Abstract

An animal model of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) will help characterize leukemic and normal stem cells and also help evaluate experimental therapies in this disease. We have established a model of CML in the NOD/SCID mouse. Infusion of ≥4 × 107chronic-phase CML peripheral blood cells results in engraftment levels of ≥1% in the bone marrow (BM) of 84% of mice. Engraftment of the spleen was seen in 60% of mice with BM engraftment. Intraperitoneal injection of recombinant stem cell factor produced a higher level of leukemic engraftment without increasing Philadelphia-negative engraftment. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor did not increase the level of leukemic or residual normal engraftment. Assessment of differential engraftment of normal and leukemic cells by fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis with bcr and abl probes showed that a median of 35% (range, 5% to 91%) of engrafted cells present in the murine BM were leukemic. BM engraftment was multilineage with myeloid, B-cell, and T-cell engraftment, whereas T cells were the predominant cell type in the spleen. BM morphology showed evidence of eosinophilia and increased megakaryocytes. We also assessed the ability of selected CD34+ CML blood cells to engraft NOD/SCID mice and showed engraftment with cell doses of 7 to 10 × 106 cells. CD34− cells failed to engraft at cell doses of 1.2 to 5 × 107. CD34+ cells produced myeloid and B-cell engraftment with high levels of CD34+ cells detected. Thus, normal and leukemic stem cells are present in CD34+ blood cells from CML patients at diagnosis and lead to development of the typical features of CML in murine BM. This model is suitable to evaluate therapy in CML.

CHRONIC MYELOID LEUKEMIA (CML) is a disorder of the hematopoietic stem cell characterized by the presence of the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome,1 which is produced by a translocation between the abl proto-oncogene on chromosome 92 and the bcr gene on chromosome 22.3Chromosomal and isoenzyme studies have shown the involvement of the granulocytic, monocytic, erythroid, megakaryocytic, and B-lymphocytic lineages, confirming the origin of CML in a pluripotent hematopoietic stem cell (HSC).4 Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is currently the only curative treatment for CML, but age and donor availability restrict this therapy to approximately 25% of patients.5 For the remaining patients, the disease is incurable, although interferon may improve survival.6

Despite the multilineage involvement in CML, there is preferential expansion of the myeloid and megakaryocyte compartments that results from an increase in the number of colony-forming cells in the BM and peripheral blood (PB).7 However, at the primitive hematopoietic cell level, CML BM contains reduced numbers of long-term culture-initiating cells (LTC-IC) compared with normal BM, but there is an exponential increase in LTC-IC in the PB.8 The overgrowth of leukemic cells in the BM and PB does not completely eradicate normal hematopoietic cells in CML. Growth of CML BM on allogeneic stroma results in decline of Ph+ cells, and, after 4 to 5 weeks, hematopoiesis is predominantly Ph−.9 In CML, as in normal subjects,10 the CD34+ HLA-DR−and CD34+ CD38− fractions of BM contain cells that have properties of HSC. We have previously shown thatbcr-abl− preprogenitors are present in these fractions in both CML BM and PB.11 Furthermore, this residual normal stem cell compartment is present in most patients at diagnosis but as the disease progresses it gradually disappears.12,13 Available evidence suggests that these normal cells are extremely rare, and there is concern whether they are clonal cells that have not yet acquired the Ph chromosome14or do not express bcr-abl.15 There is preliminary evidence that the CD34+HLA-DR− compartment is polyclonal in early, but not in late, chronic-phase CML.16

The critical biologic differences between Ph+ and Ph− primitive progenitors that have been identified can be used to develop purging strategies or novel therapies such as selection of cells based on phenotype11,17,18 or depletion of leukemic cells by cell culture,19 chemotherapeutic agents,20 antisense oligonucleotides,21 or ribozymes.22 However, it is necessary to test these biologic differences at the stem cell level. The survival of normal and leukemic stem cells after specific manipulations can be assessed by their ability to engraft immunodeficient mice.

Various strains of immunodeficient mice have been used to study normal hematopoiesis. Umbilical cord blood progenitors engraft severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice without any requirement for exogenous cytokine.23 In contrast, adult BM only engrafts SCID mice in the presence of human stroma24 or after exogenous cytokine administration.25 Cytokines are also necessary in the mouse model of acute myeloid leukemia,26,27 but acute lymphoblastic leukemia engrafts SCID mice without cytokine.28 Mouse models of CML have been more difficult to establish. Infusion of blast crisis CML cell lines, such as K562,29 EM-2,29 BV173,30 or KBM-5,31 causes disseminated leukemia in SCID mice. Similarly, cells from CML patients in blast crisis engraft and disseminate in SCID mice.29 Initial studies using chronic-phase CML cells at doses of 1 to 5 × 107 administered intravenously (IV), administered intraperitoneally (IP), or implanted under the kidney capsule resulted in local recovery of cells administered IP only.29 This failure of engraftment may be a result of the low cell dose administered, because Sirard et al32 have shown mean engraftment levels of 0.02% to 10% after IV infusion of 8 to 14 × 107 chronic-phase CML cells, but cells from only 5 of 10 patients engrafted at mean levels of 1% or more.

The aim of our study was to establish a model of CML in non-obese diabetic/LtSz scid/scid mice (NOD/SCID) mice. This strain is profoundly immunodeficient with defective T- and B-cell function and marked impairment of macrophage, natural killer cell, and hemolytic complement activity.33 We aimed to determine a dose of CML blood cells that would reliably achieve engraftment and characterize the engrafting human cells in terms of lineage and bcr-abl expression. We used exclusively PB because it is relatively easily collected in large amounts at diagnosis and has been shown to engraft SCID mice at equivalent rates to BM.32 Our previous studies have identified CML blood as an abundant source of normal preprogenitors.11 Ex vivo manipulation of CML blood is a promising approach for autologous transplantation, so a detailed assessment of the engraftment potential of CML blood is a necessary precedent to studies of purging strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Material

PB was collected by apheresis from patients with recently diagnosed CML as approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Royal Adelaide Hospital (Adelaide, South Australia). Cells were diluted in Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS; GIBCO BRL, Victoria, Australia). Light-density mononuclear cells were collected after centrifugation at 400g over a Lymphoprep density gradient (1.077g/dL; Nycomed Pharma AS, Oslo, Norway) and washed twice in HBSS. Cells were cryopreserved in 10% dimethylsulphoxide, 20% fetal calf serum (Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, Victoria, Australia) by controlled rate freezing. Before infusion, cells were rapidly thawed at 37°C and 4% sodium citrate was added. Cells were washed twice in Ca+2 Mg+2 free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 4% sodium citrate, and 1% human serum albumin (CSL) and kept at room temperature before infusion.

The phenotype of patient samples was assessed by standard technique34 using directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies to CD34, CD33, CD3, and CD19 (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, Ca). Cells stained with the appropriate directly conjugated isotype antibodies were used as controls.

Selection of CD34+ Cells

Cryopreserved cells.

Cells were thawed, washed, and resuspended at 1 to 2 × 107/mL in isolation buffer (Ca+2Mg+2 free PBS, 0.6% sodium citrate, 2% human serum albumin) and CD34+ cells were selected as described previously.10 Briefly, cells were rosetted with Dynabeads M-450 CD34 (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) at 4°C for 40 minutes with gentle rotation. Rosetted cells were selected by placing the tube on a Dynal MPC magnet and pipetting the nonrosetted cells. The rosetted cells were resuspended in isolation buffer and the separation procedure was repeated 5 times. The nonrosetted cells (CD34−) were pooled for use in control mice. Beads were detached from positively selected cells by incubating with anti-Fab antiserum (DETACHaBEAD; Dynal) at 37°C for 90 minutes. Released cells (CD34+) were aspirated after placing the tube on the magnet. Released cells and nonrosetted cells were counted and purity determined by flow cytometry.

Fresh cells.

Cells collected at diagnosis in 2 patients had CD34+ cells selected with the Isolex 50 magnetic cell separation system (Baxter Healthcare Corp, Irvine, CA) as previously described.35Briefly, 4 × 109 cells were incubated with 2 mg 9C5 anti-CD34 antibody (Dynal) at room temperature (RT) for 30 minutes with gentle rotation. Cells were rosetted with Dynabeads and retained in the chamber attached to the magnetic column and nonrosetted cells drained. Rosetted cells were washed in buffer and the separation procedure was repeated 3 times. Rosetted cells were released by incubating with 100pKat chymopapain (ChymoCell-R; Baxter) at RT for 15 minutes. Isolated cells had CD34 levels evaluated and were cryopreserved as described above.

NOD/SCID Mice

A breeding colony of NOD/SCID mice was established at the University of Adelaide from animals originally obtained from Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Melbourne. Experiments were performed as approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Adelaide. Mice were kept in microisolator cages in a laminar flow room in specific pathogen-free conditions. Before cell infusion, mice 6 to 8 weeks old were irradiated with a total dose of 300 cGy, delivered at 600 cGy per minute, by a CsCl blood cell irradiator. Higher doses of irradiation (350 and 400 cGy) were attempted but resulted in high mortality between days 10 and 18. Cells were infused, in a volume of 500 to 1,000 μL, into a tail vein 24 hours after irradiation, and mice were maintained on sterilized food and acidified water supplemented with 60 mg trimethoprim and 300 mg sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim; Roche Products, New South Wales, Australia) per 100 mL water 3 days per week. Some mice received IP injections of recombinant human hematopoietic growth factors (HGF), either stem cell factor (SCF; Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF; Amgen), or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; Sandoz, New South Wales, Australia), at 5 μg 3 times per week. Mice were closely observed and killed if they developed lethargy or weight loss. Mice were killed between days 28 and 50 by cervical dislocation. The BM from both femurs and tibias was taken and the spleen was homogenized.

Analysis of Engraftment

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis for human cell engraftment.

Human chromosome 8 was detected using a probe for the α satellite region at the D8Z2 locus (ATCC clone pJM128; American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD), which does not cross-react with mouse chromosomes. The probe was biotin-labeled by standard nick translation with biotin-14-dATP (BioNick Labelling System; GIBCO BRL) to 200 to 500 bp. BM and spleen cells from transplanted mice were washed twice in PBS and deposited on poly-l-lysine–treated glass slides (Sigma, St Louis, MO). One drop of 75 mmol/L KCL was added to cells that were then fixed with cold 75% methanol 25% acetic acid and allowed to air dry.36 The in situ hybridization technique used was a modified version of the methods described by Tkachuk et al37 and Lichter et al.38 Cells were treated with RNAse A (Boehringer Mannheim, New South Wales, Australia), at 10 μg in 100 μL 2× SSC for 1 hour at 37°C, followed by 2 washes with 2× SSC and serial dehydration with cold 70%, 90%, and 100% ethanol. Cells were denatured in 70% formamide, pH 7, at 70°C for 4 minutes and then immediately dehydrated again with 70%, 90%, and 100% ethanol. The hybridization mixture consisted of 5 ng probe DNA in 10% dextran sulphate, 2× SSC, 50% formamide, and 0.1% polyoxyethylenesorbitan monolaurate (Tween 20; Sigma), which was denatured at 96°C for 4 minutes followed by immediate cooling, and then added to individual slides preheated to 37°C and incubated overnight in a humid atmosphere (Omni-Slide; Integrated Sciences, New South Wales, Australia). After hybridization, slides were washed twice for 10 minutes each in 50% formamide at 42°C and then twice in 2× SSC and 1× SSC at RT. Hybridized probe was detected using avidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Vector, Burlingame, CA), nuclei counterstained with propidium iodide (PI), and slides mounted in DABCO (1,4 diazabicyclo[2.2.2.]octane; Sigma). Cells were examined at 1,000× magnification under oil immersion using an Olympus BH2 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with fluorescence attachment. A minimum of 300 cells were examined. Engraftment was determined by calculating the number of cells with 2 fluorescent signals as a percentage of the total number of PI-stained cells.

FISH analysis for leukemic engraftment.

The hybridization protocol is similar to that described for D8Z2. Before RNAse treatment slides were treated with 0.01 pg/mL proteinase K (Merck, Victoria, Australia) for 30 minutes at 37°C and then washed with 2× SSC before the addition of RNAse A. LSI bcr SpectrumGreen/abl SpectrumOrange dual-color DNA probe mixture (Vysis, Downers Grove, IL) was prepared according to manufacturer's instructions. The denaturation, hybridization, and posthybridization washes were performed as described for D8Z2. Dual-labeled cells were examined using a dual band-pass filter for both FITC and Texas red. Where possible, 300 cells were examined. Scoring criteria for normal and leukemic cells were as recommended by the manufacturer.

Immunophenotype analysis.

Mouse BM and spleen suspensions of transplanted mice were assessed for presence of human cells by immunolabeling with conjugated anti-CD45 (Becton Dickinson) with comparison to an anti-IgG control. Red blood cells were lysed before immunolabeling in 10× vol 0.83% ammonium chloride at 37°C for 10 minutes. Differentiation of engrafted cells was determined by dual-color labeling with anti-CD45 FITC and anti-CD34, 33, 3, and 19 phycoerythrin (Becton Dickinson), respectively. Expression of these antigens was compared with control cells labeled with anti-IgG controls. We gated cells to include both lymphoid and myeloid fractions.39

Colony-forming unit–granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM) assay.

Triplicate 1-mL cultures with 5 × 105 BM cells were established in 35-mm plates in 0.9% methylcellulose (Methocel; Dow Chemical Co, Midland, MI) in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (GIBCO BRL) supplemented with 30% fetal calf serum and 3 mmol/L L-glutamine. Cultures were stimulated by 10 ng each of recombinant human interleukin-3 (Sandoz), GM-CSF, and SCF, a combination that does not stimulate murine progenitors. After 14 days of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, CFU-GM were scored as aggregates of greater than 50 cells.

Morphological assessment.

Cytocentrifuge slides were prepared from BM and spleen, air-dried, and then stained with Jenner-Giemsa (BDH Ltd, Poole, UK).

Conventional 4-μm histologic sections of spleen and decalcified tibia were cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded material and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± 1 standard error of the mean (SEM) percentages, unless otherwise stated. Analysis of engraftment used regression analysis and analysis of variance.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Cryopreserved PB from 15 patients with newly diagnosed chronic-phase CML was infused into 163 NOD/SCID mice in different experiments. The white blood cell count (WCC) at presentation ranged between 39 and 376 (median, 133) × 109/L (Table 1). Twelve patients had exclusively 100% Ph+ metaphases in the BM at diagnosis, with 1 patient having 82% Ph+ metaphases, 1 patient having a complex translocation, and 1 patient having an additional minor abnormality (Table 1). Analysis of thawed material by FISH showed 37% to 51% (median, 48%) bcr-abl+ cells in 5 samples analyzed. The immunophenotype of thawed cells was quite variable. CD34 levels ranged between 3% and 31% (median, 18%). Myeloid cells, as assessed by CD33 expression, ranged between 7% and 60% (median, 30%), and T lymphocytes, as assessed by CD3, ranged between 12% and 49% (median, 27%). The level of B cells was low and less than 10% in all cases. Trypan blue estimation of cell viability before infusion into mice showed 66% to 88% viability.

Presenting Features of Patients Whose Cells Were Cryopreserved at Diagnosis

| Patient . | WCC* (×109/L) . | Ph+ Metaphases* . | FISH† BCR-ABL+ (%) . | Immunophenotype† . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD34 . | CD33 . | CD3 . | CD19 . | ||||

| 01 | 222 | 100% | ND | 24 | 60 | 17 | 3 |

| 02 | 142 | 100% | 48 | 22 | 28 | 12 | 3 |

| 03 | 112 | 100% | 50 | 7 | 30 | 49 | 2 |

| 04 | 133 | 100% | ND | 18 | 27 | 48 | 4 |

| 05 | 71 | 100% | ND | 9 | ND | ND | ND |

| 06 | 370 | 100%‡ | 37 | 5 | 54 | 26 | 9 |

| 07 | 192 | 100% | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 08 | 284 | 100% | 51 | 21 | 37 | 27 | 4 |

| 09 | 214 | 100% | ND | 3 | 26 | 49 | 3 |

| 10 | 98 | 100% | ND | 3 | ND | ND | ND |

| 11 | 70 | 82% | ND | 20 | ND | ND | ND |

| 12 | 109 | 100%§ | ND | 25 | 50 | 15 | 1 |

| 13 | 35 | 100% | 43 | 31 | 52 | 18 | 2 |

| 14 | 376 | 100% | ND | 20 | ND | ND | ND |

| 15 | 39 | 100% | ND | 3 | 7 | 49 | 1 |

| Patient . | WCC* (×109/L) . | Ph+ Metaphases* . | FISH† BCR-ABL+ (%) . | Immunophenotype† . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD34 . | CD33 . | CD3 . | CD19 . | ||||

| 01 | 222 | 100% | ND | 24 | 60 | 17 | 3 |

| 02 | 142 | 100% | 48 | 22 | 28 | 12 | 3 |

| 03 | 112 | 100% | 50 | 7 | 30 | 49 | 2 |

| 04 | 133 | 100% | ND | 18 | 27 | 48 | 4 |

| 05 | 71 | 100% | ND | 9 | ND | ND | ND |

| 06 | 370 | 100%‡ | 37 | 5 | 54 | 26 | 9 |

| 07 | 192 | 100% | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 08 | 284 | 100% | 51 | 21 | 37 | 27 | 4 |

| 09 | 214 | 100% | ND | 3 | 26 | 49 | 3 |

| 10 | 98 | 100% | ND | 3 | ND | ND | ND |

| 11 | 70 | 82% | ND | 20 | ND | ND | ND |

| 12 | 109 | 100%§ | ND | 25 | 50 | 15 | 1 |

| 13 | 35 | 100% | 43 | 31 | 52 | 18 | 2 |

| 14 | 376 | 100% | ND | 20 | ND | ND | ND |

| 15 | 39 | 100% | ND | 3 | 7 | 49 | 1 |

After thawing, FISH and immunophenotype were performed before infusion into mice.

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

At diagnosis.

Before infusion into mice on thawed PB monuclear cells.

t(9;22)[73%]t(9;22), del(20p)[27%].

t(3;9;22)[100%].

Sensitivity of FISH to Assess Engraftment

The use of human-specific probes to assess engraftment of human cells into murine hosts allows direct visualization of human cells with relatively simple enumeration. Only 1,000 cells are required, which is much lower than is required for flow cytometry. All viable, nucleated cells are seen and counted. We assessed the accuracy and sensitivity of this technique by a mixing experiment in which human cells were mixed with murine cells in defined proportions. Two blinded observers analyzed 300 cells from each dilution. The results are shown in Table 2. It can be seen that, at low levels of human cells, the concordance rate between observers and the actual level of human cells is high; therefore, the method is suitable for analyzing engraftment to the 1% level. This dilution experiment was repeated for CD45 analysis and shows similar sensitivity at low levels of engraftment (Table 2).

Assessment of FISH and CD45 for Analysis of Engraftment of Human Cells in NOD/SCID Mice

| % Human Cells Diluted in Mouse Cells . | FISH (D8Z2) (%)* . | CD45 (%) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scorer 1 . | Scorer 2 . | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 3.3 |

| 3 | 2.7 | 3 | 1.8 |

| 5 | 5 | 4 | 4.6 |

| 10 | 7.3 | 4 | 6.9 |

| 25 | 29 | 27 | 22.3 |

| 50 | 36 | 46 | 49.9 |

| 75 | 70.3 | 72 | 69.4 |

| 100 | 98 | 99 | 88.3 |

| % Human Cells Diluted in Mouse Cells . | FISH (D8Z2) (%)* . | CD45 (%) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scorer 1 . | Scorer 2 . | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 3.3 |

| 3 | 2.7 | 3 | 1.8 |

| 5 | 5 | 4 | 4.6 |

| 10 | 7.3 | 4 | 6.9 |

| 25 | 29 | 27 | 22.3 |

| 50 | 36 | 46 | 49.9 |

| 75 | 70.3 | 72 | 69.4 |

| 100 | 98 | 99 | 88.3 |

A known dilution of human cells into mouse cells was tested.

Three hundred cells counted in a blinded fashion.

Engraftment Studies With Unselected CML PB Cells

In separate experiments, 115 mice were infused with 1.1 to 7.6 × 107 cells from 13 patients (all patients in Table 1 except patients 01 and 07). Some mice received HGF. Eighteen mice (16%) became ill between days 10 and 18, with lethargy, ruffled fur, and wasting, suggesting radiation toxicity, and were killed. An additional 6 mice (5%) became ill between days 42 and 50, with features of lethargy and wasting, and were killed. Analysis of these mice did not show evidence of overwhelming leukemia, and they may have succumbed to graft-versus-host disease-type illness, as has previously been described in NOD/SCID mice occurring at this timepoint.40

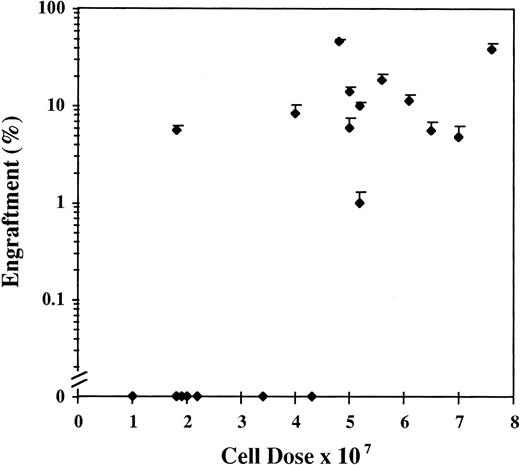

BM engraftment.

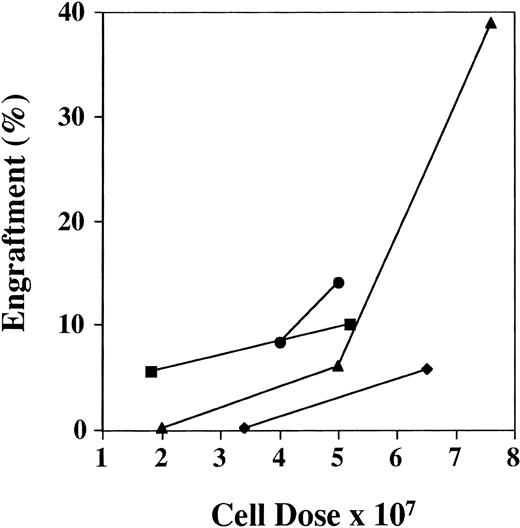

Human cells ≥1% were detected by FISH in 69 of the 91 mice (76%) analyzed between days 28 and 51, with a range of engraftment of 1% to 87% (Fig1A). The median level of engraftment in these 69 mice was 9%. BM engraftment ≥10% was seen in 32 of the 69 engrafted mice (46%). Engraftment was correlated with total cell dose (r = .52). Eighteen mice received less than 4 × 107 cells, 8 mice showed no engraftment, and 10 mice had a median engraftment of 3% (range, 1% to 7%). In the 73 mice receiving ≥4 × 107 cells, 61 mice engrafted with a level of 20% ± 3% (median, 10%; Fig 2). The effect of cell dose is further shown in Fig 3. Different cohorts of mice were infused with different cell doses from 4 patients. In each case, higher engraftment was seen at the higher cell dose (r = .71). Analysis of predictors of engraftment showed that the total cell dose, CD34+ cell dose, and the donor (P < .01) were independent predictors.

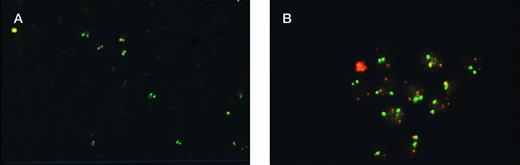

Analysis of engraftment of human cells in NOD/SCID mice by FISH. (A) Human cells detected by D8Z2 probe show two bright green fluorescent signals in contrast to murine cells with no signal (original magnification × 200). (B) Differential engraftment of normal and leukemic CML cells in NOD/SCID mice detected by dual probes for bcr and abl. Normal cells show two red ablsignals and two green bcr signals. Leukemic cells show a single red and green signal representing normal abl and bcrgenes and the yellow signal representing fusion of abl andbcr genes (original magnification × 1,000).

Analysis of engraftment of human cells in NOD/SCID mice by FISH. (A) Human cells detected by D8Z2 probe show two bright green fluorescent signals in contrast to murine cells with no signal (original magnification × 200). (B) Differential engraftment of normal and leukemic CML cells in NOD/SCID mice detected by dual probes for bcr and abl. Normal cells show two red ablsignals and two green bcr signals. Leukemic cells show a single red and green signal representing normal abl and bcrgenes and the yellow signal representing fusion of abl andbcr genes (original magnification × 1,000).

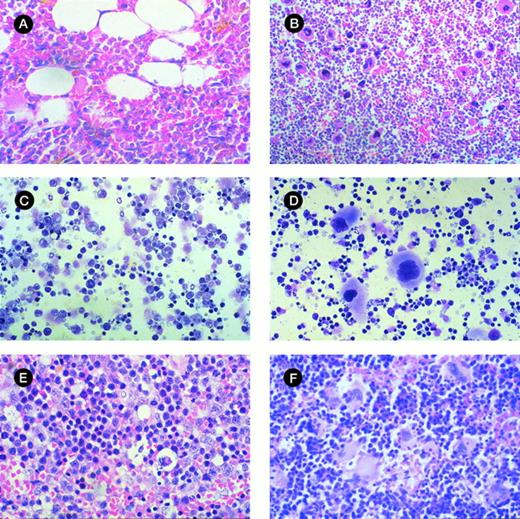

Morphologic analysis of murine BM and spleen engrafted with CML cells. (A) Histologic section of tibia of NOD/SCID mouse irradiated but not infused with human cells at day 42 (original magnification × 400). (B) Histologic section of tibia of mouse with 28% human cells detectable at day 42. Hypercellular marrow with proliferation of megakaryocytes and eosinophils are shown (original magnification × 400). (C) Histologic section of spleen from control mouse showing monomorphic lymphoid population (original magnification × 400). (D) Histologic section of spleen of mouse with 33% human cells detectable at day 42. Infiltration with megakaryocytes is shown. (E) Cytospin preparation of spleen from control mouse (original magnification × 400). (F) Cytospin preparation of spleen of mouse with 56% human cells detected at day 42 showing prominent magakaryocytes (original magnification × 400).

Morphologic analysis of murine BM and spleen engrafted with CML cells. (A) Histologic section of tibia of NOD/SCID mouse irradiated but not infused with human cells at day 42 (original magnification × 400). (B) Histologic section of tibia of mouse with 28% human cells detectable at day 42. Hypercellular marrow with proliferation of megakaryocytes and eosinophils are shown (original magnification × 400). (C) Histologic section of spleen from control mouse showing monomorphic lymphoid population (original magnification × 400). (D) Histologic section of spleen of mouse with 33% human cells detectable at day 42. Infiltration with megakaryocytes is shown. (E) Cytospin preparation of spleen from control mouse (original magnification × 400). (F) Cytospin preparation of spleen of mouse with 56% human cells detected at day 42 showing prominent magakaryocytes (original magnification × 400).

Results of engraftment by FISH of 19 cohorts of 2 or 3 mice receiving different doses of chronic-phase CML cells collected from patients at diagnosis. Results are the mean ± SEM engraftment for each cohort of mice.

Results of engraftment by FISH of 19 cohorts of 2 or 3 mice receiving different doses of chronic-phase CML cells collected from patients at diagnosis. Results are the mean ± SEM engraftment for each cohort of mice.

Effect of cell dose on engraftment. The graph shows the increased engraftment in cohorts of mice receiving different cell doses from the same patient sample. Results are the mean BM engraftment for each cohort. Patients no. (▪) 2, (⧫) 3, (•) 4, and (▴) 8.

Effect of cell dose on engraftment. The graph shows the increased engraftment in cohorts of mice receiving different cell doses from the same patient sample. Results are the mean BM engraftment for each cohort. Patients no. (▪) 2, (⧫) 3, (•) 4, and (▴) 8.

Engraftment was confirmed by analysis of human specific CD45, a pan leukocyte marker. All mice that had engraftment ≥1% by FISH had CD45+ cells detected. The level of engraftment by CD45 was slightly lower compared with FISH. This difference may have been due to the exclusion of some human cells by the gate applied or the failure to lyse all mouse red blood cells, resulting in a dilution of human cells.

The ability of engrafted cells to produce CFU-GM was assessed in 17 mice with engraftment levels of 1% to 87%. CFU-GM were detected in 15 of 17 cases, with a level of 35 ± 7 (range, 1 to 94) colonies per 105 BM cells plated. The total number of human CFU-GM present in 2 femurs and 2 tibias was 7 to 2,690 (mean, 697). Morphologic assessment showed hypercellularity of BM with increased numbers of megakaryocytes and eosinophilia in highly engrafted animals, but there was no fibrosis (Fig 4A and B). Assessment of the peripheral blood WCC in 6 mice showed a normal WCC.

Splenic engraftment.

In 64 mice that had BM engraftment, 42 (66%) had detectable human cells in the spleen, with engraftment of 16% ± 3% (range, 1% to 92%). The donor was a predictor of spleen engraftment (P < .01); mice infused with cells from patients 02, 03, and 04 had higher levels of splenic engraftment, whereas mice infused with cells from patients 06, 11, and 12 had low splenic engraftment despite quite high BM engraftment. There were no statistically significant differences between these groups in terms of WCC at diagnosis, the percentage of Ph+ cells by karyotype, or the percentage of CD3 cells in the blood. In 16 mice the level of splenic engraftment exceeded the level of BM engraftment. No mice had isolated splenic engraftment. Mice with high splenic engraftment had moderate splenomegaly. Histologic examination of the spleen showed infiltration by megakaryocytes in most engrafted mice (Fig 4C through F).

Leukemic engraftment.

The differential engraftment of leukemic and normal human cells was assessed by FISH analysis with directly conjugated probes forbcr and abl (Fig 1B). There was no cross-reactivity of the probes with murine cells. In 25 mice with BM engraftment ≥9%, the level of bcr-abl+ cells detected was 39% ± 5% (range, 5% to 91%) of the engrafted human cells. We also analyzed 6 spleen specimens that had 29% to 87% engraftment for the presence of leukemic cells. Of the engrafted cells, a lower level ofbcr-abl+ cells was detected compared with BM (11% ± 2%; range, 4% to 17%).

Use of HGF to improve engraftment.

The role of HGF in promoting engraftment of human cells was assessed in nine experiments with 59 mice. IP injections of 5 μg of SCF, G-CSF, or GM-CSF were administered every second day, except in 4 mice that received SCF + G-CSF or SCF + GM-CSF. The use of HGF did not produce an increase in engraftment compared with control mice that received no growth factor. Mice receiving GM-CSF or SCF had levels of engraftment that were not statistically significantly different from no growth factor. Human engraftment with no growth factor was 22% ± 6% (n = 22), compared with 19% ± 5% for SCF (alone or in combination, n = 28), and 26% ± 8% for GM-CSF (n = 7). The use of G-CSF alone resulted in significantly lower levels of human engraftment −6% ± 3% (n = 8; P = .01).

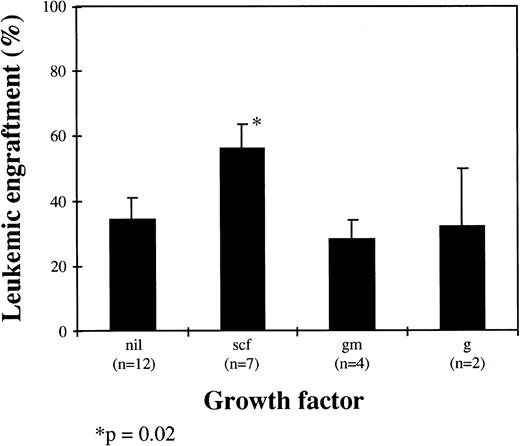

The influence of HGF on leukemic cell engraftment was also assessed, and there was a trend for mice receiving SCF alone or in combination to have higher levels of bcr-abl+ cells detected (P = .02). In mice receiving SCF (n = 7), the level of leukemic engraftment was 56% ± 8% compared with 34% ± 7% for mice receiving no HGF (n = 12), 28% ± 6% for mice receiving GM-CSF alone (n = 4), and 32% ± 18% for mice receiving G-CSF alone (n = 2; Fig 5).

Influence of HGF on leukemic engraftment. Results are the mean ± SEM of bcr-abl+ cells by FISH as a proportion of total human cells (scf, stem cell factor; gm, GM-CSF; g, G-CSF; nil, no growth factor).

Influence of HGF on leukemic engraftment. Results are the mean ± SEM of bcr-abl+ cells by FISH as a proportion of total human cells (scf, stem cell factor; gm, GM-CSF; g, G-CSF; nil, no growth factor).

Phenotype of engrafted cells.

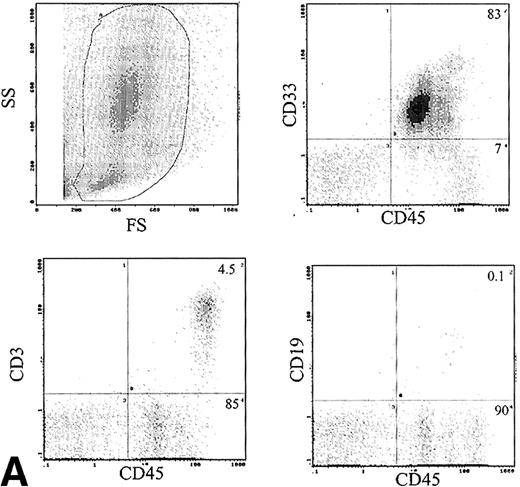

The immunophenotype, as assessed by dual-color immunofluorescence, of the engrafted human cells in the BM is shown in Table 3. The engrafted cells were predominantly myeloid in origin, as shown by the expression of CD33 (Fig 6A). Primitive cells, defined by expression of CD34, were detected in 10 of 24 samples analyzed at levels of 1% to 14% of engrafted cells. CD19 cells were rare in the BM, with 1.9% ± 1.2% of human cells being positive. Analysis of CD3 showed predominant expression in the BM of 2 patients, with mean levels of 54% and 58%. The samples infused into these mice contained 12% and 49% CD3 cells, respectively. These CD3+ cells consisted of distinct populations of CD4+ and CD8+ cells (data not shown). Analysis of sorted CD3+ cells by FISH for bcr-abl showed only 2% leukemic cells, which is within the background level of bcr-abldetection, suggesting that virtually all the CD3 cells were Ph−. Expression of CD56 was assessed in the BM of 6 mice and 6% ± 3% of human cells expressed this antigen.

Phenotype of Engrafted Cells in Mouse BM and Spleen

| Patient . | Phenotype of Engrafted Cells in BM . | Phenotype of Engrafted Cells in Spleen . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD34 . | CD33 . | CD3 . | CD19 . | CD34 . | CD33 . | CD3 . | CD19 . | |

| 02 | 0 | 17 ± 7.3 | 54.2 ± 12.1 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 0 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 81.8 ± 8.7 | 1.8 ± 0.5 |

| 03 | 0 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 58 ± 10.5 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0 | 1.5 ± 1.5 | 73.7 ± 17.3 | 6 ± 4 |

| 04 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 49.7 ± 18.2 | 18.3 ± 18.3 | ND | 0 | 0 | 94 | 10 |

| 06 | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 75.3 ± 6.1 | 2 ± 1.5 | 7.3 ± 7.3 | 0 | 27.7 ± 18.9 | 50 ± 11 | 10.7 ± 6.3 |

| 08 | 5.3 ± 2.8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 11 | 8.8 ± 2.6 | 70.8 ± 11.7 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 12 | 0 | 51.3 ± 14.3 | 2.7 ± 2.7 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Mean ± SEM | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 42.8 ± 7.2 | 30.2 ± 7.7 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 0 | 9.3 ± 6.3 | 72.8 ± 7.0 | 6.1 ± 2.2 |

| Patient . | Phenotype of Engrafted Cells in BM . | Phenotype of Engrafted Cells in Spleen . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD34 . | CD33 . | CD3 . | CD19 . | CD34 . | CD33 . | CD3 . | CD19 . | |

| 02 | 0 | 17 ± 7.3 | 54.2 ± 12.1 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 0 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 81.8 ± 8.7 | 1.8 ± 0.5 |

| 03 | 0 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 58 ± 10.5 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0 | 1.5 ± 1.5 | 73.7 ± 17.3 | 6 ± 4 |

| 04 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 49.7 ± 18.2 | 18.3 ± 18.3 | ND | 0 | 0 | 94 | 10 |

| 06 | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 75.3 ± 6.1 | 2 ± 1.5 | 7.3 ± 7.3 | 0 | 27.7 ± 18.9 | 50 ± 11 | 10.7 ± 6.3 |

| 08 | 5.3 ± 2.8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 11 | 8.8 ± 2.6 | 70.8 ± 11.7 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 12 | 0 | 51.3 ± 14.3 | 2.7 ± 2.7 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Mean ± SEM | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 42.8 ± 7.2 | 30.2 ± 7.7 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 0 | 9.3 ± 6.3 | 72.8 ± 7.0 | 6.1 ± 2.2 |

Results are the percentage of CD45+ cells expressing the denoted antigen (mean ± SEM).

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

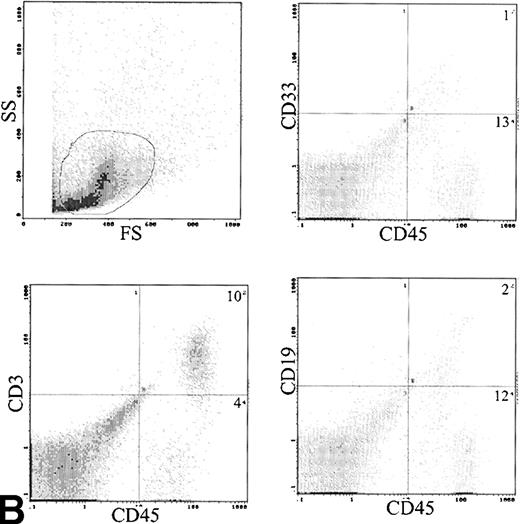

(A) Immunophenotype of BM specimen at day 42 showing high engraftment of predominantly myeloid cells with lower levels of CD3 and CD19 cells. (B) Immunophenotype of spleen cells from the same mouse showing virtually exclusive T-cell engraftment.

(A) Immunophenotype of BM specimen at day 42 showing high engraftment of predominantly myeloid cells with lower levels of CD3 and CD19 cells. (B) Immunophenotype of spleen cells from the same mouse showing virtually exclusive T-cell engraftment.

Analysis of cell surface phenotype of human cells in the spleen showed a different picture (Fig 6B). No CD34 cells were detected and CD33 cells were only 9.3% ± 6.3% of engrafted cells. The predominant cell type expressed CD3 with 72.8% ± 7% positive (Table 3). These CD3 cells also contained both CD4 and CD8 cells and were predominantly CD45RO+. The CD3 content of the infused cells was 6.2 to 32 × 106 (median, 12 × 106), and the total number of T cells recovered from the spleens was 0.1 to 46 × 106 (median, 1.0 × 106). The B lymphocytes were also more frequent in the spleen, with 6.1% ± 2.2% cells detected.

To assess the kinetics of engraftment, 6 mice were infused with 7.4 × 107 cells and 2 of these mice were killed at each time-point; days 14, 28, and 42. The mean BM engraftment was 38%, 13%, and 30% at each of these timepoints, respectively. At day 28, a mean of 62% and 8% of engrafted cells expressed CD33 and CD34, respectively. By day 42, only 7.5% and 0.5% of engrafted cells expressed these antigens. This was associated with an increase in CD3 cells from a mean of 4% at day 28 to 56% at day 42. No engraftment of the spleen was noted at day 14 or 28, but 33% human cells were detected at day 42, with 94% of these being CD3+.

Engraftment Studies With Selected CML CD34 Cells

CD34+ cells were selected from 4 patient samples (05, 08, 10, and 11) using Dynal beads on thawed material. Two patient samples (01 and 07) had large scale selection of CD34+ cells by an Isolex column. One of these samples (01) had CD34+ cells selected at diagnosis on leukapheresis product that were then cryopreserved before use. The mean purity of recovered cells was 93% (range, 88% to 98%). Cell doses of between 1 × 104and 1 × 107 were infused from these 6 patient samples into 36 mice (Table 4). Mice were killed at day 28 (13) or day 42 (25). There was a correlation between the number of CD34+ cells infused and the level of engraftment (r = .47). Engraftment was seen in 2 mice at day 28 with levels of 2% and 63%, respectively. At day 42, 7 mice engrafted between 0.7% and 54%. Eight of 10 mice receiving ≥6 × 106cells showed engraftment, but none of the 26 mice receiving lower cell numbers did. Only 2 samples had engraftment in the spleen at levels of 1% and 4%. The 2 mice that had the highest engraftment levels (54% and 63%) received CD34 cells selected from fresh leukapheresis material.

BM Engraftment of Selected CD34+ and CD34− Cells

| Patient . | CD34+ Selected Cells; Dose Administered . | Purity (%) . | % BM Engraftment (#) . | CD34− Cells; Dose Administered . | % BM Engraftment (#) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 1 × 107 | 94 | 63 | ND | ND |

| 2 | |||||

| 54 | |||||

| 05 | 5 × 104 | 89 | 0 (5) | 5 × 107 | 0 (3) |

| 5 × 105 | 89 | 0 (5) | |||

| 7 × 106 | 89 | 7 | |||

| 07 | 2 × 105 | 98 | 0 (2) | 1.2 × 107 | 0 (1) |

| 5 × 106 | 98 | 0 (7) | 3 × 107 | 0 (3) | |

| 1 × 107 | 98 | 0 | |||

| 0.7 | |||||

| 3 | |||||

| 4 | |||||

| 08 | 1 × 107 | 94 | 0 | 5 × 107 | 0 (2) |

| 10 | 1 × 104 | 88 | 0 (3) | 5 × 107 | 0 (2) |

| 1 × 105 | 88 | 0 (4) | |||

| 11 | 1 × 107 | 93 | 33 | 5 × 107 | 0 |

| Patient . | CD34+ Selected Cells; Dose Administered . | Purity (%) . | % BM Engraftment (#) . | CD34− Cells; Dose Administered . | % BM Engraftment (#) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 1 × 107 | 94 | 63 | ND | ND |

| 2 | |||||

| 54 | |||||

| 05 | 5 × 104 | 89 | 0 (5) | 5 × 107 | 0 (3) |

| 5 × 105 | 89 | 0 (5) | |||

| 7 × 106 | 89 | 7 | |||

| 07 | 2 × 105 | 98 | 0 (2) | 1.2 × 107 | 0 (1) |

| 5 × 106 | 98 | 0 (7) | 3 × 107 | 0 (3) | |

| 1 × 107 | 98 | 0 | |||

| 0.7 | |||||

| 3 | |||||

| 4 | |||||

| 08 | 1 × 107 | 94 | 0 | 5 × 107 | 0 (2) |

| 10 | 1 × 104 | 88 | 0 (3) | 5 × 107 | 0 (2) |

| 1 × 105 | 88 | 0 (4) | |||

| 11 | 1 × 107 | 93 | 33 | 5 × 107 | 0 |

Abbreviations: #, number of mice tested (results with no number are from single mice); ND, not determined.

The engrafted cells from 3 mice were phenotyped and showed myeloid and B-lymphoid cells in the BM. The mean level of CD34 expression was 10%. The mean level of CD33 expression was 80% and of CD19 was 10.7%. CD3 cells were not detected (Table 5).

Characterization of Engraftment of Selected CD34+ Blood Cells in BM of NOD/SCID Mice

| Patient . | Engraftment (%) . | BCR-ABL+ Cells by FISH (%)* . | Phenotype . | CFU-GM/ 105 Cells . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD34 . | CD33 . | CD3 . | CD19 . | ||||

| 01 | 63 | 64 | 11 | 88 | 0 | 7 | 108 |

| 01 | 54 | 35 | 15 | 71 | 0 | 20 | 104 |

| 11 | 33 | 23 | 4 | 82 | 0 | 5 | ND |

| Patient . | Engraftment (%) . | BCR-ABL+ Cells by FISH (%)* . | Phenotype . | CFU-GM/ 105 Cells . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD34 . | CD33 . | CD3 . | CD19 . | ||||

| 01 | 63 | 64 | 11 | 88 | 0 | 7 | 108 |

| 01 | 54 | 35 | 15 | 71 | 0 | 20 | 104 |

| 11 | 33 | 23 | 4 | 82 | 0 | 5 | ND |

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

Refers to percentage of human cells that are BCR-ABL+.

Assessment of leukemic cell engraftment by FISH was performed on the 3 samples with the highest engraftment. The number ofbcr-abl+ cells was variable, being 23%, 35%, and 64% (Table 5).

To confirm that the engrafting cell in CML is CD34+, parallel experiments with the infusion of CD34− cells were performed. Cells were infused from 5 patients (05, 07, 08, 10, and 11) at doses ranging between 1.2 and 5 × 107 cells into 12 mice. No engraftment by either FISH or CD45 analysis was seen in any of the mice infused (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

We have established a model of CML in NOD/SCID mice by infusing large numbers of cryopreserved CP CML PB into sublethally irradiated mice. The major determining predictor of engraftment was the cell dose infused with 84% of mice receiving ≥4 × 107 cells showing evidence of human cells 28 to 42 days postinfusion. Of these, 46% of mice had greater than 10% human cells detected in their BM. SCF, G-CSF, or GM-CSF alone or in combination failed to improve overall engraftment rates. In addition, we detected human cells in the spleen of 60% of mice that had BM engraftment. Previous studies of murine models of CML have also shown that the cell dose infused is critical for engraftment and that HGF do not improve engraftment levels. The study of Sirard et al32 infused 8 to 14 × 107 fresh PB or BM mononuclear cells from newly diagnosed CML patients into SCID mice and showed the majority of mice achieving 0.1% to 10% engraftment. Mice receiving 2 to 6 × 107 cells achieved negligible engraftment.32Our study shows higher engraftment in the NOD/SCID mouse using lower cell doses. This may be the result of using cryopreserved material because of the selective loss of the more mature, nonengraftable cells during cryopreservation. However, the more immunosuppressed NOD/SCID mouse has been shown to improve engraftment of human cord blood compared with SCID mice,41 and this may account for the lower doses required. We also show morphologic evidence of a CML-like disease in the BM and spleen of engrafted mice but no leukocytosis, suggesting that our model recapitulates some of the features of chronic-phase CML.

The ability to assess engraftment of leukemic and normal cells is critical if the application of cell selection or purging techniques as therapeutic modalities in CML are to be tested in an animal model. We have used FISH to detect bcr-abl+ cells in engrafted mice as a measure of leukemic engraftment. This allows direct visualization and enumeration of cells and avoids the reliance on proliferating cells necessary for cytogenetic analysis. Analysis of the CML cells before infusion from 5 patients showed that 37% to 51% of cells were bcr-abl+ by FISH, indicating that the innoculum has equivalent numbers of leukemic and nonleukemic cells. The high number of nonleukemic cells may be accounted for by the high levels of T cells in some samples. We analyzed 25 specimens posttransplantation by FISH for bcr-abl and of the human cells a mean level of 39% were leukemic, with a range of 5% to 94%. Thus, there is a wide range in the level of leukemic engraftment in these mice, but the majority of cases show preferential engraftment of normal cells.

The role of HGF is relevant, because they are used clinically to mobilize stem cells or posttransplantation to increase the speed of engraftment and may modulate normal or leukemic engraftment. We found that SCF has a role in promoting the engraftment and proliferation of leukemic cells in vivo, which is consistent with in vitro findings,42 but G-CSF and GM-CSF did not promote leukemic engraftment.

The immunophenotype of engrafted cells shows differential engraftment of myeloid and lymphoid cells between the BM and spleen. Myeloid cells, defined by expression of CD33, were confined to the BM. This is not dependent on exogenous myeloid growth promoting factors, because it was seen in mice that received no growth factor as well. The engraftment of primitive cells was confirmed in some mice by detection of CD34. The levels were low but in keeping with the frequency of these cells in CML BM and also consistent with the data of Sirard et al.32 We were able to show B-cell lymphoid development in the spleen of some mice, but levels of B cells within BM were negligible.

The finding of almost exclusive T-cell involvement of engrafted murine spleen and high levels of T cells in the BM of some mice is intriguing. The early study of Sawyers et al29 showed recovery of predominantly CD3+ cells from the peritoneal cavity of SCID mice receiving 1 to 5 × 107 CP CML cells IP. The study of Sirard et al32 shows expression of CD13 and CD19 of engrafted CML BM cells. Infusion of human PB lymphocytes (PBL) can engraft both SCID43 and NOD/SCID44 mice, but only after IP infusion of cells. This results in engraftment of predominantly T cells, with the spleen being the primary site of engraftment and very few cells being detected in the BM. In contrast, infusion of adult BM into NOD/SCID mice together with exogenous cytokine results in myeloid and B-cell engraftment in BM and spleen, with no erythroid or T-cell development.45

Our results show engraftment of polyclonal T cells in the spleen and BM of some mice. These are likely to be derived from long-lived recirculating T cells present in the innoculum, but calculation of total T cells recovered from murine BM and spleen shows expansion of the cells compared with input numbers in some mice. This finding is supported by the finding of increased engraftment of T cells at day 42 compared with earlier timepoints. The studies with normal adult BM and CML BM showing minimal T-cell engraftment from cells administered IV and the finding that PBL only engraft after IP injection suggest that the route of delivery of T cells is important. In this study, we show delayed engraftment of T cells that arebcr-abl− after IV infusion of CML PB. The mechanism of this is unclear, but it is possible that T cells in CML are part of a preleukaemic Ph− clone14that has different engraftment characteristics than normal T cells. Alternatively, the failure of engraftment of the CD34− fraction, which is enriched for T cells, may indicate that CD34+ leukemic cells facilitate the engraftment of T cells in this model.

We have shown that the infusion of 7 to 10 × 106purified CML CD34+ cells engrafts immunodeficient mice. The demonstration of bcr-abl+ cells by FISH indicates the leukemic stem cell resides in the CD34 population. Experiments with CD34− cells showed no engraftment, confirming this finding. Splenic engraftment was only seen in 2 mice at low levels. There was a high level of CD34+ cells detectable in the BM 6 weeks posttransplantation and high numbers of myeloid progenitors. Furthermore, these cells differentiate into myeloid cells and B lymphocytes, but no T cells were detected. This pattern of cell differentiation is similar to studies using CD34+-enriched umbilical cord blood.46 Other studies show engraftment of purified CD34 cells from cord blood (5 × 104cells),47 AML (5 to 7 × 106),26 and juvenile CML (JCML; 2 to 3 × 105).48 Thus, in CML higher doses of CD34 cells are necessary for engraftment, although the studies in AML and JCML required HGF. We have not assessed the role of HGF in engraftment of purified CD34+ CML cells, but they may allow a lower cell dose to be administered. Functional differences in the CD34 cell in each of these examples may explain the requirements for differing cell dose to achieve engraftment. In CML it is known that the majority of primitive cells have phenotypic characteristics of proliferating cells,49 and there is evidence to suggest cycling cells do not efficiently engraft Balb/c mice,50 although this is in an unirradiated model. Also, the frequency of the pluripotent HSC as defined by the phenotypes CD34+ HLA-DR−or CD34+ CD38− is reduced in chronic-phase CML compared with normal hematopoiesis. In normal hematopoiesis, the frequency of DR− and CD38− cells is 3% to 8% and 3% to 7% of the CD34+ population, respectively.10,51 In CML, we have shown previously that these populations are rarer, comprising 1% each of the CD34+ population.11 Another possibility is the interaction of the CML CD34 cell and the murine BM stroma. For successful BM engraftment, homing of infused cells to BM stroma is critical. Homing is integrin-dependent52 and CML cells have an integrin-mediated defect in adhesion53 that may impair their homing ability. Hence, the rarity of engraftable leukemic stem cells and defective homing ability may both contribute to the high CD34+ cell requirement of CML cells in the murine model.

In summary, we have shown engraftment of mononuclear and CD34+ selected cells from the PB of CML patients into NOD/SCID mice as evidenced by detection of human cells in the BM and spleen by FISH and immunophenotype. We achieved good levels of engraftment with lower cell doses than has been reported for the SCID mouse model of CML. Our model recapitulates the characteristic features seen in the BM with megakaryocytic and myeloid overgrowth. This model is suitable for evaluating purging strategies and novel therapies in the treatment of CML.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr Robert Moore for producing the tissue sections and Dr Bill Venables for statistical advice. Dr Ken Langley (Amgen) kindly provided SCF and Dr Glen Pater (Sandoz, Australia) kindly provided GM-CSF.

Supported in part by the Anti-Cancer Foundation of the Universities of South Australia. I.D.L. is the recipient of a National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia Postgraduate Medical Research Scholarship.

Address reprint requests to Timothy P. Hughes, MD, Division of Haematology, Hanson Centre for Cancer Research, IMVS, Frome Road, Adelaide, SA, Australia.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal