Key Points

IDH1 promotes leukemogenesis in vivo in cooperation with HoxA9.

Pharmacologic inhibition of mutant IDH1 efficiently inhibits AML cells of IDH1-mutated patients but not of normal CD34+ bone marrow cells.

Abstract

Mutations in the metabolic enzymes isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) and 2 (IDH2) are frequently found in glioma, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), melanoma, thyroid cancer, and chondrosarcoma patients. Mutant IDH produces 2-hydroxyglutarate (2HG), which induces histone- and DNA-hypermethylation through inhibition of epigenetic regulators. We investigated the role of mutant IDH1 using the mouse transplantation assay. Mutant IDH1 alone did not transform hematopoietic cells during 5 months of observation. However, mutant IDH1 greatly accelerated onset of myeloproliferative disease–like myeloid leukemia in mice in cooperation with HoxA9 with a mean latency of 83 days compared with cells expressing HoxA9 and wild-type IDH1 or a control vector (167 and 210 days, respectively, P = .001). Mutant IDH1 accelerated cell-cycle transition through repression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors Cdkn2a and Cdkn2b, and activated mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. By computational screening, we identified an inhibitor of mutant IDH1, which inhibited mutant IDH1 cells and lowered 2HG levels in vitro, and efficiently blocked colony formation of AML cells from IDH1-mutated patients but not of normal CD34+ bone marrow cells. These data demonstrate that mutant IDH1 has oncogenic activity in vivo and suggest that it is a promising therapeutic target in human AML cells.

Introduction

Mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) and IDH2 were originally identified in glioma,1,2 acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myeloproliferative neoplasm, and myelodysplastic (MDS) syndrome patients3-5 but are increasingly found in a diverse set of other tumor entities such as chondrosarcoma,6 lymphoma,7 melanoma,8 and thyroid cancer.9 In cytogenetically normal AML, mutated IDH1 is found in 10.9% of patients,10 whereas mutated IDH2 is found in 12.1%.11 Mutations in IDH1 are almost exclusively found at amino acid arginine 132,12 and IDH2 mutations are found more frequently at position R140 and less frequently at position R172.13 All mutations affect the active site of the enzymes where isocitrate and reduced NAD phosphate bind.14-16 Whereas the enzymatic function of mutant IDH to convert isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate is impaired, it gains a neomorphic function to convert α-ketoglutarate to R-2-hydroxyglutarate (R-2HG, also known as D-2HG).14-16

Genome-wide methylation studies revealed a strong association of mutant IDH1 with an increased number of methylated cytosine guanine dinucleotide (CpGs).17 Similarly, AML patients with mutant TET2 showed a higher number of methylated CpGs, whereas IDH and TET2 mutations almost never occur in the same patient.17 This observation led to the hypothesis that mutant IDH inhibits TET2 function, thus leading to increased DNA methylation and leukemia.17 Indeed, the metabolite 2HG was shown to inhibit the function of TET2, resulting in DNA hypermethylation.18 Many other α-ketoglutarate–dependent dioxygenases and histone demethylases are competitively blocked by 2HG.17-21 Interestingly, a recent study showed that R-2HG, but not S-2-hydroxyglutarate (S-2HG), promotes cytokine independence of a leukemia cell line through activation of the EglN1 prolyl hydroxylase.19,22

Several studies suggested that mutant IDH1 and specifically 2HG block myeloid and adipocyte differentiation.17,20 The biological function of mutant IDH1 has been recently studied in a knock-in mouse model, demonstrating an increase in the number of hematopoietic progenitor cells and increased cell proliferation and splenomegaly.23 Mutant mice did not develop leukemia and had a similar survival as wild-type mice, suggesting that mutant IDH1 alone is not sufficient to induce leukemia.23 Potentially collaborating genes in AML patients are mutant NPM1 and FLT3; these mutations frequently co-occur with mutant IDH.24 Xu et al demonstrated that expression of HoxA genes was increased in IDH1 mutated cells.18

To identify potentially collaborating partners of mutant IDH1, we investigated the ability of other oncogenes to collaborate with mutant IDH1 in leukemogenesis.

Materials and methods

More information on materials and methods can be found in the supplemental information on the Blood website.

Retroviral vectors and vector production

Retroviral vectors MSCV-PGKneo,25 MSCV-HoxA9-PGKneo,25 and pSF91-IRES-eGFP26 have been described previously. pSF91-IRES-eGFP has been modified for Gateway cloning by inserting the RfA cassette (Invitrogen-Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) as described.27 The 1.2-kb coding region of human IDH1 was amplified by nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from complementary DNA of bone marrow cells from an MDS syndrome patient with a heterozygous IDH1R132C mutation. Helper-free recombinant retrovirus produced in supernatants of transfected ecotropic Phoenix packaging cell line was used to transduce the ecotropic GP+E86 packaging cell line.28

Mice and retroviral infection of primary bone marrow cells

Six- to 8-week-old female C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany, and kept in pathogen-free conditions at the central animal laboratory of Hannover Medical School. All animal experiments were approved by the Lower Saxony state office for consumer protection, Oldenburg, Germany. Primary mouse bone marrow cells were transduced as previously described.29

Bone marrow transplantation and monitoring of mice

Equal numbers of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing, sorted bone marrow cells from C57BL/6J mice were injected intravenously in lethally irradiated syngeneic recipient mice that were irradiated with 800 cGy, accompanied by a life-sparing dose of 1 × 105 freshly isolated bone marrow cells from syngeneic mice. Donor chimerism was monitored by tail vein bleeds and fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of GFP-expressing cells every 4 weeks as previously described.30 Blood counts with differential white blood cell analysis were performed using an ABC Vet Automated Blood counter (Scil animal care company GmbH, Viernheim, Germany). Lineage distribution was determined by FACS analysis (FACS Calibur; Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) as previously described.29

Clonogenic progenitor assay

Colony-forming cell (CFC) units were assayed in methylcellulose (Methocult M3234; StemCell Technologies, Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada) as described in supplemental Methods.

Patient samples and CD34+ cells

Diagnostic bone marrow or peripheral blood samples were analyzed from 400 adult patients (16-60 years) with de novo or secondary AML (FAB M0-M2, M4-M7) who had entered the multicenter treatment trial AML-SHG 01/99 or 02/95 for mutations in IDH1 as previously described.10 The association of IDH1 mutations with expression levels of HOXA and HOXB cluster genes in adult AML patients up to 60 years of age were studied in 457 patients of the Hemato-Oncology Cooperative study group.31 The association of IDH1 mutations with HOXA9 was studied in an independent cohort.32 In brief, HG-U133-plus2 microarray data of 197 AML patients were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas Data Portal (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/).32 The normalized intensity signals of the 2 HOXA9-specific probes were extracted and log2 transformed. Bone marrow of healthy donors was obtained from the transplantation unit of Hannover Medical School. CD34+ cells were isolated using the CD34 microbead kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) per the manufacturer’s protocol. Written informed consent was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the institutional review board of Hannover Medical School.

2-hydroxyglutarate measurement

To determine intracellular R- and S-2HG levels, 5-10 million cells were sonicated for 10 minutes at intervals of 30 seconds on, 30 seconds off at 4°C using the Bioruptor (Diagenode, Liege, Belgium) followed by 2 rounds of freeze–thaw cycles. All analyses were performed on an AB Sciex 4000 Q-trap triple quadruple mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). Liquid chromatography was performed on an Xterra C18 analytical column (150 × 3.9 mm [inner diameter]; 5-μm bead size) with water–acetonitrile (96.5:3.5 by volume) containing 125 mg/L ammonium formate (pH adjusted to 3.6 by addition of formic acid) as mobile phase as described.33

Cell-cycle analysis in vitro and in vivo

For cell-cycle analysis, mice were injected intraperitoneally (IP) with 100 µL 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (1 mM) at 36, 24, and 12 hours before harvest. For in vitro labeling, 10 µM of BrdU was added to 1 million cells for 6 hours. Cell-cycle analysis was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Pharmingen, catalog no. 557892).

Apoptosis measurement

Cells were stained with Annexin V-APC and 7AAD according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Pharmingen; catalog no. 550474).

Immunoblotting

Cellular lysates were prepared and immunoblotting was performed as described previously.34 Antibodies and methods are described in the supplemental Methods.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed as previously described.35 Quantitative reverse-transcriptase (RT)-PCR was done as previously described using SYBR green (Invitrogen) for quantification of double-stranded DNA on a StepOne Plus cycler (Applied Biosystems).36 Relative expression was determined with the 2−ΔΔCT method,37 and the housekeeping gene transcript Abl1 was used to normalize the results.

Methylation analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from cells using the Allprep DNA RNA kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). One µg of genomic DNA was bisulfite converted with the EZ DNA Methylation kit (Zymo Research, Freiburg, Germany). A PCR amplification of 50-100 ng equivalent of the starting amount of converted DNA was performed with C to T conversion-specific primers, cloned in pCR2.1-TOPO sequencing vector (Invitrogen), and sequenced by Sanger sequencing.

Gene expression profiling

GFP+ cells were sorted from mouse bone marrow cells 4 weeks after transplantation and were hybridized to an identical lot of Affymetrix GeneChips. Further details are described in the supplemental Methods. Gene expression profiling data can be found at the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE45019).

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

Cells were plated at a density of 5 × 104 cells/mL in flat bottom 96-well plates (100 µL/well) and incubated under light protective conditions. The drugs were added to the culture medium at the specified concentrations. After 64 hours, 10 µL alamarBlue (Abd Serotec, Raleigh, NC) was added per well. Fluorescence intensity was measured after 72 hours on a microplate reader (Safire; Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). All experiments were performed in duplicate with 3 independently transduced cell lines.

H2O2 measurement

The measurement of hydrogen peroxide was carried out using the Amplex-red hydrogen peroxide/peroxidase assay kit as described by the manufacturer (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany).

Computational screening

Statistical analysis

Pairwise comparisons were performed by Student t test for continuous variables and by χ-squared test for categorical variables. The 2-sided level of significance was set at P < .05. Comparison of survival curves were performed using the log-rank test. A binary logistic regression model was used to analyze associations between mutation status of IDH1, NPM1, FLT3, CEBPA, and expression levels HOXA9. Statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Munich, Germany), GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), or SPSS 20.0 (IBM Deutschland, Ehningen, Germany). Graphical representation was prepared using Adobe Illustrator CS5.1 (Adobe Systems GmbH, Munich, Germany).

Results

Mutant IDH1 induces a myeloproliferative-like disease in immortalized bone marrow cells

To test whether mutant IDH1 induces a myeloid malignancy, we cloned IDH1wt and IDH1mut from a patient with MDS syndrome and transduced control (CTL), IDH1wt, or IDH1mut constructs in 5-fluorouracil pretreated bone marrow cells. The cumulative CFC yield from sorted transgene positive cells was not increased and the cells stopped proliferating after the second replating (Figure 1A).

Effect of constitutive expression of mutated IDH1 in primary bone marrow cells in vitro and in vivo. (A) Cumulative CFC yield is shown for an initial plating of 1000 transgene-expressing cells (cells were sorted before plating; mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments). (B) Protein expression of mouse bone marrow cells transduced with a CTL vector or with FLAG-tagged wild-type IDH1 or mutant IDH1 using an anti-FLAG antibody. Cells were harvested from bone marrow 4 weeks after transplantation. β-actin was probed on the same blot as a loading control. (C) Ratio of R-2HG to S-2HG in mouse bone marrow cells transduced with CTL vector or with wild-type or mutant IDH1. Cells were harvested from bone marrow 4 weeks after transplantation (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] of 3 independent mice). (D) Engraftment of transduced cells in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of 1 × 105 transgene-positive cells (mean ± SEM). (E) White blood cell count in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells (mean ± SEM). (F) Hemoglobin levels in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells (mean ± SEM). (G) Platelet count in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells (mean ± SEM). (H) Immunophenotype of transduced cells in peripheral blood at 16 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM). (I) Average spleen weight in mice receiving transplants of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells 20 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM). *P < .05; **P < .01; ns, not significant. WB, western blot.

Effect of constitutive expression of mutated IDH1 in primary bone marrow cells in vitro and in vivo. (A) Cumulative CFC yield is shown for an initial plating of 1000 transgene-expressing cells (cells were sorted before plating; mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments). (B) Protein expression of mouse bone marrow cells transduced with a CTL vector or with FLAG-tagged wild-type IDH1 or mutant IDH1 using an anti-FLAG antibody. Cells were harvested from bone marrow 4 weeks after transplantation. β-actin was probed on the same blot as a loading control. (C) Ratio of R-2HG to S-2HG in mouse bone marrow cells transduced with CTL vector or with wild-type or mutant IDH1. Cells were harvested from bone marrow 4 weeks after transplantation (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] of 3 independent mice). (D) Engraftment of transduced cells in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of 1 × 105 transgene-positive cells (mean ± SEM). (E) White blood cell count in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells (mean ± SEM). (F) Hemoglobin levels in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells (mean ± SEM). (G) Platelet count in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells (mean ± SEM). (H) Immunophenotype of transduced cells in peripheral blood at 16 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM). (I) Average spleen weight in mice receiving transplants of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells 20 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM). *P < .05; **P < .01; ns, not significant. WB, western blot.

We transduced 5-fluorouracil pretreated bone marrow cells with CTL, wild-type, and mutant IDH1 constructs and confirmed transgene expression in bone marrow cells 4 weeks after transplantation (Figure 1B). A high ratio of R-2HG to S-2HG was observed in bone marrow cell lysates from IDH1mut transduced cells compared with IDH1wt , or control cells (Figure 1C). In vivo, when transplanting equal numbers of transgene-positive cells, engraftment in peripheral blood was stable over time (Figure 1D), and complete blood counts (Figure 1E-G), immunophenotype of GFP+ cells in peripheral blood (Figure 1H), and spleen weight at 20 weeks after transplantation (Figure 1I) were similar between CTL, IDH1wt, and IDH1mut mice, suggesting that retrovirally expressed mutant IDH1 alone is insufficient to induce myeloproliferation.

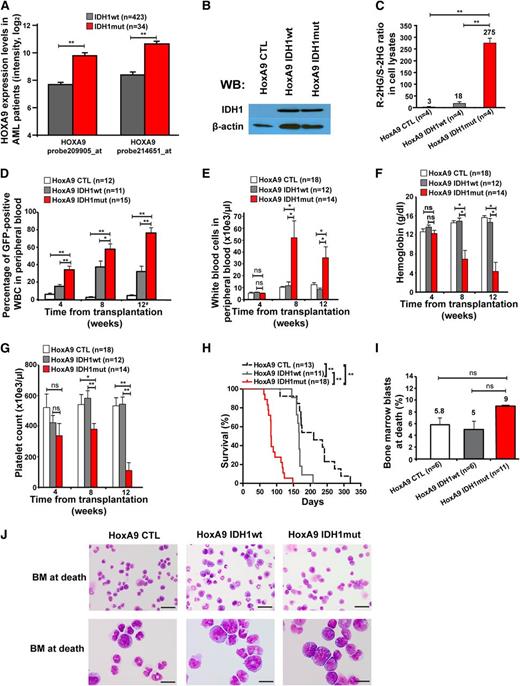

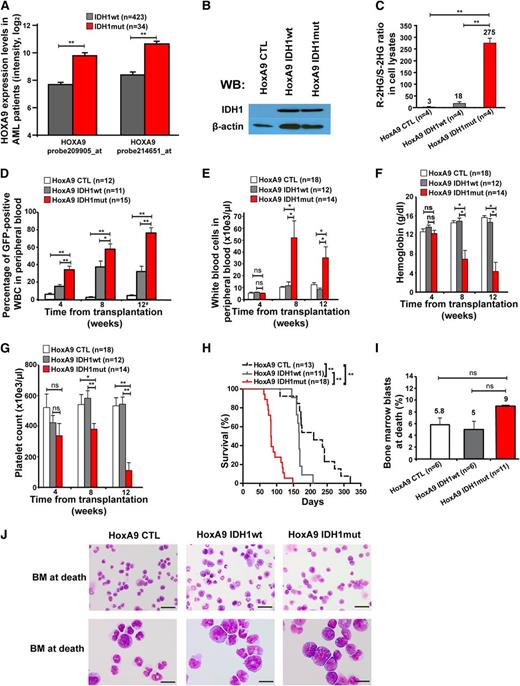

To identify other potentially collaborating genes, we compared gene expression levels of known oncogenes between IDH1wt and IDH1mut AML patients. Eight of 11 HOXA cluster genes and 6 of 10 HOXB cluster genes were significantly higher expressed in IDH1 mutant than in wild-type patients (supplemental Figure 1A-B). Overexpression of HOXA9 in IDH1mut patients was confirmed in an independent patient cohort (supplemental Figure 2). HOXA9 was independently overexpressed in IDH1 mutant patients in multivariate analysis including NPM1, FLT3-ITD, and CEBPA mutation status (supplemental Table 1). Because HOXA9 was most differentially expressed between mutant and wild-type IDH1 patients (Figure 2A), and constitutive HOXA9 expression induces a long-latency myeloproliferative disease (MPD) in mice,25,40 we transduced HoxA9-immortalized bone marrow cells with CTL, wild-type, and mutant IDH1 constructs for in vivo evaluation of their leukemogenic potential (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 3A-B). A high ratio of R-2HG to S-2HG in cell lysates from IDH1mut-transduced cells compared with IDH1 wild-type or control cells confirmed the integrity of our model (Figure 2C).

Mutant IDH1 induces a myeloproliferative-like disease in immortalized bone marrow cells. (A) Association of IDH1 mutations with expression levels of HOXA9 in adult AML patients up to 60 years of age (n = 457). Normalized expression levels of HOXA9 are shown for patients with wild-type IDH1 (gray bars) and mutant IDH1 (red bars), which were determined on an Affymetrix microarray with 2 different probes.31 (B) Protein expression of HoxA9-immortalized cells transduced with a CTL vector or with FLAG-tagged wild-type IDH1 or mutant IDH1 using an anti-FLAG antibody. β-actin was probed on the same blot as a loading control. (C) Ratio of R-2HG to S-2HG in cultured HoxA9 cells transduced with CTL, IDH1wt, or IDH1mut (mean ± SEM of 4 independently transduced cell lines). (D) Engraftment of transduced cells in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of 1 × 106 transgene-positive cells (mean ± SEM of the indicated number of mice). #For mice that died before week 12, engraftment in peripheral blood is shown for the time point of death. (E) White blood cell count in peripheral blood from mice that received transplants of cells transduced with the indicated constructs. Blood was taken 4, 8, and 12 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM of the indicated number of mice). (F) Hemoglobin level in peripheral blood from mice that received transplants of cells transduced with the indicated constructs. Blood was taken 4, 8, and 12 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM of the indicated number of mice). (G) Platelet counts in peripheral blood from mice that received transplants of cells transduced with the indicated constructs. Blood was taken 4, 8, and 12 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM of the indicated number of mice). (H) Survival of mice that received transplants of cells transduced with the indicated constructs. Results from 3 independent experiments using independently transduced cells are shown. (I) Percentage of blast cells in bone marrow of moribund mice (mean ± SEM of the indicated number of mice). (J) Representative Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospin preparations of bone marrow cells from moribund mice (Scale bar: 25 µm in the upper panel; Scale bar: 10 µm in the lower panel). *P < .05; **P < .01; ns, not significant.

Mutant IDH1 induces a myeloproliferative-like disease in immortalized bone marrow cells. (A) Association of IDH1 mutations with expression levels of HOXA9 in adult AML patients up to 60 years of age (n = 457). Normalized expression levels of HOXA9 are shown for patients with wild-type IDH1 (gray bars) and mutant IDH1 (red bars), which were determined on an Affymetrix microarray with 2 different probes.31 (B) Protein expression of HoxA9-immortalized cells transduced with a CTL vector or with FLAG-tagged wild-type IDH1 or mutant IDH1 using an anti-FLAG antibody. β-actin was probed on the same blot as a loading control. (C) Ratio of R-2HG to S-2HG in cultured HoxA9 cells transduced with CTL, IDH1wt, or IDH1mut (mean ± SEM of 4 independently transduced cell lines). (D) Engraftment of transduced cells in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of 1 × 106 transgene-positive cells (mean ± SEM of the indicated number of mice). #For mice that died before week 12, engraftment in peripheral blood is shown for the time point of death. (E) White blood cell count in peripheral blood from mice that received transplants of cells transduced with the indicated constructs. Blood was taken 4, 8, and 12 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM of the indicated number of mice). (F) Hemoglobin level in peripheral blood from mice that received transplants of cells transduced with the indicated constructs. Blood was taken 4, 8, and 12 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM of the indicated number of mice). (G) Platelet counts in peripheral blood from mice that received transplants of cells transduced with the indicated constructs. Blood was taken 4, 8, and 12 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM of the indicated number of mice). (H) Survival of mice that received transplants of cells transduced with the indicated constructs. Results from 3 independent experiments using independently transduced cells are shown. (I) Percentage of blast cells in bone marrow of moribund mice (mean ± SEM of the indicated number of mice). (J) Representative Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospin preparations of bone marrow cells from moribund mice (Scale bar: 25 µm in the upper panel; Scale bar: 10 µm in the lower panel). *P < .05; **P < .01; ns, not significant.

Equal numbers of sorted, GFP+ cells were injected in lethally irradiated mice with a life-sparing dose of helper cells. Engraftment of GFP+ cells in peripheral blood was higher in IDH1mut-transduced cells at 4, 8, and 12 weeks after transplantation compared with IDH1wt or CTL-transduced cells (Figure 2D). Mice receiving transplants with IDH1-mutated cells developed severe leukocytosis, anemia, and thrombocytopenia after week 4 of transplantation, whereas blood counts in control mice remained normal (Figure 2E-G). Interestingly, IDH1mut mice died with a median latency of 83 days after transplantation, whereas IDH1wt and CTL mice died significantly later (167 and 210 days after transplantation, respectively; IDH1mut vs IDH1wt, P < .001; IDH1mut vs CTL, P < .001; Figure 2H).

At time of death, the majority of bone marrow cells were derived from IDH1- or CTL-transduced (GFP+) cells (supplemental Figure 4A-B). Transduced cells in bone marrow and spleen had a myeloid phenotype predominantly expressing the myeloid marker CD11b and 20% to 30% expressing the progenitor cell marker cKit (supplemental Figure 4C-D). Morphologic evaluation of bone marrow from moribund mice showed that the majority of bone marrow cells had monocytic morphology with an increased proportion of immature cells and slightly more blasts in IDH1mut than in wild-type or CTL mice (Figure 2I-J). Bone marrow cells from moribund mice were readily transplantable into secondary animals with a shorter median survival of IDH1mut compared with IDH1wt mice (supplemental Figure 5). At 2 months after transplantation, no significant difference was observed in GFP+lin−ckit+Sca+ and GFP+lin−ckit+Sca+CD34− stem and progenitor cells from IDH1wt or IDH1mut mice (supplemental Figure 6A-B). Southern blot analysis confirmed full proviral integration for each retroviral construct and showed an oligoclonal disease for IDH1mut mice and a monoclonal pattern for IDH1wt mice (supplemental Figure 7). Thus, mutant IDH1 induced a short-latency MPD-like myeloid leukemia in HoxA9-immortalized bone marrow cells, demonstrating its oncogenic potential in vivo.

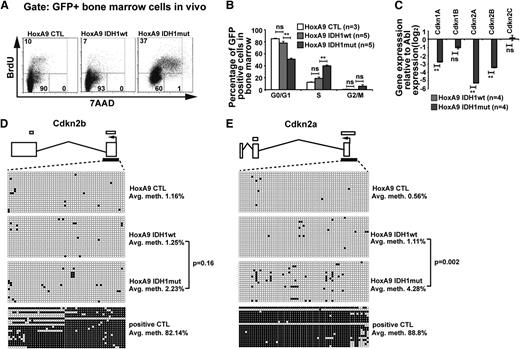

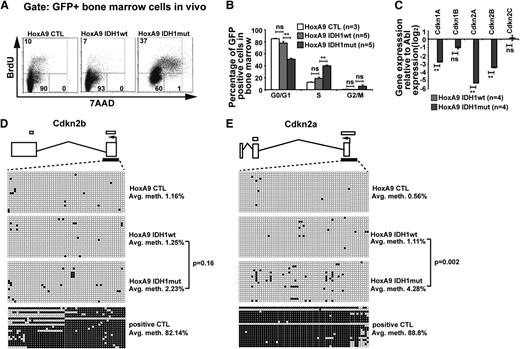

Mutant IDH1 promotes cell-cycle transition

To assess the biologic effect of mutant IDH1, we compared cell-cycle phases and rate of apoptosis in mutant and wild-type IDH1 cells. Analyzing GFP+ bone marrow cells from mice at 9 weeks after transplantation, the rate of apoptosis did not differ between mutated or wild-type IDH1 or CTL transduced cells and was similar to the rate of apoptosis in GFP− cells (supplemental Figure 8A). However, the proportion of cells in S/G2/M phases was significantly higher in bone marrow cells transduced with IDH1mut when compared with cells transduced with IDH1wt or CTL (Figure 3A). The quantitative cell-cycle differences for the HoxA9 immortalized mouse bone marrow cells transduced with CTL, IDH1wt, and IDH1mut cells in vivo are summarized in Figure 3B and in vitro in supplemental Figure 8B.

Mutant IDH1 promotes cell-cycle transition independently of 2-hydroxyglutarate. (A) Representative FACS blots of cell-cycle phases in HoxA9-immortalized vector CTL, IDH1wt, or IDH1mut transduced (GFP+) bone marrow cells 9 weeks after transplantation (BrdU injections IP at 36, 24, and 12 hours before harvest). Cell-cycle phases were determined by analysis of BrdU/7AAD-stained cells by FACS. The upper quadrant represents cells in S phase; the lower left quadrant represents cells in G0/G1 phase; and the lower right quadrant represents cells in G2/M phase of the cell cycle. (B) Cell-cycle distribution in HoxA9-immortalized vector CTL, IDH1wt, and IDH1mut transduced (GFP+) bone marrow cells 9 weeks after transplantation (BrdU injections IP at 36, 24, and 12 hours before harvest). Cell-cycle phases were determined by analysis of BrdU/7AAD-stained cells by FACS (mean ± SEM). (C) Gene expression levels of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in in vitro–cultured HoxA9 cells transduced with IDH1wt and IDH1mut. Gene expression was determined by RT-PCR relative to the housekeeping gene Abl and was normalized to gene expression in IDH1wt cells (mean ± SEM). (D) Methylation analysis of the CpG island in the Cdkn2b (p15) promoter in Hoxa9 cells transduced with IDH1wt and IDH1mut. DNA from in vitro–cultured cells was extracted and bisulfite treated. CpG methyltransferase-treated DNA from IDH1mut cells served as a positive control. The p15 promoter CpG was amplified and subcloned. Twenty clones were sequenced per cell type. Exons are represented by vertical rectangles. White horizontal bars above the exons show CpG islands; black horizontal bars below the exons show the tested region. An open circle indicates a nonmethylated CpG; a black circle indicates a methylated CpG. The percent methylation of the CpG island is calculated by the proportion of methylated CpGs from all investigated CpGs. (E) Methylation analysis of the CpG island in the Cdkn2a (p16) promoter in Hoxa9 cells transduced with IDH1wt and IDH1mut. The analysis was performed as described in the Figure 3D legend. *P < .05; **P < .01; ns, not significant.

Mutant IDH1 promotes cell-cycle transition independently of 2-hydroxyglutarate. (A) Representative FACS blots of cell-cycle phases in HoxA9-immortalized vector CTL, IDH1wt, or IDH1mut transduced (GFP+) bone marrow cells 9 weeks after transplantation (BrdU injections IP at 36, 24, and 12 hours before harvest). Cell-cycle phases were determined by analysis of BrdU/7AAD-stained cells by FACS. The upper quadrant represents cells in S phase; the lower left quadrant represents cells in G0/G1 phase; and the lower right quadrant represents cells in G2/M phase of the cell cycle. (B) Cell-cycle distribution in HoxA9-immortalized vector CTL, IDH1wt, and IDH1mut transduced (GFP+) bone marrow cells 9 weeks after transplantation (BrdU injections IP at 36, 24, and 12 hours before harvest). Cell-cycle phases were determined by analysis of BrdU/7AAD-stained cells by FACS (mean ± SEM). (C) Gene expression levels of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in in vitro–cultured HoxA9 cells transduced with IDH1wt and IDH1mut. Gene expression was determined by RT-PCR relative to the housekeeping gene Abl and was normalized to gene expression in IDH1wt cells (mean ± SEM). (D) Methylation analysis of the CpG island in the Cdkn2b (p15) promoter in Hoxa9 cells transduced with IDH1wt and IDH1mut. DNA from in vitro–cultured cells was extracted and bisulfite treated. CpG methyltransferase-treated DNA from IDH1mut cells served as a positive control. The p15 promoter CpG was amplified and subcloned. Twenty clones were sequenced per cell type. Exons are represented by vertical rectangles. White horizontal bars above the exons show CpG islands; black horizontal bars below the exons show the tested region. An open circle indicates a nonmethylated CpG; a black circle indicates a methylated CpG. The percent methylation of the CpG island is calculated by the proportion of methylated CpGs from all investigated CpGs. (E) Methylation analysis of the CpG island in the Cdkn2a (p16) promoter in Hoxa9 cells transduced with IDH1wt and IDH1mut. The analysis was performed as described in the Figure 3D legend. *P < .05; **P < .01; ns, not significant.

Gene expression profiles suggested that cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors were among the most downregulated genes in IDH1mut cells. We quantified gene expression levels of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (Cdkn) 1a (p21), 1b (p27), 2a (p16), and 2b (p15) and found them markedly downregulated in IDH1mut when compared with IDH1wt cells (Figure 3C), providing an explanation for the enhanced cell proliferation in IDH1mut cells. 2HG was previously shown to induce DNA hypermethylation,17 and silencing of CDKN2A and CDKN2B expression by promoter hypermethylation has previously been reported in AML.41 To assess whether Cdkn2a and Cdkn2b expression was downregulated by promoter methylation in our model, we quantified methylated promoter CpGs by sequencing alleles of bisulfite converted DNA. The CpG island in the promoter of Cdkn2b showed low levels of DNA methylation in IDH1wt, IDH1mut, and CTL cells (Figure 3D). The CpG islands in the promoter of Cdkn2a showed low levels of DNA methylation in IDH1wt and CTL cells, whereas IDH1mut cells had slightly increased levels of DNA methylation (Figure 3E). These data suggest that mutated IDH1 enhances cell proliferation through reduced expression of CDK inhibitors; however, transcriptional repression rather than gene silencing by promoter methylation seems to be the mechanism for low expression of CDK inhibitors.

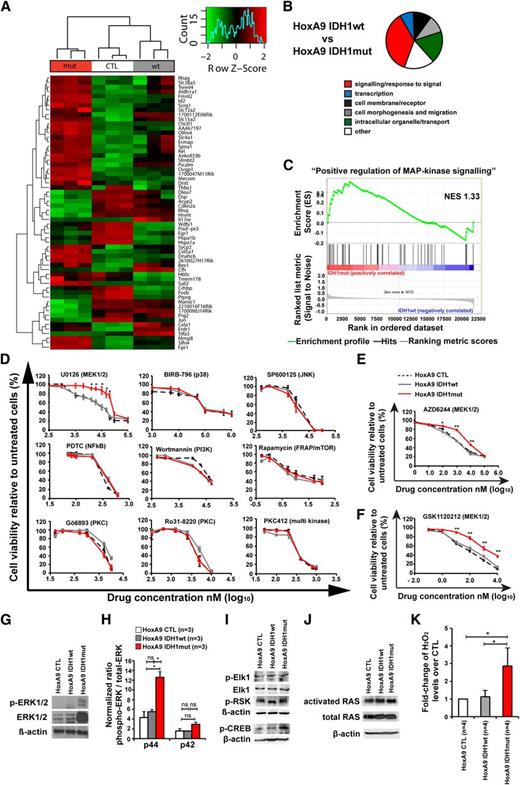

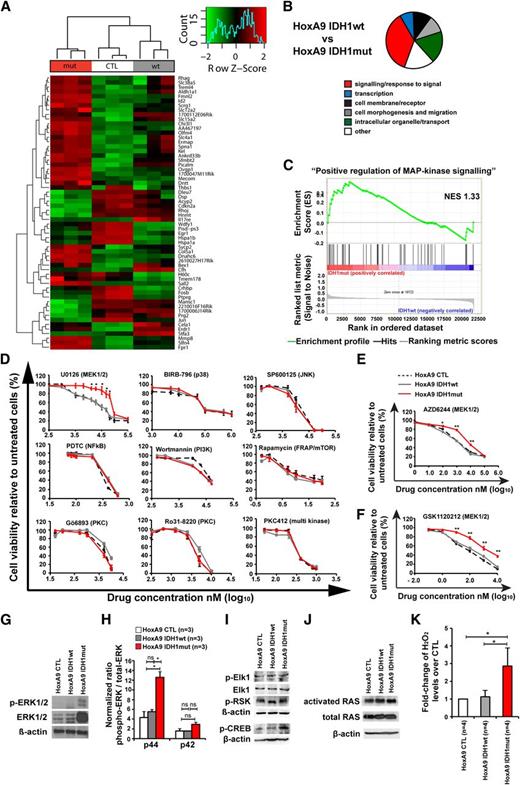

Mutant IDH1 activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling

To identify pathways that are dysregulated by mutant IDH1, we performed gene expression profiling with cells transduced with HoxA9 and CTL, IDH1wt, or IDH1mut. GFP-expressing cells were harvested from bone marrow 4 weeks after transplantation. In unsupervised hierarchical clustering, mutated cells clustered together and separated from IDH1wt or CTL cells (Figure 4A). Differentially expressed genes are listed in supplemental Table 2. We next performed gene set enrichment analysis using the gene sets from gene ontology. Most gene sets were related to membrane receptors, signaling, intracellular organelles and transport, and cell morphogenesis and migration, several of which characterize monocytic function (Figure 4B; supplemental Table 3).

Mutant IDH1 activates MAPK signaling. (A) Row-scaled unsupervised hierarchical clustering of cells transduced with HoxA9 and CTL, IDH1wt, or IDH1mut. Three cell lines per group were generated by independent transductions of bone marrow cells and were transplanted in 1 lethally irradiated mouse each. The cells were harvested from bone marrow 4 weeks after transplantation and were sorted for GFP expression. Gene expression profiling using RNA from sorted cells was performed on Affymetrix Mouse 430.2 arrays. After robust multi-array average normalization, unsupervised hierarchical clustering was performed on variance filtered genes based on a log2 interquartile range of 1.6. (B) Graphical representation of enriched categories of gene ontology gene sets for the indicated cell comparisons based on gene set enrichment analysis from gene chip arrays. (C) Enrichment plot for the gene set “positive regulation of MAPK signaling” comparing IDH1mut and IDH1wt cells. NES, normalized enrichment score. (D) In vitro cytotoxicity assays using inhibitors of signaling pathways in HoxA9 cells transduced with CTL, IDH1wt, or IDH1mut (mean ± SEM of 3-5 independent experiments performed in duplicate). (E) In vitro cytotoxicity assay using AZD6244, an inhibitor of MEK1/2 in HoxA9 cells transduced with CTL, IDH1wt, or IDH1mut (mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate). (F) In vitro cytotoxicity assay using GSK1120212, an inhibitor of MEK1/2 in HoxA9 cells transduced with CTL, IDH1wt, or IDH1mut (mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate). (G) Representative western blot of in vitro–cultured cells for the indicated cell lines using antibodies against ERK, phospho-ERK, and β-actin as a loading control. (H) Ratio of phospho-p44 ERK/total-p44 ERK and phospho-p42 ERK/total-p42 ERK in HoxA9 CTL, HoxA9 IDH1wt, and HoxA9 IDH1mut cells (mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments). (I) Representative western blot of in vitro–cultured cells for the indicated cell lines using antibodies against phospho-Elk1, total Elk1, phospho-p90RSK (Ser380), phospho-CREB, and β-actin as loading control. (J) Representative western blot of in vitro–cultured cells for the indicated cell lines using antibodies against activated RAS, total RAS, and β-actin, as loading control. (K) Hydrogen peroxide levels in cultured cells of the indicated cells that were incubated with Amplex red reaction mixture for 16 hours (mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments measured in triplicate). *P < .05; ns, not significant.

Mutant IDH1 activates MAPK signaling. (A) Row-scaled unsupervised hierarchical clustering of cells transduced with HoxA9 and CTL, IDH1wt, or IDH1mut. Three cell lines per group were generated by independent transductions of bone marrow cells and were transplanted in 1 lethally irradiated mouse each. The cells were harvested from bone marrow 4 weeks after transplantation and were sorted for GFP expression. Gene expression profiling using RNA from sorted cells was performed on Affymetrix Mouse 430.2 arrays. After robust multi-array average normalization, unsupervised hierarchical clustering was performed on variance filtered genes based on a log2 interquartile range of 1.6. (B) Graphical representation of enriched categories of gene ontology gene sets for the indicated cell comparisons based on gene set enrichment analysis from gene chip arrays. (C) Enrichment plot for the gene set “positive regulation of MAPK signaling” comparing IDH1mut and IDH1wt cells. NES, normalized enrichment score. (D) In vitro cytotoxicity assays using inhibitors of signaling pathways in HoxA9 cells transduced with CTL, IDH1wt, or IDH1mut (mean ± SEM of 3-5 independent experiments performed in duplicate). (E) In vitro cytotoxicity assay using AZD6244, an inhibitor of MEK1/2 in HoxA9 cells transduced with CTL, IDH1wt, or IDH1mut (mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate). (F) In vitro cytotoxicity assay using GSK1120212, an inhibitor of MEK1/2 in HoxA9 cells transduced with CTL, IDH1wt, or IDH1mut (mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate). (G) Representative western blot of in vitro–cultured cells for the indicated cell lines using antibodies against ERK, phospho-ERK, and β-actin as a loading control. (H) Ratio of phospho-p44 ERK/total-p44 ERK and phospho-p42 ERK/total-p42 ERK in HoxA9 CTL, HoxA9 IDH1wt, and HoxA9 IDH1mut cells (mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments). (I) Representative western blot of in vitro–cultured cells for the indicated cell lines using antibodies against phospho-Elk1, total Elk1, phospho-p90RSK (Ser380), phospho-CREB, and β-actin as loading control. (J) Representative western blot of in vitro–cultured cells for the indicated cell lines using antibodies against activated RAS, total RAS, and β-actin, as loading control. (K) Hydrogen peroxide levels in cultured cells of the indicated cells that were incubated with Amplex red reaction mixture for 16 hours (mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments measured in triplicate). *P < .05; ns, not significant.

Genes related to MAPK signaling were highly enriched in IDH1 mutant cells (Figure 4C, P < .001; supplemental Table 3). To identify whether mutated IDH1 perturbs intracellular signaling as indicated by gene set enrichment analysis, we determined the inhibitory effect of 15 drugs that block a specific signaling pathway. IDH1mut cells were resistant to inhibition with the MEK1/2 inhibitor UO126, which inhibits MAPK signaling, whereas inhibition of JNK, p38, NFkB, PI3-kinase, mTOR, PKC, PLC, PKA-CREB, GSK3β, HIF1-α, Hexokinase, and c-Met was similarly effective in IDH1mut, IDH1wt, and CTL cells (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 9). Further, IDH1mut cells were also resistant to MEK1/2 inhibitors AZD6244 and GSK 1120212 (Figure 4E-F). Protein levels of ERK and phospho-ERK, and specifically the ratio of phospho-p44/total-p44 were highly upregulated in HoxA9 IDH1mut cells when compared with HoxA9 IDH1wt and HoxA9 CTL cells demonstrating MAPK activation on the protein level (Figure 4G-H; supplemental Figure 10). We also evaluated the effect of mutant IDH1 on ERK in bone marrow cells that do not overexpress HOXA9. Transduced cells were transplanted and sorted from bone marrow after 8 weeks. Total ERK was not increased in mutant IDH1 cells. However, the ratio of phospho-ERK to total ERK was higher by trend (P = .05) in mutant IDH1 compared with wild-type IDH1 or control cells for both p44 and p42 isoforms (supplemental Figure 11). We next studied the phosphorylation of downstream and upstream targets of ERK. No difference in phosphorylation levels of Elk-1 and p90RSK (Ser380) was observed between CTL, IDH1wt, and IDH1mut cells (Figure 4I), but phosphorylation of CREB was increased in IDH1mut cells (Figure 4I). Levels of activated RAS and total RAS were similar in CTL, IDH1wt, and IDH1mut cells, suggesting that other signals than RAS activate ERK (Figure 4J). We next assessed whether increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) may be responsible for MEK/ERK activation in IDH1 mutated cells. Indeed, ROS levels were significantly higher in IDH1mut cells compared with IDH1wt or CTL cells (Figure 4K). In summary, mutant IDH1 is associated with enhanced MAPK signaling, possibly through increased ROS levels, and induces resistance against MEK inhibitors.

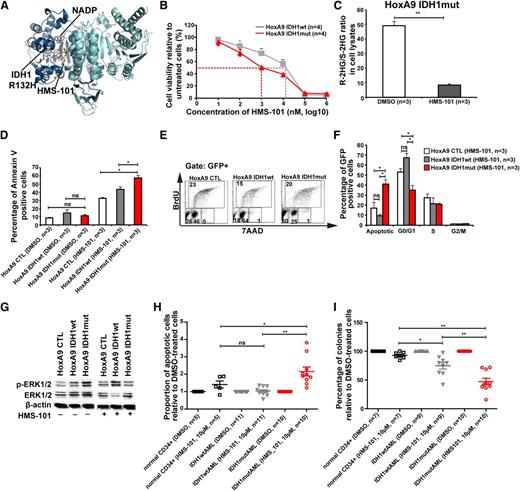

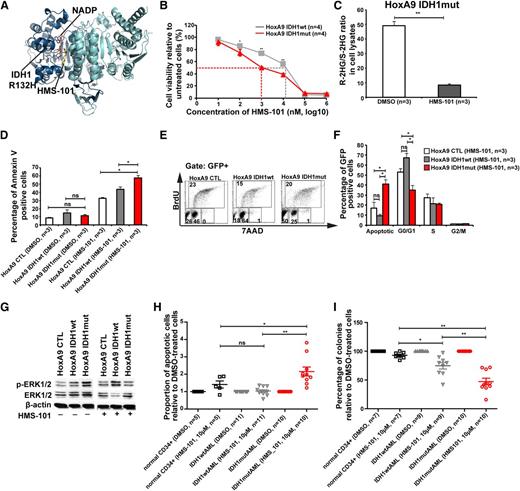

A novel inhibitor of mutant IDH1 inhibits human AML cell growth

Because inhibition of several signaling pathways did not selectively inhibit IDH1mut cells, we performed a computational drug screen using the ZINC library39 and the published crystal structure of mutant IDH1. By computational screening we identified a potential inhibitor of mutant IDH1 termed 2-[2-[3-(4-fluorophenyl)pyrrolidin-1-yl]ethyl]-1,4-dimethylpiperazine (here termed HMS-101). Computational modeling showed that HMS-101 binds to the isocitrate-binding pocket of mutant IDH1 (Figure 5A). The 50% inhibition/inhibitory concentration for HMS-101 was significantly lower in mouse bone marrow cells transduced with IDH1mut compared with IDH1wt (1 µM vs 12 µM, respectively, P < .001, Figure 5B). Treatment of HoxA9+IDH1mut cells with HMS-101 at 10 µM significantly reduced intracellular R-2HG levels in vitro (Figure 5C). HMS-101 induced apoptosis in IDH1mut cells as evidenced by Annexin V staining (Figure 5D) and cell-cycle analysis by BrDU (Figure 5E-F). Phospho-ERK1/2 and the ratio of phospho-ERK/total-ERK were markedly reduced in IDH1mut cells compared with IDH1wt or control cells, when treated with HMS-101 (10 µM; Figure 5G; supplemental Figure 12). Next, we evaluated the effect of HMS-101 on human AML cells and CD34+ bone marrow cells from healthy donors. Cells were treated in vitro with HMS-101 (10 µM), the highest tolerated dose in normal CD34+ human bone marrow cells (supplemental Figure 13) or solvent control for 72 hours to study the rate of apoptosis, or they were plated in methylcellulose in the presence of HMS-101 (10 µM) or solvent control. The percentage of apoptotic cells in HMS-101–treated cells relative to solvent-treated cells was significantly higher in cells from IDH1 mutant patients (P = .001), but not in IDH1wild-type (P = .9) or CD34+ cells from healthy controls (P = .1), and was higher in IDH1 mutant patients compared with IDH1 wild-type patients or healthy controls (P = .001 and P = .04, respectively; Figure 5H). Colony formation in HMS-101–treated cells relative to solvent-treated cells was significantly inhibited in cells from IDH1 mutant patients (P < .0001), and also to some extent in IDH1wt patients (P = .002), but was not affected in CD34+ cells from healthy controls. Colony formation in HMS-101–treated cells was lower in IDH1 mutant patients compared with IDH1 wild-type and control patients (P = .003 and P < .001, respectively; Figure 5I), suggesting a higher efficacy in IDH1 mutant than in IDH1 wild-type AML. In summary, we identified an inhibitor of mutant IDH1 that shows promising activity in mouse bone marrow cells and in primary human AML cells, suggesting that mutant IDH1 is a relevant and druggable target in AML.

A novel inhibitor of mutant IDH1 inhibits human AML cell growth. (A) Structural model of the IDH1R132H dimer showing binding of HMS-101 and NAD phosphate (NADP) to the active center of IDH1. (B) Cell viability of HoxA9+IDH1wt and HoxA9+IDHmut cells incubated with increasing concentrations of HMS-101 (mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments). (C) Ratio of R-2HG and S-2HG in HoxA9+IDHmut-transduced bone marrow cells incubated with 10 µM HMS-101 for 72 hours (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (D) Induction of apoptosis by HMS-101 (10 µM) indicated by the proportion of annexin V positive cells in murine bone marrow cells transduced with HoxA9 CTL, HoxA9 IDH1wt, and HoxA9 IDH1mut after 72 hours of treatment (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (E) Representative FACS blots of cell-cycle phases in HoxA9 CTL, HoxA9 IDH1wt, and HoxA9 IDH1mut cells treated with HMS-101 (10 µM) for 72 hours. Cell-cycle phases were determined by analysis of BrdU/7AAD-stained cells by FACS. The upper quadrant represents cells in S phase, the lower left quadrant represents apoptotic cells, the lower middle quadrant represent cells in G0/G1 phase, and the lower right quadrant represents cells in G2/M phase of the cell cycle. (F) Quantitative analysis of cell-cycle distribution after treatment with HMS-101 (10 µM) in the HoxA9 CTL, HoxA9 IDH1wt, and HoxA9 IDH1mut cell lines for 72 hours as described in Figure 5E (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (G) Representative western blot of in vitro–cultured cells treated with HMS-101 for the indicated murine cell lines using antibodies against phospho-ERK, total-ERK, and β-actin as loading control. (H) Induction of apoptosis by HMS-101 (10 µM) in the indicated cell types relative to dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)-treated cells after suspension culture for 72 hours. (I) Inhibition of colony formation in CFC assays using human cells from healthy donors or AML patients with wild-type or mutant IDH1 by HMS-101 relative to DMSO-treated cells (mean ± SEM). *P < .05; **P < .01; ns, not significant.

A novel inhibitor of mutant IDH1 inhibits human AML cell growth. (A) Structural model of the IDH1R132H dimer showing binding of HMS-101 and NAD phosphate (NADP) to the active center of IDH1. (B) Cell viability of HoxA9+IDH1wt and HoxA9+IDHmut cells incubated with increasing concentrations of HMS-101 (mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments). (C) Ratio of R-2HG and S-2HG in HoxA9+IDHmut-transduced bone marrow cells incubated with 10 µM HMS-101 for 72 hours (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (D) Induction of apoptosis by HMS-101 (10 µM) indicated by the proportion of annexin V positive cells in murine bone marrow cells transduced with HoxA9 CTL, HoxA9 IDH1wt, and HoxA9 IDH1mut after 72 hours of treatment (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (E) Representative FACS blots of cell-cycle phases in HoxA9 CTL, HoxA9 IDH1wt, and HoxA9 IDH1mut cells treated with HMS-101 (10 µM) for 72 hours. Cell-cycle phases were determined by analysis of BrdU/7AAD-stained cells by FACS. The upper quadrant represents cells in S phase, the lower left quadrant represents apoptotic cells, the lower middle quadrant represent cells in G0/G1 phase, and the lower right quadrant represents cells in G2/M phase of the cell cycle. (F) Quantitative analysis of cell-cycle distribution after treatment with HMS-101 (10 µM) in the HoxA9 CTL, HoxA9 IDH1wt, and HoxA9 IDH1mut cell lines for 72 hours as described in Figure 5E (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (G) Representative western blot of in vitro–cultured cells treated with HMS-101 for the indicated murine cell lines using antibodies against phospho-ERK, total-ERK, and β-actin as loading control. (H) Induction of apoptosis by HMS-101 (10 µM) in the indicated cell types relative to dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)-treated cells after suspension culture for 72 hours. (I) Inhibition of colony formation in CFC assays using human cells from healthy donors or AML patients with wild-type or mutant IDH1 by HMS-101 relative to DMSO-treated cells (mean ± SEM). *P < .05; **P < .01; ns, not significant.

Discussion

We investigated the biologic consequences of constitutive expression of mutant IDH1 in mouse bone marrow cells and found that mutant IDH1 induces a MPD-like myeloid leukemia when combined with HoxA9. Mutant IDH1 accelerated cell-cycle transition possibly by repression of CDK inhibitors, and enhanced MAPK/ERK signaling. A novel inhibitor of mutant IDH1 decreased 2HG production and inhibited progenitor cells from IDH1 mutated AML patients, suggesting that mutant IDH1 is a relevant and druggable target in AML.

In initial experiments, we evaluated the effect of mutant IDH1 alone in vivo. Within 5 months after transplantation, we did not see an engraftment benefit of mutant IDH1 and therefore decided to stop the experiment. Sasaki et al showed that IDH1mut knock-in mice developed splenomegaly and increased levels of hematopoietic stem cells in older mice, but did not die of myeloid disease within 2 years of observation.23 Because of the relatively short observation period in our study, we may have missed such an effect of mutant IDH1. However, we focused on collaborating oncogenes to mimic the physiologic situation in AML patients, where several mutations may co-occur. Based on an initial report that mutant IDH1 was associated with HOX gene overexpression,18 we confirmed this association in 2 large cohorts of AML patients and selected HOXA9 as a potential cooperating oncogene.

We found that mutant IDH1 in combination with HoxA9 accelerates the onset of an MPD. Following Bethesda criteria, we termed the disease MPD-like myeloid leukemia.42 The contribution of mutant IDH1 to the disease phenotype seems to be enhanced cell proliferation as evidenced by a rapid increase in white blood cell counts and spleen weight in transplanted mice, an increased proportion of cells in S/G2/M phases of cell cycle in vivo and in vitro, and shorter disease latency in primary and secondary transplants. The frequency of hematopoietic stem cells was similar between mutant and wild-type IDH1 and controls, likely because of the fairly differentiated monocytic phenotype of HoxA9-expressing cells that dominated the morphology of all groups.

We observed a slight increase in bone marrow blasts in mutant IDH1 cells, suggesting that mutant IDH1 has an inhibitory effect on differentiation. Previous studies showed that mutant IDH1 blocks myeloid and adipocyte differentiation,17,20 as evidenced by an increased cKit expression in CFCs from mouse bone marrow transduced with mutant IDH2, when compared with wild-type IDH2,17 and reduced lipid droplet accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells transduced with IDH2R172K when compared with either wild-type IDH2 or vector control.20

By gene set enrichment analysis in our study, we found MAPK signaling most upregulated in mutant IDH1 cells. Western blot analysis of ERK1/2 and pharmacologic inhibition of MAPK signaling supported activation of the MAPK pathway, whereas inhibition of many other signaling pathways did not show differential sensitivity in mutant or wild-type cells. MAPK signaling was also upregulated in a previous study in melanoma cells ectopically expressing mutated IDH1.8 We found that IDH1mut cells generated increased levels of ROS, which are known to activate MAPK signaling. Previous studies have shown that elevated 2HG levels resulted in increased ROS levels43,44 ; altered reduced NAD phosphate metabolism resulting from mutated IDH1 could further exacerbate this effect. Two previous studies measured ROS levels in IDH1 mutated cells and did not find elevated levels of ROS.8,23 This discrepancy may be due to different methods that were used in these studies. ROS levels were measured by CM-H2DCFDA staining in the negative studies, which has 35- and 39-fold lower reactivity to H2O2 than to the hydroxyl radical and peroxynitrite anion, respectively,45 whereas Amplex red was used in our study reacting primarily with H2O2. Alternatively, ROS levels and MAPK signaling may be increased due to enhanced cell proliferation.46

A recent study showed that mutant IDH1 induces cytokine independence in the leukemia cell line TF1. Interestingly, this effect was also seen when cells were treated with R-2HG, but not when treated with S-2HG,22 demonstrating the biologic relevance of R-2HG. To explore whether inhibition of the enzymatic function of mutated IDH1 had antileukemic effects, we searched for specific IDH1 inhibitors using an in silico screening platform. One of our hits with high affinity to mutated IDH1 demonstrated promising activity in vitro on cell proliferation and ERK signaling. The specificity of the IDH1 inhibitor HMS-101 was shown by reduction of R-2HG levels in IDH1 mutant cells. The inhibitor enhanced apoptosis and inhibited colony formation in murine cells and primary AML cells from IDH1 mutated patients. Colony formation was also reduced in some AML patients with wild-type IDH1, but not in CD34+ bone marrow cells from healthy donors. This data suggest that primary AML cells depend on mutated IDH1, that targeting of IDH1 may have therapeutic benefit, and that mutant IDH1 can be effectively targeted in human AML cells.

In summary, mutant IDH1 cooperates with HOXA9 to induce a MPD-like myeloid leukemia and enhances cell proliferation possibly through repression of CDK inhibitors. Pharmacologic inhibition of 2HG production inhibits AML cell survival and suggests that mutant IDH1 is a relevant therapeutic target in AML.

The data in this report have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus Database (accession number GSE45019).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Central Animal Facility of Hannover Medical School, Rena-Mareike Struss, Manoj Balakrishna Menon, Micheal M. Morgan, and Bettina Wagner, for their support on this project. The authors thank Peter Valk, Ruud Delwel, and Bob Löwenberg for provision of gene expression profiling data and Matthias Gaestel for helpful discussions. The authors thank the staff of the Norddeutscher Verbund für Hoch- und Höchstleistungsrechnen for providing computational resources and support.

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the Cell Sorting Core Facility of the Hannover Medical School supported in part by the Braukmann-Wittenberg-Herz-Stiftung and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). This work was supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe e.V (109003, 110284, and 110292), Deutsche-José-Carreras Leukämie-Stiftung e.V (DJCLS R 10/22), H. W. & J. Hector Stiftung (M 47.1), German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01EO0802, Integriertes Forschungs- und Behandlungszentrum Transplantation), DFG (HE 5240/4-1, HE 5240/5-1, and TH 1779/1-1), Hannover Medical School Hochschulinterne Leistungsförderung grant (A.C.)., and DFG grant Li 1608/2-1 (Z.L., J.K., and J.M.).

Authorship

Contribution: A.C. and M.H. designed the research; A.C., M.M.A.C., N.J., A.S., H.Y., K.G., M.W., A.S., M.P., F.T., J.M., R.H., E.A.S., E.E.J., U.M., Z.L., L.M.S., R.G., R.L., and U.L. performed the research; F.T., J.K., A.G., and M.H. contributed patient samples and clinical data; A.C., M.M.A.C., N.J., A.S., M.P., F.T., J.M., E.A.S., R.G., D.J.M., U.L., J.K., A.G., and M.H. analyzed the data; A.C. and M.H. wrote the manuscript; and all authors read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.C., M.P., and M.H. have filed a patent for clinical and research use of drug HMS-101. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael Heuser, Department of Hematology, Hemostasis, Oncology, and Stem Cell Transplantation, Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg Strasse 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany; e-mail: heuser.michael@mh-hannover.de.

![Figure 1. Effect of constitutive expression of mutated IDH1 in primary bone marrow cells in vitro and in vivo. (A) Cumulative CFC yield is shown for an initial plating of 1000 transgene-expressing cells (cells were sorted before plating; mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments). (B) Protein expression of mouse bone marrow cells transduced with a CTL vector or with FLAG-tagged wild-type IDH1 or mutant IDH1 using an anti-FLAG antibody. Cells were harvested from bone marrow 4 weeks after transplantation. β-actin was probed on the same blot as a loading control. (C) Ratio of R-2HG to S-2HG in mouse bone marrow cells transduced with CTL vector or with wild-type or mutant IDH1. Cells were harvested from bone marrow 4 weeks after transplantation (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] of 3 independent mice). (D) Engraftment of transduced cells in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of 1 × 105 transgene-positive cells (mean ± SEM). (E) White blood cell count in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells (mean ± SEM). (F) Hemoglobin levels in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells (mean ± SEM). (G) Platelet count in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells (mean ± SEM). (H) Immunophenotype of transduced cells in peripheral blood at 16 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM). (I) Average spleen weight in mice receiving transplants of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells 20 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM). *P < .05; **P < .01; ns, not significant. WB, western blot.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/122/16/10.1182_blood-2013-03-491571/4/m_2877f1.jpeg?Expires=1769569205&Signature=YuHmOBHDi8DKxb-xxYX-WKxiNFcrMha4obGk-K~wIFjoN-7CKeLQXvozTCVwz10h0oaUA2M~PMlsok6geLU04qJ9JbS7a4no1kvwrMC0fI4lJ1ogRhbRn0qhED-eRdY7jbznLaduZmr11zBs0MVkVEJGdGftCeTS3kZjYOr1pILpsNyC~qvBNn6~t8p-lP8N62t24h3SDKAPa-ve22b2lTvGwyO8M8tl7OQF5QFtm1vkjO87OOHAelmoOgoDvsk8TPZCMS55bf1bhfn0vrgvLm8JSwukA-HhJs8A68lzYo4SAcCp-muf9ymxN5OTGdtl1RMTnS6T~kpmUFpuFASo0A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 1. Effect of constitutive expression of mutated IDH1 in primary bone marrow cells in vitro and in vivo. (A) Cumulative CFC yield is shown for an initial plating of 1000 transgene-expressing cells (cells were sorted before plating; mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments). (B) Protein expression of mouse bone marrow cells transduced with a CTL vector or with FLAG-tagged wild-type IDH1 or mutant IDH1 using an anti-FLAG antibody. Cells were harvested from bone marrow 4 weeks after transplantation. β-actin was probed on the same blot as a loading control. (C) Ratio of R-2HG to S-2HG in mouse bone marrow cells transduced with CTL vector or with wild-type or mutant IDH1. Cells were harvested from bone marrow 4 weeks after transplantation (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] of 3 independent mice). (D) Engraftment of transduced cells in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of 1 × 105 transgene-positive cells (mean ± SEM). (E) White blood cell count in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells (mean ± SEM). (F) Hemoglobin levels in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells (mean ± SEM). (G) Platelet count in peripheral blood at different time points after transplantation of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells (mean ± SEM). (H) Immunophenotype of transduced cells in peripheral blood at 16 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM). (I) Average spleen weight in mice receiving transplants of control or IDH1-transduced bone marrow cells 20 weeks after transplantation (mean ± SEM). *P < .05; **P < .01; ns, not significant. WB, western blot.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/122/16/10.1182_blood-2013-03-491571/4/m_2877f1.jpeg?Expires=1769569206&Signature=xJM2cgSp3zSYCWRvuiuwpaGS5zpcdb~C9yobr0h8Sv-KQAXKzZRgLJRPnw8n5NfzdSeEzSaoHafemNUAVbzJMvIp~0Mdumai4biqznSEVSkXTWdPBz~M-4~qCTgWgxqgN--q7AsIVS7j7dylLu1u5KGckX5LtpLizQ6ND5~xCi9xLHj2lQH9rRx-RxtsYYqrURbkv99aZoLKp-fyj76Q6lLa5GX2DCgPRO1kp4aJnexd-VPEY7E-m8dUZUPljf7SXlnkorSakJ-icyhhPThL4LPFTS-VkLvCfFi3F~Vr4QblBq3fWhE-Fvc4cJGZz5F4CGJhh7kjDkxqHAr6sS7BwQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)