Disruption of the GPIb-flnA interaction is sufficient to induce macrothrombocytopenia.

The macrothrombocytopenia phenotype is associated with aberrant megakaryocyte membrane budding.

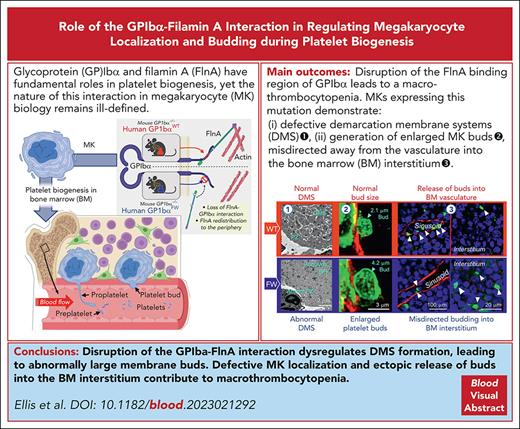

Visual Abstract

Glycoprotein Ibα (GPIbα) is expressed on the surface of platelets and megakaryocytes (MKs) and anchored to the membrane skeleton by filamin A (flnA). Although GPIb and flnA have fundamental roles in platelet biogenesis, the nature of this interaction in megakaryocyte biology remains ill-defined. We generated a mouse model expressing either human wild-type (WT) GPIbα (hGPIbαWT) or a flnA-binding mutant (hGPIbαFW) and lacking endogenous mouse GPIbα. Mice expressing the mutant GPIbα transgene exhibited macrothrombocytopenia with preserved GPIb surface expression. Platelet clearance was normal and differentiation of MKs to proplatelets was unimpaired in hGPIbαFW mice. The most striking abnormalities in hGPIbαFW MKs were the defective formation of the demarcation membrane system (DMS) and the redistribution of flnA from the cytoplasm to the peripheral margin of MKs. These abnormalities led to disorganized internal MK membranes and the generation of enlarged megakaryocyte membrane buds. The defective flnA-GPIbα interaction also resulted in misdirected release of buds away from the vasculature into bone marrow interstitium. Restoring the linkage between flnA and GPIbα corrected the flnA redistribution within MKs and DMS ultrastructural defects as well as restored normal bud size and release into sinusoids. These studies define a new mechanism of macrothrombocytopenia resulting from dysregulated MK budding. The link between flnA and GPIbα is not essential for the MK budding process, however, it plays a major role in regulating the structure of the DMS, bud morphogenesis, and the localized release of buds into the circulation.

Introduction

Bernard–Soulier syndrome (BSS) is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by quantitative or qualitative abnormalities of the glycoprotein Ib-IX-V complex (GPIb-IX-V), the receptor for von Willebrand factor (VWF). BSS is a rare inherited bleeding disorder with an incidence of <1 case per million1 and associated with thrombocytopenia, giant platelets, and increased number of megakaryocytes (MKs) in the bone marrow.2 Although mutations involving GPIX are the single commonest cause of BSS, mutations involving GPIbα or GPIbβ are responsible for up to half of all cases.3 Mouse models of BSS recapitulate the human disease and are characterized by defective platelet production from structurally abnormal MKs within the bone marrow.4

Megakaryocyte (MK) maturation relies on a process of cytoplasmic maturation resulting in the formation of the demarcation membrane system (DMS),5 thought to function as a membrane reserve for platelet production.6 The current prevailing model of platelet formation from the MK relies on the use of this membrane reserve to transform the mature MK into a unique cell structure with pronounced ‘pseudopod-like’ membrane projections. These structures, known as proplatelets, are generated by the outflow and evagination of the DMS internal membrane, with the detachment of individual platelets from the tip of proplatelet extensions first observed more than a century ago.7 Although original descriptions of proplatelet production were based on in vitro observations of cultured MKs, in vivo observations paint a more complex picture. The emigration of entire MKs,8 singular long membrane extensions,9,10 and membrane buds11,12 have all been demonstrated within the bone marrow of mice, suggesting no single model encompasses all the intricacies of in vivo platelet biogenesis. The demonstration that MK-derived buds are identical in size to platelets, have similar ultrastructural features to platelets, and are released directly into bone marrow sinusoids, indicates that budding is a bona fide mechanism of in vivo platelet biogenesis. Whether dysregulation of the MK budding process is linked to the development of macrothrombocytopenias is yet to be established.

In mice lacking GPIb, defective formation of the DMS has been demonstrated,13 with amelioration of the macrothrombocytopenia after insertion of a chimeric Interleukin-4Rα (IL-4Rα) possessing the GPIbα cytoplasmic domain,14 highlighting the importance of the GPIbα cytoplasmic tail in DMS formation. GPIbα interacts with the cytoskeleton through the actin binding protein filamin A (flnA) and the role of flnA in platelets and MKs has been evaluated in mice with genetic deletion of flnA.15 FlnA-null mice are thrombocytopenic with strikingly accelerated platelet clearance, primarily due to spontaneous membrane fragmentation. Ultrastructural examination of flnA-null MKs reveals a poorly defined DMS, without characteristic platelet-forming territories.16 FlnA has numerous functions in megakaryocytes and platelets, including integrin stabilization and signaling roles mediated through RhoA17 and Syk.18 However, given that flnA has up to 100 binding partners,19 this makes it challenging to understand how specific molecular interactions govern platelet biogenesis. Moreover, mice expressing a mutant form of GPIbα lacking the terminal 24 amino acids of the GPIbα intracellular tail, with altered GPIbα signaling function through 14-3-3 and propidium iodine (PI) 3-kinase, but preserved flnA binding, have a mild reduction in platelet count and enlarged platelet size.20 This raises the possibility that interactions other than those through flnA may regulate GPIbα-dependent platelet biogenesis.

The importance of the GPIbα-flnA interaction in regulating GPIbα adhesive function has been investigated in various cell models and mouse platelets.21 Experiments on GPIbα cytoplasmic tail mutants and crystallography studies have demonstrated a critical role of GPIbα hydrophobic residues in mediating the interaction between GPIbα and flnA.21-23 Substitution of Phe568 (F) and Trp570 (W) with alanine (GPIb-FW mutant) prevented the association of flnA with GPIbα in Chinese hamster ovary cells.24 Coexpression of the human GPIbα-FW transgene in mouse platelets also expressing endogenous mouse WT GPIb (hGPIbαFW) have confirmed an essential role of the GPIb-flnA interaction in anchoring the receptor complex to the membrane skeleton and maintaining membrane stability under high shear stress.25 This critical role for GPIbα in regulating membrane stability has been confirmed in platelets from individuals with BSS26 and in mouse platelets lacking flnA.15

How GPIbα regulates the size of formed platelets remains unknown. Abnormalities in the formation of the DMS, defective proplatelet formation,13 and dysregulated MK localization within the marrow compartment8 have provided important insights into the potential defects in platelet production, however, it is unclear how these abnormalities in MK biology dysregulate platelet size. Using our hGPIbαFW mutant mouse model, in which there is a selective disruption in the ability of GPIbα to bind flnA, we demonstrate that the GPIbα-flnA interaction is not essential for proplatelet formation in vitro and in vivo; however, the cytoskeletal anchorage of GPIbα is critical for the development of a well-organized MK DMS. This abnormality in the MK internal membrane reserve did not affect the ability of MKs to form proplatelets or membrane buds in vivo. However, MK buds were enlarged, and their release was misdirected into interstitial bone marrow compartment by ectopically localized MKs, suggesting that dysregulation of MK budding is likely to be an important cause of macrothrombocytopenia.

Materials and methods

Generation of transgenic mice expressing human WT and mutant GPIbα

Mice were generated at Monash Mouseworks according to ethics committee approvals at the Alfred Medical Research & Education Precinct (AMREP) and Monash University School of Biomedical Sciences (application E/0471/2006/M and SOBSA/MW/2008/14BC0). All experimental procedures were approved by ethics committees at the AMREP and The University of Sydney (Project 2017/1175 and 2018/1461). To generate mice expressing either wild-type (WT) human GPIbα or GPIbα mutated at F and W, we used our previously established transgenic mice expressing either hGPIbαWT or hGPIbαFW on a C57BL/6 background.25 To generate mGPIbα–/–/hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα mice, hGPIbαFW mice were crossed with GPIb chimera cIL-4Rα mice whose extracellular domain of GPIbα is replaced with cIL-4Rα as previously described (hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα).14 All strains were born healthy with no observable defects and had a normal life span. All mice were held in a 12-hour night/day cycle and provided ad libitum access to chow and water. Male mice aged 8 to 16 weeks were used for experimental procedures.

Reagents

Biotin anti-mouse CD41 (MWReg30), CD105 (MJ7/18), AlexaFluor647–anti-mouse/rat CD61, and PE–anti-mouse CD41 and DyLight649-Donkey anti-rabbit antibodies were from BioLegend. Paraformaldehyde (PFA) and EDTA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Phalloidin iFluor488 and rabbit anti-mouse flnA antibodies were from Abcam. Mouse anti-human CD42b (SZ-2) was from Beckman Coulter. Allophycocyanin (APC) and AlexaFluor568 streptavidin and Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin were from ThermoFisher. Rat anti-mouse GPIbβ IgG, Dylight-488 or -649 (X488, X649), CD41-PE, and CD42a-FITC monoclonal antibodies were from Emfret Analytics. Rabbit anti-mouse laminin antibody was from Novus Biologicals. WM23 (mouse anti-human GPIbα antibody) was a gift from Michael Berndt (Alfred Medical Research and Education Precinct, Monash University).

Analysis of platelet count and size

Mouse blood was collected via a submandibular bleed into EDTA-anticoagulated tube (EDTA coated pediatric microtainer tubes, BD Biosciences). Platelet count and size were analyzed using an automated blood analyzer (Sysmex KX-21N, Kobe, Japan).

Flow cytometry

Platelet surface expression of hGPIbα and IL-4Rα was measured using EDTA-anticoagulated blood, diluted 1:10 in platelet washing buffer (PWB; 4.3 mM K2HPO4, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 24.3 mM Na2PO4, 113 mM NaCl, 5.5 mM D-glucose, 10 mM theophylline, and 0.5% BSA, pH 6.5) and stained with anti-CD42b-phycoerythrin (PE) or anti-CD124-PE and analyzed by flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6 Plus) using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) or FlowJo software (TreeStar). Platelet size was also assessed by flow cytometry using the forward scatter parameter.

Platelet isolation

Mouse platelets were isolated from EDTA-anticoagulated blood as previously described27 with minor modifications, in which blood was centrifuged at a lower g force (90g × 2’) to obtain giant hGPIbαFW mouse platelets in platelet-rich plasma (PRP). To accurately determine the size of ex vivo platelets, mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (150 mg/kg, Ceva Animal Heal, Glenorie, Australia) and xylazine (15 mg/kg, Trot Laboratories, Glendenning, Australia), and blood was drawn via the inferior vena cava into a syringe containing enoxaparin (400 mg/mL) diluted in 100 μL sterile saline. Anticoagulated whole blood was fixed in 4% PFA at 1:1 ratio (v/v) for 30 minutes. Fixed whole blood was allowed to settle on VWF-coated glass coverslips and pretreated with botrocetin for 1 hour. Unbound cells were removed by gentle washing with PWB. Cells were imaged using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy using a Leica DMIRB (Leica microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), 63× water objective, NA 1.2, and fitted with a Hammamatsu Orca camera (Tokyo, Japan). Images were acquired using the Micromanager plugin (version 1.4.2) for ImageJ.

In vivo platelet life span via biotinylation

In vivo platelet life span was determined using the previously described method.28 Mice were injected with 1.5 mg Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin dissolved in 100 μL sterile saline via the tail vein. Blood samples were collected via tail vein into EDTA-containing syringes at the indicated times, including immediately after injection (0 h), 3 hours after injection, and daily thereafter. Whole blood (5 μL) was washed to remove plasma with PWB and platelets incubated with Streptavidin-APC (1/100) to detect biotin-labeled platelets and CD41-PE (1/100) to label total platelets, for 30 minutes at room temperature, shielded from light. The number of biotin- and CD41-labeled platelets was determined using flow cytometry (BD Accuri C5 plus), in which at least 5000 CD41+ events were collected and analyzed using FlowJo. The proportion of dual-stained platelets relative to the total CD41+ platelets over time was analyzed and expressed as platelet life span.

Isolation and culture of Lin– murine bone marrow cells

Mouse lineage negative (Lin–) bone marrow cells were isolated as previously described.29 Briefly, bone marrow from femora and tibiae bones was flushed out with Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics (1:100 of 10 000 U/mL penicillin and 10 mg/mL streptomycin, Sigma). Lin– cells were obtained by magnetic-activated cell sorting using a Mouse Lineage Cell Depletion Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were cultured at 1 × 106 per mL in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium/10% fetal bovine serum/antibiotics supplemented with 50 ng/mL recombinant mouse thrombopoietin (TPO) (Miltenyi Biotec) at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 4 to 5 days.

Induction of megakaryocyte proplatelet formation in vitro

Proplatelet formation in vitro was performed as previously described.30 Briefly, Lin– cells isolated from murine bone marrow were seeded in duplicate in 24-well plates at 1 × 105 cells per well and cultured as described above in the presence of TPO. Proplatelet bearing MKs were counted on day 4 of culture at 20× magnification using an inverted light microscope (Leica DMIRB). After proplatelet analysis, the cells were collected from culture plates and stained with anti–CD41-PE (Emfret Analytics, Eibelstadt, Germany), and CountBright counting beads (ThermoFisher) were added in accordance with the manufacturer instructions. The total number of CD41+ cells in each well was determined by flow cytometry. Results were expressed as proplatelet bearing MKs per 10 000 total MKs.

Measurements of proplatelet terminal swellings in bone marrow explant culture

To measure the size of proplatelet terminal swellings, bone marrow explants were cultured as described previously.9 Intact marrows were flushed out from mouse femurs with Tyrode buffer containing 0.35% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Ten 0.5 mm thick transversal sections of each bone marrow sample were placed in tissue culture wells, cultured in Tyrode buffer containing 0.35% BSA and 5% mouse serum, in a 37°C CO2 incubator in the absence of thrombopoietin. After ∼20 hours in culture, Alexa 488 anti-CD42c Ab (Emfret) was added to the living tissue sections, and each was examined for proplatelet bearing MKs under confocal and DIC microscopy (Zeiss, LSM800, 40× oil objective, NA 1.3). The size of proplatelet terminal swellings was quantified using CD42c staining and Zeiss inbuilt software and/or Image J, by quantifying the maximal transverse length of individual swellings.

GPIb and GPIIb-IIIa expression on bone marrow megakaryocytes

Day 5 cultured, bone marrow–derived Lin– cells were harvested, washed, and stained with rat anti-mouse CD41-PE and CD42a-FITC monoclonal antibodies (Emfret Analytics, Eibelstadt, Germany) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Free antibody was removed and surface expression of GPIX (CD42a) and GPIIb-IIIa (CD41) determined using flow cytometry (FACSCanto II, BD Biosciences). We elected to use CD42a as the principal MK marker, because CD42a is expressed at higher levels than CD42b on MKs.31 Furthermore, in preliminary studies, we confirmed that GPIb expression patterns on hGPIbαFW mice were similar to that of flnA knockout (KO) mice, in that GPIb levels were normal on MKs but reduced on platelets.15

Megakaryocyte ploidy determination

MK ploidy was determined as previously described.31,32 Briefly, day 5 cultured MKs in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (0.5% BSA/2 mM EDTA, pH 7.2) were stained with anti-mouse CD41-FITC (30 minutes at 4°C) and washed once with the same buffer. The cells were then permeabilized and stained with the nuclear dye propidium iodide (PI) by resuspending cells in hypotonic citrate buffer (1.25 mM sodium citrate, 2.5 mM sodium chloride, and 3.5 mM dextrose) containing 0.05% Triton-X 10 and 20 μg/mL of PI for 15 minutes at 4°C in dark. Ribonuclease (20 μg/mL) was then added to the cell reaction mixture and incubated for a further 30 minutes at 4°C. Ploidy was determined by the number of PI positive events within the CD41+ population, with a minimum of 30 000 events collected by flow cytometry (FACSCanto II, BD Bioscience).

Bone marrow histology

After euthanasia, mouse femurs were isolated, fixed overnight in 2% PFA, and decalcified in 0.5M EDTA for 7 days, exchanging EDTA daily, before being embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Images (40× air objective NA 0.65) were taken on a Zeiss Axioscope upright microscope (Axio Scan 5 with Axiocam 105 camera). Images were analyzed using Zen software and ImageJ.

Transmission electron microscopy

Mouse femurs were harvested, and bone marrow MKs were examined using TEM as previously described.33 Briefly, mouse femurs were flushed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS overnight and embedded in Epon. Transversal thin sections (100 nm) of the entire bone marrow were obtained, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined under a Jeol 2100-Plus transmission electron microscope (120 kV). The number of MKs were counted under the TEM in the entire transversal section and expressed as the density per unit area (defined as one square of the grid, ie, 16 000 μm2). MKs at maturity stages I, II, and III were identified based on distinct ultrastructural characteristics, in which stage I corresponded to a cell 10 μm in diameter with a large nucleus; stage II, to a cell 10 to 20 μm in diameter containing platelet-specific granules; and stage III, mature MKs having a well-developed DMS with clearly defined platelet territories and a peripheral zone.

Immunofluorescence staining of bone marrow and lung tissue

After euthanasia, mouse femurs were removed by dissection, fixed overnight in 2% PFA at 4°C, decalcified for 48 hours in 0.5M EDTA, and incubated overnight in 30% sucrose before embedding in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (ProSciTech) and freezing at −80°C.

The lungs of the euthanized mice were inflated using 1.5% low melting-point agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) with a catheter inserted into the trachea. Lungs were then isolated, fixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4°C, and stored in PBS. Before sectioning, lungs were mounted in 5% agarose.

Decalcified bones were cut into 10 μm thick cryosections (Cryotome FSE, ThermoScientific), and lungs were sectioned (100 μm thick) using a VT 1200 vibratome (Leica Biosystems). Tissue sections were mounted on SuperFrost Plus glass slides (ThermoFisher), blocked for 1 hour with 10% fetal calf serum in PBS containing 0.5% Triton-X100, and stained overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C. After 3 washes with PBS, secondary antibodies, streptavidin, and phalloidin were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Hoechst (1 μg/mL) was incubated for the final 10 minutes where indicated. Slides were washed 3 times in PBS and mounted with ProLong Gold (Confocal microscopy) or ProLong Diamond (for STED).

Confocal imaging

Confocal Imaging was performed using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope. Bone marrow regions free from processing artifacts were selected for examination using a grid of 3D z-stack. For analytic purposes, a 6×6 grid (overlap 10%) z-stack was generated to cover a region ∼750 μm2 (63× oil objective, NA 1.30). Because of the relative infrequency of lung MKs, larger fields were assessed for lung tissue. A similar 6×6 grid (10% overlap) was produced using a 20× objective (air, NA 0.8). Z-stacks (step size – 0.2 μm for bones, 0.8 μm for lungs) encompassed the full thickness of the bone marrow and lung tissues. Individual z-stacks were stitched using Zeiss Zen software (version 2.3). For the purposes of analysis, the entire image was divided into 4 quadrants and analyzed separately. The average value of the 4 regions was determined for each mouse. Images were analyzed using ImageJ (version 1.53c) or Imaris (Bitplane AG, Schlieren, Switzerland; version 9.8). Stitched images were examined for the number of MKs, platelets, and their localization using ImageJ.

Identification of platelets and buds in the bone marrow and proplatelets in lung

Bone marrow intravascular platelets were counted as platelet-sized, CD41+ structures, within vessels delineated by laminin. Interstitial platelet buds were determined using the same criteria, located clearly in the bone marrow interstitium and within a vascular structure. The diameter of MKs and interstitial buds was determined as the maximal length of a line drawn through individual buds. MK buds were defined by its link to the MK outer membrane based on CD41 staining in at least 1 plane. Lung proplatelets were counted as CD41+ structures with thin, irregular protrusions as previously described.34

STED microscopy

Bone marrow cryosections were prepared as for confocal imaging and mounted with ProLong Diamond (ThermoFisher). Images were acquired using a Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) SP8 imaging platform (93× glycerol objective, NA 1.30). Stimulated emission depletion (STED) z-stacks (step size, 0.12-0.20 μm) were collected using LAS X software (version 3.5.7). Image deconvolution was performed using Huygens Software (version 20.04, Scientific Volume Imaging, Hilversum, The Netherlands). Three dimensional renders were created using Imaris (Bitplane AG; version 9.8).

GSD microscopy

Cryosections of mouse femurs of size 3 μm were prepared for confocal imaging. After staining, slides were postfixed with 0.5% PFA for 5 minutes. The imaging buffer consisted of standard imaging buffer (tris/HCl 100 mM, NaCl 20 mM, and glucose 10% vol/vol), mercaptoethylamine (0.1 M), and glucose oxidase/catalase (600 μg/mL and 60 μg/mL, respectively). Ground-state depletion (GSD) images were acquired on a Leica ST GSD (160× oil objective, NA 1.43). d-STORM reconstructions were performed using the ThunderSTORM (version 1.3)35 plugin for ImageJ.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism. Statistical significance was determined using either 2-tailed Student t test or analysis of variance as appropriate (with Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple comparisons). P values <.05 were considered statistically significant (∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, and ∗∗∗∗P < .0001).

Results

Generation of a human transgenic GPIb mouse with defective GPIbα-flnA binding

We have previously generated a mutant human GPIbα transgene that has a selective defect in flnA binding (Phe568Ala and Trp570Ala; FW), termed hGPIbαFW. This transgene and a WT human GPIbα (hGPIbαWT) control have been expressed in C57BL/6 mice, generating mice with both human and endogenous mouse GPIbα (mGPIbα+/+). To generate mice expressing human GPIbα alone on mouse platelets, we crossed GPIbα deficient mice (mGPIbα–/–) with mice expressing either hGPIbαWT or mutant hGPIbαFW to generate mGPIbα–/–/hGPIbαWT or mGPIbα–/–/hGPIbαFW mice. The first generation of mGPIbα+/−/hGPIbαWT mice and mGPIbα+/−/hGPIbαFW were bred to obtain homozygous mGPIbα–/–/hGPIbαWT or mGPIbα–/–/hGPIbαFW mice (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website); throughout the remainder of this study, we refer to these mice as hGPIbαWT or hGPIbαFW, respectively. Both strains were born healthy with no observable defects and had a normal life span.

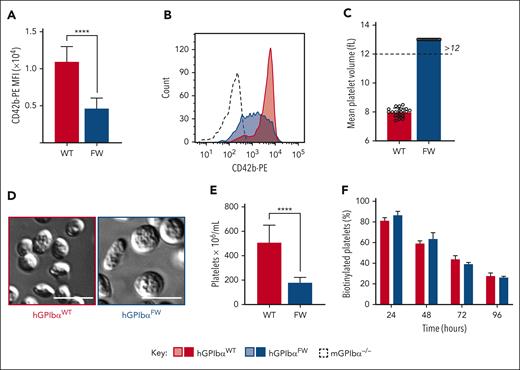

GPIbα-flnA disruption causes a macrothrombocytopenia with preserved platelet GPIb surface expression

BSS is typically associated with mutations in either the GPIbα, GPIbβ, or GPIX genes, leading to macrothrombocytopenia and deficiency of the GPIb-IX-V receptor complex. Genetic deletion of flnA also leads to macrothrombocytopenia; however, the expression of GPIb-IX-V on the surface of platelets is preserved, albeit at ∼50% of normal levels.16 Consistent with this, platelets from hGPIbαFW mice had a 57.6% reduction in GPIb expression levels relative to hGPIbαWT controls (Figure 1A). GPIb expression was broad and heterogeneous within the hGPIbαFW platelet population (Figure 1B). To distinguish the effects of reduced hGPIbα expression levels on the phenotypes of mouse platelets and MKs from alterations related to defective hGPIbα-cytoskeletal anchorage, we selected transgenic WT controls with lower levels of expression of the human hGPIbαWT transgene, similar to hGPIbαFW mice (supplemental Figure 2A). The circulating platelet count in transgenic WT mouse controls was between 400 × 106 and 500 × 106 per mL, ∼50% lower than nontransgenic C57BL/6 mice (950 × 106 to 1050 × 106 per mL; supplemental Figure 2B).

Disruption of GPIbα-flnA interaction induces macrothrombocytopenia with reduced GPIb expression. (A) Anticoagulated whole blood from hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice was assessed for platelet GPIb surface expression by flow cytometry using anti–CD42b-PE Ab. The results are expressed as the mean fluorescence intensity of the gated platelet population (mean ± SEM of n = 20 pairs of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, unpaired t test.). (B) Representative histograms of GPIbα expression (CD42b-PE) in hGPIbαWT (red), hGPIbαFW (blue), and mNull (broken black line) platelets in whole blood. (C) EDTA-anticoagulated whole mouse blood was assessed using a Sysmex blood analyzer for mean platelet volume. Graph demonstrates mean ± SEM of 10 mice from each strain. (D) Representative DIC images of fixed platelets adherent to VWF/botrocetin matrix (scale bar, 3 μm). (E) Platelet count in EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood from hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice was determined using a Sysmex blood analyzer. Results represent the mean ± SEM of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice (n = 20 of each strain), ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, unpaired t test. (F) In vivo platelet life span was determined for hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice using in vivo biotinylation. Results depict the mean ± SEM of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice (n = 4 and n = 5, respectively), P = .8162 for strain comparisons, 2-way ANOVA. Ab, antibody; ANOVA, analysis of variance; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Disruption of GPIbα-flnA interaction induces macrothrombocytopenia with reduced GPIb expression. (A) Anticoagulated whole blood from hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice was assessed for platelet GPIb surface expression by flow cytometry using anti–CD42b-PE Ab. The results are expressed as the mean fluorescence intensity of the gated platelet population (mean ± SEM of n = 20 pairs of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, unpaired t test.). (B) Representative histograms of GPIbα expression (CD42b-PE) in hGPIbαWT (red), hGPIbαFW (blue), and mNull (broken black line) platelets in whole blood. (C) EDTA-anticoagulated whole mouse blood was assessed using a Sysmex blood analyzer for mean platelet volume. Graph demonstrates mean ± SEM of 10 mice from each strain. (D) Representative DIC images of fixed platelets adherent to VWF/botrocetin matrix (scale bar, 3 μm). (E) Platelet count in EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood from hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice was determined using a Sysmex blood analyzer. Results represent the mean ± SEM of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice (n = 20 of each strain), ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, unpaired t test. (F) In vivo platelet life span was determined for hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice using in vivo biotinylation. Results depict the mean ± SEM of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice (n = 4 and n = 5, respectively), P = .8162 for strain comparisons, 2-way ANOVA. Ab, antibody; ANOVA, analysis of variance; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Platelet size was determined using mean platelet volume and changes in forward scatter of CD41-labeled platelets. Both methods revealed enlarged platelets from hGPIbαFW mice (Figure 1C and supplemental Figure 2C). DIC microscopy using washed platelets also confirmed the presence of abnormally large, discoid platelets (Figure 1D). hGPIbαFW mice were thrombocytopenic (Figure 1E), with platelet counts in whole blood ranging from 150× 106 to 200 × 106 per mL. To exclude the possibility that the low platelet count was due to inaccurate counting of very large platelets by the analyzer, we confirmed the low platelet count by performing manual counting with a hemocytometer using isolated mouse platelets. There was no correlation between GPIbα expression level and platelet count in hGPIbαFW mice (supplemental Figure 2D), indicating that lower levels of GPIbα was unlikely to be the primary cause of the macrothrombocytopenia. All other blood counts were similar between strains, with respect to white blood cell and red blood cell parameters (supplemental Table 1).

The similarity in platelet phenotype between hGPIbαFW mice and flnA-deficient platelets raised the possibility that hGPIbαFW platelets may be more rapidly cleared from the circulation. Previous studies have demonstrated that flnA-deficient platelets are intrinsically fragile and undergo microvesiculation in blood and in vitro and are cleared by macrophages.15 To ascertain whether the thrombocytopenic state in hGPIbαFW mice is due to impaired platelet production or excessive clearance, we performed in vivo labeling and determined the lifetime of circulating platelets. Interestingly, we found hGPIbαFW mice had a normal circulating lifetime (Figure 1F), suggesting the defect in platelet numbers is most likely related to defective thrombopoiesis, rather than intravascular microvesiculation and accelerated clearance, as seen with flnA-null platelets.

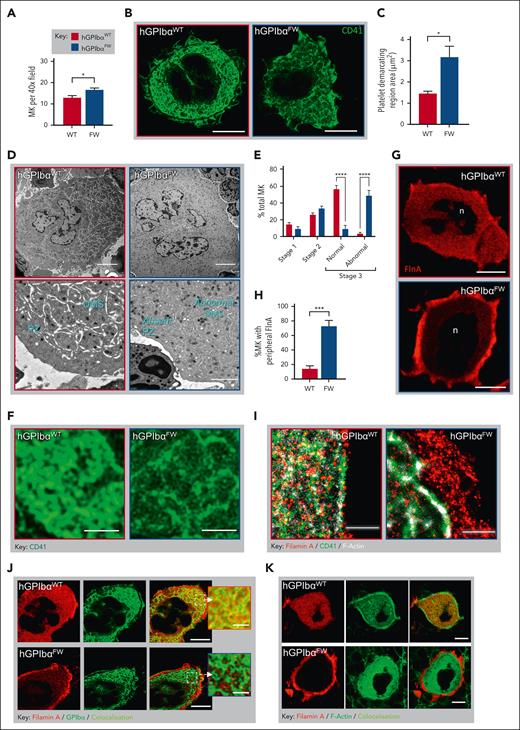

The GPIbα-flnA interaction regulates megakaryocyte flnA distribution and formation of the DMS

To evaluate whether dysregulated platelet production or release into the circulation was the underlying cause of thrombocytopenia in hGPIbαFW mice, we analyzed MKs within femoral bone marrow. There was a 1.4-fold increase in the number of MKs in the bone marrow of hGPIbαFW mice (Figure 2A), and these cells appeared normal by hematoxylin and eosin staining (supplemental Figure 3). Platelet production requires the development of an elaborate internal demarcation membrane structure in MKs. To investigate the potential ultrastructural changes in the DMS of hGPIbαWT mice, we performed superresolution STED microscopy on bone marrow MKs. Using CD41 to label the external and internal membrane reserves of the MK, we observed abnormal formation of DMS internal membranes in the hGPIbαFW mice (Figure 2B). In contrast to the dense CD41 staining of platelet-demarcation territories within hGPIbαWT MKs, more porous and disorganized CD41 staining of the platelet-forming territory was apparent in hGPIbαFW MKs (Figure 2B-C). To further investigate these observations, we examined the ultrastructure of MKs using TEM, which confirmed a striking disorganization of the DMS ultrastructure and the absence of the MK peripheral zone in mature MKs (Figure 2D). Although we found no clear differences in the frequency of the 3 stages of MK ultrastructural maturation,33 there was a greater frequency of morphologically abnormal stage III MKs in hGPIbαFW mice (Figure 2E). These features were confirmed using high magnification of the DMS from STED images of CD41-stained MKs (Figure 2F). Together, these findings demonstrate that the interaction of GPIbα with flnA is critical for normal DMS development.

Disrupted GPIbα-flnA interaction results in megakaryocyte flnA redistribution and structural abnormalities in the DMS. (A) The number of MKs was quantified from H&E-stained femoral bone marrows (10 random fields; 40× objective) and results depict the mean ± SEM of 6 mice; ∗P < .05, unpaired t test. (B-C) Bone marrow MKs were stained with anti-CD41 (green) and imaged using STED microscopy. Representative STED images showing MK CD41 distribution within the DMS in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice (93×; scale bars, 10 μm) (B). Quantification of the CD41-free areas within the DMS territories of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW MKs. Individual platelet-delineating territories were identified by bright CD41 staining and surface area of the territories determined. Data were derived from 3 mice, with at least 5 MKs evaluated per mouse (C). (D-E) Mouse femurs were prepared for TEM and the structure of DMS evaluated within the MK cytoplasm. (D) Representative TEM images of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW bone marrow MKs demonstrating impaired DMS development and absent peripheral zone in hGPIbαFW mice. Note, abnormal DMS formation in mature stage III hGPIbαFW MKs is marked by the lack of white space. Scale bars: top panel 5 μm, bottom panel 2 μm. (E) Bone marrow MK maturation was analyzed using TEM, with DMS classified according to stages I to III as defined under “Methods.” Results depict the mean ± SEM of 3 mice; ∗∗∗∗ P < .001 for strain comparison; 2-way ANOVA. (F) Regions of the DMS were evaluated using high magnification of STED images from (B), highlighting thinner and sparser CD41+ membranes in hGPIbαFW mice (Scale bars, 2 μm). (G-H) The distribution of flnA in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW bone marrow MKs by STED microscopy. (G) Quantification of the percentage (%) of MKs with peripheral distribution of flnA. Results are the mean ± SEM of 30 to 40 MKs from 4 pairs of mice; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, unpaired t test. (H) Representative STED images showing homogeneous and peripheral flnA distribution within MKs in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice, respectively (93×; scale bars, 10 μm). (I) GSD microscopy was performed on 3 μm femoral bone marrow cryosections that were stained with fluorescently labeled phalloidin, anti-CD41 and anti-flnA Abs. Representative GSD images showing peripheral flnA accumulation and loss of colocalization with F-actin and CD41 in hGPIbαFW MKs relative to hGPIbαWT mice (160× oil objective; scale bars, 1 μm). (J-K) hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mouse bone marrow cryosections were stained with anti-flnA and GPIbα Abs and phalloidin. Representative STED images demonstrating peripheral flnA and the loss of its colocalization with GPIbα (J) and F-actin (K) in hGPIbαFW MKs, in contrast to hGPIbαWT cells (93× glycerol objective; scale bars, 10 μm). Ab, antibody; ANOVA, analysis of variance; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Disrupted GPIbα-flnA interaction results in megakaryocyte flnA redistribution and structural abnormalities in the DMS. (A) The number of MKs was quantified from H&E-stained femoral bone marrows (10 random fields; 40× objective) and results depict the mean ± SEM of 6 mice; ∗P < .05, unpaired t test. (B-C) Bone marrow MKs were stained with anti-CD41 (green) and imaged using STED microscopy. Representative STED images showing MK CD41 distribution within the DMS in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice (93×; scale bars, 10 μm) (B). Quantification of the CD41-free areas within the DMS territories of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW MKs. Individual platelet-delineating territories were identified by bright CD41 staining and surface area of the territories determined. Data were derived from 3 mice, with at least 5 MKs evaluated per mouse (C). (D-E) Mouse femurs were prepared for TEM and the structure of DMS evaluated within the MK cytoplasm. (D) Representative TEM images of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW bone marrow MKs demonstrating impaired DMS development and absent peripheral zone in hGPIbαFW mice. Note, abnormal DMS formation in mature stage III hGPIbαFW MKs is marked by the lack of white space. Scale bars: top panel 5 μm, bottom panel 2 μm. (E) Bone marrow MK maturation was analyzed using TEM, with DMS classified according to stages I to III as defined under “Methods.” Results depict the mean ± SEM of 3 mice; ∗∗∗∗ P < .001 for strain comparison; 2-way ANOVA. (F) Regions of the DMS were evaluated using high magnification of STED images from (B), highlighting thinner and sparser CD41+ membranes in hGPIbαFW mice (Scale bars, 2 μm). (G-H) The distribution of flnA in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW bone marrow MKs by STED microscopy. (G) Quantification of the percentage (%) of MKs with peripheral distribution of flnA. Results are the mean ± SEM of 30 to 40 MKs from 4 pairs of mice; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, unpaired t test. (H) Representative STED images showing homogeneous and peripheral flnA distribution within MKs in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice, respectively (93×; scale bars, 10 μm). (I) GSD microscopy was performed on 3 μm femoral bone marrow cryosections that were stained with fluorescently labeled phalloidin, anti-CD41 and anti-flnA Abs. Representative GSD images showing peripheral flnA accumulation and loss of colocalization with F-actin and CD41 in hGPIbαFW MKs relative to hGPIbαWT mice (160× oil objective; scale bars, 1 μm). (J-K) hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mouse bone marrow cryosections were stained with anti-flnA and GPIbα Abs and phalloidin. Representative STED images demonstrating peripheral flnA and the loss of its colocalization with GPIbα (J) and F-actin (K) in hGPIbαFW MKs, in contrast to hGPIbαWT cells (93× glycerol objective; scale bars, 10 μm). Ab, antibody; ANOVA, analysis of variance; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; SEM, standard error of the mean.

To examine the impact of disrupting the link between GPIbα and flnA on the subcellular distribution of flnA, we performed both confocal and STED microscopy on bone marrow MKs stained with an anti-flnA antibody. Although flnA was distributed homogenously throughout the cytoplasm of hGPIbαWT MKs, it was localized to a peripheral ring in the MKs in hGPIbαFW mice (Figure 2G). Quantitative analysis revealed that this pattern of flnA distribution was present in ∼75% of hGPIbαFW MKs compared with 14% of hGPIbαWT MK controls (Figure 2H and supplemental Figure 4). flnA binds to the major platelet adhesion receptors, GPIbα and integrin αIIbβ3, and facilitates their linkages with the actin cytoskeleton. Superresolution GSD microscopy was used to analyze the flnA distribution at the single-molecule level. Although discrete foci of flnA staining were evident throughout the cytoplasm in association with F-actin and CD41 in hGPIbαWT mice, we found a striking accumulation of flnA at the cell periphery, not in direct connection with CD41 or F-actin in hGPIbαFW mice (Figure 2I). We next evaluated the colocalization of flnA with GPIbα and F-actin in both mouse strains and observed loss of the colocalization of flnA with GPIbα and F-actin in hGPIbαFW mice (Figure 2J-K). Interestingly, F-actin and GPIbα were still found homogenously distributed throughout the MK, despite disrupted linkage between flnA and GPIbα in the GPIbαFW cells. Together, these findings indicate that the flnA-GPIbα interaction is pivotal to the normal regulation of flnA distribution within MKs.

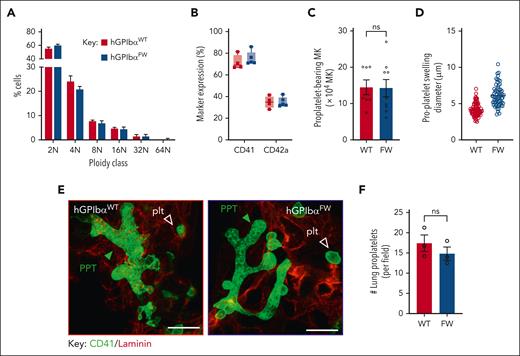

Megakaryocyte differentiation and proplatelet formation occur independently of the GPIb-flnA interaction

To investigate whether changes in the DMS ultrastructure in hGPIbαFW mice lead to defective MK proplatelets, we initially examined proplatelet formation in vitro using cultured MKs derived from hGPIbαFW and hGPIbαWT mice. MKs derived from hGPIbαFW mice underwent normal maturation in vitro, as evidenced by normal MK ploidy and the expression of cell-surface markers of mature MKs (Figure 3A-B). Moreover, disrupting the link between GPIbα and flnA did not impact on the ability of MKs to differentiate into proplatelets (Figure 3C), however, the development of terminal swellings from proplatelet tips were larger in the hGPIbαFW MKs from bone marrow explant cultures than the hGPIbαWT controls (Figure 3D and supplemental Figure 5). MKs with a typical proplatelet morphology have been demonstrated to be plentiful in the lung, whereas proplatelets within the bone marrow are relatively uncommon (<5% of MKs).11 We therefore assessed proplatelet formation within the lungs of mice and found no difference in the number of pulmonary proplatelets in hGPIbαFW mice compared with hGPIbαWT controls (Figure 3E-F). Moreover, there was no apparent difference in the morphology of proplatelets in the lungs of both mouse lines. These findings suggest that the flnA-GPIbα interaction and corresponding alterations in the DMS are dispensable for MK cytoplasmic maturation and proplatelet formation in vitro and in vivo.

Disrupted GPIbα-flnA interaction does not impair megakaryocyte differentiation or proplatelet production in vitro or in the lung in vivo. (A) MK ploidy was determined for WT and FW MKs using PI staining of day-5 cultured MKs and flow cytometry. Results represent the mean ± SEM of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice, (n = 5 and n = 6, respectively); P = .8347 for strain comparison, 2-way ANOVA. (B) MK differentiation was assessed by surface expression of GPIIb-IIIa and GPIb-IX using anti–CD41-PE and anti–CD42a-FITC antibodies, respectively, on day-5 cultured cells using flow cytometry, with results depicting percentage of positively stained vs total cells (mean ± SEM; n = 4 mice). (C) The number of proplatelet bearing MKs at day 4 culture was quantified for hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice. Results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 6-8; P = .87, unpaired t test). (D) The size of individual proplatelet terminal swellings produced by each genotype was quantified using CD42c staining and Zeiss Zen Software and/or Image J. The size represents the maximal transverse length of each proplatelet swelling, with data derived from ∼102 and 65 swellings, 16 and 13 megakaryocytes, from 2 independent hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice, respectively. (E) The lungs of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice were sectioned and subjected to CD41 and laminin immunostaining. Representative 3D confocal images demonstrating pulmonary proplatelets in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice (scale bars, 10 μm). Proplatelets were differentiated from other CD41 stained platelets by their large size, branched morphology and within alveolar septa. (F) The number of proplatelets in 4 × 1170 μm2 lung areas was quantitated and the results represent the mean ± SEM of 3 mice per strain (P = .37, unpaired t test). SEM, standard error of the mean.

Disrupted GPIbα-flnA interaction does not impair megakaryocyte differentiation or proplatelet production in vitro or in the lung in vivo. (A) MK ploidy was determined for WT and FW MKs using PI staining of day-5 cultured MKs and flow cytometry. Results represent the mean ± SEM of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice, (n = 5 and n = 6, respectively); P = .8347 for strain comparison, 2-way ANOVA. (B) MK differentiation was assessed by surface expression of GPIIb-IIIa and GPIb-IX using anti–CD41-PE and anti–CD42a-FITC antibodies, respectively, on day-5 cultured cells using flow cytometry, with results depicting percentage of positively stained vs total cells (mean ± SEM; n = 4 mice). (C) The number of proplatelet bearing MKs at day 4 culture was quantified for hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice. Results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 6-8; P = .87, unpaired t test). (D) The size of individual proplatelet terminal swellings produced by each genotype was quantified using CD42c staining and Zeiss Zen Software and/or Image J. The size represents the maximal transverse length of each proplatelet swelling, with data derived from ∼102 and 65 swellings, 16 and 13 megakaryocytes, from 2 independent hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice, respectively. (E) The lungs of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice were sectioned and subjected to CD41 and laminin immunostaining. Representative 3D confocal images demonstrating pulmonary proplatelets in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice (scale bars, 10 μm). Proplatelets were differentiated from other CD41 stained platelets by their large size, branched morphology and within alveolar septa. (F) The number of proplatelets in 4 × 1170 μm2 lung areas was quantitated and the results represent the mean ± SEM of 3 mice per strain (P = .37, unpaired t test). SEM, standard error of the mean.

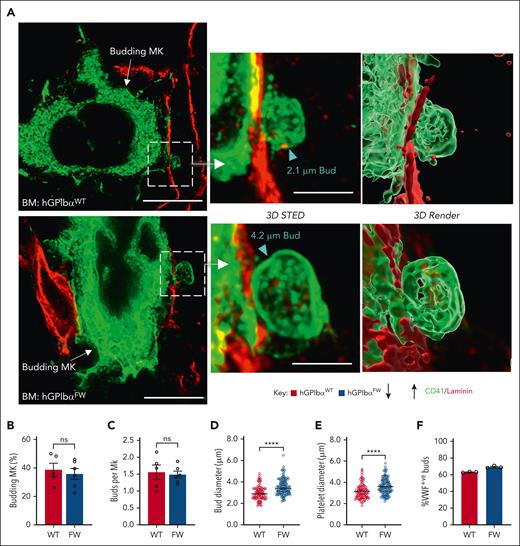

GPIb-flnA interaction regulates megakaryocyte budding

The description of platelet biogenesis by membrane budding provides an additional mechanism of in vivo platelet production and a potential new avenue for mechanistic understanding of abnormal platelet formation. To examine whether the release of platelet-forming buds was dependent on GPIb-flnA interaction, we evaluated the ability of MKs from hGPIbαFW mice to form buds in the native marrow. Using both 3D STED microscopy and confocal optical sectioning through bone marrows of CD41-stained MKs, we assessed the frequency and size of membrane buds, using previously published protocols.10 Buds derived from both hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW MKs were found as extensions of the MK membrane into bone marrow sinusoids (Figure 4A). Moreover, the number of MKs undergoing budding and the number of visible buds per MK were similar between the WT and GPIbα mutant strain (Figure 4B-C). Consistent with the demonstration of larger platelets in circulation, bud sizes were also increased in hGPIbαFW mice (Figure 4D), and the bud size approximated that seen of platelets observed in bone marrow sections (Figure 4E). Analysis of granule content confirmed the presence of VWF in MK buds, with no difference in the proportion of buds expressing VWF between hGPIbαFW and WT mice (Figure 4F). Taken together, these data indicate that the GPIb-flnA interaction and DMS are dispensable for membrane budding from the MK surface, however, the cytoskeletal anchorage of GPIb appears to be important in regulating the size of membrane buds.

GP1bα-flnA interaction does not impair megakaryocyte budding in bone marrow. (A-F) Femoral bone marrow cryosections were immunostained with anti-CD41 (for platelets and MKs), anti-laminin (for sinusoids), and/or anti–P-selectin or anti-VWF (for granule stored content) antibodies and examined with confocal or STED fluorescence microscopy, as described under “Methods.” (A) Representative STED images showing MK budding into sinusoids, with the buds projected in 3D STED and bud size indicated by arrowheads (maximal transverse diameter). Scale bars of 10 μm (2D STED, left panel) and 3 μm (3D STED, right panel) and projected as a surface render using Imaris. (B) Graph showing percentage of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW MKs undergoing budding in 10 μm thick BM cryosections (4 × 50 000 μm2 fields per mouse were examined). (C) Number of buds per MK was determined for budding hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW MKs. Bud size (D) and sinusoidal platelet size (E) was determined using maximal transverse diameter on optical sections. A total of 35 to 40 MKs and platelets were assessed per mouse. Graphs represent mean ± SEM (n = 5-6 mice; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001). (F) The VWF containing buds in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice were determined by immunostaining of bone marrow cryosections with anti-CD41 and anti-VWF Abs and confocal microscopy. The results are percentage of VWF+ buds over total buds examined (>20 CD41+ surface projections from each of n = 3 mice were examined). Ab, antibody; BM, bone marrow; SEM, standard error of the mean.

GP1bα-flnA interaction does not impair megakaryocyte budding in bone marrow. (A-F) Femoral bone marrow cryosections were immunostained with anti-CD41 (for platelets and MKs), anti-laminin (for sinusoids), and/or anti–P-selectin or anti-VWF (for granule stored content) antibodies and examined with confocal or STED fluorescence microscopy, as described under “Methods.” (A) Representative STED images showing MK budding into sinusoids, with the buds projected in 3D STED and bud size indicated by arrowheads (maximal transverse diameter). Scale bars of 10 μm (2D STED, left panel) and 3 μm (3D STED, right panel) and projected as a surface render using Imaris. (B) Graph showing percentage of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW MKs undergoing budding in 10 μm thick BM cryosections (4 × 50 000 μm2 fields per mouse were examined). (C) Number of buds per MK was determined for budding hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW MKs. Bud size (D) and sinusoidal platelet size (E) was determined using maximal transverse diameter on optical sections. A total of 35 to 40 MKs and platelets were assessed per mouse. Graphs represent mean ± SEM (n = 5-6 mice; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001). (F) The VWF containing buds in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice were determined by immunostaining of bone marrow cryosections with anti-CD41 and anti-VWF Abs and confocal microscopy. The results are percentage of VWF+ buds over total buds examined (>20 CD41+ surface projections from each of n = 3 mice were examined). Ab, antibody; BM, bone marrow; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Misdirected platelet biogenesis in hGPIbαFW mice

Budding MKs typically release platelets in a polarized fashion directly into the sinusoidal space.11 However, we observed prominent bud-like structures in the interstitial compartment of the bone marrow of hGPIbαFW mice (herein referred to as interstitial buds), with limited numbers of bud-sized membrane structures in the bone marrow sinusoids (Figure 5A). Despite a similar number of bud-like structures visible within an individual region of bone marrow (Figure 5B), we found an approximately twofold increase in the number of buds within the interstitial compartment of hGPIbαFW mice (Figure 5C). To confirm that these interstitial buds were indeed likely to represent platelet precursors, rather than previously described MK-derived blebs or microvesicles,12 we assessed interstitial buds for the presence of platelet-specific granule contents. 2D superresolution microscopy demonstrated interstitial buds express membrane CD41 with clusters of P-selectin and VWF distributed heterogeneously throughout the bud cytoplasm (Figure 5D-E). Quantitatively, 66% of buds in hGPIbαFW bone marrow were found in the interstitial compartment, whereas the majority of buds in hGPIbαWT mice were located intravascularly. This dysregulated bud release coincided with aberrant localization of megakaryocytes away from the vascular sinusoids, suggesting that the interstitial release of buds from megakaryocytes may contribute to the low circulating platelet count in hGPIbαFW mice (Figure 5F-G and supplemental Figure 6A).

Disrupting GP1bα-flnA interaction results in aberrant megakaryocyte budding in bone marrow. Bone marrows isolated from hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice were immunostained with antibodies against CD41 (green, for platelets and megakaryocytes), laminin (red, for vessels), P-selectin, or VWF (magenta), in addition to a nuclear stain (Hoechst 33342 [blue]), as indicated. (A) Representative confocal images showing intravascular and interstitial platelets/buds (arrowheads) in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW bone marrows, at low and high magnifications (63×; scale bar, 50 μm; inset scale bar, 20 μm). (B-C) Quantification of the total number of CD41+ buds (interstitial and intravascular) (B) and interstitial buds (C) per 370 μm2 field, generated from tile scans in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice. Graphs represent the mean ± SEM of 3 mice; ∗∗P < .01. (D) Representative STED image showing a granular VWF-containing interstitial bud in hGPIbαFW bone marrow interstitium (93×; scale bar, 10 μm; inset scale bar, 3 μm). (E) Representative confocal and Airyscan (inset) image showing a granular P-selective containing interstitial bud in hGPIbαFW bone marrow (63×; scale bar, 30 μm; inset scale bar, 5 μm). (F-G) Bone marrow MK sinusoidal localization was analyzed in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice. (F) Tiled confocal images showing MK sinusoidal and interstitial localization in bone marrows of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice; scale bars, 50 μm; inset scale bar, 20 μm. (G) Quantification of the percentage (%) megakaryocytes with sinusoidal contacts (SC) or without contact (BMHC) or within sinusoids (intrasinusoidal). Results depict the mean ± SEM; n = 3 mice, with at least 50 megakaryocytes analyzed per mouse; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. ANOVA, analysis of variance; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Disrupting GP1bα-flnA interaction results in aberrant megakaryocyte budding in bone marrow. Bone marrows isolated from hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice were immunostained with antibodies against CD41 (green, for platelets and megakaryocytes), laminin (red, for vessels), P-selectin, or VWF (magenta), in addition to a nuclear stain (Hoechst 33342 [blue]), as indicated. (A) Representative confocal images showing intravascular and interstitial platelets/buds (arrowheads) in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW bone marrows, at low and high magnifications (63×; scale bar, 50 μm; inset scale bar, 20 μm). (B-C) Quantification of the total number of CD41+ buds (interstitial and intravascular) (B) and interstitial buds (C) per 370 μm2 field, generated from tile scans in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice. Graphs represent the mean ± SEM of 3 mice; ∗∗P < .01. (D) Representative STED image showing a granular VWF-containing interstitial bud in hGPIbαFW bone marrow interstitium (93×; scale bar, 10 μm; inset scale bar, 3 μm). (E) Representative confocal and Airyscan (inset) image showing a granular P-selective containing interstitial bud in hGPIbαFW bone marrow (63×; scale bar, 30 μm; inset scale bar, 5 μm). (F-G) Bone marrow MK sinusoidal localization was analyzed in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice. (F) Tiled confocal images showing MK sinusoidal and interstitial localization in bone marrows of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice; scale bars, 50 μm; inset scale bar, 20 μm. (G) Quantification of the percentage (%) megakaryocytes with sinusoidal contacts (SC) or without contact (BMHC) or within sinusoids (intrasinusoidal). Results depict the mean ± SEM; n = 3 mice, with at least 50 megakaryocytes analyzed per mouse; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. ANOVA, analysis of variance; SEM, standard error of the mean.

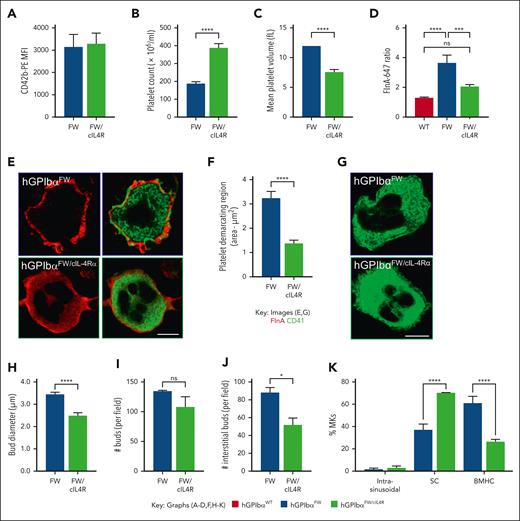

GPIbα cytoplasmic tail expression restores flnA distribution and bud release

The insertion of a cIL-4Rα into BSS mice is known to reverse the macrothrombocytopenia seen in GPIbα KO.14 The cIL-4Rα fusion protein possesses a transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic tail of GPIbα, fused to an extracellular domain of the cIL-4Rα, providing an anchorage site for the membrane skeleton through an independent GPIbα tail. To provide further evidence that the size of buds and location of buds within the bone marrow is regulated by the GPIbα-flnA interaction, we crossed cIL-4Rα mice with hGPIbαFW mice to produce hGPIbαFW mice, which also coexpressed the cIL-4Rα. The expression of the cIL-4Rα construct in hGPIbαFW mice did not alter GPIbα levels on the surface of platelets (Figure 6A). However, it did ameliorate the macrothrombocytopenia (Figure 6B-C), albeit to a slightly lower level than that seen in hGPIbαWT controls. When the flnA distribution was evaluated in bone marrow megakaryocytes, we found that although FW mice showed a threefold increase in the peripheral flnA intensity, cIL-4Rα mice showed normalization of the flnA fluorescence intensity (Figure 6D) and homogenous flnA distribution through the cytoplasm (Figure 6E). Moreover, the CD41 staining of DMS membranes revealed a normalization of internal membrane structure (Figure 6F-G). This improvement in MK ultrastructure was associated with normal bud size (Figure 6H) and numbers within the bone marrow (Figure 6I and supplemental Figure 6B) and a reduction in the proportion of buds within the bone marrow interstitium (Figure 6J). This redistribution of interstitial buds correlated with changes in MK localization toward bone marrow sinusoids, with a similar proportion of interstitial and sinusoidal MKs as hGPIbαWT controls (Figure 6K). These studies confirm an important role of the cytoplasmic tail of GPIbα in regulating budding morphogenesis. They also suggest a major role of the cytoskeletal anchorage of GPIbα in regulating the localization of MKs within the bone marrow and the corresponding spatial release of buds.

Expression of cIL-4Rα ameliorates macrothrombocytopenia. (A) Anticoagulated whole blood from and hGPIbαFW and hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα mice was assessed for platelet GPIbα surface expression by flow cytometry using anti-CD42b Ab-PE. The results are the mean fluorescence intensity of gated platelet population (mean ± SEM of n = 10 pairs hGPIbαFW and hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα mice). (B-C) Platelet count (B) and mean platelet volume (C) were analyzed using EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood from hGPIbαFW and hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα mice on a Sysmex blood analyzer. Graphs show mean ± SEM of 20 and 13 mice, respectively; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (D-E) The effect of ILR4 expression on flnA distribution was evaluated in hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα bone marrow megakaryocytes using confocal microscopy. (D) Fluorescence intensity ratios of peripheral relative to the cytoplasmic flnA (5 random 1 μm2 regions from the central and peripheral regions of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW megakaryocytes, as depicted in supplemental Figure 4); ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, ∗∗∗P < .001, 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. At least 10 megakaryocytes were analyzed from each of 4 hGPIbαFW and 3 hGPIbαFW/cIL-4R mice. (E) Representative confocal images of hGPIbαFW and hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα bone marrow megakaryocytes showing homogenous flnA and organized CD41 distribution throughout the cytoplasm in hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα mice, in contrast to periphery flnA and disorganized CD41 in hGPIbαFW (93× glycerol objective; scale bar, 10 μm). (F-G) The DMS of hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα mice was analyzed after staining of femoral cryosections with anti-CD41 Ab and STED imaging. (F) Quantitation of the area of platelet demarcating territories within the cytoplasm of at least 5 megakaryocytes from each of 3 pairs of mice; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 (G) Representative STED image demonstrating well-organized DMS in hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα bone marrow megakaryocytes, relative to hGPIbαFW cells (93× glycerol objective; scale bar, 10 μm). (H-K) Quantitation of bud diameter (performed as described under Methods, H), total CD41+ buds (I), interstitial buds (J) and MK location (intrasinusoidal), sinusoidal contact (SC), or bone marrow hematopoietic compartment (BMHC) (K) per 370 μm2 field generated from tile scans in hGPIbαFW and hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα. Graphs show the mean ± SEM of 3 mice; ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, unpaired 2-tailed t test or 2-way ANOVA as appropriate. Ab, antibody; ANOVA, analysis of variance; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Expression of cIL-4Rα ameliorates macrothrombocytopenia. (A) Anticoagulated whole blood from and hGPIbαFW and hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα mice was assessed for platelet GPIbα surface expression by flow cytometry using anti-CD42b Ab-PE. The results are the mean fluorescence intensity of gated platelet population (mean ± SEM of n = 10 pairs hGPIbαFW and hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα mice). (B-C) Platelet count (B) and mean platelet volume (C) were analyzed using EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood from hGPIbαFW and hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα mice on a Sysmex blood analyzer. Graphs show mean ± SEM of 20 and 13 mice, respectively; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (D-E) The effect of ILR4 expression on flnA distribution was evaluated in hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα bone marrow megakaryocytes using confocal microscopy. (D) Fluorescence intensity ratios of peripheral relative to the cytoplasmic flnA (5 random 1 μm2 regions from the central and peripheral regions of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW megakaryocytes, as depicted in supplemental Figure 4); ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, ∗∗∗P < .001, 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. At least 10 megakaryocytes were analyzed from each of 4 hGPIbαFW and 3 hGPIbαFW/cIL-4R mice. (E) Representative confocal images of hGPIbαFW and hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα bone marrow megakaryocytes showing homogenous flnA and organized CD41 distribution throughout the cytoplasm in hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα mice, in contrast to periphery flnA and disorganized CD41 in hGPIbαFW (93× glycerol objective; scale bar, 10 μm). (F-G) The DMS of hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα mice was analyzed after staining of femoral cryosections with anti-CD41 Ab and STED imaging. (F) Quantitation of the area of platelet demarcating territories within the cytoplasm of at least 5 megakaryocytes from each of 3 pairs of mice; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 (G) Representative STED image demonstrating well-organized DMS in hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα bone marrow megakaryocytes, relative to hGPIbαFW cells (93× glycerol objective; scale bar, 10 μm). (H-K) Quantitation of bud diameter (performed as described under Methods, H), total CD41+ buds (I), interstitial buds (J) and MK location (intrasinusoidal), sinusoidal contact (SC), or bone marrow hematopoietic compartment (BMHC) (K) per 370 μm2 field generated from tile scans in hGPIbαFW and hGPIbαFW/cIL-4Rα. Graphs show the mean ± SEM of 3 mice; ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, unpaired 2-tailed t test or 2-way ANOVA as appropriate. Ab, antibody; ANOVA, analysis of variance; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Discussion

Platelet production by MKs in vivo has been long thought to be exclusively mediated by proplatelets. Historically, 2 models have been proposed to explain steady-state platelet formation; platelets released from proplatelet tips that extend from bone marrow MKs into blood vessels, or alternatively, via the fragmentation of MKs into platelets in the pulmonary microcirculation.34 A third model of platelet biogenesis has been recently proposed, involving the budding of platelet-like structures from the surface of MKs into bone marrow sinusoids.11 Our studies, which have used a new mouse model of macrothrombocytopenia, involving the defective binding of human GPIbα to flnA, have demonstrated normal MK numbers in the bone marrow and, unexpectedly, no major defects in the proplatelet formation in vivo. The principal defect in the platelet production in hGPIbαFW mice appeared to be related to the dysregulated MK budding. In particular, the aberrant generation of enlarged buds represents a previously undescribed mechanism of giant platelet formation. Moreover, dysregulated MK localization in the bone marrow, away from vascular sinusoids, led to ectopic release of membrane buds into the bone marrow interstitium, providing a plausible mechanistic explanation for the thrombocytopenia observed in these mice.

We and others have previously demonstrated that deletion of flnA or its interaction with GPIbα result in fragile platelets under high shear conditions, which may undergo physical fragmentation and microvesiculation in the circulation.15,25 We had anticipated that thrombocytopenia and the reduced levels of GPIb surface expression in hGPIbαFW mice may reflect unstable platelet membranes and accelerated peripheral platelet clearance. Surprisingly, we found no evidence of increased platelet clearance in hGPIbαFW mice, suggesting that the primary cause of thrombocytopenia is due to defective platelet production. Our findings in the hGPIbαFW mice indicate that disrupting flnA binding to GPIbα does not prevent proplatelet formation in vitro, nor did we see reduction in the frequency of pulmonary proplatelets in vivo. These in vivo findings are consistent with previous in vitro studies on an isogenic stem cell model of megakaryopoiesis, in which the expression of mutant forms of flnA that have a selective defect in GPIbα binding, exhibits normal proplatelet formation.17

Our studies have demonstrated that disrupting the linkage between flnA and GPIbα had a major impact on flnA distribution in the MK cytoplasm, resulting in a striking impairment in DMS formation. The DMS is primarily considered the main source of internal membrane reserves necessary for proplatelet formation. Our studies in hGPIbαFW mice demonstrate that MK membrane budding per se is not dependent on a well-organized DMS. However, the impaired development of the platelet-forming territories in the demarcating membrane system of MKs appears to be linked to the dysregulated bud sizes in hGPIbαFW mice. Similar to previous reports on flnA-null36 MKs, dysregulated flnA localization was associated with a lack of peripheral zone in hGPIbαFW bone marrow MKs. Whether flnA redistribution directly or indirectly affects the peripheral zone and whether this is also linked to aberrant budding remains to be established.

FlnA can bind to up to 100 different proteins and is anchored to the membrane cytoskeleton through its interactions with integrins37,38 and ion channel proteins39,40 in most mammalian cells.41 GPIbα is primarily expressed in platelets and MKs, and our studies highlight the critical importance of GPIbα in regulating flnA subcellular distribution in the latter cells. The aberrant flnA redistribution observed in hGPIbαFW bone marrow MKs was corrected by the coexpression of the GPIbα tail in cIL-4Rα–hGPIbαFW bone marrow MKs, confirming the critical role of the physical linkage between GPIbα cytoplasmic tail and flnA in regulating flnA subcellular distribution. Redistribution of flnA has been previously noted in platelets and HEK293T cells,42,43 and it is believed to be influenced by the ratio of flnA and GPIbα expression in a reciprocal manner, with an imbalanced ratio impacting platelet size and production. These studies have demonstrated that reciprocal expression of flnA and GPIbα at an optimal ratio is important to prevent protein sequestration in the endoplasmic reticulum and for the generation of normal sized platelets. Our studies here have revealed that rather than endoplasmic reticulum sequestration, in the absence of its GPIbα binding, flnA becomes enriched in the MK periphery. FlnA binds to and regulates the filamentous actin network; however, in MKs, we could find no evidence that flnA redistribution in hGPIbαFW mice was associated with gross alterations in the F-actin network. Previous investigations of filaminopathies causing macrothrombocytopenia lead to the identification of a patient with a flnA mutation that incorporated the GPIbα binding site.36 Notably, this individual had preserved interaction between flnA and F-actin, however, it is unclear whether this filamin mutation fully disrupted the link between flnA and GPIb. F-actin at the periphery of MKs is tightly coordinated and assembled into podosome-like structures that facilitate the docking of MKs to sinusoids.44 Whether the peripheral enrichment of flnA in hGPIbαFW mice leads to aberrant F-actin assembly and abnormal podosome formation remains to be explored.

Our findings demonstrate an important role of the GPIb-flnA interaction in regulating the morphogenesis of MK-derived membrane buds. At the molecular level, flnA plays a major role in regulating the mechanical stability of cell membranes in numerous cell types.45 FlnA is a prominent actin filament cross-linking protein,46 present in the cortex of numerous cells types,47-50 and facilitates the link between the actin cytoskeleton and plasma membrane. The importance of flnA in regulating the delamination of the plasma membrane from the cortical cytoskeleton was first recognized in flnA-deficient human melanoma cells, leading to blebbing of plasma membrane.51 Although our findings demonstrate that the physical link between GPIbα and flnA plays a major role in regulating the internal membrane organization of the DMS, it remains to be seen how important this interaction is in regulating the stability of the membranes within the DMS and MK plasma membrane and how important these additional membrane changes may be to altered bud morphogenesis.

Our studies on the hGPIbαFW mice have revealed the presence of large numbers of bud-like structures within the interstitial regions of the bone marrow. Ectopic release of platelets into the bone marrow interstitial space, presumed by aberrant proplatelets, has previously been proposed as a potential cause of microthrombocytopenia.52-56 Our studies demonstrate an alternative explanation for ectopic platelet release through the production of buds by MKs within the bone marrow interstitium. Abnormal MK localization has been identified in the context of GPIbα-/- mice,8 and our preliminary studies on GPIbα–/– mice have confirmed aberrant budding in the interstitial compartment ( M.E., Y.Y., and S.P.J., written communication 22 September 2023), suggesting a mechanistic link between ectopic MKs and interstitial, extravascular bud-like structures. Based on the quantitative estimates of Potts et al,11 89% of circulating platelets in mice are derived from MK buds. Therefore, the 45% reduction in the number of buds localized to bone marrow sinusoids in hGPIbαFW mice is likely to contribute substantially to the overall 60% reduction in the circulating platelet counts. The mechanisms leading to impaired sinusoidal engagement of MKs from hGPIbαFW mice is currently unclear, however, it does not seem related to GPIb expression or ligand binding. This is based on our observations that the coexpression of cIL-4Rα in hGPIbαFW mice restored the MK sinusoidal attachment and that high GPIbα-expressing hGPIbαFW mice do not display improved platelet count relative to lower expressors. This impairment is possibly intrinsic to the observed redistribution of flnA and consequent changes to the cytoskeleton required for megakaryocyte docking to sinusoids. It has been observed that a high flnA concentration is associated with tighter F-actin bundles that are stiffer under biomechanical force,57 whereas lower flnA concentration is linked to more dynamic and softer F-actin.58 Furthermore, a temporal dissolution of the peripheral zone has been observed during proplatelet release from MKs in the bone marrow.59 Because hGPIbαFW MKs also lack peripheral zones, it is plausible that this may also lead to aberrant bud release.

Evaluation of in vivo bone marrow MKs, particularly with respect to the evaluation of cytoskeletal structures at single-molecule resolution, is an important avenue for future investigation. However, this is technically difficult to achieve with respect to membrane buds. Sectioning tissue thinly enough to conduct superresolution microscopy, while simultaneously evaluating MKs buds in 3D, is a major experimental challenge. Although focussed ion beam-scanning electron micrsocopy (FIB-SEM) has been used to evaluate MKs previously,60 a multicolor 3D correlative light-electron microscopy (CLEM)-based approach is likely to be required to provide sufficient spatial resolution to identify subtle alterations in the membrane and cytoskeletal structures associated with DMS and bud formation. Combining genetic mouse models of macrothrombocytopenia with advances in single-molecule imaging should provide important new insights into the molecular mechanisms regulating bud morphogenesis and platelet generation.

Our demonstration that the GPIbα cytoskeletal interaction is a critical determinant for regulating the size and localized release of buds into the bone marrow sinusoids provides important new insights into the causes of macrothrombocytopenia. Whether dysregulating MK budding is responsible for other causes of macrothrombocytopenia remains to be seen. Nonetheless, these new insights may open new avenues to modulate platelet biogenesis and ameliorate platelet production defects in vivo.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical and scientific assistance of Sydney Microscopy & Microanalysis, the University of Sydney node of Microscopy Australia, in particular, the assistance provided by Neftali Flores Rodriguez.

This work was supported by the Kanematsu Research Award (Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia) (M.L.E.) and New South Wales Health (NSW, Australia) Cardiovascular Capacity Building Grants (S.P.J.); and supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Investigator Grant (Leadership 3, No.1176016; S.P.J.).

Authorship

Contribution: M.L.E. performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote and revised the manuscript; A.T., I.A., R.S., J.P., A.E., and J.M. performed experiments and assisted with data interpretation; S.L.C. generated mice, performed experiments, and analyzed data; F.H.P, Z.M.R., and F.L provided intellectual contributions and reviewed the manuscript; S.M.S. provided intellectual contributions, reviewed/revised the manuscript, and assisted with the preparation of figures; S.T. assisted with planning experiments and data interpretation; and Y.Y. and S.P.J. wrote and revised the manuscript, interpreted data, and provided academic oversight of the project.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Shaun P. Jackson, Heart Research Institute, and Charles Perkins Centre, The University of Sydney, Level 3, D17, Camperdown, NSW, 2006, Australia; email: shaun.jackson@hri.org.au.

References

Author notes

Original data are available upon request from the corresponding author, Shaun Jackson (shaun.jackson@hri.org.au).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![Disrupting GP1bα-flnA interaction results in aberrant megakaryocyte budding in bone marrow. Bone marrows isolated from hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice were immunostained with antibodies against CD41 (green, for platelets and megakaryocytes), laminin (red, for vessels), P-selectin, or VWF (magenta), in addition to a nuclear stain (Hoechst 33342 [blue]), as indicated. (A) Representative confocal images showing intravascular and interstitial platelets/buds (arrowheads) in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW bone marrows, at low and high magnifications (63×; scale bar, 50 μm; inset scale bar, 20 μm). (B-C) Quantification of the total number of CD41+ buds (interstitial and intravascular) (B) and interstitial buds (C) per 370 μm2 field, generated from tile scans in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice. Graphs represent the mean ± SEM of 3 mice; ∗∗P < .01. (D) Representative STED image showing a granular VWF-containing interstitial bud in hGPIbαFW bone marrow interstitium (93×; scale bar, 10 μm; inset scale bar, 3 μm). (E) Representative confocal and Airyscan (inset) image showing a granular P-selective containing interstitial bud in hGPIbαFW bone marrow (63×; scale bar, 30 μm; inset scale bar, 5 μm). (F-G) Bone marrow MK sinusoidal localization was analyzed in hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice. (F) Tiled confocal images showing MK sinusoidal and interstitial localization in bone marrows of hGPIbαWT and hGPIbαFW mice; scale bars, 50 μm; inset scale bar, 20 μm. (G) Quantification of the percentage (%) megakaryocytes with sinusoidal contacts (SC) or without contact (BMHC) or within sinusoids (intrasinusoidal). Results depict the mean ± SEM; n = 3 mice, with at least 50 megakaryocytes analyzed per mouse; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. ANOVA, analysis of variance; SEM, standard error of the mean.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/143/4/10.1182_blood.2023021292/1/m_blood_bld-2023-021292-gr5.jpeg?Expires=1770543963&Signature=w19DMmS8OGedHrF9XVHPPx06oWnqftz19Pi424-S77TFuuEmQVKbXyOb1Rd7yvqKdK8P2obvs6k7PEsJcrqM~bJYm6CvK2NSZGbgDUXIdqolaNB~zcIQAXIS-nyAYVE9Ht36qbFw8WGK-KNF0spCPjNlOXJDzNDiux1COf1sN2jmyUGfnCyzIN6cCfOSx4W7-6HfS89JG2xUFGrGf-zRCPgqkQVnZRGRuL5ZpTZjb30VRM6VA2omn6N1AcJh1S5N-tOs81NOTVPMgMyp1kAtybjy4WmhgyQME2U2jGcuhtpGm22~CvXFXPUYck78TygqIY6MAc8c36wxOSqaV5~6Cw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal