TO THE EDITOR:

Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) is a complex multifactorial medical condition observed rarely following vaccination with adenovirus-based coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines,1-6 and also after other types of vaccines.7-9 VITT involves platelet factor 4 (PF4) autoimmunity, which is also observed in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.10-12 However, it is now known that VITT and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia antibodies bind separate epitopes on PF4 and have distinct clonal profiles.13-15 We recently discovered highly stereotypic anti-PF4 antibodies in 5 patients with VITT after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination using mass spectrometry–based proteomics. These unique serum clonotypes are specified by identical IGLV3-21∗02 allelic light chains paired with heavy chains expressing shared heavy chain third complementarity–determining region (HCDR)3 amino acids motifs. These findings shed light on the mechanisms of this dangerous adverse reaction and may contribute to understanding how these pathogenic autoantibodies are induced.

Insight into molecular features of anti-PF4 antibodies that mediate binding to positively charged epitopes on PF4 molecules are hampered by limited availability of samples of patients with VITT and lack of anti-PF4 reagents. Herein, we describe the generation and functional characterization of a unique suite of recombinant antibodies (rAbs) derived from serum anti-PF4 proteomes by a reverse-engineering approach that bypasses conventional B-cell sorting and cloning methods.

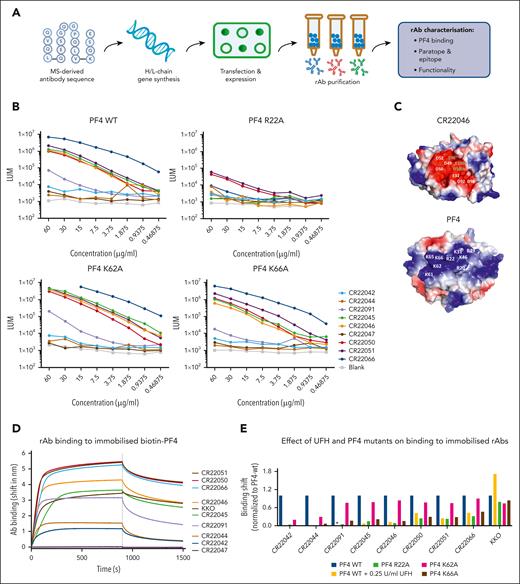

Ig heavy- and light-chain genes were constructed by reverse engineering of mass spectrometry–derived amino acid (aa) sequences of clonotypic anti-PF4 IgGs purified from the sera of patients with VITT16 and expressed as full-length clonotypic IgG1 proteins in CHO cells. Immunoreactivity of synthesised rAbs was tested by anti-PF4 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and biolayer interferometry (BLI) (Figure 1A). Epitope mapping of anti-PF4 rAbs was performed by ELISA and BLI on PF4 alanine mutants R22A, K62A, and K66A, previously identified as critical aa residues for PF4 binding of VITT sera, located within the heparin binding site.13 The ability of anti-PF4 rAbs to form PF4 immune complexes was assessed by FcγRIIa receptor binding assay, and their effect on platelet activation was studied by PF4-induced platelet activation assay (supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website).

Overview of PF4-specific rAb generation and PF4 binding properties. (A) Schematic overview of rAb generation and characterization. (B) PF4-binding rAbs were measured by ELISA. PF4 was directly coated onto 96-well ELISA plates, and rAbs were tested in serial dilutions starting from 60 μg/mL. Results are expressed as chemiluminescence (LUM). (C) Surface representations of a model of the paratope of CR22046 and of the structure of PF4 showing the electrostatic potentials. Clustered negatively charged residues in CR22046 and clustered positively charged residues in PF4 are labeled with white characters. For the CR22046 rAb, the numbering is according to Kabat. (D) Real-time binding curves as measured by BLI were obtained by dipping streptavidin sensors with immobilized PF4-biotin into wells containing 5 μg/mL of each antibody (Ab) for 900 seconds, followed by a dissociation of 600 seconds in empty buffer (10× kinetic buffer). (E) BLI-binding responses were obtained by dipping anti-human Fc sensors with immobilized rAbs into wells containing 3.1 μg/mL of each PF4 mutant. The binding of anti-PF4 rAbs to PF4–wild type (WT) was also tested in the presence of 0.25 U/mL heparin (UFH: yellow bars), except for CR22091, which is indicated with an asterisk (∗). Binding responses after 300 seconds were normalized to the binding responses obtained for PF4-WT. H/L, heavy/light; MS, mass spectrometry.

Overview of PF4-specific rAb generation and PF4 binding properties. (A) Schematic overview of rAb generation and characterization. (B) PF4-binding rAbs were measured by ELISA. PF4 was directly coated onto 96-well ELISA plates, and rAbs were tested in serial dilutions starting from 60 μg/mL. Results are expressed as chemiluminescence (LUM). (C) Surface representations of a model of the paratope of CR22046 and of the structure of PF4 showing the electrostatic potentials. Clustered negatively charged residues in CR22046 and clustered positively charged residues in PF4 are labeled with white characters. For the CR22046 rAb, the numbering is according to Kabat. (D) Real-time binding curves as measured by BLI were obtained by dipping streptavidin sensors with immobilized PF4-biotin into wells containing 5 μg/mL of each antibody (Ab) for 900 seconds, followed by a dissociation of 600 seconds in empty buffer (10× kinetic buffer). (E) BLI-binding responses were obtained by dipping anti-human Fc sensors with immobilized rAbs into wells containing 3.1 μg/mL of each PF4 mutant. The binding of anti-PF4 rAbs to PF4–wild type (WT) was also tested in the presence of 0.25 U/mL heparin (UFH: yellow bars), except for CR22091, which is indicated with an asterisk (∗). Binding responses after 300 seconds were normalized to the binding responses obtained for PF4-WT. H/L, heavy/light; MS, mass spectrometry.

Twelve reverse-engineered clonotypic rAbs were derived from full-length aa sequences of anti-PF4 antibody proteomes from 5 patients with VITT.16 Three rAbs expressed poorly in CHO cells and were excluded from further study. The clonality of the remaining 9 rAbs is shown in supplemental Table 1. Eight rAbs from 3 patients with VITT tested positive for PF4 binding in ELISA and/or BLI, validating the methods for reverse cloning of rAbs from the stereotypic PF4-specific proteomes (Figure 1B, D; supplemental Table 2). Only rAb CR22047 tested negative for PF4 binding on both ELISA and BLI. As expected, the interaction between PF4 and rAbs from patients with VITT was strongly inhibited by heparin in contrast to chimeric anti-human PF4 monoclonal antibody KKO (Figure 1E; supplemental Figure 1). Furthermore, F(ab’)2 anti-PF4 rAbs competitively inhibited binding of the IgGs of patients with VITT to PF4 by ELISA (supplemental Figure 2).The lack of complete inhibition may relate to a relatively low blocking capacity of F(ab’)2 and/or suggest a second PF4 epitope in VITT.17

Epitope mapping indicated that residue R22 is critical for the PF4 epitope (Figure 1B, E). K66 and K62 also seem to be part of the epitope but are likely less important for the interaction between PF4 and the rAbs (Figure 1B,E). The impact of K66A was detectable in BLI, but not in ELISA, possibly explained by differences in assay set up (supplemental Information). The impact of K62A was only observed for the least potent PF4-binding rAbs CR22042 and CR22044 in BLI (Figure 1B,E). These findings are consistent with recent studies identifying R22 on PF4 as a key epitope-binding residue recognized by anti-PF4 antibodies from patients with VITT after vaccination with ChAdOx1 nCov-19 and Ad26.COV2.S.13,18

Paratope modeling gave further insight into the molecular interactions between rAbs and the PF4 epitope. All rAb light chains are encoded by the same IGLV3-21∗02 allele, indicating a major role for the λ light chain in mediating PF4 binding of these rAbs.16,19 This allele encodes an acidic motif containing 3 aspartic acids (DDSD) in light chain complementarity–determining region 2 (LCDR2) and another 2 aspartic acids in LCDR3. Clonotypic rAbs positive in BLI and FcγRIIa binding assays contain 1 striking shared mutation, K31E, a positively charged aa to a negatively charged aa in LCDR1. In contrast, the non-PF4 binding CR22047 does not contain the K31E mutation (supplemental Table 1). Molecular modeling of the VL (light chain variable region) and VH (heavy chain variable region) domains of the representative CR22046 clonotype (Figure 1C) revealed that the 5 aspartic acids encoded by the germ line IGLV3.21∗02 are predicted to be close together in a highly negatively charged patch containing 9 acidic residues, including the germ line D100b residue of the shared IGHJ3∗01 segment (supplemental Table 1). Thus, in total, 6 of 9 negatively charged residues in the predicted paratope of CR22046 are germ line encoded. The K31E mutation in LCDR1 and E96 and E100a residues in the HCDR3 region complete the predicted paratope patch (Figure 1C). The exact roles of somatic mutations and HCDR3 motifs await germ line reversion studies; however, it is already apparent that there is a striking charge complementarity between the predicted highly negatively charged paratope, which contains 9 acidic residues in CR22046, and the highly positively charged VITT epitope on PF4, which displays a cluster of 9 positively charged residues (Figure 1C).13

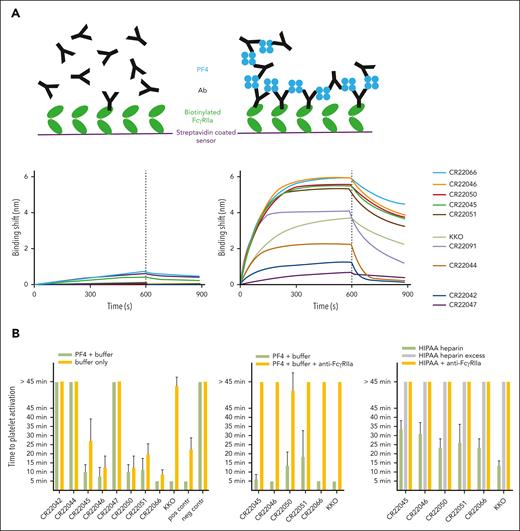

The ability of clonotypic IgG1 anti-PF4 rAbs to form immune complexes with PF4 molecules in solution and to bind immobilized FcγRIIa receptors was assessed by PF4 antibody complex detection assay (Figure 2A). The most potent PF4-binding rAbs derived from patients 2 and 5 with VITT showed higher receptor-binding responses in the presence of PF4 than the less potent rAbs from patient 1 (Figure 2A). The functional ability of these rAbs to activate platelets, in an FcγRIIa-dependent manner, was demonstrated by PF4-induced platelet activation assays, which tested positive for all 5 rAbs from patients 2 and 5 in the absence of heparin (Figure 2B). Although inhibition of rAb binding to PF4 by heparin was similar to earlier studies,13,20 higher concentrations of heparin were required for inhibition of rAb-induced platelet activation compared with a report using PF4 antiserum.20 This may relate to differences in heparin-induced platelet activation assay conditions and/or serum cofactors.

Functionality of PF4-specific rAbs. (A) PF4 antibody (Ab) complex detection assay. Schematic representation showing only minor binding of IgG1 anti-PF4 rAbs to FcγRIIa due to low affinity (top left) and high binding responses of immune complexes formed on the addition of PF4, thereby increasing avidity (top right). BLI assay with immobilized FcγRIIa, which is dipped into wells containing anti-PF4 rAbs without PF4 (bottom left panel) or with PF4 (right panel), followed by a dissociation step in empty buffer. (B) PF4-induced platelet activation assay (PIPAA). PF4 + buffer compared with buffer alone (left), or PF4 + buffer compared with PF4 + buffer + FcγRIIa-blocking monoclonal antibody (middle). Heparin-induced platelet activation assay (right). Heparin (2 U/mL) compared with excess heparin (1000 U/mL) or heparin + FcγRIIa-blocking monoclonal antibody. Each rAb was tested in quadruplicate with 4 different donor platelet suspensions. Each bar represents the mean with SD of the quadruplicate tests. The comparison was performed with platelets from the same donors. The time to platelet activation (aggregation, visual readout every 5 minutes) is displayed. A time of ≤45 minutes is considered positive, and >45 minutes is considered negative. Positive control (pos contr): pooled human sera with known strong positive (5- or 10-minute) results in PIPAA. Negative control (neg contr): inert serum from healthy control with blood group AB.

Functionality of PF4-specific rAbs. (A) PF4 antibody (Ab) complex detection assay. Schematic representation showing only minor binding of IgG1 anti-PF4 rAbs to FcγRIIa due to low affinity (top left) and high binding responses of immune complexes formed on the addition of PF4, thereby increasing avidity (top right). BLI assay with immobilized FcγRIIa, which is dipped into wells containing anti-PF4 rAbs without PF4 (bottom left panel) or with PF4 (right panel), followed by a dissociation step in empty buffer. (B) PF4-induced platelet activation assay (PIPAA). PF4 + buffer compared with buffer alone (left), or PF4 + buffer compared with PF4 + buffer + FcγRIIa-blocking monoclonal antibody (middle). Heparin-induced platelet activation assay (right). Heparin (2 U/mL) compared with excess heparin (1000 U/mL) or heparin + FcγRIIa-blocking monoclonal antibody. Each rAb was tested in quadruplicate with 4 different donor platelet suspensions. Each bar represents the mean with SD of the quadruplicate tests. The comparison was performed with platelets from the same donors. The time to platelet activation (aggregation, visual readout every 5 minutes) is displayed. A time of ≤45 minutes is considered positive, and >45 minutes is considered negative. Positive control (pos contr): pooled human sera with known strong positive (5- or 10-minute) results in PIPAA. Negative control (neg contr): inert serum from healthy control with blood group AB.

In summary, we report a novel reverse-engineering approach to generate anti-PF4 rAbs based on the sequence of anti-PF4 Abs obtained from sera of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19–vaccinated patients with VITT and have used them to identify key PF4-binding residues and model paratope structure. Functional anti-PF4 clonotypes have been generated from 3 of 5 ChAdOx1 nCoV-19–vaccinated patients with VITT, underlining the reliability of the methods to generate clinically relevant rAbs. These rAbs mimic the phenotype of the serum of patients with VITT in their ability to activate platelets strongly in the absence of heparin. This unique suite of rAbs will provide a valuable research tool to investigate the cause of VITT, including the role of potential cofactors, such as spike protein, vaccine components, and potential predisposing host factors.21 In addition, this work could guide to specific VITT diagnostics and therapeutics. To our knowledge, these are the first human rAbs engineered from matched antibody proteomes without resorting to a B-cell receptor database. Although this success might be due to the monoclonal/oligoclonal nature of these antibody responses and may not be applicable to polyclonal responses, this technology holds the promise of generating functional rAbs that mediate pathogenic effects from serum Ig proteomes in infections, autoimmunity, and vaccinations.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Madison Piassek and Daniel Fornwald for the development of expression and purification conditions to produce recombinant PF4 protein.

This study was supported by Flinders Health and Medical Research Institute COVID-19 Research Grant and Flinders Foundation Health Seed Grant.

Authorship

Contribution: J.J.W., M.v.d.N.K., L.R., T.K., R.Z., L.S., and T.P.G. conceptualized the study; M.v.d.N.K., L.R., B.A., C.W.T., T.C., R.B., A.K., P.A., R.K., L.P., M.K., A.S., P.B., E.K., A.P., T.K., and L.S. designed and performed experiments and analyzed data; J.J.W., M.v.d.N.K., L.R., R.B., A.K., T.K., R.Z., L.S., and T.P.G. discussed the results and interpreted the data together with all coauthors; J.J.W. and T.P.G. wrote the first draft of the manuscript with contributions from M.v.d.N.K., L.R., R.B., A.K., T.K., R.Z., and L.S.; and all authors participated in data collection and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.v.d.N.K., L.R., R.B., A.K., P.A., A.S., P.B., E.K., A.P., T.K., R.Z., and L.S. were employees of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson at the time of the study and may have ownership of shares in Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jing Jing Wang, Department of Immunology, College of Medicine and Public Health, Flinders University, Flinders Dr, Bedford Park, Adelaide, SA 5042, Australia; email: jingjing.wang@flinders.edu.au.

References

Author notes

Amino acid sequences of anti–platelet factor 4 antibodies are available on request from the corresponding author (jingjing.wang@flinders.edu.au).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal