Abstract

AMN107 is a small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor developed, in the first instance, as a potent inhibitor of breakpoint cluster region-abelson (BCR-ABL). We tested its effectiveness against fusion tyrosine kinases TEL–platelet-derived growth factor receptorβ (TEL-PDGFRβ) and FIP1-like-1 (FIP1L1)–PDGFRα, which cause chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and hypereosinophilic syndrome, respectively. In vitro, AMN107 inhibited proliferation of Ba/F3 cells transformed by both TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα with IC50 (inhibitory concentration 50%) values less than 25 nM and inhibited phosphorylation of the fusion kinases and their downstream signaling targets. The imatinib mesylate–resistant mutant TEL-PDGFRβ T681I was sensitive to AMN107, whereas the analogous mutation in FIP1L1-PDGFRα, T674I, was resistant. In an in vivo bone marrow transplantation assay, AMN107 effectively treated myeloproliferative disease induced by TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα, significantly increasing survival and disease latency and reducing disease severity as assessed by histopathology and flow cytometry. In summary, AMN107 can inhibit myeloid proliferation driven by TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα and may be a useful drug for treatment of patients with myeloproliferative disease who harbor these kinase fusions.

Introduction

The small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) is effective in clinical treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) caused by the oncogenic tyrosine kinase breakpoint cluster region-abelson (BCR-ABL).1-5 In addition to inhibition of ABL, imatinib mesylate also inhibits the platelet-derived growth factor receptorβ (PDGFRβ), PDGFRα, and c-kit receptor tyrosine kinase (KIT) tyrosine kinases. It has recently been shown to be effective in a number of other malignancies that are caused by activated tyrosine kinases, including hematopoietic disorders such as chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML)6 associated with rearrangements of PDGFRβ, hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES)7 associated with the FIP1-like-1 (FIP1L1)–PDGFRα fusion, and solid tumors, including gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs)8 associated with activating mutations in KIT. However, clinical resistance to imatinib mesylate is emerging as an important problem resulting from acquisition of point mutations in the targeted kinase that interfere with binding of imatinib mesylate and render tumor cells resistant to kinase inhibition.9 Because of the development of resistance mutations, the generation of novel kinase inhibitors is important to provide therapeutic alternatives to imatinib mesylate.

AMN107 was rationally designed as a novel BCR-ABL inhibitor based on an understanding of the binding of imatinib mesylate to the Abl kinase domain.10,11 Like imatinib mesylate, it interferes with tyrosine kinase activity by binding to the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding site when the kinase is in an inactive conformation. AMN107 inhibits both BCR-ABL autophosphorylation and proliferation of BCR-ABL–transformed cells with a higher potency than imatinib mesylate.11 In addition, AMN107 is active against a number of BCR-ABL mutations known to confer imatinib mesylate resistance both in vitro and in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia.12,13 AMN107 also inhibits growth of cell lines transformed with activated KIT, PDGFRα, and PDGFRβ tyrosine kinases and reduces autophosphorylation of these kinases.11 Notably, the ranking of affinities for these kinases is different for AMN107 (BCR-ABL > PDGFR > KIT) compared with imatinib mesylate (PDGFR > KIT > BCR-ABL).10 AMN107 does not have activity against cell lines transformed by a wide spectrum of other kinases (eg, ErbB2 [c-erbB-2 protein], FLT3 [FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3], EGFR [epidermal growth factor receptor], Src, Ras).11

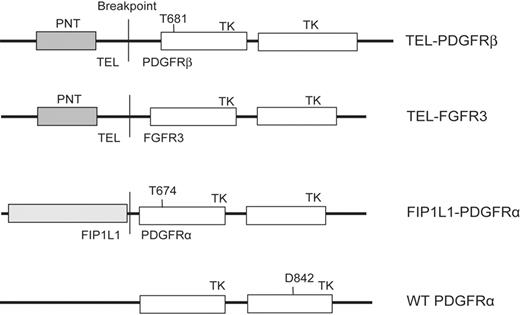

TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα constructs. Constructs used in this study, cloned in retroviral vectors MSCV-IRES-EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein), MSCV-neomycin, or MSCV-puromycin as indicated in “Materials and methods.” PNT indicates the pointed domain in TEL that mediates dimerization of the fusion protein; TK, the tyrosine kinase domains.

TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα constructs. Constructs used in this study, cloned in retroviral vectors MSCV-IRES-EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein), MSCV-neomycin, or MSCV-puromycin as indicated in “Materials and methods.” PNT indicates the pointed domain in TEL that mediates dimerization of the fusion protein; TK, the tyrosine kinase domains.

In this study, we sought to determine whetherAMN107 could inhibit the TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα fusion kinases in vitro and in vivo and to test its efficacy against imatinib mesylate–resistance mutations. TEL-PDGFRβ is a fusion kinase that is associated with some cases of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), a rare myeloproliferative disorder characterized clinically by abnormal myelopoiesis, eosinophilia, myelofibrosis, and frequent progression to acute myeloid leukemia14,15 and histologically by monocytic proliferation in peripheral blood and bone marrow, often accompanied by abnormalities in other lineages such as neutrophilia or eosinophilia.16 The TEL-PDGFRβ fusion is inhibited by imatinib mesylate in vitro,15,17,18 and patients with CMML have been successfully treated with imatinib mesylate.6

FIP1L1-PDGFRα is a fusion kinase associated with hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) or chronic eosinophilic leukemia, a rare clonal myeloproliferative disorder associated with prominent blood eosinophilia and organ damage7,19,20 and characterized histologically by excess eosinophils in blood and bone marrow, as well as abnormalities in the number or morphology of other cell types (eg, neutrophils, basophils).16 Patients with FIP1L1-PDGFRα account for approximately 50% of HES cases7 and are also highly responsive to imatinib mesylate therapy.21-24 However, point mutations have been identified in both TEL-PDGFRB18 and FIP1L1-PDGFRA7 that confer imatinib mesylate resistance in vitro, and clinical resistance to imatinib mesylate has been reported in HES.7

Here, we report that AMN107 inhibits cell proliferation driven by both of these fusion kinases in vitro and is effective against myeloproliferative disease caused by TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα in murine bone marrow transplantation models. In addition, our in vitro data showed that AMN107 could overcome the imatinib mesylate–resistant point mutation T681I in TEL-PDGFRβ but not the corresponding mutation T674I in FIP1L1-PDGFRα. AMN107 may therefore be an alternative to imatinib mesylate therapy in patients with TEL-PDGFRβ or FIP1L1-PDGFRα.

Materials and methods

Constructs

TEL-PDGFRβ,25 FIP1L1-PDGFRα,7 and FIP1L1-PDGFRα T674I7 cloned in murine stem cell virus–internal ribosome entry site–enhanced green fluorescent protein (MSCV-IRES-EGFP [MSCV-GFP]), and TEL-PDGFRβ,25 TEL-PDGFRβ T681I,18 and TEL-FGFR326 cloned in MSCV-neomycin (MSCV-neo) have been previously described. A D842V mutation was introduced into wild-type PDGFRA cDNA and cloned in MSCV-puromycin (MSCV-puro).27 Constructs and their respective inhibitory concentration 50% (IC50) values for imatinib mesylate are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Imatinib IC50 values of TEL-PDGFRβ and FIL1P1-PDGFRα constructs

. | Imatinib IC50 . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|

| TEL-PDGFRβ | 50 nM | 18 |

| TEL-PDGFRβ T681I | n/a | 18 |

| FIP1L1-PDGFRα | 3 nM | 7 |

| FIP1L1-PDGFRα T674I | n/a | 7 |

| PDGFRα D842V | ∼1 μM | 27,34 |

. | Imatinib IC50 . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|

| TEL-PDGFRβ | 50 nM | 18 |

| TEL-PDGFRβ T681I | n/a | 18 |

| FIP1L1-PDGFRα | 3 nM | 7 |

| FIP1L1-PDGFRα T674I | n/a | 7 |

| PDGFRα D842V | ∼1 μM | 27,34 |

Imatinib concentration resulting in 50% growth inhibition of Ba/F3 cells stably transduced with the constructs used in this study.

n/a indicates that 50% inhibition of cell growth was not achieved at the highest drug concentration tested.

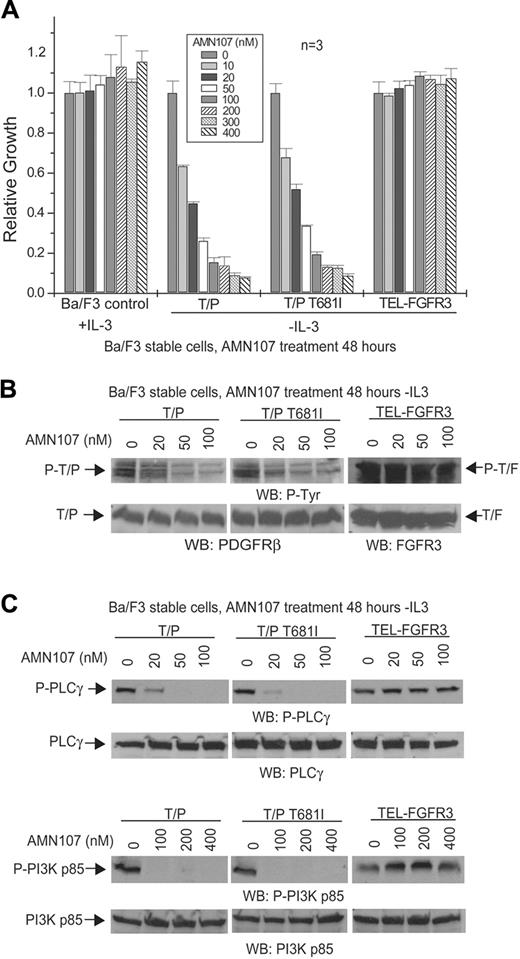

AMN107 inhibits TEL-PDGFRβ in vitro. (A) Dose-dependent effects of AMN107 on growth of TEL-PDGFRβ–transformed Ba/F3 cells. Ba/F3 cells stably transduced with the indicated constructs were treated with AMN107 for 48 hours in the absence of IL-3, and the proliferation of treated cells relative to untreated cells was determined. Ba/F3 control cells were treated in the presence of IL-3. Values reflect mean of 3 samples; error bars show standard deviation. T/P indicates TEL-PDGFRβ; T/F, TEL-FGFR3. (B) Analysis of phosphorylation of TEL-PDGFRβ in response to AMN107. TEL-PDGFRβ– or TEL-FGFR3–transformed Ba/F3 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of AMN107 in the absence of serum and IL-3, and whole-cell lysates were prepared for Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine and anti-PDGFRβ or anti-FGFR3. (C) Analysis of phosphorylation of downstream effectors of TEL-PDGFRβ. Whole-cell lysates from Ba/F3 cells transformed with the indicated constructs were analyzed for phosphorylation of PLCγ and PI3K, downstream effectors of PDGFRβ signaling.

AMN107 inhibits TEL-PDGFRβ in vitro. (A) Dose-dependent effects of AMN107 on growth of TEL-PDGFRβ–transformed Ba/F3 cells. Ba/F3 cells stably transduced with the indicated constructs were treated with AMN107 for 48 hours in the absence of IL-3, and the proliferation of treated cells relative to untreated cells was determined. Ba/F3 control cells were treated in the presence of IL-3. Values reflect mean of 3 samples; error bars show standard deviation. T/P indicates TEL-PDGFRβ; T/F, TEL-FGFR3. (B) Analysis of phosphorylation of TEL-PDGFRβ in response to AMN107. TEL-PDGFRβ– or TEL-FGFR3–transformed Ba/F3 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of AMN107 in the absence of serum and IL-3, and whole-cell lysates were prepared for Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine and anti-PDGFRβ or anti-FGFR3. (C) Analysis of phosphorylation of downstream effectors of TEL-PDGFRβ. Whole-cell lysates from Ba/F3 cells transformed with the indicated constructs were analyzed for phosphorylation of PLCγ and PI3K, downstream effectors of PDGFRβ signaling.

Cell culture, retrovirus production, and transduction of Ba/F3 cells

293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Ba/F3 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (RPMI) + 10% FBS + 1 ng/mL mouse interleukin 3 (IL-3). Retroviral supernatants were generated as previously described28 and used to transduce Ba/F3 cells. TEL-PDGFRβ MSCV-neo and TEL-FGFR3 MSCV-neo cell lines were selected with 1 mg/mL G418 in the presence of IL-3 for 8 to 10 days and maintained in the presence of IL-3. FIP1L1-PDGFRα MSCV-GFP cell lines were selected in RPMI lacking IL-3 for 7 to 10 days and maintained in the absence of IL-3. PDGFRα D842V MSCV-puro cell lines were selected in 2 μg/mL puromycin for 7 to 14 days and maintained in the absence of IL-3.

IL-3 independence cell-proliferation assays

AMN107 (4-methyl-N-[3-(4-methyl-1H-imidazol)-5-(trifluoromethyl) phenyl]-3-(3-pyridinyl)-2pyridinyl]amino] benzamide; Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland) powder was dissolved and stored as a 10-mM stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted in RPMI for use. Ba/F3 cells (1 × 105) were incubated with AMN107 at the indicated concentrations in RPMI in the absence of IL-3 (except for Ba/F3 or vector-transduced control cells, which were grown in the presence of IL-3). Growth of cells was quantified at 24-hour intervals using the Celltiter96 AqueousOne assay (Promega, Madison, WI) and normalized to values for untreated cells. All experiments were done in triplicate and repeated at least twice.

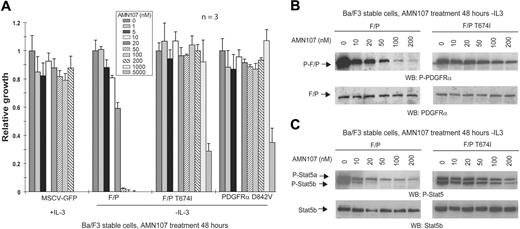

AMN107 inhibits FIP1L1-PDGFRα in vitro. (A) Dose-dependent effects of AMN107 on growth of FIP1L1-PDGFRα–transformed Ba/F3 cells. Ba/F3 cells stably transduced with the indicated constructs were treated with AMN107 for 48 hours in the absence of IL-3, and the proliferation of treated cells relative to untreated cells was determined. MSCV-GFP–transduced control cells were incubated in the presence of IL-3. Values reflect the mean of 3 samples; error bars show standard deviation. F/P indicates FIP1L1-PDGFRα. (B) Analysis of phosphorylation of FIP1L1-PDGFRα after AMN107 treatment. Ba/F3 cells transformed with FIP1L1-PDGFRα or FIP1L1-PDGFRα T674I were incubated with increasing concentrations of AMN107 in the absence of serum and IL-3. Whole-cell lysates were prepared for Western blotting with anti–phospho-PDGFRα and anti-PDGFRα. (C) Analysis of phosphorylation of Stat5, a downstream effector of PDGFRα, after AMN107 treatment. Ba/F3 cells transformed with FIP1L1-PDGFRα or FIP1L1-PDGFRα T674I were treated with increasing concentrations of AMN107 in the absence of serum and IL-3. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for phosphorylation of Stat5, which is induced by IL-3 or by activated kinases that confer IL-3 independence. Western blotting was performed with anti–phospho-Stat5 and anti-Stat5b.

AMN107 inhibits FIP1L1-PDGFRα in vitro. (A) Dose-dependent effects of AMN107 on growth of FIP1L1-PDGFRα–transformed Ba/F3 cells. Ba/F3 cells stably transduced with the indicated constructs were treated with AMN107 for 48 hours in the absence of IL-3, and the proliferation of treated cells relative to untreated cells was determined. MSCV-GFP–transduced control cells were incubated in the presence of IL-3. Values reflect the mean of 3 samples; error bars show standard deviation. F/P indicates FIP1L1-PDGFRα. (B) Analysis of phosphorylation of FIP1L1-PDGFRα after AMN107 treatment. Ba/F3 cells transformed with FIP1L1-PDGFRα or FIP1L1-PDGFRα T674I were incubated with increasing concentrations of AMN107 in the absence of serum and IL-3. Whole-cell lysates were prepared for Western blotting with anti–phospho-PDGFRα and anti-PDGFRα. (C) Analysis of phosphorylation of Stat5, a downstream effector of PDGFRα, after AMN107 treatment. Ba/F3 cells transformed with FIP1L1-PDGFRα or FIP1L1-PDGFRα T674I were treated with increasing concentrations of AMN107 in the absence of serum and IL-3. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for phosphorylation of Stat5, which is induced by IL-3 or by activated kinases that confer IL-3 independence. Western blotting was performed with anti–phospho-Stat5 and anti-Stat5b.

Western blots

For TEL-PDGFRβ experiments, Ba/F3 cells stably expressing TEL-PDGFRβ or TEL-FGFR3 were treated with AMN107 for 4 hours in RPMI without FBS or IL-3 prior to lysis. The cell extracts were clarified by centrifugation and used for immunoblotting. The enzyme-linked immunoblotting procedures were performed as described.29 Applied antibodies included rabbit anti-PDGFRβ serum (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA); rabbit anti–phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K; p85) serum, mouse anti–phosphotyrosine 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnology, Charlottesville, VA); antibodies against fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 (FGFR3), phospho-PI3K p85 (Tyr-508) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ), phospho-PLCγ (Tyr-783) (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA).

For FIP1L1-PDGFRα experiments, Ba/F3 cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of AMN107 for 4 hours in RPMI without FBS or IL-3. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (PBS [phosphate-buffered saline] with 1 M Na2EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid], 1 M NaF, 0.1% Triton X-100, 200 mM Na3VO4, 200 mM phenylarsine oxide, and complete protease inhibitor tablets [Roche, Indianapolis, IN]). Protein lysate (50 μg) was combined with reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer + dithiothreitol (Cell Signaling) prior to electrophoresis on 10% to 12% SDS-PAGE (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Antibodies used were anti–phospho-PDGFRα (Tyr 720), anti–PDGFRα (951), anti–Stat5-b (signal transducer and transcriptional activator 5-b; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti–phospho-Stat5 (Tyr 694) (Cell Signaling); anti–rabbit peroxidase (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Bone marrow transplantations and drug treatment of mice

Murine bone marrow transplantation experiments were performed as previously described.28,30 Briefly, MSCV-GFP retroviral supernatants were titered by transducing Ba/F3 cells with supernatant (plus polybrene, 10 μg/mL) and analyzing for the percentage of GFP+ cells by flow cytometry at 48 hours after transduction. Balb/C donor mice (Taconic, Germantown, NY) were treated for 5 to 6 days with 5-fluorouracil (150 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection). Bone marrow cells from donor mice were harvested, treated with red blood cell lysis buffer, and cultured 24 hours in transplantation medium (RPMI + 10% FBS + 6 ng/mL IL-3, 10 ng/mL IL-6, and 10 ng/mL stem-cell factor). Cells were treated by spin infection with retroviral supernatants (1 mL supernatant per 4 × 106 cells, plus polybrene) and centrifuged at 1800g for 90 minutes. The spin infection was repeated 24 hours later, and the cells were then washed, resuspended in Hanks balanced salt solution, and injected into lateral tail veins of lethally irradiated (2 × 4.5 Gy [450 rad]) Balb/C recipient mice (Taconic) at 0.5 to 1.0 × 106 cells/mouse. AMN107 powder was dissolved to give a stock solution in NMP (N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) and diluted in polyethylene glycol 300 (Sigma-Aldrich) for injections. Starting at day 11 after transplantation, animals were treated with 75 mg/kg/d AMN107 or placebo (polyethylene glycol, identical volume as AMN107) every 24 hours by oral gavage with 22-gauge gavage needles. Animals were humanely killed when they had palpable splenomegaly or were moribund, or, if healthy, 7 days after death of the last animal in the placebo group.

Analysis of myeloproliferative disease in mice

Peripheral blood was collected from the retroorbital cavity using heparinized glass capillary tubes and analyzed by automated complete and differential blood-cell counts and blood smears (stained with Wright and Giemsa). Single-cell suspensions of spleen and bone marrow were prepared by pressing tissue through a cell strainer, followed by red blood cell lysis.28,30 Cells were frozen in 90% FBS, 10% DMSO.

For histopathology, tissues were fixed for at least 72 hours in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, dehydrated in alcohol, cleared in xylene, and infiltrated with paraffin on an automated processor. The tissue sections (4 μm) from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were placed on charged slides and deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through graded alcohol solutions, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histologic images were obtained on a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a SPOT RT color digital camera model 2.1.1 (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). The microscope was equipped with a 10× /22 ocular lens. Low-power images (× 100) were obtained with a 10× /0.25 objective lens. High-power images (× 600) were obtained with a 60 × /1.4 objective lens with oil (Trak 300; Richard Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI). Images were analyzed in Adobe Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

For flow cytometry, cells were washed in PBS + 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), blocked with Fc-Block (BD Pharmingen) for 10 minutes on ice, and stained with monoclonal antibodies in PBS + 1% BSA for 20 minutes on ice. Antibodies used were allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated Gr-1 and CD19; and phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated Mac-1 and B220 (BD Pharmingen). Flow cytometric analysis was performed on a FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and analyzed with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Viability was assessed by incubating cells with 7AAD (7-amino-actinomycin D; BD Pharmingen) for 5 minutes prior to flow cytometry. Cells were gated for viability (using forward/side scatter and 7AAD) and GFP positivity, and 10 000 events were analyzed from this subset for marker expression.

Statistical significance of differences between AMN107- and placebo-treated groups in survival time were assessed by a log-rank test, and differences in white blood cell counts and spleen weights were assessed using a 2-sided Mann-Whitney U test.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Children's Hospital Animal Care and Use Committee.

Results

AMN107 inhibits TEL-PDGFRβ in vitro

We first tested whether AMN107 could inhibit the kinase activity of a TEL-PDGFRβ fusion protein and overcome imatinib mesylate resistance conferred by a T681I mutation within the PDGFRβ kinase domain.

Ba/F3 is a murine hematopoietic cell line that requires IL-3 for growth, but activated kinases such as BCR-ABL, TEL-PDGFRβ, or FIP1L1-PDGFRα transform Ba/F3 cells to become growth factor independent. TEL-PDGFRβ was subcloned into a retroviral vector carrying a neomycin-resistance gene and stably transduced in Ba/F3 cells. Stable Ba/F3 cell lines were assessed for IL-3–independent growth as a surrogate for transformation in the presence of increasing concentrations of AMN107.

AMN107 inhibited Ba/F3 cells transformed with TEL-PDGFRβ with an IC50 of 18.1 nM (Figure 2A; Table 2) (the IC50 for imatinib mesylate in this context is ∼ 50 nM).18 Consistent with this observation, AMN107 treatment also effectively inhibited TEL-PDGFRβ tyrosine autophosphorylation, as well as the phosphorylation of known PDGFRβ signaling intermediates such as PLCγ and PI3K (Figure 2B-C).

AMN107 inhibition of TEL-PDGFRβ and TEL-PDGFRβ T681I

. | IC50, nM . |

|---|---|

| Ba/F3 | n/a |

| TEL-PDGFRβ | 18.1 |

| TEL-PDGFRβ T681I | 22.2 |

| TEL-FGFR3 | n/a |

. | IC50, nM . |

|---|---|

| Ba/F3 | n/a |

| TEL-PDGFRβ | 18.1 |

| TEL-PDGFRβ T681I | 22.2 |

| TEL-FGFR3 | n/a |

IC50 = AMN 107 concentration resulting in 50% growth inhibition of Ba/F3 cells stably transduced with the constructs listed.

n/a indicates that 50% inhibition of cell growth was not achieved at the highest drug concentration tested. Ba/F3 indicates untransduced control cells.

The T315I mutation in BCR-ABL confers resistance to imatinib mesylate and is not inhibited by any known small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor.13,31 The homologous mutation in TEL-PDGFRβ is T681I, and this mutation also confers imatinib mesylate resistance in vitro18 (although, to our knowledge, it has not yet been identified in patients). Notably, AMN107 inhibited Ba/F3 cells transformed by a TEL-PDGFRβ T681I mutant with an IC50 of 22.2 nM, similar to that of the nonmutated TEL-PDGFRβ fusion.

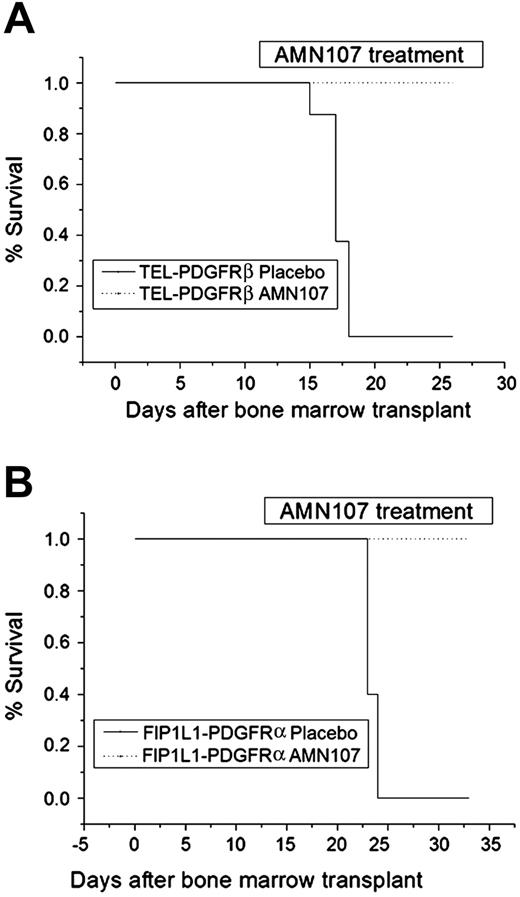

AMN107 prolongs survival of animals with myeloproliferative disease induced by TEL-PDGFRβ or FIP1L1-PDGFRα in a murine bone marrow transplantation model. Bone marrow cells of donor mice were transduced with retrovirus expressing either TEL-PDGFRβ (A) or FIP1L1-PDGFRα (B) and transplanted into lethally irradiated recipients. Animals were monitored for appearance of disease and were killed when moribund. The plot shows cumulative disease-free survival of mice that received a transplant with cells expressing each fusion kinase and treated with either AMN107 (75 mg/kg/d) or placebo, starting at day 11 after transplantation. An increase in survival in the AMN107-treated group was statistically significant for both TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα (P < .001); n = 8 for TEL-PDGFRβ and n = 5 for FIP1L1-PDGFRα.

AMN107 prolongs survival of animals with myeloproliferative disease induced by TEL-PDGFRβ or FIP1L1-PDGFRα in a murine bone marrow transplantation model. Bone marrow cells of donor mice were transduced with retrovirus expressing either TEL-PDGFRβ (A) or FIP1L1-PDGFRα (B) and transplanted into lethally irradiated recipients. Animals were monitored for appearance of disease and were killed when moribund. The plot shows cumulative disease-free survival of mice that received a transplant with cells expressing each fusion kinase and treated with either AMN107 (75 mg/kg/d) or placebo, starting at day 11 after transplantation. An increase in survival in the AMN107-treated group was statistically significant for both TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα (P < .001); n = 8 for TEL-PDGFRβ and n = 5 for FIP1L1-PDGFRα.

In control experiments, AMN107 did not inhibit growth of Ba/F3 cells stably transduced with the TEL-FGFR3 fusion kinase (Figure 2A; Table 2) and had no effect on FGFR3 phosphorylation or signaling (Figure 2B-C), demonstrating that AMN107 selectively inhibits PDGFRβ and that TEL-PDGFRβ is the critical target for AMN107-mediated cytotoxicity. Furthermore, AMN107 had no effect on growth of normal Ba/F3 cells in the presence of IL-3 at the concentrations tested (Figure 2A; Table 2), confirming that the growth inhibition of TEL-PDGFRβ Ba/F3 cells was not due to nonspecific toxicity of AMN107 on Ba/F3 cells.

AMN107 inhibits FIP1L1-PDGFRα in vitro but not a T674I point mutant

We next evaluated the capacity of AMN107 to inhibit the constitutively activated fusion tyrosine kinase FIP1L1-PDGFRα. AMN107 inhibited growth of FIP1L1-PDGFRα–transformed Ba/F3 cells at an IC50 of 23 nM (Figure 3A; Table 3) (the corresponding IC50 for imatinib mesylate is ∼ 3 nM).7 AMN107 treatment of FIP1L1-PDGFRα Ba/F3 cells also inhibited tyrosine autophosphorylation of FIP1L1-PDGFRα (Figure 3B) and reduced phosphorylation of its downstream signaling effector Stat5 (Figure 3C). When FIP1L1-PDGFRα Ba/F3 cells were treated with AMN107 in the presence of IL-3, Stat5 phosphorylation was maintained (data not shown). EOL-1, a human eosinophilic leukemia cell line that harbors the FIP1L1-PDGFRα fusion,32,33 was also inhibited by AMN107 with an IC50 value in the range of 1 to 10 nM (data not shown).

AMN107 inhibition of FIP1L1-PDGFRα

. | IC50, nM . |

|---|---|

| MSCV-GFP | n/a |

| FIP1L1-PDGFRα | 23 |

| FIP1L1-PDGFRα T674I | n/a |

| PDGFRα D842V | n/a |

. | IC50, nM . |

|---|---|

| MSCV-GFP | n/a |

| FIP1L1-PDGFRα | 23 |

| FIP1L1-PDGFRα T674I | n/a |

| PDGFRα D842V | n/a |

IC50 = AMN 107 concentration resulting in 50% growth inhibition of Ba/F3 cells stably transduced with the constructs listed.

n/a indicates that 50% inhibition of cell growth was not achieved at the highest drug concentration tested.

The T674I mutation in PDGFRβ corresponds to the imatinib mesylate resistance mutation T315I in BCR-ABL. We previously demonstrated that this mutation in the context of FIP1L1-PDGFRα confers imatinib mesylate resistance.7 In this study, the FIP1L1-PDGFRα T674I mutation appeared to be resistant to AMN107 at concentrations up to 1 μM (Figure 3A; Table 3). FIP1L1-PDGFRα T674I phosphorylation and Stat5 phosphorylation were also maintained in the presence of AMN107 at concentrations up to 200 nM (Figure 3B-C). In addition, we tested the response to AMN107 of an activating point mutation D842V in the context of wild-type PDGFRα. This mutation in PDGFRα has been identified in patients with imatinib mesylate–resistant GIST and was shown to cause imatinib mesylate resistance in vitro in a Ba/F3 assay (IC50 ∼ 1-2 μM).27,34 Ba/F3 cells expressing PDGFRβ D842V were resistant to AMN107, because growth was not inhibited at concentrations up to 1 μM (Figure 3A; Table 3).

AMN107 is effective for treatment of myeloproliferative disease induced by TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα in a murine BMT assay

To test the effects of AMN107 in vivo, we used a murine bone marrow transplantation (BMT) protocol to model myeloproliferative disease caused by TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFα. As previously described,25,35 retroviral transduction of these fusion kinases into bone marrow cells of 5-flourouracil–treated donor mice, followed by transplantation into lethally irradiated recipients, produces a rapidly fatal myeloproliferative phenotype characterized by leukocytosis with myeloid predominance, splenomegaly, and extramedullary hematopoiesis.

In this study, donor bone marrow cells were transduced with a murine retroviral vector expressing TEL-PDGFRβ or FIP1L1-PDGFRα and transplanted into recipients. Mice that received a transplant with TEL-PDGFRβ– or FIP1L1-PDGFRα–transduced bone marrow were divided into 2 groups that were treated with daily oral gavage of placebo or AMN107. AMN107 was dosed at 75 mg/kg/d, starting at day 11 after transplantation. This dose was previously shown to be effective against a BMT model of BCR-ABL disease in mice.11

The TEL-PDGFRβ placebo group developed a completely penetrant myeloproliferative disease with a median latency of 17 days (Figure 4A); all placebo-treated animals were killed because of disease progression by day 18. In contrast, all animals in the TEL-PDGFRβ AMN107-treated group were still alive at the previously defined study end point of 7 days past the time of the killing of placebo-treated animals, and there was a statistically significant prolongation of survival in the AMN107 group (26 days; P < .001) (Figure 4A). Compared with placebo-treated animals, AMN107-treated animals also had statistically significant reductions in total white blood cells (WBCs; 563.7 × 109 cells/L for placebo versus 18.6 × 109 cells/L for AMN107; P < .05) and spleen weight (802.5 mg for placebo versus 350.0 mg for AMN107; P < .01) (Table 4).

Effects of AMN107 on characteristics of TEL-PDGFRβ- and FIP1L1-PDGFRα-induced myeloproliferative disease

. | TEL-PDGFRβ Placebo . | TEL-PDGFRβ AMN107 . | FIP1L1-PDGFRα Placebo . | FIP1L1-PDGFRα AMN107 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC, × 109/L | ||||

| Mean | 563.7 | 18.6 | 569.7 | 5.6 |

| Standard deviation | 96.0 | 8.8 | 88.2 | 2.3 |

| Median | 583.4 | 15.9 | 613.2 | 4.7 |

| Range | 459.3–648.3 | 10.9–33.5 | 452.8–659.2 | 4.0–9.6 |

| n | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Spleen weight, mg | ||||

| Mean | 802.5 | 350.0 | 731.8 | 88.0 |

| Standard deviation | 214.8 | 89.0 | 120.0 | 21.7 |

| Median | 800 | 340 | 700 | 100 |

| Range | 380–1130 | 250–470 | 575–880 | 50–100 |

| n | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 |

| Liver weight, mg | ||||

| Mean | 1746.3 | 1492.5 | 1666.4 | 1128.0 |

| Standard deviation | 546.9 | 103.3 | 135.5 | 90.9 |

| Median | 1910 | 1535 | 1596 | 1090 |

| Range | 590–2410 | 1320–1590 | 1550–1830 | 1080–1290 |

| n | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 |

. | TEL-PDGFRβ Placebo . | TEL-PDGFRβ AMN107 . | FIP1L1-PDGFRα Placebo . | FIP1L1-PDGFRα AMN107 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC, × 109/L | ||||

| Mean | 563.7 | 18.6 | 569.7 | 5.6 |

| Standard deviation | 96.0 | 8.8 | 88.2 | 2.3 |

| Median | 583.4 | 15.9 | 613.2 | 4.7 |

| Range | 459.3–648.3 | 10.9–33.5 | 452.8–659.2 | 4.0–9.6 |

| n | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Spleen weight, mg | ||||

| Mean | 802.5 | 350.0 | 731.8 | 88.0 |

| Standard deviation | 214.8 | 89.0 | 120.0 | 21.7 |

| Median | 800 | 340 | 700 | 100 |

| Range | 380–1130 | 250–470 | 575–880 | 50–100 |

| n | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 |

| Liver weight, mg | ||||

| Mean | 1746.3 | 1492.5 | 1666.4 | 1128.0 |

| Standard deviation | 546.9 | 103.3 | 135.5 | 90.9 |

| Median | 1910 | 1535 | 1596 | 1090 |

| Range | 590–2410 | 1320–1590 | 1550–1830 | 1080–1290 |

| n | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 |

Histopathology of hematopoietic organs from placebo mice with TEL-PDGFRβ–induced disease demonstrated a massive infiltration of maturing myeloid forms which completely effaced normal splenic architecture (Figure 5A). Further examination demonstrated markedly hypercellular bone marrow with a complete predominance of maturing myeloid forms. Extramedullary hematopoiesis was observed in the liver and marked leukocytosis in the peripheral blood as previously reported36 (Figure 5A and data not shown). Histopathologic examination of organs from the TEL-PDGFRβ AMN107-treated mice showed a significantly less severe myeloproliferative disease than their placebo-treated counter-parts, although features of myeloid expansion were still present. Although splenic architecture of the TEL-PDFGRβ AMN107-treated animals was perturbed, there was a relative preservation of splenic red and white pulp in comparison with spleens from the placebo-treated group (Figure 5A). Further analysis of spleens from AMN107-treated animals also demonstrated that splenic red pulp appeared to be expanded by an admixture of both maturing myeloid forms and erythroid elements in contrast to the predominantly myeloid population observed in placebo-treated animals (Figure 5A, inset). Similar changes were also noted in the bone marrow of AMN107-treated animals, which, despite being hypercellular, displayed an admixture of both myeloid and erythroid elements versus the completely myeloid predominant bone marrow of the placebo-treated group (Figure 5A). Finally, the significantly reduced tumor burden of TEL-PDGFRβ AMN107-treated animals was also reflected in liver sections from these animals which displayed only focal patches of extramedullary hematopoiesis compared with the extensive liver involvement observed in the placebo-treated animals (Figure 5A).

Histopathology of AMN107-treated and placebo-treated mice. Histopathology of representative mice that received a transplant with bone marrow transduced with either (A) TEL-PDGFRβ or (B) FIP1L1-PDGFRα. Panels show spleen (× 100 and × 600; hematoxylin and eosin [H&E]), bone marrow (× 600; H&E), and liver (× 600; H&E) of placebo- and AMN107-treated mice at time of killing or trial end point. TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα placebo-treated animals show complete effacement of normal splenic architecture (× 100) by a marked expansion of maturing myeloid elements, many with folded or ring-like nuclei (inset, × 600) and also seen in bone marrow and liver. Efficacy of AMN107 is demonstrated, in part, by a significant reduction in infiltrating myeloid forms in liver sections from both TEL-PDGFRβ– and FIP1L1-PDGFRα–transduced animals (see text for additional details).

Histopathology of AMN107-treated and placebo-treated mice. Histopathology of representative mice that received a transplant with bone marrow transduced with either (A) TEL-PDGFRβ or (B) FIP1L1-PDGFRα. Panels show spleen (× 100 and × 600; hematoxylin and eosin [H&E]), bone marrow (× 600; H&E), and liver (× 600; H&E) of placebo- and AMN107-treated mice at time of killing or trial end point. TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα placebo-treated animals show complete effacement of normal splenic architecture (× 100) by a marked expansion of maturing myeloid elements, many with folded or ring-like nuclei (inset, × 600) and also seen in bone marrow and liver. Efficacy of AMN107 is demonstrated, in part, by a significant reduction in infiltrating myeloid forms in liver sections from both TEL-PDGFRβ– and FIP1L1-PDGFRα–transduced animals (see text for additional details).

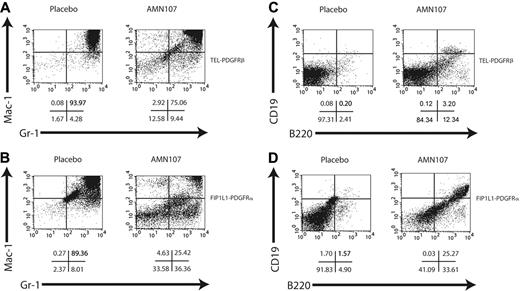

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of spleen (Figure 6A,C) of TEL-PDGFRβ placebo-treated animals showed a marked increase in Gr-1+/Mac-1+ cells and a decrease in B-lymphoid cells (B220+, CD19+) compared with normal spleen. In corroboration with the histopathologic findings, AMN107-treated animals showed a similar pattern of myeloproliferation, but with a consistently reduced percentage of Gr-1+/Mac-1+ cells and a slightly increased percentage of B220+/CD19+ cells compared with the placebo group (Figure 6A,C).

In the FIP1L1-PDGFRα bone marrow transplantation experiment, even more dramatic differences between placebo and AMN107 groups were observed. Placebo-treated animals rapidly developed a fatal myeloproliferative disease similar to that previously described for FIP1L1-PDGFRα.35 Whereas all placebo animals were lost to disease by day 24, all AMN107-treated animals remained alive and healthy until day 33 when the study was terminated (Figure 4B); the difference in survival was statistically significant (P < .001). Compared with placebo, AMN107 treatment was correlated with significant reductions in total WBCs (569.7 × 109 cells/L for placebo versus 5.6 × 109 cells/L for AMN107; P < .01) and spleen weight (731.8 mg for placebo versus 88.0 mg for AMN107, P < .01) (Table 4).

Consistent with previous results, histopathologic (Figure 5B) and FACS analysis (Figure 6B,D) revealed evidence of severe myeloproliferative disease in FIP1L1-PDGFRα placebo-treated animals, as demonstrated by a massive infiltration of maturing myeloid elements in the spleens and bone marrows, as well as extensive degrees of extramedullary hematopoiesis in the livers, of the placebo-treated group. In contrast, examination of hematopoietic organs from AMN107-treated animals displayed a striking preservation of normal splenic architecture with substantially reduced amounts of maturing myeloid elements in the red pulp (Figure 5B); this was corroborated by flow cytometric analyses of splenocytes derived from these animals (Figure 6B,D). Bone marrow sections from AMN107-treated animals also showed dramatic improvement over placebo-treated animals and were less cellular with the reappearance of fat spaces and more normal ratios of myeloid to erythroid elements. Finally, the efficacy of AMN107 in these drug-treated animals was demonstrated by the notable absence of any extramedullary hematopoiesis in their livers (Figure 5B).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that AMN107 can effectively treat myeloproliferative disease caused by TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα in a murine bone marrow transplantation model. The effects of AMN107 were somewhat more significant in FIP1L1-PDGFRα disease, because the reductions in spleen weights and improvement in histopathologic and FACS profiles in the AMN107-treated group were more dramatic than in TEL-PDGFRβ disease. However, our data demonstrate that AMN107 can inhibit transformation by TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα both in vitro and in vivo and suggest that this novel inhibitor may represent a viable option for targeted therapy of human malignancies associated with these fusion kinases.

Flow cytometric analysis of spleen of AMN107- and placebo-treated mice. Flow cytometry of spleen cells from mice with TEL-PDGFRβ (A,C) or FIP1L1-PDGFRα (B,D) disease treated with placebo (left) or AMN107 (right). Cells were stained with Gr-1 and Mac-1 for myeloid cells (A-B) or B220 and CD19 for B lymphoid cells (C-D). A total of 10 000 events were recorded from the population of cells that was both viable (based on forward and side scatter and on absence of 7AAD staining) and GFP+. Representative dot plots from 1 of 2 mice analyzed are shown; below the plots are the percentages of cells in each quadrant.

Flow cytometric analysis of spleen of AMN107- and placebo-treated mice. Flow cytometry of spleen cells from mice with TEL-PDGFRβ (A,C) or FIP1L1-PDGFRα (B,D) disease treated with placebo (left) or AMN107 (right). Cells were stained with Gr-1 and Mac-1 for myeloid cells (A-B) or B220 and CD19 for B lymphoid cells (C-D). A total of 10 000 events were recorded from the population of cells that was both viable (based on forward and side scatter and on absence of 7AAD staining) and GFP+. Representative dot plots from 1 of 2 mice analyzed are shown; below the plots are the percentages of cells in each quadrant.

Discussion

The development of novel small molecule kinase inhibitors is important because of the frequency of aberrant kinase activity in human malignancies and the incidence of drug resistance that may render some patients insensitive to specific inhibitors. AMN107 is one such novel inhibitor that has been shown to potently inhibit BCR-ABL, as well as imatinib mesylate–resistant mutants of BCR-ABL, making it an attractive alternative to imatinib mesylate and a possible means of circumventing resistance.10,11 Furthermore, AMN107 has a different selectivity profile toward ABL, PDGFRβ, and KIT kinases compared with imatinib mesylate, which may prove advantageous in certain clinical settings.

In this study we have shown that AMN107 is active in vitro against the clinically relevant fusion kinases TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα, which are associated with the myeloproliferative diseases CMML and HES, respectively. We observed that AMN107 effectively inhibits growth of Ba/F3 cells transformed by both fusion kinases and can inhibit phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in these fusion kinases as well as activation of their downstream signaling targets.

Furthermore, we have shown that AMN107 is an effective treatment for myeloproliferative disease caused by these fusion kinases in a murine bone marrow transplantation model. For both fusion kinases, AMN107 treatment resulted in a significant increase in survival compared with placebo animals, as well as significant reductions in total white blood cell count and spleen weights. The phenotype of the myeloid disease was also less severe in AMN107-treated animals than in placebo animals, as assessed by histopathology and FACS analysis.

We observed some differences in the efficacy of AMN107 treatment of myeloproliferative diseases induced by TEL-PDGFRβ versus FIP1L1-PDGFRα. AMN107 appears somewhat more effective in vivo against disease induced by FIP1L1-PDGFRα than by TEL-PDGFRβ, as assessed by differences in spleen weights and histopathologic and flow cytometric analyses. This may reflect differences in the sensitivity of TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα fusion kinases to inhibition by AMN107, or differences in pathogenesis or severity of the myeloproliferative diseases caused by TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα in the bone marrow transplantation model.

A major goal of developing novel inhibitors is to be able to circumvent resistance and/or to be able to combine drugs with different resistance profiles to prevent the acquisition of resistance. In this study, we showed that AMN107 was also effective in vitro against an imatinib mesylate–resistant T681I mutation in TEL-PDGFRβ. This residue corresponds to T315I in BCR-ABL, a mutation that confers imatinib mesylate resistance in patients which is notoriously difficult to inhibit. Interestingly, in the context of FIP1L1-PDGFRα, the corresponding residue T674I showed resistance to AMN107. This might be due to structural differences between PDGFRβ and PDGFRα; further structural studies of these receptor tyrosine kinases are warranted to understand the basis for variable sensitivity of these homologous mutants to AMN107. AMN107 was also tested for activity against an activating point mutation in PDGFRα, D842V, which has been reported in patients with imatinib mesylate–resistant GIST. This mutant also proved to be completely resistant to AMN107 inhibition in vitro, demonstrating that clinically relevant resistance mutations can hinder the effectiveness of novel kinase inhibitors and underscoring the need for continued development of next-generation inhibitors.

Several novel small molecule kinase inhibitors have already been shown to have activity against TEL-PDGFRβ, FIP1L1-PDGFRα, and/or the wild-type PDGFRα and PDGFRβ kinases. PKC412 inhibits FIP1L1-PDGFRα (and imatinib mesylate resistance mutant T674I) in vitro and in a BMT model35 and also inhibits both TEL-PDGFRβ and TEL-PDGFRβ T681I in vitro.18 SU11657 inhibits TEL-PDGFRβ activity in vitro and can effectively treat TEL-PDGFRβ–mediated myeloproliferative disease in a BMT model.37 Several other kinase inhibitors have been shown to reduce kinase activity of PDGFRβ and/or PDGFRβ in vitro, including BMS354825, a novel dual Src/Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor31 ; MLN518, an inhibitor initially used against activated FLT338 ; and others.39

Investigation of synergy between multiple kinase inhibitors could help to determine whether combination therapy may be able to surmount resistance. The spectrum of potential mutations in PDGFRβ and PDGFRα conferring resistance to AMN107 and other compounds could be identified by screening mutagenesis strategies,13,40 or by testing candidate resistance mutations based on homology with sites of resistance to other small molecule kinase inhibitors in receptor tyrosine kinases.35,40 Such studies may have important translational implications for identifying and overcoming clinically problematic resistance mutations in patients.

Despite the challenge of resistance mutations, in vitro evidence of TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα kinase inhibition by AMN107, coupled with the prolongation of survival and reduction in disease burden in AMN107-treated mice with TEL-PDGFRβ or FIP1L1-PDGFRα myeloproliferative disease, suggests that this drug may be a treatment alternative in patients who are not responsive to, or cannot tolerate, imatinib mesylate. Clinical studies will be necessary to further investigate this possibility. AMN107 is orally available and is currently being tested in phase 2 clinical trials in BCR-ABL–positive CML and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

In summary, we have shown that a novel small molecule kinase inhibitor, AMN107, is effective in vitro and in vivo against TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα fusion tyrosine kinases. AMN107 could therefore potentially serve as an effective therapy in myeloproliferative diseases caused by TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα, and possibly other malignancies caused by activated versions of these kinases or related tyrosine kinases such as KIT.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 19, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1932.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health grant T32GM07753-24 (E.H.S.) and grants DK50654 and CA66996 (D.G.G.), and by the Belgian Federation against Cancer (J. Cools) and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. J. Chen is a fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. B.H.L. is a recipient of a Physician-Scientist Fellowship from the Leukemia Research Foundation.

Several of the authors (D.F. and P.W.M.) are employed by a company, Novartis, whose product, AMN107, was studied in the present work. One author (J.D.G.) has declared a financial interest in a company, Novartis, whose product, AMN107, was studied in the present work.

E.H.S., J. Chen, and B.H.L designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. J. Cools contributed critical reagents and assisted in experimental design and writing of the paper. E.M., J.A., D.C., A.C., S.A.M., and R.O. participated in the in vivo experiments. D.F., P.W.M., and J.D.G. contributed critical reagents, assisted in the writing of the paper, and performed important prior work on pharmacologic studies of the compound. D.G.G. supervised the study, analyzed the data, and assisted in writing the paper.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We are grateful to members of the Gilliland laboratory for helpful discussion.

J. Cools is a postdoctoral researcher of the FWO-Vlaanderen. D.G.G. is a Doris Duke Foundation Distinguished Clinical Scientist and an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

![Figure 5. Histopathology of AMN107-treated and placebo-treated mice. Histopathology of representative mice that received a transplant with bone marrow transduced with either (A) TEL-PDGFRβ or (B) FIP1L1-PDGFRα. Panels show spleen (× 100 and × 600; hematoxylin and eosin [H&E]), bone marrow (× 600; H&E), and liver (× 600; H&E) of placebo- and AMN107-treated mice at time of killing or trial end point. TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1-PDGFRα placebo-treated animals show complete effacement of normal splenic architecture (× 100) by a marked expansion of maturing myeloid elements, many with folded or ring-like nuclei (inset, × 600) and also seen in bone marrow and liver. Efficacy of AMN107 is demonstrated, in part, by a significant reduction in infiltrating myeloid forms in liver sections from both TEL-PDGFRβ– and FIP1L1-PDGFRα–transduced animals (see text for additional details).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/106/9/10.1182_blood-2005-05-1932/6/m_zh80210586290005.jpeg?Expires=1769285936&Signature=BBPkXJblzZsjOkSSS410t~r2PxqhWWT-KX~yCfelFZuv9TxbE~Ic0f0QAN4hWf~35Hgod4uByHgtoOBGjt1lRd5NNKw6sVyh4BIWSAoJAEfNAFMc533TITV3L1~ZbfQFbjNWDdIO0c2qpTskHFPejihYtgg7oHz35SmvBQV8HxzbGPbXOAl3ASBDMevIS6zNRNpooaYim0lODb51s~R87zTI0NL9dVqfK0POADzazSWKa1bAblHx~db2xpbie1aDaXAEnwv5xprtvs1r~QTlzjLHihdCaBfvoVp2cEBtm6rtOjIjXp0ATSH8d3rKmuAQkfFXnM0KwZ-T198QLdYSlg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal