Key Points

Calreticulin type I and type II mutants are drivers of the disease as they induce thrombocytosis in a retroviral mouse model.

Thrombopoietin receptor MPL is required for calreticulin mutants to induce an essential thrombocythemia phenotype in transplanted mice.

Abstract

Frameshift mutations in the calreticulin (CALR) gene are seen in about 30% of essential thrombocythemia and myelofibrosis patients. To address the contribution of the CALR mutants to the pathogenesis of myeloproliferative neoplasms, we engrafted lethally irradiated recipient mice with bone marrow cells transduced with retroviruses expressing these mutants. In contrast to wild-type CALR, CALRdel52 (type I) and, to a lesser extent, CALRins5 (type II) induced thrombocytosis due to a megakaryocyte (MK) hyperplasia. Disease was transplantable into secondary recipients. After 6 months, CALRdel52-, in contrast to rare CALRins5-, transduced mice developed a myelofibrosis associated with a splenomegaly and a marked osteosclerosis. Monitoring of virus-transduced populations indicated that CALRdel52 leads to expansion at earlier stages of hematopoiesis than CALRins5. However, both mutants still specifically amplified the MK lineage and platelet production. Moreover, a mutant deleted of the entire exon 9 (CALRdelex9) did not induce a disease, suggesting that the oncogenic property of CALR mutants was related to the new C-terminus peptide. To understand how the CALR mutants target the MK lineage, we used a cell-line model and demonstrated that the CALR mutants, but not CALRdelex9, specifically activate the thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor (MPL) to induce constitutive activation of Janus kinase 2 and signal transducer and activator of transcription 5/3/1. We confirmed in c-mpl– and tpo-deficient mice that expression of Mpl, but not of Tpo, was essential for the CALR mutants to induce thrombocytosis in vivo, although Tpo contributes to disease penetrance. Thus, CALR mutants are sufficient to induce thrombocytosis through MPL activation.

Introduction

Classical myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) include polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF).1 To date, recurrent mutations in 3 genes have been identified as phenotypic drivers.2 The mechanism of action of activating mutations in the JAK2 and the thrombopoietin receptor (MPL) genes has been extensively studied and their effect on the disease has been attributed to a constitutive activation of the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling axis. More recently, 2 groups reported new somatic mutations in the gene encoding calreticulin (CALR) in ∼30% of JAK2- and MPL-negative ET and PMF patients.2,3

CALR is a chaperone protein of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen that controls proper folding of neosynthesized glycoproteins and retains calcium in the ER.4,5 The CALR mutations occur exclusively in the last exon (exon 9) of the gene. They are insertions and/or deletions that result in a frameshift to a specific alternative reading frame, resulting in a novel C-terminal sequence in the mutants. CALRdel52 and CALRins5 are the 2 most prevalent mutations found in ET and PMF patients, with CALRdel52 being more frequent than CALRins5 in PMF.6 Here, using a retroviral mouse model, we demonstrate that both mutants induce a human ET-like disease with major differences in the severity of thrombocytosis, the evolution into fibrosis, and the level of clonal amplification. CALR mutants are drivers of the disease and are capable of constitutively activating the JAK/STAT signaling pathway through MPL. MPL is required to induce spontaneous megakaryocytic progenitor growth and thrombocytosis in mice.

Methods

Retroviruses

CALRdel52, CALRins5, wild-type CALR (CALRwt), and CALRdelex9 lacking the entire exon 9 were inserted into a pMSCV-IRES-GFP retroviral vector. Control was the empty virus. Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein pseudotyped viral particles were produced into 293EBNA cells.

Bone marrow transduction procedure

All procedures were approved by the Gustave Roussy Ethics Committee (protocol 2012_061). Bone marrow (BM) cells were collected from 2-month-old C57BL/6J mice (Janvier) 4 days after 5-fluorouracil injection (150 mg/kg), and lineage-negative (Lin−) cells were purified and transduced with the different retroviruses. Finally, 0.4 × 106 transduced cells per animal were IV injected into lethally irradiated (9.5 Gy for wild-type and 8 Gy for c-mpl and tpo knockout mice) recipient mice. For secondary transplantation, BM cells collected from 10-week-old primary recipients were injected (2 × 106 cells per animal) into irradiated mice.

Analysis of mouse blood and content in progenitor and precursor cells

Peripheral blood cells, BM, and spleen.

Platelet, red blood cell (RBC) and white blood cell (WBC) counts were determined using an automated counter (MS9; Schloessing Melet). BM cells were removed by flushing the femurs and tibias. Spleens were weighed and single-cell suspensions were prepared. Total hematopoietic cell number per mouse was calculated assuming that the cells in 2 femurs and tibias represent 25% of the total BM and from the total number of cells isolated from the spleen.

Flow cytometry.

LSR II and FACSCanto I (BD Biosciences) were used to determine the percentages of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive (GFP+) infected cells and cell content of BM and spleen. Lin− cells were negatively selected with allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD3, B220, Gr-1, Mac-1, and Ter-119 rat anti-mouse antibodies (Abs). For analysis of the Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) progenitor cell-enriched fraction, Lin− cells were stained with Abs against mouse Sca-1 (phycoerythrin-Cy7) and c-Kit (PerCP-Cy5.5). The Lin−Sca1+c-Kit+CD48−CD150+ (SLAM) hematopoietic stem cell (HSC)-enriched population was isolated with Pacific Blue anti-mouse CD48 and Brilliant Violet 510 anti-mouse CD150 Abs. All Abs were from eBioscience (Ozyme). BM and spleen precursor cells were also analyzed with fluorochrome-conjugated Abs directed against mouse CD41 and CD42 (megakaryocytic lineage), Ter-119 and CD71 (erythroid lineage), Mac-1 and Gr-1 (granulocytic lineages), B220 and CD3 (lymphoid lineages).

Progenitor analysis in semisolid cultures.

BM and spleen nucleated cells were plated in duplicate in methylcellulose MethoCult 32/34 (StemCell Technologies) in presence of cytokines (stem cell factor [SCF], interleukin-6 [IL-6], IL-3, thrombopoietin [TPO], erythropoietin) and erythroid (burst forming unit-erythroid) and granulomonocytic (colony forming unit [CFU]-granulocyte macrophage) progenitors were counted 7 days later. BM nucleated cells were plated in duplicate in serum-free fibrin clot assays with SCF, IL-6, and no or increasing doses of TPO to quantify megakaryocytic progenitor (CFU-megakaryocyte [MK])-derived colonies at day 7 by acetylcholinesterase staining.

Histology.

Tibia and spleen sections were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, decalcified, and paraffin embedded. Sections were stained with hematoxylin/eosin/safran for cytology and MKs were reliably identified with von Willebrand factor stain. Reticulin fibers were revealed by Gordon and Sweet silver staining

Viability and proliferation of Ba/F3 cell models

Ba/F3 cells were transduced to express human MPL (pMX-IRES-CD4), human EPOR (pMX-IRES-GFP), or the human G-CSFR (pMX-IRES-GFP) and the various human CALR (pMSCV with an IRES-GFP/mCherry) constructs. To determine long-term cytokine independence, Ba/F3 cells were plated at a density of 250 000 cells/mL, and total live cells were manually counted after 10 days of culture. The Premix WST-1 Cell Proliferation Assay System (Clontech) was used to measure dose-dependent cell proliferation to TPO.

Western blot analysis

Sorted GFP+Lin− spleen cells were analyzed by western blot to assess the relative expression levels of CALRdel52 and CALRins5. CALR mutants were detected using a monoclonal rabbit Ab directed against the novel C-terminal tail of the CALR mutants (A. Vannucchi, University of Florence, Florence, Italy). Signaling studies and protein expression levels were performed on Ba/F3 cell lines using polyclonal Abs against the phosphorylated forms of JAK2 (Tyr1007/1008), tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) (Tyr1054/1055), STAT1 (Tyr701), STAT3 (Tyr705), STAT5 (Tyr694), extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204), and AKT (Ser473) and against the pan proteins (Cell Signaling Technology; Ozyme). MPL was revealed with an Ab from Upstate (Millipore), and the whole CALR with an Ab from abcam. Monoclonal anti-β-Actin Ab was obtained from Sigma and was used to check the loading.

Results

CALRdel52 and CALRins5 induce thrombocytosis in mice

To study the in vivo effect of the CALR mutants in mice, Lin− BM cells transduced with retroviruses expressing human CALRdel52, CALRins5, CALRwt, CALRdelex9 (lacking the entire exon 9), or empty vector (Mock) were engrafted into lethally irradiated recipient mice. Results from 2 independent experiments were pooled.

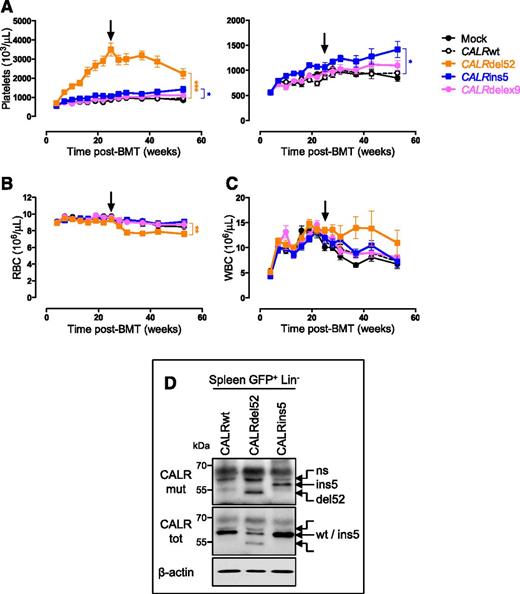

The CALR mutant-expressing mice rapidly developed thrombocytosis compared with CALRwt or Mock mice and at higher levels in the presence of CALRdel52 than in the presence of CALRins5 (Figure 1A-C). In contrast, WBC and RBC counts were not impacted until 6 months after BM transplantation (BMT). To verify that the differences in platelet levels between the 2 mutants were not due to differences in protein levels, GFP-positive (GFP+) Lin− cells sorted from spleen of 10-month-old mice were examined by western blot. Both mutated CALR proteins were equally expressed (Figure 1D). Finally, the disease was transplantable into secondary hosts with features identical to the primary recipients (supplemental Figure 1A-C, available on the Blood Web site), showing that it is a cell-intrinsic disorder. It is noteworthy that even if CALRdelex9 protein was less abundant than the CALR mutants (supplemental Figure 1D), CALRdelex9 mice, similarly to the 2 controls (CALRwt and Mock), did not develop a disease, suggesting that the novel C-terminal sequence, rather than the absence of the wild-type tail, plays a central role in the driver properties of the CALR mutants (Figure 1A-C).

CALR mutants induce an ET-like phenotype in vivo in mice. Primary CALRdel52 (n = 22), CALRins5 (n = 20), CALRdelex9 (n = 10), CALRwt (n = 22), and Mock (n = 10) recipient mice were analyzed every 3 weeks after bone marrow transplantation (BMT), over a 1-year period. Graphs show (A) platelets with a smaller scale on the right, (B) RBC and (C) WBC counts as mean ± SEM. Bonferroni multiple comparison test: *P < .05, **P < .001, ***P < .0001. Arrows indicate 6 months posttransplantation. (D) Spleen GFP+ Lin− cells were examined by western blot for CALR protein levels using an antibody specifically directed against the novel C-terminal tail of the mutants (CALRmut). An antibody directed against the whole CALR protein (CALRtot) was also used. β-actin serves as a loading control. Blots show representative results. ns, a nonspecific band; SEM, standard error of the mean.

CALR mutants induce an ET-like phenotype in vivo in mice. Primary CALRdel52 (n = 22), CALRins5 (n = 20), CALRdelex9 (n = 10), CALRwt (n = 22), and Mock (n = 10) recipient mice were analyzed every 3 weeks after bone marrow transplantation (BMT), over a 1-year period. Graphs show (A) platelets with a smaller scale on the right, (B) RBC and (C) WBC counts as mean ± SEM. Bonferroni multiple comparison test: *P < .05, **P < .001, ***P < .0001. Arrows indicate 6 months posttransplantation. (D) Spleen GFP+ Lin− cells were examined by western blot for CALR protein levels using an antibody specifically directed against the novel C-terminal tail of the mutants (CALRmut). An antibody directed against the whole CALR protein (CALRtot) was also used. β-actin serves as a loading control. Blots show representative results. ns, a nonspecific band; SEM, standard error of the mean.

CALRdel52 mice develop myelofibrosis

Platelet and RBC counts decreased in the CALRdel52 mice 6 months after transplantation (Figure 1A-B). This was associated with a time-dependent increase in spleen weight and decrease in BM nucleated cells (Figure 2A-B). After 10 months, histologic examination of CALRdel52 mice revealed expanding osteogenesis in BM with punctuations of newly formed bone (Figure 2C). Abundant clusters of MKs were seen in the BM, but also in the spleen, which was partially disorganized (Figure 2C). Silver staining showed thickening of the reticulin fiber network in both BM and spleen. Interestingly, a year postengraftment, slight spleen fibrosis was observed in 1 of 10 CALRins5 mice that were analyzed whereas all CALRdel52 mice had developed fibrosis within 6 months (supplemental Figure 1D).

BM and spleen features show evolution of the disease to myelofibrosis for all CALRdel52 mice and 1 CALRins5 mouse. (A) Spleen weight and (B) BM cellularity (n = 3-5), expressed as mean ± SEM. Student t test: *P < .05, **P < .001. (C) Hematoxylin-eosin-safran (HES), von Willebrand factor staining (vWF) and reticulin silver stain (RET) of 10-month-old mouse BM and spleen of CALRdel52 mice show clusters of MKs, osteosclerosis, and a progressive thickening of the reticulin network. Images were obtained using a DM2000 Leica microscope and a DFC300FX Leica camera with Leica Application Suite, v.2.5, OR1 acquisition software (×2.5 and ×25 magnifications).

BM and spleen features show evolution of the disease to myelofibrosis for all CALRdel52 mice and 1 CALRins5 mouse. (A) Spleen weight and (B) BM cellularity (n = 3-5), expressed as mean ± SEM. Student t test: *P < .05, **P < .001. (C) Hematoxylin-eosin-safran (HES), von Willebrand factor staining (vWF) and reticulin silver stain (RET) of 10-month-old mouse BM and spleen of CALRdel52 mice show clusters of MKs, osteosclerosis, and a progressive thickening of the reticulin network. Images were obtained using a DM2000 Leica microscope and a DFC300FX Leica camera with Leica Application Suite, v.2.5, OR1 acquisition software (×2.5 and ×25 magnifications).

CALRdel52 and CALRins5 mutations differentially impact the stem cell compartment, but both amplify the MK lineage

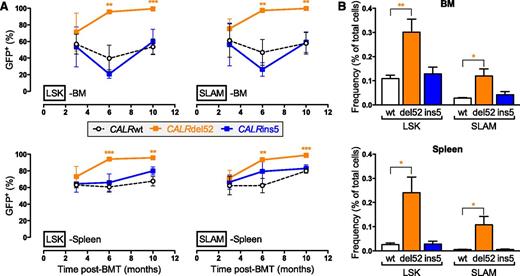

Based on the use of a bicistronic GFP-expression retroviral vector, we determined that around 50% of engrafted cells were retrovirally transduced. Virus-infected (GFP+) cells were analyzed in blood, BM, and spleen at different levels of differentiation and time points after transplantation. The percentages of GFP+ cells within the early hematopoietic progenitors and HSCs (LSK and SLAM populations, respectively) at 3 months postengraftment were similar to those found in the initial graft (Figure 3A) for all mice, except for CALRdel52 mice in which the percentage of GFP+ cells increased from ∼50% to ∼100% from 3 to 6 months. These results revealed that CALRdel52 expression, in contrast to CALRins5, provides an advantage to hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) that completely outcompete the nontransduced cells at 10 months after engraftment leading to WBCs of almost exclusively virus-infected origin (supplemental Figure 2A-B). Moreover, this clonal advantage leads to a significant increase in the frequency of LSKs and SLAMs in BM and spleen in CALRdel52 mice 10 months after engraftment (Figure 3B).

Different amplification of early hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in CALRdel52 and CALRins5 mice. (A) Evolution of the percentage of GFP+ cells in BM and spleen LSK and SLAM cell compartments (n = 3 to 5). (B) Frequency of BM and spleen LSK and SLAM cells of CALRwt, CALRdel52, or CALRins5 origin after 10 months transplantation (n = 5). Results are means ± SEM. Student t test: *P < .05, **P < .001, ***P < .0001.

Different amplification of early hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in CALRdel52 and CALRins5 mice. (A) Evolution of the percentage of GFP+ cells in BM and spleen LSK and SLAM cell compartments (n = 3 to 5). (B) Frequency of BM and spleen LSK and SLAM cells of CALRwt, CALRdel52, or CALRins5 origin after 10 months transplantation (n = 5). Results are means ± SEM. Student t test: *P < .05, **P < .001, ***P < .0001.

CALRdel52 and CALRins5 amplify the MK lineage

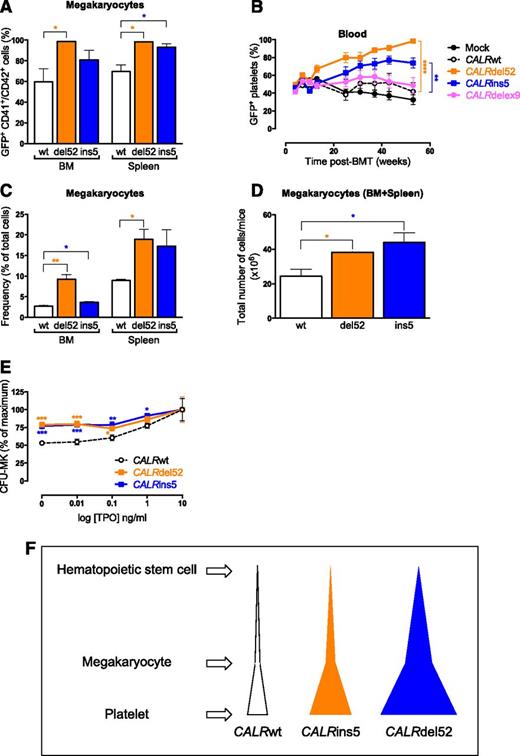

Dominance of both the CALRdel52 and the CALRins5 cells was revealed in the late stage of megakaryopoiesis, in BM and spleen MKs (Figure 4A), leading to an early rise in the percentage of GFP+ platelets in both mutant-expressing mice (Figure 4B). Thus, both CALRdel52 and CALRins5 provide a competitive advantage to the MK lineage. As expected, the frequency of MKs increased in the BM and spleen of both CALRdel52 and CALRins5 mice (Figure 4C). The cumulative numbers of MKs were significantly higher in CALRdel52 and CALRins5 mice than in CALRwt mice (Figure 4D) without significant differences in erythroblasts, granulocytic and lymphoid precursors (supplemental Figure 2C). We found that MK progenitors (CFU-MKs) expressing the CALR mutants displayed a hypersensitivity to TPO, maybe explaining this proliferative advantage of the MK lineage (Figure 4E). Taken together, 1 of the differences between the 2 CALR mutants resides in the level of initial cell amplification: HSC vs MK lineage for the CALRdel52 and CALRins5 mutations, respectively (Figure 4F).

Amplification of the megakaryocytic lineage in CALRdel52 and CALRins5 mice. (A) Percentage of GFP+ MKs (CD41+CD42+ cells) in BM and spleen in 10 months post-BMT mice (n = 3). (B) Evolution of the percentage of GFP+ platelets in blood (n = 20-22). Bonferroni multiple comparison test: **P < .001, ***P < .0001. (C) Frequency of BM and spleen MKs in CALRwt-, CALRdel52-, and CALRins5-transduced 10-month-old mice (n = 3). (D) Cumulative numbers in BM plus spleen of MKs from CALRwt-, CALRdel52-, and CALRins5-transduced 10-month-old mice (n = 3). (E) Percentages of BM megakaryocytic progenitor (CFU-MKs) colonies growing in the presence of SCF, IL-6, and increasing concentrations of TPO. Values were pooled for 3, 6, and 10 months post-BMT mice (n = 13-15). Results are means ± SEM. Student t test: *P < .05, **P < .001, ***P < .0001. (F) Schematic representation of the difference in clonal amplification between CALRdel52- and CALRins5-transduced mice. Both CALRdel52 and CALRins5 mutations lead to a specific amplification of MKs and platelets in transduced mice. CALRdel52 induces an earlier amplification of hematopoietic cells (HSC compartment) than the CALRins5 mutation (CFU-MK level) leading to an overall greater production of platelets than the CALRins5 mutation.

Amplification of the megakaryocytic lineage in CALRdel52 and CALRins5 mice. (A) Percentage of GFP+ MKs (CD41+CD42+ cells) in BM and spleen in 10 months post-BMT mice (n = 3). (B) Evolution of the percentage of GFP+ platelets in blood (n = 20-22). Bonferroni multiple comparison test: **P < .001, ***P < .0001. (C) Frequency of BM and spleen MKs in CALRwt-, CALRdel52-, and CALRins5-transduced 10-month-old mice (n = 3). (D) Cumulative numbers in BM plus spleen of MKs from CALRwt-, CALRdel52-, and CALRins5-transduced 10-month-old mice (n = 3). (E) Percentages of BM megakaryocytic progenitor (CFU-MKs) colonies growing in the presence of SCF, IL-6, and increasing concentrations of TPO. Values were pooled for 3, 6, and 10 months post-BMT mice (n = 13-15). Results are means ± SEM. Student t test: *P < .05, **P < .001, ***P < .0001. (F) Schematic representation of the difference in clonal amplification between CALRdel52- and CALRins5-transduced mice. Both CALRdel52 and CALRins5 mutations lead to a specific amplification of MKs and platelets in transduced mice. CALRdel52 induces an earlier amplification of hematopoietic cells (HSC compartment) than the CALRins5 mutation (CFU-MK level) leading to an overall greater production of platelets than the CALRins5 mutation.

CALR mutants induce MPL activation and JAK/STAT signaling

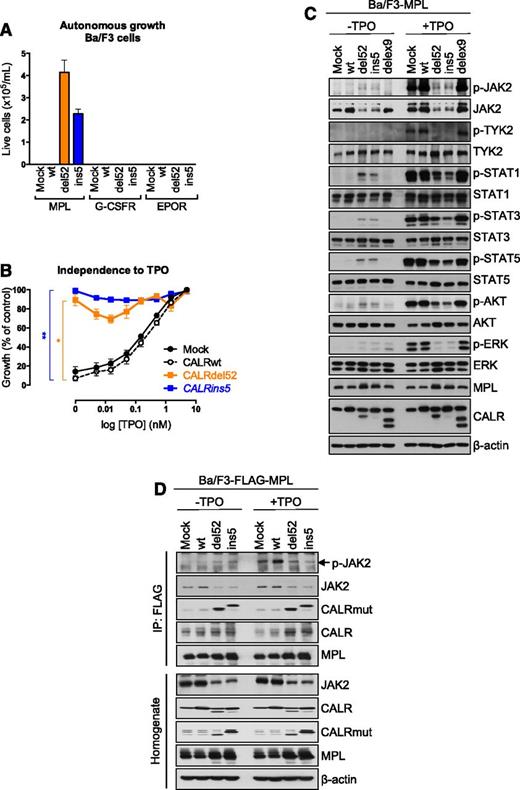

The development of thrombocytosis in mice, combined with the previous observation that expression of CALRdel52 induces a constitutive activation of the JAK/STAT signaling,7 could suggest that the oncogenic activity of CALR mutant is mediated via MPL, the key receptor of the MK lineage. Ba/F3 cells were transduced to express CALRwt, CALRdelex9, or CALR mutants. CALR mutants, in contrast to CALRwt and CALRdelex9, induced consistent cytokine-independent growth of Ba/F3 cells expressing MPL, but not of the cells that did not express MPL (data not shown). Interestingly, only MPL, but neither EPOR nor the G-CSFR maintained long-term cytokine-independent cell growth in the presence of both CALR mutants (Figure 5A). These results were confirmed by a cell proliferation assay in response to increasing doses of TPO showing that Ba/F3-MPL cells in presence of CALRdel52 or CALRins5 are nearly completely independent of TPO (Figure 5B), mimicking the TPO hypersensitivity of mouse CFU-MKs observed previously (Figure 4E). In Ba/F3-MPL cells, we confirmed that expression of the CALR mutants induced a strong constitutive phosphorylation of STAT5/3/1 and an apparent weaker phosphorylation of JAK2 due to the decreased level of the protein (Figure 5C). In contrast, ERK and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3-K)/AKT pathways were only weakly activated. TPO addition provided only a minor increase in the phosphorylation of these molecules compared with controls. Although JAK2, CALRwt and CALR mutants were found to coimmunoprecipitate with MPL in Ba/F3-MPL cells, the active phosphorylated form of JAK2 only bound to the MPL-containing complex in cells expressing the CALR mutants (Figure 5D). These data demonstrate that the CALR mutants interact with MPL and activate JAK2 and the STATs independently of TPO.

CALR mutants induce a specific activation of MPL. (A) Ba/F3 cells transduced to express Mock or CALRwt or mutants and MPL, EPOR, or G-CSFR were cultured for 10 days in the absence of any cytokine and their number was measured by a cell counter (Beckman Coulter). (B) Proliferation was assessed 72 hours after culturing Ba/F3-MPL cells expressing Mock, CALRwt, or the CALR mutants in the absence or in the presence of increasing doses of TPO (0.005, 0.015, 0.05, 0.15, 0.5, 1.5, and 5 ng/mL) by WST-1 proliferation assay. Dose-response curves are means (in percentage of viability of the maximum growth value) ± SEM (n = 3 in triplicate). Bonferroni multiple comparison test: *P < .05, **P < .001. (C) Ba/F3-MPL cells expressing different CALR constructs was examined by western blotting for the presence and phosphorylation status of various signaling molecules. Cells were serum- and cytokine-starved for 5 hours prior to 10 minutes stimulation with 10 ng/mL TPO. Expression of β-actin was used as loading control. (D) Immunoprecipitation (IP) using anti-FLAG antibody from lysates of Ba/F3 cells expressing a FLAG-tagged MPL and transduced with respective CALR constructs followed with western blotting.

CALR mutants induce a specific activation of MPL. (A) Ba/F3 cells transduced to express Mock or CALRwt or mutants and MPL, EPOR, or G-CSFR were cultured for 10 days in the absence of any cytokine and their number was measured by a cell counter (Beckman Coulter). (B) Proliferation was assessed 72 hours after culturing Ba/F3-MPL cells expressing Mock, CALRwt, or the CALR mutants in the absence or in the presence of increasing doses of TPO (0.005, 0.015, 0.05, 0.15, 0.5, 1.5, and 5 ng/mL) by WST-1 proliferation assay. Dose-response curves are means (in percentage of viability of the maximum growth value) ± SEM (n = 3 in triplicate). Bonferroni multiple comparison test: *P < .05, **P < .001. (C) Ba/F3-MPL cells expressing different CALR constructs was examined by western blotting for the presence and phosphorylation status of various signaling molecules. Cells were serum- and cytokine-starved for 5 hours prior to 10 minutes stimulation with 10 ng/mL TPO. Expression of β-actin was used as loading control. (D) Immunoprecipitation (IP) using anti-FLAG antibody from lysates of Ba/F3 cells expressing a FLAG-tagged MPL and transduced with respective CALR constructs followed with western blotting.

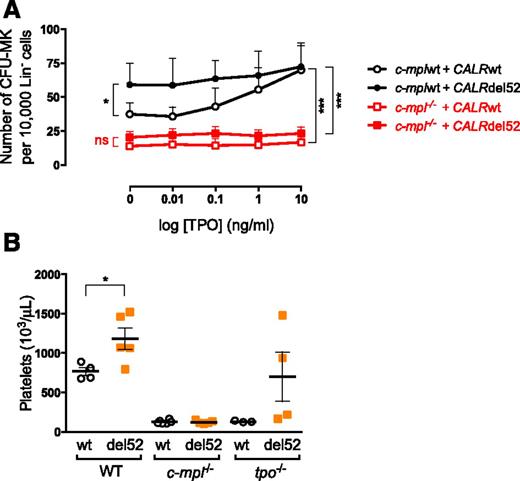

The TPO receptor MPL is crucial in CALRdel52-induced thrombocytosis in mice

We verified that the CALR mutant-induced phenotype in mice was dependent on the presence of MPL. We found that CFU-MKs from wild-type C57B/L6 mice expressing the CALR mutants exhibited an increased growth in the absence of TPO in comparison with those expressing CALRwt (Figures 4E and 6A). This was not the case when CALRdel52 was expressed in Lin− progenitors from c-mpl knockout (c-mpl−/−) mice (Figure 6A), indicating that amplification of CFU-MKs by CALR mutants requires Mpl.

Mpl is required in CALR mutant-induced spontaneous growth of megakaryocytic progenitor and thrombocytosis in mice. (A) Lin− cells were purified from C57BL/6 (n = 3) and c-mpl−/− mice (n = 3) and transduced with retrovirus expressing CALRwt or CALRdel52. GFP+ Lin− cells were sorted 2 days later and plated in a fibrin clot assay in presence of SCF, IL-6, and increasing doses of TPO. Curves are means of CFU-MK frequency ± SEM. Bonferroni multiple comparison test: *P < .05, **P < .001, ***P < .0001. (B) Lin− cells purified from C57BL/6 and c-mpl−/− mice were transduced to express CALRwt and CALRdel52 and engrafted in wild-type (n = 4-5), c-mpl−/− (n = 5-6), and tpo−/− (n = 3-4) mice. Platelet counts were determined 7 weeks after engraftment. Results show individuals and the means ± SEM. Student t test: *P < .05. ns, nonsignificant.

Mpl is required in CALR mutant-induced spontaneous growth of megakaryocytic progenitor and thrombocytosis in mice. (A) Lin− cells were purified from C57BL/6 (n = 3) and c-mpl−/− mice (n = 3) and transduced with retrovirus expressing CALRwt or CALRdel52. GFP+ Lin− cells were sorted 2 days later and plated in a fibrin clot assay in presence of SCF, IL-6, and increasing doses of TPO. Curves are means of CFU-MK frequency ± SEM. Bonferroni multiple comparison test: *P < .05, **P < .001, ***P < .0001. (B) Lin− cells purified from C57BL/6 and c-mpl−/− mice were transduced to express CALRwt and CALRdel52 and engrafted in wild-type (n = 4-5), c-mpl−/− (n = 5-6), and tpo−/− (n = 3-4) mice. Platelet counts were determined 7 weeks after engraftment. Results show individuals and the means ± SEM. Student t test: *P < .05. ns, nonsignificant.

Moreover, to confirm the involvement of MPL and of its ligand TPO in vivo, we transplanted lethally irradiated c-mpl−/− mice with Mpl-deficient Lin− cells transduced to express CALRwt or CALRdel52 (∼60% GFP+ cells). Similarly, CALRwt- and CALRdel52-transduced wild-type Lin− cells were engrafted in tpo−/− mice and wild-type mice as controls (∼60% GFP+ cells). Seven weeks post-BMT, percentages of GFP in blood were still around 60%, and the absence of Mpl led to the inhibition of CALRdel52-induced thrombocytosis (Figure 6B). Interestingly, in a Tpo-deficient setting, mice developed a phenotype, but which was less penetrant than the wild-type mice. These results suggest that TPO is not absolutely required for the induction of an ET phenotype by CALR mutants in vivo.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that ectopic expression of the 2 most common MPN-associated CALR mutants in HSCs and progenitor cells is sufficient to induce a MPN phenotype mimicking human ET in mice and that constitutive activation of MPL and hypersensitivity to TPO may explain this phenotype. Moreover, CALRdel52 mice developed a “post-ET” myelofibrosis with associated decrease in platelet count, anemia, splenomegaly, BM hypocellularity and marked osteosclerosis. TPO-high–expressing mice8 and MPLW515L retrovirally transduced mice9 also recapitulate a similar disease with thrombocytosis progressing to myelofibrosis. This study contrasts with the various jak2V617F mouse models that progress into myelofibrosis via a PV-like stage.10-14 These differences may be related to the specificity of MPL activation by the CALR mutants in comparison with JAK2V617F.

The diseases generated by the 2 types of CALR mutations differ with respect to the levels of thrombocytosis and kinetics and frequency of myelofibrosis transformation. This suggests that, in mice, the ability of CALRins5 to promote pathologic MK proliferation is comparatively milder than that of the CALRdel52 mutant. Moreover, CALRdel52 mice developed fibrosis with a much higher frequency than CALRins5 mice in agreement with observations made in patients where CALRdel52 is more frequent in myelofibrosis than CALRin5 (70% compared with 13%).6,15 Moreover, in patients the frequency of post-ET myelofibrosis is much higher for CALRdel52 (around 12% at 10 years) than for CALRins5 or even for JAK2V617F ETs.16 This also suggests that CALRins5 mutation might be of low penetrance for myelofibrosis progression.

Although both CALR mutations are acquired by HSCs, the phenotypic differences may be explained by the level of initial clonal amplification: HSC and MK for CALRdel52 andCALRins5 mutations, respectively. CALRdel52 mutation seems to play an important role in HSC clonal dominance whereas the role of JAK2V617F in HSCs remains controversial.14,17 This is illustrated by the low variant allele frequency in HSCs for JAK2V617F in comparison with CALR mutants in ET. Further study will be necessary to understand these differences in the mechanism of clonal amplification induced by the 2 CALR mutants.

Interestingly, the CALRdelex9 mice, expressing a CALR lacking the entire exon 9, do not develop thrombocytosis, suggesting that, besides differences in protein expression levels, the presence of the new mutant protein tail, rather than the absence of the wild-type C-terminal sequence, seems determinant for the phenotype. The main biochemical difference between CALRdel52 and CALRins5 mutants concerns the number of the negatively charged amino acids lost in comparison with CALRwt. Thus, the length and/or the ratio of the positive to negative charges on the C-terminal tail of the CALR mutant might play an important role in modulating its oncogenic strength.

Using a cell-line model, we demonstrate that CALR mutants specifically activate the MPL/JAK2 axis to the same extent. The specificity of activation of MPL among several other cytokine receptors tested was reported in details by the companion article.18 In addition, the phenotypic difference observed between CALRdel52 and CALRins5 mice is thus probably not directly linked to the activation of the JAK/STAT pathway but rather to differences in calcium signaling, as suggested by a recent study.16 However, using a genetic approach we could demonstrate, as observed for the activation of JAK2/STAT in the Ba/F3 cell line, that MPL was indispensable for the induction of thrombocytosis by CALRdel52. Indeed, in the absence of Mpl, the animals remain thrombocytopenic. In contrast, after Tpo ablation, the animals could develop a thrombocytosis but with an important variability suggesting that TPO may play a role in the penetrance of the disease. This result further underscores the great similarities in the mechanism of thrombocytosis and disease induction between JAK2V617F and CALR mutants. In both cases, MPL but not TPO is indispensable, TPO only increasing the disease phenotype.19 Moreover, in the companion article, the requirement of MPL and of JAK2 in the TPO-independent growth of primary megakaryocyte progenitors from human patients was confirmed using specific short hairpin RNAs.18

Elucidating the mechanism of action of CALR mutants has profound implications for the therapy of CALR-positive patients. Our results predict that the JAK2 inhibitors currently used in clinical trials could be effective in CALR-positive patients, as already observed in 2 patients with PMF.20

In addition, we could show in cell lines that CALR mutants only slightly activate the PI3-K pathway. These data have important implications for HSCs where constitutive activation of the PI3-K pathway by pten knockout has been shown to reduce self-renewal capacities,21 suggesting that the stem cells with CALR mutation would achieve clonal dominance much faster than those with JAK2 mutations. This could be one of the mechanisms explaining the higher CALR mutant allelic burden compared with that of JAK2V617F in ET patients as underscored above.22

Moreover, we show an association between CALRwt or CALR mutants and JAK2 and MPL in Ba/F3-MPL cells whereas the constitutively active phosphorylated form of JAK2 was only detected in presence of the CALR mutants. A study shows that the interaction between CALR and MPL is mediated via the N-glycosylation of asparagine residues in the extracellular domain of MPL and suggests that it might stabilize an intermediate active conformation of MPL.18 Further biochemical studies will be important to determine how CALR mutants can specifically activate MPL and what mechanisms are involved in the differences between CALRdel52 and CALRins5. Nevertheless, these phenotypic differences do not seem to be entirely explained by the level of activation of the JAK2/MPL axis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr A. M. Vannucchi (University of Florence, Florence, Italy) for providing the CALR mutant-specific rabbit polyclonal Ab; Dr F. Porteu, G. Warnier, and G. Gaudray for help with c-mpl knockout mice; and P. Rameau for flow cytometry and cell sorting. The authors also thank C. Legrand, D. Muller, and C. Fedronie for technical mouse support, O. Bawa for histology, and the staff of the animal facilities of Gustave Roussy directed by P. Gonin.

This work was supported by grants from Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (“Equipe labellisée 2013” [H.R., W.V., C.M., M.E.-K.]), Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (projet libre 2012 [I.P.]), Agence Nationale de la Recherche (thrombocytose 2011 [W.V.]), Agence Nationale de la Recherche, programme Jeunes Chercheuses et Jeunes Chercheurs (ANR-13-JVSV1-GERMPN-01 [I.P.]), Institut National du Cancer (PLBIO-2014 [J.-L.V.] and PLBIO2015 [I.P.]), MPN Research Foundation (J.-L.V.), and INSERM. C.M. was funded by a postdoctoral fellowship from ANR-13-JVSV1-GERMPN-01. Laboratory of Excellence Globule Rouge-Excellence (I.P., W.V.) is funded by the program “Investissements d’avenir”. S.N.C. is the recipient, from Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique-Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS), Salus Sanguinis, Fondation contre le cancer, Project Action de Recherche Concertée, of the Université catholique de Louvain ARC10/15-027 and the Pôle d'attraction inter-universitaire program Belgian Medical Genetics Initiative. C.P. is the recipient of FNRS Chargé de Recherche funding. The Austrian Science Fund Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung provided grant support to R.K. and H.N. (F4702-B20 and F2812-B20).

Authorship

Contribution: S.N.C., I.P., and W.V. conceived and designed the study, interpreted the data, and wrote the paper; C.M. designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data, prepared the figures, and wrote the paper; C.P., H.N. and M.E.-K. designed and performed experiments and analyzed the data; I.C. contributed to the c-mpl−/− mouse and cell-line studies; M.T. gave input in histopathological analysis; J.-L.V. and H.R. designed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; and R.K. analyzed the data and provided essential reagents.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: William Vainchenker, INSERM UMR1170, Université Paris-Saclay, Gustave Roussy, 114 rue Edouard Vaillant, 94805 Villejuif, France; e-mail: william.vainchenker@gustaveroussy.fr.

References

Author notes

I.P. and W.V. contributed equally.