Key Points

Deep sequencing identifies a significant reservoir of subclonal mutations affecting key genes in CLL pathogenesis.

Convergent evolution of genetic lesions in tumor subclonal populations is recurrently found in CLL.

Abstract

Recent high-throughput sequencing and microarray studies have characterized the genetic landscape and clonal complexity of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Here, we performed a longitudinal study in a homogeneously treated cohort of 12 patients, with sequential samples obtained at comparable stages of disease. We identified clonal competition between 2 or more genetic subclones in 70% of the patients with relapse, and stable clonal dynamics in the remaining 30%. By deep sequencing, we identified a high reservoir of genetic heterogeneity in the form of several driver genes mutated in small subclones underlying the disease course. Furthermore, in 2 patients, we identified convergent evolution, characterized by the combination of genetic lesions affecting the same genes or copy number abnormality in different subclones. The phenomenon affects multiple CLL putative driver abnormalities, including mutations in NOTCH1, SF3B1, DDX3X, and del(11q23). This is the first report documenting convergent evolution as a recurrent event in the CLL genome. Furthermore, this finding suggests the selective advantage of specific combinations of genetic lesions for CLL pathogenesis in a subset of patients.

Introduction

The clinical course of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is very heterogeneous, ranging from indolent to highly aggressive refractory disease. Most CLL patients have early-stage disease at diagnosis but eventually progress to require treatment, and a majority will die of CLL or its complications.1-7 Randomized trials have established that chemoimmunotherapy combining fludarabine with rituximab improves response rates, progression-free survival, and overall survival.8-12 Despite significant progress in treatment options, disease relapse occurs in a majority of patients.

In the last 2 years, with the advent of high-throughput sequencing and microarray studies, tremendous advances in the understanding of genomic heterogeneity and clonal architecture of CLL have been achieved. We and others have characterized the genetic architecture of CLL through the course of the disease by analyzing multiple longitudinal samples.13-17 Overall, 2 major patterns of clonal evolution underlying the course of disease have been identified: linear and multibranching (see supplementary Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site). Linear evolution is characterized by the maintenance of an initial single clone, with subsequent acquisition in that clone of additional mutations, copy number abnormalities (CNAs), or both, whereas multibranching evolution is characterized by 2 or more genetic subclones that coexist and further evolve in parallel.18 Furthermore, chemotherapy has been identified as an accelerator of clonal evolution, and different patterns of repopulation post therapy were observed, going from stable equilibrium of subpopulations to alternated dominance between subclones over time.15

Most of these studies were based on heterogeneous CLL cohorts, with samples collected at different stages of the disease in patients receiving varying therapeutic approaches. In this study, we performed a longitudinal analysis with sequential leukemic samples obtained at comparable stages of the disease in a cohort of CLL patients undergoing homogenous treatment. Furthermore, a subset of cases was analyzed using deep sequencing to dissect the clonal complexity at higher sensitivity. We identified multiple cases of convergent evolution, whereby independent genetic lesions in the same genes were acquired in different subclones.

Materials and methods

Patients

All patients were treated with the “PCR” regimen, consisting of pentostatin (2 mg/m2), cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2), and rituximab (375 mg/m2) given intravenously on day 1 of a 21-day cycle for a maximum of 6 cycles.19 Responses were assessed by National Cancer Institute 1996 criteria.20 Of the 65 patients enrolled in the PCR trial, we identified 12 with blood samples available for at least 2 time points 6 months apart. Samples were collected at 3 possible time points of the disease: >6 months before enrollment in the PCR trial (ie, prebaseline); at the time of enrollment in the trial (ie, baseline); and samples corresponding to relapse collected >6 months after initial treatment under the PCR trial (ie, first relapse). Furthermore, in 2 patients, samples corresponding to relapses after secondary therapies were analyzed. Therefore, we analyzed 31 longitudinal tumor samples and their matched germline reference sample from 12 patients (Figure 1). Clinical information of the cohort is reported in supplementary Table 1. The study was performed under Institutional Review Board 2207-02, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Longitudinal analysis of uniformly treated CLL patients. Twelve cases of progressive CLL were analyzed by various techniques (aCGH, WES, and TDS) before and after therapy. The horizontal axis represents the timeline (in months) of sample collection. Each patient is presented as string, and the circles represent samples collected and the type of analysis performed. aCGH, array comparative genomic hybridization; TDS, targeted deep sequencing; WES whole exome sequencing.

Longitudinal analysis of uniformly treated CLL patients. Twelve cases of progressive CLL were analyzed by various techniques (aCGH, WES, and TDS) before and after therapy. The horizontal axis represents the timeline (in months) of sample collection. Each patient is presented as string, and the circles represent samples collected and the type of analysis performed. aCGH, array comparative genomic hybridization; TDS, targeted deep sequencing; WES whole exome sequencing.

Isolation of tumor and nontumor cells

B cells were enriched from peripheral blood mononuclear cells using the EasySep Human CD19+ Cell Enrichment Kit without CD43 Depletion. T cells were enriched using the EasySep Human CD3 Positive Selection Kit and subsequently used as germline samples in the sequencing studies. After cell enrichment, all fractions were stained by 4-color immunophenotypic analysis to assess sample purity. Based on fluorescence-activated cell sorting, we observed an average of 91% of cells CD19+/CD5+ (range 66%-99%) (supplementary Table 2). We used the values of the CD19+/CD5+ fraction to calculate the purity of the biopsy (leukemic B-cell fraction) and compensate for any significant contamination of nonclonal B cells in each sample. Allelic fraction (AF) correction was done using the following formula: corrected AF = initial AF × (100 ÷ percentage of the CD19+/CD5+ fraction). For the normal reference samples, we allowed less than 5% contamination with CD19+/CD5+ cells.

DNAs were extracted using the Puregene Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Extracted DNAs were fingerprinted to confirm the relationship between samples of the same patient (both tumor time points and the normal reference) and to rule out sample cross contamination between patients.

Paired-end whole exome sequencing

Genomic DNA from each sample was sheared and used for the construction of a paired-end sequencing library as described in the protocol provided by Illumina. The exome was captured using the SureSelect 50 Mb exome enrichment kit (Agilent Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 System. One hundred base pair paired-end reads were aligned to human genome hg19 using Novoalign (Novocraft Technologies, Malaysia). Quality of sequencing chemistry was evaluated using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Realignment and recalibration was done to take advantage of Best Practice Variant Detection v3 recommendations implemented in the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) software.21 After alignment, polymerase chain reaction duplication rates and percentage reads mapped on target were used to assess the quality of the data. Germline variant calling (both single-nucleotide and small insertions and deletions) was also done through GATK. Somatic single-nucleotide variations were genotyped using SomaticSniper,22 whereas insertions and deletions were called by GATK Somatic Indel Detector. Each variant in coding regions was functionally annotated by snpEFF23 and PolyPhen-224 to predict biological effects. Variant calls with total read depth less than 10X were excluded from further analysis for the lack of confidence in true variant calling. Finally, nonsynonymous variants of significant interest were visually inspected using Integrated Genomics Viewer.25 Raw sequencing data have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive under accession number phs000794.v1.p1.

Targeted sequencing

Targeted sequencing was performed using semiconductor-sequencing technology (Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine) following the manufacturer’s recommendations.26 Genes recurrently mutated in CLL were analyzed at high depth (the complete list of 24 genes analyzed is shown in supplementary Table 3). All the coding regions were amplified in 200-bp amplicons using customized oligos (Ion AmpliSeq Designer) and multiplex polymerase chain reaction with 10 ng of input DNA per reaction. The preparation and the enrichment of DNA libraries were done using the Ion OneTouch and the Ion OneTouch ES automated systems, respectively. Samples were sequenced using the 318 Chip (Life Technologies), with an average of 720X depth coverage per nucleotide. Variants were called using Ion Torrent Suite pipeline, and data were analyzed using Ion Reporter Software (Life Technologies).

Analysis of IGHV gene family

One microgram of total RNA was converted to complimentary DNA with the Bio-Rad iScript Select cDNA Synthesis Kit. Separate polymerase chain reactions were set up for each immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable (IGHV) gene family using sense primers to the Framework 1 region in conjunction with an immunoglobulin M antisense primer.27 Amplified products were isolated and purified by the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System. Polymerase chain reaction products were directly sequenced on an ABI PRISM 3730xl DNA Analyzer. Resulting sequences were aligned to germline sequences using ImMunoGeneTics (IMGT) Information System reference sets and IMGT/V-Quest software (http://www.imgt.org/IMGT_vquest/share/textes/).28

Copy number analysis

CNAs were analyzed using aCGH as previously published.13,29,30 Briefly, aCGH was performed using the SurePrint G3 Human Microarray Kit (Agilent Technologies). One microgram of tumor and reference DNA were independently fragmented with bovine DNase I (Ambion) for 12 minutes at room temperature. DNA samples from a pool of 9 female lymphoblastoid cell lines from the Coriell biorepository were used as the normal reference in the hybridization experiments. Tumor and reference samples were labeled with Alexa Fluor 5 and Alexa Fluor 3 dyes, respectively. Labeled reactions were cleaned up and hybridized at 65°C for 40 hours. Microarrays were scanned in a DNA Microarray Scanner, and features were extracted with Feature Extraction software (Agilent Technologies). The complete data set is accessible through the Gene Expression Omnibus database accession number GSE30217.

Extracted data were analyzed using the Genomic Workbench software (v5.0.14; Agilent Technologies). CNAs were calculated using the aberration detection module-1 algorithm31 with a threshold of 9 and 3-probe/0.25 log2 aberration filters. An interval-based text summary with all abnormalities was obtained and subsequently analyzed. Copy number changes were analyzed in sequential samples. Abnormalities that showed the same trend across sequential samples (ie, increased or decreased abundance) were initially grouped as part of the same subclone. Next, custom FISH probes were designed to confirm the coexistence of specific abnormalities in the same subclones and to quantify each subclone over time. See Braggio et al for detailed research strategy and methodologic information.13

Clustering analysis

We estimated clonal architecture using WES data generated from sequential patient samples. All 12 patients had clustering analysis done using all somatic mutations (intronic and exonic) with more than 30X coverage in the normal and tumor samples. Mutations with AF >90% in all time points analyzed were considered clonal mutations. In male patients, we corrected the AF of mutations in genes located in chromosome X, considering the presence of only one allele. Additionally, we used the aCGH data to distinguish the mutations located in regions with and without copy number changes. Overall, only 2% of mutations were found in regions with CNAs. These mutations were excluded from the clustering analysis for not having enough information to properly correct the AF. For the remaining mutations, clustering analysis was run using the mclust package (http://www.stat.washington.edu/mclust/) in the programming language R (http://www.r-project.org/). Mclust uses a normal mixture model combined with the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and uses default parameters to estimate the optimal number of clusters (subclones) and models of covariance structures to identify the best clustering model. The BIC value is the value of the maximized log-likelihood, with a penalty on the number of model parameters, and allows comparison of models with differing parameterizations, differing numbers of clusters, or both. We choose the largest BIC value when the most covariance models converge for the number of clusters. As a result, the allelic frequency and the trend of the change in sequential samples are used by mclust to distribute the mutations into different subclones (supplementary Figure 2A). We further verified the mclust findings with kernel density estimation (KDE), including only significant peaks (supplementary Figure 2B). KDE was run using bpkde package (http://cran.fhcrc.org/web/packages/bpkde/index.html) in R with bandwidth method32 and Gaussian smoothing kernel as parameters. We also confirmed mclust and KDE findings in each case by plotting the dynamics (trend) of all mutations through sequential samples as shown in supplementary Figure 2C and supplementary Figure 3. The results from the clustering analyses in all samples are reported in supplementary Table 4. The uncertainty value associated with the conditional probability of a particular mutation belonging to a particular subclone under the given allelic fractions distribution was obtained by subtracting the probability of belonging to a subclone for each mutation from 1. These values (confidence for clustering in a particular subclone) for each of the mutations are also reported in supplementary Table 4. In 42% of patients, the number of subclones identified was higher than our previous characterization of the same cohort by copy number changes (supplementary Figure 4).13

Results

Genomic landscape of CLL

We performed WES in 12 CLL patients, 6 with unmutated and 6 with mutated IGHV status. Clinical characteristics of the patients analyzed in this study are summarized in supplementary Table 1. In each patient, 2 to 4 longitudinal tumor samples and corresponding matched nontumor controls were analyzed (Figure 1). An average of 102-fold depth coverage was obtained, with an average of 80% of targeted regions covered at least 30X. The average transition-to-transversion ratio was 2.54. Overall, we detected a total of 136 somatic nonsynonymous single-nucleotide variations and 20 indels in 143 unique genes (median of 12.5 per patient, range 2-28). Cases of unmutated IGHV CLL showed 26 nonsynonymous mutations compared with 18 in mutated IGHV. The complete list of nonsynonymous mutations is included in supplementary Table 5. Recurrent CNAs were del(13q), found in 42% of patients; trisomy 12 (33%); del(8p) in 25%; and del(11q) and del(17p) in 17% each. Compared with previous studies, there is a higher prevalence of del(8p), which was acquired over time in 2 of 3 patients. CNAs are reported in supplementary Table 6.

Clonal architecture and clonal evolution before and after therapy

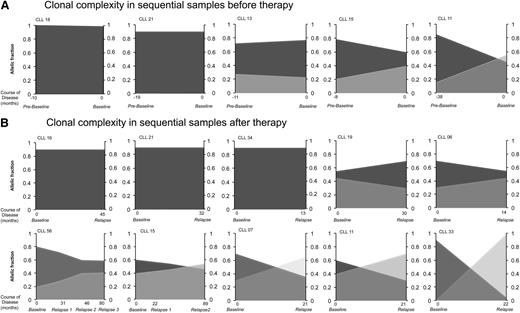

We found 2 patterns of clonal architecture through the course of the disease: linear evolution characterized by the existence of a unique initial clone that acquired additional mutations over time (4 of 12 patients, 33%), and multibranching evolution with 2 or more subclones fluctuating over time (67% of patients).18 We analyzed clonal complexity before therapy by analyzing sequential prebaseline and baseline samples available in 5 patients (with a median of 12 months between samples). We identified stable subclonal composition in 4 of 5 patients with no change in clonal dynamics from diagnosis to disease progression and start of therapy. In the remaining patient we noticed switches between major and minor subclonal populations (Figure 2A). All putative CNAs and mutations found in driver genes were present at prebaseline sample, and no further acquisition of driver mutations was identified with disease progression from prebaseline to baseline. For graphical presentation of subclonal composition, subclonal allelic fractions were proportionally adjusted in each tumor sample from each patient to obtain total tumor burden. Such normalized values were plotted for each patient (Figure 2).

Clonal architecture and evolution before and after therapy. (A) Patients with sequential samples analyzed before therapy. (B) Patients with sequential samples analyzed before therapy and after relapse of therapy. The horizontal axis represents the timeline (in months) of sample collection from these patients, where negative values represent time before PCR trial and positive values depict time after PCR trial. Different shades of gray represent different subclones. The vertical axis represents subclonal abundance.

Clonal architecture and evolution before and after therapy. (A) Patients with sequential samples analyzed before therapy. (B) Patients with sequential samples analyzed before therapy and after relapse of therapy. The horizontal axis represents the timeline (in months) of sample collection from these patients, where negative values represent time before PCR trial and positive values depict time after PCR trial. Different shades of gray represent different subclones. The vertical axis represents subclonal abundance.

Further, the effect of chemotherapy on clonal evolution was analyzed in 10 patients with available sequential samples before and after frontline therapy. In this homogenous cohort of uniformly treated patients, we identified disease progression and relapse associated with stable clonal architecture as well as clonal evolution. We identified 2 or more genetic subclones in 7 of 10 patients, whereas a single stable clone was identified through the course of disease in the remaining 3 patients. In 4 of 7 patients with multiple subclones, the subclonal dominance switched between time points before and after therapy (Figure 2B). In most patients, CNAs and/or mutations in putative driver genes were identified before therapy, whereas the acquisition of driver abnormalities associated with disease progression was identified in only 2 patients (CLL33 and CLL34). In both of these patients, subclones emerging after therapy acquired lesions in the normal allele of TP53, resulting in biallelic inactivation of the gene in relapse samples.

Identification of convergent evolution involving putative tumor-implicated genes

Interestingly, in 2 patients (CLL11 and CLL33) with multiple genetic subclones, we identified mutations affecting the same genes in different subclones (ie, convergent evolution). To better characterize the underlying genetic complexity, we performed targeted deep sequencing (average of 750X coverage) in sequential samples from both patients using a panel of 24 CLL putative genes (supplementary Table 2). In both patients, not only the original genetic findings were confirmed but also additional mutations were found, mostly in small subclones (0.3%-10% AF).

In patient CLL11, we identified 2 major subclones with alternated dominance between time points. One of the major subclones was characterized by the presence of nonsense mutations in NOTCH1 (p.Q2403X) and a frameshift indel in DDX3X (p.S62Lfs*32). The second subclone showed an independent frameshift indel in DDX3X (p.V345Vfs*19), two truncating mutations in the PEST domain of NOTCH1 (p.S2492X and p.P2514Rfs*4), and a frameshift indel in BIRC3 (p.Y533Yfs*34) (Figure 3). Clonal competition was seen between these 2 major subclones through the course of disease, each with a combination of independent mutations in NOTCH1 and DDX3X.

Genetic complexity and convergent evolution in patient CLL11. Different mutations affecting the same genes were identified in 2 independent subclones. Subclone A had mutations in NOTCH1 (p.Q2403X) and DDX3X (p.S62Lfs*32). Subclone B showed subclonal mutations in NOTCH1 (p.S2492X and p.P2514Rfs*4) and DDX3X (p.V345Vfs*19), and a frameshift deletion in BIRC3 (p.Y533Yfs*34). The horizontal axis represents the timeline of sample collection from prebaseline to baseline to relapse. The vertical axis represents the relative abundance of mutations in subclones. The approximate allelic fractions are shown for each mutation at different time points.

Genetic complexity and convergent evolution in patient CLL11. Different mutations affecting the same genes were identified in 2 independent subclones. Subclone A had mutations in NOTCH1 (p.Q2403X) and DDX3X (p.S62Lfs*32). Subclone B showed subclonal mutations in NOTCH1 (p.S2492X and p.P2514Rfs*4) and DDX3X (p.V345Vfs*19), and a frameshift deletion in BIRC3 (p.Y533Yfs*34). The horizontal axis represents the timeline of sample collection from prebaseline to baseline to relapse. The vertical axis represents the relative abundance of mutations in subclones. The approximate allelic fractions are shown for each mutation at different time points.

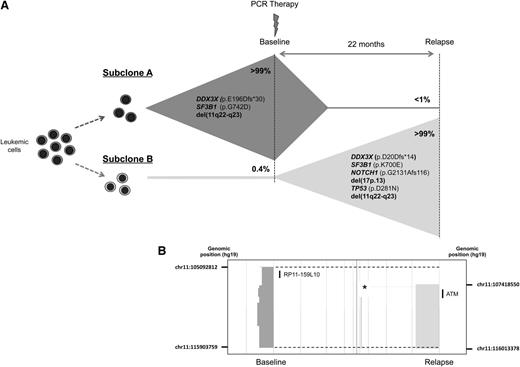

Another patient (CLL33) was characterized by the almost-complete subclonal replacement over time. Convergent evolution was observed between subclones with lesions in 2 independent genes and a chromosome deletion. At baseline, del(11q22) and mutations in SF3B1 (p.G742D) and DDX3X (p.E196Dfs*30) were identified in >99% of the allelic fraction. After relapse of therapy, the subclone was reduced below detection level of aCGH and WES with emergence of another, previously undetected subclone (Figure 4). The emergent subclone had independent mutations in SF3B1 (p.K700E) and DDX3X (p.D20Dfs*14), as well as different breakpoints on del(11q22), as was shown by aCGH (Figure 4B). Moreover, the emerging subclone showed additional lesions, including del(17p13), TP53 (p.D281N), and NOTCH1 (p.G2131Afs*116) mutations. Further, by deep sequencing, we confirmed the coexistence of subclones before and after therapy, with the minor subclone present in <1% of cells with the major subclone. Next, we performed the analysis of IGHV gene family to confirm the relationship between subclones. In both samples, the IGHV1-69 with 0% mutation and identical HCDR3 amino acid sequences indicates the presence of the same B-cell clone. This is an extraordinary and revealing example of convergent evolution affecting 3 independent driver genetic events (del[11q22], SF3B1, and DDX3X) in subclones of the same tumor.

Genetic complexity and convergent evolution in patient CLL33. (A) Convergent evolution was observed in 3 independent driver genes in 2 subclones. Subclone A had DDX3X (p.E196Dfs*30), SF3B1 (p.G742D), and del(11q22-23) genetic lesions. The emergent subclone B after relapse had independent mutations in DDX3X (p.D20Dfs*14) and SF3B1 (p.K700E), and del(11q22-q23). Additionally, del(17p13) and mutations in TP53 (p.D281N) and NOTCH1 (p.G2131Gfs*116) were identified in subclone B. (B) Different breakpoints for del(11q22-23) in subclones A and B were confirmed by aCGH (deleted regions in each time point are shown by dark gray and light gray blocks; breakpoints are indicated by broken lines). The genomic position of the breakpoints is shown at each time point. The deletion found at baseline was not found at relapse, as was confirmed using a custom FISH probe (RP11-159L10). Additionally, biallelic deletion affecting an already-defined copy number polymorphism in relapse samples but not in the baseline sample (marked with an asterisk) suggest that different chromosomes 11 (paternal versus maternal) were deleted in each subclone. The physical positions of probe RP11-159L10 and ATM are shown.

Genetic complexity and convergent evolution in patient CLL33. (A) Convergent evolution was observed in 3 independent driver genes in 2 subclones. Subclone A had DDX3X (p.E196Dfs*30), SF3B1 (p.G742D), and del(11q22-23) genetic lesions. The emergent subclone B after relapse had independent mutations in DDX3X (p.D20Dfs*14) and SF3B1 (p.K700E), and del(11q22-q23). Additionally, del(17p13) and mutations in TP53 (p.D281N) and NOTCH1 (p.G2131Gfs*116) were identified in subclone B. (B) Different breakpoints for del(11q22-23) in subclones A and B were confirmed by aCGH (deleted regions in each time point are shown by dark gray and light gray blocks; breakpoints are indicated by broken lines). The genomic position of the breakpoints is shown at each time point. The deletion found at baseline was not found at relapse, as was confirmed using a custom FISH probe (RP11-159L10). Additionally, biallelic deletion affecting an already-defined copy number polymorphism in relapse samples but not in the baseline sample (marked with an asterisk) suggest that different chromosomes 11 (paternal versus maternal) were deleted in each subclone. The physical positions of probe RP11-159L10 and ATM are shown.

Discussion

In this study, we characterized genomic heterogeneity and clonal architecture in high depth before and after therapy in a homogenous cohort of CLL patients with active disease. In accordance with previous studies, we identified most of the CLL cases associated with multiple genetically distinct subclones and changes in the clonal architecture in response to selection pressure of chemotherapy. In 2 cases analyzed by deep sequencing, we identified significant genetic heterogeneity, with several driver mutations found in small subclones (0.3%-10% of tumor burden). The most interesting finding of this study is the identification of convergent evolution in tumor subclonal populations. In Darwinian terms, evolutionary convergence is the phenomenon in which different species, responding to the same environmental pressures, come to evolve similar traits.

Considering cancer cells as ecosystems of evolving clones, “environmental pressures” of specific tumors might lead to the selective disruption in genes converging to dysregulation of specific pathways in several subclones. Evidence of convergent evolution has been identified in solid tumors, especially renal cancer, where deep genetic analysis has highlighted functional similarity among independent subclones harboring unrelated loss-of-function mutations in SETD2, KDM5C, and PTEN.33 Recurrent combinations of genetic lesions (CNAs and mutations) highlight the significance of complementing dysregulated pathways in disease pathology. Contrary to renal cancer, where unique or few genes/pathways are common to all cases, CLL is characterized by a heterogeneous genetic complexity (ie, no mutation is found in more than 20% of cases). Thus, the likelihood of the simultaneous presence of a combination of genetic lesions (mutations and/or CNAs) in 2 independent subclones is very low. Furthermore, the phenomenon affects multiple CLL putative genes, including DDX3X, NOTCH1, and SF3B1. Interestingly, this process seems to be of significance in disease development, because we recently identified a case of convergent evolution in early, premalignant-stage monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis of the disease. In that study, we identified 2 independent subclones with different mutations of DDX3X years before clinical manifestation of CLL.34 DDX3X, which is mutated in less than 3% of CLL patients,35 is the most commonly affected gene in cases with convergent evolution in this study. Overall, these findings suggest the selective advantage of specific genetic lesion combinations in a subset of CLL patients.

Subsequent steps in understanding the genetic basis of disease progression are to identify the selective growth advantage associated with these genetic lesions under selection pressure of therapy. Recently, subclonal status of driver mutations was proposed to be an independent risk factor for rapid disease progression in CLL.15 Furthermore, association of TP53 mutations with poor prognosis, irrespective of the subclone size, has been shown.36 In this study, we identified differential response of subclones with poor prognosis lesions after therapy. In 1 patient (CLL33), we found a small subclone (<1% of tumor cells) that became dominant after therapy. This subclone carried a mutation in NOTCH1, which is associated with poor outcome in CLL. Furthermore, another high-risk abnormality, such as biallelic impairment of TP53, was identified in the subclone after therapy. Another patient (CLL11) also showed one small subclones that, a priori, included a more aggressive genetic combination, including mutations in BIRC3 and NOTCH1; however, this malignant subclone remained stable in low allelic fraction 21 months after therapy. Therefore, further characterization of the genetic combinations of abnormalities found in CLL tumor subclones and their evolution over time is critical in order to determine associated risk of disease progression and relapse. Furthermore, this knowledge is critical for understanding the response of subclonal architecture and genetic heterogeneity to the selective pressure of chemotherapy.

In conclusion, the advent of deep sequencing has significantly increased the sensitivity of subclonal heterogeneity analyses in CLL, allowing us to identify a large reservoir of genetic variability with several driver genes found mutated in small subclones. Our data confirm that convergent evolution is a recurrent event in CLL.

Authorship

Contribution: J.O., D.V.D., T.S., R.F., N.E.K., and E.B. designed the research; J.O., J.A., C.S., S.S., R.T., K.R., and E.B. performed the work; J.O., J.A., and E.B. analyzed the data; and J.O. and E.B. wrote the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The PCR trial was funded with research support by Hospira. T.S. has received research funding from Hospira, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Celgene, and Cephalon. N.E.K. is on the data safety monitoring committee for Gilead and Celgene; and received research support from Pharmacyclics. R.F. has received a patent for the prognostication of multiple myeloma based on genetic categorization of the disease; and has received consulting fees from Medtronic, Otsuka, Celgene, Genzyme, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Onyx, Binding Site, Millennium, and Amgen. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Esteban Braggio, Mayo Clinic, 13400 East Shea Blvd, Collaborative Research Building, Room 3-029, Scottsdale, AZ 85259-5494; e-mail: braggio.esteban@mayo.edu.

Raw sequencing data reported in this article have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive database (accession number phs000794.v1.p1). The complete data set reported in this article has been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE30217).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Henry Predolin Foundation, the Marriott Specialized Workforce Development Awards in Individualized Medicine, the Fraternal Order of Eagles, and National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant CA95241.