Key Points

ATRA and ATO affect NPM1 protein levels in AML cells and induce cell growth inhibition and apoptosis.

AML cells with mutated NPM1 respond to ATRA/ATO, and this might be exploited therapeutically.

Abstract

Nucleophosmin (NPM1) mutations represent an attractive therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) because they are common (∼30% AML), stable, and behave as a founder genetic lesion. Oncoprotein targeting can be a successful strategy to treat AML, as proved in acute promyelocytic leukemia by treatment with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) plus arsenic trioxide (ATO), which degrade the promyelocytic leukemia (PML)–retinoic acid receptor fusion protein. Adjunct of ATRA to chemotherapy was reported to be beneficial for NPM1-mutated AML patients. Leukemic cells with NPM1 mutation also showed sensibility to ATO in vitro. Here, we explore the mechanisms underlying these observations and show that ATO/ATRA induce proteasome-dependent degradation of NPM1 leukemic protein and apoptosis in NPM1-mutated AML cell lines and primary patients’ cells. We also show that PML intracellular distribution is altered in NPM1-mutated AML cells and reverted by arsenic through oxidative stress induction. Interestingly, similarly to what was described for PML, oxidative stress also mediates ATO-induced degradation of the NPM1 mutant oncoprotein. Strikingly, NPM1 mutant downregulation by ATO/ATRA was shown to potentiate response to the anthracyclin daunorubicin. These findings provide experimental evidence for further exploring ATO/ATRA in preclinical NPM1-mutated AML in vivo models and a rationale for exploiting these compounds in chemotherapeutic regimens in clinics.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common acute leukemia in adults. The frontline treatment of AML consists of cytosine arabinoside and anthracyclines (eg, daunorubicin [DNR])–based chemotherapy. Standard chemotherapy ± hemopoietic stem cell transplantation1 can cure ∼40% to 50% of younger adults and 10% to 15% of elderly patients (>60 years old). Thus, developing novel therapeutic approaches is clearly needed.

AML is a molecularly heterogeneous disease. However, at present, the only highly effective molecular targeted therapy for AML is based on all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and/or arsenic trioxide (ATO) in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) with promyelocytic leukemia (PML)–retinoic acid receptor α (RARα) gene rearrangement.2

Nucleophosmin (NPM1) gene mutations represent the most frequent genetic lesion in AML accounting for ∼30% of adult AML.3 NPM1 is a ubiquitously expressed nucleolar phosphoprotein with nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling activity, involved in multiple cellular functions and essential for life.4,5 NPM1 mutations in AML are heterozygous and lead to NPM1 wild-type haploinsufficiency and cytoplasmic accumulation of the leukemic NPM1 mutant protein.4 Because NPM1 mutations are common, stable, and represent a founder genetic lesion in AML,6-8 they are an appealing therapeutic target. Therefore, efforts are ongoing to design new drugs able to interfere with the mutant and residual wild-type NPM1.9 Other studies searched for an association between NPM1-mutated AML and response to already available drugs. Interestingly, response to high-dose DNR in AML closely correlated with NPM1 mutations.10 Moreover, in some11,12 but not in other13,14 studies, NPM1-mutated AML appeared to benefit from ATRA as an adjunct to conventional chemotherapy. Clinical experiences with ATO in non-APL AML patients have been disappointing.15,16 However, it is still unclear whether ATO might exert some beneficial effects in the setting of specific AML genotypes. Interestingly, recently it was reported that AML cells carrying NPM1 mutations are more sensitive to ATO,17 and that the expression of NPM1 mutant protein itself, with its acquired C-terminus cysteine 288, sensitized AML cells to oxidative stress induced by prooxidant drugs such as arsenic.17 The fact that ATRA and/or ATO exert their antileukemic effects by degrading tumor-specific proteins (ie, PML-RARα, breakpoint cluster region [BCR]/abelson [ABL])18-20 led us to explore their biological effects in human AML cell lines and primary AML cells from patients carrying NPM1 gene mutations and whether these were associated with changes in NPM1 mutant leukemic protein levels. Here, we show that ATO/ATRA indeed induce proteasome-dependent degradation of NPM1 leukemic protein leading to cell growth inhibition and apoptosis in NPM1-mutated AML and provide a rationale to exploit these drugs in chemotherapeutic regimens in clinics.

Methods

Cell lines, human samples, and cell culture

The human AML cell lines OCI/AML3 and IMS-M2 (carrying NPM1 gene mutation A) and OCI/AML2 and U937 (with wild-type NPM1) were previously reported.21-23 The primary NPM1-mutated AML subcutaneous xenograft model (MONT) was obtained in our laboratory from NPM1-mutated AML cells of 1 patient propagated for years as subcutaneous xenograft in immunocompromised mice.24

Primary AML cells were obtained upon written informed consent from 25 NPM1-mutated and 19 NPM1 wild-type AML patients (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site) at the hematology institutes of University of Perugia and University of Catania (Italy). The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved (CEU2013-030) by the local ethics committee. Human primary AML cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation of either peripheral blood or bone marrow. Patients’ samples with <80% leukemic cells and <40% basal viability were excluded. Pharmacologic experiments were performed maintaining the cells at 1 × 106/mL to 2 × 106/mL in supplemented Iscove modified Dulbecco medium in standard culture conditions. AML was defined as NPM1 mutated or NPM1 wild-type based on cytoplasmic (NPMc+) or nuclear (NPMc−) expression of NPM1 at immunohistochemistry, which is predictive of NPM1 gene status.25 Expression of the NPM1 mutant protein was documented by western blot analysis with anti-NPM1 mutant specific antibodies, as previously reported.26

Drugs and cell treatments

All drugs were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). ATO was resuspended at 10 mM in 0.1 M NaOH and ATRA at 1 mM in 100% EtOH, as stock solutions. Further dilutions were performed in culture medium. DNR was diluted in 0.9% NaCl at 1 mM and used at the indicated final concentrations. For proteasome inhibition, cells were pretreated (6 hours) with 1 μM MG132. For reactive oxygen species (ROS) prevention, cells were pretreated (16 hours) with 20 mM N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC). For pharmacologic experiments, drugs were added in culture at the beginning of the experiment at the time indicated. For pan-caspase inhibition, a general caspase inhibitor, Z-VAD-FMK (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), was used as indicated.

Antibodies

The mouse monoclonal antibody recognizing specifically NPM1 wild type (NPMwt, Clone FC-61991; dilution 1:1000) was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); the rabbit polyclonal anti-human mutated NPM1 (NPMm) was previously described26 ; and the rabbit anti-human PML used for western blot (dilution 1:1500) was purchased from Jena Bioscience (Germany). The mouse monoclonal anti-human PML (PG-M3) was produced in our laboratory.27 The other antibodies are listed in the supplemental Materials and Methods.

Cell growth, cell proliferation assay, colony-forming unit assay, and apoptosis evaluation

Details are provided in the supplemental Materials and Methods.

Cell lysate preparation and western blot analysis

Cell lysate preparation and western blot analysis were performed according to standard procedures as described in the supplemental Materials and Methods.

Immunofluorescence and immunocytochemistry staining

PML immunofluorescence staining was performed using the primary mouse monoclonal anti-human PML antibody, PG-M327 hybridoma supernatant (1:8 dilution in 1% bovine serum albumin) according to standard procedures. Details are provided in the supplemental Materials and Methods. For simultaneous small ubiquitin-like modifier (Sumo)-1 detection, the rabbit anti-human Sumo1 antibody (1:500 dilution in 1% bovine serum albumin; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was used. For NPM1 wild-type detection, the mouse NPMwt, Clone FC-61991 (dilution 1:2000) was used. As secondary antibodies, either goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit Alexa-Fluor 568 (red) or Alexa-Fluor 488 (green) immunoglobulin G fluorescent antibody (Molecular Probes by Life Technologies) were used. Nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) in Prolong Gold mounting reagent (Molecular Probes by Life Technologies). Immunofluorescence images were collected by fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan) and processed with CellSens Digital Imaging Software (Olympus).

For PML immunocytochemistry analysis, cytospun cells were fixed in acetone for 10 minutes, and after incubation with the primary antibody (PG-M327 hybridoma supernatant, undiluted) and washing, signal was detected by Dako REAL Detection System, Alkaline Phosphatase/RED (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) (APAAP technique) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were counterstained with hematoxylin. Slides were mounted with Kaiser’s glycerol gelatin (Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ). Images were collected using an Olympus B61 microscope and a UPlan FI ×100/1.3 NA oil objective; Camedia 4040, Dp_soft Version 3.2; and Adobe Photoshop 7.0.

ROS detection

ROS detection was performed by flow-cytometric analysis using either dihydroethidium (DHE; for detection of ·O2− free radical) or 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA; for detection of H2O2 and ROO· free radical) (Sigma-Aldrich). Reagents were used freshly prepared by resuspension in dimethylsulfoxide as 10 mM stock. Cells were plated at 0.5 × 106/mL and incubated with different concentrations of ATO for the time indicated. Then, either DHE (3 µM) or H2DCFDA (5 µM) was added directly to cells in culture. Cells were then incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes, harvested, and directly analyzed by FACSCalibur flow cytometer using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were performed at least in triplicates, as indicated, with technical repetition when possible. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-tailed or 2-tailed paired Student t test with normal-based 95% confidence interval was applied for statistical analysis, as indicated. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

Results

Antileukemic activity of ATO and ATRA in NPM1-mutated AML cells

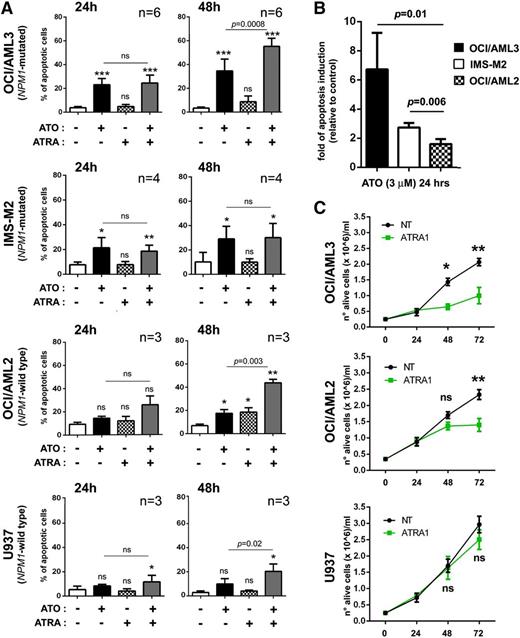

To test the antileukemic activity of ATO and/or ATRA in the setting of NPM1-mutated AML, we treated in vitro the 2 available human AML cell lines harboring NPM1 gene mutation, OCI/AML321,23 and IMS-M2,22 with pharmacologic doses of the 2 drugs, either alone or in combination, and compared the effects obtained in this setting with those obtained in NPM1 wild-type AML cells. Interestingly, pharmacologic doses of ATO (3 μM) induced apoptosis earlier and at higher levels in AML cell lines harboring mutated rather than germ-line NPM1 gene (OCI/AML3 and IMS-M2 vs OCI/AML2 and U937) (Figure 1A). Indeed, at 24 hours, ATO-induced apoptosis was significant only in OCI/AML3 and IMS-M2 (P = .0002 and P = .01, respectively) (Figure 1A). Analysis of the same data normalized to control and expressed as fold of apoptosis induction showed differences between NPM1-mutated and NPM1 wild-type cells that were statistically significant (Figure 1B). Cell proliferation assays confirmed the higher sensitivity of OCI/AML3 to ATO with a 50% inhibition concentration value of 2.8 μM at 24 hours, as compared with the other cell lines (supplemental Figure 1A). By contrast, proapoptotic effects of ATO on NPM1 wild-type AML cell lines were minimal also at later time points (Figure 1A and supplemental Figure 2A).

ATO/ATRA exert antileukemic activity in human NPM1-mutated AML cell lines. (A) Flow cytometric apoptosis assay (Annexin V/7AAD) on human AML cell lines harboring (OCI/AML3, IMS-M2) or not (U937, OCI/AML2) NPM1 mutation upon treatment with 3 μM ATO, 1 μM ATRA, or combination of both for 24 and 48 hours. Percentage of apoptotic cells at each time point is shown. Mean values ± SD from different experiments (OCI/AML3, n = 6; IMS-M2, n = 4; OCI/AML2, n = 3; U937, n = 3). Statistical significance for each treatment condition vs untreated control is indicated by asterisk(s). Two-tailed paired Student t test P values indicate statistical significance for ATO/ATRA cooperative effect vs ATO alone. (B) Graph expressing ATO-induced apoptosis at 24 hours from experiments in panel A as fold of induction, relative to control (untreated cells) (mean ± SD), with statistics between NPM1-mutated and NPM1 wild-type cells. Two-tailed paired Student t test P values are indicated. (C) Cell growth curves upon ATRA treatment (1 μM) in OCI/AML3 (mutated NPM1) vs OCI/AML2 and U937 (wild-type NPM1) human AML cell lines. Mean values of 3 independent experiments ± SD with statistics (2-tailed paired Student t test P values) are reported. (A,C) Significance levels are indicated by *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001; ns, not significant.

ATO/ATRA exert antileukemic activity in human NPM1-mutated AML cell lines. (A) Flow cytometric apoptosis assay (Annexin V/7AAD) on human AML cell lines harboring (OCI/AML3, IMS-M2) or not (U937, OCI/AML2) NPM1 mutation upon treatment with 3 μM ATO, 1 μM ATRA, or combination of both for 24 and 48 hours. Percentage of apoptotic cells at each time point is shown. Mean values ± SD from different experiments (OCI/AML3, n = 6; IMS-M2, n = 4; OCI/AML2, n = 3; U937, n = 3). Statistical significance for each treatment condition vs untreated control is indicated by asterisk(s). Two-tailed paired Student t test P values indicate statistical significance for ATO/ATRA cooperative effect vs ATO alone. (B) Graph expressing ATO-induced apoptosis at 24 hours from experiments in panel A as fold of induction, relative to control (untreated cells) (mean ± SD), with statistics between NPM1-mutated and NPM1 wild-type cells. Two-tailed paired Student t test P values are indicated. (C) Cell growth curves upon ATRA treatment (1 μM) in OCI/AML3 (mutated NPM1) vs OCI/AML2 and U937 (wild-type NPM1) human AML cell lines. Mean values of 3 independent experiments ± SD with statistics (2-tailed paired Student t test P values) are reported. (A,C) Significance levels are indicated by *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001; ns, not significant.

Given the positive clinical experiences with ATRA in NPM1-mutated AML patients,11,12 we explored whether ATRA could also exert specific antileukemic effects in this setting. Contrary to what we observed with ATO, ATRA alone, at pharmacologic doses (1 μM), did not induce early significant apoptosis in NPM1-mutated AML cell lines (Figure 1A). In OCI/AML3, induction of apoptosis was revealed and significant only at later time points (72 hours, supplemental Figure 2A). An earlier effect, preceding apoptosis, was instead observed on cell proliferation, which appeared efficiently inhibited at 48 hours (OCI/AML3, Figure 1C). By contrast, pharmacologic doses of ATRA were ineffective in IMS-M2 cell growth (data not shown). Data from cell proliferation assays showing ATRA 50% inhibition concentration at 72 hours of 0.3 μM in OCI/AML3 vs 2.7 μM in IMS-M2 are in keeping with these observations (supplemental Figure 1B). Also colony-forming-unit ability was abolished by ATRA, even at lower doses, in OCI/AML3, suggesting a likely long-term antileukemic effect in these responsive cells (supplemental Figure 2B). However, ATRA did not appear to exert a selective effect on NPM1-mutated AML cells, because, although ineffective against U937, it induced significant apoptosis and concomitant cell growth inhibition also in the NPM1 wild-type cell line OCI/AML2 at 72 hours (supplemental Figure 2A and Figure 1C).

Strikingly, when ATO and ATRA were combined, a cooperative action could be documented in AML cell lines other than APL, including the NPM1-mutated OCI/AML3 where ATO-induced apoptosis was markedly and significantly increased by cotreatment with ATRA for 48 (Figure 1A) and 72 hours (supplemental Figure 2A).

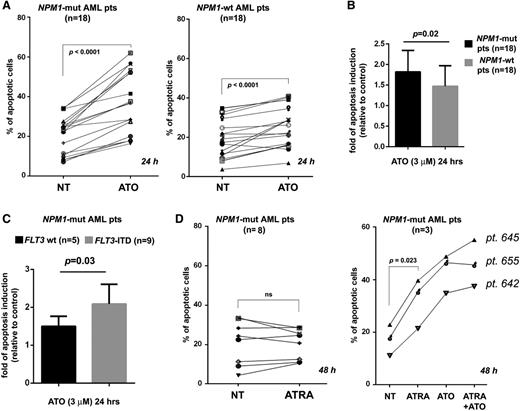

Importantly, results obtained on cell lines were confirmed in primary AML cells from 36 patients (n = 18 NPM1 mutated; n = 18 NPM1 wild type) (supplemental Table 1). Indeed, ATO-induced apoptosis levels were higher in NPM1-mutated than NPM1 wild-type cells (Figure 2A), with statistically significant difference (P = .02) (Figure 2B). Because most of our NPM1 wild-type AML samples carry karyotypic abnormalities (supplemental Table 1), we separately analyzed the 5 NPM1 wild-type AML patients with normal karyotype (supplemental Table 1) and confirmed the low/absent sensitivity to ATO (supplemental Figure 3). Notably, the proapoptotic effects of ATO in primary NPM1-mutated AML cells were observed also in Fms-like tyrosine-protein kinase 3 (FLT3)-ITD positive AML (n = 9, supplemental Table 1), which, with the caveat of the low number of cases, appeared even more sensitive than the FLT3-ITD negative (n = 5, supplemental Table 1) (Figure 2C). On the other hand, as expected, ATRA alone did not induce at all or significant apoptosis in the great majority of primary AML cell samples (8 out of 11 NPM1-mutated AML), as assessed at 48 hours (Figure 2D, left panel). Only in 3 out of 11 (27%) did ATRA induce early detectable apoptosis (mean fold of induction: 1.87 ± 0.12), which was increased by cotreatment with ATO in 2 patients (Figure 2D, right panel). Note that most of the primary AML cell samples treated with ATRA carried FLT3-ITD mutation (supplemental Table 1), which could explain their unresponsiveness to ATRA.

ATO/ATRA exert antileukemic activity in human primary NPM1-mutated AML cells. (A) Apoptosis rates (Annexin V/7AAD) of human primary AML cells from 36 patients (n = 18 NPM1 mutated; n = 18 NPM1 wild-type), untreated (NT) vs treated with 3 μM ATO for 24 hours. (B) Graph expressing ATO-induced apoptosis from experiments in panel A as fold of induction, relative to control (mean ± SD), with statistics between NPM1-mutated and NPM1 wild-type cells (2-tailed paired Student t test P value: P = .02). (C) Graph expressing ATO-induced apoptosis from experiments in panel A (left) as fold of induction, relative to control (mean ± SD), with statistics between FLT3 wild-type (FLT3 wt) (n = 5) and FLT3-ITD (n = 9) NPM1-mutated AML (2-tailed paired Student t test P value: P = .03). (D) Effects of ATRA (1 μM) treatment on apoptosis at 48 hours in primary human NPM1-mutated AML samples (n = 11): n = 8 nonresponders (left) and n = 3 responders (right). Effect of ATO/ATRA combination on ATRA responders is also shown (right).

ATO/ATRA exert antileukemic activity in human primary NPM1-mutated AML cells. (A) Apoptosis rates (Annexin V/7AAD) of human primary AML cells from 36 patients (n = 18 NPM1 mutated; n = 18 NPM1 wild-type), untreated (NT) vs treated with 3 μM ATO for 24 hours. (B) Graph expressing ATO-induced apoptosis from experiments in panel A as fold of induction, relative to control (mean ± SD), with statistics between NPM1-mutated and NPM1 wild-type cells (2-tailed paired Student t test P value: P = .02). (C) Graph expressing ATO-induced apoptosis from experiments in panel A (left) as fold of induction, relative to control (mean ± SD), with statistics between FLT3 wild-type (FLT3 wt) (n = 5) and FLT3-ITD (n = 9) NPM1-mutated AML (2-tailed paired Student t test P value: P = .03). (D) Effects of ATRA (1 μM) treatment on apoptosis at 48 hours in primary human NPM1-mutated AML samples (n = 11): n = 8 nonresponders (left) and n = 3 responders (right). Effect of ATO/ATRA combination on ATRA responders is also shown (right).

Overall, these findings indicate that although ATRA exerts a more general antileukemic effect in non-APL AML, NPM1-mutated AML displays a peculiar susceptibility to the antileukemic activity of ATO as compared with NPM1-wild-type AML, and this activity can be potentiated by ATRA.

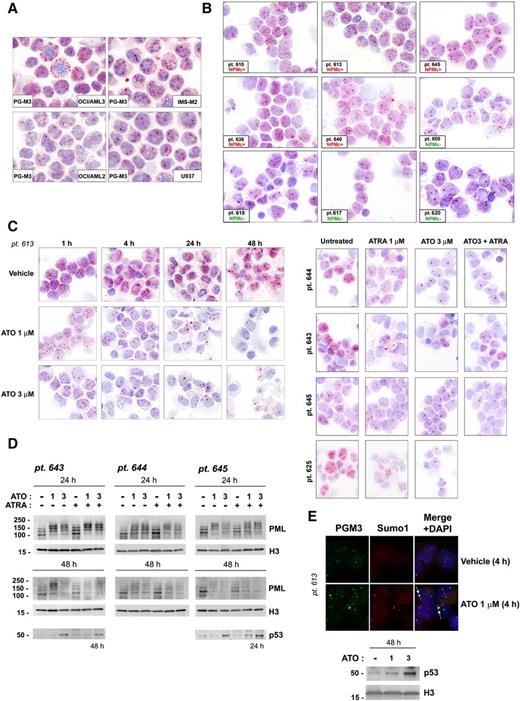

PML NB reorganization upon ATO/ATRA treatment in NPM1-mutated AML

Because ATO targets PML protein to nuclear bodies (NBs) and induces cell death in settings other than APL,28 we analyzed the effects of ATO on PML intracellular distribution in NPM1-mutated AML cells. Surprisingly, PML immunocytochemical staining revealed that basally AML cells harboring NPM1 mutation, either cell lines (OCI/AML3 and IMS-M2, Figure 3A) or primary AML patient cells (NPMc+, Figure 3B), have a partially altered PML nuclear distribution, showing PML bodies with variable size and staining intensity, and some with irregular shape in most of the leukemic cells and a more diffuse background microspeckled pattern in the nucleoplasm, as compared with AML cells with germ-line NPM1 (OCI/AML2 and U937 cell lines, Figure 3A; primary NPM1 wild-type AML, NPMc−, cells, Figure 3B). Interestingly, therapeutic ATO concentrations induced a dose- and time-dependent NB reorganization and changes in PML intracellular staining pattern, with progressive decrease in NB number, formation of larger-size NBs, and almost complete disappearance of the nucleoplasmic pattern observed in untreated cells (Figure 3C and supplemental Figure 4A-B). PML NB reorganization corresponded to detection by western blot analysis of slow-migrating PML species, likely representing SUMO/ubiquitin-conjugated PML29 (Figure 3D). Indeed, immunofluorescence staining with anti-PML and anti-SUMO1 antibodies of AML cells, either untreated or treated with ATO, confirmed that PML and SUMO1 colocalization markedly increased upon ATO treatment (Figure 3E and supplemental Figure 4B). The decreased staining observed in immunocytochemical analyses with time was consistent with the loss of PML protein, as demonstrated by western blot analysis after 24 and, particularly, 48 hours of ATO treatment (Figure 3D). ATRA alone did not induce major changes in PML staining pattern (Figure 3C, right panels) and protein levels (Figure 3D). Importantly, as expected, NB reorganization was associated with p53 upregulation in either primary (Figure 3D-E) or cell line (supplemental Figure 4C) AML cells.

ATO induces PML intracellular reorganization and downregulation associated with p53 upregulation in human NPM1-mutated AML cells. PML (PG-M3) immunocytochemical staining pattern in NPM1-mutated (OCI/AML3 and IMS-M2) vs NPM1 wild-type (OCI/AML2 and U937) AML cell lines (A) and representative NPM1-mutated (n = 5, NPMc+) vs NPM1 wild-type (n = 4, NPMc−) primary AML patients cells (B). Pt. followed by number indicates patient code. (C) PML immunocytochemical staining pattern changes upon ATO/ATRA treatment in primary NPM1-mutated AML patient cells. AML cells from pt. 613 were treated either with vehicle alone (vehicle control) or different ATO concentrations (1 and 3 μM) for the time indicated, and cytospin preparations stained for PG-M3 (left). See panel B, pt. 613, for comparison with the basal PG-M3 staining pattern. AML cells from pts. 643, 644, 645, and 625 were either left untreated or treated with ATO (3 μM), ATRA (1 μM), and ATO plus ATRA for 24 hours, and cytospin preparations stained for PG-M3 (right). (A-C) APAAP technique; hematoxylin counterstaining. Images were collected using an Olympus B61 microscope and a UPlan FI ×100/1.3 NA oil objective; Camedia 4040, Dp_soft Version 3.2; and Adobe Photoshop 7.0. (D) Western blot analysis of PML protein expression upon ATO/ATRA treatment in 3 representative NPM1-mutated AML patients samples. p53 protein levels in untreated vs treated AML cells are shown for pts. 643 and 645. The same membranes were blotted for histone H3 for loading control. (E) PML (PG-M3, secondary goat anti-mouse Alexa-Fluor 488, green) and Sumo1 (Sumo1, secondary goat anti-rabbit Alexa-Fluor 568, red) immunofluorescence staining upon ATO treatment in 1 representative NPM1-mutated AML patient (upper). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). White arrows indicate representative colocalization of Sumo1 and PML (yellow) in NBs. Images were collected by fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan) using a ×100/1.3 NA oil objective and processed with CellSens Digital Imaging Software (Olympus) and Adobe Photoshop 7.0. Western blot analysis for p53 upon ATO treatment on AML cells from the same patient (pt. 613, lower). Histone H3 was used as loading control.

ATO induces PML intracellular reorganization and downregulation associated with p53 upregulation in human NPM1-mutated AML cells. PML (PG-M3) immunocytochemical staining pattern in NPM1-mutated (OCI/AML3 and IMS-M2) vs NPM1 wild-type (OCI/AML2 and U937) AML cell lines (A) and representative NPM1-mutated (n = 5, NPMc+) vs NPM1 wild-type (n = 4, NPMc−) primary AML patients cells (B). Pt. followed by number indicates patient code. (C) PML immunocytochemical staining pattern changes upon ATO/ATRA treatment in primary NPM1-mutated AML patient cells. AML cells from pt. 613 were treated either with vehicle alone (vehicle control) or different ATO concentrations (1 and 3 μM) for the time indicated, and cytospin preparations stained for PG-M3 (left). See panel B, pt. 613, for comparison with the basal PG-M3 staining pattern. AML cells from pts. 643, 644, 645, and 625 were either left untreated or treated with ATO (3 μM), ATRA (1 μM), and ATO plus ATRA for 24 hours, and cytospin preparations stained for PG-M3 (right). (A-C) APAAP technique; hematoxylin counterstaining. Images were collected using an Olympus B61 microscope and a UPlan FI ×100/1.3 NA oil objective; Camedia 4040, Dp_soft Version 3.2; and Adobe Photoshop 7.0. (D) Western blot analysis of PML protein expression upon ATO/ATRA treatment in 3 representative NPM1-mutated AML patients samples. p53 protein levels in untreated vs treated AML cells are shown for pts. 643 and 645. The same membranes were blotted for histone H3 for loading control. (E) PML (PG-M3, secondary goat anti-mouse Alexa-Fluor 488, green) and Sumo1 (Sumo1, secondary goat anti-rabbit Alexa-Fluor 568, red) immunofluorescence staining upon ATO treatment in 1 representative NPM1-mutated AML patient (upper). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). White arrows indicate representative colocalization of Sumo1 and PML (yellow) in NBs. Images were collected by fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan) using a ×100/1.3 NA oil objective and processed with CellSens Digital Imaging Software (Olympus) and Adobe Photoshop 7.0. Western blot analysis for p53 upon ATO treatment on AML cells from the same patient (pt. 613, lower). Histone H3 was used as loading control.

These findings suggest that ATO targets PML in NPM1-mutated AML cells, and this may contribute to mediate ATO cell death induction through p53 pathway activation.30

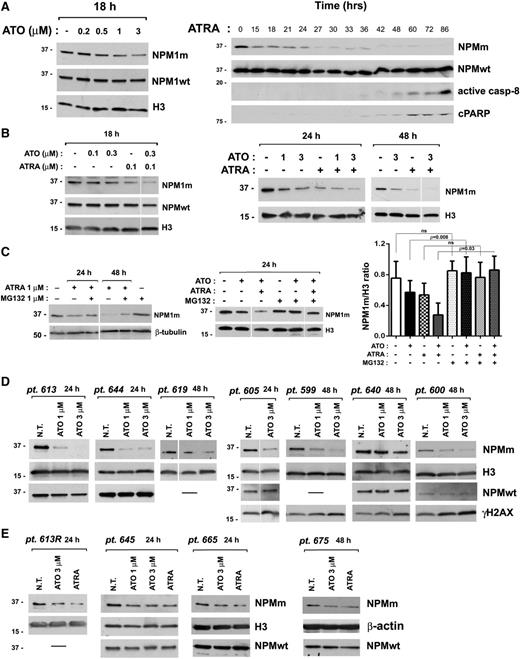

NPM1 mutant oncoprotein degradation upon ATO/ATRA treatment

Because ATO and ATRA exert their action through degradation of specific leukemic proteins (ie, PML-RARα, BCR-ABL),18-20 we explored whether these compounds could also target NPM1 mutant protein. Strikingly, ATO induced a dose-dependent downregulation of the NPM1 mutant protein in NPM1-mutated AML cell line OCI/AML3, whereas the wild-type protein levels remained mainly unchanged suggesting a selective effect of ATO on the NPM1 mutant oncoprotein (Figure 4A, left panel). NPM1 mutant downregulation upon ATO treatment was confirmed in 2 other NPM1-mutated AML cellular models (IMS-M2 and MONT,24 supplemental Figure 5A). Surprisingly, ATRA also induced a selective marked downregulation of NPM1 mutant oncoprotein, which in OCI/AML3 preceded apoptosis activation, as revealed by the later appearance of active caspase-8 fragment and cleaved poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase (PARP) at western blot analysis with specific antibodies (Figure 4A, right panel). The fact that NPM1 mutant downregulation was unaffected by pretreatment with a pan-caspase inhibitor further supports the view that it is independent of caspase activation (supplemental Figure 5B). Importantly, although not observed in IMS-M2 (supplemental Figure 5A), where ATRA was not effective, the downregulatory effect of ATRA on NPM1 mutant protein levels followed by cell growth inhibition was revealed also in the other NPM1-mutated AML cellular model, MONT24 (supplemental Figure 6A). Notably, cotreatment with ATO and ATRA induced in OCI/AML3 (Figure 4B) and in MONT, but not in IMS-M2 (supplemental Figure 5A), a further NPM1 mutant downregulation as compared with each single drug, in parallel with their effect on apoptosis (Figure 1A; supplemental Figures 2A and 6B). The observation that NPM1 mutant downregulation induced by ATRA, ATO, or their combination was reversed by pretreatment of cells with the proteasome-inhibitor MG132 suggests regulation at the posttranscriptional level (Figure 4C). Importantly, the effect of ATO on the NPM1 mutant protein levels was documented also in 11 out of 13 primary AML cell samples, in association with DNA damage induction (Figure 4D-E) and cell apoptosis (Figure 2A), independently of FLT3-ITD expression (see supplemental Table 1). On the other hand, the effect of ATRA was observed only in a portion (4 out of 8) of analyzed patient samples (Figure 4E). Note that these samples were all FLT3-ITD positive, suggesting that expression of FLT3-ITD does not influence the ATRA-mediated downregulation of NPM1 mutant oncoprotein, although it might counteract its antileukemic effects. Notably, NPM1 wild-type protein levels were confirmed to be mainly unchanged upon ATO/ATRA treatment in either NPM1-mutated or NPM1 wild-type primary and cell line AML cells (Figure 4 and supplemental Figure 5).

ATO/ATRA induce proteasome-dependent NPM1 mutant oncoprotein downregulation. (A) Western blot analysis of NPMm and NPMwt protein levels upon ATO (left) and ATRA (right) treatment in OCI/AML3. Active caspase-8 and cleaved PARP (cPARP) indicate apoptosis activation (right). (B) Western blot analysis of NPM1 mutant and wild-type protein levels upon ATO, ATRA, and ATO/ATRA combination at lower (left) and higher doses (right) in OCI/AML3. (C) Analysis by western blot of NPM1 mutant proteins levels upon ATO, ATRA, or ATO/ATRA combination on OCI/AML3 cells pretreated with proteasome inhibitor MG132. Band intensity quantification (NPM1 mutant/H3 ratio) from 3 independent experiments (mean ± SD). (A-C) Results are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. (D-E) Western blot analysis of the effects of ATO on NPM1 mutant protein levels in 11 primary NPM1-mutated AML patient cells. Downregulation of NPM1 mutant oncoprotein upon ATRA treatment in 4 NPM1-mutated AML patients is shown in panel E. Phosphorylation of histone H2AX (γH2AX) is expression of DNA damage. (A-E) Antibodies recognizing specifically the NPMm protein or NPMwt protein have been used, as described in “Methods.” Histone H3, β-tubulin, or β-actin expression was used as loading control. In all cases, membranes probed with the different antibodies were from the same gel. Vertical lines have been inserted in blot images to indicate repositioned lanes within the same gel.

ATO/ATRA induce proteasome-dependent NPM1 mutant oncoprotein downregulation. (A) Western blot analysis of NPMm and NPMwt protein levels upon ATO (left) and ATRA (right) treatment in OCI/AML3. Active caspase-8 and cleaved PARP (cPARP) indicate apoptosis activation (right). (B) Western blot analysis of NPM1 mutant and wild-type protein levels upon ATO, ATRA, and ATO/ATRA combination at lower (left) and higher doses (right) in OCI/AML3. (C) Analysis by western blot of NPM1 mutant proteins levels upon ATO, ATRA, or ATO/ATRA combination on OCI/AML3 cells pretreated with proteasome inhibitor MG132. Band intensity quantification (NPM1 mutant/H3 ratio) from 3 independent experiments (mean ± SD). (A-C) Results are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. (D-E) Western blot analysis of the effects of ATO on NPM1 mutant protein levels in 11 primary NPM1-mutated AML patient cells. Downregulation of NPM1 mutant oncoprotein upon ATRA treatment in 4 NPM1-mutated AML patients is shown in panel E. Phosphorylation of histone H2AX (γH2AX) is expression of DNA damage. (A-E) Antibodies recognizing specifically the NPMm protein or NPMwt protein have been used, as described in “Methods.” Histone H3, β-tubulin, or β-actin expression was used as loading control. In all cases, membranes probed with the different antibodies were from the same gel. Vertical lines have been inserted in blot images to indicate repositioned lanes within the same gel.

Interestingly, upon NPM1 mutant downregulation by either ATO or ATRA in OCI/AML3 and ATO alone in IMS-M2, the NPM1 wild-type protein, which is basally partly delocalized in the cytoplasm of leukemic cells by interaction with the mutant, was relocalized into the nucleus with remodeling of nucleoli, which increased in number and acquired a more regular round shape (Figure 5 and supplemental Figure 7).

ATO/ATRA induce NPM1 wild-type protein relocalization in the nucleus in NPM1-mutated OCI/AML3 cells. (A-B) Immunofluorescence staining for NPM1 wild-type protein using a specific mouse monoclonal antibody (NPMwt) (secondary goat anti-mouse Alexa-Fluor 488, green) of cytospin preparations from NPM1-mutated AML cell line OCI/AML3, untreated vs treated with ATO 3 μM, ATRA 1 μM, or ATO/ATRA combination for 24 hours. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Images were collected at fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan) using a ×100/1.3 NA oil objective and processed with CellSens Digital Imaging Software (Olympus) and Adobe Photoshop 7.0. White arrows in panel A point to representative NPM1 wild-type cytoplasmic positivity. White asterisk(s) in panel A indicate representative cells reproduced in panel B for details. Number of nucleoli/cell (means ± SD on 50 cells) is shown in the inset in panel A. Black asterisks indicate statistical significance.

ATO/ATRA induce NPM1 wild-type protein relocalization in the nucleus in NPM1-mutated OCI/AML3 cells. (A-B) Immunofluorescence staining for NPM1 wild-type protein using a specific mouse monoclonal antibody (NPMwt) (secondary goat anti-mouse Alexa-Fluor 488, green) of cytospin preparations from NPM1-mutated AML cell line OCI/AML3, untreated vs treated with ATO 3 μM, ATRA 1 μM, or ATO/ATRA combination for 24 hours. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Images were collected at fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan) using a ×100/1.3 NA oil objective and processed with CellSens Digital Imaging Software (Olympus) and Adobe Photoshop 7.0. White arrows in panel A point to representative NPM1 wild-type cytoplasmic positivity. White asterisk(s) in panel A indicate representative cells reproduced in panel B for details. Number of nucleoli/cell (means ± SD on 50 cells) is shown in the inset in panel A. Black asterisks indicate statistical significance.

Altogether, our data show that NPM1 mutant is targeted by ATO and, at least in some cases, also by ATRA, and, although probably not the only mechanism, its downregulation might contribute to the proapoptotic and/or antiproliferative effects of these drugs in NPM1-mutated AML. Collectively, these findings are reminiscent of the ATRA/ATO-induced PML/RARα degradation in APL.

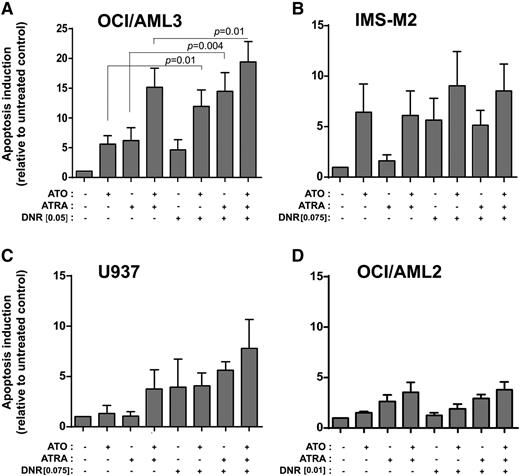

Increased DNR sensitivity upon ATO/ATRA pretreatment

We then explored whether ATO and/or ATRA, which here we show to induce NPM1 mutant downregulation, could sensitize NPM1-mutated OCI/AML3 cells to the anthracycline DNR, largely used in standard chemotherapy of AML. For this purpose, AML cell lines were treated with escalating doses of DNR, and the suboptimal doses in inducing apoptosis at either 24 or 48 hours (data not shown) were used for further experiments. Interestingly, pretreatment of OCI/AML3 with pharmacologic doses of ATO, ATRA, or their combination for 24 hours significantly increased apoptosis induced by DNR (Figure 6A). Similar, but less striking effects were obtained in the NPM1-mutated IMS-M2 cell line where ATO, leading to NPM1 mutant downregulation, but not ATRA, having no effect on NPM1 mutant protein levels, induced a reproducible, although not statistically significant, increase in apoptosis by DNR (Figure 6B). In the NPM1 wild-type AML cell lines, besides a slight effect of ATO/ATRA combination in U937, ATO/ATRA pretreatment did not show any effect on DNR sensitivity (Figure 6C-D).

Effect of ATO/ATRA on DNR sensitization of human AML cell lines. (A-B) Apoptosis rate (relative to untreated) by flow cytometric evaluation (Annexin V/7AAD) upon DNR treatment in OCI/AML3 (DNR 0.05 μM, 48 hours) (A) and IMS-M2 (DNR 0.075 μM, 48 hours) (B) NPM1-mutated AML cell lines pretreated with ATO, ATRA, and ATO/ATRA for 24 hours. (C,D) Apoptosis rate (relative to untreated) upon DNR treatment in U937 (DNR 0.075 μM, 48 hours) (C) and OCI/AML2 (DNR 0.01 μM, 48 hours) (D) NPM1 wild-type AML cell lines pretreated with ATO, ATRA, and ATO/ATRA for 24 hours. (A-D) Means of 3 independent experiments ± SD. Two-tailed paired Student t test significant P values are indicated (P < .05).

Effect of ATO/ATRA on DNR sensitization of human AML cell lines. (A-B) Apoptosis rate (relative to untreated) by flow cytometric evaluation (Annexin V/7AAD) upon DNR treatment in OCI/AML3 (DNR 0.05 μM, 48 hours) (A) and IMS-M2 (DNR 0.075 μM, 48 hours) (B) NPM1-mutated AML cell lines pretreated with ATO, ATRA, and ATO/ATRA for 24 hours. (C,D) Apoptosis rate (relative to untreated) upon DNR treatment in U937 (DNR 0.075 μM, 48 hours) (C) and OCI/AML2 (DNR 0.01 μM, 48 hours) (D) NPM1 wild-type AML cell lines pretreated with ATO, ATRA, and ATO/ATRA for 24 hours. (A-D) Means of 3 independent experiments ± SD. Two-tailed paired Student t test significant P values are indicated (P < .05).

Although observed mainly in OCI/AML3, these findings are in keeping with previous reports showing that downregulation of NPM1 sensitizes AML cells to chemotherapy31-35 and has clinical implications.

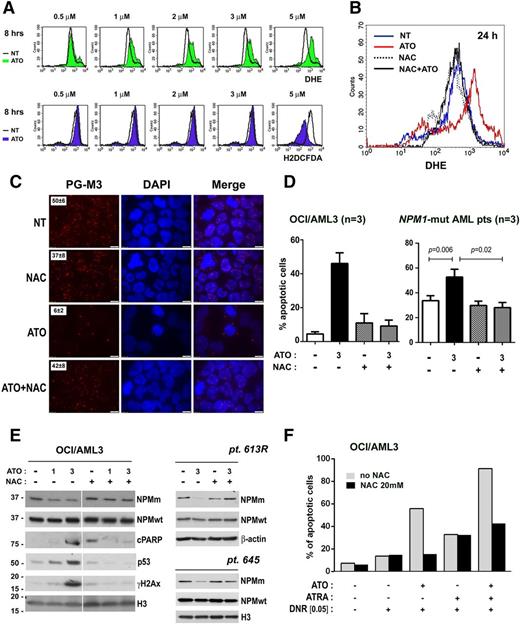

ROS dependence of ATO-induced NPM1 mutant degradation and cell apoptosis

Multiple biochemical mechanisms are involved in ATO-mediated cell death, including activation of stress signal transduction, mitochondria toxicity, and oxidative stress.36 ROS elicited by ATO target PML and mediate PML/RARα degradation and apoptosis in APL.36,37 Although pharmacologic doses of ATO induced dose-dependent intracellular ROS production in either NPM1-mutated or NPM1 wild-type AML cell lines (Figure 7A and supplemental Figure 8), its proapoptotic effects were evident only in NPM1-mutated AML cell lines. Therefore, we explored the role of ROS in mediating effects of ATO in NPM1-mutated AML. For this purpose, we analyzed whether ATO effects in OCI/AML3 were reversed by the ROS scavenger NAC, which efficiently prevented ROS production (Figure 7B). As expected, NAC pretreatment also prevented the PML sumoylation (data not shown) and NBs rearrangements observed upon ATO treatment (Figure 7C) and, strikingly, prevented ATO-induced cell apoptosis in OCI/AML3 (Figure 7D, left panel). These findings were confirmed in the IMS-M2 cell line (supplemental Figure 8 and data not shown) and, more importantly, in primary cells from 3 NPM1-mutated AML patients (Figure 7D, right panel). Furthermore, NPM1 mutant oncoprotein degradation induced by ATO was also prevented by NAC (Figure 7E) suggesting NPM1 mutant leukemic protein is a target of oxidative stress. Accordingly, p53 upregulation, PARP cleavage, and DNA damage induction were inhibited by NAC pretreatment (Figure 7E). Interestingly, NAC pretreatment also prevented the ATO-mediated, but not ATRA-mediated, sensitization of OCI/AML3 to DNR, further supporting the view that NPM1 mutant targeting by oxidative stress represents the main mechanism underlying ATO effects (Figure 7F).

ROS mediate PML NB rearrangements, cell apoptosis, NPM1 mutant oncoprotein degradation, and chemosensitization to DNR upon ATO treatment. (A) Flow cytometric detection of ROS in OCI/AML3 upon ATO treatment (DHE, green histograms, upper; and H2DCFDA, violet histograms, lower) compared with untreated cells (black line). (B) Effect of NAC pretreatment on ATO-induced ROS (as detected by DHE) at 24 hours in OCI/AML3. Histograms show levels of fluorescence of treated cells (red, ATO 3 μM; dashed line, NAC 20 mM; black, NAC + ATO) as compared with untreated cells (blue). (C) PML immunofluorescence staining (PG-M3, secondary goat anti-mouse Alexa-Fluor 568, red) of cytospin preparations of OCI/AML3: untreated cells (NT), 16 hours NAC 20 mM pretreatment (NAC), 8 hours ATO 3 μM treatment (ATO), and NAC pretreatment + ATO treatment (NAC + ATO). NBs/cell count (mean ± SD, on 50 cells) is shown in the inset. (D) Apoptosis assay (Annexin V/7AAD) on OCI/AML3 (left) and primary NPM1-mutated AML cells (n = 3) (right): untreated cells (white), 24-hour ATO 3 μM treatment (black), 16-hour NAC 20 mM pretreatment (checked), and NAC pretreatment + ATO treatment (gray). Means ± SD. Two-tailed paired Student t test P values are indicated. (E) Effect of NAC pretreatment on NPM1-mutant degradation. Western blot analysis of NPMm and NPMwt protein levels in OCI/AML3 (left) and 1 primary NPM1-mutated AML patient sample (pt. 613R, right). Activation of apoptosis (cPARP), p53 upregulation, and DNA damage induction (γH2AX) in OCI/AML3 are also shown (left). Histone H3 or β-actin expression was used, respectively, as loading control. In all cases, membranes probed with the different antibodies were from the same gel. (F) Effect of NAC pretreatment on chemosensitization to DNR by ATO/ATRA. Apoptosis flow cytometric evaluation (7AAD/Annexin V) upon 24-hour DNR treatment (0.05 μM) in OCI/AML3 cell lines pretreated with ATO (3 μM), ATRA (1 μM), and ATO/ATRA for 24 hours, previous incubation with or without NAC 20 mM for 16 hours.

ROS mediate PML NB rearrangements, cell apoptosis, NPM1 mutant oncoprotein degradation, and chemosensitization to DNR upon ATO treatment. (A) Flow cytometric detection of ROS in OCI/AML3 upon ATO treatment (DHE, green histograms, upper; and H2DCFDA, violet histograms, lower) compared with untreated cells (black line). (B) Effect of NAC pretreatment on ATO-induced ROS (as detected by DHE) at 24 hours in OCI/AML3. Histograms show levels of fluorescence of treated cells (red, ATO 3 μM; dashed line, NAC 20 mM; black, NAC + ATO) as compared with untreated cells (blue). (C) PML immunofluorescence staining (PG-M3, secondary goat anti-mouse Alexa-Fluor 568, red) of cytospin preparations of OCI/AML3: untreated cells (NT), 16 hours NAC 20 mM pretreatment (NAC), 8 hours ATO 3 μM treatment (ATO), and NAC pretreatment + ATO treatment (NAC + ATO). NBs/cell count (mean ± SD, on 50 cells) is shown in the inset. (D) Apoptosis assay (Annexin V/7AAD) on OCI/AML3 (left) and primary NPM1-mutated AML cells (n = 3) (right): untreated cells (white), 24-hour ATO 3 μM treatment (black), 16-hour NAC 20 mM pretreatment (checked), and NAC pretreatment + ATO treatment (gray). Means ± SD. Two-tailed paired Student t test P values are indicated. (E) Effect of NAC pretreatment on NPM1-mutant degradation. Western blot analysis of NPMm and NPMwt protein levels in OCI/AML3 (left) and 1 primary NPM1-mutated AML patient sample (pt. 613R, right). Activation of apoptosis (cPARP), p53 upregulation, and DNA damage induction (γH2AX) in OCI/AML3 are also shown (left). Histone H3 or β-actin expression was used, respectively, as loading control. In all cases, membranes probed with the different antibodies were from the same gel. (F) Effect of NAC pretreatment on chemosensitization to DNR by ATO/ATRA. Apoptosis flow cytometric evaluation (7AAD/Annexin V) upon 24-hour DNR treatment (0.05 μM) in OCI/AML3 cell lines pretreated with ATO (3 μM), ATRA (1 μM), and ATO/ATRA for 24 hours, previous incubation with or without NAC 20 mM for 16 hours.

Discussion

In approximately one-third of AMLs, NPM1 gene mutations lead to production of an oncoprotein, the NPM1 mutant leukemic protein, with altered intracellular distribution and likely new functions.3 Although the exact mechanisms underlying NPM1 mutation-driven leukemogenesis have not been yet completely elucidated, NPM1 mutations behave as founder genetic lesions in AML and thus represent a good target for therapy.9

Here we show for the first time that the NPM1 mutant oncoprotein can be a target of ATO and/or ATRA, which induce its proteasome-mediated degradation and cell apoptosis with cooperative effect. Moreover, NPM1 mutant oncoprotein degradation by ATO and/or ATRA could sensitize leukemic cells to the anthracyclin DNR, further providing a rationale for exploiting this well-tolerated therapeutic regimen in clinics, in the setting of NPM1-mutated AML. Our results indicate that NPM1-mutated AML cells, either cell lines or, more importantly, primary AML cells from patients, are more sensitive than NPM1 wild-type AML cells to the proapoptotic action of ATO and are in accordance with previous observation from Huang et al,17 which report that the higher sensibility of NPM1-mutated AML cells to ATO might be because of the expression of NPM1 mutant protein itself. Although our findings need to be validated on a larger cohort of patients, in our study, sensibility to ATO was confirmed independently of FLT3-ITD mutation, known to confer the worst prognosis,38 suggesting that even this particularly unfavorable genetic subgroup might benefit from ATO. ATRA seems to exert mainly antiproliferative effects whose mechanisms need to be clarified in the setting of NPM1-mutated AML. The higher variability in ATRA response observed in both cell lines and primary AML cells is possibly dependent on additional genetic alterations, which are worth exploring. Concerning FLT3-ITD, this might explain the scarce effects obtained with ATRA in our primary AML samples (mostly FLT3-ITD positive, see supplemental Table 1), in accordance to what previously reported in vitro31 and in patients.11,12 However, further studies in preclinical models of NPM1-mutated AML are needed to definitively establish the role of FLT3-ITD expression in ATO and/or ATRA response.

The biochemical mechanisms underlying ATO/ATRA-induced NPM1 mutant degradation need to be fully clarified. Here we show that degradation of NPM1 mutant oncoprotein induced by arsenic is triggered by oxidative stress, being prevented by pretreatment with the ROS scavenger NAC. This finding is in keeping with observation that NPM1 mutant protein might be susceptible to oxidative stress because of substitution of tryptophan 288 (W288) by cysteine at the C terminus of the protein.17 Oxidized proteins might be the final target of proteasome machinery,39 in accordance with what we have observed for NPM1 mutant degradation upon ATO and similarly to what reported for PML.18 The antileukemic effect of ATO might be also because of PML NB targeting, which we show to happen upon ATO in NPM1-mutated AML cells, and has been reported as an event associated with p53 pathway activation leading to cell death.28 The basal partially altered nuclear distribution of PML observed by immunocytochemistry in NPM1-mutated AML cells is a novel finding and will need further investigation. Interaction between NPM1 mutant protein and PML is worth analyzing. Furthermore, our finding that ATO induces PML protein downregulation in primary NPM1-mutated AML patient cells also has potential therapeutic relevance, given the role of PML in supporting self-renewal of leukemia cells.37

Mechanisms underlying the ATRA-induced proteasome-mediated NPM1 mutant degradation are unknown. However, although mainly revealed in cell line models, the observation that ATRA itself is able to induce NPM1 mutant downregulation and potentiate ATO- and/or DNR-induced apoptosis suggests its potential employment in combination regimens in clinics and gives some explanations to the clinical observation of beneficial effects of ATRA in NPM1-mutated AML patients.11,12 Evaluation of treatment-related long-term effects in primary AML patients cells in vitro appears difficult because of their high mortality in standard culture conditions, particularly at later time points. Murine models of NPM1-mutated AML40 will help in further exploring antileukemic activity of ATO/ATRA and defining effective combination regimens.

Our results suggest that ATO and ATRA are potential drugs for a molecular targeted-based therapy in NPM1-mutated AML leading to NPM1 mutant oncoprotein degradation. Evidence that NPM1 mutant downregulation can be a suitable way to target NPM1-mutated AML cells comes also from previous reports showing that NPM1 mutant silencing either by drugs (ie, deguelin,33 and (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate34 ) or inhibitory RNA31 leads to apoptosis and sensitizes cells to chemotherapeutics.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank patients and the personnel of Hematology Clinical Unit at “Santa Maria della Misericordia” Hospital of Perugia and Catania Hospital for providing samples, and Mrs. Claudia Tibidò for secretarial assistance; Prof H. G. Drexler (German Cancer Research Center, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) for the kind gift of OCI/AML3 and OCI/AML2 cell lines; Prof D. G. Tenen (Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, National University of Singapore, Singapore) for the kind gift of IMS-M2 cell line; Drs Francesca Strozzini, Alessandra Pucciarini, and Barbara Bigerna for the maintenance of MONT xenograft murine model; and the personnel of the Animal Facility (University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy).

This work was supported by the Associazione Italiana Ricerca Cancro (AIRC, IG 2013 n.14595), Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Perugia (grant 2010.011.0391), and Italian Minister of Health, Project “Ricerca Finalizzata 2008” (grant RF-UMB-2008-1142331).

Authorship

Contribution: M.P.M. designed the study, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; B.F. supervised the study and wrote the manuscript; I.G., F. Mezzasoma, and F. Milano performed experiments, analyzed data, and contributed to writing the manuscript; S.P., F. Mulas, R.R., and V.P. performed experiments and analyzed data; R.P. and A.T. performed immunocytochemistry and immunohistochemistry analyses; C.V., L.B., and F.D.R. provided AML patient samples and information and contributed to discussion of findings; and E.T. and P.S. contributed to analysis and discussion of data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.F. applied for a patent on the clinical use of NPM1 mutants. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Brunangelo Falini, Institute of Hematology, CREO, University of Perugia, Ospedale S. Maria della Misericordia, S. Andrea delle Fratte, 06132 Perugia, Italy; e-mail: brunangelo.falini@unipg.it; and Maria Paola Martelli, Institute of Hematology, CREO, University of Perugia, Ospedale S. Maria della Misericordia, S. Andrea delle Fratte, 06132 Perugia, Italy; e-mail: mpmartelli@libero.it.

References

Author notes

I.G., F. Mezzasoma, and F. Milano contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal