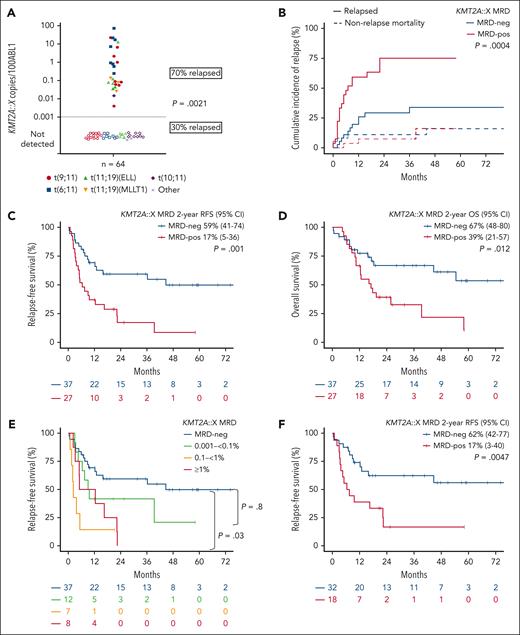

Pretransplant detection of KMT2Ar measurable residual disease ≥0.001% by quantitative polymerase chain reaction was associated with significantly inferior posttransplant survival (2-year relapse-free survival 17% vs 59%; P = .001) and increased 2-year cumulative incidence of relapse (75% vs 25%, P = .0004).

TO THE EDITOR:

KMT2A-rearranged (KMT2Ar) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is generally associated with adverse prognosis, with allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) in first remission (CR1) considered standard of care in most cases.1,2 Despite HCT, ∼40% of patients are destined to have relapsed disease.3 For those in remission prior to HCT, small retrospective studies suggest higher relapse risk if KMT2Ar molecular measurable residual disease (MRD) is detected prior to transplant.4-7KMT2Ar is stable at relapse, making it a suitable MRD marker for quantitative monitoring.8 One barrier to implementation of KMT2Ar MRD monitoring, however, is breakpoint heterogeneity within the KMT2A gene itself and its association with a diverse array of partner fusion genes. Despite >100 translocation partner genes identified, >70% of KMT2A fusions implicated in AML involve either MLLT3 [t(9;11)], ELL [t(11;19) (q23;p13.1)], AFDN [t(6;11)], or MLLT10 [t(10;11)]. Furthermore, the majority of KMT2A genomic breakpoints occur within the major breakpoint cluster regions of introns 8, 9, 10, and 11.9,10

This study analyzes the clinical relevance of pre-HCT KMT2Ar MRD detection by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and the prognostic impact on post-HCT outcome in adults with KMT2Ar AML. We also describe a novel reverse transcription droplet digital PCR (RT-dPCR) assay that allows a large majority of patients with KMT2Ar AML to be quantitatively monitored using a simplified multiplexed assay. The relevance of this study is enhanced by clinical development of menin inhibitors showing promising efficacy in patients with relapsed or refractory KMT2Ar AML and potential to detect and preemptively target KMT2Ar MRD using targeted therapies.4,11,12

A cohort of 64 patients treated in Australia, United Kingdom, and Taiwan were included. Patients had KMT2Ar confirmed by karyotyping and fluorescence in situ hybridization or RNA sequencing at diagnosis. Within 100 days pre-HCT and with no intervening therapy between sample collection and transplant conditioning, pre-HCT MRD data were available in 45 patients, and MRD assessment was undertaken on archived samples from 19 patients. Association with clinical outcome was performed through retrospective review. Pre-HCT RNA from bone marrow (n = 59) or peripheral blood (if bone marrow was unavailable; n = 5) were assessed by RT-qPCR (n = 55)13 or RT-dPCR (n = 9) using a novel multiplexed assay combining a master mix of 3 forward primers to KMT2A gene and a pooled array of 7 reverse primers (targeting common fusion partner genes MLLT3, ELL, AFDN, and AFF1), permitting quantitation of common KMT2Ar fusion genes in a single assay (see supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website). Reverse primers to MLLT10 and MLLT1 were run separately and not included in the reverse primer pool due to the high degree of breakpoint heterogeneity. Results were expressed as KMT2A::X copies per 100 ABL1. Assay sensitivity was ∼0.001%. Survival outcomes were estimated by Kaplan-Meier for relapse-free survival (RFS, HCT date to relapse or death or last follow-up) and overall survival (OS, to date of death or last follow-up). Cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR) was calculated using cumulative incidence function with nonrelapse mortality as a competing risk. Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher exact test; continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Cox proportional hazards was used to assess variables impacting survival. Variables with P < .1 on univariate analysis were taken forward to multivariate analysis. The study was approved by human research ethics committees at each center.

Median age was 43 years (17-70), 8% had therapy-related AML, and the remainder had de novo disease (Table 1). All patients had received prior intensive chemotherapy and were in remission at the time of HCT; 78% received transplants in CR1, 49% from an unrelated donor, 60% received T-cell depletion, and 46% received myeloablative conditioning. KMT2A partner genes are summarized in Table 1. Median time between MRD sampling and HCT was 24 days (1-93).

Baseline characteristics

| Variables at diagnosis, n (%) unless specified . | All patients (n = 64) . | Pretransplant KMT2A::X MRD status . | P value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRD-positive (n = 27) . | MRD-negative (n = 37) . | |||

| Median age, y (range) | 43 (17-70) | 42 (19-68) | 43 (17-70) | .84 |

| Females | 44 (69) | 18 (41) | 26 (59) | .79 |

| AML subtype | .64 | |||

| De novo | 59 (92) | 24 (41) | 35 (59) | |

| Therapy-related AML | 5 (8) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | |

| KMT2A::X fusion partner | .05 | |||

| t(9;11)/MLLT3 | 22 (34) | 9 (41) | 13 (59) | |

| t(6;11)/AFDN | 16 (25) | 8 (50) | 8 (50) | |

| t(11;19)/ELL | 11 (17) | 6 (55) | 5 (45) | |

| t(10;11)/MLLT10 | 10 (16) | 1 (10) | 9 (90) | |

| t(11;19)/MLLT1 | 3 (5) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | |

| Frontline therapy | ||||

| Intensive chemotherapy | 64 (100) | 27 | 37 | — |

| ELN 2022 risk | .99 | |||

| Adverse | 42 (66) | 18 (43) | 24 (57) | |

| Conditioning | ||||

| Myeloablative | 25 of 54 (46) | 12 of 22 (48) | 13 of 32 (52) | .41 |

| Transplant status | .07 | |||

| CR1 | 50 (78) | 18 (36) | 32 (64) | |

| CR2 | 14 (22) | 9 (64) | 5 (36) | |

| T-cell depletion | 28 of 47 (60) | 8 of 18 (29) | 20 of 29 (71) | .13 |

| Unrelated donor | 31 of 63 (49) | 11 of 26 (35) | 20 of 37 (65) | .45 |

| Variables at diagnosis, n (%) unless specified . | All patients (n = 64) . | Pretransplant KMT2A::X MRD status . | P value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRD-positive (n = 27) . | MRD-negative (n = 37) . | |||

| Median age, y (range) | 43 (17-70) | 42 (19-68) | 43 (17-70) | .84 |

| Females | 44 (69) | 18 (41) | 26 (59) | .79 |

| AML subtype | .64 | |||

| De novo | 59 (92) | 24 (41) | 35 (59) | |

| Therapy-related AML | 5 (8) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | |

| KMT2A::X fusion partner | .05 | |||

| t(9;11)/MLLT3 | 22 (34) | 9 (41) | 13 (59) | |

| t(6;11)/AFDN | 16 (25) | 8 (50) | 8 (50) | |

| t(11;19)/ELL | 11 (17) | 6 (55) | 5 (45) | |

| t(10;11)/MLLT10 | 10 (16) | 1 (10) | 9 (90) | |

| t(11;19)/MLLT1 | 3 (5) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | |

| Frontline therapy | ||||

| Intensive chemotherapy | 64 (100) | 27 | 37 | — |

| ELN 2022 risk | .99 | |||

| Adverse | 42 (66) | 18 (43) | 24 (57) | |

| Conditioning | ||||

| Myeloablative | 25 of 54 (46) | 12 of 22 (48) | 13 of 32 (52) | .41 |

| Transplant status | .07 | |||

| CR1 | 50 (78) | 18 (36) | 32 (64) | |

| CR2 | 14 (22) | 9 (64) | 5 (36) | |

| T-cell depletion | 28 of 47 (60) | 8 of 18 (29) | 20 of 29 (71) | .13 |

| Unrelated donor | 31 of 63 (49) | 11 of 26 (35) | 20 of 37 (65) | .45 |

CR1, first remission; CR2, second remission; ELN, European LeukemiaNet.

Pre-HCT, 42% (27 of 64) were KMT2Ar MRD-positive, with the median MRD level 0.1200% (range, 0.0056%-35.0394%) (Figure 1A). Apart from a higher proportion of t(11;19)/KMT2A::MLLT1 in the MRD-positive cohort, and t(9;11) and t(10;11) in the MRD-negative cohort, no other baseline characteristics were found to be significantly associated with KMT2Ar MRD-positive status pre-HCT (Table 1).

KMT2Ar MRD level distribution and outcomes posttransplant. (A) Pretransplant KMT2A::X MRD distribution according to fusion-gene type. (B) KMT2A::X MRD detection pre-HCT is significantly associated with increased relapse incidence. CIR with nonrelapse mortality as competing risk according to pre-HCT MRD status. Significance of test is assessed using Gray's test. (C-D) Kaplan-Meier estimates of (C) RFS and (D) OS according to pre-HCT MRD status. (E) Relapse-free survival according to pretransplant KMT2A::X MRD threshold range: MRD-negative (<0.001%), 0.001% to <0.1%, 0.1% to <1%, and ≥1%. (F) RFS in patients who received transplant in CR1 according to MRD status (n = 50). CI, confidence interval; neg, negative; pos, positive.

KMT2Ar MRD level distribution and outcomes posttransplant. (A) Pretransplant KMT2A::X MRD distribution according to fusion-gene type. (B) KMT2A::X MRD detection pre-HCT is significantly associated with increased relapse incidence. CIR with nonrelapse mortality as competing risk according to pre-HCT MRD status. Significance of test is assessed using Gray's test. (C-D) Kaplan-Meier estimates of (C) RFS and (D) OS according to pre-HCT MRD status. (E) Relapse-free survival according to pretransplant KMT2A::X MRD threshold range: MRD-negative (<0.001%), 0.001% to <0.1%, 0.1% to <1%, and ≥1%. (F) RFS in patients who received transplant in CR1 according to MRD status (n = 50). CI, confidence interval; neg, negative; pos, positive.

CIR was significantly increased among patients KMT2Ar MRD-positive vs MRD-negative pre-HCT (2-year CIR 75% vs 25%, P = .0004) (Figure 1B). KMT2Ar as a marker of relapse was highly stable, with all assessable patients (n = 22) retaining the same fusion gene at relapse. With 37 months median follow-up time, survival was significantly inferior in patients MRD-positive vs MRD-negative pre-HCT, with 2-year RFS 17% vs 59% (P = .001) and 2-year OS of 39% vs 67% (P = .012) (Figure 1C-D). Pre-HCT MRD-positive status was the only determinant of inferior RFS (hazard ratio 2.6, 95% confidence interval 1.3-5.1, P = .007) and OS on univariate and multivariate analyses. Two-year RFS if KMT2A::X MRD was negative, 0.001% to <0.1%, 0.1% to <1% or ≥1% were 59%, 42%, 0% or 0%, respectively (Figure 1E). Myeloablative conditioning did not abrogate the inferior survival outcome of pre-HCT MRD-positive status (supplemental Figure 2). Insufficient cases were available to confirm association between co-mutation profile and risk of pre-HCT MRD or survival outcome (supplemental Figure 4). Survival was also significantly inferior for pre-HCT MRD-positive status when analysis was restricted to patients who underwent CR1 transplant (2-year RFS 17% vs 62%, P = .0047), to exclude the confounding adverse impact on survival of transplant in CR2 (Figure 1F).

Survival analysis of 22 patients with t(9;11), categorized as European LeukemiaNet intermediate risk, was explored to determine if pre-HCT MRD status could refine prognostication.1 Pre-HCT MRD detection of KMT2A::MLLT3 MRD was significantly associated with poor survival, with 2-year RFS and OS both 11%, compared with 68% and 67% for patients with KMT2A::MLLT3 MRD-negative status (P = .032 and .048, respectively) (supplemental Figure 3). Whether patients with KMT2A::MLLT3 MRD-negative status at the end of treatment could be spared CR1 transplant requires evaluation in future larger confirmatory cohorts.

To enable KMT2Ar MRD monitoring, baseline bone marrow or peripheral blood RNA should be routinely stored at diagnosis. KMT2Ar at diagnosis is generally identified by either cytogenetic and fluorescence in situ hybridization (specific intron-exon breakpoint unknown) techniques or through use of either RNA sequencing or a targeted RNA fusion panel. The multiplex RT-dPCR assay presented in this article may be used to monitor patients if the KMT2A fusion partner involves either chromosome 9, 19p13.1, 6, or 4 and a diagnostic screening sample is confirmed to be positive using the multiplexed technique. If the KMT2A fusion partner involves chromosomes 10 or 19p13.3, probes to common break points involving these partner genes are required for RT-dPCR or qPCR monitoring. Patient-specific primer or probes may be required for other rare translocations or breakpoint locations outside of the commonly affected regions.

This study, the largest that we know of, highlights the dismal prognosis associated with KMT2Ar MRD detected pretransplant. With next-generation sequencing-based targeted RNA fusion panels increasingly performed at diagnosis, KMT2Ar detection and quantitative MRD tracking will become more commonplace. We also describe the design and validation of a multiplexed RT-dPCR assay able to monitor ∼60% of KMT2Ar (or ∼80% excluding MLLT10 or MLLT1) occurring in adult AML.9 These strategies now pave the way for MRD-directed pre- and post-HCT intervention using menin-targeted therapies, aimed at reducing relapse risk and improving overall patient outcome.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by fellowships and grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council 1162809 (A.H.W.), Metcalf Family Fellowship (A.H.W.), Medical Research Future Fund 1141460 (A.H.W.), Australian Cancer Research Foundation, Cancer Research UK (AML M17), Ministry of Science and Technology (Taiwan) (MOST 111-2314-B-002-279), and the Ministry of Health and Welfare (Taiwan) (MOHW 111-TDU-B-221-114001). Institutional review board: Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and Royal Melbourne Hospital, Alfred Hospital, King’s College London, University College London NHS Foundation Trust and National Taiwan University Hospital.

Authorship

Contribution: A.H.W. and S.L. designed the research; A.I. designed and validated KMT2A::X RT-dPCR MRD assay; A.I., N.P., R.M., J.J., R.B., H.A.H., and S.L. sequenced and analyzed the samples or provided other molecular analysis tools and interpretation; N.P., J. O’Nions, J. Othman, and S.L. performed clinical data collection; S.L. performed the statistical analysis; S.L., N.P., J. O’Nions, C.Y.F., N.S.A., I.S.T., J. Othman, C.C.C., H.R., R.B., S.F., N.H.R. D.R., A.B., H.A.H., R.D., and A.H.W. contributed patients or analyzed and interpreted data; S.L. and A.H.W. wrote the manuscript; and all authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.H.W. receives honoraria for participation on advisory boards and research funding to the institution from Janssen and Syndax related to the development of menin inhibitors. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Andrew H. Wei, Department of Haematology, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and Royal Melbourne Hospital, 305 Grattan St, Parkville, VIC 3000, Australia; email: andrew.wei@petermac.org.

References

Author notes

S.L. and N.P. contributed equally to this work.

Molecular data supporting the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, Andrew Wei (andrew.wei@petermac.org).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal