Key Points

High-molecular-weight kininogen deficiency in mice protects against APAP-induced hepatotoxicity.

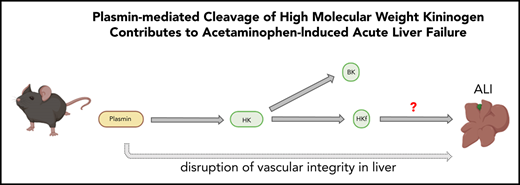

Plasmin-mediated cleavage of high molecular weight kininogen enhances APAP-induced hepatotoxicity independently of bradykinin signaling.

Abstract

Acetaminophen (APAP)-induced liver injury is associated with activation of coagulation and fibrinolysis. In mice, both tissue factor–dependent thrombin generation and plasmin activity have been shown to promote liver injury after APAP overdose. However, the contribution of the contact and intrinsic coagulation pathways has not been investigated in this model. Mice deficient in individual factors of the contact (factor XII [FXII] and prekallikrein) or intrinsic coagulation (FXI) pathway were administered a hepatotoxic dose of 400 mg/kg of APAP. Neither FXII, FXI, nor prekallikrein deficiency mitigated coagulation activation or hepatocellular injury. Interestingly, despite the lack of significant changes to APAP-induced coagulation activation, markers of liver injury and inflammation were significantly reduced in APAP-challenged high-molecular-weight kininogen-deficient (HK−/−) mice. Protective effects of HK deficiency were not reproduced by inhibition of bradykinin-mediated signaling, whereas reconstitution of circulating levels of HK in HK−/− mice restored hepatotoxicity. Fibrinolysis activation was observed in mice after APAP administration. Western blotting, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and mass spectrometry analysis showed that plasmin efficiently cleaves HK into multiple fragments in buffer or plasma. Importantly, plasminogen deficiency attenuated APAP-induced liver injury and prevented HK cleavage in the injured liver. Finally, enhanced plasmin generation and HK cleavage, in the absence of contact pathway activation, were observed in plasma of patients with acute liver failure due to APAP overdose. In summary, extrinsic but not intrinsic pathway activation drives the thromboinflammatory pathology associated with APAP-induced liver injury in mice. Furthermore, plasmin-mediated cleavage of HK contributes to hepatotoxicity in APAP-challenged mice independently of thrombin generation or bradykinin signaling.

Introduction

Acetaminophen (APAP; paracetamol, Tylenol) overdose is the leading cause of drug-induced acute liver failure (ALF)1 and is responsible for >78 000 emergency department visits annually in the United States.2 Hepatocellular injury is initiated when excess APAP is metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes into the reactive intermediate N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine,3-6 which generates protein adducts,7 leading to oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction.8,9 Permeabilization of the mitochondrial membrane and cessation of adenosine triphosphate synthesis ultimately results in hepatocyte death that can progress to ALF.10

Several reports in mouse models indicate that anticoagulation mitigates the early phase of APAP-induced hepatotoxicity,11-13 but paradoxically, coagulation factors participate in liver regeneration during the recovery phase.14 Specifically, genetic reduction of tissue factor expression or pharmacologic inhibition of thrombin activity results in significant reduction of liver injury early after APAP ingestion.11,13 The pathologic contribution of thrombin during the early stages of APAP-induced ALF is in part mediated by activation of protease-activated receptors13 and also requires fibrin(ogen).11,12 However, during the repair phase after APAP overdose, fibrin(ogen) is required for leukocyte-mediated liver repair.14

Fibrinolysis is principally initiated by tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)-mediated cleavage of plasminogen to generate plasmin.15 Recently, it was reported that animals deficient in plasminogen are less susceptible to APAP-induced liver toxicity,12 and mechanisms are currently being investigated.16 Interestingly, it has been shown that plasminogen activators may contribute to APAP-induced liver injury independently of fibrin(ogen).12 In addition to being the main effector enzyme of the fibrinolytic system, plasmin has been shown to have other functions, including cleavage of high-molecular-weight kininogen (HK).17-19 However, data showing the in vivo relevance of this observation are missing.

HK circulates in complex with factor XI (FXI) or prekallikrein (PK)20 and serves as a nonenzymatic cofactor for activation of both proteins by FXIIa,21 which leads to 2 events: (1) propagation of coagulation via activation of FXI; and (2) activation of plasma PK with subsequent kallikrein (PKa)-mediated cleavage of HK, resulting in the release of bradykinin (BK) and cleaved HK fragments.22 BK is a potent inflammatory mediator and vasodilator that exerts its biological effects through 1 of 2 G protein–coupled receptors, BK receptor 1 (BKr 1) and BK receptor 2 (BKr 2).23,24

Several studies have suggested that plasmin plays an active role in the pathogenesis of hereditary angioedema, an inflammatory disorder mediated by HK cleavage, independently of its fibrinolytic function.25,26 Indeed, antifibrinolytic agents such as e-amino caproic acid are used in the treatment of this disorder.27 Furthermore, the link between plasminogen activation and HK cleavage has been invoked to explain the inflammatory side effects of fibrinolytic therapy, usually presenting as anaphylaxis or angioedema.28,29 Activation of fibrinolysis is well documented during ALF.30-33 Thus, in view of evidence linking the contact pathway and fibrinolysis, the current study was undertaken to investigate if these pathways contribute to the pathology observed in a mouse model of APAP-induced liver injury.

Experimental procedures

Human subjects

Study subjects who participated in the Acute Liver Failure Study Group Registry have been described.34 All study patients met criteria for ALF as defined previously.35 The etiology of ALF as APAP overdose was initially identified by the study site investigator and adjudicated by the ALF Study Group Causality Committee.36 Plasma samples were collected in citrated Vacutainers (4 mL) on admission, processed, and stored at the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Repository at −80°C until used in the current studies. Consent was provided by the patients’ legal next-of-kin. Institutional review boards of each participating institution approved the ALF Study Group Registry and Biorepository.

Mice

All studies were performed in male mice, 10 to 14 weeks of age. Wild-type (WT) C57Bl/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). FXII-deficient (FXII−/−) animals have been previously described.37 FXI−/− mice were kindly provided by David Gailani.38 PK-deficient mice were developed at the Texas Genomic Institute and obtained from Alvin Schmaier.39 The characteristics of the Kng1 knockout animals have been previously described.40 Briefly, the mouse genome contains 2 homologous genes for kininogen; although only Kng1 was targeted for deletion, mixing coagulation studies, as well as western blotting, confirmed the absence of any kininogen in the plasma. Thus, these mice are heretofore referred to as HK−/−. Generation of the plasminogen-deficient mice was described previously.41 All experimental mice were on the same C57Bl/6J genetic background.

All animals were maintained at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in a facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International, according to the criteria of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.42 Mice were housed at an ambient temperature of 22°C with 14/10-hour light/dark cycles and were provided water and rodent chow ad libitum. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

APAP model

Mice had food withheld for ∼14 to 16 hours and then were given a sublethal dose of 400 mg/kg APAP43 (Sigma, Burlington, MA) or vehicle (sterile saline solution) by intraperitoneal injection, and food was returned immediately after the injection. At indicated times after APAP administration, mice were anesthetized using isoflurane (Eagle Eye Anesthesia, Jacksonville, FL). Blood was collected from the caudal vena cava into sodium citrate (3.8%) and centrifuged at 2000g for 20 minutes to isolate platelet-poor plasma. The liver was removed and washed with sterile saline. The left lobe was removed and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 24 to 36 hours.

Sample analysis

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry methods were used to determine a liver injury score and perform neutrophil staining. Western blot analysis was used to determine HK cleavage. A custom mouse multiplex assay was used to detected plasma cytokine levels. Detailed information is provided in the supplemental Material (available on the Blood Web site).

Clinical chemistry

Plasma levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were determined by using a commercially available reagent (Infinity ALT, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Mouse plasma was diluted 10-fold prior to assay. Data were acquired by using a Synergy H1 Plate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT) using Gen5 software version 3.08.

Plasma enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

Active tPA was quantified by using a kit from Molecular Innovations (Novi, MI). Mouse plasmin-α2 antiplasmin (PAP) complexes were detected by using a kit from Cusabio (College Park, MD). Human PAP complexes were detected by using an assay obtained from DiaPharma (West Chester, OH). Plasma thrombin-antithrombin (TAT) levels were determined by using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL). All assays were performed according to the manufacturers’ specifications with no modification. BK assay was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY) and conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Assays detecting total HK levels and cleaved HK levels have been previously described.44 Assays detecting complexes of FXIIa, FXIa, and PKa, with their respective serpins, were developed in-house.45

Clot lysis time

The detailed methodology of the tPA resistance assay was recently described.46 In brief, coagulation and fibrinolysis were simultaneously initiated by the addition of tissue factor, Ca2+, and tPA to platelet-free plasma. The optical density changes were recorded over 24 hours, at which point the test was terminated. The time from 50% maximal clotting to 50% lysis was defined as the clot lysis time.

Mass spectrometry

Samples were spotted (0.1 µL per spot) on the MALDI target and calibrated with the peptide calibration mixture 4700 (AB Sciex, Concord, ON, Canada). The matrix used was α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid. Samples were analyzed by using the Reflector Positive Ion Mode within a mass range of 800 to 4000 m/z. Spectra were collected by using an AB Sciex 5800 MALDI-TOF/TOF housed in the UNC Proteomics Core Facility. Spectra were analyzed by using Data Explorer version 4.5 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Statistical analysis

Comparison of 2 groups was performed by using the Student t test. Comparison of ≥3 groups was performed by using 1- or 2-way analysis of variance, as appropriate, and the Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test. Data are displayed as mean ± standard error of the mean. If data failed to indicate a normal distribution, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare means. A value of P < .05 confers statistical significance. All calculations were performed by using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Deficiency of FXII or FXI does not protect against APAP-induced acute liver injury

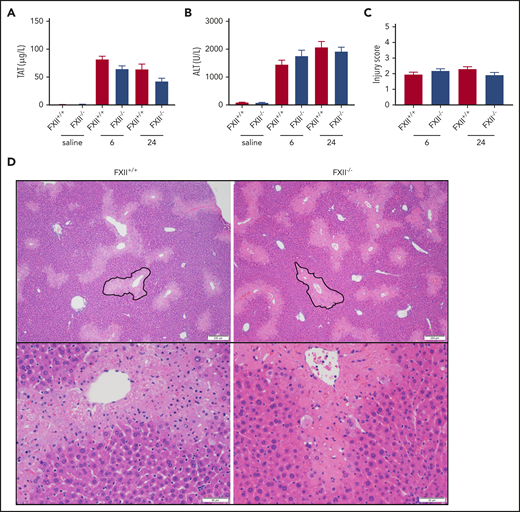

To determine if FXII deficiency affects in vivo thrombin generation in a mouse model of APAP-induced acute liver injury, we measured plasma levels of TAT complexes. Consistent with previous publications,11,47 plasma TAT levels increased at 6 and 24 hours after APAP administration in WT (FXII+/+) mice compared with saline-treated animals (Figure 1A). A similar increase was observed in FXII−/− mice at both time points, indicating that FXII does not significantly contribute to thrombin generation in this model. Because FXII is known to exert proinflammatory effects independently of its procoagulant activity,48 we analyzed the effect of FXII deficiency on liver injury. Compared with saline-treated mice, plasma ALT levels were significantly increased at 6 and 24 hours after APAP administration in FXII+/+ mice; however, FXII deficiency had no effect on ALT levels (Figure 1B). Furthermore, liver sections were evaluated by using a histopathologic scoring system (supplemental Table 1) in which reviewers were blinded to genotype, as well as software-aided necrotic area calculation (supplemental Figure 1). Consistent with the absence of any effect of FXII deficiency on plasma levels of ALT in APAP-challenged mice, no significant difference between FXII+/+ or FXII−/− mice was observed in any of these parameters, at either time point (Figure 1C-D; supplemental Figure 1A).

FXII deficiency does not protect against APAP toxicity. (A) Plasma concentration of TAT complexes at 6 and 24 hours post-APAP administration. (B) Plasma ALT activity, an assessment of hepatotoxicity. (C) Histologic scoring of liver pathology according to supplemental Table 1. (D) Representative photomicrographs of liver histology from FXII+/+ and FXII−/− mice at 24 hours after APAP treatment, ×40 and ×100 original magnification. A representative pericentral necrotic lesion is outlined in black. N = 18 to 19 mice per group, combined from 3 independent experiments. Saline samples collected at 24-hour time point (N = 6 mice per group). Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

FXII deficiency does not protect against APAP toxicity. (A) Plasma concentration of TAT complexes at 6 and 24 hours post-APAP administration. (B) Plasma ALT activity, an assessment of hepatotoxicity. (C) Histologic scoring of liver pathology according to supplemental Table 1. (D) Representative photomicrographs of liver histology from FXII+/+ and FXII−/− mice at 24 hours after APAP treatment, ×40 and ×100 original magnification. A representative pericentral necrotic lesion is outlined in black. N = 18 to 19 mice per group, combined from 3 independent experiments. Saline samples collected at 24-hour time point (N = 6 mice per group). Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Thrombin is known to activate FXI independently of FXIIa.49 To determine if thrombin-dependent feedback activation of FXI enhances thrombin generation in a mouse model of ALF, we examined the effect of FXI deficiency on plasma TAT levels in APAP-challenged mice. FXI deficiency had no significant effect on plasma TAT levels at 6 or 24 hours (supplemental Fig 2A). Similar to FXII-deficient animals, there was no significant difference in plasma levels of ALT between FXI+/+ and FXI−/− mice at 6 or 24 hours after APAP injection (supplemental Figure 2B). Furthermore, histologic analysis revealed that FXI deficiency had no effect on the injury score (supplemental Figure 1C-D) or the area of the necrotic lesion (supplemental Figure 1B).

HK but not plasma PK deficiency ameliorates hepatocellular injury induced by APAP

FXIIa not only activates FXI but also activates PK, which in turn cleaves HK. HK is not enzymatically active but functions as a cofactor for FXI and PK activation, such that HK deficiency can blunt contact-mediated thrombin generation.50 HK is also the precursor of the proinflammatory and vasodilatory molecule BK. Consistent with our observations in FXII−/− mice, there was no significant difference in plasma TAT or ALT levels between PK+/+ and PK−/− animals at 24 hours after APAP exposure (supplemental Figure 3A-B). Histologic analysis confirmed that there were no substantial differences in liver injury indices between PK+/+ and PK−/− mice (supplemental Figure 3C-D) as well as necrotic area (supplemental Figure 1C). Interestingly, however, despite the lack of a significant effect on APAP-induced thrombin generation measured according to plasma TAT levels (Figure 2A), plasma levels of ALT were significantly reduced in HK−/− mice compared with HK+/+ animals at both 6 and 24 hours after APAP administration (Figure 2B). Together, these data suggest that HK contributes to APAP-induced liver injury independently of thrombin generation or activation by PKa.

HK deficiency does not inhibit coagulation activation, but does ameliorate APAP-induced hepatotoxicity. (A) Plasma concentration of TAT complexes at 6 and 24 hours post-APAP administration. (B) Plasma ALT activity. (C) Histologic scoring of liver pathology according to supplemental Table 1. (D) Representative photomicrographs of liver histology from HK+/+ and HK−/− animals at 24 hours after APAP treatment, ×40 and ×100 original magnification. A representative pericentral necrotic lesion is outlined in black. N = 26 to 30 mice per group, combined from 6 independent experiments. Saline samples collected at 24-hour time point. N = 9 to 10 mice per group. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

HK deficiency does not inhibit coagulation activation, but does ameliorate APAP-induced hepatotoxicity. (A) Plasma concentration of TAT complexes at 6 and 24 hours post-APAP administration. (B) Plasma ALT activity. (C) Histologic scoring of liver pathology according to supplemental Table 1. (D) Representative photomicrographs of liver histology from HK+/+ and HK−/− animals at 24 hours after APAP treatment, ×40 and ×100 original magnification. A representative pericentral necrotic lesion is outlined in black. N = 26 to 30 mice per group, combined from 6 independent experiments. Saline samples collected at 24-hour time point. N = 9 to 10 mice per group. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

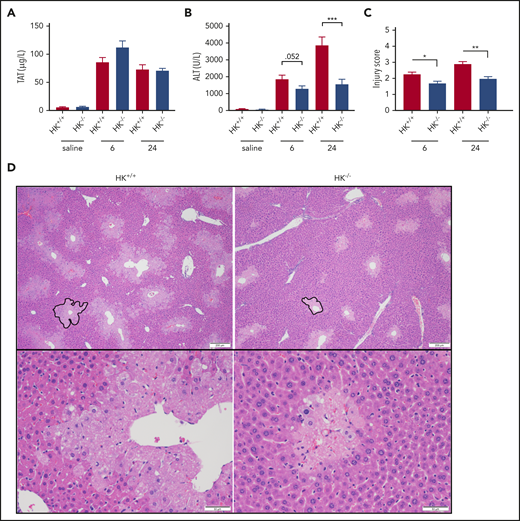

Histologic analysis also revealed a significant reduction of APAP-induced liver injury in HK−/− mice. Compared with HK+/+ mice, HK−/− animals exhibited a reduced injury score (Figure 2C-D) and necrotic area (supplemental Figure 1D-E). High-dose APAP results in generation of the reactive metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine, which can be neutralized by stored glutathione. The differences observed in HK−/− and HK+/+ animals could not be attributed to differences in APAP metabolism, as glutathione consumption and circulating APAP concentration at 2 hours were identical in each genotype (supplemental Figure 4). A significant reduction in the number of infiltrating neutrophils in the livers of HK−/− mice 24 hours after APAP overdose was also observed (Figure 3A-B). Given these findings, we also assayed circulating levels of candidate cytokines involved in neutrophil recruitment and inflammation. HK−/− animals had significantly less circulating interleukin 6 (IL-6) at 24 hours after APAP toxicity (Figure 3C). Moreover, other inflammatory and chemotactic cytokines, including IL-1β, macrophage inflammatory protein-1β, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, were significantly lower in HK−/− mice compared with HK+/+ control mice (Figure 3D-F, respectively). A comprehensive cytokine summary is provided in supplemental Table 2.

Neutrophil recruitment and inflammation are blunted in HK-deficient mice. (A) Representative photomicrographs from HK+/+ and HK−/− APAP-treated mice, ×40 original magnification, and digitally zoomed. Positive chromogenic peroxidase staining represents neutrophil infiltration in the necrotic areas of the liver, and no primary antibody (1° aby) is used as an assay control. (B) Quantification of neutrophils per field, average counts of positively stained neutrophils per three 40× fields per mouse. N = 18-19 mice per group, combined from 3 independent experiments. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. (C-F) Plasma concentration of cytokines as indicated; N = 12 to 13 mice per group. All data collected at 24 hours after APAP administration. *P < .05, ***P < .001, ****P < .001 vs HK+/+. G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; MIP-1β, macrophage inflammatory protein-1β.

Neutrophil recruitment and inflammation are blunted in HK-deficient mice. (A) Representative photomicrographs from HK+/+ and HK−/− APAP-treated mice, ×40 original magnification, and digitally zoomed. Positive chromogenic peroxidase staining represents neutrophil infiltration in the necrotic areas of the liver, and no primary antibody (1° aby) is used as an assay control. (B) Quantification of neutrophils per field, average counts of positively stained neutrophils per three 40× fields per mouse. N = 18-19 mice per group, combined from 3 independent experiments. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. (C-F) Plasma concentration of cytokines as indicated; N = 12 to 13 mice per group. All data collected at 24 hours after APAP administration. *P < .05, ***P < .001, ****P < .001 vs HK+/+. G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; MIP-1β, macrophage inflammatory protein-1β.

It has previously been shown that in the mouse model of APAP toxicity, pan-caspase inhibitors (to limit apoptosis) have no effect on liver injury.8,10 However, this question had never been addressed in the setting of HK deficiency. We therefore conducted staining for cleaved caspase 3 in the same liver sections used to determine the injury score in HK+/+ and HK−/− mice (supplemental Figure 5). There was no activity of caspase 3 that would suggest the presence of hepatocellular apoptosis.

Plasmin cleaves HK to release BK in vitro and ex vivo

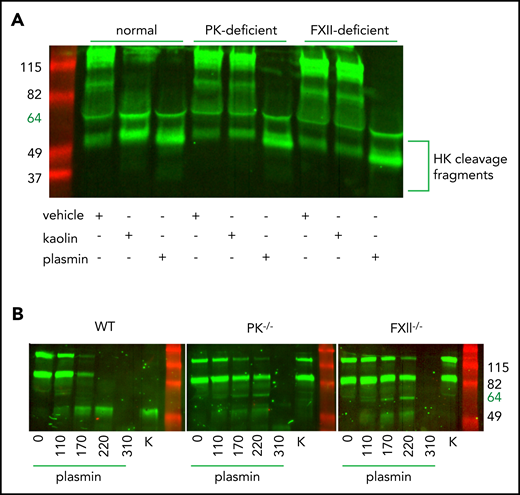

Canonical cleavage of HK by PKa generates bioactive HK fragments and the inflammatory nonapeptide BK.51 Lack of protection against APAP-induced ALF observed in PK−/− mice, together with strong attenuation of liver injury shown in HK−/− mice, suggested that HK cleavage is independent of PKa in this situation. It has been reported that HK can also be cleaved by plasmin in a buffer system.17 We therefore examined whether cleavage of plasma HK by plasmin occurs ex vivo. Plasma from normal, PK-deficient, or FXII-deficient human subjects (Figure 4A) was treated with either 116 µg/mL human plasmin, 200 µg/mL kaolin (a clay mineral that specifically activates FXII and subsequently PK), or saline vehicle, and incubated for 1 hour. Western blotting analysis showed efficient cleavage of HK in both plasmin- and kaolin-treated normal plasma (Figure 4A, lanes 1-3). Notably, plasmin-mediated cleavage of HK was independent of PK (Figure 4A, lanes 4-6) or FXII (Figure 4A, lanes 7-9), whereas kaolin-initiated cleavage required both proteins.

Plasmin cleaves HK independent of contact system activation in plasma. (A) Western blot of human plasma HK in a normal, PK-deficient, and FXII-deficient patient. Green = polyclonal antibody against the light chain of hHK. Cleavage products of HK (∼52 kDa) are shown after the addition of vehicle (saline +0.2% glycerol), kaolin (200 µg/mL), or plasmin (116 µg/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C. (B) Western blot of plasma HK in WT, PK−/−, and FXII−/− mice. Green = polyclonal antibody against the FXI- and PK-binding domain within the light chain of HK. Mouse plasma was treated with either plasmin (μg/mL) at indicated concentrations or kaolin 200 µg/mL (K) for 1 hour at 37°C.

Plasmin cleaves HK independent of contact system activation in plasma. (A) Western blot of human plasma HK in a normal, PK-deficient, and FXII-deficient patient. Green = polyclonal antibody against the light chain of hHK. Cleavage products of HK (∼52 kDa) are shown after the addition of vehicle (saline +0.2% glycerol), kaolin (200 µg/mL), or plasmin (116 µg/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C. (B) Western blot of plasma HK in WT, PK−/−, and FXII−/− mice. Green = polyclonal antibody against the FXI- and PK-binding domain within the light chain of HK. Mouse plasma was treated with either plasmin (μg/mL) at indicated concentrations or kaolin 200 µg/mL (K) for 1 hour at 37°C.

We next performed analysis of HK cleavage by various concentrations of mouse plasmin in plasma obtained from WT, PK-deficient, or FXII-deficient mice (Figure 4B). At the lowest plasmin concentration (110 µg/mL), the pattern of HK cleavage was similar in WT, PK−/−, and FXII−/− plasma, consistent with the results in human plasma showing contact pathway independent cleavage of HK by plasmin. Interestingly, higher plasmin concentrations (170 and 220 µg/mL) led to further processing of HK in WT plasma but not in FXII- or PK-deficient plasma. This result suggests that under these experimental conditions, the contact system is required for efficient cleavage of HK that most likely is initiated by plasmin-dependent activation of FXII.52 However, further increase of plasmin concentration beyond physiological levels (310 µg/mL) overcomes the requirement for FXII and results in a nonspecific cleavage of HK.

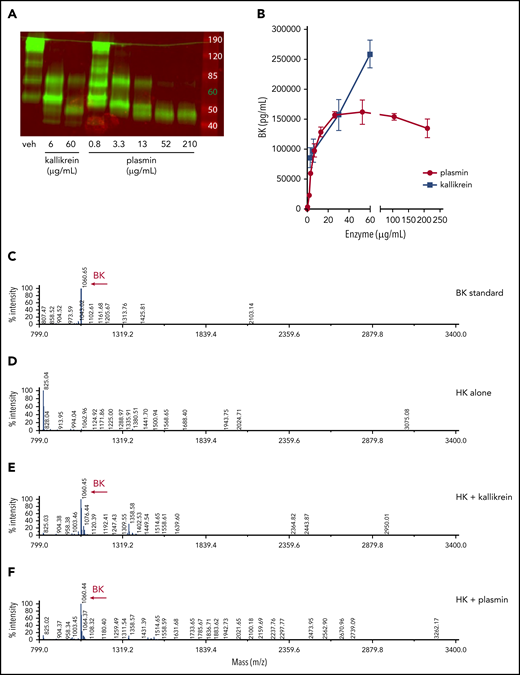

To determine if plasmin-mediated cleavage of HK results in the release of BK, recombinant human HK (hHK), at normal physiological concentrations (80 µg/mL), was exposed to various concentrations of human plasmin or PKa for 1 hour. HK cleavage was ascertained by western blot analysis (Figure 5A), and BK generation was assayed by ELISA (Figure 5B). Both plasmin and PKa led to the release of BK. Plasmin-mediated release of BK plateaued at concentrations >60 µg/mL, whereas concentration-dependent PKa-mediated cleavage was observed over the entire concentration range. Although the BK ELISA is widely accepted for quantification, it is possible that other peptides containing the BK sequence were detected, given that the assay contains a single antibody (and detection of epitopes often requires a minimum of 5-8 amino acids53 ). We therefore used mass spectrometry to identify peptide fragments following enzymatic processing of HK. The BK standard was calculated at 1060.6 m/z (Figure 5C). No BK peptide was detected in the purified HK sample (Figure 5D). Cleavage of HK by PKa produced a predominant peptide mass of 1060.4 m/z (Figure 5E). Similarly, HK cleavage by plasmin also produced a major peptide mass of 1060.4 m/z, indicating BK generation (Figure 5F).

Plasmin cleaves HK to release BK in buffer. (A) Western blot depicting cleavage pattern of purified hHK enzymatically processed in vitro. The enzymatic concentration of PKa or plasmin, or vehicle (veh) control, is indicated below each lane, and incubation proceeded for 1 hour at 37°C. (B) Concentration of BK released in an enzymatic buffer system, measured by using ELISA. HK 80 µg/mL was incubated for 1 hour with either PKa or plasmin at indicated concentrations. Error bars represent standard deviation from the mean. (C) Mass spectra of BK standard (250 µg/mL). (D) Mass spectra of purified HK (800 µg/mL). (E) Mass spectra of HK (800 µg/mL) incubated with pKA (150 µg/mL) for 1 hour. (F) Mass spectra of HK (800 µg/mL) incubated with plasmin (150 µg/mL) for 1 hour. Molecular mass of 1060 interpreted as BK peptide.

Plasmin cleaves HK to release BK in buffer. (A) Western blot depicting cleavage pattern of purified hHK enzymatically processed in vitro. The enzymatic concentration of PKa or plasmin, or vehicle (veh) control, is indicated below each lane, and incubation proceeded for 1 hour at 37°C. (B) Concentration of BK released in an enzymatic buffer system, measured by using ELISA. HK 80 µg/mL was incubated for 1 hour with either PKa or plasmin at indicated concentrations. Error bars represent standard deviation from the mean. (C) Mass spectra of BK standard (250 µg/mL). (D) Mass spectra of purified HK (800 µg/mL). (E) Mass spectra of HK (800 µg/mL) incubated with pKA (150 µg/mL) for 1 hour. (F) Mass spectra of HK (800 µg/mL) incubated with plasmin (150 µg/mL) for 1 hour. Molecular mass of 1060 interpreted as BK peptide.

BK signaling has no effect on APAP-induced acute liver injury

Incubation of WT mouse plasma ex vivo with mouse plasmin resulted in BK generation, although the levels of BK were lower compared with those observed in mouse plasma activated by kaolin (supplemental Figure 6A). Moreover, plasmin-mediated generation of BK was observed in FXII-deficient plasma, suggesting BK production did not require the entirety of the contact system. Together, these data show that plasmin-mediated cleavage of HK results in the release of BK and generation of HK fragments in a buffer system as well as in plasma. These data are consistent with the observations that the fibrinolytic system can drive BK production.54,55 To assess if BK signaling contributes to liver injury in the APAP toxicity model, a pharmacologic inhibitor of the BKr 2, bradyzide, was used, as well as mice deficient in BKr 2 or both BKr 1 and BKr 2. Mice given bradyzide exhibited no difference in liver injury, as indicated by similar ALT levels in plasma (supplemental Figure 6B). Furthermore, deletion of BKr 2 alone (supplemental Figure 6C) or both BKr 1 and BKr 2 (supplemental Figure 6D) failed to protect mice from APAP-induced liver injury. Collectively, these data indicate that although plasmin is capable of cleaving HK to produce BK, BK signaling through BKr 1 and BKr 2 is not a mediator of the early phase of APAP-induced liver injury.

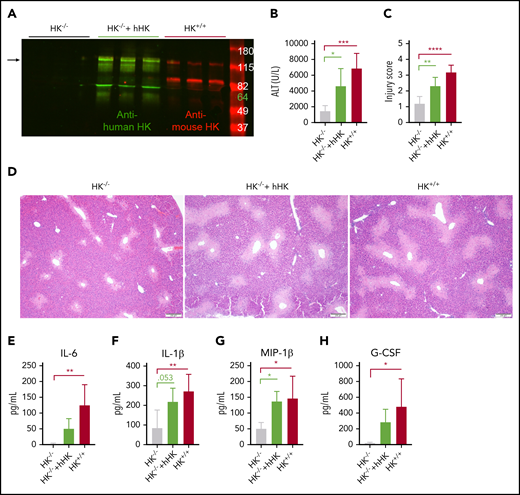

Reconstitution of HK restores liver injury in APAP-challenged HK−/− mice

Domains of HK other than BK have been shown to have biological activity.51 Our findings with BK inhibition and BKr deficiency showed that an alternative mechanism was responsible for the reduced injury in HK−/− mice. To confirm that protection in the HK−/− mice was specifically due to the absence of HK, we reconstituted HK−/− mice with hHK before APAP challenge, similar to previous studies.56 Two-color western blotting was performed to confirm that hHK was circulating in mouse plasma at the time of tissue collection (Figure 6A). Animals repleted with hHK exhibited a significant increase in circulating ALT above that seen in HK−/− mice (Figure 6B). Histopathologic analysis revealed that supplementation with hHK increased the injury score (Figure 6C) and the size of the necrotic lesion almost to the same extent as seen in HK+/+ mice (Figure 6D). Although repletion with hHK did not entirely restore the levels of IL-6 (Figure 6E), levels of other cytokines were elevated (Figure 6F-H; supplemental Table 3). Further evidence that phenotypic restoration was due to HK cleavage included in vitro analysis that mouse PKa and plasmin are both capable of cleaving hHK (supplemental Figure 7). These data, together with the results from BKr-deficient mice, strongly suggest that a product of HK cleavage, other than BK, is responsible for liver injury.

HK reconstitution exacerbates liver injury. (A) Western blot of plasma HK in deficient (HK−/−), reconstituted (HK−/− + hHK), and sufficient (HK+/+) mice. Green = polyclonal antibody against the light chain of hHK. Red = polyclonal antibody against the FXI- and PK-binding domain within the light chain of mouse HK. Arrow indicates full-length HK (∼120 kDa). (B) Circulating levels of ALT in plasma from HK-deficient animals, HK-deficient animals reconstituted with hHK, and HK-sufficient animals. (C) Injury score calculated based on criteria in supplemental Table 1, three 100× fields per mouse. (D) Representative photomicrographs indicating necrotic area in HK−/−, HK−/− + hHK, and HK−/− mice. (E-H) Quantitation of plasma concentration of cytokines as indicated. N = 6 mice per group. All data collected at 24 hours after APAP administration. Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; MIP-1β, macrophage inflammatory protein-1β.

HK reconstitution exacerbates liver injury. (A) Western blot of plasma HK in deficient (HK−/−), reconstituted (HK−/− + hHK), and sufficient (HK+/+) mice. Green = polyclonal antibody against the light chain of hHK. Red = polyclonal antibody against the FXI- and PK-binding domain within the light chain of mouse HK. Arrow indicates full-length HK (∼120 kDa). (B) Circulating levels of ALT in plasma from HK-deficient animals, HK-deficient animals reconstituted with hHK, and HK-sufficient animals. (C) Injury score calculated based on criteria in supplemental Table 1, three 100× fields per mouse. (D) Representative photomicrographs indicating necrotic area in HK−/−, HK−/− + hHK, and HK−/− mice. (E-H) Quantitation of plasma concentration of cytokines as indicated. N = 6 mice per group. All data collected at 24 hours after APAP administration. Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; MIP-1β, macrophage inflammatory protein-1β.

Plasminogen deficiency prevents HK cleavage in the liver of APAP-challenged mice

In vitro studies showed that plasmin can generate HK cleavage products. However, we had yet to associate HK cleavage with liver injury. Activation of the fibrinolytic system has been previously described in mice challenged with APAP, and plasminogen deficiency has been reported to provide significant protection in this model.16 Consistent with these observations, plasma concentrations of active tPA (supplemental Figure 8A) and PAP complexes (supplemental Figure 8B) were significantly elevated at 6 and 24 hours after APAP administration in mice. Knowing that the 6-hour time point likely had the highest level of plasmin activity, western blot analysis was conducted on liver homogenates to assess HK cleavage. We observed a cleaved HK product with a molecular weight of ∼60 kDa (supplemental Figure 9A) in the livers of APAP-treated mice, whereas this fragment was not detected in saline-treated control mice (indicated with arrow). An additional ∼52 KDa fragment was observed at increased intensity. Curiously, HK−/− mice exhibited a significant reduction in PAP complexes at 6 hours (supplemental Figure 9C) that was associated with reduction of tPA levels in HK−/− mice (supplemental Figure 9B), suggesting that reduction of the proinflammatory state in APAP-challenged HK−/− mice (Figures 3C-F, 6E-H) can affect tPA-mediated plasmin generation.

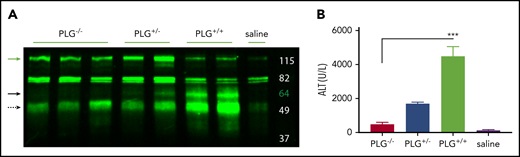

To ascertain if plasmin can cleave HK in vivo, we challenged plasminogen-deficient (PLG−/−), heterozygous (PLG+/−), and plasminogen-sufficient (PLG+/+) mice with APAP and assessed HK cleavage and hepatocellular injury. Western blot revealed HK cleavage (∼60 kDa) in PLG+/+ mice, which was reduced in PLG+/− mice and absent in PLG−/− mice (Figure 7A, solid black arrow). Moreover, plasminogen deficiency significantly reduced APAP-induced liver injury, indicated by a reduction in serum ALT activity (Figure 7B). A highly significant positive correlation was observed between plasma levels of ALT and HK cleavage fragments (R = 0.85; P = .0011). In aggregate, these data suggest that an HK cleavage product resulting from plasmin activity contributes to APAP hepatotoxicity.

Plasminogen presence correlates with HK cleavage in situ. (A) Western blot of mouse liver homogenate after APAP exposure. Green = polyclonal antibody against the FXI- and PK-binding domain within the light chain of mouse HK. PLG knockout (−/−), heterozygous (+/−), and WT (+/+), and vehicle (saline) animals as indicated. Green arrow indicates full-length HK (∼120 kDa). Solid black arrow indicates plasmin-cleaved HK (∼60 kDa). Dashed black arrow indicates a cleavage product that increases with plasmin presence (∼52 kDa). (D) Plasma levels of ALT in PLG−/−, PLG+/−, PLG+/+, or saline vehicle mice 24 hours after APAP exposure. N = 6 mice per group. ***P < .001.

Plasminogen presence correlates with HK cleavage in situ. (A) Western blot of mouse liver homogenate after APAP exposure. Green = polyclonal antibody against the FXI- and PK-binding domain within the light chain of mouse HK. PLG knockout (−/−), heterozygous (+/−), and WT (+/+), and vehicle (saline) animals as indicated. Green arrow indicates full-length HK (∼120 kDa). Solid black arrow indicates plasmin-cleaved HK (∼60 kDa). Dashed black arrow indicates a cleavage product that increases with plasmin presence (∼52 kDa). (D) Plasma levels of ALT in PLG−/−, PLG+/−, PLG+/+, or saline vehicle mice 24 hours after APAP exposure. N = 6 mice per group. ***P < .001.

We also analyzed the effect of FXII deficiency on HK cleavage in the liver of APAP-challenged mice. Results showed that cleavage of HK was still observed under these conditions; however, the intensity of the cleaved band was reduced compared with that observed in the liver of control WT mice (supplemental Figure 10). These data suggest that FXII(a) may partially contribute to HK cleavage in the liver of APAP-challenged mice; however, partial attenuation of HK cleavage is not sufficient to exert significant protection against APAP-mediated injury.

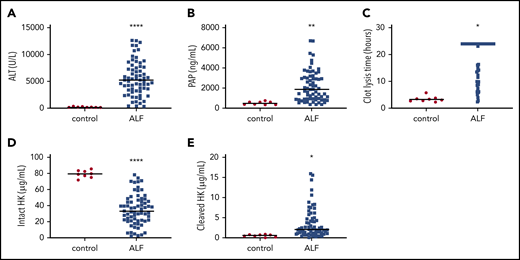

Fibrinolytic activation and HK cleavage in patients with ALF

Our data in APAP-challenged mice prompted us to determine whether plasmin generation and HK cleavage are increased in patients with ALF caused by APAP overdose. Plasma ALT activity and PAP complexes were increased in patients with ALF (Figure 8A-B), and, in agreement with prior studies,57 tPA-mediated clot lysis time was also prolonged (Figure 8C), indicating consumption of plasminogen. To determine if HK cleavage is detectable in plasma from patients with ALF, we performed ELISAs specific for intact or cleaved HK in plasma. Patients with ALF exhibited a significantly reduced concentration of circulating intact HK (Figure 8D), accompanied by a significant increase in cleaved HK (Figure 8E) compared with healthy control subjects. Plasma samples were also analyzed for activation of FXII, FXI, and PK by measuring concentrations of FXIIa, factor XIa, or PKa complexed with C1 esterase inhibitor (C1). No significant difference was observed in the levels of FXIIa:C1 or PKa:C1, whereas plasma levels of factor XIa:C1 were reduced (supplemental Table 4). Corroborating observations from the animal model, these results show enhanced plasmin generation and HK cleavage in the absence of contact pathway activation in humans with ALF caused by APAP overdose.

Activation of fibrinolysis and cleavage of HK in plasma from human patients with ALF. (A) Plasma ALT activity in normal individuals (control) and patients with ALF. (B) Circulating concentration of PAP complexes. (C) tPA-mediated clot lysis time. Longer times indicate reduced fibrinolytic capacity. (D) Plasma concentration of intact HK. (E) Plasma concentration of cleaved HK. N = 8 normal controls, 67 with ALF. Bars represent the sample mean. *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001.

Activation of fibrinolysis and cleavage of HK in plasma from human patients with ALF. (A) Plasma ALT activity in normal individuals (control) and patients with ALF. (B) Circulating concentration of PAP complexes. (C) tPA-mediated clot lysis time. Longer times indicate reduced fibrinolytic capacity. (D) Plasma concentration of intact HK. (E) Plasma concentration of cleaved HK. N = 8 normal controls, 67 with ALF. Bars represent the sample mean. *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001.

Discussion

Activation of coagulation is a prominent feature of experimental APAP-induced liver injury. Several animal studies have shown that thrombin contributes to the early phase of the injury.11-13,58 The activation of coagulation during APAP-induced hepatotoxicity is initiated by decryption of procoagulant properties of tissue factor expressed by hepatocytes.59 In contrast to the major contribution of the extrinsic coagulation pathway, the findings presented here show that deficiency of FXII or FXI had no significant effect on either thrombin generation or hepatotoxicity in APAP-challenged mice. Moreover, activation of FXII and FXI, measured by plasma levels of active enzyme:C1 complexes, was not increased in the cohort of patients with APAP-induced liver failure. Collectively, these results support the conclusion that the extrinsic but not the contact activation pathway is instrumental in the coagulation-mediated pathologies associated with APAP-induced hepatic injury in mice.

It is widely accepted that FXIIa-dependent generation of PKa leads to HK cleavage.48 In addition, it has been proposed that PKa generated independently of FXIIa can also cleave HK.60,61 Interestingly, we observed that a reduction in APAP-induced liver injury observed in HK−/− mice was not mirrored by a similar protection in FXII−/− or PK−/− mice. These data strongly suggest that the contribution of HK to the liver pathology in this model is independent of the other components of the contact pathway. In addition to PKa, several other enzymes have been shown to cleave HK in buffer systems.62-64 Among these other proteases, plasmin has been shown to directly cleave HK,18 as well as prime HK for subsequent cleavage by PKa.17 Our data indicated that: (1) plasmin can efficiently cleave HK in a purified system and plasma, with the subsequent release of BK and other HK fragments; and (2) there is a failure of HK cleavage in APAP-challenged plasminogen-deficient mice. Importantly, these findings establish for the first time that plasmin cleavage of HK occurs in vivo and suggests that this proteolytic event may promote downstream tissue injury. However, we also observed that a partial attenuation of HK cleavage in the liver of FXII−/− mice after APAP challenge was not accompanied by a significant attenuation of liver pathology. This could be explained simply by the possibility that reduced HK cleavage was insufficient to exert a protective effect. However, this observation, together with the fact that we did not identify the specific HK cleavage fragment(s) contributing to APAP-induced hepatotoxicity, raises the alternative hypothesis that it is simply the presence, and not necessarily the cleavage, of HK that contributes to injury severity in this model.

Plasmin is a serine protease that degrades the fibrin network within clots.15 It is generated by tPA- or urokinase-type plasminogen activator–mediated proteolysis of plasminogen, a protein predominantly synthesized in the liver.65 It has been previously shown that circulating plasmin activity increases during acute liver injury.31,32,66 Deficiency of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, the principal inhibitor of tPA, exacerbates liver injury in APAP-challenged mice.16,67 Importantly, inhibition of plasmin or genetic deficiency of plasminogen also attenuates hepatotoxicity in mice after APAP overdose.12,67 However, the mechanism of this protection has been unknown. Recent studies found that plasmin mediates liver injury, in part via degradation of the extracellular matrix and subsequent disruption of hepatic sinusoidal vascular integrity.16 Furthermore, plasmin-mediated activation of Kupffer cells may contribute to upregulation of proinflammatory cytokine expression during the early phase of APAP-induced liver injury in mice.68 However, given the protection from APAP-induced liver toxicity observed in plasminogen-deficient mice or in mice receiving tranexamic acid (an inhibitor of plasmin generation),12 it is very likely that multiple, nonoverlapping pathways mediate the pathologic effects of plasmin. Results from our study indicate that in addition to the mentioned mechanisms,16,68 plasmin-dependent cleavage of HK is a novel mechanism linking the fibrinolytic system with APAP-induced hepatotoxicity. We also showed that, depending on concentration, in vitro plasmin-mediated cleavage of HK can be contact pathway independent or dependent (Figure 4B). This intriguing observation raises the question about the local plasmin concentration generated in injured livers, which is currently unknown. Further studies are needed to determine whether the mechanism of HK cleavage in this situation is indeed dependent on the plasmin concentration.

Limited data exist regarding the production and role of BK in acute liver injury.69-71 Our in vivo findings using bradyzide or BKr knockout mice revealed no contribution of BK signaling through canonical receptors in acute APAP-induced liver injury. However, in vitro studies have shown that HK fragments can mediate cytokine release from mononuclear cells72 and modulate neutrophil activity.73 These observations are consistent with the reduced intra-hepatic neutrophil infiltration and reduction of plasma cytokine levels that we observed in HK−/− mice after APAP challenge. In aggregate, our data support the hypothesis that HK fragments other than BK contribute to APAP-induced inflammation. Domain 5 of HK is perhaps the best-characterized cleavage product, with multiple reports describing a role for this fragment as an angiogenesis inhibitor,74-76 an adhesion inbibitor,77,78 and an inhibitor of cancer metastasis,79,80 as well as an antimycotic81 and antibiotic.82 In addition, other domains of HK have been shown to inhibit calpain83,84 and other thiol proteases.85,86 Alternatively, it is possible that plasmin-cleaved HK could produce BK in vivo, which instead mediates its effects through non-canonical receptors such as TRPV1.87 However, TRPV1 has not been shown to contribute to toxicity in the mouse APAP model.88 Future studies into the possible bioactivity of the various plasmin-generated HK fragments are needed. Indeed, comprehensive, detailed analyses will be required to determine how they may contribute to toxicity in this model.

Use of the mouse model to resolve the apparent paradox that clotting is harmful during the early stages of APAP-induced liver injury,11,13 yet fibrinolytic activity is also harmful throughout the first 24 hours,14 presents a challenge. The relationship between injury and resolution seems dependent upon fibrin(ogen), which has been shown to exert a hepatoprotective function at later time points.12,14 Fibrin(ogen) deposition at injury sites is common, regardless of the inciting event or tissue specificity.89 However, use of ancrod (a defibrinogenating agent) or fibrinogen knockout animals exhibited no difference in APAP-induced liver injury at 24 hours compared with control animals.12 Liver repair is robust and occurs on a predictable time course in mice challenged with the dose used in this study. Although this setting recapitulates many features of acute APAP hepatotoxicity in humans, the mice do not develop ALF. Indeed, there is not yet evidence that mice challenged with APAP develop the sensitive yet “rebalanced” coagulation and fibrinolytic systems present in patients with ALF.90 Further study into the interplay of coagulation and fibrinolytic pathways in acute liver injury and liver failure is greatly needed. Emerging evidence suggests that proteolytic processing of HK and release of BK occur as the result of the mechanistically coupled processes of contact activation and plasmin activity.25 The current study shows that, much like the contact system independently cleaving HK via PKa, plasmin alone may be sufficient.

In summary, we have shown that HK contributes to APAP-induced acute liver injury independently of thrombin generation and activation of the contact pathway. Instead, we found that activation of the fibrinolytic system with subsequent plasmin generation mediates HK cleavage in APAP-challenged mice. The results of this study and others suggest that interruption of plasmin generation and subsequent HK cleavage (eg, by the use of tranexamic acid or by supplementation with α2-antiplasmin) may be protective in this form of acute liver injury.12 Animal models have shown modest protection with the use of tranexamic acid, albeit at high doses.12,16,68 However, we are not aware that antifibrinolytic therapy has been evaluated in APAP-induced ALF in humans, although tranexamic acid has been shown to resolve refractory bleeding in advanced liver disease.91,92 Identification of cleaved HK in human patients may also support future studies investigating the role of HK in ALF sequelae such as hepatic encephalopathy. Thus, although BK had no apparent role in mediating acute liver parenchymal injury, it is possible that BK generation may contribute to blood–brain barrier dysfunction complicating ALF.55 Moreover, BK antagonists have been used to block hemodynamic instability,93 a condition that is frequently present during ALF.94 Further studies evaluating the role of HK-derived inflammation in this scenario are warranted.

For original data, contact the corresponding authors (rafal_pawlinski@med.unc.edu or nigel_key@med.unc.edu).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dawud Hilliard and Stephanie Montgomery of the UNC Animal Histopathology Core. They also thank Emily Wilkerson, Laura Herring, and Nely Dicheva of the UNC Proteomics Core Facility, which is supported, in part, by a National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Core Support Grant (P30 CA016086) to the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. T.R. is supported by a grant from the German Research Society (SFB841, TP B8). R.T.S. and the US Acute Liver Failure Study Group received funding from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant U-01 58369). S.W. was supported by the NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (T32 HL007149). J.P.L. received funding from the NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK120289). R.P. (HL 142604, U01 HL117659) and N.S.K. (U01 HL117659, RO1 HL146226) were supported by grants from the NIH/NHLBI. Preliminary studies were funded by donations from a patient of R.T.S.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Authorship

Contribution: M.W.H. contributed to the study design, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; E.M.S., S.W., and A.I. performed experiments; R.M., T.R., M.J.F., K.R.M., S.S., Z.-L.C., and R.T.S. provided valuable reagents, mice, and human plasma samples; D.F.N., E.M.S., J.P.L., M.J.F., K.R.M., and R.T.S. provided conceptual insight and critically evaluated the manuscript; and N.S.K. and R.P. designed the study, analyzed the data, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Rafal Pawlinski, 116 Manning Dr, 8008C Mary Ellen Jones Bldg, CB #7035, Chapel Hill, NC 27514; e-mail: rafal_pawlinski@med.unc.edu; or Nigel S. Key, 116 Manning Dr, 8008B Mary Ellen Jones Bldg, CB #7035, Chapel Hill, NC 27514; e-mail: nigel_key@med.unc.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal