Abstract

The 8p11 myeloproliferative syndrome (EMS), also referred to as stem cell leukemia/lymphoma, is a chronic myeloproliferative disorder that rapidly progresses into acute leukemia. Molecularly, EMS is characterized by fusion of various partner genes to the FGFR1 gene, resulting in constitutive activation of the tyrosine kinases in FGFR1. To date, no previous study has addressed the functional consequences of ectopic FGFR1 expression in the potentially most relevant cellular context, that of normal primary human hematopoietic cells. Herein, we report that expression of ZMYM2/FGFR1 (previously known as ZNF198/FGFR1) or BCR/FGFR1 in normal human CD34+ cells from umbilical-cord blood leads to increased cellular proliferation and differentiation toward the erythroid lineage in vitro. In immunodeficient mice, expression of ZMYM2/FGFR1 or BCR/FGFR1 in human cells induces several features of human EMS, including expansion of several myeloid cell lineages and accumulation of blasts in bone marrow. Moreover, bone marrow fibrosis together with increased extramedullary hematopoiesis is observed. This study suggests that FGFR1 fusion oncogenes, by themselves, are capable of initiating an EMS-like disorder, and provides the first humanized model of a myeloproliferative disorder transforming into acute leukemia in mice. The established in vivo EMS model should provide a valuable tool for future studies of this disorder.

Introduction

The 8p11 myeloproliferative syndrome (EMS), also known as stem cell leukemia/lymphoma, is a myeloproliferative disorder (MPD) that WHO recently classified as belonging to the group of myeloid neoplasms associated with eosinophilia and abnormalities of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1.1 Clinically, EMS is characterized by leukocytosis, eosinophilia, splenomegaly, and a short chronic phase that rapidly progresses into aggressive acute myeloid (AML) or lymphoblastic (ALL) leukemia. A prominent feature of the disease is an increased incidence of T-cell lymphomas, seen in 30% of the cases, suggesting that the target cell of transformation is a multipotent progenitor cell.2 Although several FGFR1 inhibitors have been tested with promising effects in vitro,3-5 the only cure for this disease at present is allogeneic bone marrow (BM) transplantation.

At the molecular level EMS is characterized by various translocations fusing at least 8 different 5′ partner genes to the 3′ part of the FGFR1 gene that encodes the tyrosine kinase domain.6 In most of these fusion proteins, the amino terminal regions contain structural properties that allow them to dimerize or oligomerize, resulting in constitutive activation of FGFR1.7

A limited number of studies in murine cells have addressed how FGFR1 fusion oncogenes elicit their transforming activities, mainly focusing on the 2 most common fusion gene variants ZMYM2/FGFR1 (previously known as ZNF198/FGFR1) and BCR/FGFR1. Expression of ZMYM2/FGFR1 in IL-3 dependent murine Ba/F3 cells resulted in growth-factor independent growth in which signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 become constitutively tyrosine phoshorylated.8,9 Mice receiving transplants with ZMYM2/FGFR1-transduced mouse BM cells develop a condition that resemble EMS with MPD and T-cell lymphoma.10 Moreover, mice that receive BCR/FGFR1-transduced BM cell transplants develop a rapid fatal chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)–like disease.10 Although these studies in murine models have provided valuable pathogenetic insights into the different FGFR1 fusion genes, the functional consequences of their expression in primary human cells have not been addressed. In fact, the introduction of leukemia-associated fusion genes in primary human cells, followed by transplantation into immunodeficient mice has, so far, been successful in reproducing the corresponding human disease only for the 3 fusion genes MLL/AF9(MLLT3), MLL/ENL(MLLT1), and TEL(ETV6)/JAK2.11-14

Herein, we demonstrate that retroviral expression of ZMYM2/FGFR1 or BCR/FGFR1 in human CD34+ hematopoietic cells induces an increased cellular proliferation and erythropoietin (EPO)–independent differentiation toward the erythroid lineage in vitro. In immunodeficient mice, both fusion oncogenes induce an MPD-like disorder, accompanied by bone marrow fibrosis and blast accumulation, consistent with features observed in EMS patients.15,16

Methods

Isolation, transduction, and sorting of cord blood CD34+ cells

The collection of cord blood (CB) was approved by the Lund University ethics committee and performed after informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Samples from different donors were pooled, mononuclear cells were isolated by centrifugation over Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield PoC A/S), and the CD34+ cells were enriched by the use of MACS separation columns and isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of the CD34+ cells was routinely higher than 95% as assessed by flow cytometry.

The retroviral vectors MSCV-IRES-GFP (MIG), MIG-BCR/FGFR1, MIG ZMYM2/FGFR1, MIG-BCR/ABL1, MIG-BCR/FGFR1 Y653/654F, MIG-ZMYM2/FGFR1 Y653/654F, and the lentiviral vectors short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) scramble and anti-STAT5 were used in this study. For origins, modifications, and production of these vectors, see supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). CD34+ cells were thawed and prestimulated for 48 hours in Dulbeccos Modified Eagle Media with GlutaMAX (Invitrogen Corporation), containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Invitrogen Corporation), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The medium was supplemented with the following cytokines (Peprotech Inc): 50 ng/mL thrombopoietin (TPO), 100 ng/mL stem cell factor (SCF), and 100 ng/mL Flt-3-ligand (FL). Viral vectors were preloaded using Retronectin (Takara Bio Inc). In the anti-STAT5 shRNA experiments, the lentiviral vectors, with previously well documented effects,17 were used together with the retroviral vectors. The prestimulated CD34+ cells were resuspended in prestimulation medium with the addition of 4 μg/mL protamine sulfate, and added to the wells at a density of 1 × 105 to 1.5 × 105 cells/mL. After 48 hours in culture, the GFP+ or GFP+/RFP+ cells were sorted using a FACSAria cellsorter (BD).

Cell proliferation analysis and colony forming assay

For the cell proliferation analysis, 1 × 104 GFP+ or GFP+/RFP+ cells were sorted into wells of a 96-well plate containing 200 μL serum-free Stemspan SFEM medium (StemCell Technologies Inc), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The medium was supplemented with 50 ng/mL TPO, 100 ng/mL SCF, 100 ng/mL FL, 25 ng/mL IL-3, and 10 ng/mL IL-6. Cultured cells were given fresh medium regularly. Cell numbers were counted at days 7 and 14.

For the colony-forming assay, 50 GFP+ or GFP+/RFP+ cells were sorted into wells of a 48-well plate containing 200 μL methylcellulose medium Methocult (StemCell Technologies Inc) supplemented with 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 5U/mL EPO, 25 ng/mL SCF, 50 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and 25 ng/mL IL-3. After 2 weeks in culture, colonies were counted and replated at a dilution of 1:100. Two weeks later the secondary colonies were counted.

Cytospin preparations, flow cytometric analysis, and Western blot analysis

Cells grown in suspension culture were collected at days 7 and 14. For morphologic examination, cytospin slides were prepared by applying 1 × 104 cells onto glass slides followed by May-Grünwald and Giemsa staining. Cells harvested at the same time points were stained with allophycocyanin (APC)– or phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated antibodies against CD34, CD13, CD71, or CD235a (glycophorin A, GPA; BD Immunocytometry Systems) and analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur or FACSCanto (BD). Western blot was performed on cells harvested after 6 days in suspension culture. Details regarding the Western blot analysis are given in the supplemental Methods.

Gene-expression microarray analysis

2 days after transduction, GFP+ cells were collected in 3 biologic replicates and RNA was isolated using the RNeasy isolation kit (QIAGEN). RNA quality was assessed using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc). Samples were labeled, fragmented, and hybridized to Affymetrix U133 plus 2.0 microarrays (Affymetrix Inc) containing 54 000 probe sets representing approximately 38 500 genes according to the manufacturer's instructions. The data pre-processing is described in more detail in the supplemental Methods. Primary data from the gene-expression analysis is available at Gene Expression Omnibus (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo; accession number GSE15811).

Immunodeficient mouse xeno-transplantation assay

Human CD34+ CB cells were prestimulated and 2 to 4 × 105 cells/mouse were transduced with BCR/FGFR1, ZMYM2/FGFR1, or the MIG control vector as described in “Isolation, transduction, and sorting of cord blood CD34+ cells.” One day after transduction, unsorted transduced cells were injected via the tail vein or into the femur of sublethally (300-350 Rad) irradiated NOD/SCID, NOD/SCID B2m−/−, or NOD/SCID IL2–receptor gamma deficient (NSG) mice.18,19 After irradiation, the mice were given antibiotics (ciprofloxacin) and powder food. At 6 and 9 or 12 weeks after injection of human cells, BM was collected from femur and cells were double stained with APC-conjugated anti-CD45 and PE-conjugated anti-CD33/CD15, -CD34, or -CD235a (BD) antibodies, followed by flow cytometric analyses as described.20 The mice were killed at 9 to 12 weeks after injection of human cells, or earlier if found moribund. Spleen and femur (from leg not subjected to BM injection or aspiration) were collected in 4% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Slides were stained for reticulin, with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), or immunostained with antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD15, CD20, CD34, CD45, CD68, CD79a, CD117, CD235a, and myeloperoxidase (MPO; Dako). Antibodies used for immunostaining were controlled for cross-reactions with murine cells on BM sections from nontransplanted NOD/SCID control mice (supplemental Figure 5). Slides were analyzed using a Nikon Eclipse 50i microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc) with Plan Flour objective lenses (magnification/aperture 10×/0.30 and 40×/0.75). Micrographs were collected using a Pixera Pro 150 ES camera (Pixera Corp) and Viewfinder software (Pixera Corp). Subsequent adjustments in size and color balance of the pictures were made using Photoshop software (Adobe Systems Inc). BM sections were also examined using Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis as described in the supplemental Methods.

Results

Expression of ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1 in CD34+ CB cells leads to increased cellular proliferation and EPO-independent erythroid differentiation

To study the direct consequences of FGFR1 fusion genes on proliferation and differentiation in primitive cells, CD34+ CB cells were transduced with BCR/FGFR1 or ZMYM2/FGFR1. The P210 BCR/ABL1 fusion gene, associated with CML, was used as reference fusion oncogene. At 2 days after transduction, on average 39% of the BCR/FGFR1-transduced cells expressed GFP, 10% of the ZMYM2/FGFR1, 19% of the BCR/ABL1, and 36% of the MIG (n = 7; supplemental Figure 1A). Successful expression of fusion proteins was confirmed by Western blot analyses (supplemental Figure 1B).

CD34+ CB cells expressing ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1 or BCR/ABL1 increased in number 35 times more than MIG control cells during 2 weeks of suspension culture (Figure 1A). In contrast to the MIG cells that differentiated toward the myeloid lineage, mainly with a CD13-positive immunophenotype, ZMYM2/FGFR1-, BCR/FGFR1-, and BCR/ABL1-expressing cells differentiated into an erythroid phenotype (CD235a+, CD71+) in an EPO-independent manner (Figure 1B). Morphologic examination of cells from the suspension culture revealed that cells expressing either of the 3 fusion genes were at the pronormoblast stage of erythroid differentiation, consistent with our own and other investigators previous findings for BCR/ABL1 (Figure 1C).17,21,22 To investigate if the FGFR1 tyrosine kinase activity was required for the increased proliferation and erythroid differentiation, we constructed variants previously shown to abolish kinase activity.10,23 CD34+ CB cells that expressed BCR/FGFR1 Y653/654F or ZMYM2/FGFR1 Y653/654F did not display an increased proliferation or differentiation toward erythroid cells, suggesting that the kinase activity is crucial for the FGFR1 fusion oncogenic effects of the 2 fusion genes (Figure 1D and supplemental Figure 2).

Expression of ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1 in human CD34+ CB cells leads to increased cellular proliferation and erythroid differentiation. (A) Cells transduced with ZMYM2/FGFR1 (●), BCR/FGFR1 (■), or BCR/ABL1 (▴) increase in numbers approximately 35-fold compared with MIG control cells (○) during 14 days of suspension culture. Cells were counted at days 7 and 14 after sorting and the mean values of 3 separate experiments are shown. (B) The immunophenotype of cultured cells was assessed after 14 days of culturing. At this stage, cells expressing ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1 had become erythroid as shown by high levels of CD235a- and CD71-antigen expression. (C) Morphologic examination by May-Grünwald and Giemsa staining of cells on cytospin slides after 14 days of suspension culture shows that cells expressing either of the 3 fusion genes were at the pronormoblast stage of erythroid differentiation. (D) The proliferation rate of CD34+ CB cells expressing the kinase dead mutants BCR/FGFR1 653/654Y or ZMYM2/FGFR1 653/654Y (gray) was significantly reduced compared with cells expressing normal BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 (black) after 2 weeks of suspension culture. The result shown is the mean value from 3 separate experiments with MIG control cell expansion (white) set to 100%. Error bars show SD.

Expression of ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1 in human CD34+ CB cells leads to increased cellular proliferation and erythroid differentiation. (A) Cells transduced with ZMYM2/FGFR1 (●), BCR/FGFR1 (■), or BCR/ABL1 (▴) increase in numbers approximately 35-fold compared with MIG control cells (○) during 14 days of suspension culture. Cells were counted at days 7 and 14 after sorting and the mean values of 3 separate experiments are shown. (B) The immunophenotype of cultured cells was assessed after 14 days of culturing. At this stage, cells expressing ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1 had become erythroid as shown by high levels of CD235a- and CD71-antigen expression. (C) Morphologic examination by May-Grünwald and Giemsa staining of cells on cytospin slides after 14 days of suspension culture shows that cells expressing either of the 3 fusion genes were at the pronormoblast stage of erythroid differentiation. (D) The proliferation rate of CD34+ CB cells expressing the kinase dead mutants BCR/FGFR1 653/654Y or ZMYM2/FGFR1 653/654Y (gray) was significantly reduced compared with cells expressing normal BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 (black) after 2 weeks of suspension culture. The result shown is the mean value from 3 separate experiments with MIG control cell expansion (white) set to 100%. Error bars show SD.

To investigate whether the erythroid differentiation of the ZMYM2/FGFR1-, BCR/FGFR1-, and BCR/ABL1-expressing cells was related to specific properties of CB cells to commit to the erythroid lineage, the suspension culture experiment was repeated using normal human CD34+ BM cells, yielding a similar pattern of differentiation toward the erythroid lineage (data not shown). To study the effect on colony forming capacity, cells were cultured in methylcellulose medium. CD34+ CB cells expressing ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1 or BCR/ABL1 primarily gave rise to burst-forming units erythroid (BFU-E) colonies, whereas MIG control cells formed equal numbers of BFU-E and colony-forming units granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM) colonies (Figure 2A). After replating, cells expressing any of the 3 fusion genes almost exclusively gave rise to massive BFU-E colonies, in contrast to the few MIG control colonies formed, demonstrating that ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, and BCR/ABL1 increased the BFU-E colony forming capacity (Figure 2B).

Expression of ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1 in human CD34+ CB cells leads to expansion of erythroid colonies and induces similar but distinct gene-expression profiles. (A) Cells expressing ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1 mainly gave rise to BFU-E colonies after 2 weeks of culture in methylcellulose medium. (B) After replating of colonies, cells expressing a fusion gene almost exclusively formed BFU-E colonies. One representative experiment of 4 is shown. (C) Western blot analysis of STAT phosphorylation after 6 days suspension culture showing that ZMYM2/FGFR1 induced a much lower level of STAT5 phosphorylation than BCR/FGFR1 or BCR/ABL1 (left panel). The right panel shows an independent Western blot analysis, using longer exposure time, in which a weak but distinct band of phosphorylated STAT5 in ZMYM2/FGFR1-expressing cells is observed. Vimentin was used as an endogenous control for equal loading. (D-E) Venn diagrams showing the number of genes that are differentially expressed and commonly regulated in cells expressing ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1 compared with MIG control cells. (F) Cells co-expressing ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1 and an anti-STAT5 shRNA showed a significant reduction in cell proliferation after 7 days in suspension culture. The data are displayed as the mean cellular expansion for the anti-STAT5 shRNA-expressing cells in percentage of the corresponding control scramble shRNA-expressing cells from 3 separate experiments, with error bars representing SD.

Expression of ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1 in human CD34+ CB cells leads to expansion of erythroid colonies and induces similar but distinct gene-expression profiles. (A) Cells expressing ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1 mainly gave rise to BFU-E colonies after 2 weeks of culture in methylcellulose medium. (B) After replating of colonies, cells expressing a fusion gene almost exclusively formed BFU-E colonies. One representative experiment of 4 is shown. (C) Western blot analysis of STAT phosphorylation after 6 days suspension culture showing that ZMYM2/FGFR1 induced a much lower level of STAT5 phosphorylation than BCR/FGFR1 or BCR/ABL1 (left panel). The right panel shows an independent Western blot analysis, using longer exposure time, in which a weak but distinct band of phosphorylated STAT5 in ZMYM2/FGFR1-expressing cells is observed. Vimentin was used as an endogenous control for equal loading. (D-E) Venn diagrams showing the number of genes that are differentially expressed and commonly regulated in cells expressing ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1 compared with MIG control cells. (F) Cells co-expressing ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1 and an anti-STAT5 shRNA showed a significant reduction in cell proliferation after 7 days in suspension culture. The data are displayed as the mean cellular expansion for the anti-STAT5 shRNA-expressing cells in percentage of the corresponding control scramble shRNA-expressing cells from 3 separate experiments, with error bars representing SD.

We have previously demonstrated that BCR/ABL1-induced increase of erythroid cells is STAT5-dependent in CD34+ CB cells.17 Because ZMYM2/FGFR1 and BCR/FGFR1 expression in murine Ba/F3 cells results in STAT5 activation,9 we analyzed the phosphorylation pattern of STATs 3, 5, and 6 in cells after 6 days in suspension culture. Similar levels of STAT5 phosphorylation were detected for BCR/FGFR1 and BCR/ABL1, whereas ZMYM2/FGFR1 induced a much lower, but still detectable, level of phosphorylation of STAT5 (Figure 2C).

ZMYM2/FGFR1-, BCR/FGFR1-, and BCR/ABL1-expressing cells display similar but distinct gene-expression profiles

To study the deregulation of transcriptional programs induced by FGFR1 fusion genes, global gene-expression analysis on cells expressing ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, BCR/ABL1, or the MIG control vector was performed. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering revealed a clear separation into 2 main clusters, with one comprising the biologic replicates of MIG and the other the 3 fusion oncogenes, thus demonstrating a fundamental difference in their gene expression profiles (supplemental Figure 3A). Notably, in a supervised multiclass SAM analysis, comparing the 3 biologic replicates of MIG, ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1, cells expressing the 3 different fusion genes also formed separate subclusters indicating a smaller, but significant, difference in their expression profiles (supplemental Figure 3B).

Two-class unpaired SAM analysis, comparing MIG with each of the 3 fusion gene-expressing cells separately, identified 77 commonly up-regulated genes at a FDR of < 1% (Figure 2D; supplemental Table 1). Gene ontology analysis of these 77 genes revealed that signal transducer activity was the main top-ranked category (25 genes, Ease score 3.08 × 10-4). Notably, as many as 11 of the 77 genes (14%) were involved in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, including CISH, LEPR, LIF, OSM, PIM1, SOCS1-3, SOS1, and the interleukin receptors IL2RB and IL7R. In parallel, 74 genes were found to be commonly down-regulated by ZMYM2/FGFR1, BCR/FGFR1, and BCR/ABL1 compared with MIG (Figure 2E; supplemental Table 2). Although many genes were commonly regulated in the fusion gene-expressing cells, the individual fusion genes still displayed distinct gene-expression profiles with ZMYM2/FGFR1 and BCR/FGFR1 being more similar than BCR/ABL1 using multiclass SAM analysis (supplemental Figure 3B).

Silencing of STAT5 with shRNA results in decreased proliferation of cells expressing BCR/FGFR1, ZMYM2/FGFR1, or BCR/ABL1

We have previously demonstrated that BCR/ABL1-induced cell proliferation and erythroid differentiation in human CD34+ CB cells is partially STAT5 dependent.17 In this study, gene expression profiling revealed that BCR/FGFR1, ZMYM2/FGFR1, and BCR/ABL1 all up-regulated several genes involved in JAK/STAT signaling. This finding agreed well with our Western blot data demonstrating a clear STAT5 phosphorylation for BCR/FGFR1 and BCR/ABL1, while ZMYM2/FGFR1 unexpectedly showed a markedly lower level of STAT5 phosphorylation. To study mechanistically if STAT5 activation was equally important for the 3 different fusion oncogenes in terms of their effects on cellular proliferation, we cotransduced CD34+ CB cells with anti-STAT5 shRNA and the different fusion genes. After sorting of GFP+/RFP+ cells as previously described,17 a significant decrease in cell proliferation was observed for all 3 fusion oncogenes (Figure 2F). Moreover, negative effects in erythroid differentiation and colony formation were observed after STAT5 silencing, but as similar effects on MIG control cells were observed (data not shown), it is currently unclear to what extent these effects are related to the fusion genes. Nevertheless, the strong dependence on STAT5 for inducing cell proliferation by cells expressing all 3 fusion genes, suggests that STAT5 activation is an important mechanism whereby FGFR1 fusion oncogenes elicit their transforming effects.

BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 induce a human EMS-like disorder in mice

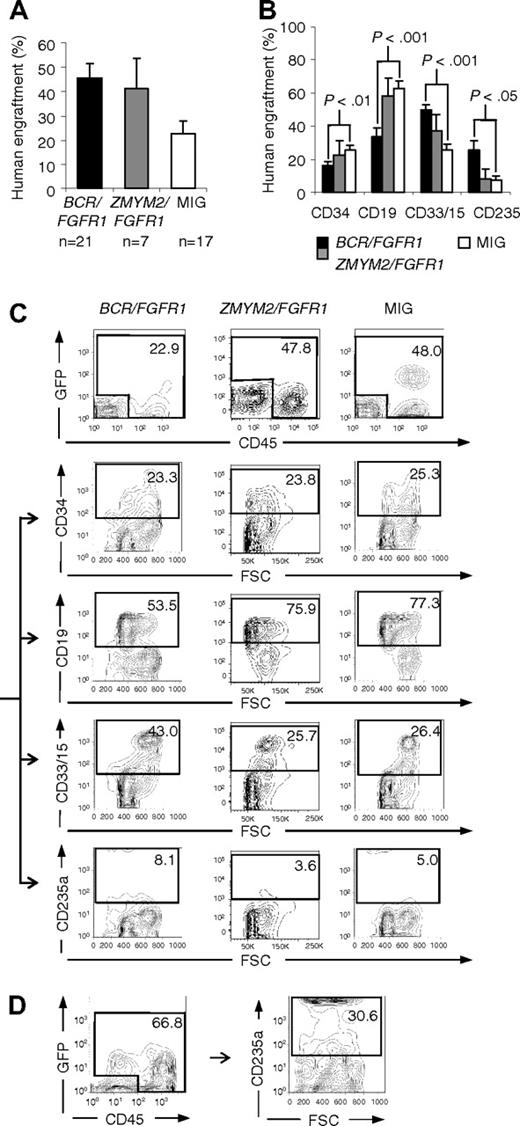

To investigate how FGFR1 fusion oncogenes affects primary human cells in vivo, CD34+ CB cells expressing BCR/FGFR1, ZMYM2/FGFR1, or the MIG control vector were transplanted into immunodeficient NOD/SCID or NOD/SCID B2m−/− mice, hereafter referred to as BCR/FGFR1 mice, ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice, or MIG mice. In a second set of experiments, we also used the more severely immunocompromised NSG mouse strain. 6 weeks after transplantation into NOD/SCID or NOD/SCID B2m−/− mice, the engraftment of human cells (GFP+ and/or CD45+) in the mouse BM was on average 46% for BCR/FGFR1, 41% for ZMYM2/FGFR1, and 22% for MIG control (Figure 3A). No difference in engraftment of human cells related to mouse strain, or if tail vein or intrafemoral injections were used, was noted (supplemental Table 3 and data not shown). BCR/FGFR1 expression directed the human cells toward an increased myeloid and erythroid cell fate as shown by higher levels of CD33/CD15 and CD235a, whereas ZMYM2/FGFR1 at this stage did not differ significantly from the MIG control (Figure 3B-D). At 9 to 12 weeks after transplantation, the ZMYM2/FGFR1-induced effects were similar to that observed for BCR/FGFR1, including increased levels of human myeloid and erythroid cells (supplemental Figure 4).

Flow cytometric analysis of human cells in NOD/SCID mouse BM around 6 weeks after transplantation reveals that BCR/FGFR1 expression directs the differentiation to myeloid and erythroid cell fates. (A) Engraftment at 6 to 7 weeks after transplantation of human cells transduced with BCR/FGFR1, ZMYM2/FGFR1, or the MIG control vector. (B) Phenotype of human cells in the BM of BCR/FGFR1 (black), ZMYM2/FGFR1 (gray), or MIG (white) mice at 6 to 7 weeks after transplantation, revealing that BCR/FGFR1 significantly directs grafted cells toward the myeloid and erythroid cell lineages. Data are presented as the mean value of all analyzed mice with error bars representing SEM (for data at 9-12 weeks after transplantation, see supplemental Figure 4B). (C) FACS plots showing the gating and differentiation pattern of human cells (GFP+ and/or CD45+; top panel) in BM from representative MIG, ZMYM2/FGFR1, or BCR/FGFR1 mice, as detected by cell surface expression of CD34, CD19, CD33/15, and CD235a. (D) FACS plot showing increased erythroid differentiation of human cells in BM of an additional BCR/FGFR1 mouse.

Flow cytometric analysis of human cells in NOD/SCID mouse BM around 6 weeks after transplantation reveals that BCR/FGFR1 expression directs the differentiation to myeloid and erythroid cell fates. (A) Engraftment at 6 to 7 weeks after transplantation of human cells transduced with BCR/FGFR1, ZMYM2/FGFR1, or the MIG control vector. (B) Phenotype of human cells in the BM of BCR/FGFR1 (black), ZMYM2/FGFR1 (gray), or MIG (white) mice at 6 to 7 weeks after transplantation, revealing that BCR/FGFR1 significantly directs grafted cells toward the myeloid and erythroid cell lineages. Data are presented as the mean value of all analyzed mice with error bars representing SEM (for data at 9-12 weeks after transplantation, see supplemental Figure 4B). (C) FACS plots showing the gating and differentiation pattern of human cells (GFP+ and/or CD45+; top panel) in BM from representative MIG, ZMYM2/FGFR1, or BCR/FGFR1 mice, as detected by cell surface expression of CD34, CD19, CD33/15, and CD235a. (D) FACS plot showing increased erythroid differentiation of human cells in BM of an additional BCR/FGFR1 mouse.

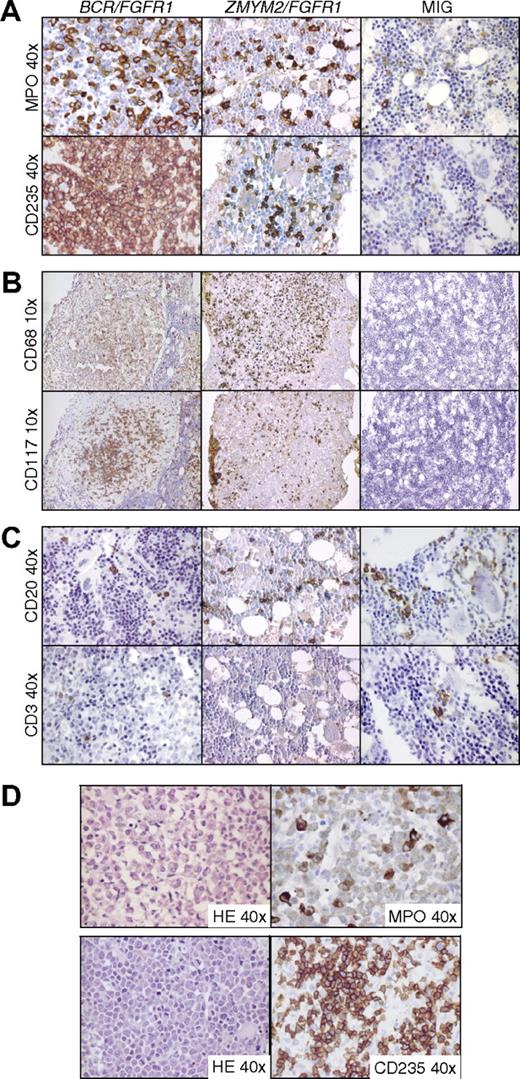

To investigate the fusion oncogene-induced histopathologic changes in NOD/SCID and NOD/SCID B2m−/− mice in more detail, femurs and spleens from 15 BCR/FGFR1 mice, 6 ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice, and 12 MIG mice were harvested at 6 to 12 weeks after transplantation. In agreement with the flow cytometric data, HE and MPO staining revealed expansion of the human myeloid cell compartment in BCR/FGFR1 mice together with an increase in erythroid (CD235a+) cells (Figure 4A and supplemental Figure 5A). Similar, but less pronounced effects were seen in ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice. In 14 of the 15 BCR/FGFR1 mice, and in 5 of 6 ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice, we found clusters (foci) of histiocytes/macrophages as defined by CD68 staining and morphology (Figure 4B and supplemental Figure 5B). These clusters, which typically were more pronounced in BCR/FGFR1 mice, also contained human mast cells as determined by staining for CD68 and CD117 (c-kit), and morphology (Figure 4B and supplemental Figure 5B). The human origin of the cells in these foci was confirmed by FISH using probes specific for human or mouse centromeres (supplemental Figure 5B). The expansion of the different myeloid lineages varied, with some mice displaying a pronounced accumulation of macrophages and mast cells, whereas others showed a more prominent expansion of granulocytic cells, possibly being a result of either the type of cells being targeted by the 2 fusion genes or by variability in CB donors.

Immunostained BM sections from BCR/FGFR1, ZMYM2/FGFR1, and MIG NOD/SCID mice. (A) BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice display increased levels of human granulocytic and erythroid cells in BM as shown by immunostaining for MPO and CD235a. BM sections from a representative MIG mouse reveal single granulocytic and erythroid human cells staining positive for MPO and CD235a. (B) Human cells in BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice BM also differentiated into macrophages and mast cells as shown by morphology and positive staining for CD68 and CD117 in BM sections from representative mice. Typically, macrophages and mast cells formed round clusters of cells. In MIG mice, only few cells stained positive for CD68 or CD117. (C) In BM sections from BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice, as well as from MIG mice, dispersed B-lymphoid cells, staining positive for CD20 were found, whereas T-lymphoid cells positive for CD3 were more rarely detected. (D) In BCR/FGFR1 mice, human granulocytopoiesis frequently displayed a left-shifted maturation pattern with eosinophilia, as shown by morphology in HE stained sections and immunostaining for MPO (top panel). Furthermore, accumulation of erythroid blasts as shown in HE stained sections and by CD235a staining was observed (bottom panel).

Immunostained BM sections from BCR/FGFR1, ZMYM2/FGFR1, and MIG NOD/SCID mice. (A) BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice display increased levels of human granulocytic and erythroid cells in BM as shown by immunostaining for MPO and CD235a. BM sections from a representative MIG mouse reveal single granulocytic and erythroid human cells staining positive for MPO and CD235a. (B) Human cells in BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice BM also differentiated into macrophages and mast cells as shown by morphology and positive staining for CD68 and CD117 in BM sections from representative mice. Typically, macrophages and mast cells formed round clusters of cells. In MIG mice, only few cells stained positive for CD68 or CD117. (C) In BM sections from BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice, as well as from MIG mice, dispersed B-lymphoid cells, staining positive for CD20 were found, whereas T-lymphoid cells positive for CD3 were more rarely detected. (D) In BCR/FGFR1 mice, human granulocytopoiesis frequently displayed a left-shifted maturation pattern with eosinophilia, as shown by morphology in HE stained sections and immunostaining for MPO (top panel). Furthermore, accumulation of erythroid blasts as shown in HE stained sections and by CD235a staining was observed (bottom panel).

Human lymphoid cells in both BCR/FGFR1 mice and ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice were frequently found to be B-lymphocytic, as shown by staining for CD20 (Figure 4C). T cells positive for CD3 and CD4 were more rarely seen (Figure 4C). In 10 of the 15 BCR/FGFR1 mice, human granulocytopoiesis displayed a left-shifted maturation pattern with marked expansion of myeloid cells at all stages of maturation, including eosinophilia, which is in agreement with findings described in the chronic phase of human EMS7 (Figure 4D). Interestingly, 3 of the BCR/FGFR1 animals displayed an accumulation of human blasts in the BM (Figure 4D). In 2 of the 3 animals, the blasts stained strongly positive for CD235a, suggesting the emergence of an acute erythroleukemia in these mice (Figure 4D). In 1 of these animals, the CD235a+ blasts coexpressed CD117 indicating a more immature phenotype (data not shown). In the third mouse, the blast refrained staining with all antibodies used (CD3, CD4, CD15, CD20, CD34, CD45, CD68, CD79a, CD117, CD235a, and MPO) suggesting an immature and primitive origin of these blasts (data not shown). All examined MIG mice (n = 12) displayed a relatively normal BM hematopoiesis with dispersed lymphoid and single granulocytic and erythroid human cells. (Figure 4A-C).

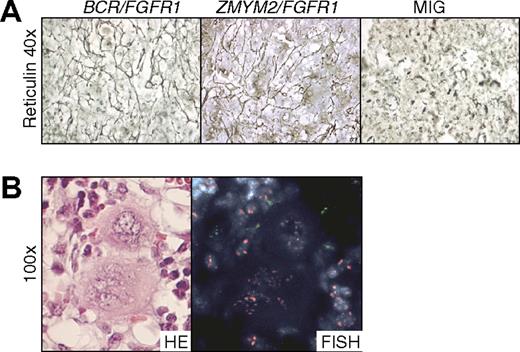

Eleven of the 15 BCR/FGFR1 mice and 1 of the 6 ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice suffered from mild to severe BM fibrosis as shown by reticulin and HE staining (Figure 5A and data not shown). The numbers of megakaryocytes in the BM were most often normal in count, but sometimes displayed abnormal nuclei in BCR/FGFR1 mice. In accordance with what has been shown for TEL/JAK2 in a similar experimental model,12 the megakaryocytes were of murine origin as determined by FISH (Figure 5B).

NOD/SCID mice transplanted with BCR/FGFR1- and ZMYM2/FGFR1-expressing cells display BM fibrosis. (A) Reticulin-stained BM sections from a representative BCR/FGFR1 mouse and a ZMYM2/FGFR1 mouse reveal pronounced fibrosis, whereas all MIG mice displayed normal reticulin. (B) Two representative megakaryocytes from BCR/FGFR1 mouse BM shown to be of murine origin as determined by FISH analysis (red signals, murine cells; green signals, human cells).

NOD/SCID mice transplanted with BCR/FGFR1- and ZMYM2/FGFR1-expressing cells display BM fibrosis. (A) Reticulin-stained BM sections from a representative BCR/FGFR1 mouse and a ZMYM2/FGFR1 mouse reveal pronounced fibrosis, whereas all MIG mice displayed normal reticulin. (B) Two representative megakaryocytes from BCR/FGFR1 mouse BM shown to be of murine origin as determined by FISH analysis (red signals, murine cells; green signals, human cells).

Similar to patients with MPD, splenomegaly, consistent with an increased extramedullary hematopoiesis, was detected in several BCR/FGFR1 mice, but not in ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice (supplemental Figure 6A). In most cases the same abnormalities seen in the BM were also observed in the spleen, for example, expansion of human granulocytopoietic and erythropoietic cells and foci containing macrophages and mast cells (supplemental Figure 6B). Of the 21 BCR/FGFR1 mice, 7 died due to disease during the study. Histopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis was performed on 5 of these animals, all displaying the characteristic features of disease, that is, left-shifted granulocytopoiesis with eosinophilia, BM fibrosis, and splenomegaly. Three of the dead animals showed accumulation of blasts in the BM. Peripheral blood examination during the disease course did not, however, reveal elevated white blood cell counts in any of the examined animals (data not shown).

None of the abnormalities observed in the BM or spleen of the BCR/FGFR1 or ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice were found in any of the MIG mice, and no MIG control mice died due to disease during the study.

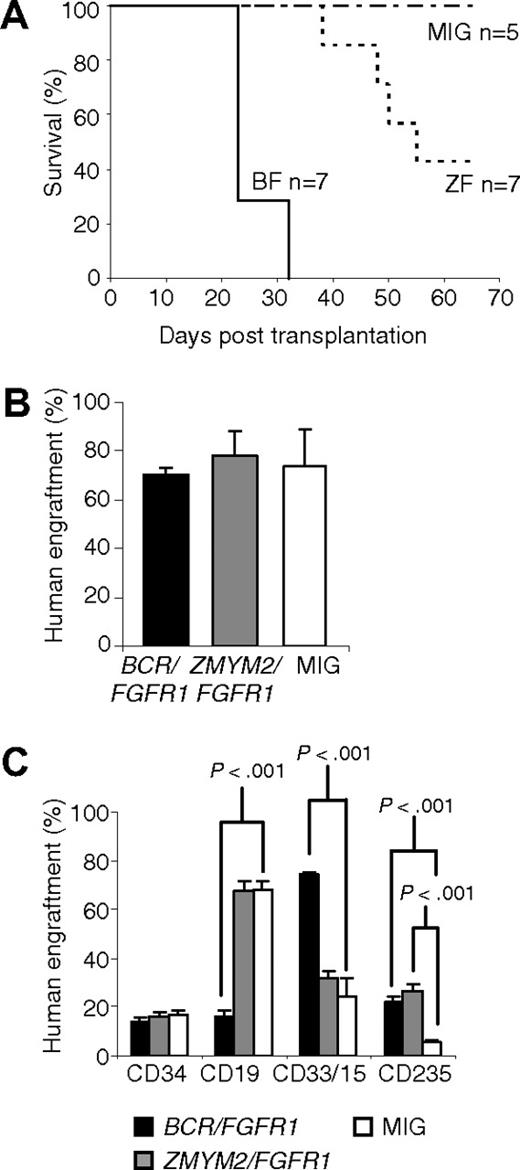

Because the disease phenotype in ZMYM2/FGFR1 NOD/SCID mice was relatively weak compared with BCR/FGFR1, we also transplanted human CD34+ cells transduced with BCR/FGFR1, ZMYM2/FGFR1, or the MIG control into NSG mice. Whereas the BCR/FGFR1 mice all died of disease at days 23 to 32 after transplantation, most likely because of BM insufficiency caused by human myeloid cell expansion and/or fibrosis, the ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice survived until day 38 or longer (Figure 6A). The NSG mice displayed on average approximately 70% human cells, irrespectively if the mice were transplanted with cells expressing BCR/FGFR1, ZMYM2/FGFR1, or the MIG control (Figure 6B and supplemental Table 3). The increase in human myeloid and erythroid cells observed in BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 NSG mice was typically more pronounced than seen in NOD/SCID mice (Figure 6C). Immunostainings of BM sections were similar to NOD/SCID mice (supplemental Figure 7). Both fusion oncogenes induced an MPD-like disorder with left-shifted granulocytopoiesis, sometimes accompanied by eosinophilia and/or dysplastic megakaryocytes (data not shown). BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 NSG mice generally suffered from mild to severe BM fibrosis and displayed foci of human histiocytes and mast cells (supplemental Figure 7). Two BCR/FGFR1 and 1 ZMYM2/FGFR1 mouse showed blast expansion in bone marrow and/or spleen (supplemental Figure 8). These blasts stained positive for CD235a and CD117 (supplemental Figure 8 and data not shown). None of the NSG MIG control mice died due to disease during the study. There were no signs of lymphoid disease in any of the mice, irrespectively of the fusion gene used.

Results from NSG mice transplanted with human cells expressing BCR/FGFR1 or ZMYM2/FGFR1. (A) BCR/FGFR1 mice all died at day 32 or earlier, whereas ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice survived longer. All MIG control mice, and 3 ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice survived until end of study. (B) The engraftment of human cells was on average 70% in BCR/FGFR1 mice, 74% in ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice, and 78% in MIG control mice at end of life (23-65 days). Error bars represents SEM. (C) The percentage of human myeloid (CD33/15+) cells was significantly higher in BCR/FGFR1 mice (black), but not in ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice (gray), compared with MIG control mice (white). The erythroid cell lineage (CD235a+) was pronounced in both BCR/FGFR1 mice and ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice. Data are presented as the mean value of all analyzed mice with error bars representing SEM.

Results from NSG mice transplanted with human cells expressing BCR/FGFR1 or ZMYM2/FGFR1. (A) BCR/FGFR1 mice all died at day 32 or earlier, whereas ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice survived longer. All MIG control mice, and 3 ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice survived until end of study. (B) The engraftment of human cells was on average 70% in BCR/FGFR1 mice, 74% in ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice, and 78% in MIG control mice at end of life (23-65 days). Error bars represents SEM. (C) The percentage of human myeloid (CD33/15+) cells was significantly higher in BCR/FGFR1 mice (black), but not in ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice (gray), compared with MIG control mice (white). The erythroid cell lineage (CD235a+) was pronounced in both BCR/FGFR1 mice and ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice. Data are presented as the mean value of all analyzed mice with error bars representing SEM.

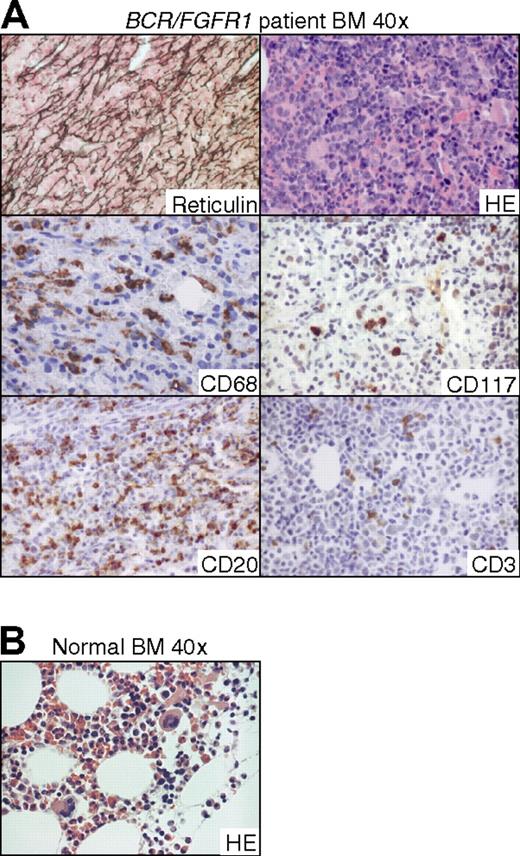

Given the close similarities in BM morphology between the BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice and patients with EMS described in the literature,24 we reexamined a BM biopsy taken from an EMS patient in which we originally isolated the BCR/FGFR1 fusion gene (Figure 7).16,25 At the stage when the EMS had progressed into acute leukemia, the reticulin stained section revealed a pronounced increase of reticulin. Furthermore, HE staining revealed eosinophilia and infiltration of blasts that on immunohistochemical staining were negative for all antibodies tested (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD15, CD20, CD34, CD45, CD68, CD79a, CD117, CD235, MPO, and TdT). This suggests an immature but otherwise unclassifiable phenotype of the blasts, similar to the finding in 1 of the NOD/SCID BCR/FGFR1 mice with blast accumulation. Notably, numerous macrophages (CD68+) and occasional mast cells (CD68+/CD117+) were found. In agreement with our finding in the immunodeficient mice, CD20+ B cells were more frequent than CD3+ T cells in the patient's BM.

BM sections from the patient in which the BCR/FGFR1 fusion gene originally was isolated show similarities with BCR/FGFR1-induced effects in the NOD/SCID and NSG mouse models. (A) Reticulin-stained section demonstrates a pronounced BM fibrosis and HE staining shows infiltration of blasts (top panel). Numerous macrophages staining positive for CD68 and occasionally mast cells, as defined by morphology and CD117 staining, are also found (middle panel). CD20+ B cells are more frequent than CD3+ T cells (bottom panel). Due to admixture of peripheral erythrocytes, a CD235 stained section could not be conclusively analyzed. (B) HE-stained section from a normal healthy BM.

BM sections from the patient in which the BCR/FGFR1 fusion gene originally was isolated show similarities with BCR/FGFR1-induced effects in the NOD/SCID and NSG mouse models. (A) Reticulin-stained section demonstrates a pronounced BM fibrosis and HE staining shows infiltration of blasts (top panel). Numerous macrophages staining positive for CD68 and occasionally mast cells, as defined by morphology and CD117 staining, are also found (middle panel). CD20+ B cells are more frequent than CD3+ T cells (bottom panel). Due to admixture of peripheral erythrocytes, a CD235 stained section could not be conclusively analyzed. (B) HE-stained section from a normal healthy BM.

Discussion

To study aberrant tyrosine kinases underlying human MPD, investigators have long been entirely dependent on leukemic cell lines and murine assays. Although these functional studies have contributed significantly to our knowledge regarding disease mechanisms in human MPD, there are noticeable limitations in both systems as cell lines typically acquire additional genetic aberrations for continuous growth in vitro, and tumorigenesis may differ substantially in human and mouse.14,26,27

In this study we assessed the consequences of ectopic FGFR1 fusion gene expression in the cellular context of normal primitive human hematopoietic cells. CD34+ CB cells expressing ZMYM2/FGFR1 or BCR/FGFR1 displayed EPO-independent erythroid differentiation and significant proliferation capacity in vitro. Importantly, we hereby establish the first human in vivo EMS model by transplanting ZMYM2/FGFR1- and BCR/FGFR1-expressing CB cells into immunodeficient mice. In this model, primitive human cells expressing the 2 fusion oncogenes induce an MPD-like disorder, accompanied by bone marrow fibrosis and accumulation of blasts, thereby closely resembling the disease features observed in EMS patients. An alternative approach to establish a human EMS disease model would be to transplant immunodeficient mice with primary cells obtained from EMS patients. Such studies have been performed using chronic phase CML cells, but in general, high-level engraftment and a faithful recapitulation of morphologic and clinical features observed in CML patients has been difficult to achieve.28-30 Moreover, the relatively rare occurrence of human EMS, and the fact that EMS in many cases is diagnosed in the late AML or ALL stage of the disease, severely limit similar types of studies.

Upon retroviral expression of ZMYM2/FGFR1 or BCR/FGFR1 in normal human CD34+ CB cells we found an FGFR1 kinase dependent increased proliferation capacity and EPO-independent erythroid differentiation in vitro, which is similar to BCR/ABL1-induced effects and consistent with previously reported findings for BCR/ABL1.17,21,22,31,32 This suggests that the BCR/ABL1 and FGFR1 fusion genes, at least partly, mediate their leukemogenic effects in a similar manner. In agreement with this, global gene-expression analysis confirmed that the 3 fusion oncogenes induced similar transcriptional responses with activation of genes involved in the JAK-STAT pathway. Moreover, all 3 fusion genes induced an increase of immature human erythroid cells. To test whether the erythroid bias of the fusion gene expressing cells was caused by a preferential retroviral targeting of early erythroid progenitor cells, we also included nontransduced control cells in the experiments. As the outcome of sorted GFP+ MIG transduced cells did not differ significantly from the nontransduced cells, we conclude that the erythroid phenotype was not induced by a preferential targeting of erythroid committed cells during the transduction procedure (data not shown). Although the erythroid phenotype may seem unexpected, it is well-known that primary cells from CML patients form EPO-independent BFU-E colonies and that chronic phase CML patients display an increase of megakaryocyte and erythroid progenitor (MEP) cells.32,33 Interestingly, similar in vitro studies of primary cells from patients with EMS have been shown to increase the number of BFU-E colonies in the absence of EPO.3

We have previously demonstrated that BCR/ABL1-induced erythroid differentiation and proliferation in human CD34+ CB cells is STAT5-dependent,17 and it could be speculated that the FGFR1 fusion genes also mediate their effect through a similar mechanism. Unexpectedly, the level of STAT5 phosphorylation was markedly lower in ZMYM2/FGFR1-expressing cells compared with BCR/FGFR1 and BCR/ABL1. Despite the differences in STAT5 phosphorylation, global gene-expression profiling revealed that all 3 fusion genes up-regulated several genes involved in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway as well as other sets of genes, indicating that these fusion proteins share similar molecular programs. Using lentiviral STAT5 shRNA constructs, we were able to demonstrate a significant effect on the proliferation rate of cells expressing either of the 3 oncogenes, suggesting that STAT5, in addition to its well-documented role in CML,34 also plays an important role in FGFR1-mediated leukemogenesis.

Upon transplantation of CD34+ cells into immunodeficient mice, BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 expression rapidly lead to an increase of a variety of cell types including granulocytes, erythroid cells, macrophages, and mast cells. This suggests that expression of FGFR1 fusion oncogenes induce proliferation and differentiation of multiple myeloid cell lineages. Importantly, BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 expression induced a marked increase of human granulocytopoietic cells at all stages of maturation with eosinophilia and dysplastic megakaryocytes also being observed. Furthermore, splenomegaly and increased extramedullary hematopoiesis was seen. Altogether, the FGFR1 fusion oncogene-induced disease in mice in many ways closely resembles human EMS as these features all are key characteristics in this MPD subtype.7 Moreover, blast accumulation in the BM or spleen of several mice suggest that the MPD was about to transform into AML. We failed to graft these blasts in secondary recipients through intravenous injections, suggesting that they were not fully immortalized blasts (data not shown), perhaps requiring secondary aberrations to become fully transformed. However, the short latency from transplantation to disease onset in this model indicates that FGFR1 fusion oncogenes by themselves have the ability to induce, at least, the chronic phase of the disease. Albeit ZMYM2/FGFR1 generally induced weaker phenotypic changes with longer survival of the mice compared with BCR/FGFR1, both fusion oncogenes induced similar disease phenotypes in immunodeficient mice. It is possible that the less pronounced disease pattern seen in ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice could be explained by the markedly lower transduction efficiency achieved with the ZMYM2/FGFR1 expressing retrovirus, thus our observations do not necessarily indicate that BCR/FGFR1 is a more potent oncogene than ZMYM2/FGFR1.

Although the disease in mice much resembles human EMS, 3 distinct differences between the established model and human EMS are notable. First, patients with EMS often display a bilinear disease involving both the myeloid and the T-lymphoid lineage. We here failed to demonstrate a significant involvement of the human T-cell lineage in the immunodeficient mice. However, this may be explained by the inability of adult mice of both the NOD/SCID and the NSG strains to support T-lymphopoiesis after receiving transplants with human cells, possibly due to improper thymus development in these mice.19,35 Moreover, while T-cell involvement has been primarily reported in patients expressing ZMYM2/FGFR1, to our knowledge no EMS patient harboring a BCR/FGFR1 fusion gene has been reported to suffer from T-cell lymphoma/leukemia.15,16,36-43 Secondly, the accumulation of macrophages and mast cells in the BM of both BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice may seem unexpected. However, when reviewing published cases with EMS, presence of mast cells in the BM and systemic mastocytosis have been reported in 2 cases.44,45 Upon reexamination of our previously described patient with EMS harboring a BCR/FGFR1 fusion gene,16,25 numerous mast cells and macrophages were found in the BM, although no prominent foci-like formations, as seen in the animal model, were observed. It is also interesting to note that mast cells often are enriched in eosinophilic myeloproliferative neoplasms caused by the closely related fusion genes involving PDGFRA/B.46 Thirdly, in 5 of 6 animals with blast accumulation, the blasts displayed an erythroid phenotype. This is consistent with our in vitro studies that demonstrated a strong erythroid potential of BCR/FGFR1- and ZMYM2/FGFR1-expressing cells. So far, FGFR1 fusion genes have not been associated with erythroleukemia, but we note with interest that 2 EMS patients were diagnosed with polycythemia vera, and 1 additional case developed erythroid BM hyperplasia.47-49 In analogy with CML that may transform into an acute erythroleukemia,50 we further speculate that kinase activating mutations of FGFR1 may be found in a fraction of acute erythroleukemia, representing an acute phase of an undiagnosed EMS chronic phase.

Global gene-expression analysis strongly indicated that both BCR/FGFR1 and ZMYM2/FGFR1 activates the JAK-STAT pathway, and the myelofibrosis seen in BCR/FGFR1 mice and ZMYM2/FGFR1 mice is similar to a recently described study in which human primary hematopoietic cells expressing the TEL/JAK2 fusion gene were transplanted into NOD/SCID mice.12 Both our studies found atypical megakaryocytes of murine origin, suggesting that expression of a fusion oncogene such as BCR/FGFR1 or TEL/JAK2 in human cells can have cell nonautonomous effects on the mouse megakaryocytic lineage, perhaps contributing to fibrosis. In accordance with our in vivo findings, fibrosis in the BM has been reported in 3 described EMS cases verified to harbor the BCR/FGFR1 fusion gene.15,16

In conclusion, we demonstrate that FGFR1 fusion genes have the potential to support EPO-independent erythroid development in a similar manner as BCR/ABL1. More importantly, we have established a human in vivo model of EMS by introducing BCR/FGFR1- or ZMYM2/FGFR1-expressing human CD34+ CB cells into immunodeficient mice. We show that BCR/FGFR1 or ZMYM2/FGFR1 expression alone induces rapid histopathologic changes that resemble several characteristic features observed in EMS patients, including increased granulocytopoiesis, eosinophilia, blast accumulation, and increased extramedullary hematopoiesis. Notably, this is the first humanized model of an MPD with features indicative of progression into an acute phase. As such it should constitute a valuable tool for obtaining further insights into FGFR1 fusion gene mediated leukemogenesis and for the development and evaluation of new treatment strategies in EMS.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ing-Britt Åstrand-Grundström of the Hematopoietic Stem Cell Laboratory, Lund University, for technical assistance with the cytospin slides; the staff of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lund, for collecting umbilical cord blood samples; and Jonas Larsson, Department of Molecular Medicine and Gene Therapy, for generously sharing the NSG mice.

This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Children's Cancer Foundation, the Inga-Britt and Arne Lundberg Foundation, the Gunnar Nilsson Cancer Foundation, the Medical Faculty of Lund University, and the Swedish Research Council (personal project grants to T.F.; Hemato-Linné and BioCare strategic program grants).

Authorship

Contribution: H.Å., M.J., and T.F. designed the research and wrote the manuscript; and H.Å., M.J., A.A., P.J., N.H., C.L., M.R., D.G., T.O., J.R., X.F., M.E., and T.F. performed the research and analyzed the data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Helena Ågerstam and Thoas Fioretos, Department of Clinical Genetics, Skåne University Hospital, SE-221 85, Lund, Sweden; e-mail: helena.agerstam@med.lu.se and thoas.fioretos@med.lu.se.