Key Points

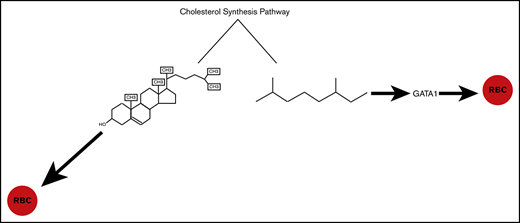

The products of the cholesterol synthesis pathway regulate RBC development during primitive erythropoiesis.

Isoprenoids regulate erythropoiesis by modulating the expression of the GATA1 transcription factor.

Abstract

Erythropoiesis is the process by which new red blood cells (RBCs) are formed and defects in this process can lead to anemia or thalassemia. The GATA1 transcription factor is an established mediator of RBC development. However, the upstream mechanisms that regulate the expression of GATA1 are not completely characterized. Cholesterol is 1 potential upstream mediator of GATA1 expression because previously published studies suggest that defects in cholesterol synthesis disrupt RBC differentiation. Here we characterize RBC development in a zebrafish harboring a single missense mutation in the hmgcs1 gene (Vu57 allele). hmgcs1 encodes the first enzyme in the cholesterol synthesis pathway and mutation of hmgcs1 inhibits cholesterol synthesis. We analyzed the number of RBCs in hmgcs1 mutants and their wild-type siblings. Mutation of hmgcs1 resulted in a decrease in the number of mature RBCs, which coincides with reduced gata1a expression. We combined these experiments with pharmacological inhibition and confirmed that cholesterol and isoprenoid synthesis are essential for RBC differentiation, but that gata1a expression is isoprenoid dependent. Collectively, our results reveal 2 novel upstream regulators of RBC development and suggest that appropriate cholesterol homeostasis is critical for primitive erythropoiesis.

Introduction

Erythropoiesis is the process of producing and replenishing the number of circulating red blood cells (RBCs). There are 2 unique waves of erythropoiesis: the primitive and the definitive. Erythropoiesis is tightly controlled and regulated by a balance of cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival.1,2 The overproduction of RBCs or lack of RBCs can cause human disease. Diamond-Blackfan anemia and sickle cell anemia are 2 examples of rare congenital anomalies that arise from defects in the production of RBCs,3 and polycythemia occurs as a consequence of too many RBCs.4-6 Genetic disorders of RBCs have revealed critical mediators of erythropoiesis,7-11 many of which include transcription factors. For example, Diamond-Blackfan anemia can result from mutations in the transcription factor GATA1.12-14 GATA1 is the founding member of the GATA family of zinc finger transcription factors15 that interacts with a multitude of other proteins such as Friend of GATA, EKLF, SP1, p300, and PU.1 to promote erythropoiesis.16

Cholesterol is 1 known regulator of RBC function because it maintains the structure and integrity of the RBC membrane and aids in the protection against oxidative stress.17-22 But both in vitro and in vivo studies have raised the possibility that cholesterol biosynthesis regulates the differentiation of RBCs.23,24 Knockdown of OSC/LSS, which catalyzes the cyclization of monoepoxysqualene to lanosterol, decreased the self-renewing capacity of K562 cells in vitro and caused increased cell death of progenitor like cells. Follow-up in vivo assays have reinforced this premise as reduced cholesterol synthesis was associated with deficits in terminal RBC development.24 These data provide strong evidence that cholesterol’s function in RBCs is not restricted to membrane fluidity.

The cholesterol synthesis pathway (CSP) begins with synthesis of HMG-CoA from aceto-acetyl-CoA, which then undergoes several transformations to produce farnesyl pyrophosphate. Farnesyl pyrophosphate represents a branch point in the pathway, ultimately resulting in the production of cholesterol or isoprenoids.25-27 Both classes of lipids have diverse functions spanning membrane fluidity, protein prenylation, and precursors to various different types of molecules including vitamin D3. Cholesterol homeostasis has been previously linked to hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) differentiation,28,29 and we confirmed that cholesterol synthesis is essential for RBC development.24 The function of isoprenoids is less clear because isoprenoids give rise to diverse molecules, which themselves are critical for cell differentiation.30-33

Here we show that the products of the CSP are essential for RBC development. We show that defects in cholesterol and/or isoprenoids results in deficient numbers of RBCs, but that each lipid regulates RBC development by unique mechanisms. We show that inhibition of isoprenoid synthesis disrupts the number of Gata1+ cells produced, but the inhibition of cholesterol has no effect on gata1 expression or the number of Gata1+ cells. Thus, we demonstrate an essential function for the CSP during RBC specification and primitive erythropoiesis.

Methods

Zebrafish care

For all experiments, embryos were obtained by crossing AB wild-type, Tupfel Long Fin wild-type, Tg(gata1a:dsRed)34 or hmgcs1Vu57.35 All embryos were maintained in embryo medium at 28°C and all experiments were performed according to protocol 811689-5 approved by The University of Texas El Paso Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Genotyping was performed as previously described.36

Drug treatments and morpholino injection

Atorvastatin (pharmaceutical grade; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), lonafarnib (Sigma), and Ro 48 8071 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were each dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Treatment was initiated at the sphere developmental stage (∼4-5 hours postfertilization [hpf]) and fresh drug was added every 18 to 24 hours until the harvest time points indicated in the figure legends. Drug concentrations were determined using a gradient of each drug (supplemental Figure 1) and the concentration selected was based on working conditions from previous literature. We selected a maximum tolerated sublethal dose producing a consistent phenotype according to a Fisher’s exact test as previously described in Quintana et al.36 Drugs were diluted in DMSO to make working solutions at the following concentrations: 2.0 μM atorvastatin,35-37 8 μM lonafarnib,35,38 and 1.5 μM Ro 48 8071. Final concentration of DMSO was <0.01% in all samples and vehicle control treatment. Ro 48 8071 specificity for oxido-squalene synthesis has been previously described.24,39,40 The specificity of lonafarnib has been previously described as a farnesyl protein transferase inhibitor.41 For morpholino injections, antisense hmgcs1 morpholinos (AATCATATAACGGTGTTGGTTCGTG) were injected (0.025 mM) at the single-cell stage and fixed at the indicated time points within the figure legend. For all treatment groups (drug treatment and morpholino) statistical significance was obtained using a Fisher’s exact test.

o-dianisidine staining

o-dianisidine (Sigma) staining was performed as previously described by Paffett-Lugassy and Zon.42 Briefly, embryos were harvested at the desired time point and stained in the dark for 15 minutes at room temperature with o-dianisidine (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA) (0.6 mg/mL), 0.01 M sodium acetate (Fisher, Waltham, MA), 0.65% H2O2 (Fisher), and 40% ethanol (Fisher). Stained embryos were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) for 1 hour at room temperature and bleached using 3% H2O2 and 2% potassium hydroxide (Fisher) for 12 minutes. Embryos were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and stored in 4°C. Embryos were imaged with Zeiss Discovery Stereo Microscope fitted with Zen Software.

Hemoglobin quantification

For hemoglobin quantification, larvae (numbers indicated in each figure) were homogenized with a pestle in purified water at 4 days postfertilization (dpf). Hemoglobin was measured with the Hemoglobin Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to manufacturer’s protocol. For analysis of the Vu57 allele, larvae were separated via distinct phenotypic hallmarks described previously.35,36 The control contained both homozygous wild-type and heterozygous individuals harboring the Vu57 allele. Experiments were performed in a minimum of biological duplicate. For drug treatment assays, wild-type embryos were treated as described before assaying for hemoglobin concentration. Statistical significance was determined using a Student t test.

Whole mount in situ hybridization and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Whole mount in situ hybridization was performed as described by Thisse and Thisse.43 Briefly, embryos were harvested and dechorionated at the indicated time point and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 1 hour at room temperature. Embryos were dehydrated using a methanol:PBS gradient and stored in 100% methanol overnight in −20°C. Embryos were rehydrated using PBS:methanol gradient, washed in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20, and permeabilized with proteinase K (10 μg/mL) for the time indicated by Thisse and Thisse.43 Permeabilized embryos were prehybridized in hybridization buffer (HB) (50% deionized formamide (Fisher), 5X SSC (Fisher), 0.1% Tween 20 (Fisher), 50 μg/mL heparin (Sigma), 500 μg/mL of RNase-free tRNA (Sigma), 1M citric acid (Fisher) (460 μL for 50 mL of HB) for 2 to 4 hours and then incubated overnight in fresh HB with probe (gata1a 75 ng, hbbe1.1 75 ng, alas2 150 ng) at 70°C. Samples were washed according to protocol, blocked in 2% sheep serum (Sigma), 2 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (Sigma) for 2 to 4 hours at room temperature, and incubated with anti-DIG Fab fragments (1:10 000) (Sigma) overnight at 4°C. Samples were developed with BM purple AP substrate (Sigma) and images were collected with a Zeiss Discovery Stereo Microscope fitted with Zen Software. Statistical analysis was performed using a Fisher’s exact test. For quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), RNA was isolated from embryos at the indicated time point using Trizol (Fisher) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription was performed using iScript (Bio-Rad, Redmond, WA) and total RNA was normalized across all samples. PCR was performed in technical triplicates for each sample using an Applied Biosystem’s StepOne Plus machine with Applied Biosystem’s software. Sybr green (Fisher) based primer pairs for each gene analyzed are as follows: gata1a fwd GTTTACGGCCCTTCTCCACA, gata1a rev CACATTCACGAGCCTCAGGT, hbbe1.1 fwd TGAATCCAGCACCCATCTGA, hbbe1.1 rev CTCCGAGAAGCTCCACGTAG, rpl13a fwd TCCCAGCTGCTCTCAAGATT, rpl13a rev TTCTTGGAATAGCGCAGCTT. Analysis performed using 2ΔΔct. Statistical analysis of messenger RNA (mRNA) expression was performed using a Student t test. All qPCR was performed in biological duplicate or triplicate.

Confocal imaging

Embryos were fixed at the given time point and then mounted in 0.6% low-melt agar in a glass bottom dish (Fisher). Imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM 700 at 20× magnification. Images were restricted to the caudal hematopoietic tissue. For each fish, a minimum of 12 to 20 z-stacks were collected. Statistical significance was obtained using a Student t test.

Results

Mutations in hmgcs1 disrupt RBC development

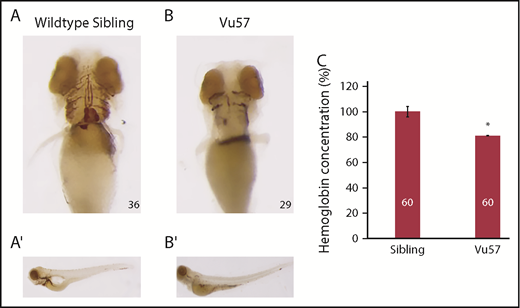

Based on previous data,24 we sought to determine the number of mature RBCs in a zebrafish harboring mutations in the hmgcs1 gene (Vu57). The Vu57 allele introduces a single missense mutation (H189Q) in the hmgcs1 gene, which encodes the first enzyme in the CSP. The Vu57 allele abrogates cholesterol synthesis, causing a multiple congenital anomaly syndrome characterized by defects in myelination, myelin gene expression, cardiac edema, pigment defects, and craniofacial abnormalities.35,36 We first detected the number of hemoglobinized RBCs in Vu57 homozygous mutants (hmgcs1−/−) or their wild-type siblings with o-dianisidine at 4 dpf. Over the first 4 days of development, all of the circulating RBCs are derived from primitive erythropoiesis; therefore, analysis of hemoglobinized RBCs at day 4 accurately depicts deficiencies in primitive erythropoiesis.44 Wild-type siblings had adequate numbers of hemoglobinized RBCs throughout development and, at 4 dpf, the RBCs lined the ventral head vessels of the neck and face (Figure 1A). Homozygous carriers of the Vu57 allele had a reduced number of cells populating the ventral head vessels with some detectable circulating RBCs near the base of the yolk sac in a select number of individuals (Figure 1A-B).

Mutations in hmgcs1 cause a decrease in hemoglobinized RBCs. (A-B) hmgcs1−/− (Vu57) and their wild-type siblings (hmgcs1+/+) were stained for hemoglobinized RBCs at 4 dpf (n = 36 hmgcs1+/+, n = 29 hmgcs1−/−) using o-dianisidine. Ventral views (A-B) of the hemoglobinized RBCs are shown with full body images (A′-B′) of both wild-type siblings and homozygous mutants (Vu57). The phenotype was completely penetrant in homozygous mutants. Total numbers of animals were obtained across a minimum 3 biological replicates. Images were taken with a 10× optical lens at 8× (A-B) and 6.3× (A′-B′) objective zoom. (C) The concentration of hemoglobin was measured in siblings (a pool of wild-type and heterozygous individuals) and embryos carrying the Vu57 allele. The assay was performed with 2 biological replicates with a total of 60 larvae. *P < .05.

Mutations in hmgcs1 cause a decrease in hemoglobinized RBCs. (A-B) hmgcs1−/− (Vu57) and their wild-type siblings (hmgcs1+/+) were stained for hemoglobinized RBCs at 4 dpf (n = 36 hmgcs1+/+, n = 29 hmgcs1−/−) using o-dianisidine. Ventral views (A-B) of the hemoglobinized RBCs are shown with full body images (A′-B′) of both wild-type siblings and homozygous mutants (Vu57). The phenotype was completely penetrant in homozygous mutants. Total numbers of animals were obtained across a minimum 3 biological replicates. Images were taken with a 10× optical lens at 8× (A-B) and 6.3× (A′-B′) objective zoom. (C) The concentration of hemoglobin was measured in siblings (a pool of wild-type and heterozygous individuals) and embryos carrying the Vu57 allele. The assay was performed with 2 biological replicates with a total of 60 larvae. *P < .05.

We next quantified the decrease in circulating RBCs in homozygous mutants and their siblings. We performed a quantitative measure of total hemoglobin content using a colorimetric assay in which endogenous hemoglobin can be measured quantitatively at a wavelength of 400 nm.45 To measure the levels of hemoglobin in siblings and Vu57 carriers, homozygous Vu57 larval were separated according phenotype at 3 dpf35 and the total hemoglobin content of homozygous carriers was compared with the hemoglobin content of wild-type and heterozygous siblings at 96 hpf. Phenotypic hallmarks of the Vu57 allele include craniofacial abnormalities and cardiac edema.35 As shown in Figure 1C, we detected a moderate, but consistent and statistically significant 20% decrease in total hemoglobin content (P < .05). Taken together, these data suggest that mutation of hmgcs1 disrupts RBC development.

Mutation of hmgcs1 disrupts the expression of markers associated with RBC differentiation

One possible explanation for the decrease in total hemoglobin content observed in larvae carrying the Vu57 allele could stem from an inability to produce globin mRNA. To determine whether mutations in hmgcs1 interfere with globin expression, we performed whole mount in situ hybridization (ISH) at 26 hpf with an anti-hbbe1.1 riboprobe. hbbe1.1 was expressed in the caudal intermediate cell mass (ICM) of wild-type siblings and the onset of circulation was readily apparent as hbbe1.1 mRNA was detected over the yolk sac (Figure 2A). hbbe1.1 expression was upregulated in Vu57 embryos with expression that localized throughout the entire ICM and was not restricted to the most caudal region (Figure 2B, arrowhead). In addition, hbbe1.1 expression over the yolk sac was increased relative to wild-type siblings at 26 hpf (Figure 2A-B).

hbbe1.1 and alas2 are expressed in hmgcs1 mutant larvae. Whole mount ISH was performed to detect the expression of hbbe1.1 (n = 41 hmgcs1+/+ [sibling], n = 34 hmgcs1−/− [Vu57]), (A-B) or alas2 (n = 16 hmgcs1+/+ [sibling], n = 15 hmgcs1−/− [Vu57]), (C-D) at 26 hpf. Purple, expression of each gene in the ICM; arrowhead, areas of increased or abnormal expression. Total number of animals was achieved with a minimum of 2 biological replicates. Images were taken with a 10× optical lens at 6.3× objective zoom.

hbbe1.1 and alas2 are expressed in hmgcs1 mutant larvae. Whole mount ISH was performed to detect the expression of hbbe1.1 (n = 41 hmgcs1+/+ [sibling], n = 34 hmgcs1−/− [Vu57]), (A-B) or alas2 (n = 16 hmgcs1+/+ [sibling], n = 15 hmgcs1−/− [Vu57]), (C-D) at 26 hpf. Purple, expression of each gene in the ICM; arrowhead, areas of increased or abnormal expression. Total number of animals was achieved with a minimum of 2 biological replicates. Images were taken with a 10× optical lens at 6.3× objective zoom.

We next measured the expression of alas2, which encodes the first enzyme in heme biosynthesis.46 Wild-type siblings expressed appropriate alas2 expression in the caudal ICM at 26 hpf (Figure 2C), but the level of alas2 in embryos with the Vu57 allele was spatially disrupted spanning the entire ICM (Figure 2D, arrowhead) and increased relative to wild-type siblings. These data are consistent with the level and spatial expression of hbbe1.1 because alas2 is known to modulate the levels of globin.47 We attempted to validate our collective expression analysis at 26 hpf by detecting hemoglobinized RBCs with o-dianisidine; however, we did not consistently or accurately detect hemoglobinized RBCs at 24-26 hpf (n = 20) in wild-type individuals (data not shown). These data are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that very few heme containing RBCs enter circulation before 30 hpf.48,49 However, our mRNA expression analysis demonstrates that mutant embryos maintain the expression of globin and some of the enzymes necessary for heme synthesis.

gata1a expression is decreased in hmgcs1 mutant embryos

Given the abnormal expression of globin (hbbe1.1), we hypothesized that the mutation of hmgcs1 disrupts the expression of GATA1, a known regulator of globin expression. We measured the expression of gata1a, the zebrafish ortholog of GATA1 using ISH and qPCR at 18 somites and 26 hpf in mutants and their wild-type siblings. At 18 somites, wild-type siblings expressed gata1a in the caudal ICM (Figure 3A, dorsal view), but the Vu57 allele resulted in decreased gata1a expression (Figure 3A-B, arrowheads). This decrease in gata1a persisted through the onset of circulation; we observed reduced gata1a expression at 26hpf (Figure 3C-D, arrowhead). We next quantified the expression of gata1a by qPCR. We quantified the expression of gata1a in embryos injected with an hmgcs1 morpholino because genotyping of mutant larvae before RNA isolation could not be consistently achieved without rapid decay in total RNA quality. Microinjection of hmgcs1 morpholinos accurately phenocopied the RBC deficits observed with the Vu57 allele (supplemental Figure 2) and QPCR confirmed a near 70% reduction in gata1a expression in morphants (Figure 3A-D,I, P < .05).

Mutation of hmgcs1 disrupts gata1a expression. (A-D) Whole mount ISH was performed to detect the expression of the gata1a transcription factor at the 18-somite stage (n = 18 hmgcs1+/+ [sibling], n = 13 hmgcs1−/− [Vu57]) and 26 hpf (n = 34 sibling, n = 28 Vu57). Total numbers of animals was obtained with a minimum of 2 biological replicates. (E-F) Embryos were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or 2 μM ATOR (n = 18 DMSO, n = 27 ATOR, P = .0001) from sphere stage to 26 hpf and subjected to ISH to detect gata1a expression. Numbers of embryos affected are indicated below each figure. P value represents Fisher’s exact test demonstrating the numbers affected per treatment group. Total numbers of embryos were obtained across 2 biological replicates. Arrowheads, area of gata1a expression at each time point. Images were taken with a 10× optical lens at 8× (A-B) and 6.3× (C-F) objective zoom. (G-H) Tg(gata1a:dsRed) embryos were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or 2 μM atorvastatin. Fluorescence was visualized using a confocal microscope at 20× magnification. The number of cells/Z-stack was quantified using ImageJ. (I) Antisense hmgcs1 morpholinos were injected (0.025 mM) at the single-cell stage and total RNA was extracted at the 18-somite stage. qPCR was performed to detect the expression of gata1a. All samples were performed in technical triplicate; error bars represent the standard deviation of technical triplicates. *P < .05. (J) Total RNA was isolated from embryos treated with vehicle control or ATOR and qPCR was performed to detect the expression of gata1a. All samples were performed in technical triplicate and error bars represent the standard deviation of technical triplicates. *P < .05. (K) Quantification of the number of dsRed cells from panels G and H. #P = 7.25273e-07.

Mutation of hmgcs1 disrupts gata1a expression. (A-D) Whole mount ISH was performed to detect the expression of the gata1a transcription factor at the 18-somite stage (n = 18 hmgcs1+/+ [sibling], n = 13 hmgcs1−/− [Vu57]) and 26 hpf (n = 34 sibling, n = 28 Vu57). Total numbers of animals was obtained with a minimum of 2 biological replicates. (E-F) Embryos were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or 2 μM ATOR (n = 18 DMSO, n = 27 ATOR, P = .0001) from sphere stage to 26 hpf and subjected to ISH to detect gata1a expression. Numbers of embryos affected are indicated below each figure. P value represents Fisher’s exact test demonstrating the numbers affected per treatment group. Total numbers of embryos were obtained across 2 biological replicates. Arrowheads, area of gata1a expression at each time point. Images were taken with a 10× optical lens at 8× (A-B) and 6.3× (C-F) objective zoom. (G-H) Tg(gata1a:dsRed) embryos were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or 2 μM atorvastatin. Fluorescence was visualized using a confocal microscope at 20× magnification. The number of cells/Z-stack was quantified using ImageJ. (I) Antisense hmgcs1 morpholinos were injected (0.025 mM) at the single-cell stage and total RNA was extracted at the 18-somite stage. qPCR was performed to detect the expression of gata1a. All samples were performed in technical triplicate; error bars represent the standard deviation of technical triplicates. *P < .05. (J) Total RNA was isolated from embryos treated with vehicle control or ATOR and qPCR was performed to detect the expression of gata1a. All samples were performed in technical triplicate and error bars represent the standard deviation of technical triplicates. *P < .05. (K) Quantification of the number of dsRed cells from panels G and H. #P = 7.25273e-07.

We next measured gata1a expression in wild-type embryos treated with 2 μM atorvastatin (ATOR), a drug that inhibits the rate-limiting step of the CSP,50 and should mimic the effects of mutations in hmgcs1. gata1a expression was decreased in ATOR-treated embryos relative to vehicle control (Figure 3E-F, arrowheads; P = .0001) and qPCR confirmed that ATOR treatment caused a significant reduction in gata1a expression (Figure 3J, P < .05). We next confirmed these results by treating Tg(gata1a:dsRed) larvae with 2 μM ATOR or vehicle control. Treatment with ATOR caused ∼50% decrease in the number of dsRed positive cells (Figure 3G-H,K, P = 7.25273e-07). Collectively, these data suggest that the Vu57 allele results in decreased numbers of Gata1a+ cells during primitive erythropoiesis.

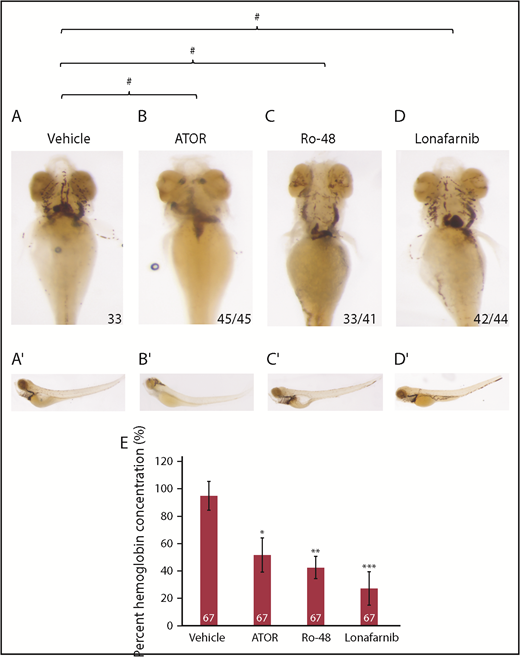

Cholesterol and isoprenoids regulate RBC development

Mutation of hmgcs1 disrupts the first enzyme of the CSP,35 effectively interfering with the production of both cholesterol and isoprenoids. Recent evidence suggests that each of these 2 lipids can regulate the same biological process, but by independent molecular and cellular mechanisms.35,36,38 We hypothesized that the defects observed in mutant larvae are cholesterol dependent. We treated wild-type embryos with either vehicle control (DMSO), 1.5 μM Ro 48 8071, to inhibit cholesterol, but not isoprenoids, and 8 μM lonafarnib, to inhibit farnesylated isoprenoids, but not cholesterol or 2 μM ATOR, a control to mimic the Vu57 allele. According to o-dianisidine, vehicle-treated embryos (DMSO) exhibited the appropriate number and spatial organization of RBCs in the ventral head vessels at 4 dpf (Figure 4A). Notably, treatment with ATOR induced a cerebral hemorrhage that was not consistent with the Vu57 allele (Figure 4B). Embryos treated with 1.5 μM Ro 48 8071 or 8 μM lonafarnib had visibly fewer RBCs (Figure 4A-D, P = .0001), suggesting that cholesterol synthesis is required for RBC development. Cerebral hemorrhages were not observed on treatment with Ro 48 8071 or lonafarnib. We further quantified the total hemoglobin content from larvae treated with each drug or vehicle control. As shown in Figure 4E, treatment with each drug resulted in a statistically significant decrease in total hemoglobin content. Drug treatment resulted in a more marked decrease in hemoglobin concentration relative to larvae harboring the Vu57 allele (Figure 1). This can likely be attributed to the fact that we performed a comparison between homozygous carriers of the Vu57 allele with a pool of heterozygous and wild-type homozygous individuals, suggesting that heterozygous individuals demonstrate some degree of deficits in RBC development. Taken together, these data raise the possibility that the synthesis of cholesterol and isoprenoids is essential for RBC development/differentiation.

Cholesterol and isoprenoids regulate erythropoiesis. (A-D) Embryos were treated at sphere stage with ATOR, Ro 48 8071 (Ro-48) to inhibit cholesterol, lonafarnib to inhibit isoprenoids, or vehicle control (DMSO). At 4 dpf, embryos (n = 33 DMSO, n = 45 ATOR, n = 41 Ro-48, and n = 44 lonafarnib) were stained with o-dianisidine to observe mature RBCs. (A′-D′) Full body images of stained larvae at 4 dpf. Images were taken with a 10× optical lens at 8× (A-D) and 6.3× (A′-D′) objective zoom. #P = .0001. P value indicates the number of affected embryos affected is statistically significant according to Fisher’s exact test. (E) The concentration of hemoglobin was measured in embryos treated with ATOR, Ro-48 to inhibit cholesterol, lonafarnib to inhibit isoprenoids, or vehicle control (DMSO) at 4 dpf. The number indicates total larvae analyzed across 3 biological replicates. *P = .000381218, **P = 2.20098e-05, ***P = 1.42e-05.

Cholesterol and isoprenoids regulate erythropoiesis. (A-D) Embryos were treated at sphere stage with ATOR, Ro 48 8071 (Ro-48) to inhibit cholesterol, lonafarnib to inhibit isoprenoids, or vehicle control (DMSO). At 4 dpf, embryos (n = 33 DMSO, n = 45 ATOR, n = 41 Ro-48, and n = 44 lonafarnib) were stained with o-dianisidine to observe mature RBCs. (A′-D′) Full body images of stained larvae at 4 dpf. Images were taken with a 10× optical lens at 8× (A-D) and 6.3× (A′-D′) objective zoom. #P = .0001. P value indicates the number of affected embryos affected is statistically significant according to Fisher’s exact test. (E) The concentration of hemoglobin was measured in embryos treated with ATOR, Ro-48 to inhibit cholesterol, lonafarnib to inhibit isoprenoids, or vehicle control (DMSO) at 4 dpf. The number indicates total larvae analyzed across 3 biological replicates. *P = .000381218, **P = 2.20098e-05, ***P = 1.42e-05.

gata1a expression is isoprenoid dependent

The Vu57 allele results in decreased gata1a expression and increased hbbe1.1 expression. Therefore, we measured the expression of each gene in wild-type embryos treated with vehicle control (DMSO), 1.5 μM Ro 48 8071, or 8 μM lonafarnib using ISH at 26 hpf. hbbe1.1 expression was localized to the caudal most region of the ICM and over the yolk sac in vehicle control embryos (Figure 5A). Inhibition of cholesterol or isoprenoids caused a statistically significant increase in hbbe1.1 mRNA (Figure 5G, P < .05) that was visible over the yolk sac (Figure 5A-C, P = .0001). The level and spatial expression of hbbe1.1 is consistent with those observed in embryos carrying the Vu57 allele (Figure 2). Interestingly, the expression of gata1a was not affected by treatment with 1.5 μM Ro 48 8071, but was significantly decreased when isoprenoid synthesis was inhibited (Figure 5D-F,H, P < .05). The decrease in gata1a expression was consistent with a decrease in the number of Gata1+ cells as demonstrated by the Tg(gata1a:dsRed) (Figure 5I, P = 2.7125e-07). Collectively, these data suggest that isoprenoids regulate RBC differentiation in a gata1a dependent manner.

Isoprenoids regulate RBC development in a gata1a-dependent manner. (A-F) Embryos were treated at sphere stage with Ro-48 to inhibit cholesterol, lonafarnib to inhibit isoprenoids, or vehicle control (DMSO). At 26 hpf, whole mount ISH was performed to detect hbbe1.1 (n = 45 DMSO, n = 53 Ro-48 [P = .0001], and n = 48 lonafarnib [P = .0001]) (A-C) or gata1a (D-F) expression (n = 45 DMSO, n = 39 Ro-48 [NS], and n = 51 lonafarnib; [P = .0001]). Total embryos were obtained with a minimum 3 biological replicates. Images were taken with a 10× optical lens at 6.3× objective zoom. P value designates statistical significance relative to vehicle control according to a Fisher’s exact test. Total RNA was isolated from embryos treated with vehicle control (DMSO), Ro-48, or lonafarnib; qPCR was performed to detect the expression of hbbe1.1 (G) or gata1a (H). All samples were performed in technical triplicate and error bars represent the standard deviation of technical triplicates. *P < .05. (I) Tg(gata1a:dsRed) embryos were treated at sphere stage with Ro-48 to inhibit cholesterol, lonafarnib to inhibit isoprenoids, or vehicle control (DMSO). Fluorescence was visualized using a confocal microscope. The number of cells/Z-stack was quantified using ImageJ. #P = 2.7125e-07.

Isoprenoids regulate RBC development in a gata1a-dependent manner. (A-F) Embryos were treated at sphere stage with Ro-48 to inhibit cholesterol, lonafarnib to inhibit isoprenoids, or vehicle control (DMSO). At 26 hpf, whole mount ISH was performed to detect hbbe1.1 (n = 45 DMSO, n = 53 Ro-48 [P = .0001], and n = 48 lonafarnib [P = .0001]) (A-C) or gata1a (D-F) expression (n = 45 DMSO, n = 39 Ro-48 [NS], and n = 51 lonafarnib; [P = .0001]). Total embryos were obtained with a minimum 3 biological replicates. Images were taken with a 10× optical lens at 6.3× objective zoom. P value designates statistical significance relative to vehicle control according to a Fisher’s exact test. Total RNA was isolated from embryos treated with vehicle control (DMSO), Ro-48, or lonafarnib; qPCR was performed to detect the expression of hbbe1.1 (G) or gata1a (H). All samples were performed in technical triplicate and error bars represent the standard deviation of technical triplicates. *P < .05. (I) Tg(gata1a:dsRed) embryos were treated at sphere stage with Ro-48 to inhibit cholesterol, lonafarnib to inhibit isoprenoids, or vehicle control (DMSO). Fluorescence was visualized using a confocal microscope. The number of cells/Z-stack was quantified using ImageJ. #P = 2.7125e-07.

Discussion

Here we show that cholesterol and isoprenoids regulate erythropoiesis using a zebrafish harboring mutations in the hmgcs1 gene (Vu57 allele). Mutations in human HMGCS1 have not been associated with disease, but there are 8 congenital anomalies that occur as a consequence of mutations within other enzymes of the CSP.5-11,13,51 These congenital anomalies are characterized by diverse phenotypes,7,21,51-53 and mutations in the zebrafish hmgcs1 gene mimic these disorders, resulting in a multiple congenital anomaly syndrome. Therefore, zebrafish with mutations in hmgcs1 have the potential to reveal novel cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying individual phenotypes across multiple genetic disorders.

Cholesterol represents approximately one-half the weight of an RBC membrane and governs membrane fluidity, transport, reversible deformations, and survival in response to oxidative stress.54,55 In addition, cholesterol is a precursor for multiple molecules including bile acid, vitamin D, and steroid hormones. Moreover, deficiencies in cholesterol synthesis interfere with proper RBC development.23,24 Based on these data, we hypothesized that mutation of hmgcs1 would disrupt erythropoiesis in vivo. We found that homozygous mutation of hmgcs1 causes a decrease in the number of hemoglobinized RBCs and total hemoglobin content, consistent with previous work,24 demonstrating that defects in RBC number can be rescued by the exogenous injection of water-soluble cholesterol. Our study using the Vu57 allele establishes that the products of the CSP are essential for proper RBC homeostasis; however, the mechanisms by which the CSP exerts these effects is yet to be elucidated. Given the role of cholesterol in the RBC membrane, it is plausible that cholesterol regulates cell survival. However, the function of the CSP might not be limited to cell death or stress mechanisms because previously published work has indicated a regulatory function for cholesterol and its derivatives at the level of cellular differentiation.56-63 Future work that analyzes both primitive and definitive hematopoiesis at unique stages of differentiation in different model systems is likely to identify the exact cellular mechanisms underlying the phenotypic alteration we describe. The closely related zebrafish mutant of hmgcrb will be of great utility because we hypothesize that mutation of hmgcrb37 will produce overlapping phenotypes with the Vu57 allele.

The GATA family of transcription factors are essential mediators of erythropoiesis. Specifically, the expression of GATA1 signals the commitment of a common myeloid progenitor toward an erythroid fate. Numerous studies have confirmed that the expression of GATA1 is at the center of at least 2 axis-governing cell fate decisions. The expression of GATA1 represses the expression of GATA2, a second member of the family whose expression promotes a progenitor cell fate.15,64 GATA1 expression also antagonizes the expression of SPI-1, which promotes myeloid differentiation.65,66 Here we demonstrate for the first time that the expression of gata1a, the zebrafish ortholog of GATA1, is linked to the CSP. Moreover, we establish that expression of gata1a is isoprenoid dependent. These data are supported by previously published studies by Quintana et al, which demonstrate that defects in cholesterol synthesis disrupt RBC differentiation without disrupting early gata1a expression.24 Despite reduced expression of gata1a in hmgcs1 mutants, differentiating RBCs maintain their ability to initiate and maintain globin and alas2 expression. The inhibition of the CSP did not cause the excessive accumulation of mature RBCs to other bodily regions except for in the presence of atorvastatin treatment, where cerebral hemorrhages are observed. This phenotype is not consistently observed with the Vu57 allele or larvae treated with lonafarnib or Ro 48 8071, but has been reported in hmgcrb mutants.37 Despite the presence of cerebral hemorrhages in atorvastatin-treated embryos, we still observe a statistically significant decrease in total hemoglobin content in these larvae. Thus, suggesting that inhibition of the CSP reduces total hemoglobin content, which is consistent with an accumulation of globin and alas2 RNA. These results are further supported by in vitro studies of GATA1 deletion where GATA1 negative cells undergo developmental arrest, but maintain expression of GATA target genes, including globin.67

Our data establish that isoprenoid synthesis is essential for appropriate gata1a expression. These effects are likely to be indirect because isoprenoids are a large class of molecules with diverse functions. Retinoids are an isoprenoid derivative68 and retinoic acid is 1 potential regulator of blood cell differentiation because previous studies have established that retinoic acid signaling increases the number of HSCs30,31,33 and mediates the formation of HSCs from the mesoderm.69 However, these mechanisms are likely to be complex and stage specific because retinoic acid has been shown to decrease the expression of gata1 in zebrafish.70 Thus, retinoic acid is only 1 potential mediator of erythropoiesis.

Here we demonstrate that cholesterol and isoprenoids, 2 products of the CSP modulate RBC differentiation in vivo. The cholesterol independent mechanisms disrupt gata1a expression and the number of Gata1a+ cells produced. This is notable as GATA1 regulates at least 2 axis-regulating lineage fate decisions, but it is not clear if there are hematopoietic defects before onset of gata1a expression. The presence of cerebral hemorrhages in atorvastatin-treated embryos may shed some light on this question because HSCs and endothelial cell progenitors both arise from a common bipotent progenitor during primitive hematopoiesis.71,72 Thus, defects in both lineages could indicate early defects in the formation or differentiation of cells from mesoderm. Future studies that define the mechanisms by which cholesterol and isoprenoids regulate all stages of differentiation, including early HSCs and myeloid cells, are warranted.

Our study focuses on the regulation of GATA1 expression, primarily in the context of isoprenoids. Given the role of isoprenoids in development and signaling, it is likely that they are positive upstream regulators of gata1a. Therefore, future work in this area may identify novel therapeutic targets for various disorders. For example, mutation of mevalonate kinase causes mevalonate kinase deficiency.73,74 Mevalonate kinase is central to the CSP and converts mevalonate to 5′phosphomevalonate, which is the substrate for future enzymatic reactions that culminate with the creation of cholesterol and isoprenoids and therefore mutations in this kinase disrupt the synthesis of both cholesterol and isoprenoids. Patients with mevalonate kinase deficiency exhibit hematological deficiencies and extramedullary hematopoiesis,75 but the mechanisms underlying these phenotypes are not fully characterized. However, mutations in mevalonate kinase are likely to be recapitulated in zebrafish with mutations in hmgcs1 or hmgcrb. Therefore, our system has the potential to understand the mechanisms governing GATA1 expression, a central transcriptional regulator of primitive hematopoiesis.

For access to datasets and protocols, please contact the corresponding author by e-mail.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The hmgcs1Vu57 allele was kindly provided by Bruce Appel from the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. The Tg(gata1a:dsRed) fish were provided by Leonard Zon from Harvard Medical School.

These studies were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (2G12MD007592) to the University of Texas El Paso; National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of General Medical Sciences (RL5GM118969, TL4GM118971, R25GM069621-11, and UL1GM118970) to the University of Texas El Paso; and National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (1K01NS099153-01A1) (A.M.Q.).

Authorship

Contribution: J.A.H. and A.M.Q. synthesized the hypothesis, performed in situ hybridization, genotyping, data analysis, statistical analysis, cell counts, wrote the manuscript, and performed study design; J.A.H. and V.L.C. performed quantitative polymerase chain reaction; A.M.Q. and V.L.C. performed morpholino injections and hemoglobin quantification in drug treatment assays; V.L.C. performed o-dianisidine staining, imaged, and contributed to data analysis; N.R.-N. and J.A.H. performed genotyping and imaging; and J.A.H. and L.P.M. performed hemoglobin quantification in fish harboring the Vu57 allele.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Anita M. Quintana, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Texas El Paso, 500 W University Ave, Biosciences Building, Room 5.150, El Paso, TX 79968; e-mail: aquintana8@utep.edu.

References

Author notes

J.A.H. and V.L.C. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 2. hbbe1.1 and alas2 are expressed in hmgcs1 mutant larvae. Whole mount ISH was performed to detect the expression of hbbe1.1 (n = 41 hmgcs1+/+ [sibling], n = 34 hmgcs1−/− [Vu57]), (A-B) or alas2 (n = 16 hmgcs1+/+ [sibling], n = 15 hmgcs1−/− [Vu57]), (C-D) at 26 hpf. Purple, expression of each gene in the ICM; arrowhead, areas of increased or abnormal expression. Total number of animals was achieved with a minimum of 2 biological replicates. Images were taken with a 10× optical lens at 6.3× objective zoom.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/3/8/10.1182_bloodadvances.2018024539/2/m_advances024539f2.png?Expires=1765922359&Signature=3b1nSxCAgqI5Ej3RRO8s1hEq4y~lmhwPkUqDV1tQNdq6Q0VOC2We3X40s~9sfmnd9KoCn6LyOCbFB~u6bVxknQ4dNz8JyAfyClCHVDmHUGuVdtOOvFAr6mVHGTjVKA7xsigPIGryzcsm5Y8Qnh4kaixcm8Jk37GeJWVWu5KSGDU2p~4BH0nksmFF9NJ2pVgPR5u0wnd2pilUq1nXWWvhlrGmtTb08r7KWIwuzyshDt0PGvvB-vgVuOCcp6LT0fx5ESGcCLhldEbeNj-JvKjuLbm14NGz6gYPDz0WvT72XUDxFgLoZDTq7AGVPWAXH~aAcEetsUKgw9nMbLx5joohBw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. Mutation of hmgcs1 disrupts gata1a expression. (A-D) Whole mount ISH was performed to detect the expression of the gata1a transcription factor at the 18-somite stage (n = 18 hmgcs1+/+ [sibling], n = 13 hmgcs1−/− [Vu57]) and 26 hpf (n = 34 sibling, n = 28 Vu57). Total numbers of animals was obtained with a minimum of 2 biological replicates. (E-F) Embryos were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or 2 μM ATOR (n = 18 DMSO, n = 27 ATOR, P = .0001) from sphere stage to 26 hpf and subjected to ISH to detect gata1a expression. Numbers of embryos affected are indicated below each figure. P value represents Fisher’s exact test demonstrating the numbers affected per treatment group. Total numbers of embryos were obtained across 2 biological replicates. Arrowheads, area of gata1a expression at each time point. Images were taken with a 10× optical lens at 8× (A-B) and 6.3× (C-F) objective zoom. (G-H) Tg(gata1a:dsRed) embryos were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or 2 μM atorvastatin. Fluorescence was visualized using a confocal microscope at 20× magnification. The number of cells/Z-stack was quantified using ImageJ. (I) Antisense hmgcs1 morpholinos were injected (0.025 mM) at the single-cell stage and total RNA was extracted at the 18-somite stage. qPCR was performed to detect the expression of gata1a. All samples were performed in technical triplicate; error bars represent the standard deviation of technical triplicates. *P < .05. (J) Total RNA was isolated from embryos treated with vehicle control or ATOR and qPCR was performed to detect the expression of gata1a. All samples were performed in technical triplicate and error bars represent the standard deviation of technical triplicates. *P < .05. (K) Quantification of the number of dsRed cells from panels G and H. #P = 7.25273e-07.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/3/8/10.1182_bloodadvances.2018024539/2/m_advances024539f3.png?Expires=1765922359&Signature=bB63DUKjXqCysHnx4yKPv4~d~j4GPSkezDG6~RDkM6Q5nRqBzqQu6vo9PyCVtYmlAya4HRyGJHycE23sMGaFNEjIdPQtLpUd9~A7AbRAfibTjbWc3gqYl0E1qlv4aleiTNqk8Ctm2k0jIWY8FR6DM4UsNABqg3cPxdN07Cg2SDZtvxJPHTD6tFxiu0f8YxNODMT8WAXN3d5Yxs6YNUIeIZFkR0vOmtamwQFRmDF9QrP8Yj9S8WeocIP5Nq04pgUEdLlrlX5Tvc3Xqu3AgSVeO-E01KpxczbBWPdGyHKvJ3eRaGffklz2hZ2Ttm1lTkupRKIByk3dodtU7x08UNE5Gg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 5. Isoprenoids regulate RBC development in a gata1a-dependent manner. (A-F) Embryos were treated at sphere stage with Ro-48 to inhibit cholesterol, lonafarnib to inhibit isoprenoids, or vehicle control (DMSO). At 26 hpf, whole mount ISH was performed to detect hbbe1.1 (n = 45 DMSO, n = 53 Ro-48 [P = .0001], and n = 48 lonafarnib [P = .0001]) (A-C) or gata1a (D-F) expression (n = 45 DMSO, n = 39 Ro-48 [NS], and n = 51 lonafarnib; [P = .0001]). Total embryos were obtained with a minimum 3 biological replicates. Images were taken with a 10× optical lens at 6.3× objective zoom. P value designates statistical significance relative to vehicle control according to a Fisher’s exact test. Total RNA was isolated from embryos treated with vehicle control (DMSO), Ro-48, or lonafarnib; qPCR was performed to detect the expression of hbbe1.1 (G) or gata1a (H). All samples were performed in technical triplicate and error bars represent the standard deviation of technical triplicates. *P < .05. (I) Tg(gata1a:dsRed) embryos were treated at sphere stage with Ro-48 to inhibit cholesterol, lonafarnib to inhibit isoprenoids, or vehicle control (DMSO). Fluorescence was visualized using a confocal microscope. The number of cells/Z-stack was quantified using ImageJ. #P = 2.7125e-07.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/3/8/10.1182_bloodadvances.2018024539/2/m_advances024539f5.png?Expires=1765922359&Signature=0gI566JTDHYEfigmppSZmS6uv5IWXHuWxIDlggIYjidUq4rVdri1qalUVIz48Mfr6rSrClik9FA~kKhGmQ6EeZ96G6WC-QKe2HrY6Eu7oTXqgABeXUtZEIXq2upgls22epqBJnLfYMmjA7KADprBVKLFwvg1wI9i-vJW1aMfIZBEbU62ko8~NZMfXhZvz-iL27SAYTnp3RGIiLBRBEMzr8DqVf55MECQ5VbKoPTEdCH38d6GErZTg0h4iHMrgSiX~ZvnsE92pj4ZVcQOeSYWdfJlHEZs1FHwDVAyD3cOQdPM4AHFx5zxMhz4H8-EV--TXLzcRO0~ow5FjhPQrXNk7w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)