Abstract

The nuclear export protein XPO1 is overexpressed in cancer, leading to the cytoplasmic mislocalization of multiple tumor suppressor proteins. Existing XPO1-targeting agents lack selectivity and have been associated with significant toxicity. Small molecule selective inhibitors of nuclear export (SINEs) were designed that specifically inhibit XPO1. Genetic experiments and X-ray structures demonstrate that SINE covalently bind to a cysteine residue in the cargo-binding groove of XPO1, thereby inhibiting nuclear export of cargo proteins. The clinical relevance of SINEs was explored in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), a disease associated with recurrent XPO1 mutations. Evidence is presented that SINEs can restore normal regulation to the majority of the dysregulated pathways in CLL both in vitro and in vivo and induce apoptosis of CLL cells with a favorable therapeutic index, with enhanced killing of genomically high-risk CLL cells that are typically unresponsive to traditional therapies. More importantly, SINE slows disease progression, and improves overall survival in the Eμ-TCL1-SCID mouse model of CLL with minimal weight loss or other toxicities. Together, these findings demonstrate that XPO1 is a valid target in CLL with minimal effects on normal cells and provide a basis for the development of SINEs in CLL and related hematologic malignancies.

Introduction

Multicellular organisms have evolved a complex and overlapping array of proteins/pathways that function to “guard the genome” and prevent genesis of neoplastic clones. These proteins, referred to as tumor suppressor proteins (TSPs) and growth regulatory proteins (GRPs), act primarily in the nucleus. CRM1/XPO1 (chromosome region maintenance 1 protein, also called exportin1 or XPO1 in humans) is the best-characterized nuclear exporter, and transports more than 200 proteins and certain RNA species from the nucleus to the cytoplasm.1,2 XPO1 binds to a diverse array of protein cargos through their canonical leucine-rich nuclear export signals (NESs) domain. The NESs are 10- to 15-residue motifs containing 4 or 5 spaced hydrophobic amino acids, which form combined α-helix-loop or all loop structures that bind to the hydrophobic groove of XPO1.1,3-6 XPO1 and cargo form a ternary export complex with RanGTP in the nucleus, which is then translocated through the nuclear pore complex.2,7 In the cytoplasm, cargo is released from XPO1 through the combined action of GTPase regulators RanGAP and RanBP1. XPO1 cargo proteins include numerous TSPs and GRPs, such as p53, FoxO3a, and the endogenous inhibitor of NF-κB, IκB. By exporting these proteins from the nucleus of normal cells, XPO1 prevents them from acting in the absence of DNA damage or other oncogenic insults.8,9 More than 14 distinct TSP/GRP pathways have been identified to be exported by XPO1 in an exclusive fashion to date, and many of these coexist in different types of cancer that continue to be defined.10

Elevated expression or dysfunction of the XPO1 have been reported in various hematologic and solid tumors, and have been correlated with poor prognosis and resistance to therapy.4,8-11 For example, mutation of the TSP nucleophosmin (NPM1) has been reported in a specific subgroup of cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia (AML)12 in which, a gain-of-function mutation in the C-terminus of the NPM1 creates a novel NES and leads to greatly enhanced and unregulated binding to XPO1. In NPM1-mutated AML (NPM1c), enhanced XPO1-mediated transport of NPM1 removes it from the nucleus (and nucleolus), rendering it oncogenic; thus, NPM1c is believed to be a leukemia initiation mutation in this subset of AML.13 This example attests to the importance of nuclear-cytoplasmic transport in the development of leukemia.12,14 Similarly, activated oncogenic signaling pathways can lead to inappropriate phosphorylation and other posttranslational modifications of TSPs and GRPs, rendering the modified proteins susceptible to XPO1-mediated nuclear export.15 Thus, XPO1 is a nodal point by virtue of its nonredundant gate-keeping function, exclusively controlling the directional exodus of TSPs/GRPs from the nucleus to the cytoplasm.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most prevalent type of adult leukemia and is incurable with current therapies. Unlike chronic myeloid leukemia or hairy cell leukemia, CLL does not have a common translocation or mutation that drives the pathogenesis of the disease. CLL tumor cells are highly dependent on the microenvironment where cytokines (eg, CD40L, BAFF, IL-4, IL-6), and contact (eg, stromal cells) promote cell activation and proliferation, and also resistance to spontaneous and drug-mediated apoptosis. Many of these microenvironment-activated pathways merge with TSPs exported by XPO1. XPO1 is therefore a highly attractive molecular target to explore in CLL, because it impacts multiple antitumor and growth suppressive signaling pathways that are dysregulated in this disease.

We therefore hypothesized that a selective XPO1 inhibitor would show efficacy with an acceptable therapeutic index in CLL and other diseases. Indeed, XPO1 inhibition in normal cells (ie, possessing an intact genome) leads to transient cell cycle arrest without cytotoxicity, followed by fast recovery after the drug is removed.16,17 To date, efforts to clinically pharmacologically inhibit XPO1 have been unsuccessful because of off-target effects.18-21 A selective XPO1 antagonist may allow targeting of the TSPs axes in tumor cells.

In this report, we describe the design, via in silico docking methods that were based on an earlier structure activity relationship study,22 of small molecule drug-like selective inhibitors of nuclear export (SINEs) that irreversibly bind to and block XPO1, and demonstrate that XPO1 is a valid target in CLL with minimal effects on normal cells providing the basis for the development of SINEs in CLL and related hematologic malignancies.

Methods

Chemical reagents

See supplemental Methods for a complete list of the reagents used (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Cloning, expression, and protein purification

HsRan was cloned into the pET18 vector. ScXPO1 and ScRanBP1 were cloned into a pGEX-4t-3–based expression vector incorporating a TEV-cleavable N-terminal GST-tag fusion. Further details are in supplemental Methods.

Crystallization and data collection

HsRan was cloned into the pET18 vector and loaded with GMP-PNP as previously described.23 ScXPO1* and ScRanBP1 were cloned into a pGEX-4t-3–based expression vector incorporating a TEV-cleavable N-terminal GST-tag fusion. The proteins were expressed separately in Escherichia coli BL-21 (DE3), purified by affinity and gel filtration chromatography, and assembled for crystallization. Further details are in supplemental Methods.

Structure determination by X-ray crystallography

The KPT-185-ScXPO1*-HsRan-ScRanBP1 complex was crystallized using reservoir solution containing 18% PEG3350, 200mM ammonium nitrate, 100mM Bis-tris pH 6.6.7 X-ray diffraction data were collected at beamline 19ID, advanced photon source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory, and the structure solved by molecular replacement. Further details are in supplemental Methods.

Cell isolation

Human CLL and normal B cells were isolated and cultured as previously described.24 T or NK cells were negatively selected using the appropriate Rosette-Sep kits (StemCell Technologies). The HS-5 cell line was obtained from ATCC and cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Murine splenic lymphocytes were isolated from spleen by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation. Blood was obtained from patients with CLL under an Ohio State University Institutional Review Board–approved protocol with informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell lysis and immunoblot

Cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer. Nuclear extracts were prepared with NE-PER (Pierce). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and blots probed with commercially available antibodies and detected by addition of chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) followed by quantification by ChemiDoc system with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan gene expression assay primer sets for XPO1 (ID:HS00418963_m1) and 18S (ID:HS03003631_g1) and an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) using cDNA prepared as previously described.25

Electrophoretic mobility-shift assays

The NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide (Sigma-Aldrich) was labeled with [γ-32P] dCTP using the Nick Translation System (Invitrogen). The free probe was removed by purification in G50 Sephadex spin columns. Five milligrams of nuclear extract were incubated 20 minutes at room temperature with 30 000 disintegration per minute (dpm) of radiolabeled oligonucleotide probe. The DNA-protein complexes were separated by 6% SDS-PAGE. The gel was dried on 3M Whatman paper and subjected to autoradiography. For supershift assay, 1 μg antibodies to the p65 or p50 subunit were incubated with nuclear extract for 10 minutes before the addition of 32P-labeled probe.

Assessment of cell death

Cell death was assessed using either annexin-V and propidium iodide (PI) flow cytometry–based assay using a Beckman-Coulter model EPICS XL cytometer (BD Bioscience)24 or MTS [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium] assay as previously described.26 Q-CD-OPH and BOC-D-fmk were used at 20μM. Stromal coculture was done by plating HS-5 stromal cells (50% confluent) in a 6-well plate 24 hours before the addition of CLL cells.

Confocal fluorescence microscopy

Cells were made adherent on a microscope slide by centrifugation in a Cytospin3 (Shandon) centrifuge and then fixed in cold acetone. Cells were incubated in blocking solution (2% bovine serum albumin in PBS) and stained with the indicated primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with fluorescent secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 594 [red] and Alexa Fluor 488 [green] from Molecular Probes; Invitrogen). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Vector laboratories). Images were collected with an Olympus Fluoview 1000 Laser Scanning confocal microscope using a PlanApoN 60× oil-immersion objective (numerical aperture 1.42) and a 4× optical zoom. Z stacks of 30 to 40 slices through the cell (0.4 μm) were collected for each slide. Images were processed identically with Olympus Fluoview (Version 2.1b) software and represent 1 slice per slide, selected from the middle of the nucleus; the lines indicate the position within the microscopic field and within the thickness of the nuclei (top-bottom and lateral views). HeLa cells were transfected with the respective plasmids and monitored 1 day after transfection with an SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems) equipped with an AOBS, using an HCX PL APO 63.0 (NA:1.20) water objective.

Cytokine measurements

TNF, IL-10, and IL-6 were measured using Quantikine ELISA assays (R&D Systems). Further details are in supplemental Methods.

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) was determined by standard 4-hour 51Cr-release assay as previously described.25 Further details are in supplemental Methods.

Animal studies

All experiments were carried out under protocols approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. CD19+ cells (1 × 106) from the spleen of a TCL1 transgenic mouse with active CLL-like leukemia and palpable splenomegaly were engrafted by tail vein into a C.B-17 SCID mouse.27 Treatments began 2 weeks after injection (Figure 7B-C) of leukemia cells or as indicated in Figure 7E. Mice were treated with vehicle control (30% PEG400 and 28% HPBCD) or 75 mg/kg of KPT-251 administered orally 5 times per week for 2 weeks and then every other day 3 times per week (QoD3/wk) for the rest of the study. Overall survival was used as the primary end point. Disease progression was monitored by peripheral leukocyte count (PBL) using blood smears in duplicate, read by workers blinded to treatment group. Disease progression was defined as an increase in PBL to > 20 000/μL and was a secondary end point. Mice were sacrificed on development of PBL to > 200 000/μL and presence of other disease criteria causing discomfort. The changes in the body weight are expressed as a ratio relative to the weight just before initial treatment.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS Version 9.2 software (SAS Institute) as outlined in supplemental Methods. IC50s were determined with GraphPad Prism Version 5 software.

Results

KPT-185 binds in the NES-binding groove of XPO1

SINEs, developed by Karyopharm, are small molecules designed in silico to covalently modify a cysteine (Cys528) and participate in numerous noncovalent interactions in the NES-binding groove of human XPO1. The lead compounds KPT-185 and KPT-251 share similar warheads but present distinct pharmacokinetic properties in vivo because of differences in their side chains (Figure 1A).

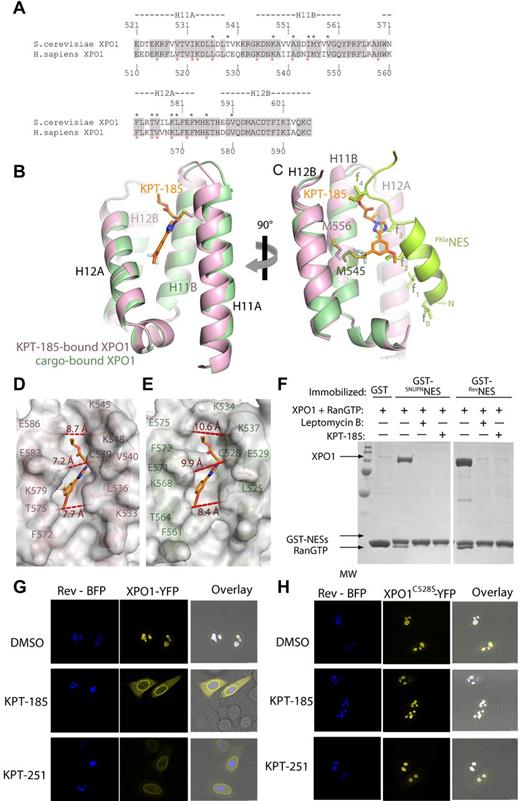

Structure of SINEs bound to XPO1. (A) Chemical structure of KPT-185 and KPT-251 with their heavy atoms numbered. KPT-185 (MW of 355.3) contains a phenyl triazole attached to an isopropyl acrylate via triazole nitrogen. It has good physical properties with cLog P and polar surface area (PSA) of 3.8 and 63.5, respectively. KPT-251 (MW of 375.3), contains a phenyl triazole attached to an oxadiazole ring via a double bond. KPT-251 is a relatively polar compound, and exhibits good physical properties with cLog P and polar surface area (PSA) of 2.5 and 61.9, respectively. (B) The overall structure of the KPT185-ScXPO1*-HsRan-ScRanBP1 complex. A space-filling model of KPT-185 is shown along with XPO1 (pink), Ran (green), and RanBP1 (yellow). (C) The NES-binding groove is located between HEAT repeats H11 and H12, and lined with residues from helices H11A, H11B, H12A and H12B KPT-185 (orange) binds in the NES-binding groove of XPO1 (pink). KPT-185 is oriented with its trifluoromethyl methoxy phenyl group pointing toward the bottom of the XPO1 groove (C-terminal ends of helices H11A and H12A), whereas its isopropyl ester group heads in the opposite direction toward the top of the groove. The activated alkene of KPT-185 is conjugated to the Cys539 sidechain of ScXPO1* through Michael reaction. The methoxy substituent of KPT-185 is partially exposed to solvent but also participates in hydrophobic interactions with the Phe572, Thr575 and Val576 sidechains, which are all located on helix H12A of XPO1. The phenyl ring of KPT-185 is sandwiched between 2 hydrophobic layers. One layer consists of Leu536 and Ile555 sidechains and the other layer consists of the Phe 583 sidechain and the aliphatic portion of the Lys579 sidechain. The triazole ring of KPT-185 is surrounded by hydrophobic XPO1 sidechains sandwiched by Leu536, Cys539 and Ile555 sidechains on one side and the edge of the Phe583 ring on the other. The nitrogen atoms in the triazole ring of KPT-185 make no polar contacts but participate in van der Waals contacts with XPO1 residues. Similarly, polar moieties in the isopropyl ester of KPT-185 make no polar contact with XPO1. The isopropyl ester binds near the top of the XPO1 groove lying close to the floor of the groove with its carbonyl pointing toward solvent and its isopropyl group interacting with the Phe583 and Glu586 sidechains that are located at the C-terminal end of helix H12A. Select inhibitor-XPO1 interactions (< 4Å) are shown with dashed lines. (D-E) Conformational changes in the NES-binding groove of XPO1. (D) The NES-binding groove of XPO1 in the inhibitor-free ScXPO1-Ran-RanBP1 complex (3M1l) is shown as surface representation. The helices and select side chains below the surface are shown in cyan. No ligand is bound in the groove of this XPO1 complex but KPT-185 (placed from superposition of XPO1 residues 570-605 of the ScXPO1-Ran-RanBP1 and the KPT-185-ScXPO1*-Ran-RanBP1 structures) is shown as a reference to facilitate comparison with (E). (E) The NES-binding groove of XPO1 in the KPT-185-ScXPO1*-Ran-RanBP1 complex is shown as surface representation. The helices and select sidechains below the surface are shown in pink and KPT-185 is shown as a stick figure in orange.

Structure of SINEs bound to XPO1. (A) Chemical structure of KPT-185 and KPT-251 with their heavy atoms numbered. KPT-185 (MW of 355.3) contains a phenyl triazole attached to an isopropyl acrylate via triazole nitrogen. It has good physical properties with cLog P and polar surface area (PSA) of 3.8 and 63.5, respectively. KPT-251 (MW of 375.3), contains a phenyl triazole attached to an oxadiazole ring via a double bond. KPT-251 is a relatively polar compound, and exhibits good physical properties with cLog P and polar surface area (PSA) of 2.5 and 61.9, respectively. (B) The overall structure of the KPT185-ScXPO1*-HsRan-ScRanBP1 complex. A space-filling model of KPT-185 is shown along with XPO1 (pink), Ran (green), and RanBP1 (yellow). (C) The NES-binding groove is located between HEAT repeats H11 and H12, and lined with residues from helices H11A, H11B, H12A and H12B KPT-185 (orange) binds in the NES-binding groove of XPO1 (pink). KPT-185 is oriented with its trifluoromethyl methoxy phenyl group pointing toward the bottom of the XPO1 groove (C-terminal ends of helices H11A and H12A), whereas its isopropyl ester group heads in the opposite direction toward the top of the groove. The activated alkene of KPT-185 is conjugated to the Cys539 sidechain of ScXPO1* through Michael reaction. The methoxy substituent of KPT-185 is partially exposed to solvent but also participates in hydrophobic interactions with the Phe572, Thr575 and Val576 sidechains, which are all located on helix H12A of XPO1. The phenyl ring of KPT-185 is sandwiched between 2 hydrophobic layers. One layer consists of Leu536 and Ile555 sidechains and the other layer consists of the Phe 583 sidechain and the aliphatic portion of the Lys579 sidechain. The triazole ring of KPT-185 is surrounded by hydrophobic XPO1 sidechains sandwiched by Leu536, Cys539 and Ile555 sidechains on one side and the edge of the Phe583 ring on the other. The nitrogen atoms in the triazole ring of KPT-185 make no polar contacts but participate in van der Waals contacts with XPO1 residues. Similarly, polar moieties in the isopropyl ester of KPT-185 make no polar contact with XPO1. The isopropyl ester binds near the top of the XPO1 groove lying close to the floor of the groove with its carbonyl pointing toward solvent and its isopropyl group interacting with the Phe583 and Glu586 sidechains that are located at the C-terminal end of helix H12A. Select inhibitor-XPO1 interactions (< 4Å) are shown with dashed lines. (D-E) Conformational changes in the NES-binding groove of XPO1. (D) The NES-binding groove of XPO1 in the inhibitor-free ScXPO1-Ran-RanBP1 complex (3M1l) is shown as surface representation. The helices and select side chains below the surface are shown in cyan. No ligand is bound in the groove of this XPO1 complex but KPT-185 (placed from superposition of XPO1 residues 570-605 of the ScXPO1-Ran-RanBP1 and the KPT-185-ScXPO1*-Ran-RanBP1 structures) is shown as a reference to facilitate comparison with (E). (E) The NES-binding groove of XPO1 in the KPT-185-ScXPO1*-Ran-RanBP1 complex is shown as surface representation. The helices and select sidechains below the surface are shown in pink and KPT-185 is shown as a stick figure in orange.

We have solved the 2.1 Å X-ray structure of XPO1 bound to KPT-185 (Figure 1B, Table 1). The crystals contained KPT-185 bound to the ternary complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae XPO1 (ScXPO1), S cerevisiae RanBP1 (ScRanBP1), and human RanGTP (Table 1). Because ScXPO1 has a threonine residue Thr539 in place of the reactive Cys528 in human XPO1, Thr539 was mutated to cysteine to enable covalent modification by KPT-185 and the T539C mutant of XPO1 is named ScXPO1*. Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the protein data bank under RCSB ID code rcsb074384 and PDB ID code 4GMX.

Crystallographic statistics

| . | KTP-185-ScXPO1(T539C)-HsRan-ScRanBP1 . |

|---|---|

| Cell axial lengths (Å) | a = b = 106.45, c = 306.80 |

| Spacegroup | P43212 |

| Data collection | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.00-2.10 (2.14-2.10) |

| No. of observed reflections | 665019 (25 175) |

| No. of unique reflections | 100063 (4750) |

| Completeness (%) | 96.0 (92.8) |

| Redundancy | 6.7 (5.3) |

| aRsym (%) | 6.8 (47.8) |

| Mean I/Iσ | 29.1 (1.9) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.00-2.10 (2.15–2.10) |

| No. of working reflections | 89 096 (6208) |

| No. of test reflections | 5004 (326) |

| bRwork | 0.151 (0.248) |

| cRfree | 0.192 (0.288) |

| R.m.s. deviation bond lengths (Å) | 0.014 |

| R.m.s. deviation bond angles (°) | 1.51 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | Protein: 27.1 |

| KPT-185: 34.2 | |

| Solvent content (%) | 57.6 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Most favored (%) | 94.1 |

| Allowed (%) | 5.6 |

| General allowed (%) | 0.2 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.1 |

| . | KTP-185-ScXPO1(T539C)-HsRan-ScRanBP1 . |

|---|---|

| Cell axial lengths (Å) | a = b = 106.45, c = 306.80 |

| Spacegroup | P43212 |

| Data collection | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.00-2.10 (2.14-2.10) |

| No. of observed reflections | 665019 (25 175) |

| No. of unique reflections | 100063 (4750) |

| Completeness (%) | 96.0 (92.8) |

| Redundancy | 6.7 (5.3) |

| aRsym (%) | 6.8 (47.8) |

| Mean I/Iσ | 29.1 (1.9) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.00-2.10 (2.15–2.10) |

| No. of working reflections | 89 096 (6208) |

| No. of test reflections | 5004 (326) |

| bRwork | 0.151 (0.248) |

| cRfree | 0.192 (0.288) |

| R.m.s. deviation bond lengths (Å) | 0.014 |

| R.m.s. deviation bond angles (°) | 1.51 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | Protein: 27.1 |

| KPT-185: 34.2 | |

| Solvent content (%) | 57.6 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Most favored (%) | 94.1 |

| Allowed (%) | 5.6 |

| General allowed (%) | 0.2 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.1 |

The overall structure of the KPT-185-ScXPO1*-Ran-RanBP1 complex is similar to the previously reported inhibitor-free ScXPO1-Ran-RanBP1 structure (Cα rmsds of ∼ 0.65 Å).7 The ring-shaped XPO1 protein contains 21 tandem HEAT repeats (designated H1-H21), each composed of a pair of antiparallel helices A and B. The N-terminal half of XPO1 wraps around RanŸGppNHp, which in turn wraps around RanBP1 with its C-terminal extension (Ran residues 177-216; Figure 1B). KPT-185 binds in the NES-binding groove, which is located on the central, convex side of the XPO1 ring (Figure 1B-C, supplemental Figure 1A). In the absence of inhibitor, the NES-binding groove of ScXPO1 is closed in the ScXPO1-Ran-RanBP1 complex (Figure 1D, supplemental Figure 1B).7 In our structure, the NES groove has opened to accommodate KPT-185 (Figure 1E). Interestingly, interactions between KPT-185 and XPO1 are almost entirely of hydrophobic nature (Table 2). The methoxy, carbonyl, and ester groups of KPT-185 do not seem to make any polar contacts with XPO1. The tri-fluoromethyl group of KPT-185 is buried deep in the XPO1 groove, whereas its methoxy group reaches toward the groove opening (Figure 1C). Fluorine atoms F1, F2, and F3 are buried in the XPO1 groove through numerous hydrophobic interactions with several XPO1 sidechains including Ile555, Met556, and Val559 that line the floor of the NES-binding groove (Figure 1C, Table 2).

Contacts* between XPO1 and KPT-185

| KPT-185 atom . | XPO1 residue (atom*) . |

|---|---|

| F1 | V559 (CG2), V576 (CG1) |

| F2 | V576 (CG1), K579 (CB), L580 (CD2) |

| F3 | M556 (CG), F583 (CE2) |

| C13 | |

| O2 | T575 (CG2) |

| C12 | F572(CE1), T575 (CG2), V576 (CG2) |

| C6 | L536 (CD2), K579 (CG) |

| C7 | L536 (CD2), K579 (CG) |

| C8 | K579 (CG) |

| C9 | K579 (CB) |

| C10 | K579 (CG) |

| C11 | I555 (CG2), K579 (CG) |

| C4 | C539 (CB) |

| C5 | L536 (CD2), I555 (CD1) |

| N1 | I555 (CD1), C539 (SG) |

| N2 | L536 (CD2) |

| N3 | I555 (CD1), F583 (CZ), C539 (SG) |

| O1 | F583 (CE1), C539 (SG) |

| C1 | |

| C2 | A555 (CB) |

| C3 | C539 (SG)† |

| O1′ | K548 (CB) |

| C1′ | F583 (CE1), E586 (OE1) |

| C2′ | E586 (CG, OE1) |

| C3′ | E586 (OE1) |

| KPT-185 atom . | XPO1 residue (atom*) . |

|---|---|

| F1 | V559 (CG2), V576 (CG1) |

| F2 | V576 (CG1), K579 (CB), L580 (CD2) |

| F3 | M556 (CG), F583 (CE2) |

| C13 | |

| O2 | T575 (CG2) |

| C12 | F572(CE1), T575 (CG2), V576 (CG2) |

| C6 | L536 (CD2), K579 (CG) |

| C7 | L536 (CD2), K579 (CG) |

| C8 | K579 (CG) |

| C9 | K579 (CB) |

| C10 | K579 (CG) |

| C11 | I555 (CG2), K579 (CG) |

| C4 | C539 (CB) |

| C5 | L536 (CD2), I555 (CD1) |

| N1 | I555 (CD1), C539 (SG) |

| N2 | L536 (CD2) |

| N3 | I555 (CD1), F583 (CZ), C539 (SG) |

| O1 | F583 (CE1), C539 (SG) |

| C1 | |

| C2 | A555 (CB) |

| C3 | C539 (SG)† |

| O1′ | K548 (CB) |

| C1′ | F583 (CE1), E586 (OE1) |

| C2′ | E586 (CG, OE1) |

| C3′ | E586 (OE1) |

Contacts < 4Å.

Covalent bond.

KPT-185 inhibits XPO1-cargo interactions

The regions of human/mouse and yeast XPO1 proteins that form the NES-binding grooves share 81% sequence identity and almost all XPO1 residues involved in NES and inhibitor-binding are strictly conserved suggesting that mammalian and yeast XPO1 grooves likely bind ligands in very similar fashion (Figure 2A) that of XPO1 bound with the NES from protein kinase A inhibitor (PKIα).3,5,6 XPO1 helices at the grooves of both ScXPO1-KPT-185 and mouse XPO1-PKIαNES structures superimpose with a Cα rmsd of 1.2 Å. Examination of the grooves show the KPT-185–bound XPO1 groove to be narrower and deeper that the NES-bound groove (Figure 2B-C). A slight reorientation helix H11A and several sidechain rearrangements accompany the structural shift from NES to inhibitor binding (Figure 2D-E). Structures of inhibitor-free, inhibitor-bound, and NES-bound XPO1 grooves clearly indicate that the NES-binding groove is conformationally quite plastic. Interestingly, the trifluoromethyl phenyl of KPT-185 penetrates much deeper into the groove than the NES sidechains, possibly contributing to the potency of the compound in outcompeting nuclear export cargos (Figure 2B-E).

Comparison of the inhibitor and NES-bound grooves. (A) Sequence alignment of NES-binding grooves (HEAT repeats H11 and H12) of S cerevisiae XPO1 and human XPO1. Identical residues are shaded in gray, residues that contact KPT-185 are marked with black asterisks, and residues that contact the PKINES (3NBY) are marked with red asterisks. (B) Superposition of the KPT-185 (pink) and PKINES-bound (green) grooves. KPT-185 (orange) and Cys539 of ScXPO1* (pink) are shown as sticks. (C) Same view as in (B), but rotated 90° about the vertical axis and helices H12A of both grooves were removed to obtain a clear side view of the ligands in the groove. The PKINES and its hydrophobic sidechains are colored bright green. (D-E) Surface representations of the KPT-185 (D) and PKINES-bound XPO1 grooves (E). Distances across the openings of the grooves are shown in red. The 13-residue long PKINES peptide is substantially larger than KPT-185 and occupies the entire groove, burying 1117 Å2 whereas KPT-185 buries only 420 Å2 of the XPO1 groove. When the PKINES and KPT-185–bound grooves are superimposed, it is obvious that hydrophobic residues 2, 3, and 4 of the peptide overlap with the inhibitor. Two overlaps with methoxy group, 3 with the triazole, and 4 overlaps with the terminal oxadiazole group of KPT-185.(F) KPT-185 inhibits XPO1-cargo interactions. Approximately 15 μg of GST-NESs were immobilized on glutathione sepharose and then incubated with 10μM XPO1 proteins that were preincubated with either buffer or inhibitors (20μM LMB or 200μM KPT-185) and molar excess of RanGTP. After extensive washing, a fraction of the bound proteins was visualized by SDS-PAGE and Coomasie blue staining. (G) HeLa cells expressing Rev-BFP and/or wild-type XPO1-YFP were analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Rev-BFP localizes in the nucleoli of the cells, whereas XPO1-YFP is mainly found at the nuclear rim. In cells coexpressing both Rev-BFP and XPO1-YFP, XPO1 is redistributed to the Rev-containing nucleoli and colocalizes with Rev-BFP. Two hours after addition of SINEs the colocalization of XPO1-YFP with Rev-BFP in the nucleoli was analyzed. Both compounds disrupt the wild-type XPO1-YFP colocalization with Rev-BFP, although they had no effect when a mutant XPO1-YFP (C528S) was used as shown in panel H.

Comparison of the inhibitor and NES-bound grooves. (A) Sequence alignment of NES-binding grooves (HEAT repeats H11 and H12) of S cerevisiae XPO1 and human XPO1. Identical residues are shaded in gray, residues that contact KPT-185 are marked with black asterisks, and residues that contact the PKINES (3NBY) are marked with red asterisks. (B) Superposition of the KPT-185 (pink) and PKINES-bound (green) grooves. KPT-185 (orange) and Cys539 of ScXPO1* (pink) are shown as sticks. (C) Same view as in (B), but rotated 90° about the vertical axis and helices H12A of both grooves were removed to obtain a clear side view of the ligands in the groove. The PKINES and its hydrophobic sidechains are colored bright green. (D-E) Surface representations of the KPT-185 (D) and PKINES-bound XPO1 grooves (E). Distances across the openings of the grooves are shown in red. The 13-residue long PKINES peptide is substantially larger than KPT-185 and occupies the entire groove, burying 1117 Å2 whereas KPT-185 buries only 420 Å2 of the XPO1 groove. When the PKINES and KPT-185–bound grooves are superimposed, it is obvious that hydrophobic residues 2, 3, and 4 of the peptide overlap with the inhibitor. Two overlaps with methoxy group, 3 with the triazole, and 4 overlaps with the terminal oxadiazole group of KPT-185.(F) KPT-185 inhibits XPO1-cargo interactions. Approximately 15 μg of GST-NESs were immobilized on glutathione sepharose and then incubated with 10μM XPO1 proteins that were preincubated with either buffer or inhibitors (20μM LMB or 200μM KPT-185) and molar excess of RanGTP. After extensive washing, a fraction of the bound proteins was visualized by SDS-PAGE and Coomasie blue staining. (G) HeLa cells expressing Rev-BFP and/or wild-type XPO1-YFP were analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Rev-BFP localizes in the nucleoli of the cells, whereas XPO1-YFP is mainly found at the nuclear rim. In cells coexpressing both Rev-BFP and XPO1-YFP, XPO1 is redistributed to the Rev-containing nucleoli and colocalizes with Rev-BFP. Two hours after addition of SINEs the colocalization of XPO1-YFP with Rev-BFP in the nucleoli was analyzed. Both compounds disrupt the wild-type XPO1-YFP colocalization with Rev-BFP, although they had no effect when a mutant XPO1-YFP (C528S) was used as shown in panel H.

To investigate the effects of KPT-185 on XPO1-cargo complexes, we performed pull-down inhibition assays using purified recombinant human XPO1, and molar excesses of RanGTP and NESs from HIV1-REV and snurportin-1 (SNUPN) immobilized on glutathione sepharose (Figure 2F). Human XPO1 was preincubated with either leptomycin B (LMB)28,29 or KPT-185. Both LMB and KPT-185 inhibited the formation of XPO1-cargo complex. Furthermore, a similar SINE KPT-251 was also able to inhibit XPO1 mediated HIV-Rev nuclear export in U2OS cells stably expressing RevGFP (supplemental Figure 2A). A large panel (50) of in vitro protein binding assays was performed to evaluate the potential interaction of KPT-251 and KPT-185 with other proteins. At a concentration of 10μM, both compounds show exquisite specificity for XPO1 and no detectable binding to other proteins, including the cysteine proteases believed to be the cause of poor tolerance to LMB (data not shown). Given these results, SINEs are considered to be highly selective agents (> 100-fold compared with inhibition of XPO1-mediated HIV Rev transport of 100nM, supplemental Figure 2A). The effect of SINEs on XPO1 interaction in HeLa cells cotransfected with Rev target with blue fluorescent protein (BFP) and either wild-type or XPO1(C528S) mutant human XPO1 tagged with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) was assessed.22,30 When coexpressed, a significant fraction of both wild-type XPO1-YFP (Figure 2G) or XPO1(C528S)-YFP (Figure 2H) colocalized with Rev in the nucleoli, suggesting an interaction between the 2 proteins. On treatment with KPT-185 or KPT-251, the Rev-dependent nucleolar localization of wild-type XPO1-YFP but not XPO1(C528S)–YFP is abolished confirming that the Cys528 in XPO1 is required for SINEs to disrupt the XPO1 binding to Rev cargo.

XPO1 inhibition induces selective cytotoxicity in CLL cells

Expression of XPO1 in primary CLL cells9,31 and control normal B cells was examined. Immunoblot analysis showed XPO1 to be overexpressed in CLL cells compared with normal B cells at the protein (Figure 3A-B) and mRNA level (Figure 3C). As XPO1 is a recycled transporter, even modest increases in its levels might have a marked effect on the subcellular localization of cargo proteins.

KPT-185 induces selective cytotoxicity in CLL cells. (A) CD19+ cells from CLL patients (N = 13) and normal donors (N = 12) were examined for XPO1 expression by immunoblot. Results are shown from 1 of 2 identical experiments. (B) Data analysis of band intensities measured in 2 immunoblots of CLL patient and normal B-cell samples (XPO1/actin ratio). (C) RNA was extracted from CD19+ cells from CLL patients (N = 8) or normal donors (N = 8). XPO1 expression was determined by real-time RT-PCR analysis. Ct values are relative to actin. Higher relative Ct values represent lower gene expression. (D) KPT-185 induces a time and dose-dependent cytotoxicity of CLL cells as measured by MTS assay (N = 10 per timepoint). (E) KPT-185 and KPT-251 induce comparable level of cytotoxicity of CLL cells at 72-hour time-point as measured by MTS assay (N = 6 each). (F) KPT-185 is not cytotoxic to normal PBMC and isolated B cells as measured by annexin-V/PI flow cytometry (N = 6 each). (G) Comparison of the cytotoxic effect of KPT-185 on CLL versus normal B cells as measured by MTS assay (N = 8 each). (H-J) Cytogenetic abnormalities and IVGH mutational status were examined for differences in response to KPT-185 of CLL cells. (K-I) Treatment with SINEs promotes cell death through a caspase-dependent pathway. CLL patient cells were treated with various concentrations of KPT-251 for 12 or 24 hours in presence or absence of the caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPH. Lysates derived from these cells (12 hours) were assessed for cleavage of PARP and caspase 3 by immunoblot analysis. (L) Apoptosis was measured at 24 hours by annexin-V/PI flow cytometry.

KPT-185 induces selective cytotoxicity in CLL cells. (A) CD19+ cells from CLL patients (N = 13) and normal donors (N = 12) were examined for XPO1 expression by immunoblot. Results are shown from 1 of 2 identical experiments. (B) Data analysis of band intensities measured in 2 immunoblots of CLL patient and normal B-cell samples (XPO1/actin ratio). (C) RNA was extracted from CD19+ cells from CLL patients (N = 8) or normal donors (N = 8). XPO1 expression was determined by real-time RT-PCR analysis. Ct values are relative to actin. Higher relative Ct values represent lower gene expression. (D) KPT-185 induces a time and dose-dependent cytotoxicity of CLL cells as measured by MTS assay (N = 10 per timepoint). (E) KPT-185 and KPT-251 induce comparable level of cytotoxicity of CLL cells at 72-hour time-point as measured by MTS assay (N = 6 each). (F) KPT-185 is not cytotoxic to normal PBMC and isolated B cells as measured by annexin-V/PI flow cytometry (N = 6 each). (G) Comparison of the cytotoxic effect of KPT-185 on CLL versus normal B cells as measured by MTS assay (N = 8 each). (H-J) Cytogenetic abnormalities and IVGH mutational status were examined for differences in response to KPT-185 of CLL cells. (K-I) Treatment with SINEs promotes cell death through a caspase-dependent pathway. CLL patient cells were treated with various concentrations of KPT-251 for 12 or 24 hours in presence or absence of the caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPH. Lysates derived from these cells (12 hours) were assessed for cleavage of PARP and caspase 3 by immunoblot analysis. (L) Apoptosis was measured at 24 hours by annexin-V/PI flow cytometry.

The effect of inhibiting either its expression or its activity was investigated using siRNA or SINE compounds. CLL cells were transiently transfected with a XPO1 siRNA and its effect on cell death was evaluated. Analyses of XPO1 expression by real-time RT-PCR and immunoblot (supplemental Figure 3A-B) showed that the gene knockdown, although modest, resulted in a significant reduction in cell viability relative to the missense control (supplemental Figure 3C).

The cytotoxic effect of KPT-185 against primary CLL cells was next evaluated and compared with that induced by LMB. CLL cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of KPT-185 or LMB (ranging from 0.01μM to 10μM) for 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours. KPT-185 induced significant time and dose-dependent cytotoxicity (Figure 3D) as measured by MTS conversion (EC50 < 500nM). Cell death was observed as early as 24 hours and continued to increase up to 96 hours; a 72-hour time point was chosen for all the subsequent experiments. Cell death was confirmed by annexin/PI flow cytometry in cells treated with 1μM KPT-185 (data not shown). KPT-185 induced superior cytotoxic effect compared with LMB (supplemental Figure 3D). Consistent with the irreversible mechanism of action of SINEs, short exposures (as little as 1 hour) were sufficient to promote apoptosis (supplemental Figure 3E). An isomer of KPT-185,10 was used to confirm that the cytotoxic effect seen on CLL cells is because of the specific inhibition of XPO1 and not to an off-target effect (supplemental Figure 3F-G). KPT-251 and KPT-185 on CLL cells were next compared and found to be equally effective in inducing apoptosis of CLL cells (Figure 3E). The effects of KPT-185 on PBMC and normal B cells from healthy volunteers were then assessed. KPT-185 produced only modest apoptosis (estimated EC50 > 40μM, Figure 3F) at 72 hours in normal PBMCs and B cells compared with CLL cells (EC50 ∼500nM; Figure 3G), suggesting that transformed B cells are more sensitive to KPT-185 treatment than normal B cells. As CLL (and normal B cells) are not cycling, these data indicate that apoptosis induction by SINE is not cell cycle–dependent. Although significant cytotoxicity was observed with KPT-185 treatment, the variability in patient CLL cell response was marked (5% to 90% at 0.5μM). Traditional CLL prognostic factors were therefore examined to determine whether they would predict response to KPT-185. Cytogenetic 12q, 11q, or 13q abnormalities did not confer differential sensitivity to KPT-185 induced cell death, whereas 17p deletions (associated with reduced p53 expression) were associated with reduced overall sensitivity (Figure 3H). Interestingly, when 17p deletions were divided into those with unmutated and mutated IVGH, only the latter subset of del(17p) samples showed reduced sensitivity to KPT-185 induced death (Figure 3I). Therefore, IVGH mutational status was examined for differences in response to KPT-185, as it has a strong influence on not just chemotherapy response but also on progression-free survival associated with standard therapies used to treat CLL.32 In contrast to other therapies in CLL, a significant increase in sensitivity to KPT-185 in patient cells with unmutated IVGH was found compared with those with mutated IVGH (Figure 3J). Interestingly, although the presence of del(17p) in patients with IVGH unmutated status did not alter the cytotoxicity levels of KPT-185, the presence of the same deletions in patients with IVGH mutated status significantly reduced the cytotoxicity effect of KPT-185. These data suggest that KPT-185 may have more clinical activity in the unfavorable IVGH unmutated CLL subset, and may also be active in CLL with 17p deletions that have IVGH unmutated disease. Cytotoxicity induced by SINEs was determined to be caspase-dependent, as evidenced by cleavage of the caspase-3 substrate PolyADP ribose polymerase (PARP) and inhibition of cytotoxicity by the caspase inhibitors Q-VD-OPH and BOC-D-FMK (Figure 3K-L).

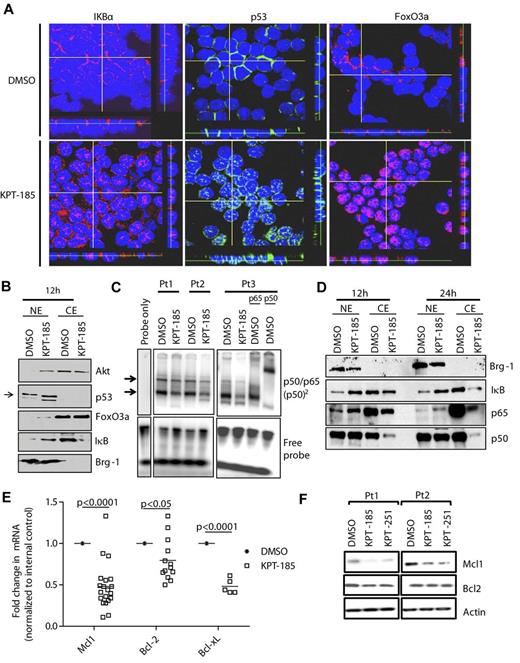

SINEs-specifically inhibit nuclear export

Human CLL cells exhibit dysregulated growth and TSP pathways such as constitutive active AKT33 and NF-κB,34 as well as functional loss of p53 activity.35 As the nuclear export of factors involved in each of these pathways is mostly mediated by XPO1, treatment of CLL with KPT-185 could restore normal regulation of these pathways by forcing nuclear retention of FoxO3a (counters AKT/PI3K), IκB (counters NF-κB), and p53, thereby inducing the death of CLL cells. As shown in Figure 4, treatment of CLL cells with KPT-185 led to strong accumulation of these proteins in the nucleus in a time-dependent manner with the maximum effect observed at 12 hours as revealed by confocal microscopy (Figure 4A, supplemental Figure 4A-C). Results were confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Figure 4B) of lysates derived from DMSO or KPT-185 treated CLL cells.

SINEs-specifically inhibit nuclear export. (A) Confocal fluorescence microscopy for p53, FoxO3a, and IκB show time-dependent increases in nuclear levels of these proteins in KPT-185 treated cells compared with vehicle control. Results shown are representative of 5 experiments. Z stacks were collected (0.4 μm per slice) and images were chosen from the middle of nuclei. Side views (across bottom and side of figures) are also shown. (B) Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were isolated from KPT-185 treated CLL cells (12 and 24 hours) and analyzed by immunoblot for AKT, FoxO3a, IκB, p53, and BRG1. Results shown are from 1 representative patient sample. (C) CD19+ cells from CLL patients (N = 3) were incubated with 1μM KPT-185 for 12 hours. EMSA was done with nuclear extract using a radio-labeled oligonucleotide containing a consensus NF-κB binding site. KPT-185–treated samples were also incubated with antibodies specific to the p65 or p50 subunits of NF-κB. The p65/p50 complex is indicated by arrows. Results are shown from 3 of 3 experiments. (D) Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were isolated from KPT-185 treated CLL cells (12 and 24 hours) and analyzed by immunoblot for p50 and p65, and BRG-1. Results shown are from 1 representative patient sample. (E) Real-time RT-PCR for Mcl1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL after 12 hours (0.5μM) KPT-185 treatment. Data are normalized to 18S transcript and represented as fold change in expression of KPT-185 treated relative to the vehicle control. Squares represent individual patient samples, and horizontal bars represent the average. (F) Whole cell expression of Mcl1 and Bcl-2. Results shown are from 2 representative patient samples.

SINEs-specifically inhibit nuclear export. (A) Confocal fluorescence microscopy for p53, FoxO3a, and IκB show time-dependent increases in nuclear levels of these proteins in KPT-185 treated cells compared with vehicle control. Results shown are representative of 5 experiments. Z stacks were collected (0.4 μm per slice) and images were chosen from the middle of nuclei. Side views (across bottom and side of figures) are also shown. (B) Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were isolated from KPT-185 treated CLL cells (12 and 24 hours) and analyzed by immunoblot for AKT, FoxO3a, IκB, p53, and BRG1. Results shown are from 1 representative patient sample. (C) CD19+ cells from CLL patients (N = 3) were incubated with 1μM KPT-185 for 12 hours. EMSA was done with nuclear extract using a radio-labeled oligonucleotide containing a consensus NF-κB binding site. KPT-185–treated samples were also incubated with antibodies specific to the p65 or p50 subunits of NF-κB. The p65/p50 complex is indicated by arrows. Results are shown from 3 of 3 experiments. (D) Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were isolated from KPT-185 treated CLL cells (12 and 24 hours) and analyzed by immunoblot for p50 and p65, and BRG-1. Results shown are from 1 representative patient sample. (E) Real-time RT-PCR for Mcl1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL after 12 hours (0.5μM) KPT-185 treatment. Data are normalized to 18S transcript and represented as fold change in expression of KPT-185 treated relative to the vehicle control. Squares represent individual patient samples, and horizontal bars represent the average. (F) Whole cell expression of Mcl1 and Bcl-2. Results shown are from 2 representative patient samples.

IκB is a potent endogenous inhibitor of NF-κB, a transcription factor with inflammatory, antiapoptotic activity that is constitutively active in CLL.34 KPT-185 induced IκB nuclear accumulation, allowing it to complex with nuclear NF-κB and reduce the DNA binding capacity of NF-κB (Figure 4C). Interestingly, KPT-185–enforced nuclear retention of IκB leads also to depletion of NF-κB p50 and p65 (Figure 4D) therefore reducing NF-κB function in CLL. Among its many functions, NF-κB has been shown to up-regulate Mcl1 the most critical survival factors for CLL cells.36 Interestingly, KPT-185–enforced nuclear retention of IκB leads to Mcl1 depletion in CLL cells (Figure 4E-F). Similarly, additional NF-kB target genes such as Bcl-xL were also reduced after treatment of CLL cells with KPT-185 (supplemental Figure 4D).

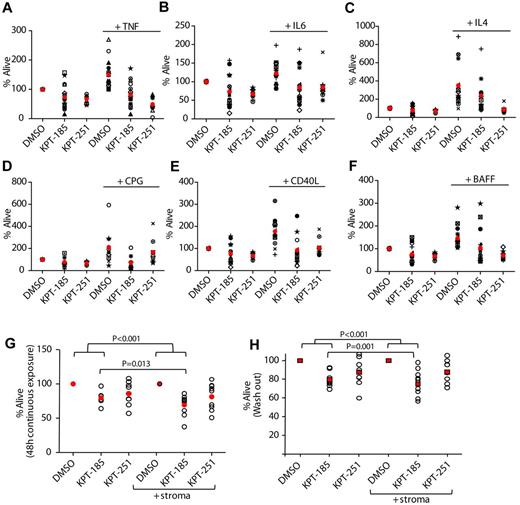

SINEs antagonize microenvironment stimuli

CLL tumor cells are known to receive a variety of survival signals from the microenvironment that confer them resistance to spontaneous apoptosis as well as to chemotherapy.37 Therefore, the ability of KPT-185 to induce cytotoxicity of CLL cells in the presence or absence of soluble factors known to reduce the spontaneous apoptosis associated with CLL cells (TNF, IL-6, and IL-4) or induce activation of key signaling pathways (CD40L and BAFF) was examined. As shown in Figure 5A through F, each of these factors significantly reduced the spontaneous apoptosis associated with CLL cells and cotreatment with SINEs abrogated this protection. Interestingly, the cytotoxic effect elicited by KPT-185 was enhanced in CPG-activated cells. The survival benefit of CLL in vivo is not only influenced by soluble factors such as those previously discussed, but also by cocontact with a variety of cells composing the bone marrow and lymph node microenvironment.38 Therefore, the efficacy of SINEs in the presence of stromal protection was investigated using the human marrow-derived fibroblast cell line HS-5 that enables long-term survival of primary human B cells and B-CLL cells ex vivo.39 Direct treatment of the HS-5 stromal cells with SINEs for 72 hours had no effect on viability (supplemental Figure 5A). CLL patient cells were incubated with either DMSO, KPT-185, or KPT-251 for 12 hours before washing and plating in flasks with or without HS-5 for a total of 60 hours (Figure 5G). Alternatively CLL cells with or without HS-5 were continuously treated with KPT-185 or KPT-251 for 48 hours (Figure 5H). As expected, coculture of untreated CLL cells on the HS-5 stromal cell line resulted in reduction of spontaneous apoptosis (supplemental Figure 5B), and cells treated with KPT-185 or KPT-251 without HS-5 coculture exhibited apoptosis (Figure G-H). However, the prosurvival effect of HS-5 was unable to effectively prevent SINEs induced apoptosis; in fact, the cytotoxic effect mediated by KPT-185 was enhanced under stromal coculture conditions (Figure 5G). These results provide important evidence that KPT-185 may evade the protective effects of the CLL cell microenvironment counteracting multiple oncogenic and growth potentiating signals and therefore providing an advantage over other therapeutics used in the treatment of this disease.

SINEs antagonize microenvironment stimuli. CD19+ cells from CLL patients (N = 10) were incubated with or without 1μM KPT-185 or KPT-251 for 72 hours in presence or absence of (A) 20 ng/mL TNF, (B) 40 ng/mL IL-6, (C) 800 U/mL IL-4, (D) 3μM of CPG, (E) 1 μg/mL CD40L, and (F) 50 ng/mL BAFF. (G) CD19+ cells from CLL patients were isolated from peripheral blood and incubated with or without KPT-185 or KPT-251 (1 and 2.5μM) in suspension or on an HS5 cell layer for 48 hours. Viability was determined by annexin-V/PI flow cytometry, and is shown relative to time-matched DMSO controls for each group. Red circles represent averages. (H) CD19+ cells from CLL patients were isolated from peripheral blood and incubated with or without KPT-185 or KPT-251 (1 and 2.5μM) for 12 hours. Drug was then washed out and cells were incubated in suspension or on an HS5 cell layer for additional 48 hours. Viability was determined by annexin-V/PI flow cytometry, and is shown relative to time-matched DMSO controls for each group. Horizontal bars represent averages.

SINEs antagonize microenvironment stimuli. CD19+ cells from CLL patients (N = 10) were incubated with or without 1μM KPT-185 or KPT-251 for 72 hours in presence or absence of (A) 20 ng/mL TNF, (B) 40 ng/mL IL-6, (C) 800 U/mL IL-4, (D) 3μM of CPG, (E) 1 μg/mL CD40L, and (F) 50 ng/mL BAFF. (G) CD19+ cells from CLL patients were isolated from peripheral blood and incubated with or without KPT-185 or KPT-251 (1 and 2.5μM) in suspension or on an HS5 cell layer for 48 hours. Viability was determined by annexin-V/PI flow cytometry, and is shown relative to time-matched DMSO controls for each group. Red circles represent averages. (H) CD19+ cells from CLL patients were isolated from peripheral blood and incubated with or without KPT-185 or KPT-251 (1 and 2.5μM) for 12 hours. Drug was then washed out and cells were incubated in suspension or on an HS5 cell layer for additional 48 hours. Viability was determined by annexin-V/PI flow cytometry, and is shown relative to time-matched DMSO controls for each group. Horizontal bars represent averages.

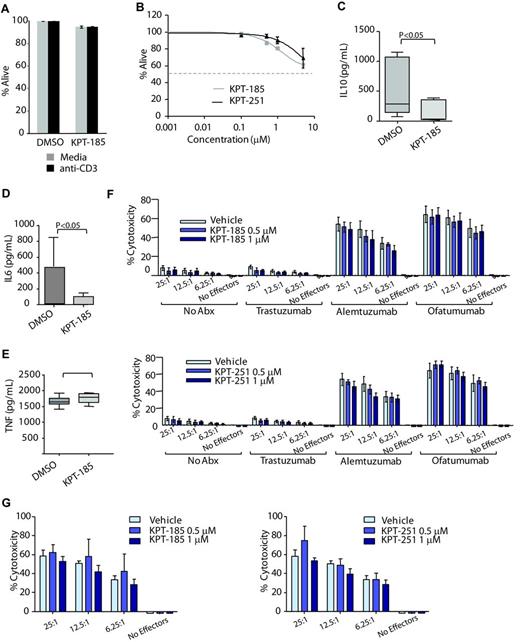

SINEs do not alter T cell or NK cell viability but negatively influence IL-6 and IL-10 production

CLL is associated with immune suppression that is often augmented by therapeutics used to treat the disease. The influence of KPT-185 on T cell and natural killer (NK) cell viability and function was therefore investigated. The viability of naive T cells, CD3 activated T cells, and NK cell was minimally influenced by SINE treatment (Figure 6A-B). Cytokine production by CD3-activated T cells demonstrated no difference in tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) production, whereas production of both IL-6 and IL-10 was diminished by KPT-185 (Figure 6C-E). Neither antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (Figure 6F) nor direct cytotoxicity (Figure 6G) mediated by NK cells was affected by KPT-185 or by KPT-251. Collectively, these studies suggest that SINEs have minimal effects on normal immune cells with respect to viability or NK cell–mediated killing but may impact both inflammatory (IL-6) and immunosuppressive (IL-10) cytokines linked to CLL pathogenesis.

SINEs do not alter T cell or NK cell viability but negatively influences IL-6 and IL-10 production. (A) CD3+ T cells (N = 6) from normal volunteers were incubated with or without 1μM of KPT-185 for 48 hours. Cells were stimulated using an anti-CD3 T-cell activation plate for additional 24 hours. Cells viability (ann/PI negative cells) was measured by annexin-V/PI flow cytometry and was calculated relative to time-matched untreated controls. (B) CD56+ NK cells (N = 6) from normal volunteers were incubated with or without KPT-185 for 72 hours. Viability was measured by annexin-V/PI flow cytometry and was calculated relative to time-matched untreated controls. (C-E) Supernatant from anti-CD3 stimulated T cells treated with or without 1μM of KPT-185 for 48 hours was collected and IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α production were measured by ELISA. (F) ADCC against CLL cells was measured using KPT-185 or KPT-251–treated NK cells (12 hours) from normal volunteers and CLL cells at 6.25:1, 12.5:1, and 25:1 effector to target ratio (E:T) in the presence or absence of 10 μg/mL ofatumumab, alemtuzumab, or trastuzumab. Columns are averages of triplicate wells, and are representative of 3 independent experiments; bars represent SD. (G) NK directed cytotoxicity against K562 cells was measured using KPT-185 or KPT-251–treated NK cells (12 hours) from normal volunteers and K562 cells at E:T ratios of 6.25:1, 12.5:1, and 25:1. Columns are averages of triplicate wells and are representative of 3 independent experiments; bars represent SD.

SINEs do not alter T cell or NK cell viability but negatively influences IL-6 and IL-10 production. (A) CD3+ T cells (N = 6) from normal volunteers were incubated with or without 1μM of KPT-185 for 48 hours. Cells were stimulated using an anti-CD3 T-cell activation plate for additional 24 hours. Cells viability (ann/PI negative cells) was measured by annexin-V/PI flow cytometry and was calculated relative to time-matched untreated controls. (B) CD56+ NK cells (N = 6) from normal volunteers were incubated with or without KPT-185 for 72 hours. Viability was measured by annexin-V/PI flow cytometry and was calculated relative to time-matched untreated controls. (C-E) Supernatant from anti-CD3 stimulated T cells treated with or without 1μM of KPT-185 for 48 hours was collected and IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α production were measured by ELISA. (F) ADCC against CLL cells was measured using KPT-185 or KPT-251–treated NK cells (12 hours) from normal volunteers and CLL cells at 6.25:1, 12.5:1, and 25:1 effector to target ratio (E:T) in the presence or absence of 10 μg/mL ofatumumab, alemtuzumab, or trastuzumab. Columns are averages of triplicate wells, and are representative of 3 independent experiments; bars represent SD. (G) NK directed cytotoxicity against K562 cells was measured using KPT-185 or KPT-251–treated NK cells (12 hours) from normal volunteers and K562 cells at E:T ratios of 6.25:1, 12.5:1, and 25:1. Columns are averages of triplicate wells and are representative of 3 independent experiments; bars represent SD.

SINEs prolong survival in a mouse model of CLL

The in vivo significance of SINE inhibition of XPO1 was studied using the Eμ-TCL1-SCID transplant model of CLL.40 Eμ-TCL1 mice develop disease very similar to that of CLL patients including activation of the AKT pathway, elevated Igκ+ B cells, splenomegaly, and infiltration of malignant B-lymphocytes to the liver, lungs, and kidney.27 CD19+ leukemia cells from these mice were engrafted into SCID mice.40 These cells were also tested to confirm the expression of XPO1 and the sensitivity to SINEs and fludarabine. Unlike KPT-185, with poor systemic pharmacokinetic (PK) properties including minimal oral bioavailability in mice, KPT-251 displayed improved PK in mice and good oral availability, allowing in vivo experiments with oral administration (Table 3). Considering that both compounds present similar selectivity and induce similar levels of in vitro cytotoxicity of CLL (Figure 4E) and murine TCL1+ cells (Figure 7A) the in vivo experiment was conducted using KPT-251.

Pharmacokinetic properties

| PK parameters . | KPT-185 . | KPT-251 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PO-10 mg/kg . | IV-5 mg/kg . | PO-10 mg/kg . | IV-5 mg/kg . | |

| Cmax (ng/ml)* | 4.2 | 2267 | 439 | 4192 |

| Tmax, h | 0.083 | NA | 0.5 | NA |

| T1/2, h | NA | 0.37 | 3.83 | 1.07 |

| AUC, h × ng/mL | NA | 208 | 1590 | 1370 |

| Bioavailability (%) | NA | 56 | ||

| PK parameters . | KPT-185 . | KPT-251 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PO-10 mg/kg . | IV-5 mg/kg . | PO-10 mg/kg . | IV-5 mg/kg . | |

| Cmax (ng/ml)* | 4.2 | 2267 | 439 | 4192 |

| Tmax, h | 0.083 | NA | 0.5 | NA |

| T1/2, h | NA | 0.37 | 3.83 | 1.07 |

| AUC, h × ng/mL | NA | 208 | 1590 | 1370 |

| Bioavailability (%) | NA | 56 | ||

C0 for IV dosing.

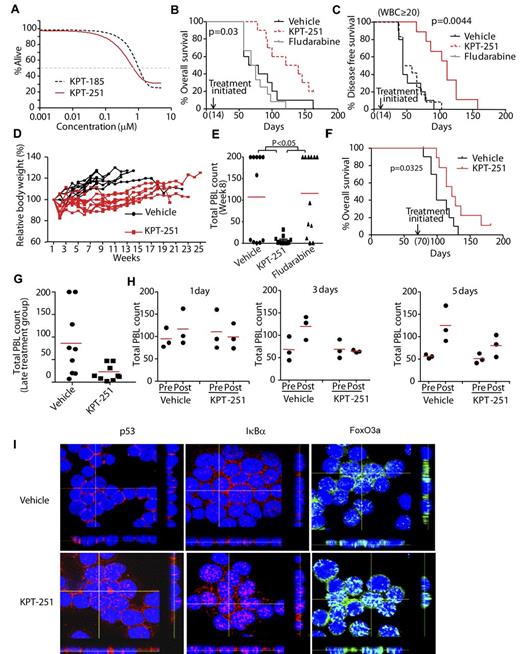

SINEs prolong survival in a mouse model of CLL. (A) KPT-185 and KPT-251 induce similar dose-dependent cytotoxicity of murine TCL1 leukemia cells as measured by MTS assay (N = 14). (B) Overall survival (OS) curve for TCL1-SCID mice treated with 75 mg/kg KPT-251 (N = 10), 34 mg/kg fludarabine (n = 12), or vehicle control (N = 10). Treatment was initiated 14 days after engraftment. Median OS: 130.5 days (KPT-251), 72 days (vehicle), and 71.5 days (fludarabine). (C) Progression-free survival (PFS) curve, with progression defined as increase in circulating CLL (CD19+/TCL1+) cells to > 20 000/μL. Median PFS = 111, 44, and 51 days for KPT-251, vehicle and fludarabine, respectively. (D) Body-weight changes for experiment shown in panel B (KPT-251 and fludarabine-treated mice). (E) Peripheral blood count (PBL) in KPT-251, fludarabine, and vehicle control-treated TCL1-SCID mice. Count was determined by hematoxylin and eosin-stained peripheral blood smear at day 56 (week 8) after initiation of treatment. (F) Overall survival curve for TCL1-SCID mice treated with 75 mg/kg KPT-251 (N = 10) or vehicle control (N = 10). Treatment was initiated 70 days after engraftment. Median survival = 122 days, and 99 days for KPT-251 and vehicle, respectively. (G) PBL counts from TCL1-SCID mice treated 70 days after engraftment with 75 mg/kg KPT-251 or vehicle control (N = 10). Count was determined by hematoxylin and eosin-stained peripheral blood smear. Graph shows last count available for each animal. (H) PBL in TCL1-SCID mice before and 1, 3, or 5 days after administration of a single dose of KPT-251 or vehicle control. Count was determined by hematoxylin and eosin-stained peripheral blood smear. (I) Confocal fluorescence microscopy for p53, FoxO3a, and IκB in tumor cells isolated from mice treated with a single dose of KPT-251 or vehicle control for 72 hours. Results shown are representative of 3 experiments. Z stacks were collected (0.4 μm per slice) and images were chosen from the middle of nuclei. Side views (across bottom and side of figures) are also shown to depict the nuclear localization of p53, FoxO3a, and IκB in the cells.

SINEs prolong survival in a mouse model of CLL. (A) KPT-185 and KPT-251 induce similar dose-dependent cytotoxicity of murine TCL1 leukemia cells as measured by MTS assay (N = 14). (B) Overall survival (OS) curve for TCL1-SCID mice treated with 75 mg/kg KPT-251 (N = 10), 34 mg/kg fludarabine (n = 12), or vehicle control (N = 10). Treatment was initiated 14 days after engraftment. Median OS: 130.5 days (KPT-251), 72 days (vehicle), and 71.5 days (fludarabine). (C) Progression-free survival (PFS) curve, with progression defined as increase in circulating CLL (CD19+/TCL1+) cells to > 20 000/μL. Median PFS = 111, 44, and 51 days for KPT-251, vehicle and fludarabine, respectively. (D) Body-weight changes for experiment shown in panel B (KPT-251 and fludarabine-treated mice). (E) Peripheral blood count (PBL) in KPT-251, fludarabine, and vehicle control-treated TCL1-SCID mice. Count was determined by hematoxylin and eosin-stained peripheral blood smear at day 56 (week 8) after initiation of treatment. (F) Overall survival curve for TCL1-SCID mice treated with 75 mg/kg KPT-251 (N = 10) or vehicle control (N = 10). Treatment was initiated 70 days after engraftment. Median survival = 122 days, and 99 days for KPT-251 and vehicle, respectively. (G) PBL counts from TCL1-SCID mice treated 70 days after engraftment with 75 mg/kg KPT-251 or vehicle control (N = 10). Count was determined by hematoxylin and eosin-stained peripheral blood smear. Graph shows last count available for each animal. (H) PBL in TCL1-SCID mice before and 1, 3, or 5 days after administration of a single dose of KPT-251 or vehicle control. Count was determined by hematoxylin and eosin-stained peripheral blood smear. (I) Confocal fluorescence microscopy for p53, FoxO3a, and IκB in tumor cells isolated from mice treated with a single dose of KPT-251 or vehicle control for 72 hours. Results shown are representative of 3 experiments. Z stacks were collected (0.4 μm per slice) and images were chosen from the middle of nuclei. Side views (across bottom and side of figures) are also shown to depict the nuclear localization of p53, FoxO3a, and IκB in the cells.

Mice were treated (14 days after engraftment) with vehicle, 75 mg/kg KPT-251 5 d/wk for 2 weeks by oral gavage and then QoDx3/wk until the end of the study. Fludarabine 34 mg/kg 5 d/wk every 4 weeks intraperitoneally was used as control because TCL1 leukemic cells have been shown to have wild-type p53 and respond to fludarabine both in vitro and in vivo.27 Dose and time schedules were chosen based on PK data derived from CD1 mice receiving a single dose of KPT-251 (Tables 4–5). The primary end point of the study was overall survival. Mice treated with KPT-251 showed a significant improvement in survival over both vehicle and fludarabine treated mice (Figure 7B). The secondary end point was progression free survival (PFS), defined as increase in circulating CLL (CD19+/TCL1+) cells to > 20 000/μL. KPT-251 showed a significant improvement in PFS compared with both vehicle and fludarabine (Figure 7C). In addition, KPT-251 was well tolerated in mice, resulting in moderate loss in body weight, (≤ 10%) that was reversed by the end of the study (Figure 7D). An analysis of peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) at week 8 showed that KPT-251 significantly prevented an increase in circulating CLL cells compared with both vehicle and fludarabine (Figure 7E).

Individual and mean plasma concentration-time data of KPT-251 after a PO dose of 50 mg/kg in CD1 mice

| Dose (mg/kg) . | Dose route . | Sampling time, h . | Plasma concentration (ng/mL) Individual . | Mean . | SD . | CV(%) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | PO | 0.5 | 1610 | 620 | 982 | 1071 | 501 | 46.8 |

| 2 | 1150 | 1720 | 1320 | 1397 | 293 | 21.0 | ||

| LLOQ = 1 ng/mL | 4 | 1080 | 559 | 940 | 860 | 270 | 31.4 | |

| 24 | 9.69 | 56.2 | 386 | 151 | 205 | 136 | ||

| 36 | 2.74 | 4.97 | BQL | 3.86 | 1.58 | N/A | ||

| Dose (mg/kg) . | Dose route . | Sampling time, h . | Plasma concentration (ng/mL) Individual . | Mean . | SD . | CV(%) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | PO | 0.5 | 1610 | 620 | 982 | 1071 | 501 | 46.8 |

| 2 | 1150 | 1720 | 1320 | 1397 | 293 | 21.0 | ||

| LLOQ = 1 ng/mL | 4 | 1080 | 559 | 940 | 860 | 270 | 31.4 | |

| 24 | 9.69 | 56.2 | 386 | 151 | 205 | 136 | ||

| 36 | 2.74 | 4.97 | BQL | 3.86 | 1.58 | N/A | ||

N/A indicates not available.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of KPT-251 after a PO dose of 50 mg/kg in CD1 mice

| PK parameters . | Unit . | Estimated value . |

|---|---|---|

| Tmax | hr | 2.00 |

| Cmax | ng/mL | 1400 |

| Terminal t1/2 | hr | 4.43 |

| AUClast | hr×ng/mL | 15 400 |

| AUCINF | hr×ng/mL | 15 400 |

| PK parameters . | Unit . | Estimated value . |

|---|---|---|

| Tmax | hr | 2.00 |

| Cmax | ng/mL | 1400 |

| Terminal t1/2 | hr | 4.43 |

| AUClast | hr×ng/mL | 15 400 |

| AUCINF | hr×ng/mL | 15 400 |

To further validate KPT-251 in mice with leukemic phase, 20 additional C.B-17 SCID mice were engrafted with CD19+ TCL1 leukemia cells and treatment was initiated 70 days (week 10) after engraftment. Mice were treated with vehicle or 75 mg/kg KPT-251 (QoD×3/wk). Mice treated with KPT-251 had a significant survival advantage over vehicle-treated controls (Figure 7F). Moreover, KPT-251 significantly prevented an increase in circulating CLL cells compared with vehicle (Figure 7G).

To determine the in vivo relevance of the in vitro pharmacodynamic studies in primary human CLL cells, 27 additional Eμ-TCL1-SCID mice were left untreated until disease developed, as defined by circulating PBLs ≥ 30 000/uL. Mice were than randomized to receive a single dose of KPT-251 or vehicle control (9 mice/group). Three mice for each group were sacrificed at 1, 3, or 5 days posttreatment, and protein and mRNA expression were analyzed in tumor cells isolated from mice. PBLs count was also monitored at the time of treatment and when the mice were sacrificed. Figure 7H shows that a single dose of KPT-251 significantly prevented an increase in circulating CLL cells compared with vehicle for all the analyzed time points. More importantly, the reduced PBL count correlates also with an increased level of p53, FoxO3a, and IκB in the nuclei of KPT-251 but not in vehicle-treated cells (3 days, Figure 7I). Similar to the results in vitro, Mcl1 was also down-modulated after KPT-251 treatment in vivo (supplemental Figure 6). In summary, the effects of SINEs observed in vitro also were observed with a single dose of KPT-251 in vivo. These data show that KPT-251 represents a novel therapeutic agent that targets XPO1 in the Eμ-TCL1-SCID CLL model and provide support for clinical development in CLL and related lymphoproliferative disorders.

Discussion

The development of cancer is a multistep process generally involving dysfunction of multiple tumor suppressing proteins that are either silenced or compartmentally localized to the cytoplasm where they are ineffective at detecting genomic damage and, when appropriate, promoting cell death. XPO1 is a major nuclear export protein involved in externalizing multiple TSP, and is overexpressed or mutated in a variety of cancers including CLL. XPO1 cargos include numerous targets including tumor suppressors, and cell cycle inhibitors such as p53, FoxO, topo IIα, and IκB.41 The increased export of these proteins from the nucleus has been implicated in cancer disease progression and drug resistance. It has been shown that blocking XPO1–mediated nuclear export of any or all of these proteins by siRNA or XPO1 inhibitors may restore apoptotic pathways and tumor cell sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs such as doxorubicin,42 etoposide,42 cisplatin,43 and imatinib mesylate. Therefore XPO1 export inhibitors have the potential to be used as both single agents and in combination with current chemotherapeutic drugs.

CLL is characterized by disrupted apoptosis caused by aberrant activation of several signaling/transcriptional pathways that promote survival (eg, PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB). Therefore, a therapeutic strategy simultaneously targeting multiple death and antioncogenic pathways disrupted in this disease may have broad application for many subsets of patients.

Consequently, XPO1 represents a highly attractive molecular target in CLL, because it impacts multiple signaling pathways that are dysregulated in this disease. Published data have established XPO1 as a validated cancer target in solid tumors8,9,11,18,44 ; however, previous attempts to pharmacologically manipulate XPO1 have been unsuccessful because of off-target effects. Several irreversible non–drug-like inhibitors that bind covalently to Cys 528 in the NES-binding groove of human XPO1 have been reported, including the natural products leptomycin B (LMB), ratjadone C, anguinomycin, goniothalamin, along with the small molecule drug-like N-azolylacrylates.22,45 Recently, a novel reversible oral XPO1 inhibitor with XPO1 degrading activity (CBS9106) has also been reported.46

LMB is the most extensively studied XPO1 inhibitor, and is a widely used biologic tool to define XPO1-mediated protein export. LMB was shown to be active preclinically in several solid tumor and hematologic tumor models18,19,21,42 but was associated with a low therapeutic index in mouse studies because of off-target gastrointestinal effects, as well as profound dose-limiting anorexia, fatigue, and gastrointestinal effects when introduced in a phase 1 study when given intravenously.20 In this trial neither target validation of XPO1 inhibition nor etiology of nausea/emesis and fatigue were adequately addressed.19,20 Semisynthetic derivatives of LMB with improved pharmacologic properties nearly eliminated the toxicities in mice, suggesting that at least some of the LMB toxicities were not mediated by XPO1 inhibition.18

Our work documents the creation of novel, orally bioavailable selective and irreversible inhibitors of XPO1-mediated nuclear export that bear a favorable therapeutic index to transformed tumor cells compared with normal cells. The SINEs compounds show exquisite specificity for XPO1 and no detectable binding to other proteins, including the cysteine proteases believed to be the cause of poor tolerance to LMB. The high resolution crystal structure of XPO1 bound to KPT-185 validates conjugation of KPT-185 to the cysteine in the cargo-binding groove of XPO1 (Cys528) and explains its potency in inhibiting XPO1-cargo interactions and nuclear export. More importantly, KPT-251 has pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, including oral bioavailability that are superior to LMB and allow its use in vivo. SINEs induce apoptosis of CLL cells with a favorable therapeutic index, with enhanced killing of genomically high-risk CLL cells that are typically unresponsive to traditional therapies. The amount of cytotoxicity induced by SINEs did not correlate with the level of expression of XPO1. SINEs restored normal regulation to the majority of the dysregulated pathways in CLL by forcing the nuclear retention of key TSPs such as FOXO, IκB, and p53 both in vitro and in vivo. Among its many functions, NF-κB has been shown to play a role in the up-regulation of Mcl1 the most significant antiapoptotic protein associated with normal as well as malignant B lymphocytes.36 High levels of Mcl1 mRNA and protein have been found in CLL, which are inversely correlated with in vitro response to chemotherapeutic agents or with the failure of CLL patients to respond to fludarabine, chlorambucil, and rituximab therapy in vitro and in vivo.47-49 Therapeutically, down-regulation of Mcl1 protein expression by antisense oligonucleotides or through indirect Mcl1 transcription and translation inhibitors results in cell death during in vitro culture or in vivo therapy.47,50,51 Interestingly, KPT-185 induces depletion of Mcl1 message and protein in CLL cells, probably because of the inactivation of NF-κB and the sensitivity of patients' samples to KPT-185 correlates with the amount of down-modulation of Mcl1. Similarly, a significant reduction of Mcl1 mRNA was also observed on XPO1 down-modulation using siRNA strategy. Based on our data showing that KPT-SINEs modify nuclear level of TSPs, such as p53, important to resistance to traditional therapies, the interaction of KPT-SINEs treatment with traditional p53-dependent therapies used in CLL, (ie, fludarabine, chlorambucil) warrants future study.

KPT-SINE has been previously shown to selectively kill acute leukemia cells compared with PBMCs and CD34+ progenitor cells in vitro.52 Data presented here further support this observation indicating that SINEs possess tumor-cell selectivity, with only weak effects on normal PBMCs. Moreover, KPT-185 evades the protective effects of the CLL cell microenvironment providing an advantage over other therapeutics used in the treatment of this disease. The mechanism by which KPT-185 antagonizes survival stimuli is not known and warrants further study. In a mouse model of CLL, KPT-251 reduces leukemic cell counts, slows disease progression, and improves overall survival with minimal weight loss or other toxicities. It should be emphasized that KPT-251 can be given over many months to mice indicating that is well tolerated. Similar to the results in vitro, Mcl1, and XIAP mRNA were also down-modulated in mice receiving a single dose of KPT-251, although no differences were observed at protein level. Together, these findings show that XPO1 is a useful target in CLL cells with minimal effects on normal cells, and provide a basis for development of SINEs in CLL and related hematologic malignancies. We believe that the future development of low-toxicity, small-molecule XPO1 inhibitors may provide a new approach to treating cancer.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the patients who provided blood for the previously mentioned studies, research support from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and the National Cancer Institute (P50 CA140158 and 1K12 CA133250). The authors also thank Els Vanstreels for help with confocal imaging (Figure 2G-H).

This work is funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM069909; Y.M.C.), Welch Foundation (I-1532; Y.M.C.), Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Scholar award (Y.M.C.), Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT; RP120352; Y.M.C. and PR-101496; Q.S.), and University of Texas Southwestern Endowed Scholars Program (Y.M.C.). Results shown in this report are derived from work performed at Argonne National Laboratory, Structural Biology Center at the Advanced Photon Source. Argonne is operated by UChicago Argonne LLC, for the US Department of Energy, Office of Biologic and Environmental Research under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. All the immunofluorescence images presented in this paper (except Figure 2G-H) were collected at the Confocal Microscopy Imaging Facility (CMIF) at The Ohio State University. Mr and Mrs Michael Thomas, The Harry Mangurian Foundation, and The D. Warren Brown Foundation also supported this work.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: R.L., Q.S., Y.M.C., and J.C.B. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, wrote the paper, and reviewed and approved the final version of the paper; and K.W., L.T., S.J., Y.Z., V.G., E.M., C.B., S.G., A.F., R.M., A.J.J., D.L., X.M., D.D., V.S., S. Shechter, D.M., S. Shacham, and M.K. planned and contributed to components of the experimental work presented (chemistry, biologic, or animal studies), reviewed and modified versions of the paper, and approved the final version of the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: V.S., S. Shechter, D.M., S. Shacham, and M.K. are employees of Karyopharm and have financial interests in this company. D.D. received research funding from Karyopharm and have financial interests in the SINE compounds. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: John C. Byrd, D. Warren Brown Chair of Leukemia Research, Professor of Medicine and Medicinal Chemistry, 455B OSUCCC, 410 W 12th Ave, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210; e-mail: john.byrd@osumc.edu; or Yuh Min Chook, Department of Pharmacology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 6001 Forest Park, ND8.120c, Dallas, TX 75390-9041; e-mail: yuhmin.chook@utsouthwestern.edu.

References

Author notes

R.L. and Q.S. contributed equally to this work.

Y.M.C. and J.C.B are co–senior authors and contributed equally to this work.