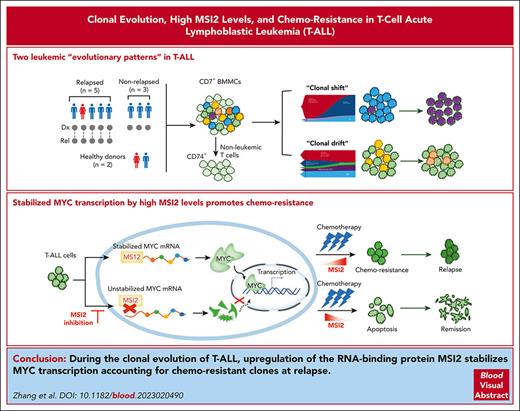

Two leukemic evolutionary patterns, “clonal shift” and “clonal drift” are unveiled in relapsed T-ALL via single-cell multiomics profiling.

High RNA-binding protein MSI2 level accounts for persistent clones at relapse through the posttranscriptional regulation of MYC in T-ALL.

Visual Abstract

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) is an aggressive cancer with resistant clonal propagation in recurrence. We performed high-throughput droplet-based 5′ single-cell RNA with paired T-cell receptor (TCR) sequencing of paired diagnosis–relapse (Dx_Rel) T-ALL samples to dissect the clonal diversities. Two leukemic evolutionary patterns, “clonal shift” and “clonal drift” were unveiled. Targeted single-cell DNA sequencing of paired Dx_Rel T-ALL samples further corroborated the existence of the 2 contrasting clonal evolution patterns, revealing that dynamic transcriptional variation might cause the mutationally static clones to evolve chemotherapy resistance. Analysis of commonly enriched drifted gene signatures showed expression of the RNA-binding protein MSI2 was significantly upregulated in the persistent TCR clonotypes at relapse. Integrated in vitro and in vivo functional studies suggested that MSI2 contributed to the proliferation of T-ALL and promoted chemotherapy resistance through the posttranscriptional regulation of MYC, pinpointing MSI2 as an informative biomarker and novel therapeutic target in T-ALL.

Introduction

Occurrences of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) arise in ∼10% to 15% of pediatric ALL cases.1,2 Historically, the outcomes for patients with T-ALL are inferior to those for patients with B-cell ALL, largely driven by distinct differences in biology, such as a lack of favorable genetic subtypes, the presence of high-risk clinical features, and the increased probability of extramedullary disease with T-ALL.3-7 Recently, quite a few systemic studies8-15 have attempted to delineate therapeutically targetable molecular events that drive relapse in T-ALL subtypes and have become an area of interest.

Hematological malignancy is clearly an outcome of the Darwinian evolutionary principle, as random genetic variation emerged during the evolution from a common descendant, together with variants from natural selection of the fittest.16-18 Previous work has relied on clonal architecture inferences using bulk sequencing analysis,19 in which the complexity and heterogeneity within and across samples are likely to be masked. The exploitation of single-cell sequencing techniques has shifted leukemic research toward a new paradigm, allowing for a more precise characterization of clonal evolutionary patterns. Recent work on acute myeloid leukemia (AML),20,21 ALL,22,23 and other hematological malignancies24 has led to the consecutive reporting of evolutionary phylogeny and associations with treatment resistance in longitudinal settings at single-cell DNA (scDNA) levels. Similar endeavors have been carried out to longitudinally trace clonal-specific phenotypes correlated with genotype by proteogenomic analysis.24,25

Recently, the techniques of high-dimension and high-resolution single-cell transcriptomic sequencing of functional T cells in solid tumors have been used to gradually attain insights into the relationships between cancer evolution/metastasis and the dynamics of tumor-infiltrating immune cells.26-28 Similar revelations were attained for AML29 and B-cell ALL30 after leukemic-associated monocytes with both immunomodulatory and prognostic significance were revealed. Nevertheless, the architecture of the immunomodulatory milieu and its supportive role in leukemic propagation during chemotherapy for T-ALL have yet to be clarified.

Hence, we innovatively used single-cell transcriptomic sequencing, single-cell T-cell receptor (scTCR) sequencing and scDNA sequencing (scDNA-seq) with the Tapestri platform to delineate the signatures of T-ALL heterogeneity and clonality and nonleukemic T cells in paired diagnosis–relapse (Dx_Rel) T-ALL samples. This multidimensional approach at the single-cell resolution allowed us to study the order of acquisition and cooccurrence of subclonal alterations, to dissect the origins of leukemic relapse, as well as its mechanistic driving force, and therefore to achieve insights into putative therapeutic targets in T-ALL within clonal progression complexity.

Methods

Sample collection

All 5 pediatric patients with T-ALL or their legal guardians had provided written informed consent for access to banked samples for basic studies with strict ethical guidelines. These patients with T-ALL with paired Dx_Rel bone marrow (BM) samples were initially enrolled in the unified multicentered regimen CCCG-ALL-2015, as previously described.31 For pediatric healthy donors (HDs), BM samples were collected from donors undergoing unrelated or sibling-matched BM transplantation. The consent process for these donors involved providing detailed information to the parents or legal guardians about the purpose of the BM collection and a comprehensive explanation of the purpose of banking cells for basic studies, as well as the protection of the donor's anonymity and confidentiality. The detailed clinical information is depicted in supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website. Protocols covering all study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the Institute of Hematology, Blood Diseases Hospital, Peking Union Medical College/Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (approval no.: 2018H021).

Results

Discrimination of leukemic cells in T-ALL

Following the designed multiomics profiling strategy of T-ALL at the leukemia diagnosis and reoccurrence stages (Figure 1A), bulk whole-exome sequencing of BM mononuclear cells (BMMCs) from 5 Dx_Rel-paired T-ALL samples (supplemental Table 1; “Methods”) confirmed the presence of mutational hot spots in our cohort, which corresponded to the most frequently reported driver mutations in T-ALL, including mutations of PTEN (6 of 10 samples), FBXW7 (6 of 10), NOTCH1 (4 of 10), EZH2 (4 of 10), and NRAS (2 of 10). Notably, 5 variations (PTENR23C2fs, PTENN262Qfs, FBXW7R465C, EZH2D730∗, and KDM6AR1111C) were diagnosis specific and absent at relapse; whereas 4 other variations (PTENF241_E242insV, PTENF241delinsFV, FBXW7R505C, and NT5C2R367Q) emerged exclusively at relapse, highlighting the putative correlations between the mutational profiles and chemotherapy resistance under therapeutic pressure. With bulk transcriptomic analyses incorporated to enrich the driven node for these 5 patients, 3 patients (T856, T956, and T723) were characterized as having TAL1-driven subtype, and 1 patient (T593) as having HOXA-driven subtype, and it was concluded that the patient with early T-cell precursor (ETP)-ALL (T788) had LMO2-LYL1 subtype (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 1; supplemental Table 2).

Bulk and single-cell multiomics analyses of 5 diagnosis–relapse T-ALL pairs. (A) Schematic workflow of bulk whole-exome sequencing, single-cell transcriptomic analysis (5′ scRNA-seq) with paired single-cell TCR genotyping (scTCR-seq), and scDNA-seq of CD7+ BMMCs from 5 Dx_Rel paired T-ALL samples and samples from 2 HDs. (B) Oncoprint pairwise analysis of somatic variances in leukemia cells from samples from 5 patients (T956, T723, T593, T856, and T788) at diagnosis (Dx) and relapse (Rel) by whole-exome sequencing. Detailed mutational information is shown in supplemental Table 2. (C) UMAP plot showing 9 distinct T-lineage clusters (demarcated by color) based on the gene-expression profiles of isolated CD7+ BMMCs in Dx_Rel paired samples from 5 patients. (D) UMAP plots displaying distinct identities of each Dx (first row) and the corresponding Rel sample (second row) based on the sample signatures overlaid in panel C. (E) UMAP plot showing cell points colored according to TCR clonality in CD7+ BMMCs from the 5 Dx_Rel pairs. The color of each cell point indicates clonal abundance, and the gray color indicates a lack of TCR. (F) Dot plot showing the top significantly differently expressed genes (adjusted P < .05, average log2 fold change [FC] > 0) of each cluster obtained by FindAllMarkers. Gene-expression frequency (percentage of cells within each cell type expressing the gene) is indicated by spot size, and expression level is indicated by color intensity. (G) Violin plot depicting expression levels of featured gene, CD74, in cluster 9 (blue) and cluster 12 (cyan). (H-I) Sanger sequencing validation of FBXW7 mutation status of CD7+CD74+ normal T cells and CD7+CD74− leukemic cells from patients T956 (F) and T723 (G) individually sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Bulk and single-cell multiomics analyses of 5 diagnosis–relapse T-ALL pairs. (A) Schematic workflow of bulk whole-exome sequencing, single-cell transcriptomic analysis (5′ scRNA-seq) with paired single-cell TCR genotyping (scTCR-seq), and scDNA-seq of CD7+ BMMCs from 5 Dx_Rel paired T-ALL samples and samples from 2 HDs. (B) Oncoprint pairwise analysis of somatic variances in leukemia cells from samples from 5 patients (T956, T723, T593, T856, and T788) at diagnosis (Dx) and relapse (Rel) by whole-exome sequencing. Detailed mutational information is shown in supplemental Table 2. (C) UMAP plot showing 9 distinct T-lineage clusters (demarcated by color) based on the gene-expression profiles of isolated CD7+ BMMCs in Dx_Rel paired samples from 5 patients. (D) UMAP plots displaying distinct identities of each Dx (first row) and the corresponding Rel sample (second row) based on the sample signatures overlaid in panel C. (E) UMAP plot showing cell points colored according to TCR clonality in CD7+ BMMCs from the 5 Dx_Rel pairs. The color of each cell point indicates clonal abundance, and the gray color indicates a lack of TCR. (F) Dot plot showing the top significantly differently expressed genes (adjusted P < .05, average log2 fold change [FC] > 0) of each cluster obtained by FindAllMarkers. Gene-expression frequency (percentage of cells within each cell type expressing the gene) is indicated by spot size, and expression level is indicated by color intensity. (G) Violin plot depicting expression levels of featured gene, CD74, in cluster 9 (blue) and cluster 12 (cyan). (H-I) Sanger sequencing validation of FBXW7 mutation status of CD7+CD74+ normal T cells and CD7+CD74− leukemic cells from patients T956 (F) and T723 (G) individually sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Next, we carried out high-throughput droplet-based 5′ single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) and paired scTCR sequencing (“Methods”) of isolated CD7+ BMMCs from 5 patients’ Dx_Rel-paired samples (Figure 1A). After unsupervised clustering of scRNA-seq profiles for 109 379 CD7+ cells (98 906 cells passed quality control; supplemental Table 3) derived from 10 samples, we identified 23 distinct T-lineage clusters (clusters 0-22) based on the 2-dimensional uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) visualization of expression signatures (Figure 1C). We used the same strategy to manually compare the composition density of the pairwise UMAP projections for each patient, and a notable diversity of subpopulation distribution patterns was observed (Figure 1D). To examine the variations between the diagnosed and relapsed samples in reference to the normal T-developmental landscape, we created a roadmap of childhood T-lineage development in the BM using scRNA-seq data from CD34+ BMMCs of 3 HDs and CD3+ BMMCs of 2 HDs (supplemental Figure 2A-D). By projecting scRNA-seq data from 5 Dx_Rel paired T-ALL cells onto the normal T-cell atlas, we detected similarly distributed differentiational states, with distinct transcriptomic signatures among the 5 patients, whereas the dynamics in proportions appeared heterogeneous across patients (supplemental Figure 2F-G). We saw clear stage ratio alterations from diagnosis to relapse in patients T956 and T723, whereas differentiation stage ratios in patients T593, T856, and T788 remained relatively constant throughout disease courses (supplemental Figure 2H).

It is worth noting that 2 T-cell subclusters (clusters 9 and 12) were preserved in both the diagnostic and relapse diffusions of T-cell subclusters across the 5 Dx_Rel pairs. We then integrated scTCR-seq and scRNA-seq analysis by manually curating and overlaying the UMAP with the TCR clonal abundances for the 5 Dx_Rel T-ALL pairs (T956, T723, T856, T593, and T788) and correlated the clonal TCR rearrangements with signature-based clonality across the Dx_Rel pairs (Figure 1E). Intriguingly, the aforementioned clusters 9 and 12 existed regardless of disease stage across patient samples, and were associated with negligible TCR clonal signatures, which indicated these 2 clusters might comprise nonleukemic T cells. Given the upregulated transcriptomic signature of surface marker CD74 and low copy number variation specifically in clusters 9 and 12 (Figure 1F-G; supplemental Figure 3A-B), we further confirmed the nonleukemic phenotypes of clusters 9 and 12 by validating the lack of leukemic driver mutations (FBXW7R465C in T956, and FBXW7R465H in T723) by Sanger sequencing of the sorted CD7+CD74+ cells compared with the corresponding CD7+CD74− subpopulations (Figure 1H-I). Furthermore, differential expression analysis enriched multiple cytotoxicity-associated transcripts (GZMB, GZMA, PRF1, CCL4, and CCL5) for clusters 9 and 12, indicating potential immune-associated T-cell activation (Figure 1F). To highlight nonleukemic T cells in patients with T-ALL at diagnosis, we included scRNA-seq and scTCR-seq data of CD7+ BMMCs from another 3 patients with nonrelapsed T-ALL at diagnosis. In line with the above findings, we confirmed the presence of the nonleukemic T cells (cluster 9, 11, 13, and 15) with featured CD74, GZMB, and CCL4 expressions and deficient TCR clonalities in all 3 patients with nonrelapsed T-ALL (supplemental Figure 4A-D).

The transcriptomic signatures of patient T788, with a diagnosis of ETP ALL, showed unaltered clonal architecture with a paucity of clonal TCRs throughout chemotherapy (supplemental Figure 5A-E), implying that putative leukemic differentiation was arrested at the earlier progenitor stages before TCR rearrangement was completed. In addition, we found conserved nonclonal T-cell subclusters in patient T788 that were identical to those of the other 4 patients, such as CCL5, CD74, and GZMM (supplemental Figure 5F). The gene signatures of both Dx_Rel samples from patient T788 revealed the upregulation of CSF3R, SPI1, NOTCH2, and ETS2, indicative of the stem cell and myeloid signatures in this subtype (supplemental Figure 5G).

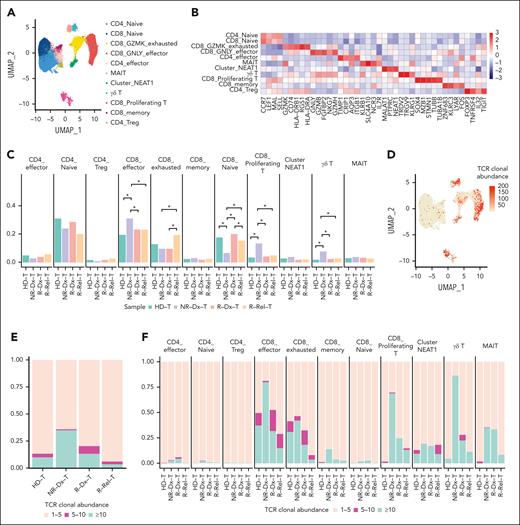

Transcriptomic signatures of nonleukemic T cells

Next, we sought to comprehend the behavior of the nonleukemic T-cell subclusters, as well as its potential association with T-ALL progression. We sequenced 18 562 nonleukemic T cells (14 259 single cells passed quality control; supplemental Table 3) from CD3+ BMMCs of 2 pediatric HDs using the well-described nature of our model via scRNA-seq with paired scTCR-seq. With 11 functional T-cell subclusters categorized from 22 initial subclusters by specific gene signatures in corresponding subcluster (Figure 2A-B; supplemental Figure 6A-B; supplemental Table 4), we manually projected nonleukemic T-cell subclusters from the 5 patients with relapsed T-ALL at diagnosis (R-Dx-T) or at relapse (R-Rel-T; cluster 9 and 12, as annotated in Figure 1C), and the 3 patients with nonrelapsed T-ALL at diagnosis (cluster 9, 11, 13, and 15, as annotated in supplemental Figure 4A), onto the well-defined subclusters for integrative analysis. Notably, pairwise comparisons among subclusters across HDs and each patient subtype revealed that the proportions of effector CD8 T cells, proliferative CD8 T cells, and γδ T cells in patients with nonrelapsed T-ALL, at diagnosis (NR-Dx-T) were significantly higher than those in R-Dx-T, whereas CD8+GZMK+-exhausted T cells were dramatically increased at relapse (R-Rel-T), compared with those at diagnosis (NR-Dx-T and R-Dx-T) and those from HDs (Figure 2C). Intriguingly, integrated analysis in TCR clonality across these subtypes revealed that the overall proportion of clonal TCR was evidently increased in NR-Dx-T, indicative of potential activation in leukemic-infiltrating T lymphocytes (Figure 2E).

Single-cell characteristics of leukemia-infiltrating nonleukemic T lymphocytes in T-ALL. (A) UMAP plot showing 11 distinct clusters of nonleukemic T cells combining CD7+ BMMCs from 5 relapsed T-ALL patients at diagnosis (R-Dx-T) or relapse (R-Rel-T), 3 patients with nonrelapsed T-ALL, at diagnosis (NR-Dx-T), and CD3+ BMMCs from 2 HDs (HD-T). (B) Heat map hierarchically displays top 5 gene signatures featuring each of the 11 subclusters of nonleukemic T cells in panel A. (C) Bar plot comparing the proportion of each subcluster across 4 groups: R-Dx-T, R-Rel-T, NR-Dx-T, and HD-T. Wilcoxon rank sum test is used for statistical analysis; ∗P < .05. (D) UMAP plot of nonleukemic T-cell identities colored according to TCR clonal abundance of the 15 T-ALL samples and HDs. The gray color indicates a lack of TCR. (E-F) Stacked bar plots depicting frequency of the 3 TCR clonality categories across the 4 groups: R-Dx-T, R-Rel-T, NR-Dx-T, and HD-T for all the nonleukemic T cells (E), and for each of the 11 functional T subclusters, respectively (F). The 3 TCR clonal expansion groups were denoted with colors: in which category “>10” in blue indicates that there were at least 10 cells that express the identical TCR clonotype; category “5-10” in purple indicating that 5 to 10 T cells express an identical TCR clonotype; and category “1-5” in salmon indicates that only 1 to 5 cells express a specific TCR clonotype. (G-H) Heat maps hierarchically display the top 20 group-specific genes and pathways that are enriched in CD8_GNLY_effector T subcluster (G) or CD8_GZMK_exhausted T subcluster (H) across the 4 patient groups (R-Dx-T, R-Rel-T, NR-Dx-T, and HD-T) by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). FDR, false discovery rate.

Single-cell characteristics of leukemia-infiltrating nonleukemic T lymphocytes in T-ALL. (A) UMAP plot showing 11 distinct clusters of nonleukemic T cells combining CD7+ BMMCs from 5 relapsed T-ALL patients at diagnosis (R-Dx-T) or relapse (R-Rel-T), 3 patients with nonrelapsed T-ALL, at diagnosis (NR-Dx-T), and CD3+ BMMCs from 2 HDs (HD-T). (B) Heat map hierarchically displays top 5 gene signatures featuring each of the 11 subclusters of nonleukemic T cells in panel A. (C) Bar plot comparing the proportion of each subcluster across 4 groups: R-Dx-T, R-Rel-T, NR-Dx-T, and HD-T. Wilcoxon rank sum test is used for statistical analysis; ∗P < .05. (D) UMAP plot of nonleukemic T-cell identities colored according to TCR clonal abundance of the 15 T-ALL samples and HDs. The gray color indicates a lack of TCR. (E-F) Stacked bar plots depicting frequency of the 3 TCR clonality categories across the 4 groups: R-Dx-T, R-Rel-T, NR-Dx-T, and HD-T for all the nonleukemic T cells (E), and for each of the 11 functional T subclusters, respectively (F). The 3 TCR clonal expansion groups were denoted with colors: in which category “>10” in blue indicates that there were at least 10 cells that express the identical TCR clonotype; category “5-10” in purple indicating that 5 to 10 T cells express an identical TCR clonotype; and category “1-5” in salmon indicates that only 1 to 5 cells express a specific TCR clonotype. (G-H) Heat maps hierarchically display the top 20 group-specific genes and pathways that are enriched in CD8_GNLY_effector T subcluster (G) or CD8_GZMK_exhausted T subcluster (H) across the 4 patient groups (R-Dx-T, R-Rel-T, NR-Dx-T, and HD-T) by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). FDR, false discovery rate.

Further assessment of TCR clonalities for each T subclusters revealed that CD8+GNLY+ effector T cells, CD8+ proliferative T cells, and γδ T cells were the subclusters with most prominent enrichment of clonal TCR, particularly in nonrelapsed T-ALL at diagnosis (NR-Dx-T, Figure 2F). Differential expression and Gene Ontology functional analysis further characterized the potentially activated NR-Dx-T subtypes with consistent T-cell signaling activation (CD8+GNLY+ and CD8+GZMK+ effector T cells; Figure 2G-H; supplemental Tables 5 and 6) and possibly activated immune response (CD8+ proliferative and γδ T cells,; supplemental Figure 6C-D; supplemental Tables 7 and 8). Although statistical significance is currently unattainable because of the overall low abundance of TCR clonality in nonleukemic T cells and the heterogeneity across individuals in our cohort, this preliminary observation raised the possibility of a link between activated antitumor immune response and effectiveness in preserving leukemic-free remission, and warranted further functional investigations.

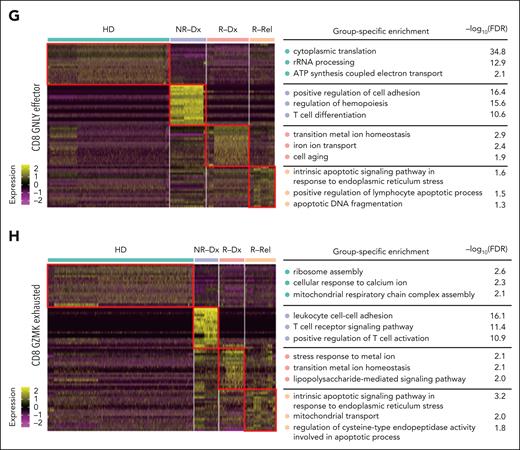

Contrasting clonal evolution trajectories in T-ALL

To further investigate the gene signature variation underlying leukemic progression, we embedded the unsupervised inference of subclusters according to the gene signatures associated with the TCR-inferred clonality for each patient with non-ETP ALL. As expected, the dominant diagnostic subclusters of the 4 patients diminished (T593) or vanished (T956, T723, and T856), whereas subclusters with emergent signatures dominated at relapse (Figure 3A-D), which was indicative of the heterogeneity across these 4 patients in the variability of their dynamic gene signatures from diagnosis to relapse. Next, we inferred the most probable clonal progression traits by mapping the TCR clonotypes onto the gene signature subclusters at both time points (Figure 3E-H; supplemental Table 9). We observed that the properties of TCR clonality evolved from diagnosis to relapse, which affected the expression patterns in patients T723 and T956 accordingly from diagnosis to relapse (Figure 3A-B,E-F). By contrast, the dominant TCR clones in patients T593 and T856 seemed identical across diagnostic and corresponding relapsed samples but were intriguingly depicted with different gene signatures (Figure 3C-D,G-H). Therefore, 2 distinct patterns of evolutionary trajectories were present in the 4 Dx_Rel pairs. Focusing in on Dx_Rel pairs from patients T956 and T723, we observed a significant outgrowth in initially negligible diagnostic subclusters at relapse (Figure 3A-B), to which surrogate TCR repertoires were correspondingly linked and enumerated. These changes were suggestive of the presence of robust dominant “clonal shifts” under continuous pressure from chemotherapy (Figure 3E-F). Whereas strikingly, Dx_Rel pairs from patients T593 and T856 (Figure 3C-D), which contained subclusters with distinct gene signatures at diagnosis or relapse, respectively, shared an identical TCR genotype (TCR Dx-Rel major clone or M clone; T593 and T856; Figure 3G-H). In-depth differentiation states assessment for the persisted major TCR clones from diagnosis to relapse in patients T593 and T856 exhibited relatively consistent stage distributions throughout the disease course, supporting a relatively indolent cellular status with dynamic expression transition underlying the emergence of leukemic recurrences (supplemental Figure 7).

Clonal progression trajectory deconvolution from single-cell transcriptomic and single-cell TCR profiles of Dx_Rel T-ALL pairs. (A-D) UMAP plot of cell points clustered according to the overlaid gene signature identities (first column, clusters demarcated by color) and to disease course (second column, diagnostic identities in blue, relapsed identities in pink) for patients T723 (A), T956 (B), T593 (C), and T856 (D). (E-H) UMAP plot (left column) of cell points colored according to TCR-based genotyping identities for patients T723 (E), T956 (F), T593 (G), and T856 (H) at diagnosis and relapse. Subcluster colors represent the TCR clonotypes based on TCR CDR3 analysis. For patients T723 and T956, identities in orange represent major TCR clonotypes at diagnosis (Dx major); the identities in purple represent the major TCR clonotype at relapse (Rel major). For patients T593 and T856, cell identities with respectively identical TCR clonotypes persisting from diagnosis to relapse are denoted in orange. Other than the above-mentioned cell identities, the minor TCR clonotypes are all display in gray. Stacked bar plots of TCR-based clonotype compositions at diagnosis and relapse are displayed accordingly in the right column.

Clonal progression trajectory deconvolution from single-cell transcriptomic and single-cell TCR profiles of Dx_Rel T-ALL pairs. (A-D) UMAP plot of cell points clustered according to the overlaid gene signature identities (first column, clusters demarcated by color) and to disease course (second column, diagnostic identities in blue, relapsed identities in pink) for patients T723 (A), T956 (B), T593 (C), and T856 (D). (E-H) UMAP plot (left column) of cell points colored according to TCR-based genotyping identities for patients T723 (E), T956 (F), T593 (G), and T856 (H) at diagnosis and relapse. Subcluster colors represent the TCR clonotypes based on TCR CDR3 analysis. For patients T723 and T956, identities in orange represent major TCR clonotypes at diagnosis (Dx major); the identities in purple represent the major TCR clonotype at relapse (Rel major). For patients T593 and T856, cell identities with respectively identical TCR clonotypes persisting from diagnosis to relapse are denoted in orange. Other than the above-mentioned cell identities, the minor TCR clonotypes are all display in gray. Stacked bar plots of TCR-based clonotype compositions at diagnosis and relapse are displayed accordingly in the right column.

To unambiguously define the clonal assignments with super-precise resolution and to fully resolve the clonal evolution patterns, we designed a targeted scDNA-seq library within a custom panel, covering 127 amplicons and 102 genes and used it to establish a comprehensive view of leukemic clonality in the 4 non-ETP ALL Dx_Rel pairs. A total of 46 434 cells were sequenced via the Tapestri platform, with 46 234 cells passing quality control for genomic alterations analysis (supplemental Table 10).

Following the screening of patient-specific genetic variants to identify the clonal architecture present from diagnosis to relapse, we inferred the occurrence and order of mutational acquisitions and assigned genomic-based subclonal information to previous TCR-defined clonalities. Concordant with the discovery of a clonal shift within the scTCR-seq data, single-cell mutational tracing of patient T723 (Figure 4A) revealed an evident dominant clonal alteration from a predominant clone with mutations FBXW7R465C/PTENR233Cfs∗24/PTENN262Qfs∗35 at diagnosis to a minor clone (0.095%, 4 of 4227 cells) with the mutation FBXW7R505C at relapse. Likewise, dominant clonal switching was witnessed in patient T956 (Figure 4B), because a diagnostic subclone with PTENQ214∗/FBXW7R465H was substituted for an initially rare clone (0.086%, 5 of 5800) harboring PTENF241_E242insV, confirming that there was synchronous TCR clonal competition accompanied by dynamic transcriptional variance (Figure 3A-B). In contrast, in Dx_Rel pair T593, competing parallel clones, such as C1 with EZH2F145L/NOTCH1Q2501∗/NOTCH1I1680S, C2 with EZH2F145L/EZH2D730∗/KDM6AR1111C, and C3 with EZH2F145L/NOTCH1Q2501∗ (Figure 4C), persisted throughout chemotherapy. Interestingly, all 3 subclones harboring the same mutation EZH2F145L indicated that these subclones potentially originated from the same initiated ancestry clone, which corresponded to the clonotypes from scTCR-seq (Figure 3G).Similarly, in T856, the founder branching clones C1(EZH2G159R/PTENP246_L247insTLCV), C2(EZH2G159R), and C3(EZH2G159R/NT5C2R367Q; Figure 4D), which, as a whole, manifested transcriptomic divergence from diagnosis to relapse (Figure 3D), also presumably originated from the same initiating clones (EZH2G159R), as evidenced by scTCR-seq results (Figure 3H).

scDNA-seq characterization of distinct clonal evolution patterns in Dx_Rel T-ALL pairs from diagnosis to relapse. (A-D) Fish plots showing dynamic clonal prevalence over time of the 4 patients, T723 (A), T956 (B), T593 (C), and T856 (D), each with a distinct pattern of clonal progression from diagnosis to relapse, with annotations for the genomic alterations in each clone. The left-most clonal composition in each plot represents a snapshot of founder clonal architecture at diagnosis, rather than the parental clones from which all leukemic cells were derived.

scDNA-seq characterization of distinct clonal evolution patterns in Dx_Rel T-ALL pairs from diagnosis to relapse. (A-D) Fish plots showing dynamic clonal prevalence over time of the 4 patients, T723 (A), T956 (B), T593 (C), and T856 (D), each with a distinct pattern of clonal progression from diagnosis to relapse, with annotations for the genomic alterations in each clone. The left-most clonal composition in each plot represents a snapshot of founder clonal architecture at diagnosis, rather than the parental clones from which all leukemic cells were derived.

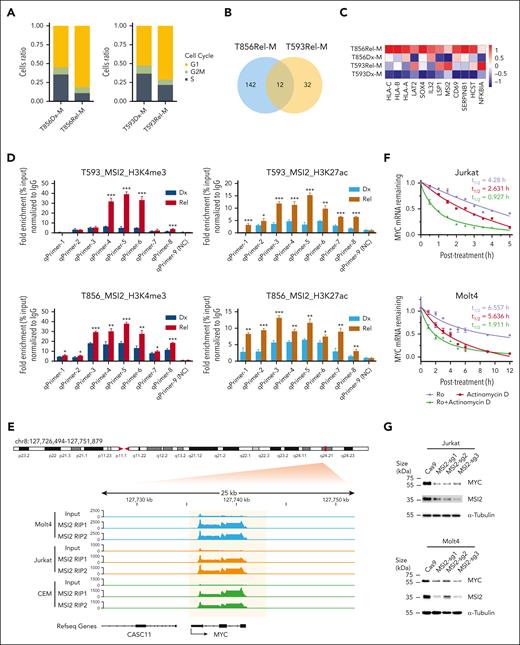

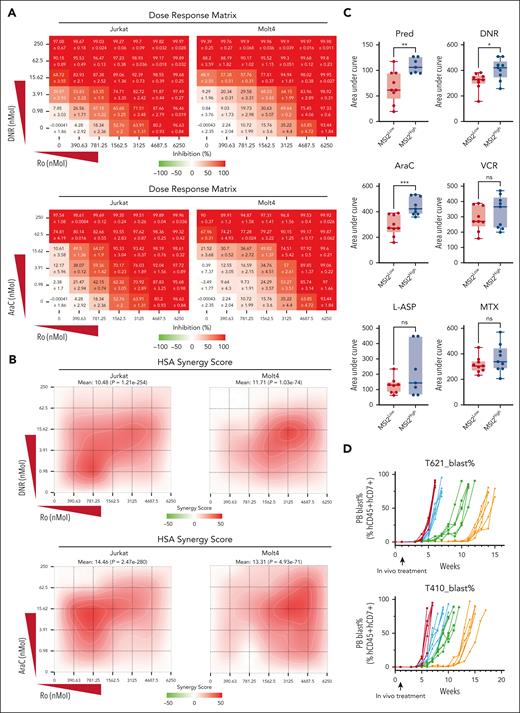

Drifted signature exploration in conserved clones

Based on our highly informative results showing the 2 contrasting clonal progression trajectories, we further investigated the alterations in gene signatures in the persisted TCR-defined major clones. Gene set enrichment analysis of Dx_Rel TCR major clone (M clone) of the Dx_Rel T593 and T856 pairs revealed downregulation of NRAS signaling and cell-cycle signaling at relapse, whereas Gene Ontology analysis highlighted activation of T-cell signaling and cell adhesion pathway at relapse (supplemental Figure 8A-D). Cell-cycle score analysis based on characterized gene signatures (supplemental Table 11) also revealed that a higher proportion M clones were in G1 stage at relapse, with fewer cells residing in S stage than those at diagnosis, indicating there was a stagnation of proliferation after clonal signature drift at relapse (Figure 5A; supplemental Table 12). We then further identified the 12 most frequently upregulated genes commonly enriched in diagnosis-to-relapse static clones from both patients, in which RNA-binding protein Musashi-2 (MSI2), showing the most prominent Dx-Rel differential expression pattern across drifted subclones (Figure 5B-C; supplemental Table 13), caught our attention as a potential indicator of intrinsic clonal progression related to chemotherapeutic resistance. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis of the leukemic cells from patients T593 and T856 confirmed consistently remarkably elevated accumulation of trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 and acetylation of histone H3 lysine 27 at MSI2 transcription start sites from both cases at relapse in contrast to those from leukemia cells at diagnosis, respectively, indicating increased transcriptional initiation of MSI2 at relapse (Figure 5D).

Determination of featured signatures in clonal drift based on Dx_Rel pairwise analysis of transcriptomic dynamics within a persistent TCR clone. (A) Stacked bar plots comparing cell cycling composition dynamics in persisted Dx-Rel major TCR clonotypes (M clones) from T593 and T856 Dx_Rel paired samples. Clonotypes are derived and ordered according to scTCR clonotyping. (B) Venn diagram showing intersection of commonly upregulated mRNA counts at relapse from drifted TCR M clones across T856 (T856Rel-M, blue) and T593 (T593Rel-M, orange). (C) Heat map showing hierarchy of the topmost significantly differently expressed genes (adjusted P < .05, average log2FC > 1) in drifted TCR clonotypes obtained by FindAllMarkers. Relative gene-expression levels are normalized and visualized by color intensity. Detailed information is provided in supplemental Table 8. (D) Bar plot displaying chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and qPCR analyses of trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3; left panel) and acetylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27ac; right panel) levels on endogenous MSI2 transcriptional start site (TSS) for T593 and T856 from diagnosis to relapse. Data is presented after normalizing to nonspecific binding control as fold enrichment of immunoprecipitated DNA relative to input DNA. Data are presented as mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM). P values were estimated using the 2-tailed Student t test; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001. (E) MSI2 RNA immunoprecipitation and high-throughput mRNA sequencing tracks surrounding the MYC locus of T-ALL cell lines, Molt4 (blue), Jurkat (orange), and CEM (green), with data shown as fold enrichment over input. Pink area indicates MSI2-binding region on MYC mRNA. Number of replicates: Molt4 MSI2, n = 2; Jurkat MSI2, n = 2; and CEM MSI2, n = 2. (F) MYC mRNA half-lives (t1/2) evaluation in T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4, after treating with MSI2 RNA-binding inhibitor Ro at the final concentration of 20 μM in presence or absence of actinomycin D (ActD), in comparison with those in ActD-treated T-ALL cell lines. (G) Western blot assay validation of MYC expression in MSI2-knockout (MSI2KO) T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4. sgRNAs MSI2-sg1, MSI2-sg2 and MSI2-sg3 were used in CRISPR–associated protein 9 (Cas9)-expressed parental cells in the 2-vector CRISPR/Cas9 system. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative chemiluminescence images are shown. (H) MSI2 RNA immunoprecipitation and MYC quantitative PCR of reverse-transcribed complementary DNA (cDNA) after treatment of T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4, with 10 μM of Ro for 6 and 12 hours compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. P values were estimated using the 2-tailed Student t test; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; and ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (I) Western blot assay examination of MYC and cleaved-PARP protein levels after treatment of T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4, with 5, 10, or 20 μM Ro for 12 and 24 hours compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative chemiluminescence images are shown. (J) Comparison of apoptosis in T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat, and Molt4, after treatment with Ro (5 or 10 μM) for 24 and 48 hours compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup by annexin V and DAPI staining. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Representative scatterplots are shown. (K) DNA damage assessment by phosphorylated H2AX (γH2AX) staining of T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4, after treatment with Ro (5 or 10 μM) for 12 hours compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative overlaid histograms are shown.

Determination of featured signatures in clonal drift based on Dx_Rel pairwise analysis of transcriptomic dynamics within a persistent TCR clone. (A) Stacked bar plots comparing cell cycling composition dynamics in persisted Dx-Rel major TCR clonotypes (M clones) from T593 and T856 Dx_Rel paired samples. Clonotypes are derived and ordered according to scTCR clonotyping. (B) Venn diagram showing intersection of commonly upregulated mRNA counts at relapse from drifted TCR M clones across T856 (T856Rel-M, blue) and T593 (T593Rel-M, orange). (C) Heat map showing hierarchy of the topmost significantly differently expressed genes (adjusted P < .05, average log2FC > 1) in drifted TCR clonotypes obtained by FindAllMarkers. Relative gene-expression levels are normalized and visualized by color intensity. Detailed information is provided in supplemental Table 8. (D) Bar plot displaying chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and qPCR analyses of trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3; left panel) and acetylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27ac; right panel) levels on endogenous MSI2 transcriptional start site (TSS) for T593 and T856 from diagnosis to relapse. Data is presented after normalizing to nonspecific binding control as fold enrichment of immunoprecipitated DNA relative to input DNA. Data are presented as mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM). P values were estimated using the 2-tailed Student t test; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001. (E) MSI2 RNA immunoprecipitation and high-throughput mRNA sequencing tracks surrounding the MYC locus of T-ALL cell lines, Molt4 (blue), Jurkat (orange), and CEM (green), with data shown as fold enrichment over input. Pink area indicates MSI2-binding region on MYC mRNA. Number of replicates: Molt4 MSI2, n = 2; Jurkat MSI2, n = 2; and CEM MSI2, n = 2. (F) MYC mRNA half-lives (t1/2) evaluation in T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4, after treating with MSI2 RNA-binding inhibitor Ro at the final concentration of 20 μM in presence or absence of actinomycin D (ActD), in comparison with those in ActD-treated T-ALL cell lines. (G) Western blot assay validation of MYC expression in MSI2-knockout (MSI2KO) T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4. sgRNAs MSI2-sg1, MSI2-sg2 and MSI2-sg3 were used in CRISPR–associated protein 9 (Cas9)-expressed parental cells in the 2-vector CRISPR/Cas9 system. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative chemiluminescence images are shown. (H) MSI2 RNA immunoprecipitation and MYC quantitative PCR of reverse-transcribed complementary DNA (cDNA) after treatment of T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4, with 10 μM of Ro for 6 and 12 hours compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. P values were estimated using the 2-tailed Student t test; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; and ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (I) Western blot assay examination of MYC and cleaved-PARP protein levels after treatment of T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4, with 5, 10, or 20 μM Ro for 12 and 24 hours compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative chemiluminescence images are shown. (J) Comparison of apoptosis in T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat, and Molt4, after treatment with Ro (5 or 10 μM) for 24 and 48 hours compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup by annexin V and DAPI staining. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Representative scatterplots are shown. (K) DNA damage assessment by phosphorylated H2AX (γH2AX) staining of T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4, after treatment with Ro (5 or 10 μM) for 12 hours compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative overlaid histograms are shown.

To explore the putative downstream targets and biological function of MSI2 in T-ALL progression, RNA immunoprecipitation and high-throughput messenger RNA (mRNA) sequencing was performed in the T-ALL cell lines Jurkat, CEM, and Molt4. Integrative analysis returned 4385 shared enriched region counts for putative MSI2 mRNA targets, accounting for 53.9% of total calling peaks across the 3 T-ALL cell lines (supplemental Figure 9A). By comparing all the overlapping mRNAs found in our enrichment analysis and the MSI2-binding motifs reported to be involved in cancer development,32 we detected a consistent significant enrichment of MYC transcript peaks in 3 T-ALL cell lines (Figure 5E). Having validated that MSI2 binds to MYC mRNA, and the occurrence of stable MYC expression in the 3 T-ALL cell lines (supplemental Figure 9B-C). To interpret the specific role of MSI2 in MYC expression at the posttranscriptional level, we conducted an in vitro mRNA decay assay by treating the T-ALL cell lines with MSI2 RNA-binding inhibitor Ro 08-2750 (Ro) at 20 μM, in the presence or absence of transcription inhibitor actinomycin D at a final concentration of 0.1 ug/mL. It turned out that half-lives (t1/2) of MYC mRNA degradation were drastically shortened when the cell lines were pretreated with Ro in the presence of actinomycin D (Figure 5F; supplemental Figure 10A). These results implied that MSI2, as a posttranscriptional regulator, was critical in stabilizing MYC mRNA during T-ALL proliferation. Likewise, we observed diminished MYC protein expression after knocking out MSI2 by CRISPR/CRISPR–associated protein 9 in Jurkat, Molt4, and CEM (MSI2KO with single guide 1– [sg1], sg2-, and sg3-RNA, respectively), indicating a close association between MSI2 and MYC expression (Figure 5G; supplemental Figure 10B). To rule out off-target effects, we validated the rescued MYC expression by overexpressing MSI2 with the synonymous mutated 3' end protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence in MSI2KO T-ALL cell lines, which strongly indicated that MSI2 had MYC-expression regulatory roles in T-ALL (supplemental Figure 11). Furthermore, significantly weaker MYC mRNA binding of MSI2 after Ro exposure for 6 hours was confirmed by RNA immunoprecipitation and quantitative real-time PCR (RIP-qPCR) after treating the cell lines with titrated concentrations of Ro for 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours consecutively in vitro (Figure 5H; supplemental Figure 12A), and dramatically decreased MYC expression and increased cleaved poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) were captured by western blot at 12 and 24 hours (Figure 5I; supplemental Figure 12B), followed by elevated annexin V (+) DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (+) apoptosis at 24 and 48 hours (Figure 5J; supplemental Figure 12C), indicating putative cytotoxic effects of Ro on T-ALL in vitro. Heightened phosphorylated H2AX after Ro treatment, as shown by phosphor-flow analysis, led us to reason that an increase in DNA damage after the deregulation of MYC translation accounted for the significant increase in apoptosis after MSI2 RNA-binding inhibition (Figure 5K; supplemental Figure 12D). Additionally, cell-cycle analyses revealed obvious decreased ratios of cells in S phase, but increases in G0:G1 or G2:M cell ratios after incubation with Ro for 6 hours, indicating probable cell-cycle disturbance after the imbalanced MYC expression (supplemental Figure 13)

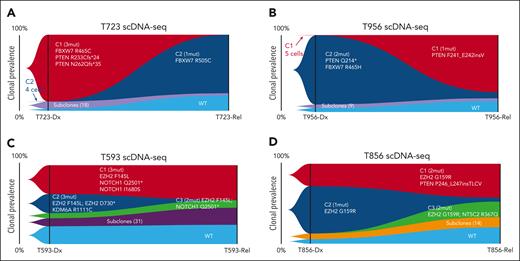

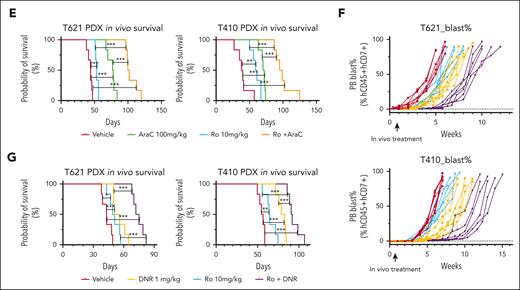

MSI2 as a putative therapeutic target in T-ALL

Next, we focused on deciphering the underlying molecular mechanism of MSI2 upregulation in driving the progression of T-ALL toward relapse. After performing RIP-qPCR and western blotting for primary non-ETP ALL cells from 5 patient-derived xenograft models, we found significant MSI2 binding to MYC transcripts in all the 5 primary T-ALL samples (Figure 6A), and MSI2 and MYC protein expression was also validated (Figure 6B-C). Correspondingly, selectively blocking MSI2 RNA-binding function by Ro treatment for 12 hours could prohibited MSI2’s localization on MYC and induced apoptosis in primary T-ALL leukemic cells in vitro (Figure 6D-E; supplemental Figure 14A-B). In particular, reanalysis of attainable RNA-seq data from the CCCG-ALL-2015 cohort (n = 75, 72 patients with measurable residual disease data)31,33 and TARGET T-ALL cohort (n = 264)5 revealed that higher levels of MSI2 mRNA expression in pediatric T-ALL were correlated with higher measurable residual disease after induction chemotherapy, whereas no significant differences in long-term outcome were obtained from subgroups divided by diagnostic MSI2 expressions (Figure 6F; supplemental Figure 15).34 We then determined the in vivo efficacy of Ro in a T-ALL murine model. After transducing green fluorescent protein (GFP)+ ICN-1(intracellular domain of NOTCH1) into Lin−cKit+Sca1+ cells of C57BL/6 mice and propagating leukemic cells with peripheral burden reaching 5% in the second generation of T-ALL, we treated the mice with Ro (10 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection for 5 consecutive doses every other 2 days (Figure 6G). Log-rank survival analysis showed that blocking MSI2 binding significantly prolonged the leukemia-free survival time of the ICN-1-induced T-ALL mice (P = .0041; Figure 6H). Notably, there was a significantly greater fold change in MSI2 binding on MYC mRNA than the immunoglobulin G control within GFP+ T-ALL leukemic cells via MSI2 RIP-qPCR. In comparison to vehicle treatment, MSI2 enrichment resulted in a >50-fold decrease in MSI2 binding in both subgroups after in vivo Ro treatment (Figure 6I), indicating that MYC expression inhibition by MSI2 functional blockage may serve as a potential therapeutic strategy in T-ALL treatment.

Validation of MSI2 as a putative therapeutic target in patient-derived T-ALL xenograft models and ICN-1-induced murine T-ALL models. (A) MSI2 RNA immunoprecipitation and MYC quantitative PCR of reverse-transcribed cDNA from 5 T-ALL patient-derived xenograft (PDX) samples. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. (B) Relative MYC mRNA expression levels normalized to GAPDH as control for the 5 T-ALL PDX samples from panel A. (C) Western blot assay validation of MYC and MSI2 expression in the 5 T-ALL PDX samples from panels A-B. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative chemiluminescence images are shown. (D) MSI2 RNA immunoprecipitation and MYC qPCR of reverse-transcribed cDNA after treatment with MSI2 RNA binding inhibitor Ro 08-2750 (10 μM or 20 μM) for 12 hours for T-ALL primary cells from PDX T410 (mentioned in panels A-C) compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. P values were estimated using the 2-tailed Student t test; ∗P < .05 and ∗∗P < .01. (E) Evaluation of apoptosis in T-ALL primary cells from PDX T410 (mentioned in panels A-C) after treatment with Ro 08-2750 (2.5 μM, 5 μM, or 10 μM) for 48 hours compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup by annexin V and DAPI staining. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Representative scatterplots are shown. (F) Comparison of measurable residual disease (MRD) levels at end of induction between patients with higher MSI2 mRNA expression (MSI2high, fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads [FPKM] of ≥20.5) and those with lower MSI2 mRNA levels (MSI2low, FPKM of <20.5) from 2 independent T-ALL cohorts, the TARGET-TALL cohort and the CCCG2015-TALL cohort. P values were estimated using the 2-sided Mann-Whitney U test; ∗P < .05. (G) Schematic for establishment of ICN-1–induced murine T-ALL model (C57BL/6) by intravenous injection of 2 × 106 cells per mouse into lethally irradiated mice, then transplanting GFP+ T-ALL cells into the second generation once blast percentage reached 80% in the peripheral blood. For in vivo efficacy observation, treatment was initiated 4 days after injection. Two groups were assigned vehicle or Ro 08-2750 10 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection (IP) on days 4, 7, 10, 13, and 16. For biological experiments, 3 in vivo treatment groups, vehicle, 10 mg/kg per day Ro 08-2750 IP (1 dose), and 10 mg/kg per day Ro 08-2750 IP for 2 days, were prepared after the GFP+ T-ALL blast percentage reached 30% to 40% in the peripheral blood. MSI2 RIP-qPCR for Myc was performed on sorted BM GFP+ T-ALL cells. (H) Leukemia-free survival estimated for Ro 08-2750 treatment (red) or vehicle (blue) subgroups of ICN-1–induced T-ALL model. P values were estimated using the Cox regression model; the exact P value is provided in the figure. Each treatment group included 7 mice. (I) MSI2 RNA immunoprecipitation and Myc qPCR of reverse-transcribed cDNA from GFP+ T-ALL cells after treatment with Ro 08-2750 (10 mg/kg) for 24 and 48 hours for murine ICN-1 T-ALL model in vivo. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. P values were estimated using the 2-tailed Student t test; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; and ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Validation of MSI2 as a putative therapeutic target in patient-derived T-ALL xenograft models and ICN-1-induced murine T-ALL models. (A) MSI2 RNA immunoprecipitation and MYC quantitative PCR of reverse-transcribed cDNA from 5 T-ALL patient-derived xenograft (PDX) samples. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. (B) Relative MYC mRNA expression levels normalized to GAPDH as control for the 5 T-ALL PDX samples from panel A. (C) Western blot assay validation of MYC and MSI2 expression in the 5 T-ALL PDX samples from panels A-B. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative chemiluminescence images are shown. (D) MSI2 RNA immunoprecipitation and MYC qPCR of reverse-transcribed cDNA after treatment with MSI2 RNA binding inhibitor Ro 08-2750 (10 μM or 20 μM) for 12 hours for T-ALL primary cells from PDX T410 (mentioned in panels A-C) compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. P values were estimated using the 2-tailed Student t test; ∗P < .05 and ∗∗P < .01. (E) Evaluation of apoptosis in T-ALL primary cells from PDX T410 (mentioned in panels A-C) after treatment with Ro 08-2750 (2.5 μM, 5 μM, or 10 μM) for 48 hours compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup by annexin V and DAPI staining. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Representative scatterplots are shown. (F) Comparison of measurable residual disease (MRD) levels at end of induction between patients with higher MSI2 mRNA expression (MSI2high, fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads [FPKM] of ≥20.5) and those with lower MSI2 mRNA levels (MSI2low, FPKM of <20.5) from 2 independent T-ALL cohorts, the TARGET-TALL cohort and the CCCG2015-TALL cohort. P values were estimated using the 2-sided Mann-Whitney U test; ∗P < .05. (G) Schematic for establishment of ICN-1–induced murine T-ALL model (C57BL/6) by intravenous injection of 2 × 106 cells per mouse into lethally irradiated mice, then transplanting GFP+ T-ALL cells into the second generation once blast percentage reached 80% in the peripheral blood. For in vivo efficacy observation, treatment was initiated 4 days after injection. Two groups were assigned vehicle or Ro 08-2750 10 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection (IP) on days 4, 7, 10, 13, and 16. For biological experiments, 3 in vivo treatment groups, vehicle, 10 mg/kg per day Ro 08-2750 IP (1 dose), and 10 mg/kg per day Ro 08-2750 IP for 2 days, were prepared after the GFP+ T-ALL blast percentage reached 30% to 40% in the peripheral blood. MSI2 RIP-qPCR for Myc was performed on sorted BM GFP+ T-ALL cells. (H) Leukemia-free survival estimated for Ro 08-2750 treatment (red) or vehicle (blue) subgroups of ICN-1–induced T-ALL model. P values were estimated using the Cox regression model; the exact P value is provided in the figure. Each treatment group included 7 mice. (I) MSI2 RNA immunoprecipitation and Myc qPCR of reverse-transcribed cDNA from GFP+ T-ALL cells after treatment with Ro 08-2750 (10 mg/kg) for 24 and 48 hours for murine ICN-1 T-ALL model in vivo. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. P values were estimated using the 2-tailed Student t test; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; and ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

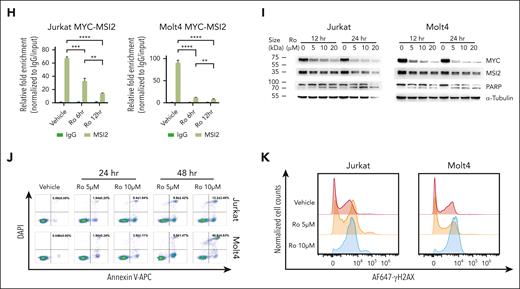

MSI2 inhibition sensitized T-ALL to chemotherapy

To determine the functional roles of MSI2 levels in the chemotherapy resistance of T-ALL, we performed in vitro pharmacotyping analysis after endogenously knocking out or exogenously overexpressing MSI2 in T-ALL cell lines. Notably, MSI2 overexpression significantly induced chemotherapeutic resistance in T-ALL (Jurkat, CEM, and Molt4), as confirmed by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dimethyltetrazolium bromide; 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay of 4 critical chemotherapy drugs used in clinical practice, daunorubicin (DNR), cytarabine (AraC), vincristine, and methotrexate (supplemental Figure 16A-B). In addition, knocking out MSI2 significantly sensitized T-ALL cell lines to the chemotherapeutic drugs (supplemental Figure 16C). Given the effect of MSI2 on MYC mRNA, we aimed to rescue the MSI2KO phenotype through MYC overexpression in MSI2KO T-ALL. Overexpressing the MYC protein in MSI2KO Jurkat cells attenuated the sensitized phenotype, as shown by MTT assay, verifying the critical downstream roles of MYC in MSI2 upregulation in T-ALL chemotherapy resistance (supplemental Figure 16D-E). Moreover, we applied a combination of 2 drugs in MTT assays to investigate the potential impact of MSI2 inhibition in reversing chemotherapeutic resistance. Intriguingly, Ro treatment was demonstrated to synergistically sensitize T-ALL cell lines (Jurkat and Molt4) to chemotherapy, as evidenced by the remarkable dose-response matrix with significant highest single-agent synergy scores (Figure 7A-B; supplemental Figure 16F; supplemental Tables 14 and 15). Consistent with our findings from in vitro pharmacotyping profiling, we observed significant correlation between elevated MIS2 mRNA and resistance to prednisone, DNR, and AraC from ex vivo drug response assay (Figure 7C). Finally, we rationally assessed the in vivo efficacies of MSI2 inhibition therapies by treating 2 patient-derived T-ALL xenograft models with vehicle (group 1), 10 mg/kg Ro (group 2), 100 mg/kg AraC or DNR 1mg/kg (group 3), or a combination of Ro + AraC/DNR (group 4; supplemental Figure 17). Peripheral blast monitoring and survival analysis revealed that the leukemic burden speed in the peripheral blood was effectively slowed, significantly prolonging the lifespan of the mice in the AraC + Ro and DNR + Ro combination subgroups when compared with those in the single-drug and vehicle groups (Figure 7D-G).

Functional roles of MSI2 levels in overcoming chemotherapy resistance of T-ALL. (A) Dose-response matrix (inhibition) of T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4, exhibiting in vitro viability profiling after combination treatment with titrated DNR (left panel)/AraC (right panel) and Ro for 72 hours. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative dose-response matrixes are shown. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. (B) Two dimensional synergy map visualization of 2-drug combinational score distribution in T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4, based on in vitro dose-response viability profiling after combination treatment with titrated DNR (left panel)/AraC (right panel) and Ro for 72 hours. The synergy score was calculated in reference to highest single-agent (HSA) model. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative synergy maps are shown. (C) Distribution of area under curve by dose-response curves of chemotherapeutic drugs from 18 biologically independent primary T-ALL samples are shown in boxplots comparing samples with higher MSI2 mRNA expression (MSI2high, FPKM ≥20.5, n = 9) and those with lower MSI2 mRNA expressions (MSI2low, FPKM <20.5, n = 9). P values were estimated using Mann-Whitney U test; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001; ns, no significance. (D) Leukemia burden in each subgroup of vehicle (red), Ro (blue), AraC (green), and Ro + AraC (orange) from 2 T-ALL PDX models were tracked weekly as percentage of human cytometric CD45+CD7+ cells in all mononuclear cells in peripheral blood (PB) after red blood cell lysis. (E) Leukemia-free survival estimated for each subgroup of vehicle (red), Ro (blue), AraC (green), and Ro + AraC (orange) from T-ALL PDX models. P values were estimated using Cox regression model. Each treatment group included 6 mice. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001. (F) Leukemia burden in each subgroup of vehicle (red), Ro (blue), DNR (yellow), and Ro + AraC (purple) from 2 T-ALL PDX models were tracked weekly as percentage of human cytometric CD45+CD7+ cells in all mononuclear cells in the PB after red blood cell lysis. (G) Leukemia-free survival estimated for each subgroup of vehicle (red), Ro (blue), DNR (yellow), and Ro + AraC (purple) from T-ALL PDX models. P values were estimated using Cox regression model. Each treatment group included 6 mice; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001.

Functional roles of MSI2 levels in overcoming chemotherapy resistance of T-ALL. (A) Dose-response matrix (inhibition) of T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4, exhibiting in vitro viability profiling after combination treatment with titrated DNR (left panel)/AraC (right panel) and Ro for 72 hours. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative dose-response matrixes are shown. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. (B) Two dimensional synergy map visualization of 2-drug combinational score distribution in T-ALL cell lines, Jurkat and Molt4, based on in vitro dose-response viability profiling after combination treatment with titrated DNR (left panel)/AraC (right panel) and Ro for 72 hours. The synergy score was calculated in reference to highest single-agent (HSA) model. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative synergy maps are shown. (C) Distribution of area under curve by dose-response curves of chemotherapeutic drugs from 18 biologically independent primary T-ALL samples are shown in boxplots comparing samples with higher MSI2 mRNA expression (MSI2high, FPKM ≥20.5, n = 9) and those with lower MSI2 mRNA expressions (MSI2low, FPKM <20.5, n = 9). P values were estimated using Mann-Whitney U test; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001; ns, no significance. (D) Leukemia burden in each subgroup of vehicle (red), Ro (blue), AraC (green), and Ro + AraC (orange) from 2 T-ALL PDX models were tracked weekly as percentage of human cytometric CD45+CD7+ cells in all mononuclear cells in peripheral blood (PB) after red blood cell lysis. (E) Leukemia-free survival estimated for each subgroup of vehicle (red), Ro (blue), AraC (green), and Ro + AraC (orange) from T-ALL PDX models. P values were estimated using Cox regression model. Each treatment group included 6 mice. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001. (F) Leukemia burden in each subgroup of vehicle (red), Ro (blue), DNR (yellow), and Ro + AraC (purple) from 2 T-ALL PDX models were tracked weekly as percentage of human cytometric CD45+CD7+ cells in all mononuclear cells in the PB after red blood cell lysis. (G) Leukemia-free survival estimated for each subgroup of vehicle (red), Ro (blue), DNR (yellow), and Ro + AraC (purple) from T-ALL PDX models. P values were estimated using Cox regression model. Each treatment group included 6 mice; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001.

Discussion

In our study, we accurately distinguished leukemic cells from nonleukemic T cells in diagnosis- and relapse-stage T-ALL samples by simultaneously conducting single-cell transcriptomic sequencing and scTCR-seq. By tracking the single-cell transcriptome and incorporating single-cell genetic profiles of paired Dx_Rel T-ALL samples, we further identified the presence of 2 distinct clonal evolutionary patterns corresponding to the divergent fates of “dynamic” and “stable” leukemic clones in response to therapeutic pressures.

One evolutionary pattern indicated the occurrence of a powerful clonal shift, characterized by fluctuations in the dominant clones and the subsidence of sensitive subclones, and initially negligible but resistant subclones, were selectively enriched throughout the course of cytotoxic chemotherapy. This pattern corresponds well to current pathogenic milieu that was seen by scDNA-seq.20-22 In line with that report, our multidimensional interpretation revealed the coexistence of 1 other evolutionary pattern, “clonal drift,” when leukemic cells attained reproductive fitness from maintaining a mutational static status but with remarkable transcriptomic variation in persistent subclones.

In using a well-established model to interpret the occurrence of resistant clones, previous studies have highlighted that an increase in the amount of transcriptomic events accounts for the therapeutic resistance involved with cancer relapse.35-37 Molecular biomarkers predictive of drug sensitivity have been extensively studied using the aid of pairwise Dx_Rel ALL cohorts.38-40 Besides clonal selection at the genetic level, Turati et al41 have depicted an intriguing evolutionary model, showing robust epigenetic and transcriptional progression within a phenotypically uniform population during induction chemotherapy in B-cell precursor ALL by single-cell and multiomics analyses, emphasizing the importance of exploring a broader range of resistance determinants from multidimensional perspectives. MSI2 serves as an oncoprotein in leukemias42 and reportedly posttranscriptionally regulates an array of putative downstream target mRNAs, such as IKZF2, HOXA9, MYC, and PTEN.43 Previous studies have discovered that high mRNA expression of MSI2 correlates with worse clinical outcomes in AML44 and ALL,45,46 with several studies finding evidence that MSI2 functions in hematopoiesis turnover.47-49 We discovered that mRNA transcripts of MYC, an oncoprotein identified for T-ALL leukemogenesis,9 was a critical downstream target of MSI2 in T-ALL, which is consistent with a previously reported link between MYC and MSI2 in AML.42 Our observation from 2 independent T-ALL cohorts supports that high diagnostic MSI2 expression correlates with uneradicated residual leukemia after intensified chemotherapy, with MSI2high in drifted clones also being verified as the drug resistance signature during relapses. However, initially MSI2high is not likely to be linked to long-term outcome, which is subjected to various factors throughout disease courses. Most intriguingly, we confirmed that inhibiting MSI2 could synergistically sensitized T-ALL to chemotherapy in vitro, and that it substantially delayed leukemia progression in vivo, therefore extending MSI2 as a possible outcome predictor as well as a molecular therapeutic target in relapse/refractory T-ALL.

Our study, leveraging single-cell multiomics profiling, has provided a snapshot of the clonal architecture evolution that occurs from diagnosis to relapse in T-ALL. Our multidimensional evidence demonstrates the coexistence of clonal shift and clonal drift in leukemic progression, broadening our current understanding of clonal evolution under the circumstances of intratumoral heterogeneity. Systemic analysis of drifted T-ALL clones has provided compelling evidence of potential signature correlation with leukemic progression to chemotherapy resistance in static subclones, such as the posttranscriptional regulatory effect of MSI2 on MYC and its role in leukemic reoccurrence, which warrants further explorations into MSI2 as a promising drug target of relapse/refractory T-ALL in future practice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China grant (2021YFA1101603 [Y.Z.]); Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences grants (2022-I2M-1-022 [X.Z.], 2021-1-I2M-1-040 [T.C.], and 2022-I2M-C&T-B-088 [J.Z.]); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82270189 [J.Z.] and 81890992 [Y.Z.]); the Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2021-PT310-005 [Y.Z.]); and the Haihe Laboratory of Cell Ecosystem Innovation Fund (22HHXBSS00039 [Y.Z.]).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, or the decision to publish or the preparation of the manuscript.

Authorship

Contribution: Y. Zhang and J.Z. conceptualized the studies; J.Z., Y.D., Y. Chang, and P.W. designed and optimized the experimental methodologies and bioinformatic workflow; J.Z., Y.D., T.H., C.L., Xiaoyan Chen, Y.L., S.Z., Xiaoli Chen, L.J., Y. Wu, and X. Cheng performed the experiments; Y. Chang, Y. Wang, and F.D. performed the bioinformatic studies; X.L. W.Y., Xiaojuan Chen, Y.G., L.Z., Y. Chen, Y. Zou, and T.L. acquired patient-associated resources and/or patient samples for the studies; Y. Zhang and J.Z. wrote the original manuscript; T.C. and X.Z. assisted with the review and editing of the manuscript; and J.Z., Y. Zhang, T.C., and X.Z. supervised the studies and manuscript preparation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yingchi Zhang, Institute of Hematology and Blood Diseases Hospital, State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, National Clinical Research Center for Blood Diseases, 288 Nanjing Rd, Heping Dist, Tianjin 300020, China; email: zhangyingchi@ihcams.ac.cn; Xiaofan Zhu, Institute of Hematology and Blood Diseases Hospital, State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, National Clinical Research Center for Blood Diseases, 288 Nanjing Rd, Heping District, Tianjin 300020, China; email: xfzhu@ihcams.ac.cn; and Jingliao Zhang, Institute of Hematology and Blood Diseases Hospital, State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, National Clinical Research Center for Blood Diseases, 288 Nanjing Rd, Heping District, Tianjin 300020, China; email: zhangjingliao@ihcams.ac.cn.

References

Author notes

∗J.Z., Y.D., P.W., and Y. Chang contributed equally to this study.

The data sets (raw data) generated by this study are available through the Genome Sequence Archive, BioProject ID: PRJCA005363, accession ID: HRA000909. Reference genome data for single-cell RNA sequencing and single-cell T-cell receptor sequencing analysis were downloaded from https://support.10xgenomics.com. For the databases, we used MSigDB (http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp). All other data supporting the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding authors, Yingchi Zhang (zhangyingchi@ihcams.ac.cn), Xiaofan Zhu (xfzhu@ihcams.ac.cn), and Jingliao Zhang (zhangjingliao@ihcams.ac.cn).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![Bulk and single-cell multiomics analyses of 5 diagnosis–relapse T-ALL pairs. (A) Schematic workflow of bulk whole-exome sequencing, single-cell transcriptomic analysis (5′ scRNA-seq) with paired single-cell TCR genotyping (scTCR-seq), and scDNA-seq of CD7+ BMMCs from 5 Dx_Rel paired T-ALL samples and samples from 2 HDs. (B) Oncoprint pairwise analysis of somatic variances in leukemia cells from samples from 5 patients (T956, T723, T593, T856, and T788) at diagnosis (Dx) and relapse (Rel) by whole-exome sequencing. Detailed mutational information is shown in supplemental Table 2. (C) UMAP plot showing 9 distinct T-lineage clusters (demarcated by color) based on the gene-expression profiles of isolated CD7+ BMMCs in Dx_Rel paired samples from 5 patients. (D) UMAP plots displaying distinct identities of each Dx (first row) and the corresponding Rel sample (second row) based on the sample signatures overlaid in panel C. (E) UMAP plot showing cell points colored according to TCR clonality in CD7+ BMMCs from the 5 Dx_Rel pairs. The color of each cell point indicates clonal abundance, and the gray color indicates a lack of TCR. (F) Dot plot showing the top significantly differently expressed genes (adjusted P < .05, average log2 fold change [FC] > 0) of each cluster obtained by FindAllMarkers. Gene-expression frequency (percentage of cells within each cell type expressing the gene) is indicated by spot size, and expression level is indicated by color intensity. (G) Violin plot depicting expression levels of featured gene, CD74, in cluster 9 (blue) and cluster 12 (cyan). (H-I) Sanger sequencing validation of FBXW7 mutation status of CD7+CD74+ normal T cells and CD7+CD74− leukemic cells from patients T956 (F) and T723 (G) individually sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/143/4/10.1182_blood.2023020490/1/m_blood_bld-2023-020490-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1769084264&Signature=jCoPbmERen1qdIxMfO2issQ~-QTdOluoKCAzpgYlddfzX7q8m1xUgozArOi~CNwwmxouNSegIH8Wma05PQyJkgDbUujrZaZ16r78cKZ1vcZ3ChZdWb9c1H2s0pKXZAWjJ0S5lDFUJxKubLE5ab-RbawMOd-MMBTP3IvudWG4NeCzZXz2TYosMMvW10uOY28RYtpuBGmhh0WPuRO6unpQsU0augkel5oO7alwRDoQwa5-IojFT~YhJNnRdiSCG7LIzsjyLEAcDlh63ICAHGpuckDPlN4TE7xHGiuf7CaHFf0QU~BpEu9aiqTWttLwBOirRrtgqeIwX16FgyB6l9BtwA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Validation of MSI2 as a putative therapeutic target in patient-derived T-ALL xenograft models and ICN-1-induced murine T-ALL models. (A) MSI2 RNA immunoprecipitation and MYC quantitative PCR of reverse-transcribed cDNA from 5 T-ALL patient-derived xenograft (PDX) samples. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. (B) Relative MYC mRNA expression levels normalized to GAPDH as control for the 5 T-ALL PDX samples from panel A. (C) Western blot assay validation of MYC and MSI2 expression in the 5 T-ALL PDX samples from panels A-B. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative chemiluminescence images are shown. (D) MSI2 RNA immunoprecipitation and MYC qPCR of reverse-transcribed cDNA after treatment with MSI2 RNA binding inhibitor Ro 08-2750 (10 μM or 20 μM) for 12 hours for T-ALL primary cells from PDX T410 (mentioned in panels A-C) compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. P values were estimated using the 2-tailed Student t test; ∗P < .05 and ∗∗P < .01. (E) Evaluation of apoptosis in T-ALL primary cells from PDX T410 (mentioned in panels A-C) after treatment with Ro 08-2750 (2.5 μM, 5 μM, or 10 μM) for 48 hours compared with the no-treatment vehicle subgroup by annexin V and DAPI staining. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Representative scatterplots are shown. (F) Comparison of measurable residual disease (MRD) levels at end of induction between patients with higher MSI2 mRNA expression (MSI2high, fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads [FPKM] of ≥20.5) and those with lower MSI2 mRNA levels (MSI2low, FPKM of <20.5) from 2 independent T-ALL cohorts, the TARGET-TALL cohort and the CCCG2015-TALL cohort. P values were estimated using the 2-sided Mann-Whitney U test; ∗P < .05. (G) Schematic for establishment of ICN-1–induced murine T-ALL model (C57BL/6) by intravenous injection of 2 × 106 cells per mouse into lethally irradiated mice, then transplanting GFP+ T-ALL cells into the second generation once blast percentage reached 80% in the peripheral blood. For in vivo efficacy observation, treatment was initiated 4 days after injection. Two groups were assigned vehicle or Ro 08-2750 10 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection (IP) on days 4, 7, 10, 13, and 16. For biological experiments, 3 in vivo treatment groups, vehicle, 10 mg/kg per day Ro 08-2750 IP (1 dose), and 10 mg/kg per day Ro 08-2750 IP for 2 days, were prepared after the GFP+ T-ALL blast percentage reached 30% to 40% in the peripheral blood. MSI2 RIP-qPCR for Myc was performed on sorted BM GFP+ T-ALL cells. (H) Leukemia-free survival estimated for Ro 08-2750 treatment (red) or vehicle (blue) subgroups of ICN-1–induced T-ALL model. P values were estimated using the Cox regression model; the exact P value is provided in the figure. Each treatment group included 7 mice. (I) MSI2 RNA immunoprecipitation and Myc qPCR of reverse-transcribed cDNA from GFP+ T-ALL cells after treatment with Ro 08-2750 (10 mg/kg) for 24 and 48 hours for murine ICN-1 T-ALL model in vivo. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. P values were estimated using the 2-tailed Student t test; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; and ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/143/4/10.1182_blood.2023020490/1/m_blood_bld-2023-020490-gr6.jpeg?Expires=1769084264&Signature=N~IM8Z22LveITI10GXbx15yWTDIgoIwa9AFVuE4KqSMo7Ayk-iL9XI5k4ByI8eTwTFOceqZm~RVpO0AzXOV6YqyxiKDzpZKlNlBc9qWiC0B8grkAzRmXwWAhGGWMcIfN0odS733wu2ofwzRj49kYNYE51KUZfg9v475vad4KRIbjiotHfXnTEMrghIrWwGPxECq~zbr4kTvQnJxsaVTXkc0sFSbJVYTOHAvSp-0HrDcvVyl4Z1YXNxN1mPfM1n6Ww~S96D6QxuGszqgE5oQNv-dNbSmiL2L7xZyuCicdZ8aWTwVtAhOlOcNZVtz6MeDaI5i3apEzouYgtIz0TmBoww__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal