Key Points

Daratumumab plus chemotherapy may effectively bridge children and young adults with relapsed/refractory T-cell ALL/LL to HSCT.

No new safety concerns were identified with daratumumab treatment in children and young adults with B-cell ALL or T-cell ALL/LL.

Visual Abstract

Patients with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) or lymphoblastic lymphoma (LL) have poor outcomes compared with newly diagnosed, treatment-naïve patients. The phase 2, open-label DELPHINUS study evaluated daratumumab (16 mg/kg IV) plus backbone chemotherapy in children with relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL (n = 7) after ≥2 relapses, and children and young adults with T-cell ALL (children, n = 24; young adults, n = 5) or LL (n = 10) after first relapse. The primary end point was complete response (CR) in the B-cell ALL (end of cycle 2) and T-cell ALL (end of cycle 1) cohorts, after which patients could proceed off study to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). Seven patients with advanced B-cell ALL received daratumumab with no CRs achieved; this cohort was closed because of futility. For the childhood T-cell ALL, young adult T-cell ALL, and T-cell LL cohorts, the CR (end of cycle 1) rates were 41.7%, 60.0%, and 30.0%, respectively; overall response rates (any time point) were 83.3% (CR + CR with incomplete count recovery [CRi]), 80.0% (CR + CRi), and 50.0% (CR + partial response), respectively; minimal residual disease negativity (<0.01%) rates were 45.8%, 20.0%, and 50.0%, respectively; observed 24-month event-free survival rates were 36.1%, 20.0%, and 20.0%, respectively; observed 24-month overall survival rates were 41.3%, 25.0%, and 20.0%, respectively; and allogeneic HSCT rates were 75.0%, 60.0%, and 30.0%, respectively. No new safety concerns with daratumumab were observed. In conclusion, daratumumab was safely combined with backbone chemotherapy in children and young adults with T-cell ALL/LL and contributed to successful bridging to HSCT. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03384654.

Introduction

Although newly diagnosed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and lymphoblastic lymphoma (LL) are largely curable disorders, 10% to 25% of patients become refractory to, or relapse after, frontline treatment,1-5 and relapsed/refractory disease is often associated with poor outcomes, particularly for T-cell disease.6-12 Treatment of relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL has improved with the development of immunotherapeutic approaches, including blinatumomab, inotuzumab ozogamicin, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.6,7,13-15 However, treating relapsed childhood T-cell ALL/LL is challenging because of poor responses to standard reinduction regimens and a lack of immune targets.1,4-6,16 For example, in a phase 2 study, nelarabine (ara-G prodrug with toxicity toward T lymphoblasts) exhibited activity in relapsed/refractory childhood T-cell ALL, with response rates (complete response [CR] + partial response [PR]) of 55% after first relapse and 27% after second relapse; however, 18% of patients experienced grade ≥3 neurotoxicity.17 In the phase 1 NECTAR study of relapsed/refractory childhood T-cell ALL/LL, nelarabine plus etoposide/cyclophosphamide resulted in a response rate (CR + PR) of 38%, with 13% of patients experiencing grade 3/4 neurotoxicity.18 The addition of bortezomib (proteasome inhibitor) to chemotherapy may be a more effective and tolerable treatment for ALL, as demonstrated by the favorable CR rate of 68% observed in the phase 2 AALL07PI study in first-relapse childhood/young adult T-cell ALL.9 However, treating this population remains challenging because of high rates of second relapse and toxic reinduction regimens, and alternative therapies with improved safety profiles are needed.

CD38 is highly expressed on T-cell ALL blasts and, to a lesser degree, on B-cell ALL blasts,19,20 providing the rationale for the use of daratumumab, a human immunoglobulin Gκ monoclonal antibody targeting CD38 with direct on-tumor21-24 and immunomodulatory25-27 mechanisms of action. Daratumumab is approved as monotherapy and in combination with standard-of-care regimens for newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma and in combination with standard-of-care regimens for systemic light chain amyloidosis.28,29 Furthermore, daratumumab demonstrated activity in patient-derived preclinical xenograft models of T-cell ALL.19,30

The phase 2 DELPHINUS study evaluated daratumumab plus vincristine/prednisone in childhood B-cell ALL after ≥2 relapses and daratumumab plus vincristine/prednisone/pegylated-asparaginase/doxorubicin reinduction in childhood and young adult T-cell ALL/LL in first relapse.

Methods

Trial design and oversight

DELPHINUS (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03384654) was an open-label, multicenter, phase 2 study initiated on 5 June 2018, and completed on 22 September 2022. The study had 2 stages: stage 1 evaluated initial safety and efficacy in children (aged 1-17 years) with B-cell or T-cell ALL. Enrollment into stage 2 began after confirmation of the safety and daratumumab dose in stage 1 and also included young adults (aged 18-30 years) with T-cell ALL or LL.

The protocol, its amendments, and informed consent forms were approved by the institutional review board/independent ethics committee at each site, and all patients or their legal guardians provided written informed consent or assent (when applicable). The study was conducted in accordance with the current International Council for Harmonization guidelines on Good Clinical Practice and applicable regulatory and country-specific requirements, consistent with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

Full eligibility criteria are summarized in the supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website. Briefly, eligible patients were aged 1 to 30 years and had documented B-cell ALL after ≥2 relapses, were refractory to 2 prior induction regimens with ≥5% bone marrow blasts or T-cell ALL/LL in first relapse, or were refractory to 1 prior induction/consolidation regimen with ≥5% bone marrow blasts for ALL or biopsy-proven LL with radiologically measurable disease. Patients were excluded if they had received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) ≤3 months before screening, immunosuppression after HSCT ≤1 month before study entry, prior cancer immunotherapy ≤4 weeks before enrollment, or blinatumomab ≤2 weeks before enrollment; had infant leukemia (aged <1 year at initial diagnosis); or had Philadelphia chromosome–positive B-cell ALL.

Study treatment

Daratumumab infusion rates are described in supplemental Table 1, and doses and schedules of all treatment regimens are described in supplemental Table 2. Briefly, patients with B-cell ALL received daratumumab (16 mg/kg IV weekly on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 of cycles 1 and 2; then every 2 weeks for 8 doses; followed by every 4 weeks thereafter) plus vincristine, prednisone, and intrathecal methotrexate.

In cycle 1, patients with T-cell ALL/LL received daratumumab (16 mg/kg IV weekly on days 1, 8, 15, and 22) plus doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, pegylated-asparaginase, and intrathecal methotrexate. Those with M2 (5%-25% lymphoblasts) or M3 (>25% lymphoblasts) bone marrow status could start cycle 2 therapy immediately after completion of cycle 1. For patients with M1 (<5% lymphoblasts) bone marrow status, peripheral recovery to absolute neutrophil count of >0.75 × 109/L and platelets of >75 × 109/L were required to initiate cycle 2 (consisting of daratumumab [same as cycle 1] plus methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, and 6-mercaptopurine), which was optional to allow further treatment for those who did not achieve cycle-1 CR or for response consolidation before HSCT.

Preinfusion and postinfusion medications were administered to mitigate the frequency of infusion-related reactions (IRRs) (see supplemental Methods). Patients received age- and risk-adjusted intrathecal therapy with methotrexate if negative for central nervous system involvement or methotrexate, hydrocortisone, and cytarabine for patients with central nervous system–positive disease. Patients achieving CR after cycles 1 or 2 could proceed to HSCT off study at investigator discretion. Patients who achieved CR and required a short treatment interval for bridging before HSCT could switch to a continuation phase of daratumumab 16 mg/kg IV weekly for 4 doses after completing cycle 1 or every 2 weeks for 2 doses after completing cycle 2. There was a recommended 2-week interval from the last daratumumab dose to initiation of conditioning therapy for HSCT. Patients not achieving CR or proceeding to HSCT at the end of cycle 2 discontinued study treatment and entered follow-up.

End points and assessments

Response was measured at the end of each cycle by local bone marrow morphology and hematology assessment. The primary end point was the CR rate for patients with B-cell ALL within 2 cycles of therapy or for patients with T-cell ALL at the end of cycle 1, defined as <5% bone marrow blasts, no evidence of circulating blasts or extramedullary disease, and full recovery of absolute neutrophil counts (>1.0 × 109/L) and platelets (>100 × 109/L).31 Secondary end points included overall response rate (ORR; CR + CR with incomplete hematologic recovery [CRi] at any time before the start of subsequent therapy or HSCT for ALL,31 and as CR + PR for LL32); event-free survival (EFS; time from date of first treatment to first documented treatment failure, date of relapse after achieving CR, or death due to any cause); relapse-free survival (RFS; time from achievement of CR to relapse or death due to any cause); overall survival (OS); minimal residual disease (MRD)–negativity rate (<0.01% measured centrally by flow cytometry using bone marrow aspirate and assessed at the end of cycles 1 and 2 and at 30 days [+7 days] after the last dose of study treatment, before initiating subsequent treatment and/or HSCT; see supplemental Methods for details); and allogeneic HSCT rate (after daratumumab treatment). Progressive disease was defined as a ≥25% increase in peripheral or bone marrow blasts, or new extramedullary disease. Refractory ALL was defined as a lack of CR without meeting the criteria for progressive disease.

Daratumumab pharmacokinetics (PKs) were evaluated in serum samples obtained predose and at end of infusion (EOI) on day 1 of cycles 1 and 2 and on day 22 of cycle 2 (T-cell cohorts only), end of treatment, and posttreatment week 8. The presence of anti-daratumumab antibodies was evaluated in serum samples obtained before dose on day 1 of cycles 1 and 2, end of treatment, and posttreatment week 8. Daratumumab concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were evaluated before dose on day 1 of cycles 1 and 2 in the B-cell cohort and before dose on days 1 and 15 of cycle 1 and days 2 and 15 of cycle 2 in the T-cell cohorts. As an exploratory objective, CD38 expression at study entry and subsequent relapse was assessed by flow cytometry on bone marrow aspirate; however, no predetermined CD38 expression was required for patient eligibility.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were graded by severity according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.03.

Statistical analyses

Using a 1-sided α of 5%, there was 80% power to show the true CR rate was >15% in childhood B-cell ALL if 25 patients were enrolled and the true CR rate was >30% in childhood T-cell ALL if 24 patients were enrolled. In stage 2, up to 10 young adults with T-cell ALL and 10 patients with T-cell LL were enrolled to evaluate safety and efficacy in these populations.

Efficacy and safety analyses were conducted in all patients who received ≥1 daratumumab dose. Analysis of CR rate included calculation of a 2-sided 90% Clopper-Pearson exact confidence interval for all patients and a P value to test the hypothesis of a CR rate of >15% in childhood B-cell ALL and >30% in childhood T-cell ALL (see supplemental Methods). Two-sided 90% Clopper-Pearson confidence intervals were calculated for ORR, MRD-negativity rate, and HSCT rate. Kaplan-Meier methods were used to estimate the distribution of EFS, RFS, and OS for each cohort. All statistical testing was performed using a 1-sided test at a 5% significance level unless otherwise noted. Daratumumab serum and CSF concentrations at each sampling time point were evaluated in all patients who received ≥1 daratumumab dose and provided a postbaseline serum or CSF sample and were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Results

B-cell cohort

Of 8 patients screened for B-cell ALL, 7 were enrolled and treated with daratumumab plus chemotherapy (supplemental Figure 1); demographic and baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Median time from initial diagnosis to first daratumumab dose was 2.7 years, and the median prior lines of therapy was 2.0, with prior systemic regimens commonly including blinatumomab (n = 4), CAR T-cell infusion (n = 2), and/or inotuzumab ozogamicin (n = 2). Six (85.7%) patients previously achieved CR on their first prior therapy but subsequently relapsed; 1 patient’s prior response and relapse status were unknown. Three (42.9%) patients had previously received allogeneic HSCT. Median time since last relapse/refractory disease to first daratumumab dose was 15 days. Baseline expression of CD38 was observed for all evaluable patients with B-cell ALL, but levels were variable (supplemental Figure 2).

Median treatment duration was 1.2 months (range, 0.8-2.3), and the median duration of follow-up was 3.2 months (range, 1.0-4.7). All 7 patients received cycle 1 treatment and 4 patients continued treatment in cycle 2. No patient achieved CR within 2 treatment cycles; 1 patient achieved CRi, 3 patients had refractory ALL, and 3 patients had progressive disease as their best response. All patients discontinued daratumumab and chemotherapy because of progressive disease (n = 5), death (due to progressive disease, n = 1), or physician’s decision (n = 1). This cohort was closed, and no additional efficacy end points are presented.

T-cell cohorts

A total of 39 patients were enrolled in the T-cell cohorts, including 24 children with T-cell ALL, 5 young adults with T-cell ALL, and 10 patients with T-cell LL (supplemental Figure 1). The majority of patients were male and White, and the median ages were 10.0, 23.0, and 14.5 years for childhood T-cell ALL, young adult T-cell ALL, and T-cell LL, respectively (Table 1). Baseline cytogenetics are summarized in supplemental Table 3. Median times from initial diagnosis to first daratumumab dose were 2.5 years for childhood T-cell ALL, 0.6 year for young adult T-cell ALL, and 0.8 year for T-cell LL. All patients with T-cell ALL/LL had previously received 1 prior line of therapy and subsequently relapsed, with median times from end of prior systemic therapy to relapse/progression of 12.4 months (range, 0-47.1) for childhood T-cell ALL, 0.1 month (range, 0-29.3) for young adult T-cell ALL, and 0.5 month (range, 0-39.1) for T-cell LL. CR at any time on their first prior therapy was previously achieved in 18 (75.0%) children with T-cell ALL, 2 (40.0%) young adults with T-cell ALL, and 5 (50.0%) patients with T-cell LL. Three (12.5%) children with T-cell ALL had previously received allogeneic HSCT. Median times since last relapse/refractory disease to first daratumumab dose were 8.5, 7.0, and 11.0 days for childhood T-cell ALL, young adult T-cell ALL, and T-cell LL, respectively.

CD38 was expressed at baseline in all evaluable patients with T-cell ALL/LL, but levels were variable and daratumumab exposure was associated with reduced CD38 expression, which remained low from the first disease evaluation onward for the duration of treatment in all cohorts (supplemental Figure 2). Mean CD38 expression in childhood T-cell ALL was 20 154 molecules of equivalent soluble fluorochrome among responders (achieved CR/CRi) and 12 002 molecules of equivalent soluble fluorochrome among nonresponders (supplemental Figure 3).

Median treatment durations were 2.2 months (range, 0.5-2.9) for childhood T-cell ALL, 1.4 months (range, 1.0-2.1) for young adult T-cell ALL, and 2.1 months (range, 0.8-2.3) for T-cell LL; and median follow-up times were 37.5 (range, 0.8-45.7), 31.7 (range, 2.6-31.7), and 23.0 (range, 1.6-25.3) months, respectively. Treatment duration and other key milestones are shown in supplemental Figure 4 for each patient with T-cell ALL/LL. All patients with T-cell ALL/LL were treated in cycle 1; and 18 (75.0%) children with T-cell ALL, 4 (80.0%) young adults with T-cell ALL, and 6 (60.0%) patients with T-cell LL were treated in cycle 2. Seven children with T-cell ALL proceeded to the daratumumab continuation phase as a bridge to HSCT, including 1 patient after cycle 1 and 6 patients after cycle 2. One young adult with T-cell ALL proceeded to the daratumumab continuation phase after cycle 1, and no patient with T-cell LL received daratumumab continuation. Eight children with T-cell ALL, 3 young adults with T-cell ALL, and 4 patients with T-cell LL discontinued daratumumab and backbone chemotherapy; reasons are described in supplemental Figure 1.

Efficacy

Supplemental Figure 4 shows the timing of first CR, first MRD negativity, HSCT, relapse, start of subsequent antileukemia therapy, and death relative to study treatment initiation for each patient with T-cell ALL/LL. The CR rates at the end of cycle 1 were 41.7% for childhood T-cell ALL (P = .153), 60.0% for young adult T-cell ALL, and 30.0% for T-cell LL (Table 2). The CR rates by the end of cycle 2 were 50.0% for childhood T-cell ALL, 60.0% for young adult T-cell ALL, 51.7% for pooled T-cell ALL, and 40.0% for T-cell LL. The ORRs by the end of cycle 2 were 83.3% for childhood T-cell ALL, 80.0% for young adult T-cell ALL, and 82.8% for pooled T-cell ALL. The ORR for T-cell LL was 50.0%. Among patients with baseline extramedullary involvement, best overall responses (all disease areas) were CRi (n = 4/4) for childhood T-cell ALL, CRi (n = 1/2) and refractory (n = 1/2) for young adult T-cell ALL, and CR (n = 2/4) and progressive disease (n = 2/4) for T-cell LL.

In the all-treated analysis set, MRD negativity at any time during treatment was achieved in 11 (45.8%) children with T-cell ALL, 1 (20.0%) young adult with T-cell ALL, 12 (41.4%) pooled patients with T-cell ALL, and 5 (50.0%) patients with T-cell LL. Of note, in the T-cell LL cohort, bone marrow evaluation was only required if bone marrow disease was present at study entry; of the 5 patients in the T-cell LL cohort who had bone marrow involvement (≥5% bone marrow blasts) at baseline, 3 patients achieved MRD negativity during the study. MRD-negativity rates at the end of cycle 1, cycle 2, and after treatment are shown in Table 3.

In childhood T-cell ALL, 18 (75.0%) patients underwent allogeneic HSCT, as did 3 patients each with young adult T-cell ALL (60.0%) and T-cell LL (30.0%); median times to engraftment were 18.0, 26.0, and 20.0 days, respectively (Table 3). Two (11.1%) children with T-cell ALL failed to achieve initial hematopoietic reconstitution after HSCT: 1 patient received a cord blood transplant but subsequently died because of progressive disease, and the other received a second bone marrow transplant and was reported as still alive. Thus, reconstitution rates were 88.9% for childhood T-cell ALL and 100% for young adult T-cell ALL and T-cell LL. Of the 3 (12.5%) children with T-cell ALL who previously underwent HSCT, 1 patient received a second transplant and died shortly thereafter; 1 patient received a second transplant and is reported as still alive at the time of data cutoff; and 1 patient was refractory at the end of cycle 1, did not receive a second transplant, and later died because of an adverse event of worsened/altered general health status.

Median EFS was 8.9 months for childhood T-cell ALL, 10.3 months for young adult T-cell ALL, 9.5 months for pooled T-cell ALL, and 2.9 months for T-cell LL (Figure 1). Observed 24-month EFS rates were 36.1%, 20.0%, 33.4%, and 20.0% for childhood T-cell ALL, young adult T-cell ALL, pooled T-cell ALL, and T-cell LL, respectively.

EFS for the T-cell ALL/LL cohorts. Kaplan-Meier estimates of EFS, defined as the time from the date of first study drug administration to the first documented treatment failure, date of relapse from CR (ie, reappearance of leukemia blasts in the peripheral blood or >5% bone marrow blasts, reappearance of extramedullary disease, or new extramedullary disease), or death due to any cause, whichever occurs first. Median EFS for pooled children and young adults with T-cell ALL was 9.5 months (90% CI, 5.3-20.5). CI, confidence interval; NE, not evaluable.

EFS for the T-cell ALL/LL cohorts. Kaplan-Meier estimates of EFS, defined as the time from the date of first study drug administration to the first documented treatment failure, date of relapse from CR (ie, reappearance of leukemia blasts in the peripheral blood or >5% bone marrow blasts, reappearance of extramedullary disease, or new extramedullary disease), or death due to any cause, whichever occurs first. Median EFS for pooled children and young adults with T-cell ALL was 9.5 months (90% CI, 5.3-20.5). CI, confidence interval; NE, not evaluable.

Among patients who achieved CR during the study, median RFS was 19.4 months for childhood T-cell ALL, 9.4 months for young adult T-cell ALL, and 19.4 months for pooled T-cell ALL (supplemental Figure 5). For patients with T-cell LL, median RFS could not be evaluated. Observed 24-month RFS rates were 48.6%, 33.3%, 45.7%, and 50.0% for childhood T-cell ALL, young adult T-cell ALL, pooled T-cell ALL, and T-cell LL, respectively.

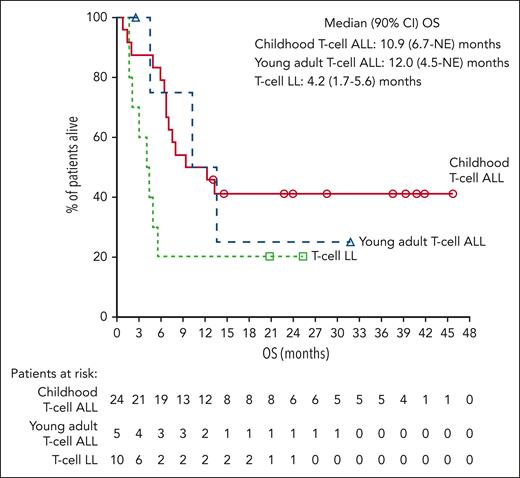

Median OS was 10.9 months for childhood T-cell ALL, 12.0 months for young adult T-cell ALL, 12.4 months for pooled T-cell ALL, and 4.2 months for T-cell LL (Figure 2). Observed 24-month OS rates were 41.3%, 25.0%, 38.9%, and 20.0% for childhood T-cell ALL, young adult T-cell ALL, pooled T-cell ALL, and T-cell LL, respectively.

OS for the T-cell ALL/LL cohorts. Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS, measured from the date of first study drug administration to the date of death due to any cause. Median OS for pooled children and young adults with T-cell ALL was 12.4 (90% CI, 7.0-NE) months. CI, confidence interval; NE, not evaluable.

OS for the T-cell ALL/LL cohorts. Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS, measured from the date of first study drug administration to the date of death due to any cause. Median OS for pooled children and young adults with T-cell ALL was 12.4 (90% CI, 7.0-NE) months. CI, confidence interval; NE, not evaluable.

Safety

The most common grade 3/4 TEAEs across cohorts were hematologic events (Table 4). Grade 3/4 infections were reported in 1 child with B-cell ALL (grade 4 sepsis), 12 (50.0%) children, and 2 (40.0%) young adults with T-cell ALL, and 3 (30.0%) patients with T-cell LL; no specific infection occurred in >2 patients across T-cell cohorts. Serious TEAEs were reported in 3 (42.9%) children with B-cell ALL (febrile neutropenia, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, and respiratory distress in 1 patient; febrile neutropenia in 1 patient; and febrile neutropenia, sepsis, and death in 1 patient), 16 (66.7%) children and 4 (80.0%) young adults with T-cell ALL, and 7 (70.0%) patients with T-cell LL; events in ≥2 patients in the T-cell cohorts included pyrexia, febrile neutropenia, septic shock, hyperbilirubinemia, neutropenia, diarrhea, stomatitis, and cellulitis. TEAEs led to daratumumab discontinuation in 1 child with T-cell ALL (brain edema/hepatic failure), 2 young adults with T-cell ALL (hyperbilirubinemia, neutropenia, septic shock, and thrombocytopenia in 1 patient; psychotic disorder in 1 patient), and 1 patient with T-cell LL (seizure); all events were considered unrelated to daratumumab. TEAEs led to death in 2 children with B-cell ALL (multiorgan dysfunction syndrome in 1 patient; unknown cause in 1 patient), 2 children with T-cell ALL (brain edema/hepatic failure due to backbone chemotherapy in 1 patient; worsened/altered general health status in 1 patient), and 1 patient with T-cell LL (pleural effusion); all were unrelated to daratumumab treatment.

After the first daratumumab infusion, IRRs were reported in 4 (57.1%) children with B-cell ALL, 16 (66.7%) children and 4 (80.0%) young adults with T-cell ALL, and 8 (80.0%) patients with T-cell LL. Three children with T-cell ALL had recurrent reactions with subsequent infusions. Most IRRs were grade 1/2 in severity; however, 1 child with T-cell ALL had grade 3 abdominal pain and 1 patient with T-cell LL had grade 3 bronchospasm. The most common IRR was cough (42.9%) in children with B-cell ALL; abdominal pain (20.7%), vomiting (13.8%), and pyrexia (13.8%) in patients with T-cell ALL; and cough (40.0%) and dyspnea (30.0%) in patients with T-cell LL.

PKs

PKs data for B-cell ALL are summarized in the supplemental Data. All patients with T-cell ALL/LL provided ≥1 postbaseline serum PK sample and are included in the daratumumab PKs analyses. In children with T-cell ALL, mean peak serum daratumumab concentrations were 263 (standard deviation [SD], 8.18) μg/mL on day 1 of cycle 1 EOI and increased ∼2.9-fold to 763 (SD, 185) μg/mL on day 22 of cycle 2 EOI, indicating accumulation after weekly daratumumab administration. Mean serum trough concentrations on days 1 and 22 of cycle 2 before dose were 324 (SD, 184) μg/mL and 369 (SD, 105) μg/mL, respectively. Similar results were obtained in the young adult T-cell ALL and T-cell LL cohorts (supplemental Figure 6).

All but 1 child with T-cell ALL provided a postbaseline CSF PK sample, for a CSF PK–evaluable population of 38 patients. Daratumumab CSF concentrations were similar in the childhood T-cell ALL and T-cell LL cohorts (supplemental Figure 7). Among young adults with T-cell ALL, lower daratumumab CSF concentrations were observed over time. Mean CSF concentrations in children with T-cell ALL were 0.907 (SD, 1.96) μg/mL on day 15 of cycle 1 before dose and 0.934 (SD, 0.549) μg/mL on day 15 of cycle 2 before dose.

Immunogenicity

None of the 36 evaluable patients tested positive for anti-daratumumab antibodies at any time during the study.

Discussion

Treatment options for relapsed/refractory T-cell ALL/LL are limited and provide limited survival improvement, with significant risks of adverse events. The phase 2 DELPHINUS study of daratumumab plus chemotherapy demonstrated activity in children and young adults with T-cell ALL/LL in first relapse. The ORR (CR + CRi) in the DELPHINUS pooled childhood/young adult T-cell ALL cohort (82.8%) compares favorably with response rates (CR + PR) of 55% in first-relapse T-cell ALL in the phase 2 study of single-agent nelarabine17 and 38% in relapsed/refractory T-cell ALL in the phase 1 NECTAR study of nelarabine plus etoposide/cyclophosphamide.18 The CR rate observed for the DELPHINUS pooled T-cell ALL cohort (51.7%) was lower than that reported in a phase 2 study in first-relapse childhood/young adult T-cell ALL receiving bortezomib plus chemotherapy (68%), although the rate of MRD negativity was 41.4% in DELPHINUS compared with 20% after 1 cycle of bortezomib plus chemotherapy.9 Although many factors play a role in successfully bridging to HSCT, in DELPHINUS, 75% of children and 60% of young adults with T-cell ALL successfully bridged to HSCT, with hematopoietic reconstitution rates of 89% and 100%, respectively. In comparison, the NECTAR study reported an HSCT rate of 53%18; other studies of alternate regimens, specifically among patients in second CR, reported rates of 26.6%,33 30.5%,4 and 88%.34 Given differences in outcome assessments/definitions, patient populations, and overall study conduct, caution should be taken when making cross-trial comparisons. For example, in DELPHINUS, the childhood T-cell ALL cohort had a median time >12 months from the end of prior systemic therapy to relapse/progression, whereas historically many patients relapse while still on treatment, and this relatively long time to prior relapse/progression may have influenced study outcomes for this cohort. Of note, time to relapse was not succinctly reported in the NECTAR study, the study of single-agent nelarabine, or the T-cell ALL cohort in the study of bortezomib with chemotherapy, thus making it difficult to compare our results directly with other data.

The safety profile of daratumumab in children and young adults with ALL/LL was consistent with that recorded in adults with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.35,36 No new safety signals for daratumumab were observed in the B-cell ALL or T-cell ALL/LL cohorts, including patients who were heavily pretreated, compared with the adult population. Additionally, IRRs were of low-grade severity and did not lead to daratumumab discontinuation, and no patient tested positive for anti-daratumumab antibodies during the study.

Analysis of serum daratumumab concentrations in the T-cell ALL/LL cohorts showed similar concentrations as those observed in adults with multiple myeloma, in which the target effective daratumumab trough concentration based on ORR was identified as 274 μg/mL.37 In children with T-cell ALL, mean daratumumab serum trough concentrations on days 1 and 22 of cycle 2 before dose were 324 μg/mL and 369 μg/mL, respectively, which were above the 99% model-predicted target saturation concentration of daratumumab (236 μg/mL).37 Similar daratumumab concentrations were observed in the other T-cell cohorts, suggesting daratumumab was sufficiently dosed in children and young adults. Furthermore, the substantially lower daratumumab concentrations in the CSF compared with serum indicate limited distribution of daratumumab into the CSF. Although monoclonal antibody distribution in the CSF (CSF/serum ratio) is generally reported to be >0.1% in animal models and patients,38 consistent with DELPHINUS, comparison data for daratumumab in the CSF do not exist.

In the small B-cell ALL cohort, daratumumab did not demonstrate efficacy, and this cohort was closed because of futility. Although all children with B-cell ALL expressed CD38 at baseline, levels were variable. Previous studies have shown that CD38 expression is low in B-cell disease and downregulated after induction therapy.19,20 Although CD38 expression on blasts declined over time with daratumumab, inferences regarding CD38 expression and its potential impact on efficacy cannot be made because of the small sample size of this cohort.

In conclusion, daratumumab can be safely combined with chemotherapy in children and young adults with relapsed/refractory T-cell ALL/LL and allowed a majority of patients to bridge to allogeneic HSCT, with successful posttransplant hematopoietic reconstitution in most patients. The clinical activity of daratumumab in combination with other agents or in patients with T-cell ALL/LL who are newly diagnosed or experience a first relapse requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in the study and their families, the coinvestigators, research nurses, and coordinators at each of the clinical sites, and the data and safety monitoring committee. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Michelle McDermott and Kimberly Brooks of Lumanity Communications Inc., and were funded by Janssen Global Services, LLC.

This study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03384654) was sponsored by Janssen Research & Development, LLC. The Leukemia and Lymphoma Society provided funding for correlative biology studies.

Authorship

Contribution: All authors participated in the conception and design of the study or in the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data, and confirm access to the primary clinical trial data; and participated in drafting and revising the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.B. and L.E.H. served on a steering committee for the design and monitoring of this study. D.T.T. received research funding from Beam Therapeutics and NeoImmune Tech; served on advisory boards for Beam Therapeutics, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Servier, and Sobi; and has multiple patents pending on CAR T-cells. F.B. served as a member of a data monitoring committee for a clinical trial sponsored by Sanofi; had a consultant/advisory role for Amgen, Bayer, EUSA Pharma, and Roche/Genentech; and received honoraria for speaking at symposia from Roche/Genentech and Servier (through current institution). P.V.P. received honoraria for speaking at a symposium from Servier. C.R. received honoraria for advisory roles and/or as a speaker from Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. F.L. served on advisory boards for Amgen, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, and Sobi and participated in speaker’s bureaus for Amgen and Gilead. A.B. served on advisory boards for, and received honoraria and/or travel support from, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Sanofi, Servier, and Wugen and received research funding from Shire/Servier. C.M.Z. received institutional research funding from Pfizer, AbbVie, Daiichi Sankyo, Gilead, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Kura Oncology, and Takeda; received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, Incyte, Kura Oncology, Novartis, and Syndax; and received consultant fees for this study. N.S.B. participated in a speaker’s bureau for Servier. A.R.-S.-S. served on advisory boards for EUSA Pharma and Sanofi and received expenses for congress attendance from EUSA Pharma and Roche. E.A.R. received institutional research funding from Pfizer and served on a data safety monitoring board for Bristol Myers Squibb. B.L.W. served as a consultant for Amgen and received institutional research funding from Amgen, Beam Therapeutics, BioSight, MacroGenics, Novartis, and Wugen. D.A.A. is a former employee of Janssen Research & Development, LLC. M.K., I.N., N.B., L.L.S., R.M.D., and R.C. are employees of Janssen Research & Development, LLC. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliations for B.L.W. is Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Children's Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; and Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

The current affiliation for D.A.A. is Translational Sciences, Incyte Corporation, Wilmington, DE.

Correspondence: Teena Bhatla, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of New Jersey, Newark Beth Israel Medical Center, 201 Lyons Ave, Newark, NJ 07112; email: teena.bhatla@rwjbh.org.

References

Author notes

T.B. and L.E.H. are joint first authors.

The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the DELPHINUS trial data (NCT03384654) can be submitted through the Yale Open Data Access project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.