Abstract

Once thought to be rare disorders, the myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are now recognized as among the most common hematological neoplasms, probably affecting >30 000 patients per year in the United States. US regulatory approval of azacitidine, decitabine, and lenalidomide between 2004 and 2006 seemed to herald a new era in the development of disease-modifying therapies for MDS, but there have been no further drug approvals for MDS indications in the United States in the last 8 years. The available drugs are not curative, and few of the compounds that are currently in development are likely to be approved in the near future. As a result, MDS diagnoses continue to place a heavy burden on both patients and health care systems. Incomplete understanding of disease pathology, the inherent biological complexity of MDS, and the presence of comorbid conditions and poor performance status in the typical older patient with MDS have been major impediments to development of effective novel therapies. Here we discuss new insights from genomic discoveries that are illuminating MDS pathogenesis, increasing diagnostic accuracy, and refining prognostic assessment, and which will one day contribute to more effective treatments and improved patient outcomes.

Introduction

The myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) represent the most common class of acquired bone marrow failure syndromes in adults. Although MDSs are increasingly well understood from a biological standpoint, including discovery of >40 MDS-associated recurrently mutated genes in the last 7 years, improved pathological insight has not yet translated into highly effective or curative therapies for most patients suffering from these disorders.1,2

Collectively, the term MDS describes a diverse group of clonal disorders of hematopoietic stem or progenitor cells characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis, abnormal “dysplastic” cell morphology, and potential for clonal evolution.3 Increasing failure of cellular differentiation is associated with evolution to secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML), currently arbitrarily defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ≥20% myeloid blasts in the blood or marrow, or the presence of one of several AML-defining karyotypic abnormalities [eg, t(15;17), t(8;21), inv(16), or t(16;16)] regardless of blast proportion. AML is ultimately diagnosed in up to 30% of MDS cases.4,5

In this review, we describe recent advances in our collective understanding of the genetic basis of MDS in the context of existing knowledge and survey how these findings may contribute to improvements in diagnosis and prognostic assignment of patients, serve as predictors or biomarkers of response to treatment, and aid development of future therapies. MDS cell biology and immunobiology, animal models, the contribution of the marrow microenvironment to MDS development and persistence, and familial predisposition to MDS are also areas of active development but are beyond the scope of this review.

Epidemiology and diagnosis

Although MDS are common, the exact number of new cases in the United States each year has proven difficult to estimate accurately. This is in part because cancer registries such as the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry of the National Cancer Institute have only begun to classify MDS as neoplastic and capture data on MDS cases since 2001.6 Additionally, many elderly patients with mild unexplained cytopenias who may have MDS are incompletely evaluated, including avoidance of bone marrow aspiration, without which the diagnosis of MDS currently cannot be made with certainty.

Estimates of disease incidence derived from insurance claims data may more accurately approximate epidemiological truth. Yet many patients with indolent or low-grade MDS never have an MDS-labeled claim filed, whereas other patients who do not truly have MDS are sometimes coded as such to justify use of a specific therapy, such as an erythropoiesis stimulating agent (ESA). Taking these limitations into consideration, current estimates are that between 30 000 and 40 000 new cases of MDS occur in the United States each year, with perhaps twice as many cases in Europe; given the median survival of patients with MDS, the prevalence is likely to be 60 000 to 120 000 cases in the United States.7-9

Less is known about the incidence and prevalence of MDS in other global regions. In China and South Asia, patients with MDS are diagnosed at a younger age, some subtypes of MDS such as refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts are seen less frequently, and complex karyotypes and monosomy 7 may be more common than in the West; the reasons for these differences are unclear, but may relate to genetic background or environmental exposures.10,11 MDS epidemiology is also distinct in Japan and in Eastern Europe, including an increased MDS risk in survivors of the 1945 Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb explosions persisting into the 21st century.12-15

The diagnosis of MDS is typically made by excluding other non-MDS causes of cytopenias in the presence of some combination of dysplastic cell morphology, increased marrow blasts, and a karyotypic abnormality.16,17 Common “MDS mimics” include cytopenias or morphologic abnormalities as a result of a medication (eg, methotrexate); deficiencies of cobalamin, folate, or copper; excessive alcohol use; HIV infection; immune-mediated cytopenias, including aplastic anemia and large granular lymphocyte leukemia; congenital syndromes such as Fanconi anemia and X-linked sideroblastic anemia; and other neoplasms such as myeloproliferative neoplasms. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy allows assessment of both cell morphology and histological architecture, and, when coupled with conventional karyotyping (abnormal in approximately one-half of de novo MDS cases and >80% of cases arising secondary to exposure to a DNA-damaging agent), can in some cases confirm disease clonality. Morphologic dysplasia is not required for an MDS diagnosis in the presence of cytopenias if either excess blasts in the 5% to 19% range or evidence of clonally restricted hematopoiesis are present.

Cases in which cytopenias are present, but the karyotype is normal, dysplastic changes are mild or absent, and there is no increase in blasts or other features convincing for an MDS diagnosis, present diagnostic difficulty. Such patients are sometimes referred to as having idiopathic cytopenias of undetermined significance (ICUS), which in contrast to monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance is by definition not known to be clonal. ICUS is also not a unique or well-defined clinical entity and includes a heterogeneous group of patients, only some of whom have an MDS or AML progression risk.18 In addition to ICUS, some elderly people have clonally restricted hematopoiesis without cytopenias, sometimes detectable as somatic mosaicism for large chromosomal abnormalities, and the rate at which these patients progress to MDS or other hematologic neoplasms appears to be increased compared with patients without clonal hematopoiesis.19-21 The recent finding of 450 somatic mutations in the healthy blood compartment of a 115-year-old woman is a striking illustration that not all detectable coding mutations are clinically consequential.22

Current treatment approaches

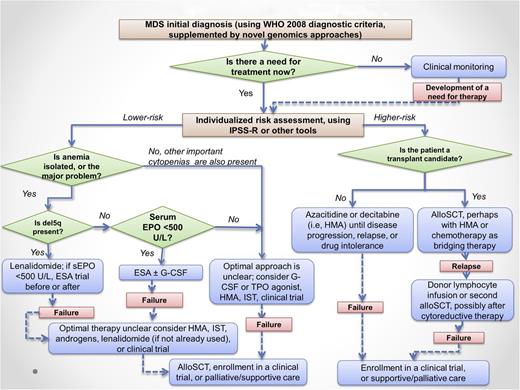

A therapeutic algorithm for MDS is outlined in Figure 1. This algorithm is largely consistent with published practice guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and, to a lesser extent, the more conservative guidelines of the European LeukemiaNet that reflect narrower regulatory approval of certain MDS drugs in Europe.23,24

MDS treatment algorithm. Not all patients with MDS require therapy; some can be safely observed with intermittent blood count monitoring for a period of time. Once therapy is justified by the presence of symptoms, severe cytopenias, or increasing blast proportion, prognostic risk assessment can aid in selection of lower-intensity therapies vs disease-modifying treatments, including allogeneic stem cell transplantation, which is the only potentially curative approach. Clinical trial enrollment is encouraged at all phases of disease. The level of evidence supporting the recommendations in this algorithm varies, with some approaches supported by a randomized prospective trial (eg, azacitidine in higher-risk MDS, lenalidomide in del5q MDS) and others supported only by phase 2 data (eg, iron chelation) or case series (eg, androgens). G-CSF, granulocyte colony stimulating factor; sEPO, serum EPO level; TSA, thrombopoietin receptor agonist (thrombopoiesis stimulating agent). Modified from Steensma and Stone.129

MDS treatment algorithm. Not all patients with MDS require therapy; some can be safely observed with intermittent blood count monitoring for a period of time. Once therapy is justified by the presence of symptoms, severe cytopenias, or increasing blast proportion, prognostic risk assessment can aid in selection of lower-intensity therapies vs disease-modifying treatments, including allogeneic stem cell transplantation, which is the only potentially curative approach. Clinical trial enrollment is encouraged at all phases of disease. The level of evidence supporting the recommendations in this algorithm varies, with some approaches supported by a randomized prospective trial (eg, azacitidine in higher-risk MDS, lenalidomide in del5q MDS) and others supported only by phase 2 data (eg, iron chelation) or case series (eg, androgens). G-CSF, granulocyte colony stimulating factor; sEPO, serum EPO level; TSA, thrombopoietin receptor agonist (thrombopoiesis stimulating agent). Modified from Steensma and Stone.129

The only potentially curative therapy for MDS remains allogeneic hematopoietic stem (progenitor) cell transplantation (HSCT), but <1000 patients per year with MDS in the United States currently undergo HSCT.25 Because the median age at MDS diagnosis is 71 years, and many stem cell transplant centers now perform reduced-intensity conditioning transplants in patients with good performance score well into the eighth decade of life, a much larger proportion of patients are potentially eligible for HSCT than actually receive it.26 Among those who do undergo HSCT for MDS, 30% to 40% are long-term disease-free survivors.25

Overall, although some patients do experience gratifying responses to drug therapy, non-HSCT treatment of MDS is disappointing, because complete response rates to currently available disease-modifying therapies are low and responses are often not durable. Lower-risk patients are typically treated with supportive care and low-intensity therapies: transfusions for severe anemia and thrombocytopenia, antimicrobial agents for suspected infections, ESAs (epoetin or darbepoetin) if the serum erythropoietin (EPO) level is <500 U/L, and, if deletion of the long arm of chromosome 5 is present, the immunomodulatory agent lenalidomide.27-30 Although infection is the most common cause of MDS-associated death, myeloid growth factors do not clearly modify disease history and may only increase production of functionally defective neutrophils lacking bactericidal capacity.31,32

There is increasing off-label use of the thrombopoietin agonists romiplostim and eltrombopag in MDS, despite the potential risk of these agents to augment myeloblast proliferation.33 Recent data from a placebo-controlled trial of romiplostim in lower-risk MDS are somewhat reassuring, as the rate of progression to AML was not increased with romiplostim therapy, whereas platelet transfusion needs and clinically significant bleeding events were reduced with active therapy.34 In the alloimmunized patient with severe thrombocytopenia in whom platelet transfusion is difficult, some investigators feel that a numeric increase in blasts may be an acceptable price for transfusion independence and decreased risk of bleeding.

A subset of lower-risk patients with MDS will respond to anti-T-cell therapy, but predicting responders to immunosuppressive therapy (IST) is particularly challenging, as described further below.35 The use of iron chelation in erythrocyte transfusion-requiring patients remains controversial, because retrospective and registry data suggest chelated patients may live longer than unchelated patients, yet there are no prospective randomized trial data demonstrating a morbidity or mortality benefit from chelation, and currently approved agents are inconvenient (deferroxamine) or costly and poorly tolerated by many patients (deferasirox).36,37

Patients with higher-risk MDS are typically treated with repeated cycles of one of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (hypomethylating agents) azacitidine or decitabine, and can proceed to HSCT if a donor is available and the patient is a suitable candidate.38,39 Azacitidine is the only agent to date that has been demonstrated to improve overall survival in the higher-risk MDS group compared with supportive care alone.40 Azacitidine and decitabine also see use in lower-risk MDS when other drugs have failed; such use is off-label in Europe, and the 2 drugs have not yet been directly compared in clinical trials. Overall, however, responses in unselected patients with MDS to various treatment options are poor, and both new therapeutic options and insights from genetic studies to better inform treatment choices are desperately needed.

Advances in the genetic basis of MDS

Despite continued use of confusing or misleading terminology such as “refractory anemia,” MDSs have been recognized as clonal neoplasms for >40 years—a biological reality reflected in their propensity for AML transformation and association with acquired chromosomal abnormalities, especially numerical abnormalities (aneuploidy) and segmental deletions.41,42 MDS cases with normal marrow karyotypes were long presumed to have underlying genetic abnormalities, and genetic studies conducted between 1987 and 2005 identified mutations in TP53, NRAS, and RUNX1.43-46 As of 2007, these genes were the most frequently mutated of the tiny number of known MDS-associated genes, but they were wild type in the majority of patients.

Since 2007, the application of novel sequencing techniques has led to discovery of dozens of recurrently mutated genes in MDS. One or more such mutations can be found in almost all cases, and knowing the nature of the genes involved has improved our understanding of how MDS develop and evolve, even if it has not yet had an impact on treatment.1,47-50

Chromosomal abnormalities are both diagnostically and prognostically useful and, in the case of chromosome 5q deletions (del[5q]), predict favorable response to treatment with lenalidomide.51-53 In fact, patients with del(5q) as a sole abnormality are classified separately by the WHO and often share clinical features first recognized in 1974 and later known as the “5q-syndrome”: dyserythropoiesis and erythroid hypoplasia, normal or increased platelet counts, and (if distal and proximal regions of chromosome 5q outside of the commonly deleted region are retained) a lower risk of AML progression compared with other MDS subtypes.42,54

Initially it was presumed that a tumor suppressor gene on the remaining, undeleted chromosome 5q would carry a point mutation, thus fulfilling Knudson’s 2-hit hypothesis, but extensive sequencing of genes located in the commonly deleted region (CDR) of chromosome 5q failed to identify recurrent mutations. Instead, haploinsufficiency of ≥1 gene in the CDR appears to be responsible for disease pathology. Systematic knockdown of each gene in the CDR led Ebert et al to identify haploinsufficiency of the ribosomal subunit-encoding gene RPS14 as a cause of severe dyserythropoiesis.55 Subsequently, several more 5q-CDR-encoded genes including microRNAs miR145 and miR146a have been implicated in the pathogenesis and clinical presentation of MDS.56-59 Unfortunately, investigation of genes in the MDS-associated CDRs of chromosomes 20q and 7q have been less conclusive, and the pathogenic mechanisms associated with these and other recurring chromosomal abnormalities remain unknown.

High-resolution genome-wide techniques, such as single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping arrays and comparative genome hybridization, can detect occult chromosomal abnormalities in many normal karyotype cases. Chromosomal microdeletions and areas of copy number-neutral loss of heterozygosity, also known as acquired uniparental disomy (aUPD), have helped identify individual genes important to the pathogenesis of MDS. For example, the recurrence of aUPD in chromosomal region 4q24 was explained in 2009 when a patient was found to have a microdeletion limited to the TET2 gene in that area.60 Targeted sequencing subsequently identified TET2 point mutations in >20% of patients with MDS. Likewise, recurrent aUPD and microdeletion of chromosome 7q led to the discovery of EZH2 mutations in 2010.61,62 A similar approach using array comparative genome hybridization led to the discovery of frequent ASXL1 mutations in patients with MDS and other myeloid neoplasms.63

At around the same time as TET2 mutations were discovered in myeloid neoplasms, TET family genes were found to encode methylcytosine oxidases.64,65 This discovery identified TET2 as a regulator of DNA methylation. ASXL1 and EZH2 mutations are now known to affect histone modifications, and collectively, mutations in these genes as well as several others discovered later indicate that epigenetic dysregulation and altered gene expression is a major driver in the pathogenesis of MDS.

The first complete cancer genome to be sequenced (in 2009) was that of an AML patient who was found to carry a mutation of IDH1, encoding the citric acid cycle enzyme isocitrate dehydrogenase 1.66 Mutations of IDH1 and IDH2 had previously been detected in gliomas but had not been suspected in hematologic malignancies.67 Targeted IDH1/2 sequencing in AML and MDS identified recurring mutations in these genes, and later work identified how IDH mutations change the function of these metabolic enzymes. Briefly, heterozygous hotspot mutations in these genes alter the reaction catalyzed by their encoded enzymes such that α-ketoglutarate (αKG) is converted to 2-hydroxyglutarate (2HG).68,69 As an oncometabolite, 2HG is transforming and inhibits the function of αKG-dependent enzymes such as TET family members, histone demethylases, and prolyl hydroxylases.70 Mutations of IDH genes and TET2 appear to be largely exclusive of each other in AML and MDS, suggesting that they engage similar oncogenic mechanisms of epigenetic dysregulation.49,50,71 Reanalysis of the original AML genome identified a mutation in another epigenetic regulator, the DNA methyl-transferase gene DNMT3A.72 DNMT3A is mutated in ∼12% of MDS patients, and this discovery solidified the epigenetic basis of myeloid neoplasms.

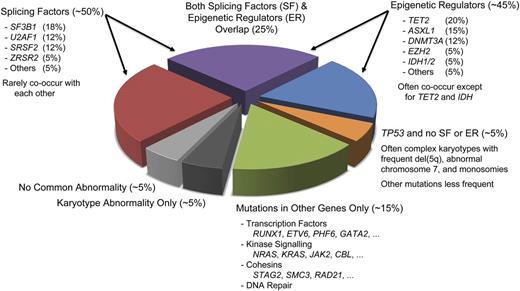

Whole genome sequencing applied to MDS patient samples subsequently identified an entirely novel class of cancer associated genes encoding mRNA splicing factors. The first such gene identified in MDS was SF3B1, which is particularly frequently mutated (>70% of cases) in patients with refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts.73 SF3B1 is also recurrently mutated in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and at lower frequencies in various solid tumors.74,75 Discovery of mutations in many other splicing factors such as SRSF2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2 quickly followed. These were noted to be largely exclusive of each other, suggesting a common mechanism of action.76,77 As a group, splicing factor mutations can be identified in >50% of MDS patients (Figure 2), making them the most frequently mutated class of genes in these disorders. How splicing factor dysregulation drives the pathogenesis and progression of MDS remains incompletely understood.

Distribution of recurrent mutations and karyotypic abnormalities in MDS. Clonal cells from ∼50% of MDS patients harbor a splicing factor (SF) mutation, and a similar fraction carry ≥1 mutated epigenetic regulator (ER). Approximately 25% of patients have mutations of genes in both groups. Patients with TP53 mutations often have fewer cooperating mutations and instead have a high rate of chromosomal abnormalities, including frequent complex karyotypes. Many other genes can be comutated with SF and ER genes, but such mutations also occur in the absence of SF or ER lesions in ∼15% of patients. Only approximately 10% of patients lack mutations in any of the common recurrently mutated genes. Fractions estimated from data in Bejar et al, Papaemmanuil et al, and Haferlach et al.47-50

Distribution of recurrent mutations and karyotypic abnormalities in MDS. Clonal cells from ∼50% of MDS patients harbor a splicing factor (SF) mutation, and a similar fraction carry ≥1 mutated epigenetic regulator (ER). Approximately 25% of patients have mutations of genes in both groups. Patients with TP53 mutations often have fewer cooperating mutations and instead have a high rate of chromosomal abnormalities, including frequent complex karyotypes. Many other genes can be comutated with SF and ER genes, but such mutations also occur in the absence of SF or ER lesions in ∼15% of patients. Only approximately 10% of patients lack mutations in any of the common recurrently mutated genes. Fractions estimated from data in Bejar et al, Papaemmanuil et al, and Haferlach et al.47-50

In a brief period, whole genome approaches completely redefined the landscape of mutations in MDS. These techniques identified epigenetic regulation and RNA splicing as the predominant disturbed molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of MDS. The quantitative nature of these techniques also provided insight into the clonal architecture of these neoplasms. Sequencing of secondary AML (sAML) genomes in patients with preceding MDS identified one or more expanded subclones in nearly all cases.5 The recurrent driver mutations that defined these AML subclones could often be found in a much smaller fraction of disease cells at a time point prior to AML development. This is proof that clonal evolution and molecular heterogeneity are hallmarks of MDS and may be important predictors of disease progression.78

Improvements to the diagnosis and classification of MDS

Advances in molecular understanding of MDS are poised to become part of routine clinical care of patients. A precedent for this can be seen in the myeloproliferative neoplasms, where detection of BCR-ABL rearrangements are critical for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) diagnosis and treatment monitoring, and discovery of JAK2 mutations quickly led to incorporation of mutation testing into diagnostic criteria for polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis.4 The greater molecular heterogeneity of MDS compared with CML or PV makes clinical translation of mutation analysis a more challenging prospect, but a challenge that is being addressed.

For example, establishing a diagnosis of MDS currently relies on a morphologist’s qualitative assessment of dysplasia and quantification of blast forms that may be highly distorted.79 Even experienced pathologists frequently have interobserver variability.66,67 Furthermore, hematopoietic cell dysplasia is not specific for MDS, and karyotypic abnormalities that can confirm an MDS diagnosis are not present in most cases.16,17,80,81 All of these factors can contribute to uncertainty or error in diagnosis.

Targeted gene sequencing and SNP array analysis can identify somatic events in the majority of MDS patients, including many with normal karyotypes or more indolent disease, and can conclusively establish the presence of clonal hematopoiesis.49,50,82,83 Recently, it has been shown that ≥1 mutation typical for MDS can be found in nearly one-half of patients with suspected MDS who do not meet morphologic diagnostic criteria.84 Whether ICUS patients with somatic mutations will have a disease course comparable to that of more overt MDS cases is not yet known, but identification of clonal hematopoiesis can help rule out competing benign causes of cytopenias and suggests that close follow up for disease progression is warranted.

Not all somatic mutations will be of equal value diagnostically. Acquired mutations of certain genes, like TET2 and DNMT3A, can be found in patients with diagnoses other than MDS, including lymphoid disorders.71,85 Mutations of these genes can also be identified in some healthy persons without cytopenias.86,87 Mutations of genes strongly associated with clinical phenotypes will have the greatest diagnostic utility and may help better classify MDS subtypes. For example, splicing factor mutations are enriched in patients with dysplasia compared with nondysplastic myeloid disorders. In particular, SF3B1 mutations are strongly associated with ring sideroblasts, and patients with SF3B1 mutations harbor fewer mutations in genes associated with a poor prognosis and generally have a more indolent disease course.47,49,50

Mutations of TP53, although not associated with a specific morphology or clinical phenotype, are associated with adverse disease features including excess blasts, thrombocytopenia, and complex karyotypes (ie, ≥3 chromosomal abnormalities) and fewer cooperating lesions in recurrently mutated genes.48,88,89 In contrast, patients with complex karyotypes without TP53 mutations appear to have an overall survival comparable to that of patients without multiple karyotype abnormalities.48 In the del(5q) setting, TP53 mutations or p53 protein expression in marrow cells predict less frequent cytogenetic responses to lenalidomide and higher AML progression rate.90,91 In this case, the presence or absence of a molecular lesion may help classify patients and refine prognosis predicted by karyotyping.

Improvements to the prediction of prognosis in MDS

Estimating the prognosis of patients with MDS is an integral part of clinical care, setting expectations for patients and informing treatment decisions for clinicians. The most widely used tool for the prediction of MDS disease risk has been the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS), first published in 1997.92 This simple-to-apply model was used to characterize patient populations in clinical trials and to define consensus treatment guidelines for MDS.93 Although it represented the clinical standard for MDS risk assessment, the IPSS had several deficiencies, including an underestimation of risk in some patients without excess blasts or abnormal karyotypes. This prompted the development of complementary risk models including the WHO Classification-based Prognostic Scoring System, the MD Anderson Comprehensive Scoring System, and the MD Anderson Lower Risk MDS model.94-96

In 2012, the IPSS was revised (IPSS-R) to address several limitations of its predecessor.51 First, the IPSS-R expands the number of chromosomal abnormalities explicitly considered by the model and gives greater weight to adverse cytogenetic lesions than to excess blasts.97 Second, bone marrow blast proportion risk group cutoffs are revised from the IPSS. Third, cytopenias are treated individually and weighted based on severity. Finally, a more explicit method for considering patient age is included in the IPSS-R model. These changes add complexity compared with the IPSS, but no new clinical information is needed to calculate the IPSS-R score, which can be done with the help of an online tool (www.ipss-r.com).

As with the IPSS, the IPSS-R is based on an analysis of MDS patients evaluated at the time of diagnosis and censored if they received disease modifying therapy, and excludes patients with therapy-related disease or proliferative CMML. Despite these limitations, the IPSS-R has since been validated in several contexts, including after treatment.98-100

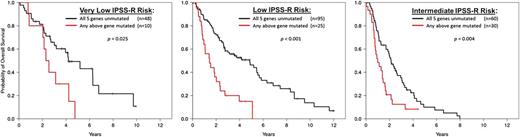

The IPSS-R does not include molecular abnormalities. Cryptic chromosomal lesions detected by SNP arrays and somatic mutations in MDS driver genes (especially TP53, ASXL1, DNMT3A, EZH2, and RUNX1, all of which are associated with poorer outcomes) have both been shown to add independent prognostic information (Figure 3).47,48 The number of recurrently mutated genes is greater in more advanced MDS subtypes, and acquisition of certain mutations is associated with transformation to AML. Given the often tight association between molecular lesions and disease phenotypes, combining mutation information with clinical features provides only a small improvement in prognostic accuracy.49,50 However, genetic information may be more sensitive. The presence of adverse mutations in small subclones can have the same prognostic importance as if found in a major clone, yet might be detected earlier.49,101 Mutations considered in specific clinical contexts, such as TP53 mutation status in complex karyotype or del(5q) patients, may also have greater predictive power than currently obtained information.

Somatic mutation in any of the 5 genes (TP53, EZH2, RUNX1, ASLX1, or ETV6) shown in Bejar et al48 to have prognostic significance independent of the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) identifies patients from that same cohort with shorter overall survival than predicted by Revised IPSS (IPSS-R) for the 3 lowest IPSS-R risk groups. One-third of patients in the IPSS-R Intermediate risk group have shorter than predicted overall survival and may better categorized using mutation analysis as having higher risk disease. Modified from Bejar127 and used with permission.

Somatic mutation in any of the 5 genes (TP53, EZH2, RUNX1, ASLX1, or ETV6) shown in Bejar et al48 to have prognostic significance independent of the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) identifies patients from that same cohort with shorter overall survival than predicted by Revised IPSS (IPSS-R) for the 3 lowest IPSS-R risk groups. One-third of patients in the IPSS-R Intermediate risk group have shorter than predicted overall survival and may better categorized using mutation analysis as having higher risk disease. Modified from Bejar127 and used with permission.

Predictors and markers of response to therapy

In contrast to some other hematological neoplasms where biomarkers strongly influence treatment choices, the clinical predictors of response to therapeutic agents in patients with MDS are limited. Only the serum EPO level and the presence of del(5q) are useful biomarkers to help choose whether or not to use a specific agent. In a patient who has a serum EPO level >500 U/L and is requiring ≥2 units of red blood cells per month, the response rate to epoetin alfa or darbepoetin alfa is <10%, whereas in a patient with serum EPO level <100 U/L who is requiring blood products infrequently, the response rate to an ESA may exceed 70% (“response” here is defined as increment in hemoglobin by ≥1.5 g/dL in the absence of transfusion).102 Red cell transfusion-requiring patients who have lower-risk MDS and del(5q) have a transfusion independence rate during lenalidomide therapy of nearly 70%, and such responses last a median of >2 years, whereas patients who lack del(5q) respond to lenalidomide only ∼25% of the time, and the median duration of response is <1 year.53,103 Patients who have excess blasts, especially those with a platelet count <100 × 109/L, only rarely respond to lenalidomide meaningfully or durably, even if del(5q) is present.104

Consistent clinical predictors of response to azacitidine and decitabine have been harder to come by, as have predictors of response to IST with anti-T-cell drugs such as ATG and cyclosporine.35 No specific chromosome or molecular marker has consistently predicted response to hypomethylating agents. A modest increase in response rates in patients with TET2 or DNMT3A mutations has been observed, but is of little clinical relevance because their predictive value is insufficient to alter treatment decisions.105,106 It is perhaps surprising that the numerous somatic mutations that affect chromatin remodeling or alter epigenetic patterns do not consistently predict response to hypomethylating agents in MDS, given the effects of such agents on DNA methylation and gene expression, but the precise mechanism of action of hypomethylating agents, including the extent to which they retain conventional cytotoxic activity or instead have immunomodulatory107 or other activity, is still unclear. It is also possible that differences in pharmacokinetics or other nongenetic factors play a large role in treatment response to these agents, and such variability may obscure a signal from genetic response predictors.

With respect to IST, high response rates have been reported in series of patients treated with anti-thymocyte globulin-based therapies or with alemtuzumab at the US National Institutes of Health, but patients enrolled in such trials have generally been younger and have had a higher frequency of normal karyotypes than patients with MDS as a whole, limiting the generalizability of those results.108 Factors that have been reported to predict a higher response to IST include the presence of a paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria clone, HLA DR15 allele, normal karyotype or trisomy 8, younger age (especially <55 years), and lack of transfusion dependence.109 Most recently, STAT3 mutations, which are associated with large granular lymphocyte leukemia, have been detected in some patients with MDS and may be associated with an increased likelihood of response to IST.110 Patients with complex karyotypes or monosomy 7, and those with excess blasts, rarely respond to IST. Interestingly, although 10% to 15% of patients with MDS have a hypocellular marrow for age, and this would suggest a pathophysiology more akin to aplastic anemia and therefore more likely to respond to IST, a hypocellular marrow has predicted response to IST in some series but not in others.111-113

Emerging data suggest that presence of a TP53 mutation predicts a high likelihood of disease relapse and death after HSCT. In addition, patients who go into HSCT with excess blasts (>10%) also have a high risk of relapse, especially with reduced intensity conditioning.114 In other disease settings such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia, measurement of minimal residual disease (MRD) by flow cytometry or molecular testing has proven useful to guide decisions about immunological manipulation with donor lymphocyte infusion or other approaches following HSCT. At present, however, measurement of MRD in patients with MDS is not routinely undertaken except in the case of post-transplant chimerism assessment,115 although technically feasible. Given recent advances in understanding MDS-associated flow cytometry patterns and a greater appreciation of the repertoire of somatic mutations associated with MDS, MRD monitoring after HSCT and drug therapy may eventually become routine in MDS clinical practice.115

Advances in MDS therapy

There have been no new drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for MDS therapy since 2006, and currently available therapies will fail the majority of patients within 2 to 3 years after treatment initiation even if there is initial favorable response. Therefore, new effective agents are greatly needed. One of the challenges of developing such therapies, however, is that targetable constitutively activating kinase mutations are rare in MDS; for many of the new described mutations outlined above, such as those that effect pre-mRNA splicing or transcriptional regulation, it is not immediately obvious how to develop a targeted therapy. This is not just true for MDS: even for mutations that have been well described in various types of cancer for decades, such as mutations in TP53, Ras family members, or MYC, there are as of yet no FDA-approved targeted therapies, although several are in development.

In addition, the clonal heterogeneity and complexity of the clonal architecture of MDS presents a challenge, as it is often not known which mutations are early initiating events and which are later events of consequence only for a subclone.116 Finally, in many patients with MDS, there may be a paucity of healthy hematopoietic stem cells to replace disease clones once the latter have been eliminated, so that successful cytoreduction of clonal MDS cells results in prolonged, severe cytopenias. Just as the human aging process is not yet reversible, cumulative damage to marrow hematopoietic elements across the span of an 8- or 9-decade human lifespan may not be repairable without innovations in stem cell therapy.

Despite such concerns, investigators are currently testing a variety of approaches to try to improve on current MDS therapeutics (Table 1). One such approach is the use of combination therapies that have either additive or synergistic effects in vitro.117 Combinations of azacitidine with lenalidomide, and azacitidine with vorinostat (a deacetylase inhibitor currently FDA approved for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), offer the possibility of higher rates of response than are associated with either agent alone.118,119 Whether these combinations will improve outcomes for patients compared with azacitidine monotherapy is currently being explored in a cooperative group trial in the United States and Canada (S1117) and a similar multicenter European trial (AZA-PLUS).

Agents in development for MDS in clinical trials that are actively recruiting patients

| Agent (synonyms) . | Putative mechanism . |

|---|---|

| Kinase inhibitors | |

| INCB047986 | Janus-associated kinase (JAK) inhibitor |

| KB004 | Antibody against ephrin A3 (EphA3) receptor tyrosine kinase |

| LGH447 | Pim kinase inhibitor |

| MEK 162 | Inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases 1 and 2 (MEK1/2) |

| Midostaurin (PKC412) | Protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor |

| PD-616 (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate) | Protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor |

| Quizartinib (AC220) | Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) inhibitor |

| Rigosertib (SyB C-1101, SyB L-1101, ON 01910.Na) | Phosphoinositide-3 (PI3) kinase inhibitor, Polo-like kinase pathway inhibitor |

| Ruxolitinib (INCB18424) | Janus-associated kinase (JAK) inhibitor |

| Sorafenib | Inhibition of Raf, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) and other kinases |

| Volasertib (BI 6727) | Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) inhibitor |

| ziv-Aflibercept | Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor |

| Deacetylase inhibitors and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors | |

| Oral azacitidine (CC-486) | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor |

| Oral decitabine and E7727 (ASTX727) | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor combined with cytidine deaminase inhibitor |

| SGI-110 | Nucleoside analog with DNA methyltransferase inhibitory activity |

| Mocetinostat (MGCD0103) | Deacetylase inhibitor |

| Panobinostat (LBH-589) | Deacetylase inhibitor |

| Pracinostat (SB939) | Deacetylase inhibitor |

| Vorinostat (suberanilohydroxamic acid, SAHA) | Deacetylase inhibitor |

| Altered cell metabolism | |

| AG-120, AG-221 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 (IDH1 and IDH2) inhibitors |

| Coenzyme Q10 and l-carnitine | Alteration of intracellular metabolism and electron transport chain |

| CPI613 | Inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase and ketoglutarate dehydrogenase |

| INCB024360 | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1) inhibitor |

| Cytotoxic agents/cell cycle inhibitors | |

| Cladribine (2-CDA) | Nucleoside analog |

| Clofarabine | Nucleoside analog; resists deamination and phosphorolysis |

| CPX-351 | Liposomal daunorubicin and cytarabine in a fixed 1:5 ratio |

| Lurbinectidin (PM01183) | Synthetic tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloid DNA minor groove covalent binder |

| Vosaroxin (SNS-595) | Quinolone derivative; replication-dependent DNA damage agent |

| Immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive agents | |

| ALT-803 | Interleukin (IL)-15 superagonist mutant and a dimeric IL-15 receptor αSu/Fc fusion protein |

| DEC-205/NY-ESO-1 fusion protein CDX-1401 | Immunostimulator (DEC=endocytic dendritic cell receptor; NY-ESO-1 is a tumor associated antigen) |

| Equine antithymocyte globulin | T cell inhibition by polyclonal antibodies raised in animals |

| Ipilimumab (MDX-101) | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor |

| MK-3475 | Anti-programmed death 1 (PD1) antibody |

| Pomalidomide (CC4047) | Immunomodulatory agent with diverse activities; modulation of cereblon E3 ubiquitin ligase activity |

| Sirolimus | Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor |

| Temsirolimus | Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor |

| Apoptosis modulation | |

| ACE-536 | Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily ligand trap |

| APG101 | CD95-Fc fusion protein (inhibits Fas signaling) |

| Birinapant (TL32711) | Peptidomimetic of second mitochondrial-derived activator of caspases (SMAC) and inhibitor of inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) family proteins |

| LY2157299 | Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) receptor I (TβRI) inhibitor |

| Sotatercept (ACE-011) | Soluble fusion protein: extracellular domain of activin receptor type IIA (ActRIIA) linked to the Fc protein of human IgG1; transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) pathway inhibitor |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Bortezomib | Proteasome inhibition |

| Brentuximab vedotin | Antibody against CD30 conjugated to a cytotoxin |

| CLT-008 | Human myeloid progenitor cells |

| CWP232291 | Inhibits Src associated in mitosis of 68 kDa (Sam68) protein |

| E7070 | Synthetic sulfonamide cell cycle inhibitor |

| Eltrombopag | Small molecule agonist of thrombopoietin receptor c-Mpl (i.e., thrombopoiesis stimulating agent) |

| Ganetespib (STA-9090) | Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) inhibitor |

| GSK525762 | Bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) family inhibitor |

| Omacetaxine (homoharringtonine) | Protein translation inhibition |

| OXi4503 (combretastatin A1 diphosphate / CA1P) | Vascular disrupting agent |

| PF-04449913 | Hedgehog pathway inhibitor |

| Plerixafor (AMD3100) | Inhibition of C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) |

| PRI-724 | Modulator of Wnt signaling that inhibits the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) binding protein and β-catenin interaction |

| Vismodegib (GDC-0449) | Antagonist of smoothened receptor (SMO) in Hedgehog pathway |

| Agent (synonyms) . | Putative mechanism . |

|---|---|

| Kinase inhibitors | |

| INCB047986 | Janus-associated kinase (JAK) inhibitor |

| KB004 | Antibody against ephrin A3 (EphA3) receptor tyrosine kinase |

| LGH447 | Pim kinase inhibitor |

| MEK 162 | Inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases 1 and 2 (MEK1/2) |

| Midostaurin (PKC412) | Protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor |

| PD-616 (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate) | Protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor |

| Quizartinib (AC220) | Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) inhibitor |

| Rigosertib (SyB C-1101, SyB L-1101, ON 01910.Na) | Phosphoinositide-3 (PI3) kinase inhibitor, Polo-like kinase pathway inhibitor |

| Ruxolitinib (INCB18424) | Janus-associated kinase (JAK) inhibitor |

| Sorafenib | Inhibition of Raf, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) and other kinases |

| Volasertib (BI 6727) | Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) inhibitor |

| ziv-Aflibercept | Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor |

| Deacetylase inhibitors and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors | |

| Oral azacitidine (CC-486) | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor |

| Oral decitabine and E7727 (ASTX727) | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor combined with cytidine deaminase inhibitor |

| SGI-110 | Nucleoside analog with DNA methyltransferase inhibitory activity |

| Mocetinostat (MGCD0103) | Deacetylase inhibitor |

| Panobinostat (LBH-589) | Deacetylase inhibitor |

| Pracinostat (SB939) | Deacetylase inhibitor |

| Vorinostat (suberanilohydroxamic acid, SAHA) | Deacetylase inhibitor |

| Altered cell metabolism | |

| AG-120, AG-221 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 (IDH1 and IDH2) inhibitors |

| Coenzyme Q10 and l-carnitine | Alteration of intracellular metabolism and electron transport chain |

| CPI613 | Inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase and ketoglutarate dehydrogenase |

| INCB024360 | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1) inhibitor |

| Cytotoxic agents/cell cycle inhibitors | |

| Cladribine (2-CDA) | Nucleoside analog |

| Clofarabine | Nucleoside analog; resists deamination and phosphorolysis |

| CPX-351 | Liposomal daunorubicin and cytarabine in a fixed 1:5 ratio |

| Lurbinectidin (PM01183) | Synthetic tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloid DNA minor groove covalent binder |

| Vosaroxin (SNS-595) | Quinolone derivative; replication-dependent DNA damage agent |

| Immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive agents | |

| ALT-803 | Interleukin (IL)-15 superagonist mutant and a dimeric IL-15 receptor αSu/Fc fusion protein |

| DEC-205/NY-ESO-1 fusion protein CDX-1401 | Immunostimulator (DEC=endocytic dendritic cell receptor; NY-ESO-1 is a tumor associated antigen) |

| Equine antithymocyte globulin | T cell inhibition by polyclonal antibodies raised in animals |

| Ipilimumab (MDX-101) | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor |

| MK-3475 | Anti-programmed death 1 (PD1) antibody |

| Pomalidomide (CC4047) | Immunomodulatory agent with diverse activities; modulation of cereblon E3 ubiquitin ligase activity |

| Sirolimus | Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor |

| Temsirolimus | Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor |

| Apoptosis modulation | |

| ACE-536 | Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily ligand trap |

| APG101 | CD95-Fc fusion protein (inhibits Fas signaling) |

| Birinapant (TL32711) | Peptidomimetic of second mitochondrial-derived activator of caspases (SMAC) and inhibitor of inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) family proteins |

| LY2157299 | Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) receptor I (TβRI) inhibitor |

| Sotatercept (ACE-011) | Soluble fusion protein: extracellular domain of activin receptor type IIA (ActRIIA) linked to the Fc protein of human IgG1; transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) pathway inhibitor |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Bortezomib | Proteasome inhibition |

| Brentuximab vedotin | Antibody against CD30 conjugated to a cytotoxin |

| CLT-008 | Human myeloid progenitor cells |

| CWP232291 | Inhibits Src associated in mitosis of 68 kDa (Sam68) protein |

| E7070 | Synthetic sulfonamide cell cycle inhibitor |

| Eltrombopag | Small molecule agonist of thrombopoietin receptor c-Mpl (i.e., thrombopoiesis stimulating agent) |

| Ganetespib (STA-9090) | Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) inhibitor |

| GSK525762 | Bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) family inhibitor |

| Omacetaxine (homoharringtonine) | Protein translation inhibition |

| OXi4503 (combretastatin A1 diphosphate / CA1P) | Vascular disrupting agent |

| PF-04449913 | Hedgehog pathway inhibitor |

| Plerixafor (AMD3100) | Inhibition of C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) |

| PRI-724 | Modulator of Wnt signaling that inhibits the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) binding protein and β-catenin interaction |

| Vismodegib (GDC-0449) | Antagonist of smoothened receptor (SMO) in Hedgehog pathway |

Inclusion in this table is based on review of clinicaltrials.gov website April 16, 2014, with search term “myelodysplastic syndrome,” restricted to “Open” trials. Agents are included if (1) the study in which they were being tested had been updated or verified since January 1, 2012, and was either in “Recruiting” or “Not Yet Recruiting” status and were excluded if they were “Completed,” “Unknown,” or “Terminated”; (2) they do not involve a drug already FDA approved for MDS (lenalidomide, azacitidine, and decitabine), AML, or for an iron chelation indication; (3) they are not for stem cell transplant conditioning, cellular product manipulation, graft versus host prevention or treatment, or a vaccine. Many trials of these agents, especially early phase studies, were also enrolling patients with AML or other hematological malignancies.

Several other deacetylase inhibitors beside vorinostat are being tested in combination with azacitidine or decitabine. These include pracinostat (SB939), panobinostat (LBH589), mocetinostat (MGCD0103), and others. A recently published North American cooperative group study, E1905, offers a cautionary tale: the deacetylase inhibitor entinostat (MS275) did not improve outcomes when added to azacitidine in higher-risk MDS and AML, but did increase adverse events compared with azacitidine monotherapy.120

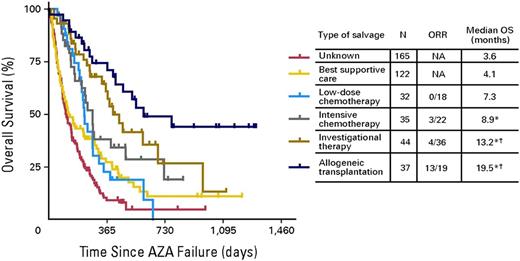

In higher-risk patients whom azacitidine or decitabine has failed, overall life expectancy is <6 months (Figure 4), and new approaches are needed.121 SGI110, a novel hypomethylating agent that is a dinucleotide of decitabine linked to guanosine to increase resistance to degradation by cytidine deaminase, has demonstrated activity in this subgroup. Several drugs being developed for AML, including the nucleoside analog sapacitabine, the quinolone derivative vosaroxin, and inhibitors of Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK-1) such as volasertib are also being studied in higher-risk MDS after azacitidine or decitabine failure.

Patients with MDS for whom hypomethylating agents have failed have poor outcomes overall. This figure shows Kaplan-Meier survival analysis according to subsequent post-hypomethylating agent salvage regimen. A small subset of patients who are younger or have a better performance score and are eligible for a clinical trials or stem cell transplantation have a survival exceeding 1 year, but most patients receive only supportive/palliative care and live <6 months. Recent data suggest that patients who still have lower-risk disease but have not responded to azacitidine or decitabine have a have a median survival of ∼15 months.128 AZA, azacitidine; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival. Original figure copyright American Society of Clinical Oncology121 ; used with permission.

Patients with MDS for whom hypomethylating agents have failed have poor outcomes overall. This figure shows Kaplan-Meier survival analysis according to subsequent post-hypomethylating agent salvage regimen. A small subset of patients who are younger or have a better performance score and are eligible for a clinical trials or stem cell transplantation have a survival exceeding 1 year, but most patients receive only supportive/palliative care and live <6 months. Recent data suggest that patients who still have lower-risk disease but have not responded to azacitidine or decitabine have a have a median survival of ∼15 months.128 AZA, azacitidine; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival. Original figure copyright American Society of Clinical Oncology121 ; used with permission.

A recent large randomized trial of the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase kinase/PLK-1 inhibitor rigosertib in higher-risk patients for whom azacitidine or decitabine had failed did not show an overall survival benefit of rigosertib compared with control groups.122 The median survival for the rigosertib arm was 8.2 months compared with 5.8 months for the control arm, which was not a statistically significant difference. An oral formulation of rigosertib is being studied in lower-risk patients.123

A number of other novel agents are also in development for patients with lower-risk MDS, where a primary therapeutic goal is to improve hematopoiesis and reduce transfusion needs. For example, sotatercept, a soluble activin receptor type 2A IgG-Fc fusion protein that acts as a ligand trap for members of the transforming growth factor β superfamily, is undergoing a multicenter trial in MDS, as is the JAK1 inhibitor INCB047986.124 ARRY-614, a dual p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/Tie2 kinase inhibitor, has been associated with hematologic improvements in patients for whom hypomethylating agents have failed yet who still meet IPSS criteria for lower-risk disease; a few other kinase inhibitors are also being studied despite the relative rarity of activating kinase mutations in MDS.125

Finally, advances in HSCT may make this potentially curative approach available to a wider variety of patients and improve outcomes. Greater use of cord blood or haploidentical donors, use of novel reduced-intensity conditioning approaches in older patients and those with comorbidities, and graft manipulation with post-HSCT azacitidine or with specific immunotherapies all may increase the rate of HSCT use. Numerous important questions about optimal approaches to pretransplant therapy, donor selection, conditioning regimen, and post-transplant therapy to prevent relapse remain unanswered. Modulation of the PD1/PDL1 interaction that mediates immune tolerance of neoplastic cells is an area of current excitement, with multiple companies exploring anti-PD1/PDL1 antibodies in patients with MDS. Perhaps more important is education of patients and physicians, many of whom in a recent survey seemed unaware of the potential for HSCT to cure patients with MDS.126 The current number of patients undergoing SCT in the United States is only a small fraction of those who are potential candidates for the procedure, as many patients lack a donor, choose not to undergo HSCT because of concerns about changes in quality of life or fear of adverse events, or are never referred to a center where HSCT can be performed.

Conclusion

This is a particularly exciting time for MDS biological research, but laboratory advances are only just beginning to be translated into clinical improvements. In addition to the availability of molecular tests to help secure a diagnosis in difficult cases, a better prognostic tool inclusive of mutation status, the Revised IPSS Incorporating Molecular Data (IPSS-RM), is currently being developed. Perhaps more importantly, identification of novel targets for therapy that will help individualize treatment based on disease genotypes is a high priority. However, it seems likely that until a better method is found both to suppress abnormal clones and replace or expand normal hematopoietic elements in elderly patients who have undergone global stem cell attrition from both the effects of aging and disease, MDS will continue to frustrate patients and clinicians alike.

Acknowledgment

The authors apologize to investigators whose work could not be cited due to limitations in the length of the review and number of permitted references.

Authorship

Contribution: D.P.S. and R.B. wrote the paper collaboratively.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.P.S. is a member of Data Safety Monitoring Committees for Amgen and Novartis and has received consulting fees from Astex, Celgene, and Opsona within the last 12 months. R.B. has technology licensed to Genoptix and has received consulting fees from Genoptix.

Correspondence: David P. Steensma, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215-5450; e-mail: david_steensma@dfci.harvard.edu.