Key Points

Human SIRPA knock-in mice should be an ideal basic xenograft model to analyze hematopoiesis, leukemogenesis, and tumorigenesis in humans.

Abstract

In human-to-mouse xenogeneic transplantation, polymorphisms of signal-regulatory protein α (SIRPA) that decide their binding affinity for human CD47 are critical for engraftment efficiency of human cells. In this study, we generated a new C57BL/6.Rag2nullIl2rgnull (BRG) mouse line with Sirpahuman/human (BRGShuman) mice, in which mouse Sirpa was replaced by human SIRPA encompassing all 8 exons. Macrophages from C57BL/6 mice harboring Sirpahuman/human had a significantly stronger affinity for human CD47 than those harboring SirpaNOD/NOD and did not show detectable phagocytosis against human hematopoietic stem cells. In turn, Sirpahuman/human macrophages had a moderate affinity for mouse CD47, and BRGShuman mice did not exhibit the blood cytopenia that was seen in Sirpa−/− mice. In human to mouse xenograft experiments, BRGShuman mice showed significantly greater engraftment and maintenance of human hematopoiesis with a high level of myeloid reconstitution, as well as improved reconstitution in peripheral tissues, compared with BRG mice harboring SirpaNOD/NOD (BRGSNOD). BRGShuman mice also showed significantly enhanced engraftment and growth of acute myeloid leukemia and subcutaneously transplanted human colon cancer cells compared with BRGSNOD mice. BRGShuman mice should be a useful basic line for establishing a more authentic xenotransplantation model to study normal and malignant human stem cells.

Introduction

Xenogeneic transplantation using immunodeficient mouse models is an established method to analyze human hematopoiesis and tumorigenesis.1-3 Over the decades, extensive progress has been made in establishing mouse lines that are capable of efficient engraftment and growth of human hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) or cancer stem cells. These xenotransplantation models are necessary to develop translational cancer research.4

Successful xenotransplantation can be achieved primarily through prevention of human graft rejection. To deplete T and B cells from recipient mice, the scid mutation in Prkdc5-7 or disruption of the recombination activating gene 1 and 2 (Rag1 and Rag2)8-10 have been introduced. In addition, to deplete NK cells or their functions, the interleukin-2 receptor common γ chain subunit (Il2rg) or B2m was disrupted.11-13 It has also been empirically shown that mice with the nonobese diabetic (NOD) or BALB/c genetic background exhibit efficient human-to-mouse xenotransplantation of hematopoiesis.14 Accordingly, immunodeficient mice on a NOD or BALB/c background, including NOD-scid Il2rgnull,12,13 NOD.Rag1nullIl2rgnull (NOD-RG),15 and BALB/c.Rag1/2nullIl2rgnull (BALB-RG)14-16 strains, have been gold standard mouse models for xenogeneic transplantation studies.

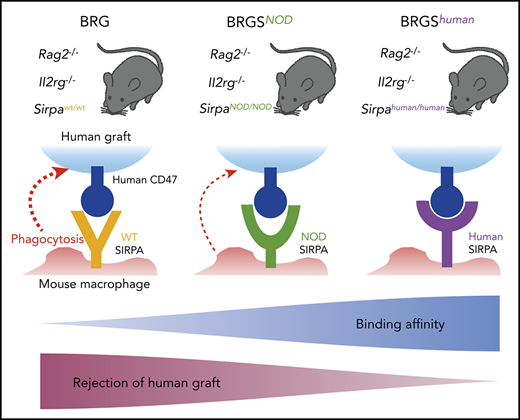

We have reported that the strain-specific genetic determinant of human hematopoiesis engraftment was a polymorphism of the signal-regulatory protein α (Sirpa) gene.17-19 SIRPA is a transmembrane protein that is expressed on macrophages and binds its ligand, CD47, which is ubiquitously expressed.20 The binding of CD47 by SIRPA mediates inhibitory signals for macrophages to prevent autophagocytic activities: the so-called “don’t eat me” signaling.20-22 This binding is species specific; in most mouse strains, mouse SIRPA cannot recognize human CD47, resulting in activation of mouse macrophages and rejection of grafted human tissues.17,18

In normal hematopoiesis, CD47-SIRPA signaling is necessary to maintain homeostasis, because homozygous Sirpa-knockout (Sirpa−/−) mice developed anemia and thrombocytopenia, presumably as a result of enhanced blood cell clearance from the circulation23 and/or malformation of the hematopoietic niche.24 Interestingly, the mouse SIRPA immunoglobulin variable (IgV) domain is highly polymorphic, and the unique SIRPA IgV domains of NOD and BALB/c mice confer an enhanced affinity for human CD47.17 The binding affinity of recipient SIRPA to human CD47 should be 1 of the critical factors that determines the efficiency of human-to-mouse xenotransplantation. We have shown that NOD SIRPA has the strongest affinity to human CD47, whereas BALB/c SIRPA has an intermediate affinity, and C57BL/6 (B6) SIRPA has no affinity; the affinity levels appeared to correlate with reconstitution levels of human hematopoiesis after xenotransplantation.17,25 This was confirmed by our study showing that the replacement of B6 Sirpa with NOD Sirpa in the C57BL/6.Rag2nullIl2rgnull (BRG) mouse greatly improved the efficiency of human hematopoiesis engraftment.19 The BRG-SirpaNOD/NOD (BRGSNOD) mice efficiently supported human hematopoiesis that was equal to or even better than NOD-RG mice,19 whose efficiency had been reported to be nearly equivalent to NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice.14,15

Several studies have also shown that the enforced expression of human SIRPA can enhance human hematopoiesis in immunodeficient mice. The introduction of a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) minigene that encompasses the entire human SIRPA gene into 129×BALB/c.Rag2nullIl2rgnull (129.BALB-RG) mice significantly improved human hematopoiesis to a level comparable to that of NSG mice.26 In another study, the extracellular domain of human SIRPA (exons 2-4) was knocked into the 129.BALB-RG strain to form chimeric human/mouse Sirpa, preserving the intracellular portion of mouse Sirpa.27 129.BALB-RG mice with a heterozygous human SIRPA knock-in allele could reconstitute human hematopoiesis comparable to NSG mice; interestingly, homozygous mice exhibited a significantly lower level of human hematopoiesis. This result was interpreted that, like the phenotype of Sirpa−/− mice,24 SIRPA signal–dependent osteogenic differentiation for forming hematopoietic niches in the bone might be impaired in homozygous SIRPA knock-in mice, presumably because the chimeric SIRPA did not recognize mouse CD47.

In the present study, we generated B6 mice with a knock-in allele for full-length human SIRPA encompassing all 8 exons (B6-Sirpahu/hu). In vitro measurement of affinity for human CD47 demonstrated that B6-Sirpahu/hu macrophages had the greatest affinity, and heterozygous B6-Sirpahu/W and B6-SirpaNOD/NOD macrophages exhibited intermediate affinity. Strikingly, B6-Sirpahu/hu macrophages showed a moderate level of affinity for mouse CD47. We then established the BRG mouse line harboring Sirpahu/hu (BRGShuman). BRGShuman mice had a long lifespan and did not develop anemia or thrombocytopenia. Human hematopoietic multilineage reconstitution after transplantation of human CB was significantly improved in BRGShuman mice, which was further emphasized in the peripheral blood and spleen. In addition, BRGShuman mice showed better engraftment potential for human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells and human colorectal cancer (CRC) cells compared with BRGSNOD mice. Thus, the BRGShuman mouse should be a useful xenograft model to analyze normal and malignant hematopoiesis, as well as tumorigenesis, in humans.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6J, B6.Cg-Rag2tm1.1Cgn/J, B6.129S4-Il2rgtm1Wjl/J, and NSG mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. We established a new human SIRPA knock-in mouse line using the targeting vector, including full-length human SIRPA coding sequence with the BGHpA sequence (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site), which resulted in a B6 mouse line with human SIRPA knocked into the mouse Sirpa loci. We intercrossed these strains by conventional breeding to obtain BRGShuman mice. BRGSNOD mice were developed in our laboratory (at Department of Medicine and Biosystemic Science, Kyushu University Graduate School of Medical Sciences) as previously described.19 Rag2, Il2rg, and Sirpa genes were genotyped by direct sequencing after PCR amplification to identify the genotype of BRGShuman mice. Primer sequences are described in supplemental Table 1. All mice were bred and maintained under specific pathogen–free conditions at the Kyushu University Animal Facility. All experiments were conducted following the guidelines of the institutional animal committee of Kyushu University.

Determination of the irradiation dose

BRG and BRGSNOD mice exhibit more tolerance for irradiation than do NOG/NSG mice, which are highly radiosensitive, presumably because of the scid mutation. To determine the irradiation dose for BRGShuman mice, 6- to 8-week-old BRGShuman mice were irradiated with 400 to 640 cGy and monitored for 8 weeks (supplemental Figure 1B). Early deaths were observed in the mouse group irradiated with >620 cGy, whereas mice irradiated with 450 to 600 cGy were still alive at the end of the 8 weeks. Thus, as preconditioning for xenotransplantation experiments, BRGShuman mice were irradiated with 600 cGy, and BRGSNOD, BRG, and NSG mice were irradiated with 550 cGy, 670 cGy, and 220 cGy, respectively, based on previous studies.11,13,19

Xenotransplantation of human cells into immunodeficient mice

Lineage (Lin)-depleted CB cells were obtained using magnetic beads (Lineage Cell Depletion Kit; Miltenyi Biotec), and Lin−CD34+CD38− CB cells were sorted using a FACSAria II or III (BD Biosciences). It has been shown that human cell chimerism after xenotransplantation is higher in female mice than in male mice.19,28 As shown in supplemental Figure 2, this was also the case for BRGShuman mice, in terms of human cell chimerism after transplantation, for the bone marrow and the periphery. It has also been shown that, with regard to xenotransplantation using adult mice, intrafemoral injection was more efficient than IV injection.29 As shown in supplemental Figure 3, intrafemoral injection was significantly superior to IV injection in BRGSNOD mice. Based on these data, transplantation was restricted to female recipients using intrafemoral injection to exclude those variables.

To reconstitute human hematopoiesis in mice, Lin−CD34+CD38− CB cells (5 × 103 per mouse) were injected into the right femur of 6- to 8-week-old irradiated mice, as previously described.19,28 Mice were euthanized, and samples were analyzed 10 to 12 weeks or 20 to 24 weeks after transplantation. Human CB cells were collected during normal full-term deliveries, after obtaining informed consent and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and were provided by the Japanese Red Cross Kyushu Cord Blood Bank.

To assess the reconstitution capability of human cancer cells, xenotransplantation of AML and CRC cells was performed. A total of 1 × 106 CD33+CD45lo or CD34+ leukemia cells purified from AML patients was transplanted into irradiated mice. The DLD-1 cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection and injected subcutaneously with Matrigel (BD Biosciences), as previously described.30 For in vivo limiting dilution analysis, 40, 200, or 1000 DLD-1 cells were injected into BRGShuman and BRGSNOD mice (n = 6 each). To establish a patient-derived CRC xenograft model, CRC cells were obtained as surgical specimens and injected subcutaneously with Matrigel into BRGSNOD mice. Engrafted tumor cells were collected, and 1 × 105 engrafted CRC cells were injected into BRGShuman and BRGSNOD mice (n = 6 each). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Welfare Guidelines of Kyushu University. Clinical samples were collected after written informed consent was obtained from patients at Kyushu University Hospital. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyushu University Hospital.

Flow cytometric analysis of mouse and human hematopoietic cells

For the analyses of mouse T, B, and natural killer (NK) cells, mouse peripheral blood cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD19, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD3, allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-NK1.1, and Pacific Blue–conjugated anti–Gr-1 antibodies. To confirm expression of SIRPA at the protein level, mouse macrophages were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD11b, PE-conjugated anti-mouse SIRPA, and APC-conjugated anti-human SIRPA antibodies. Sorting of the Lin−CD34+CD38− subfraction in human CB samples was accomplished by staining with FITC-conjugated anti-CD34 antibodies, BV421-conjugated anti-CD38 antibodies, and a PerCP-Cy5.5–conjugated lineage cocktail including anti-human CD3, CD4, CD8, CD10, CD11b, CD14, CD19, CD20, CD56, and CD235ab antibodies. For the analysis and sorting of human cells after xenogeneic transplantation, we used a combination of FITC-conjugated anti-human CD33 or CD34, PE-conjugated anti-human NKp46 or CD10, PE-Cy7–conjugated anti-human CD19 or CD20, APC-conjugated anti-human CD3 or IgM, APC-Cy7–conjugated anti-human CD45, Pacific Blue–conjugated anti-mouse CD45 or anti-human CD19, and PerCP-Cy5.5–conjugated anti-mouse TER-119 antibodies. Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies used for flow cytometric analysis are listed in supplemental Table 2. The cells were analyzed and sorted with a FACSAria II or III cell sorter.

SIRPA-CD47 binding assay

Mouse macrophages were obtained by peritoneal lavage, as described previously.17,21 The binding of SIRPA and CD47 was assessed by flow cytometry and a peroxidase activity assay, as detailed previously.17 For the analysis using flow cytometry, mouse macrophages were stained with FITC-conjugated CD11b, PE-conjugated anti-mouse SIRPA, and biotinylated human CD47-Fc plus APC-conjugated streptavidin. The cells were analyzed with a FACSAria III cell sorter. For the peroxidase activity assay, mouse macrophages were incubated at 37°C in a 96-well plate in the presence of increasing concentrations of purified human or mouse CD47-Fc fusion protein and then incubated at 4°C with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat polyclonal antibody specific for the Fcγ fragment of human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch), followed by a peroxidase assay. Human or mouse CD47-Fc fusion protein binding was determined by absorbance at 490 nm on a microplate reader. Nonlinear regression analysis was performed to calculate dissociation constant (Kd) and maximal binding capacity (Bmax) using the KaleidaGraph analysis program.

In vitro mouse macrophage phagocytosis assays for human HSC populations

Phagocytic activity of mouse macrophages against the human CD34+CD38− population was evaluated in vitro, as described.17 In brief, mouse peritoneal-derived macrophages were incubated with mouse interferon-γ (100 ng/mL; R&D Systems) and lipopolysaccharide (0.3 μg/μL) and then opsonized human CB-derived HSCs were added. After 2 hours of incubation, the phagocytic index was calculated using the following formula: phagocytic index = number of ingested cells/(number of macrophages/100). At least 200 macrophages were counted per well.

Statistical analysis

The Student t test was used for single comparisons, and 1-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s HSD (honestly significant difference) test was used for multiple comparisons. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP software (version 13.0; SAS Institute), and P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. The Mantel-Cox log-rank test was used to obtain survival curves.

Results

Sirpahu/hu macrophages recognize human CD47 more strongly than do SirpaNOD/NOD macrophages, preventing engulfment of human HSCs

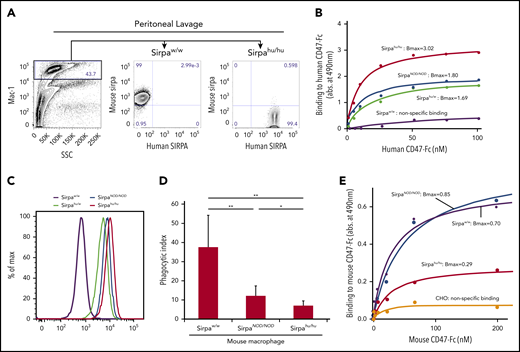

The function of mouse and human SIRPA was tested in peritoneal macrophages from B6 mice with wild-type mouse Sirpa (SirpaW/W), B6 mice with homozygous NOD-type mouse Sirpa (SirpaNOD/NOD), and B6 mice with heterozygous or homozygous knock-in human SIRPA (Sirpahu/W or Sirpahu/hu, respectively). As shown in Figure 1A, macrophages from SirpaW/W mice expressed only mouse SIRPA, whereas those from Sirpahu/hu mice expressed human SIRPA but not mouse SIRPA, demonstrating that mouse and human SIRPA were successfully replaced in the Sirpahu/hu mouse.

Sirpahu/humacrophages bind human CD47 more strongly than do SirpaNOD/NODmacrophages, and they also recognize mouse CD47. (A) Representative flow cytometric plots of peritoneal lavage in B6-SirpaW/W and B6-Sirpahu/hu mice. Mac-1+ peritoneal macrophages from B6-Sirpahu/hu mice express human SIRPA but not mouse SIRPA. (B) Results of dose-dependent binding assays of human CD47-Fc fusion protein to B6-SirpaW/W, B6-SirpaNOD/NOD, B6-Sirpahu/W, and B6-Sirpahu/hu mouse macrophages. Sirpahu/hu macrophages had the strongest binding affinity for human CD47 (Bmax, 3.02 ± 0.19), and Sirpahu/W or SirpaNOD/NOD macrophages had intermediate levels of affinity (Bmax, 1.69 ± 0.23 and 1.80 ± 0.06, respectively), whereas SirpaW/W macrophages did not bind to human CD47. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of macrophage binding to human CD47-Fc fusion. (D) Phagocytosis of opsonized human Lin−CD34+CD38− HSCs by mouse macrophages. The phagocytic index was calculated as the number of engulfed human cells per 100 macrophages. Data are mean ± standard deviation. (E) Dose-dependent binding of mouse CD47-Fc to macrophages. Sirpahu/hu macrophages had moderate binding affinity for mouse CD47 (Bmax, 0.29 ± 0.02). Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells that did not express mouse or human SIRPA were used as a negative control. *P < .05, **P < .01. SSC, side scatter.

Sirpahu/humacrophages bind human CD47 more strongly than do SirpaNOD/NODmacrophages, and they also recognize mouse CD47. (A) Representative flow cytometric plots of peritoneal lavage in B6-SirpaW/W and B6-Sirpahu/hu mice. Mac-1+ peritoneal macrophages from B6-Sirpahu/hu mice express human SIRPA but not mouse SIRPA. (B) Results of dose-dependent binding assays of human CD47-Fc fusion protein to B6-SirpaW/W, B6-SirpaNOD/NOD, B6-Sirpahu/W, and B6-Sirpahu/hu mouse macrophages. Sirpahu/hu macrophages had the strongest binding affinity for human CD47 (Bmax, 3.02 ± 0.19), and Sirpahu/W or SirpaNOD/NOD macrophages had intermediate levels of affinity (Bmax, 1.69 ± 0.23 and 1.80 ± 0.06, respectively), whereas SirpaW/W macrophages did not bind to human CD47. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of macrophage binding to human CD47-Fc fusion. (D) Phagocytosis of opsonized human Lin−CD34+CD38− HSCs by mouse macrophages. The phagocytic index was calculated as the number of engulfed human cells per 100 macrophages. Data are mean ± standard deviation. (E) Dose-dependent binding of mouse CD47-Fc to macrophages. Sirpahu/hu macrophages had moderate binding affinity for mouse CD47 (Bmax, 0.29 ± 0.02). Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells that did not express mouse or human SIRPA were used as a negative control. *P < .05, **P < .01. SSC, side scatter.

Figure 1B shows dose-response curves for the interaction between SIRPA on macrophages and human CD47-Fc protein, as determined by a SIRPA-CD47 binding assay. Sirpahu/hu macrophages showed the strongest binding with human CD47-Fc protein (Bmax, 3.02), whereas Sirpahu/W and SirpaNOD/NOD macrophages had an intermediate level of binding (Bmax, 1.69 and 1.80, respectively), and SirpaW/W macrophages only showed nonspecific binding. The amount of CD47-Fc protein capable of binding to SIRPA expressed on macrophages from each strain was measured by flow cytometry (Figure 1C). Differences in the saturated amount of human CD47 on the surface of each type of macrophage corresponded to their affinity in the binding assay (Figure 1B), confirming that the affinity of Sirpahu/hu macrophages for human CD47 is superior to that of SirpaNOD/NOD macrophages.

To test human CD47-SIRPA signaling, we measured the phagocytic activity of macrophages purified from each mouse strain toward an opsonized human Lin−CD34+CD38− HSC population (Figure 1D). SirpaW/W macrophages had strong phagocytic activity against the human HSC population, whereas SirpaNOD/NOD macrophages showed significantly reduced phagocytic activity. Phagocytosis by Sirpahu/hu macrophages was further significantly reduced compared with that by SirpaNOD/NOD macrophages, correlating inversely with their affinity in binding assays (Figure 1B).

Sirpahu/hu macrophages have moderate affinity for mouse CD47

Although Sirpa−/− mice were reported to develop anemia or thrombocytopenia,31,32 Sirpahu/hu mice did not appear to have these cytopenias (data not shown). Therefore, we tested the binding affinity for mouse CD47-Fc protein in macrophages from SirpaW/W, SirpaNOD/NOD, or Sirpahu/hu mice. As shown in Figure 1E, B6-SirpaNOD/NOD macrophages had a strong binding affinity to mouse CD47 (Bmax, 0.80 ± 0.09) that was comparable to normal B6-SirpaW/W mice (Bmax, 0.70 ± 0.05). Interestingly, B6-Sirpahu/hu macrophages bound to mouse CD47 at a moderate level (Bmax, 0.29 ± 0.02), suggesting the possibility that human SIRPA derived from a full-length human SIRPA knock-in allele can recognize mouse CD47 to prevent phagocytosis against autologous mouse cells.

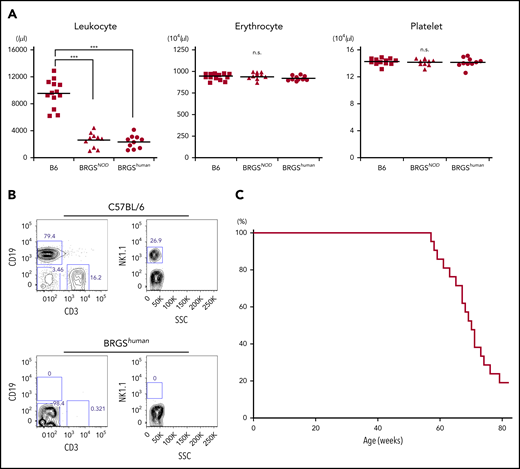

The BRGShuman mouse did not develop anemia or thrombocytopenia and had a long lifespan

The BRGShuman mouse was established by crossing the BRG mouse with the B6-Sirpahu/hu mouse. BRGShuman mice were born healthy and exhibited good fertility. As shown in Figure 2A, they had normal levels of hemoglobin and platelets, unlike Sirpa−/− mice,23 and had reduced numbers of leukocytes as a result of T, B, and NK lymphocyte depletion (Figure 2B). These phenotypes were similar to BRGSNOD mice.19 Like NSG or BRGSNOD mice, BRGShuman mice had a median lifespan of 71 weeks without developing lymphoma, which is the major cause of death in NOD-scid mice or NOD-Rag1null–based strains (Figure 2C).7,9

BRGShumanmice do not exhibit anemia or thrombocytopenia and have a long lifespan. (A) Frequencies of blood leukocytes, erythrocytes, and platelets in adult B6, BRGSNOD, and BRGShuman mice. BRGShuman mice have leukopenia resulting from a loss of lymphocytes but have normal numbers of erythrocytes and platelets. (B) Representative flow cytometric plots of blood in B6 and BRGShuman mice. BRGShuman mice lacked T, B, and NK cells. (C) Kaplan-Meyer survival curve of BRGShuman mice (n = 22). ***P < .001.

BRGShumanmice do not exhibit anemia or thrombocytopenia and have a long lifespan. (A) Frequencies of blood leukocytes, erythrocytes, and platelets in adult B6, BRGSNOD, and BRGShuman mice. BRGShuman mice have leukopenia resulting from a loss of lymphocytes but have normal numbers of erythrocytes and platelets. (B) Representative flow cytometric plots of blood in B6 and BRGShuman mice. BRGShuman mice lacked T, B, and NK cells. (C) Kaplan-Meyer survival curve of BRGShuman mice (n = 22). ***P < .001.

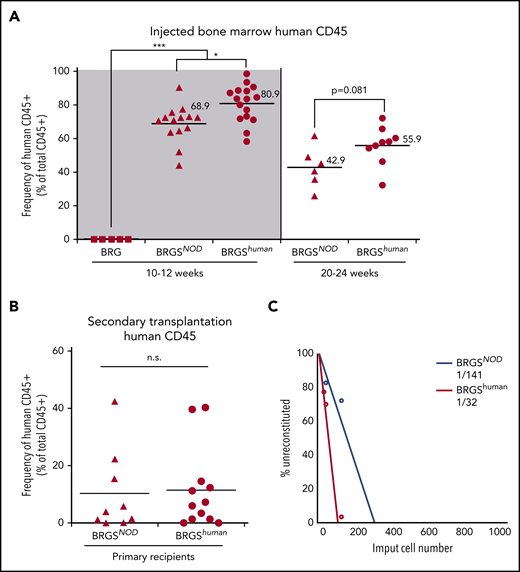

The BRGShuman mouse showed reconstitution of human hematopoiesis and myelopoiesis that was more efficient than the BRGSNOD mouse in the bone marrow

Six- to 8-week-old BRG, BRGSNOD, and BRGShuman mice were irradiated and transplanted with 5 × 103 CD34+CD38− human CB cells. At 10 to 12 weeks after transplantation, human CD45+ cells were not detectable in BRG mice (Figure 3A, left panel). BRGSNOD and BRGShuman mice showed successful human hematopoietic reconstitution in the bone marrow, and the average frequency of human CD45+ cells in BRGShuman mice was significantly higher than that of BRGSNOD mice (80.9% vs 68.9%, respectively). We then analyzed the long-term reconstitution at 20 to 24 weeks after transplantation, because maintenance of human hematopoiesis for >20 weeks is dependent upon self-renewal of human HSCs in the mouse bone marrow niche.33 As shown in Figure 3A (right panel), BRGShuman mice maintained a high level of human cell chimerism (mean, 55.9%) in the bone marrow, exceeding the level in BRGSNOD mice (mean, 42.9%). Then, 106 human CD45+ cells were purified from primary BRGSNOD or BRGShuman recipients at 10 to 12 weeks after xenotransplantation, and these cells were retransplanted into irradiated adult BRGSNOD mice. Eight weeks after the secondary transplantation, re-engraftment of human hematopoietic cells was observed at equivalent levels in the 2 groups (Figure 3B). These data suggest that the BRGShuman and BRGSNOD microenvironments are able to support self-renewal of human HSCs.

BRGShumanmice support engraftment and repopulating capability of human HSCs more efficiently than do BRGSNODmice. (A) Frequencies of human CD45+ cells in the bone marrow of BRG, BRGSNOD, and BRGShuman recipient mice injected with 5 × 103 human Lin−CD34+CD38− cells at 10 to 12 weeks (left panel) and at 20 to 24 weeks (right) after transplantation (n = 5-16 mice per strain). The numbers and horizontal lines indicate mean values. (B) Frequencies of human CD45+ cells in the bone marrow of secondary BRGSNOD recipients injected with 1 × 106 human CD45+ cells purified from the bone marrow of primary BRGSNOD or BRGShuman recipients. The horizontal lines represent mean values. (C) A limiting dilution assay was used to determine the frequencies of repopulating cells of human HSCs in BRGShuman mice (1 in 32 cells) and BRGSNOD mice (1 in 141 cells). *P < .05, ***P < .001. n.s., not significant.

BRGShumanmice support engraftment and repopulating capability of human HSCs more efficiently than do BRGSNODmice. (A) Frequencies of human CD45+ cells in the bone marrow of BRG, BRGSNOD, and BRGShuman recipient mice injected with 5 × 103 human Lin−CD34+CD38− cells at 10 to 12 weeks (left panel) and at 20 to 24 weeks (right) after transplantation (n = 5-16 mice per strain). The numbers and horizontal lines indicate mean values. (B) Frequencies of human CD45+ cells in the bone marrow of secondary BRGSNOD recipients injected with 1 × 106 human CD45+ cells purified from the bone marrow of primary BRGSNOD or BRGShuman recipients. The horizontal lines represent mean values. (C) A limiting dilution assay was used to determine the frequencies of repopulating cells of human HSCs in BRGShuman mice (1 in 32 cells) and BRGSNOD mice (1 in 141 cells). *P < .05, ***P < .001. n.s., not significant.

Next, we performed a limiting dilution assay to quantitate the frequency of repopulating cells by injecting graded doses of CD34+CD38− CB cells (101, 102, or 103 cells per injection) (Figure 3C). The frequency of detectable repopulating cells in the bone marrow was significantly higher in BRGShuman mice (1 per 32 injected cells) vs BRGSNOD mice (1 per 141 injected cells).

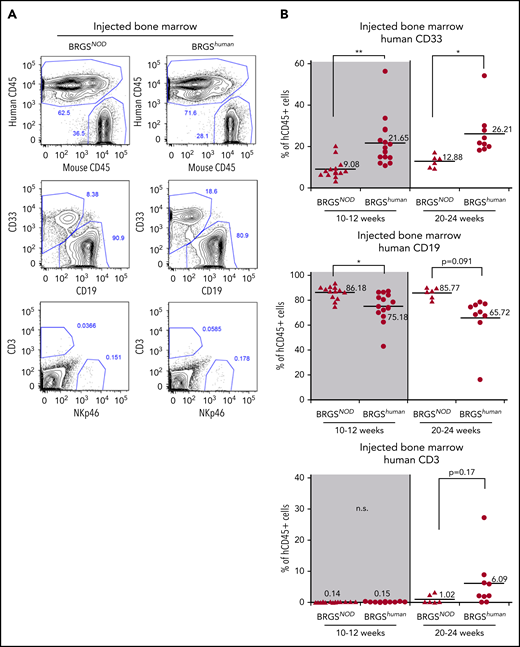

Figure 4A shows the lineage analysis of human CD45+ cells reconstituted in the bone marrow after injection of 5 × 103 CD34+CD38− CB cells. The percentage of CD33+ myeloid cells in BRGShuman mice was 22% and 26% at 10 to 12 weeks and 20 to 24 weeks after transplantation, respectively, whereas the percentage was only 9% and 13%, respectively, in BRGSNOD mice, demonstrating that myeloid reconstitution was significantly better in BRGShuman mice (Figure 4B, top panels). As a result, the percentages of B cells were lower in BRGShuman mice (Figure 4B, middle panels). The majority of reconstituted B cells were CD10+CD19+CD20− immature B cells (supplemental Figure 4). T-cell reconstitution in the bone marrow appeared to be more efficient in BRGShuman mice (6%) than in BRGSNOD mice (1%) at 20 to 24 weeks, although the difference was not statistically significant.

Human myeloid cell reconstitution is enhanced in BRGShumanmice. (A) Representative flow cytometric plots of reconstituted human hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow of BRGSNOD or BRGShuman recipients. The percentages of each lineage are shown as those within the human CD45+ population. Numbers indicate the percentages of gated cells. (B) Frequencies of human CD33+ myeloid cells (top panels), CD19+ B cells (middle panels), and CD3+ T cells (bottom panels) in bone marrow at 10 to 12 weeks (left panels) and at 20 to 24 weeks (right panels) after transplantation. The numbers and horizontal lines indicate mean values. *P < .05, **P < .01. n.s., not significant.

Human myeloid cell reconstitution is enhanced in BRGShumanmice. (A) Representative flow cytometric plots of reconstituted human hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow of BRGSNOD or BRGShuman recipients. The percentages of each lineage are shown as those within the human CD45+ population. Numbers indicate the percentages of gated cells. (B) Frequencies of human CD33+ myeloid cells (top panels), CD19+ B cells (middle panels), and CD3+ T cells (bottom panels) in bone marrow at 10 to 12 weeks (left panels) and at 20 to 24 weeks (right panels) after transplantation. The numbers and horizontal lines indicate mean values. *P < .05, **P < .01. n.s., not significant.

Significant improvement in human hematopoiesis reconstitution in the periphery of BRGShuman mice

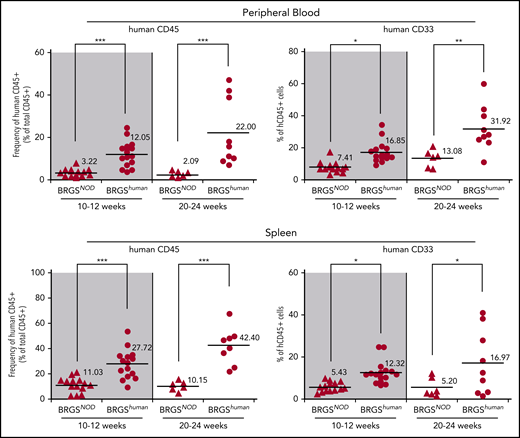

Reconstitution of human hematopoietic cells in the periphery is generally low in xenotransplantation models.34,35 Figure 5 shows the reconstitution in the blood and the spleen in BRGSNOD and BRGShuman mice. Compared with BRGSNOD mice, peripheral reconstitution of human CD45+ cells was dramatically improved in BRGShuman mice at 10 to 12 weeks after transplantation, and it was further improved at 20 to 24 weeks, reaching up to 22% and 42% in the blood and the spleen, respectively. Of note, the percentages of CD33+ myeloid cells within CD45+ cells also progressively increased in the periphery up to 32% and 17% in the blood and the spleen, respectively, at 20 to 24 weeks after transplantation.

Human hematopoiesis reconstitution in the periphery is enhanced in BRGShumanmice. Proportions of human CD45+ cells and CD33+ myeloid cells in peripheral blood (upper panels) and spleen (lower panels) of BRGSNOD and BRGShuman recipients. The numbers and horizontal bars indicate mean values. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Human hematopoiesis reconstitution in the periphery is enhanced in BRGShumanmice. Proportions of human CD45+ cells and CD33+ myeloid cells in peripheral blood (upper panels) and spleen (lower panels) of BRGSNOD and BRGShuman recipients. The numbers and horizontal bars indicate mean values. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

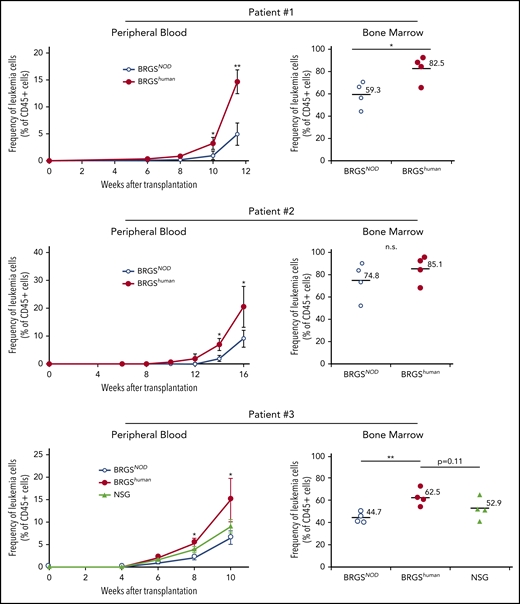

Enhanced engraftment and growth of human cancer cells in the BRGShuman mouse

We wanted to test whether the BRGShuman mouse showed efficient engraftment of cancer cells. We transplanted 106 CD33+CD45RAlo AML cells (patients 1 and 2) or 106 CD34+ AML cells (patient 3) purified from the bone marrow into irradiated BRGSNOD and BRGShuman mice and serially evaluated chimerism in the blood after xenotransplantation. Clinical characteristics of patients are shown in supplemental Table 3. As shown in Figure 6, BRGShuman recipient mice showed accelerated leukemia reconstitution, and human CD45+CD33+ leukemia cell chimerisms in the blood were significantly higher than those in BRGSNOD recipients 10 to 16 weeks after transplantation in all 3 experiments. The chimerism of AML cells in the bone marrow was also higher in BRGShuman recipients at the final analysis. In the analysis of patient 3, we also transplanted AML cells into NSG mice in parallel with BRGSNOD and BRGShuman mice. The AML cell chimerism appeared to be higher in BRGShuman mice than in NSG mice in the blood and the bone marrow, although the difference was not statistically significant.

BRGShumanmice show efficient reconstitution of human AML. The kinetics of human CD45+CD33+ AML cells (patients 1 and 2, top and middle panels) and CD34+ AML cells (patient 3; bottom panels) after transplantation into BRGShuman, BRGSNOD, and NGS mice in the peripheral blood (left panels) and the bone marrow (right panels). The proportions of AML cells in the blood were monitored every 2 weeks, followed by the analysis of bone marrow at the final time point. In all 3 experiments, human AML cell chimerism in BRGShuman mice exceeded that in BRGSNOD mice. *P < .05, **P < .01. n.s., not significant.

BRGShumanmice show efficient reconstitution of human AML. The kinetics of human CD45+CD33+ AML cells (patients 1 and 2, top and middle panels) and CD34+ AML cells (patient 3; bottom panels) after transplantation into BRGShuman, BRGSNOD, and NGS mice in the peripheral blood (left panels) and the bone marrow (right panels). The proportions of AML cells in the blood were monitored every 2 weeks, followed by the analysis of bone marrow at the final time point. In all 3 experiments, human AML cell chimerism in BRGShuman mice exceeded that in BRGSNOD mice. *P < .05, **P < .01. n.s., not significant.

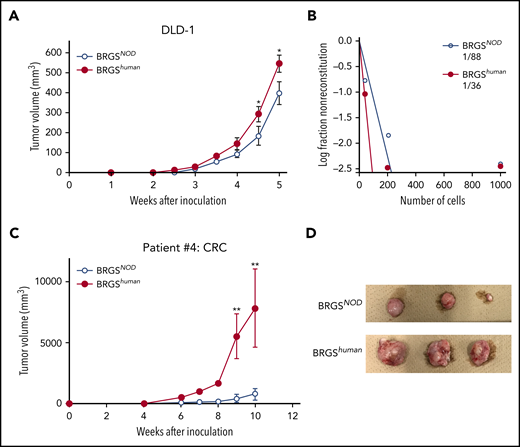

The DLD-1 cell line was used to test xenotransplantation efficiency for human CRC. We transplanted 103 DLD-1 cells subcutaneously with Matrigel, as previously described.30 As shown in Figure 7A, DLD-1 cells successfully engrafted, but the tumor was always bigger in BRGShuman recipient mice vs BRGSNOD recipient mice. A limiting dilution analysis for tumor engraftment showed that the frequency of detectable tumor-initiating DLD-1 cells was 2.4-fold higher in BRGShuman recipient mice (Figure 7B).

BRGShumanmice show efficient reconstitution of human solid cancer cells. (A) Tumor growth curves of DLD-1 cells. DLD-1 cells were transplanted subcutaneously into BRGSNOD or BRGShuman mice, and tumor volume was measured every week (n = 6 each). (B) Analysis of tumor-forming capabilities of DLD-1 cells in BRGSNOD and BRGShuman recipients using an extreme limiting dilution assay; 40, 200, or 1000 DLD-1 cells were injected subcutaneously into BRGSNOD and BRGShuman mice (n = 6 each). Tumor formation was examined 4 weeks after inoculation. (C) Growth curves of xenograft tumors produced by patient-derived CRC cells 10 weeks after inoculation (n = 6 each). Data are mean ± standard deviation. (D) The tumor harvested from each mouse at 10 weeks after inoculation. *P < .05, **P < .01.

BRGShumanmice show efficient reconstitution of human solid cancer cells. (A) Tumor growth curves of DLD-1 cells. DLD-1 cells were transplanted subcutaneously into BRGSNOD or BRGShuman mice, and tumor volume was measured every week (n = 6 each). (B) Analysis of tumor-forming capabilities of DLD-1 cells in BRGSNOD and BRGShuman recipients using an extreme limiting dilution assay; 40, 200, or 1000 DLD-1 cells were injected subcutaneously into BRGSNOD and BRGShuman mice (n = 6 each). Tumor formation was examined 4 weeks after inoculation. (C) Growth curves of xenograft tumors produced by patient-derived CRC cells 10 weeks after inoculation (n = 6 each). Data are mean ± standard deviation. (D) The tumor harvested from each mouse at 10 weeks after inoculation. *P < .05, **P < .01.

We then tested xenotransplantation efficiency for primary human CRC cells. Primary tumor was obtained from patients with CRC, surgical specimens were injected into BRGSNOD mice subcutaneously, and engrafted tumor cells were collected. A total of 105 engrafted CRC cells was subcutaneously injected into BRGShuman or BRGSNOD mice, and secondary tumorigenesis of colon cancer cells was monitored for 10 weeks. Tumor formation was facilitated to a more significant degree in BRGShuman mice compared with BRGSNOD mice (Figure 7C-D). These data strongly suggest that the introduction of human SIRPA into immunodeficient mice can provide a microenvironment suitable for engraftment and growth of human malignant hematopoiesis, as well as for CRC development.

Discussion

In establishing xenotransplantation models, deletion of lymphocytes has been achieved by introduction of the scid mutation in the Prkdc gene or disrupting key lymphoid genes, such as Rag and Il2rg. Another important factor for xenotransplantation efficiency is “macrophage tolerance” driven by the CD47-SIRPA axis, and the NOD-type SIRPA has a polymorphism that is best suited for xenotransplantation models, because it can recognize human CD47 with the highest affinity among a variety of mouse strains.17 In this study, by directly comparing the xenotransplantation efficiency of BRGShuman mice with BRGSNOD mice, whose efficiency was at least equal to NOD-RG mice, we showed that homozygous replacement of NOD-type mouse Sirpa with human SIRPA significantly improved the engraftment efficiency of normal human hematopoiesis, as well as of malignant blood and solid cancers.

The high efficiency of xenotransplantation in BRGShuman mice should be ascribed to the fact that human SIRPA has a much higher affinity for human CD47 than does NOD-type mouse SIRPA (Figure 1B). Interestingly, human SIRPA can also recognize mouse CD47 (Figure 1E). Sirpahu/hu mice and BRGShuman mice did not develop anemia or thrombocytopenia, probably because the engagement of mouse CD47 with human SIRPA can induce signaling at a level sufficient to keep homeostasis within the bone marrow microenvironment in BRGShuman mice. As a result, the BRGShuman mouse line is stable and has a lifespan comparable to BRGSNOD mice (Figure 2C).

Moreover, the capabilities to support human hematopoiesis in BRGShuman mice might be better than those in previous mouse lines expressing human SIRPA. The 129.BALB-RG mouse with a transgenic BAC human SIRPA showed engraftment levels similar to the NSG mouse that has the NOD-type mouse SIRPA in the bone marrow, the blood, or the spleen.26 It might be difficult to guarantee physiologically faithful expression of the BAC transgenic human SIRPA; transgenic expression of human SIRPA depends upon human SIRPA regulatory elements that are regulated by mouse intracellular components. Signaling downstream of BAC transgenic SIRPA should also be complicated in this mouse, because its macrophages coexpress endogenous mouse SIRPA.

The 129.BALB-RG strain has also been used to establish human SIRPA knock-in mice, whose knock-in construct was restricted to exons 2 to 4 that code for the extracellular IgV domain of human SIRPA.27 Mouse and human SIRPA have 8 exons: exons 1 to 4 for the extracellular domain, exon 5 for the transmembrane domain, and exons 6 to 8 for the intracellular domain. The intracellular domain is mostly preserved in mice and humans. In this human SIRPA knock-in model that has human/mouse chimeric SIRPA, the xenotransplantation efficiency of heterozygous knock-in mice was almost equal to that of NSG mice.27 It appears to be accurate, because the affinity of SirpaNOD/NOD macrophages for human CD47 was similar to that of heterozygous Sirpahu/W macrophages in our study (Figure 1B). However, homozygous knock-in mice showed significantly lower xenotransplantation efficiency compared with heterozygous mice, and the investigators speculated that hematopoietic niche formation was impaired by the lack of mouse SIRPA-CD47 signal-dependent bone and stromal cell differentiation, which was observed in SIRPA-deficient mice.24 Because native human SIRPA can recognize mouse CD47 (Figure 1E) and BRGShuman mice that have homozygous full-length human SIRPA showed higher xenotransplantation efficiency than BRGSNOD mice (Figures 3 and 4), it is possible that the chimeric SIRPA somehow lost its affinity for mouse CD47, which native human SIRPA has.

It is noteworthy that CD33+ myeloid cell development, as well as hematopoietic reconstitution in the periphery, was significantly improved in BRGShuman mice. In mouse models based on the NOD or BALB/c background, human hematopoietic reconstitution is B-cell dominant, whereas reconstitution for human myeloid lineage cells is usually limited.12,36 Improvement of myeloid reconstitution has been reported by introducing knock-in human cytokines, including human thrombopoietin37 and stem cell factor,38 into NSG mice or introducing a combination of cytokines, such as macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interleukin-3, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and thrombopoietin, into human BAC-SIRPA transgenic or heterozygous chimeric SIRPA knock-in mice39-41 ; this suggests that a deficiency in cross-reactivity in mouse and human cytokines causes this skewed differentiation. Significant improvement in myeloid differentiation in BRGShuman mice without humanization of cytokines further suggests that physiologically appropriate CD47-SIRPA signaling is critical for human myeloid engraftment, presumably through normalization of macrophage functions in the bone marrow microenvironment42,43 or through inhibition of macrophage engulfment or activation in the periphery.21,44 Because the human cytokine(s) knocked-in and the homozygous full-length SIRPAhuman knocked-in should contribute to myeloid engraftment through independent mechanisms, it might be promising to further improve engraftment by humanization of cytokines in the BRGShuman mouse model. It is also tempting to introduce c-Kit mutations28,45 into BRGShuman mice, because BRGSNOD mice with a KitWv mutation exhibited highly efficient engraftment of human erythropoiesis and thrombopoiesis.28

Human leukemia and a variety of solid cancer cells express CD47 at a level higher than normal tissue cells to reinforce engagement of CD47 and SIRPA, as well as to escape from innate immune surveillance by macrophages.46-48 CD47-SIRPA signaling is also required for cancer cells to survive in the xenotransplantation setting, because human cancer cells transplanted into NOD-scid mice were eliminated by administration of anti-CD47–blocking antibodies.48 Therefore, significant improvement of human cancer cell engraftment in our BRGShuman model (Figure 7) might be due to enhanced binding of tumor CD47 and human SIRPA that evokes strong signaling to inhibit xenogeneic tumor immunity.

In summary, we generated BRGShuman mice with a knock-in allele of the entire human SIRPA. Engraftment of human CB in BRGShuman mice was more efficient than in BRGSNOD mice in the bone marrow and in the periphery, and myeloid reconstitution was also significantly improved. The engraftment of AML cells and CRC cells was also more efficient in BRGShuman mice than in BRGSNOD mice. These data strongly suggest that the BRGShuman mouse should be very useful to establish future xenogeneic transplantation assays that are more realistic for the analysis of hematopoiesis, leukemogenesis, and tumorigenesis in humans.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yuichiro Semba, Masayasu Hayashi, Jun Odawara, and Yasuyuki Ohkawa for purification of the CD47-Fc protein and the Japanese Red Cross Kyushu Cord Blood Bank for providing CB samples.

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (18H02840, K.T.), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (16H06391, K.A.), and a grant from the Shin-nihon Foundation of Advanced Medical Treatment Research (Y.K.)

Authorship

Contribution: F.J., T.Y., and K.T. coordinated the project, designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; A.Y., T.N., M.N., C.I., T.O., K.M., and Y.K. performed experiments; and K.K., T. Maeda, T. Miyamoto, E.B., and K.A. designed the experiments, reviewed the data, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Koichi Akashi, Kyushu University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, 3-1-1 Maidashi, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka 812-8582, Japan; e-mail: akashi@med.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal