Antibody-mediated CSF1R inhibition is associated with neurological toxicity during acute and chronic CNS GVHD.

Targeting donor IFNGR signaling is a promising therapeutic strategy for ameliorating cGVHD of the CNS.

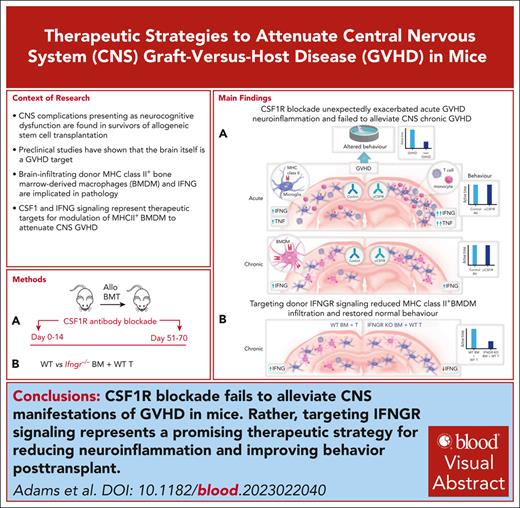

Visual Abstract

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) remains a significant complication of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement is becoming increasingly recognized, in which brain-infiltrating donor major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II+ bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDM) drive pathology. BMDM are also mediators of cutaneous and pulmonary cGVHD, and clinical trials assessing the efficacy of antibody blockade of colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) to deplete macrophages are promising. We hypothesized that CSF1R antibody blockade may also be a useful strategy to prevent/treat CNS cGVHD. Increased blood-brain barrier permeability during acute GVHD (aGVHD) facilitated CNS antibody access and microglia depletion by anti-CSF1R treatment. However, CSF1R blockade early after transplant unexpectedly exacerbated aGVHD neuroinflammation. In established cGVHD, vascular changes and anti-CSF1R efficacy were more limited. Anti-CSF1R–treated mice retained donor BMDM, activated microglia, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, and local cytokine expression in the brain. These findings were recapitulated in GVHD recipients, in which CSF1R was conditionally depleted in donor CX3CR1+ BMDM. Notably, inhibition of CSF1R signaling after transplant failed to reverse GVHD-induced behavioral changes. Moreover, we observed aberrant behavior in non-GVHD control recipients administered anti-CSF1R blocking antibody and naïve mice lacking CSF1R in CX3CR1+ cells, revealing a novel role for homeostatic microglia and indicating that ongoing clinical trials of CSF1R inhibition should assess neurological adverse events in patients. In contrast, transfer of Ifngr–/– grafts could reduce MHC class II+ BMDM infiltration, resulting in improved neurocognitive function. Our findings highlight unexpected neurological immune toxicity during CSF1R blockade and provide alternative targets for the treatment of cGVHD within the CNS.

Introduction

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) remains the primary cause of late morbidity and mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT).1 Complex pathophysiology underlies heterogeneous manifestations of cGVHD in multiple organ systems.2,3 Central nervous system (CNS) complications presenting as neurocognitive dysfunction are reported in up to 60% of adult allo-HSCT survivors.4-6 In these patients, neurological impacts are underpinned by multiple factors including malignant disease, pretransplant conditioning, immunosuppressive therapies, and cGVHD itself.7 Preclinical studies have confirmed the brain itself as a GVHD target and have identified novel immune mechanisms mediating neuroinflammation during cGVHD, which are distinct from those driving CNS acute GVHD (aGVHD).8,9 Altered behavior in cGVHD is associated with CNS entry of donor MHC class II+ bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDM) and CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, with a proinflammatory milieu of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) production.9 Recently, CNS engraftment of donor BMDM has been confirmed in cortical samples from allo-HSCT patients.10 Corticosteroids remain the only treatment strategy for cGVHD neurological complications.

Tissue-resident macrophages, including CNS microglia, are dependent on colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) and its cognate ligand, CSF1, for survival.11 In cutaneous cGVHD, pathogenic skin-infiltrating donor-derived macrophages cause scleroderma, which could be prevented by anti-CSF1R monoclonal antibody (mAb) treatment or transfer of Csf1r–/– allografts.12 Clinical trials to assess the safety and efficacy of antibody-mediated CSF1R blockade have recently been initiated and show promising results for patients with fibrotic manifestations.13 Having also identified pathogenic donor BMDM in the cGVHD brain, we examined the utility of CSF1R blockade for treating CNS manifestations. Importantly, the timing of our report is pertinent given the unknown CNS effects of peripheral macrophage depletion during cGVHD.

Inefficient delivery of therapeutics to the brain can preclude successful treatment of neurological disorders, often due to exclusion by the blood-brain barrier (BBB).14 Indeed in naïve mice, anti-CSF1R treatment had no effect on macrophage populations in the meninges, choroid plexus, or parenchymal microglia, likely as a function of an intact BBB.15 However, the BBB is commonly disrupted in CNS disease,16-18 whereby a feature of damage is immune cell infiltration, which has already been reported in both acute8 and chronic9 GVHD preclinical models and patients.19-22 Here, we report spatiotemporal perturbations to the BBB after transplant, with implications for therapeutic access to the brain. Anti-CSF1R antibody treatment accessed the brain but exacerbated CNS aGVHD and demonstrated no therapeutic efficacy in improving CNS cGVHD, revealing unexpected neurological toxicity in response to this systemic therapy. In contrast, modulating MHC class II+ donor BMDM via the interferon gamma receptor (IFNGR) could attenuate CNS cGVHD and improve behavior. This study indicates the potential for differential effects of GVHD therapies across target organs and highlights the need for tissue-specific targeted therapies.

Methods

Mice

Female mice aged 8 to 12 weeks were used for all transplants. Strains used are listed in supplemental Table 1. Naïve CX3CR1cre × CSF1Rfl/fl male mice were used for model characterization. Mice were housed in sterilized microisolator cages on a 12:12 hour light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the QIMR Berghofer Animal Ethics Committee.

BM transplantation

Recipients received 1100 (B6D2F1) or 1000 (C57BL/6) centi-gray (cGy) split-dose total body irradiation (cesium 137 source) on day 0. Grafts were resuspended in Leibovitz medium and delivered via IV tail vein injection, composed of 5 × 106 C57BL/6 (for B6D2F1) or 10 × 106 BALB/c (for C57BL/6) T-cell–depleted (TCD) bone marrow (BM) alone (non-GVHD controls), or with 0.5 × 106 C57BL/6 (for B6D2F1) or 5 × 106 BALB/c (for C57BL/6) splenic T cells enriched by BioMag (Qiagen) bead depletion of non-T cells to induce GVHD.23 Mice were monitored daily and received clinical scores in accordance with previously published criteria.24

Tissue procurement

Peripheral blood was obtained by retro-orbital or submandibular bleeds into EDTA-coated tubes before euthanization. Mice were then anesthetized with ketamine (40 mg/mL)/xylazine (2 mg/mL) for transcardial perfusion with 20 mL cold 1× phosphate-buffered saline. Hair was removed at the nape, and skin was dissected for histology. Brains were extracted, and the olfactory bulbs and cerebellum were removed before dissection down the midline. Each hemisphere was then subjected to one of the following: brain digestion (collagenase IV/DNAse I), snap freezing in liquid nitrogen for RNA isolation, or drop-fixation in buffered formalin for immunofluorescence.

snRNA-seq

Single nuclei RNA-sequencing (snRNA-seq) was performed on 50 mg pieces of tissue obtained from recipient brains. Nuclei were isolated using the 10× Genomics Chromium Nuclei Isolation Kit and further sort-purified as DAPI+ on a BD FACS Aria II. Samples were prepared using the Chromium next GEM Single Cell 3’ Reagent Kit (v3.1, 10× Genomics) and Chromium Controller (10× Genomics) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Single nuclei libraries were sequenced using the NovaSeq 6000 Sequencing System (Illumina). Data were processed using Cell Ranger v6.0.1, and all downstream analysis was performed in R (v4.2.0) using Seurat (v.4.3.0).

snRNA-seq data are accessible through NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus database (GSE245360).

Statistics

GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0.1) was used for all statistical analyses. Normality was determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed data were tested with unpaired 2-tailed Student t test or 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey multiple comparisons test for 2 or 3 groups, respectively. Mann-Whitney nonparametric t test or Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test was used for the comparison of 2 or 3 groups, respectively, for data that did not demonstrate normal distribution. Clinical scores were assessed with a 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons. Differences were considered significant if P < .05.

All other methods can be found in supplemental Materials and methods, available on the Blood website.

Results

GVHD is associated with spatiotemporal perturbations to cellular and vascular components of the BBB

To investigate the effects of GVHD on the BBB beyond conditioning, we assessed components of the neurovascular unit in brains from lethally irradiated B6.CSF1r-eGFP×DBA2 F1 mice that received MHC-mismatched BM with T cells from a C57BL/6 donor to induce GVHD, compared with non-GVHD controls receiving TCD grafts (supplemental Figure 1A). In these recipients, eGFP driven off the Csf1r promoter facilitates identification of host microglia in the brain.25 We previously observed altered behavior in this model at day 14,8 but CNS pathology was not examined at this time point. We confirmed the development of CNS aGVHD features at day 14, including local brain upregulation of Tnf and host microglia MHC class II expression in the hippocampus and cortex (supplemental Figure 1B-D). As we anticipated transient damage to the BBB early after transplant in response to irradiation and cytokine dysregulation, we performed assessments at both day 14 (aGVHD) and day 70 (cGVHD). As a key cellular component of the BBB, we examined astrocyte activation, which is associated with microglia reactivity and inflammatory monocyte infiltration.26 On day 14, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)+ cell density in aGVHD in the hippocampus was significantly increased compared with TCD controls (Figure 1A), as were levels of Gfap messenger RNA (Figure 1B); both reduced to TCD control levels by day 70 (Figure 1C-D). Consistent with immune cell infiltration during aGVHD, we observed upregulation of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1) in the hippocampus and cortex of GVHD mice at day 14 (Figure 1E-F), which had also subsided by day 70 (Figure 1G-H). This was associated with a modest increase in endothelial (CD31+) cells in both the hippocampus and cortex of aGVHD brains at day 14 (Figure 1I-J). This declined in the hippocampus by day 70 (Figure 1K) but remained elevated in the cortex as measured by increased area coverage and fluorescence intensity (Figure 1L). Endothelial damage and neovascularization are features of GVHD, and vasculitis/angiitis is reported in CNS cGVHD.21,27 Such vascular aberrations can be induced by various factors including VEGF-A.28 We confirmed upregulation of Vegfa in the CNS during cGVHD onset at day 35 (supplemental Figure 2A), which may prompt endothelial proliferation leading to the observed increase in CD31 expression. Other parameters of BBB structure were unchanged, including the expression of the basement membrane component collagen IV (supplemental Figure 2B-E) and the messenger RNA expression of tight junction proteins Cldn5, Zo1, and Ocln (supplemental Figure 2F-G). These data suggest more profound changes to the BBB early after transplant during active inflammation, while cGVHD maintains subtle vascular changes. These findings have implications for informing the potential for drug access to the brain at varying times after transplant.

Characterization of the BBB during GVHD. Lethally irradiated B6.Csf1r-eGFP × DBA2xF1 or B6D2D1 mice received 5 × 106 TCD BM with or without 0.5 × 106 enriched splenic T cells on day 0. Brains were subsequently assessed at day 14 or day 70 after transplant. (A) Representative confocal images of hippocampal astrocytes and quantification of GFAP+ stained area as a percentage of total image area at day 14 after transplant; n = 4 to 7 mice per group; data pooled from 3 independent experiments. (B) mRNA expression of Gfap detected by qRT-PCR at day 14 after transplant; n = 6 mice per group; data representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) Representative confocal images of hippocampal astrocytes and quantification of GFAP stained area as a percentage of total image area at day 70 after transplant; n = 9 to 17 mice per group; data pooled from 3 independent experiments. (D) mRNA expression of Gfap detected by qRT-PCR at day 70 after transplant; n = 4 mice per group; data representative of 2 independent transplants. (E-H) Representative confocal images of VCAM1 expression: (E) hippocampus at day 14, (F) cortex at day 14, (G) hippocampus at day 70, and (H) cortex at day 70. Quantification of VCAM1+ stained area represented as a percentage of total image area is shown. White arrows indicate positive staining; day 14, n = 7 to 9 mice per group; data pooled from 3 independent experiments; day 70, n = 5 to 6 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (I-L) Representative confocal images of CD31 expression: (I) hippocampus at day 14, (J) cortex at day 14, (K) hippocampus at day 14, (L) cortex at day 70. Quantification of CD31+ stained area represented as a percentage of total image area and quantification of total CD31 fluorescence intensity (arbitrary fluorescence units [AFU]) are shown; day 14, n = 4 to 8 mice per group; data pooled from 3 independent experiments; day 70, n = 4 to 5 mice per group; data from 1 experiment. (A,C,E-H,I-L) Original magnification ×20; scale bar, 50 μm. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI in all images. Significant differences calculated with Mann-Whitney unpaired nonparametric t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; mRNA, messenger RNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Characterization of the BBB during GVHD. Lethally irradiated B6.Csf1r-eGFP × DBA2xF1 or B6D2D1 mice received 5 × 106 TCD BM with or without 0.5 × 106 enriched splenic T cells on day 0. Brains were subsequently assessed at day 14 or day 70 after transplant. (A) Representative confocal images of hippocampal astrocytes and quantification of GFAP+ stained area as a percentage of total image area at day 14 after transplant; n = 4 to 7 mice per group; data pooled from 3 independent experiments. (B) mRNA expression of Gfap detected by qRT-PCR at day 14 after transplant; n = 6 mice per group; data representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) Representative confocal images of hippocampal astrocytes and quantification of GFAP stained area as a percentage of total image area at day 70 after transplant; n = 9 to 17 mice per group; data pooled from 3 independent experiments. (D) mRNA expression of Gfap detected by qRT-PCR at day 70 after transplant; n = 4 mice per group; data representative of 2 independent transplants. (E-H) Representative confocal images of VCAM1 expression: (E) hippocampus at day 14, (F) cortex at day 14, (G) hippocampus at day 70, and (H) cortex at day 70. Quantification of VCAM1+ stained area represented as a percentage of total image area is shown. White arrows indicate positive staining; day 14, n = 7 to 9 mice per group; data pooled from 3 independent experiments; day 70, n = 5 to 6 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (I-L) Representative confocal images of CD31 expression: (I) hippocampus at day 14, (J) cortex at day 14, (K) hippocampus at day 14, (L) cortex at day 70. Quantification of CD31+ stained area represented as a percentage of total image area and quantification of total CD31 fluorescence intensity (arbitrary fluorescence units [AFU]) are shown; day 14, n = 4 to 8 mice per group; data pooled from 3 independent experiments; day 70, n = 4 to 5 mice per group; data from 1 experiment. (A,C,E-H,I-L) Original magnification ×20; scale bar, 50 μm. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI in all images. Significant differences calculated with Mann-Whitney unpaired nonparametric t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; mRNA, messenger RNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Anti-CSF1R mAb accesses the brain during aGVHD but fails to attenuate neuroinflammation or restore behavior

Next, we examined whether an anti-CSF1R mAb (M279) could enter the CNS and deplete microglia/macrophages in the brain in the BALB/c into C57BL/6 aGVHD model, in which CNS pathology is dependent on host microglia-derived tumor necrosis factor (TNF).8 Recipients were administered M279 or isotype control (iso) mAb from days 0 to 14, after which we confirmed the presence of both mAbs in the brain (supplemental Figure 3A). Analysis of peripheral blood from GVHD mice treated with M279 (GVHD + M279) confirmed the maintenance of Ly6ChiMHC II+ monocytes, which are activated during aGVHD, and specific depletion of CSF1R-dependent Ly6CloMHC II+ monocytes (supplemental Figure 3B-D), as reported previously.15 Analysis at day 14 revealed that M279 induced a significant but incomplete depletion of CD45dimCD11b+HD2d– host microglia in GVHD but more extensive depletion in TCD animals (Figure 2A, supplemental Figure 3E), indicating that, and in line with observed antibody in TCD brains, conditioning alone is sufficient to allow antibody access. Residual microglia in the brains of M279-treated GVHD mice, but not TCD animals, exhibited upregulation of MHC class II, indicating increased activation (Figure 2B). M279 increased brain Ly6ChiMHC II+ inflammatory monocytes, CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell infiltrates, and local Tnf, Ccl2, and Ifng expression (Figure 2C-F). Although M279 administration did increase intestinal pathology as previously observed in aGVHD models,15,29 injury remained mild, and CSF1R inhibition had no significant effects on clinical scores or circulating TNF or IFNG levels at day 14 (supplemental 4A-C). Given the marked increases in Tnf and Ifng expression and enhanced inflammatory infiltrate within the brain, taken together, the data support local effects of CSF1R blockade driving neuroinflammation. Moreover, behavior of GVHD + M279 mice was unchanged compared with GVHD + iso mAb animals, with both groups performing significantly worse than TCD + iso mAb controls in the forced swim test (FST) (Figure 2G).

CSF1R blockade exacerbates aGVHD. Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 recipients underwent transplantation with 10×106 TCD BM cells with or without 5 × 106 CD3+ T cells from BALB/c donors. M279 or isotype control antibody was administered from days 0 to 14. Mice were euthanized on day 14 after transplant for assessment of the brain. (A) Absolute number of host microglia (CD45dimCD11b+H2Dd–) in brains of recipients at day 14 after transplant within the live (SytoxBlueneg) Ly6Gneg population; n = 7 to 8 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (B) MHC class II expression (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]) on host microglia at day 14 after transplant; n = 7 to 8 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (C) Absolute number of Ly6ChiMHC II+ intermediate inflammatory monocytes within the live CD45hiCD11b+ population in the brains of transplant recipients at day 14 after transplant; n = 3 to 4 mice per group, representative of 2 independent experiment. (D) Absolute number of CD8+ T cells in the brain at day 14 after transplant, within the live CD45+CD11b–CD3+ population; n = 7 to 8 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (E) Absolute number of CD4+ T cells in the brain at day 14 after transplant, within the live CD45+CD11b–CD3+ population; n = 7 to 8 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (F) mRNA expression of Tnf, Ccl2, and Ifng in the brain at day 14 after transplant as detected by qRT-PCR; n = 4 to 12 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (G) Time recipients spent mobile in the FST, out of a total time of 180 seconds, at day 14 after transplant; n = 5 to 12 mice per group; data pooled from 3 independent experiments. (H) Representative confocal images of IBA1+ microglia in the hippocampus ([left panel] original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm) of naïve CX3CR1cre × CSF1Rflfl mice. Higher magnification illustrates altered morphology ([right panel] original magnification, ×100; scale bar, 10 μm). Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (I) Quantification of IBA1+ cells in the hippocampus. (J) Violin plot showing the quantification of the size of IBA1+ cells in the hippocampus from 3 mice per group, expressed as pixels squared. Bold line represents the median. (K) Representative confocal images of IBA1+ microglia in the cortex ([left panel] original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm) of naïve CX3CR1cre × CSF1Rflfl mice. Higher magnification illustrates altered morphology ([right panel] original magnification, ×100; scale bar, 10 μm). Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (L) Quantification of IBA1+ cells in the cortex. (M) Violin plot showing the quantification of the size of IBA1+ cells in the cortex from 3 mice per group, expressed as pixels squared. Bold line represents the median. (N) mRNA expression of Sall1, Tnf, and Ccl12 in the brain as detected by qRT-PCR. (O) Time naïve CX3CR1cre × CSF1Rwt/wt and CX3CR1cre × CSF1Rflfl mice spent mobile in the FST out of a total time of 180 seconds. Statistics calculated by: (A-E) ordinary 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test; (F) Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric 1-way ANOVA with Dunn multiple comparisons test on ΔCT values; (G) ordinary 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test (GVHD + iso mAb vs GVHD + M279 vs TCD + iso mAb) and Student unpaired t test (TCD + iso mAb vs TCD + M279); (M-N) Mann-Whitney nonparametric t test (comparisons performed on ΔCT values for qRT-PCR data); (O) Student unpaired t test. Data presented as mean ± SEM, except for (J,M) presented as median. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; mRNA, messenger RNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean.

CSF1R blockade exacerbates aGVHD. Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 recipients underwent transplantation with 10×106 TCD BM cells with or without 5 × 106 CD3+ T cells from BALB/c donors. M279 or isotype control antibody was administered from days 0 to 14. Mice were euthanized on day 14 after transplant for assessment of the brain. (A) Absolute number of host microglia (CD45dimCD11b+H2Dd–) in brains of recipients at day 14 after transplant within the live (SytoxBlueneg) Ly6Gneg population; n = 7 to 8 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (B) MHC class II expression (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]) on host microglia at day 14 after transplant; n = 7 to 8 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (C) Absolute number of Ly6ChiMHC II+ intermediate inflammatory monocytes within the live CD45hiCD11b+ population in the brains of transplant recipients at day 14 after transplant; n = 3 to 4 mice per group, representative of 2 independent experiment. (D) Absolute number of CD8+ T cells in the brain at day 14 after transplant, within the live CD45+CD11b–CD3+ population; n = 7 to 8 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (E) Absolute number of CD4+ T cells in the brain at day 14 after transplant, within the live CD45+CD11b–CD3+ population; n = 7 to 8 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (F) mRNA expression of Tnf, Ccl2, and Ifng in the brain at day 14 after transplant as detected by qRT-PCR; n = 4 to 12 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (G) Time recipients spent mobile in the FST, out of a total time of 180 seconds, at day 14 after transplant; n = 5 to 12 mice per group; data pooled from 3 independent experiments. (H) Representative confocal images of IBA1+ microglia in the hippocampus ([left panel] original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm) of naïve CX3CR1cre × CSF1Rflfl mice. Higher magnification illustrates altered morphology ([right panel] original magnification, ×100; scale bar, 10 μm). Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (I) Quantification of IBA1+ cells in the hippocampus. (J) Violin plot showing the quantification of the size of IBA1+ cells in the hippocampus from 3 mice per group, expressed as pixels squared. Bold line represents the median. (K) Representative confocal images of IBA1+ microglia in the cortex ([left panel] original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm) of naïve CX3CR1cre × CSF1Rflfl mice. Higher magnification illustrates altered morphology ([right panel] original magnification, ×100; scale bar, 10 μm). Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (L) Quantification of IBA1+ cells in the cortex. (M) Violin plot showing the quantification of the size of IBA1+ cells in the cortex from 3 mice per group, expressed as pixels squared. Bold line represents the median. (N) mRNA expression of Sall1, Tnf, and Ccl12 in the brain as detected by qRT-PCR. (O) Time naïve CX3CR1cre × CSF1Rwt/wt and CX3CR1cre × CSF1Rflfl mice spent mobile in the FST out of a total time of 180 seconds. Statistics calculated by: (A-E) ordinary 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test; (F) Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric 1-way ANOVA with Dunn multiple comparisons test on ΔCT values; (G) ordinary 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test (GVHD + iso mAb vs GVHD + M279 vs TCD + iso mAb) and Student unpaired t test (TCD + iso mAb vs TCD + M279); (M-N) Mann-Whitney nonparametric t test (comparisons performed on ΔCT values for qRT-PCR data); (O) Student unpaired t test. Data presented as mean ± SEM, except for (J,M) presented as median. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; mRNA, messenger RNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Intriguingly, TCD + M279 mice performed worse in the FST than TCD + iso mAb controls (Figure 2G), suggestive of a requirement for homeostatic microglia for optimal performance of this task. Although microglial depletion in non-GVHD mice was associated with a modest expansion of both astrocytes and neurons, markers of astrocyte activation (Gfap, Timp1, and Serpina3n) and neuronal function (Prrt2, Nlgn2, and Arhgap33) were unchanged, and it did not induce inflammation because local cytokine production was similar or decreased compared with isotype-treated counterparts (supplemental Figure 5). Thus, the mechanism by which microglial depletion modulates behavior is unclear. To further interrogate the microglial contribution, we examined the impact of genetic deletion of CSF1R on microglia and behavior using the CX3CR1cre × CSF1Rflfl (C3AC mutant) line compared with CX3CR1cre × CSF1Rwt/wt controls. CX3CR1-restricted CSF1R ablation increased IBA1+ microglia density, as previously described,30,31 and median cell size in the cortex (Figure 2H-M), reduced whole-brain expression of the microglia-specific gene Sall1, and increased expression of Tnf and the repopulation marker Ccl12 (Figure 2N). C3AC mutants demonstrated significantly increased mobility in the FST as a sign of dysfunctional behavior compared with C3AC controls (Figure 2O). These results indicate an inflammatory microglia phenotype in the absence of constitutive CSF1R signaling and provide further evidence of the requirement for homeostatic microglia to permit normal behavior in the FST.

Examining region-specific effects at day 14 after M279, we observed marked microglial depletion in the hippocampus of GVHD and TCD recipients (Figure 3A-B) and nearby regions, including the habenula and choroid plexus (supplemental Figure 6A). GVHD + iso mAb microglia demonstrated MHC class II expression and increased cell number and size, compared with TCD iso mAb-treated controls (Figure 3A-G). Scarce remaining hippocampal microglia of M279-treated GVHD mice were increased in size compared with isotype-treated counterparts, further demonstrating impacts of CSF1R blockade on microglia phenotype (Figure 3C). In contrast, microglia remained in the cortex of aGVHD mice receiving M279 (Figure 3D-F) and exhibited further activation evidenced by MHC class II expression (Figure 3E) and increased cell size (Figure 3G). Importantly, cortical microglia depletion was extensive in TCD + M279 mice (Figure 3D-F), demonstrating that region-specific effects of CSF1R inhibition were not due to failed access of M279 to the cortex. To determine whether M279 administration depleted microglia before day 14 followed by repopulation with a CSF1R-independent population, we examined the impact of M279 on microglia at day 4 and day 7. Although the hippocampus showed extensive depletion from day 4 (supplemental Figure 6B), cortical microglia were not depleted by M279 at either time point (supplemental Figure 6C). These findings were reproducible in B6.CSF1r-eGFPxDBA2 F1 recipients of C57BL/6 BM ± T grafts in which days 0 to 14 M279 administration increased MHC class II expression on microglia, exacerbated infiltration of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells and Ly6ChiMHCII+ monocytes to the brain, depleted hippocampal but not cortical microglia, and could not restore behavior (supplemental Figure 7A-G). Moreover, in the BALB/c into B6 model, GVHD mice receiving the brain-penetrant CSF1R small molecule inhibitor, PLX5622, from days 0 to 14 after transplant retained more cortical (Figure 3H-J) and hippocampal microglia (supplemental Figure 8A-B) than TCD mice receiving the inhibitor, which was associated with maintained elevation of Tnf and Ccl2 levels in the brain (Figure 3K). Taken together, these data demonstrate region-specific requirements for CSF1R signaling in the brain after allo-HSCT, and alternative cytokine pathways likely function to maintain subsets of microglia during aGVHD.

CSF1R blockade during aGVHD induces region-specific microglia depletion. Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 recipients received 10 × 106 TCD BM with or without 5 × 106 enriched splenic T cells from BALB/c donors on day 0. M279 or isotype control antibody was administered from days 0 to 14. Behavior and CNS inflammation parameters were assessed on day 14 after transplant. (A) Representative confocal images of IBA1+ microglia and MHC class II expression in the hippocampus of GVHD and TCD mice at day 14 after transplant after treatment with isotype control antibody or M279; original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm. Insets demonstrate microglia morphology; original magnification, ×60; scale bar, 20 μm. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (B) Quantification of the total number of IBA1+ cells in the hippocampus at day 14 after transplant; n = 3 to 5 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (C) Violin plot showing the quantification of the size of IBA1+ cells in the hippocampus from 3 to 5 mice per group, expressed as pixels squared. Bold line represents the median. (D) Representative confocal images of IBA1+ microglia and MHC II expression in the cortex of GVHD and TCD mice at day 14 after transplant after treatment with isotype control antibody or M279; original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm. White arrows indicate IBA1+/MHC class II+ microglia. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (E) Representative confocal images demonstrating cortical microglia morphology; original magnification, ×60; scale bar, 20 μm. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (F) Quantification of the total number of IBA1+ cells in the cortex at day 14 after transplant; n = 3 to 5 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (G) Violin plot showing the quantification of the size of IBA1+ cells in the cortex from 3 to 5 mice per group, expressed as pixels squared. Bold line represents the median. (H) Representative images of IBA1+ cells in the cortex of GVHD and TCD mice at day 14 after transplant maintained on either a control diet or a diet containing the CSF1R small molecule inhibitor, PLX5622; original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (I) Representative images demonstrating cortical microglia morphology; original magnification, ×60; scale bar, 20 μm. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (J) Quantification of the total number of IBA1+ cells in the cortex at day 14 after transplant; n = 3 to 5 mice per group; data from 1 independent experiment. (K) mRNA expression of Tnf and Ccl12 in the brain at day 14 after transplant as detected by qRT-PCR. Statistics calculated by ordinary 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test (B,F,J,K [Ccl2]), Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric 1-way ANOVA with Dunn multiple comparisons test (C,G), and Mann-Whitney nonparametric unpaired t test (K [Tnf]). Data presented as mean ± SEM, except (C,G) presented as median. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; mRNA, messenger RNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean.

CSF1R blockade during aGVHD induces region-specific microglia depletion. Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 recipients received 10 × 106 TCD BM with or without 5 × 106 enriched splenic T cells from BALB/c donors on day 0. M279 or isotype control antibody was administered from days 0 to 14. Behavior and CNS inflammation parameters were assessed on day 14 after transplant. (A) Representative confocal images of IBA1+ microglia and MHC class II expression in the hippocampus of GVHD and TCD mice at day 14 after transplant after treatment with isotype control antibody or M279; original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm. Insets demonstrate microglia morphology; original magnification, ×60; scale bar, 20 μm. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (B) Quantification of the total number of IBA1+ cells in the hippocampus at day 14 after transplant; n = 3 to 5 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (C) Violin plot showing the quantification of the size of IBA1+ cells in the hippocampus from 3 to 5 mice per group, expressed as pixels squared. Bold line represents the median. (D) Representative confocal images of IBA1+ microglia and MHC II expression in the cortex of GVHD and TCD mice at day 14 after transplant after treatment with isotype control antibody or M279; original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm. White arrows indicate IBA1+/MHC class II+ microglia. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (E) Representative confocal images demonstrating cortical microglia morphology; original magnification, ×60; scale bar, 20 μm. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (F) Quantification of the total number of IBA1+ cells in the cortex at day 14 after transplant; n = 3 to 5 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (G) Violin plot showing the quantification of the size of IBA1+ cells in the cortex from 3 to 5 mice per group, expressed as pixels squared. Bold line represents the median. (H) Representative images of IBA1+ cells in the cortex of GVHD and TCD mice at day 14 after transplant maintained on either a control diet or a diet containing the CSF1R small molecule inhibitor, PLX5622; original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (I) Representative images demonstrating cortical microglia morphology; original magnification, ×60; scale bar, 20 μm. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (J) Quantification of the total number of IBA1+ cells in the cortex at day 14 after transplant; n = 3 to 5 mice per group; data from 1 independent experiment. (K) mRNA expression of Tnf and Ccl12 in the brain at day 14 after transplant as detected by qRT-PCR. Statistics calculated by ordinary 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test (B,F,J,K [Ccl2]), Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric 1-way ANOVA with Dunn multiple comparisons test (C,G), and Mann-Whitney nonparametric unpaired t test (K [Tnf]). Data presented as mean ± SEM, except (C,G) presented as median. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; mRNA, messenger RNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean.

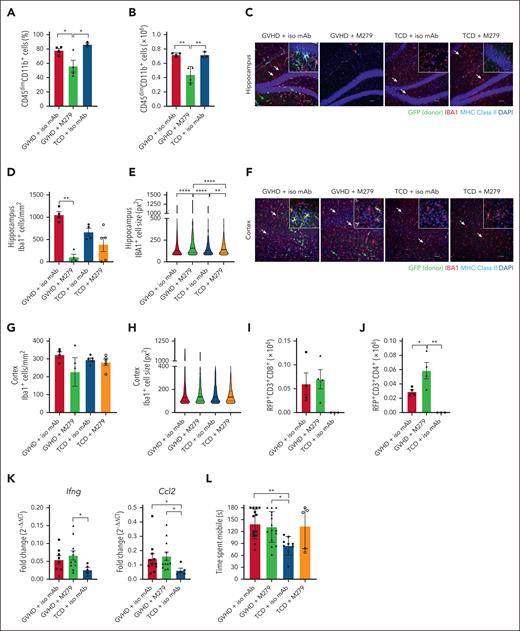

Established CNS cGVHD is not amenable to anti-CSF1R mAb treatment

We next administered isotype control or M279 from days 51 to 70 to examine CNS impacts during established cGVHD. Ly6Clo monocytes were specifically ablated by M279, and we confirmed the intended therapeutic effect of reduced cutaneous cGVHD pathology (supplemental Figure 9A-D). Antibody entry to the brain was detectable in recipients at day 70 by immunofluorescence (supplemental Figure 9E). GVHD + M279 mice showed an overall reduction in the frequency and number of CD45dimCD11b+ cells in the brain at day 70 (Figure 4A-B), without any preferential effect on donor BMDM or host microglia (supplemental Figure 9F-J). Transfer of B6.Csf1r-eGFP BM ± B6.RFP T cells into B6D2F1 recipients revealed infiltration of GFP+IBA1+MHCII+ donor BMDM into the hippocampus of GVHD + iso mAb, which were absent from TCD controls (Figure 4C). The hippocampus of GVHD + M279 mice showed depletion of IBA1+ cells, although the degree of ablation was heterogeneous across mice (Figure 4C-D and supplemental Figure 10A). Donor BMDM are also known to accumulate in the habenula and choroid plexus.9 Similarly, these regions also showed extensive depletion (supplemental Figure 10B), potentially owing to greater ease of antibody access. Depletion of hippocampal microglia occurred in some TCD mice receiving M279 (Figure 4C-D and supplemental Figure 10A), suggesting irradiation-induced perturbations to the BBB were variably reversed at this late stage. The median size of remaining IBA1+ cells from GVHD and TCD mice treated with M279 were significantly larger compared to isotype-treated counterparts, suggesting reactivity in response to nearby depletion (Figure 4E). The cortex of GVHD + M279 mice resembled that of the GVHD + iso mAb group in terms of donor infiltrate (Figure 4F), and almost all animals retained cortical IBA1+ cells (Figure 4G). Analysis of cell size revealed no increase in response to M279 at this time point (Figure 4H). In contrast to our observations at day 14, the cortex of TCD + M279 mice remained replete with microglia at day 70, indicating that cortical microglia/macrophage populations may remain intact at this time point due to limited antibody access. Partial depletion in GVHD mice was associated with persistent CNS inflammation, including donor T-graft–derived CD8+ and CD4+ infiltration and Ifng and Ccl2 elevation (Figure 4I-K), and subsequently, behavior was not improved after M279 administration (Figure 4L). These data suggest that antibody blockade of CSF1R does not represent a viable therapeutic strategy for CNS cGVHD.

CSF1R blockade during established cGVHD. Lethally irradiated B6D2F1 mice received 5 × 106 TCD BM cells from a B6.Csf1r-eGFP donor with or without 0.5 × 106 CD3+ RFP+ T cells on day 0. M279 or isotype control antibody was administered from days 51 to 70 after transplant. CNS cGVHD was assessed on day 70 after transplant. (A) Frequency of CD45dimCD11b+ cells in the brain at day 70 after transplant; n = 3 to 4 mice per group, representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) Absolute number of CD45dimCD11b+ cells in the brain at day 70 after transplant; n = 3 to 4 mice per group, representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) Representative confocal images of GFP+/IBA1+ donor BMDM and GFP–/IBA1+ host microglia, and MHC class II expression in the hippocampus. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (D) Quantification of the total number of IBA1+ cells in the hippocampus at day 70 after transplant; n = 4 to 5 mice per group; data representative of 2 independent experiments. (E) Violin plot showing the quantification of the size of IBA1+ cells in the hippocampus from 4 to 5 mice per group, expressed as pixels squared. Bold line represents the median. (F) Representative confocal images of GFP+/IBA1+ donor BMDM and GFP-/IBA1+ host microglia, and MHC class II expression in the cortex. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (G) Quantification of the total number of IBA1+ cells in the cortex at day 70 after transplant; n = 4 to 5 mice per group; data representative of 2 independent experiments. (H) Violin plot showing the quantification of the size of IBA1+ cells in the cortex from 4 to 5 mice per group, expressed as pixels squared. Bold line represents the median. (I) Absolute number of donor graft-derived RFP+CD3+CD8+ T cells in the brain at day 70 after transplant; n = 3 to 4 mice per group; data from 1 experiment. (J) Absolute number of donor graft-derived RFP+CD3+CD4+ T cells in the brain at day 70 after transplant; n = 3 to 4 mice per group; data from 1 experiment. (K) mRNA expression of Ifng and Ccl2 in brains of transplant recipients as detected by qRT-PCR; n = 5 to 11 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (L) Time recipients spent mobile in the FST out of a total time of 180 seconds at day 70 after transplant; n = 5 to 15 mice per group; data pooled from 3 independent experiments. (C,F) Original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm. Insets: original magnification, ×100; scale bar, 10 μm. White arrows indicate IBA1+/GFP–/MHC class II- host microglia. Green arrows indicate IBA1+/GFP+/MHC class II+ donor BMDM. Statistics calculated by (A-B,I-J,L) ordinary 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test, (D-E,G-H) Kruskall-Wallis nonparametric 1-way ANOVA with Dunn multiple comparisons test, (K) Mann-Whitney nonparametric t test (GVHD + iso mAb vs TCD + iso mAb or GVHD + M279 vs TCD + iso mAb). Data presented as mean ± SEM, except (E,H) presented as median. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; mRNA, messenger RNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean.

CSF1R blockade during established cGVHD. Lethally irradiated B6D2F1 mice received 5 × 106 TCD BM cells from a B6.Csf1r-eGFP donor with or without 0.5 × 106 CD3+ RFP+ T cells on day 0. M279 or isotype control antibody was administered from days 51 to 70 after transplant. CNS cGVHD was assessed on day 70 after transplant. (A) Frequency of CD45dimCD11b+ cells in the brain at day 70 after transplant; n = 3 to 4 mice per group, representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) Absolute number of CD45dimCD11b+ cells in the brain at day 70 after transplant; n = 3 to 4 mice per group, representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) Representative confocal images of GFP+/IBA1+ donor BMDM and GFP–/IBA1+ host microglia, and MHC class II expression in the hippocampus. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (D) Quantification of the total number of IBA1+ cells in the hippocampus at day 70 after transplant; n = 4 to 5 mice per group; data representative of 2 independent experiments. (E) Violin plot showing the quantification of the size of IBA1+ cells in the hippocampus from 4 to 5 mice per group, expressed as pixels squared. Bold line represents the median. (F) Representative confocal images of GFP+/IBA1+ donor BMDM and GFP-/IBA1+ host microglia, and MHC class II expression in the cortex. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (G) Quantification of the total number of IBA1+ cells in the cortex at day 70 after transplant; n = 4 to 5 mice per group; data representative of 2 independent experiments. (H) Violin plot showing the quantification of the size of IBA1+ cells in the cortex from 4 to 5 mice per group, expressed as pixels squared. Bold line represents the median. (I) Absolute number of donor graft-derived RFP+CD3+CD8+ T cells in the brain at day 70 after transplant; n = 3 to 4 mice per group; data from 1 experiment. (J) Absolute number of donor graft-derived RFP+CD3+CD4+ T cells in the brain at day 70 after transplant; n = 3 to 4 mice per group; data from 1 experiment. (K) mRNA expression of Ifng and Ccl2 in brains of transplant recipients as detected by qRT-PCR; n = 5 to 11 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (L) Time recipients spent mobile in the FST out of a total time of 180 seconds at day 70 after transplant; n = 5 to 15 mice per group; data pooled from 3 independent experiments. (C,F) Original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm. Insets: original magnification, ×100; scale bar, 10 μm. White arrows indicate IBA1+/GFP–/MHC class II- host microglia. Green arrows indicate IBA1+/GFP+/MHC class II+ donor BMDM. Statistics calculated by (A-B,I-J,L) ordinary 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test, (D-E,G-H) Kruskall-Wallis nonparametric 1-way ANOVA with Dunn multiple comparisons test, (K) Mann-Whitney nonparametric t test (GVHD + iso mAb vs TCD + iso mAb or GVHD + M279 vs TCD + iso mAb). Data presented as mean ± SEM, except (E,H) presented as median. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; mRNA, messenger RNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Ablation of donor CSF1R signaling at the onset of CNS cGVHD does not reduce inflammation or improve behavior

To examine the role of CSF1R signaling specifically in brain-infiltrating donor BMDM, we wished to transfer CX3CR1creERT2 × CSF1Rfl/fl × Ai9 BM, in which tamoxifen administration results in expression of tdTomato and ablation of CSF1R from CX3CR1-expressing cells. However, as monocytes rapidly turnover, CSF1R-deficient monocytes will be replaced by CSF1R-replete monocytes after tamoxifen administration and could thereafter infiltrate the brain. Thus, it was important to establish whether BM-derived cells persistently infiltrate the cGVHD brain or if this occurs in a time-restricted manner. To address this, we used Scl-CreERT2 × ZsGreenfl/fl mice as donors (Figure 5A), in which after tamoxifen injection, hematopoietic stem cells and their progeny permanently express ZsGreen, allowing us to track BM-derived cells in a time-controlled manner. We administered tamoxifen at day 35 during the development of cGVHD or day 70 during established disease and quantified ZsGreen+ infiltrate in recipient brains at day 70 or day 90, respectively (Figure 5A). The brain CD45dimCD11b+ population in the recipients of Scl-CreERT2 × ZsGreenfl/fl grafts showed <5% of this population was recruited after day 35 (Figure 5B) and only 2% after day 70 (Figure 5C). By day 70, up to 50% of the brain myeloid cells are of donor origin9; therefore, these findings demonstrate that the majority of BMDM progenitors have been recruited to the brain by day 35, corresponding with our finding of restricted cerebral VCAM1 expression to early after transplant. As such, we chose to deliver tamoxifen to recipients of CX3CR1creERT2 × CSF1Rwt/wt or CX3CR1creERT2 × CSF1Rfl/fl BM grafts at day 35; the latter should ablate CSF1R signaling in brain-infiltrated monocytes and donor-derived BMDM (Figure 5D-E), and we analyzed the brain at day 70. We observed a reduction in the number of donor BMDM in the brain (Figure 5F-G), confirming their CSF1R dependence. However, those that remained expressed significantly higher levels of MHC class II (Figure 5H). Numbers of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, local expression of Ifng and Ccl2, and behavior of recipients of CX3CR1creERT2 × CSF1Rfl/fl donor grafts remained unchanged compared with CX3CR1creERT2 × CSF1Rwt/wt BM controls (Figure 5I-L). These data support our pharmacological studies, suggesting that disruption of CSF1R signaling during cGVHD fails to suppress neuroinflammation or restore normal behavior.

Genetic ablation of donor BMDM CSF1R signaling. (A) Illustration of transplantation of 5 × 106 TCD BM cells and 0.5 × 106 CD3+ T cells from Scl-CreERT2 × ZsGreenfl/fl donors to lethally irradiated B6D2F1 recipients. Timeline shows the experimental design for tamoxifen treatment and harvest of Scl-CreERT2 × ZsGreenfl/fl BM recipients. Mice were treated with tamoxifen for 5 days beginning at day 35 or day 70 after transplant to induce Cre-recombinase activity and euthanized at day 70 or day 90, respectively. (B) Representative flow cytometry dot plots and quantification for ZsGreenneg and ZsGreenpos cells within the CD45dimCD11b+ population at day 70 post-transplant; n = 6 mice; data representative of 1 independent experiment. (C) Representative flow cytometry dot plots and quantification for ZsGreenneg and ZsGreenpos cells within the CD45dimCD11b+ population at day 90 after transplant; n = 6 mice; data representative of 1 independent experiment. (D) Transplant design for the transfer of either CX3CR1creERT2 × CSF1Rwt/wt Ai9 BM or CX3CR1creERT2 × CSF1Rfl/fl Ai9 BM plus enriched WT splenic CD3+ T cells into lethally irradiated B6.Csf1r-eGFP × DBA2 F1 recipients. Experimental timeline illustrates the delivery of tamoxifen at day 35 for 5 consecutive days to induce Cre-recombinase activity. Two recipients per group were euthanized at day 39 to confirm induction of TdTomato (Ai9) expression and loss of CSF1R-dependent monocyte populations. Remaining mice were sacrificed at day 70 after transplant. (E) Clinical scores of recipients. Arrow indicates the initiation of tamoxifen treatments at day 35; n = 10 to 12 mice per group. (F) Representative flow cytometry dot plots illustrating the CD45dimCD11b+ cell population within live Ly6GnegCD45pos cells. Donor BMDM are gated as CD45dimCD11bposTdTomatoposMacGreen GFPneg and host microglia are CD45dimCD11bposMacGreen GFPposTdTomatoneg. (G) Absolute number of CD45dimCD11b+TdTomato+ donor BMDM in the brain; n = 4 mice per group. (H) MHC class II expression on CD45dimCD11b+TdTomato+ donor BMDM in the brain (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]); n = 4 mice per group. (I) Absolute number of CD8+ T cells in the live CD3+ population in the brain; n = 4 mice per group. (J) Absolute number of CD4+ T cells in the live CD3+ population in the brain; n = 4 mice per group. (K) mRNA expression of Ifng and Ccl2 as detected by qRT-PCR; n = 5 to 6 mice per group. (L) Time recipients spent mobile in the FST, out of a total time of 180 seconds, at day 70 after transplant; n = 7 mice per group. Statistics calculated with Student unpaired t test. Data presented as mean ± SEM. ∗∗P < .01. mRNA, messenger RNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Genetic ablation of donor BMDM CSF1R signaling. (A) Illustration of transplantation of 5 × 106 TCD BM cells and 0.5 × 106 CD3+ T cells from Scl-CreERT2 × ZsGreenfl/fl donors to lethally irradiated B6D2F1 recipients. Timeline shows the experimental design for tamoxifen treatment and harvest of Scl-CreERT2 × ZsGreenfl/fl BM recipients. Mice were treated with tamoxifen for 5 days beginning at day 35 or day 70 after transplant to induce Cre-recombinase activity and euthanized at day 70 or day 90, respectively. (B) Representative flow cytometry dot plots and quantification for ZsGreenneg and ZsGreenpos cells within the CD45dimCD11b+ population at day 70 post-transplant; n = 6 mice; data representative of 1 independent experiment. (C) Representative flow cytometry dot plots and quantification for ZsGreenneg and ZsGreenpos cells within the CD45dimCD11b+ population at day 90 after transplant; n = 6 mice; data representative of 1 independent experiment. (D) Transplant design for the transfer of either CX3CR1creERT2 × CSF1Rwt/wt Ai9 BM or CX3CR1creERT2 × CSF1Rfl/fl Ai9 BM plus enriched WT splenic CD3+ T cells into lethally irradiated B6.Csf1r-eGFP × DBA2 F1 recipients. Experimental timeline illustrates the delivery of tamoxifen at day 35 for 5 consecutive days to induce Cre-recombinase activity. Two recipients per group were euthanized at day 39 to confirm induction of TdTomato (Ai9) expression and loss of CSF1R-dependent monocyte populations. Remaining mice were sacrificed at day 70 after transplant. (E) Clinical scores of recipients. Arrow indicates the initiation of tamoxifen treatments at day 35; n = 10 to 12 mice per group. (F) Representative flow cytometry dot plots illustrating the CD45dimCD11b+ cell population within live Ly6GnegCD45pos cells. Donor BMDM are gated as CD45dimCD11bposTdTomatoposMacGreen GFPneg and host microglia are CD45dimCD11bposMacGreen GFPposTdTomatoneg. (G) Absolute number of CD45dimCD11b+TdTomato+ donor BMDM in the brain; n = 4 mice per group. (H) MHC class II expression on CD45dimCD11b+TdTomato+ donor BMDM in the brain (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]); n = 4 mice per group. (I) Absolute number of CD8+ T cells in the live CD3+ population in the brain; n = 4 mice per group. (J) Absolute number of CD4+ T cells in the live CD3+ population in the brain; n = 4 mice per group. (K) mRNA expression of Ifng and Ccl2 as detected by qRT-PCR; n = 5 to 6 mice per group. (L) Time recipients spent mobile in the FST, out of a total time of 180 seconds, at day 70 after transplant; n = 7 mice per group. Statistics calculated with Student unpaired t test. Data presented as mean ± SEM. ∗∗P < .01. mRNA, messenger RNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Targeting donor macrophages through the IFNGR reduces CNS cGVHD inflammation and improves behavior

Our findings demonstrate that targeting the CSF1R axis is ineffective and potentially proinflammatory during CNS GVHD, and therefore, an alternative strategy to target macrophages is required. IFNG is a known regulator of MHC class II,32 and we have demonstrated upregulation of IFNG-response genes in donor BMDM.9 Therefore, we investigated the effect of ablating donor-specific IFNGR signaling by transferring WT or Ifngr-–/– BM ± WT T cells into B6.Csf1r-eGFPxDBA2F1 recipients (supplemental Figure 11A). Recipients of WT or Ifngr–/– BM + WT T cells exhibited similar GVHD scores, which were both increased compared with that of TCD controls, and showed evidence of skin pathology (supplemental Figure 11B-C). Although peripheral disease persisted, we observed a significant reduction in the number of donor BMDM and MHC class II expression in the brain of Ifngr–/– BM recipients (Figure 6A-B), whereas host microglia number and MHC class II expression were unaffected (Figure 6C-D). Loss of MHC class II+ donor BMDM was evident in the hippocampus (Figure 6E), cortex, and habenula (supplemental Figure 11D-E). Brains from recipients of Ifngr–/– BM also demonstrated reduced expression of antigen presentation–related genes Ciita and Cd74 (supplemental Figure 11F-G) and increased expression of the microglia-specific protein TMEM119, suggesting the loss of donor BMDM may aid in restoring a homeostatic microglia phenotype (supplemental Figure 11H). Ifngr–/– BM recipients showed modest reductions in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells and significantly reduced Ifng and Ccl2 expression in the brain and demonstrated significantly improved behavior compared with WT BM + T recipients (Figure 6F-I). These data suggest that targeting pathogenic macrophage differentiation via the IFNGR represents a viable strategy for attenuating CNS cGVHD.

Transfer of donor Ifngr–/– BM alleviates CNS cGVHD. (A) Absolute number of CD45dimCD11b+GFP– donor BMDM in the CD45posSytoxneg (live) population; n = 9 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (B) MHC class II expression on CD45dimCD11b+GFP– donor BMDM (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]); n = 9 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (C) Absolute number of CD45dimCD11b+GFP+ host microglia in the CD45posSytoxneg (live) population; n = 9 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (D) MHC class II expression on CD45dimCD11b+GFP+ host microglia; n = 9 mice per group, data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (E) Representative confocal images of IBA1+ cells and MHC II expression in the hippocampus at day 70 after transplant. Green arrows indicate host microglia (GFP+IBA1+MHCII–) and white arrows indicate donor BMDM (GFP–IBA1+MHCII+); original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (F) Absolute number of CD8+ T cells in the live CD3+ population in the brain; n = 4 to 5 mice per group; data representative of 2 independent experiments. (G) Absolute number of CD4+ T cells in the live CD3+ population in the brain; n = 4 to 5 mice per group; data representative of 2 independent experiments. (H) mRNA expression of Ifng and Ccl2 in the brain as detected by qRT-PCR; n = 6 mice per group, data representative of 2 independent experiments. (I) Time recipients spent mobile in the forced swim test, out of a total time of 180 seconds, at day 70 after transplant; n = 11 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (J) UMAP plot of the 54 789 nuclei isolated from the brains of recipients of WT BM + T, Ifngr–/– BM + WT T, and WT TCD BM, showing cell populations identified via unsupervised clustering. (K) UMAP plot demonstrating subclustering of the microglia/PVM/BMDM cluster into 2 distinct populations. (L) Depiction of myeloid cell proportions comprised of population 0 (microglia/PVM) and population 1 (BMDM) across samples. (M-P) Volcano plots show -log10 of the adjusted P value and average log2 fold change (FC) for all genes in the listed comparison, with highlighting of those that are significantly upregulated (avg_log2FC > 0.6 + P < .05, red) or downregulated (avg_log2FC < 0.6 + P > .5, blue). Gray dots indicate genes that are not differentially expressed. (M) Volcano plot for microglia in recipients of WT BM + T vs WT TCD BM. (N) Volcano plot for microglia in recipients of Ifngr-/- BM + T vs WT BM + T. (O) Volcano plot for BMDM in recipients of WT BM + T vs WT TCD BM. (P) Volcano plot for BMDM in recipients of Ifngr–/– BM + T vs WT BM + T. Statistics calculated by (A-D) Student unpaired t test; (F-G,I) ordinary 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test; (K) Mann-Whitney nonparametric t test (WT BM + T vs Ifngr–/– BM + WT T or WT BM + T vs WT BM TCD). Data presented as mean ± SEM. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; mRNA, messenger RNA; PVM, perivascular macrophages; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Transfer of donor Ifngr–/– BM alleviates CNS cGVHD. (A) Absolute number of CD45dimCD11b+GFP– donor BMDM in the CD45posSytoxneg (live) population; n = 9 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (B) MHC class II expression on CD45dimCD11b+GFP– donor BMDM (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]); n = 9 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (C) Absolute number of CD45dimCD11b+GFP+ host microglia in the CD45posSytoxneg (live) population; n = 9 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (D) MHC class II expression on CD45dimCD11b+GFP+ host microglia; n = 9 mice per group, data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (E) Representative confocal images of IBA1+ cells and MHC II expression in the hippocampus at day 70 after transplant. Green arrows indicate host microglia (GFP+IBA1+MHCII–) and white arrows indicate donor BMDM (GFP–IBA1+MHCII+); original magnification, ×20; scale bar, 50 μm. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (F) Absolute number of CD8+ T cells in the live CD3+ population in the brain; n = 4 to 5 mice per group; data representative of 2 independent experiments. (G) Absolute number of CD4+ T cells in the live CD3+ population in the brain; n = 4 to 5 mice per group; data representative of 2 independent experiments. (H) mRNA expression of Ifng and Ccl2 in the brain as detected by qRT-PCR; n = 6 mice per group, data representative of 2 independent experiments. (I) Time recipients spent mobile in the forced swim test, out of a total time of 180 seconds, at day 70 after transplant; n = 11 mice per group; data pooled from 2 independent experiments. (J) UMAP plot of the 54 789 nuclei isolated from the brains of recipients of WT BM + T, Ifngr–/– BM + WT T, and WT TCD BM, showing cell populations identified via unsupervised clustering. (K) UMAP plot demonstrating subclustering of the microglia/PVM/BMDM cluster into 2 distinct populations. (L) Depiction of myeloid cell proportions comprised of population 0 (microglia/PVM) and population 1 (BMDM) across samples. (M-P) Volcano plots show -log10 of the adjusted P value and average log2 fold change (FC) for all genes in the listed comparison, with highlighting of those that are significantly upregulated (avg_log2FC > 0.6 + P < .05, red) or downregulated (avg_log2FC < 0.6 + P > .5, blue). Gray dots indicate genes that are not differentially expressed. (M) Volcano plot for microglia in recipients of WT BM + T vs WT TCD BM. (N) Volcano plot for microglia in recipients of Ifngr-/- BM + T vs WT BM + T. (O) Volcano plot for BMDM in recipients of WT BM + T vs WT TCD BM. (P) Volcano plot for BMDM in recipients of Ifngr–/– BM + T vs WT BM + T. Statistics calculated by (A-D) Student unpaired t test; (F-G,I) ordinary 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test; (K) Mann-Whitney nonparametric t test (WT BM + T vs Ifngr–/– BM + WT T or WT BM + T vs WT BM TCD). Data presented as mean ± SEM. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; mRNA, messenger RNA; PVM, perivascular macrophages; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean.

To further interrogate IFNG-dependent transcriptional changes occurring during CNS cGVHD, we performed snRNA-seq on the brains of recipients of WT or Ifngr–/– BM ± WT T cells at day 70 (supplemental Figure 12A). After quality control, 54 789 nuclei with near uniform unique molecular identifiers, gene content, and mitochondrial gene content across samples were subjected to further analysis (supplemental Figure 12B). Identification of cell types was performed with an unsupervised classification method using the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas as a reference data set, revealing clusters of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia (Figure 6J and supplemental Figure 12C). We investigated the microglia/perivascular macrophages/BMDM cluster (Figure 6K), which subclustered into population 0 enriched for microglia-specific genes (Sall1, Siglech, and Tmem119), and population 1 expressing markers associated with a hematopoietic origin and antigen presentation (Klra2, Ms4a7, Mrc1, Cd74, H2-Aa, and H2-Eb1) (supplemental Figure 13A). We confirmed these populations derived from different genotypes, supporting a host/donor cell-type assignment (supplemental Figure 13B). In line with our previous study,9 the myeloid population in WT GVHD samples comprised ∼50% BMDM, which was reduced in recipients of Ifngr–/– BM (Figure 6L). We gained insight into transcriptomic differences between donor BMDM and host microglia, revealing additional differentially expressed genes including the Rho GTPase–activating protein Arhgap15 and the cysteine protease inhibitor Cst3 (supplemental Figure 13C). Microglia from recipients of WT GVHD maintained upregulation of H2-K1, H2-D1, and Cd74 relative to TCD controls (Figure 6M), indicative of persistent transcriptional activation. Transfer of Ifngr–/– BM showed a beneficial effect on host microglia, with downregulation of Cd74 and upregulation of the homeostatic marker Fcrls relative to microglia from WT GVHD recipients (Figure 6N). Intriguingly, WT GVHD BMDM downregulate Skiv2l encoding an RNA exosome (Figure 6O), in which deficiency in this gene has been reported to activate the mTORC1 pathway, leading to autoinflammatory disease.33 This may be a potential alternative target in GVHD CNS-infiltrating BMDM. As anticipated, BMDM from Ifngr–/– BM recipients specifically downregulated MHC II–associated genes H2-Eb1, H2-Aa, and Cd74 (Figure 6P). Thus, we demonstrate that reducing donor MHC class II+ BMDM infiltration is critical for attenuating CNS cGVHD.

Additionally, we compared population proportions across samples and noted differences in neuronal clusters and oligodendrocytes. (supplemental Figure 14A). The number of significant differentially expressed genes in each population was generally reduced in recipients of Ifngr–/– BM relative to TCD controls, when compared with WT GVHD (supplemental Figure 14B). Because demyelination is reported in patients with CNS GVHD,34,35 we questioned whether oligodendrocytes, as myelinating cells, were affected. We identified a small population of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (Pdgfra, Myt1, and Olig1) and a larger mature oligodendrocyte population expressing Mbp, Mog, and Mag (Figure 7A). Subclustering revealed 2 distinct populations of mature oligodendrocytes (0 and 2), the latter of which was highly enriched in WT GVHD brains, reduced in recipients of Ifngr–/– BM, and absent from TCD mice (Figure 7B-C). Comparison among the 4 OPC/oligodendrocyte populations in WT GVHD samples revealed a signature marked by upregulation of interferon-inducible genes, including Stat1, Cd274, H2-K1, H2-D1, and B2m, and genes required for antigen processing and MHC class I binding (Psmb9, Tap1, and Tap2) (Figure 7DE). These data reveal a disease-associated oligodendrocyte population in cGVHD. Given this population was reduced in recipients of Ifngr–/– BM, these findings provide additional evidence that modulating the IFNGR-signaling axis in donor cells to reduce CNS inflammation has beneficial effects in the brain beyond the myeloid compartment.

snRNA-seq reveals an interferon-responsive oligodendrocyte population in the cGVHD brain. (A) UMAP plots depicting the expression of various genes related to the identity of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) and oligodendrocytes within the oligodendrocyte population. (B) UMAP plot depicting subclustering of OPCs & oligodendrocytes split by sample type. (C) Bar plot indicates the representation of each OPC/oligodendrocyte subcluster across the sample types. (D) Heat map depicting the average gene expression of the 44 genes identified as differentially expressed between population 0 and 2 in WT GVHD samples. (E) Volcano plot for WT GVHD oligodendrocytes in population 2 vs population 0. Plots shows -log10 of the adjusted P value and average log2 fold change (FC) for all genes, with highlighting of those that are significantly upregulated (avg_log2FC > 0.6 + P < .05, red) or downregulated (avg_log2FC < 0.6 + P > .5, blue) in oligodendrocytes from population 2 vs populations 0. Gray dots indicate genes that are not differentially expressed.

snRNA-seq reveals an interferon-responsive oligodendrocyte population in the cGVHD brain. (A) UMAP plots depicting the expression of various genes related to the identity of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) and oligodendrocytes within the oligodendrocyte population. (B) UMAP plot depicting subclustering of OPCs & oligodendrocytes split by sample type. (C) Bar plot indicates the representation of each OPC/oligodendrocyte subcluster across the sample types. (D) Heat map depicting the average gene expression of the 44 genes identified as differentially expressed between population 0 and 2 in WT GVHD samples. (E) Volcano plot for WT GVHD oligodendrocytes in population 2 vs population 0. Plots shows -log10 of the adjusted P value and average log2 fold change (FC) for all genes, with highlighting of those that are significantly upregulated (avg_log2FC > 0.6 + P < .05, red) or downregulated (avg_log2FC < 0.6 + P > .5, blue) in oligodendrocytes from population 2 vs populations 0. Gray dots indicate genes that are not differentially expressed.

Discussion

This study investigated CSF1R inhibition as a strategy to treat CNS GVHD, revealing that this approach, rather than mirroring the efficacy observed in peripheral target organs, conversely promotes neuroinflammation and fails to restore normal behavior. As an alternative treatment strategy, we propose targeting of IFNGR signaling. Our findings are highly clinically relevant given the ongoing clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier, NCT04710576) and extended access programs (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier, NCT05544032) based on CSF1R inhibition for fibrotic cGVHD.

In our murine models, irrespective of the presence of GVHD, transplantation resulted in disruption of the BBB sufficient to permit mAb access to the CNS. BBB impairment was most marked early after transplant and was exacerbated by GVHD, indicative of the contribution of systemic inflammation. BBB repair was evident, however, microglia depletion in non-GVHD mice at day 70 was heterogeneous, indicating variability in the degree of BBB repair. In line with the use of total body irradiation in clinical allo-HSCT,36 case reports of CNS cGVHD also report evidence of BBB disruption years after transplant, based on cerebrospinal fluid and magnetic resonance imaging analyses,37,38 and detection of peripheral immune infiltrates in the parenchyma.22,39 These data would suggest the brain may also be permissive to antibody access in clinical allo-HSCT recipients. In support of this concept, systemic immunotherapy using rituximab for recurrent primary CNS lymphoma40 and anti–PD-1 in patients with glioma41 have both shown evidence of measurable antibody concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid with functional on-target effects.

Early after transplant, we investigated the potential degree of microglia depletion using an antibody-based approach and queried whether CSF1R blockade may be a viable therapy for CNS aGVHD. Unexpectedly, CSF1R blockade was associated with region-specific depletion and exacerbated inflammation. Mechanistically, because CSF1R inhibition blocks the differentiation of Ly6Chi inflammatory monocytes into Ly6Clo monocytes,12,15,42 increased Ly6Chi inflammatory monocytes are available to be recruited to the brain in response to elevated local CCL2 expression. Moreover, previous studies have demonstrated a requirement for resident gut macrophages in constraining alloreactive donor T cells during aGVHD,15,29 and their depletion via CSF1R inhibition in recipients before transplant exacerbates aGVHD.27 In the nonlethal model used in this study, CSF1R inhibition had no effects on systemic inflammation, but the minor increases in gut pathology may reflect local T-cell expansion and subsequently increased CNS infiltration. Notably, inflammatory responses to microglia depletion have also been observed in ischemic stroke,43 and mice haploinsufficient for CSF1R (Csf1r+/−) harbor increased microglia and exhibit cognitive dysfunction.44

The observed partial depletion of microglia suggests that microglia may derive support from additional cytokines independent of CSF1R during inflammation.45 This may be mediated by granulocyte-macrophage CSF,46 produced by endothelium,47 activated astrocytes,48 monocytes,49 and donor T cells.50 Alternatively, augmented Ifng expression observed in GVHD mice at day 14 after CSF1R inhibition may be indicative of another survival mechanism, because IFN-γ has previously been found to independently sustain tumor-associated macrophages during CSF1R inhibition in a glioma model.51 Partial microglia depletion can also promote CNS engraftment of peripheral macrophages,52 suggesting that blockade of CSF1R early after transplant may accelerate the development of CNS cGVHD pathology. Microglia in the brains of naïve CX3CR1cre × CSF1Rfl/fl mice similarly demonstrated altered brain myeloid cell composition in a proinflammatory manner. This model also confirmed a requirement for homeostatic microglia in the FST, which has not previously been reported. Our findings extend the current literature showing that blocking CSF1R signaling in microglia can be proinflammatory, alter behavior, and exacerbate CNS disease in aGVHD.

We anticipated improved outcomes with removal of donor BMDM in cGVHD, either through pharmacological or genetic approaches. Microglia/BMDM depletion in cGVHD was incomplete and variable across animals, likely contingent on earlier levels of inflammation and BBB damage. Ultimately, CSF1R mAb therapy was insufficient to substantially reduce MHC class II+ donor BMDM and inflammation in the brain. Despite the lack of efficacy in improving CNS cGVHD, our findings critically reveal the previously unknown effects of systemic CSF1R blockade on the brain during GVHD. Alternatively, we demonstrate a specific requirement for IFNGR-dependent expression of MHC class II on donor BMDM for driving altered behavior in CNS cGVHD. Reducing CNS donor BMDM via this pathway also promoted a homeostatic microglia phenotype. Moreover, snRNA-seq revealed a population of disease-associated oligodendrocytes, which was partially reduced in recipients of IFNGR-deficient grafts. Similar populations have been described in models of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis,53 Alzheimer disease,54 and white matter aging55 and are associated with oligodendrocyte injury and demyelination. Our findings are, to the best of our knowledge, the first to describe lasting changes to oligodendrocytes in cGVHD, which can, at least in part, be restored by attenuating CNS inflammation. This indicates that targeting donor IFN-γ can have beneficial effects beyond the myeloid compartment and may act as an important marker of disease through which the efficacy of potential therapeutics could be assessed. Our findings suggest that currently available therapeutics targeting the IFN-γ pathway, such as the JAK 1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib or the IFN-γ neutralizing antibody emapalumab may be of benefit, although extensive access to the brain and/or the ability to reach therapeutic drug concentrations in the CNS during chronic disease remain a concern. In this regard, ruxolitinib passage through the BBB is only reported with high doses during acute infection56 and is not penetrable at steady state. Thus, for CNS cGVHD, future investigations focused on alternative drug delivery strategies to target the CNS, such as intrathecal administration and selective brain-permeable therapeutics, and approaches to prevent the onset of CNS inflammation should be instructive.

In summary, we report the outcomes of therapeutic CSF1R antibody blockade on CNS manifestations of both acute and chronic GVHD. To date, treatments for CNS cGVHD have not yet been considered, and our findings demonstrate that mAb blockade of CSF1R as a novel systemic therapy may perpetuate neuroinflammation. As such, our study supports the inclusion of formal monitoring of CNS presentations including neurocognitive evaluations and analysis of CNS neuroinflammation in ongoing clinical trials, particularly for patients with ongoing inflammation or evidence of any previous CNS involvement. As an alternative therapeutic strategy, we highlight IFNGR signaling as a modifiable pathway to be explored in future investigations for attenuating CNS cGVHD.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute Animal Facility for care and maintenance of mice used in this study. The authors acknowledge the Centre for Comprehensive Biomedical Imaging (QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute Core Facility) the Lighthouse Core Facility (Medical Centre, University of Freiburg) for microscopy and flow cytometry equipment and support. The authors thank Michael Rist for nuclei sorting. The authors thank Angelika Christ and the Sequencing Facility at the Institute for Molecular Biosciences, The University of Queensland, for performing library preparation and 10× Genomics Chromium sequencing. The authors thank Christian Engwerda (QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute) for kindly providing the B6.Ifngr–/– mice, Madeleine Kirsting for assistance with the graphical abstract, and Andrew Clouston for histopathological scoring.

This work was supported by grant 1188584 (K.P.A.M. and J.V.) from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council; an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship (R.C.A.). J.V. holds a senior medical research fellowship from the Sylvia and Charles Viertel Foundation (J.V.); and by DFG, SFB-1479 – Project ID: 441891347, ERC Advanced grant (101094168 AlloCure), Deutsche Krebshilfe (70114655), the José Carreras Leukemia Foundation (DJCLS 09R/2022), and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS grant ID: 7030-23; R.Z.).

Authorship

Contribution: R.C.A. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, prepared the figures, and wrote the manuscript; D.C.-C. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and approved the manuscript; G.T.L. and C.R.H. performed experiments and approved the manuscript; J.M.V. designed and performed experiments and approved the manuscript; M.J.R. and P.B. provided reagents and approved the manuscript; J.V., K.K.C., J.A.W., and G.R.H. provided intellectual input and approved the manuscript; S.P.N. performed experiments, provided intellectual input, and approved the manuscript; S.N.F. analyzed data, provided intellectual input, and approved the manuscript; R.Z. provided reagents, contributed intellectual input, and approved the manuscript; and K.P.A.M. designed, led, and coordinated the project, performed experiments, analyzed data, and prepared and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.Z. received honoraria from Novartis, Incyte, Mallinckrodt, Sanofi, and VectivBio. K.P.A.M. received honoraria from Incyte and Deciphera. G.R.H. has consulted for Generon Corporation, NapaJen Pharma, iTeos Therapeutics, Neoleukin Therapeutics, Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, Incyte, and Cynata Therapeutics; and has received research funding from Compass Therapeutics, Syndax Pharmaceuticals, Applied Molecular Transport, Serplus Technology, Heat Biologics, Laevoroc Oncology, iTEOS Therapeutics, OPNA Bio, and Genentech. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kelli P. A. MacDonald, Antigen Presentation and Immunoregulation Laboratory, Infection and Inflammation Program, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, 300 Herston Rd, Herston, QLD 4006, Australia; email: kelli.macdonald@qimrberghofer.edu.au.

References

Author notes

Single nuclei RNA sequencing data are accessible through NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus database (GSE245360).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.