Abstract

The interplay of cancer cells and surrounding stroma is critical in disease progression. This is particularly evident in hematological malignancies that infiltrate the bone marrow and peripheral lymphoid organs. Despite clear evidence for the existence of these interactions, the precise repercussions on the growth of leukemic cells are poorly understood. Recent development of novel imaging technology and preclinical disease models has advanced our comprehension of leukemia-microenvironment crosstalk and has potential implications for development of novel treatment options.

Introduction

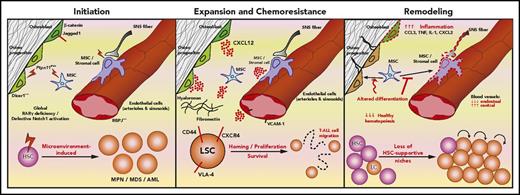

Leukemias are characterized by the aggressive nature of disease and poor response to therapy. Patients with leukemia often present with cytopenias resulting from disruption of normal hematopoiesis. This leads to complications due to bleeding and recurrent infections. Hematopoiesis is maintained by self-renewing hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) that reside in niches within the bone marrow (BM).1 The precise composition and function of these niches are still under intense investigation. Regardless, the biology of HSCs is thought to be regulated by a complex array of cell populations, including arteriolar2 and sinusoidal3 endothelial cells, mesenchymal stem cells (MSC),4 perivascular stromal cells,2,5 osteoblasts,6 sympathetic neurons,7 nonmyelinating Schwann cells,8 adipocytes,9 megakaryocytes,10,11 and regulatory T cells.12 It has been speculated that leukemia cells highjack13,14 and destroy15 HSC-supportive microenvironments, potentially shifting the equilibrium of microenvironments from a state that supports steady-state hematopoiesis in favor of conditions that instead lead to accelerated expansion of leukemic cells or even to leukemogenesis and development of chemoresistance. Thus, understanding the role of microenvironments in leukemia initiation, progression, and development of chemoresistance (Figure 1) is critical for development of novel therapeutic interventions.

The crosstalk between leukemic cells and the microenvironment. Several studies suggest a causative role of the BM microenvironment in leukemogenesis (Initiation), mediated by alterations of signaling pathways in specific cell types, involving, for example, β-catenin, Jagged1, Ptpn11, Dicer1 in osteoblastic cells, RBPJ in endothelial cells, retinoic acid receptor-γ (RARγ) and Notch in stroma. In addition, LSC coopt existing strategies normally used by HSCs to interact with the microenvironment to proliferate and survive (Expansion and Chemoresistance). For example, LSC use adhesion molecules (CD44 and VLA-4) to bind the extracellular matrix and stroma cells, and CXCR4 to bind the abundantly secreted CXCL12. Both mechanisms enable leukemia cell migration. Leukemia also shapes the microenvironment (Remodeling) by creating a proinflammatory milieu, impairing MSC differentiation and destroying key HSC-supportive niches. As a result, HSCs intravasate, whereas leukemia cells remain within the parenchyma. LC, leukemic cell; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; SNS, sympathetic nervous system; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

The crosstalk between leukemic cells and the microenvironment. Several studies suggest a causative role of the BM microenvironment in leukemogenesis (Initiation), mediated by alterations of signaling pathways in specific cell types, involving, for example, β-catenin, Jagged1, Ptpn11, Dicer1 in osteoblastic cells, RBPJ in endothelial cells, retinoic acid receptor-γ (RARγ) and Notch in stroma. In addition, LSC coopt existing strategies normally used by HSCs to interact with the microenvironment to proliferate and survive (Expansion and Chemoresistance). For example, LSC use adhesion molecules (CD44 and VLA-4) to bind the extracellular matrix and stroma cells, and CXCR4 to bind the abundantly secreted CXCL12. Both mechanisms enable leukemia cell migration. Leukemia also shapes the microenvironment (Remodeling) by creating a proinflammatory milieu, impairing MSC differentiation and destroying key HSC-supportive niches. As a result, HSCs intravasate, whereas leukemia cells remain within the parenchyma. LC, leukemic cell; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; SNS, sympathetic nervous system; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Leukemia initiation

It has been suggested that changes to the steady-state HSC niche can promote leukemogenesis. In mouse models, onset of pre–leukemic myeloproliferative-like disease has been observed after manipulation of the microenvironment. Specifically, loss of retinoic acid receptor-γ in nonhematopoietic cells,16 defective Notch signaling (either endothelial-specific17 or global18 ), and targeted expression of Ptpn11 activating mutations in MSCs and osteoprogenitors (a positive regulator of RAS signaling found in Noonan syndrome)19 have been implicated in disease development. Furthermore, a condition similar to myelodysplastic syndrome with sporadic progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML)/myeloid sarcoma was observed after specific deletion of the endoribonuclease Dicer1 in osteprogenitors.20 In these mice, mutated osteoprogenitors expressed lower levels of Sbds, the gene mutated in Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome (a condition characterized by BM failure, occasional myelodysplastic syndrome development, and secondary AML). Interestingly, deletion of Sbds in osteoprogenitors mimicked the phenotype observed in Dicer loss. Additional support for the role of osteolineage cells in leukemogenesis is demonstrated by mouse models in which overexpression of β-catenin was targeted to osteoblasts. This was shown to induce transformation of HSCs and promote AML development mediated by the downstream overexpression of the Notch ligand Jagged-1 in osteoblasts.21 These data points provide evidence that in mouse models the microenvironment can initiate leukemogenesis or promote the growth of mutant hematopoietic cells that do not usually expand under normal homeostatic conditions. However, it is still uncertain whether similar changes in the microenvironment alone are causative of human leukemias.22 Clinically, this hypothesis is best supported by donor cell leukemia,23 where leukemia originates from engrafted donor cells after allogeneic HSC transplantation. These cases strongly suggest that the microenvironment can initiate leukemogenesis in healthy cells. However, the contribution of drug-induced effects on the stroma and transplanted hematopoietic cells are still being questioned. Furthermore, the prevalence of donor cell leukemia is rare (reviewed in Reichard et al24 ). Therefore, it is still unclear whether these cases result from rare germ line mutations or alternatively are driven by alterations in the recipient BM microenvironment.

Leukemia propagation and development of chemoresistance

There is an increasingly popular view that development of cancer follows a Darwinian-like evolution, in which microenvironmental changes contribute to the selection and expansion of adapted malignant clones.25 It is not clear whether the microenvironment facilitates the propagation of preleukemic clones. Clonal hematopoiesis is a recently described entity in which clonally expanded hematopoietic cells harboring somatic mutations are found in persons with no history of hematological malignancy.26-29 It is present in >10% of individuals >70 years old, and it is associated with increased all-cause mortality and with a 10-fold higher incidence of hematologic cancer.26,27 The methyltransferase DNMT3A is the most commonly mutated gene in clonal hematopoeisis26-28 and is commonly mutated in leukemia (reviewed in Brunetti et al30 ). Consistently, Dnmt3a-null HSCs have increased self-renewal capacity and expand preferentially in competitive transplantation assays.31 Moreover, DNMT3Amut preleukemic HSCs were shown to outcompete wild-type HSCs and to survive in AML patients in remission.32 There is evidence that an aged BM microenvironment favors the expansion of single dominant HSPCs clones.33 Whether the competitive fitness of DNMT3Amut preleukemic is purely driven by cell intrinsic mechanisms or whether the microenvironment is also taking part is currently unexplored.

Through a series of xenotransplantation studies,34,35 it was shown that once overt disease is established, AML cells are hierarchically organized and are descendants of rare transformed leukemic stem cells (LSCs) that have the ability to self-renew and differentiate into highly proliferative progeny. The resultant leukemic cell mass is the result of clonal evolution and is organized in a complex architecture where dominant clones coexist with minor subclones. This complexity is illustrated by genomic analyses of leukemic samples showing that AML relapse can be driven by either the dominant clone or the minor subclones, upon acquisition of new mutations during chemotherapy.36 However, and despite the genomic complexity, it was recently shown that leukemic cells with a “stemlike” transcriptional signature initiate disease relapse in AML.37 Although consensus regarding the role of LSCs has not been reached,38 the similarities in phenotype and biology between LSCs and HSCs39 have propagated the idea that LSCs (much like HSCs) reside in niches that support the expansion, survival, and relapse of leukemia.13,14 It is likely that BM niches act differently on LSCs and blasts. For example, the chemokine CXCL12 (also known as SDF-1α) secreted specifically by osteoblastic cells was shown to be irrelevant for the maintenance of HSCs but key for early lymphoid progenitors.40 An analogous differential regulation might exist in the maintenance of LSCs vs blasts during leukemia propagation. Importantly, the relationship between malignant cells and the microenvironment is also specific to both disease stage and subtype. LSCs in AML34 and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)41 are well characterized and have previously been suggested to have an altered dependency on the endosteal niche, and specifically, osteoblastic cells after parathyroid hormone treatment.42 In this context, the expansion of osteoblastic cells promotes the propagation of MLL-AF9–driven AML, whereas it halts BCR-ABL CML-like disease.42

In contrast with factor-specific microenvironments within the tissue, the BM as a whole can also be viewed as having its own unique factor/environmental identity when compared with other organs. Perhaps the most frequently studied of these “globally distributed” BM leukemia-stroma interactions is the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis. These interactions support leukemia cells that express high levels of CXCR4 and bind CXCL12, secreted by multiple BM stromal cells. Using genetic models and CXCR4 antagonists (eg, AMD3100/plerixafor), it was shown that CXCL12 promotes the homing, residence, and survival of leukemic cells in the BM.43-46 These studies provided the rationale for clinical trials (proved safe in AML47 ) and for the development of new, more potent, CXCR4 antagonists.48 However, it is not well understood how short-acting CXCL12 gradients may control the behavior of leukemic cells (eg, cell migration) within the BM. In addition to CXCR4, there are other molecules expressed by leukemic cells crucial for their adhesion to, and survival in, the BM microenvironment. Chemoresistance is enhanced in leukemic cells expressing the integrin VLA-4, which binds fibronectin in the extracellular matrix49 and VCAM-1 on BM stroma.50 Another key adhesion molecule on leukemia cells is the glycoprotein CD44, which binds hyaluronic acid in the extracellular matrix. LSCs in both CML51 and AML52 require CD44 for homing and engraftment efficiency, whereas this molecule seems dispensable for healthy HSCs.

More recently, we challenged the view that all leukemic cells depend on specific niches. Using intravital microscopy, we tracked T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) cells from early stages of BM infiltration to development of chemoresistance.53 Imaging the whole BM tissue revealed that seeding and chemoresistant T-ALL cells are stochastically distributed in relation to Col2.3+ osteoblasts, Nestin+ MSCs, and blood vessels. Contrary to the popular view that leukemic cells are immotile and evade chemotherapy by nesting in specific hot spots, we observed that T-ALL cells are highly motile and exploratory. The mechanisms driving this motility and whether this migratory phenotype is a feature of other types of leukemia are still unresolved.

BM remodeling

The interplay of leukemic cells with the BM microenvironment has been demonstrated to be a 2-way street, with malignant cells able to remodel the microenvironment. This is well illustrated by the destruction of BM microenvironments induced by xenotransplanted ALL cell lines.15,54 Importantly, the leukemia-driven remodeling can promote the loss of bone homeostasis and healthy hematopoiesis and also lead to the expansion and survival of the leukemia itself. For example, precursor B-cell ALL cells were shown to secrete CCL3, recruit Nestin+ MSCs from sinusoidal niches, and promote their transition into α-SMA+ cells (through transforming growth factor–β1) to form chemoprotective islands.54

Perhaps the best-studied example of BM remodeling in hematological malignancies is multiple myeloma (MM). MM is characterized by the accumulation of malignant antibody-secreting plasma cells in the BM. The severe buildup of BM plasma cells results in both elevated serum immunoglobulin and significant bone loss. Bone disease remains one of the most significant issues in management of MM. Patients with bone disease have a significant increase in morbidity, and the number of bone lesions (which is a reflection malignant plasma cell infiltration in the BM) directly correlates with a poorer prognosis for patients.55,56 Bone remodeling is driven by factors intrinsic to MM cells as well as extrinsic sources from additional hematopoietic cell populations recruited to foci of malignant cells. These include receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-β ligand, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α, interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-6, IL-7, stromal cell–derived factor 1α (SDF-1α), and vascular endothelial growth factor (reviewed in Jonsson et al57 ). Combined, they disrupt the balance between healthy bone production and resorption by osteoblasts and osteoclasts.

Recently, we53 and others55 have reported that osteoblastic remodeling is also a characteristic of T-ALL. We observed that T-ALL cells cause dramatic remodeling of bone tissue through induction of apoptosis in osteoblastic cells. This remodeling is aggressive and can lead to complete loss of healthy endosteal niches in <48 hours once the BM is fully infiltrated by T-ALL cells.53 Although the mechanisms, exact consequences, and prevalence of osteoblastic remodeling in other subtypes of ALL are not well understood, therapeutic interventions that protect these endosteal cells are a potentially exciting option for management of bone pain observed in pediatric ALL (and less frequently in adult cases).57,58

The role of remodeling in leukemia cell propagation is also exemplified by models of CML, where modification of MSC differentiation into an aberrant profibrotic osteoblast lineage promotes leukemia growth at the expense of normal hematopoiesis.59 Similarly, in the MLL-AF9 model of AML, sympathetic neuropathy develops and limits the differentiation of Nestin+ MSCs into NG2+ periarteriolar cells that normally support HSCs.60 In JAK2V617F-induced myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), HSC-supporting Nestin+ MSCs are critically reduced. Interestingly, the specific depletion of Nestin+ MSCs causes expansion of hematopoietic progenitors and an MPN-like phenotype, highlighting the interplay between niche and leukemic cells.61 In MPN patients and MPN mice, there is also a loss of sympathetic nerve fibers and nonmyelinating Schwann cells next to Nestin+ cells.61 This remodeling is mediated by IL-1β and can be partially reverted by pharmacological treatment.61 More recently, we showed that AML selectively remodels endosteal blood vessels and osteoblasts at later disease progression.62 Endosteal areas have been described as the major site for initiation of AML relapse,13 and disruption of this major osteovascular HSC niche63 is emerging as a key mechanism, allowing AML to inhibit healthy hematopoiesis. Interestingly, T-ALL patients rarely develop cytopenias, and in this disease model, loss of osteoblastic cells was not accompanied by loss of endosteal vessels.62 Altogether, these studies show the decay of HSC-supportive niches in several types of leukemia and support the view that leukemic cells outcompete HSCs64 by reshaping the BM microenvironment.

The factors driving remodeling of the BM microenvironment in leukemia are not well understood. Nevertheless, inflammation (a hallmark of cancer65 ) seems likely to be a key player in the leukemic niche, and candidate remodeling factors observed in different leukemia types perhaps reflect lineage-specific immune function left over from their premalignant state. The proinflammatory environment is driven by cytokines that depend on the model used and leukemia subtype studied and include tumor necrosis factor17,62,66 (in MPN and AML), IL-1β59,61 (in MPN), CCL354,60 (in MPN and ALL), and CXCL262 (in AML). In addition, nonimmunomodulatory factors such as exosomes that transport microRNAs67 have also been implicated in leukemia-induced remodeling of the microenvironment.68

Conclusions

Here, we have summarized examples of leukemia-microenvironment crosstalk. The emerging picture is that although redundancy is observed and common pathways are potentially shared across multiple leukemias, it is likely that most microenvironment interactions are leukemia subtype specific.42 Understanding how preleukemic and leukemic cells coopt and disrupt HSC niches will help with designing new therapies that target the microenvironment to restore healthy hematopoiesis, improve HSC transplantation, and limit disease relapse. The combination of chemotherapy with novel approaches that target cell-intrinsic mechanisms with new CXCR4 antagonists,46,48 small molecules targeting cell adhesion,51,52 and anti-inflammatory therapies66 has the potential to improve disease outcomes in leukemia. Furthermore, changes of the BM stroma in leukemic patients have potential for use as less-invasive prognostic factors69 that could revolutionize disease management in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize to the authors whose work we were not able to mention due to space limitations.

This work was supported by the Graduate Program in Areas of Basic and Applied Biology PhD program (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia fellowship SFRH/BD/52195/2013) (D.D.) and by the EHA-ASH TRTH program (D.D.); by Bloodwise (12033 and 15031) (C.L.C.), Human Frontiers Science Program (RGP0051/2011) (C.L.C.), Cancer Research UK (C36195/A1183) (C.L.C.), Biology and Biotechnology Research Council (BB/I004033/1) (C.L.C.), Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund (KKL460) (C.L.C.), and European Research Council (337066) (C.L.C.); by the European Hematology Association (EHA) (E.H.), Bloodwise (12033) (E.H.), and National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (E.H.).

Authorship

Contributions: D.D. and E.D.H. cowrote the manuscript and performed research related to the review; C.L.C. cowrote the manuscript and supervised research.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.L.C. is a consultant for Onkaido Therapeutics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for D.D. is Portuguese Institute of Oncology, Porto (IPO-Porto) & Instituto de Investigação e Inovação em Saúde (i3S), University of Porto, Porto, Portugal.

Correspondence: Cristina Lo Celso, Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Sir Alexander Fleming Building, London SW7 2AZ, United Kingdom; e-mail: c.lo-celso@imperial.ac.uk.

REFERENCES

Author notes

D.D. and E.D.H. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal