Abstract

Large granular lymphocyte (LGL) leukemia has been recognized by the World Health Organization classifications amongst mature T-cell and natural killer (NK) cell neoplasms. There are 3 categories: chronic T-cell leukemia and NK-cell lymphocytosis, which are similarly indolent diseases characterized by cytopenias and autoimmune conditions as opposed to aggressive NK-cell LGL leukemia. Clonal LGL expansion arise from chronic antigenic stimulation, which promotes dysregulation of apoptosis, mainly due to constitutive activation of survival pathways including Jak/Stat, MapK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–Akt, Ras–Raf-1, MEK1/extracellular signal-regulated kinase, sphingolipid, and nuclear factor-κB. Socs3 downregulation may also contribute to Stat3 activation. Interleukin 15 plays a key role in activation of leukemic LGL. Several somatic mutations including Stat3, Stat5b, and tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3 have been demonstrated recently in LGL leukemia. Because these mutations are present in less than half of the patients, they cannot completely explain LGL leukemogenesis. A better mechanistic understanding of leukemic LGL survival will allow future consideration of a more targeted therapeutic approach than the current practice of immunosuppressive therapy.

Introduction

Initially described in 1985, large granular lymphocyte (LGL) leukemia belongs to the rare chronic mature lymphoproliferative disorders of the T/natural killer (NK) lineage.1 Two subtypes of LGL disorders were proposed in 1993: T-LGL leukemia and aggressive NK-cell leukemia.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) recognized this classification scheme in 2001. Chronic NK-cell lymphocytosis was identified in 2008 as a provisional entity to differentiate it from the much more aggressive form of NK-cell leukemia.3,4 The most recent WHO version did not modify this classification scheme but did highlight the discovery of Stat mutations described in 2012 (Table 1).5,6 T-LGL leukemia and chronic NK-cell lymphocytosis share the same clinical and biological presentation, as well as treatment options.2,7-9 Pathogenesis of the disease is dominated by a clonal expansion of LGL resistant to activation-induced cell death due to constitutive survival signaling. This review will describe topics concerning diagnosis, pathogenesis, current, and future therapy of this rare disease.

Classification of LGL leukemia according to the WHO classification

| WHO (2001) . | WHO (2008) . | WHO (2016) . |

|---|---|---|

| Mature T- and NK-cell neoplasms . | Mature T- and NK-cell neoplasms . | Mature T- and NK-cell neoplasms . |

| T-cell LGL leukemia | T-cell LGL leukemia | T-cell granular lymphocytic leukemia |

| Aggressive NK-cell leukemia | Chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of NK cells* | Aggressive NK-cell leukemia |

| Aggressive NK-cell leukemia | Chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of NK cells* | |

| Modifications: | ||

| New subtypes recognized with clinicopathological manifestations | ||

| Stat3 and Stat5b mutations in a subset; latter associated with more clinically aggressive disease |

| WHO (2001) . | WHO (2008) . | WHO (2016) . |

|---|---|---|

| Mature T- and NK-cell neoplasms . | Mature T- and NK-cell neoplasms . | Mature T- and NK-cell neoplasms . |

| T-cell LGL leukemia | T-cell LGL leukemia | T-cell granular lymphocytic leukemia |

| Aggressive NK-cell leukemia | Chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of NK cells* | Aggressive NK-cell leukemia |

| Aggressive NK-cell leukemia | Chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of NK cells* | |

| Modifications: | ||

| New subtypes recognized with clinicopathological manifestations | ||

| Stat3 and Stat5b mutations in a subset; latter associated with more clinically aggressive disease |

Provisional entity.

Epidemiology

LGL leukemia accounts for 2% to 5% of chronic lymphoproliferative disorders in North America and Europe, and up to 5% to 6% in Asia.2 Recently, the overall age-standardized incidence based on the national Dutch registry has been reported as 0.72 per 1 000 000 person-per year.10 The incidence of LGL leukemia does not differ between male and female. Indolent T-LGL leukemia is the most frequent form of the disease representing ∼85% of the cases, whereas chronic NK-cell lymphocytosis is estimated at <10% of cases.

Diagnosis

A definite diagnosis of LGL leukemia requires finding evidence of an expanded clonal T- or NK-cell LGL population.

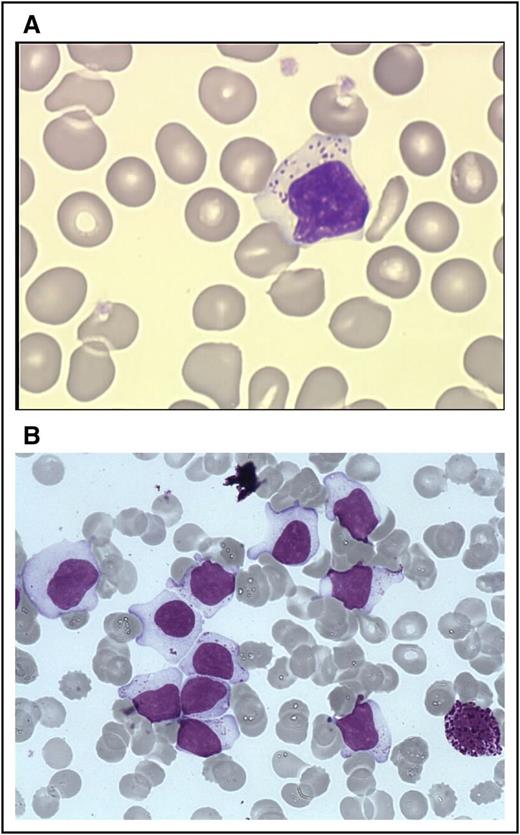

Cytology

The first step of diagnosis is based on identification of increased numbers of circulating LGL. Initially, an LGL count >2 × 109/L (normal value: <0.3 × 109/L) was mandatory,2,13 but a lower number may be compatible with the diagnosis if these cells are clonal and the patient displays other clinical or hematologic features such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or cytopenias. Indeed, it has been found that some patients with relatively low LGL counts (even <1 × 109/L) have a clonal disorder.9,13-15 Leukemic LGL are easily identified on blood smears by their specific morphology; however, they are not cytologically distinguishable from normal reactive cytotoxic lymphocytes. They display a large size (15-18 μ), an abundant cytoplasm containing typical azurophilic granules, and a reniform or round nucleus with mature chromatin (Figure 1A). Blood smears must be examined carefully in cases of normal lymphocyte counts, and in rare cases in which the clonal lymphocytes do not present with typical LGL morphology. LGL excess in bone marrow (BM) (>10% LGL) is detected in the majority of cases2 (Figure 1B).

LGLs on blood and marrow smears. (A) A typical LGL on blood smear. (Wright-Giemsa stain: original magnification ×1000; Caméra RETIGA 2000). (B) BM smear showing numerous LGL with a basophilic neutrophil. (Wright-Giemsa stain: original magnification ×1000; Caméra RETIGA 2000). Image courtesy of Beatrice Ly-Sunnaram (Rennes University Hospital, Rennes, France).

LGLs on blood and marrow smears. (A) A typical LGL on blood smear. (Wright-Giemsa stain: original magnification ×1000; Caméra RETIGA 2000). (B) BM smear showing numerous LGL with a basophilic neutrophil. (Wright-Giemsa stain: original magnification ×1000; Caméra RETIGA 2000). Image courtesy of Beatrice Ly-Sunnaram (Rennes University Hospital, Rennes, France).

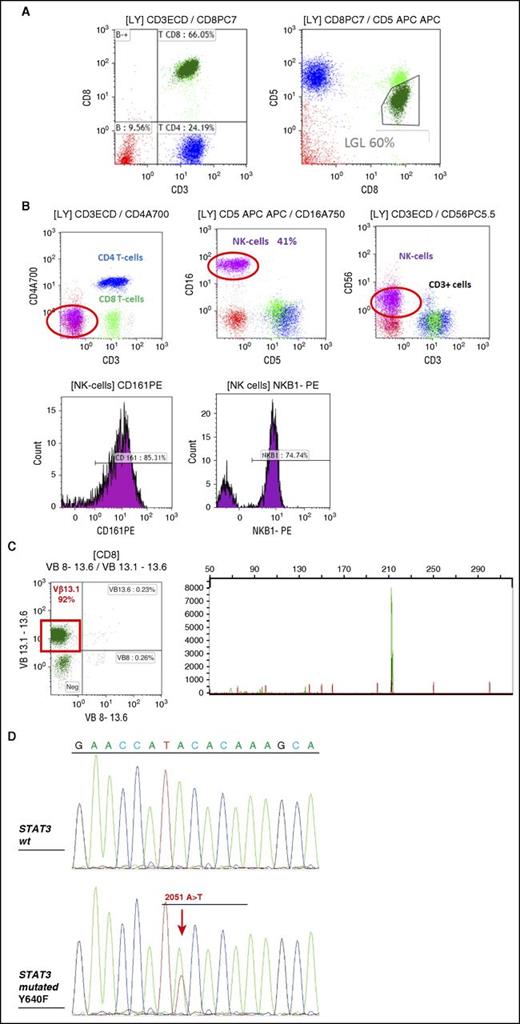

Immunophenotyping

T-LGL leukemias show a constitutive mature post-thymic phenotype. In the vast majority of cases, T-LGL leukemia shows a CD3+, TCR αβ+, CD4−, CD5dim, CD8+, CD16+, CD27−, CD28−, CD45R0−, CD45RA+, and CD57+ phenotype, which represents a constitutively activated T-cell phenotype (Figure 2A).16-18 CD3+/CD56+ T-LGL leukemias may have a more aggressive behavior associated with Stat5b mutations.19,20 A rare subset of LGL leukemia is CD4+ with or without coexpression of CD8. Patents with this LGL leukemia subtype almost never have cytopenias, splenomegaly, or autoimmune phenomena,21,22 and clonal LGL seem to be driven by cytomegalovirus.23 Recently, it was found that Stat5b mutations are frequent in this LGL subtype.24

FCM and TCR γ gene rearrangement analysis in LGL leukemia. (A) FCM analysis of a typical case of T CD3+ LGL leukemia showing CD3+/CD5dim/CD8+ (dark green). (B) FCM analysis of a case of NK CD3− LGL leukemia showing a CD3−/CD8−/CD16+/CD56+ phenotype (pink). KIR monotypic expression using CD161 and NkB1. (C) Clonality assessment: specific Vβ mAbs showing restricted expression of Vβ13.1 >90% (left); detection of clonal TCR γ gene recombination by gene scanning analysis, showing single peak in green (right). (D) Stat 3 mutation detection in a case of T-LGL leukemia using Sanger sequencing. FCM, flow cytometry; WT, wild-type.

FCM and TCR γ gene rearrangement analysis in LGL leukemia. (A) FCM analysis of a typical case of T CD3+ LGL leukemia showing CD3+/CD5dim/CD8+ (dark green). (B) FCM analysis of a case of NK CD3− LGL leukemia showing a CD3−/CD8−/CD16+/CD56+ phenotype (pink). KIR monotypic expression using CD161 and NkB1. (C) Clonality assessment: specific Vβ mAbs showing restricted expression of Vβ13.1 >90% (left); detection of clonal TCR γ gene recombination by gene scanning analysis, showing single peak in green (right). (D) Stat 3 mutation detection in a case of T-LGL leukemia using Sanger sequencing. FCM, flow cytometry; WT, wild-type.

T-LGL leukemic cells are characterized by a terminal-effector memory phenotype defined by the expression of CD45RA and lack of CD62L expression.25 Leukemic LGL constitutively express interleukin 2 (IL-2) Rβ (p75, CD122) and perforin, but not IL-2 Rα (p55, CD25).26,27 Few cases are TCR γδ+/CD4/CD8.28,29

NK-LGL leukemia and NK-LGL lymphocytosis are characterized by the following phenotype: CD2+/sCD3−/CD3ε+/TCRαβ−/CD4−/CD8+/CD16+/CD56+ (Figure 2B).13 Fas (CD95) and Fas-ligand (Fas-L) (CD178) are strongly expressed in LGL leukemia.30,31 Restricted killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) expression is often seen in both in T- and NK-LGL leukemia.18,32

Clonality

Evidence of T-LGL clonality is routinely assessed using TCR γ-polymerase chain reaction analyses. Deep sequencing of TCR has demonstrated a restricted diversity of TCR repertoire.33 Vβ TCR gene repertoire analysis can also be ascertained using FCM and serves as presumptive evidence for clonality34,35 (Figure 2C). The current Vβ mAbs panel covers 75% of the Vβ spectrum with a high correlation between Vβ FCM and TCRγ-polymerase chain reaction results. Fluctuations in clonal dominance, as determined by complementarity determining region 3 (CDR3) sequencing, are seen in up to one-third of patients.36

It is difficult to assess the clonality of NK-LGL because these cells do not express TCR. Restricted expression of activating isoforms of KIR has been used as a surrogate marker for a monoclonal expansion (Figure 2B).32,37-39

Clonal chromosomal abnormalities have been reported in a few cases of LGL leukemia.1

Molecular findings

Constitutive activation of Stat3 in all LGL leukemia patients was first discovered in 2001.40 In 2012, common somatic gain-of-function Stat3 mutations were demonstrated in 28% to 75% of T-LGL leukemia and 30% to 48% of NK-LGL lymphocytosis6,41-43 (Figure 2D). These differences may be due to the sequencing technique and the selection of patients. Detection of identical Stat3 mutations in both T- and NK-subtypes suggests a unifying pathogenesis for these similar disorders.44 Mutations are primarily located in exons 20 and 21 encoding the Src homology 2 domain, which drives the dimerization and activation of the Stat protein. D661 and Y640 account for two-thirds of mutations.42 Activating mutations outside the Src homology 2 domain are rarely detected.45 Such mutations are located in the DNA-binding and coiled-coil domain of Stat3. Utilization of deep sequencing has demonstrated the presence of multiple subclones containing different Stat3 mutations in distinct LGL populations in individual patients.46 These findings suggest a potential need for sequencing the entire Stat3 gene. Whether or not Stat3 mutations are correlated with specific clinico-biological features remains uncertain and is the subject of ongoing research. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group prospective clinical trial suggested that a particular Stat3 mutation, Y640F, predicted response to initial therapy with methotrexate (MTX).47 The first evidence of Stat5b mutations in human disease was discovered in LGL leukemia, but this mutation is not frequent (2%).19 The N642H mutation in particular was associated with more aggressive disease and an unusual CD3+CD56+ phenotype.48

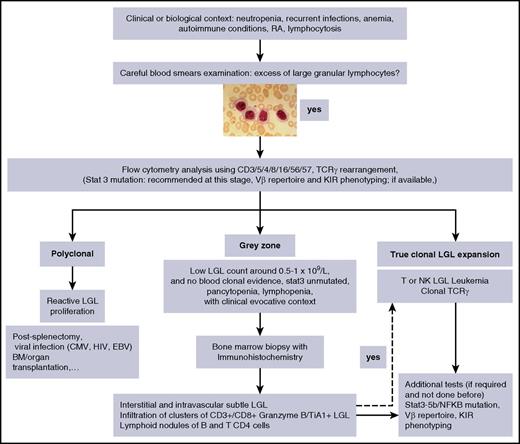

Marrow features

The diagnosis of LGL leukemia as discussed earlier is readily established using blood studies, so that marrow aspirate/biopsy is not routinely recommended as part of the initial evaluation. However, marrow evaluation can be helpful when the diagnosis is not straight forward (eg, LGL count not increased). Such studies are also of value when considering other diseases that are part of the differential, including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or aplastic anemia, or when considering the diagnosis of pure red cell aplasia (PRCA) as potential etiology of profound anemia in patients with LGL leukemia.

Individual or small clusters of LGLs may be sometimes identified. They are difficult to identify because they mimick granulocytic or monocytic precursors. Because LGL infiltration of marrow is often a subtle finding, trephine biopsy with immunohistochemistry is recommended.7,49-51 A “grey zone” where the diagnosis of LGL leukemia is not certain, should be considered in cases of low-LGL count, or even lymphopenia associated with unexplained cytopenia in which the diagnosis can be easily missed (Figure 3).

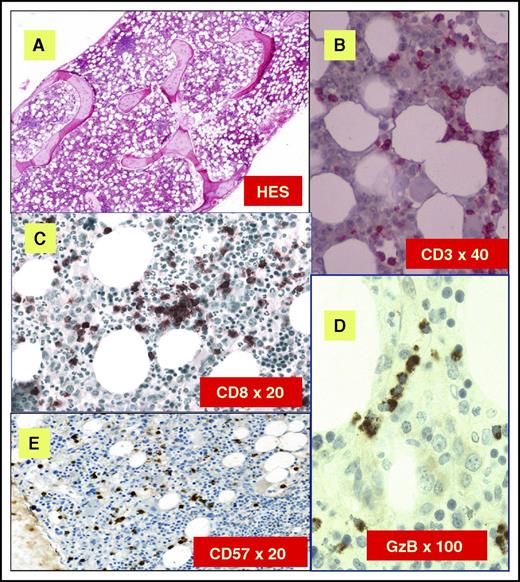

Classical histologic features are depicted in Figure 4. Clusters of eight CD8+/TiA1+ cells or six granzyme B+ lymphocytes are considered as characteristic histopathologic findings of LGL leukemia, and support this diagnosis in uncertain cases.50,52 Very close topographic distribution between dendritic cells and LGL in patient marrow samples have been shown, suggesting constant antigen presentation.53 Trilineage hematopoiesis in BM biopsies of LGL patients is normal or increased in the majority of cases. Apoptotic figures, increased macrophages, and eosinophilia have been described, suggesting an underlying dysmyelopoiesis. In neutropenic patients, a typical finding is a decrease in granulocyte precursors and left-shift maturation. However, the degree of marrow infiltration by LGL does not correlate with the degree of cytopenia.49 An increase of erythroid precursors is described in 30% to 40% of the cases. Reticulin fibrosis is usually present, ranging from grade 2 or 3 in ∼50% to 60% of the cases.54

BM features of LGL leukemia. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining (HES) of marrow biopsy reveals a slightly hypercellular marrow with a subtle increase in interstitial lymphocytes. (B) CD3 staining reveals the LGL interstitial infiltration. (C) Immunoperoxydase staining for CD8 demonstrates clusters of at least 8 cytotoxic lymphocytes CD8+. (D) Linear array of intravascular LGL demonstrated by Granzyme B (GzB) staining. (E) CD57 staining reveals the LGL interstitial infiltration. Original magnifications ×4 (A), ×40 (B), ×20 (C), ×100 (D), and ×20 (E). Images courtesy of Philippe Gaulard (Department of Pathology, Henri Mondor Hospital, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, Creteil, France) and Patrick Tas (Department of Pathology, Rennes University Hospital, Rennes, France).

BM features of LGL leukemia. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining (HES) of marrow biopsy reveals a slightly hypercellular marrow with a subtle increase in interstitial lymphocytes. (B) CD3 staining reveals the LGL interstitial infiltration. (C) Immunoperoxydase staining for CD8 demonstrates clusters of at least 8 cytotoxic lymphocytes CD8+. (D) Linear array of intravascular LGL demonstrated by Granzyme B (GzB) staining. (E) CD57 staining reveals the LGL interstitial infiltration. Original magnifications ×4 (A), ×40 (B), ×20 (C), ×100 (D), and ×20 (E). Images courtesy of Philippe Gaulard (Department of Pathology, Henri Mondor Hospital, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, Creteil, France) and Patrick Tas (Department of Pathology, Rennes University Hospital, Rennes, France).

Clinico-biological features

LGL leukemia principally affects elderly people with a median age of 60 years.2,7,8,55-58 Very rare pediatric cases have been reported and <25% of adult patients are younger than 50 years old. About one-third of patients are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Initial presentation is mainly related to neutropenia and includes recurrent oral aphthous ulcerations, fever secondary to bacterial infections. These infections typically involve skin, oropharynx, and perirectal areas, but severe sepsis may occur. However, some patients may have profound and persistent neutropenia without any infections over a very long period of time. The frequency of recurrent infections varies in different series from 15% to 39%. Fatigue and B symptoms are observed in 20% to 30% of cases. Splenomegaly is reported with a frequency varying from 20% to 50% and lymphadenopathy is rare.15 Half of the patients present with lymphocyte counts between 4 × 109/L and 10 × 109/L, and the LGL count usually ranges from 1 to 6 × 109/L. A lower LGL count (0.5 to 1 × 109/L) may be observed in 7% to 36% of cases. Severe neutropenia (<0.5 × 109/L) and moderate neutropenia (<1.5 × 109/L) are observed in 16% to 48% and 48% to 80% of cases, respectively. Anemia is frequent; transfusion-dependent patients are observed in 10% to 30% of cases. PRCA occurs in 8% to 19% of the cases and moderate thrombocytopenia is observed in <25% of patients.59

Although not routinely performed, increased soluble Fas-L (sFas-L) is a good surrogate marker of LGL leukemia.60 We and others showed that LGL leukemia patients had increased serum levels of interferon-α2, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (an attractive factor of monocytes, T, and NK cells to sites of inflammation), epidermal growth factor, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-18.47,61,62 High β2 microglobulin level is observed in 70% of cases. Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody are detected in 60% and 40% of patients, respectively.15 Serum protein electrophoresis usually shows polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia due to increased immunoglobulin G (IgG) and/or IgA subclasses. Defects in downregulation of Ig secretion in LGL leukemia could partly explain the development of autoantibodies and clonal B-cell malignancies observed in this disease.63

The associated comorbid conditions are reported in Table 2. RA is the most common associated disease, occurring in 10% to 18% of patients.7,8,17,64 Systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren syndrome, autoimmune thyroid disorders, coagulopathy, vasculitis with cryoglobulinemia, and inclusion body myositis have occasionally been reported.64-67 Pulmonary artery hypertension has been observed.68 Association with myeloid malignancies and BM failure syndromes, ie, aplastic anemia (AA), paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, and MDS, is also reported.69-71 Recurrent Stat3 mutations in de novo AA and MDS suggest similar pathogenesis.41 Efficacy of immunosuppressive treatments directed against T-lymphocyte–mediated immune response is a strong argument for a common role of autoreactive T cells in all of these diseases.

Principal associated diseases with LGL leukemia

| Associated diseases with LGL leukemia* . | Frequency (%) . |

|---|---|

| Neoplasms | 4-10 |

| Autoimmune cytopenia | 5 |

| PRCA | |

| AIHA | |

| ITP | |

| Evans syndrome | |

| B-cell lymphoid neoplasms | 5 |

| Low-grade NHL | |

| DLBCL | |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | |

| MM | |

| CLL | |

| Hairy cell leukemia | |

| Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | |

| Lymphomatoid granulomatosis | |

| Heavy chain disease | |

| Autoimmune diseases/connective tissue disorders | 10-20 |

| RA | 10-18 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Vasculitis | |

| Systemic sclerosis | |

| Endocrinopathy | |

| APECED | |

| MEN-1 | |

| Hashimoto disease | |

| Grave disease | |

| CIBD | |

| Celiac disease | |

| Gougerot-Sjogren syndrome | |

| Glomurolenephritis | |

| Polymyositis | |

| Inclusion body myositis | |

| Poly/multinevritis | |

| RPA | |

| Inflammatory arthritis (unclassified) | |

| Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome | |

| Good syndrome | |

| Behcet disease | |

| MS | |

| Acquired factor VIII inhibitor | |

| MDS | 3-10 |

| AML | <1 |

| Hemophagocytic syndrome | <1 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | <1 |

| Post-organ or hematopoietic SCT | <1 |

| Post viral infection | <1 |

| Associated diseases with LGL leukemia* . | Frequency (%) . |

|---|---|

| Neoplasms | 4-10 |

| Autoimmune cytopenia | 5 |

| PRCA | |

| AIHA | |

| ITP | |

| Evans syndrome | |

| B-cell lymphoid neoplasms | 5 |

| Low-grade NHL | |

| DLBCL | |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | |

| MM | |

| CLL | |

| Hairy cell leukemia | |

| Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | |

| Lymphomatoid granulomatosis | |

| Heavy chain disease | |

| Autoimmune diseases/connective tissue disorders | 10-20 |

| RA | 10-18 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Vasculitis | |

| Systemic sclerosis | |

| Endocrinopathy | |

| APECED | |

| MEN-1 | |

| Hashimoto disease | |

| Grave disease | |

| CIBD | |

| Celiac disease | |

| Gougerot-Sjogren syndrome | |

| Glomurolenephritis | |

| Polymyositis | |

| Inclusion body myositis | |

| Poly/multinevritis | |

| RPA | |

| Inflammatory arthritis (unclassified) | |

| Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome | |

| Good syndrome | |

| Behcet disease | |

| MS | |

| Acquired factor VIII inhibitor | |

| MDS | 3-10 |

| AML | <1 |

| Hemophagocytic syndrome | <1 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | <1 |

| Post-organ or hematopoietic SCT | <1 |

| Post viral infection | <1 |

AIHA, autoimmune hemolytic anemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; APECED, polyendocrinopathy candidosis-ectodermal dystrophy; CIBD, chronic inflammatory bowel disease; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; ITP, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; MEN-type 1, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1; MM, multiple myeloma; MS, multiple sclerosis; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; RPA, rhizomelic pseudopolyarthritis; SCT, stem cell transplantation.

Some patients presented with more than one auto-immune–associated disease.

Pathogenesis of LGL leukemia

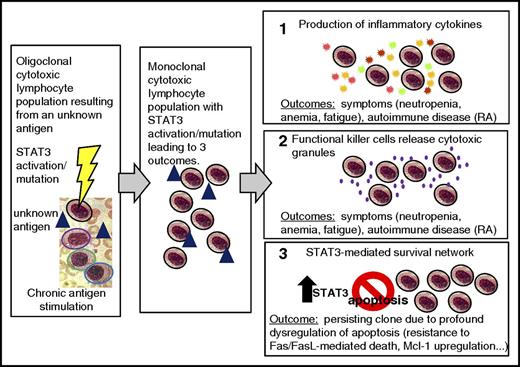

A model of LGL leukemia pathogenesis is shown in Figure 5. LGL leukemia is at the intersection of a clonal lymphoproliferative disease, chronic inflammation, and autoimmunity. We hypothesize that an unknown antigen is the initial activating event, resulting in oligoclonal LGL expansion. Such chronic and persistent antigen exposure leads to Stat3 activation and the emergence of a dominant clone. A shift from oligoclonal to clonal dominance is supported by serial studies of T-cell repertoire utilization.36 Somewhat surprisingly, clonal drift was observed with the emergence over time of a different Vbeta clone in 37% of patients.36 We speculate that clonal drift results from the emergence of LGL clones recognizing different epitopes/peptides of the same chronic antigen. This theory could also explain the observation of clonal T-cell LGL populations seen in patients with chronic NK lymphocytosis, as well as the emergence of a new NK clone in patients with established T-cell LGL leukemia.72

Model of LGL leukemia pathogenesis. Activation and expansion occur, resulting in an oligoclonal cytotoxic lymphocyte population (colored outline represents a distinct clone, blue triangle represents an unknown antigen). STAT3 is activated and may acquire a mutation. Chronic antigen stimulation leads to expansion of one dominant (monoclonal) cytotoxic lymphocyte population (all are outlined in black signifying the monoclonal population). Three outcomes occur. In panel 1, the production of inflammatory cytokines (starburst shapes representing: IFN-γ, IL-8, IL-10, IL-1β, IL-12p35, IL-18, IL-1Ra, RANTES, MIP1-α, and MIP1-β) causes symptoms such as neutropenia, anemia, and fatigue, and can also cause an autoimmune disease such as RA. In panel 2, the functional killer cells release cytotoxic granules containing perforin and granzyme B (purple dots); this leads to the same outcomes as in panel 1. In panel 3, the STAT3-mediated survival network results in a persisting clone due to profound dysregulation of apoptosis, including resistance to Fas/FasL-mediated death and upregulation of Mcl-1. IFN, interferon; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein.

Model of LGL leukemia pathogenesis. Activation and expansion occur, resulting in an oligoclonal cytotoxic lymphocyte population (colored outline represents a distinct clone, blue triangle represents an unknown antigen). STAT3 is activated and may acquire a mutation. Chronic antigen stimulation leads to expansion of one dominant (monoclonal) cytotoxic lymphocyte population (all are outlined in black signifying the monoclonal population). Three outcomes occur. In panel 1, the production of inflammatory cytokines (starburst shapes representing: IFN-γ, IL-8, IL-10, IL-1β, IL-12p35, IL-18, IL-1Ra, RANTES, MIP1-α, and MIP1-β) causes symptoms such as neutropenia, anemia, and fatigue, and can also cause an autoimmune disease such as RA. In panel 2, the functional killer cells release cytotoxic granules containing perforin and granzyme B (purple dots); this leads to the same outcomes as in panel 1. In panel 3, the STAT3-mediated survival network results in a persisting clone due to profound dysregulation of apoptosis, including resistance to Fas/FasL-mediated death and upregulation of Mcl-1. IFN, interferon; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein.

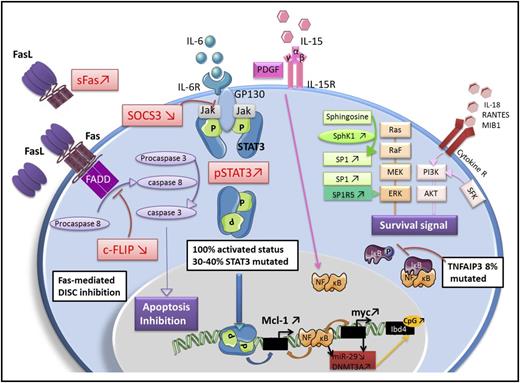

LGL leukemia is characterized by profound dysregulation of the normal process of activation-induced cell death. The fundamental pathogenic feature of LGL leukemia is the activation of a survival network, which keeps the leukemic LGL alive and functioning as killer cells.73 The central hub of this survival network is Stat3. We hypothesize that activating mutations of Stat3 support clonal dominance by causing a higher level of transcription of survival components. This theory is supported by the observation that STAT3 mutations are correlated with a larger clone size in LGL leukemia patients.47 Disease manifestations such as cytopenias and autoimmune diseases then result from the production of proinflammatory cytokines mediated by STAT 3 regulation, as well as attack on marrow and joints by the STAT 3-activated LGL. The key molecular signaling components in LGL leukemia are depicted in Figure 6. Key features of the model are further summarized below.

Key molecular abnormalities in LGL leukemia. Fas-mediated death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) inhibition: LGL leukemia cells are resistant to Fas-mediated apoptosis. sFas acts as a decoy receptor able to inhibit Fas-dependent apoptosis. Increased level of an inhibitory protein named cellular FADD-like IL-1 converting enzyme inhibitory protein (c-FLIP) contributes to the DISC formation defect. Jak/Stat3 pathway: Stat3 is constitutively activated in LGL leukemia and is responsible for the transcription of B-cell lymphoma 2 and myeloid cell leukemia 1 (Mcl-1) protein expression. Inhibition of Stat3 restores apoptosis of LGL cells whatever the Stat3 mutation status, which implies that Stat3 mutation is not itself mandatory to explain LGL clonal expansion. SOCS3, which inhibits the Jak/Stat3 pathway is significantly decreased in LGL leukemia. Survival signal: LGL leukemia shows a predominant expression of specificity protein 1 (SP1). Sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1), which converts sphingosine into SP1 is increased in LGL leukemia and SphK1 inhibition leads to leukemic LGLs apoptosis. SP1 binding to SP1R activates a prosurvival signal through extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) signaling. Moreover, the expression of SP1 receptor, mainly SP1R5, is increased in LGL leukemia. Ras–Raf-1–MEK1-ERK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway are upregulated in LGL leukemia and the inhibition leads to LGL apoptosis. Increased activity of the PI3K-AKT signaling axis is found in T-LGL cells and participate in apoptotic inhibition. NF-κB activity is upregulated in LGL leukemia. NF-κB acts downstream of the PI3K-AKT pathway to prevent apoptosis through Mcl-1 independently of Stat3. A recurrent nonsynonymous mutation in the gene encoding an NF-κB signaling inhibitor, tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3), was found in 8% of LGL leukemia patients. IL-15 and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF): IL-15 promotes myc expression through the NF-κB pathway (model of IL-15 transgenic mouse). IL-15 is associated with an increase of global DNA methylation level in LGL leukemia through DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) upregulation. The downregulation of microRNA-29 (miR-29) is responsible for the upregulation of DNMT3A, which induce methylation of the tumor suppressor gene Ibd4. GP130, glycoprotein 130; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; pSTAT3, phosphoSTAT3; SFK, Src family kinase; SP1R5, specificity protein 1 receptor 5.

Key molecular abnormalities in LGL leukemia. Fas-mediated death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) inhibition: LGL leukemia cells are resistant to Fas-mediated apoptosis. sFas acts as a decoy receptor able to inhibit Fas-dependent apoptosis. Increased level of an inhibitory protein named cellular FADD-like IL-1 converting enzyme inhibitory protein (c-FLIP) contributes to the DISC formation defect. Jak/Stat3 pathway: Stat3 is constitutively activated in LGL leukemia and is responsible for the transcription of B-cell lymphoma 2 and myeloid cell leukemia 1 (Mcl-1) protein expression. Inhibition of Stat3 restores apoptosis of LGL cells whatever the Stat3 mutation status, which implies that Stat3 mutation is not itself mandatory to explain LGL clonal expansion. SOCS3, which inhibits the Jak/Stat3 pathway is significantly decreased in LGL leukemia. Survival signal: LGL leukemia shows a predominant expression of specificity protein 1 (SP1). Sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1), which converts sphingosine into SP1 is increased in LGL leukemia and SphK1 inhibition leads to leukemic LGLs apoptosis. SP1 binding to SP1R activates a prosurvival signal through extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) signaling. Moreover, the expression of SP1 receptor, mainly SP1R5, is increased in LGL leukemia. Ras–Raf-1–MEK1-ERK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway are upregulated in LGL leukemia and the inhibition leads to LGL apoptosis. Increased activity of the PI3K-AKT signaling axis is found in T-LGL cells and participate in apoptotic inhibition. NF-κB activity is upregulated in LGL leukemia. NF-κB acts downstream of the PI3K-AKT pathway to prevent apoptosis through Mcl-1 independently of Stat3. A recurrent nonsynonymous mutation in the gene encoding an NF-κB signaling inhibitor, tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3), was found in 8% of LGL leukemia patients. IL-15 and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF): IL-15 promotes myc expression through the NF-κB pathway (model of IL-15 transgenic mouse). IL-15 is associated with an increase of global DNA methylation level in LGL leukemia through DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) upregulation. The downregulation of microRNA-29 (miR-29) is responsible for the upregulation of DNMT3A, which induce methylation of the tumor suppressor gene Ibd4. GP130, glycoprotein 130; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; pSTAT3, phosphoSTAT3; SFK, Src family kinase; SP1R5, specificity protein 1 receptor 5.

An initial viral antigenic stimulation

LGL leukemic cells represent an expanded population of effector memory cytotoxic T cells, suggesting chronic antigen stimulation.25 A role of human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV) retroviral infection has been suggested primarily by serologic studies demonstrating cross-reactivity to HTLV epitopes. Such seroreactivity is directed toward the envelope protein BA21 and is seen in 30% to 50% of the patients. However, there is no definite evidence for HTLV-1 infection in LGL leukemia patients,74-78 whereas HTLV-2 has been described only occasionally.79,80

Two cases of LGL leukemia associated with B-indolent lymphoma were reported in a patient infected with hepatitis C virus infection. Both were successfully treated by antiviral therapy. This underlies a potential link between hepatitis C virus chronic infection and LGL leukemia.81 Recently, Sandberg et al analyzed CDR3-β and -α chain in 26 T CD8+ αβTCR LGL patients and found heterogeneity in the CDR3 region, suggesting that a unique antigen-driving LGL leukemia may be unlikely.82

Initiating role of IL-15 and PDGF

IL-15 proinflammatory cytokine and PDGF play a crucial role in LGL leukemia expansion by promoting NK-cell or leukemic-LGL survival.73,83 IL-15 receptor-α−/− mice display an NK-cell and CD8+ memory T-cell defect. LGL cell growth is dependent of IL-15, and IL-15α chain messenger RNA was detectable in LGL-purified cells.84,85 In a network model of LGL leukemia survival signaling, IL-15 and PDGF were predicted to be the master activation switches necessary for leukemic LGL survival.73 IL-15 has also been implicated in LGL leukemogenesis using a unique IL-15 transgenic mouse model, demonstrating an increase of global DNA methylation level in LGL cells.86 Activation of survival pathways by PDGF occurs through an autocrine loop in leukemic LGL.87

Constitutive activation of Jak-Stat3 signaling pathway

Constitutive activation of Stat3 (pStat3), in our opinion, plays the fundamental pathogenic role in LGL leukemia, because the transcriptome of LGL leukemia patients is that of Stat3-regulated genes.6,40 In vitro inhibition of Stat3 by STA-21 restores the apoptosis of LGL cell independent of Stat3 mutational status. This finding implies that Stat3 mutation is not itself mandatory to explain LGL clonal expansion. It raises the question of mechanism of Stat3 activation in unmutated patients. The proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 is able to activate the Jak-Stat3 pathway and a high amount of IL-6 is observed in LGL patients.62 Inhibition of this cytokine restores LGL apoptosis. Dendritic cells could trigger the clonal proliferation and maintain LGL expansion by IL-6 production. Because SOCS3 transcription is induced by IL-6 through pStat3, SOCS3 was postulated to be high in LGL leukemia. Surprisingly, Teramo et al showed that SOCS3 messenger RNA and protein level was significantly decreased in LGL leukemia. Demethylation agent restored SOCS3 expression in leukemic LGL, and consequently decreased Stat3 and Mcl-1 expression. No mutation or methylation of SOCS3 promoter has been found to explain this downregulation.62 Although Stat3 activation plays the most important pathogenenic role, multiple other cell survival pathways are dysregulated and these are briefly described in the sections to follow.

Resistance to Fas/Fas-L–mediated apoptosis

Leukemic LGL are resistant to Fas-mediated apoptosis.30 However, apoptosis is restored using IL-2 stimulation, suggesting an inhibition of this pathway and not a complete defect. Moreover, sFas, detected in LGL patient sera, acts as a decoy receptor able to inhibit Fas-dependent apoptosis.60 Decreased level of an inhibitory protein named c-FLIP is found in leukemic LGL contributing to DISC formation defect. This protein blocks the initial event of Fas-mediated apoptosis through Fas-associated protein with death domain and caspase 8 recruitment.25

Ras–Raf-1–MEK1-ERK pathway

Dysregulation of PI3K/Akt pathway

Activation of NF-κB pathway

Leukemic LGL exhibit a higher level of c-Rel (a member of NF-κB family) and high NF-κB activity. NF-κB inhibition induces leukemic LGL apoptosis. It has been shown that NF-κB acts downstream of the PI3K-AKT pathway to prevent apoptosis through Mcl-1 independently of Stat3.73 Recently, a recurrent nonsynonymous mutation in the gene encoding an NF-κB signaling inhibitor, TNFAIP3, was found in 3 out of 39 patients (8%), underlying the important role of NF-κB activity in LGL leukemia.91

Dysregulation of sphingolipid rheostat in LGL leukemia

Molecular expression profile analysis in LGL leukemia shows a predominant expression of prosurvival sphingolipids, such as S1P.92 SphK1, which converts sphingosine into S1P is increased in LGL leukemia and SphK1 inhibition leads to leukemic LGLs apoptosis. SP1 binding to SP1R activates prosurvival signal through ERK1/2 signaling.93 Moreover, expression of the S1P receptor, mainly S1PR5, is increased in LGL leukemia.94,95

Prognosis

T and chronic NK-LGL leukemia are considered indolent diseases. The vast majority of patients will eventually need treatment at some point during disease evolution. Disease-related deaths are mainly due to severe infections that occur in <10% of the patient population.10,14,96 Overall survival at 10 years is ∼70%. Conversely, the prognosis of aggressive NK-LGL leukemia is very poor because patients are refractory to treatment.11,12

Therapy

Treatment options are similar for T-LGL leukemia and chronic NK-cell lymphocytosis. Indications for treatment include severe neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count [ANC] <0.5 × 109/L), moderate neutropenia (ANC >0.5 × 109/L) associated with recurrent infections, symptomatic or transfusion-dependent anemia, and associated autoimmune conditions requiring therapy.9 Standard treatment of LGL leukemia is immunosuppressive therapy, but such treatment recommendations are primarily based on small retrospective series. The most clinical experience has been reported using low-dose MTX, cyclophosphamide, and cyclosporine A (CyA) as single agents (see next section).

Supportive therapy

Supportive care could be considered for patients suffering from anemia or neutropenia using erythropoietin or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), respectively. However, such treatment does not address the underlying illness. G-CSF delivered as a single agent may be effective in rapidly increasing ANC. This could be of some value in the setting of patients with episodes of severe febrile neutropenia in which a rapid neutrophil response would be desirable. However, G-CSF is not effective in all LGL leukemia patients. Of note, G-CSF may induce the exacerbation of splenomegaly and articular symptoms.97,98 Therapy with erythropoietin in LGL leukemia patients has been reported only infrequently and with disappointing results.14

First-line therapy

Immunosuppressive therapy is the foundation of treatment of LGL leukemia based on the rationale that leukemic LGL represent constitutively activated cytotoxic lymphocytes.

First-line therapy relies on the use of single immunosuppressive oral agents such as MTX (10 mg/m2 per week), cyclophosphamide (100 mg per day), or CyA (3 mg/kg per day). A minimum of 4 months of therapy is required before assessing response. Since the initial publication on the efficacy of MTX and until now, this drug has been considered as the best first-line option, mainly for neutropenic patients.99 Oral cyclophosphamide has been preferentially used in patients with predominant anemia and particularly, PRCA.59,100

Based on retrospective studies, the overall response rate (ORR) appears quite broad ranging from 21% to 85% (median, ∼50%), with similar responses to each of the 3 drugs, making comparison difficult. The complete response (CR) rate is relatively low: ∼21% for MTX, 33% for cyclophosphamide, and <5% for CyA.9 Duration of response is ∼21 months for MTX. However, the relapse rate may be high, with the French series reporting rates of 67%, compared with 13% for patients receiving cyclophosphamide.9,14 Cyclophosphamide as first-line therapy may induce high ORR with ∼50% CR rate for either neutropenic or anemic patients.101 CyA corrects cytopenia without elimination of the LGL clone.14,15,102 It has been suggested that HLA-DR4 (observed in 32% of LGL leukemia) could be highly predictive of CyA responsiveness.103

The results of the first large prospective study of immunosuppressive agents in LGL leukemia was recently reported.47 Fifty-five patients received MTX at first-line and nonresponders were switched to cyclophosphamide. The ORR was 38% in step 1 (which is lower compared with the results of the large retrospective studies) and 64% in step 2. These data indicate that a high proportion of patients may respond to cyclophosphamide even after having failed to respond to MTX.14,98 As discussed earlier, Stat3 Y640F mutation may be a predictive biomarker for response to MTX, but this observation needs validation in a larger cohort of patients. An important randomized trial (#NCT01976182) investigating first-line MTX vs cyclophosphamide is ongoing in France and will hopefully determine the best choice of initial therapy in this disease.

In case of failure of primary therapy, a switch between MTX and cyclophosphamide should be considered. In our practice, CyA is reserved for patients failing both drugs. Both MTX and CyA are maintained indefinitely, as long as these medications are reasonably tolerated and disease response is maintained. Long-term use and monitoring of low-dose MTX follows guideline recommendations of its use in RA. Hepatic (hepatitis) and lung dysfunction (hypersensitivity pneumonitis) may occur requiring regular evaluation of liver tests and chest radiographs. Our recommendation is to stop cyclophosphamide after 8 to 12 months because of its mutagenic potential. Renal function and blood pressure have to be carefully monitored during CyA treatment.9 The effects of prednisone as single agent in the treatment of LGL leukemia are not convincing but may decrease some inflammatory symptoms related to RA, and in rare cases, it may transiently improve neutropenia.

Second-line therapy

It is difficult to make any treatment recommendations for patients refractory to the first-line agents because of the rarity of the disease and the general absence of prospective data. To the authors’ knowledge, there is only 1 ongoing clinical trial in the United States, which investigates alemtuzumab.104 T.P.L.’s practice is to refer refractory patients for consideration for participation in this study, which is being conducted at the National Institutes of Health.

Clinical experience using a number of different options in a smaller number of patients has been reported for LGL leukemia patients and these could be considered for refractory patients. These results are summarized as follows:

Purine analogs.

Less than 50 patients have been reported to be treated with either fludarabine, cladribine, deoxycoformycine, or bendamustine.14,102,105-107 The ORR looks promising at ∼79%. Remissions are usually obtained rapidly and the patients may be treated with a maximum of 1 to 3 courses in order to limit toxicity. Fludarabine has been used in combination with mitoxantrone with long-lasting complete remission. Whether or not purine analogs should be integrated into first-line therapy is an open question.

Combined chemotherapy.

Polychemotherapy based on cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone-like or cytosine-arabinoside–containing regimen has not demonstrated efficacy in chronic refractory form of disease and should be reserved for rare cases of aggressive LGL leukemia. In some cases of multirefractory patients, SCT could be considered. We recently reported the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation series of 15 patients receiving auto or allogeneic SCT.108 Six patients remained disease-free posttransplantation.

Immunotherapy.

Alemtuzumab (Campath), which is a humanized monoclonal antibody (mAb) (anti-CD52) has been proposed for refractory patients in very limited series. The ORR is ∼60%.9,14,15,104 However, the general availability of this drug is now limited and infectious risks limit the use of this agent. Efficacy of extracorporeal photopheresis has been reported recently with documented CR.109

Rituximab, the specific anti-CD20 mAb, has been paradoxically used in patients with both RA and LGL leukemia. It was suggested that eradication of B-cell expansion and autoimmune antigens could have led to the eradication of reactive LGL clones. In our opinion, this is not a reasonable option for LGL leukemia.110,111

Splenectomy.

Targeted therapy.

Considering the pathogenesis of LGL leukemia, different specific pathways conceivably could be targeted using either cytokine antagonistic agents, mAbs directed against membrane receptors, Jak/Stat inhibitors, NF-κB, or farnesyl transferase/Ras inhibitors.

Regarding IL-15 targeting, a clinical trial (#NCT 00076180) has tested the effects of Hu-Mikβ1, which blocks IL-15 trans presentation to T cells that express IL-2/IL-15Rβ (CD122). Administration of Hu-Mikβ1 to patients was safe but clinical responses were not observed.114 A phase 1 study with an anti-CD2 mAb (siplizumab) was conducted in 2005 in patients with relapsed/refractory CD2+ T-cell lymphoma/leukemia, including T-LGL leukemia (#NCT00123942). To our knowledge, the results of this trial have not been published.

Based on constitutive Ras activation in leukemic LGL, a phase 2 study investigating the use of farnesyltransferase inhibitor (tipifarnib) enrolled a total of 8 patients. No clinical responses were observed despite a significant improvement in marrow hematopoiesis and increased hematopoietic colony growth in vitro.115

A Stat inhibitor, OPB-31121, had a significant antitumor effect on leukemia cells with Stat-addictive oncokinases.116 Stat3 inhibition could be a good therapeutic option in LGL leukemia. Of interest, low-dose MTX was recently identified as a very active inhibitor of the Jak/Stat pathway, perhaps now explaining its efficacy in LGL leukemia.117 However, in complete responders, STAT3-mutated subclones are still detected.46 There are recent exciting data concerning Jak3 pathway inhibition. Jak3 is now considered a target for immunosuppression. Tofacitinib citrate (CP690550), a Jak3-specific inhibitor has demonstrated impressive activity in refractory RA.118,119 Recently, 9 patients with refractory LGL leukemia and RA were treated with tofacitinib citrate. Hematologic response was observed in 6 of 9 cases, with improvement in neutropenia observed in 5 of 7 patients.120 Because NF-κB is constitutively active in T-LGL, bortezomib could be considered a promising agent for investigation in LGL leukemia, as supported by demonstrated efficacy in the LGL leukemia model of IL-15 transgenic mice.86 In LGL leukemia, proapoptotic signals (ceramide) are downregulated and prosurvival signals (S1PR5) are upregulated.93,94 We showed that FTY720, a S1PR agonist, induced apoptosis of LGL cells and that C6-ceramide encapsulated in nanoliposomes and led to apoptosis in an NK-LGL rat leukemia model by targeting survivin. A trial of ceramide nanoliposomes is ongoing in patients with advanced solid tumors (#NCT02834611) and this could be a potential therapeutic candidate for LGL leukemia.

Conclusion

It appears that immunosuppressive agents, such as MTX, cyclophosphamide, and CyA are limited in their capacity to eradicate the LGL clone and induce long-lasting remission. Due to a lack of prospective comparative clinical trials, a decision as to which one of these 3 agents is best proposed as first-line therapy cannot be made. There is an urgent unmet need to develop better therapeutics for LGL leukemia, because this disease remains incurable. Significant progress has been made in our understanding of LGL clonal expansion, primarily based on the importance of Stat3 activation/mutation in pathogenesis of illness. This knowledge suggests the possibility of using targeted therapy such as Jak/Stat inhibitors, which are currently under development, have entered clinical trials, or are already US Food and Drug Administration-approved for other medical conditions.

Authorship

Contribution: T.L., A.M., and T.P.L. participated in the writing of this manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Thierry Lamy, Department of Hematology, Pontchaillou University Hospital, 2 Rue Henri le Guilloux, 35000 Rennes, France; e-mail: thierry.lamy@univ-rennes1.fr.