NPM1 MRD by qRT-PCR provides valuable prognostic information in patients with AML treated with venetoclax combinations.

Achievement of MRD negativity in the first 4 cycles identifies a group of patients with good outcomes.

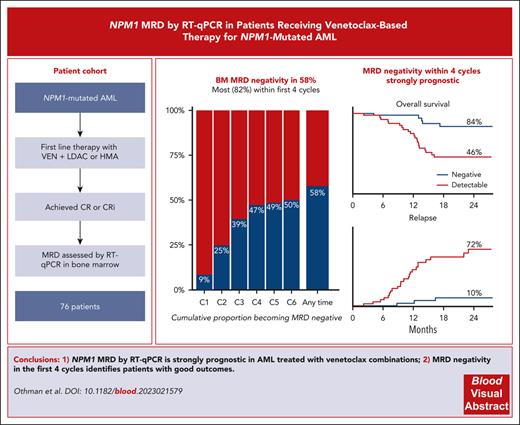

Visual Abstract

Assessment of measurable residual disease (MRD) by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction is strongly prognostic in patients with NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treated with intensive chemotherapy; however, there are no data regarding its utility in venetoclax-based nonintensive therapy, despite high efficacy in this genotype. We analyzed the prognostic impact of NPM1 MRD in an international real-world cohort of 76 previously untreated patients with NPM1-mutated AML who achieved complete remission (CR)/CR with incomplete hematological recovery following treatment with venetoclax and hypomethylating agents (HMAs) or low-dose cytarabine (LDAC). A total of 44 patients (58%) achieved bone marrow (BM) MRD negativity, and a further 14 (18%) achieved a reduction of ≥4 log10 from baseline as their best response, with no difference between HMAs and LDAC. The cumulative rates of BM MRD negativity by the end of cycles 2, 4, and 6 were 25%, 47%, and 50%, respectively. Patients achieving BM MRD negativity by the end of cycle 4 had 2-year overall of 84% compared with 46% if MRD was positive. On multivariable analyses, MRD negativity was the strongest prognostic factor. A total of 22 patients electively stopped therapy in BM MRD-negative remission after a median of 8 cycles, with 2-year treatment-free remission of 88%. In patients with NPM1-mutated AML attaining remission with venetoclax combination therapies, NPM1 MRD provides valuable prognostic information.

Introduction

Nucleophosmin (NPM1) mutations are the most common recurrent genetic abnormality in adult acute myeloid leukemia (AML). In younger patients receiving intensive chemotherapy, they generally confer a more favorable prognosis, although this is modified by FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutations and an adverse karyotype.1-5 In older or unfit patients, venetoclax combinations are particularly effective in this disease subgroup.6 The addition of venetoclax to azacitidine improved composite complete remission (CR) rate in the NPM1 mutation (mut) group from 24% to 67%,7 and in combination with low-dose cytarabine (LDAC), the rate improved from 57% to 79%.8

Molecular measurable residual disease (MRD) by mutation-specific reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) is strongly predictive of outcomes in patients with NPM1mut AML treated with intensive chemotherapy9-11; however, to date, only flow cytometric MRD has been evaluated for patients receiving venetoclax combinations.12-14 Although this was prognostic for survival, it showed less power in the small subset of patients with NPM1mut in whom a robust leukemia-associated immunophenotype is often absent.12 We, therefore, aimed to evaluate the prognostic utility of RT-qPCR in NPM1mut patients undergoing treatment with venetoclax combinations.

Study design

Patients were identified from a national real-world cohort in the United Kingdom and from patients treated in Melbourne, Australia (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website). Patients were included if they received venetoclax with either hypomethylating agents or LDAC as first-line therapy for NPM1mut AML, achieved CR or CR with incomplete hematological recovery (CRi), and had at least 1 bone marrow (BM) MRD assessment in the first 4 cycles of therapy. RT-qPCR MRD was performed at reference laboratories using validated assays and was requested at the discretion of the treating clinician; no specific monitoring schedule was recommended. Time-to-event end points were measured from the day of starting therapy, and molecular relapses were included as event-free survival (EFS) events (supplemental Methods).15

Results and discussion

A total of 76 patients were identified from 34 hospitals (Table 1). Median age was 72.1 years (range, 34-86 years), and 18 (24%) had an FLT3 ITD comutation. A median of 2.5 (range, 1-6) BM MRD assessments were performed in the first 6 cycles (supplemental Figure 2). There were no differences in baseline characteristics, depth of response, or outcomes for patients treated with LDAC or hypomethylating agents; therefore, these groups were combined for subsequent analyses (supplemental Table 1).The best BM MRD response at any time during venetoclax therapy was MRD negative in 44 (58%), positive with ≥4 log10 reduction from baseline in 14 (18%), and positive with <4 log10 reduction in 18 (24%). MRD response deepened with successive cycles (supplemental Figure 3). The cumulative rates of MRD negativity by the end of cycles 2, 4, and 6 were 25%, 47%, and 50%, respectively (Figure 1A). In those reaching MRD negativity, the median time to first negative result was 111.5 days (interquartile range, 76.75-154 days), with 8 of 44 MRD-negative patients (18%) requiring >4 cycles to achieve an MRD-negative state (range, 5-11 cycles).

Patient demographics

| Characteristic . | Values for patients (N = 76) . |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, median (range), y | 72.1 (34-86) |

| Female sex | 38 (51) |

| Performance status | |

| 0-1 | 53 (84) |

| ≥2 | 9 (16) |

| Missing | 13 |

| Disease category | |

| De novo | 59 (78) |

| Secondary | 9 (12) |

| Therapy related | 8 (11) |

| Cytogenetics | |

| Normal | 61 (80) |

| Other intermediate | 9 (12) |

| Adverse | 2 (2.6) |

| Failed | 4 (5.3) |

| FLT3 ITD | 18 (24) |

| FLT3 TKD | 11 (14) |

| DNMT3A mutation∗ | 19 (31) |

| IDH1 mutation∗ | 6 (9.8) |

| IDH2 mutation∗ | 12 (20) |

| KRAS or NRAS mutation∗ | 7 (11) |

| TP53 mutation∗ | 2 (3.3) |

| Therapy | |

| Azacitidine | 47 (62) |

| Decitabine | 2 (2.6) |

| Low-dose cytarabine | 27 (36) |

| Best morphologic response | |

| CR | 72 (95) |

| CRi | 4 (5.3) |

| Allogeneic transplant | |

| In first CR | 4 (5.3) |

| After relapse | 5 (6.6) |

| No transplant | 67 (88) |

| Characteristic . | Values for patients (N = 76) . |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, median (range), y | 72.1 (34-86) |

| Female sex | 38 (51) |

| Performance status | |

| 0-1 | 53 (84) |

| ≥2 | 9 (16) |

| Missing | 13 |

| Disease category | |

| De novo | 59 (78) |

| Secondary | 9 (12) |

| Therapy related | 8 (11) |

| Cytogenetics | |

| Normal | 61 (80) |

| Other intermediate | 9 (12) |

| Adverse | 2 (2.6) |

| Failed | 4 (5.3) |

| FLT3 ITD | 18 (24) |

| FLT3 TKD | 11 (14) |

| DNMT3A mutation∗ | 19 (31) |

| IDH1 mutation∗ | 6 (9.8) |

| IDH2 mutation∗ | 12 (20) |

| KRAS or NRAS mutation∗ | 7 (11) |

| TP53 mutation∗ | 2 (3.3) |

| Therapy | |

| Azacitidine | 47 (62) |

| Decitabine | 2 (2.6) |

| Low-dose cytarabine | 27 (36) |

| Best morphologic response | |

| CR | 72 (95) |

| CRi | 4 (5.3) |

| Allogeneic transplant | |

| In first CR | 4 (5.3) |

| After relapse | 5 (6.6) |

| No transplant | 67 (88) |

ITD, internal tandem duplication; TKD, tyrosine kinase domain.

Data are given as number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

Next-generation sequencing results available in 61 patients.

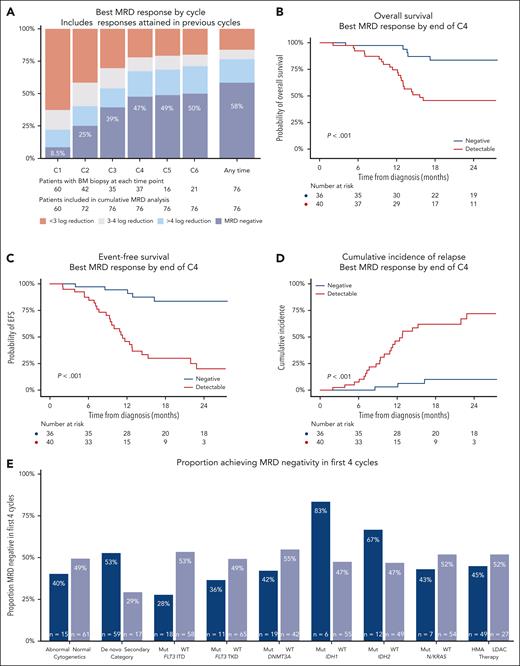

MRD responses and outcomes in patients with NPM1 mutated AML achieving CR/CRi with venetoclax-based therapies. (A) Best MRD response by the end of cycles 1 to 6, and overall. (B) Overall survival by achievement of MRD negativity in first 4 cycles. (C) EFS by achievement of MRD negativity in first 4 cycles. (D) Cumulative incidence of relapse by achievement of MRD negativity in first 4 cycles. (E) Rates of MRD negativity in the first 4 cycles in patient subgroups. C1, cycle 1; C2, cycle 2; C3, cycle 3; C4, cycle 4; C5, cycle 5; C6, cycle 6; ITD, internal tandem duplication; Mut, mutated; TKD, tyrosine kinase domain; WT, wild type.

MRD responses and outcomes in patients with NPM1 mutated AML achieving CR/CRi with venetoclax-based therapies. (A) Best MRD response by the end of cycles 1 to 6, and overall. (B) Overall survival by achievement of MRD negativity in first 4 cycles. (C) EFS by achievement of MRD negativity in first 4 cycles. (D) Cumulative incidence of relapse by achievement of MRD negativity in first 4 cycles. (E) Rates of MRD negativity in the first 4 cycles in patient subgroups. C1, cycle 1; C2, cycle 2; C3, cycle 3; C4, cycle 4; C5, cycle 5; C6, cycle 6; ITD, internal tandem duplication; Mut, mutated; TKD, tyrosine kinase domain; WT, wild type.

Median follow-up was 28 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 24-31 months), with 2-year overall survival (OS) of 63% (95% CI, 53%-76%) and 2-year EFS of 52% (95% CI, 40%-66%). The deepest BM MRD reduction achieved at any time during venetoclax therapy was strongly associated with survival: 2-year OS was 84% (95% CI, 74%-97%) in those with undetectable MRD, 50% (95% CI, 30%-84%) if detectable but ≥4 log10 reduction from baseline, and 22% (95% CI, 11%-57%) if <4 log10 reduction (supplemental Figure 4). Cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR) was high in those with poor MRD responses. Of the relapses that occurred in patients who achieved MRD negativity, 5 of the 6 patients had FLT3 ITD (50%) and/or secondary disease (50%). There was no survival difference between patients who achieved MRD negativity within the first 4 cycles or later (supplemental Figure 5), despite some differences in their baseline characteristics (supplemental Table 2).

Using the lowest NPM1 copy number achieved in BM by the end of cycles 2 and 4, we employed maximally selected rank statistics to identify a predictive and clinically useful early MRD threshold (supplemental Table 3).16 On the basis of these results, and considering the high coefficient of variation in copy number calculation between laboratories,17 we selected a cutoff of 0 NPM1 copies per 100 ABL1 (ie, MRD negative) by the end of cycle 4 as the optimal threshold. This threshold provided a sensitivity of 85%, a specificity of 85%, and an area under the curve of 0.84 for 24-month EFS by receiver-operator characteristic curve analyses. Patients remaining MRD positive in the BM in the first 4 cycles had 2-year OS of 46%, EFS of 20%, and CIR of 72%, whereas in those achieving MRD negativity, 2-year OS and EFS values were 84% and CIR was 10% (Figure 1B-D).

Patients with IDH1 and IDH2 comutations had a high rate of early NPM1 BM MRD negativity (83% and 67%, respectively), whereas this was lower in those with secondary AML (29%) and FLT3 mutations (FLT3 ITD, 28%; and FLT3 TKD [tyrosine kinase domain], 36%; Figure 1E). Multivariable analyses showed achievement of MRD negativity in 4 cycles (as a time-dependent variable) to be the most important factor associated with survival, with a hazard ratio of 0.21 (95% CI, 0.08-0.55; P = .002; supplemental Table 4). The MRD threshold at cycle 2 (<0.002 copies per 100 ABL1) was also associated with outcomes but did not discriminate as well as the cycle 4 threshold (supplemental Figure 6).

A total of 39 patients also had at least 1 peripheral blood (PB) MRD sample for analysis, with 28 (72%) achieving MRD negativity in the first 4 cycles. Patients with detectable PB MRD had poor outcomes (2-year OS, 32%; EFS, 18%; CIR, 82%; supplemental Figure 7). PB was less sensitive than BM (supplemental Figure 8), and the 6 patients who achieved MRD negativity in the PB but not BM had worse EFS than those negative in both sample sources (supplemental Figure 9).

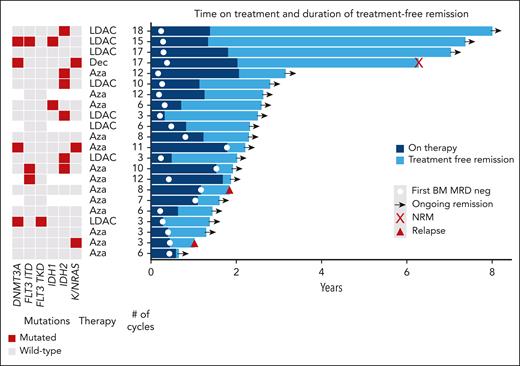

A total of 22 patients who achieved BM MRD negativity and did not proceed to allogeneic transplant electively stopped therapy (4 patients previously described18), due to patient choice or physician recommendation, after a median of 8 cycles (range, 3-18 cycles). Regular BM MRD monitoring for relapse was recommended. With median follow-up from stopping of 15 months, only 2 relapses (1 molecular and 1 hematological) and 1 nonrelapse mortality have occurred, with 2-year treatment-free remission of 88% (Figure 2).

Swimmer plot of outcomes in patients electively stopping therapy in MRD-negative (neg) remission. Aza, azacitidine; Dec, decitabine; LDAC, low-dose cytarabine; NRM, non-relapse mortality.

Swimmer plot of outcomes in patients electively stopping therapy in MRD-negative (neg) remission. Aza, azacitidine; Dec, decitabine; LDAC, low-dose cytarabine; NRM, non-relapse mortality.

In this cohort of 76 patients with NPM1mut AML achieving CR/CRi with venetoclax combinations, MRD by RT-qPCR was strongly associated with clinical outcomes. Achievement of NPM1 MRD negativity in the BM within the first 4 cycles of therapy identified patients with excellent survival, independent of pretreatment variables.

The prognostic importance of NPM1 RT-qPCR in patients treated with intensive chemotherapy is well established, including at early time points,9,10 end of therapy,19 and before transplant.20,21 Comprehensive guidelines have been published, outlining methods, time points, and monitoring.22 It has not previously been demonstrated that deeper remissions, as measured by RT-qPCR, have prognostic importance when patients are treated with less intensive, continuous therapies, such as venetoclax combinations. Here, we show that venetoclax combinations are able to induce deep remissions, including MRD negativity, in 58%, and that the depth of response clearly predicts outcomes. In those with CR/CRi but persistence of MRD, relapses are frequent and occur early, including while receiving therapy.

Venetoclax combinations are currently administered as indefinite therapy, and long-term follow-up has not demonstrated a survival plateau to suggest that patients may be cured.23 However, it has been shown that MRD-negative patients with NPM1 or IDH2 mutations can have prolonged treatment-free remissions.18 The promising results in our cohort in those achieving MRD negativity, with 2-year OS of 84%, raises the possibility that the disease may be eradicated in some. Our outcomes after stopping therapy, including 4 patients with >4 years treatment-free remission, support this hypothesis, although follow-up is relatively short for most patients. With a growing body of literature on the promising outcomes achieved when treating patients at the molecular relapse stage,24,25 patients who elect to stop therapy should continue to be monitored by MRD to detect relapses early. Prospective trials examining MRD-directed treatment deintensification or cessation are warranted. Patients not achieving MRD negativity in our cohort had poor outcomes, and future studies should investigate whether treatment changes, such as increasing treatment intensity or adding or switching to other targeted or investigational therapies, can improve their survival.

Our study has several limitations, in particular its retrospective nature, introducing potential selection bias, which we attempted to address by identifying and including all eligible patients at each center. The timing of MRD measurements was heterogeneous, with not all patients having a BM biopsy after each cycle. Finally, the therapies administered were not uniform, in terms of both the venetoclax schedules and chemotherapy backbone. Despite these limitations, our data demonstrate the RT-qPCR MRD can add important prognostic information to the treatment of NPM1 AML with venetoclax combinations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the clinicians and nurse specialists involved in the care of the patients. J.O. thanks Harry Iland for mentorship and supervision.

J.O. was supported by fellowship grants from the Haematology Society of Australia and New Zealand and the RCPA Foundation, R. Dillon receives laboratory funding from Blood Cancer UK, Cancer Research UK, and the National Institute for Health Research. P.G. was supported by Cancer Research UK Advanced Clinician Scientist fellowship, C57799/A27964.

Authorship

Contribution: J.O., A.H.W., and R. Dillon conceptualized the study; all authors enrolled patients; all authors collected data; J.O. performed data analysis; K.M., N.P., A.I., I.S.T., and J.O. performed measurable residual disease analyses; J.O. and R. Dillon drafted the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: I.S.T. declares consultancy from Pfizer and Servier; and speaker’s bureau with Amgen, Pfizer, and Servier. A.-L.L. declares honoraria from Astella, AbbVie, Amgen, Kite, Novartis, Jazz, and Daiichi Sankyo; and speaker’s bureau with Kite, Takeda. and Astellas. C.Y.F. declares consultancy and honoraria from AbbVie, Astellas, BeiGene, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Pfizer, Jazz, Otsuka, Amgen, and Novartis; speaker’s bureau with AbbVie and Pfizer; and research funding from Astellas. R. Dang declares meeting sponsorship from Jazz; and honoraria from AbbVie. R. Dillon declares research funding from AbbVie and Amgen; and consultancy with Astellas, Pfizer, Novartis, Jazz, Beigene, Shattuck, and AvenCell. P.G. declares honoraria from Astellas. F.H. declares meeting sponsorship and honoraria from AbbVie. A.K. declares honoraria from AbbVie, Novartis, Gilead, and Takeda; speaker’s bureau with Astellas and Jazz; and advisory board for TC BioPharm, Novartis, Jazz, and Takeda. P. Krishnamurthy declares honoraria from Jazz, Astellas, and Gilead; speaker’s bureau with Astellas; and consultancy for Jazz and Gilead. V.M. declares consultancy and honoraria from AbbVie. S.M. declares consultancy and advisory board with AbbVie. P.M. declares speaker’s fees and advisory board with Pfizer, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, and AbbVie. S.N. declares consultancy and speaker’s fees from SOBI, Alexion, Novartis, and Amgen. N.H.R. declares research funding from Jazz and Pfizer; and honoraria from Pfizer, Servier, and Astellas. A.H.W. has served on advisory boards for Novartis, Astra Zeneca, Astellas, Janssen, Jazz, Amgen, Roche, Pfizer, AbbVie, Servier, BMS, Beigene, and Gilead; consulted for AbbVie, Servier, Novartis, Shoreline, and Aculeus; receives research funding to the institution from Novartis, AbbVie, Servier, BMS, Syndax, Astex, AstraZeneca, and Amgen; and serves on speaker bureaus for AbbVie, Novartis, BMS, Servier, and Astellas. A.H.W. is an employee of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute (WEHI). WEHI receives milestone and royalty payments related to the development of venetoclax. Current and past employees of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute may be eligible for financial benefits related to these payments. A.H.W. receives such a financial benefit. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Richard Dillon, Department of Medical and Molecular Genetics, Kings College London, Floor 8 Tower Wing, Guy’s Hospital, London SE1 9RT, United Kingdom; email: richard.dillon@kcl.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

Access to deidentified data is available via application to the corresponding author.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal