Key Points

Mutant TP53 AML and MDS-EB do not differ with respect to molecular characteristics and survival.

Mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB should be considered a single molecular disease entity.

Abstract

Substantial heterogeneity within mutant TP53 acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome with excess of blast (MDS-EB) precludes the exact assessment of prognostic impact for individual patients. We performed in-depth clinical and molecular analysis of mutant TP53 AML and MDS-EB to dissect the molecular characteristics in detail and determine its impact on survival. We performed next-generation sequencing on 2200 AML/MDS-EB specimens and assessed the TP53 mutant allelic status (mono- or bi-allelic), the number of TP53 mutations, mutant TP53 clone size, concurrent mutations, cytogenetics, and mutant TP53 molecular minimal residual disease and studied the associations of these characteristics with overall survival. TP53 mutations were detected in 230 (10.5%) patients with AML/MDS-EB with a median variant allele frequency of 47%. Bi-allelic mutant TP53 status was observed in 174 (76%) patients. Multiple TP53 mutations were found in 49 (21%) patients. Concurrent mutations were detected in 113 (49%) patients. No significant difference in any of the aforementioned molecular characteristics of mutant TP53 was detected between AML and MDS-EB. Patients with mutant TP53 have a poor outcome (2-year overall survival, 12.8%); however, no survival difference between AML and MDS-EB was observed. Importantly, none of the molecular characteristics were significantly associated with survival in mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB. In most patients, TP53 mutations remained detectable in complete remission by deep sequencing (73%). Detection of residual mutant TP53 was not associated with survival. Mutant TP53 AML and MDS-EB do not differ with respect to molecular characteristics and survival. Therefore, mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB should be considered a distinct molecular disease entity.

Introduction

Mutations in TP53 are present in approximately 10% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and represent a unique subtype with poor outcome.1-5TP53 is located on chromosome 17p13 and is essential for cell cycle control and DNA damage response.6 Although the exact mechanism of leukemogenesis for mutant TP53 AML remains unknown, it has been shown that some TP53 mutations drive a dominant negative effect and typically occur in founding clones that expand after cytotoxic stress.7,8 Mutant TP53 is strongly associated with large structural and complex chromosomal aberrations, as illustrated by the co-occurrence of complex karyotypes (CK), which is associated with reduced overall survival in myeloid malignancies.9-11 In line with the observed poor outcome, mutant TP53 AML is assigned to the adverse risk category of the 2017 European LeukemiaNet (ELN) risk classification and is recommended to receive intensive consolidation treatments.11 Although patients with mutant TP53 AML in complete remission (CR) generally receive allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), relapse rates remain considerably high.12

Recent findings in MDS assign additional prognostic value to the molecular characteristics of mutant TP53, including TP53 mutant allelic status (mono- or bi-allelic) and TP53 clone size.4,5,13 However, recent studies exploring the link between these molecular characteristics and outcome in AML were limited and inconclusive.14,15 Furthermore, it is currently unknown whether mutant TP53 high risk MDS with excess of blast (MDS-EB) and AML differ in molecular makeup and response to treatment and should be considered as separate entities.

Here, we present an in-depth characterization of a large cohort of newly diagnosed mutant TP53 AML and MDS-EB in relation to survival. We performed next-generation sequencing (NGS) to assess the molecular characteristics of mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB in detail, including TP53 mutant allelic status (mono- or bi-allelic), the number of TP53 mutations, mutant TP53 clone size, concurrent mutations, cytogenetics, and molecular minimal/measurable residual disease (MRD).

Methods

Patients and samples

In total, 2200 patients with AML and MDS-EB (international prognostic scoring system [IPSS] ≥ 1.5 or revised IPSS > 4.5) were assessed for eligibility and treated in the Haemato-Oncology Foundation for Adults in the Netherlands and Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (HOVON-SAKK) clinical trials between 2001 and 2017 (supplemental Figure 1 available on the Blood Web site). All patients received standard induction chemotherapy and were consolidated according to the HOVON-SAKK study protocols. Details of treatment protocols were described previously (www.hovon.nl).16-21 All trial participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. DNA was isolated from diagnostic bone marrow samples of 2200 patients with AML/MDS-EB and 537 CR samples (supplementary Methods). In 33 patients with AML/MDS-EB carrying TP53 variants with a variant allele frequency (VAF) >40%, DNA from saliva was available to verify the germline status.

Cytogenetics and SNP array analyses

Cytogenetic analysis was carried out at the local reference centers using standard protocols. These data, including karyotypes and FISH, were centrally peer-reviewed by clinical genetics laboratory specialists. The clonal structural and numerical chromosomal abnormalities were reported in accordance with the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature and the ELN 2017 recommendations.11 CK was defined by 3 or more unrelated chromosome abnormalities in the absence of one of the World Health Organization–designated recurring translocations or inversions, that is, t(8;21), inv(16) or t(16;16), t(9;11), t(v;11)(v;q23.3), t(6;9), inv(3) or t(3;3), AML with BCR-ABL1.11 Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using Illumina Infinium GSA+MD-24 version 3.0 BeadChip (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA) on 134 of 230 mutant TP53 AML samples (110 bi-allelic and 24 mono-allelic mutants). The array was scanned with the Illumina iScan Control. Genome studio version 2.1 and Nexus Discovery version 10.0 (Biodiscovery, El Segundo, CA) were used for data analysis.

Targeted NGS and TP53 deep sequencing

The TruSight Myeloid Sequencing panel (Illumina) was used to detect the presence of driver mutations at diagnosis. Details were described previously.22 Only pathogenic TP53 variants were included as defined by occurrence in the COSMIC and IARC TP53 database as well as by analyses in silico with programs such as Polyphen-2, SIFT, FATHMM, MetaSVM, MetaLR, CADD, DANN, and ClinVar. The limit of detection was VAF 1% at diagnosis. To detect TP53 mutations in CR, we used Illumina-based deep sequencing (supplementary Methods). The limit of detection in the follow-up samples was VAF 0.001% (variable depending on TP53 mutation type). In the case of multiple TP53 mutations, the highest VAF was chosen for MRD analysis. Of note, patients with TP53 germline mutations were excluded from MRD assessment (n = 2).

Allocation of patients based on TP53 mutant allelic status

Patients with mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB were considered bi-allelic when (1) 2 or more TP53 gene variants were detected, regardless of the VAF; (2) at least 1 TP53 gene variant co-occurred with a cytogenetic aberration involving chromosome 17p (eg, abnormality of 17p or monosomy 17); or (3) TP53 mutations were detected with a VAF >55% (supplemental Figure 2). The allocation to the bi-allelic mutant TP53 group by a VAF threshold of >55% was confirmed in all 15 of 110 patients with bi-allelic mutant TP53 AML that could be evaluated for copy number alterations by SNP array analyses (ie, either loss of the wild-type allele or segmental uniparental disomy of the mutant TP53 allele).

Statistical analysis

Associations between variables were tested by the Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and by the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. The primary endpoint of the study was overall survival, defined as death from any cause. Survival time was calculated from the start of induction chemotherapy until the event of interest or censoring. Of note, the survival time in the analysis evaluating allogeneic HSCT started at the date of transplant. To compare the survival distributions, we used the log-rank test and the Cox proportional hazards model. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by interaction with time. All P values were two sided, and P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were executed with Stata Statistical Software, Release 16.0 (College Station, TX).

Results

Molecular characteristics of mutant TP53 AML and MDS-EB

We detected 283 TP53 mutations in 230 of 2200 (10.5%) patients with AML/MDS-EB by NGS (Table 1; supplemental Figure 1). Of 230 patients with AML/MDS-EB, 44 (19%) were diagnosed with MDS-EB. No significant difference in age, sex, white blood cells, remission rate, and consolidation treatment was present between AML and MDS-EB (Table 1). Deletion 5q was the only cytogenetic aberration significantly more frequently present in MDS-EB (P = .025). Of note, in 112 patients with mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB, concurrent chromosomal aberrations involving TP53 (eg, abnormality 17p or loss of chromosome 17) were detected.

Patient characteristics of AML/MDS-EB with mutated TP53 (n = 230)

| . | AML (n = 186) . | MDS-EB (n = 44) . | AML/MDS-EB (n = 230) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | .820 | |||

| Median | 62 | 63 | 62 | |

| Range | 18-80 | 35-73 | 18-80 | |

| Sex, no. (%) | .736 | |||

| M | 111 (60) | 25 (57) | 136 (59) | |

| F | 75 (40) | 19 (43) | 94 (41) | |

| White blood cells at diagnosis, no. (%)* | ||||

| 100 | 183 (99) | 44 (100) | 227 (99) | 1.000 |

| 100 | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Last treatment before first CR, no. (%) | ||||

| Refractory | 70 (38) | 10 (23) | 80 (35) | |

| Cycle I | 90 (48) | 29 (66) | 119 (52) | |

| Cycle II | 26 (14) | 5 (11) | 31 (13) | |

| Consolidation therapy, no. (%) | 1.000 | |||

| No allogeneic HSCT | 137 (74) | 33 (75) | 170 (74) | |

| Allogeneic HSCT | 49 (26) | 11 (25) | 60 (26) | |

| Cytogenetics, no. (%)† | ||||

| Monosomy 5 | 51 (28) | 11 (27) | 62 (28) | 1.000 |

| Deletion 5q | 78 (44) | 26 (63) | 104 (47) | |

| Monosomy 7 | 58 (32) | 14 (34) | 72 (33) | |

| Monosomy 17 | 71 (40) | 10 (24) | 81 (37) | |

| Abnormality 17p | 33 (18) | 6 (15) | 39 (18) | |

| Complex karyotype | 148 (83) | 37 (90) | 185 (84) | |

| Monosomal karyotype | 139 (78) | 35 (85) | 174 (79) |

| . | AML (n = 186) . | MDS-EB (n = 44) . | AML/MDS-EB (n = 230) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | .820 | |||

| Median | 62 | 63 | 62 | |

| Range | 18-80 | 35-73 | 18-80 | |

| Sex, no. (%) | .736 | |||

| M | 111 (60) | 25 (57) | 136 (59) | |

| F | 75 (40) | 19 (43) | 94 (41) | |

| White blood cells at diagnosis, no. (%)* | ||||

| 100 | 183 (99) | 44 (100) | 227 (99) | 1.000 |

| 100 | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Last treatment before first CR, no. (%) | ||||

| Refractory | 70 (38) | 10 (23) | 80 (35) | |

| Cycle I | 90 (48) | 29 (66) | 119 (52) | |

| Cycle II | 26 (14) | 5 (11) | 31 (13) | |

| Consolidation therapy, no. (%) | 1.000 | |||

| No allogeneic HSCT | 137 (74) | 33 (75) | 170 (74) | |

| Allogeneic HSCT | 49 (26) | 11 (25) | 60 (26) | |

| Cytogenetics, no. (%)† | ||||

| Monosomy 5 | 51 (28) | 11 (27) | 62 (28) | 1.000 |

| Deletion 5q | 78 (44) | 26 (63) | 104 (47) | |

| Monosomy 7 | 58 (32) | 14 (34) | 72 (33) | |

| Monosomy 17 | 71 (40) | 10 (24) | 81 (37) | |

| Abnormality 17p | 33 (18) | 6 (15) | 39 (18) | |

| Complex karyotype | 148 (83) | 37 (90) | 185 (84) | |

| Monosomal karyotype | 139 (78) | 35 (85) | 174 (79) |

Numbers may not sum to 230 because of missing values.

Cytogenetics failed in 10 patients.

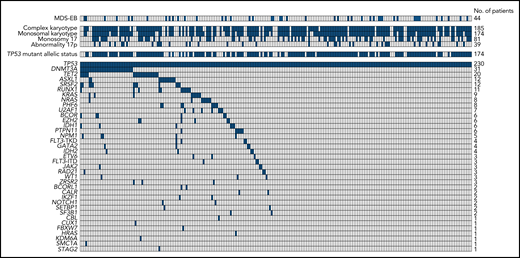

Two or more TP53 mutations were found in 49 AML/MDS-EB cases (Table 2; supplemental Figure 2). In total, 206 missense, 16 nonsense, 38 insertion/deletion, and 23 splice-site mutations were detected (supplemental Figure 3). Nearly all missense mutations occurred in the TP53 DNA binding domain (supplemental Figure 3). In total, 56 of the 230 patients with TP53 mutant AML/MDS-EB (24.3%) were considered mono-allelic and 174 (75.7%) were bi-allelic (Table 2; supplemental Figure 2). The mutant TP53 clone size was normally distributed with a median VAF of 47% (supplemental Figure 4A). Concurrent mutations were detected in only 113 (49%) patients with mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB (Figure 1). The most frequent concurrent mutations were detected in DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1, RUNX1, and SRSF2 (Figure 1; Table 2). The TP53 mutant allelic status, number of TP53 mutations, TP53 clone size, and concurrent mutations at diagnosis did not significantly differ between mutant TP53 AML and MDS-EB (Table 2).

Molecular characteristics of mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB (n = 230)

| . | AML (n = 186) . | MDS-EB (n = 44) . | AML/MDS-EB (n = 230) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 mutant allelic status, no. (%) | .241 | |||

| Mono-allelic | 42 (23) | 14 (32) | 56 (24) | |

| Bi-allelic | 144 (77) | 30 (68) | 174 (76) | |

| Number of TP53 mutations, no. (%) | .153 | |||

| Single | 150 (81) | 31 (70) | 181 (79) | |

| Multiple | 36 (19) | 13 (30) | 49 (21) | |

| Mutant TP53 clone size, VAF (%) | .409 | |||

| Median | 48 | 41 | 47 | |

| Range | 1-97 | 3-91 | 1-97 | |

| Mutation at diagnosis, no. (%) | ||||

| Any concurrent | 95 (51) | 18 (41) | 113 (49) | .244 |

| DNMT3A | 25 (13) | 6 (14) | 31 (13) | 1.000 |

| TET2 | 17 (9) | 3 (7) | 20 (9) | .773 |

| ASXL1 | 10 (5) | 2 (5) | 12 (5) | 1.000 |

| RUNX1 | 10 (5) | 1 (2) | 11 (5) | .695 |

| SRSF2 | 11 (6) | 1 (2) | 12 (5) | .471 |

| . | AML (n = 186) . | MDS-EB (n = 44) . | AML/MDS-EB (n = 230) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 mutant allelic status, no. (%) | .241 | |||

| Mono-allelic | 42 (23) | 14 (32) | 56 (24) | |

| Bi-allelic | 144 (77) | 30 (68) | 174 (76) | |

| Number of TP53 mutations, no. (%) | .153 | |||

| Single | 150 (81) | 31 (70) | 181 (79) | |

| Multiple | 36 (19) | 13 (30) | 49 (21) | |

| Mutant TP53 clone size, VAF (%) | .409 | |||

| Median | 48 | 41 | 47 | |

| Range | 1-97 | 3-91 | 1-97 | |

| Mutation at diagnosis, no. (%) | ||||

| Any concurrent | 95 (51) | 18 (41) | 113 (49) | .244 |

| DNMT3A | 25 (13) | 6 (14) | 31 (13) | 1.000 |

| TET2 | 17 (9) | 3 (7) | 20 (9) | .773 |

| ASXL1 | 10 (5) | 2 (5) | 12 (5) | 1.000 |

| RUNX1 | 10 (5) | 1 (2) | 11 (5) | .695 |

| SRSF2 | 11 (6) | 1 (2) | 12 (5) | .471 |

Overview of cytogenetic aberrations and concurrent mutations in mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB (n = 230). Each column represents an individual patient, and the presence of the aberration is indicated in blue. The upper panel shows the cytogenetic aberrations, and the lower panel shows the concurrent mutations. Patients with MDS-EB or bi-allelic TP53 mutant status are also indicated in blue. In case of failed cytogenetics, the cytogenetic aberrations were considered negative.

Overview of cytogenetic aberrations and concurrent mutations in mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB (n = 230). Each column represents an individual patient, and the presence of the aberration is indicated in blue. The upper panel shows the cytogenetic aberrations, and the lower panel shows the concurrent mutations. Patients with MDS-EB or bi-allelic TP53 mutant status are also indicated in blue. In case of failed cytogenetics, the cytogenetic aberrations were considered negative.

Of note, most (84%) patients with mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB have CK, and many associations between CK and the different molecular characteristics were observed (Table 1; supplemental Table 1). CK was detected in most patients with bi-allelic mutant TP53 (97%), in patients with multiple TP53 mutations (94%), and in patients with larger TP53 clones (94% in VAF >40%) (supplemental Table 1; supplemental Figure 4B). Concurrent mutations were enriched in AML/MDS-EB marked by non-CK, yet the most prevailing mutated genes (DNMT3A and TET2) were not significantly associated with CK (supplemental Table 1).

Association of mutant TP53 characteristics and outcome in AML and MDS-EB

We next compared outcome of patients with mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB in relation to the established ELN 2017 prognostic subgroups. Mutant TP53 strongly associated with reduced survival in the context of the ELN 2017 adverse risk category (2-year overall survival, 12.8% TP53 mutant vs 42.5% TP53 wild-type; P < .001) (Figure 2A). Because of the molecular homogeneity of mutant TP53 AML and MDS-EB, we investigated whether the AML or MDS-EB status associated with survival. No difference in outcome was observed between the AML and MDS-EB mutant TP53 subgroups (P = .549) (Figure 2B). All our findings indicate that mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB represents a homogeneous group and is therefore considered a singular entity in the following analysis.

Overall survival of patients with AML and MDS-EB (n = 2200). (A) Overall survival of AML/MDS-EB patients by the ELN 2017 risk classification. Patients in the adverse risk category are segregated by TP53 wild-type and TP53 mutant. (B) Overall survival of AML and MDS-EB disease classification at diagnosis stratified according to patients with TP53 wild-type and TP53 mutant.

Overall survival of patients with AML and MDS-EB (n = 2200). (A) Overall survival of AML/MDS-EB patients by the ELN 2017 risk classification. Patients in the adverse risk category are segregated by TP53 wild-type and TP53 mutant. (B) Overall survival of AML and MDS-EB disease classification at diagnosis stratified according to patients with TP53 wild-type and TP53 mutant.

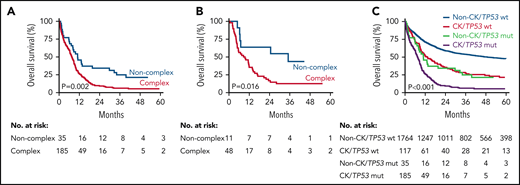

We performed survival analysis to evaluate the relationship of molecular characteristics and cytogenetic aberrations to outcome in mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB. Mono-allelic mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB had a similar dismal survival compared with its bi-allelic counterpart (P = .327) (Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 5). Neither the number of TP53 mutations (Figure 3B) nor aberrations involving chromosome 17 (supplemental Figure 6) associated with altered outcome in patients with mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB. Concurrent mutations conferred limited but detectable survival benefit (Figure 3C), whereas the presence of specific concurrent mutations provided no further survival advantage (supplemental Figure 7). Clone size, realized by taking decreasing TP53 mutation VAF thresholds and continuous modeling per 10% VAF, was investigated for impact on outcome. None of the mutant TP53 VAF thresholds significantly associated with survival: VAF 50% (P = .990); VAF 40% (P = .257); VAF 30% (P = .064); VAF 20% (P = .189); VAF 10% (P = .161); and VAF 5% (P = .226) (supplemental Figure 8A-F) (hazard ratio per 10% VAF, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.99-1.09; P = .141). Hence, the molecular characteristics of mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB did not evidently relate to treatment outcome.

Overall survival of molecular characteristics in mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB (n = 230). Overall survival of TP53 mutant allelic status (mono-allelic versus bi-allelic) (A), the number of TP53 mutations (B), and the presence or absence of concurrent mutations (C).

Overall survival of molecular characteristics in mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB (n = 230). Overall survival of TP53 mutant allelic status (mono-allelic versus bi-allelic) (A), the number of TP53 mutations (B), and the presence or absence of concurrent mutations (C).

In line with previous work, we confirmed that CK associates with reduced survival in TP53 mutant AML/MDS-EB (2-year overall survival, 9% CK vs 34% non-CK; P = .002), regardless of type of consolidation therapy (Figure 4).9,10 However, the overall survival of patients with non-CK TP53 mutant AML/MDS remains poor. Because of strong association of CK with all mutant TP53 molecular characteristics, no further stratification was feasible among patients with AML/MDS-EB with CK (supplemental Table 1). Of note, CK AML/MDS-EB with wild-type TP53 appeared to have a significantly improved outcome in our cohort of 2200 AML/MDS-EB cases as compared with CK in the context of mutant TP53 (Figure 4C), indicating that the presence of mutant TP53 at diagnosis defines a separate CK entity.

Overall survival of patients with AML/MDS-EB by CK. Overall survival of patients with mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB by CK (n = 220) (A) and for mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB patients who received allogeneic HSCT (n = 59) (B). Of note, the survival time starts at the date of transplant. (C) Overall survival of patients with AML/MDS-EB by CK and mutant TP53 status (n = 2101).

Overall survival of patients with AML/MDS-EB by CK. Overall survival of patients with mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB by CK (n = 220) (A) and for mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB patients who received allogeneic HSCT (n = 59) (B). Of note, the survival time starts at the date of transplant. (C) Overall survival of patients with AML/MDS-EB by CK and mutant TP53 status (n = 2101).

Sensitivity analysis, performed to identify potential treatment modification within trial protocols, yielded no significant interactions. Similar results were obtained when elderly patients with AML were excluded (data not shown).

Molecular minimal residual disease in mutant TP53 AML

Detection of molecular MRD is an important prognostic marker in AML.22-24 We performed deep targeted sequencing on complete morphological remission bone marrow samples from 62 patients with mutant TP53 AML to assess molecular MRD. Mutant TP53 is often the only suitable marker for molecular MRD detection because the prevalence of concurrent mutations at diagnosis is relatively low and most concurrently mutated genes may associate with antecedent clonal hematopoiesis (DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1) rather than residual leukemia (Figure 1). In total, 45 of 62 patients with AML/MDS-EB had detectable TP53 mutations in CR, for which the status did not associate with overall survival (P = .653) (Figure 5).

Overall survival of patients with AML/MDS-EB by TP53 mutations detected in CR (n = 62).

Overall survival of patients with AML/MDS-EB by TP53 mutations detected in CR (n = 62).

Discussion

Substantial heterogeneity within the mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB subgroup on a clinical and molecular level precludes the exact assessment on prognostic impact for individual patients with AML/MDS-EB. Here, we report the detailed molecular characterization of mutant TP53 in a large cohort of patients with AML and MDS-EB. No significant differences in the distribution of TP53 molecular characteristics and outcome between patients with AML and MDS-EB were observed. In fact, the 5-year overall survival of patients with mutant TP53 AML and MDS-EB in our study is similar to others.13 Mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB represents a molecular homogeneous group with distinct clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes. Therefore, we propose that mutant TP53 MDS-EB and AML should be considered a single entity, regardless of the requisite blast percentage at diagnosis.

Recent studies revealed important associations of TP53 mutant allelic status and mutant TP53 clone size with a more favorable outcome for patients with MDS and AML.5,13,15 These studies established significant associations and interactions of TP53 mutant allelic status and mutant TP53 clone size with CK. Remarkably, in our study based on a substantial number of patients with mutant TP53 AML and MDS-EB undergoing standard induction chemotherapy, we did not reveal an association between any of the TP53 molecular characteristics and survival. Although the distribution of molecular characteristics and outcome of mutant TP53 AML and MDS-EB in HOVON-SAKK clinical trials is comparable to other clinical trials, our analysis did not include low-risk MDS patients who often associate with non-CK.5,13 It is thought that the presence of wild-type TP53 is critical for maintaining chromosomal stability. During progression from MDS to high-risk MDS-EB or AML, mutant TP53 clones often become bi-allelically mutated and genomically unstable, which is reflected by the strong association between bi-allelic TP53 mutants and CK in our study. However, some patients with mono-allelic mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB also had CK. In 8 (2 non-CK and 6 CK) of 24 patients with mono-allelic mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB in whom high-quality DNA was available, we indeed confirmed, by SNP array analyses, the presence of uniparental disomy or focal 17p deletions that had been missed with conventional cytogenetics. Those patients can easily be misclassified as having mono-allelic TP53 mutation. Reallocation of these 8 patients with mono-allelic mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB to the mutant TP53 bi-allelic group did not affect our results (data not shown). Additional studies are required to investigate whether other (epigenetic) mechanisms are affecting the wild-type TP53 allele in mono-allelic cases without copy number alterations. Altogether, our results indicate that further stratification by the molecular characteristics of mutant TP53 appears to be less relevant when patients have progressed to MDS-EB or AML.

Although molecular MRD has prognostic value for predicting impending relapse in AML/MDS-EB,22-24 we did not observe such association in mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB. Despite using deep sequencing, which revealed MRD in most cases, molecular MRD detection in mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB did not yield prognostic value. It is conceivable that all patients with mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB achieving CR have MRD, sometimes at levels undetectable with current NGS approaches. In fact, the high relapse rates in patients with AML/MDS-EB without detectable mutant TP53 MRD in CR illustrates the critical role of mutant TP53 in chemotherapeutic response and implies that small refractory clones are present below our NGS detection limit.7 Although concurrent mutations are present in mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB, mutant TP53 itself appeared to be exclusive in half of the patients. Of note, most concurrent mutations are known contributors of age-related clonal hematopoiesis, in which we and others previously showed lack of prognostic significance.25,26 Although the applicability of molecular MRD detection in patients with mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB in our study is limited, future clinical trials with new drugs and other quantified MRD endpoints may benefit from molecular MRD detection based on mutant TP53.

Although very poor, better overall survival is observed in a minority of patients with AML/MDS-EB with non-CK mutant TP53. Possible explanations for the improved outcome in selected cases may be the enrichment of single TP53 mutations with low VAFs as well as higher frequencies of concurrent mutations in this group, indicating that mutant TP53 in these cases may represent clonal hematopoiesis rather than subclonal disease. Previous work in therapy-related AML indicates that mutant TP53 will eventually be the founding clone7; however, additional studies, including those involving relapse of patients with non-CK mutant TP53, are needed to demonstrate that mutant TP53 may be responsible for early relapse. Nevertheless, whether patients with mono-allelic non-CK mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB have better outcome requires additional investigations on larger numbers of patients.

In conclusion, from a clinical and molecular perspective, we propose to consider mutant TP53 AML/MDS-EB a distinct disease entity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participating centers of the Dutch–Belgian Cooperative Trial Group for Hematology–Oncology (HOVON) and Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK), where the clinical trials that formed the basis for this study were conducted; Eric Bindels for performing next-generation sequencing; Remco Hoogenboezem for assisting with bioinformatics; and Egied Simons for assisting with preparation of the figures (Erasmus University Medical Center).

This work was supported by grants from the Dutch Cancer Society “Koningin Wilhemina Fonds” (2020-12507). A.S.A.A.H. is a recipient of a PhD scholarship from the Ministry of Health of the Sultanate of Oman.

Authorship

Contribution: T.G., A.S.A.A.H., B.L., M.J.-L., and P.J.M.V. designed the study and wrote the manuscript with input from the remaining authors; and all authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and analysis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Peter J. M. Valk, Department of Hematology, Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam, Nc806, Wytemaweg 80, 3015 CN Rotterdam Z-H, The Netherlands; e-mail: p.valk@erasmusmc.nl.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

REFERENCES

Author notes

T.G. and A.S.A.A.H. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal