Key Points

DWJM expands UCB CD34+ cells while preserving their differentiation potential.

DWJM induces CXCR4 expression molecularly and phenotypically in UCB CD34+ cells and enhances their transmigration capability.

Abstract

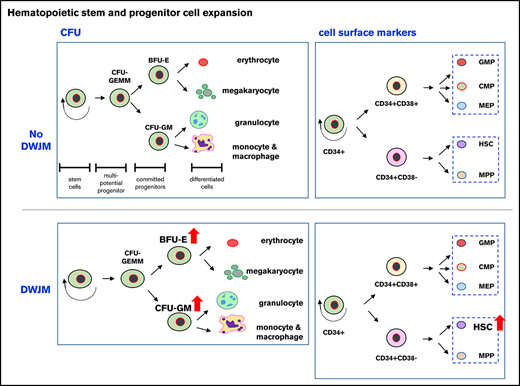

Hematopoietic stem progenitor cells (HSPCs) reside in the bone marrow (BM) hematopoietic “niche,” a special 3-dimensional (3D) microenvironment that regulates HSPC self-renewal and multipotency. In this study, we evaluated a novel 3D in vitro culture system that uses components of the BM hematopoietic niche to expand umbilical cord blood (UCB) CD34+ cells. We developed this model using decellularized Wharton jelly matrix (DWJM) as an extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffold and human BM mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) as supporting niche cells. To assess the efficacy of this model in expanding CD34+ cells, we analyzed UCB CD34+ cells, following culture in DWJM, for proliferation, viability, self-renewal, multilineage differentiation, and transmigration capability. We found that DWJM significantly expanded UCB HSPC subset. It promoted UCB CD34+ cell quiescence, while maintaining their viability, differentiation potential with megakaryocytic differentiation bias, and clonogenic capacity. DWJM induced an increase in the frequency of c-kit+ cells, a population with enhanced self-renewal ability, and in CXCR4 expression in CD34+ cells, which enhanced their transmigration capability. The presence of BM MSCs in DWJM, however, impaired UCB CD34+ cell transmigration and suppressed CXCR4 expression. Transcriptome analysis indicated that DWJM upregulates a set of genes that are specifically involved in megakaryocytic differentiation, cell mobility, and BM homing. Collectively, our results indicate that the DWJM-based 3D culture system is a novel in vitro model that supports the proliferation of UCB CD34+ cells with enhanced transmigration potential, while maintaining their differentiation potential. Our findings shed light on the interplay between DWJM and BM MSCs in supporting the ex vivo culture of human UCB CD34+ cells for use in clinical transplantation.

Introduction

In hematopoietic cell transplantation, transplanted donor hematopoietic stem progenitor cells (HSPCs) home to the bone marrow (BM) and lodge in the BM hematopoietic “niche” to initiate donor-derived hematopoiesis or engraftment, which is key for the success of hematopoietic cell transplantation in the treatment of hematologic malignancies. HSPCs derived from umbilical cord blood (UCB), compared with BM HSPCs, are advantageous because they are associated with a low rate of graft-versus-host disease, despite HLA disparity; however, they show impaired BM homing and engraftment1 and have a low number of CD34+ cells given the limited volume of cord blood units. These biological characteristics explain the prolonged time after UCB-based clinical transplantation to achieve neutrophil recovery2 and unacceptable delays in platelet recovery.3,4 Although expanding UCB CD34+ cells might overcome 1 hurdle, expanding UCB CD34+ cells while simultaneously enhancing their transmigration and BM homing, and megakaryocytic differentiation, could potentially overcome some drawbacks to more efficient UCB transplantation.

Extensive research is being invested in developing in vitro culture systems to support HSPC expansion that mimic the BM microenvironment,5-14 because HSPCs’ self-renewal and multipotency are regulated by its interaction with this special microenvironment, called the BM hematopoietic “niche.” The main components of this niche are the cells surrounding HSPCs, including mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), osteoblasts, and endothelial cells. Other important components of the BM niche are multiple extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (collagens, fibronectin, tenascins), along with cytokines and growth factors that bind or diffuse into ECM.15 These BM niche components not only control the size of the HSPC pool but also regulate HSPC fate during normal homeostasis and conditions of stress.16 Several types of 3-dimensional (3D) scaffolds have been explored for HSPCs in ex vivo culture, including porous matrix, nanofiber meshes, and woven and nonwoven fabrics.17-20 Others have used collagen-coated substrates to mimic the 3D soft marrow, and these have been shown to change the shape, spread, and phenotype of HSPCs.20,21 These models lack the complexity of BM ECM, which is composed of a variety of proteins, glycosaminoglycans, and the biophysical properties of BM microenvironment, including viscosity and ECM composition. All of these factors might impact the self-renewal and multipotency of HSPCs.15

The goal of this study was to overcome the limitations of currently available in vitro models5-10 for CD34+ cell expansion by developing a 3D culture system that provides some of the BM hematopoietic niche components. We used decellularized Wharton jelly matrix (DWJM) from the umbilical cord, which shares many components of the BM ECM, including collagens I, III, VI, and XII, fibronectin, tenascin-C, and hyaluronic acid,22 to create a natural 3D ECM scaffold for our in vitro culture system. This 3D ECM-based scaffold was evaluated using UCB CD34+ cells, with the aim of expanding multipotent UCB CD34+ cells with enhanced transmigration and megakaryocytic differentiation capabilities, the biologic characteristics of the UCB CD34+ cells needed to assure their successful transplantation.

Methods

Enrichment of UCB CD34+ cells

Fresh UCB units were processed for UCB CD34+ cell enrichment as previously described.23

BM MSC isolation and expansion

Human BM MSCs were isolated from BM aspirates collected from healthy donors at the University of Kansas Medical Center (Human Subjects Committee #5929), as described in the supplemental Data.

Processing and preparation of DWJM

Details of the decellularization procedure and preparing DWJM wafers, which are thin pieces of DWJM with uniform thickness (3 mm), were previously described.22,24 Before experiments, DWJM wafer stock was fast thawed at 37°C and washed 3 times by sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 300g/6 minutes centrifugation in between. In some preparations, matrix viscosity affected cell survival; accordingly, we evaluated matrix viscosity prior to cell culture. Briefly, DWJM wafers were rinsed in RPMI 1640 solution and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. After 1 hour, wafers and media were transferred to a 100-μm strainer, and flow through was collected. Viscosity measurement occurred at room temperature by a modified Zahn cup measure. Wafers were released for use when wafers had a value of 3 Zahn cup-seconds or less.

In vitro BM mimetic model

Enriched CD34+ cells were cultured as suspension cells in cytokines (control). As adherent cells, UCB CD34+ cells were cocultured with BM stromal cells, forming a monolayer in 24-well plates (Corning Life Sciences, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), or with DWJM alone, or with DWJM preseeded with BM MSCs. Before seeding cells into DWJM, DWJM wafers were washed in PBS 3 times and incubated in culture medium overnight. For coculture, BM MSCs were seeded into culture wells alone as monolayers or into DWJM wafers 2 days before adding CD34+ cells. After enrichment, 3 × 104 CD34+ cells were seeded (i) in suspension without MSCs, (ii) on a monolayer of MSCs, (iii) in cell-free DWJM wafers, and (iv) in DWJM wafers with preseeded MSCs (Figure 1C). Cells were cultured in StemSpan media supplemented with 1:100 CC110 (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). CC110 contains recombinant human fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand, Flt-3 ligand, Stem cell factor 1, and thrombopoietin for 7 days at 37°C with 5% CO2. The initial media volume for each well was 2 mL, and half the media was changed every other day by carefully pipetting 1 mL out and replacing it with fresh media. To collect DWJM-adherent cells, DWJM wafers with adherent CD34+ UCB cells were digested by 1 mg/mL collagenase II for 3 hours at 37°C under 5% CO2, followed by 3 PBS washes for collagenase removal.

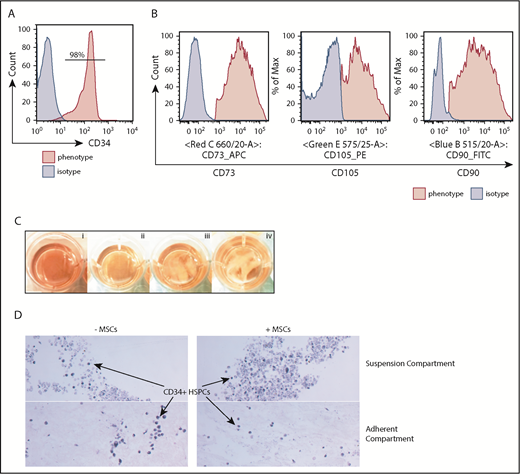

Characterization of the hematopoietic niche components. (A) All UCB units were enriched for CD34+ cells for this study with >90% purity. (B) Enriched BM MSCs were CD73+CD105+CD90+. (C) UCB CD34+ cells were cultured in suspension (i; control), BM MSC monolayer (ii), DWJM (iii), and DWJM preseeded with BM MSCs (iv). (D) Histology hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of the 2 compartments (Suspension vs Adherent) of 3D DWJM-based culture systems (original magnification ×20). Hematopoietic cells were identified in DWJM (left) and DWJM preseeded with BM MSCs (right), respectively, after 7-day culture in StemSpan with stem cell-supporting cytokines.

Characterization of the hematopoietic niche components. (A) All UCB units were enriched for CD34+ cells for this study with >90% purity. (B) Enriched BM MSCs were CD73+CD105+CD90+. (C) UCB CD34+ cells were cultured in suspension (i; control), BM MSC monolayer (ii), DWJM (iii), and DWJM preseeded with BM MSCs (iv). (D) Histology hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of the 2 compartments (Suspension vs Adherent) of 3D DWJM-based culture systems (original magnification ×20). Hematopoietic cells were identified in DWJM (left) and DWJM preseeded with BM MSCs (right), respectively, after 7-day culture in StemSpan with stem cell-supporting cytokines.

Proliferation assays

Trypan blue exclusion assay was used to assess total cell proliferation. In addition, cell division was monitored using the CellTrace proliferation kit (Invitrogen). After enrichment, CD34+ cells were labeled according to manufacturer’s instructions, and cell proliferation was measured by flow cytometry. A CD34–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) antibody (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) was used for costaining to label CD34+ cells before flow cytometry analysis. Data were analyzed by FlowJo software (Version 7.5; Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) apoptosis assay

UCB CD34+ cells were stained with annexin V–FITC, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit II; BD Pharmingen). Details are described in the supplemental Data.

Flow cytometry analyses

Enriched UCB CD34+ cells were cultured for 7 days under different culture conditions, and the phenotypes of expanded cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells were washed with staining buffer twice (PBS + 2% fetal bovine serum), resuspended, and stained for 10 minutes at 4°C with the following: CD34-FITC (Miltenyi), CD38-APC (Miltenyi), CXCR4-PE–Vio770 (Miltenyi), c-kit–APC-Cy7 (Miltenyi), CD41-FITC (Stemcell Technologies), CD71-VioBlue (Miltenyi), CD33-PE (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), CD3-FITC (Stemcell Technologies), CD19-APC (BD Pharmingen), and CD56–PE-Cy7 (BD Pharmingen). For further refinement in assessing the hematopoietic lineage after expansion, we performed 10-color flow cytometry analysis on expanded UCB CD34+ cells in the absence or presence of DWJM following the lineage definitions and gating strategies described by Notta et al.25 The 10-color antibody cocktail was composed of anti-CD7, -CD10, -CD34, -CD38, -CD71, -CD135 (FLT3), -CD45RA, -CD49f, -CD110, and -Thy1/CD90 antibodies (all antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences [San Jose, CA], except for anti-CD110 and anti-CD90 antibodies, which were purchased from BioLegend). We followed the lineage and ontogeny gating strategies by Notta et al25,26 for flow data analyses. After staining, cells were analyzed by LSR II (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed by FlowJo software.

Colony-forming unit (CFU) assay

The clonogenic ability of cells cultured in different conditions, after 7-day culture, was measured by CFU assay, as detailed in the supplemental Data. Briefly, after UCB CD34+ cells were cultured in the presence or absence of DWJM and/or BM MSC, 300 live cells as determined by Trypan blue exclusion were cultured in MethoCult H4034 Optimum media (Stemcell Technologies). After 12 days, types of CFU were determined by colony morphologies. Four independent experiments were performed, and 6 wells per treatment group were enumerated for CFU.

Transwell assay for transmigration activity

Transwell assay was used to evaluate chemotactic responses of the cells to stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1), as detailed in the supplemental Data.

RNAseq library preparation, sequencing, and analysis

UCB CD34+ cells cultured for 1 week in DWJM or in suspension (n = 2, 2 separate cord blood units) were isolated and submitted for RNAseq experiments and analysis, as detailed in the supplemental Data.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (quantitative PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cell lysates using the RNAeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the instructions by the manufacturer and as detailed in the supplemental Data. TaqMan Master mix (Applied Biosystems) was used with the following primers (ThermoFisher): CD41 (Hs0116228_m1IIGA2B), CXCL8 (Hs00174103_m1IL8), CXCR4 (Hs00237052_m1CXCR4), Gata2 (Hs00231119_m1GATA2), and VWR (Hs01109446_m1VWF) primers. Data analysis was performed using QuantStudio 12K Flex software. No amplification was detected in control samples where complementary DNA template was omitted (no template control).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Comparisons between different culture conditions were analyzed using Student t test. When samples from the same UCB unit were cultured in different conditions, the paired sample Student t test was used to compare conditions. In this paired setting, if >2 conditions were being compared, a linear mixed model was used to compare conditions while accounting for correlation in the data coming from the same UCB unit. Data were log2 transformed when necessary. For all analyses, P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc).

Results

UCB CD34+ cells cultured with DWJM demonstrated decreased proliferation

All experiments used CD34+ cells with a purity >90% (Figure 1A) and well-characterized BM MSCs (CD73+CD105+CD90+; Figure 1B). We set up 4 culture conditions to test DWJM effects on the proliferation and differentiation of CD34+ cells (Figure 1C): (i) no DWJM (control), (ii) BM MSC monolayer, (iii) DWJM, and (iv) DWJM preseeded with BM MSCs. DWJM-adherent and DWJM–nonadherent cells could be distinguished easily by their cellular localization (Figure 1D; supplemental Figures 1 and 2) and were collected for assays after 7 days in culture.

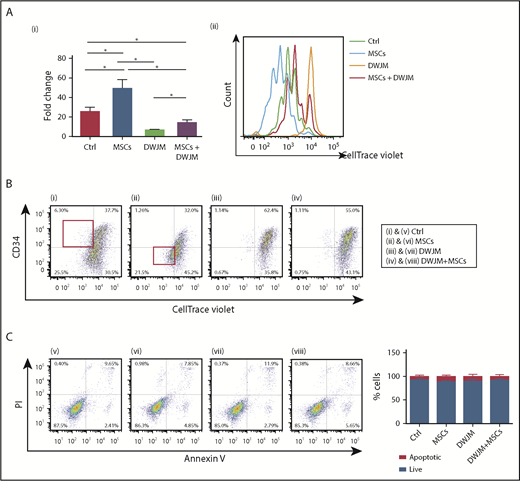

First, we determined the effects of DWJM and MSCs on UCB CD34+ cell proliferation. The total cell numbers increased 26-fold after CD34+ cells were cultured in the absence of DWJM and MSCs (Figure 2Ai control). CD34+ cells proliferated more (50-fold increase) in the presence of MSCs (Figure 2Ai second column), but were significantly suppressed by DWJM (7 times fold increase vs control 26-fold increase) (Figure 2Ai third column). Intriguingly, DWJM preseeded with MSCs enhanced CD34+ cell proliferation, compared with DWJM alone (Figure 2Ai fourth column).

DWJM decreases the proliferation rate and maintains primitive phenotypes of CD34+cells. (Ai) The percentage of cells surviving using Trypan blue exclusion assay in 4 cell culture conditions after 7-day culture. (Aii) Quantification of cell proliferation rate by CellTrace Violet intensity assay. UCB CD34+ cells cultured under 4 conditions were collected and labeled with CellTrace Violet. Cell proliferation rate was accessed by flow cytometry after labeling. (B) Double staining of CellTrace Violet and CD34 in 4 culture conditions. (C) Quantification of apoptosis and necrosis of hematopoietic cells on 4 culture conditions by AnnexinV/PI staining. Results, shown as density plots (left), are quantified in bar graphs (right). Data shown are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3 from 3 independent studies, *P < .1. Ctrl, control.

DWJM decreases the proliferation rate and maintains primitive phenotypes of CD34+cells. (Ai) The percentage of cells surviving using Trypan blue exclusion assay in 4 cell culture conditions after 7-day culture. (Aii) Quantification of cell proliferation rate by CellTrace Violet intensity assay. UCB CD34+ cells cultured under 4 conditions were collected and labeled with CellTrace Violet. Cell proliferation rate was accessed by flow cytometry after labeling. (B) Double staining of CellTrace Violet and CD34 in 4 culture conditions. (C) Quantification of apoptosis and necrosis of hematopoietic cells on 4 culture conditions by AnnexinV/PI staining. Results, shown as density plots (left), are quantified in bar graphs (right). Data shown are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3 from 3 independent studies, *P < .1. Ctrl, control.

Next, we examined the proliferation rate of CD34+ cells under these culture conditions after 7-day expansion, using the CellTrace assay. Results (Figure 2Aii) were consistent with the total cell proliferation (Figure 2Ai): CD34+ cells cultured over MSC monolayer had the highest fold change in cell numbers (Figure 2Ai), which also resulted insignificant loss of violet signal, indicating higher proliferation rate (Figure 2Aii cyan line). Cells undergoing 4 to 6 cell divisions were increased compared with cells in the other culture conditions. In contrast, CD34+ cells cultured in DWJM alone showed the least proliferation (Figure 2Aii orange line). Compared with UCB CD34+ cells cultured in DWJM alone, those cultured in DWJM preseeded with MSCs showed increased cell proliferation, because there were some cells undergoing 1 to 3 cell divisions. However, DWJM preseeded with MSCs maintained a population of CD34+ cells with high violet signal (Figure 2Aii red line). Collectively, our results indicated that DWJM maintains UCB CD34+ cells in a comparatively quiescent state (Figure 2Ai third column; Figure 2Aii orange peak), compared with other culture conditions.

We further determined the effects of DWJM and MSCs on CD34+ cell differentiation by tracing the cell surface expression of CD34, a phenotypic marker of primitive HSPCs, as they proliferated (Figure 2B). Fast-proliferating and slow-proliferating cells were easily distinguished, based on the violet fluorescence intensity on CellTrace Violet–labeled cells. The MSC monolayer culture condition gave rise to the lowest percentage of CD34+ CellTrace Violet+ double-positive cells (Figure 2Bii), 32% vs 37%, 62%, and 55% in the other culture conditions. Under the MSC monolayer culture condition, fast-proliferating cells were CD34− (Figure 2Bii gated cells within the red rectangle in the left bottom quadrant), which contrasted with the fast proliferating CD34+ cell population under the control condition (Figure 2Bi gated cells within the red rectangular in the left top quadrant). In contrast, the fast proliferation cell population was rarely detected while DWJM was present in the culture, regardless of the presence of MSCs (Figure 2Biii-iv). As shown in Figure 2Biii, the highest percentage (62.4%) of CD34+ cells with violet fluorescence was detected in DWJM alone, compared with 55% of CD34+ cells cultured in MSC preseeded DWJM (Figure 2Biv). Collectively, these data suggested that DWJM not only inhibits the proliferation of CD34+ cells but also maintains their quiescence when CD34 expression is used as a marker for HSPCs’ primitive state.

DWJM effectively maintains the viability of UCB CD34+ cells

Given that DWJM was associated with a decreased proliferation rate of CD34+ cells (Figure 2A-B), we further examined whether DWJM induces apoptosis and thus reduces the viability of CD34+ cells. We used Annexin V/PI staining to identify apoptotic cells, while in parallel tracing cell proliferation by CellTrace Violet (Figure 2C). The rates of apoptosis were comparable among the 4 culture conditions (Figure 2Cv-viii), with a survival rate ranging from 80% to 95% as summarized by the bar graph of Figure 2C.

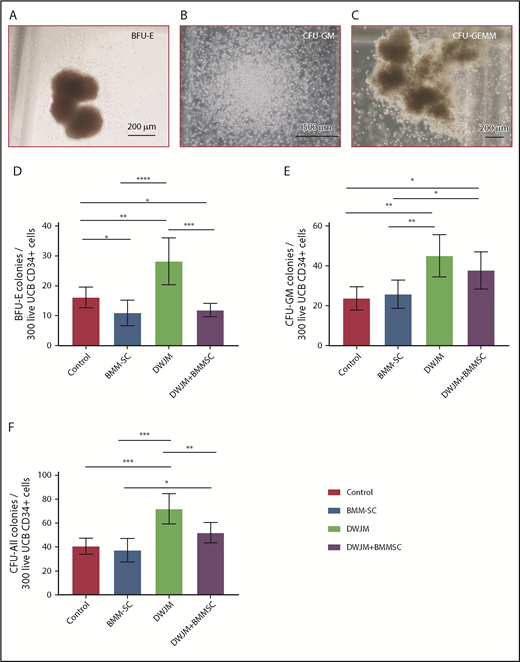

DWJM enhances the colony-forming capability of UCB CD34+ cells

Given that UCB HSPCs are multipotent and capable of differentiating into hematopoietic cell lineages with diverse biological functions,27 we examined the colony-forming cell potential of UCB CD34+ cells under our 4 culture conditions using hematopoietic CFU assays (Figure 3A-C).28 The absolute numbers of burst-forming unit–erythroid (BFU-E), CFU–granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM), and CFU, all derived from 300 live CD34+ cells after 7 days in vitro culture, are summarized in Figure 3D-F. UCB CD34+ cells cultured in DWJM showed the highest colony-forming potential of BFU-E, CFU-GM, and total CFU (in Figure 3D-F third columns with P < .0001, P < .01, and P < .01, respectively), suggesting that DWJM enhanced the overall differentiation potential of UCB CD34+ cells and maintained their multipotency. Intriguingly, when UCB CD34+ cells were cultured in the presence of DWJM and MSCs (Figure 3E-F last columns), more CFU-GM than BFU-E colonies were generated, suggesting that if both DWJM and MSCs were present in culture, HSPC differentiation was biased toward granulocyte and monocyte/macrophage, rather than erythrocyte, differentiation.

DWJM enhances colony-formation capability of CD34+cells. (A-C) Formation of BFU-E (A), CFU-GM (B), and CFU–granulocyte, erythroid, macrophage, megakaryocyte (CFU-GEMM) (C) from CD34+ cells after 14-day culture. (D-F) Numbers of BFU-E (D), CFU-GM (E), and total colonies (F) per 100 seeded live cells on 4 culture conditions, control, MSCs, DWJM, and DWJM/MSCs. (G-I) numbers of BFU-E, CFU-GM, and total CFU, respectively, derived from 300 live CD34+ cells. Six wells were calculated from 3 independent studies (n = 3). Two-tailed Student t tests were used to analyze significance between groups. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001, ****P ≤ .0001.

DWJM enhances colony-formation capability of CD34+cells. (A-C) Formation of BFU-E (A), CFU-GM (B), and CFU–granulocyte, erythroid, macrophage, megakaryocyte (CFU-GEMM) (C) from CD34+ cells after 14-day culture. (D-F) Numbers of BFU-E (D), CFU-GM (E), and total colonies (F) per 100 seeded live cells on 4 culture conditions, control, MSCs, DWJM, and DWJM/MSCs. (G-I) numbers of BFU-E, CFU-GM, and total CFU, respectively, derived from 300 live CD34+ cells. Six wells were calculated from 3 independent studies (n = 3). Two-tailed Student t tests were used to analyze significance between groups. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001, ****P ≤ .0001.

DWJM biases CD34+ cells preferentially toward megakaryocytic differentiation

Given that UCB HSPCs cultured in DWJM demonstrated enhanced differentiation potential into both the myeloid and the erythroid lineages (Figure 3E-F), we further examined if DWJM and MSCs induced CD34+ cells to express markers of lineage commitment and differentiation. Cells derived from 6 culture conditions (we analyzed the suspension compartments separately from the adherent population in DWJM-based culture conditions) (Figure 4A-B) were examined by 6 cell lineage–specific markers: CD33 for myeloid differentiation and long-term repopulating stem cells,29 CD41 for megakaryocyte differentiation, CD71 for erythroid differentiation, CD56 for nature killer cell differentiation, CD3 for T-cell differentiation, and CD19 for B-cell differentiation (CD19+).

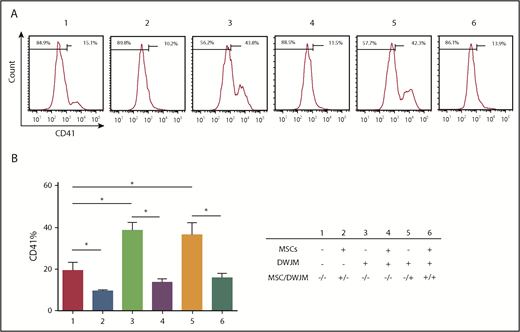

DWJM biases CD34+cell differentiation toward the megakaryocyte lineage. (A) The frequencies of CD41+ cells after 7-day culture under 6 culture conditions were determined by flow cytometry. (B) Summary of the CD41+ cell frequency (n = 3, data are expressed as mean ± SEM, *P < .1).

DWJM biases CD34+cell differentiation toward the megakaryocyte lineage. (A) The frequencies of CD41+ cells after 7-day culture under 6 culture conditions were determined by flow cytometry. (B) Summary of the CD41+ cell frequency (n = 3, data are expressed as mean ± SEM, *P < .1).

Among the 6 lineage markers, the CD41 marker showed significant variability between the 6 culture conditions (Figure 4A-B; supplemental Figure 3). When compared with cells in the control condition (Figure 4A #1), the frequencies of CD41+ cells were increased when CD34+ cells were cultured in DWJM in the absence of MSCs (Figure 4A #3 and #5). In contrast, the presence of MSCs thoroughly inhibited CD41 expression on CD34+ cells, regardless of the presence of DWJM (Figure 4A #2, 4, and 6), suggesting that the effects of MSCs on CD41 expression of CD34+ cells overrides the effects of DWJM. The capability of DWJM to drive CD34+ cells toward megakaryocyte differentiation was later confirmed at the molecular level by RNAseq (supplemental Figure 4A-B).

DWJM preserves the primitive phenotype of UCB CD34+ cells

Increased CD41 expression on CD34+ cells (Figure 4) raised the possibility that DWJM induces HSPCs to differentiate and thus lose their “stemness” (ie, primitive phenotype), a major drawback for an ex vivo method to culture HSPCs.30 We therefore examined if the undifferentiated phenotype of HSPCs is preserved by DWJM. We selected CD38 (Figure 5A) and c-Kit (Figure 5B) as 2 surrogates to evaluate HSPC’s primitive phenotype under these culture conditions, because CD38 expression on UCB CD34+ cells has been shown to be an indicator of lineage commitment and loss of stemness,31 and c-Kit expression has been used to determine the purity of UCB HSPCs.32 C-kit expression is also used to determine engraftment capability33 and megakaryocytic differentiation potential of UCB HSPCs.30

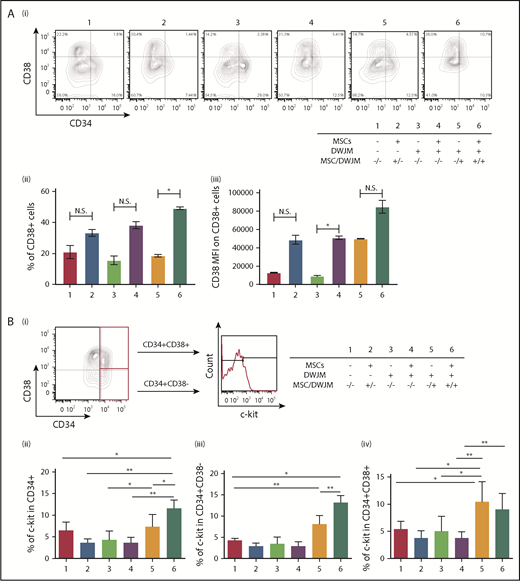

DWJM maintains the CD34+CD38−phenotype and increases c-Kit expression of CD34+cells. (Ai) Expression of CD38 on CD34+ cells after 7-day culture under 6 culture conditions. (ii) Frequency of CD38+ cells. (iii) CD38 MFI on gated CD38+ cells. (B) c-Kit expression in CD34+ cells under 6 conditions. HPSCs were stained with 1 antibody composed of CD34, CD38, and c-Kit. (i) Gating strategy. Percentages of c-Kit+ cells were analyzed in CD34+CD38+ (top) and CD34+CD38− (bottom) cell subsets. (ii) Summary of c-Kit+ percentages in CD34+, (iii) CD34+CD38−, and (iv) CD34+CD38+ cell subsets under 6 conditions for 7 days (data from 3 independent studies, expressed as mean ± SEM, *P < .05, **P < .01). N.S., not significant.

DWJM maintains the CD34+CD38−phenotype and increases c-Kit expression of CD34+cells. (Ai) Expression of CD38 on CD34+ cells after 7-day culture under 6 culture conditions. (ii) Frequency of CD38+ cells. (iii) CD38 MFI on gated CD38+ cells. (B) c-Kit expression in CD34+ cells under 6 conditions. HPSCs were stained with 1 antibody composed of CD34, CD38, and c-Kit. (i) Gating strategy. Percentages of c-Kit+ cells were analyzed in CD34+CD38+ (top) and CD34+CD38− (bottom) cell subsets. (ii) Summary of c-Kit+ percentages in CD34+, (iii) CD34+CD38−, and (iv) CD34+CD38+ cell subsets under 6 conditions for 7 days (data from 3 independent studies, expressed as mean ± SEM, *P < .05, **P < .01). N.S., not significant.

CD38 expression.

Overall, the presence of MSCs in CD34+ cell culture caused a nonsignificant increase in the percentage of CD38+ expressing cells within the CD34+ cell population (Figure 5Ai-ii #2, #4, and #6), except in the presence of DWJM (culture condition #6 vs condition #5) (Figure 5Aii), suggesting that MSCs enhanced CD38 expression in the presence of DWJM. In addition to cell frequency, we also examined the cell surface expression level of CD38 by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) (Figure 5Aiii). Although DWJM caused a nonsignificant decrease the CD38+ cell frequency (Figure 5Aii #3 vs #4), it significantly reduced the level of CD38 cell surface expression (Figure 5Aiii #3 vs #4). These results suggest that on CD34+ cells, MSCs increase the frequency and expression intensity of CD38, whereas DWJM suppresses CD38 expression.

c-Kit expression.

After 7 days in ex vivo culture, CD34+ cells in 6 culture conditions were divided into 2 cell subsets, CD34+CD38+ and CD34+CD38−, and these were analyzed for c-Kit expression by flow cytometry (Figure 5Bi). As shown in Figure 5Bii, the percentage of c-Kit+ cells in the CD34+ cell subset increased in the presence of adherence to DWJM in the presence of MSCs (Figure 5Bii #6 vs #1). An increased c-Kit+ expression in the CD34+CD38− cell subsets was also detected in the adherent cell population in the presence of DWJM (Figure 5Bii-iii #5 and #6), whereas an increased c-Kit+ frequency in the CD34+CD38+ cell population was only observed in the DWJM adherent population (in Figure 5Biv #5 vs #1). These results suggest that adherence to DWJM is important in upregulating c-kit expression in both the CD34+CD38− and CD34+CD38+ cell subsets, whereas the additional presence of MSCs supports c-kit expression in the CD34+CD38− subset.

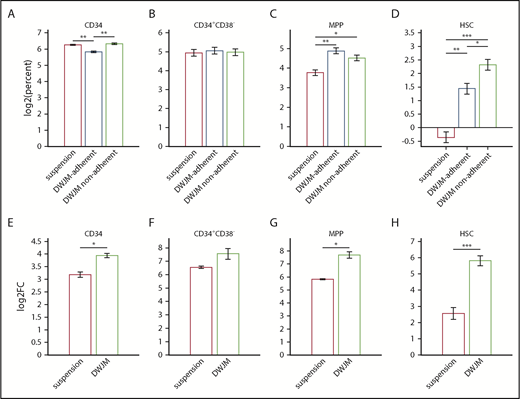

DWJM affects UCB CD34+ cell subset in vitro

DWJM changed not only the percentages of CD34+CD38+ cells (Figure 5Aii) but also the expression level of CD38 (Figure 5Aiii). To further identify DWJM effects on the expansion of the specific hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) and multipotent progenitor (MPP) subsets, we analyzed CD34+ cell subsets by flow cytometry as defined by Notta et al.25 We evaluated the percentage of CD34+ cell subsets according to suspension, DWJM-adherent, and DWJM-nonadherent populations after 7 days of culture (supplemental Figure 5 flow plots show our gating strategy for identifying MPP and HSC populations in baseline [A], as well as in suspension [B], DWJM-adherent [C], and DWJM-nonadherent [D] populations after 7-day culture). The percentage of CD34+ cells was significantly lower in DWJM-adherent conditions compared with both DWJM-nonadherent and to suspension conditions (Figure 6A). We did not see significant differences in the percentage of the CD34+CD38− cell subset (Figure 6B). On the other hand, the percentage of the MPP and HSC subsets was significantly higher in DWJM-adherent and nonadherent conditions compared with suspension (Figure 6C-D). Interestingly, the percentage of the MPP subset was higher in the DWJM-adherent population, whereas the percentage of the HSC subset was higher in the DWJM-nonadherent conditions (Figure 6C-D). Also, we evaluated the fold change between suspension and DWJM culture conditions by combining the adherent and nonadherent populations (Figure 6E-H). In summary, DWJM culture conditions resulted in significantly higher fold change in CD34+ cells and the MPP and HSC subsets (Figure 6E,G-H). There was no significant change in CD34+CD38− between the 2 culture conditions (Figure 6F). Collectively, these data confirm that DWJM-based culture conditions specifically support the expansion of the HSC population.

Effects of DWJM on UCB CD34+-derived cell subsets. In these experiments, enriched UCB CD34+ cells 3 × 104 were seeded onto DWJM or cultured in suspension for 7 days. Cells adherent to DWJM were isolated using collagenase treatment as described previously. The DWJM adherent and nonadherent populations were analyzed separately by flow cytometry. The total number of cells after culture was measured using automated cell counter. The absolute number of a specific population was measured by multiplying the total cell number of the specific condition with the percentage of the specific population in the parent population as determined by flow. Data were log2 transformed. (A) Percentage of live CD34+ cells on day 7 in suspension, DWJM-adherent, and nonadherent populations. (B) Percentage of live CD34+CD38− cells on day 7 in suspension, DWJM-adherent, and nonadherent populations. (C) Percentage of live MMP cells on day 7 in suspension, DWJM-adherent, and nonadherent populations. (D) Percentage of live HSCs on day 7 in suspension, DWJM-adherent, and nonadherent populations. (E) Fold change in CD34+ cells in suspension vs DWJM culture conditions. (F) Fold change in CD34+CD38− cells in suspension vs DWJM culture conditions. (G) Fold change in MPP cells in suspension vs DWJM culture conditions. (H) Fold change in HSCs in suspension vs DWJM culture conditions. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001.

Effects of DWJM on UCB CD34+-derived cell subsets. In these experiments, enriched UCB CD34+ cells 3 × 104 were seeded onto DWJM or cultured in suspension for 7 days. Cells adherent to DWJM were isolated using collagenase treatment as described previously. The DWJM adherent and nonadherent populations were analyzed separately by flow cytometry. The total number of cells after culture was measured using automated cell counter. The absolute number of a specific population was measured by multiplying the total cell number of the specific condition with the percentage of the specific population in the parent population as determined by flow. Data were log2 transformed. (A) Percentage of live CD34+ cells on day 7 in suspension, DWJM-adherent, and nonadherent populations. (B) Percentage of live CD34+CD38− cells on day 7 in suspension, DWJM-adherent, and nonadherent populations. (C) Percentage of live MMP cells on day 7 in suspension, DWJM-adherent, and nonadherent populations. (D) Percentage of live HSCs on day 7 in suspension, DWJM-adherent, and nonadherent populations. (E) Fold change in CD34+ cells in suspension vs DWJM culture conditions. (F) Fold change in CD34+CD38− cells in suspension vs DWJM culture conditions. (G) Fold change in MPP cells in suspension vs DWJM culture conditions. (H) Fold change in HSCs in suspension vs DWJM culture conditions. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001.

DWJM enhances CXCR4-dependent migration of UCB CD34+ cells

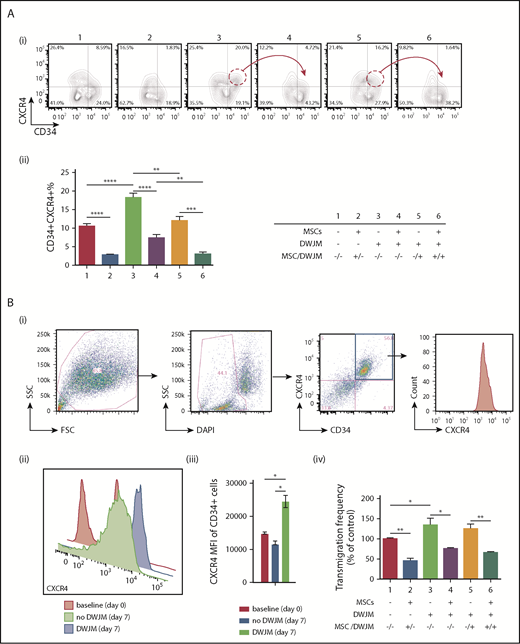

BM homing of HSPC is regulated by SDF-1 expressed in the BM niche, and CXCR4 expressed on HSPC.34 To determine the potential role of DWJM in improving BM homing of CD34+ cells, we examined the effects of DWJM on CXCR4 expression and on the transmigration capability of CD34+ cells, using flow analysis and transwell assay, respectively. In the absence of MSCs, the percentages of CD34+CXCR4+ cells were significantly increased by culturing with DWJM (20.0% ± 2.2% for #3 and 16.2% ± 2.8% for #5, Figure 7Ai), when compared with the control (8.6% ± 1.8% for #1, Figure 7Ai). In contrast, in the presence of MSCs in culture, the frequency of CD34+CXCR4+ cells were considerably reduced (1.8% ± 0.2% for #2; 4.7 ± 1.6 for #4, and 1.6 ± 0.4 for #6, Figure 7Ai-ii). An obvious reduction in the CD34+CXCR4+ cell populations was detected when MSCs were the only variant between cultures that included DWJM (Figure 7Ai red circles and arrows #3 vs #4 and #5 vs #6). Collectively, our results suggest that CXCR4 expression on UCB CD34+ cells was enhanced by DWJM, but suppressed in the presence of BM MSCs (Figure 8A).

DWJM increases CXCR4 cell surface expression and enhances CD34+cell transmigration. (Ai) Contour plots of CD34 and CXCR4 expression on CD34+ cells. (Aii) Percentage of CD34+CXCR4+ cells from 3 independent experiments (n = 3, data are expressed as mean ± SEM, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001). (Bi) Gating strategy: debris exclusion → dead cell exclusion → MFI analysis of CXCR4 expression on gated CD34+ cells. (Bii) CXCR4 expression on gated CD34+CD34+ cells at baseline (red, day 0), culture without DWJM (green, day 7), and culture with DWJM (purple, day 7). (Biii) Summary of CXCR4 expression on CD34+ cells. (Biv) Transwell assay (n = 3, data are expressed as mean ± SEM, *P < .05, **P < .01). DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FSC, forward scatter; SCC, side scatter.

DWJM increases CXCR4 cell surface expression and enhances CD34+cell transmigration. (Ai) Contour plots of CD34 and CXCR4 expression on CD34+ cells. (Aii) Percentage of CD34+CXCR4+ cells from 3 independent experiments (n = 3, data are expressed as mean ± SEM, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001). (Bi) Gating strategy: debris exclusion → dead cell exclusion → MFI analysis of CXCR4 expression on gated CD34+ cells. (Bii) CXCR4 expression on gated CD34+CD34+ cells at baseline (red, day 0), culture without DWJM (green, day 7), and culture with DWJM (purple, day 7). (Biii) Summary of CXCR4 expression on CD34+ cells. (Biv) Transwell assay (n = 3, data are expressed as mean ± SEM, *P < .05, **P < .01). DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FSC, forward scatter; SCC, side scatter.

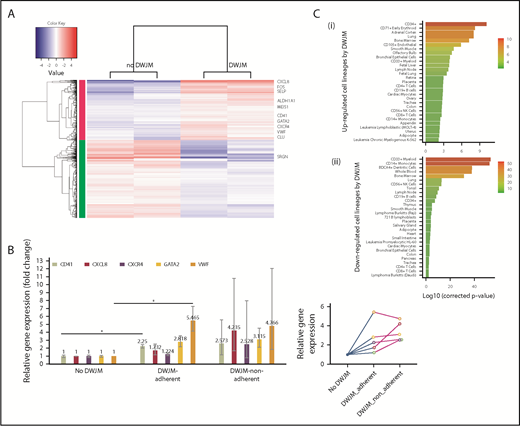

DWJM affects gene expression profile of UCB-derived CD34+cells. (A) RNAseq analysis. Heat map showing significantly up- and downregulated genes in UCB CD34+ cells cultured in DWJM or in suspension (control). (B) qPCR verification of 5 genes (CD41, CXCL8, CXCR4, GATA2, VWF) that were identified by RNAseq. (C) Genes influenced by DWJM. (i) Upregulated genes by DWJM. (ii) Downregulated genes by DWJM. CD34+ cells cultured in the absence of DWJM served as the baseline. *Statistically significant. NK, natural killer.

DWJM affects gene expression profile of UCB-derived CD34+cells. (A) RNAseq analysis. Heat map showing significantly up- and downregulated genes in UCB CD34+ cells cultured in DWJM or in suspension (control). (B) qPCR verification of 5 genes (CD41, CXCL8, CXCR4, GATA2, VWF) that were identified by RNAseq. (C) Genes influenced by DWJM. (i) Upregulated genes by DWJM. (ii) Downregulated genes by DWJM. CD34+ cells cultured in the absence of DWJM served as the baseline. *Statistically significant. NK, natural killer.

To determine whether DWJM also enhanced CXCR4 cell surface expression intensity as well as the frequency of CXCR4+ cells (Figure 7A), we examined CXCR4 expression on CD34+CXCR4+ cells, using flow cytometry (Figure 7Bi). CD34+ cells cultured in DWJM showed a statistically significant increase in CXCR4 cell surface expression, measured by MFI, when compared with the baseline and 7-day culture in the absence of DWJM (Figure 7Bii-iii; CXCR4 MFI for baseline control was 15 212 ± 452; for 7 days no DWJM, 13 258 ± 510; and 7 days with DWJM, 26 547 ± 782). We further examined whether DWJM-induced phenotypical changes, such as an increase in CXCR4 cell surface expression (Figure 7Bii-iii), resulted in functional alterations such as improved migration. DWJM-cultured CD34+ cells showed a higher transmigration frequency when compared with CD34+ cells in the control condition (Figure 8Biv #3 and #5 vs #1). BM MSCs, on the other hand, impaired and suppressed the migration efficiency of CD34+ cells (Figure 7Biv #2, #4, and #6), and overrode the effects of DWJM in promoting transmigration (Figure 7Biv #3 vs #4, #5 vs #6). Furthermore, we examined DWJM-induced CXCR4 expression on UCB CD34+ cells stratified by their migration capabilities, using transwell assay and phenotype, and focusing on CD34+CD45+ cell subset using flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 6, results summarized in supplemental Data).

DWJM alters UCB CD34+ cell gene expression profile

We used RNAseq and qPCR to elucidate how UCB CD34+ cell interaction with DWJM alters cell differentiation and in vivo trafficking of CD34+ cells at the molecular level. Cells derived from 7-day culture in the absence or presence of DWJM were analyzed by RNAseq (Figure 8A). DWJM upregulated a set of genes (Figure 8C; Table 1) that could be categorized into 3 groups, based on their biological functions (Table 2), as described below.

RNAseq analysis of CD34+ cell genes that are altered by DWJM

| Effect of DWJM . | Genes of HSPCs . | Log2 (fold change) . | Adjusted P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulation | GATA2 | 1.50 | 1.61e-28 |

| CDKN1A | 1.42 | 5.70e-11 | |

| TAL1 | 1.20 | 2.05e-03 | |

| MECOM | 1.18 | 1.72e-01 | |

| ITGβ3 | 0.94 | 3.39e-02 | |

| ITGA2B | 0.86 | 2.47e-09 | |

| NTRK1 | 0.78 | 2.40e-02 | |

| PRKCQ | 0.63 | 1.01e-02 | |

| Downregulation | IL6R | −0.73 | 1.49e-03 |

| MPO | −1.24 | 7.34e-03 | |

| MIR223 | −1.31 | 8.60e-06 | |

| CHI3L1 | −1.36 | 2.52e-03 | |

| CSF1R | −1.97 | 3.20e-18 | |

| CTSG | −2.00 | 1.64e-07 | |

| CST7 | −2.38 | 2.14e-40 |

| Effect of DWJM . | Genes of HSPCs . | Log2 (fold change) . | Adjusted P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulation | GATA2 | 1.50 | 1.61e-28 |

| CDKN1A | 1.42 | 5.70e-11 | |

| TAL1 | 1.20 | 2.05e-03 | |

| MECOM | 1.18 | 1.72e-01 | |

| ITGβ3 | 0.94 | 3.39e-02 | |

| ITGA2B | 0.86 | 2.47e-09 | |

| NTRK1 | 0.78 | 2.40e-02 | |

| PRKCQ | 0.63 | 1.01e-02 | |

| Downregulation | IL6R | −0.73 | 1.49e-03 |

| MPO | −1.24 | 7.34e-03 | |

| MIR223 | −1.31 | 8.60e-06 | |

| CHI3L1 | −1.36 | 2.52e-03 | |

| CSF1R | −1.97 | 3.20e-18 | |

| CTSG | −2.00 | 1.64e-07 | |

| CST7 | −2.38 | 2.14e-40 |

A positive value indicates an upregulation, whereas a negative value indicates a downregulation of genes in CD34+ UCB cells by DWJM. Genes upregulated by DWJM are labeled in bold.

Summary of RNAseq analysis on CD34+ cell genes that are altered by DWJM, with genes categorized by function

| Overall function . | Gene symbol . | Fold change . | Significance . | Specific gene function . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Megakaryocytic differentiation | GATA2 | 2.82 | 3.61e-31 | GATA2 has been shown to be associated with megakaryocytic lineage commitment |

| MEIS1 | 2.51 | 3.37e-07 | MEIS1 expression is associated with lineage commitment toward a megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor commitment | |

| VWF | 2.63 | 1.24e-07 | VWF expression by flow cytometry is associated with early megakaryocytic differentiation | |

| Clu | 2.35 | 2.55e-07 | Clu messenger RNA is detected in megakaryocytes from the BM, and as plasma glycoprotein, it was found mainly in platelets, suggesting that CLU is produced by megakaryocytes during megakaryocyte development | |

| Selp | 3.10 | 3.24e-09 | Selp also plays a role in late stage of megakaryopoiesis as Selp expression is seen in mature megakaryocytes | |

| ltga2b(CD41) | 1.82 | 2.33e-11 | Ltga2b expression is a marker of definition and primitive hematopoiesis in murine embryo; however, its regulation is also linked to megakaryocytic lineage commitment | |

| Cell mobility, transmigration, and homing | CXCR4 | 1.88 | 7.98e-08 | CXCR4 is known for its important role in homing of HSPC to the BM |

| CXCL8 | 52.65 | 1.08e-245 | CXCL8 was recently found to play a role in HSPC colonization of the sinusoidal endothelial niche and engraftment in zebrafish | |

| HSC markers | ALDH1 | 1.68 | 8.35e-05 | ALDH1 is a stem cell marker as it was found to be overexpressed in HSCs |

| FOS | 7.87 | 6.91e-69 | FOS has been linked to increased HSC repopulation activity. An increase in FOS expression is seen in UCB CD34+ cells cultured in DWJM. | |

| SRGN | −5.14 | 3.68e-83 | SRGN downregulation was found to be associated with undifferentiated human fetal phenotype. |

| Overall function . | Gene symbol . | Fold change . | Significance . | Specific gene function . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Megakaryocytic differentiation | GATA2 | 2.82 | 3.61e-31 | GATA2 has been shown to be associated with megakaryocytic lineage commitment |

| MEIS1 | 2.51 | 3.37e-07 | MEIS1 expression is associated with lineage commitment toward a megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor commitment | |

| VWF | 2.63 | 1.24e-07 | VWF expression by flow cytometry is associated with early megakaryocytic differentiation | |

| Clu | 2.35 | 2.55e-07 | Clu messenger RNA is detected in megakaryocytes from the BM, and as plasma glycoprotein, it was found mainly in platelets, suggesting that CLU is produced by megakaryocytes during megakaryocyte development | |

| Selp | 3.10 | 3.24e-09 | Selp also plays a role in late stage of megakaryopoiesis as Selp expression is seen in mature megakaryocytes | |

| ltga2b(CD41) | 1.82 | 2.33e-11 | Ltga2b expression is a marker of definition and primitive hematopoiesis in murine embryo; however, its regulation is also linked to megakaryocytic lineage commitment | |

| Cell mobility, transmigration, and homing | CXCR4 | 1.88 | 7.98e-08 | CXCR4 is known for its important role in homing of HSPC to the BM |

| CXCL8 | 52.65 | 1.08e-245 | CXCL8 was recently found to play a role in HSPC colonization of the sinusoidal endothelial niche and engraftment in zebrafish | |

| HSC markers | ALDH1 | 1.68 | 8.35e-05 | ALDH1 is a stem cell marker as it was found to be overexpressed in HSCs |

| FOS | 7.87 | 6.91e-69 | FOS has been linked to increased HSC repopulation activity. An increase in FOS expression is seen in UCB CD34+ cells cultured in DWJM. | |

| SRGN | −5.14 | 3.68e-83 | SRGN downregulation was found to be associated with undifferentiated human fetal phenotype. |

Megakaryocytic differentiation.

When UCB CD34+ cells were cultured in DWJM, the following master transcription factors were found to be upregulated: GATA1, GATA2, and TAL1. Of these, GATA2 has been reported to be associated with megakaryocytic lineage commitment.35 In addition to these master transcription genes, several other genes involved with megakaryocyte differentiation were upregulated in UCB CD34+ cells cultured in DWJM, including MEIS1, VWF, Clu Selp, and Itga2b (CD41) (Table 2). In CD34+ cells cultured in DWJM, other factors involved in megakaryocyte development and platelet production were found to be significantly, positively correlated with upregulated genes, providing further evidence of a megakaryocyte lineage bias in DWJM cultured cells (supplemental Figure 5).

Cell mobility, transmigration, and homing.

HSPC stem cell markers.

As previously stated, a significant CD34+ cell type enrichment was identified among genes upregulated in response to the DWJM-based culture system (Table 2). In contrast, analysis of downregulated genes identified several differentiated cell types, such as CD33+ myeloid, monocytes, dendritic cells, and whole blood (Figure 8C). Taken together, these data suggest the culture system maintains CD34+ cells in a more immature, stemlike state, rather than promoting differentiation.

qPCR reactions were performed to confirm the NAseq findings on DWJM-induced genes that were upregulated (Figure 8B). As shown in Figure 8B, qPCR confirmed the upregulation of CD41 and VWF in cells adherent to DWJM compared with control cells in suspension. No statistically significant changes in these gene expressions were detected in DWJM-adherent cells compared with nonadherent cells in the DWJM-based culture system.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the potential of combining DWJM and BM MSCs to serve as an in vitro biomimetic scaffold that mimics the in vivo BM hematopoietic niche. Our goal was to support the proliferation of CD34+ cells, while maintaining their primitive phenotype and function, so they can be grown in quantity for clinical transplantation. We showed that DWJM maintained UCB HSPCs’ primitive phenotype with a higher self-renewal capability, effectively preserved the multilineage differentiation potentials of HSPCs, biased HSPC differentiation toward megakaryocytes, improved CXCR4-SDF1-mediated migration of CD34+ cells via CXCR4 upregulation, and activated genes that are related to ECM adhesion, extravasation, homing, and engraftment. Our studies provide a detailed characterization of phenotypic and functional alterations of HSPCs by DWJM and suggest that DWJM expands the HSPC population well. Hence, DWJM holds great potential in supporting HSPC expansion ex vivo.

Numerous recent studies5-8,10,36 have attempted to create an in vitro culture system that can be used to dissect critical biological events in human HSPC differentiation. One strategy has been to add growth factors or specific cell subsets selectively to HSPC cultures in order to examine their effects on HSPC self-renewal and differentiation. Previous studies have demonstrated that endothelial and perivascular cells,37 BM MSCs,21,38-40 bone-forming osteoblasts,41-44 and anti-CD43 and anti-CD44 antibodies8 support long-term HSPC expansion in vitro. Under these conditions, HSPCs are able to differentiate into erythrocyte,45 megakaryocyte,46 monocyte/macrophage,47 natural killer cells,48 T cells,49 and B cells.50 In this study, we demonstrated that use of DWJM in tissue engineering for clinical applications offers advantages over these other in vitro models. DWJM enhanced UCB CD34+ cell colony-forming potential (Figure 3), preserved the stemness and primitive phenotype of HSPCs (Figures 5 and 6), and improved the migration defects of UCB CD34+ cells by CXCR4 upregulation (Figure 7).

Although the role of MSCs in supporting the differentiation and proliferation of HSPCs has been previously studied,51-56 our results provide new insights into the role of MSCs in HSPC activation, and the combined effects of MSCs and DWJM on HSPC phenotypes. Our results suggest that although DWJM promotes the formation of BFU-E and CFU-GM, BM MSCs antagonize DWJM effects in promoting the formation of BFU-E but not CFU-GM (Figure 3D-F). Also, we found that DWJM preseeded with MSCs enhanced CD34+ cell proliferation and differentiation, whereas DWJM alone maintained the stemness and primitive phenotype of HSPCs, which is the typical physiologic state of HSCs. Our observations are in line with published literature that suggests that MSCs cause significant CD34+ cell proliferation with enhanced BFU-E differentiation potential.57 Our findings indicate that fast-dividing cells lose their CD34+ phenotype more frequently, whereas UCB CD34+ cells cultured in DWJM preferentially maintain their CD34+ phenotype (Figure 2Biii-iv). By studying the expression of CD41, CD38, and CXCR4 on CD34+ cells (Figures 4, 5A, and 7A), we demonstrated that the presence of MSCs thoroughly antagonized and overrode DWJM’s enhancement of the expression of CD41, CD38, and CXCR4, a phenomenon not previously described. By applying stringent criteria to define the HSC population, we show evidence that DWJM specifically enhances the expansion of the HSC population (Figure 6H). Collectively, our data indicate that DWJM as a culture system expands the HSC population (visual abstract) and thus is a rational choice to support the expansion of HSCs ex vivo.

BM homing of HSPCs is a complex process that requires a coordinated action between several molecules (CXCR4, Robo4, integrin, EPOR, and more) in a timely and temporal fashion.7,23,58-61 The CXCR4/SDF-1 axis in particular is critical in controlling the BM homing of HSPCs.62 Our experiments using flow analysis suggest that DWJM induces CXCR4 cell surface expression (Figures 7Bi-ii and 8A), and RNAseq analysis confirmed this finding at the molecular level (Figures 7B and 8A). In addition, the CXCR4/SDF-1 axis controlled enhancement of transmigration capability (Figure 8Biv). Our results not only underscore the potential of clinical applications of DWJM in ex vivo HSPC expansion but also provide a novel strategy to overcome the BM homing defects of UCB CD34+ cells.

In summary, we have demonstrated that DWJM is a novel platform for ex vivo UCB CD34+ cell culture, which maintains HSPC primitive phenotypes and supports their potential for lineage differentiation and transmigration. These efforts will guide and enhance future clinical applications of DWJM in tissue regeneration and UCB transplantation in patients with hematologic and nonhematologic malignancies.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the University of Kansas Medical Center flow core for the technical support in flow cytometry, Sushma Jadalannagari and Thomas Conley for their help with umbilical cord collection, and also Andrea Baran for her help with some of the statistical analyses. Human BM MSCs were processed and stored by the Biospecimen Repository Core Facility of the University of Kansas Cancer Center.

This work was supported by a grant from the Office of Scholarly, Academic, and Research Mentoring at the University of Kansas Medical Center and the Robert K. Dempski Cord Blood Research Fund. The authors thank the St. Louis Cord Blood Bank and New York Blood Center for making UCB units available for the studies. The authors acknowledge the Flow Cytometry Core Laboratory at the University of Kansas Medical Center, which is sponsored, in part, by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences COBRE grant P30 GM103326.

Authorship

Contribution: O.S.A., D.L., G.C., and R.A.H. designed the experiments; D.L. and G.C. performed the experiments; O.S.A., D.L., G.C., B.L., J.L., J.M.A., and S.P. analyzed the data; D.L., G.C., J.L., and O.S.A. wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: O.S.A. has a pending patent application indirectly related to this work. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Omar S. Aljitawi, School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Rochester Medical Center, 601 Elmwood Ave, Box 704, Rochester, NY 14642; e-mail: omar_aljitawi@urmc.rochester.edu.