Visual Abstract

TO THE EDITOR:

Ineffective erythropoiesis and chronic anemia are the hallmarks of disease in β-thalassemia.1 Patients presenting with severe anemia and symptoms or those later manifesting poor growth or development or increased morbidity are often maintained on regular transfusion therapy and classified as having transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (TDT).2 Target pretransfusion hemoglobin ranges of 9 to 10 g/dL, 9 to 10.5 g/dL, and 9.5 to 10.5 g/dL have been recommended by various international management guidelines over the past few decades to inform transfusion frequency.3,4 These ranges have been mainly set by expert opinion, primarily relying on data highlighting the relationship between pretransfusion hemoglobin levels and suppression of erythropoiesis.5 Studies on the association between pretransfusion hemoglobin level and long-term mortality in TDT are lacking. Moreover, recent data from patients with non-transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia highlighted a significant association between a hemoglobin level <10 g/dL and variations as small as 1 g/dL with increased mortality risk,6 further suggesting a need to revisit thresholds used in patients with TDT. In this work, we evaluate the association between pretransfusion hemoglobin level and mortality in a large cohort of patients with TDT followed for 10 years.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients with β-thalassemia attending 5 treatment centers in Italy that use Webthal, a computerized medical record software developed in 2000 to aid in standardized clinical, laboratory, and imaging data recording across participating centers. Ethics Committee approval was obtained, and written informed consent for data collection and use was obtained from patients at each center. For this study, we retrieved data for all adults with transfusion-dependent (average of at least 10 red blood cell units per year during the observation period) β-thalassemia major (≥18 years) who were being followed at the centers from 1 January 2010 until 31 December 2019, death, transplant, or loss to follow-up—to reflect a contemporary 10-year observation period prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Two patients who had been receiving luspatercept therapy were excluded. For each patient, we retrieved data on age at study start, sex, 10-year observation period average for pretransfusion hemoglobin level (median number of records available per individual year ranged between 17 and 18, minimum: 1, maximum: 37), and serum ferritin level (median number of records available per individual year ranged between 6 and 8, minimum: 1, maximum: 26), and presence of active morbidities at study start including cardiovascular disease, hepatic disease, or diabetes.

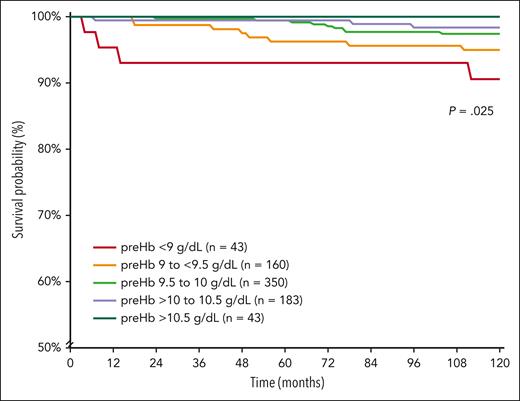

A total of 779 patients with TDT were included in this analysis, with 399 (51.2%) female patients. The median age at study start was 33.1 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 28.4-36.8, minimum: 18.1, maximum: 61). A total of 309 (39.7%) patients were splenectomized, and active morbidity was present in 166 (21.3%) patients at study start. Over the 10-year observation period, the median serum ferritin level was 1195.3 ng/mL (IQR: 626.2-2116, minimum: 99, maximum 15 101.3) and median pretransfusion hemoglobin level was 9.7 g/dL (IQR: 9.5-10.1, minimum: 7.5, maximum 11.8). The median standard deviation of individual patients’ pretransfusion hemoglobin levels was 0.17 g/dL, indicating relative stability over time. Patients were further categorized into pretransfusion hemoglobin levels of <9 g/dL (n = 43), 9 to <9.5 g/dL (n = 160), 9.5 to 10 g/dL (n = 350), >10 to 10.5 g/dL (n = 183), and >10.5 g/dL (n = 43) in alignment with currently used ranges and the minor differences between them. All patients were followed for the full 10 years, except for 16 patients who were lost to follow-up or transferred, 2 patients who died due to accidents, and 24 (3.1%) patients who died due to thalassemia (cardiovascular disease, n = 17; hepatic disease, n = 3 [including 2 with hepatocellular carcinoma]; other renal or systemic disease, n = 4). There was a significant and steady decrease in thalassemia-related mortality rate (9.3% to 0%, P = .033), and there was prolonged survival (5-year survival 93% and 10-year survival 91%-100% for both, P = .025) with ascending pretransfusion hemoglobin level categories (Table 1 and Figure 1). We also conducted a receiver operating characteristic curve analysis for the prediction of thalassemia-related mortality by pretransfusion hemoglobin level used as a continuous variable (area under the curve: 0.667 ± 0.060; P = .005), and a threshold of <9.3 g/dL was the best predictor using the Youden Index (specificity + specificity − 1). When data were stratified by sex, the best predictor was a pretransfusion hemoglobin level of <9.1 g/dL in female patients and <9.3 g/dL in male patients.

Survival and hazard ratios for thalassemia-related mortality according to pretransfusion hemoglobin level

| Pretransfusion hemoglobin, g/dL∗ . | Deaths n (%) . | Pearson’s χ2 (P value) . | 5-year survival (%) . | 10-year survival (%) . | Log-rank χ2 (P value) . | Unadjusted HR . | 95% CI (P value) . | Adjusted HR† . | 95% CI (P value) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <9 (n = 43) | 4 (9.3) | 10.492 (.033) | 93 | 91 | 11.370 (.025) | 1.00 (referent) | — | 1.00 (referent) | — |

| 9 to <9.5 (n = 160) | 8 (5.0) | 96 | 95 | 0.506 | 0.162-1.681 (0.266) | 0.563 | 0.165-1.919 (.358) | ||

| 9.5 to 10 (n = 350) | 9 (2.6) | 99 | 97 | 0.256 | 0.079-0.830 (0.023) | 0.248 | 0.074-0.832 (.024) | ||

| >10 to 10.5 (n = 183) | 3 (1.6) | 99 | 98 | 0.162 | 0.036-0.724 (0.017) | 0.125 | 0.027-0.574 (.008) | ||

| ≥10.5 (n = 43) | 0 (0.0) | 100 | 100 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Pretransfusion hemoglobin, g/dL∗ . | Deaths n (%) . | Pearson’s χ2 (P value) . | 5-year survival (%) . | 10-year survival (%) . | Log-rank χ2 (P value) . | Unadjusted HR . | 95% CI (P value) . | Adjusted HR† . | 95% CI (P value) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <9 (n = 43) | 4 (9.3) | 10.492 (.033) | 93 | 91 | 11.370 (.025) | 1.00 (referent) | — | 1.00 (referent) | — |

| 9 to <9.5 (n = 160) | 8 (5.0) | 96 | 95 | 0.506 | 0.162-1.681 (0.266) | 0.563 | 0.165-1.919 (.358) | ||

| 9.5 to 10 (n = 350) | 9 (2.6) | 99 | 97 | 0.256 | 0.079-0.830 (0.023) | 0.248 | 0.074-0.832 (.024) | ||

| >10 to 10.5 (n = 183) | 3 (1.6) | 99 | 98 | 0.162 | 0.036-0.724 (0.017) | 0.125 | 0.027-0.574 (.008) | ||

| ≥10.5 (n = 43) | 0 (0.0) | 100 | 100 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

Values in boldface indicate P < .05. NC, noncalculable.

Ten-year observation period average.

Adjusted for age at study start, center, sex, presence of active morbidity at baseline in a multivariate forward stepwise Cox regression model.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for thalassemia-related mortality according to pretransfusion hemoglobin level. preHb, pretransfusion hemoglobin.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for thalassemia-related mortality according to pretransfusion hemoglobin level. preHb, pretransfusion hemoglobin.

We constructed a multivariate Cox regression model with the outcome of thalassemia-related mortality as the dependent variable and pretransfusion hemoglobin level categories as independent variables. Unadjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are summarized in Table 1, which indicated an incremental protective effect of ascending pretransfusion hemoglobin level categories compared with a pretransfusion hemoglobin level <9 g/dL, with significant associations noted with levels >9.5 g/dL. We further adjusted the associations for potential confounders that may be linked to certain pretransfusion hemoglobin levels and reflect increased mortality risk including age, sex, center of treatment, splenectomy, and active morbidity at study start. Results remained largely unchanged (Table 1) with adjusted HR of 0.563 (95% CI: 0.165-1.919, P = .358) for pretransfusion hemoglobin levels 9 to <9.5 g/dL, 0.248 (95% CI: 0.074-0.832, P = .024) for levels 9.5 to 10 g/dL, 0.125 (95% CI: 0.027-0.574, P = .008) for levels >10 to 10.5 g/dL, while they could not be computed for levels >10.5 g/dL owing to 0 deaths. When the analysis was stratified by serum ferritin level (observation period average) of >1000 ng/mL (17/446 deaths, 3.8%) and ≤1000 ng/mL (7/333 deaths, 2.1%), the association between pretransfusion hemoglobin level categories and thalassemia-related mortality was only significant for patients with serum ferritin ≤1000 ng/mL.

With this work, we have established an association between higher pretransfusion hemoglobin levels and lower thalassemia-related mortality in adults with TDT. This association seems to begin with levels at or exceeding 9.5 g/dL, and protective effects are incremental with higher levels. Thus, the newly proposed pretransfusion hemoglobin target range of 9.5 to 10.5 g/dL in the 2021 version of the Thalassaemia International Federation guidelines (compared with 9-10.5 g/dL in previous editions)4 seems reasonable, although targeting levels >10.5 g/dL could be argued if blood product availability and convenience of transfusion interval and frequencies allow. Geographical variations in transfusion practices and pretransfusion hemoglobin levels are primarily driven by blood product availability.7 In our cohort, these may be further attributed to patient and physician preferences, adherence to transfusion visits, or presence of comorbidities that necessitated alterations (upward or downward) in transfusion regimens (eg, severe iron overload, heart disease, hypersplenism, alloimmunization). Future studies could evaluate specific associations between various transfusion patterns and outcomes in patients with TDT. Our results are also in alignment with recent evidence linking hemoglobin levels >10 g/dL with improved survival in patients with non-transfusion-dependent thalassemia, further supporting the role of controlling ineffective erythropoiesis in improving outcomes.6

The loss of protective effects in patients with uncontrolled iron overload (serum ferritin level >1000 ng/mL) reflects the importance of adequate iron chelation therapy in maintaining the benefit of ameliorating anemia with transfusions without the added harm of transfusional siderosis. Lastly, the use of evidence-based target pretransfusion hemoglobin levels is now becoming more important, considering the availability of several novel therapies aiming to reduce transfusion burden while maintaining adequate and “safe” hemoglobin levels in the adult patient population. The latter remains highly relevant in regions where blood shortage does not allow any further optimization of pretransfusion hemoglobin levels.

Authorship

Contribution: Study conception and design: K.M.M., G.L.F.; data collection: S.B., R.O., G.B.F., R.L., A.P., F.L., B.G., G.L.F.; statistical analysis: K.M.M.; review and interpretation of results: all authors; manuscript drafting: K.M.M.; manuscript review for important intellectual content: all authors; and all authors approved the manuscript before submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.M.M. reports consultancy fees from Novartis, Celgene Corp (Bristol Myers Squibb), Agios Pharmaceuticals, CRISPR Therapeutics, Vifor Pharma, and Pharmacosmos; and research funding from Agios Pharmaceuticals and Pharmacosmos. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the Webthal project appears in “Appendix.”

Correspondence: Gian Luca Forni, Center for Microcythemia, Congenital Anemia and Iron Dysmetabolism Galliera Hospital, Via Volta 6, 16128 Genoa, Italy; email: gianlucaforni14@gmail.com.

Appendix: study group members

Members of the Webthal project include the authors as well as Valeria Pinto (Galliera Hospital, Genoa, Italy), Roberta Sciortino (ARNAS Garibaldi, Catania, Italy), Domenico Roberti (Università Vanvitelli, Naples, Italy), Lucia De Franceschi (Università di Verona AOIU, Verona, Italy), and Martina Culcasi (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria S. Anna, Ferrara, Italy).

References

Author notes

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author, Gian Luca Forni (gianlucaforni14@gmail.com).

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal