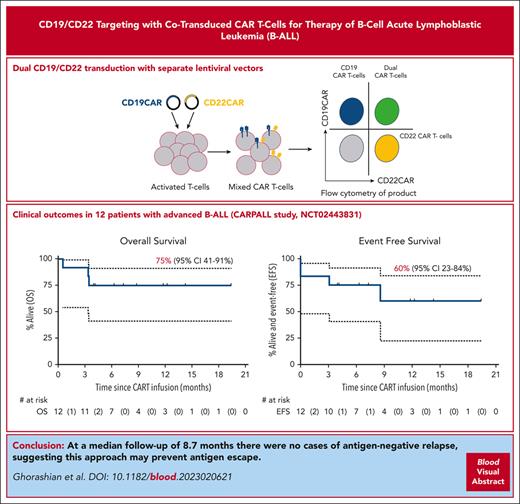

Dual-targeting CAR T cells cotransduced with CD19 and CD22 CARs were used to treat 12 patients with relapsed/refractory ALL with a 1-year EFS of 60%.

At a median follow-up of 8.7 months, there were no cases of antigen-negative relapse, suggesting this approach may prevent antigen escape.

Visual Abstract

CD19-negative relapse is a leading cause of treatment failure after chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. We investigated a CAR T-cell product targeting CD19 and CD22 generated by lentiviral cotransduction with vectors encoding our previously described fast-off rate CD19 CAR (AUTO1) combined with a novel CD22 CAR capable of effective signaling at low antigen density. Twelve patients with advanced B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia were treated (CARPALL [Immunotherapy with CD19/22 CAR Redirected T Cells for High Risk/Relapsed Paediatric CD19+ and/or CD22+ Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia] study, NCT02443831), a third of whom had failed prior licensed CAR therapy. Toxicity was similar to that of AUTO1 alone, with no cases of severe cytokine release syndrome. Of 12 patients, 10 (83%) achieved a measurable residual disease (MRD)–negative complete remission at 2 months after infusion. Of 10 responding patients, 5 had emergence of MRD (n = 2) or relapse (n = 3) with CD19- and CD22-expressing disease associated with loss of CAR T-cell persistence. With a median follow-up of 8.7 months, there were no cases of relapse due to antigen-negative escape. Overall survival was 75% (95% confidence interval [CI], 41%-91%) at 6 and 12 months. The 6- and 12-month event-free survival rates were 75% (95% CI, 41%-91%) and 60% (95% CI, 23%-84%), respectively. These data suggest dual targeting with cotransduction may prevent antigen-negative relapse after CAR T-cell therapy.

Introduction

CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has transformed relapsed/refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) outcomes. However, event-free survival (EFS) is 40% to 50%,1-4 and antigen loss is a key cause of treatment failure (36%-68% of cases).1,3,4 For example, AUTO1, a fast-off rate CD19 CAR T-cell therapy, previously demonstrated therapeutic efficacy, favorable safety, and excellent persistence,5 but 5 of 14 treated patients relapsed with CD19-negative leukemia. Dual-antigen targeting of both CD19 and CD22 represents a logical approach to preventing this. A variety of dual-targeting approaches have been tested, but to date none has improved on ELIANA outcomes or entirely eradicated antigen-negative relapse.

Relapses after CD22 CAR infusion are associated with CD22 downregulation.6,7 We developed a highly sensitive CD22 CAR responding to low CD22 levels (250 molecules per cell8). We incorporated this into a novel CAR T-cell product generated by cotransduction of T cells with separate lentiviral vectors encoding the CD19 and CD22 CARs, resulting in a product containing single- and dual-transduced populations. Unlike other dual CAR formats,9 our CD19/CD22 CAR T cells effectively targeted CD19-negative NALM6 leukemia, demonstrating the efficacy of the CD22 component. We have now tested these CD19/CD22 cotransduced CAR T cells in children with relapsed/refractory ALL in a phase 1/2 study.

Study design

The CARPALL study (NCT02443831) was a University College London (UCL) sponsored, academic, multicenter, single-arm, open-label phase 1 study. Details of CAR T-cell manufacture, study design, and analyses are in the supplemental Material (available on the Blood website). Patients (aged ≤24 years) with high-risk, relapsed CD19+ and/or CD22+ hematological malignancies were eligible. All enrolled had B-cell ALL. Patients received a single dose of 106 CAR-positive T cells/kg following lymphodepletion with fludarabine/cyclophosphamide. Primary end points were incidence of grade 3 to 5 toxicity, causally associated with CAR T cells, and proportion of patients achieving a molecular measurable residual disease (MRD)–negative bone marrow remission with complete response of disease at any relevant extramedullary sites, (assessed radiologically or by evaluation of the cerebrospinal fluid). Overall survival (OS) was the time from infusion to time of death. Patients were censored on day last seen alive. EFS was defined as in the ELIANA study: events included no response, morphologic relapse after having complete remission with or without incomplete hematologic recovery (CR/CRi), or death, whichever occurred first. Patients were censored if they received further therapy or at the date last seen alive. EFS was also more stringently defined where emergence of MRD and need for further therapy were included as events. Clinical data were analyzed in STATA 17.0 with time-to-event outcomes per Kaplan-Meier analysis. Toxicity was reported using maximum grade experienced with cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity due to immune effector cell–related cytotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), graded as per American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy.10

Informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from all patients or their guardians following in-depth discussion and reading of study Patient/Parent Information Leaflets that were approved by the Research Ethics Committee.

Results and discussion

All 13 screened patients were enrolled, and a CAR T-cell product was generated (supplemental Figure 1). One patient withdrew before lymphodepletion (uncontrolled adenoviremia). Median transduction efficiency, based on expression of either or both CARs, was 83.2% (range, 60.8%-92.6%). Products showed a predominance of central memory (central memory T cells median, 91.5%; range, 50.3%-95.5%; naive/stem cell memory T cells [Tn/scm] median, 0.5%; range, 0.06%-1.3%; supplemental Figure 2A). Most CAR T cells were CD19/CD22 dual-transduced T cells (median, 54.4%; range, 14.1%-70.0%) with lower, balanced populations of CD19 (median, 13.1%) and CD22 (median, 11.6%) single-positive CAR T cells (supplemental Figure 2B).

Median patient age was 12 years (range, 3.7-20.5 years). This was a heavily pretreated cohort with a median of 3 prior therapies (range, 2-6). Half had relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplant (allo-SCT), 4 after tisagenlecleucel. Three patients had CD19-negative disease, 1 of whom had an additional 5% CD22-negative population (Table 1). All patients were ineligible for tisagenlecleucel.

Patients’ characteristics

| Patient no. . | Disease status at enrollment . | EM disease at enrollment . | Previous SCT . | Previous tisagenlecleucel . | Previous blinatumomab/inotuzumab . | Lines of treatment before CARPALL . | Disease level by flow/mol MRD before lymphodepletion . | CD19/CD22 expression at enrollment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Second relapse | No | No | Yes | Yes/yes | 6 | 0.12% 1.3 × 10−3 | +/+ |

| 2 | Second relapse | CNS | Yes | No | Yes/no | 5 | 0.39% 1 × 10−2 | +/+ |

| 3 | Third relapse | No | Yes | Yes | No/no | 6 | ND/6 × 10−2 | +/+ |

| 4 | Second relapse | CNS | Yes | No | No/no | 3 | 0.069% 7 × 10−4 | +/+ |

| 5 | Second relapse | CNS | Yes | No | No/no | 3 | Negative/negative | +/+ |

| 6 | Second relapse | No | Yes | Yes | Yes/no | 4 | 85% | +/+ |

| 7 | Second relapse | Adenopathy/pelvic mass | No | No | Yes/yes | 3 | 12% 2.8 × 10−1 | 10% Blasts CD19 neg/+ |

| 8 | First relapse | No | No | No | No/no | 2 | 2.3%/ND | Neg/+ |

| 9 | Second relapse | No | No | Yes | No/no | 4 | 18.6% | 100% Blasts CD19 neg/5% blasts CD22 neg |

| 10 | Second relapse | Chest wall | Yes | No | Yes/no | 3 | Negative/negative | +/+ |

| 11 | First relapse | CNS and spine | No | No | Yes/no | 3 | 7.4% | +/+ |

| 12 | First relapse | CNS | No | No | No/no | 2 | Negative/negative | +/+ |

| Patient no. . | Disease status at enrollment . | EM disease at enrollment . | Previous SCT . | Previous tisagenlecleucel . | Previous blinatumomab/inotuzumab . | Lines of treatment before CARPALL . | Disease level by flow/mol MRD before lymphodepletion . | CD19/CD22 expression at enrollment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Second relapse | No | No | Yes | Yes/yes | 6 | 0.12% 1.3 × 10−3 | +/+ |

| 2 | Second relapse | CNS | Yes | No | Yes/no | 5 | 0.39% 1 × 10−2 | +/+ |

| 3 | Third relapse | No | Yes | Yes | No/no | 6 | ND/6 × 10−2 | +/+ |

| 4 | Second relapse | CNS | Yes | No | No/no | 3 | 0.069% 7 × 10−4 | +/+ |

| 5 | Second relapse | CNS | Yes | No | No/no | 3 | Negative/negative | +/+ |

| 6 | Second relapse | No | Yes | Yes | Yes/no | 4 | 85% | +/+ |

| 7 | Second relapse | Adenopathy/pelvic mass | No | No | Yes/yes | 3 | 12% 2.8 × 10−1 | 10% Blasts CD19 neg/+ |

| 8 | First relapse | No | No | No | No/no | 2 | 2.3%/ND | Neg/+ |

| 9 | Second relapse | No | No | Yes | No/no | 4 | 18.6% | 100% Blasts CD19 neg/5% blasts CD22 neg |

| 10 | Second relapse | Chest wall | Yes | No | Yes/no | 3 | Negative/negative | +/+ |

| 11 | First relapse | CNS and spine | No | No | Yes/no | 3 | 7.4% | +/+ |

| 12 | First relapse | CNS | No | No | No/no | 2 | Negative/negative | +/+ |

+, positive; CNS, central nervous system; EM, extramedullary; mol, molecular; ND, not determined; neg, negative.

supplemental Tables 1 and 2 detail toxicities. Eleven of 12 patients developed CRS (grade 1, n = 5; grade 2, n = 6), with 5 receiving tocilizumab. No severe CRS (grade ≥3) or CRS-related intensive care unit management occurred. Cytokine profiles are in supplemental Figure 3. Grade 1 to 2 ICANS occurred in 5 patients. One developed grade 4 neurotoxicity/ICANS 6 weeks after infusion, resembling fludarabine-related leukoencephalopathy, although ICANS could not be excluded. Prolonged cytopenia was noted in 10 of 12 patients, with 1 needing a CD34+ donor stem cell infusion, but only 4 instances of grade 4 infection were seen. No toxicity-related deaths or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis were noted, unlike other CD22 CAR studies.11 This may relate to the generally mild CRS manifestations and limited cytokine disturbance found with this product. No increased toxicity from dual targeting was evident.

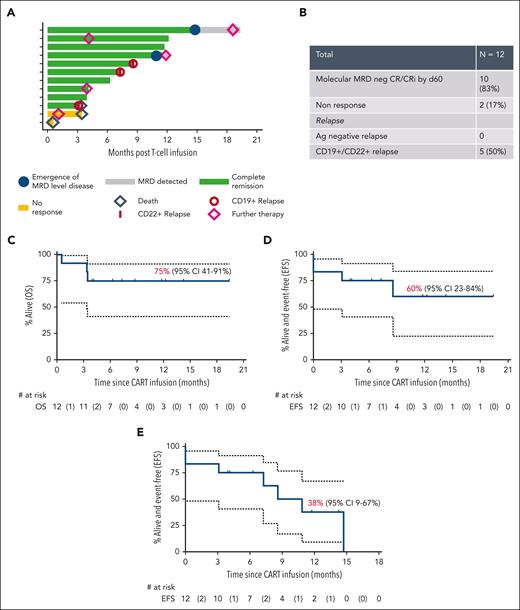

Figure 1 summarizes outcomes. One month after CAR T-cell infusion, 10 of 12 (83%) patients achieved CR/CRi (including 3 in continuing CR/CRi). By the second month, all responders were MRD negative. Two of 3 patients with prior CD19-negative disease achieved MRD-negative CR/CRi, validating CD22 CAR T-cell efficacy. Two patients failed to respond, one with CD19+/CD22+ disease and another with progression of double CD19−/CD22− disease present as a minor population before infusion. Both succumbed to disease.

Outcomes. (A) Swimmer plot representing postinfusion course for each of the enrolled patients. (B) Summary of response and relapses. Kaplan-Meier curves for 12-month OS with 12 patients at risk and 3 events (C), 12-month EFS with event being nonresponse, morphologic relapse, or death, with 12 patients at risk and 4 events (D), and 12-month “stringent EFS,” with events being nonresponse, morphologic relapse, or emergence of MRD level disease, death, and need for further therapy, with 12 patients at risk and 7 events (E). Ag, antigen.

Outcomes. (A) Swimmer plot representing postinfusion course for each of the enrolled patients. (B) Summary of response and relapses. Kaplan-Meier curves for 12-month OS with 12 patients at risk and 3 events (C), 12-month EFS with event being nonresponse, morphologic relapse, or death, with 12 patients at risk and 4 events (D), and 12-month “stringent EFS,” with events being nonresponse, morphologic relapse, or emergence of MRD level disease, death, and need for further therapy, with 12 patients at risk and 7 events (E). Ag, antigen.

Of 10 patients achieving MRD-negative CR/CRi, 3 relapsed with CD19+/CD22+ disease. In 2 cases, emerging MRD (CD19+CD22+) prompted further therapy (allo-SCT, n = 1; maintenance chemotherapy, n = 1), both achieving subsequent molecular CR. In all 5 patients with recurrent disease, this was CD19+CD22+ and associated with loss of CAR T-cell persistence in 4 of 5 cases. Two further patients received additional therapy for early CAR T-cell persistence loss (allo-SCT, n = 1; maintenance chemotherapy, n = 1) while in molecular CR (Figure 1A). Crucially, with a median follow-up of 8.7 months, there have been no cases of leukemic relapse in responding patients due to antigenic escape, although leukemic relapse without antigen modification was seen. Although it is possible this may occur with longer follow-up, it is noteworthy that in cohort 1, the longest interval to CD19-negative relapse was 7 months. This suggests dual targeting may have prevented antigen-negative relapse as this contrasts with our prior experience with CD19 CAR T cells alone, where 5 of 14 patients relapsed with CD19-negative disease within 7 months after infusion, as well as with other dual CAR studies, due to either suboptimal CD22 CAR function9,12 or poor persistence.13,14

At 8.7-month median follow-up (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.9-12.2 months), 5 of 10 responders are alive and disease free. The 6- and 12-month OS was 75% (95% CI, 41%-91%) (Figure 1C); EFS was 75% (95% CI, 41%-91%) and 60% (95% CI, 17%-84%), respectively (Figure 1D). Despite a high-risk cohort (including patients failing prior CD19 CAR therapy, those having CD19-negative disease, those with non–central nervous system extramedullary disease, and prior blinatumomab recipients, all factors associated with poor CAR T-cell outcomes),15 our study's 12-month OS and EFS were comparable to those of the ELIANA study. The 6- and 12-month stringent EFS (including further therapy for MRD emergence or further therapy for early CAR T-cell loss) were 75% (95% CI, 41%-91%) and 38% (95% CI, 9%-67%) (Figure 1E). Median remission duration in responders was 9.9 months.

Rapid CAR T-cell expansion was noted, peaking 14 days after infusion. Median time to loss of single CD19 and double CD19/CD22 CAR T cells by flow cytometry was 5 months; and for CD22 CAR T cells, it was 7 months (supplemental Figures 4 and 5). We observed balanced expansion of CD19 single positive, CD22 single positive, and double-positive CAR T-cell populations, contrasting studies where one CAR T-cell population dominated after infusion.16 Pharmacokinetics using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) (supplemental Figure 6 and supplemental Table 3) confirmed excellent cumulative CAR T-cell exposure in the first 28 days (area under the curve for 0-28 days for CD19 CAR, 9 ,492 498 copies/μg DNA; and for CD22 CAR, 2 586 767 copies/μg DNA), higher than that noted with AUTO1 CD19 CAR T cells alone.5 These data are encouraging because studies using a tandem CAR with binding sites for both CD19 and CD22 have been limited by suboptimal signaling in response to CD22.9,12 Another approach to overcome suboptimal T-cell signalling due to complex CAR design is the delivery of CAR T-cell cocktails or sequential CD19 and CD22 CAR T cells, although here there are regulatory challenges in delivering multiple CAR T-cell products. In a recent multicenter study, 192 of 225 pediatric patients achieved an MRD-negative CR. A total of 17 of 43 relapsing patients had antigen-negative relapse, and again persistence of CD22 CAR T cells was suboptimal. A total of 78 patients had consolidative SCT, potentially confounding the impact of dual targeting.17

CAR T-cell persistence is a prerequisite to assess dual targeting, and this has been a major limitation of studies to date. In our previous study with a bicistronic vector, short CAR T-cell persistence led to a high rate of CD19/CD22-positive relapses.18 Within the cohort presented here receiving AUTO1/22, CD19 CAR T cells were detectable by qPCR at last follow-up in 7 of 12 patients, and CD22 CAR T cells were detectable in 5 of 12 patients. Seven of 12 patients experienced ongoing B-cell aplasia; median duration of B-cell aplasia was not reached. The median duration of CAR T-cell persistence by qPCR in the blood (CD19 CAR T cells, 135 days; CD22 CAR T cells, 105 days) was similar to tisagenlecleucel (102 days) in ELIANA and ENSIGN studies.19 This is the first study we are aware of in which antigen-negative relapse was not observed and sufficient expansion and persistence of CAR T-cell populations occurred to allow full assessment of a dual-targeting approach.

We acknowledge a risk factor for CD19-negative relapse in patients treated with tisagenlecleucel4 includes high disease burden and that the cohort presented here generally had a low bone marrow disease burden (Table 1). However, the lack of CD19-negative relapses in this report contrasts sharply with our prior experience of our single CD19 CAR T-cell product alone (AUTO1) in patients with a similarly low disease burden, in which 5 of 6 relapses were with CD19-negative disease.

Our data suggest cotransduced CD19/CD22 targeting CAR T cells are well tolerated and highly effective in advanced ALL, including in those failing prior tisagenlecleucel therapy. While acknowledging that the small size of this study may lead to sampling bias, to date, we have observed no cases of relapse in a responding patient due to antigen modulation, suggesting that our dual CAR product may represent a promising approach to prevent this form of leukemic relapse. Ultimately, we noted shorter persistence overall with our dual CAR product compared with that noted with our CD19 CAR T product (AUTO1) alone and 5 of 10 cases of relapse or MRD emergence without antigen modulation. The median viral copy number in the dual CAR products was greater than that seen with AUTO1 (median vector copy number, 5.5 [range, 3.39-8.00] vs 4 [range, 1.2-8.0]), thus it is possible that higher per-cell CAR expression, particularly of the dual CAR population, may have contributed to activation-induced cell death or exhaustion. We are currently investigating manufacturing methods to support longer persistence to fully realize the potential of dual-targeting CAR T-cell therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Malcolm Brenner and John Moppett and Wendy Qian for providing oversight of the study as the Independent Data Monitoring Committee and the patients and families who participated in the study.

This study was funded by Autolus PLC and supported by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centres at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust and University College London. M.P. is supported by the UK National Institute of Health Research University College London Hospital Biomedical Research Centre. Lentiviral vectors were provided by Farzin Farzeneh’s group at King’s College Hospital, London which is supported by CRUK, the Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre, and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centres based at King’s Health Partners.

Authorship

Contribution: S.G. and G.L. contributed to study design, analyzed data, provided medical care, contributed to data collection for study patients, and wrote the manuscript; S.A. and E.G. performed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell persistence analysis by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and disease end point assessment by molecular PCR; R.R., K.N., C.T., and A.G. performed clinical study assays, performed manufacturing scale ups, manufactured products, and analyzed data; M.O.-E. analyzed data; B.P., A. Lal, S.K., and Y.N. wrote study documentation and provided trial management; J.Y. and E.K. designed, performed, and analyzed preclinical experimental work; D.P., J.C., L.W., K.-Y.K., C.W., and K.W. coordinated patient care and were responsible for data collection; S.G., G.L., M.B.C., K.M., A. Lazareva, J.S., V.P., J.B., A.R., and K.R. provided medical care and contributed to data collection for study patients; S.I., R.T., and C.C. provided flow cytometry assessment of disease status; K.G. provided manufacturing and clinical assay expertise; A. Lopes and A.H. contributed to study design, provided statistical analyses, and wrote the manuscript; V.P., J.B., A.R., A.V., and D.B. contributed to study design, identified study patients, and provided expertise in medical care for study patients; R.H. and R.W. were principal investigators for the study and provided medical care for study patients; M.P. led preclinical experimental work on development of the CD22 CAR; and P.J.A. led experimental work, provided medical care, analyzed data, wrote the manuscript, and was chief investigator for the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.G., M.P., and P.J.A. have patent rights for CAT19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) in targeting CD19 (patent application, World Intellectual Property Organization, WO 2016/139487 Al) and may receive royalties from Autolus PLC, which has licensed the IP and know-how from the CARPALL study. E.K. owns shares in Autolus. P.J.A. has received research funding from Bluebird Bio Inc. M.P. is a shareholder in and employee of Autolus PLC, which has licensed CAT CAR. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Persis J. Amrolia, Department of Bone Marrow Transplant, Zayed Centre for Research, Great Ormond Street Children's Hospital, 20 Guilford St, London WC1N 1DZ, United Kingdom; email: persis.amrolia@gosh.nhs.uk.

References

Author notes

∗S.G. and G.L. contributed equally to this work.

Data supporting findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Persis J. Amrolia (persis.amrolia@gosh.nhs.uk).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal