Gain-of-function PIEZO1 enhances PS exposure in HX RBCs through its functional coupling to TMEM16F lipid scramblase.

Benzbromarone blocks PIEZO1 and decouples PIEZO1-TMEM16F, preventing PS exposure, echinocytosis, and hemolysis in HX RBCs.

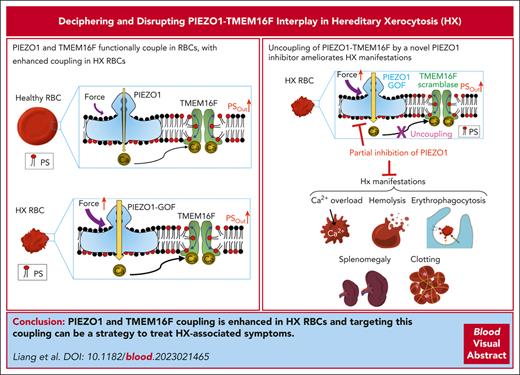

Visual Abstract

Cell-surface exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) is essential for phagocytic clearance and blood clotting. Although a calcium-activated phospholipid scramblase (CaPLSase) has long been proposed to mediate PS exposure in red blood cells (RBCs), its identity, activation mechanism, and role in RBC biology and disease remain elusive. Here, we demonstrate that TMEM16F, the long-sought-after RBC CaPLSase, is activated by calcium influx through the mechanosensitive channel PIEZO1 in RBCs. PIEZO1-TMEM16F functional coupling is enhanced in RBCs from individuals with hereditary xerocytosis (HX), an RBC disorder caused by PIEZO1 gain-of-function channelopathy. Enhanced PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling leads to an increased propensity to expose PS, which may serve as a key risk factor for HX clinical manifestations including anemia, splenomegaly, and postsplenectomy thrombosis. Spider toxin GsMTx-4 and antigout medication benzbromarone inhibit PIEZO1, preventing force-induced echinocytosis, hemolysis, and PS exposure in HX RBCs. Our study thus reveals an activation mechanism of TMEM16F CaPLSase and its pathophysiological function in HX, providing insights into potential treatment.

Introduction

Cell-surface exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS), an anionic phospholipid that is usually confined to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, triggers a plethora of cellular responses.1-4 On the cell surface, negatively charged PS acts as an “eat-me” signal to facilitate phagocytosis,5-7 a procoagulation signal to enable the assembly of procoagulation complexes,2,8 and a “fuse-me” signal to assist cell-cell and virus-cell fusion.9-14 However, the specific phospholipid transporters that regulate PS exposure in diverse cell types are not well-defined, hampering our understanding of its roles in health and disease, including conditions, such as thrombosis, cancer, and infectious diseases.

PS-exposing red blood cells (RBCs) contribute to blood coagulation, promote RBC aggregation and adhesion to endothelial cells, and accelerate the removal of aging RBCs from circulation.15-22 The existence of calcium-activated phospholipid scramblase (CaPLSases), passive phospholipid transporters that catalyzes rapid PS exposure in response to intracellular Ca2+ elevation,23 was first observed in RBCs in studies conducted in the 1990s.24-26 However, the molecular identity of RBC CaPLSase remain elusive. Mounting evidence has supported that members from the TMEM16 transmembrane protein family, particularly TMEM16F, are CaPLSases.23,27-31 Loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in TMEM16F lead to Scott syndrome, a bleeding disorder.23,27,32 Deficiency in TMEM16F results in diminished Ca2+–induced PS exposure in platelets23,27,28 and RBCs.27 Despite these advances, it is not clear whether TMEM16F is the sole RBC CaPLSase, or how its dysregulation might contribute to red cell disorders.

CaPLSase activation requires intracellular Ca2+.23,27 Because RBCs lack internal Ca2+ stores, it is conceivable that the activation of RBC CaPLSases depends on Ca2+-influx through RBC Ca2+ channels. We focused on the PIEZO1 mechanosensitive channel, which mediates Ca2+ entry in RBCs in response to mechanical stimulation33 and contributes to RBC dehydration in hereditary xerocytosis (HX) or dehydrated hereditary stomatocytosis, a rare genetic hemolytic anemia that affect 1 in 8000 adults.34-47 Because RBCs play an important role in thrombosis, and PS exposure is critical for blood coagulation, we examined the connection between PIEZO1–mediated Ca2+ entry and Ca2+–activated PS exposure in healthy and HX RBCs.

Here, we identified TMEM16F as the primary CaPLSase in both human and murine RBCs, activated by PIEZO1-mediated Ca2+ influx. We discovered that HX RBCs exhibit increased PS exposure because of amplified coupling between TMEM16F and disease causing PIEZO1 gain-of-function (GOF) mutations. Furthermore, we found that benzbromarone, a common gout medication, acts as a PIEZO1 channel blocker. Partial inhibition of PIEZO1 with benzbromarone and spider toxin GsMTx-4 effectively hampers the PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling, thereby preventing PS exposure. Our research establishes the molecular identity of RBC CaPLSase, uncovers a mechanosensitive activation mechanism for the CaPLSase, identifies a potential pathological mechanism in HX, and sheds light on a potential therapeutic approach for treating this condition.

Methods

Human subjects

HX001 and HX002 patients were referred with suspected HX, followed by next-generation sequencing. Both patients were healthy with baseline normal blood counts, however, had evidence of compensated hemolysis as indicated by elevated reticulocyte count and increased total bilirubin. The sequencing results showed that HX001 carries PIEZO1 p.Arg2488Gln (c.7463G>A) mutation in heterozygous state. HX002 patient carries PIEZO1 p.Leu2495_Glu2496dup (c.7483_7488dup) mutation, also known as p.E2496ELE. A polymerase chain reaction–based Sanger sequencing method (Azenta Life Sciences) was used to further validate the results of the next-generation sequencing and to determine the heredity of the HX001 family.

All human studies were approved by the institutional review board at Duke University (IRB# Pro00109511). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients with HX and healthy donors (HDs).

Mice

Mouse handling and usage were carried out in strict compliance with the protocol approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at Duke University, in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. TMEM16F knockout (KO) and Piezo1-R2482H knock-in mice were genotyped following the same procedure as our previous reports.13,27,48

Flow cytometry

RBCs were centrifuged at 100g for 12 minutes. After the supernatant was aspirated, the RBC pellets were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline to get packed RBCs. Packed RBCs were diluted 1:20 with Hanks balanced salt solution, 3 μL of which were added into 200 μL Hanks balanced salt solution containing CF488 annexin V (AnV, 1:125). Designed concentrations of Yoda1 were then added and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature. The samples were measured using BD FASCanto flow cytometers (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Briefly, RBCs were selected by gating on forward or side-light scatters. Excitation of RBCs was performed at 488 nm, and emission was detected using a filter of 530 nm. Results were shown as percentage of AnV positive RBCs or as mean fluorescence intensity of AnV staining. For drug test, RBCs were premixed with drugs of interest, followed by Yoda1 addition to the mixed solution and incubation for 10 minutes at room temperature. The results were analyzed with FCS Express software (De Novo, Pasadena, CA).

Fluorescence imaging

Electrophysiology

All ionic currents were recorded in cell-attach, outside-out, or whole-cell configurations as indicated using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices) and the pClamp software package (Molecular Devices). Detailed methods are in the supplemental Methods.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with Clampfit 10 (Molecular Devices), Excel, or Prism software (GraphPad). Two-tailed Student t test was used for single comparisons between 2 groups (paired or unpaired), and 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey test was used for multiple comparisons. Data were represented as mean ± standard error of the mean, unless stated otherwise.

Other methods are described in the supplemental Methods.

Results

TMEM16F encodes RBC CaPLSase

To pinpoint the molecular identity of the RBC CaPLSase without interference from other PS exposure mechanisms, such as caspase-dependent scramblases, flippase inhibition, membrane damage, or cell lysis,2,3,50 we used quantitative single-cell approaches that allow real-time monitoring of PS exposure. We first adapted our fluorescence imaging assay to quantify Ca2+ ionophore–induced PS exposure in RBCs using confocal microscopy,13,49,51 in which the cell-surface accumulation of fluorescence AnV reports CaPLSase–mediated PS exposure (Figure 1A). Consistent with previous reports, 10 μM ionomycin triggered Ca2+ increase and subsequent PS exposure in a small population of murine RBCs (Figure 1B).27,52 The RBCs from TMEM16F KO mice showed similar Ca2+ increase and morphological transitions upon ionomycin stimulation (Figure 1C). However, the TMEM16F-deficient RBCs did not show Ca2+–activated PS exposure (Figure 1C-D), consistent with the observations in the RBCs from patients with Scott syndrome who carry LOF of TMEM16F mutations.26

TMEM16F is responsible for Ca2+–activated lipid scrambling in murine RBCs. (A) Schematic of the fluorescence lipid scrambling assay in RBCs. (B-C) Ca2+ (red)–induced phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure (AnV, green) in the RBCs from TMEM16F wild-type (WT; B) and TMEM16F knockout (KO; C) mice. Ten micromolar ionomycin was used to trigger Ca2+ influx and subsequent lipid scrambling. White boxes show an enlarged view. (D) Time-dependent lipid scrambling reported by AnV in the TMEM16F WT and KO murine RBCs induced by ionomycin. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). WT (n = 16 cells) and KO (n = 15 cells) from at least 3 biological replicates. (E) Schematic of PCLSF assay to simultaneously monitor TMEM16F lipid scramblase and ion channels activities (see “Methods” for details). (F) Representative images of lipid scrambling activity in WT and TMEM16F-KO RBCs under PCLSF. PS exposure was detected by membrane binding of the fluorescent AnV conjugates. (G) Representative current traces in WT and TMEM16F-KO RBCs elicited by a voltage step protocol from –100 mV to +160 mV with 20 mV increment. The currents were recorded ∼2.5 minutes after the whole-cell patches were established. (H) Representative time course of AnV signal on WT and TMEM16F-KO RBCs. (I) Fluorescence intensity of AnV signal at 3 minutes. Two-sided Student t test, ∗∗∗P < .001 (n = 5). (J) I-V relationship of the currents recorded in (G). The currents were normalized to cell capacitance. The results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). (K) Current density at +160 mV. The results are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-sided Student t test, ∗∗∗P < .001 (n = 6).

TMEM16F is responsible for Ca2+–activated lipid scrambling in murine RBCs. (A) Schematic of the fluorescence lipid scrambling assay in RBCs. (B-C) Ca2+ (red)–induced phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure (AnV, green) in the RBCs from TMEM16F wild-type (WT; B) and TMEM16F knockout (KO; C) mice. Ten micromolar ionomycin was used to trigger Ca2+ influx and subsequent lipid scrambling. White boxes show an enlarged view. (D) Time-dependent lipid scrambling reported by AnV in the TMEM16F WT and KO murine RBCs induced by ionomycin. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). WT (n = 16 cells) and KO (n = 15 cells) from at least 3 biological replicates. (E) Schematic of PCLSF assay to simultaneously monitor TMEM16F lipid scramblase and ion channels activities (see “Methods” for details). (F) Representative images of lipid scrambling activity in WT and TMEM16F-KO RBCs under PCLSF. PS exposure was detected by membrane binding of the fluorescent AnV conjugates. (G) Representative current traces in WT and TMEM16F-KO RBCs elicited by a voltage step protocol from –100 mV to +160 mV with 20 mV increment. The currents were recorded ∼2.5 minutes after the whole-cell patches were established. (H) Representative time course of AnV signal on WT and TMEM16F-KO RBCs. (I) Fluorescence intensity of AnV signal at 3 minutes. Two-sided Student t test, ∗∗∗P < .001 (n = 5). (J) I-V relationship of the currents recorded in (G). The currents were normalized to cell capacitance. The results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). (K) Current density at +160 mV. The results are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-sided Student t test, ∗∗∗P < .001 (n = 6).

To further confirm TMEM16F as the CaPLSase in RBCs, we used its moonlighting function as a Ca2+-activated nonselective ion channel27,31 and applied the patch-clamp lipid scrambling fluorometry (PCLSF) technique31,51 to quantify Ca2+–induced ion channel and lipid-scrambling activities in RBCs simultaneously at the single-cell level (Figure 1E). A Cs+-based solution was used in this experiment to prevent the interference from the Ca2+-activated Gardos K+ channel in RBCs. We observed robust Ca2+-induced PS exposure in TMEM16F wild-type (WT) but not KO RBCs (Figure 1F,H,I). Concomitantly, a time- and voltage-dependent, outward-rectifying current was recorded in WT RBCs (Figure 1G), which resembled the kinetics of TMEM16F current in different cell types.27,31,51 In contrast, the time-dependent and Ca2+-activated current diminished in TMEM16F KO RBCs (Figure 1G,J,K). In addition to murine RBCs, we also recorded the same Ca2+- and voltage-activated, time-dependent current in human RBCs, suggesting that human RBCs also functionally express TMEM16F (supplemental Figure 1).

PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling leads to PS exposure in RBCs

As RBCs navigate the circulation system and sneak through the interendothelial slits in splenic sinusoids, they experience shear stress and mechanical pressure.53 These mechanical forces can activate PIEZO1 channels and promote Ca2+ influx through PIEZO1.33,54 We, therefore, tested whether PIEZO1-mediated Ca2+ influx can activate TMEM16F. We first overexpressed PIEZO1 in HEK293T cells that stably express TMEM16F (supplemental Figure 2A). Upon application of Yoda1, a PIEZO1-specific agonist,55 intracellular Ca2+ increased, followed by increased PS exposure. However, in the TMEM16F deficient (KO) HEK293T cells overexpressing PIEZO1, no PS exposure was observed even though Yoda1-triggered Ca2+ elevation remained unaltered (supplemental Figure 2B-C), suggesting that Ca2+ entry through PIEZO1 activates TMEM16F CaPLSase to promote PS exposure. We further validated this using the PCLSF assay (supplemental Figure 2D-G). Yoda1 first triggered a small outward-inactivating current in both TMEM16F stable and KO HEK293T cells (supplemental Figure 2D-E), which is likely mediated by PIEZO1. Subsequently, a much larger outward-rectifying, voltage- and time-dependent current gradually developed in TMEM16F stable HEK293T cells, which was accompanied by AnV signal increase on the cell surface. The slowly developed current and AnV surface accumulation were not observed in TMEM16F-KO HEK293T cells overexpressing PIEZO1 (supplemental Figure 2E-G). Our Yoda1 experiments thus indicated that Ca2+ entry through PIEZO1 activates TMEM16F in HEK293T cells. Next, we sought to investigate whether mechanical force, a physiological stimulus for PIEZO1, can also lead to TMEM16F activation using cell-attached patch clamping. When we applied membrane suction at −50 mmHg, a negative pressure that fully activates PIEZO1,56 a time- and voltage-dependent, outward-rectifying current gradually developed in HEK293T cells overexpressing both PIEZO1 and TMEM16F (supplemental Figure 2H; TMEM16F+/PIEZO+). The appearance of this current depended on both the extracellular Ca2+ and the coexpression of TMEM16F and PIEZO1 (supplemental Figure 2H-I). When extracellular Ca2+ was eliminated or TMEM16F was not expressed, the membrane suction only elicit a smaller, instantaneous current that depends on PIEZO1 expression and is sensitive to PIEZO1 inhibitor GsMTx4, but not the TMEM16F-like current (supplemental Figure 2I-J). Our cell-attached patch-clamp recording thus demonstrated that mechanical stimulation of PIEZO1 leads to local Ca2+ increase, which subsequently activates TMEM16F.

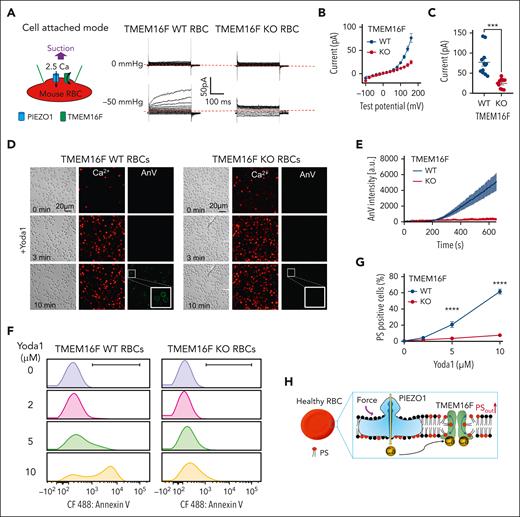

Next, we used 4 different approaches to establish the functional coupling between Piezo1 and TMEM16F in murine RBCs. First, we used cell-attached patch-clamp recording to measure membrane suction-induced TMEM16F channel activation as we did in HEK293T cells (Figure 2A). A negative pressure at −50 mmHg elicited a TMEM16F-like current in 13 out of 21 (62%) WT RBCs recorded. The suction-induced TMEM16F-like current was not observed in (0/10) TMEM16F-KO RBCs (Figure 2A-C). These results suggested that mechanical stimulation of Piezo1 in murine RBCs can induce Ca2+ influx and subsequent TMEM16F activation when both proteins reside in a small membrane patch within the glass pipette (Figure 2A). We only observed suction-induced TMEM16F activation in 62% of recorded RBCs. This is likely due to the relatively low expression level of Piezo1 in RBCs (∼80 proteins/RBC).57

Ca2+ influx through PIEZO1 activates TMEM16F in murine RBCs. (A) Representative cell-attach patch-clamp recording (schematic on left) in TMEM16F WT and knockout (KO) murine RBCs with 0 and –50 mmHg suction. The membrane was depolarized by voltage steps from –100 mV to +160 mV with 20 mV increment. A total of 2.5 mM Ca2+ in the pipette and a holding voltage at –60 mV enable Ca2+ influx and subsequent activation of TMEM16F current. (B) I-V relationship of the current recorded in A. (C) Statistical analysis of current at +160 mV. The results are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-sided Student t test, ∗∗∗P < .001 (n = 12 for WT and 10 for KO). (D) Representative images of 10 μM Yoda1-induced Ca2+ increase (red) and lipid scrambling (AnV, green) in RBCs from TMEM16F WT (left) and KO (right) mice. White boxes show enlarged views. (E) Time-dependent lipid scrambling reported by AnV in the RBCs from TMEM16F WT and KO mice stimulated by Yoda1. Error bars represent SEM. At least 3 biological repeats were done for WT (n = 18) and KO (n = 19) groups. (F) Flow cytometry quantification of Ca2+–induced lipid scrambling (reported by AnV 488) in WT (left) and TMEM16F-KO (right) murine RBCs in response to different concentrations of Yoda1. The y-axis represents cell counts. (G) Quantification of the percentage of PS-positive RBCs in response to different concentrations of Yoda1. Error bars represent SEM. The statistical analysis was done with 2-way analysis of variance followed by Sidak multiple comparisons tests, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, n = 6 to 9 repeats for WT and KO RBCs at each dose. (H) Cartoon illustration of PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling in healthy RBCs. Ca2+ influx through PIEZO1 activates TMEM16F in the vicinity.

Ca2+ influx through PIEZO1 activates TMEM16F in murine RBCs. (A) Representative cell-attach patch-clamp recording (schematic on left) in TMEM16F WT and knockout (KO) murine RBCs with 0 and –50 mmHg suction. The membrane was depolarized by voltage steps from –100 mV to +160 mV with 20 mV increment. A total of 2.5 mM Ca2+ in the pipette and a holding voltage at –60 mV enable Ca2+ influx and subsequent activation of TMEM16F current. (B) I-V relationship of the current recorded in A. (C) Statistical analysis of current at +160 mV. The results are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-sided Student t test, ∗∗∗P < .001 (n = 12 for WT and 10 for KO). (D) Representative images of 10 μM Yoda1-induced Ca2+ increase (red) and lipid scrambling (AnV, green) in RBCs from TMEM16F WT (left) and KO (right) mice. White boxes show enlarged views. (E) Time-dependent lipid scrambling reported by AnV in the RBCs from TMEM16F WT and KO mice stimulated by Yoda1. Error bars represent SEM. At least 3 biological repeats were done for WT (n = 18) and KO (n = 19) groups. (F) Flow cytometry quantification of Ca2+–induced lipid scrambling (reported by AnV 488) in WT (left) and TMEM16F-KO (right) murine RBCs in response to different concentrations of Yoda1. The y-axis represents cell counts. (G) Quantification of the percentage of PS-positive RBCs in response to different concentrations of Yoda1. Error bars represent SEM. The statistical analysis was done with 2-way analysis of variance followed by Sidak multiple comparisons tests, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, n = 6 to 9 repeats for WT and KO RBCs at each dose. (H) Cartoon illustration of PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling in healthy RBCs. Ca2+ influx through PIEZO1 activates TMEM16F in the vicinity.

We also tested Yoda1-induced TMEM16F activation in RBCs using 2 independent approaches with single-cell resolution. Our confocal fluorescence imaging experiments showed that Yoda1 induced Ca2+ elevation followed by PS exposure in WT RBCs (Figure 2D-E). Despite comparable Ca2+ increase in TMEM16F KO RBCs upon Yoda1 stimulation, no PS exposure was observed. Consistently, our PCLSF recorded Yoda1-induced PS exposure in WT but not in TMEM16F KO RBCs (supplemental Figure 3A-C). Concomitantly, we monitored the onset time (ton) of TMEM16F current after Yoda1 application. A time- and voltage-dependent outward-rectifying current developed in WT RBCs but not in TMEM16F-KO RBCs (supplemental Figure 3D-F). The relatively long delay on eliciting TMEM16F current in WT RBCs has been well-documented in other cell types,31,51,58,59 with the underlying cause still under debate.60

Lastly, we used flow cytometry to quantify Piezo1-TMEM16F coupling by monitoring Yoda1-induced PS exposure in a large population of RBCs. We found that Yoda1 dose-dependently induced PS exposure in WT RBCs (Figure 2F-G). With 10 μM Yoda1, 55.8 ± 4.3% of WT RBCs became PS positive. In stark contrast, Yoda1–induced PS exposure was largely diminished in TMEM16F-KO RBCs (Figure 2F-G), which is consistent with our observations using the single-cell approaches (Figure 2A-E and supplemental Figure 3).

Taken together, our experiments demonstrated that TMEM16F CaPLSase is functionally coupled to Piezo1 in murine RBCs (Figure 2H). Mechanical activation of Piezo1 increases intracellular Ca2+ and subsequently activates TMEM16F.

HX RBCs show enhanced PS exposure

GOF mutations of PIEZO1 with impaired inactivation cause HX or dehydrated hereditary stomatocytosis.35-38,42,44,48 This rare autosomal dominant hemolytic anemia is characterized by RBC dehydration owing to enhanced coupling between PIEZO1 GOF channels and Gardos K+ channel, which leads to excessive K+ and water efflux.33,42,44,48,61 We reasoned whether PIEZO1 GOF promotes PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling in HX RBCs to increase PS exposure.

First, we overexpressed human PIEZO1 (hPIEZO1) WT and R2456H, a severe HX mutation with slow inactivation kinetics,48,56 in the TMEM16F stable HEK293T cells. Yoda1 triggered Ca2+ increase followed by time-dependent increase of PS exposure reported by AnV signal on cell surfaces (supplemental Figure 4A-B). Analysis of the time course of AnV signal accumulation showed that R2456H GOF mutation significantly accelerated Yoda1–induced PS exposure, as evaluated by the half time (t1/2) to reach the maximum AnV intensity at 10 minutes after Yoda1 application49,62 (supplemental Figure 4C-D). This supports that R2456H enhances PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling. Consistently, our patch-clamp recording also showed that Yoda1-induced TMEM16F channel activation appeared significantly faster in hPIEZO1-R2456H–expressing cells than in WT-expressing cells, evaluated by the onset time (ton) of the time- and voltage-dependent outward-rectifying current (supplemental Figure 4E-H). Our HEK293T experiments demonstrated that the HX-associated PIEZO1 GOF enhances TMEM16F activation.

Using the HX mouse model carrying mouse Piezo1 (mPiezo1) R2482H mutation (equivalent of hPIEZO1 R2456H),48 we tested whether Piezo1 GOF indeed enhances TMEM16F activation in murine RBCs. Our flow cytometry experiments revealed that a lower concentration of Yoda1 (5 μM) mildly induced PS exposure in <20% of Piezo1 WT RBCs. In contrast, this Yoda1 concentration substantially promoted PS exposure in ∼100% of R2482H HX RBCs (supplemental Figure 5A-C). Consistent with our flow cytometry observation, our single-cell approaches show that the majority of the HX murine RBCs became PS exposed with significantly stronger AnV intensity upon Yoda1 stimulation, whereas the same treatment only triggered PS exposure in a limited number of WT RBCs (supplemental Figure 5D-G). Our membrane-stretch experiments under cell-attached patch-clamp configuration further demonstrated that mechanical force induced more TMEM16F channel activation in the HX RBCs than in the WT RBCs (supplemental Figure 5H-J). Taken together, our experiments demonstrated that the murine HX RBCs with Piezo1 GOF show enhanced Piezo1-TMEM16F coupling, resulting in a dramatically increased propensity to expose PS.

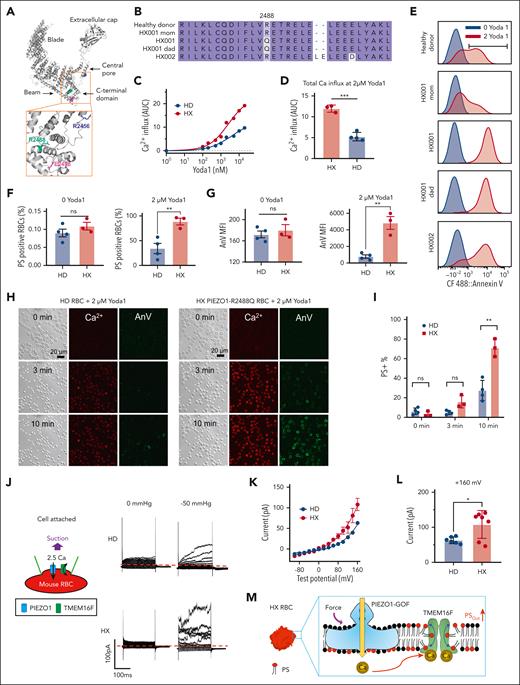

To examine if human HX RBCs also show enhanced PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling and PS exposure, we recruited 3 individuals carrying 2 different PIEZO1 mutations (Figure 3A-B). Patient HX001 and her father (HX001 dad) carry the same R2488Q PIEZO1 GOF mutation,38,42,45 whereas mother (HX001 mom) does not carry a GOF PIEZO1 mutation, consistent with the autosomal dominant trait of the disease. The third patient carries a previously reported PIEZO1 GOF variant E2496ELE (p.Leu2495_Glu2496dup)38 with an additional variant E2498D. Yoda1–induced Ca2+ influx was significantly higher in the HX RBCs than in the HD RBCs (supplemental Figure 6A and Figure 3C-D), confirming their PIEZO1 GOF phenotype.

PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling is enhanced in the RBCs from patients with HX with GOF PIEZO1 mutations. (A) Spatial distribution of 3 PIEZO1-HX mutations in a PIEZO1 structure. (B) Sequence alignment of PIEZO1 of HDs and patients with HX. (C) Yoda1 dose-dependent increase of intracellular Ca2+ in HD and HX RBCs. The results were averaged from 4 HD samples and 3 HX samples. Measurement of each sample was repeated at least 3 times. (D) Total Ca2+ influx shown in panel C as quantified by area under curve (AUC). (E) Flow cytometry analysis of 2 μM Yoda1-induced PS exposure in RBC samples from HD and patients with HX. (F) Percentage of PS-positive cells in RBCs of HDs and patients with HX with and without Yoda1 treatment. (G) AnV mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in RBCs of HDs and patients with HX with (right) and without (left) Yoda1 treatment. MFI was calculated as geometric mean in FCS Express software. (H) Representative images of 2 μM Yoda1-induced PS exposure reported by AnV in RBCs from an HD and HX001 patient. (I) The averaged percentage of PS-positive cells in HDs (n = 4) and patients with HX (n = 3) at different time points after Yoda1 induction. For panels D,F-G,I, each dot represents the average of at least 3 repeats for each blood sample (n = 3 and 4 for HD and HX, respectively). Unpaired 2-sided Student t test. ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ns, no significance. (J) Representative cell-attached patch-clamp recording (schematic on left) in HD and HX001 RBCs elicited by a –50 mmHg negative pressure. The membrane was depolarized by voltage steps from –100 mV to +160 mV with 20 mV increment. A total of 2.5 mM Ca2+ was included in the pipette and a holding voltage at –60 mV enables Ca2+ influx and subsequent activation of endogenous TMEM16 current. (K) I-V relationship of suction-induced currents recorded in panel J. (L) Statistical analysis of peak current amplitude at +160 mV. The results are presented as mean ± SEM (unpaired 2-sided Student t test, ∗P < .05, n = 6 and 7 for WT and HX, respectively). (M) Illustration of enhanced PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling resulting in elevated PS exposure.

PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling is enhanced in the RBCs from patients with HX with GOF PIEZO1 mutations. (A) Spatial distribution of 3 PIEZO1-HX mutations in a PIEZO1 structure. (B) Sequence alignment of PIEZO1 of HDs and patients with HX. (C) Yoda1 dose-dependent increase of intracellular Ca2+ in HD and HX RBCs. The results were averaged from 4 HD samples and 3 HX samples. Measurement of each sample was repeated at least 3 times. (D) Total Ca2+ influx shown in panel C as quantified by area under curve (AUC). (E) Flow cytometry analysis of 2 μM Yoda1-induced PS exposure in RBC samples from HD and patients with HX. (F) Percentage of PS-positive cells in RBCs of HDs and patients with HX with and without Yoda1 treatment. (G) AnV mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in RBCs of HDs and patients with HX with (right) and without (left) Yoda1 treatment. MFI was calculated as geometric mean in FCS Express software. (H) Representative images of 2 μM Yoda1-induced PS exposure reported by AnV in RBCs from an HD and HX001 patient. (I) The averaged percentage of PS-positive cells in HDs (n = 4) and patients with HX (n = 3) at different time points after Yoda1 induction. For panels D,F-G,I, each dot represents the average of at least 3 repeats for each blood sample (n = 3 and 4 for HD and HX, respectively). Unpaired 2-sided Student t test. ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ns, no significance. (J) Representative cell-attached patch-clamp recording (schematic on left) in HD and HX001 RBCs elicited by a –50 mmHg negative pressure. The membrane was depolarized by voltage steps from –100 mV to +160 mV with 20 mV increment. A total of 2.5 mM Ca2+ was included in the pipette and a holding voltage at –60 mV enables Ca2+ influx and subsequent activation of endogenous TMEM16 current. (K) I-V relationship of suction-induced currents recorded in panel J. (L) Statistical analysis of peak current amplitude at +160 mV. The results are presented as mean ± SEM (unpaired 2-sided Student t test, ∗P < .05, n = 6 and 7 for WT and HX, respectively). (M) Illustration of enhanced PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling resulting in elevated PS exposure.

Our flow cytometry measurements showed that 2 μM Yoda1 induced PS exposure in over 80% of the HX RBCs, whereas the same stimulation only triggered PS exposure in an average of ∼30% HD RBCs (Figure 3E-F and supplemental Figure 6B-C). In addition, the mean AnV intensity was also significantly higher in the HX RBCs (supplemental Figure 6D and Figure 3G). Our results indicate that human HX RBCs tend to expose more PS than HD RBCs upon Yoda1 stimulation. Interestingly, the PS exposure induced by the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 was comparable in both the HX and HD RBCs (supplemental Figure 7), suggesting that the expression and function of TMEM16F was unaltered in HX RBCs. Therefore, the enhanced PS exposure in HX RBCs is derived from augmented Ca2+ influx through the GOF PIEZO1 channels and subsequent TMEM16F activation. Our fluorescence lipid scrambling imaging assay further supported our flow cytometry findings. Ten minutes after Yoda1 stimulation, ∼80% HX RBCs displayed PS, whereas only ∼30% of HD RBCs were PS positive (Figure 3H-I, supplemental Figure 5E, and supplemental Videos 1 and 2). Furthermore, the intensity of AnV staining was notably higher in the HX RBCs than in the HD RBCs after Yoda1 treatment (Figure 3H). Our cell-attached patch-clamp recording with membrane suction also demonstrated that mechanical stimulation elicited more TMEM16F current in the HX RBCs (Figure 3J-L).

In summary, our characterization of human and murine HX RBCs demonstrated that mechanical stimulation of the GOF mutant PIEZO1 channels lead to augmentation of intracellular Ca2+, which enhances TMEM16F activation and subsequent excessive PS exposure (Figure 3M).

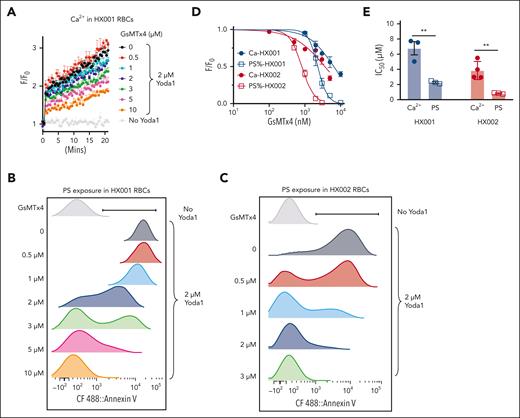

Decoupling PIEZO1-TMEM16F prevents HX RBC PS exposure

Loss of lipid asymmetry in RBCs exposes PS, which may contribute to the complications associated with HX, including enhanced endothelial adherence, increased extracellular vesiculation, splenomegaly, anemia, iron overload, and thrombosis.15-22,61,63 Therefore, inhibiting GOF PIEZO1, the etiology of PIEZO1-associated HX, is expected to prevent excessive PS exposure and ameliorate HX-associated complications. GsMTx-4, a peptide toxin extracted from tarantula venom, is a widely used inhibitor of mechanosensitive ion channels including PIEZO1.64,65 Indeed, GsMTx-4 dose-dependently suppressed Yoda1-induced Ca2+ increase in HX RBCs with a 50% infective dose (IC50) of 6.8 ± 1.2 μM for HX001 and 3.9 ± 1.0 μM for HX002 (Figure 4A,D-E). Consistent with its inhibitory effect on Ca2+ increase, GsMTx-4 also inhibited Yoda1-induced PS exposure in HX RBCs in a dose-dependent manner with IC50 of 2.3 ± 0.2 μM for HX001 and 0.8 ± 0.1 μM for HX002 (Figure 4B-E). Interestingly, the IC50 value of GsMTx-4 for inhibiting PS exposure was significantly lower than that for inhibiting Ca2+ increase (Figure 4D-E). This result suggests that it is easier to decouple PIEZO1-TMEM16F interaction and prevent PS exposure in RBCs than to inhibit PIEZO1-mediated Ca2+ entry. This is consistent with the relatively low Ca2+ sensitivity for TMEM16F.27 The nonoverlapping dose response curves for Ca2+ increase and PS exposure (Figure 4D) suggest that there is a relatively wide therapeutic window, in which a PIEZO1 inhibitor could efficiently abolish TMEM16F CaPLSase–mediated PS exposure with only partial inhibition of PIEZO1-mediated Ca2+ increase.

PIEZO1 inhibitor GsMTx-4 breaks PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling and prevents excessive PS exposure in HX RBCs. (A) GsMTx-4 dose-dependently inhibits Yoda1–induced Ca2+ influx in HX001 RBCs. Error bars represent ± SEM from 3 replicates. (B-C) Representative flow cytometry data of GsMTx-4 inhibition on Yoda1 (2 μM)-induced PS exposure in HX001 (B) and HX002 (C) RBCs. CF488-AnV was used as a fluorescence PS marker. Each concentration of GsMTx4 was repeated in 3 independent experiments. (D) Dose-response curves of GsMTx-4 inhibition on Ca2+ increase (solid circle) and PS exposure (open square) in the RBCs from HX001 (black) and HX002 (red) patients. All signals were normalized to 0 GsMTx-4 condition and fitted with the Hill equation (see “Methods”). (E) IC50 of GsMTx-4 on Yoda1-induced Ca2+ influx and PS exposure in HX001 and HX002 RBCs. Unpaired 2-sided Student t test. ∗∗P < .01, n = 3 to 4 repeats.

PIEZO1 inhibitor GsMTx-4 breaks PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling and prevents excessive PS exposure in HX RBCs. (A) GsMTx-4 dose-dependently inhibits Yoda1–induced Ca2+ influx in HX001 RBCs. Error bars represent ± SEM from 3 replicates. (B-C) Representative flow cytometry data of GsMTx-4 inhibition on Yoda1 (2 μM)-induced PS exposure in HX001 (B) and HX002 (C) RBCs. CF488-AnV was used as a fluorescence PS marker. Each concentration of GsMTx4 was repeated in 3 independent experiments. (D) Dose-response curves of GsMTx-4 inhibition on Ca2+ increase (solid circle) and PS exposure (open square) in the RBCs from HX001 (black) and HX002 (red) patients. All signals were normalized to 0 GsMTx-4 condition and fitted with the Hill equation (see “Methods”). (E) IC50 of GsMTx-4 on Yoda1-induced Ca2+ influx and PS exposure in HX001 and HX002 RBCs. Unpaired 2-sided Student t test. ∗∗P < .01, n = 3 to 4 repeats.

Antigout benzbromarone blocks PIEZO1

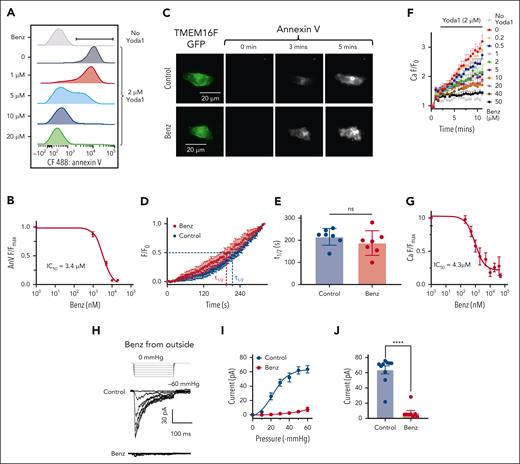

Although GsMTx-4 has demonstrated effectiveness in inhibiting the coupling, it has not been authorized for human use, and there is currently no Food and Drug Administration–approved medication for inhibiting PIEZO1. Our previous study showed that benzbromarone, an uricosuric medication to treat gout, can block TMEM16A Ca2+–activated Cl− channel.66 A recent study reported that benzbromarone may also inhibit TMEM16F.67,68 We thus tested if benzbromarone might be repurposed to prevent PS exposure–associated HX complications by inhibiting TMEM16F CaPLSase. Our flow cytometry characterization showed that benzbromarone dose-dependently prevented Yoda1-induced PS exposure in HX RBCs with IC50s of 3.4 ± 0.04 μM for HX001, 1.29 ± 0.01 μM for HX002, and 4.41 ± 0.03 μM for Piezo1-R2482H mice (Figure 5A-B and supplemental Figure 8). Upon further characterizations of benzbromarone on heterologously expressed TMEM16F in HEK293T cells using PCLSF, we arrived at the intriguing conclusion that benzbromarone did not exhibit any obvious effect on TMEM16F CaPLSase (Figure 5C-E) or ion channel activity (supplemental Figure 9A-C). To rule out the potential adverse effect of benzbromarone on intracellular signaling, we conducted excised patch-clamp recording under outside-out configuration (supplemental Figure 9D-F). Our results using imaging and patch-clamp approaches explicitly demonstrated that benzbromarone has no inhibitory effect on TMEM16F. The reported inhibitory effect of benzbromarone67 is likely due to its off-target effect on suppressing intracellular Ca2+ signaling.69

Benzbromarone (Benz) suppresses Yoda1-induced PS exposure by inhibition of PIEZO1. (A) Benz dose-dependently inhibits Yoda1-induced PS exposure in HX001 RBCs. The flow cytometry experiments were done using CF488-AnV as a PS marker. (B) Benz dose-dependently inhibits Yoda1–induced PS exposure in HX001 RBCs. The AnV signals were normalized to zero Benz condition. The signals were fitted with the Hill equation (see “Methods”). Three independent repeats were done for each Benz concentration. (C) Representative PCLSF images of TMEM16F-mediated PS exposure in the absence (top) and presence of 20 μM extracellular Benz (bottom). Images were acquired every 5 seconds after membrane break-in under whole-cell configuration. TMEM16F was activated by pipette Ca2+. (D) Time course of TMEM16F-mediated PS exposure under PCLSF with and without Benz. t1/2 is the time for the AnV intensity to reach half maximum within the recorded time frame. The results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 7 for each group). (E) Comparison of t1/2 with and without Benz. The results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was done by unpaired 2-sided Student t test (ns means no significant, n = 7 for each group). (F) Benz dose-dependently inhibits Yoda1 (2 μM)-induced Ca2+ influx in HX001 RBCs. Error bars represent SEM from 4 independent repeats. (G) Dose-response curve of Benz inhibition on Yoda1-induced Ca2+ influx in HX001 RBCs. The signals were normalized to zero Benz condition. The Ca2+ signals were fitted with the Hill equation (see “Methods”). (H) Representative cell-attached patch-clamp recording of PIEZO1 current in the presence and absence (Control) of 20 μM Benz in the pipette solution. Human PIEZO1 was overexpressed in HEK293T cells. The current was elicited by pressure clamp from 0 to −60 mmHg with a holding potential at −80 mV. (I) PIEZO1 current-pressure relationship with and without extracellular Benz. Error bars represent SEM (n = 10 and 8 for control and Benz group, respectively). (J) PIEZO1 current amplitudes at –60 mmHg with and without extracellular Benz. Statistical analysis was done by unpaired 2-sided Student t test. (∗∗∗∗P < .0001, n = 10 and 8 for control and Benz groups, respectively).

Benzbromarone (Benz) suppresses Yoda1-induced PS exposure by inhibition of PIEZO1. (A) Benz dose-dependently inhibits Yoda1-induced PS exposure in HX001 RBCs. The flow cytometry experiments were done using CF488-AnV as a PS marker. (B) Benz dose-dependently inhibits Yoda1–induced PS exposure in HX001 RBCs. The AnV signals were normalized to zero Benz condition. The signals were fitted with the Hill equation (see “Methods”). Three independent repeats were done for each Benz concentration. (C) Representative PCLSF images of TMEM16F-mediated PS exposure in the absence (top) and presence of 20 μM extracellular Benz (bottom). Images were acquired every 5 seconds after membrane break-in under whole-cell configuration. TMEM16F was activated by pipette Ca2+. (D) Time course of TMEM16F-mediated PS exposure under PCLSF with and without Benz. t1/2 is the time for the AnV intensity to reach half maximum within the recorded time frame. The results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 7 for each group). (E) Comparison of t1/2 with and without Benz. The results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was done by unpaired 2-sided Student t test (ns means no significant, n = 7 for each group). (F) Benz dose-dependently inhibits Yoda1 (2 μM)-induced Ca2+ influx in HX001 RBCs. Error bars represent SEM from 4 independent repeats. (G) Dose-response curve of Benz inhibition on Yoda1-induced Ca2+ influx in HX001 RBCs. The signals were normalized to zero Benz condition. The Ca2+ signals were fitted with the Hill equation (see “Methods”). (H) Representative cell-attached patch-clamp recording of PIEZO1 current in the presence and absence (Control) of 20 μM Benz in the pipette solution. Human PIEZO1 was overexpressed in HEK293T cells. The current was elicited by pressure clamp from 0 to −60 mmHg with a holding potential at −80 mV. (I) PIEZO1 current-pressure relationship with and without extracellular Benz. Error bars represent SEM (n = 10 and 8 for control and Benz group, respectively). (J) PIEZO1 current amplitudes at –60 mmHg with and without extracellular Benz. Statistical analysis was done by unpaired 2-sided Student t test. (∗∗∗∗P < .0001, n = 10 and 8 for control and Benz groups, respectively).

To understand the intriguing roles of benzbromarone on TMEM16F activation and Yoda1-induced PS exposure, we examined its effect on Yoda1-induced Ca2+ increase in HX RBCs. We found that benzbromarone dose-dependently inhibited Ca2+ increase with an IC50 of 4.3 ± 0.98 μM (Figure 5F-G). To test if benzbromarone prevents TMEM16F-mediated PS exposure in HX RBCs by directly inhibiting PIEZO1, we measured the effect of benzbromarone on PIEZO1 current from HEK293T cells using both cell-attached (Figure 5H-J) and excised inside-out (supplemental Figure 10) patch clamp under the control of a pressure clamp device. We found that 20 μM benzbromarone almost completely abolished membrane suction-induced PIEZO1 current from both sides of the membrane. The inhibitory effect on PIEZO1 is reversible (supplemental Figure 10), further supporting that benzbromarone directly works on PIEZO1. All these support that benzbromarone, instead of inhibiting TMEM16F, blocks PIEZO1, prevents PIEZO1-mediated Ca2+ entry, and subsequent TMEM16F CaPLSase–mediated PS exposure.

PIEZO1 inhibition protects HX RBCs

Upon mechanical stimulation, elevated Ca2+ entry through PIEZO1 GOF promotes the activation of Ca2+-sensitive K+ channel Gardos in HX RBCs,33 leading to water efflux and RBC dehydration, a hallmark of HX.35,38 We reasoned that PIEZO1 inhibition could prevent RBC dehydration induced by mechanical stimulations, such as centrifugation. Although a 12-minute centrifugation at 900g did not cause any noticeable morphological changes in HD or WT mouse RBCs (Figure 6A and supplemental Figure 11A), it drastically induced echinocytosis of HX001 (Figure 6B-E), HX002 (supplemental Figure 11C) and Piezo1-R2482H murine RBCs (supplemental Figure 11B), further supporting that HX RBCs have markedly increased force sensitivity. Both GsMTx-4 and benzbromarone dose-dependently prevent centrifugation-induced echinocytosis of the HX RBCs (Figure 6B-E and supplemental Figure 11B-E), indicating that PIEZO1 inhibition is effective in preventing this common cellular alteration associated with HX RBCs.

Inhibition of PIEZO1 prevents echinocytosis and hemolysis in HX001 RBCs. (A) Representative images of RBCs from a HD before and after centrifugation. (B-C) Representative images of the RBCs from HX001 with various concentrations of GsMTx-4 (B) and Benz (C) before and after centrifugation. (D-E) Effect of GsMTx-4 (D) and Benz (E) on spin-induced RBC echinocytosis (see “Methods” for details). (F) Representative photos of 2 μM Yoda1(Y1)-induced hemolysis in HX RBCs with and without 5 μM GsMTx-4. 0 Yoda1 (left) and H2O (right) serve as negative and positive controls, respectively. (G) Representative images of 2 μM Yoda1-induced hemolysis with and without 20 μM Benz at different time points as indicated. (H) Time course of 2 μM Yoda1(Y1)-induced with and without 5 μM spider toxin GsMTx-4 in HX001 RBCs. Results were normalized to the water-induced fully lysed group. (I) Time course of 2 μM Yoda1 (Y1)-induced hemolysis with and without 20 μM Benz in HX001 RBCs. Results were normalized to the water-induced fully lysed group. (J) Yoda1-induced RBCs hemolysis percentage at 120 minutes with and without GsMTx-4 and Benz. Unpaired 2-sided Student t test, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, n = 3 to 6 repeats for each condition. (K) Partially inhibiting PIEZO1 can effectively disrupt PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling in HX RBCs and prevent HX-associated complications.

Inhibition of PIEZO1 prevents echinocytosis and hemolysis in HX001 RBCs. (A) Representative images of RBCs from a HD before and after centrifugation. (B-C) Representative images of the RBCs from HX001 with various concentrations of GsMTx-4 (B) and Benz (C) before and after centrifugation. (D-E) Effect of GsMTx-4 (D) and Benz (E) on spin-induced RBC echinocytosis (see “Methods” for details). (F) Representative photos of 2 μM Yoda1(Y1)-induced hemolysis in HX RBCs with and without 5 μM GsMTx-4. 0 Yoda1 (left) and H2O (right) serve as negative and positive controls, respectively. (G) Representative images of 2 μM Yoda1-induced hemolysis with and without 20 μM Benz at different time points as indicated. (H) Time course of 2 μM Yoda1(Y1)-induced with and without 5 μM spider toxin GsMTx-4 in HX001 RBCs. Results were normalized to the water-induced fully lysed group. (I) Time course of 2 μM Yoda1 (Y1)-induced hemolysis with and without 20 μM Benz in HX001 RBCs. Results were normalized to the water-induced fully lysed group. (J) Yoda1-induced RBCs hemolysis percentage at 120 minutes with and without GsMTx-4 and Benz. Unpaired 2-sided Student t test, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, n = 3 to 6 repeats for each condition. (K) Partially inhibiting PIEZO1 can effectively disrupt PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling in HX RBCs and prevent HX-associated complications.

HX RBCs are more susceptible than normal RBCs to hemolysis.43,46 We hypothesized that PIEZO1 GOF-induced Ca2+ overload may contribute to augmented hemolysis in HX RBCs whereas PIEZO1 inhibition can prevent hemolysis. To test this hypothesis, we introduced Ca2+ overload by incubating the RBCs with 2 μM Yoda1 and continuously measured the extent of hemolysis over time. We indeed observed time-dependent increase of hemolysis in the RBCs, which was effectively prevented by GsMTx-4 and benzbromarone (Figure 6F-J and supplemental Figure 11F-K). Our findings thus demonstrated that PIEZO1 inhibition effectively prevents Ca2+ overload-induced morphological changes, excessive PS exposure and hemolysis in HX RBCs (Figure 6K).

Discussion

Our study unveils TMEM16F as the long-sought-after RBC CaPLSase and its activation mechanism through Ca2+ influx through mechanosensitive PIEZO1 channels. We discover that HX RBCs with PIEZO1 GOF mutations have an increased propensity to expose PS, which is consistent with a previous finding that the HX RBCs have increase extracellular vesiculation,63 a processes usually concomitant with scramblase-mediated loss of lipid asymmetry.28 More PS exposure in HX RBCs is due to an enhanced PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling, which may contribute to HX complications, such as splenomegaly, anemia, and thrombosis (Figure 6K). Furthermore, our findings demonstrate that inhibiting PIEZO1 with GsMTx-4 or benzbromarone, a new PIEZO1 blocker discovered in this study, efficiently prevent PIEZO1 GOF-induced RBC echinocytosis, hemolysis, and excessive PS exposure.

Increased propensity of PS exposure in HX RBCs can cause 2 major complications (Figure 6K). Firstly, excessive exposure of PS, an “eat-me” signal, can facilitate splenic phagocytosis of PS-positive senescent or injured RBCs, leading to anemia and splenomegaly, the common clinical manifestations of HX.46 The Piezo1-R2482H mutant mice indeed show severe splenomegaly,48 supporting the role of enhanced PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling in HX pathophysiology. Secondly, PS-positive RBCs and RBC-associated microparticles can increase procoagulant surface, promoting clot formation and increasing thrombotic risk.19,20,70,71 Interestingly, the thrombotic risk is particularly high in patients with PIEZO1-associated HX who have undergone splenectomy.46 Based on this study, it is plausible that enhanced TMEM16F CaPLSase activity and TMEM16F-mediated PS exposure in HX RBCs may dramatically increase thrombotic risks when the spleen, the major organ to sequester PS-positive senescent RBCs, is removed. Future characterizations in mouse models with enhanced Piezo1 activity and TMEM16F deficiency are needed to test this hypothesis.

The recently revised HX prevalence increases from 1:50 000 to 1:8000, and no effective therapy is currently available to cure this rare blood disorder.34 Our discovery of enhanced PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling in HX RBCs provides new therapeutic insights. First, partial inhibition of PIEZO1 is a promising strategy to prevent complications induced by PIEZO1 GOF, including enhanced TMEM16F activation and excessive PS exposure. Given that TMEM16F has relatively low Ca2+ sensitivity,27 partially inhibiting PIEZO1 effectively decouples PIEZO1-TMEM16F interaction and prevent TMEM16F-mediated PS exposure (Figure 6K). This approach preserves the vital PIEZO1 functions, reducing potential adverse effects. Second, because intense exercise exacerbates hemolysis in HX,72 lifestyle changes, such as avoiding intense physical activities, may help prevent excessive mechanical stimulation on HX RBCs and subsequent complications. Indeed, our results indicated that partial inhibition of PIEZO1 with GsMTx-4 and benzbromarone, effectively prevents Ca2+ overload, RBC echinocytosis, TMEM16F-mediated PS exposure, and hemolysis. Benzbromarone is a uricosuric medication for gout treatment. With prudence in prescription dosage, it may be repurposed to treat HX and HX-associated complications. Although it is not approved in the United States towing to concerns over hepatotoxicity, reports of benzbromarone–related severe side effects are rare.73,74 Future preclinical investigations are needed before it can be translated into HX therapeutics.

Patients with HX exhibit various degrees of hemolytic anemia.46 Majority of the patients show mild-to-moderate compensated anemia, and only the patients with severe hemolytic anemia need medical attention. However, a recent study reported that a HX mouse model show age-onset iron overload; and even PIEZO1-E756del, a mild GOF PIEZO1 variant present in one-third of African descents, shows strong association with increased plasma iron.75 With more PIEZO1 GOF variants being identified, it is critical to conduct longitudinal clinical investigations to evaluate the long-term effects of PIEZO1 GOF on the health of the patients with HX. We anticipate that our findings will shine light on the treatment and prevention of HX-related complications.

Discovery of PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling in RBCs has broader clinical implications. It is well-documented that other RBC disorders including sickle-cell disease and thalassemia, 2 common types of hemoglobinopathy, are often accompanied by PS-positive RBCs.76,77 These diseases also carry an increased risk of thrombosis. Future studies should investigate if PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling is also augmented in these RBC disorders and if inhibition of this coupling may be a new treatment option. Interestingly, PIEZO1 is also expressed in a megakaryocytic cell line and mature platelets albeit at relatively low expression levels.78 It will be interesting to dissect PIEZO1-TMEM16F coupling in platelet mechanobiology and blood coagulation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ardem Patapoutian for providing the HX mouse blood samples and Philip A. Gottlieb for sharing the PIEZO1 plasmids. The authors are grateful to the patients with HX and healthy donors for their blood donation. The authors appreciate the technical assistance from Jorg Grandl, Amanda Lewis, and Michael Young in characterizing PIEZO1. The authors also thank Vann Bennett for his constructive comments on the manuscript, Xiangmei Kong for collecting mouse blood, and Olivia Yang for the cartoon illustration.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant NIH-DP2GM126898 (H.Y.).

Authorship

Contribution: H.Y. conceived and supervised the project; H.Y., Y.Z., P.L., G.M.A., J.J.S., S.M., and M.J.T. designed the research; P.L., Y.Z., Y.C.S.W., P.D., A.J.L., and S.M. performed the experiments; G.M.A., J.J.S., M.J.T., S.J.F., S.K., M.D., and M.J.T. provided human blood samples; P.L., Y.Z., Y.C.S.W., and P.D. analyzed the data; Y.Z. and P.D. wrote the MATLAB codes; and H.Y., P.L., Y.C.S.W., and Y.Z. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for Y.Z. is Shenzhen Bay Laboratory, Guangdong, China.

Correspondence: Huanghe Yang, Department of Biochemistry, Duke University School of Medicine, Box 3711, DUMC, Durham, NC 27710; email: huanghe.yang@duke.edu.

References

Author notes

∗P.L. and Y.Z. contributed equally to this study.

Data reported in this work and any additional information required to reanalyze the data will be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Huanghe Yang (huanghe.yang@duke.edu). All MATLAB scripts are available at Github.com (https://github.com/superdongping/RedBloodCell and https://github.com/yanghuanghe/scrambling_activity).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal