Key Points

BI 836858, an Fc-engineered anti-CD33 antibody, mediates autologous and allogeneic NK cell–mediated ADCC.

Decitabine increases ligands for activating NK receptors potentiating BI 836858 activity, providing a rationale for combination therapy.

Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common type of acute leukemia, affecting older individuals at a median age of 67 years. Resistance to intensive induction chemotherapy is the major cause of death in elderly AML; hence, novel treatment strategies are warranted. CD33-directed antibody-drug conjugates (gemtuzumab ozogamicin) have been shown to improve overall survival, validating CD33 as a target for antibody-based therapy of AML. Here, we report the in vitro efficacy of BI 836858, a fully human, Fc-engineered, anti-CD33 antibody using AML cell lines and primary AML blasts as targets. BI 836858–opsonized AML cells significantly induced both autologous and allogeneic natural killer (NK)-cell degranulation and NK-cell–mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). In vitro treatment of AML blasts with decitabine (DAC) or 5-azacytidine, 2 hypomethylating agents that show efficacy in older patients, did not compromise BI 836858–induced NK-cell–mediated ADCC. Evaluation of BI 836858–mediated ADCC in serial marrow AML aspirates in patients who received a 10-day course of DAC (pre-DAC, days 4, 11, and 28 post-DAC) revealed significantly higher ADCC in samples at day 28 post-DAC when compared with pre-DAC treatment. Analysis of ligands to activating receptors (NKG2D) showed significantly increased NKG2D ligand [NKG2DL] expression in day 28 post-DAC samples compared with pre-DAC samples; when NKG2DL receptor was blocked using antibodies, BI 836858–mediated ADCC was significantly decreased, suggesting that DAC enhances AML blast susceptibility to BI 836858 by upregulating NKG2DL. These data provide a rationale for combination therapy of Fc-engineered antibodies such as BI 836858 with azanucleosides in elderly patients with AML.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common acute leukemia in adults, causing >10 000 deaths per year in the United States.1-3 Antibody-based therapeutics in AML have targeted CD33 (sialic acid–binding immunoglobulin-like lectin 3) which is expressed in over 80% of leukemic cells.4-7 Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO), an anti-CD33 immunoconjugate, is composed of a humanized immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) antibody conjugated to the powerful antimitotic calicheamicin which mediates cell death following rapid internalization of the antibody-antigen complex formation.5 However, GO (marketed as Mylotarg) was voluntarily withdrawn from the market in June 2010 after a phase 3 trial in newly diagnosed AML showed a trend toward increased mortality in the GO arm.8 Since that time, data from phase 3 trials and a meta-analysis have shown an advantage in overall survival in patients treated with GO combined with standard induction chemotherapy in older AML patients.9,10 An unconjugated humanized anti-CD33 antibody, lintuzumab (HuM195), has also resulted in complete remissions in elderly patients,11 although randomized studies have not shown improvement in overall survival.12

Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) elicit responses through direct killing (ie, apoptosis induction) or via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) or antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis mechanisms. Targeted Fc engineering either by glycosylation or by mutagenesis increases molecular affinity toward CD16 (Fcγ receptor IIIa [FcγRIIIa]) on natural killer (NK) cells and has been shown to potentiate NK-mediated ADCC.13 Also, coengagement of AML target cells via CD33, and NK cells via CD16, has been shown to result in increased cytotoxicity of the target cells.14 In addition to CD16 engagement, we evaluated whether receptor-ligand interactions between blasts and effectors can potentiate NK-mediated cytotoxicity against AML blasts. Leukemic cells downregulate ligands for the NK-cell–activating receptor NKG2D as a mechanism for evading NK-mediated ADCC.15,16 However, treatment of blasts with histone deacetylase inhibitors and hypomethylating agents has been shown to upregulate NKG2D ligand (NKG2DL).15 In the setting of hypomethylating agents, upregulation of NKG2DL was attributed to promoter DNA demethylation and DNA damage and correlates with improved NK cytotoxicity.17,18 Whether agents that upregulate NKG2DL on AML blasts could also enhance the efficacy of Fc-engineered antibodies is unknown. Here, we sought to evaluate whether hypomethylating agents such as decitabine (DAC) or azacytidine modulate susceptibility of AML blasts to Fc-engineered mAb directed against CD33.

BI 836858 is a fully human anti-CD33 antibody, which is Fc engineered for increased binding to FcγRIIIa. It binds with low nanomolar affinity to human CD33 and displays decelerated internalization kinetics compared with previously developed CD33 mAbs, thus making it suitable for exploitation of NK-mediated ADCC. We report here potent single-agent NK-cell–mediated ADCC activity of BI 836858 against primary CD33+ AML blasts. Given that hypomethylating agents are commonly used in older patients, we wanted to evaluate whether DAC modulates BI 836858–mediated cytotoxicity. In vitro addition of DAC or azacytidine did not inhibit BI 836858–mediated ADCC. We then analyzed serial bone marrow samples from patients who received a 10-day regimen of DAC. BI 836858 mediated higher ADCC in post-DAC (day 28) samples than pre-DAC treatment. We show that day 28 samples show increased expression of ligands for NKG2D (an activating receptor for NK cells); blocking of NKG2DL diminished BI 836858–mediated ADCC. Our studies highlight that DAC increases susceptibility of AML blasts to an Fc-engineered anti-CD33 antibody, providing a rationale for combination therapy of BI 836858 with azanucleosides in the treatment of older AML patients.

Materials and methods

Primary AML samples

Under an Ohio State University Institutional Review Board (IRB)–approved protocol, newly diagnosed AML patients presenting with high leukocyte counts were consented to undergo leukapheresis to collect primary cells. The Ficoll-enriched mononuclear cells were cryopreserved and subsequently thawed and cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in supplemental Table 2 (available on the Blood Web site). Some patients were treated with DAC as part of IRB-approved clinical trials (OSU-0336, OSU-07017). Patients received 20 mg/m2 DAC IV daily on days 1 to 10 and this cycle was repeated every 28 days. Bone marrow samples were collected prior to treatment with DAC, and on days 4, 11, and 28 post-DAC.

NK-cell isolation

Human NK cells were enriched from the peripheral blood of healthy donors (American Red Cross) with the Rosette-Sep NK-cell Enrichment Cocktail (StemCell Technologies) and Ficoll-Paque Plus centrifugation (Amersham/GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). For autologous assays, frozen apheresed AML samples were thawed and stained with anti-human CD56, CD3, and CD45 antibodies, and NK cells were sorted as SSClowCD45+CD3−CD56+ on Aria II fluorescence-activated cell sorter, with Sytox used in the process for dead cell exclusion.

mAbs

BI 836858 was derived by immunizing human antibody producing transgenic mice.19 BI 836858 is Fc engineered through the introduction of 2 amino acid substitutions in the Fc CH2 domain of the wild-type IgG1 via quick change mutagenesis.20 BI 836847 is an isotype-matched, Fc-engineered control antibody which does not bind human cells. Lintuzumab (HuM195), an IgG1-type humanized mAb directed against human CD33, was constructed from a published sequence.21 Antibodies were expressed in dihydrofolate reductase–deficient Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) DG44 suspension cells under serum-free conditions and purified via MabSelect Protein A affinity chromatography (GE Healthcare). Additional details about use of HDXMS and the internalization assay are described in the supplemental Methods.

CD107a assay

CD107a is a lysosome-related protein that traffics to the cell membrane when the NK cells are activated and degranulates by releasing cytolytic granules into target cells.22 Therefore, CD107a expression serves as a surrogate for the cytotoxic potential of NK cells. HL60 or primary AML patient cells were incubated with BI 836858 or BI 836847 (nonbinding Fc-engineered isotype control; BI47) mAbs at the concentration of 5 μg/mL for 30 minutes on ice, and then washed and cocultured at an effector-to-target (E:T) ratio of 2:1 with 0.5 million allogeneic NK cells enriched from leukopacks of healthy donors or autologous NK cells isolated from AML samples. CD107a antibody (BD Biosciences, clone:H4A3) was added and cocultured for 1 hour, then monensin (eBioscience) at a final concentration of 2 µM was added and incubated with cells for an additional 3 hours. Cells were then harvested, stained for NK cells (CD3−CD56+), and analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of CD107a+ cells gated on CD3−CD56+ NK cells is presented.

ADCC assay

ADCC was determined by standard 4-hour 51Cr-release assay. 51Cr-labeled (0.1 mCi 51Cr per million cells) target cells (5 × 103 primary AML samples or HL60 cells) per well were placed in 96-well plates after incubating them with mAbs (10 µg/mL, unless indicated otherwise) for 30 minutes. Effector cells (NK cells from healthy donors or autologous NK cells) were then added to the wells at E:T ratios of 3:1 (unless otherwise indicated). After 4-hour incubation, supernatants were removed and counted in a γ counter. The percentage of specific cell lysis was calculated by: percent lysis = 100 × (ER − SR)/ (MR − SR), where ER, SR, and MR represent experimental release (ER), spontaneous release (SR), and maximum release (MR), respectively.

NKG2DL receptor-blocking studies

The 51Cr-labeled target cells (5 × 103 cells per well) were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes with 10 μg/mL antibodies. For blocking with mAb, labeled target cells were preincubated for 30 minutes with either or in combination of MICA/B (Biolegend), ULBP-1 phycoerythrin (PE; R&D Systems), ULBP-2 PE (R&D Systems), ULBP-3 PE (R&D Systems), and its isotype controls. The unbound antibodies were washed off and 5 × 103 cells were added in 96-well plates. The effector NK cells at different E:T ratios were then added to the plates. ADCC activity was determined by standard 4-hour 51Cr-release assay (PerkinElmer). The supernatant was removed after the incubation and counted on a PerkinElmer Wizard γ counter. The percentage of specific cell lysis was determined as described previously.

Cell culture and treatment

Cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 media (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), and 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37°C, 5% CO2. Similarly, the AML blasts were cultured in the above-mentioned media in supplement with 10 ng/mL each of interleukin-3 (R&D Systems), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (R&D Systems), and stem cell factor (R&D Systems). Human NK cells or thawed AML blasts were treated with DAC at the concentration of 500 nM or 5-azacytidine at the concentration of 2 µM for 48 hours. Due to the instability of the drugs in solution, these drugs were reconstituted in vehicles and added to the culture medium daily.

NKG2DL expression analysis

RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Gibco BRL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and complementary DNA was generated using SuperScript (Life Technologies). The expression of NKG2D ligands ULBP-1, ULBP-2, ULBP-3, MICA, MICB, and the DNAM ligands (DNAML) PVR and Nectin-2 were assessed by real-time quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using a ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with TaqMan detection. The following primer/probe sets, all from Applied Biosystems were used: ULBP-1 (Hs00360941_m1), ULBP-2 (Hs00607609_mH), ULBP-3 (Hs00225909_m1), MICA (Hs00741286_m1), MICB (Hs00792952_m1), Nectin-2 (Hs01071562_m1), and PVR (Hs00197846_m1). CIR-neo and its transfectants (generously gifted by V.G., Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) were used as positive control for the ligands. The messenger RNA transcript analysis for NKG2DL was performed using primers mentioned in a published protocol.23 The NKG2DL and DNAML transcript levels were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and the 2ΔΔCt (cycle threshold [Ct]) method was used for determination of fold change.

Flow cytometry

Primary AML cells were suspended in flow buffer (phosphate-buffered saline plus 1% FBS) and incubated with specific fluorochrome-labeled antibodies at 4°C for 30 minutes. CD33-BV421 (Biolegend) and CD34-BV421 (Biolegend) antibodies were used. The cells were then washed with flow buffer. The samples were run on a Gallios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and analyzed using Kaluza 1.2 software (Beckman Coulter).

Statistical analysis

For the in vitro cell line experiments, data were analyzed by analysis of variance. For experiments comparing intrapatient variability in various treatment conditions, data were analyzed by mixed effect models, incorporating observational dependencies for the same subject.24 The Holm method was used to adjust the multiplicities to control the type I family-wise error rate at 0.05.25 NKG2DL expression by RT-PCR was normalized to internal control glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Normalized data were analyzed by using the mixed effect model, incorporating repeated measures for each subject. The primary test results (difference in gene expression between pre-DAC and day 28 post-DAC) are summarized by fold change in table format. Statistical analyses were conducted by using SAS 9.4 (SAS, Inc).

Results

CD33-directed Fc-engineered BI 836858 antibody has decelerated internalization, and binds a different CD33 epitope than nonengineered HuM195

BI 836858 is a fully human anti-CD33 antibody which was derived by Fc engineering of BI 836854, a standard IgG1-type antibody derived from human antibody-producing transgenic mice. To assess the effect of antibody incubation on the level of cell surface CD33, we initially compared BI 836858 to BI 836854 and later on to HuM195 (lintuzumab), an independent CD33-directed humanized IgG1 mAb. Incubation of HL60 cells with all 3 mAbs results in decreased CD33 molecules on the cell surface in a time-dependent manner, indicative of internalization of mAb/CD33 complexes. Interestingly, BI 836858 showed a higher degree of retained cell surface CD33 compared with HuM195 (Figure 1B), whereas the non–Fc-engineered version BI 836854 showed similar levels as BI 836858 (not shown); in addition, the non–FC-engineered antibody BI 836854 also had higher surface expression of CD33 in comparison with lintuzumab (supplemental Figure 1A). From these findings, we conclude that the difference in cell surface–retained CD33 observed between BI 836858 and HuM195 is not due to Fc engineering. To investigate whether binding to different regions of CD33 may cause the difference in CD33 surface retention, epitope mapping was performed by direct competition experiments and HDXMS. A structural model was calculated based on Siglec-3. Predicted epitopes for BI 836858 (blue) and HuM195 (red) are depicted in Figure 1A.26 The results demonstrate that BI 836858 and HuM195 bind to nonoverlapping amino acid residues in the N-terminal region of CD33.

Comparison of Fc-engineered anti-CD33 antibody BI 836858 and nonengineered HuM195. (A) Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDXMS) analysis of BI 836858 and HuM195 complexed with CD33. Protection from D2O exchange when bound to CD33 mapped onto the structure of CD33. Blue region indicates protection of CD33 by BI 836858; red region indicates protection by HuM195. Resolution of the method is determined by the peptides produced by digestion with pepsin. The antibodies bind to nonoverlapping amino acid residues in the N-terminal region of CD33. A structural model was calculated based on Siglec-526 ; the predicted epitopes for BI 836858 (blue) and Hum195 (red) are depicted. (B) Effect of BI 836858 and HuM195 on CD33 surface retention on HL60 cells. Cell surface–bound IgG was determined at indicated time points with a secondary fluorescence-labeled anti-IgG antibody and data were normalized against time point 0. The means of 6 independent experiments are shown. Incubation of HL60 cell lines with both antibodies results in decreased CD33 surface exposure over time, indicative of internalization of antibody/CD33 complexes. BI 836858 shows significantly higher CD33 levels over time compared with HuM195. (C) ADCC activity on HL60 cells at an E:T ratio of 20:1; peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy individuals were used as effectors. (D) Summary of ADCC on leukemia cell lines and primary AML blasts. BI 836858 displays superior efficacy of cytolysis compared with HuM195 under identical experimental conditions in both AML cell lines and 6 primary AML samples. Healthy donor NK cells were used as effectors and the 51Cr-labeled ADCC assay was done to measure cytotoxicity.

Comparison of Fc-engineered anti-CD33 antibody BI 836858 and nonengineered HuM195. (A) Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDXMS) analysis of BI 836858 and HuM195 complexed with CD33. Protection from D2O exchange when bound to CD33 mapped onto the structure of CD33. Blue region indicates protection of CD33 by BI 836858; red region indicates protection by HuM195. Resolution of the method is determined by the peptides produced by digestion with pepsin. The antibodies bind to nonoverlapping amino acid residues in the N-terminal region of CD33. A structural model was calculated based on Siglec-526 ; the predicted epitopes for BI 836858 (blue) and Hum195 (red) are depicted. (B) Effect of BI 836858 and HuM195 on CD33 surface retention on HL60 cells. Cell surface–bound IgG was determined at indicated time points with a secondary fluorescence-labeled anti-IgG antibody and data were normalized against time point 0. The means of 6 independent experiments are shown. Incubation of HL60 cell lines with both antibodies results in decreased CD33 surface exposure over time, indicative of internalization of antibody/CD33 complexes. BI 836858 shows significantly higher CD33 levels over time compared with HuM195. (C) ADCC activity on HL60 cells at an E:T ratio of 20:1; peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy individuals were used as effectors. (D) Summary of ADCC on leukemia cell lines and primary AML blasts. BI 836858 displays superior efficacy of cytolysis compared with HuM195 under identical experimental conditions in both AML cell lines and 6 primary AML samples. Healthy donor NK cells were used as effectors and the 51Cr-labeled ADCC assay was done to measure cytotoxicity.

BI 836858 shows high-affinity binding to leukemic cell lines and primary AML cells, and displays superior ADCC compared with HuM195

BI 836858 binds CD33 on cell lines and primary blasts with low nanomolar affinity as determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter Scatchard analysis (supplemental Table 1). Of note, the average CD33 antigen density on AML cell lines was clearly higher than on primary AML cells. Direct comparison of the cytolytic activity of the engineered antibody BI 836858 to BI 836854, the non–Fc-engineered parental mAb, in the presence of peripheral blood mononuclear cell effector cells clearly indicated an increase in ADCC due to Fc engineering (supplemental Figure 1B). This is in line with previously reported data for a CD37-specific antibody.19 In a next step, the ADCC of BI 836858 was tested on a panel of AML cell lines and primary AML blasts and compared with the reference antibody, HuM195 (Figure 1C-D). BI 836858 displayed higher cytolytic activity than HuM195 on all tested primary AML samples and cell lines. It is noteworthy that there were 4 samples (cell lines MV4-11 and TF-1; primary samples E and F) where BI 836858 still displayed significant ADCC whereas HuM195 was devoid of ADCC. The 50% inhibitory concentration of BI 836858 on HL60 cells is about 5 ng/mL (0.2 nM). To further assess the effect of varying E:T ratios on cytolytic activity, different E:T ratios from 3:1 to 25:1 were evaluated (supplemental Figure 2). Although the highest activity was observed at a ratio of 25:1, significant activity was still observed at the lowest tested ratio of 3:1, suggesting potent activity of BI 836858 even at low E:T ratios. The low 3:1 E:T ratio was used in subsequent ADCC assays. As AML cells have been shown to be negative for HER-2 expression,27 the therapeutic IgG1 antibody Herceptin targeting HER-2 was used as a negative control.

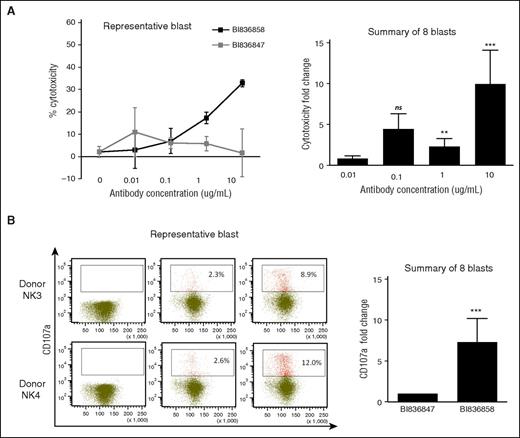

To further characterize the NK-cell–mediated ADCC activity by BI 836858 against primary AML blasts, we compared BI 836858 with Fc-engineered isotype control. As shown in Figure 2, BI 836858 induced concentration-dependent ADCC effects while the isotype control antibody BI 836847 showed only minimal effects that were not concentration dependent. With n = 8 primary samples, ADCC was 10-fold higher at 10 µg/mL (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.2-23.7; P < .0001); 4.5-fold higher at 1 µg/mL (95% CI, 1.9-10.6; P = .003), and 2.3-fold higher at 0.1 µg/mL (95% CI, 1.0-5.5; P = .106) (Figure 2A). Furthermore, NK cells that were cocultured with BI 836858–coated AML blasts exhibited significantly increased degranulation, as evidenced by upregulation of CD107a expression compared with those cocultured with BI 836847–coated AML blasts, indicating the potent induction of NK activation by BI 836858 against AML blasts (7.3-fold higher; 95% CI, 3.2-16.9; P < .0001; n = 8) (Figure 2B).

BI 836858 elicits potent NK-cell–mediated ADCC effect as well as NK-cell activation against primary AML blasts. (A-B) AML primary blasts were precoated with different concentrations of BI 836858, and then cocultured with NK cells from healthy donors at an E:T of 3:1 for the ADCC assays. The Fc-engineered, nonbinding BI 47 antibody was used as negative control antibody at the same E:T for comparison. Representative cytotoxicity for 1 blast donor (A) and summary fold changes for 8 different donors (B) data are shown. (C-D) AML primary blasts were precoated with 5 μg/mL BI 836858 or BI 836847, and then cocultured with NK cells at an E:T of 2:1 for the CD107a assays. Representative CD107a expression for 2 donors (C) and summary fold changes for 8 different donors (D) are shown. *P < .0001, **P < .01, ***P < .001. ns, not significant.

BI 836858 elicits potent NK-cell–mediated ADCC effect as well as NK-cell activation against primary AML blasts. (A-B) AML primary blasts were precoated with different concentrations of BI 836858, and then cocultured with NK cells from healthy donors at an E:T of 3:1 for the ADCC assays. The Fc-engineered, nonbinding BI 47 antibody was used as negative control antibody at the same E:T for comparison. Representative cytotoxicity for 1 blast donor (A) and summary fold changes for 8 different donors (B) data are shown. (C-D) AML primary blasts were precoated with 5 μg/mL BI 836858 or BI 836847, and then cocultured with NK cells at an E:T of 2:1 for the CD107a assays. Representative CD107a expression for 2 donors (C) and summary fold changes for 8 different donors (D) are shown. *P < .0001, **P < .01, ***P < .001. ns, not significant.

In vitro pretreatment of AML blasts with DAC or 5-azacytidine does not inhibit BI 836858–mediated ADCC or autologous NK-cell activation

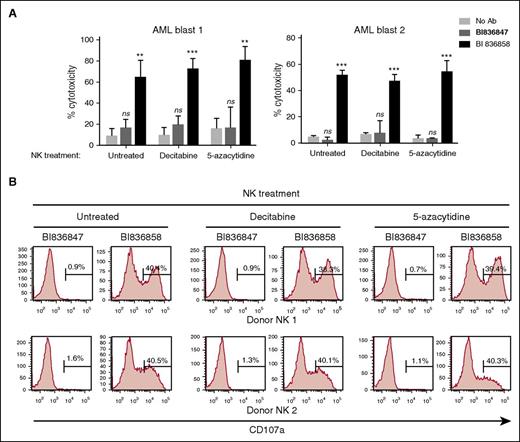

To evaluate whether BI 836858 can be used in combination with DAC or 5-azacytidine, we pretreated primary AML blasts with DAC or 5-azacytidine and evaluated the efficacy of BI 836858–induced autologous NK-cell activation as measured by induction of CD107a and ADCC. Representative data from 2 patients of a total of 8 patients assessed are shown in Figure 3. As shown in Figure 3, pretreatment of AML blasts with DAC or 5-azacytidine up to 48 hours in vitro did not significantly alter BI 836858–induced autologous NK-cell degranulation or BI 836858–induced ADCC by autologous NK cells compared with untreated target cells.

Pretreatment of NK effector cells with DAC or 5-azacytidine did not compromise BI 836858–mediated ADCC or NK-cell activation against AML blasts. NK cells from patients were exposed to DAC (500 nM) or 5-azacytidine (2 µM) for 48 hours before incubation with AML blasts coated with BI 836858 or BI 836847 for the ADCC assay (10 μg/mL, E:T = 3:1; A) or CD107a assay (5 μg/mL, E:T = 2:1; B). Shown are representative data of autologous NK cells and AML primary blasts from 2 patients. **P < .01, ***P < .001. ns, not significant.

Pretreatment of NK effector cells with DAC or 5-azacytidine did not compromise BI 836858–mediated ADCC or NK-cell activation against AML blasts. NK cells from patients were exposed to DAC (500 nM) or 5-azacytidine (2 µM) for 48 hours before incubation with AML blasts coated with BI 836858 or BI 836847 for the ADCC assay (10 μg/mL, E:T = 3:1; A) or CD107a assay (5 μg/mL, E:T = 2:1; B). Shown are representative data of autologous NK cells and AML primary blasts from 2 patients. **P < .01, ***P < .001. ns, not significant.

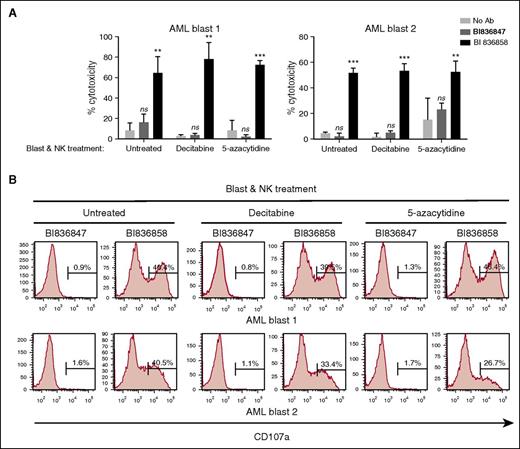

Pretreatment of both AML blasts and allogeneic NK effector cells with DAC or 5-azacytidine does not inhibit BI 836858–mediated ADCC or NK-cell activation

In patients treated with DAC or 5-azacytidine, NK cells and AML blasts are expected to be simultaneously exposed to these agents. This warranted evaluation of the effect of pretreatment of both NK cells and blast cells with DAC or 5-azacytidine on BI 836858–mediated NK-cell activation and ADCC. Due to the relatively low numbers of autologous NK cells that could be obtained from thawed apheresis samples, we used allogeneic NK cells when there were inadequate numbers of autologous NK cells. Dead blasts due to DAC or 5-azacytidine treatments were excluded and the NK-cell ADCC activity and NK-cell activation mediated by BI 836858 or control antibody BI 836847 were evaluated using viable blasts and NK cells from healthy donors. Primary AML blasts coated with BI 836858 significantly increased NK-cell activation when compared with control antibody; prior treatment of both target and effector cells with DAC or 5-azacytidine did not affect BI 836858–mediated ADCC and NK-cell activation (Figure 4). These results suggest that short-term in vitro culture of AML blasts with DAC or 5-azacytidine does not result in significant immune modulation.

Pretreatment of both AML blasts and NK effector cells with DAC or 5-azacytidine does not inhibit BI 836858–mediated ADCC or NK-cell activation. Both NK cells from healthy donors and AML blasts were exposed to DAC (500 nM) or 5-azacytidine (2 µM) for 48 hours before AML blasts were coated with BI 836858 or BI 836847 and coincubated for the ADCC assay (10 µg/mL, E:T = 3:1; A) or CD107a assay (5 µg/mL, E:T = 2:1; B). Shown are representative data of NK cells from 2 donors against 2 AML primary blasts. **P < .01, ***P < .001. ns, not significant.

Pretreatment of both AML blasts and NK effector cells with DAC or 5-azacytidine does not inhibit BI 836858–mediated ADCC or NK-cell activation. Both NK cells from healthy donors and AML blasts were exposed to DAC (500 nM) or 5-azacytidine (2 µM) for 48 hours before AML blasts were coated with BI 836858 or BI 836847 and coincubated for the ADCC assay (10 µg/mL, E:T = 3:1; A) or CD107a assay (5 µg/mL, E:T = 2:1; B). Shown are representative data of NK cells from 2 donors against 2 AML primary blasts. **P < .01, ***P < .001. ns, not significant.

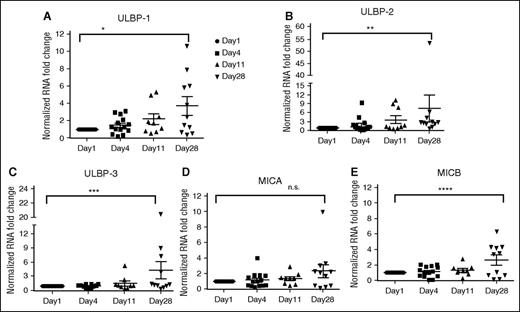

Upregulation of NKG2DL in AML patients treated with DAC

Because DAC-mediated changes require epigenetic modulation, we speculated that short-term culture of blasts with DAC was not adequate to observe epigenetic changes. Hence, we sought to evaluate samples from patients who received DAC on clinical trials (OSU-0336; OSU-0717). DAC (20 mg/m2) was administered daily IV from days 1 to 10 as part of a 28-day cycle. Patients underwent bone marrow biopsies pre-DAC, days 1, 4, 11, and 28. Blast percentages in pre- and post-DAC samples were assessed; blasts percentages ranged from 22% to 94% in the pre-DAC samples and ranged from 11% to 46% in the post-DAC samples. We evaluated NKG2DL expression by messenger RNA on days 1, 4, 11, and 28 in 18 patients. We noted expression of at least 1 NKG2DL (ULBP-1, ULBP-2, ULBP-3, MICA, or MICB) in all of the samples at day 28 but not on days 4 or 11 post-DAC treatment (Figure 5; supplemental Table 3). ULBP1 expression increased by 2.17-fold (95% CI, 1.25-3.73; P = .0069) on day 28 of the first cycle of DAC treatment. ULBP-2 expression increased by 2.88-fold (95% CI, 1.54-5.37; P = .0016) and ULBP-3 expression increased 2.04-fold (95% CI, 1.2-3.45; P = .0101) at this same time point. There was a trend toward increased expression of MICA (P = .0547), although it was not statistically significant. Overall, expression of NKG2DLs was significantly higher on day 28 compared with day 1 (Figure 5; supplemental Table 3).

Evaluation of NKG2DL expression in patients treated with DAC for 10 days. Expression analysis of NKG2DL by RT-PCR on AML blasts from patients treated with DAC. In DAC-treated patients, NKG2DL expression is significantly higher at the end of cycle 1 (day 28) compared with day 4 or day 11 of treatment. (A-E) Expression of ULBP-1, ULBP-2, ULBP-3, MICA, and MICB (*P = .0069, **P = .0016, ***P = .0101, n.s. P = .0547, ****P = .03). Upregulation of NKG2DL during DAC treatment was noted; expression of DNAM ligands (PVR and Nectin-2) was not observed.

Evaluation of NKG2DL expression in patients treated with DAC for 10 days. Expression analysis of NKG2DL by RT-PCR on AML blasts from patients treated with DAC. In DAC-treated patients, NKG2DL expression is significantly higher at the end of cycle 1 (day 28) compared with day 4 or day 11 of treatment. (A-E) Expression of ULBP-1, ULBP-2, ULBP-3, MICA, and MICB (*P = .0069, **P = .0016, ***P = .0101, n.s. P = .0547, ****P = .03). Upregulation of NKG2DL during DAC treatment was noted; expression of DNAM ligands (PVR and Nectin-2) was not observed.

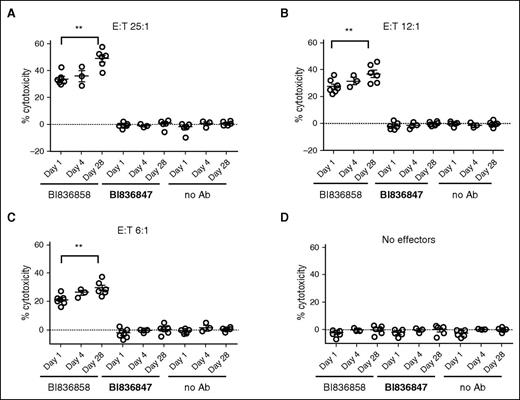

BI 836858–mediated ADCC is increased in primary AML blasts on day 28 post-DAC compared with pre-DAC blasts

We wanted to evaluate whether DAC treatment increased susceptibility of AML blasts to ADCC mediated by NK cells through BI 836858. Hence, we evaluated BI 836858–mediated ADCC on bone marrow samples obtained from AML patients’ pre- and post-DAC treatment. As shown in Figure 6, we consistently noted an increase in BI 836858–mediated cytotoxicity in day 28 samples compared with pre-DAC samples (P < .0001) when healthy donor NK cells were used as effectors (there were insufficient autologous NK cells to perform these assays). Each subpanel in Figure 6 shows ADCC on days 1, 4, and 28 of DAC treatment. Higher E:T ratios (25:1) were associated with higher ADCC; E:T ratios of 6:1 still resulted in significant BI 836858–specific cytotoxicity.

Higher BI 836858–mediated ADCC in day 28 post-DAC blasts compared with pre-DAC samples. Summary of ADCC data from 7 patients. As effectors, NK cells from healthy donors were used. Negative controls are no antibody (no Ab) and isotype-matched antibody BI 836847 (BI47). Different E:T ratios are shown with 25:1 (A), 12:1 (B), 6:1 (C), and no effectors (D).

Higher BI 836858–mediated ADCC in day 28 post-DAC blasts compared with pre-DAC samples. Summary of ADCC data from 7 patients. As effectors, NK cells from healthy donors were used. Negative controls are no antibody (no Ab) and isotype-matched antibody BI 836847 (BI47). Different E:T ratios are shown with 25:1 (A), 12:1 (B), 6:1 (C), and no effectors (D).

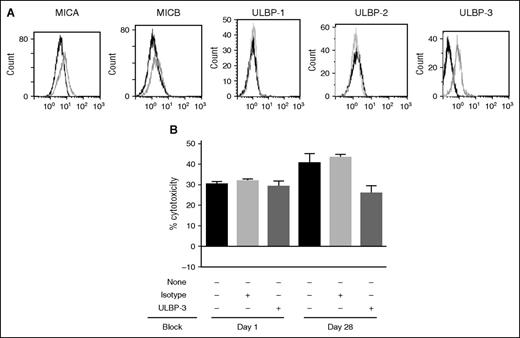

Blocking of NKG2DL on day 28 samples abrogates BI 836858–mediated ADCC

We hypothesized that increased expression of NKG2DL was one of the mechanisms whereby DAC-treated samples showed higher BI 836858–mediated ADCC. Consistent with this hypothesis, blocking of DAC-induced ULBP-3 in a day 28 post-DAC treatment sample (Figure 7A) with ULBP-3 blocking antibody resulted in reduced BI 836858–mediated ADCC comparable to pre-DAC treatment (Figure 7B).

Blocking of NKG2DL receptor shows decrease in BI 836858 ADCC in post-DAC samples. (A) Surface expression of NKG2DL in patients who received DAC. The dark histograms show expression of MICA, ULBP-1, ULBP-2, and ULBP-3 at baseline, and the gray histograms show expression on day 28 post-DAC. (B) Blocking of surface expression of NKG2DL shows decrease in BI 836858–mediated ADCC in post-DAC samples. Surface expression of ULBP-3 was blocked in day 1 and day 28 samples. BI 836858–mediated ADCC was lower is samples where ULBP-3 was blocked.

Blocking of NKG2DL receptor shows decrease in BI 836858 ADCC in post-DAC samples. (A) Surface expression of NKG2DL in patients who received DAC. The dark histograms show expression of MICA, ULBP-1, ULBP-2, and ULBP-3 at baseline, and the gray histograms show expression on day 28 post-DAC. (B) Blocking of surface expression of NKG2DL shows decrease in BI 836858–mediated ADCC in post-DAC samples. Surface expression of ULBP-3 was blocked in day 1 and day 28 samples. BI 836858–mediated ADCC was lower is samples where ULBP-3 was blocked.

Discussion

Our studies show pharmacological activity of the novel, Fc-engineered, CD33 mAb BI 836858 against primary AML blasts, supporting the clinical application of this antibody in AML. BI 836858 induces NK-cell–mediated ADCC that is higher than that of HuM195, a previously developed, non–Fc-engineered anti-CD33 antibody. CD33 is an extensively studied candidate antigen that can serve as a therapeutic target for antibodies due to its frequent expression on AML blasts.4,28 Clinical trials have confirmed the validity of CD33 as a viable target for the treatment of AML.29 The antibody-drug conjugate GO has shown efficacy in older AML patients. In addition to GO, another agent in development was lintuzumab (HuM195), a humanized mAb (IgG1) directed against CD33.30 HuM195 showed signs of clinical efficacy in phase 1 trials.11 However, a randomized multicenter phase 3 trial showed that, although safe, the addition of HuM195 to salvage chemotherapy did not result in a statistically significant improvement in response rate or survival in patients with refractory/relapsed AML.12

ADCC is recognized as an important factor in the efficacy of other therapeutic mAbs such as obinutuzumab, recently approved for use in chronic lymphocytic leukemia.31 CD33 is a rapidly internalizing cell surface antigen,7 which may result in suboptimal ADCC activity of mAbs that bind it. An NK-engaging mAb is likely to provide superior ADCC if its internalization when bound to the target is minimal. BI 836858 was developed as an Fc-engineered mAb with enhanced affinity to human FcγRIIIa, leading to significantly higher NK-cell–mediated ADCC on cell lines and primary AML cells compared with HuM195. Initial internalization experiments have shown that BI 836858 and BI 836854, the non–Fc-engineered version of BI 836858, do not differ in their internalization behavior, resulting in comparable CD33 levels retained over time on the cell surface (not shown). It is noteworthy, however, that BI 836858 causes less reduction of cell surface CD33 than HuM195, which binds to a different epitope of CD33. This may contribute to the observed differences in internalization kinetics, resulting in higher levels of CD33 retained on the cell surface after incubation with BI 836858 compared with HuM195, which may further enhance the ADCC efficacy of BI 836858 when administered in vivo. Here, we demonstrate the ability of BI 836858 to induce NK-cell activation and potent NK-cell–mediated ADCC against AML primary blasts even at low E:T ratios, underscoring its potential for treatment as a single agent in AML.

In addition to antibody-based immunotherapy, hypomethylating agents have shown efficacy in AML. The cytidine nucleoside analogs DAC and 5-azacitidine are putative epigenetic modulators and their role in AML has been extensively studied.32-34 Besides DNA-hypomethylating and apoptosis-inducing activities that may contribute to clinical response, some studies suggest that DAC and 5-azacytidine have immunomodulatory activity.35,36 In addition to effects on NK cells, DAC enhances upregulation of ligands that increase susceptibility to NK-mediated ADCC. To elucidate the effect of these 2 drugs in the setting of BI 836858–based immunotherapy, we performed experiments in which either the AML blasts (target cells), NK cells (effector cells), or targets and effectors together were pretreated with these 2 drugs and BI 836858–mediated ADCC activity and NK-cell activation were evaluated. AML primary cells exposed to DAC or 5-azacytidine exposure remain sensitive to BI 836858–induced, NK-cell–dependent ADCC. In patients that received DAC, we consistently noted higher BI 836858–mediated ADCC at day 28 after start of DAC treatment compared with pre-DAC and this time point coincided with upregulation of NKG2D ligand(s) in primary leukemia samples from DAC-treated patients. We sought to evaluate the mechanism by which higher ADCC was observed post-DAC compared with pre-DAC. Although short-term incubation of AML blasts with DAC in vitro did not modulate NKG2DL expression (data not shown), upregulation of these molecules in 28-day post-DAC samples from in vivo–treated AML patients suggested NKG2DL expression may be epigenetically modulated and may take longer than what can be observed in short-term cultures ex vivo. In order to prove there was a cause-and-effect relationship, we performed blocking experiments and show that antibodies blocking binding of NKG2DL receptor decreased BI 836858–mediated ADCC. This suggests a biological rationale to combine BI 836858 with DAC or 5-azacytidine in treatment of AML patients; a clinical trial evaluating the combination of DAC and BI 836858 is expected to begin accrual this year (Clinicaltrials.gov; NCT 02632721). These findings may have implications in the combination of Fc-engineered mAbs and hypomethylating agents or NK-cell–based therapies in the management of AML.

One of the limitations of our study has been lack of serum samples to measure soluble NKG2DL. Although blasts express NKG2DL, they are also known to shed these factors as a mechanism to evade immune surveillance.37 Furthermore, studies are necessary to measure soluble NKG2DL in patients receiving DAC to evaluate whether shedding also is increased with DAC. Another limitation of the study is the paucity of available autologous NK cells and availability of blasts to detect surface expression of NKG2DL. Recent publications point to a qualitative defect in NK cells obtained from AML patients; an evaluation of 15 patients showed that NK cells at diagnosis show downregulation of activating receptors, upregulation of inhibitory receptors, reduced degranulation as evidenced by CD107a expression, and reduced cytotoxicity against autologous blasts.16 In 12 of the 15 patients who achieved remission, functionality of NK cells was restored, suggesting that AML blasts exert inhibitory effects on NK-cell function. Another limitation of this study is that these experiments were performed in unfractionated marrow samples. CD34 selection of marrow samples may have altered the findings; the low cell numbers precluded performing experiments on CD34-sorted cells. We show that DAC increases transcriptional induction of NKG2DL; limited availability of samples from patients who received DAC precluded elaborate analyses of protein and surface expression of NKG2DL. Detailed prospective, phenotypic analyses of NK cells and AML blasts in patients receiving hypomethylating agents would be useful to assess the role of hypomethylating agents in modulating NK-cell function and transcriptional regulation of NKG2DL.

In summary, we show that the novel, Fc-engineered, CD33 antibody BI 836858 has activity against primary AML blasts. We also show that DAC pretreatment renders the blasts more susceptible to BI 836858 and NK-mediated ADCC. These findings provide a strong rationale for the use of BI 836858 for AML treatment either as a single agent or in combination with the standard of care using DAC or 5-azacytidine.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute (CA135332, CA095426, and CA068458), Pelotonia, the intramural research program of the Ohio State Comprehensive Cancer Center (IRP 46050-501876) and the Lauber AML Research Fund. The authors gratefully acknowledge The Ohio State University Leukemia Tissue Bank Shared Resource for providing patient samples (P30CA016058).

Authorship

Contribution: S.V. and S.H. are co-first authors of the manuscript and equally contributed to the study’s conception, design, and analysis, interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript; C.C., B.G., and R.M. contributed to the design of the studies, and data collection and interpretation; V.G. provided cell lines; X.M. helped with statistical analysis and data interpretation; G.L., S.P.W., J.Y., M.A.C., W.B., and G.M. contributed to the study’s conception; K.-H.H., R.K., C.K., P.J.A., B.R., and E.B. contributed to study design; D.B. and D.M.L. provided access to samples and helped in writing the manuscript; N.M. contributed to the study’s conception, design, and analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, overall study supervision, and funding; and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.K., C.K., P.J.A., K.-H.H., and E.B. are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim RCV, Vienna, Austria. B.R. is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH, Biberach/Riss, Germany. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Natarajan Muthusamy, Division of Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine, The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, 455E, 410 West 12th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210; e-mail: raj.muthusamy@osumc.edu.

References

Author notes

S.V. and S.H. contributed equally to this work.

K.-H.H., G.M., and N.M. are cosenior authors.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal