T-ALL relapse usually occurs early but can occur much later, which has been suggested to represent a de novo leukemia. However, we conclusively demonstrate late relapse can evolve from a pre-leukemic subclone harbouring a non-coding mutation that evades initial chemotherapy.

TO THE EDITOR:

Relapse in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) typically occurs early, while patients are still undergoing treatment.1 Relapse usually represents reemergence of clones sharing the same T-cell receptor (TCR) rearrangement as the original leukemia, with acquisition of chemotherapy-resistance mutations, such as those in NT5C2.2,3 However, rarely, recurrence occurs much later.4 Previous work characterizing late relapses found divergence of TCR rearrangements from the original disease, suggesting the leukemias were clonally unrelated.4 This was supported by changes in NOTCH1 mutations between presentation and relapse, leading the authors to conclude that the leukemias derived from separate founder clones. However, NOTCH1 mutations are often acquired late in disease evolution, making it difficult to determine this definitively.5-7

With the advent of whole genome sequencing, we aimed to conclusively ascertain the origin of late relapse through tracking of genomic lesions, particularly noncoding driver and passenger events not addressed in previous studies. Results carry important implications for patients; a true second malignancy suggests an underlying germ line predisposition requiring further genetic testing and counseling. Alternatively, a clonally related relapse indicates failure of frontline therapy and the need for treatment intensification.

Patients with late relapse of T-ALL were identified from the UKALL97/99 and UKALL2003 trial databases. Based on previous work, we defined late relapse as relapse occurring more than 5 years from diagnosis.4 Two further cases were identified from clinical discussions at the UK Leukemia Advisory Board Meeting.

Analysis of TCR sequences was performed by next-generation sequencing as previously described.8

Whole genome sequencing was performed by Novogene Ltd (Cambridge, UK) using Illumina sequencing to generate 150-base-pair paired-end reads at 50× coverage in tumor samples and 30× in germ line samples. Details of somatic and germ line variant calling can be found in the supplementary methods, available on the Blood website.

We identified 10 patients with late relapse and available samples. Median time between to relapse was 6 years (range 5-8 years). TCR sequencing showed 3 cases retained the same rearrangement at relapse while 7 cases showed no relation between presentation and relapse. These 7 cases underwent whole genome sequencing; 4 had matched germ line tissue available.

The median number of coding single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertion-deletions (indels) did not differ between time points with 14 at presentation (range 7-330) and 18 at relapse (range 10-741), in contrast to studies showing an increased mutational burden at relapse.2,9,10 Importantly, not a single coding SNV or indel in a driver gene was shared between presentation and relapse, consistent with the notion that they are separate leukemias (Table 1).

Somatic coding variants differ between initial diagnosis and relapse

| Patient . | Age at diagnosis (y) . | Time to relapse (y) . | Germ line tissue available . | Presentation variants . | Relapse variants . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNV/indel . | CDKN2A . | SV . | Noncoding . | SNV/indel . | CDKN2A . | SV . | Noncoding . | ||||

| P003 | 1 | 5 | Yes | AKT1 I447M, CNOT3 D218fs, GNB1 K89E, LEF1 T237fs, NF1 E1787G, PBRM1 S25P, PTEN R233fs, SMARCA4 K1365E | 68-kb HetDel | IL7R E47A, FAT1 N3678D, NOTCH1 Q2444∗, RB1 E693K | 137-kb HomDel | ||||

| P042 | 6 | 6 | No | IL7R T244fs, LEF1 Q80, NOTCH1 P2514fs, RPL22 L86H, USP7 A571fs | 1.9-Mb HomDel | t(7;11) (TRB-LMO2) | TAL1 intron 1 SNV | IL7R L242C, NOTCH1 Q2409fs, NOTCH1 L2408R, NOTCH1 F1592C, STAT5B D475N | 110-kb HomDel | t(11;14) (LMO2-TRA) | TAL1 intron 1 SNV |

| P044 | 5 | 6 | No | FBXW7 R609W, NOTCH1 Q2444∗, USP7 V256fs | 10-Mb HomDel | DNM2 G358R, MED12 Y204∗, NOTCH1 L1574P, NRAS G12D, U2AF1 E143K | |||||

| P046 | 12 | 6 | No | PTEN N228fs | 85-bp LMO2 intron 1 duplication TAL1 neo-enhancer | PTEN R233fs | 55-kb HomDel | STIL-TAL1 deletion | 85-bp LMO2 intron 1 duplication | ||

| P047 | 1 | 5 | Yes | ASXL1 G646fs, CNOT3 S245fs, FAT1 F3135L, IKZF1 V20fs, MED12 R2015K, NOTCH1 L1678P, PBRM1 K1373E, PHF6 N222fs, PTEN T319S, PTPRC L372P, STAT5B A529S, SUZ12 H620R | DNM2 I524T, DNMT3A M548V, EP300 M2227V, FBWX7 R393fs, FBWX7 L221P, JAK3 H962R, KMT2A I1393fs, KMT2D S1037P, MED12 L1446P, NOTCH1 L1678P, NOTCH1 S797P, NF1 L216P, NF1 L303P, PHF6 Y301H, PTPRC L834P, SETD2 K1020R, SMARCA4 L1035Q, SMARCA4 S1475G, TRRAP Y376C, ZFP36L2 S257G | 550-kb HetDel | |||||

| P048 | 6 | 7 | Yes | KMT2D Q3905L, NOTCH1 F1592S, USP7 D305H, WT1 P141del | 2.8-Mb HomDel | STIL-TAL1 deletion | 84-bp LMO2 intron 1 duplication | IDH2 N211S, NOTCH1 T2466fs | 800-kb HetDel | STIL-TAL1 deletion (alternative breakpoints) | 84-bp LMO2 intron 1 duplication |

| P049 | 2 | 6 | Yes | CREBBP Q3761A, FAT1 F3478S, KMT2D C3132∗, PTEN R233fs | 19-kb HomDel | 89-bp LMO2 intron 1 duplication TAL1 Neo-enhancer | ARID1A G655V, ATM T1985A, DNM2 N282D, KMT2A G3716A, PTEN M239_Y240insE, USP7 T592fs | 5-kKb HetDel | STIL-TAL1 deletion | 89-bp LMO2 intron 1 duplication | |

| Patient . | Age at diagnosis (y) . | Time to relapse (y) . | Germ line tissue available . | Presentation variants . | Relapse variants . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNV/indel . | CDKN2A . | SV . | Noncoding . | SNV/indel . | CDKN2A . | SV . | Noncoding . | ||||

| P003 | 1 | 5 | Yes | AKT1 I447M, CNOT3 D218fs, GNB1 K89E, LEF1 T237fs, NF1 E1787G, PBRM1 S25P, PTEN R233fs, SMARCA4 K1365E | 68-kb HetDel | IL7R E47A, FAT1 N3678D, NOTCH1 Q2444∗, RB1 E693K | 137-kb HomDel | ||||

| P042 | 6 | 6 | No | IL7R T244fs, LEF1 Q80, NOTCH1 P2514fs, RPL22 L86H, USP7 A571fs | 1.9-Mb HomDel | t(7;11) (TRB-LMO2) | TAL1 intron 1 SNV | IL7R L242C, NOTCH1 Q2409fs, NOTCH1 L2408R, NOTCH1 F1592C, STAT5B D475N | 110-kb HomDel | t(11;14) (LMO2-TRA) | TAL1 intron 1 SNV |

| P044 | 5 | 6 | No | FBXW7 R609W, NOTCH1 Q2444∗, USP7 V256fs | 10-Mb HomDel | DNM2 G358R, MED12 Y204∗, NOTCH1 L1574P, NRAS G12D, U2AF1 E143K | |||||

| P046 | 12 | 6 | No | PTEN N228fs | 85-bp LMO2 intron 1 duplication TAL1 neo-enhancer | PTEN R233fs | 55-kb HomDel | STIL-TAL1 deletion | 85-bp LMO2 intron 1 duplication | ||

| P047 | 1 | 5 | Yes | ASXL1 G646fs, CNOT3 S245fs, FAT1 F3135L, IKZF1 V20fs, MED12 R2015K, NOTCH1 L1678P, PBRM1 K1373E, PHF6 N222fs, PTEN T319S, PTPRC L372P, STAT5B A529S, SUZ12 H620R | DNM2 I524T, DNMT3A M548V, EP300 M2227V, FBWX7 R393fs, FBWX7 L221P, JAK3 H962R, KMT2A I1393fs, KMT2D S1037P, MED12 L1446P, NOTCH1 L1678P, NOTCH1 S797P, NF1 L216P, NF1 L303P, PHF6 Y301H, PTPRC L834P, SETD2 K1020R, SMARCA4 L1035Q, SMARCA4 S1475G, TRRAP Y376C, ZFP36L2 S257G | 550-kb HetDel | |||||

| P048 | 6 | 7 | Yes | KMT2D Q3905L, NOTCH1 F1592S, USP7 D305H, WT1 P141del | 2.8-Mb HomDel | STIL-TAL1 deletion | 84-bp LMO2 intron 1 duplication | IDH2 N211S, NOTCH1 T2466fs | 800-kb HetDel | STIL-TAL1 deletion (alternative breakpoints) | 84-bp LMO2 intron 1 duplication |

| P049 | 2 | 6 | Yes | CREBBP Q3761A, FAT1 F3478S, KMT2D C3132∗, PTEN R233fs | 19-kb HomDel | 89-bp LMO2 intron 1 duplication TAL1 Neo-enhancer | ARID1A G655V, ATM T1985A, DNM2 N282D, KMT2A G3716A, PTEN M239_Y240insE, USP7 T592fs | 5-kKb HetDel | STIL-TAL1 deletion | 89-bp LMO2 intron 1 duplication | |

Mutations shared at diagnosis and relapse shown in bold. SV, structural variant; HetDel, heterozygous deletion; HomDel, homozygous deletion.

The most prevalent lesions in T-ALL are large chromosome 9p deletions encompassing the tumor suppressor gene CDKN2A.11 Accordingly, CDKN2A deletions were present in 11 of 14 samples (78.6%) but differed at presentation and relapse in all patients, being either lost at relapse (n = 3) or occurring with different breakpoints (Table 1, supplemental Figure 1).

T-ALL subtypes are based on aberrant transcription factor expression resulting from structural variants.11,12 Crucially, these events are considered the initiating lesion and do not change between presentation and relapse. However, in 2 patients, the STIL-TAL1 deletion was present only at relapse (Table 1). A further case carried STIL-TAL1 deletions at presentation and relapse but exact breakpoints differed, indicating independent genomic events. Similarly, 1 case carried alternative LMO2 translocations at presentation and relapse.

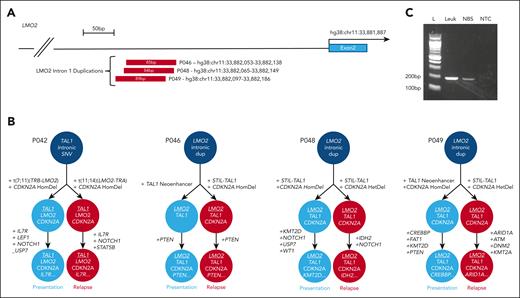

In light of recent publications detailing recurrent noncoding lesions in T-ALL affecting TAL113-15 and LMO2,16 we explored noncoding mutations in these regions. These mutations have previously been functionally validated as driver mutations, typically introducing binding sites for MYB that lead to aberrant enhancer or promoter formation, activating TAL1 or LMO2 expression, respectively.13,14,16,17 Both cases with relapse-specific STIL-TAL1 deletions were found to carry the previously reported intergenic TAL1 neo-enhancer insertion at presentation,13 demonstrating independent convergent genetic evolution of alternative TAL1-activating lesions. Unexpectedly, 4 patients retained the same somatic noncoding variant between presentation and relapse. Patient P042 had an identical TAL1 intron 1 SNV in both leukemias. This lesion has been previously reported but is rare,14 strongly suggesting it is the founder event in a preleukemic clone. Remarkably, a further 3 cases carried LMO2 intron 1 duplications at both presentation and relapse (Figure 1A). These lesions have also been previously reported occurring in 3.7% of childhood cases of T-ALL and resulting in LMO2 overexpression.16 In each case, breakpoints at presentation and relapse were identical, thereby confirming the LMO2 duplication as the leukemia-initiating event and unequivocally linking the presentation and relapse leukemias.

Noncoding lesions unite initial diagnostic and late relapse leukemias. (A) Schematic representation of LMO2 intron 1 duplications identified in 3 cases. (B) Order of acquisition of mutations in initial diagnostic and relapse cases, demonstrating the initiating noncoding lesion that unites the 2 leukemias. (C) Agarose gel of polymerase chain reaction products confirming presence of the noncoding LMO2 duplication in the neonatal blood spot sample from patient P049. Polymerase chain reaction product was confirmed on Sanger sequencing. Lane M, 100-bp molecular weight ladder; lane 1, P049 presentation sample DNA; lane 2, P049 neonatal blood spot DNA; lane 3, no template (water) control. dup, duplication; HomDel, homozygous deletion; L, ladder; Leuk, leukemia; NBS, neonatal blood spot; NTC, nontemplate control.

Noncoding lesions unite initial diagnostic and late relapse leukemias. (A) Schematic representation of LMO2 intron 1 duplications identified in 3 cases. (B) Order of acquisition of mutations in initial diagnostic and relapse cases, demonstrating the initiating noncoding lesion that unites the 2 leukemias. (C) Agarose gel of polymerase chain reaction products confirming presence of the noncoding LMO2 duplication in the neonatal blood spot sample from patient P049. Polymerase chain reaction product was confirmed on Sanger sequencing. Lane M, 100-bp molecular weight ladder; lane 1, P049 presentation sample DNA; lane 2, P049 neonatal blood spot DNA; lane 3, no template (water) control. dup, duplication; HomDel, homozygous deletion; L, ladder; Leuk, leukemia; NBS, neonatal blood spot; NTC, nontemplate control.

Overall, 4 of 7 cases were linked by a single noncoding lesion, while all other coding mutations differed, implicating the noncoding lesion as the founder event in a preleukemic subclone. Despite successful treatment of the initial leukemia, the preleukemic clone evaded chemotherapy, and reevolved to a second leukemia. Although half of T-ALL relapses evolve from a minor subclone present at presentation (“type 2 relapses”), those cases share several driver mutations between presentation and relapse. In contrast, our cases present a unique phenomenon in T-ALL, with presentation and relapse sharing a single driver, reminiscent of late relapse in ETV6-RUNX1 B-ALL.18,19 It could therefore be suggested that they are essentially 2 separate leukemias that evolved from the same founder clone with the second leukemia masquerading as relapse. This is supported by the absence of NT5C2 mutations at relapse in our cohort, which occur in up to 35% of relapses.3,9,20

The inferred order of mutation acquisition is displayed for each case in Figure 1B showing for the first time that both TAL1 and LMO2 can act interchangeably as the leukemia-initiating event and are highly synergistic. P042 first acquired a TAL1 lesion and went on to develop alternative LMO2 translocations in each leukemia, while the 3 patients carrying initial LMO2 duplications developed TAL1-activating lesions in all leukemias, demonstrating a strong selective pressure. Understanding the mechanisms by which noncoding lesions predispose to late relapse requires further work.

We next sought to estimate timing of the initiating noncoding lesion. Given the linear accumulation of somatic mutations with age, the fewer mutations shared between the 2 leukemias, the earlier in development the lesion occurred.21 The 3 cases with a shared noncoding lesion and germ line tissue shared only 20 to 40 somatic variants between presentation and relapse, suggesting the noncoding lesion occurred early in development, potentially in utero. To investigate this, we tested for the mutation in a stored neonatal blood spot from patient P049. This confirmed presence of the LMO2 duplication in the blood spot DNA, definitively establishing an in utero origin (Figure 1C).

Three cases remained unexplained with no evidence of shared lesions at diagnosis and relapse, raising the possibility of a genetic predisposition. Of these cases, patient P047 had a very high somatic mutational burden and was confirmed to have constitutional mismatch repair deficiency secondary to homozygous PMS2 mutations,22 highlighting the need to screen similar patients. Despite extensive profiling of germ line mutations, we were unable to identify causative mutations in the final 2 cases. Both cases also lacked a clear initiating somatic lesion, raising the possibility that they are linked by an as yet undiscovered noncoding lesion.

In summary, we have shown that late relapse in T-ALL can evolve from a preleukemic founder clone present in utero. Our study positions noncoding driver mutations of TAL1 and LMO2 as the earliest founder events in disease pathogenesis, occurring in a precursor cell that has not yet undergone TCR rearrangement. It also demonstrates parallel evolution of dual TAL1 and LMO lesions, highlighting the cooperative oncogenicity suggested from murine studies.23 Although larger studies are required to inform the optimal management of such patients, our data suggest patients with late relapse have disease distinct from their original T-ALL, lack chemotherapy resistance mutations, and could potentially be treated with reinduction chemotherapy rather than intensification or transplant. However, this could allow persistence of the preleukemic clone and the risk of a subsequent relapse remains unknown.

Samples were provided by the VIVO Biobank (as approved by the South West–Central Bristol Research Ethics Committee, reference 16SW0219) and the Great Ormond Street Haematology Cell Bank (as approved by the National Research Ethics Service Committee London Brent, reference 16/LO/0960). Informed consent was provided by all patients or guardians.

Acknowledgments

D.O. is funded by a Cancer Research UK Clinician Scientist Fellowship (A27177). M.R.M. is funded by the Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity, Cancer Research UK and the Alviar Cohen Research Fund. L.C. was funded by the Cancer Research UK-University College London (CRUK-UCL) Centre Award [C416/A25145]. J.R.C. is supported by the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Research Fund and Cancer Research UK. J.E.V.-I., H.E. and I.C.-C. thank European Molecular Biology Laboratory for funding. A.V.M. received funding from Blood Cancer UK (15036). Additional funding for sequencing was provided by the Olivia Hodson Cancer Fund. Samples and data used in this study were provided by VIVO Biobank, supported by Cancer Research UK and Blood Cancer UK (grant no. CRCPSC-Dec21\100003).

Authorship

Contribution: D.O. conceived the study, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; G.B., S.R., J.R.C., J.B., S.A., and G.W. performed experiments and analyzed data; J.E.V.-I., H.E., I.C.-C., L.C., J.H., and M.R.M. analyzed data; A.V.M. conceived the study and provided samples; K.W., S.D., C.H., and G.J. provided samples; and all authors revised the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David O’Connor, Department of Haematology, UCL Cancer Institute, University College London, London WC1E 6DD, United Kingdom; email: david.oconnor@ucl.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

The data have been submitted to the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA) with Accession ID (EGAS50000000129).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal