Key Points

Calreticulin mutants responsible for myeloproliferative neoplasms specifically activate the thrombopoietin receptor and in turn JAK2.

Activation of the thrombopoietin receptor requires the glycan binding site and a novel C-terminal tail of the mutant calreticulin.

Abstract

Mutations in the calreticulin gene (CALR) represented by deletions and insertions in exon 9 inducing a −1/+2 frameshift are associated with a significant fraction of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs). The mechanisms by which CALR mutants induce MPN are unknown. Here, we show by transcriptional, proliferation, biochemical, and primary cell assays that the pathogenic CALR mutants specifically activate the thrombopoietin receptor (TpoR/MPL). No activation is detected with a battery of type I and II cytokine receptors, except granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor, which supported only transient and weak activation. CALR mutants induce ligand-independent activation of JAK2/STAT/phosphatydylinositol-3′-kinase (PI3-K) and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways via TpoR, and autonomous growth in Ba/F3 cells. In these transformed cells, no synergy is observed between JAK2 and PI3-K inhibitors in inhibiting cytokine-independent proliferation, thus showing a major difference from JAK2V617F cells where such synergy is strong. TpoR activation was dependent on its extracellular domain and its N-glycosylation, especially at N117. The glycan binding site and the novel C-terminal tail of the mutant CALR proteins were required for TpoR activation. A soluble form of TpoR was able to prevent activation of full-length TpoR provided that it was N-glycosylated. By confocal microscopy and subcellular fractionation, CALR mutants exhibit different intracellular localization from that of wild-type CALR. Finally, knocking down either MPL/TpoR or JAK2 in megakaryocytic progenitors from patients carrying CALR mutations inhibited cytokine-independent megakaryocytic colony formation. Taken together, our study provides a novel signaling paradigm, whereby a mutated chaperone constitutively activates cytokine receptor signaling.

Introduction

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are clonal disorders that affect hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and lead to a pathologic expansion of the myeloid lineage, mainly platelets in essential thrombocythemia (ET), red blood cells in polycythemia vera (PV), or platelets with collagen fiber formation in primary myelofibrosis (PMF).1 The hallmark of these disorders is the constitutive activation of the JAK-STAT pathway.2,3 The first and most recurrent mutation was described in JAK2 (JAK2 V617F), and was found in PV, ET, and PMF patients. Activating thrombopoietin receptor (TpoR/MPL) mutations (W515K/R/L/A) are found in ET and PMF patients.4 Recently, mutations were described in the gene encoding the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) resident chaperone, CALR.5,6 These mutations affect the exon 9 and lead to the loss of its ER retention signal, KDEL, and the generation of a positively charged and Met-rich C-terminal sequence. CALR mutants have been identified in ET and PMF patients, being correlated with a marked thrombocytosis and pathologic megakaryocyte features. Furthermore, expression of the 2 most prevalent CALR mutants type I (52 bp deletion) and type II (5 bp insertion) in a retroviral mouse model led to an ET phenotype7 (and companion manuscript8 ). Interestingly, for type I CALR mutant, this ET phenotype evolved to myelofibrosis, in agreement with recent clinical observations.9,10

In the present study, we show that CALR mutants acquire the ability to activate TpoR, explaining the phenotype of the disease centered on megakaryocytes. We detail the requirements for this interaction and show that pathologic signaling via the JAK-STAT/PI3-K pathways appears different from that induced by JAK2V617F.

Materials and methods

DNA manipulations, production of retroviruses

The CALR wild-type, del52, ins5, and Δex9 sequences were cloned into pMSCV retroviral plasmids with mCherry. cDNAs coding for HA-tagged cytokine receptors TpoR (and mutants), EpoR, GCSFR, and all other receptors and JAK proteins were cloned in pMX-IRES-GFP as described.11 TpoR box 1 dead construct was previously described,12 and soluble TpoR was generated by adding a stop codon at W491. The TpoR Asn mutants were as described.13 Viral infections were performed as previously described.11 shRNA against JAK2 and MPL/TpoR cloned into PRRLsin-PGK-eGFP-WPRE lentiviral vector (Généthon, Evry, France) were used as previously described.14-16

Cell lines

The murine Ba/F3 cells were grown and infected as described.11 Ba/F3-TpoR, EpoR, and G-CSFR cell lines expressing the various CALR mutants were generated after viral infection and sorted for equal (GFP or mCherry) expression level (FACSAria III; BD Biosciences). γ2A JAK2-deficient fibrosarcoma cells17 were used for transcriptional studies.11

calr−/− murine embryonic fibroblast cells (MEFs) were kindly provided by Dr Marek Michalak, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.18

Transcriptional assays

Dual luciferase assay was performed in γ2A cells transfected with cDNAs coding for STAT5, JAK2, and the respective cytokine receptor and CALR wild-type, mutants, or empty vector11 ; pRL-TK was used as an internal control (Promega, Madison, WI). Reporters used were Spi-Luc,19 pGRR5, pSRE, and pFOXO (6xDBE).11 Stimulations were with the appropriate cytokine (10 ng/mL rhTpo [Milteneyi Biotec], 10 U/mL rhEpo [Eprex; Hospital pharmacy], 10 ng/mL rhGCSF [Milteneyi Biotec]).

Growth assays

5000 cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates in medium with the indicated doses of cytokine and assayed at day 3, by the CellTiter-Glo luminescent Cell Viability Assay reagent (Promega). To determine long-term cytokine independence of transduced Ba/F3, cells were plated at a density of 250 000/mL, and live cells were evaluated after 10 days of culture by cell counting using a Coulter counter.

Cell surface immunoprecipitation

Ba/F3 cells were incubated with anti-HA antibodies (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) for 1 hour at 4°C, and washed 3 times and lysed in NP40 buffer with 100 µM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 100 µM orthovanadate, and a cocktail of protease inhibitor. The lysate was incubated with protein G agarose (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) overnight at 4°C. The beads were washed and subjected to western blotting with the indicated antibodies.

Coimmunoprecipitation

NP40 extracts from HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with TpoR and CALR wild-type or del52 by calcium phosphate and incubated with anti-HA antibodies (Roche) overnight at 4°C. Protein G agarose (Invitrogen) beads were added and incubated for 2 hours at 4°C. The beads were washed and subjected to western blotting with the indicated antibodies.

Antibodies

Phospho-specific antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technologies, as described,11 and anti-CALR antibodies were from Millipore. β-actin (Sigma) was used as loading control. Antibodies detecting HA were from Roche.

Endo-H digestion

Endo-H (endoglycosidase H) digestion was performed as previously described on NP40 extracts from Ba/F3 cell lines.12

Patients

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. CD34+ cells from the peripheral blood of ET patients, with different CALR mutants identified by fragment sizing and Sanger sequencing, were purified by cell sorting and were transduced for lentiviral delivery of MPL and JAK2 short hairpin RNAs. Two days later, sorted cells were evaluated on a serum-free fibrin clot assay to quantify megakaryocyte colonies in the presence of stem cell factor alone or with Tpo.20 Effect of short hairpin RNAs on MPL/TpoR and JAK2 mRNA levels was measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction in the plated cells.

Split-luciferase (Gaussia princeps) complementation assay

The cDNA of murine wild-type JAK2 was inserted between Notl and Clal restriction sites of pcDNA3.1/Zeo vector upstream of either the hGluc fragment coding amino acids 1-93 (hGluc1) or the fragment coding amino acids 94-169 (hGluc2) of Gaussia princeps luciferase as described.21

BOSC 23 cells were transfected and processed as described.22

Confocal microscopy

calr−/− MEFs grown overnight on coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, were permeabilized, and were blocked with 0.5% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline containing 100 µg/mL of goat γ-globulin (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories [Bio Connect], Huissen, The Netherlands) for 1 hour at room temperature. Rabbit anti-CALR (Millipore [Merck Chemicals], Overijse, Belgium) and mouse anti-Calnexin (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) were incubated overnight at 4°C followed by goat anti-mouse IgG coupled to Alexa 568 or goat anti-rabbit IgG linked to Alexa 488 (Invitrogen/Life Technologies, Gent, Belgium). Slides were examined by confocal microscopy using a confocal server spinning disc Zeiss platform equipped with a ×100 objective.

Cell fractionation

calr−/− MEF cells (5 × 107) stably expressing TpoR and CALR wild-type or del52 were harvested in 2 mL of homogenization medium (0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 3 mM imadazole, pH 7) and homogenized on ice with a tight Dounce homogenizer (6 strokes).23

After removal of nuclei and cell debris at 7700 gxmin, subcellular particles sedimenting at 7 × 106gxmin were layered on top of preformed sucrose density gradients and equilibrated for 105 × 106gxmin. Twelve fractions were collected from the bottom and analyzed for density and by western blotting. Fractionation of the 2 cell lines was performed strictly in parallel. Representative data are from 2 experiments.

Inhibitor assays

Ruxolitinib, erismodegib, buparlisib, and panobinostat (SelleckChem); rapamycin and temsirolimus (Tocris); and the other 17 compounds (SynMedChem) were dissolved in 100% dimethylsulfoxide (Sigma) to prepare 20 mM stocks except for NVP-BEZ235, which was dissolved to prepare 10 mM stock. Combination studies were performed24 in the presence or absence of Tpo (40 ng/mL).Cell viability was determined by CellTiter-Glo (Promega). Combination index (CI) was calculated using the CompuSyn software version 1.0 (ComboSyn Inc). CI values of ≤0.8 show moderate to strong synergism.25 CIs were calculated as described.24

Results

CALR mutants specifically activate TpoR

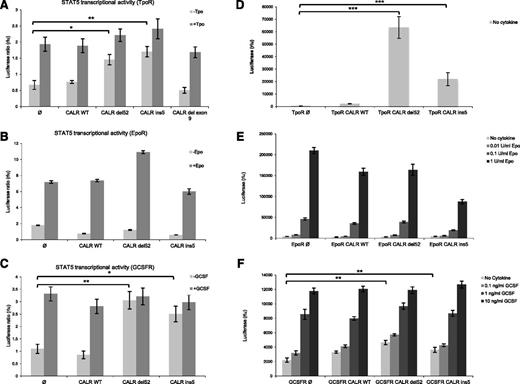

CALR is an ER-resident chaperone implicated in the folding of newly synthetized proteins through binding to their N-glycosylated sites.26 We hypothesized that the CALR mutants associated with MPN might bind to and activate cytokine receptors, which are highly N-glycosylated12,13,27 and because MPNs are known to be driven either by indirect (JAK2V617F) or direct (TpoR W515L/A/K and S505N) cytokine receptor activation.2 To test this hypothesis, we measured STAT5 transcriptional activity in γ2A cells transiently transfected with CALR wild-type or mutants along with a cytokine receptor, such as TpoR, EpoR, and GCSFR, or a battery of type I and II cytokine receptors. As shown in Figure 1B, CALR mutants do not induce constitutive STAT5 activation via EpoR. In contrast, they specifically induce STAT5 constitutive activation downstream of TpoR and GCSFR (Figure 1A,C). TpoR-dependent STAT5 activation was induced by the 2 most common MPN-associated mutants of CALR, type I (del52) and type II (ins5), but not by an artificial mutant lacking the entire exon 9 (Δex9). These results were confirmed using a pan STAT1/3/5 luciferase reporter (pGRR5), but the activation via GCSFR was shown to be weaker (data not shown). In supplemental Figure 1A-E (available on the Blood Web site), we show that no STAT5 activation by CALR mutants could be detected via IL-2R, IL-9R, growth hormone receptor, leptin receptor, and type I interferon receptors.

CALR mutants specifically activate TpoR, leading to cell transformation. γ2A cells were transfected with JAK2, STAT5, and CALR wild-type (wt) or the indicated mutants in the presence of TpoR (A), EpoR (B), and GCSFR (C). Luciferase assay was performed using the firefly reporter, Spi-Luc/STAT5 (STAT5-luc) and pRL-TK renilla luciferase for normalization. Ba/F3 cells stably transduced with CALR constructs together with TpoR (D), EpoR (E), or GCSFR (F) were cultured for 3 days, in the absence of cytokines. Positive controls of Epo and GCSF treatment are shown for Ba/F3 EpoR and GCSFR cells, respectively. Relative viability was measured using CellTiter-Glo technology. Statistical analysis (jmp pro11) was performed by the nonparametric multiple comparisons Steel test with a control group; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

CALR mutants specifically activate TpoR, leading to cell transformation. γ2A cells were transfected with JAK2, STAT5, and CALR wild-type (wt) or the indicated mutants in the presence of TpoR (A), EpoR (B), and GCSFR (C). Luciferase assay was performed using the firefly reporter, Spi-Luc/STAT5 (STAT5-luc) and pRL-TK renilla luciferase for normalization. Ba/F3 cells stably transduced with CALR constructs together with TpoR (D), EpoR (E), or GCSFR (F) were cultured for 3 days, in the absence of cytokines. Positive controls of Epo and GCSF treatment are shown for Ba/F3 EpoR and GCSFR cells, respectively. Relative viability was measured using CellTiter-Glo technology. Statistical analysis (jmp pro11) was performed by the nonparametric multiple comparisons Steel test with a control group; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

We further validated our data by stable transduction of Ba/F3 cells with TpoR, EpoR, or GCSFR along with wild-type CALR or mutants (Figure 1D-F). Because Ba/F3 cells are IL3-dependent requiring cytokines for their growth, we tested the capacity of CALR mutants to induce autonomous growth. We measured short-term growth of the stable Ba/F3 cell lines by using Cell Titer Glo assay after 3 days of IL-3 removal (Figure 1D-F). Long-term autonomous growth was also studied after 10 days of culture in the absence of cytokine. Although EpoR did not induce increased short- and long-term autonomous proliferation in CALR-mutated cells, interestingly, GCSFR supported a mild increase in short-term growth in CALR-mutated cells, but no long-term cytokine-independent proliferation was obtained after repeated attempts. Although CALR mutants did not induce autonomous growth in Ba/F3 cells expressing EpoR and GCSFR, cells did respond to their cytokines (Figure 1E-F). Only TpoR maintained long-term cytokine-independent cell growth in the presence of both CALR mutants (Figure 1D-F), as described in the companion paper.8

Altogether, these results suggest that CALR mutants induce strong and specific signaling via TpoR, leading to increased proliferation and autonomous growth.

JAK2 is required for TpoR activation by CALR mutants

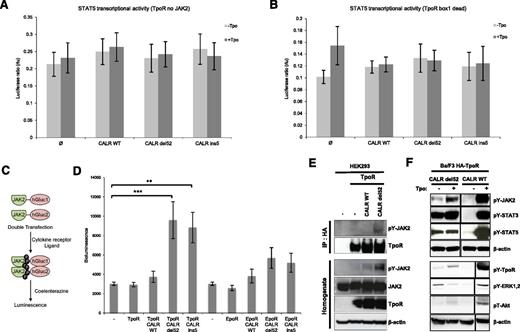

JAK2 is required for signaling by TpoR, as well as for its traffic and stability.12,28,29 To test whether JAK2 is required for TpoR activation by CALR mutants, we performed STAT5 transcriptional assays in the human JAK2-deficient γ2A cells in the absence of JAK2 or using a TpoR receptor mutant that does not bind JAK2. CALR mutants could not induce TpoR activation in the absence of JAK2 (Figure 2A). Furthermore, a TpoR box 1 dead mutant, which is deficient in JAK2 binding,12 was not able to activate JAK-STAT pathway in the presence of CALR mutants, indicating that the interaction between TpoR and JAK2 is crucial for signaling by CALR mutants (Figure 2B). In addition, we evaluated dimerization of the JAK2 C-terminal kinase domains by Gaussia luciferase complementation assay21,22 (Figure 2C). We show that, in transiently transfected HEK293 cells, CALR mutants induce dimerization of JAK2 C-terminal domains in the presence of TpoR, but not of EpoR (Figure 2D). This was accompanied by the phosphorylation of the JAK2 activation loop at Y1007 residue (Figure 2E). We also show by coimmunoprecipitation assay that TpoR is associated with phosphorylated JAK2 only when coexpressed with CALR del52 (Figure 2E). Furthermore, constitutive STAT3 and 5 activation was observed in Ba/F3 TpoR expressing CALR mutants by western blotting, along with detectable MAPK ERK1/2, and PI3-K signaling (Figure 2F). Constitutive activation of MAPK and PI3-K pathways was also seen by luciferase assay with pSRE and 6xDBE (supplemental Figure 2B-C). Interestingly, CALR mutant30 found in the MARIMO cell line and exhibiting the same −1/+2 frameshift was also capable of activating STAT5 and MAPK (supplemental Figure 2A-B).

Constitutive signaling of TpoR induced by CALR mutants is JAK2-dependent. JAK2 requirement for STAT5 transcriptional activation was tested by luciferase assay in JAK2-deficient cell, γ2A, transfected with CALR wild-type or mutants, STAT5, and TpoR. (A) CALR mutants were unable to induce STAT5 activation downstream of TpoR in the absence of JAK2. (B) This observation was confirmed by luciferase assay with the TpoR box 1 dead mutant deficient in JAK2 binding. (C) Schematic representation of Gaussia princeps luciferase complementation assay used to test JAK2 dimerization in HEK293-derived BOSC cells. (D) Close proximity between the C-terminal kinase domains of JAK2 activation is induced by CALR del52 and ins5 only in the presence of TpoR. Values shown represent the average of 3 pooled independent experiments, each performed with 3 biological replicates ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis (jmp pro11) was performed by the nonparametric multiple comparisons Steel test with a control group; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. (E) Immunoprecipitation using anti-HA antibody from lysates of HEK293 cells transiently transfected with respective CALR (wild-type or del52) and HA-TpoR constructs, followed by western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Phosphorylated form of JAK2 interacted with TpoR only in the presence of CALR del52 but not wild-type. (F) JAK2 (Y1007/1008), STAT3 (Y705), STAT5 (Y694), TpoR (Y626), ERK1/2, (T202/Y204) and Akt (T308) activation by CALR del52 in Ba/F3 cells in the absence of Tpo. The condition +Tpo for CALR wild-type probed with pY-TpoR, pY-ERK1/2, pT-AKT, and β-actin was run in the same gel, but before CALR del52 minus Tpo. It had been displaced for symmetry.

Constitutive signaling of TpoR induced by CALR mutants is JAK2-dependent. JAK2 requirement for STAT5 transcriptional activation was tested by luciferase assay in JAK2-deficient cell, γ2A, transfected with CALR wild-type or mutants, STAT5, and TpoR. (A) CALR mutants were unable to induce STAT5 activation downstream of TpoR in the absence of JAK2. (B) This observation was confirmed by luciferase assay with the TpoR box 1 dead mutant deficient in JAK2 binding. (C) Schematic representation of Gaussia princeps luciferase complementation assay used to test JAK2 dimerization in HEK293-derived BOSC cells. (D) Close proximity between the C-terminal kinase domains of JAK2 activation is induced by CALR del52 and ins5 only in the presence of TpoR. Values shown represent the average of 3 pooled independent experiments, each performed with 3 biological replicates ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis (jmp pro11) was performed by the nonparametric multiple comparisons Steel test with a control group; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. (E) Immunoprecipitation using anti-HA antibody from lysates of HEK293 cells transiently transfected with respective CALR (wild-type or del52) and HA-TpoR constructs, followed by western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Phosphorylated form of JAK2 interacted with TpoR only in the presence of CALR del52 but not wild-type. (F) JAK2 (Y1007/1008), STAT3 (Y705), STAT5 (Y694), TpoR (Y626), ERK1/2, (T202/Y204) and Akt (T308) activation by CALR del52 in Ba/F3 cells in the absence of Tpo. The condition +Tpo for CALR wild-type probed with pY-TpoR, pY-ERK1/2, pT-AKT, and β-actin was run in the same gel, but before CALR del52 minus Tpo. It had been displaced for symmetry.

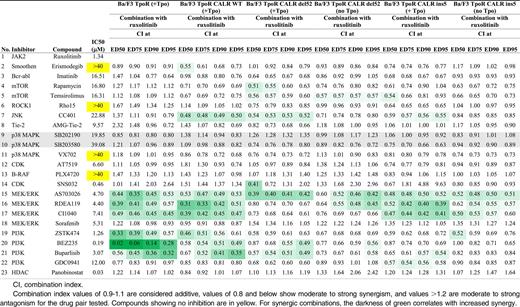

Absence of synergy between JAK2 and PI3-K inhibitors in the case of hematopoietic cell lines coexpressing TpoR and CALR mutants

We then studied which signaling pathways induced by CALR mutants were involved in autonomous proliferation of Ba/F3 TpoR cells by using different inhibitors. After 2 days of treatment, cells expressing mutated CALR (del52 and ins5) show increasing sensitivity toward ruxolitinib, when compared with wild-type CALR (supplemental Table 1). This is consistent with reports showing that JAK-STAT pathway inhibition by ruxolitinib and fedratinib inhibits constitutive signaling induced by CALR mutants.31-33

Then we tested whether ruxolitinib could synergize with the PI3-K inhibitors GDC-421, ZSTK474, and BEZ235 (also an mTOR inhibitor), as previously shown for JAK2V617F,24 and with a series of serine threonine kinase inhibitors to block growth of CALR mutants-expressing Ba/F3 TpoR cells (Table 1). In the absence of Tpo, using the Chou-Talalay method, no synergy was detected between JAK2 and PI3-K inhibitors. For del52 CALR mutant specifically, synergy was detected between JAK2 inhibitor and the mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus. Conversely, synergy between JAK2 and MEK-ERK inhibitors could be detected in CALR-mutants cells. Synergy was restored in the presence of Tpo, as described.24 These data indicate that signaling by CALR mutants depends mainly on JAK2 and MAP-kinase pathways, in contrast to JAK2V617F, which is heavily dependent on JAK2 and PI3-K.24,34,35

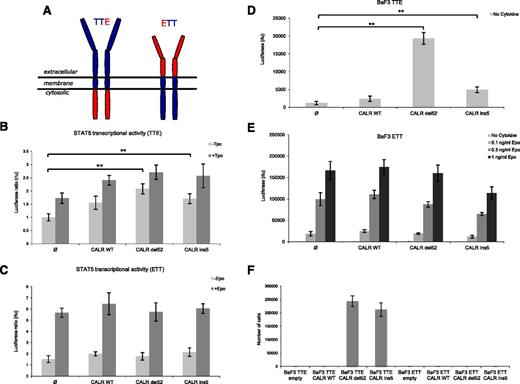

The extracellular domain and the N-glycosylation sites of TpoR are indispensable for TpoR activation by CALR mutants

To uncover the mechanism of TpoR activation by CALR mutants, we generated chimeric constructs in which the extracellular and cytosolic domains of TpoR and EpoR were reciprocally fused together (Figure 3A). Only the chimeric receptor that contained the extracellular domain of TpoR (TTE) supported constitutive STAT5 activation by both CALR mutants in transient transfection luciferase assays (Figure 3B-C). In addition, the TTE receptor was also able to support short- and long-term cell proliferation of Ba/F3 cells (Figure 3D,F), whereas ETT did not (Figure 3E-F). Although ETT did not support constitutive growth induced by CALR mutants, this receptor still responded to Epo (Figure 3E). Thus, the extracellular domain of TpoR is absolutely required for activation by CALR mutants.

The extracellular domain of TpoR, but not of EpoR, is indispensable for CALR mutants activity. (A) Schematic representation of engineered chimeric receptors. On the left, chimeric receptor TTE is composed of the extracellular and transmembrane domains of TpoR (in blue) fused to the cytosolic domain of EpoR (in red). On the right, chimeric receptor ETT is composed by the extracellular domain of EpoR (in red) fused to the transmembrane and cytosolic domains of TpoR (in blue). STAT5 transcriptional activity was measured by luciferase assay in γ2A cells transiently transfected with JAK2 and CALR wild-type or mutants in the presence of the chimeric receptor TTE (B) or ETT (C). Only the chimeric receptor presenting the extracellular domain of TpoR (TTE) is able to support constitutive activity induced by CALR mutants. Ba/F3 cells stably transduced with CALR constructs together with TTE (D) or ETT (E) were cultured for 3 days without cytokine to measure short-term autonomous growth using CellTiter-Glo technology. ETT cells were also tested for response to Epo, as positive control. (F) Long-term proliferation (day 10) of Ba/F3 expressing the indicated chimeric receptors and CALR variants. Values shown represent the average of 3 pooled independent experiments, each performed with 3 biological replicates ± SEM. Statistical analysis (jmp pro11) was performed by the nonparametric multiple comparisons Steel test with a control group; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

The extracellular domain of TpoR, but not of EpoR, is indispensable for CALR mutants activity. (A) Schematic representation of engineered chimeric receptors. On the left, chimeric receptor TTE is composed of the extracellular and transmembrane domains of TpoR (in blue) fused to the cytosolic domain of EpoR (in red). On the right, chimeric receptor ETT is composed by the extracellular domain of EpoR (in red) fused to the transmembrane and cytosolic domains of TpoR (in blue). STAT5 transcriptional activity was measured by luciferase assay in γ2A cells transiently transfected with JAK2 and CALR wild-type or mutants in the presence of the chimeric receptor TTE (B) or ETT (C). Only the chimeric receptor presenting the extracellular domain of TpoR (TTE) is able to support constitutive activity induced by CALR mutants. Ba/F3 cells stably transduced with CALR constructs together with TTE (D) or ETT (E) were cultured for 3 days without cytokine to measure short-term autonomous growth using CellTiter-Glo technology. ETT cells were also tested for response to Epo, as positive control. (F) Long-term proliferation (day 10) of Ba/F3 expressing the indicated chimeric receptors and CALR variants. Values shown represent the average of 3 pooled independent experiments, each performed with 3 biological replicates ± SEM. Statistical analysis (jmp pro11) was performed by the nonparametric multiple comparisons Steel test with a control group; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

The TpoR extracellular domain is composed of 4 subdomains (D1, D2, D3, and D4) (Figure 4A). We generated constructs expressing TpoR with only D1D2 (TpoR D1D2) or D3D4 (TpoR D3D4). Only the more membrane-distal region of TpoR (TpoR D1D2) supported constitutive activation by CALR mutants (Figure 4B-C).

The membrane-distal part of extracellular domain of TpoR (D1D2) and its associated N-glycosylation sites control CALR mutant activity. (A) Schematic representation of TpoR with its extracellular subdomains and the N-glycosylation sites that have been mutated into Q. The more distal subdomains of extracellular domain of TpoR, namely D1D2, contain 2 N-glycosylated sites annotated N1 (N117) and N2 (N178). The proximal subdomains D3D4 contain two N-glycosylated sites annotated N3 (N298) and N4 (N358). STAT5 transcriptional activity was assessed by luciferase assay in γ2A cells transiently expressing STAT5, JAK2, CALR wild-type, or mutants together with the following TpoR mutants: TpoR D1D2 (B), TpoR D3D4 (C), TpoR N1234tQ (D), TpoR N123tQ (E), TpoR N124tQ (F), TpoR N134tQ (G), TpoR N234tQ (H), and TpoR N12tQ (I). Mutant TpoR missing D1D2, rather than D3D4, is unable to support CALR mutant activity (B). Values shown represent the average of 3 pooled independent experiments, each performed with 3 biological replicates ± SEM. Statistical analysis (jmp pro11) was performed by the nonparametric multiple comparisons Steel test with a control group; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

The membrane-distal part of extracellular domain of TpoR (D1D2) and its associated N-glycosylation sites control CALR mutant activity. (A) Schematic representation of TpoR with its extracellular subdomains and the N-glycosylation sites that have been mutated into Q. The more distal subdomains of extracellular domain of TpoR, namely D1D2, contain 2 N-glycosylated sites annotated N1 (N117) and N2 (N178). The proximal subdomains D3D4 contain two N-glycosylated sites annotated N3 (N298) and N4 (N358). STAT5 transcriptional activity was assessed by luciferase assay in γ2A cells transiently expressing STAT5, JAK2, CALR wild-type, or mutants together with the following TpoR mutants: TpoR D1D2 (B), TpoR D3D4 (C), TpoR N1234tQ (D), TpoR N123tQ (E), TpoR N124tQ (F), TpoR N134tQ (G), TpoR N234tQ (H), and TpoR N12tQ (I). Mutant TpoR missing D1D2, rather than D3D4, is unable to support CALR mutant activity (B). Values shown represent the average of 3 pooled independent experiments, each performed with 3 biological replicates ± SEM. Statistical analysis (jmp pro11) was performed by the nonparametric multiple comparisons Steel test with a control group; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

We generated mutations in the extracellular domain of TpoR, where all the 4, 3, or 2 asparagine (Asn) residues were mutated to glutamine (Gln) (Figure 4A).13 The TpoR mutant devoid of all 4 N-glycosylation sites (TpoR N1234tQ) failed to support STAT5 activation in the presence of CALR mutants (Figure 4D). When individual Asn residues were restored in TpoR N1234tQ background, N117 (N1, the most N-terminal) residue was shown to be the most activating (Figure 4H), N298 and N358 were not activating, and N178 supported weak activation only by CALR ins5 (Figure 4E-G). Consistent with these results, a TpoR mutant lacking both N117 and N178 (N12tQ) is completely unable to support activation by both CALR mutants (Figure 4I). These results show that 2 Asn residues (N117 and N178) present in D1D2 are key players for TpoR activation by CALR mutants.

Next, we showed that the soluble extracellular domain of TpoR (stop codon at W491 upstream of the TpoR transmembrane domain) acts as a competitor to the full-length TpoR and blocks STAT5 activation by CALR mutants (Figure 5A). Importantly, a soluble extracellular domain where all the 4 Asn sites were mutated to Gln failed to exert inhibition (Figure 5B). However, CALR del52 mutant could still induce activation of the Tpo-binding–deficient TpoR mutant (D261A/L265A)36 (Figure 5C).

TpoR constitutive activation induced by CALR mutants is abrogated by the TpoR soluble form and requires the glycan binding site of CALR. (A) The soluble extracellular domain of TpoR acts as a competitive inhibitor of TpoR activation by the CALR mutants as shown by luciferase assay (STAT5 transcriptional activity). This inhibitory effect is lost when all the N-glycosylated asparagine residues of the soluble TpoR are mutated to glutamine (soluble TpoR-NtQ) (B). (C) The γ2A luciferase assay showed that the TpoR -D261A/L265A mutant, unable to bind Tpo, is activated by CALR del52. CALR del52 mutant unable to bind N-glycosylation modifications (CALR del52 D135L/Y109F) do not induce TpoR -dependent STAT5 activation (D). Values shown represent the average of 3 pooled independent experiments, each performed with 3 biological replicates ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by the nonparametric multiple comparisons Steel test with a control group; *P < .05, **P < .01.

TpoR constitutive activation induced by CALR mutants is abrogated by the TpoR soluble form and requires the glycan binding site of CALR. (A) The soluble extracellular domain of TpoR acts as a competitive inhibitor of TpoR activation by the CALR mutants as shown by luciferase assay (STAT5 transcriptional activity). This inhibitory effect is lost when all the N-glycosylated asparagine residues of the soluble TpoR are mutated to glutamine (soluble TpoR-NtQ) (B). (C) The γ2A luciferase assay showed that the TpoR -D261A/L265A mutant, unable to bind Tpo, is activated by CALR del52. CALR del52 mutant unable to bind N-glycosylation modifications (CALR del52 D135L/Y109F) do not induce TpoR -dependent STAT5 activation (D). Values shown represent the average of 3 pooled independent experiments, each performed with 3 biological replicates ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by the nonparametric multiple comparisons Steel test with a control group; *P < .05, **P < .01.

Altogether these results show that activation of TpoR by CALR mutants is dependent on TpoR N-glycosylation sites, but independent of the Tpo binding site.

The glycan binding site of CALR del52 mutant is required for TpoR activation

Because the N-glycosylation sites of TpoR are required for its activation by CALR mutants, we mutated the glycan binding site (Y109F/D135L)37 in CALR del 52 and could show that it does not activate TpoR in the absence of Tpo (Figure 5D). This supports the notion that the interaction between CALR mutant and TpoR requires CALR glycan binding site and the TpoR N-glycosylated sites for TpoR activation

CALR mutants show differential stability, localization, and TpoR maturation

To study CALR mutants in a cell background devoid of wild-type CALR, we used MEFs derived from calr−/− mice. calr−/− MEFs were transduced with viruses coding for TpoR and CALR wild-type or mutants and sorted for equivalent levels of GFP (for TpoR) and mCherry (for CALR). We assessed by confocal microscopy and western blotting the level of CALR expression and its stability. In contrast to wild-type CALR, the CALR mutants were unstable and this was accompanied with less CALR mutant protein expression (Figure 6A).

CALR mutants modify TpoR stability, maturation, and trafficking. (A) The expression of CALR in calr−/− MEFs transduced with retroviral constructs expressing TpoR and CALR wild-type or mutants was assessed by immunofluorescence (top panel) and by western blotting after cycloheximide (30 μg/mL) treatment (bottom panel). (B) Maturation state of TpoR in Ba/F3-TpoR cells in the presence of CALR wild-type or mutants was assessed by western blotting upon endoglycosidase H treatment or not. (B) Subcellular fractionation of CALR wild-type and mutant del52 proteins in calr−/− MEF TpoR cells. The distribution patterns of CALR and GRP78 were shown in the diagram and the blots. (C) Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy was performed in previously described calr−/− MEF cell lines and stained with anti-CALN (Calnexin), anti-CALR, and 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole. (D) Maturation state of TpoR in Ba/F3-TpoR cells in the presence of wild-type or mutant CALR was assessed by western blotting upon endoglycosidase H treatment or not. (E) Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitated N-terminal HA-tagged TpoR present on cell surface, in Ba/F3-TpoR cells expressing wild-type or mutant CALR. All data are normalized, C being the amount per volume of subfraction, and Ci the corresponding value in the pooled subfractions.

CALR mutants modify TpoR stability, maturation, and trafficking. (A) The expression of CALR in calr−/− MEFs transduced with retroviral constructs expressing TpoR and CALR wild-type or mutants was assessed by immunofluorescence (top panel) and by western blotting after cycloheximide (30 μg/mL) treatment (bottom panel). (B) Maturation state of TpoR in Ba/F3-TpoR cells in the presence of CALR wild-type or mutants was assessed by western blotting upon endoglycosidase H treatment or not. (B) Subcellular fractionation of CALR wild-type and mutant del52 proteins in calr−/− MEF TpoR cells. The distribution patterns of CALR and GRP78 were shown in the diagram and the blots. (C) Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy was performed in previously described calr−/− MEF cell lines and stained with anti-CALN (Calnexin), anti-CALR, and 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole. (D) Maturation state of TpoR in Ba/F3-TpoR cells in the presence of wild-type or mutant CALR was assessed by western blotting upon endoglycosidase H treatment or not. (E) Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitated N-terminal HA-tagged TpoR present on cell surface, in Ba/F3-TpoR cells expressing wild-type or mutant CALR. All data are normalized, C being the amount per volume of subfraction, and Ci the corresponding value in the pooled subfractions.

Also, we showed that CALR mutants induce tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of STAT3, indicating that wild-type CALR was not required for JAK-STAT activation by CALR mutants (supplemental Figure 3A).

To define the subcellular localization of wild-type and mutant CALR, postnuclear fractions were prepared by sedimentation of homogenates that were partitioned on sucrose density gradients (Figure 6B). The distribution of all markers tested as well as the density of each fraction are shown in supplemental Figure 4. The sedimentable ER-marker, GRP78, equilibrates with CALR wild-type (fraction #5), but not with CALR del52 (fraction #7), suggesting the dissociation of CALR mutant from ER (Figure 6B). High-resolution confocal microscopy was performed in calr−/− MEFs to avoid the interference of the endogenous CALR. CALR wild type and mutants exhibited different intracellular localizations, ER vs vesicle (ER to Golgi), respectively (Figure 6C and supplemental Figure 3B). Wild-type CALR colocalized with the ER marker calnexin (Figure 6C, left panel). This was not the case for del52 or ins5 mutants (Figure 6C, left panel), which colocalized with ERGIC53 (ER to Golgi intermediate compartment) (Figure 6C, right panel) and partially with or adjacent to GM130 (Golgi marker) (supplemental Figure 3B).

We observed maturation defects of TpoR in the Ba/F3-TpoR cells expressing CALR mutants by western blotting, with the majority of TpoR remaining EndoH-sensitive (immature, high mannose form). In contrast, the CALR wild-type promotes EndoH-resistant mature form of TpoR (Figure 6D). Surface immunoprecipitation of TpoR in Ba/F3 TpoR–expressing cells showed that CALR mutants are associated only with the immature form of TpoR (Figure 6E).

Spontaneous megakaryocytic progenitor growth in CALR-mutated ET patients requires TpoR and JAK2

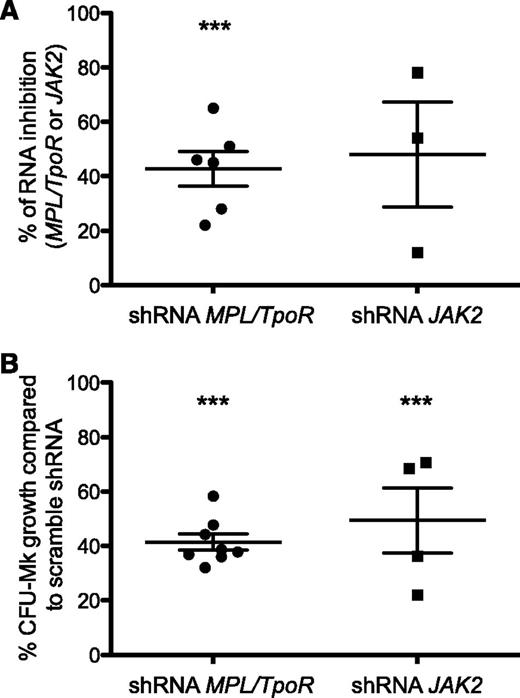

To confirm the involvement of the TpoR/JAK2 axis in the human disease, we performed in vitro studies using primary cells from CALR-mutated ET patients carrying either CALR ins5 or del52 mutations. As previously reported, we detected spontaneous (Tpo-independent) growth of megakaryocyte progenitors in such patients.38 CD34+ cells were transduced with lentiviruses expressing either short hairpin RNAs targeting TpoR/MPL or JAK2 or a scrambled sequence, and GFP as a reporter marker. Downregulation of TpoR/MPL or of JAK2 gene expression (Figure 7A) led to a significant inhibition of Tpo-independent colonies (∼50% reduction) associated in both types of CALR mutants (Figure 7B). Our data thus confirm that TpoR and JAK2 are absolutely required for the phenotype induced by CALR mutants in primary megakaryocyte progenitors from patients.

TpoR and JAK2 are required in CALR mutant–induced spontaneous growth of megakaryocytic progenitors in patients. CD34+ cells from patients carrying CALRdel52 or CALRins5 mutations were purified. (A) The percentages of inhibition of MPL/TpoR and JAK2 mRNA expression level by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction in CD34+ progenitors transduced with lentivirus expressing either sort hairpin RNAs (shRNA) targeting MPL/TpoR or JAK2, sorted on GFP, and cultured for 2 additional days. (B) The percentages of Tpo-dependent or -independent growth of megakaryocyte colonies derived from CFU-Mk (colony-forming unit megakaryocyte) in the presence of shRNA directed against MPL/TpoR or JAK2 compared with scramble sequence. Results are means ± SEM. Student t test: ***P < .0001.

TpoR and JAK2 are required in CALR mutant–induced spontaneous growth of megakaryocytic progenitors in patients. CD34+ cells from patients carrying CALRdel52 or CALRins5 mutations were purified. (A) The percentages of inhibition of MPL/TpoR and JAK2 mRNA expression level by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction in CD34+ progenitors transduced with lentivirus expressing either sort hairpin RNAs (shRNA) targeting MPL/TpoR or JAK2, sorted on GFP, and cultured for 2 additional days. (B) The percentages of Tpo-dependent or -independent growth of megakaryocyte colonies derived from CFU-Mk (colony-forming unit megakaryocyte) in the presence of shRNA directed against MPL/TpoR or JAK2 compared with scramble sequence. Results are means ± SEM. Student t test: ***P < .0001.

Discussion

This study uncovers a novel signaling mechanism in which a cytokine receptor is activated by a mutant chaperone protein leading to a phenotype linked to the lineage-restricted TpoR. We demonstrate that the 2 most common MPN-associated CALR mutants induce constitutive, ligand-independent activation of TpoR, in several systems and with different read-outs. The interaction between CALR mutants and TpoR directly leads to close dimerization of JAK2 kinase domain and its activation. These observations are in accordance with the results of bone marrow transplantation studies7 and companion study,8 where CALR mutants induced an ET phenotype, as well as with TpoR being essential for the megakaryocytic lineage, which is affected in ET and PMF patients. No other receptor tested could support activation of JAK-STAT pathway by CALR mutants, except GCSFR, where activation did not lead to long-term proliferation. It remains to be determined whether the weak GCSFR effects contribute to the phenotype or penetrance in the granulocytic lineage.

We show that the extracellular domain of TpoR is crucial for activation by CALR mutants. Further studies are required for determining the structural details of exactly how CALR mutants interact with the TpoR extracellular domain. TpoR N-linked sugars and CALR glycan-binding domain and the novel tail are required. Interestingly, unlike most of the cytokine receptors (including the closely related EpoR),39 TpoR has been shown to be able to signal from several dimeric interfaces.11,40 Because CALR can bind to N-glycosylated residues of several proteins,26 the specificity of TpoR activation cannot be attributed only to the interaction of CALR mutant to the receptor; rather the CALR mutant might stabilize one of the many active interfaces of TpoR,11,40 resulting in constitutive activation of the receptor. del52 and ins5 CALR mutants might stabilize 2 related, but not identical, active dimeric interfaces of TpoR, leading to differences in the phenotype, as suggested.41,42 This hypothesis would also explain why CALR mutants are not seen in other cancers driven by N-glycosylated mutated receptors (eg, EGFR, EPOR, KIT, FLT3D).6 Furthermore, binding of CALR mutant to TpoR and its activation do not require Tpo-binding.

Recently, the pathogenic effects of CALR mutants were shown to depend on the length of the stretch of negatively-charged residues that are retained before the frameshift.10 Type 1–like mutations resemble del52 CALR, where most of the stretches are deleted; this leads to high cytosolic calcium levels in megakaryocytes, presumably caused by the absence of calcium storage capacity in the ER.10 Another type 1 mutant, del61 CALR, reported in the MARIMO cell line,30 derived from an ET patient who was treated with Busulfan,43 also activates TpoR (supplemental Figure 2A-B). Mutants that preserve stretches of negatively-charged residues like ins5 do not show calcium defects.10 Further studies are required to determine whether the higher signaling we note in the case of del52 CALR is linked to its effects on calcium.

The interaction between TpoR and CALR is not only important in cell lines as Ba/F3 but also in the pathogenesis of the disease. We could show that Tpo-independent growth of megakaryocytic progenitors, which is a hallmark of CALR-mutated MPNs, is inhibited when TpoR or JAK2 are downregulated by shRNAs. This is in agreement with the observation that patients with CALR-mutated PMF may respond to ruxolitinib31 and with the results of the retroviral CALR mouse model7 described in the companion paper, where the thrombocytosis was dependent of the presence of TpoR.8

We observed a differential localization of CALR mutants compared with the wild-type. Our preliminary data indicate that activation already occurs intracellularly for the JAK-STAT pathway, but because we detect immature TpoR on the cell surface along with CALR mutant, it is possible that both intracellular and cell surface forms are required for transformation.

Contrary to JAK2V617F-transformed hematopoietic cells, there was no synergy between JAK2 and PI3-K inhibitors in inhibiting CALR mutant cells. Interestingly, a certain degree of synergy can be detected between JAK2 and MAP-kinase inhibitors. These differences might relate to the precise mechanisms of activation of TpoR by JAK2V617F vs CALR mutants. We suggest that combining JAK2 and PI3-K inhibitors might not be effective in CALR-mutated MPNs. Overall, our results are in agreement with CALR mutants activating the JAK-STAT pathway with signatures that overlap,44 but are not identical with those of JAK2V617F.45

In conclusion, this work demonstrates that CALR mutants specifically activate TpoR in a Tpo-independent manner and bring forward a new and unexpected oncogenic mechanism: cytokine receptor activation by a mutated chaperone.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nicolas Dauguet for expert cell sorting, Dr M. Shwe for the CALR mutant N-glycan deficient. cDNAs for IL-2Rbeta, IL-9R and STAT1 were kindly provided by Dr J.-C. Renauld, Ludwig Cancer Research, Brussels. Chimeric EpoR-TpoR constructs were from Dr J. Staerk.

This work is supported by Institut National du Cancer (PLBIO2015), Agence Nationale de la Recherche, Programme Jeunes Chercheuses et Jeunes Chercheurs (ANR-13-JVSV1-GERMPN-01), and Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM) (I.P.); a grant from la Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (équipe labellisée HR 2013, 2016) (H.R., I.P., W.V., C.M., M.E.-K.); the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, FRS-FNRS, Salus Sanguinis Foundation, the Action de Recherche Concertée project ARC10/15–027 of the Université catholique de Louvain, the Fondation contre le Cancer, the PAI Programs BCHM61B5, and Belgian Medical Genetics Initiative (S.N.C.); FRIA, Télévie, and FNRS-Aspirant fellowships (J.-P.D., I.C., G.V.); Cliniques universitaires St-Luc, Brussels (J.-P.D.); a Belspo postdoctoral fellowship (V.G.); and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF: project numbers F2812-B20 and F4702-B20) (H.N. and R.K.).

Authorship

Contribution: I.C., C.P., and M.E.-K. designed, performed, and interpreted experiments and corrected the paper; H.N. provided essential constructs, planned experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; R.-I.A., C.M., V.G., J.-P.D., and G.V. performed experiments and interpreted results; A.N., A.K., and M.L.C. designed, performed, and interpreted drug inhibition studies; P.J.C. gave key input, designed fractionation and confocal microscopy experiments, interpreted experiments, and wrote a section; H.R. designed and interpreted experiments; and I.P., W.V., R.K., and S.N.C. designed and interpreted experiments and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stefan N. Constantinescu, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research and de Duve Institute, Université catholique de Louvain, Avenue Hippocrate 74, UCL 75-4, B-1200 Brussels, Belgium; e-mail: stefan.constantinescu@bru.licr.org.

References

Author notes

I.C., C.P., and M.E.-K. contributed equally to this study.