Key Points

Hif-2α–dependent signaling is dispensable for steady-state multilineage hematopoiesis.

Hif-2α is not essential for HSC self-renewal.

Abstract

Local hypoxia in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niches is thought to regulate HSC functions. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (Hif-1) and Hif-2 are key mediators of cellular responses to hypoxia. Although oxygen-regulated α-subunits of Hifs, namely Hif-1α and Hif-2α, are closely related, they play overlapping and also distinct functions in nonhematopoietic tissues. Although Hif-1α–deficient HSCs lose their activity on serial transplantation, the role for Hif-2α in cell-autonomous HSC maintenance remains unknown. Here, we demonstrate that constitutive or inducible hematopoiesis-specific Hif-2α deletion does not affect HSC numbers and steady-state hematopoiesis. Furthermore, using serial transplantations and 5-fluorouracil treatment, we demonstrate that HSCs do not require Hif-2α to self-renew and recover after hematopoietic injury. Finally, we show that Hif-1α deletion has no major impact on steady-state maintenance of Hif-2α–deficient HSCs and their ability to repopulate primary recipients, indicating that Hif-1α expression does not account for normal behavior of Hif-2α–deficient HSCs.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) reside in the hypoxic bone marrow (BM) microenvironment, which modulates metabolism of HSCs and is ultimately important for HSC maintenance.1,2 Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (Hif-1) and Hif-2 are key mediators of cellular responses to hypoxia and regulate gene expression to facilitate adaptation to hypoxia. Oxygen-regulated α-subunits of Hif-1 and Hif-2, namely Hif-1α and Hif-2α, are paralogues that have common and also distinct functions during responses to hypoxia.3 Both Hif-1α and Hif-2α transcripts are present at higher levels in HSCs compared with primitive progenitor cell populations.4 Although several studies established the essential role for Hif-1α in HSC functions,4-7 the cell-autonomous role for Hif-2α in HSC maintenance remains unclear. Here, we demonstrate that HSCs do not require Hif-2α to self-renew and sustain long-term multilineage hematopoiesis and that additional deletion of Hif-1α has no impact on Hif-2α–deficient HSC functions.

Materials and methods

Mice

Hif-1αfl/fl, Hif-2αfl/fl, Mx1-Cre, and Vav-iCre mice have been described previously.8-11 Sex-matched mice, 9 to 12 weeks old, were used for all analyses of steady-state hematopoiesis. Animal experiments were authorized by UK Home Office.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis

Transplantation assays

All donor mice were CD45.2+. For HSC transplantations, 100 Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ (LSK)CD48−CD150+ HSCs sorted from donor BM were transplanted together with 200 000 CD45.1+ BM cells. For secondary transplantations, we injected 2000 CD45.2+ LSK cells (sorted from BM of primary recipients) together with 200 000 CD45.1+ BM cells. To delete floxed alleles, the recipients received 6 doses of poly(I)-poly(C) (pIpC; 0.3 mg per dose) 8 weeks after transplantation.9

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using 2-tailed Student t tests assuming unequal variance.

Results and discussion

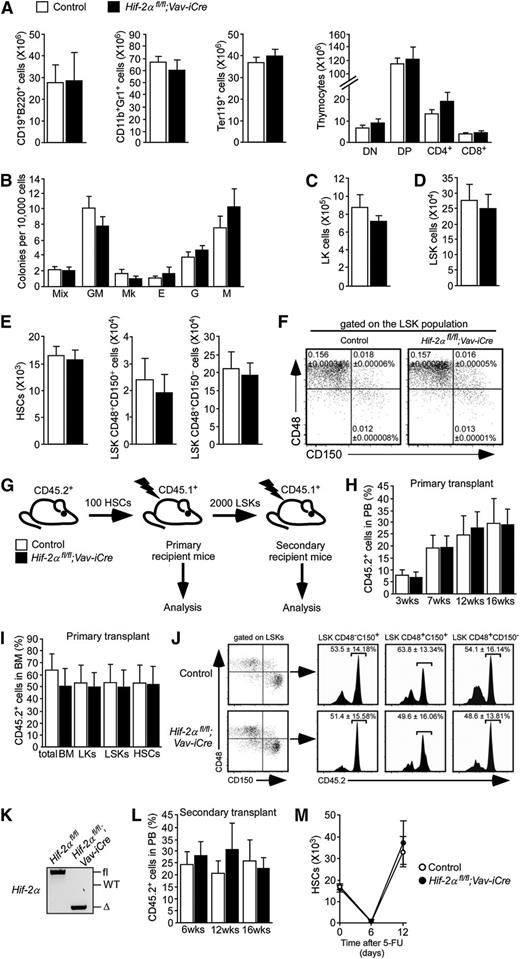

Although Hif-2α is required for hematopoiesis in a noncell autonomous manner,12,13 its role in cell-autonomous HSC maintenance remains unknown. To address this, we deleted Hif-2α specifically in the hematopoietic system using Vav-iCre. Vav-iCre mice11 constitutively express the codon-improved Cre (iCre)14 driven by the Vav regulatory elements,15 resulting in hematopoietic-specific gene deletion shortly after the emergence of definitive HSCs16 and ensuring recombination in all HSCs.17 We bred Hif-2αfl/fl mice (in which exon 2, encoding the basic helix-loop-helix domain, is flanked by loxP sites)8,12,18 to Vav-iCre mice.10,11 We found that Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice (which lack wild-type Hif-2α transcript in their hematopoietic cells; supplemental Figure 1) were born at normal Mendelian ratios and matured to adulthood without obvious phenotypes (results not shown). Immunophenotypic analyses of Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice revealed normal numbers of B-lymphoid, myeloid, and erythroid cells in the BM and unaffected numbers of thymic T cells (Figure 1A). BM cells from Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice efficiently generated colonies in methylcellulose and had comparable lineage differentiation potential (Figure 1B). Concordantly, the 2 cohorts of mice had similar numbers of Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− (LK) myeloid progenitor cells and LSK stem and primitive progenitor cells (Figure 1C-D). The analysis of the BM LSK compartment of Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice using CD150 and CD48 markers revealed no statistically significant difference in total numbers (Figure 1E) and frequencies (Figure 1F) of LSKCD48−CD150+ HSCs and primitive progenitors (LSKCD48+CD150+ and LSKCD48+CD150− cells) between the 2 groups of mice. Subfractionation of the LSK compartment on the basis of CD34 expression confirmed that frequencies and total numbers of LSKCD34− HSCs and LSKCD34+ cells (containing short-term HSCs and multipotent progenitors19 ) were not significantly different between Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice (supplemental Figure 2A-B). These experiments revealed that Hif-2α is dispensable for steady-state HSC maintenance and multilineage hematopoiesis.

Conditional deletion of Hif-2α specifically within the hematopoietic system has no major impact on steady-state HSC maintenance and posttransplantation self-renewal. (A) Total numbers (per 2 femurs and 2 tibias) of BM B-lymphoid (CD19+B220+), myeloid (CD11b+Gr1+), and erythroid (Ter119+) cells and thymocytes from Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice (n = 4) and control mice (Vav-iCre–negative; n = 6). Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Analyses shown in panels A-F were performed on sex-matched 9- to 12-week-old mice. (B) Colony-forming cell (CFC) assay using M3434 media (StemCell Technologies) was performed on total BM cells from Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice. Colony-forming units (CFUs) of granulocytes, erythroid cells, macrophages, and megakaryocytes (Mix); granulocytic-macrophagic CFU (GM); megakaryocytic CFU (Mk); erythroid burst-forming units (E); granulocytic CFU (G); and macrophagic CFU (M) colonies were counted and scored 10 days after initial plating (mean ± SEM; n = 6 mice per group). This CFC assay was repeated in an additional 2 independent experiments. (C-D) Total numbers of LK and LSK cells in the BM of Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice (n = 4) and control mice (n = 5). Data are mean ± SEM. (E) Total numbers of HSCs and primitive progenitor cell populations from Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice (n = 4) and control mice (n = 5). Data are mean ± SEM. (F) Representative dot plots indicating frequencies of HSCs (LSKCD48−CD150+ cells) and primitive progenitors (LSKCD48+CD150+ and LSKCD48+CD150− cells) from Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice (n = 4) and control mice (n = 5). Values are means ± SEM. (G) Experimental design of serial transplantation experiments. Lethally irradiated B6.SJL primary recipient mice were transplanted with 100 CD45.2+ HSCs from Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice or control mice together with 200 000 cells from WT CD45.1+ unfractionated BM. LSK cells from primary recipients were then sorted 16 weeks after transplantation and transplanted into lethally irradiated secondary recipient mice. (H) Peripheral blood (PB) chimerism (percentage of CD45.2+ cells in PB) in primary recipients of control and Hif-2α–deficient HSCs at indicated time points after transplantation. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5 per group). The data are representative of 3 independent transplantation experiments. (I) Frequencies of CD45.2+ cells in BM mononuclear cells (BM) and LK, LSK, and HSC compartments of the primary recipient mice at 16 weeks after transplantation. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5 per group). The data are representative of 3 independent transplantation experiments. (J) FACS plots showing the percentage of CD45.2+ cells in LSKCD48−CD150+ HSCs, LSKCD48+CD150+ and LSKCD48+CD150− cell fractions of the primary recipient mice. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5 per group). The data are representative of 3 independent transplantation experiments. (K) Representative gel showing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of genomic DNA from CD45.2+ fraction of the BM from primary recipient mice transplanted with Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre cells and control cells (as shown in panels G-J). Samples were taken 16 weeks after transplantation before the secondary transplantation. (L) Secondary transplantation experiment. LSK cells from primary recipients of Hif-2α–deficient and control cells were sorted 16 weeks after transplantation and transplanted (2000 cells/mouse) into lethally irradiated secondary recipient mice (together with 200 000 WT support BM cells). Chimerism was determined in PB 16 weeks after transplantation. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 6 per group). The data are representative of 2 independent transplantation experiments. (M) HSC numbers in Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice after injection with 5-FU. Ten-week-old Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice received a single intraperitoneal dose of 5-FU (150 mg/kg). LSKCD48−CD150+ HSC numbers were determined at indicated time points. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3-5 mice per group per time point). Δ, excised allele; DN, CD4−CD8− double-negative cells; DP, CD4+CD8+ double-positive cells; fl, undeleted conditional allele; WT, wild-type allele.

Conditional deletion of Hif-2α specifically within the hematopoietic system has no major impact on steady-state HSC maintenance and posttransplantation self-renewal. (A) Total numbers (per 2 femurs and 2 tibias) of BM B-lymphoid (CD19+B220+), myeloid (CD11b+Gr1+), and erythroid (Ter119+) cells and thymocytes from Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice (n = 4) and control mice (Vav-iCre–negative; n = 6). Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Analyses shown in panels A-F were performed on sex-matched 9- to 12-week-old mice. (B) Colony-forming cell (CFC) assay using M3434 media (StemCell Technologies) was performed on total BM cells from Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice. Colony-forming units (CFUs) of granulocytes, erythroid cells, macrophages, and megakaryocytes (Mix); granulocytic-macrophagic CFU (GM); megakaryocytic CFU (Mk); erythroid burst-forming units (E); granulocytic CFU (G); and macrophagic CFU (M) colonies were counted and scored 10 days after initial plating (mean ± SEM; n = 6 mice per group). This CFC assay was repeated in an additional 2 independent experiments. (C-D) Total numbers of LK and LSK cells in the BM of Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice (n = 4) and control mice (n = 5). Data are mean ± SEM. (E) Total numbers of HSCs and primitive progenitor cell populations from Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice (n = 4) and control mice (n = 5). Data are mean ± SEM. (F) Representative dot plots indicating frequencies of HSCs (LSKCD48−CD150+ cells) and primitive progenitors (LSKCD48+CD150+ and LSKCD48+CD150− cells) from Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice (n = 4) and control mice (n = 5). Values are means ± SEM. (G) Experimental design of serial transplantation experiments. Lethally irradiated B6.SJL primary recipient mice were transplanted with 100 CD45.2+ HSCs from Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice or control mice together with 200 000 cells from WT CD45.1+ unfractionated BM. LSK cells from primary recipients were then sorted 16 weeks after transplantation and transplanted into lethally irradiated secondary recipient mice. (H) Peripheral blood (PB) chimerism (percentage of CD45.2+ cells in PB) in primary recipients of control and Hif-2α–deficient HSCs at indicated time points after transplantation. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5 per group). The data are representative of 3 independent transplantation experiments. (I) Frequencies of CD45.2+ cells in BM mononuclear cells (BM) and LK, LSK, and HSC compartments of the primary recipient mice at 16 weeks after transplantation. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5 per group). The data are representative of 3 independent transplantation experiments. (J) FACS plots showing the percentage of CD45.2+ cells in LSKCD48−CD150+ HSCs, LSKCD48+CD150+ and LSKCD48+CD150− cell fractions of the primary recipient mice. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5 per group). The data are representative of 3 independent transplantation experiments. (K) Representative gel showing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of genomic DNA from CD45.2+ fraction of the BM from primary recipient mice transplanted with Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre cells and control cells (as shown in panels G-J). Samples were taken 16 weeks after transplantation before the secondary transplantation. (L) Secondary transplantation experiment. LSK cells from primary recipients of Hif-2α–deficient and control cells were sorted 16 weeks after transplantation and transplanted (2000 cells/mouse) into lethally irradiated secondary recipient mice (together with 200 000 WT support BM cells). Chimerism was determined in PB 16 weeks after transplantation. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 6 per group). The data are representative of 2 independent transplantation experiments. (M) HSC numbers in Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice after injection with 5-FU. Ten-week-old Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice received a single intraperitoneal dose of 5-FU (150 mg/kg). LSKCD48−CD150+ HSC numbers were determined at indicated time points. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3-5 mice per group per time point). Δ, excised allele; DN, CD4−CD8− double-negative cells; DP, CD4+CD8+ double-positive cells; fl, undeleted conditional allele; WT, wild-type allele.

To investigate the self-renewal capacity of Hif-2α–deficient HSCs, we conducted serial transplantation experiments. We transplanted CD45.2+LSKCD48−CD150+ HSCs sorted from Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice together with 200 000 CD45.1+ wild-type BM cells into primary CD45.1+ recipients (Figure 1G). HSCs of both genotypes efficiently reconstituted long-term hematopoiesis (Figure 1H; supplemental Figure 3) and equally contributed to BM HSC and primitive cell compartments of the recipient mice (Figure 1I-J). Having confirmed the efficient Hif-2α excision in donor-derived Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre cells in primary recipients (Figure 1K), we sorted LSKs from primary recipients and transplanted them into secondary recipients. Hif-2α–deficient LSKs sustained long-term reconstitution in secondary recipients comparably to control LSKs (Figure 1L). To test the role for Hif-2α in HSC stress responses, we treated adult Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). We observed a transient reduction of HSC numbers in Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice followed by efficient recovery of HSCs of both genotypes (Figure 1M). Therefore, Hif-2α is dispensable for posttransplantation HSC self-renewal and their ability to respond to hematopoietic stress.

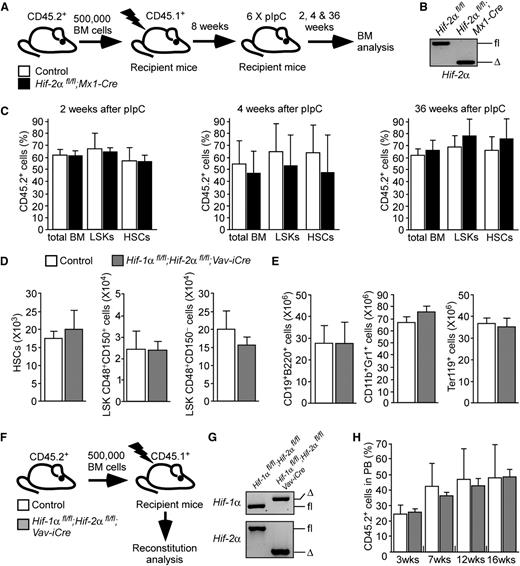

Because Vav-iCre recombines during embryogenesis, HSCs in Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice may activate compensatory mechanisms that bypass Hif-2α deficiency. To rule this out, we examined HSC maintenance following acute Hif-2α deletion. We generated Hif-2αfl/fl;Mx1-Cre mice in which efficient recombination is induced by treatment with pIpC.9,20 We mixed CD45.2+ BM cells from untreated Hif-2αfl/fl;Mx1-Cre or control mice with CD45.1+ BM cells and transplanted them into recipients (Figure 2A). At 8 weeks after transplantation, the mice received 6 doses of pIpC resulting in efficient Hif-2α deletion in donor-derived CD45.2+ cells (Figure 2B). The contribution of CD45.2+ cells to the stem and progenitor cell compartments of the recipients was measured 2, 4, and 36 weeks after pIpC treatment (Figure 2C). The percentage of CD45.2+ cells in total BM, LSK cell compartments, and in HSCs of the recipients was similar regardless of the genotype of transplanted CD45.2+ cells.

Acute ablation of Hif-2α has no impact on survival and function of HSCs (A) Experimental design. BM cells from untreated Hif-2αfl/fl;Mx1-Cre mice and control mice (without Mx1-Cre) were mixed with CD45.1+ WT competitor BM and transplanted into lethally irradiated recipients. After confirmation of equal multilineage reconstitution 8 weeks after transplantation, the mice were treated with 6 doses of pIpC and were analyzed 2, 4, and 36 weeks after the last pIpC administration. (B) Representative gel showing PCR amplification of genomic DNA from donor-derived CD45.2+ fraction of the PB from the pIpC-treated recipient mice shown. The analysis was performed 2 weeks after the last dose of pIpC. (C) The graphs show the percentage of CD45.2+ donor-derived cells measured in total BM, BM LSK, and HSC compartments of the recipients. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 7 per group per time point. The data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (D) Total numbers of HSCs and primitive progenitor cell populations from 10- to 12-week-old Hif-1αfl/fl;Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice (n = 6) and control mice (Vav-iCre–negative; n = 5). Data are mean ± SEM. (E) Total numbers (per 2 femurs and 2 tibias) of BM B-lymphoid (CD19+B220+), myeloid (CD11b+Gr1+), and erythroid (Ter119+) cells from Hif-1αfl/fl;Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice (n = 4) and control mice (n = 6). Data are mean ± SEM. (F) Experimental design. Lethally irradiated recipients were transplanted with 500 000 CD45.2+ BM mononuclear cells from Hif-1αfl/fl;Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice or control mice (Hif-1αfl/fl;Hif-2αfl/fl without Vav-iCre) together with 500 000 BM mononuclear cells from WT CD45.1+ mice. Gene deletion was confirmed 16 weeks after transplantation (G). Chimerism analysis was performed 3, 7, 12, and 16 weeks after transplantation (H; supplemental Figure 4). (G) Representative gel showing PCR amplification of genomic DNA from CD45.2+ fraction of the BM from recipient mice transplanted with Hif-1αfl/fl;Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre cells and control cells. Samples were taken 16 weeks after transplantation. (H) PB chimerism in recipients of control cells and Hif-1α/Hif-2α–deficient BM cells. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3-5 per group). Representative data of 3 independent transplantation experiments are shown. Δ, excised allele; fl, undeleted conditional allele; WT, wild-type allele.

Acute ablation of Hif-2α has no impact on survival and function of HSCs (A) Experimental design. BM cells from untreated Hif-2αfl/fl;Mx1-Cre mice and control mice (without Mx1-Cre) were mixed with CD45.1+ WT competitor BM and transplanted into lethally irradiated recipients. After confirmation of equal multilineage reconstitution 8 weeks after transplantation, the mice were treated with 6 doses of pIpC and were analyzed 2, 4, and 36 weeks after the last pIpC administration. (B) Representative gel showing PCR amplification of genomic DNA from donor-derived CD45.2+ fraction of the PB from the pIpC-treated recipient mice shown. The analysis was performed 2 weeks after the last dose of pIpC. (C) The graphs show the percentage of CD45.2+ donor-derived cells measured in total BM, BM LSK, and HSC compartments of the recipients. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 7 per group per time point. The data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (D) Total numbers of HSCs and primitive progenitor cell populations from 10- to 12-week-old Hif-1αfl/fl;Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice (n = 6) and control mice (Vav-iCre–negative; n = 5). Data are mean ± SEM. (E) Total numbers (per 2 femurs and 2 tibias) of BM B-lymphoid (CD19+B220+), myeloid (CD11b+Gr1+), and erythroid (Ter119+) cells from Hif-1αfl/fl;Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice (n = 4) and control mice (n = 6). Data are mean ± SEM. (F) Experimental design. Lethally irradiated recipients were transplanted with 500 000 CD45.2+ BM mononuclear cells from Hif-1αfl/fl;Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice or control mice (Hif-1αfl/fl;Hif-2αfl/fl without Vav-iCre) together with 500 000 BM mononuclear cells from WT CD45.1+ mice. Gene deletion was confirmed 16 weeks after transplantation (G). Chimerism analysis was performed 3, 7, 12, and 16 weeks after transplantation (H; supplemental Figure 4). (G) Representative gel showing PCR amplification of genomic DNA from CD45.2+ fraction of the BM from recipient mice transplanted with Hif-1αfl/fl;Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre cells and control cells. Samples were taken 16 weeks after transplantation. (H) PB chimerism in recipients of control cells and Hif-1α/Hif-2α–deficient BM cells. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3-5 per group). Representative data of 3 independent transplantation experiments are shown. Δ, excised allele; fl, undeleted conditional allele; WT, wild-type allele.

Next, Hif-2α–deficient and control LSK cells from primary recipients were transplanted to secondary recipients. Chimerism analysis at 24 weeks after transplantation showed that cells of both genotypes efficiently repopulated secondary recipients (results not shown). Therefore, acute deletion of Hif-2α has no impact on the survival of HSCs and their long-term functions.

Finally, we asked whether maintenance of Hif-2α–deficient HSCs can be compromised by additional Hif-1α deletion. We generated adult Hif-1αfl/fl;Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice and found that they had comparable numbers of BM LSKCD48−CD150+ HSCs, LSKCD48+CD150+, and LSKCD48+CD150− cells (Figure 2D), and mature hematopoietic cells (Figure 2E), indicating that Hif-1α/Hif-2α–deficient HSCs survive and sustain steady-state hematopoiesis. To test the long-term reconstitution capacity of Hif-1α/Hif-2α–deficient HSCs, we transplanted BM cells from Hif-1αfl/fl;Hif-2αfl/fl;Vav-iCre mice and control mice into recipients (Figure 2F) and found that Hif-1α and Hif-2α deficiency (Figure 2G) had no major impact on short-term or long-term reconstitution of recipients (Figure 2H; supplemental Figure 4). Therefore, the ability of Hif-2α–deficient HSCs to sustain steady-state hematopoiesis and repopulate primary recipients is not compromised by additional Hif-1α deletion, indicating that compensatory Hif-1α expression is not predominantly responsible for unperturbed hematopoiesis in the absence of Hif-2α.

Hypoxia within the BM microenvironment is thought to play important roles in the maintenance of the metabolic state of HSCs and hypoxia, and its signaling pathways are implicated in HSC functions.1,2 Hif-1α deficiency does not severely perturb steady-state hematopoiesis and the ability of HSCs to reconstitute multilineage hematopoiesis in primary recipients, but this deficiency results in the loss of HSC activity after cumulative stress, such as serial transplantation.4 Here, we demonstrated that Hif-2α–deficient HSCs sustain steady-state hematopoiesis and efficiently reconstitute multilineage hematopoiesis in serial transplantation assays. We also showed that additional deletion of Hif-1α does not affect steady-state maintenance of Hif-2α–deficient HSCs and their ability to reconstitute hematopoiesis in primary recipients. Further understanding of the detailed functional relationship between these paralogous Hif-α isoforms will be essential to provide important insights into the complexity of Hif-dependent signaling in HSC functions.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Celeste Simon and Randall Johnson for providing Hif-2αfl/fland Hif-1αfl/fl mice, respectively.

K.R.K. is a Cancer Research UK Senior Cancer Research Fellow. This work was supported by a Senior Cancer Research Fellowship from Cancer Research UK (C29967/A14633) (K.R.K.), grants from Leukaemia & Lymphoma Research (08037, 10030, 11047, 11041) (K.R.K.), Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund (KKL506) (K.R.K.), the Royal Society (2010R1) (K.R.K.), the National Health Service Greater Glasgow and Clyde Endowment Fund (K.R.K.), and the Cancer Research UK programme grant (A11008) (T.L.H.).

Authorship

Contribution: K.R.K. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript; T.L.H., T.E., P.J.R., and P.P. helped with experimental designs; A.V.G. and C. Subramani performed FACS, transplantations, and data analysis; and A.A.-D., M.V., G.S., D.G., C. Sepulveda, and K.D. assisted with mouse husbandry, genotyping and FACS.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kamil R. Kranc, MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine, 5 Little France Dr, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH16 4UU, United Kingdom; e-mail: kamil.kranc@ed.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal