Key Points

NETs are present and pathogenic in sickle cell disease.

Plasma heme and proinflammatory cytokines collaborate to activate release of NETs.

Abstract

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is characterized by recurring episodes of vascular occlusion in which neutrophil activation plays a major role. The disease is associated with chronic hemolysis with elevated cell-free hemoglobin and heme. The ensuing depletion of heme scavenger proteins leads to nonspecific heme uptake and heme-catalyzed generation of reactive oxygen species. Here, we have identified a novel role for heme in the induction of neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation in SCD. NETs are decondensed chromatin decorated by granular enzymes and are released by activated neutrophils. In humanized SCD mice, we have detected NETs in the lungs and soluble NET components in plasma. The presence of NETs was associated with hypothermia and death of these mice, which could be prevented and delayed, respectively, by dismantling NETs with DNase I treatment. We have identified heme as the plasma factor that stimulates neutrophils to release NETs in vitro and in vivo. Increasing or decreasing plasma heme concentrations can induce or prevent, respectively, in vivo NET formation, indicating that heme plays a crucial role in stimulating NET release in SCD. Our results thus suggest that NETs significantly contribute to SCD pathogenesis and can serve as a therapeutic target for treating SCD.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD), an inherited autosomal recessive disorder, results from a single amino acid substitution in the β chain of hemoglobin. This β chain of hemoglobin polymerizes upon deoxygenation, which distorts the shape of sickle red blood cells (sRBCs). The abnormal RBC shape renders them prone to hemolysis, leading to the release of cell-free hemoglobin and heme in the circulation.1

The excess levels of cell-free hemoglobin and heme with their catalytic action on the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) contribute to the high oxidative burden in SCD patients.2,3 Neutrophils of SCD patients are activated4 and produce significantly higher basal levels of ROS with lower levels of intracellular ROS scavengers.5 In addition, these neutrophils can capture circulating sRBCs, leading to reduced blood flow in experimental model of vaso-occlusive crises (VOC) induced by the inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α).6-9 The altered redox balance likely contributes to SCD pathogenesis.3,10

One neutrophil response that relies heavily on ROS is the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).11 NETs are decondensed chromatin decorated by granular enzymes (eg, neutrophil elastase [NE]) and are released by activated neutrophils.11 ROS generation,11 histone citrullination by peptidylarginine deiminase 4,12,13 and autophagy14 are prerequisites for NET release. A postulated function of NETs is to skim the blood and tissues for pathogens and eradicate pathogens with a high local concentration of granular enzymes.15,16 In addition, recent studies have demonstrated a detrimental role of NETs in noninfectious disorders such as small-vessel vasculitis,17 deep vein thrombosis,18 and transfusion-related acute lung injury.19,20 In experimentally induced deep vein thrombosis, NET is a part of venous thrombi in which it is entangled with platelets and RBCs.21 In vitro studies using a flow chamber have also shown that NETs can specifically capture platelets and RBCs.18 The ability of NETs to capture intravascular components raises the possibility that neutrophil-derived extracellular DNA fibers could contribute to VOC and the pathogenesis of SCD. We show here that NETs are generated in SCD from plasma heme and inflammatory cytokines, thus linking mechanistically the hemolysis and vaso-occlusive syndromes.

Methods

Human samples

Human blood samples were obtained from healthy nonpregnant adult volunteers and steady-state and crisis SCD patients by protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Berkeley sickle cell mice (Tg[Hu-miniLCRα1GγAγδβS] Hba−/−Hbb−/−), referred to as SCD mice, and control hemizygous mice (Tg[Hu-miniLCRα1GγAγδβS] Hba−/−Hbb+/−), referred to as SA mice, have been previously described.22,23 All experimental procedures in this study were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Reagents

Hemin (ferriprotoporphyrin IX chloride), iron (III) mesoporphyrin IX chloride, and zinc (II) protoporphyrin IX and protoporphyrin IX were purchased from Frontier Scientific. The stock solutions (5 mM) of each porphyrin were made in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; culture grade, Sigma) and diluted in Hanks balanced salt solution immediately before use in the in vitro NET assay. Human hemoglobin A0 was obtained from Sigma. Heme-hemopexin (Hx) and heme-human serum albumin (HSA) (Sigma) complexes were achieved by mixing equal molar ratio of heme and Hx or heme and HSA (1:1) and incubating for 30 minutes at 37°C immediately before use in the in vitro NET assay. For in vivo heme administration, hemin solutions were prepared by dissolving in 0.2 M NaOH and buffered to pH 7.5 with HCl. Hemin solutions were subsequently filtered through a 0.2-μm syringe filter unit; the concentration of the filtered solution was determined using a Quantichrom Heme assay (BioAssay Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNase I from bovine pancreas and antioxidant N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) were obtained from Sigma and reconstituted according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro NET assay

After isolation, neutrophils were primed with 2 ng/mL TNF-α at 37°C for 15 minutes. The cells were allowed to attach to poly-L-lysine–coated slides at 37°C for 20 minutes in the presence of TNF-α. The attached neutrophils were incubated with various stimuli at 37°C for indicated time. After stimulation, the cells were left unfixed and stained with both Sytox orange (cell-impermeable dye) and SYTO13 (cell-permeable dye) (Molecular Probes) and then imaged immediately for the presence of NETs. For costaining of DNA, citrullinated histone H3, (H3Cit) and NE, neutrophils were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked for immunofluorescence staining. Cells were incubated with goat anti-NE (M-18, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or rabbit anti-H3Cit (citrulline 2, 8, 17; Abcam) followed by species-specific secondary antibodies coupled with Alexa Fluor Dyes (Invitrogen). DNA was stained using SYTO13. We quantified in vitro NETs by measuring the length of DNA fibers. A DNA fiber was considered as a NET if its length exceeded 50 μm.

Lung whole-mount immunofluorescence

The procedure was done as previously described by Bruns et al24 with a few modifications. Briefly, 5 hours after TNF-α (0.5 μg) intraperitoneal injection, mice were euthanized 15 minutes after IV injection of anti-CD31 antibody (5 μg per animal, clone MEC13.3, BioLegend) to in vivo stain for endothelial cells in the lungs. The lungs were filled in situ with prewarmed low-melting agarose (2% weight to volume ratio, Promega). After solidification for 15 minutes at 4°C, the left lung was excised and glued to a 10-cm Petri dish filled with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and cut horizontally along the midline manually with a surgical blade. The half lung lobe was then incubated with Sytox orange at a final concentration of 5 μM and imaged immediately. We quantified in vivo NETs by measuring the length of each DNA fiber identified in the lungs in which fibers exceeding 60 μm were considered as a NET.

DNase I infusion

SCD mice were injected IV with 10 mg/kg DNase I at the same time of TNF-α administration.

Heme administration

Hemin was administered by intraperitoneal injection (50 μmol/kg body weight) 15 hours before TNF-α administration.

Hemopexin infusion

SCD mice were IV injected with 150 μg of hemopexin (derived from human plasma in saline, Athens Research & Technology) 15 hours before TNF-α administration.

Survival assay

Statistics

All data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) or median (interquartile ratio [IQR]). Comparisons between 2 samples were done using unpaired Student t tests or Mann-Whitney tests. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. (See supplemental Methods on the Blood Web site for additional methods.)

Results

NETs are generated in pulmonary microcirculation of SCD mice

To determine if NETs contribute to SCD pathogenesis, we first evaluated whether NETs were generated in SCD mice. We treated SCD mice with TNF-α, which can induce experimental VOC.6-9 We harvested the lungs of these mice 5 hours after TNF-α administration and stained the unfixed lungs with nucleic acid dye Sytox orange for extracellular DNA. Using this technique, we reproducibly detected putative NET DNA fibers in the lungs of SCD mice (Figure 1Ai). By contrast, such fibers were not observed in the lungs of hemizygous (SA) mice (Figure 1Aii). To confirm that these elongated DNA fibers were not resulting from section artifacts, we fixed the lung lobes with formalin and stained paraffin-embedded sections with hematoxylin and eosin. Hematoxylin and eosin staining clearly indicated that DNA fibers were present within the pulmonary vessels of SCD mice (Figure 1Bi-ii, arrows) and were absent in SA mice (Figure 1Biii-iv). To confirm that the network of extracellular DNA fibers was indeed bona fide NETs and not remnants of apoptotic or necrotic cells, we stained lung tissues with antibodies against NE—which has been associated with NETs15 and H3Cit—that was shown to be generated specifically during NET formation.26 These analyses revealed areas with robust NE staining (red, Figure 1Ci-ii) and H3Cit staining (red, Figure 1Ciii-iv) colocalizing with DNA streaks (green, Figure 1C) within the pulmonary blood vessels of SCD mice. The number of NETs in randomly selected fields of view of the immunofluorescence images was significantly greater in TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice compared with PBS-treated SCD or TNF-α–treated SA animals (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 1A). In addition, we found that soluble NET components such as plasma DNA and nucleosomes were significantly higher in the peripheral blood of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice (Figure 1E). Plasma myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was also significantly increased in TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, suggesting that neutrophils in these mice were activated (Figure 1F). These data thus indicate that NETs are formed in SCD mice and that they may contribute to the pathogenesis of this disease.

NETs are present within pulmonary vessels of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice. (A) Representative images of NETs (DNA/red/Sytox orange) detected in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice (i) and the lack of NETs in TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (ii). CD31 (blue/Alexa Fluor 647) labeled the endothelial cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. For imaging, different areas along the dissection were scanned down to an approximate 70 to 80 μm depth using an Axio Examiner.D1 microscope (Zeiss) equipped with a Yokogawa CSU-X1 confocal scan head with a 4-stack laser system (405-nm, 488-nm, 561-nm, and 642-nm wavelengths). Images were obtained using a 20× water immersion objective and as 3-dimensional stacks using Slidebook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations). (B) Representative histological images of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice (i,ii, arrows indicate NETs) and the lack of NETs in TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (iii,iv). Scale bar, 10 μm. Images were captured using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope equipped with a Zeiss Axiocam HRc camera (color) and a 63× oil immersion objective. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images of the lung sections of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice showing colocalization of extracellular DNA (green/SYTO 13) and NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i,ii) or H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, iii,iv). CD31 (blue/Alexa Fluor 647) labeled the endothelial cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. Images were captured using an Axio Examiner.D1 microscope equipped with a Yokogawa CSU-X1 confocal scan head with a 4-stack laser system (405-nm, 488-nm, 561-nm, and 642-nm wavelengths) and a 20× water immersion objective. Images were obtained using Slidebook software. (D) Quantification of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (gray bar, n = 3), SCD mice (white bar, n = 3), and PBS-treated SCD mice (green bar, n = 3). Results presented are the average values (mean ± SEM) of independent experiments with sex- and age-matched mice. *P < .05, ****P < .0001. (E) Quantification of NET biomarkers, plasma DNA (left), and plasma nucleosome (right) of TNF-α–treated SA mice (gray circle, n = 5), SCD mice (white circle, n = 5), and PBS-treated SCD mice (green circle, n = 5; Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], *P < .05, **P < .01). (F) Quantification of plasma MPO activity of TNF-α–treated SA mice (gray circle, n = 4), SCD mice (white circle, n = 6), and PBS-treated SCD mice (green circle, n = 4; Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], **P < .01).

NETs are present within pulmonary vessels of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice. (A) Representative images of NETs (DNA/red/Sytox orange) detected in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice (i) and the lack of NETs in TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (ii). CD31 (blue/Alexa Fluor 647) labeled the endothelial cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. For imaging, different areas along the dissection were scanned down to an approximate 70 to 80 μm depth using an Axio Examiner.D1 microscope (Zeiss) equipped with a Yokogawa CSU-X1 confocal scan head with a 4-stack laser system (405-nm, 488-nm, 561-nm, and 642-nm wavelengths). Images were obtained using a 20× water immersion objective and as 3-dimensional stacks using Slidebook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations). (B) Representative histological images of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice (i,ii, arrows indicate NETs) and the lack of NETs in TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (iii,iv). Scale bar, 10 μm. Images were captured using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope equipped with a Zeiss Axiocam HRc camera (color) and a 63× oil immersion objective. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images of the lung sections of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice showing colocalization of extracellular DNA (green/SYTO 13) and NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i,ii) or H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, iii,iv). CD31 (blue/Alexa Fluor 647) labeled the endothelial cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. Images were captured using an Axio Examiner.D1 microscope equipped with a Yokogawa CSU-X1 confocal scan head with a 4-stack laser system (405-nm, 488-nm, 561-nm, and 642-nm wavelengths) and a 20× water immersion objective. Images were obtained using Slidebook software. (D) Quantification of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (gray bar, n = 3), SCD mice (white bar, n = 3), and PBS-treated SCD mice (green bar, n = 3). Results presented are the average values (mean ± SEM) of independent experiments with sex- and age-matched mice. *P < .05, ****P < .0001. (E) Quantification of NET biomarkers, plasma DNA (left), and plasma nucleosome (right) of TNF-α–treated SA mice (gray circle, n = 5), SCD mice (white circle, n = 5), and PBS-treated SCD mice (green circle, n = 5; Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], *P < .05, **P < .01). (F) Quantification of plasma MPO activity of TNF-α–treated SA mice (gray circle, n = 4), SCD mice (white circle, n = 6), and PBS-treated SCD mice (green circle, n = 4; Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], **P < .01).

DNase I administration protects SCD mice

To determine if the presence of NETs in SCD mice contributes to the pathogenesis of the disease, we treated mice with DNase I before TNF-α administration because in vitro studies have demonstrated that DNase I can dismantle NETs.15 Accordingly, we found that DNase I treatment significantly lowered the number of NETs formed in the lungs of SCD mice (Figure 2A). DNase I treatment further increased the soluble NET component, plasma DNA, detected in the peripheral blood of treated mice (Figure 2B), indicating that DNase I might cleave extracellular DNA in the lung microcirculation that then entered the systemic circulation.

DNase I treatment significantly reduces NETs in TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, protects SCD mice from NET-associated hypothermia, and prolongs their survival by reducing acute lung injury. (A) Quantification of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice pretreated with vehicle (white bar, n = 3) or DNase I (red bar, n = 7). Results presented are the average values of independent experiments with sex- and age-matched mice (mean ± SEM, ***P < .001). (B) Quantification of NET biomarker, plasma DNA, of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice pretreated with vehicle (white circle, n = 6) or pretreated with DNase I (red circle, n = 10) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR]). (C) Reduction in rectal temperature of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (gray circle, n = 10), PBS-treated SCD mice (green circle, n = 3), and TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice (white circle, n = 10; mean ± SEM, *P < .05, ****P < .0001). (D) Reduction in rectal temperature of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, pretreated with vehicle (white circle, n = 6) or DNase I (red circle, n = 11; mean ± SEM, *P < .05). (E) Relationship between decrease in body temperature and number of NETs presented in the lungs of SA and SCD mice (r = 0.79, P < .0001, different color circles represent different treatments as stated in Figure 2C-D). (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curves after TNF-α treatment and surgical trauma in vehicle-treated (black line, n = 5) and DNase I–treated (red line, n = 7) groups (log-rank test, *P < .05). (G) Representative histology of lungs from vehicle-infused (arrows indicate the fibrillar appearance of alveolar walls) and DNase I–infused SCD mice after TNF-α administration and surgical procedure. Scale bar, 10 μm. Images were captured using Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope equipped with Zeiss Axiocam HRc camera (color) and a 40× oil immersion objective. (H) (Top) Total protein (left) and IgM concentration (right) in BAL fluid of vehicle- (white circle, n = 7) and DNase I–treated (red circle, n = 7) SCD mice and vehicle-treated SA mice (gray circle, n = 4) after TNF-α administration and surgical procedure (mean ± SEM, *P < .05, **P < .01). (Bottom) MPO activity per gram of tissue in lung homogenates (left) and in cell-free BAL fluid (right) of vehicle- (white circle, n = 7) and DNase I–treated (red circle, n = 7) SCD mice and vehicle-treated SA mice (gray circle, n = 4) after TNF-α administration and surgical procedure (mean ± SEM, * P < .05, **P < .01).

DNase I treatment significantly reduces NETs in TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, protects SCD mice from NET-associated hypothermia, and prolongs their survival by reducing acute lung injury. (A) Quantification of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice pretreated with vehicle (white bar, n = 3) or DNase I (red bar, n = 7). Results presented are the average values of independent experiments with sex- and age-matched mice (mean ± SEM, ***P < .001). (B) Quantification of NET biomarker, plasma DNA, of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice pretreated with vehicle (white circle, n = 6) or pretreated with DNase I (red circle, n = 10) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR]). (C) Reduction in rectal temperature of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (gray circle, n = 10), PBS-treated SCD mice (green circle, n = 3), and TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice (white circle, n = 10; mean ± SEM, *P < .05, ****P < .0001). (D) Reduction in rectal temperature of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, pretreated with vehicle (white circle, n = 6) or DNase I (red circle, n = 11; mean ± SEM, *P < .05). (E) Relationship between decrease in body temperature and number of NETs presented in the lungs of SA and SCD mice (r = 0.79, P < .0001, different color circles represent different treatments as stated in Figure 2C-D). (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curves after TNF-α treatment and surgical trauma in vehicle-treated (black line, n = 5) and DNase I–treated (red line, n = 7) groups (log-rank test, *P < .05). (G) Representative histology of lungs from vehicle-infused (arrows indicate the fibrillar appearance of alveolar walls) and DNase I–infused SCD mice after TNF-α administration and surgical procedure. Scale bar, 10 μm. Images were captured using Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope equipped with Zeiss Axiocam HRc camera (color) and a 40× oil immersion objective. (H) (Top) Total protein (left) and IgM concentration (right) in BAL fluid of vehicle- (white circle, n = 7) and DNase I–treated (red circle, n = 7) SCD mice and vehicle-treated SA mice (gray circle, n = 4) after TNF-α administration and surgical procedure (mean ± SEM, *P < .05, **P < .01). (Bottom) MPO activity per gram of tissue in lung homogenates (left) and in cell-free BAL fluid (right) of vehicle- (white circle, n = 7) and DNase I–treated (red circle, n = 7) SCD mice and vehicle-treated SA mice (gray circle, n = 4) after TNF-α administration and surgical procedure (mean ± SEM, * P < .05, **P < .01).

While monitoring the body temperature of mice during experiments, we noted that SCD mice experienced body temperature declines as a result of the TNF-α challenge (Figure 2C). We found that the reduction of body temperature correlated positively with the number of NETs generated in the lungs of these mice (Figure 2E, r = 0.79, P < .0001). Furthermore, pretreatment with DNase I protected TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice from NET-associated hypothermia (Figure 2D). Our previous studies have revealed that TNF-α treatment followed by surgical preparation of the cremaster muscles for intravital microscopy was lethal to SCD mice, but not SA mice, a few hours after the cremasteric preparation.6-9 NET-associated hypothermia of SCD mice was transient; the body temperature of these mice was back to normal 24 hours after TNF-α administration (data not shown), which is consistent with our prior observations that TNF-α administration is not sufficient (without surgical insult) to induce a lethal crisis.6 To investigate whether NET was associated with the rapid death of SCD mice after TNF-α and surgical preparation, we subjected these mice to the cremasteric preparation and TNF-α administration protocol. In agreement with previous observations, TNF-α–treated SCD mice died soon after cremasteric preparation (Figure 2F, black line). Remarkably, IV injection of DNase I significantly prolonged the survival of these mice (Figure 2F, red line). Thus, the formation of NETs in the lungs of SCD mice may represent a major factor in the long-sought cause of death of mice in this model and suggest a significant contribution of NETs in SCD pathogenesis.

To examine further the organ damage that may lead to the death of SCD mice, we infused DNase I or vehicle alone to SCD mice before the surgical preparation, and harvested lungs, livers, and kidneys 2 hours after the surgery, the time during which vehicle-infused SCD mice begin to succumb in this protocol, for histological evaluation. Although the lungs of SCD animals that underwent surgery and TNF-α treatment exhibited increased alveolar thickness and vascular congestion, DNase I–treated SCD mice had thinner and more uniform alveolar walls (Figure 2G). The lungs of most (6 of 8) vehicle-treated mice contained thickened alveolar walls with presence of proteinaceous debris in the alveoli (Figure 2G, arrows), whereas most DNase I–treated mice exhibited smooth alveolar walls, with 2 of 8 showing thickening and ragged appearance of alveolar walls. Although the exact nature of the injury is uncertain, the changes are suggestive of capillary wall damage and leakage of plasma proteins and fibrin into alveoli. To examine the alterations in lung vascular and epithelial permeability in more detail, we measured the protein concentration in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of DNase I–, vehicle-infused SCD mice and SA mice. Our results revealed that 2 hours after TNF-α administration and surgical insult, total protein concentration in BAL fluid was significantly elevated in SCD animals compared with that of SA mice, suggesting that the integrity of pulmonary endothelial and epithelial barrier was compromised in SCD mice (Figure 2H, top left). Importantly, DNase I infusion significantly reduced BAL fluid protein concentration of SCD mice, reflecting decreased protein flux across lung endothelium and epithelium (Figure 2H, top left). We also measured the concentration of immunoglobulin M (IgM), a high molecular weight molecule marker of increased lung permeability,27 in BAL fluid of the 3 groups of mice. Our results revealed that DNase I treatment significantly reduced BAL fluid IgM concentration in SCD mice to the level similar to that of SA mice (Figure 2H, top right). Because acute lung injury is often accompanied by an inflammatory response,28 we measured MPO activity in lung homogenates, which reflects accumulation of neutrophils in the lungs.27 We found that DNase I infusion significantly reduced MPO activity detected in lung homogenates of SCD mice (Figure 2H, bottom left). In addition, MPO activity in cell-free BAL fluid was significantly reduced in response to DNase I treatment, reflecting either the clearance of extravascular protein in the airspaces of treated mice or a reduction in the accumulation of activated neutrophils (Figure 2H, bottom right).

Both DNase I– and vehicle-infused SCD mice exhibited chronic liver and kidney damage, but there was no major difference in the histopathology of these organs between the 2 groups. Our data thus indicate that DNase I treatment specifically alleviates SCD acute lung injury induced by this protocol and implies that the acute lung injury causes the death of SCD mice.

Sickle cell plasma stimulates NET formation

To gain insight into the mechanism by which NETs are generated in SCD mice, we tested the capacity of plasma of SCD mice to stimulate NET formation in neutrophils. We isolated plasma from both SCD and SA mice 5 hours after TNF-α administration for an in vitro assay. We found that the addition of SCD plasma to TNF-α–primed wild-type bone marrow (BM) neutrophils led to the generation of a network of extracellular DNA fibers (Figure 3A, right), whereas primed neutrophils treated with SA-derived plasma failed to produce extracellular DNA fibers (Figure 3A, left). An extracellular DNA network formed as a result of SCD plasma stimulation containing H3Cit (Figure 3Bi) and was associated with NE (Figure 3Bii), suggesting that these DNA fibers were NETs. SCD plasma was able to stimulate TNF-α–primed wild-type BM neutrophils to produce an average of 0.72 ± 0.15 NETs for every 50 cells counted, whereas SA plasma was unable to induce NET formation (Figure 3C and supplemental Figure 1B-C). These results suggest that a plasma factor is capable of stimulating neutrophils to produce NETs.

Plasma from TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice and crisis SCD patients induce NET formation in TNF-α–primed neutrophils. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of NETs released by TNF-α–primed wild-type BM neutrophils. DNA was stained with SYTO13 (cell-permeable nuclear acid dye, green) and Sytox orange (cell-impermeable nuclear acid dye, red). Primed wild-type neutrophils were stimulated with plasma of either TNF-α–treated SA mice (left) or TNF-α–treated SCD mice (right). Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Representative immunofluorescence images of DNA (green/SYTO13), H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i), or NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, ii) of NETs generated by TNF-α–primed wild-type neutrophils that were stimulated with plasma of TNF-α–treated SCD mice. Insets show NETs stained with DNA dye (green/SYTO13) and isotype control antibodies for H3Cit and NE. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed wild-type BM neutrophils stimulated with plasma of TNF-α–treated SA mice (black bar) and TNF-α–treated SCD mice (white bar). Results are average values from 4 independent experiments (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (D) Quantification of NET biomarkers, plasma DNA (left), and nucleosome (right) of non-SCD individuals (gray circle, n = 5), steady-state SCD patients (yellow circle, n = 7), and crisis SCD patients (red circle, n = 10; Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], *P < .05). (E) Quantification of plasma MPO activity of non-SCD individuals (gray circle, n = 4), steady-state SCD patients (yellow circle, n = 7), and crisis SCD patients (red circle, n = 10; Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], *P < .05, **P < .01). (F) Representative immunofluorescence images of DNA (green/SYTO13), H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i), or NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, ii) of NETs generated by TNF-α–primed human neutrophils that were stimulated with plasma of crisis SCD patient. Insets show NETs stained with DNA dye (green/SYTO13) and isotype control antibodies for H3Cit and NE. Scale bar, 10 μm. (G) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed human neutrophils stimulated with plasma of non-SCD individuals (gray circle, n = 3), steady-state SCD patients (yellow circle, n = 7), and crisis SCD patients (red circle, n = 8; mean ± SEM, *P < .05, **P < .01).

Plasma from TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice and crisis SCD patients induce NET formation in TNF-α–primed neutrophils. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of NETs released by TNF-α–primed wild-type BM neutrophils. DNA was stained with SYTO13 (cell-permeable nuclear acid dye, green) and Sytox orange (cell-impermeable nuclear acid dye, red). Primed wild-type neutrophils were stimulated with plasma of either TNF-α–treated SA mice (left) or TNF-α–treated SCD mice (right). Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Representative immunofluorescence images of DNA (green/SYTO13), H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i), or NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, ii) of NETs generated by TNF-α–primed wild-type neutrophils that were stimulated with plasma of TNF-α–treated SCD mice. Insets show NETs stained with DNA dye (green/SYTO13) and isotype control antibodies for H3Cit and NE. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed wild-type BM neutrophils stimulated with plasma of TNF-α–treated SA mice (black bar) and TNF-α–treated SCD mice (white bar). Results are average values from 4 independent experiments (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (D) Quantification of NET biomarkers, plasma DNA (left), and nucleosome (right) of non-SCD individuals (gray circle, n = 5), steady-state SCD patients (yellow circle, n = 7), and crisis SCD patients (red circle, n = 10; Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], *P < .05). (E) Quantification of plasma MPO activity of non-SCD individuals (gray circle, n = 4), steady-state SCD patients (yellow circle, n = 7), and crisis SCD patients (red circle, n = 10; Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], *P < .05, **P < .01). (F) Representative immunofluorescence images of DNA (green/SYTO13), H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i), or NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, ii) of NETs generated by TNF-α–primed human neutrophils that were stimulated with plasma of crisis SCD patient. Insets show NETs stained with DNA dye (green/SYTO13) and isotype control antibodies for H3Cit and NE. Scale bar, 10 μm. (G) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed human neutrophils stimulated with plasma of non-SCD individuals (gray circle, n = 3), steady-state SCD patients (yellow circle, n = 7), and crisis SCD patients (red circle, n = 8; mean ± SEM, *P < .05, **P < .01).

To assess the relevance in human SCD, we compared the DNA concentration, nucleosome content, and MPO activity in the plasma of healthy individuals and SCD patients at steady state or in crisis. Plasma of crisis SCD patients contained significantly higher DNA and nucleosome compared with the other 2 groups (Figure 3D, left and right). In addition, MPO activity was significantly higher in crisis plasma than in nonsickle and steady-state plasma (Figure 3E), suggesting an enhanced neutrophil activity that may potentiate increased NET formation in the crisis patients. We next tested the capacity of SCD patient plasma to stimulate NET formation in human peripheral neutrophils. Our results revealed that SCD patient plasma activated neutrophils to produce H3Cit- and NE-positive NETs (Figure 3F). In addition, crisis plasma stimulated neutrophils to produce significantly more NETs than those induced by nonsickle and steady-state plasma (Figure 3G). These data suggest that the plasma from both mouse and human SCD can trigger NET formation.

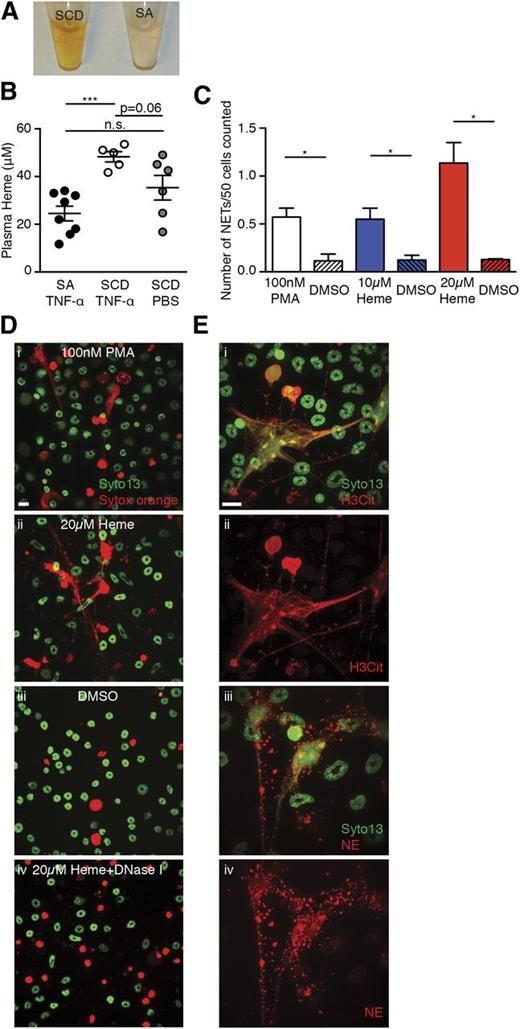

Heme induces NET formation in neutrophils in vitro

Plasma of SCD animals has a dark brownish color that is consistent with elevated levels of methemalbumin seen in chronic hemolytic disorders (Figure 4A).29 Elevated heme oxygenase-1 has been reported to inhibit VOC in SCD mouse models,30 and more recently heme has been suggested to induce acute chest syndrome (ACS) and VOC by activating endothelial cells.31,32 Plasma heme concentrations were higher in TNF-α–treated SCD mice than SA mice (Figure 4B). Using an in vitro assay, we found that heme stimulated TNF-α–primed BM neutrophils to generate NETs in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4C and 4Di-iii). These DNA fibers could be cleared by the addition of DNase I (Figure 4Div) and were associated with H3Cit (Figure 4Ei-ii), and NE (Figure 4Eiii-iv). These data thus suggest that heme can induce NET formation in vitro.

Heme stimulates NET formation in neutrophils in vitro. (A) Representative images of plasma of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice and SA mice. (B) Quantification of plasma heme concentrations of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (black circle, n = 8), TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice (white circle, n = 5), and PBS-treated SCD mice (gray circle, n = 6; mean ± SEM, ***P < .001). (C) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils stimulated with 100 nM phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (white bar), 10 μM heme (blue bar), and 20 μM heme (red bar). The shaded bars represent DMSO treatment of each condition. Results are the average values of 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM, *P < .05). (D) Representative immunofluorescence images of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils stimulated with (i) 100 nM PMA, (ii) 20 μM heme, (iii) DMSO, and (iv) 20 μM heme; the slide was then treated with DNase I. (E) Representative immunofluorescence images of DNA (green/SYTO13), H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i,ii), or NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, iii,iv) of NETs generated by TNF-α–primed wild-type neutrophils that were stimulated with 20 μM heme. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Heme stimulates NET formation in neutrophils in vitro. (A) Representative images of plasma of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice and SA mice. (B) Quantification of plasma heme concentrations of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (black circle, n = 8), TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice (white circle, n = 5), and PBS-treated SCD mice (gray circle, n = 6; mean ± SEM, ***P < .001). (C) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils stimulated with 100 nM phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (white bar), 10 μM heme (blue bar), and 20 μM heme (red bar). The shaded bars represent DMSO treatment of each condition. Results are the average values of 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM, *P < .05). (D) Representative immunofluorescence images of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils stimulated with (i) 100 nM PMA, (ii) 20 μM heme, (iii) DMSO, and (iv) 20 μM heme; the slide was then treated with DNase I. (E) Representative immunofluorescence images of DNA (green/SYTO13), H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i,ii), or NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, iii,iv) of NETs generated by TNF-α–primed wild-type neutrophils that were stimulated with 20 μM heme. Scale bar, 10 μm.

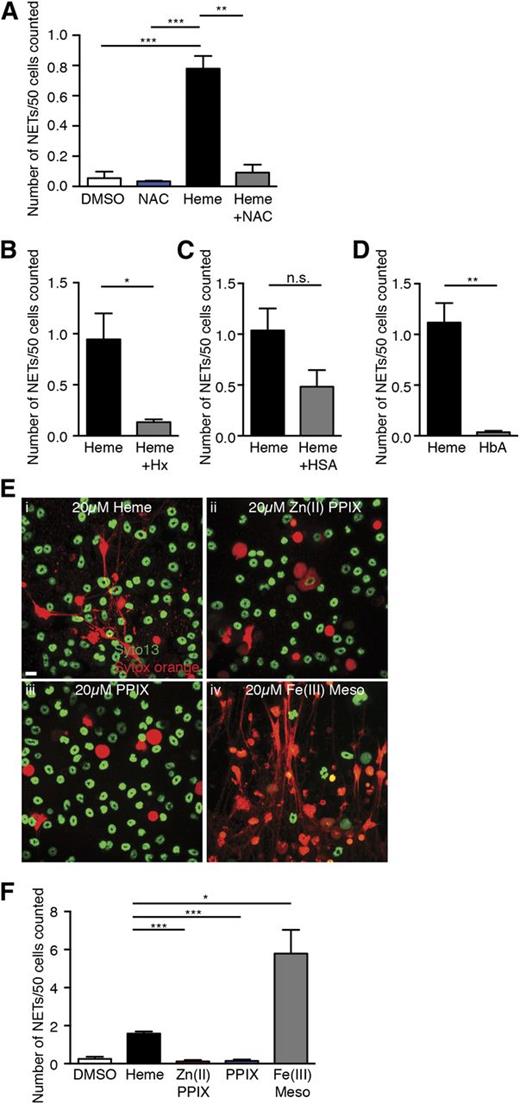

Heme-induced NET formation is dependent on ROS and heme-iron

Heme can activate blood leukocytes and significantly increase their intracellular ROS concentration.33,34 Because ROS generation is upstream of NET formation in neutrophils,11 we hypothesized that heme induces NET formation through upregulation of intracellular ROS. To assess whether heme-mediated NET formation in neutrophils was ROS-dependent, we treated neutrophils with the antioxidant NAC. We found that NAC abrogated heme-stimulated NET formation (Figure 5A). Because the redox activities of heme are inhibited by its complexation with hemopexin,35,36 we mixed an equal molar ratio of heme and hemopexin and simulated neutrophils with the complex. Formation of the heme-hemopexin complex was confirmed by the shift in the absorption spectrum from free heme to protein-bound heme by spectrophotometry (data not shown). Addition of hemopexin to heme significantly reduced the number of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils (Figure 5B). By contrast, the heme-human serum albumin complex had a slight but not significant reduction in NET formation of primed neutrophils (Figure 5C). Thus, heme-stimulated NET formation in TNF-α–primed neutrophils is dependent on ROS; complexation of heme with hemopexin inhibits this activity.

Heme-mediated NET formation in TNF-α–primed neutrophils is dependent on ROS and heme-iron and can be blocked by hemopexin complexation. (A) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils treated with DMSO (white bar), antioxidant NAC alone (10 mM, blue bar), heme alone (20 μM, black bar), heme (20 μM), and NAC (10 mM) (gray bar). Results are the average values of 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM, **P < .01, ***P < .001). (B) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils treated with free heme (black bar) or Hx complex (gray bar). Results are the average values of 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM, *P < .05). (C) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils treated with free heme (black bar) or HSA complex (gray bar). Results presented are the average values of 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM). (D) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils treated with free heme (black bar) or HbA (gray bar). Results are the average values of 4 independent experiments (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (E) Representative immunofluorescence images of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils stimulated with 20 μM of (i) heme, (ii) zinc (II) protoporphyrin IX (Zn (II) PPIX), (iii) protoporphyrin (PPIX), and (iv) iron (III) mesoporphyrin IX (Fe (III) Meso). (F) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils treated with DMSO (white bar), heme (black bar), Zn (II) PPIX (red bar), PPIX (blue bar), and Fe (III) Meso (gray bar). Results are the average values of 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM, *P < .05, ***P < .001).

Heme-mediated NET formation in TNF-α–primed neutrophils is dependent on ROS and heme-iron and can be blocked by hemopexin complexation. (A) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils treated with DMSO (white bar), antioxidant NAC alone (10 mM, blue bar), heme alone (20 μM, black bar), heme (20 μM), and NAC (10 mM) (gray bar). Results are the average values of 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM, **P < .01, ***P < .001). (B) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils treated with free heme (black bar) or Hx complex (gray bar). Results are the average values of 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM, *P < .05). (C) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils treated with free heme (black bar) or HSA complex (gray bar). Results presented are the average values of 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM). (D) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils treated with free heme (black bar) or HbA (gray bar). Results are the average values of 4 independent experiments (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (E) Representative immunofluorescence images of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils stimulated with 20 μM of (i) heme, (ii) zinc (II) protoporphyrin IX (Zn (II) PPIX), (iii) protoporphyrin (PPIX), and (iv) iron (III) mesoporphyrin IX (Fe (III) Meso). (F) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed neutrophils treated with DMSO (white bar), heme (black bar), Zn (II) PPIX (red bar), PPIX (blue bar), and Fe (III) Meso (gray bar). Results are the average values of 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM, *P < .05, ***P < .001).

Increased hemolysis in SCD can lead to the release of both cell-free hemoglobin and heme.1 Our in vitro data showed that free heme and serum albumin–bound heme were capable of stimulating NET formation. To evaluate whether the increased cell-free hemoglobin also contributed to NET formation in SCD, we stimulated TNF-α–primed neutrophils with human hemoglobin A0 (HbA). Unlike heme, we found that equimolar amounts of HbA did not activate primed neutrophils to release NETs (Figure 5D). Next, we took advantage of several heme analogs to investigate the structural determinants of heme required to activate NET release. We found that neither Zn (II) protoporphyrin IX nor protoporphyrin IX could stimulate NET formation of TNF-α–primed neutrophils (Figure 5Eii-iii,F), suggesting an iron atom in the porphyrin ring is necessary for heme-mediated NET formation. We also tested the effect of Fe (III) mesoporphyrin IX, a heme analog that has an iron atom but has 2 ethyl groups substituted its vinyl groups. Remarkably, primed neutrophils subjected to Fe (III) mesoporphyrin IX stimulation generated significantly more NETs than heme stimulation (Figure 5Eiv,F). These results suggest that heme-mediated NET formation in TNF-α–primed neutrophils depends on the presence of iron atoms.

Heme stimulates NET formation in vivo

Because TNF-α did not induce NETs in SA mice, which do not exhibit pronounced hemolysis (Figure 1), we reasoned that exogenous addition of heme might be capable of inducing NETs in these animals after TNF-α priming. To investigate this issue, we injected SA mice with heme before TNF-α administration. Heme injection significantly increased plasma heme concentration in SA mice compared with vehicle treatment (Figure 6A). Increased plasma heme triggered NET formation and resulted in significantly higher number of NETs in the lung (Figure 6B). The presence of NETs in pulmonary vessels of SA mice was confirmed with hematoxylin and eosin staining of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded lung sections (Figure 6C, arrows) and immunofluorescence analysis that revealed extracellular DNA costaining with NE (red, Figure 6Di-ii) or H3Cit (red, Figure 6Diii-iv). In agreement with an increased number of pulmonary NETs, levels of soluble NET components, plasma DNA, and nucleosomes were significantly higher in heme-pretreated SA mice compared with vehicle-pretreated animals (Figure 6E). Plasma MPO activity was also significantly increased as a result of heme pretreatment, indicating an enhanced neutrophil activity (Figure 6F). Furthermore, we observed body temperature reduction after TNF-α administration in heme-pretreated SA mice that was not observed in SA mice not exposed to exogenous heme (Figure 6G). We conclude from these experiments that heme is capable of stimulating neutrophils to generate NETs both in vitro and in vivo.

Heme stimulates NET formation in neutrophils in vivo. (A) Quantification of plasma heme concentrations of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice pretreated with vehicle (gray circle, n = 8) or heme (red circle, n = 11) (mean ± SEM, ****P < .0001). (B) Quantification of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice, vehicle pretreated (gray bar, n = 4) or heme pretreated (red bar, n = 6). Results presented are the average values of independent experiments with sex- and age-matched mice (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (C) Representative histological images of NETs in the lungs of heme pretreated-, TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (arrows indicate NETs). Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Representative immunofluorescence images of the lung sections of heme pretreated-, TNF-α–stimulated SA mice showing colocalization of extracellular DNA (green/SYTO13) and NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i-ii) or H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, iii-iv). CD31 (blue/Alexa Fluor 647) labeled the endothelial cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Quantification of NET biomarkers, plasma DNA (left), and plasma nucleosome (right) of TNF-α–challenged SA mice, vehicle pretreated (gray circle, n = 7) or heme pretreated (red circle, n = 6) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], **P < .01). (F) Quantification of plasma MPO activity of TNF-α–challenged SA mice, vehicle pretreated (gray circle, n = 4) or heme pretreated (red circle, n = 6) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], *P < .05). (G) Decrease in rectal temperature of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice, pretreated with vehicle (gray circle, n = 12) or heme (red circle, n = 12) (mean ± SEM, **P < .01).

Heme stimulates NET formation in neutrophils in vivo. (A) Quantification of plasma heme concentrations of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice pretreated with vehicle (gray circle, n = 8) or heme (red circle, n = 11) (mean ± SEM, ****P < .0001). (B) Quantification of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice, vehicle pretreated (gray bar, n = 4) or heme pretreated (red bar, n = 6). Results presented are the average values of independent experiments with sex- and age-matched mice (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (C) Representative histological images of NETs in the lungs of heme pretreated-, TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (arrows indicate NETs). Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Representative immunofluorescence images of the lung sections of heme pretreated-, TNF-α–stimulated SA mice showing colocalization of extracellular DNA (green/SYTO13) and NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i-ii) or H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, iii-iv). CD31 (blue/Alexa Fluor 647) labeled the endothelial cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Quantification of NET biomarkers, plasma DNA (left), and plasma nucleosome (right) of TNF-α–challenged SA mice, vehicle pretreated (gray circle, n = 7) or heme pretreated (red circle, n = 6) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], **P < .01). (F) Quantification of plasma MPO activity of TNF-α–challenged SA mice, vehicle pretreated (gray circle, n = 4) or heme pretreated (red circle, n = 6) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], *P < .05). (G) Decrease in rectal temperature of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice, pretreated with vehicle (gray circle, n = 12) or heme (red circle, n = 12) (mean ± SEM, **P < .01).

Hemopexin prevents NET formation by reducing plasma heme concentration in SCD mice

Because we found that hemopexin can prevent NETs in vitro (Figure 5B), we hypothesized that hemopexin administration could prevent NET formation and may protect SCD mice from NET-associated hypothermia. Hemopexin infusion significantly lowered the plasma heme concentration of SCD mice compared with vehicle-infused animals (Figure 7A). Lowered plasma heme levels in SCD mice led to reductions in the number of pulmonary NETs and a decrease in plasma DNA and nucleosomes in these mice (Figure 7B-C). Hemopexin infusion, which limited heme availability and prevented heme from stimulating neutrophils, also led to a significant reduction in MPO activity detected in SCD plasma (Figure 7D). The reduced neutrophil activation was consistent with reduced NET formation in treated mice. In addition, hemopexin treatment alleviated TNF-α–treated SCD mice from NET-associated hypothermia (Figure 7E). These results indicate that, by forming complex with heme and lowering the plasma heme concentration, hemopexin is capable of inhibiting NET formation in SCD mice and attenuating the acute body temperature decline in response to TNF-α administration.

Hemopexin infusion decreases NETs in TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice and protects SCD mice from NET-associated hypothermia. (A) Quantification of plasma heme concentrations of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, vehicle pretreated (white circle, n = 13) or Hx pretreated (gray circle, n = 13) (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (B) Quantification of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, vehicle pretreated (white bar, n = 6) or Hx pretreated (gray bar, n = 10). Results presented are the average values of independent experiments with sex- and age-matched mice (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (C) Quantification of NET biomarkers, plasma DNA (left) and plasma nucleosome (right), from TNF-α–challenged SCD mice, vehicle pretreated (white circle, n = 14) or Hx pretreated (gray circle, n = 10) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], **P < .01). (D) Quantification of plasma MPO activity of TNF-α–challenged SCD mice, vehicle pretreated (white circle, n = 6) or Hx pretreated (gray circle, n = 6) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], **P < .01). (E) Decrease in rectal temperature of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, pretreated with vehicle (white circle, n = 13) or Hx (gray circle, n = 13; mean ± SEM, *P < .05).

Hemopexin infusion decreases NETs in TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice and protects SCD mice from NET-associated hypothermia. (A) Quantification of plasma heme concentrations of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, vehicle pretreated (white circle, n = 13) or Hx pretreated (gray circle, n = 13) (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (B) Quantification of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, vehicle pretreated (white bar, n = 6) or Hx pretreated (gray bar, n = 10). Results presented are the average values of independent experiments with sex- and age-matched mice (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (C) Quantification of NET biomarkers, plasma DNA (left) and plasma nucleosome (right), from TNF-α–challenged SCD mice, vehicle pretreated (white circle, n = 14) or Hx pretreated (gray circle, n = 10) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], **P < .01). (D) Quantification of plasma MPO activity of TNF-α–challenged SCD mice, vehicle pretreated (white circle, n = 6) or Hx pretreated (gray circle, n = 6) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], **P < .01). (E) Decrease in rectal temperature of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, pretreated with vehicle (white circle, n = 13) or Hx (gray circle, n = 13; mean ± SEM, *P < .05).

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that elevated plasma heme in SCD mice can induce NET formation in the presence of TNF-α. The formation of NETs in the lungs of SCD mice was associated with hypothermia and rapid death, which could be attenuated and delayed, respectively, by clearing NETs with DNase I. Our results show that up- or down-modulation of plasma heme concentrations can either induce or prevent, respectively, in vivo NET formation. These results uncover a pivotal role for heme in stimulating neutrophil NET release. Heme-mediated NETs may serve as a novel therapeutic target in treating SCD and other pathological states involving severe hemolysis.

SCD is characterized by chronic hemolysis with elevated steady-state levels of cell-free hemoglobin and plasma heme.1 It has been proposed that heme promotes SCD pathogenesis by increasing adhesion to endothelium from upregulation of adhesion molecules37 and more recently demonstrated that heme induces ACS and VOC by activating Toll-like receptor 4 signaling on endothelial cells.31,32 Our study adds to the current understanding of heme-mediated SCD pathogenesis by introducing a novel function of heme in which we suggest that it can directly activate neutrophils to release NETs, which contributes to disease severity.

Our results indicate that proinflammatory cytokine priming is necessary to trigger heme-mediated NET formation with physiological heme concentrations of SCD mice. Neither TNF-α nor heme alone was sufficient to achieve the stimulation threshold for NET release as we have not detected NETs in TNF-α–stimulated SA mice and steady-state SCD mice. Several cytokines including TNF-α,17 interferon-α,38,39 granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor,40 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor41 have been shown to potentiate the generation of NETs. An increase in systemic TNF-α concentration may be associated with infectious episodes, which are important contributing factors for severe complications such as ACS in patients with SCD.42,43 Our data suggest a model in which proinflammatory cytokines predispose neutrophils to be activated by circulating heme that is readily available in SCD individuals. In addition, the present results raise the possibility that NETs play an important role in the pathogenesis of ACS.

The mechanism by which heme stimulates NET formation in neutrophils is currently unknown, but our data suggest that heme-induced NET release could be linked with ROS generation in neutrophils. We have found that the antioxidant NAC abrogated heme-mediated NET release, suggesting that heme-elicited ROS increase in neutrophil33,34 is essential for NET formation. In addition, the requirement for heme-iron in heme-mediated ROS generation44 and NET production further emphasizes the link between heme-induced oxidative burst and heme-mediated NET formation.

Hemolysis releases cell-free hemoglobin and heme in the circulation of patients with hemoglobinopathies.1 Cell-free hemoglobin has been shown to contribute to SCD severity by increasing oxidative stress and limiting nitric oxide bioavailability.1-3 Our data, however, indicate that heme, but not hemoglobin, can induce NETs in this disease.

Although we have not found a significant effect of hemopexin administration on survival of SCD mice, our dosages failed to reduce plasma concentration of heme after TNF-α administration and surgical trauma. However, DNase I treatment did prolong the survival of SCD mice, which indicates that NETs contribute to the rapid death of SCD mice after TNF-α administration and surgical trauma. BAL and histological evaluation of SCD lungs have revealed evidence of increased vascular permeability, inflammation, and thickened alveolar walls following this VOC protocol. DNase I treatment improved these abnormalities, suggesting that the fibrillar appearance and capillary wall damage may be due to a localized high concentration of exposed histones and NET-derived granular enzymes. Liberated histones can indeed induce platelet activation and aggregation18,45 and also promote neutrophil margination and accumulation in alveolar microvessels.46 Our data are thus consistent with the possibility that NETs inflict damage on endothelial cells, promoting accumulation of blood cells in pulmonary vessels and resulting in impaired flow and gas exchanges, and thus contributing to rapid death of these mice.

In summary, our results indicate that NETs are formed and likely pathogenic in SCD. Our findings, supported by a recent report of circulating nucleosomes in SCD patients admitted for VOC or ACS,47 highlight a crucial role for heme in inducing NET formation in neutrophils after proinflammatory cytokine priming. The association of short alleles of the heme oxygenase-1 promoter (associated with higher enzyme activity) with lower rates of hospitalization for ACS48 also supports our findings that NETs are generated in the pulmonary vasculature in SCD. Managing the amount of circulating heme in individuals with SCD by increasing their plasma hemopexin may therefore be a useful strategy to prevent NET-inflicted damages.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Rani Sellers of the histology core for blind histopathological analyses and Drs Syun-Ru Yeh and Bing-Yu Chiang for measurement of absorption spectrum of free heme and protein-bound heme.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01 HL069438 and HL097700) (P.S.F.) and (grant R01 HL102101) (D.D.W.).

Authorship

Contribution: G.C. designed the research, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures, and wrote the manuscript; D.Z. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and provided valuable input on the writing of the manuscript; T.A.F. performed and analyzed plasma DNA and nucleosome experiments; D.M. provided sickle cell disease patient samples; D.D.W. supervised the research and provided valuable input on the writing of the manuscript; P.S.F. supervised the research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors gave conceptual advice.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Paul S. Frenette, Ruth L. and David S. Gottesman Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1301 Morris Park Ave, Price Center, Room 101B, Bronx, NY 10461; e-mail: paul.frenette@einstein.yu.edu.

![Figure 1. NETs are present within pulmonary vessels of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice. (A) Representative images of NETs (DNA/red/Sytox orange) detected in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice (i) and the lack of NETs in TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (ii). CD31 (blue/Alexa Fluor 647) labeled the endothelial cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. For imaging, different areas along the dissection were scanned down to an approximate 70 to 80 μm depth using an Axio Examiner.D1 microscope (Zeiss) equipped with a Yokogawa CSU-X1 confocal scan head with a 4-stack laser system (405-nm, 488-nm, 561-nm, and 642-nm wavelengths). Images were obtained using a 20× water immersion objective and as 3-dimensional stacks using Slidebook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations). (B) Representative histological images of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice (i,ii, arrows indicate NETs) and the lack of NETs in TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (iii,iv). Scale bar, 10 μm. Images were captured using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope equipped with a Zeiss Axiocam HRc camera (color) and a 63× oil immersion objective. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images of the lung sections of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice showing colocalization of extracellular DNA (green/SYTO 13) and NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i,ii) or H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, iii,iv). CD31 (blue/Alexa Fluor 647) labeled the endothelial cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. Images were captured using an Axio Examiner.D1 microscope equipped with a Yokogawa CSU-X1 confocal scan head with a 4-stack laser system (405-nm, 488-nm, 561-nm, and 642-nm wavelengths) and a 20× water immersion objective. Images were obtained using Slidebook software. (D) Quantification of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (gray bar, n = 3), SCD mice (white bar, n = 3), and PBS-treated SCD mice (green bar, n = 3). Results presented are the average values (mean ± SEM) of independent experiments with sex- and age-matched mice. *P < .05, ****P < .0001. (E) Quantification of NET biomarkers, plasma DNA (left), and plasma nucleosome (right) of TNF-α–treated SA mice (gray circle, n = 5), SCD mice (white circle, n = 5), and PBS-treated SCD mice (green circle, n = 5; Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], *P < .05, **P < .01). (F) Quantification of plasma MPO activity of TNF-α–treated SA mice (gray circle, n = 4), SCD mice (white circle, n = 6), and PBS-treated SCD mice (green circle, n = 4; Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], **P < .01).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/123/24/10.1182_blood-2013-10-529982/4/m_3818f1.jpeg?Expires=1769096726&Signature=YKhMtybpXWuF4aCXM2tdXEIvydqt-ktwprCoWexPjb4NAcrZ1XImqWjWcu9MU1nAH7pBzq~159BY4qJezoqhf7DpleQcTaNFJwyP9eB~lKCh0W2xqQwdj7DtzHhe~2fMTb35DmAaJm5OBsyuvJe-PgyPfnmyjWyrglCQuqUFzoQxDuROSjENUmY9OHWlX~G3wue3C5F7d0M-PXJOmoyMF5xlJ-3b5XIt3K3HBBWII5h6nA4FiG-j6WBvtHKQWJ9bp1hhGpGa3grTxTp4ecpcB~EKi~MJC5l2N3FpRuaRd3m0WK3T~n4zUmhEZbyUC1WtdzlUfGfhysiPGRyTK5MyCw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 2. DNase I treatment significantly reduces NETs in TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, protects SCD mice from NET-associated hypothermia, and prolongs their survival by reducing acute lung injury. (A) Quantification of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice pretreated with vehicle (white bar, n = 3) or DNase I (red bar, n = 7). Results presented are the average values of independent experiments with sex- and age-matched mice (mean ± SEM, ***P < .001). (B) Quantification of NET biomarker, plasma DNA, of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice pretreated with vehicle (white circle, n = 6) or pretreated with DNase I (red circle, n = 10) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR]). (C) Reduction in rectal temperature of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (gray circle, n = 10), PBS-treated SCD mice (green circle, n = 3), and TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice (white circle, n = 10; mean ± SEM, *P < .05, ****P < .0001). (D) Reduction in rectal temperature of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, pretreated with vehicle (white circle, n = 6) or DNase I (red circle, n = 11; mean ± SEM, *P < .05). (E) Relationship between decrease in body temperature and number of NETs presented in the lungs of SA and SCD mice (r = 0.79, P < .0001, different color circles represent different treatments as stated in Figure 2C-D). (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curves after TNF-α treatment and surgical trauma in vehicle-treated (black line, n = 5) and DNase I–treated (red line, n = 7) groups (log-rank test, *P < .05). (G) Representative histology of lungs from vehicle-infused (arrows indicate the fibrillar appearance of alveolar walls) and DNase I–infused SCD mice after TNF-α administration and surgical procedure. Scale bar, 10 μm. Images were captured using Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope equipped with Zeiss Axiocam HRc camera (color) and a 40× oil immersion objective. (H) (Top) Total protein (left) and IgM concentration (right) in BAL fluid of vehicle- (white circle, n = 7) and DNase I–treated (red circle, n = 7) SCD mice and vehicle-treated SA mice (gray circle, n = 4) after TNF-α administration and surgical procedure (mean ± SEM, *P < .05, **P < .01). (Bottom) MPO activity per gram of tissue in lung homogenates (left) and in cell-free BAL fluid (right) of vehicle- (white circle, n = 7) and DNase I–treated (red circle, n = 7) SCD mice and vehicle-treated SA mice (gray circle, n = 4) after TNF-α administration and surgical procedure (mean ± SEM, * P < .05, **P < .01).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/123/24/10.1182_blood-2013-10-529982/4/m_3818f2.jpeg?Expires=1769096726&Signature=TZPgKCWQx7N6KEi8E6uzyvRoiEe1CVtW~I65xpZiTSfHt91GjFkZ0NUK-xz1NJ~lVvx5rHiN2lxcDmZbw0PSOF~i1CuLAUj9vKm-hZJnUvXSfn72ajLLHoN5LCbIFf31JXDAa0z~4cQtOmBqUN8IEF2406lXq3JImcxf8aGxc1lA8GpFpUL6iMqgwa7iM2vSu2MNCRy25M51iONP~JDEwoqROut3jaSCKdRT5hN~V89EQUP3xsfz247w~EqV0j8SP7GyK4nnrl3qq-wYqu3s2gn--DCvilZciSt2wSbI3aPzmP-mlBhyTqnIOm6p0MgItJU1b07W5UtszxPX7tekcw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. Plasma from TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice and crisis SCD patients induce NET formation in TNF-α–primed neutrophils. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of NETs released by TNF-α–primed wild-type BM neutrophils. DNA was stained with SYTO13 (cell-permeable nuclear acid dye, green) and Sytox orange (cell-impermeable nuclear acid dye, red). Primed wild-type neutrophils were stimulated with plasma of either TNF-α–treated SA mice (left) or TNF-α–treated SCD mice (right). Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Representative immunofluorescence images of DNA (green/SYTO13), H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i), or NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, ii) of NETs generated by TNF-α–primed wild-type neutrophils that were stimulated with plasma of TNF-α–treated SCD mice. Insets show NETs stained with DNA dye (green/SYTO13) and isotype control antibodies for H3Cit and NE. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed wild-type BM neutrophils stimulated with plasma of TNF-α–treated SA mice (black bar) and TNF-α–treated SCD mice (white bar). Results are average values from 4 independent experiments (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (D) Quantification of NET biomarkers, plasma DNA (left), and nucleosome (right) of non-SCD individuals (gray circle, n = 5), steady-state SCD patients (yellow circle, n = 7), and crisis SCD patients (red circle, n = 10; Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], *P < .05). (E) Quantification of plasma MPO activity of non-SCD individuals (gray circle, n = 4), steady-state SCD patients (yellow circle, n = 7), and crisis SCD patients (red circle, n = 10; Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], *P < .05, **P < .01). (F) Representative immunofluorescence images of DNA (green/SYTO13), H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i), or NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, ii) of NETs generated by TNF-α–primed human neutrophils that were stimulated with plasma of crisis SCD patient. Insets show NETs stained with DNA dye (green/SYTO13) and isotype control antibodies for H3Cit and NE. Scale bar, 10 μm. (G) Quantification of NETs released by TNF-α–primed human neutrophils stimulated with plasma of non-SCD individuals (gray circle, n = 3), steady-state SCD patients (yellow circle, n = 7), and crisis SCD patients (red circle, n = 8; mean ± SEM, *P < .05, **P < .01).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/123/24/10.1182_blood-2013-10-529982/4/m_3818f3.jpeg?Expires=1769096726&Signature=NANRocFsy9pJRgXMCQ45mZqrxmhg4EEgHu0Zj5GrZs0qnffugu~F6d1BDsNIYa99zgfCDd8h3ZmXhPHB90L4UUTJ~vIrc4ae8oVLqP0w0DnDYxUd2wZQVO0tMqDArppmOWBmnt5uppoz1WpVU8xBpmgbGGRB~c4WUqODsOul~lQN-AF3BavvnTOaNDouGYe~6HUfDTJw3RIH5XOVdhk3073~TNRwE2QIpj9gOtE1Ycimcu78ypPh-3BVsXdJaXr6UmCLA2imGpf9Sm3vfVBoYJWQpkHgpJ6oo8hXscIPJnD~5bft0xx3S1-jQ~KoEBinOK9wOAwtGSn0~t-k5alXgA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. Heme stimulates NET formation in neutrophils in vivo. (A) Quantification of plasma heme concentrations of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice pretreated with vehicle (gray circle, n = 8) or heme (red circle, n = 11) (mean ± SEM, ****P < .0001). (B) Quantification of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice, vehicle pretreated (gray bar, n = 4) or heme pretreated (red bar, n = 6). Results presented are the average values of independent experiments with sex- and age-matched mice (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (C) Representative histological images of NETs in the lungs of heme pretreated-, TNF-α–stimulated SA mice (arrows indicate NETs). Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Representative immunofluorescence images of the lung sections of heme pretreated-, TNF-α–stimulated SA mice showing colocalization of extracellular DNA (green/SYTO13) and NE (red/Alexa Fluor 568, i-ii) or H3Cit (red/Alexa Fluor 568, iii-iv). CD31 (blue/Alexa Fluor 647) labeled the endothelial cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Quantification of NET biomarkers, plasma DNA (left), and plasma nucleosome (right) of TNF-α–challenged SA mice, vehicle pretreated (gray circle, n = 7) or heme pretreated (red circle, n = 6) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], **P < .01). (F) Quantification of plasma MPO activity of TNF-α–challenged SA mice, vehicle pretreated (gray circle, n = 4) or heme pretreated (red circle, n = 6) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], *P < .05). (G) Decrease in rectal temperature of TNF-α–stimulated SA mice, pretreated with vehicle (gray circle, n = 12) or heme (red circle, n = 12) (mean ± SEM, **P < .01).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/123/24/10.1182_blood-2013-10-529982/4/m_3818f6.jpeg?Expires=1769096726&Signature=W3Egj5OscBq6XmJoQ52apvXkLqvUu~w~pmERdrt6g6anDnkniOcrezvqQkyg8~CbgCWxP3aZp3R3UdivURX~-lx1mnEWOU6I7fHG0yPc7CvTzoqmx8VwrhMpzXeJ-ZzKQ7Bgs59jATt0MvT866eqqOkejGZxET480AxJSqDPgzf3wMkUNi5wElxeXlkadPaO2MI7p2khAgLcX-fMIVrLd~Wn4GNfLASNRO2xkNUtqS6mzxQUqN5tLBln5xCMNN9QV-wX5bmpCb3c5aS4KGdIH393q0IHO2siskUSZlyhaPnQ8Fz1KR9jEIZ62cJ-c0zNtdPuk3TSIM8hxqCRbkv-YA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 7. Hemopexin infusion decreases NETs in TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice and protects SCD mice from NET-associated hypothermia. (A) Quantification of plasma heme concentrations of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, vehicle pretreated (white circle, n = 13) or Hx pretreated (gray circle, n = 13) (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (B) Quantification of NETs in the lungs of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, vehicle pretreated (white bar, n = 6) or Hx pretreated (gray bar, n = 10). Results presented are the average values of independent experiments with sex- and age-matched mice (mean ± SEM, **P < .01). (C) Quantification of NET biomarkers, plasma DNA (left) and plasma nucleosome (right), from TNF-α–challenged SCD mice, vehicle pretreated (white circle, n = 14) or Hx pretreated (gray circle, n = 10) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], **P < .01). (D) Quantification of plasma MPO activity of TNF-α–challenged SCD mice, vehicle pretreated (white circle, n = 6) or Hx pretreated (gray circle, n = 6) (Mann-Whitney test, median [IQR], **P < .01). (E) Decrease in rectal temperature of TNF-α–stimulated SCD mice, pretreated with vehicle (white circle, n = 13) or Hx (gray circle, n = 13; mean ± SEM, *P < .05).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/123/24/10.1182_blood-2013-10-529982/4/m_3818f7.jpeg?Expires=1769096726&Signature=NIVDo6yqDhzbTslHpTIiRfrHZZ63pgsAZchXFvDWf3lkNmxRlG6vf1ZmPSdJ6vb4lMH0JRS8mngla-2IlGmif22SkvRD3~IV5NqeIwsCZqnMm6eMo~ekRiN7H5cdyIpUtj7-cJVBIhkpGBQREa49bjqYT2s1G3gEgJzsfKmMxwPTlLa1ZmzNCunleBnye6mVPlKbFLkoj9ZiQtBuMQYBNVbRw~aBYN-vTATua4dnne7RxJYtgGrk2irzpoHpxLkLV6UmOePzTWQXU~gO0AMFyXDgdhJM5GjK~e68tJDftMUM5BYzKLjCFvv3FpZ62ZHY~GLilmQ8ZLUy5044jIYrgQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal