CR or better rate of 39.4%). Furthermore, the median DOR in patients treated with prior BCMA-targeted therapy who achieved CR or better was 16.7 months (95% CI, 11.3 to NE), showing durability of deep responses. The small data sets reported here and in the literature make clinical interpretation challenging regarding the optimum timing between BCMA-directed therapies, and more research is needed, given the heterogeneity of BCMA-targeted treatment constructs and timing between subsequent administrations.

The safety profile of teclistamab in cohort C was generally consistent with that of patients without prior exposure to anti-BCMA therapy in the RP2D cohort of MajesTEC-1 and in the real-world setting.10,25,26 The incidence and severity of CRS was comparable between cohort C (65.0% [grade 1, 52.5%; grade 2, 12.5%]), the RP2D cohort of MajesTEC-1 (72.1% [grade 1, 50.3%; grade 2, 21.1%; grade 3, 0.6%]),10 and real-world studies (in Tan et al, 53.9% [grade 1, 41.2%; grade 2, 12.3%; grade ≥3, 0.5%]; and in Dima et al, 64.0% [grade 1, 54.0%; grade 2, 9%; grade 3, 1.0%]).25,33 The percentage of patients experiencing ICANS events was lower in the overall MajesTEC-1 RP2D population (3.0%) than in cohort C (10%) or the real-world population (14%).25 It should be noted, however, that although real-world evidence provides essential context that complements studies, real-world follow-up times are much shorter than that of the MajesTEC-1 trial (3-5 months vs 28 months, respectively).

Treatment-emergent infections of any grade were common in cohort C (70.0% of patients, with 32.5% experiencing maximum grade 3 or 4 events and 42.5% experiencing any grade 3 or 4 events) and similar to the rates observed in the overall MajesTEC-1 population at 14.1 months of follow-up (76.4% of patients, with 44.8% experiencing any grade 3 or 4 events).10 Enrollment of the RP2D cohort of MajesTEC-1 began concurrently with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, which likely affected outcomes as reflected in all 4 grade 5 infections being due to COVID-19. Given the timing of MajesTEC-1, no COVID-19 vaccines were available until 9 months after enrollment began, and in cohort C, only 3 patients had received at least 1 COVID-19 vaccination before teclistamab treatment.

Building on experiences from the pivotal RP2D population of MajesTEC-1,10,34 and in line with recently published guidelines,35-37 several recommendations for infection management during teclistamab treatment emerged,38 including up-to-date vaccinations, screening for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV infection, and use of prophylactic antimicrobials. Further recommendations include close monitoring of infections and immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels throughout teclistamab treatment and the use of IgG replacement (every 3-6 weeks) to maintain IgG levels ≥400 mg/dL. In addition, a decrease in teclistamab dosing frequency may be a strategy for improving infection risk. A reduction in new-onset grade ≥3 infections was observed over time, roughly corresponding to the median time at which patients switched to less frequent dosing (11.3 months), with no impact on efficacy.38 Recent real-world infection rates reported in teclistamab-treated patients with R/RMM ranged from 31% to 60%25,26 and were lower than those seen in the MajesTEC-1 RP2D cohort10 and cohort C. These findings may be reflective of timing (eg, when the COVID-19 pandemic was under better control) and the availability of infection management/mitigation recommendations.

There are several important limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. MajesTEC-1 was a single-arm study, and the sample size of cohort C was relatively small, especially when patients were segmented by type of prior anti-BCMA therapy (ADC or CAR-T). Furthermore, there was substantial heterogeneity in terms of duration and timing of prior treatment, including whether BCMA-targeting therapy was given as the immediate prior line or an earlier line of therapy. Despite these limitations, the results of cohort C add to the growing body of evidence that can be used to optimize treatment sequencing in patients with R/RMM.

In conclusion, results from cohort C of the MajesTEC-1 trial showed that patients with heavily pretreated R/RMM, including those with prior anti-BCMA therapy, can respond to treatment with teclistamab, with >50% of patients achieving a response. Deep responses translated to durable responses, with median duration of therapy of 16.7 months among the 30% of patients who achieved CR or better. Teclistamab exhibited a similar safety profile in anti-BCMA–exposed and BCMA-naive settings. These results provide important data to clinicians regarding the potential clinical benefit of teclistamab after prior anti-BCMA therapy as previous exposure to such therapies becomes more prevalent among patients with R/RMM.

Acknowledgment

Editorial and medical writing support was provided by Eloquent Scientific Solutions and was funded by Janssen Global Services, LLC.

Authorship

Contribution: All authors contributed to the study design, study conduct, and data analysis and interpretation and participated in drafting and revising the manuscript and approved the final version for submission; and A.L.G. had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.T. received honoraria from and participated in advisory boards for Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Sanofi, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Amgen, AbbVie, and Pfizer; and received research funding from Sanofi, and GSK. A.Y.K. received research funding from Janssen; holds equity in BMS; served as a consultant for Adaptive, Janssen, Sanofi, BMS, Pfizer, and Regeneron; served on a speakers bureau for Takeda, GSK, and BMS; and served on an advisory committee for Sutro. P.M. has served in a consulting or advisory role for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, GSK, Janssen, Oncopeptides, and Sanofi; and has received honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, GSK, Janssen-Cilag, Oncopeptides, and Sanofi. A.P. served in a consulting role and received honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen-Cilag, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda. S.Z.U. has served in a consulting or advisory role for AbbVie, Amgen, BMS/Celgene, Celgene, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, GSK, Janssen, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Merck, and Takeda; and has received research funding from Amgen, Array BioPharma, BMS, Celgene, GSK, Janssen, Merck, Pharmacyclics, Sanofi, Seattle Genetics, and Skyline Diagnostics. S.M. received research funding from AbbVie, Celgene/BMS, Janssen, Novartis, and Takeda. M.C. received honoraria from Janssen, Celgene/BMS, Sanofi, Takeda, Amgen, AbbVie, Adaptive, and GSK; and served on a speakers bureau for Janssen and Celgene/BMS. A.K.N. reports consultancy and honoraria for BMS, Janssen, Takeda, Amgen, Adaptive, GSK, Sanofi, Oncopeptides, Karyophram, SecureBio, and BeyondSpring. T.G.M. has served as a consultant or in an advisory role for GSK; and has received research funding from Sanofi, Amgen, and Janssen Oncology. L.K. has served in a consulting/advisory role for Amgen, Janssen, Celgene/BMS, GSK, Sanofi, Stemline, Takeda, and AbbVie; received honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene/BMS, GSK, Janssen, Sanofi, Stemline, and Takeda; has received travel expenses from Amgen, Celgene/BMS, Janssen, Sanofi, and Takeda; and has an immediate family member employed by Laboratoire Aguettant. X.L. held a consulting or advisory role for AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, CARsgen, Celgene, Gilead, GSK, Janssen-Cilag, Karyopharm, Merck, Novartis, Oncopeptides, Roche, and Takeda; received travel, accommodations, and/or expenses from Takeda; and received honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, CARsgen, Celgene, GSK, Janssen-Cilag, Karyopharm, Merck, Novartis, Oncopeptides, Roche, Sanofi, and Takeda. N.J.B. has served in a consulting/advisory role for Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda; received honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Genentech/Roche, GSK, Janssen, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Sanofi, and Takeda; and has received research funding from Celgene and Janssen. B.B. has received travel, accommodations, and expenses and received honoraria from Amgen, GSK, Janssen-Cilag, Pfizer, and Sanofi. D.T., K.C., L.P., S.S., and X.M. are employees of Janssen. C.M.U., R.I.V., S.G., and S.X.W.L. were employees of Janssen at the time the work was carried out and may have stock/other ownership interests in Janssen. A.L.G. served as a consultant for Janssen, GSK, Amgen, Novartis, and AbbVie; received research funding from Janssen, Novartis, Tmunity, and CRISPR Therapeutics; and served on an independent data monitoring committee for Janssen. C.M.-C. declares no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for S.X.W.L is LiniDose Medicine Co., Ltd., Nanjing, Jiangsu, China.

The current affiliation for R.I.V is AbbVie, Philadelphia, PA.

The current affiliation for S.G. is Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, PA.

The current affiliation for X.M. is Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, PA.

Correspondence: Cyrille Touzeau, Service d’Hématologie Clinique, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Place Alexis Ricordeau, 44093 Nantes, France; email: cyrille.touzeau@chu-nantes.fr.

References

Author notes

The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the study data can be submitted through the Yale Open Data Access Project site available at http://yoda.yale.edu.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![Soluble BCMA levels. sBCMA levels at baseline, by any prior anti-BCMA therapies (all treated analysis set, cohort C) (A), baseline by responder to any prior anti-BCMA treatment (all treated analysis set, cohort C) (B); and percent change from baseline in sBCMA level at cycle 4 day 1 by best response as assessed by independent review committee (C). The box plots display boxes in which the top sides are quantile 3 (Q3), the center lines are median, and the bottom sides are Q1. The means are displayed as diamonds in Figure 5C. The lines extending above and below the boxes go to the maximum and minimum values that are within the upper (Q3 + 1.5 × interquartile range [IQR]) and lower fence (Q1 – 1.5 × IQR). Data points beyond the fences represent outlier values.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/144/23/10.1182_blood.2023023616/2/m_blood_bld-2023-023616-gr4.jpeg?Expires=1767935520&Signature=oUdEsBCTmvwC6T4FWHH510Y7xFOyz7NemJR2lsSoc0uUzw2GcCPrZDwgl-1Jst8JcTxmH5D~YB8MO1qySYChAlfcpN2KF7WyO7ZoHiicjW7ChjruSfMhKnkygUXTiuKZAbaauQlEaqu47Zckxc3X8XVJ26uZ3XiUSVUq2EV156bqQM5oLZoYOZnPsuNElOmwHB9DwNyfw8xslkDBjI9NeL9rVyF43NiI07C8RNLFnzPjWPCz127~zvlmVEJh1KY-QojkwucDaKsTjM5wm2-kv1Wz2BFitvw9X8aQT7Uz6KMvpkXfIQImR4OKlPgZA58SYOYircc89DH5zjAicnuL7Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal