Key Points

In Bdkrb2−/− mice, compensatory Mas and AT2R overexpression elevates NO and PGI2 to prolong bleeding times and delay arterial thrombosis.

This NO and PGI2 elevation attenuates platelet integrin-dependent spreading and GPVI responses without altering thrombin or ADP activation.

Abstract

Bradykinin B2 receptor–deleted mice (Bdkrb2−/−) have delayed carotid artery thrombosis times and prolonged tail bleeding time resulting from elevated angiotensin II (AngII) and angiotensin receptor 2 (AT2R) producing increased plasma nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin. Bdkrb2−/− also have elevated plasma angiotensin-(1-7) and messenger RNA and protein for its receptor Mas. Blockade of Mas with its antagonist A-779 in Bdkrb2−/− shortens thrombosis times (58 ± 4 minutes to 38 ± 4 minutes) and bleeding times (170 ± 13 seconds to 88 ± 8 seconds) and lowers plasma nitrate (22 ± 4 μM to 15 ± 5 μM), and 6-keto-PGF1α (259 ± 103 pg/mL to 132 ± 58 pg/mL). Bdkrb2−/− platelets express increased NO, guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate, and cyclic adenosine monophosphate with reduced spreading on collagen, collagen peptide GFOGER, or fibrinogen. In vivo A-779 or combined L-NAME and nimesulide treatment corrects it. Bdkrb2−/− platelets have reduced collagen-related peptide–induced integrin α2bβ3 activation and P-selectin expression that are partially corrected by in vivo A-779, nimesulide, or L-NAME. Bone marrow transplantations show that the platelet phenotype and thrombosis time depends on the host rather than donor bone marrow progenitors. Transplantation of wild-type bone marrow into Bdkrb2−/− hosts produces platelets with a spreading defect and delayed thrombosis times. In Bdkrb2−/−, combined AT2R and Mas overexpression produce elevated plasma prostacyclin and NO leading to acquired platelet function defects and thrombosis delay.

Introduction

Major hypertension clinical trials show that treatment with various antihypertensive medications leads to ∼20% reduction in myocardial infarction, stroke, and the need for coronary revacularization.1,2 The mechanisms for the observed arterial thromboprotection are not completely known. Regulation of hypertension reduces shear and vascular injury. Other mechanism(s) through the renin angiotensin system (RAS) may influence arterial thrombosis risk as well. Previously we observed that mice (Bdkrb2−/−) lacking the bradykinin B2 receptor (B2R) are protected from arterial thrombosis by a paradoxical mechanism that includes increased plasma angiotensin II (AngII) and renal angiotensin receptor 2 (AT2R).3 In the Bdkrb2−/−, there is increased angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE or kininase II) activity that converts angiotensin I to AngII.3,4 The evidence for increased ACE activity is the finding that Bdkrb2−/− plasma has elevated bradykinin 1-5, the ACE breakdown product of bradykinin.3,5,6 Bdkrb2−/− mice also have increased AT2R messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein.3,7 Because AngII binds to angiotensin receptor 1 or AT2R with equal affinity, the receptor more highly expressed determines the dominant phenotype. AngII binding to the AT2R increases nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin.3,8 Bdkrb2−/− mice have long tail bleeding times, presumably because of increased plasma NO and prostacyclin.3 If AT2R, NO synthase, or cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) is blocked with a specific inhibitor, respectively, the prolonged thrombosis and bleeding times in Bdkrb2−/− normalize.3 Because Bdkrb2−/− mice are not constitutively hypertensive, the pathways that protect them from thrombosis indicate mechanisms for arterial thrombosis risk modulation independent of blood pressure lowering.9

New investigations indicate that the lowering of plasma AngII alone is not sufficient to correct the thrombosis protection in Bdkrb2−/−. This finding suggests an additional thromboprotective mechanism in Bdkrb2−/−. Further, the mechanism(s) for the long bleeding time in Bdkrb2−/− mice has not been elucidated.3 The present investigation indicates that a second receptor of the RAS, Mas, contributes to thrombosis protection in Bdkrb2−/− also through elevation of plasma NO and prostacyclin. Additionally, platelet inhibition and thrombosis protection in Bdkrb2−/− is produced in part by acquired defects in integrin-mediated spreading and glycoprotein VI (GPVI) activation. Because B2R, AT2R, and Mas are vascular and renal receptors, modulation of these components has potential to influence arterial thrombosis risk.10-12

Methods

Materials

Human α-thrombin (3000 U/mg) and γ-thrombin were purchased from Haematologic Technologies. The Mas receptor antagonist A-779 [H-Asp-Arg-Val-Tyr-Ile-His-D-Ala-OH (D-Ala7-angiotensin 1-7)] was purchased from Bachem. Antibodies to AT2R and Mas were purchased from Santa Cruz Biochemicals and Nova Biologicals LLC, respectively. DEA NONOate (diethylamine NONOate) and carbaprostacyclin were purchased from Cayman Chemical. Rat antibodies to murine P-selectin (Wug.E9), the activated epitope of murine α2bβ3 integrin (JON/A), and murine platelet GPVI (JAQ-1) were purchased from Emfret Analytics. Convulxin was purchased from Alexis. Collagen-related peptide (CRP) was generously provided by Dr Deborah Newman, Blood Center of Wisconsin (Milwaukee, WI). Losartan, telmisartan, and IBMX [1-methyl-3-(2-methylpropyl)-7H-purine-2,6-dione] were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Peptide GFOGER was generously provided by Drs Yunmei Wang and Daniel I. Simon, Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland, OH).13

Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the principles of Laboratory and Animal Care established by the National Society for Medical Research and were approved by the Case Western Reserve University Committee on Use and Care of Animals. All studies were performed on mice 8 to 12 weeks of age. Bdkrb2−/−, strain name B6/129S7-Bdkrb2tm1Jfh and their wild-type, B6129SF2/J mice (Bdkrb2+/+), originally were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), but then mated to produce heterozygous animals from which wild-type and gene-deleted colonies were rederived.3

Assays

AngII antigen was determined as previously reported.3 Angiotensin-(1-7) [Ang-(1-7)] was measured in the Hypertension & Vascular Research Center, Wake Forest University Health Science Center (Winston-Salem, NC). The stable analog of prostacyclin, 6-keto-prostaglandin F1α (6-keto-PGF1α), and serum nitrite/nitrate were measured in mouse plasma according to the manufacturer's specifications (Cayman Chemical).3

Data analysis

All data are presented as means of at least triplicate determinations and are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise indicated in the text. One-way analysis of variance was performed for comparison among 3 or more related groups with a Bonferroni correction. Two-way analysis of variance was applied to determine changes of several parameters between 2 groups. Significance between the 2 groups was determined by the unpaired, nonparametric 2-tailed t test. P values < .05 were considered significant. In each experiment, the statistical analysis used is reported in the figures.

Detailed platelet studies and other methods are given in the supplemental Methods.

Results

Characterization of Ang-(1-7) and Mas of the renin angiotensin system in Bdkrb2−/− mice

In our previous investigation, we observed that an ACE inhibitor, ramipril, and an antagonist to the AT2R, PD123319, independently corrected the lengthened thrombosis time in Bdkrb2−/− mice.3 As a negative control, we examined if losartan, an angiotensin receptor 1 antagonist, had any influence. As expected, losartan had no influence on the time to thrombosis on the Rose Bengal assay in Bdkrb2−/− (61 ± 5 minutes, n = 5, vs untreated Bdkrb2−/− 71 ± 3 minutes, n = 10) (P = .13) (Figure 1A). However, to our surprise, plasma AngII levels of losartan-treated Bdkrb2−/− (40 ± 30 pg/mL, n = 4) were significantly lower (P < .022) than untreated Bdkrb2−/− mice (258 ± 144 pg/mL, n = 5) (Figure 1B). Losartan treatment did not lower AngII levels in wild-type mice (45 ± 6 pg/mL, n = 4 vs untreated mice 40 ± 20 pg/mL, n = 5)(P = .61) (Figure 1B). Our previous understanding of the mechanism for thrombosis protection in Bdkrb2−/− mice required elevated serum AngII and its receptor AT2R.3 These unexpected findings with losartan suggested that an additional, previously unappreciated thromboprotective mechanism(s) was operative.3

Characterization of Mas receptor in the Bdkrb2−/− mice. (A) The influence of losartan on the thrombosis time in the carotid artery Rose Bengal model in Bdkrb2−/− mice. Untreated (n = 10) or losartan-treated (10 mg/kg per day in drinking water) (n = 5) Bdkrb2+/+ or untreated (n = 10) or losartan-treated (n = 5) Bdkrb2−/− mice were compared on the Rose Bengal assay for carotid artery thrombosis. In all panels, the values shown are mean ± SEM. (B) AngII levels in untreated Bdkrb2+/+ (n = 4) and Bdkrb2−/− (n = 5) or losartan-treated Bdkrb2+/+ (n = 5) and Bdkrb2−/− (n = 4). (C) ACE mRNA levels in untreated or losartan-treated Bdkrb2+/+ and Bdkrb2−/− (n = 4 in each group). (D) Ang-(1-7) concentration in Bdkrb2+/+, Bdkrb2−/−, losartan-treated Bdkrb2+/+, and losartan-treated Bdkrb2−/− (n > 8 in each group). (E) Mas mRNA levels in untreated or losartan-treated Bdkrb2+/+ and Bdkrb2−/− (n = 4 in each group). (F) Immunoblots for renal Mas and AT2R. Kidney lysates from Bdkrb2+/+ and Bdkrb2−/− with equal total protein amounts were immunoblotted with antibody to Mas, kininogen, AT2R, or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), respectively. Kininogen serves as the loading control for Mas because Mas and GAPDH migrate to the same position on the SDS-PAGE. The figure is a representative gel of 4 individual studies of 4 pairs of different renal lysates. (G) Ratio of receptor Mas or AT2R to loading control, respectively, in renal lysate (n = 4 in each group). All data shown are the mean ± SEM. (A–E) Analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance with a Bonferroni correction and were found to be significantly different. P values shown represent an analysis of difference between 2 groups.

Characterization of Mas receptor in the Bdkrb2−/− mice. (A) The influence of losartan on the thrombosis time in the carotid artery Rose Bengal model in Bdkrb2−/− mice. Untreated (n = 10) or losartan-treated (10 mg/kg per day in drinking water) (n = 5) Bdkrb2+/+ or untreated (n = 10) or losartan-treated (n = 5) Bdkrb2−/− mice were compared on the Rose Bengal assay for carotid artery thrombosis. In all panels, the values shown are mean ± SEM. (B) AngII levels in untreated Bdkrb2+/+ (n = 4) and Bdkrb2−/− (n = 5) or losartan-treated Bdkrb2+/+ (n = 5) and Bdkrb2−/− (n = 4). (C) ACE mRNA levels in untreated or losartan-treated Bdkrb2+/+ and Bdkrb2−/− (n = 4 in each group). (D) Ang-(1-7) concentration in Bdkrb2+/+, Bdkrb2−/−, losartan-treated Bdkrb2+/+, and losartan-treated Bdkrb2−/− (n > 8 in each group). (E) Mas mRNA levels in untreated or losartan-treated Bdkrb2+/+ and Bdkrb2−/− (n = 4 in each group). (F) Immunoblots for renal Mas and AT2R. Kidney lysates from Bdkrb2+/+ and Bdkrb2−/− with equal total protein amounts were immunoblotted with antibody to Mas, kininogen, AT2R, or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), respectively. Kininogen serves as the loading control for Mas because Mas and GAPDH migrate to the same position on the SDS-PAGE. The figure is a representative gel of 4 individual studies of 4 pairs of different renal lysates. (G) Ratio of receptor Mas or AT2R to loading control, respectively, in renal lysate (n = 4 in each group). All data shown are the mean ± SEM. (A–E) Analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance with a Bonferroni correction and were found to be significantly different. P values shown represent an analysis of difference between 2 groups.

Because losartan treatment in vivo is known to increase bradykinin levels by reduced ACE metabolism in humans, we determined renal ACE mRNA levels in our animals.14 Losartan treatment significantly decreased renal ACE mRNA in both wild-type (Bdkrb2+/+) (P = .03) and in Bdkrb2−/− mice (P = .017) (Figure 1C). The effect of losartan on renal ACE mRNA is a drug-class specific effect; treatment of Bdkrb2−/− mice with telmisartan, another angiotensin receptor 1 antagonist, also lowered renal ACE mRNA threefold (supplemental Figure 1). These data suggested that losartan treatment lowered AngII levels in Bdkrb2−/− by reducing ACE mRNA.

Because ACE inhibition lowers AngII levels and corrects thrombosis protection in Bdkrb2−/−,3 but angiotensin receptor 1 antagonists lower AngII levels but do not correct thrombosis delay, an additional mechanism(s) for thromboprotection mediated by ACE was sought. Mas is the receptor for Ang-(1-7), a metabolic product of AngII.11 Stimulation of Mas, like the AT2R, results in vasodilation and increased prostacyclin and NO formation.15-17 We determined the levels of Ang-(1-7) in Bdkrb2−/− mice. In the absence or presence of losartan, Bdkrb2−/− mice (18.4 ± 2 pg/mL, n = 8 for untreated and 20.4 ± 1.9 pg/mL, n = 8 for treated) had significantly increased plasma Ang-(1-7) over Bdkrb2+/+ animals (14 ± 0.1 pg/mL, n = 16 for untreated and 12.7 ± 1.6 pg/mL, n = 8 for treated) (P < .05) (Figure 1D). Losartan treatment had no influence on plasma Ang-(1-7) levels. In addition, we next examined if there were changes in the major enzymes, ACE 2 and prolylcarboxypeptidase (PRCP), which produce Ang-(1-7) from AngII.18 Losartan also did not influence ACE2 or PRCP renal mRNA or enzymatic activity in Bdkrb2−/− mice (supplemental Figures 2 and 3). Further, Ang-(1-7) production on Bdkrb2−/− kidney was not different between losartan-treated and untreated samples using 2 different assays (supplemental Figure 3). In sum, these combined studies indicated that lowering of AngII levels by losartan had no influence on plasma Ang-(1-7).

Ang-(1-7) has been proposed as a mediator through which captopril and losartan contribute to thrombosis protection.19 Investigations next sought to determine if the Ang-(1-7) receptor Mas participated in the thrombosis protection seen in Bdkrb2−/− mice. Studies showed that Bdkrb2−/− have approximately twofold increased renal Mas mRNA (P < .017) over wild-type mice (Figure 1E). This result was independent of losartan treatment. Immunoblot studies indicated that there was increased Mas antigen in the Bdkrb2−/− vs wild-type, similar to what we had reported for the AT2R (Figure 1F-G).3 These combined studies suggest that Mas could be an additional receptor contributing to the thrombosis protection in Bdkrb2−/− mice.

Influence of Mas on thrombosis protection in Bdkrb2−/− mice

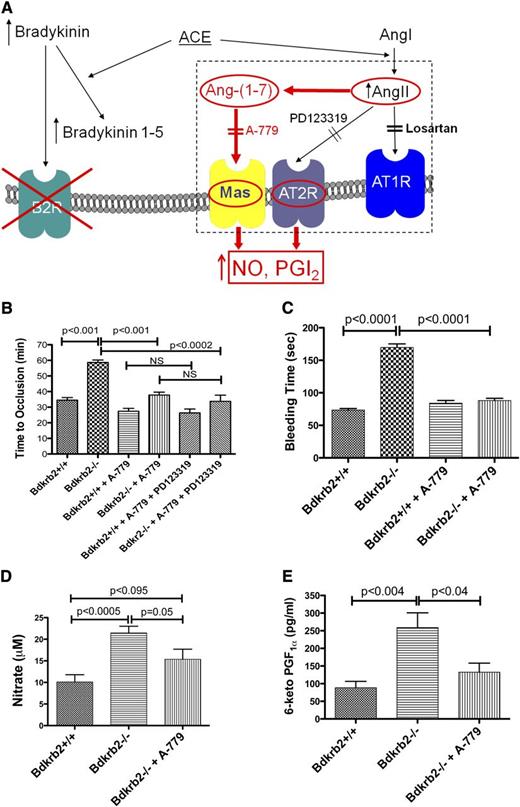

Previous studies showed that treatment of the Bdkrb2−/− mice with an AT2R antagonist, PD123319, alone normalized their thrombosis protection (Figure 2A).3 We now determined if treating Bdkrb2−/− mice with a Mas antagonist, A-779, alone also reduced thrombosis times. In wild-type mice, A-779 treatment shortened the occlusion time from 34 ± 1.7 minutes (n = 6) to 27 ± 1.8 minutes (n = 6) (P < .02) (Figure 2B). In Bdkrb2−/−, A-779 shortened the thrombosis times from 58 ± 2 minutes (n = 5) to 38 ± 2 minutes (n = 4) (P < .0001). When wild-type or Bdkrb2−/− mice were treated with both A-779 and PD123319, there was no further shortening of the occlusion times (Figure 2B). Likewise, A-779 treatment of Bdkrb2−/− also shortened the tail bleeding time from 170 ± 5 seconds (n = 6) to 88 ± 3 seconds (n = 6) (P < .0001) (Figure 2C). Mas contributed to plasma NO and prostacyclin levels. As previously reported, Bdkrb2−/− had twofold increased (P < .0005) plasma nitrate (21.5 ± 1.5 μM, n = 6) compared with wild-type mice (10 ± 2 μM, n = 6) (Figure 2D). When the Bdkrb2−/− were treated with A-779, the plasma nitrate level fell to 15 ± 2 μM, n = 5, a value significantly less (P < .05) than Bdkrb2−/− mice, but not significantly greater than wild-type (P = .092) (Figure 2D). Likewise, Bdkrb2−/− had significantly elevated (P < .004) 6-keto-PGF1α levels (259 ± 42 pg/mL, n = 6) compared with wild-type mice (88 ± 18 pg/ml, n = 6) (Figure 2E).3 When Bdkrb2−/− were treated with A-779, the plasma 6-keto-PGF1α value fell to 132 ± 26 pg/mL, n = 5, a value not significantly different from wild-type (Figure 2E). These combined studies indicated that Mas was an independent regulator of arterial thrombosis risk in Bdkrb2−/−.

The influence of the receptor Mas on thrombosis risk in Bdkrb2−/− mice. (A) Proposed mechanism by which elevation of AngII leads to thromboprotection in Bdkrb2−/− mice. In the absence of the bradykinin B2 receptor, bradykinin is elevated (unpublished data). Increased bradykinin stimulates ACE to degrade it to bradykinin 1-5, which has been demonstrated to be increased in Bdkrb2−/− mice.3 ACE also converts angiotensin I to elevate AngII, which also has been demonstrated in Bdkrb2−/−mice (Figure 1B).3 AngII stimulates an overexpressed AT2R (Figure 1F-G) to produce increased NO and prostacyclin providing thromboprotection.3 The AT2R is blocked by its antagonist PD123319.3 In the present report, we also demonstrate that some AngII is metabolized to Ang-(1-7) (Figure 1D). Plasma Ang-(1-7) levels remain at a higher baseline level in Bdkrb2−/− mice even when losartan lowers AngII levels (Figure 1B-D). Ang-(1-7) binding to its receptor Mas, a G protein–coupled receptor, also stimulates NO and/or prostacyclin production.11,12 In the present report, we propose that blockade of Mas alone with its antagonist A-779 is sufficient to correct the thrombosis protection in Bdkrb2−/− mice and long bleeding time in these animals by reducing NO and prostacyclin elevation. This effect is similar to our previous report in which interruption of only the AT2R by PD123319 corrected their thrombosis protection.3 (B) The influence of the Mas antagonist A-779 on time to thrombosis. Wild-type mice (n = 5) were untreated or treated with A-779 or A-779 and PD123319; Bdkrb2−/−mice were untreated (n = 4) or treated with A-779 or A-779 and PD123319 (n = 6) and the time to carotid artery thrombosis was determined on the Rose Bengal assay. (C) The tail bleeding time was determined in wild-type and Bdkrb2−/− mice untreated or treated with A-779 (n = 6 in each group). (D) Determination of plasma nitrate. Plasma was collected from wild-type (n = 6), Bdkrb2−/− (n = 6), and Bdkrb2−/− treated with A-779 (n = 5). (E) Determination of plasma 6-keto-PGF1α. Plasma was collected from wild-type (n = 6), Bdkrb2−/− (n = 6), and Bdkrb2−/− treated with A-779 (n = 5). (B–E) Analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance show differences among groups. The values shown are mean ± SEM. P values shown represent an analysis of difference between 2 groups.

The influence of the receptor Mas on thrombosis risk in Bdkrb2−/− mice. (A) Proposed mechanism by which elevation of AngII leads to thromboprotection in Bdkrb2−/− mice. In the absence of the bradykinin B2 receptor, bradykinin is elevated (unpublished data). Increased bradykinin stimulates ACE to degrade it to bradykinin 1-5, which has been demonstrated to be increased in Bdkrb2−/− mice.3 ACE also converts angiotensin I to elevate AngII, which also has been demonstrated in Bdkrb2−/−mice (Figure 1B).3 AngII stimulates an overexpressed AT2R (Figure 1F-G) to produce increased NO and prostacyclin providing thromboprotection.3 The AT2R is blocked by its antagonist PD123319.3 In the present report, we also demonstrate that some AngII is metabolized to Ang-(1-7) (Figure 1D). Plasma Ang-(1-7) levels remain at a higher baseline level in Bdkrb2−/− mice even when losartan lowers AngII levels (Figure 1B-D). Ang-(1-7) binding to its receptor Mas, a G protein–coupled receptor, also stimulates NO and/or prostacyclin production.11,12 In the present report, we propose that blockade of Mas alone with its antagonist A-779 is sufficient to correct the thrombosis protection in Bdkrb2−/− mice and long bleeding time in these animals by reducing NO and prostacyclin elevation. This effect is similar to our previous report in which interruption of only the AT2R by PD123319 corrected their thrombosis protection.3 (B) The influence of the Mas antagonist A-779 on time to thrombosis. Wild-type mice (n = 5) were untreated or treated with A-779 or A-779 and PD123319; Bdkrb2−/−mice were untreated (n = 4) or treated with A-779 or A-779 and PD123319 (n = 6) and the time to carotid artery thrombosis was determined on the Rose Bengal assay. (C) The tail bleeding time was determined in wild-type and Bdkrb2−/− mice untreated or treated with A-779 (n = 6 in each group). (D) Determination of plasma nitrate. Plasma was collected from wild-type (n = 6), Bdkrb2−/− (n = 6), and Bdkrb2−/− treated with A-779 (n = 5). (E) Determination of plasma 6-keto-PGF1α. Plasma was collected from wild-type (n = 6), Bdkrb2−/− (n = 6), and Bdkrb2−/− treated with A-779 (n = 5). (B–E) Analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance show differences among groups. The values shown are mean ± SEM. P values shown represent an analysis of difference between 2 groups.

Platelet function of Bdkrb2−/− mice

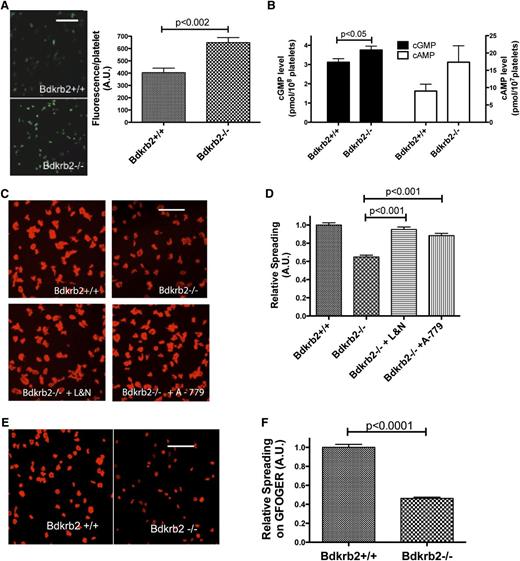

Although the receptors AT2R and Mas influence plasma NO and prostacyclin levels in Bdkrb2−/−, the precise mechanism(s) for thrombosis protection in these animals is not known. We asked if increased plasma NO and prostacyclin altered platelet function in the Bdkrb2−/−. When adhered to collagen, Bdkrb2−/− platelets were observed to have 1.5-fold increased 4-amino-5-methylamino-2,7-difluorofluorescein (DAF-FM) fluorescence, a marker for intracellular NO (Figure 3A). Additionally, resting washed Bdkrb2−/− platelets (n = 6) were observed to have slightly increased (P < .05) guanosine 3',5'-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) levels (3.7 ± 0.5 pmol/108 platelets [n = 6] vs 3.1 ± 0.5 pmol/108 platelets in wild-type [n = 6]) (Figure 3B). Further, when platelets were prepared with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX, Bdkrb2−/− platelets trended toward increased cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels (17 ± 5 pmol/107 platelets [n = 12] vs 9 ± 2 pmol/108 platelets in wild-type [n = 10]) that were not statistically significant (P = .14) (Figure 3B). Because IBMX elevates platelet cAMP, we also prepared platelets treated with aspirin to inhibit internal prostaglandin synthesis.20-22 Aspirinated Bdkrb2−/− platelets also had elevated (P = .13) cAMP (15.8 ± 4 pmol/107 platelets [n = 6] vs 9 ± 2 pmol/108 platelets in aspirinated wild-type [n = 6] [P = .13]). These combined data suggested that resting Bdkrb2−/− platelets constitutively have slightly increased cGMP and cAMP levels.

Characterization of Bdkrb2−/− platelets. (A) Wild-type and Bdkrb2−/− platelet fluorescence with the NO marker DAF-FM (n = 4 samples in each group). The white line is a 20-μm marker. (B) cGMP (left) (n = 6 in each group) and cAMP (right) (n = 12 in each group) in resting wild-type or Bdkrb2−/− platelets. (C) Platelet spreading on collagen by phalloidin staining of cytoskeletal actin from wild-type, Bdkrb2−/− alone, or Bdkrb2−/− treated in vivo with combined L-NAME and nimesulide (L&N) or A-779. (D) The quantification of the data in (C), n ≥ 13 random fields in each group from 3 independent experiments on multiple days. (E) Bdkrb2+/+ or Bdkrb2−/− platelet spreading on the peptide GFOGER. (F) Quantification of the data from (E) (n ≥ 12 random fields from 2 independent experiments). The white line in (C) and (E) is a 5-μm marker. A.U., arbitrary units.

Characterization of Bdkrb2−/− platelets. (A) Wild-type and Bdkrb2−/− platelet fluorescence with the NO marker DAF-FM (n = 4 samples in each group). The white line is a 20-μm marker. (B) cGMP (left) (n = 6 in each group) and cAMP (right) (n = 12 in each group) in resting wild-type or Bdkrb2−/− platelets. (C) Platelet spreading on collagen by phalloidin staining of cytoskeletal actin from wild-type, Bdkrb2−/− alone, or Bdkrb2−/− treated in vivo with combined L-NAME and nimesulide (L&N) or A-779. (D) The quantification of the data in (C), n ≥ 13 random fields in each group from 3 independent experiments on multiple days. (E) Bdkrb2+/+ or Bdkrb2−/− platelet spreading on the peptide GFOGER. (F) Quantification of the data from (E) (n ≥ 12 random fields from 2 independent experiments). The white line in (C) and (E) is a 5-μm marker. A.U., arbitrary units.

Investigations next examined if there were any platelet function defects. Platelet aggregation studies in platelet-rich plasma (PRP) revealed that the minimal concentration that produced maximal aggregation for adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP) (20 ± 0.4 μM for wild-type [n = 4] vs 25 ± 6 μM for Bdkrb2−/− [n = 7] platelets) or γ-thrombin (97 ± 16 nM for wild-type [n = 8] vs 96 ± 7 nM for Bdkrb2−/− [n = 10] platelets) were not significantly different. On flow cytometry, ADP-induced fibrinogen binding of washed platelets was not significantly different between Bdkrb2−/− platelets and wild-type (supplemental Figure 4). In additional studies, α-thrombin (0.01 to 3 nM) or γ-thrombin (2 to 100 nM) produced the same degree of activation of integrin α2bβ3 as determined by the JON/A antibody or P-selection expression on platelets from Bdkrb2−/− and wild-type (supplemental Figures 5A-B and 6A-B). The 50% effective concentration for α (∼1.8 nM) and γ (∼14 nM) thrombin-induced integrin activation or P-selectin expression were similar for Bdkrb2−/− and wild-type platelets (supplemental Figures 5 and 6). These data indicated that Bdkrb2−/− platelets have no defect to ADP- or thrombin-induced activation.

Bdkrb2−/− platelet spreading

Bdkrb2−/− platelets were observed to adhere similarly to collagen as wild-type (supplemental Figure 7). However, Bdkrb2−/− platelets (0.64 ± 0.1 relative spreading, n = 30 fields from 3 independent experiments) were noted to have a 36% reduction in spreading area as determined from pixels analyzed by ImageJ compared with control platelets (1.0 ± 0.1 relative spreading, n = 28) (P < .0001) when adhered to collagen (Figure 3C-D). We next determined if an exogenous NO donor or prostacyclin analog induced a spreading defect on collagen in wild-type platelets. In these experiments, we mimicked the defect in Bdkrb2−/− platelets observed ex vivo. Wild-type washed platelets were incubated with 1 to 100 μM DEA NONOate, an NO donor, or carbaprostacyclin (100 to 900 ng/mL) followed by centrifugation and resuspension in buffer without the inhibitor. Reduced spreading on collagen was observed in wild-type platelets with carbaprostacyclin treatment (100 to 900 ng/mL) but not DEA NONOate (up to 100 μM) (supplemental Figure 8). When Bdkrb2−/− mice were treated in vivo with the combined antagonists L-NAME and nimesulide, inhibitors of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and COX-2, respectively, the spreading defect corrected (0.95 ± 0.11 relative spreading, n = 19) (P < .0001) (Figure 3C-D). Similarly, when Bdkrb2−/− mice were treated in vivo with A-779, the spreading defect also corrected (0.88 ± 0.1 relative spreading, n = 13) (P < .001) (Figure 3C-D). Further studies showed that Bdkrb2−/− platelets have a spreading defect on the collagen peptide GFOGER that recognizes the integrin α2β1 (0.46 ± 0.01 relative spreading [n = 12] in Bdkrb2−/− platelets vs 1.001 ± 0.03 relative spreading [n = 12] in control platelets [P < .0001]) (Figure 3E-3F).13 In vitro studies showed that treating wild-type platelets with 100 μM DEA NONOate (100 μM) or carbaprostacyclin (300 to 900 ng/mL) also induced a spreading defect on GFOGER (supplemental Figure 9). Bdkrb2−/− platelets also were observed to have reduced spreading on fibrinogen that recognizes the integrin α2bβ3, but normal spreading on CRP that recognize GPVI (supplemental Figure 10). Finally, if washed Bdkrb2−/− platelets were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature, the spreading defect on collagen resolved (supplemental Figure 11). These combined data indicated that the elevation of plasma NO and prostacyclin in Bdkrb2−/− mice produced an acquired platelet spreading defect that is mediated by integrins and reversible over time.

GPVI activation in Bdkrb2−/− platelets

Because elevated cAMP and cGMP mediated by NO and prostacyclin inhibit GPVI dimerization, we examined if Bdkrb2−/− platelets also have altered CRP- and convulxin-induced platelet activation.23 CRP-induced α2bβ3 integrin activation (JON/A binding) and P-selectin expression in Bdkrb2−/− platelets were significantly reduced (Figure 4A-B). The 50% effective concentration for CRP for integrin activation and P-selectin expression was 42- and 212-fold higher, respectively, in Bdkrb2−/− than wild-type platelets. When convulxin was used as an agonist, Bdkrb2−/− platelets also had reduced integrin activation and P-selectin expression (Figure 4A-B). In independent studies, we found that wild-type and Bdkrb2−/− mice have an equal amount of total GPVI antigen in platelet lysates on immunoblot. However, on flow cytometry, membrane-expressed GPVI antigen was decreased by 31% on Bdkrb2−/− platelets (supplemental Figure 12). Reduced GPVI membrane expression but equal total GPVI on Bdkrb2−/− platelets may be sign of reduced ability to activate these platelets.24 Because a reduction in the number of GPVI epitopes might account for reduced activation by CRP or convulxin, we determined if in vivo treatment of Bdkrb2−/− mice with the Mas antagonist A-779 corrected CRP-induced platelet activation. As shown in Figure 4C-D, in vivo treatment of Bdkrb2−/− mice with A-779 corrected both 0.6 and 1 μg/mL CRP-induced P-selectin expression defect. These data indicated that systemic Mas receptor overexpression in part resulted in the CRP activation defect in Bdkrb2−/− platelets.

CRP and convulxin (CVX) activation of Bdkrb2−/− platelets. CRP (0.01 to 1 μg/mL) or CVX (0.1 to 5 nM) stimulated integrin activation (JON/A binding) (A) or P-selection expression (B) in wild-type (Bdkrb2+/+) and Bdkrb2−/− platelets. The data represent the mean ± SEM of at least 4 separate experiments with 3 or more platelet samples from each genotype. CRP (0.1 to 1 μg/mL) stimulated integrin activation (JON/A) (C) or P-selection expression (D) in platelets from wild-type (Bdkrb2+/+) (n = 6), Bdkrb2−/− (n = 6), or Bdkrb2−/− in vivo treated with A-779 (n = 7). The data represent the mean ± SEM. CRP (0.1 to 1.0 μg/mL) induced integrin activation (E) and P-selectin expression (F) in platelets from wild-type (Bdkrb2+/+), Bdkrb2−/−, or Bdkrb2−/− treated with nimesulide by gavage for 10 days. The data represent the mean ± SEM of at least 5 animals in each group from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05. MFI, mean fluorescent intensity.

CRP and convulxin (CVX) activation of Bdkrb2−/− platelets. CRP (0.01 to 1 μg/mL) or CVX (0.1 to 5 nM) stimulated integrin activation (JON/A binding) (A) or P-selection expression (B) in wild-type (Bdkrb2+/+) and Bdkrb2−/− platelets. The data represent the mean ± SEM of at least 4 separate experiments with 3 or more platelet samples from each genotype. CRP (0.1 to 1 μg/mL) stimulated integrin activation (JON/A) (C) or P-selection expression (D) in platelets from wild-type (Bdkrb2+/+) (n = 6), Bdkrb2−/− (n = 6), or Bdkrb2−/− in vivo treated with A-779 (n = 7). The data represent the mean ± SEM. CRP (0.1 to 1.0 μg/mL) induced integrin activation (E) and P-selectin expression (F) in platelets from wild-type (Bdkrb2+/+), Bdkrb2−/−, or Bdkrb2−/− treated with nimesulide by gavage for 10 days. The data represent the mean ± SEM of at least 5 animals in each group from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05. MFI, mean fluorescent intensity.

We next determined if in vitro treatment with either NO or prostacyclin alone contributed to the CRP activation defect observed in Bdkrb2−/− platelets. Washed platelets pretreated with increasing DEA NONOate (0.1 to 100 μM) did not block 0.3 μg/mL CRP-induced integrin activation or P-selectin expression (supplemental Figure 13). When Bdkrb2−/− mice were treated with L-NAME, in vivo, CRP-induced P-selectin expression normalized only at 1 μg/mL (supplemental Figure 14). Alternatively washed wild-type platelets pretreated with carbaprostacyclin (300 to 1200 ng/mL) had significantly decreased CRP-induced (0.3 μg/mL) integrin activation and P-selectin expression (supplemental Figure 15). To determine if inhibition of prostacyclin corrected the CRP-induced platelet defect in Bdkrb2−/− platelets, the mice were treated with nimesulide (Figure 4E-F). In vivo nimesulide treatment alone was able to partially correct the integrin activation and P-selectin expression defect induced by 1 μg/mL CRP and P-selectin expression induced by 0.6 μg/mL CRP in Bdkrb2−/− platelets (Figure 4E-F). These data indicate that the observed GPVI activation defect in Bdkrb2−/− platelets was in part due to elevation of prostacyclin and, to a lesser extent, NO.

We next examined if the platelet function defects seen in Bdkrb2−/− mice were acquired from the host or intrinsic to the platelets. Bone marrow transplantation experiments were performed with wild-type and Bdkrb2−/− animals. When wild-type bone marrow was transplanted into a Bdkrb2−/− host, the collected platelets had reduced spreading on collagen similar to that observed when Bdkrb2−/− bone marrow is transplanted into a Bdkrb2−/− host (Figure 5A-B). Alternatively, when Bdkrb2−/− bone marrow is transplanted into a wild-type host, the collected platelets spread on collagen similar to a wild-type bone marrow transplanted into wild-type mice (Figure 5A-B). Next, we determined if bone marrow transplantation altered the thrombosis phenotype of the host animal. Carotid artery vessel closure times of Bdkrb2−/− mice transplanted with wild-type bone marrow were not significantly different from those observed when a Bdkrb2−/− host received Bdkrb2−/− bone marrow (Figure 5C). Likewise, the vessel occlusion times for wild-type mice transplanted with Bdkrb2−/− bone marrow were the same as a wild-type host transplanted with wild-type bone marrow (Figure 5C). These combined studies indicated that the platelet and thrombosis phenotype observed in Bdkrb2−/− mice derived from the host and were not due to an intrinsic platelet defect.

Bone marrow transplantation experiments. (A) Representative slides of platelet spreading on collagen after phalloidin staining of cytoskeletal actin from mice that had Bdkrb2+/+ bone marrow transplanted in Bdkrb2+/+ hosts (WT to WT), Bdkrb2−/− bone marrow transplanted in Bdkrb2−/− hosts (KO to KO), Bdkrb2+/+ bone marrow transplanted in Bdkrb2−/− hosts (WT to KO), or Bdkrb2−/− bone marrow transplanted in Bdkrb2+/+ hosts (KO to WT). The white line is a 5-μm marker. (B) Quantification of spreading among the 4 groups of transplanted mice described in (A). Data were quantified from 4 separate experiments on multiple days including 1 or 2 transplanted mice per experiment (n ≥ 20 random fields). (C) The time to carotid artery thrombosis was determined in the 4 groups of transplanted mice characterized in (A). Each dot represents a single transplanted animal. The horizontal bar in each group represents the mean of the group. (B-C) Data are analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance and found to be significant between host WT and KO. Comparisons between 2 groups are indicated. A.U., arbitrary units; KO, knockout; WT, wild-type.

Bone marrow transplantation experiments. (A) Representative slides of platelet spreading on collagen after phalloidin staining of cytoskeletal actin from mice that had Bdkrb2+/+ bone marrow transplanted in Bdkrb2+/+ hosts (WT to WT), Bdkrb2−/− bone marrow transplanted in Bdkrb2−/− hosts (KO to KO), Bdkrb2+/+ bone marrow transplanted in Bdkrb2−/− hosts (WT to KO), or Bdkrb2−/− bone marrow transplanted in Bdkrb2+/+ hosts (KO to WT). The white line is a 5-μm marker. (B) Quantification of spreading among the 4 groups of transplanted mice described in (A). Data were quantified from 4 separate experiments on multiple days including 1 or 2 transplanted mice per experiment (n ≥ 20 random fields). (C) The time to carotid artery thrombosis was determined in the 4 groups of transplanted mice characterized in (A). Each dot represents a single transplanted animal. The horizontal bar in each group represents the mean of the group. (B-C) Data are analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance and found to be significant between host WT and KO. Comparisons between 2 groups are indicated. A.U., arbitrary units; KO, knockout; WT, wild-type.

Discussion

This investigation shows that the renin-angiotensin system receptor Mas modulates arterial thrombosis potential in the intravascular compartment. Like the AT2R, increased Mas compensates for the absence of the B2R contributing to elevated intravascular NO and prostacyclin.3,7,8,15,16 In vitro and ex vivo studies suggest that elevated plasma prostacyclin interferes with platelet activation better than NO, producing spreading and CRP- or convulxin-induced activation defects. These acquired platelet function defects contribute to the delayed carotid artery thrombosis times on the Rose Bengal model. The pathways described here are important to understand how use of common antihypertensive medications like ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor 1 antagonists lead to a 20% reduction in arterial thrombosis such as myocardial infarction and stroke.1,2 Further, these studies indicate how subtle platelet defects produced by changes in NO and prostacyclin alter arterial thrombosis risk in vivo.

The finding that losartan treatment of Bdkrb2−/− mice reduced plasma AngII without correcting the thrombosis delay challenged our previous interpretation that thrombosis protection in these mice was due to the double finding of elevated AngII and overexpression of the AT2R (Figure 1A-B).3 Alternative explanations were needed. Losartan and its class-related agent telmisartan, in addition to angiotensin 1 receptor antagonism, decreases ACE mRNA, suggesting that this mechanism produced the reduced plasma AngII levels (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 1). Acute administration of losartan elevates AngII, whereas steady-state treatment is associated with reduced plasma AngII levels.25,26 Previously we showed that ACE inhibition lowers AngII levels and corrects the time to thrombosis.3 Even though losartan lowers ACE, there was no decrease in plasma Ang-(1-7). In fact, in the Bdkrb2−/− mice, Ang-(1-7) is slightly increased in the absence or presence of losartan (Figure 1D). Our studies show that losartan does not alter the production of Ang-(1-7) by its 2 major forming enzymes, ACE2 and PRCP (supplemental Figure 3).18 However, it is presently unknown if the slightly elevated Ang-(1-7) levels in Bdkrb2−/− mice is due to reduced clearance. Using losartan only indicated to us that an additional agent influenced by ACE is also contributing to thrombosis protection. Ang-(1-7) is recognized to have an antithrombotic effect.12,19,27,28 Ang-(1-7) mediates its effect through Mas.11 Our previous studies reported no increase in renal Mas but a 1.62-fold increase in liver Mas in Bdkrb2−/− mice.3 We reexamined renal Mas mRNA levels and presently found a twofold increase in Bdkrb2−/− mice that is not influenced by losartan treatment (Figure 1E). These present findings are validated by additional immunoblot studies indicating increased Mas along with AT2R antigen in Bdkrb2−/− kidneys as previously reported.3 Importantly, Ang-(1-7) and its activation of Mas is the candidate second mechanism for thrombosis protection in Bdkrb2−/− mice because Ang-(1-7) levels do not fall with losartan treatment even though AngII levels do.

The Mas receptor and its agonist Ang-(1-7) have been recognized to have an antithrombotic effect. Mas knockout mice have increased venous thrombus size and short bleeding times.12 Activation of ACE2 to produce more Ang-(1-7) or administration of an orally active form of Ang-(1-7) produces a Mas-dependent antithrombotic effect in rats.27,28 We confirmed that Mas contributes to thrombosis protection seen in Bdkrb2−/− mice because systemic treatment with the Mas antagonist A-779 shortens the time to arterial thrombosis, shortens the tail bleeding time, and lowers plasma nitrate and 6-keto-PGF1α. The ability of the Mas antagonist A-779 to correct the thrombosis phenotype of the Bdkrb2−/− mice is identical to that observed when AT2R antagonist PD123319 is used.3 These results suggest that in the absence of the B2R, both Mas and the AT2R become overexpressed and produce increased NO and prostacyclin to compensate. However, neither receptor alone fully compensates for the loss of the B2R, and inhibition of either is sufficient to correct the prolonged thrombosis and bleeding time to normal.

Because the tail bleeding time is prolonged in the Bdkrb2−/− mice, we determined if there is a platelet defect. Bdkrb2−/− platelets have increased DAF-FM, a marker of NO. This finding is due to increased in vivo plasma NO or Ang-(1-7) stimulation of the platelet Mas receptor.12 Resting Bdkrb2−/− platelets also have slightly increased cGMP and cAMP consistent with an elevation of plasma NO and prostacyclin.29 However, no defects in ADP- or thrombin-induced platelet aggregation were observed. Further, there were no defects in ADP-induced fibrinogen binding or α- or γ-thrombin–induced integrin activation or P-selectin expression. Although Bdkrb2−/− platelets adhered normally to collagen, they have decreased spreading. Further, they have normal spreading on CRP but decreased spreading on fibrinogen and GFOGER, a peptide designed to recognize the platelet integrin receptor for collagen, α2β1.13 These data indicate that there is an integrin-dependent spreading defect in Bdkrb2−/− platelets. The relationship between elevated prostacyclin and NO and reduced platelet spreading was evaluated in a series of in vitro and in vivo studies. In vitro treatment of wild-type platelets with the synthetic prostaglandin analog carbaprostacyclin, and to a lesser extent the NO donor DEA NONOate, creates a spreading defect on collagen and GFOGER. In vivo treatment of Bdkrb2−/−mice with the Mas antagonist A-779 or nimesulide and L-NAME, corrects the spreading defect. The mechanism(s) by which prostacyclin and NO induce an integrin-dependent spreading defect is presently not completely known.

In addition to the spreading defect, Bdkrb2−/− platelets have reduced CRP- and convulxin-induced integrin activation and P-selectin expression suggesting that the elevated plasma NO and prostacyclin influences GPVI.30 In in vitro studies, carbaprostacyclin, but not a NO donor, induces a GPVI activation defect in wild-type platelets. Moreover, in vivo treatment with A-779, nimesulide, or L-NAME partially corrects the CRP-induced platelet activation defect. Recent studies indicate that elevation of cAMP, cGMP, and prostacyclin inhibit GPVI dimerization, which is essential for its function.23,31 It is likely that the GPVI activation defect observed in Bdkrb2−/− platelets is related to this mechanism.

Resting Bdkrb2−/− platelets were observed to have ∼30% reduction of membrane GPVI with equal total amounts of GPVI by immunoblots of lysates. It has been shown that only 20% normal GPVI is sufficient to produce full platelet activation by collagen.32 The reduction of membrane GPVI on Bdkrb2−/− platelets alone cannot account for the spreading defect on collagen or reduced CRP-induced activation. The observation that Bdkrb2−/− platelets have a spreading defect on GFOGER peptides and fibrinogen, but normal spreading on CRP, suggest that it is independent of GPVI. Further, the fact that platelet incubation corrects the spreading defect indicates that it is an acquired defect. The bone marrow transplantation experiments confirm that the platelet spreading defect is acquired from the host. Platelets produced from transplanted bone marrow regardless of donor phenotype acquire the spreading phenotype of their host.

Recent investigations indicate that COX-2−/− mice have shortened arterial thrombosis times and that deletion of vascular COX-2 is sufficient to explain their thrombosis risk.33,34 Inhibition of vascular COX-2 influences expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and the release and function of NO.29 Most recently, it has been recognized that prostacyclin regulates arterial thrombus formation by suppressing tissue factor expression in vasculature, leukocytes, and microparticles.35 Although it is not precisely known if elevated prostacyclin is the major contributor to thrombosis protection in our mice, the thrombosis phenotype of Bdkrb2−/− is not influenced by the phenotype of the bone marrow donor. Our data suggest that host factors, derived from vasculature in the Bdkrb2−/− mice, are the major determinant for the thrombosis protection observed.

In conclusion, we have described a novel pathway by which alterations in the vascular renin-angiotensin system receptors modulate arterial thrombosis potential in the intravascular compartment (Figure 6). In the absence of the B2R, elevated AngII or its metabolized product, Ang-(1-7) bind to overexpressed AT2R or Mas, respectively, and increase plasma NO and prostacyclin. Both plasma NO and prostacyclin influence the platelets to produce defects in spreading mediated by integrins and GPVI activation. These pathways contribute to the reduced arterial thrombosis potential seen in Bdkrb2−/− mice. Chronic B2R blockade with an antagonist used in the management of attacks for hereditary angioedema may provide thromboprotection through this mechanism.3,5,6 Understanding these pathways is important in order to appreciate how common antihypertensives like ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists are associated with a 20% reduction in arterial thrombosis as seen in myocardial infarction and stroke. Last, appreciating the subtle differences in vascular and plasma factors observed in the present study begin to clarify the variability in arterial thrombosis risk among individuals.

Mechanism for thromboprotection in Bdkrb2−/− mice. In the absence of B2R, AngII and Ang-(1-7) are elevated in plasma (Figure 1D).3 Ang-(1-7) is the ACE2 breakdown product of AngII. AngII and Ang-(1-7) interact with overexpressed AT2R and Mas receptors, respectively, to increase intravascular NO and prostacyclin. Elevation of plasma prostacyclin and NO influences vascular function, reduces platelet sensitivity to collagen-like agonists, CRP or convulxin, with reduced GPVI activation, and induces a platelet spreading defect on collagen, GFOGER, and fibrinogen. These latter effects on platelets produce a long bleeding time and contribute to the delayed thrombosis in Bdkrb2−/− mice. Interference with AT2R,3 Mas (present report), or combined NO and prostacyclin production (3, present study) normalizes arterial thrombosis potential in Bdkrb2−/− mice. These studies indicate in part how prostacyclin and NO regulates arterial thrombosis risk.

Mechanism for thromboprotection in Bdkrb2−/− mice. In the absence of B2R, AngII and Ang-(1-7) are elevated in plasma (Figure 1D).3 Ang-(1-7) is the ACE2 breakdown product of AngII. AngII and Ang-(1-7) interact with overexpressed AT2R and Mas receptors, respectively, to increase intravascular NO and prostacyclin. Elevation of plasma prostacyclin and NO influences vascular function, reduces platelet sensitivity to collagen-like agonists, CRP or convulxin, with reduced GPVI activation, and induces a platelet spreading defect on collagen, GFOGER, and fibrinogen. These latter effects on platelets produce a long bleeding time and contribute to the delayed thrombosis in Bdkrb2−/− mice. Interference with AT2R,3 Mas (present report), or combined NO and prostacyclin production (3, present study) normalizes arterial thrombosis potential in Bdkrb2−/− mice. These studies indicate in part how prostacyclin and NO regulates arterial thrombosis risk.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Jonathan Stamler and Eugene Podrez for their constructive criticisms.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL052779, HL057346, HL065194, and HL112666 (A.H.S.) and an American Heart Association Beginning Grant-In-Aid 0865441D (M.T.N.).

Authorship

Contribution: C.F., E.S., A.A.S., N.G., M.M., A.C., M.T.N., G.N.A., G.L., Y.Z., M.L.B., F.M., and M.W. performed experiments; C.F., E.S., A.A.S., and A.H.S. conceptualized and planned experiments; A.H.S. and C.F. prepared the figures; and A.H.S., C.F., A.A.S., and E.S. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alvin H. Schmaier, Case Western Reserve University, Wolstein Research Building 2-130, 10900 Euclid Ave, Cleveland, OH 44106-7284; e-mail: schmaier@case.edu.