Key Points

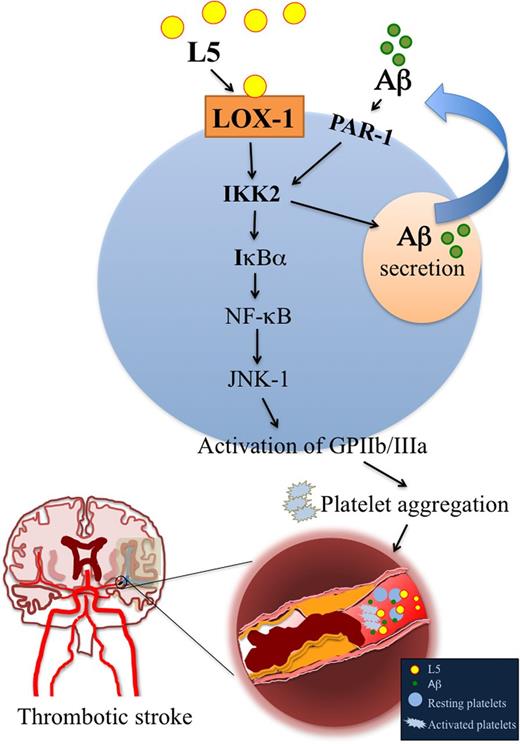

L5 is elevated in ischemic stroke patients, and its receptor, LOX-1, plays a critical role in increasing stroke size.

L5 induces platelet secretion of Aβ to potentiate platelet activation and aggregation via LOX-1 and IKK2.

Abstract

L5, the most electronegative and atherogenic subfraction of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), induces platelet activation. We hypothesized that plasma L5 levels are increased in acute ischemic stroke patients and examined whether lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1 (LOX-1), the receptor for L5 on endothelial cells and platelets, plays a critical role in stroke. Because amyloid β (Aβ) stimulates platelet aggregation, we studied whether L5 and Aβ function synergistically to induce prothrombotic pathways leading to stroke. Levels of plasma L5, serum Aβ, and platelet LOX-1 expression were significantly higher in acute ischemic stroke patients than in controls without metabolic syndrome (P < .01). In mice subjected to focal cerebral ischemia, L5 treatment resulted in larger infarction volumes than did phosphate-buffered saline treatment. Deficiency or neutralizing of LOX-1 reduced infarct volume up to threefold after focal cerebral ischemia in mice, illustrating the importance of LOX-1 in stroke injury. In human platelets, L5 but not L1 (the least electronegative LDL subfraction) induced Aβ release via IκB kinase 2 (IKK2). Furthermore, L5+Aβ synergistically induced glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor activation; phosphorylation of IKK2, IκBα, p65, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1; and platelet aggregation. These effects were blocked by inhibiting IKK2, LOX-1, or nuclear factor–κB (NF-κB). Injecting L5+Aβ shortened tail-bleeding time by 50% (n = 12; P < .05 vs L1-injected mice), which was prevented by the IKK2 inhibitor. Our findings suggest that, through LOX-1, atherogenic L5 potentiates Aβ-mediated platelet activation, platelet aggregation, and hemostasis via IKK2/NF-κB signaling. L5 elevation may be a risk factor for cerebral atherothrombosis, and downregulating LOX-1 and inhibiting IKK2 may be novel antithrombotic strategies.

Introduction

Stroke is a devastating disorder that disables or kills several million people each year.1-3 Cerebrovascular diseases, such as atherosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy, are well-established risk factors for ischemic stroke.4,5 Although platelets are essential for primary hemostasis and repair of the endothelium, they also play a critical role in the development of acute coronary syndromes and thromboembolic strokes.6,7 Platelets are involved in the process of forming and extending atherosclerotic plaques7,8 and are a source of inflammatory mediators, which may be an important cause of atherothrombosis.2,8 Activated platelets release amyloid β (Aβ) peptide,9-11 which accumulates in cerebral microvessels in an age-dependent manner,12 stimulates platelet aggregation,9 and is known to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of atherothrombosis11 and cerebral amyloid angiopathy.13 Thus, Aβ may play an important role in the mechanisms that lead to stroke.11,14

L5 is the most electronegative subfraction of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and is isolated by using fast-protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) with anion-exchange columns. L5 is the only LDL subfraction that has potent atherogenic properties in vivo and in vitro.15,16 The complex of L5 and its receptor, lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1 (LOX-1),17 may play a critical role in atherogenesis.18 In a rat middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model, LOX-1 expression was increased at a transient ischemic core site.19 Evidence suggests that LOX-1 expression induces atherosclerosis in the brain and is the precipitating cause of ischemic stroke.19 Importantly, plasma L5 levels are elevated in patients with risk factors for stroke, including type 2 diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and smoking.15,20 Recently, we showed that plasma L5 levels are higher in patients with ST–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) than in control subjects, and L5 from STEMI patients can enhance adenosine 5'-diphosphate–mediated platelet aggregation in vitro.13 In addition, L5 reduces the viability of cultured vascular endothelial cells (ECs)15,20,21 and causes EC dysfunction by increasing the procoagulant activity of ECs and EC-platelet interactions to induce platelet activation.16,22 Together, these findings suggest that L5 may play an important role in ischemic stroke.

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is a key regulator of inflammation, platelet aggregation, and atherogenesis.23 IκB kinase 2 (IKK2) is required for NF-κB activation.24 The IKK complex contains 2 enzymatic subunits, IKK1 (also known as IKKα) and IKK2 (also known as IKKβ), which have partially overlapping substrate specificity.25 Although data suggest a nongenomic role for IKK in platelets, the mechanisms are not fully understood.

In this study, we hypothesized that levels of circulating atherogenic L5 are increased in patients with acute ischemic stroke and that LOX-1 plays a critical role in stroke injury. Moreover, we hypothesized that L5 and Aβ synergistically induce prothrombotic pathways that lead to ischemic stroke. Our mechanistic findings suggest that L5 and Aβ enhance the occurrence and progression of thrombotic events via LOX-1 and IKK2.

Methods

Study subjects

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of China Medical University (CMU) and CMU Hospital in Taiwan. Study participants gave informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. For patients suffering from a recent stroke who were physically or mentally incapable of giving consent, informed consent was obtained from a legally authorized representative (supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site). We enrolled 25 patients with acute ischemic stroke; the control group comprised 35 healthy subjects without metabolic syndrome (see supplemental Methods). For acute ischemic stroke patients, blood samples were collected within 24 hours after the onset of stroke. All lipid parameters were measured according to standard operating procedures.

Isolation and quantification of L5

L5 was separated from total LDL by using FPLC with anion-exchange columns, as previously described (see supplemental Methods).15,26 L5% represents the percentage of L5 (milligrams per deciliter) divided by total LDL (milligrams per milliliter). For the following experiments, the L5 samples were pooled from the 25 patients with ischemic stroke.

Agarose gel electrophoresis

The electrophoretic mobility of LDL samples (2.5 μg in 9 μL) was analyzed by using gel electrophoresis in 0.7% agarose (90 mM Tris and 90 mM boric acid, pH 8.2) at 100 V for 1.4 hours, as previously described.15

Isolation of Aβ by using immunoprecipitation

An aliquot of monoclonal antibody against Aβ (D54D2; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) was added to 50 μL of magnetic Dynabeads (Qbeads-Protein G; MagQu, Taipei, Taiwan) and incubated overnight at 4°C on a rocking platform. Serum or the supernatant of active platelets was incubated with the antibody-coated beads, and the beads were pelleted and washed (see supplemental Methods). The extracted Aβ peptides were eluted by adding 20 μL of elution buffer (0.1 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.0) to the beads. The beads were pelleted by using a magnetic particle concentrator, and the supernatant containing the Aβ peptides was collected. The pH of the elute was adjusted by adding 2 μL of neutralization buffer (1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.5).27

Analysis of Aβ secretion by human platelets

Washed human platelets from healthy controls (1.2 × 109/mL) were unstimulated or treated with L1 (50 μg/mL) or L5 (25 or 50 μg/mL) for 15 minutes or Aβ (10 μM), thrombin (0.1 IU), or collagen (1 μg/mL) for 6 minutes. Platelets were preincubated with vehicle (0.1% dimethylsulfoxide [DMSO]), TS92 (10 μg/mL), BMS-345541 (25 μM), or Bay1170-82 (20 μM) for 3 minutes before treatment with L5 (25 or 50 μg/mL) for 15 minutes. The reaction was stopped by the addition of EDTA (10 mM). Platelet suspensions were centrifuged and immediately resuspended in lysis buffer. Collected lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting (see supplemental Methods).

Mice

Male C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice (National Laboratory Animal Center, Taiwan) and LOX-1−/− mice28 with a C57BL/6 background (from the laboratory of T.S., Shinshu University School of Medicine, Nagano, Japan) weighing 25 to 35 g were used in this study. All animal protocols conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication no. 85-23, revised 1996) and were approved by the CMU Animal Care and Use Committee.

MCAO induced by using an intraluminal suture method

Mice were anesthetized, and transient focal cerebral ischemia was induced by occluding the right middle cerebral artery for 2 hours with a monofilament nylon thread (6-0) coated with silicon (see supplemental Methods).29,30 Laser Doppler flowmetry was used to confirm induction of ischemia and reperfusion (supplemental Table 1). Mice were injected IV with either L5 or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 60 minutes before undergoing MCAO and then were treated with either the LOX-1 neutralizing antibody TS58 (1 mg/kg; from the laboratory of T.S., Shinshu University School of Medicine, Nagano, Japan) or PBS 10 minutes before reperfusion (110 minutes after MCAO). At 22 hours after MCAO, mice were euthanized, and coronal sections (1-mm thick) of the brain were obtained, starting 1 mm from the frontal pole. Sections of the brain were stained with 2% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium (TTC) and were photographed with a digital camera. The infarct areas (white) were measured by a blinded evaluator using a computerized image analyzer (Image-Pro Plus).

Tape removal test

The tape removal test was conducted at 24 hours after surgery (reperfusion) (see supplemental Methods). We assigned a score of 180 seconds if the mice did not succeed in removing the tape in <180 seconds.30 Sham-operated mice were used as controls.

Fluorescein sodium-induced platelet thrombi in mesenteric microvessels of mice

Mice (C57BL/6 [WT] or LOX-1−/−) were anesthetized, and an external jugular vein was cannulated with polyethylene-10 tubing to administer the dye and drugs. A segment of the small intestine was placed onto a transparent culture dish for microscopic observation. Microthrombi were produced by irradiating selected venules (30-40 μm) with filtered light in which wavelengths below 520 nm had been eliminated. Fluorescein sodium (15 µg/kg) was administered, and 1 minute later, L5 (5 mg/kg), L1 (5 mg/kg), TS58 (1 mg/kg), or isovolumetric PBS solution (control) was given. We measured the time it took to induce formation of a thrombus that led to cessation of blood flow.11

Tail-bleeding time

L5 or L1 (5 mg/kg each, from ischemic stroke patients), Aβ, TS58, or saline (negative control) was injected into the tail vein, or the IKK2 inhibitor BMS-345541 (10 mg/kg in 3% Tween 80) was administered via oral gavage in C57BL/6 or LOX-1−/− mice (n = 12 for each treatment group). Mice were anesthetized (see supplemental Methods), and tail-bleeding time was determined (see supplemental Methods).16

Flow cytometric analysis of GPIIb/IIIa activation on human platelets

The activation of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GPIIb/IIIa) on human platelets was determined by using flow cytometry to measure the binding of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled fibrinogen (FITC-fibrinogen) to platelets (see supplemental Methods). Data are expressed as the ratio of the mean fluorescence intensity of the experimental group divided by that of the solvent control group.16

Platelet aggregation

Platelet aggregation was measured by using a turbidimetric aggregation-monitoring device (AggRAM; Helena Laboratories, Beaumont, TX) (see supplemental Methods). Human platelet suspensions (3.6 × 108 platelets per mL, 0.4 mL) were pretreated with or without reagents (vehicle [0.1% DMSO], 25 μM BMS-345541, or 20 μM Bay 1170-82) for 3 minutes, followed by the addition of L5 (25 μg/mL) and Aβ (10 μM) for at least 6 minutes. The extent of aggregation was expressed in light-transmission units.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as relative frequencies for discrete responses and as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous responses. Comparisons of 3 or more groups were performed by using analysis of variance. The Bonferroni adjustment was used for post hoc comparisons. If the initial analysis of variance P value was not significant, no further post hoc comparisons were performed. A Student t test and χ2 test were used to compare the difference between 2 groups. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. The Statistical Package for Social Science (version 19.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used to perform all statistical analyses.

Results

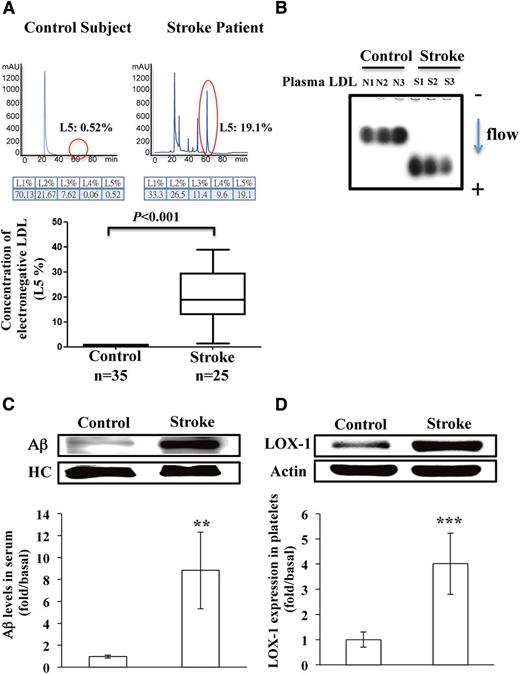

Plasma L5 levels, serum Aβ levels, and platelet expression of LOX-1 are significantly elevated in patients with ischemic stroke

Characteristics and biochemical profiles of ischemic stroke patients and control subjects are shown in Table 1. Between groups, no significant differences were observed in mean levels of total cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), or LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) or in the LDL-C/HDL-C ratio. These data indicate that absolute LDL-C levels in this group of ischemic stroke patients did not determine risk for developing cerebral vascular disease. However, the mean percentage of L5 in LDL (L5%) and L5 concentration ([L5]) were significantly higher in ischemic stroke patients than in controls (P < .001; Table 1). Moreover, the results of FPLC showed that atherogenic L5 was present at higher levels in ischemic stroke patients than in controls, whereas L1 (the least electronegative LDL subfraction) levels were similar between groups (Figure 1A). To further confirm the electronegativity of LDL subfractions, we showed that the electrophoretic mobility of LDL from ischemic stroke patients was greater than that of LDL from controls (Figure 1B). In addition, we found that Aβ levels were significantly higher in the serum of ischemic stroke patients than in that of controls (Figure 1C; P < .01; n = 8). Furthermore, the expression of LOX-1, the L5 receptor, was significantly higher in platelets of ischemic stroke patients than in those of control subjects (Figure 1D; P < .001; n = 8).

Patient characteristics and biochemical profiles

| . | Control subjects, n = 35 . | Stroke patients, n = 25 . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men:women | 19:16 | 21:04 | — |

| Age, y | 49.5 ± 16.9 | 56.0 ± 12.5 | — |

| T-CHOL, mg/dL | 150.8 ± 32.9 | 151.4 ± 34.3 | .28 |

| TG, mg/dL | 109 ± 38.5 | 123.8 ± 72.5 | .46 |

| LDL-C/HDL-C | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | .06 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 41.8 ± 12.1 | 32.7 ± 6.6 | .16 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 92.6 ± 33.5 | 105.4 ± 34.5 | .20 |

| L5/LDL% | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 19.1 ± 10.6 | <.001 |

| [L5], mg/dL† | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 20.6 ± 13.5 | <.001 |

| . | Control subjects, n = 35 . | Stroke patients, n = 25 . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men:women | 19:16 | 21:04 | — |

| Age, y | 49.5 ± 16.9 | 56.0 ± 12.5 | — |

| T-CHOL, mg/dL | 150.8 ± 32.9 | 151.4 ± 34.3 | .28 |

| TG, mg/dL | 109 ± 38.5 | 123.8 ± 72.5 | .46 |

| LDL-C/HDL-C | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | .06 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 41.8 ± 12.1 | 32.7 ± 6.6 | .16 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 92.6 ± 33.5 | 105.4 ± 34.5 | .20 |

| L5/LDL% | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 19.1 ± 10.6 | <.001 |

| [L5], mg/dL† | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 20.6 ± 13.5 | <.001 |

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

[L5], concentration of L5; L5/LDL%, L5 percentage in LDL; T-CHOL, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

P value determined by using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

L5/LDL % × LDL-C (in milligrams per deciliter).

Elevated plasma L5 levels in patients with ischemic stroke. (A) Representative results from FPLC with anion exchange columns showing the distribution of LDL subfractions in a patient with ischemic stroke and a normal control subject. The red circles indicate L5. The L5% is plotted for the control subjects and the ischemic stroke patients. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of plasma LDL from 3 normal control subjects (N1, N2, and N3) and from 3 patients with acute ischemic stroke (S1, S2, and S3). The arrow indicates the direction of electron flow. (C) Immunoprecipitation isolation and western blot analysis of Aβ secreted in the serum of control subjects or patients with ischemic stroke (n = 8). (D) Western blot analysis of LOX-1 expression on the platelets of control subjects or patients with ischemic stroke (n = 8). Quantified results are expressed as the mean ± SD; P values were determined by using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. **P < .01; ***P < .001 vs the control group. HC, heavy chain of IgG antibody; mAU, milliabsorbance units.

Elevated plasma L5 levels in patients with ischemic stroke. (A) Representative results from FPLC with anion exchange columns showing the distribution of LDL subfractions in a patient with ischemic stroke and a normal control subject. The red circles indicate L5. The L5% is plotted for the control subjects and the ischemic stroke patients. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of plasma LDL from 3 normal control subjects (N1, N2, and N3) and from 3 patients with acute ischemic stroke (S1, S2, and S3). The arrow indicates the direction of electron flow. (C) Immunoprecipitation isolation and western blot analysis of Aβ secreted in the serum of control subjects or patients with ischemic stroke (n = 8). (D) Western blot analysis of LOX-1 expression on the platelets of control subjects or patients with ischemic stroke (n = 8). Quantified results are expressed as the mean ± SD; P values were determined by using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. **P < .01; ***P < .001 vs the control group. HC, heavy chain of IgG antibody; mAU, milliabsorbance units.

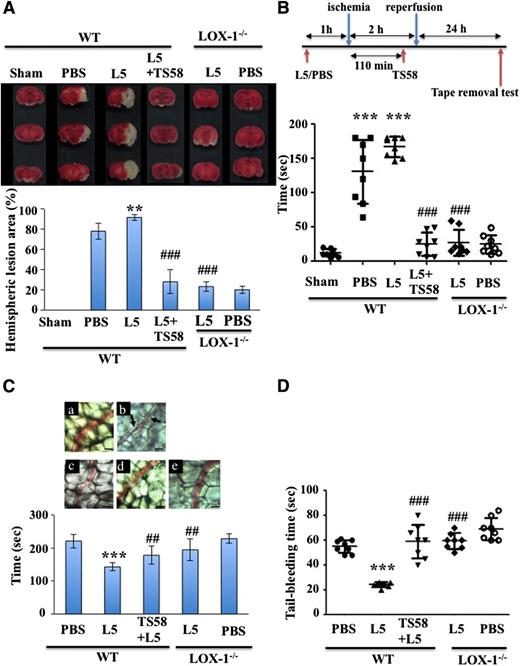

LOX-1 plays an essential role in cerebral ischemia, and neutralizing LOX-1 improves stroke outcome after cerebral ischemia

We assessed the role of L5 and its receptor, LOX-1, in ischemic stroke. Mice treated with L5 isolated from patients with ischemic stroke showed significantly increased infarct volume after MCAO compared with control mice treated with PBS (Figure 2A, P < .01). The infarct volume did not differ between PBS- and L1-treated mice (data not shown). To address the importance of LOX-1 levels in L5-induced stroke outcome, we subjected WT and LOX-1−/− mice to an additional period of L5 (5 mg/kg) treatment 60 minutes before 2 hours of focal cerebral ischemia. Then, 24 hours later, the brain tissue was stained to quantify infarct size (Figure 2A). We found that L5-treated LOX-1−/− mice had a threefold to fourfold reduction in infarct volume compared with L5-treated WT mice (P < .001). Thus, the effect of L5 on stroke outcome depended on its action on LOX-1 (Figure 2A). Because the lack of endogenous LOX-1 receptors blunts the effects of ischemic stroke, we examined the therapeutic potential of infusing TS58, a LOX-1 neutralizing antibody, into WT mice. To mimic the clinical scenario, we infused the antibody 110 minutes after ischemic occlusion, just before reperfusion. WT mice with MCAO that were treated with both L5 and TS58 had a threefold reduction in infarct volume compared with WT mice treated only with L5 (Figure 2A, P < .001). In addition, to test whether the reduction in infarct volume improved functional outcome, we performed the tape removal test, which is used to assess sensory and motor impairments in forepaw function.31,32 At 24 hours after surgery in mice that underwent a 2-hour MCAO, those that were treated with PBS or L5 required significantly more time to remove adhesive tape from the contralateral and ipsilateral paws than did sham-operated mice (Figure 2B, P < .001). This finding supports those of previous reports.31 Furthermore, in L5-treated mice we found that additional treatment with TS58, a LOX-1 neutralizing antibody, significantly shortened the time to remove the adhesive tape from the paws (P < .001), indicating improved sensorimotor performance in mice with neutralized LOX-1 (Figure 2B). A similar effect was seen in LOX-1−/− mice treated with L5 or PBS. Thus, our results show that LOX-1 neutralizing antibody TS58 has a protective effect when infused after cerebral ischemia.

Levels of L5 and LOX-1, L5’s receptor, regulate infarct volume after ischemic stroke in mice. (A) Representative TTC stains of a coronal section of brain tissue for 1 mouse per group at 24 hours after focal cerebral ischemia (top) and the quantification of corresponding brain infarct volumes (bottom) in WT mice treated with PBS, L5 (5 mg/kg), or L1 (5 mg/kg) for 60 minutes before MCAO in addition to TS58 (1 mg/kg, a LOX-1 neutralizing antibody) 110 minutes after MCAO, or in LOX-1−/− mice treated with L5 or PBS. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 8). **P < .01 vs PBS control; ###P < .001 vs L5-treated WT mice. (B) TS58 treatment improved performance in the tape removal test after ischemic stroke. The time needed to remove tape from both the contralateral and ipsilateral paws was recorded for sham-operated mice, WT mice that were treated either with PBS or L5 for 60 minutes before undergoing MCAO and reperfusion, and WT mice treated with L5 (5 mg/kg) for 60 minutes before MCAO and then treated with TS58 (1 mg/kg) 10 minutes before reperfusion. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 8). ***P < .001 vs sham control; ###P < .001 vs L5-treated WT mice. (C) LOX-1 neutralizing antibody inhibits the L5-induced shortening of occlusion times for inducing thrombus formation in mesenteric venules of mice. Mice (WT and LOX-1−/−) were administered isovolumetric PBS solution, L5 (5 mg/kg), or TS58 (1 mg/kg) + L5 (5 mg/kg), and then mesenteric venules were selected for irradiation to induce microthrombus formation. (a) WT mice treated with PBS; (b) WT mice treated with L5; (c) WT mice treated with TS58 and L5; (d) LOX-1−/− mice treated with L5; (e) LOX-1−/− mice treated with PBS. Microscopic images (×400) obtained during the 143-second time period after the injection of fluorescent sodium (15 μg/kg) and transillumination in mice treated with PBS, L5 (5 mg/kg), or TS58 (1 mg/kg) + L5 (5 mg/kg). Arrows indicate platelet plug formation. Photographs are representative of 8 similar experiments. Bar, 30 μm. Data in the bar graph are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 8). ***P < .001 vs PBS control; ##P < .01 vs L5-treated WT mice. (D) TS58 treatment prolongs tail-bleeding time in L5-treated mice. Tail-bleeding time was determined after treatment with PBS or L5 (5 mg/kg) in LOX-1−/− mice and after treatment with PBS, L5 (5 mg/kg), or TS58 (1 mg/kg) + L5 (5 mg/kg) in WT mice. Data represent the time from tail amputation to the time of blood flow cessation for longer than 10 seconds. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 12). ***P < .001 vs PBS-treated WT mice; ###P < .001 vs L5-treated WT mice.

Levels of L5 and LOX-1, L5’s receptor, regulate infarct volume after ischemic stroke in mice. (A) Representative TTC stains of a coronal section of brain tissue for 1 mouse per group at 24 hours after focal cerebral ischemia (top) and the quantification of corresponding brain infarct volumes (bottom) in WT mice treated with PBS, L5 (5 mg/kg), or L1 (5 mg/kg) for 60 minutes before MCAO in addition to TS58 (1 mg/kg, a LOX-1 neutralizing antibody) 110 minutes after MCAO, or in LOX-1−/− mice treated with L5 or PBS. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 8). **P < .01 vs PBS control; ###P < .001 vs L5-treated WT mice. (B) TS58 treatment improved performance in the tape removal test after ischemic stroke. The time needed to remove tape from both the contralateral and ipsilateral paws was recorded for sham-operated mice, WT mice that were treated either with PBS or L5 for 60 minutes before undergoing MCAO and reperfusion, and WT mice treated with L5 (5 mg/kg) for 60 minutes before MCAO and then treated with TS58 (1 mg/kg) 10 minutes before reperfusion. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 8). ***P < .001 vs sham control; ###P < .001 vs L5-treated WT mice. (C) LOX-1 neutralizing antibody inhibits the L5-induced shortening of occlusion times for inducing thrombus formation in mesenteric venules of mice. Mice (WT and LOX-1−/−) were administered isovolumetric PBS solution, L5 (5 mg/kg), or TS58 (1 mg/kg) + L5 (5 mg/kg), and then mesenteric venules were selected for irradiation to induce microthrombus formation. (a) WT mice treated with PBS; (b) WT mice treated with L5; (c) WT mice treated with TS58 and L5; (d) LOX-1−/− mice treated with L5; (e) LOX-1−/− mice treated with PBS. Microscopic images (×400) obtained during the 143-second time period after the injection of fluorescent sodium (15 μg/kg) and transillumination in mice treated with PBS, L5 (5 mg/kg), or TS58 (1 mg/kg) + L5 (5 mg/kg). Arrows indicate platelet plug formation. Photographs are representative of 8 similar experiments. Bar, 30 μm. Data in the bar graph are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 8). ***P < .001 vs PBS control; ##P < .01 vs L5-treated WT mice. (D) TS58 treatment prolongs tail-bleeding time in L5-treated mice. Tail-bleeding time was determined after treatment with PBS or L5 (5 mg/kg) in LOX-1−/− mice and after treatment with PBS, L5 (5 mg/kg), or TS58 (1 mg/kg) + L5 (5 mg/kg) in WT mice. Data represent the time from tail amputation to the time of blood flow cessation for longer than 10 seconds. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 12). ***P < .001 vs PBS-treated WT mice; ###P < .001 vs L5-treated WT mice.

L5 enhances thrombus formation in microvessels of fluorescein sodium-pretreated mice

During the stasis period, thrombi form in the artery because this MCAO stroke model is highly dependent on platelets and their adhesion receptors, including the receptors for von Willebrand factor, β3 integrin, and GPIβα.33,34 We were able to visualize thrombi in the microcirculation in the infarcted area (Figure 2C). On average, thrombi formed in microvessels 221 seconds after fluorescein sodium (15 mg/kg) treatment. L5 (5 mg/kg) treatment in WT mice markedly shortened the time required for fluorescein sodium to induce thrombus formation (221 ± 20 seconds in fluorescein sodium + PBS vs 143 ± 12 seconds in fluorescein sodium + L5; P < .001). However, TS58 treatment and LOX-1 deficiency prolonged the time required for microthrombus formation in L5-treated mice (fluorescein sodium + TS58 + L5 in WT mice: 178 ± 27 seconds, P < .01; fluorescein sodium + L5 in LOX-1−/− mice: 195 ± 32 seconds, P < .01). Figure 2C shows a typical microthrombus formed after fluorescein sodium treatment. The thrombotic platelet plug was not seen in PBS-treated mice (control) in which mesenteric microvessels were irradiated for 143 seconds after fluorescein sodium treatment (Figure 2Ca). Platelet plug formation was evident at 143 seconds after irradiation in L5-treated mice (Figure 2Cb). However, TS58 treatment and LOX-1 deficiency prolonged the time to microthrombus formation in L5-treated mice (Figure 2Cc-d). PBS-treated LOX-1−/− mice served as a control (Figure 2Ce).

L5 enhances thrombus formation in the middle cerebral artery in mice pretreated with FeCl3

In another experimental stroke model, FeCl3 can be used to induce arterial thrombosis in the middle cerebral artery of mice, mimicking occlusive cerebral thrombosis35 with a morphology similar to that found in humans36 (supplemental Figure 1A). To corroborate our findings in this stroke model, we injected L5 (5 mg/kg) from stroke patients, TS58 (1 mg/kg), or PBS (negative control) into the tail vein of adult male C57BL/6 or LOX-1−/− mice (n = 5 for each treatment group per mouse type). After 30 minutes, the mice were anesthetized, and the occlusion time was assessed (supplemental Figure 1B). The time to occlusion was significantly shorter in L5-treated C57BL/6 mice than in PBS-injected C57BL/6 mice (P < .001; supplemental Figure 1C-D). Furthermore, TS58 treatment or LOX-1 deficiency in L5-treated mice prolonged the time required for microthrombus formation compared with L5-injected C57BL/6 mice (P < .01; supplemental Figure 1D). Moreover, infarct volume was significantly increased in L5-treated C57BL/6 mice compared with PBS-injected C57BL/6 mice after MCAO with FeCl3 (P < .01; supplemental Figure 1E). Among L5-treated mice, those that were also treated with TS58 and those that were LOX-1 deficient had significantly reduced infarct volumes compared with WT mice treated only with L5 (P < .001). These results further support our evidence that L5 and LOX-1 play an essential role in thrombosis in the setting of ischemic stroke.

TS58 infusion prolongs tail-bleeding time but does not cause cerebral hemorrhage in mice

We did not detect cerebral hemorrhage in any WT or LOX-1−/− mice treated with TS58 (data not shown). In addition, platelet count (supplemental Figure 2A) and surface glycoprotein expression (GPIIb/IIIa; supplemental Figure 2B) were not statistically different between mice treated with the LOX-1 neutralizing antibody TS58 and control mice treated with immunoglobulin G (IgG). Therefore, the role of platelets in preventing hemorrhage at stroke sites is preserved in the absence of the LOX-1 receptor. To examine the effect of LOX-1 deficiency on peripheral hemostasis, we measured tail-bleeding time in WT mice and those treated with L5 or PBS. In the WT group, bleeding time was significantly shorter in L5-treated mice than in PBS-treated control mice (P < .001, Figure 2D). However, bleeding time was significantly prolonged in L5-treated WT mice exposed to LOX-1 neutralizing antibody TS58 and in L5-treated LOX-1−/− mice when compared with L5-treated WT mice (P < .001; Figure 2D).

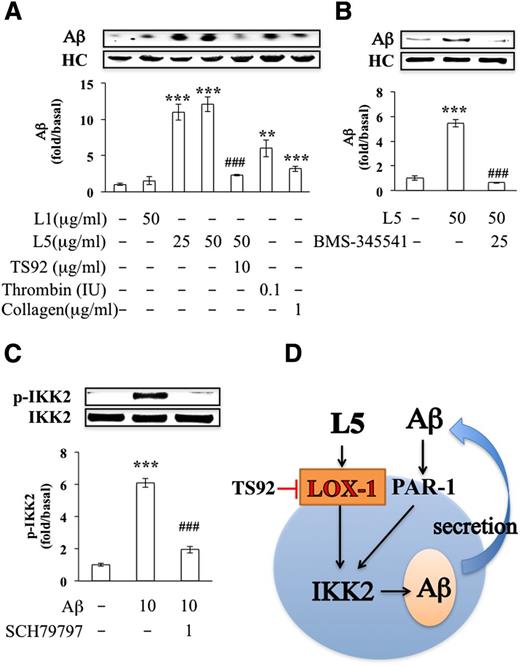

L5 from ischemic stroke patients induces Aβ secretion in human platelets

We previously showed that L5 potently induces platelet activation and granule release via LOX-1.16 When we examined the effects of L5 on the secretion of Aβ by platelets in vitro, we found that exogenous L5 isolated from patients with ischemic stroke significantly induced Aβ secretion in human platelets, whereas L1 had no significant effect (Figure 3A). As reported previously, thrombin (0.1 IU) or collagen (1 μg/mL) also induced Aβ secretion in human platelets.9 Furthermore, the addition of TS92 (10 μg/mL), a human LOX-1 antagonist, and BMS-345541 (25 μM), a small-molecule inhibitor of IKK2, significantly blocked L5-induced Aβ secretion in human platelets (Figure 3A-B). In addition, secreted Aβ activated the phosphorylation of IKK2, which was attenuated by SCH79797, a proteinase activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) antagonist (1 μM) (Figure 3C). Moreover, in mice injected with L5, the secretion of Aβ in the serum was increased (data not shown). These data indicate that L5 induced the secretion of Aβ via LOX-1 and IKK2 activation and that secreted Aβ stimulated the phosphorylation of IKK2 via PAR-1 (Figure 3D).

L5-induced secretion of Aβ in human platelets. (A-B) Immunoprecipitation isolation and western blot analysis of Aβ secretion in washed human platelets (1.2 × 109/mL) that were incubated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), L1 (50 μg/mL), L5 (25 or 50 μg/mL), thrombin (0.1 IU), or collagen (1 μg/mL). Platelets were preincubated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO; first column), TS92 (10 μg/mL), or BMS-345541 (25 μM) before treatment with L5 (50 μg/mL). Quantified results are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 4); P values were determined by using the Student t test. **P < .01, ***P < .001 vs the vehicle-treated control group; ###P < .001 vs the L5-treated group. (C) Western blot analysis showing the activation (phosphorylation) of IKK2 (ie, p-IKK2) by Aβ in the presence or absence of SCH79797, an antagonist of PAR-1 (1 μM). Results are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 4); P values were determined by using the Student t test. ***P < .001 vs the PBS-treated control group; ###P < .001 vs the Aβ-treated group. (D) A working model for L5-induced Aβ secretion. Black arrow, stimulation; red line with end bar, inhibition; blue arrow, direction or flow. HC, heavy chain of IgG antibody.

L5-induced secretion of Aβ in human platelets. (A-B) Immunoprecipitation isolation and western blot analysis of Aβ secretion in washed human platelets (1.2 × 109/mL) that were incubated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), L1 (50 μg/mL), L5 (25 or 50 μg/mL), thrombin (0.1 IU), or collagen (1 μg/mL). Platelets were preincubated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO; first column), TS92 (10 μg/mL), or BMS-345541 (25 μM) before treatment with L5 (50 μg/mL). Quantified results are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 4); P values were determined by using the Student t test. **P < .01, ***P < .001 vs the vehicle-treated control group; ###P < .001 vs the L5-treated group. (C) Western blot analysis showing the activation (phosphorylation) of IKK2 (ie, p-IKK2) by Aβ in the presence or absence of SCH79797, an antagonist of PAR-1 (1 μM). Results are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 4); P values were determined by using the Student t test. ***P < .001 vs the PBS-treated control group; ###P < .001 vs the Aβ-treated group. (D) A working model for L5-induced Aβ secretion. Black arrow, stimulation; red line with end bar, inhibition; blue arrow, direction or flow. HC, heavy chain of IgG antibody.

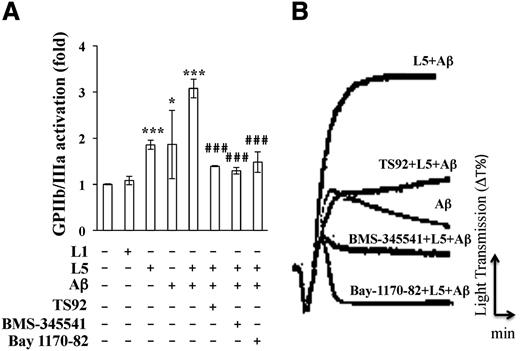

Aβ and L5 synergistically induce platelet aggregation and activation

Previous studies have shown that Aβ induces platelet activation and aggregation9 and that L5 enhances platelet aggregation.16 Therefore, we examined whether L5 enhances Aβ-induced platelet aggregation and whether the synergism between L5 and Aβ is critical in thrombosis that leads to ischemic stroke. GPIIb/IIIa is the main platelet receptor that mediates platelet aggregation. Upon activation, GPIIb/IIIa binds to fibrinogen and promotes platelet adhesion and aggregation. We found that GPIIb/IIIa receptor activation in human platelets was increased by the addition of L5 (25 μg/mL) or Aβ (10 μM) from ischemic stroke patients, but not by L1 (50 μg/mL). In addition, when L5 and Aβ were combined, GPIIb/IIIa receptor activation was higher than that in human platelets treated with either L5 or Aβ alone (Figure 4A), suggesting that L5 and Aβ activate GPIIb/IIIa synergistically. Furthermore, the L5+Aβ-induced activation of GPIIb/IIIa was blocked by the addition of the LOX-1 antagonist TS92 (10 μg/mL), the IKK2 inhibitor BMS-34551 (25 μM), and the NF-κB inhibitor Bay 117-82 (20 μM), indicating that L5+Aβ-induced platelet activation occurs via LOX-1, IKK2, and NF-κB signaling. When we examined platelet aggregation by using an aggregometer, we found that L5 (25 μg/mL) from ischemic stroke patients significantly increased platelet aggregation in the presence of Aβ, and this effect was blocked by the human LOX-1 antagonist TS92 (10 μg/mL), the IKK2 inhibitor BMS-345541 (25 μM), and the NF-κB inhibitor Bay 117-82 (20 μM) (Figure 4B). Furthermore, platelet aggregation induced by L5+Aβ was inhibited in the platelets of TS58-injected mice when compared with those of control IgG-injected mice (supplemental Figure 2C). Moreover, platelet aggregation was lower in platelet-rich plasma (PRP) from LOX-1−/− mice than in the PRP from LOX-1+/+ mice (control group) after stimulation by L5 with Aβ (supplemental Figure 3).

Synergistic effects of L5 and Aβ on GPIIb/IIIa activation and aggregation in human platelets. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of GPIIb/IIIa-activated platelets that were pretreated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO; first column), TS92 (10 μg/mL), BMS-345541 (25 μM), or Bay1170-82 (20 μM), before the addition of L1 (50 μg/mL), L5 (25 μg/mL), or Aβ (10 μM), followed by 2 μL of FITC-fibrinogen. Data are expressed as a ratio to the vehicle-treated control (Ctl) group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 6); *P < .05, ***P < .001 vs vehicle-treated control; ###P < .001 vs L5+Aβ-treated group. P values were determined by using 1-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni post hoc test. (B) Platelet aggregation was measured with a platelet aggregometer. Washed platelets (3.6 × 108/mL) were treated with Aβ (10 μM) or L5 (25 μg/mL) and Aβ (10 μM). Platelets were preincubated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), TS92 (10 μg/mL), BMS-345541 (25 μΜ), or Bay1170-82 (20 μM) before the addition of L5 and Aβ. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments with similar results.

Synergistic effects of L5 and Aβ on GPIIb/IIIa activation and aggregation in human platelets. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of GPIIb/IIIa-activated platelets that were pretreated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO; first column), TS92 (10 μg/mL), BMS-345541 (25 μM), or Bay1170-82 (20 μM), before the addition of L1 (50 μg/mL), L5 (25 μg/mL), or Aβ (10 μM), followed by 2 μL of FITC-fibrinogen. Data are expressed as a ratio to the vehicle-treated control (Ctl) group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 6); *P < .05, ***P < .001 vs vehicle-treated control; ###P < .001 vs L5+Aβ-treated group. P values were determined by using 1-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni post hoc test. (B) Platelet aggregation was measured with a platelet aggregometer. Washed platelets (3.6 × 108/mL) were treated with Aβ (10 μM) or L5 (25 μg/mL) and Aβ (10 μM). Platelets were preincubated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), TS92 (10 μg/mL), BMS-345541 (25 μΜ), or Bay1170-82 (20 μM) before the addition of L5 and Aβ. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments with similar results.

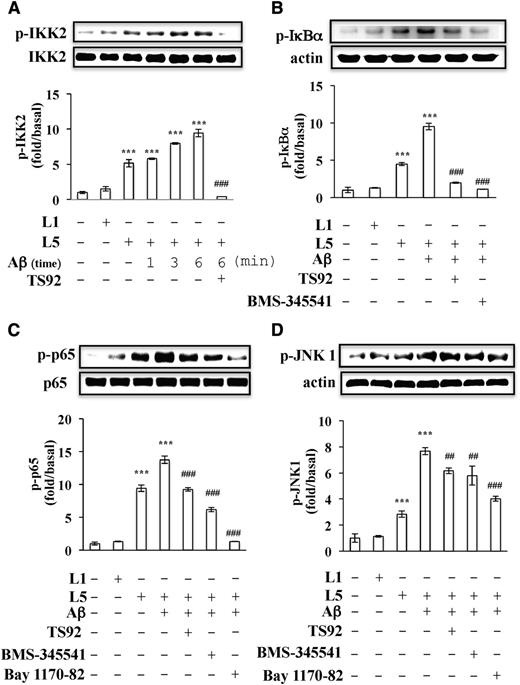

Previous studies have shown that IκB is phosphorylated on Ser32 upon platelet activation, indicating that IKK2 is activated in stimulated platelets. We investigated whether L5 and Aβ synergistically induce the phosphorylation of IKK2 and the activation of NF-κB in anucleated human platelets. L5+Aβ increased the phosphorylation of IKK2 in platelets in a time-dependent manner (Figure 5A). In addition, the phosphorylation of IκBα and p65 (NF-κB) occurred in platelets activated with L5+Aβ, and this phosphorylation was blocked by LOX-1 antagonist TS92 (10 μg/mL), IKK2 inhibitor BMS-34551 (25 μM), and NF-κB inhibitor Bay 117-82 (20 μM) (Figure 5B-C).

Signaling pathways activated by L5 and Aβ in human platelets. Washed human platelets (1 × 109/mL) were preincubated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), TS92 (10 μg/mL), BMS-345541 (25 μM), or Bay1170-82 (20 μM) before the addition of L5 (25 μg/mL), L1 (50 μg/mL), or Aβ (10 μM). Platelets were incubated with Aβ for 6 minutes unless otherwise indicated. Western blot analyses of (A) IKK2 phosphorylation (p-IKK2), (B) IκBα phosphorylation (p-IκBα), (C) p65 phosphorylation (p-p65), and (D) JNK1 phosphorylation (p-JNK1). Results are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 4); P values were determined by using the Student t test. ***P < .001 vs the vehicle-treated control group; ##P < .01, ###P < .001 vs the L5+Aβ-treated group.

Signaling pathways activated by L5 and Aβ in human platelets. Washed human platelets (1 × 109/mL) were preincubated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), TS92 (10 μg/mL), BMS-345541 (25 μM), or Bay1170-82 (20 μM) before the addition of L5 (25 μg/mL), L1 (50 μg/mL), or Aβ (10 μM). Platelets were incubated with Aβ for 6 minutes unless otherwise indicated. Western blot analyses of (A) IKK2 phosphorylation (p-IKK2), (B) IκBα phosphorylation (p-IκBα), (C) p65 phosphorylation (p-p65), and (D) JNK1 phosphorylation (p-JNK1). Results are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 4); P values were determined by using the Student t test. ***P < .001 vs the vehicle-treated control group; ##P < .01, ###P < .001 vs the L5+Aβ-treated group.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) can be regulated by NF-κB activation in human platelets.37 Three MAPKs have been identified in platelets, including extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) p38 MAPK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1).9 We found that L5+Aβ induced the phosphorylation of JNK1 (Figure 5D) but not ERK or p38 MAPK (data not shown) in human platelets. Furthermore, human LOX-1 antagonist TS92 (10 μg/mL), IKK2 inhibitor BMS-34551 (25 μM), and NF-κB inhibitor Bay 117-82 (20 μM) significantly inhibited L5+Aβ-induced JNK1 phosphorylation in human platelets (Figure 5D). These results suggest that the LOX-1 and PAR-1/IKK2/IκBα/NF-κB/JNK1 cascade may play a crucial role in platelet activation induced by L5+Aβ.

Inhibiting IKK2 attenuates the effects of L5 and Aβ on tail-bleeding time

To investigate the effects of the L5+Aβ-induced activation of IKK2 and NF-κB on the hemostatic response in vivo, we performed tail-bleeding experiments. In mice injected with L5 (5 mg/kg), Aβ (1 mg/kg), or L5+Aβ, tail-bleeding times after 30 minutes were 44%, 9%, or 50% shorter, respectively, than those in mice injected with L1 (5 mg/kg) (n = 12; P < .05). When we evaluated the therapeutic effect of the IKK2 inhibitor BMS34551, we found that mice injected with L5+Aβ and administered 10 mg/kg BMS34551 via oral gavage 2 hours before the induction of tail bleeding had significantly prolonged tail-bleeding times when compared with those in mice injected with L5+Aβ only (Figure 638 ). These findings indicate that inhibiting IKK2 may prevent L5+Aβ-induced thrombosis.

Effect of L5 and Aβ on tail-bleeding time in C57BL/6 mice. Tail-bleeding times were determined after treatment with vehicle (injection of 40 μL of saline with the administration of 3% Tween 80 [5 mL/kg] via oral gavage), L5 injection (5 mg/kg), Aβ injection (1 mg/kg), or L5+Aβ injection with or without the administration of BMS-345541 (10 mg/kg in 3% Tween 80) via oral gavage (2 hours before the tail-bleeding time experiment38 ) into adult male C57BL/6 mice. Data represent the time of tail amputation to the time of blood flow cessation for >10 seconds. Bar graphs show compiled data (n = 12). *P < .05, **P < .01 vs vehicle-treated control mice; #P < .05 vs L5+Aβ-treated mice.

Effect of L5 and Aβ on tail-bleeding time in C57BL/6 mice. Tail-bleeding times were determined after treatment with vehicle (injection of 40 μL of saline with the administration of 3% Tween 80 [5 mL/kg] via oral gavage), L5 injection (5 mg/kg), Aβ injection (1 mg/kg), or L5+Aβ injection with or without the administration of BMS-345541 (10 mg/kg in 3% Tween 80) via oral gavage (2 hours before the tail-bleeding time experiment38 ) into adult male C57BL/6 mice. Data represent the time of tail amputation to the time of blood flow cessation for >10 seconds. Bar graphs show compiled data (n = 12). *P < .05, **P < .01 vs vehicle-treated control mice; #P < .05 vs L5+Aβ-treated mice.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that L5 is an important regulator of cerebral ischemia and that elevated plasma L5 levels may serve as a potential biomarker for the prediction of ischemic stroke. We found that plasma L5 levels, serum Aβ levels, and platelet expression of LOX-1 are significantly increased in patients with acute ischemic stroke within 24 hours after the onset of ischemia. Moreover, using 2 MCAO mouse models,34,35 we showed that the binding of LOX-1 to L5 intensifies the consequences of ischemic stroke and that neutralizing LOX-1 provides a significant protective effect after stroke. Based on our in vitro and in vivo evidence, we have proposed a synergistic mechanism for L5 and Aβ in the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke (Figure 7), whereby L5 enhances Aβ-triggered platelet activation and aggregation.

A working model for L5-potentiated platelet activation induced by Aβ. Black arrow, stimulation; red line with end bar, inhibition; blue arrow, direction or flow.

A working model for L5-potentiated platelet activation induced by Aβ. Black arrow, stimulation; red line with end bar, inhibition; blue arrow, direction or flow.

High plasma levels of cholesterol, particularly LDL-C, are a risk factor for ischemic stroke.39 LDL plays an indispensable role as a carrier for cholesterol and other forms of lipids, but its excess levels in the serum or its stress-induced chemical modification can be highly pathogenic, triggering inflammation and inducing atherosclerosis.40 Thus, it is clear that abnormal LDL is a primary etiology of atherosclerosis and its associated complications, such as ischemic stroke. In our study, we found that LDL-C levels were similar between patients with ischemic stroke and control subjects but that plasma L5 levels were significantly elevated in patients with ischemic stroke (19.1% vs 0.52% in control subjects). The reason for the wide variation in L5% among ischemic stroke patients is unclear, although we are currently conducting more comprehensive studies, including time-course analysis, to further examine this issue. According to recent studies, an L5 concentration of 25 to 50 μg/mL was sufficient to induce apoptosis in human aortic ECs and to trigger platelet activation.16,41 Therefore, a high concentration of L5 is more likely a causative factor in the prothrombotic phenotype of ischemic stroke patients than a consequence of it. Moreover, expression of LOX-1, the L5 receptor, may also be an important risk factor for atherosclerosis and stroke.

The causative role of L5 in acute cardiocerebral ischemia is further substantiated by the finding that thrombi from culprit coronary arteries in STEMI patients show increased expression of LOX-1, which is known to internalize L5 into endothelial cells and macrophages.42 In vivo, the basal expression of LOX-1 is low but is enhanced in patients with one of several pathological conditions, including hypertension,43 diabetes mellitus,44 and hyperlipidemia.45 Consistent with these findings, we found that LOX-1 expression was significantly higher in platelets from ischemic stroke patients than in those from control subjects. Furthermore, we identified LOX-1 as an important regulator of cerebral ischemia (Figure 2). Both neutralizing LOX-1 and LOX-1 deficiency provided significant protection after experimental stroke in mice. LOX-1 is involved in endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, atherogenesis, myocardial infarction, vascular lipid retention under hypertension, and intimal thickening after balloon catheter injury.17,18,46-48 Moreover, we found a higher expression of LOX-1 in patients with ischemic stroke than in controls (Figure 1D). This prompted us to investigate whether LOX-1 plays an active role in ischemic stroke. Our results showed that deficiency of LOX-1 dramatically reduced infarct volume at 24 hours after cerebral ischemia. Furthermore, L5-treated LOX-1−/− mice had better motor and global neurologic function than did WT mice treated with L5 or PBS undergoing the same surgery (MCAO). These findings were corroborated by our results in an in situ model of FeCl3-induced thrombosis in the middle cerebral artery of mice,35 which showed that L5 reduced ischemic occlusion time and infarct volume in WT mice but that LOX-1 neutralization with TS58 or LOX-1 deficiency attenuated the effects of L5 (supplemental Figure 1). Together, these findings indicate that the effect of L5 on stroke depends on its action on LOX-1.

LOX-1 is a multiligand receptor that is expressed not only on platelets, but also on several other types of cells, including endothelial cells, macrophages, and mast cells, that are critical in the setting of ischemic stroke. To rule out the effects of other cell types on platelets, we examined L5+Aβ-induced platelet aggregation in PRP isolated from LOX-1−/− and C57BL/6 (LOX-1+/+) control mice. After stimulation by L5 with Aβ, platelet aggregation was lower in the PRP from LOX-1−/− mice than in the PRP from LOX-1+/+ mice (supplemental Figure 3), suggesting that platelet LOX-1 plays a specific role in L5+Aβ-induced platelet aggregation. Additionally, we showed that Aβ secretion was blocked by TS92 (a LOX-1 antagonist) in human platelets (Figure 3A) and that TS92 can inhibit human platelet aggregation induced by L5 with Aβ (Figure 4B). Together, these findings indicate that platelet LOX-1 plays a key role in platelet aggregation. Although we have emphasized the role of platelet LOX-1, we did not rule out the contribution of other cell types (eg, endothelial cells) to the progression of stroke.

It was recently shown that the L5-mediated activation of human platelets requires the protein kinase C-α (PKCα) signaling pathway and that the L5-induced PKCα pathway in platelets is mediated by platelet-activating factor receptor and LOX-1.16 In the present study, we found that LOX-1–mediated IKK2 phosphorylation regulates platelet granule secretion of Aβ, which is also released upon platelet activation by collagen and thrombin.9 In addition, we showed that L5+Aβ synergistically induced the conformational change of GPIIb/IIIa, resulting in platelet activation. Aβ has been shown to damage ECs and augment platelet-EC interactions, including platelet activation and adhesion.9,49 In addition, we previously observed the adhesion of L5-treated platelets to unstimulated, inactivated ECs.16 Activated GPIIb/IIIa (αIIbβ3) is an important receptor on platelets that mediates platelet aggregation by bridging with fibrinogen. In addition, GPIIb/IIIa also interacts with vascular ECs through α5β3. In the presence of soluble fibrinogen, platelets firmly adhere to the surface of ECs by forming a heterotypic interaction with ECs expressing integrin α5β3. Thus, activated platelets increase the activation of GPIIb/IIIa, which promotes platelets to adhere to ECs and to form platelet plaques during the progression of atherothrombosis. Thus, our findings indicate that L5+Aβ may promote the progression of atherothrombosis by upregulating GPIIb/IIIa.

The IκB kinase complex IKK is a central component of the signaling cascade that controls NF-κB–dependent gene transcription.50 IKK2 and NF-κB signaling has been observed in anucleate cells and has been implicated in platelet activation.51,52 In the present study, we showed that, by phosphorylating IKK2, L5+Aβ induced IκBα phosphorylation to activate NF-κB, which led to platelet aggregation via JNK1 phosphorylation. The IKK2 and NF-κB inhibitors Bay1170-82 and BMS-345541, respectively, markedly arrested IKK2-IκBα-NF-κB signaling after L5+Aβ stimulation, suggesting that IKK2 and NF-κB are required for the synergistic effects of L5 and Aβ on platelet activation and aggregation.

To provide evidence of platelet activation specifically caused by L5+Aβ in vivo and to examine whether the inhibition of IKK2 could block the in vivo effects of L5 and Aβ, we performed tail-bleeding experiments. We found that the mean tail-bleeding time was significantly shorter in C57BL/6 mice injected with L5+Aβ than in L1-injected mice and that the effects of L5+Aβ were attenuated in BMS-345541–treated mice. These results support the relationship observed between L5+Aβ and platelet activation in vitro. Furthermore, the inhibitory effects of BMS-345541 on L5-mediated Aβ secretion indicate that the use of an IKK2 inhibitor may represent a novel antithrombotic strategy.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the L5-LOX-1-IKK2 axis plays a crucial role in regulating ischemic stroke, and elevated plasma L5 levels may be a risk factor or predictor for cerebral ischemia. Given our findings that the infusion of LOX-1 neutralizing antibody into WT mice reduced infarct size and improved functional outcome without inducing cerebral hemorrhage, we propose that LOX-1 neutralizing antibody may be a new option for treating ischemic stroke. Furthermore, our results suggest that using a small-molecule inhibitor of IKK2 may be a potential therapeutic strategy for blocking the prothrombotic effects of L5 and Aβ. Our findings have important implications for both the prevention and treatment of ischemic stroke.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nicole Stancel, ELS, and Rebecca Bartow, of the Texas Heart Institute in Houston, TX, for editorial assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the American Diabetes Association (1-04-RA-13); the National Institutes of Health, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL-63364); the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC102-2320-B-039-058 and 104-2815-C-039-026-B); Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (MOHW104-TDU-B-212-113002 and MOHW105-TDU-B-212-133019); Stroke Biosignature Project Grant of Academia Sinica, Taiwan (BM104010092 and BM10501010037); National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan (NHRI-EX104-10305SI), China Medical University (CMU102-N-02, CMU103-N-08, and CMU104-SR-26); China Medical University Hospital (DMR-102-091 and DMR-105-082); Kaohsiung Medical University (KMU-TP104D00); the Kaohsiung Medical University Alumni Association of America (KMUH-10402); and the Mao-Kuei Lin Research Fund of Chicony Electronics.

Authorship

Contribution: M.-Y.S. planned and performed platelet studies and animal experiments, analyzed data, and participated in writing the manuscript; F.-Y.C. performed animal experiments, analyzed data, and participated in writing the manuscript; J.-F.H. performed clinical experiments, purified L5, and analyzed data; R.-H.F. performed animal experiments; C.-M.C. purified L5 and analyzed data; C.-T.C., C.-H.L., S.-Z.L., W.-C.S., and K.-C.C. performed case enrollment of ischemic stroke patients and interpreted data; J.-R.W., A.-S.L., and H.-C.C. performed experiments; J.-R.S. instructed the design of platelet studies; T.S. contributed vital reagents; and C.-Y.H. and C.-H.C. (principal investigator) revised the manuscript and participated in the study design.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Chu-Huang Chen, Vascular and Medicinal Research, Texas Heart Institute, 6770 Bertner Ave, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: cchen@texasheart.org; or Chung Y. Hsu, Graduate Institute of Clinical Medical Sciences, China Medical University, 2 Yuh-Der Rd, 21st Fl, Taichung, Taiwan; e-mail: hsucy63141@gmail.com.

![Figure 6. Effect of L5 and Aβ on tail-bleeding time in C57BL/6 mice. Tail-bleeding times were determined after treatment with vehicle (injection of 40 μL of saline with the administration of 3% Tween 80 [5 mL/kg] via oral gavage), L5 injection (5 mg/kg), Aβ injection (1 mg/kg), or L5+Aβ injection with or without the administration of BMS-345541 (10 mg/kg in 3% Tween 80) via oral gavage (2 hours before the tail-bleeding time experiment38) into adult male C57BL/6 mice. Data represent the time of tail amputation to the time of blood flow cessation for >10 seconds. Bar graphs show compiled data (n = 12). *P < .05, **P < .01 vs vehicle-treated control mice; #P < .05 vs L5+Aβ-treated mice.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/127/10/10.1182_blood-2015-05-646117/5/m_1336f6.jpeg?Expires=1769124602&Signature=kFFz1~-EJM5waNAHtbrxwavN35CP8Gi~qHdaqvx0wSVgwbgzJvM2nQFa4kjeoRc8JZ3bT9g~P-SoPuH~Hy1BKXl~J~moL-zTIim~sMrNPfj3E7cq1M9ckbWwzqOmpj0QxQZ~PUi583UyuBlZV43iT14a6H5vhzlAIYV7nPs-wgcpSWulDtJKhizzwaYSpz8sSpTZdtD2vhS1sVGNYXNK8vhnv~f56pCCrapavDWvx2nFbKMlAltzABEgwp-CFN26QJ3W~DzfRlU-RDp7s6qW~rqsc5GqtsezZxCYiREHV8x3-vPrz6bAP85cFIB01NlkctpxO8IjyIpgSKJdYe1qZA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)