Abstract

Genetic instability and cellular proliferation have been associated with aurora kinase expression in several cancer entities, including multiple myeloma. Therefore, the expression of aurora-A, -B, and -C was determined by Affymetrix DNA microarrays in 784 samples including 2 independent sets of 233 and 345 CD138-purified myeloma cells from previously untreated patients. Chromosomal aberrations were assessed by comprehensive interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization and proliferation of primary myeloma cells by propidium iodine staining. We found aurora-A and -B to be expressed at varying frequencies in primary myeloma cells of different patient cohorts, but aurora-C in testis cell samples only. Myeloma cell samples with detectable versus absent aurora-A expression show a significantly higher proliferation rate, but neither a higher absolute number of chromosomal aberrations (aneuploidy), nor of subclonal aberrations (chromosomal instability). The clinical aurora kinase inhibitor VX680 induced apoptosis in 20 of 20 myeloma cell lines and 5 of 5 primary myeloma cell samples. Presence of aurora-A expression delineates significantly inferior event-free and overall survival in 2 independent cohorts of patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy, independent from conventional prognostic factors. Using gene expression profiling, aurora kinase inhibitors as a promising therapeutic option in myeloma can be tailoredly given to patients expressing aurora-A, who in turn have an adverse prognosis.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable malignant disease of clonal plasma cells that accumulate in the bone marrow, causing clinical signs and symptoms related to the displacement of normal hematopoiesis, formation of osteolytic bone lesions, and production of monoclonal protein.1 MM cells (MMCs) at the time of diagnosis are characterized by a low proliferation rate that increases in relapse.2 Presence of proliferation correlates with adverse prognosis.3,4 At the same time, myeloma cells harbor a high median number of chromosomal aberrations,5,6 often associated with genetic instability.6 Proliferation7 and chromosomal instability8 in turn are associated with the expression of aurora kinases. In several cancer entities, aurora kinases have been implicated in tumor formation and progression.9-14

Aurora kinases represent a family of conserved mitotic regulators comprising 3 closely related members, aurora-A, -B, and -C.9 Aurora-C expression is restricted to germ cells, where it regulates spermatogenesis.15 Aurora-A associates with the centrosome and spindle microtubules and is required for centrosome separation and spindle assembly.7 Aurora-B is a member of the chromosomal passenger complex and, as such, is sequentially recruited to centromeres, spindle midzone, and midbody as mitosis progresses.16 Aurora-B is also required for chromosome biorientation, the spindle assembly checkpoint, and cytokinesis.7 Inhibition of aurora-A and -B exhibits distinct phenotypic features: loss of aurora-A activity induces a centrosome separation defect and a monopolar spindle phenotype17,18 ; inhibition of aurora-B generates polyploidy through defects in cytokinesis, which ultimately lead to a loss in cell viability.19-22 Aurora-A and -B expression has been detected by quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) in myeloma cell lines23,24 and a small series of myeloma patients.23,24 Aurora kinase inhibitors like VX680 have been shown to abrogate proliferation and induce apoptosis in human myeloma cells lines (HMCLs) and primary myeloma cells.23-25

We assessed the expression of aurora-A, -B, and -C in 784 Affymetrix gene expression profiles of malignant plasma cells from previously untreated myeloma patients compared with normal bone marrow plasma cells (BMPCs), their nonmalignant proliferating precursors (polyclonal plasmablastic cells, PPCs), and HMCLs. We found that, in our dataset, 24% of previously untreated myeloma patients expressed aurora-A. Myeloma cells expressing aurora-A kinase had a higher proliferation rate, whereas the number of chromosomal aberrations (aneuploidy) was not higher compared with myeloma cells with absent aurora-A expression. The same held true for subclonal aberrations (ie, genetic instability), which were less frequent in myeloma cell samples expressing aurora-A. Aurora-A kinase expression in turn was significantly associated with an inferior event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) in 2 independent cohorts of a total of 513 myeloma patients treated with high-dose chemotherapy (HDT) and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT).

Aurora kinase inhibitors (including VX680, tested here) are very active on HMCLs and primary myeloma cells and represent a promising weapon in the therapeutic arsenal against MM. Gene-expression profiling allows an assessment of Aurora kinase expression and thus a tailoring of treatment to patients expressing these kinases.

Methods

Patients and healthy donors

Patients presenting with previously untreated MM (n = 233) or monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS, n = 12) at the University Hospitals of Heidelberg and Montpellier and 14 healthy donors were included in the study approved by the institutional review board of the Medical Faculty of the Ruprecht-Karls-University Heidelberg, Germany, the institutional review board of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, AR, and the institutional review board of the CHU Montpellier, France, for the respective patients. Written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The first 65 patients constitute the training group (TG) and the 168 additional patients, the independent validation group (VG). Patients' diseases were diagnosed and staged, and response to treatment was assessed according to standard criteria.26-28 A total of 168 patients underwent frontline HDT with 200 mg/m2 melphalan and ASCT, according or in analogy to the GMMG-HD3 trial.29 Survival data were validated by an independent cohort of 345 patients treated within the total therapy 2 protocol.30 For clinical parameters, see Table S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Samples

For an overview, see Table S2. Bone marrow plasma cells were purified using CD138 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and purity was assessed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). Aliquots of unpurified whole bone marrow (WBM) from patients (n = 57) and healthy donors (n = 7) were obtained after NH4 lysis as published.31 Alternate aliquots were subjected to FACS-sorting (FACSAria; Becton Dickinson) in CD3+, CD14+, CD15+, and CD34+ cells. Peripheral CD27+ memory B-cells (MBCs) were generated as previously described.32 Cell samples from testis (n = 5) were obtained from healthy donors.

The HMCLs XG-1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -6, -7, -10, -11, -12, -13, -14, -16, -19, and -20 were generated at INSERM U847 as previously described.33-35 HG-1 was generated in the Multiple Myeloma Research Laboratory Heidelberg. U266, RPMI-8226, LP-1, OPM-2, SKMM-2, AMO, JJN-3, KMS-12-BM, L363, NCI, MOLP-8 (Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, Braunschweig, Germany) were cultured as recommended. PPCs (n = 12),36 osteoclasts (OCs; n = 5),32 and mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs, n = 19)37 were generated and analyzed as previously described.

Chemicals

The 4,6-diaminopyrimidine VX680 (Cyclopropanecarboxylicarid{4[4(4-methyl-piperazin-1-yl)-6-(5-methyl-2H-pyrazol-3-ylamino)-pyrimidin-2-ylsulfanyl]-phenyl}-amide (ACC, San Diego, CA) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and stored at a final concentration of 10 mM at −80°C.

Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization

Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (iFISH) analysis was performed on CD138-purified plasma cells as described,5 using a set of probes for the chromosomal regions 1q21, 6q21, 8p21, 9q34, 11q23, 11q13, 13q14.3, 14q32, 15q22, 17p13, 19q13, 22q11, as well as the translocations t(4;14)(p16.3;q32.3) and t(11;14)(q13;q32,3), (Poseidon Probes, Madison, WI). The presence of clonal/subclonal aberrations for a single aberration (ie, present in ≥ 60% vs 20%-59% of assessed MMC) was defined as published.5 A modified copy number score (CS)5,38 (excluding gains of 1q21) and the score of Wuilleme et al39 using chromosomes 5, 15, 9 (CSW) were used to assess ploidy. For the assessment of the absolute number of chromosomal aberrations, 105 patients were assessed for the translocations t(4;14) and t(11;14), as well as numerical aberrations of the chromosomal regions 11q13, 11q23, 1q21, 17p13, 13q14.3, and 14q32. For the assessment of the presence of subclonal aberrations, an MMC sample was considered to contain a subclonal aberration if at least one aberration was detected in at least 70% of the MMCs present, and at least one other aberration was detected in 20% to 59% of assessed MMCs.

Gene expression profiling

RNA extraction was performed using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), the SV-total RNA extraction kit (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) and Trizol (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). Labeled cRNA was generated using the small sample labeling protocol vII (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), and hybridized to U133 A+B GeneChip microarray (Affymetrix) for training, and U133 2.0 plus arrays for the validation group, according to the manufacturer's instructions. When different probe sets were available for the same gene, we chose the probe set yielding the maximal variance and the highest signal. Aurora-A (Hs00233470_m1), aurora-B (Hs00177782_m1) and aurora-C (Hs00152930_m1 (all from Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany) gene expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR using the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System.40 The expression data were deposited in ArrayExpress under the accession numbers E-MTAB-81 and E-GEOD-2658.

Measurement of proliferation by 3H-thymidine

Proliferation of 20 HMCLs was investigated according to published protocols.41-43 Per well, 10 000 cells were cultured in 96-well plates in RPMI-1640 (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) containing 10% FCS (Invitrogen) with or without (medium control) graded concentrations (10, 2, 0.4, 0.08, 0.016, 0.0032 μM) of VX680. DMSO at the highest concentration present in the 10 μM well served as a DMSO control. For the HG and XG lines, 2 ng/mL IL-6 (R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany) was added. Proliferation was evaluated after 5 days of culture: cells were pulsed with 37 kBq of 3H-thymidine for 18 hours and harvested, then 3H-thymidine uptake was measured.

Measurement of proliferation of primary myeloma cells by propidium iodine

The Plasma Cell Labeling Index, that is, the percentage of MMCs in S-phase, was determined by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur. WBM (106 cells per tube) was incubated with 20 μL of either control IgG-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), CD38-FITC (both Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany; clones A07795 and A07778, respectively), or CD138-FITC (Diaclone, Stamford, CT; 954.501.010). After NH4-lysis, cells were resuspended with propidium iodine (PI) solution (1 mg/mL PI in 1× citrate buffer containing 0.1% Tween, 1 mg/mL RNase A [Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany]) for 45 minutes at 4°C. The percentage of CD138+ S-phase cells was determined using ModFit software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME), using a rectangular mathematical model for calculating the S-phase fraction as a percentage of the selected CD138+ plasma cells.

Survival of primary myeloma cells

Primary MMCs cultured together with their bone marrow microenvironment (negative fraction of plasma cell purification) of 5 newly diagnosed patients were exposed to concentrations of 100, 20, 4, 0.8, 0.16, 0.032 μM VX680. Cell viability was measured by CD138-FITC (IQ Products, Groningen, The Netherlands; clone B-A38) and PI (Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany) staining after 6 days of culture and referred to the medium and DMSO-control, respectively.44 One microliter of PI at a concentration of 50 μg/mL was used.

Apoptosis induction

XG-1 and -10 were cultured in 24-well plates at 105 cells per well in RPMI-1640 containing 10% FCS and 2 ng/mL IL-6 with or without 1 μM VX680. After 8, 24, 48, and 72 hours of culture, cells were stained for annexin V–FITC and PI according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pharmingen) and analyzed on a FACSAria.

Intracellular staining for aurora-A and -B

Intracellular aurora-A (clone 35C1; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) and -B (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) expression of 10 HMCLs were measured by flow cytometry using a fixation and permeabilization kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Overlays were established using the Infinicyt 1.1 software (Cytognos, Salamanca, Spain).

Western blotting

Cells were pelleted and resuspended in lysis buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.05), 50 mM sodium chloride, 30 mM sodium pyrophosphate decahydrate, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 5 μM zinc chloride, 1% Triton-X 100, and a protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Complete mini tablets; Roche, Basel, Switzerland). After pelleting, supernatants were mixed with loading buffer (Roti, Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany), heated for 5 minutes at 95°C, and separated on 10% NuPAGE Bis-tris gels (Invitrogen). Immunodetection was performed using the WesternBreeze Kit (Invitrogen). Membranes were incubated with antibodies against aurora-A, -B (see above), and β-actin (Ab5, Becton Dickinson) as loading control. HELA cells served as a positive control.

Statistical analysis

Gene expression data were normalized using GC Robust Multi-array Average.45 To assess the presence or absence of gene expression independently of Affymetrix mismatch probe sets, the Presence-Absence calls with Negative Probe sets (PANP) algorithm46 was used. Differential gene expression was assessed using empirical Bayes statistics in linear models for microarray data.47 P values were adjusted for multiple testing, controlling the false discovery rate as defined by Benjamini and Hochberg at a level of 5%.48 Expression profiles of 439 samples (233 MM, 14 BMPC, 12 PPC, 12 MGUS, 40 HMCL, 13 MBC, 64 WBM, 19 MSC, 5 CD3, 5 CD14, 5 CD15, 5 CD34, 7 OC, and 5 testis) divided into TG (n = 113, MM n = 65) and VG (n = 257, MM n = 168) were analyzed. As a further validation, 345 samples of newly diagnosed myeloma patients from the Arkansas group were analyzed.

EFS29 and OS29 were investigated for the 168 patients (48 TG, 120 VG) undergoing HDT and ASCT using Cox proportional hazard model. Two groups of patients with and without aurora-A expression were delineated. Findings were validated using the same strategy on the independent group of 345 patients from the Arkansas group. For myeloma cells, association of chromosomal aberrations and clinical parameters with gene expression was calculated using a 2-sample t statistic. Differences in clinical parameters between defined groups were investigated by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Correlation was measured using the Spearman correlation coefficient. Correlation with categorical variables was measured using the Kendall tau coefficient. For assessing the relationship between categorical variables, Fisher exact test was used. The centrosome index was calculated as described by Chng et al.49 For the calculations on the Arkansas group, our 7 BMPC samples were normalized together with the 345 MMC samples.

The gene-expression–based proliferation index was calculated as described in Document S1. In all statistical tests, an effect was considered statistically significant if the P value of its corresponding statistical test was not greater than 5%. All statistical computations were performed using R50 version 2.7.0 and Bioconductor51 version 2.2.

Results

Expression of aurora-A, -B, and -C

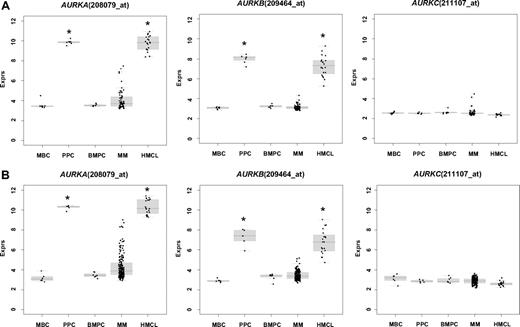

First, we assessed expression (Tables 1,2) and differential expression (Table S3A,B) of aurora-A, -B, and -C in primary myeloma cells, normal BMPCs, their precursors, as well as normal and myelomatous bone marrow. In our dataset, aurora-A and -B were expressed in 24% and 3% of primary myeloma cells and all PPCs, as well as HMCLs. In the Arkansas data, aurora-A, -B, and -C were expressed in 48/345 (14%), 12/345 (3%), and 0/345 (0%) of myeloma cell samples, respectively. The mean expression of aurora-A and -B was significantly (several orders of magnitude) higher in proliferating plasmablastic cells and cell lines compared with nonproliferating MBCs, or BMPCs (each P < .001 in TG and VG; Table S3A,B; Figure 1A). Aurora-A and -B were expressed in almost all bone marrow samples of healthy individuals and myeloma patients (Table 1). Here, the mean expression of aurora-B was significantly different (lower) in myelomatous compared with normal bone marrow (4.85 vs 3.81 arbitrary units, P = .009). A significant stage dependent differential gene expression could be found for aurora-A between myeloma cells from patients with early (MGUS and MMI) and advanced stage (MMII and MMIII) (P = .01 in both TG and VG). Aurora-A and -B expression correlated significantly in the VG (rs = 0.59, P < .001) and Arkansas group (rs = 0.61, P < .001).

Presence of expression of aurora kinases -A, -B, and -C

| Gene symbol . | Probe set . | MBC present (n = 13) . | PPC present(n = 12) . | BMPC present(n = 14) . | MGUS present(n = 12) . | MM present(n = 233) . | HMCL present(n = 40) . | ND-WBM present(n = 7) . | MM-WBM present(n = 57) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AURKA | 208079_s_at | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 24.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| AURKB | 209464_at | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 84.2 |

| AURKC | 211107_s_at | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Gene symbol . | Probe set . | MBC present (n = 13) . | PPC present(n = 12) . | BMPC present(n = 14) . | MGUS present(n = 12) . | MM present(n = 233) . | HMCL present(n = 40) . | ND-WBM present(n = 7) . | MM-WBM present(n = 57) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AURKA | 208079_s_at | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 24.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| AURKB | 209464_at | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 84.2 |

| AURKC | 211107_s_at | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

All values are expressed as percentages. Presence of expression of aurora kinase-A (AURKA), -B (AURKB), and -C (AURKC) as judged by PANP.

BMPC indicates normal bone marrow plasma cell; PPC, proliferating polyclonal plasmablastic cell; MBC, memory B cell; MMC, multiple myeloma cell; MGUS, cells from patients suffering from monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance; HMCL, human myeloma cell line; ND-WBM, whole bone marrow of normal donors; and MM-WBM, whole bone marrow of myeloma patients.

Presence of expression of aurora kinases -A, -B, and -C

| Gene symbol . | Probe set . | CD3 present(n = 5) . | CD14 present(n = 5) . | CD15 present(n = 5) . | CD34 present(n = 5) . | MSC-ND present(n = 7) . | MSC-MGUS present(n = 5) . | MSC-MM present(n = 7) . | OC present(n = 7) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AURKA | 208079_s_at | 0.0 | 60.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| AURKB | 209464_at | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 28.6 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| AURKC | 211107_s_at | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Gene symbol . | Probe set . | CD3 present(n = 5) . | CD14 present(n = 5) . | CD15 present(n = 5) . | CD34 present(n = 5) . | MSC-ND present(n = 7) . | MSC-MGUS present(n = 5) . | MSC-MM present(n = 7) . | OC present(n = 7) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AURKA | 208079_s_at | 0.0 | 60.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| AURKB | 209464_at | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 28.6 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| AURKC | 211107_s_at | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

All values are expressed as percentages. Presence of expression of aurora kinase-A (AURKA), -B (AURKB), and -C (AURKC) as judged by PANP in subfractions of bone marrow (mesenchymal stromal cells [MSCs] from healthy donors [MSC-ND], patients with monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance [MSC-MGUS], and myeloma patients [MSC-MM]; osteoclast [OC]).

Expression of aurora-A (AURKA), -B (AURKB), and -C (AURKC) as determined by gene expression profiling in memory B-cells (MBCs), polyclonal plasmablastic cells (PPCs), normal bone marrow plasma cells (BMPCs), multiple myeloma cells (MMCs), and human myeloma cell lines (HMCL) within the (A) training and (B) validation group. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference between the indexed population and both BMPCs and MBCs at a level of P < .001.

Expression of aurora-A (AURKA), -B (AURKB), and -C (AURKC) as determined by gene expression profiling in memory B-cells (MBCs), polyclonal plasmablastic cells (PPCs), normal bone marrow plasma cells (BMPCs), multiple myeloma cells (MMCs), and human myeloma cell lines (HMCL) within the (A) training and (B) validation group. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference between the indexed population and both BMPCs and MBCs at a level of P < .001.

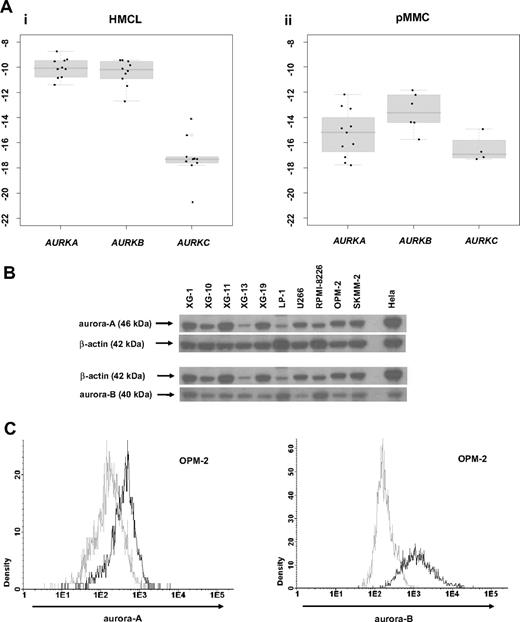

Validation of gene expression by qRT-PCR, Western blotting, and flow cytometry

To validate aurora kinase expression detected by gene expression profiling, we performed qRT-PCR, Western blotting, and flow-cytometric staining. Aurora-A expression in terms of “presence” or “absence” (Ct-value ≥ 35) by qRT-PCR was consistent with results by PANP in 10/11 primary myeloma cell samples. One sample deemed “absent” by qRT-PCR was judged “marginal” by PANP. Aurora-A expression by gene expression profiling (GEP) strongly correlated with the dCt value by qRT-PCR (rs = -0.87, P < .001). Aurora-B expression was consistent with results by PANP in 3 of 6 samples. All samples were “present” by qRT-PCR but 3 were judged “absent” by PANP. Aurora-B expression by GEP strongly correlated with the dCt value by qRT-PCR (rs = -0.83, P = .06). Aurora-C expression by qRT-PCR was consistent with absence of expression detected by PANP in 5/6 samples. One sample deemed “present” by qRT-PCR (Ct value 34.8) was judged “absent” by PANP. Aurora-C expression by GEP strongly correlated with the dCt value obtained by qRT-PCR (rs = -0.94, P = .02). Aurora-A and -B expression in HMCLs was further validated by Western blotting (Figure 2B) and intracellular flow cytometry (exemplary data shown in Figure 2C).

Validation of gene expression by quantitative real-time PCR, Western blotting, and flow cytometry. To validate gene expression data, quantitative real-time PCR for aurora-A, -B, -C in (Ai) 10 human myeloma cell lines (HMCLs) and (Aii) 10 primary multiple myeloma cell samples (pMMCs) was performed. Shown are -dCt values (reference gene 18S-RNA). (B) Gene expression data were further validated by Western blotting. Shown are the blots of 10 cell lines for aurora-A and -B with β-actin as a loading control and HELA cells as a positive control. (C) Intracytoplasmatic expression of aurora-A and -B as determined by flow cytometry. Shown is the cell line OPM-2. The light gray line indicates control without primary antibody; the black line, measurement with primary and secondary antibody.

Validation of gene expression by quantitative real-time PCR, Western blotting, and flow cytometry. To validate gene expression data, quantitative real-time PCR for aurora-A, -B, -C in (Ai) 10 human myeloma cell lines (HMCLs) and (Aii) 10 primary multiple myeloma cell samples (pMMCs) was performed. Shown are -dCt values (reference gene 18S-RNA). (B) Gene expression data were further validated by Western blotting. Shown are the blots of 10 cell lines for aurora-A and -B with β-actin as a loading control and HELA cells as a positive control. (C) Intracytoplasmatic expression of aurora-A and -B as determined by flow cytometry. Shown is the cell line OPM-2. The light gray line indicates control without primary antibody; the black line, measurement with primary and secondary antibody.

Association of aurora kinase expression with proliferation and chromosomal aberrations

To investigate the biologic impact of aurora kinase expression, we assessed the association with proliferation, chromosomal aberrations, presence of subclonal aberrations as detected by iFISH, and a published centrosome-index.49

The expression of aurora-A correlated with proliferation in terms of the plasma cell labeling index assessed by PI staining (n = 66, rs = 0.45, P < .001) and the gene-expression-based proliferation index in TG (rs = 0.62, P < .001) and VG (rs = 0.87, P < .001). The same held true for the latter for aurora-B in the VG (rs = 0.64, P < .001).

The absolute number of chromosomal aberrations was not significantly different between myeloma cells expressing or not expressing aurora-A (mean 5.1 and 5.1, n = 105 patients, n = 8 FISH-probes tested). Presence/absence of aurora-A expression did not significantly interrelate to the presence/absence of hyperdiploidy as determined by either CS or CSW, neither did the presence/absence of aurora-A expression interrelate to the presence of any of the single aberrations t(11;14), t(4;14), or numerical aberrations of 17p13, 9q34, 15q22, 19q13, 4p16, 14q32, or 22q11.

Interestingly, in patients with presence of aurora-A expression, gains of 11q13 (P = .03) and 11q23 (P = .004) were significantly less frequent compared with those with absent aurora-A expression. The opposite held true for patients with a gain of 1q21 (P = .002) or a deletion of 13q14 (P = .03), as well as a deletion of 8p21 (P = .03): MMCs of patients with present aurora-A expression showed a significantly higher number of these respective aberrations. For a gain of 1q21, for which data were also available from the Arkansas group, the same observation was made (n = 244, P < .001). However, subclonal aberrations per se were significantly more frequent in MMCs with absent aurora-A expression (67 with vs 37 without) compared with present aurora-A expression (18 vs 23, P = .03). For single aberrations, subclonal presence (vs full-clonal or absence of the respective aberration) was significantly more frequent in MMCs of patients with absence of aurora-A expression for gains of 11q13 (P < .03), 11q23 (P < .001), and losses of 13q14 (P = .009). Losses of 17p13 marginally failed to have significance (P = .06). Losses of 8p21 were significantly (P = .04) more frequent in patients with presence of aurora-A expression.

The centrosome index correlated with aurora-A expression in our series (TG r = 0.53, P < .001; VG r = 0.32, P < .001) and the Arkansas data (r = 0.43, P < .001). The centrosome-index was significantly predictive for EFS and OS in the Arkansas group (EFS P = .005, OS, P < .001) from which it was derived, but not in our series (EFS P = .09, OS, P = .99; Figure S1).

Prognostic value of aurora kinase expression

Next, we investigated whether the presence of aurora kinase expression had a prognostic impact in newly diagnosed myeloma patients treated with HDT and ASCT.

Presence of aurora-A expression in MMCs was an adverse prognostic factor in terms of EFS and OS in our data (n = 168; EFS: P = .003; hazard ratio [HR], 2.02; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26-3.25; OS: P = .03, HR, 2.31; 95% CI 1.04-5.15) and the Arkansas group (n = 345; EFS: P = .004; HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.18-2.57; OS: P = .008; HR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.16-2.95; Figure 3). The expression-signal of aurora-A as a single continuous variable was significantly predictive for EFS in the VG (n = 120, P < .001) and the Arkansas group (P < .001). The same held true for OS in the Arkansas group (P < .001) and it marginally failed significance for our VG (n = 120, P = .06).

Prognostic relevance of aurora-A expression for 2 independent groups of patients treated with high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. Shown are (A) event-free survival (EFS) and (B) overall survival (OS) in our cohort of patients (left side) and in the Arkansas group (right side) for absence (black curve) versus presence (gray curve) of aurora-A expression in CD138-purified myeloma cells. Presence of aurora-A expression in myeloma cells is an adverse prognostic factor in terms of EFS and OS in both groups. HM-group, Heidelberg/Montpellier-group.

Prognostic relevance of aurora-A expression for 2 independent groups of patients treated with high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. Shown are (A) event-free survival (EFS) and (B) overall survival (OS) in our cohort of patients (left side) and in the Arkansas group (right side) for absence (black curve) versus presence (gray curve) of aurora-A expression in CD138-purified myeloma cells. Presence of aurora-A expression in myeloma cells is an adverse prognostic factor in terms of EFS and OS in both groups. HM-group, Heidelberg/Montpellier-group.

In a Cox model tested with the International Staging System (ISS), presence of aurora-A expression appeared as an independent prognostic factor for EFS in our data (aurora-A expression [P = .003], ISS [P = .009]), and the Arkansas data (aurora-A expression [P < .001], ISS [P < .001]). For OS, aurora-A expression marginally failed independence (P = .08), ISS (P = .009) in our dataset but was significantly independent in the Arkansas data (P < .001), ISS (P < .001).

In a Cox model tested with serum-β2-microglobulin (B2M) as a continuous variable, presence of aurora-A expression appeared as an independent prognostic factor for EFS in our data (aurora-A expression [P = .002], B2M [P = .006]), and the Arkansas data (aurora-A expression [P < .001], B2M [P < .001]), and OS (aurora-A expression [P = .06], B2M [P < .001]), and the Arkansas-data (aurora-A expression [P < .001], B2M [P < .001]).

Activity of VX680 on myeloma cell lines and primary myeloma cells

Given the expression and prognostic value of aurora kinases, we tested the activity of the pan–aurora kinase inhibitor VX680 that has previously shown activity on a small series of human myeloma cells, on a large series of 20 myeloma cell lines. VX680 significantly inhibited proliferation of all HMCLs investigated (Figure 4Ai). The maximum inhibition at 10 μM ranged from 64.4% (HG-1) to 100% (OPM-2). The concentration to reduce proliferation to half of the control value (IC50) was reached in all myeloma cell lines and ranged from 0.003 to 2.715 μM (Figure 4Aii). No significant correlation could be found between the expression of aurora-A, -B or hyaluron-mediated motility receptor (HMMR) and the IC50 of 12 myeloma cell lines tested (see “Discussion”).

Inhibition of proliferation of myeloma cell lines as well as survival of primary myeloma cells and cells of the bone marrow microenvironment. (Ai) Inhibition of proliferation of 20 myeloma cell lines by the pan-aurora kinase inhibitor VX680 in graded concentrations versus medium and DMSO controls, respectively, measured by 3H-thymidine uptake. Two independent experiments were performed in triplicate. (Aii) The IC50 (in micromolarity) and maximal inhibition at 10 μM (IMAX10 expressed as a percentage) are shown. (Bi) Survival of primary myeloma cells (pMMCs) cultured within their bone marrow microenvironment (negative fraction of plasma cell purification) is significantly inhibited compared with the medium control, as determined by staining with anti-CD138-FITC antibody and propidium iodine. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant decrease between the medium control and the respective VX680 concentration. (Bii) Survival of cells within the bone marrow microenvironment (BMME cells; negative fraction of plasma cell purification) was determined as described above for pMMC. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant decrease between the medium control and the respective VX680 concentration. (C) Induction of apoptosis by VX680 at 1 μM as determined by annexin V staining after 8, 24, 48, and 72 hours.

Inhibition of proliferation of myeloma cell lines as well as survival of primary myeloma cells and cells of the bone marrow microenvironment. (Ai) Inhibition of proliferation of 20 myeloma cell lines by the pan-aurora kinase inhibitor VX680 in graded concentrations versus medium and DMSO controls, respectively, measured by 3H-thymidine uptake. Two independent experiments were performed in triplicate. (Aii) The IC50 (in micromolarity) and maximal inhibition at 10 μM (IMAX10 expressed as a percentage) are shown. (Bi) Survival of primary myeloma cells (pMMCs) cultured within their bone marrow microenvironment (negative fraction of plasma cell purification) is significantly inhibited compared with the medium control, as determined by staining with anti-CD138-FITC antibody and propidium iodine. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant decrease between the medium control and the respective VX680 concentration. (Bii) Survival of cells within the bone marrow microenvironment (BMME cells; negative fraction of plasma cell purification) was determined as described above for pMMC. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant decrease between the medium control and the respective VX680 concentration. (C) Induction of apoptosis by VX680 at 1 μM as determined by annexin V staining after 8, 24, 48, and 72 hours.

VX680 significantly inhibited the survival of primary myeloma cells cultivated within their bone marrow microenvironment from 5 of 5 newly diagnosed myeloma patients at a concentration of 4 μM (50%-100% inhibition; Figure 4Bi). At the same dose level, VX680 induced significant but lower toxicity within the bone marrow microenvironment (Figure 4Bii). All (4/4) samples for which sufficient RNA was available showed an expression of aurora-A by qRT-PCR.

Next, XG-1 and -10 were cultured for 3 days with or without VX680. Cell viability and apoptosis were determined by flow cytometric analysis of annexin V-binding and PI uptake after 8, 24, 48, and 72 hours. Exposure of XG-1 and -10 to 1 μM VX680 induced apoptosis after 8 hours (XG-1: 23.5% vs 24.1%, XG-10: 16.4% vs 13.3%) to 72 hours (XG-1: 17.9% vs 85.5%, XG-10: 9.0% vs 49.9%; Figure 4C, exemplary data shown for XG-10).

Discussion

Expression of aurora kinases

In our set of previously untreated myeloma patients (n = 233), expression of aurora-A and -B could be detected in 24% and 3% of purified myeloma cell samples. The same percentage of aurora-A and -B expression could be found for the subgroup of patients treated with HDT and ASCT (n = 168, 23.2% and 3.5%, respectively). In the independent dataset of Shaughnessy et al (n = 345), the same percentage of patients (3%) expressed aurora-B, but only 14% of patients expressed aurora-A at detectable levels. This observation could not be explained by the use of U133 A+B chips in some of our patients, as among these, the percentage of patients expressing aurora-A was even lower (10.4% of patients in the HDT cohort). Likewise, the use of a double amplification (our data) instead of single amplification protocol (Arkansas group) could not be taken as an explanation, as one would rather expect a higher percentage of detection in the single-amplification group. In an additional set of patients treated within the GMMG-HD4 trial, aurora-A expression could be detected in 43/70 (61%) of cases. Taken together, the percentage of patients expressing aurora-A seems to be quite variable in different patient populations, indicating a need to assess aurora-A expression when testing aurora inhibitors in clinical trials.

“Presence” of gene expression, as determined by gene-expression profiling based on PANP, needs to be interpreted as presence above the background level (“threshold”) seen for unspecific hybridization for negative strand matching probe sets. As such, a background correction is not performed when analyzing qRT-PCR data, which might have a detection threshold within the background of gene expression. This is 1 possible explanation for why in a previously published small series of patients, using qRT-PCR, Evans et al found all CD138-purified myeloma samples to express aurora-A (5/5)23 and aurora-B (7/7).24 Alternate explanations are the sampling of a more advanced (relapsed) patient population or contamination by other cell types, as in these series, purity of CD138-sorted plasma cells was only assessed by morphology, and expression of aurora-A and -B could be detected in almost all of our bone marrow samples (Tables 1,2).

The lower frequency of aurora-B compared with aurora-A expression in the same sample as detected by GEP seems likewise to be related to the detection-threshold: (1) In normal plasma cells, the expression levels of aurora-A and -B are of comparable height (Table S3A,B), but the differential expression of aurora-A in proliferating plasmablastic cells and myeloma cell lines is higher compared with aurora-B (Table S3A,B). (2) Despite of a tight correlation between qRT-PCR and gene expression profiling, qRT-PCR shows a comparable expression level for myeloma cell lines in terms of aurora-A and -B expression (mean Ct 27.6 vs 28.2). (3) All samples expressing aurora-B by PANP also express aurora-A.

Biologic implications

Aurora kinases have been associated with proliferation7 and genetic instability8 in different cancer entities,9-14 including MM.25

Aurora-A and -B are expressed in all myeloma cell lines and proliferating36 (nonmalignant) plasmablastic cells, and are expressed significantly more in both of these compared with memory B cells or normal plasma cells. At the same time, expression of aurora-A and -B correlates with the plasma cell labeling index determined by PI staining as well as the gene-expression–based proliferation index. Furthermore, the percentage of primary myeloma cells, from untreated patients, expressing aurora-A is in agreement with the low proliferative rate of these. The same holds true for the significant increase in aurora-A expression from early- to late-stage plasma cell dyscrasias in both our training and validation group. Thus, aurora kinase expression is obviously associated with proliferation in MM.

As chromosomal aberrations can be detected by iFISH in almost all primary myeloma cells5,6 (eg, in all our patients tested), but only myeloma cells from a minor fraction of myeloma patients express aurora-A or -B, aurora kinase expression in CD138-positive primary myeloma cells cannot be the cause of aneuploidy or ongoing genetic instability in myeloma. Two additional strong arguments are given by the fact that aurora-A or -B expression levels (or presence of expression) correlate with neither the median number of chromosomal aberrations in an individual sample nor the presence of subclonal (ie, emerging) aberrations. To the contrary, presence of subclonal aberrations at all is significantly associated with the absence of aurora-expression. The same holds true if the presence of specific subclonal aberrations is considered (11q13, 11q23, 13q14) versus clonal gain or normal copy number state, with the exception of deletions of 8p21. It is interesting to note that the aberrations 1q21 (gains), 13q14.3 (deletions), and 8p21 (deletions), the first 2 of which are associated with advanced stages,52,53 are significantly more frequent in myeloma cells expressing aurora-A. At the same time, gains of 11q13 and 11q23 are less frequent in myeloma cells expressing aurora-A.

It cannot, however, be ruled out by our analysis that aurora expression is present in a small fraction of myeloma cell precursors, that is, in putatively proliferating “myeloma stem cells,” thereby creating genomic instability, with this presence of aurora expression not being maintained in the differentiated nonproliferating progeny. If this is the case, one would expect that the presence of aurora expression within the myeloma stem cells leads to a higher number of clonal and subclonal chromosomal aberrations in patients in relapsed- or advanced- compared to early-stage myeloma. At the same time, structural aberrations or point mutations in the aurora kinase genes of myeloma cells might be present as indicators for a respective role of aurora kinase expression in putative myeloma stem cells. Both investigations, beyond the scope of this study, are currently being performed by our group.

Taken together, it is unlikely that aurora kinase expression in CD138-purified myeloma cells drives genetic instability in myeloma, but is, as a high labeling index and the presence of chromosomal aberrations associated with disease “progression,” rather a sign of proliferative, “advanced” myeloma cells.

Prognostic value of aurora kinase expression

Presence of aurora-A expression in myeloma cells is an adverse prognostic factor in terms of EFS and OS in our data (n = 168) and the Arkansas group (n = 345, Figure 3), as is the expression-height of aurora-A as a single continuous variable. In a Cox model, tested with either ISS or B2M (as a continuous variable), presence of aurora-A expression appears as an independent prognostic factor for EFS and OS. Of note, aurora-A (STK6) is also one of the genes within the gene-expression-based high-risk score for myeloma.54 Aurora-A kinase expression in our dataset correlates with the gene-expression-based centrosome index that has likewise shown prognostic significance in the Arkansas dataset49 (Figure S1). Thus, direct assessment of aurora-A kinase expression allows identification of a poor-risk patient population independent of B2M or ISS.

Inhibition of proliferation of HMCLs and primary MMCs by aurora kinase inhibitors

Proliferation of all tested 20 myeloma cell lines was significantly inhibited by VX680, with an IC50 ranging from 0.003 to 2.715 μM (Figure 4Aii). The observed minimal IC50 is in the range of data from Tyler et al,19 who have shown an inhibition of in vitro kinase activity by VX680 in terms of phosphorylation of histone-H3 by aurora-A, -B, and -C (with IC50 values of 36, 18, and 25 nM, respectively); aurora-A and -B kinase activity was completely abrogated at 1 μM.19 VX680 induced a marked delay in mitosis, presumably due to aurora-A dependent effects on spindle bipolarity, but did override a mitotic arrest imposed by several experimental agents, indicating an effect on the spindle assembly checkpoint, likely through aurora-B inhibition.19 Our data are in agreement with VX680 having been shown to induce a dose-dependent inhibition of proliferation on myeloma cell lines.25 Inhibition of proliferation by VX680 was accompanied, in our study, by apoptosis induction in myeloma cell lines and primary myeloma cell samples, in agreement with findings from Shi et al.25 Driven by the published observation that forced overexpression of aurora-A reduces,25 and down-regulation by siRNA increases,23 the susceptibility of myeloma cell lines to aurora kinase inhibitors, we investigated whether the IC50 in 12 myeloma cell lines tested might correlate with the expression level of aurora-A. However, in our study, it did not. The same observation was made in terms of expression of HMMR, for which a forced up-regulation was described to increase, and a down-regulation to decrease, the sensitivity of the respective myeloma cell line;25 but our data did not reflect these findings. This might be explained by a plethora of growth and survival factors differentially expressed between HMCLs, causing a high inter–cell-line variance in terms of sensitivity to VX680 (Figure 4Aii). Thus, only if aurora-A or HMMR expression is the single parameter varied (eg, by siRNA) within one cell line, differences in the sensitivity of the respective HMCL might be seen.

Implications for myeloma treatment

The presence of multiple chromosomal aberrations in MM suggests that, during the evolution of myeloma, a disruption of cell cycle checkpoints has occurred. This would normally arrest cells at the G1/S and G2/M transitions or at mitosis when DNA damage or spindle abnormalities have occurred, thus allowing for potential repair of damage.25 Alternatively, or in addition, these checkpoints might be “overruled” by intrinsic aberrant or increased expression of D-type cyclins, myeloma growth, and survival factors (“strained” checkpoints). In both cases, myeloma cells might be particularly susceptible to the induction of apoptotic death in mitosis (the so-called mitotic catastrophe55 ) when further assaults on the mitotic machinery are induced. Experimental evidence for the latter is given by the fact that VX680 inhibits proliferation of both CD3/CD28- or phytohemaglutinin-stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes and myeloma cell lines, but induces apoptosis only in human myeloma cell lines.25 Thus, aurora kinase inhibitors are indicated in MM not because myeloma cells show a genetic instability, but because aurora kinase inhibitors target and inhibit the proliferation of myeloma cells. They might do this especially efficiently because they (additionally) induce apoptosis in the presence of strained or deranged cell-cycle checkpoints present in primary myeloma cells and human myeloma cell lines.

Conclusion

Aurora-A is expressed at varying frequencies in CD138-purified myeloma cells of newly diagnosed patients. Its expression significantly interrelates with proliferation, but not with a higher number of chromosomal aberrations (aneuploidy) or subclonal aberrations (genetic instability). Using gene expression profiling, aurora kinase inhibitors as a promising therapeutic option in myeloma can be tailoredly given to patients expressing aurora-A, who in turn have an adverse prognosis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Véronique Pantesco, Katrin Heimlich, Maria Dörner, and Margit Happich for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Hopp-Foundation (Germany); the University of Heidelberg (Heidelberg, Germany); the National Center for Tumor Diseases (Heidelberg, Germany); the Tumorzentrum Heidelberg/Mannheim, Germany; the European Myeloma Stem Cell Network (MSCNET) funded within the 6th Framework Program of the European Community; the Deutsche Krebshilfe (Bonn, Germany); and the Ligue Nationale Contre Le Cancer équipe labellisée (Paris, France). It is also part of a national program called “Carte d'Identité des Tumeurs” (CIT) funded by the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer.

Authorship

Contribution: D.H. designed research, wrote the paper, and participated in the microarray experiments; T. Meissner, A.B., and T.H. performed statistical analysis, A.S. performed experiments and participated in the writing of the paper; J.L., V.B., J.B., and J.Z. participated in the analysis of the data; J.F.R., U.B., J.H., and M.H. collected bone marrow samples and clinical data; B.B. and J.S. performed the total therapy 2 trial and J.S. the microarray experiments for the Arkansas group; J.M., K.N., and A.K. participated in the writing and review of the paper; J.D.V. participated in the microarray experiments; A.J. contributed in performing the interphase-FISH experiments; and T.R., T. Möhler, B.K., and H.G. participated in the analyzing of the data and in the writing of the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dirk Hose, Medizinische Klinik V, Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg, Im Neuenheimer Feld 410, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; e-mail: dirk.hose@med.uni-heidelberg.de.