Key Points

Germline activating STAT3 mutations were detected in 3 patients with autoimmunity, hypogammaglobulinemia, and mycobacterial disease.

T-cell lymphoproliferation, deficiency of regulatory and helper 17 T cells, natural killer cells, dendritic cells, and eosinophils were common.

Abstract

The signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family of transcription factors orchestrate hematopoietic cell differentiation. Recently, mutations in STAT1, STAT5B, and STAT3 have been linked to development of immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked–like syndrome. Here, we immunologically characterized 3 patients with de novo activating mutations in the DNA binding or dimerization domains of STAT3 (p.K392R, p.M394T, and p.K658N, respectively). The patients displayed multiorgan autoimmunity, lymphoproliferation, and delayed-onset mycobacterial disease. Immunologically, we noted hypogammaglobulinemia with terminal B-cell maturation arrest, dendritic cell deficiency, peripheral eosinopenia, increased double-negative (CD4−CD8−) T cells, and decreased natural killer, T helper 17, and regulatory T-cell numbers. Notably, the patient harboring the K392R mutation developed T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia at age 14 years. Our results broaden the spectrum of phenotypes caused by activating STAT3 mutations, highlight the role of STAT3 in the development and differentiation of multiple immune cell lineages, and strengthen the link between the STAT family of transcription factors and autoimmunity.

Introduction

Primary immunodeficiency syndromes are a heterogeneous group of diseases with variable manifestations, including autoimmunity. The most characteristic early-onset autoimmunity syndrome is immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked (IPEX) syndrome, which leads to fatal autoimmunity unless treated with stem cell transplantation. IPEX is associated with recessive mutations in FOXP3, encoding a transcription factor essential for regulatory T-cell (Treg) development.1 Other genetic causes include mutations in CD25, STAT1, STAT5B, and ITCH.2-4

The signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) transcription factors are widely expressed in hematological and other cell types, and mutations causing either gain or loss of STAT activity have been associated with primary immunodeficiency syndromes.2,5-8 The cytokine receptor–Janus kinase–STAT pathway has an important role in the regulation of the immune system, and different STAT family members have been ascribed specific roles in determining T-cell differentiation in response to certain cytokines. Generally, T helper 1 (Th1) cell differentiation is mediated by the interferon-γ (IFN-γ)–STAT1 and interleukin-12 (IL-12)–STAT4 axis, Th2 differentiation by the IL-4–STAT6 axis, Th17 by the IL-6–STAT3 axis, and commitment to Treg pathway by the IL-2–STAT5 axis.9,10 Consequently, mutations in STAT genes lead to variable clinical presentations, ranging from susceptibility to viral infections and mycobacterial disease to multiorgan autoimmunity.2,5-8 As an example, dominant-negative germline mutations in STAT3 cause hyperimmunoglobulin E (IgE) syndrome (HIES),5,6 whereas recently discovered somatic activating STAT3 mutations have been found in 40% to 70% cases of large granular lymphocytic (LGL) leukemia, a neoplastic disease accompanied by autoimmune manifestations such as rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmune cytopenias.11-13

We evaluated 3 patients who carried germline heterozygous activating STAT3 mutations, 2 of which were recently published as part of a larger cohort featuring 5 STAT3 gain-of-function patients.14 The 2 patients presented with aggressive multiorgan autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation, including pediatric LGL leukemia. The third patient first described here had late-onset autoimmune manifestations and developed disseminated mycobacterial disease in late adolescence. Immunologically, we noted hypogammaglobulinemia with terminal B-cell maturation arrest, dendritic cell deficiency, peripheral eosinopenia, increased double-negative (CD4−CD8−) T cells, and low natural killer (NK), Th17, and regulatory T-cell counts.

Methods

Study patients

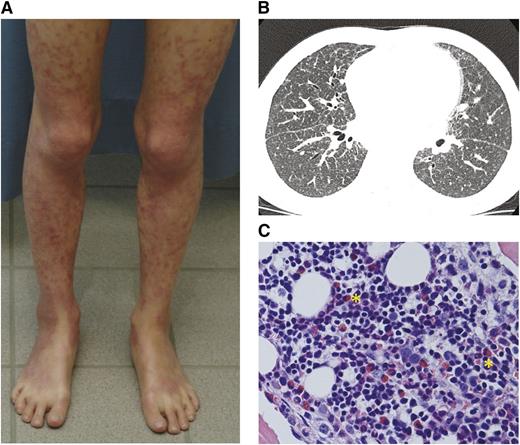

We evaluated 2 patients characterized by early-onset autoimmunity and growth failure previously published as part of a larger autoimmunity cohort14 and 1 with delayed-onset disseminated nontuberculous mycobacteriosis (Table 1; Figure 1; detailed case descriptions are in the supplemental Appendix on the Blood Web site). Patient 1 is a 17-year-old female born full term without complications. She was first brought to medical attention at 12 months of age for diarrhea and abdominal pain caused by autoimmune enteropathy. At the age of 2, she developed generalized, livedo-like exfoliating dermatitis (Figure 1). At age 6, marked and progressive lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly were noted, with lymph node biopsy showing polyclonal CD4+ T-cell expansion. At age 10, she suffered from sicca and was diagnosed with bilateral posterior uveitis with cystic macular edema that has since led to severe visual impairment. She also experienced recurrent autoinflammatory episodes with high fever, sterile pleuritis, and serositis with concomitant rise in inflammatory markers. Her growth was retarded and alternated between −2 standard deviations (SD) to −4 SD. Because of recurrent upper respiratory tract infections since birth, multiple tympanostomies and functional endoscopic sinus surgery were performed at age 11. From early school age, the patient has suffered from reversible bronchoconstriction and, at age 12, high-resolution computed tomography showed moderate bronchiectasis. Immunoglobulin replacement therapy was then introduced to treat mild unspecific hypogammaglobulinemia with positive response in her rate of infections. Recently, the patient developed rapidly worsening cryptogenic organizing pneumonia requiring invasive ventilation and high-dose steroids. At the time of sampling, she was using systemic tacrolimus and corticosteroid medication and was on intravenous immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

Clinical characteristics of patients. (A) Livedo-like generalized exfoliating dermatitis in patient 1. The rash culminates in limb extensor areas. (B) High-resolution computed tomography of patient 2 showing ground-glass opacity, bronchoalveolar thickening, and increased nodularity. (C) BM biopsy from patient 1 showing modest BM eosinophilia despite observed peripheral eosinopenia (yellow asterisks). Hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×40.

Clinical characteristics of patients. (A) Livedo-like generalized exfoliating dermatitis in patient 1. The rash culminates in limb extensor areas. (B) High-resolution computed tomography of patient 2 showing ground-glass opacity, bronchoalveolar thickening, and increased nodularity. (C) BM biopsy from patient 1 showing modest BM eosinophilia despite observed peripheral eosinopenia (yellow asterisks). Hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×40.

Patient 2 is a 15-year-old female who was born small for gestational age at week 34 (1380 g/40.5 cm/30.5 cm, −5 SD). At birth, she was diagnosed with neonatal diabetes mellitus with extremely high insulin, glutamate decarboxylase, and islet cell autoantibodies.15 The patient suffered from multiple early-onset allergies. Despite initial height catch-up, worsening idiopathic growth failure with gradual deterioration to −7 SD was noted. At age 12 months, she was diagnosed with celiac disease. The pancreas was rudimentary in the abdominal magnetic resonance imaging scan. She developed desquamative interstitial pneumonitis in infancy that later progressed to pulmonary fibrosis. At school age, she suffered from recurrent pneumonias. Gradually worsening and severe unspecific hypogammaglobulinemia was noted, leading to immunoglobulin replacement therapy at age 12. At age 14, the patient developed megaloblastic anemia (mean corpuscular volume 101, hemoglobin 6.0 g/L) with clonal T-cell LGL proliferation and was subsequently diagnosed with T-cell LGL leukemia. Recently, she developed relapsing thrombosis of the right internal carotid artery and suspected vasculopathy. She is currently dependent on weekly red blood cell transfusions. At the time of sampling, she was using systemic tacrolimus, high-dose steroids, and mycophenolate mofetil and was on intravenous immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

Patient 3 is a 22-year-old female with normal growth and development. Reactions to vaccinations, including the bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccination, were normal. In early childhood, she had several ear infections leading to tympanostomy and adenotomy. At the age of 17, the patient presented with prolonged diarrhea and abdominal pain caused by lymphocytic colitis, which was successfully treated with peroral budesonide and loperamide. She also experienced episodes of marked immune thrombocytopenia and has reported swelling and stiffness in her small joints. At 19, the patient developed persistent fever from Mycobacterium avium pneumonia and was also diagnosed with antibody deficiency. The patient received immunoglobulin replacement therapy and standard treatment of mycobacterial infection with good response. At age 21, the patient developed fistulating cervical lymphadenitis with concomitant mediastinal and axillar lymphadenopathy. M. avium was found in a lymph node biopsy, bone marrow (BM), and feces. The patient is currently being treated with a combination of clarithromycin, ethambutol, and levofloxacin as well as intravenous immunoglobulin. At the time of sampling, no immunomodulatory drugs were being used.

This study was conducted in accordance to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Helsinki University Central Hospital Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and healthy controls.

DNA and RNA extraction and selection of γδ T cells

Genomic DNA was extracted from freshly sorted T-cell fractions, EDTA blood samples, or salivary samples using the Qiagen FlexiGene DNA kit (Qiagen), Gentran puregene kit (Qiagen), or OraGene DNA Self-Collection Kit (OGR-250, DNA Genonek). RNA was extracted from heparin blood samples with the Qiagen miRNeasy kit (Qiagen). The CD3+γδ+ cell fraction (patient 2) was sorted from fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells by flow cytometry using antibodies against CD3, CD8, CD3, T-cell receptor-αβ (TCR-αβ), and TCR-B-γδ (BD Biosciences).

Exome sequencing from whole blood, saliva, and γδ T-cell fractions and validation of candidate mutations

Whole exome sequencing was performed at the Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland sequencing core facility, Science for Life laboratory Stockholm, and University of Exeter according to established laboratory protocols. The read mapping, variant calling, and filtering steps for somatic and germline variants were performed as described previously.12,16 The candidate mutations were verified by capillary sequencing from blood and salivary DNA samples. The primers are listed in supplemental Table 1.

STAT3 luciferase reporter assay and analysis of Y705-pSTAT3 in transiently transfected cells

The K658N, K392R, and M394T mutations were introduced into wild-type (WT) STAT3 sequence in pDEST40 vector using the Phusion Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Thermo Scientific) (primer sequences are shown in supplemental Table 1). The STAT3 luciferase reporter assay and pSTAT3Y705 western blotting were performed as previously described.12 Briefly, HEK293 cells stably expressing a STAT3-responsive firefly luciferase reporter were plated onto 96-well plates at 15 000 cells/well and, 6 hours after plating, transfected with empty, WT, or mutant STAT3 plasmids. The following day, the cells were starved for 3 hours and subsequently mock-treated or stimulated with IL-6 for 3 hours. The luciferase activity was measured with the One-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Equal plasmid transfection and STAT3 phosphorylation were assessed by western blotting using parallel-derived whole cell lysates. Mouse anti-STAT3 (9139, Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1000), polyclonal rabbit anti-human pSTAT3Y705 (9131, Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1000), and mouse anti–α-tubulin (T902, Sigma-Aldrich; 1:1000) were used as primary antibodies. Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit IRDye 800 (Li-cor Odyssey 926-32211; 1:1:15.000) and goat anti-mouse IRDye 680 (Li-cor Odyssey 926-32220; 1:1:15.000). Statistical significance was calculated using 2-way analysis of variance.

Immunophenotyping of T-, B-, and NK-cell subsets and peripheral blood Y705-pSTAT3 analysis

Fresh EDTA blood samples or peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures (PBMNCs) were used for B- and T-lymphocyte immunophenotyping using a 4- or 6-color flow cytometry panel with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against the surface antigens IgM, IgD, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD16/56, CD19, CD21, CD27, CD33, CD34, CD38, CD45, CD56, CD57, CD133, HLA-DR, CD62L, CD45RA, CD45RO, and Ki-67 (BD Biosciences).17 The memory status of T cells was studied with the antibody panel including anti-CD45 (clone 2D1), anti-CD3 (SK7), anti-CD4 (SK3), anti-CD45RA (GB11), and anti-CCR7 (150503) (R&D Systems).17 Phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3Y705) expression was assessed using Y705-pSTAT3-PeCF594 (catalog no. 562673, BD Biosciences). For Treg analysis, anti–CD4-PerCP (BD345770), anti–CD25-APC (BD555434), and anti–CD127-PE (BD557938) mAbs (BD Biosciences) were used for surface staining and FOXP3 Alexa fluor 488 mAbs (320112, BioLegend) for intracellular staining (eBioscience).

For phenotyping of IL-17–positive Th17 cells, fresh PBMNCs were stimulated for 16 hours with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads (Life Technologies) in the presence of Brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich). Thereafter, the cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-CD4 (Alexa Fluor 488 BD557695), CD69-APC (BD555533), and IL-17A-PE (BD560486) (BD Biosciences). Samples from patients 2 and 3 were additionally stained with CD161-APC-Cy7 (BD557756) (BD Biosciences). Samples were analyzed with FACSAria II or FACSCanto II flow cytometer and FACSDiva (BD Biosciences) or FlowJo software (TreeStar Inc).

Evaluation of Treg suppressor capacity and NK and CD3+CD8−–mediated cell cytotoxicity

CD4+CD25+CD127− Treg cells were sorted from whole blood using Human CD4+ T Cell Enrichment Cocktail (Stemcell Technologies) and fluorescence-activated cell sorting with mAbs against CD4-PerCP (BD345770), CD25-APC (BD555434), and CD127-PE (BD557938) (BD Biosciences). The cells were incubated for 6 days with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester–labeled autologous responder T cells in ratios of 1:0.5, 1:1, and 1:2 for patient 1 and in a ratio of 1:2 for patients 2 and 3. Anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads (Life Technologies) were used as stimulus. CD4+ cells were analyzed using FACSAria II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The suppression percentage was calculated with the following formula: 100 − ([% proliferation in presence of Treg/% proliferation in absence of Treg] × 100).18

Evaluation of T- and NK-cell responses is described in detail elsewhere.17,19 For the assessment of T-cell activation and degranulation, fresh mononuclear cells were stimulated for 6 hours with anti-CD3, anti-CD28, and anti-CD49d (BD Biosciences). For NK cell degranulation, cytokine and cytotoxicity assays, fresh mononuclear cells or fluorescence-activated cell–sorted CD3−CD16/56+ NK cells were stimulated with K562 target cells for 6 hours. The cells were analyzed using a 4- or 6-color flow cytometry panel with mAbs against the antigens CD45, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD16, CD56, CD45, CD45RA, TCR-γ, CCR7, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF). Additionally, standard 4-hour chromium 51 (51Cr)-release assays were performed according to established protocols for clinical samples using magnetic bead–separated CD3+CD8+ T-cell or CD3−CD56+ NK-cell subsets.19,20

Cytokine production

Whole blood was diluted 1:5 with RPMI into 96-well plates and activated by single stimulation or costimulations as indicated with IL-12 (20 ng/mL; R&D Systems; Abingdon), phytohemagglutinin (10 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (1 μg/mL; List Biochemicals), IFN-y (2 × 10 exp IU/mL; Immukin, Boehringer Ingelheim), IL-18 (20 ng/mL; R&D Systems; Abingdon), bacillus Calmette–Guérin (SSI; 3.4 × 10 exp 4/well), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (10 ng/mL, Sigma), and ionomycin (1 μg/mL; Sigma). Supernatants were taken at 24 hours. Cytokines were measured using standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (IFN-y; Pelikine, Sanquin, NL), or multiplexed particle-based flow cytometry (TNF-α, IL-12, IL-10, IL-6, IL-17; R+D Systems Fluorokinemap) on a Luminex analyzer (Bio-Plex, Bio-rad, UK).

For evaluation of IFN-γ signaling in monocytes, PBMNCs were plated in flat-bottomed 96-well plates (Costar Corning #3596) at 0.5 × 106 cells/well and stimulated with IFN-γ (0.01 ng/mL-150 ng/mL; Immunotools) for 60 minutes. PBMNCs were thereafter fixed, permeabilized, and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate–anti-CD14 (11-0149) and phycoerythrin–anti-pSTAT1 (12-9008) antibodies according to manufacturer’s protocol (eBioScience). STAT1 phosphorylation was determined in CD14+ monocytes using flow cytometry. To assess Toll-like receptor signaling in monocytes, PBMNCs were stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS (Sigma Aldrich) or left unstimulated for 60 minutes. l-selectin shedding was determined from CD14+ monocytes by flow cytometry with antibodies against anti-phycoerythrin–anti-CD62L (12-9008) and fluorescein isothiocyanate–anti-CD14 (11-0149). Flow cytometry was performed with Accuri cytometer and the manufacturer’s software (Becton Dickinson).

Anti-cytokine serology was performed by multiplexed particle-based flow cytometry as previously described.21 Serum IgG antibodies to the following cytokines were investigated: IFN-γ, TNF, IL-12, IL-23, IFN-α, IFN-ω, IL-6, IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22, and granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor.

Immunohistochemical staining of phospho-STAT3 and cleaved caspase-3

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of BM biopsy paraffin sections was performed according to standard techniques using pSTAT3Y705 mAb (1:100; 9145S, Cell Signaling Technology) and cleaved caspase-3 mAB (1:300; Cell Signaling Technology). BM biopsy slides from 3 healthy individuals were used as controls.

Results

Gain-of-function STAT3 mutations are associated with multisystemic autoimmunity and mycobacterial disease

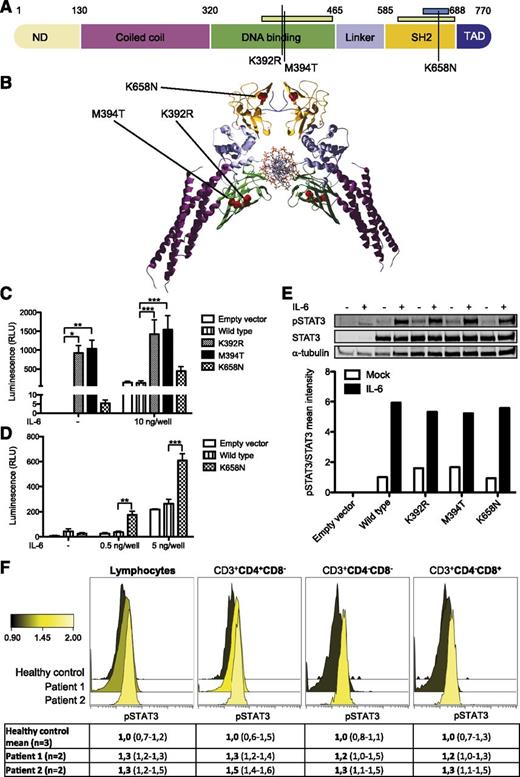

Patients 1 and 2 were recently shown to carry heterozygous, activating mutations in STAT3.14 The mutations (p.K658N at chr17:40474427 C>G and p.K392R at chr17:40481630 T>C) localized to the STAT3 Src-like homolog 2 and DNA-binding domains (Figure 2A-B). Exome sequencing was used to identify a novel de novo missense STAT3 mutation at position chr17:40481624 A>G resulting in methionine-to-threonine substitution at position 394 (M394T) in the STAT3 DNA-binding domain in patient 3. To compare the functional effect of these mutations, we transiently transfected the HEK293 cell line stably expressing luciferase under a STAT3-specific site promoter with constructs encoding WT or mutated STAT3. For K392R and M394T mutations, we observed STAT3 transcriptional activation under basal conditions, suggesting that these mutants are constitutively active (Figure 2C). In the K658N mutant, there was no transcriptional activity under basal conditions, but the mutant showed higher STAT3 transcriptional activation to low IL-6 concentrations than WT STAT3, the effect of saturating in higher concentrations (Figure 2D).

STAT3 mutations K658N, K392R, and M394T in studied patients. (A) Schematic representation of STAT3 protein domains with the observed mutations marked as black lines. Germ-line and somatic mutation hotspots for HIES5,6 and LGL leukemia11-13 are indicated as green and blue bars, respectively, at top. (B) Crystallographic structure of STAT3 dimer (RCSB Protein Data Bank code 1BG1). K658N, K392R, and M394T mutations are indicated as red dots. (C-D) HEK293 cells containing STAT3-responsive luciferase were transfected with empty, WT, and mutant STAT3 overexpression plasmids with or without IL-6 stimulation. K392R and M394T significantly increased STAT3 transcriptional activity in basal and stimulated conditions. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (n = 6; C). The K658N mutant showed hypersensitivity to IL-6 stimulation in low concentrations. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (n = 3; D). Two-way analysis of variance, *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001. (E) No significant increase in pSTAT3Y705 phosphorylation was observed when HEK293 cells were transfected with mutant STAT3-overexpression constructs. Equal amounts of parallel-derived whole cell lysates were loaded per condition. α-tubulin and STAT3 were used as loading and expression controls, respectively. +, presence of IL-6 stimulation; –, absence of IL-6 stimulation. (F) In peripheral blood, no significant increase in STAT3 phosphorylation was noted in studied patients. Color change indicates relative pSTAT3Y705 expression. Forward panel, K392R; middle panel, K658N; back panel, healthy control (n = 3, value range presented in parentheses).

STAT3 mutations K658N, K392R, and M394T in studied patients. (A) Schematic representation of STAT3 protein domains with the observed mutations marked as black lines. Germ-line and somatic mutation hotspots for HIES5,6 and LGL leukemia11-13 are indicated as green and blue bars, respectively, at top. (B) Crystallographic structure of STAT3 dimer (RCSB Protein Data Bank code 1BG1). K658N, K392R, and M394T mutations are indicated as red dots. (C-D) HEK293 cells containing STAT3-responsive luciferase were transfected with empty, WT, and mutant STAT3 overexpression plasmids with or without IL-6 stimulation. K392R and M394T significantly increased STAT3 transcriptional activity in basal and stimulated conditions. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (n = 6; C). The K658N mutant showed hypersensitivity to IL-6 stimulation in low concentrations. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (n = 3; D). Two-way analysis of variance, *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001. (E) No significant increase in pSTAT3Y705 phosphorylation was observed when HEK293 cells were transfected with mutant STAT3-overexpression constructs. Equal amounts of parallel-derived whole cell lysates were loaded per condition. α-tubulin and STAT3 were used as loading and expression controls, respectively. +, presence of IL-6 stimulation; –, absence of IL-6 stimulation. (F) In peripheral blood, no significant increase in STAT3 phosphorylation was noted in studied patients. Color change indicates relative pSTAT3Y705 expression. Forward panel, K392R; middle panel, K658N; back panel, healthy control (n = 3, value range presented in parentheses).

Effects of STAT3 mutations on STAT3 phosphorylation status

The phosphorylation of tyrosine residue 705 (pY705) of STAT3 is essential for the dimerization and activation of WT STAT3.22 To evaluate whether the observed STAT3 hyperactivity was dependent on increased STAT3 phosphorylation, we used parallel-derived whole cell lysates of the transiently transfected HEK293 cells to determine the level of pSTAT3Y705 protein by western blotting both at baseline and after IL-6 stimulation. Expression of mutant pSTAT3Y705 was similar to WT (Figure 2E). Additionally, we assessed the expression of pSTAT3Y705 from fresh whole blood samples by a fluorescence-activated cell sorted–based phosphoflow method (Figure 2F). The proportion of pSTAT3Y705-positive lymphocytes ranged between upper normal to slightly increased in the K392R- and K658N-mutated patients.

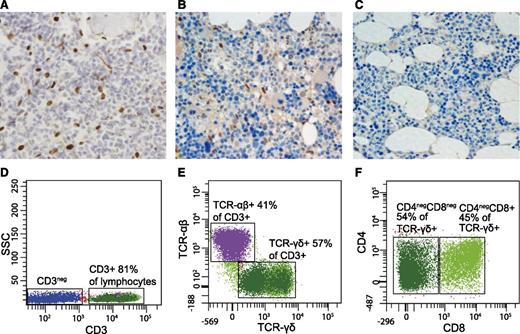

Additionally, BM biopsies from patients 1 (K658N) and 2 (K392R) were stained for pSTAT3Y705 IHC. In both cases, we observed increased number of pSTAT3Y705-positive cells (Figure 3A-C). Morphologically, the pSTAT3Y705-positive BM-infiltrating cells were classified as LGL. The number of pSTAT3Y705-positive lymphocytes was higher in the patient 2 carrying the K392R mutation, which could be related to the recently made T-cell LGL leukemia diagnosis (Figure 3A-B).

Abnormal lymphocyte populations detected in STAT3-mutated patients. (A-C) BM biopsy shows abnormally high number of phospho-STAT3–positive lymphocytes both in patient 2 (p.K392R) (A) and, to a lesser extent, in patient 1 (p.K658N) (B). Patient 3 (M394T) was not available for study. In healthy BM, no phospho-STAT3 cells are present (C). (D-F) Flow cytometry results from patient 2 (p. K392R). The majority of lymphocytes were CD3+ (A), with 57% of the population expressing TCR-γδ (B). The TCR-γδ+ population consisted of CD4−CD8− and CD4−CD8+ T cells. The expression of TCR-γδ was considerably lower in CD4−CD8− cells than in CD4−CD8+ T cells; therefore, 2 populations are seen in the scatter plot. (C). In healthy individuals, TCR-γδ–expressing T cells account less than 6% of all CD3+ T cells and the TCR-γδ expression is normally uniform. ×40 magnification, hematoxylin and eosin stain.

Abnormal lymphocyte populations detected in STAT3-mutated patients. (A-C) BM biopsy shows abnormally high number of phospho-STAT3–positive lymphocytes both in patient 2 (p.K392R) (A) and, to a lesser extent, in patient 1 (p.K658N) (B). Patient 3 (M394T) was not available for study. In healthy BM, no phospho-STAT3 cells are present (C). (D-F) Flow cytometry results from patient 2 (p. K392R). The majority of lymphocytes were CD3+ (A), with 57% of the population expressing TCR-γδ (B). The TCR-γδ+ population consisted of CD4−CD8− and CD4−CD8+ T cells. The expression of TCR-γδ was considerably lower in CD4−CD8− cells than in CD4−CD8+ T cells; therefore, 2 populations are seen in the scatter plot. (C). In healthy individuals, TCR-γδ–expressing T cells account less than 6% of all CD3+ T cells and the TCR-γδ expression is normally uniform. ×40 magnification, hematoxylin and eosin stain.

STAT3 hyperactivity is associated with peripheral eosinopenia, hypogammaglobulinemia, and deficiency of Treg, NK, and dendritic cells

The effects of the STAT3 mutations K392R, K658N, and M394T on the properties, phenotype, and functionality of hematopoietic cells were analyzed in detail using IHC and flow cytometry (Table 2; Figure 1C). In the myeloid lineage of patients 1 (K658N) and 2 (K392R), we observed marked peripheral eosinopenia with modest BM eosinophilia, suggesting an eosinophil mobilization defect. The BM biopsies from both patients were stained with cleaved caspase-3 antibody to detect increased eosinophil apoptosis, but the results were comparable to healthy controls (data not shown). We also noted plasmacytoid dendritic cell deficiency in all patients. The other cells of the myeloid lineage showed normal maturation in the BM and normal peripheral blood counts.

The results of the lymphoid lineage analysis are presented in Table 2. The patients had normal overall CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T- and CD19+ B-cell counts but low relative CD3–CD16+CD56+ NK-cell counts. In the more detailed analyses of cytotoxic lymphocyte subsets, the frequencies of early differentiated CD56bright and late differentiated CD57+ NK cells were normal. The patients’ NK cells expressed normal levels of cytotoxic granule constituents perforin, granzyme A, and granzyme B (data not shown). Moreover, NK-cell and cytotoxic CD3+CD8+CD57+ T-cell degranulation and target cell killing were also within normal range, as was IFN-γ and TNF production in response to engagement of immunoreceptor tyrosine–based activation motif –coupled activating receptors (data not shown). NK-cell killing of K562 target cells was also assessed and found to be within normal range (data not shown).

Over time, all patients developed unspecific hypogammaglobulinemia or antibody deficiency (Table 2). In B-cell subset analyses, the relative numbers of activated CD19+CD38lowCD21low B cells and CD19+CD21+ mature B cells were increased. Additionally, a rise in marginal zone–like CD19+CD27+IgD+IgM+ B cells with a corresponding decrease in CD19+CD27+IgD−IgM− switched memory B cells was observed. The patients were screened for autoantibodies against endocrine and exocrine organs as well as intracellular proteins (for a detailed account, see supplemental Table 2). Patient 1 had positive antithyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies without clinical thyroid disease. Patient 2 had high titer diabetes autoantibodies. All other autoantibody titers were negative.

In the T-cell compartment, we noticed a deficiency of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Treg cells in the IPEX-like patients 1 and 2 (Table 2). Also, the suppressive capacity of Treg cells was reduced (supplemental Figure 2). In patient 3, Treg cell counts and suppressive capacity were comparable to the controls. Surprisingly, the proportions of IL-17 producing CD4+CD69+ Th17 cells were also decreased in all patients. To confirm the finding, the production of IL-17 upon phytohemagglutinin stimulation was assessed by multiplexed particle–based flow cytometry in patient 3. This showed minimal response (supplemental Figure 5).

Intact cytokine production in M394T-mutated patient with mycobacterial disease

Patient 3 with the STAT3 M394T mutation developed disseminated mycobacterial disease in late adolescence. Because Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease generally involves defects in the IL-12/IFN-γ feedback loop,23 the pathway was extensively tested but found normal. IFN-γ receptor–STAT1 signaling was intact, because STAT1 phosphorylation and upregulation of HLA-DR expression followed normal dose-response curves after in vitro stimulation with IFN-γ (data not shown). There was normal LPS-induced shedding of l-selectin (CD62L), suggesting normal Toll-like receptor signaling (data not shown).

Release of IL-12, TNF, and IFN-γ was normal after stimulation of PBMNCs with T-cell specific antigens. Notably, upon stimulation of PBMNCs with IL-12 plus LPS or IL-18, IFN-γ production was very low (supplemental Figure 5). These results suggested a defect in NK cell–mediated release of IFN-γ. However, flow cytometric assessment of intracellular IFN-γ production revealed normal production of IFN-γ on a per-cell basis (data not shown). Therefore, the reduced release of IFN-γ likely reflected the overall low frequency of NK cells among PBMNCs rather than a defect in NK cell function per se. The patient also tested negative for autoantibodies against various cytokines including IFN-γ, TNF, IL-12, IL-23, IFN-α, IFN-ω, IL-6, IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22, and granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (data not shown).

K392R-mutated patient developed T-cell LGL leukemia

Patient 2 with the STAT3 K392R mutation developed aberrant LGL proliferation, which was associated with megaloblastic anemia. In the detailed T-cell subset analysis, the phenotype of the abnormal cells was CD3+TCR-γδ+, and they accounted for 57% of all CD3+ T cells (Figure 3D-F). However, the CD3+TCR-γδ+ population was not homogenous: 45% of the cells were CD8+, whereas the rest had a TCR-γδ+CD4−CD8− immunophenotype (Figure 3D-F). The clonality of the LGL proliferation was confirmed by the positive result of a routine clinical TCR-γδ receptor polymerase chain reaction analysis. Because the LGL proliferation mainly consisted of CD4−CD8− cells, we reviewed the patients’ earlier CD4−CD8− counts. All patients’ proportions of CD3+CD4−CD8− T cells were above median (Table 2), but only in the K392R-mutated patient were they predominantly γδ T cells.

No cytogenetic alterations were found in the LGL subset in routine clinical investigations. To elucidate potential oncogenic single nucleotide variants driving the LGL expansion, the CD3+TCR γδ cells were exome sequenced in parallel with the germline DNA extracted from saliva sample. Four novel somatic mutations were called in the following genes: LY9, RB1CC1, FOXP4 and ICOSLG (Table 3). The variant allele frequency varied between 10% to 17%, suggesting that the mutations were located in a subpopulation of TCR-γδ+ cells. No loss of heterozygosity for the germline STAT3 K392R mutation was observed, and no genomic rearrangements were detected.

Discussion

In this study, we identified activating germline STAT3 mutations K658N,14 K392R,14 and M394T in 3 patients with autoimmunity, hypogammaglobulinemia, lymphoproliferation, and mycobacterial disease. Autoimmunity and hypogammaglobulinemia were seen in all cases, and the displayed autoimmune phenomena are distinctly rare in children (desquamative interstitial pneumonitis, posterior uveitis). Lymphoproliferation (lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, or pediatric T-cell LGL leukemia) was present in 2 cases. One patient developed disseminated mycobacterial disease in late adolescence. The patients presented with somewhat high proportions of CD3+CD4−CD8− T cells with decreased counts of dendritic, Treg, Th17, and NK cells as well as deficiency of switched memory B cells.

Heterozygous loss-of-function STAT3 mutations have been associated with autosomal dominant HIES, which is characterized by high serum IgE, eosinophilia, eczema, and immunodeficiency.5,6 Our first patient developed eczema that differed from the typical hyper-IgE eczema clinically and histopathologically (data not shown). All patients were susceptible to respiratory infections, partly because of their hypogammaglobulinemia. No other features of HIES were noted. The mutations in HIES localize to the DNA-binding and Src-like homolog 2 domains of STAT3, whereas the observed activating STAT3 mutations scatter throughout the protein.5,6,14 Mutations in the DNA-binding domain caused constitutive activation of STAT3, whereas the K658N mutation in the dimerization domain only conferred hypersensitivity to interleukins. The difference in action, however, does not correlate with the phenotype. It is possible that under physiologic conditions, hypersensitivity to low levels of interleukins is sufficient for persistent activation of STAT3 signaling.

Autoimmunity is commonly seen in patients with germline STAT mutations, sometimes with concomitant Treg deficiency.2,3 (For comparison between IPEX-like syndromes caused by STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5B mutations, see supplemental Table 5). STAT3 promotes the activation and expansion of autoimmunity-associated Th17 cells, whereas STAT5 drives the immunosuppressive Treg fate. STAT3 and STAT5b bind to multiple sites of the IL-17 locus, with STAT3 binding promoting IL-17 transcription, and STAT5b binding conversely repressing IL-17 transcription.24,25 Th17 deficiency is seen in loss-of-function STAT3 mutations and HIES.26,27 Curiously, our patients with activating STAT3 mutations also presented with a reduced number of Th17 cells and decreased IL-17 production.

A notable feature of the STAT3 hyperactivity patients was lymphoproliferation, which has not been described in other IPEX-like syndromes.3 The somewhat elevated CD4−CD8− T-cell counts observed in our patients may suggest a defect in lymphocyte apoptosis.28 Notably, patient 2 (K392R) developed T-cell LGL leukemia at age 14. LGL leukemia is mainly diagnosed in the elderly and is often accompanied by autoimmune processes such as rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmune cytopenias. Somatic STAT3 gain-of-function mutations have been identified in 40% to 70% of T-cell LGL leukemia cases.11-13 The occurrence of pediatric LGL leukemia in patient 1 and the presence of LGL-like cells in the BM of patient 2 suggest STAT3 is a central oncogene in LGL leukemia pathogenesis.

Patient 3 (M394T) presented only mild autoimmunity, but developed disseminated mycobacterial disease in late adolescence. In contrast to most known mycobacterial susceptibility syndromes,23 IL-12–IFN-γ signaling was not impaired. Dendritic cell deficiencies cause mycobacterial disease,29 and the observed lack of plasmacytoid dendritic cells may partly explain her condition. Why our IPEX-like patients has not developed mycobacterial infections is unknown. Because dendritic cell deficiency–associated mycobacterial disease onset is often late, the patients’ young age might provide an explanation.

In conclusion, activating germline STAT3 mutations lead to a broad range of immune disturbances, including multiorgan autoimmunity, lymphoproliferation, hypogammaglobulinemia, and delayed-onset mycobacterial disease. Emerging STAT3 inhibitors, some of which are in clinical trials, may benefit such patients. Our results provide insights into the role of STAT3 in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases and highlight the oncogenic nature of STAT3 in LGL leukemia development.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andrew Hattersley and his team in the University of Exeter for an exciting collaboration in the initial discovery of the K392R mutation and the early functional studies, Outi Vaarala and Jarno Honkanen for performing accessory Th1 cytokine immunophenotyping, and personnel at the Hematology Research Unit Helsinki, Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland and Science for Life Laboratory Stockholm for their expert clinical and technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland, Sigrid Juselius Foundation, Emil Aaltonen Foundation, Finnish Medical Foundation, Finnish Cancer Organizations, Instrumentarium Science Foundation, Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation, Alma and K.A. Snellman Foundation, and Foundation for Pediatric Research.

Authorship

Contribution: E.M.H. designed the study, coordinated the project, analyzed the data, and wrote the article; M.K. and H.L.M.R. contributed to writing the article and performed laboratory analysis; S.M., M.S., J.S., and J.K. designed and supervised the study, reviewed the data, and contributed to writing the article; Y.T.B., S.C., V.G., P.K., S.S., H.K., A.J.v.A., R.D., and A.H. designed and performed laboratory analysis; S.E., L.T., and R.K. designed and performed bioinformatics analysis; M.-L.K.-L. and P.E.K. reviewed the immunopathology; T.H.-K., T.O., M.S., K.P., R.U.-S., L.K., and K.H. provided clinical care for the patients; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.P. has received research funding and honoraria from Novartis and Bristol-Myers Squibb; S.M. has received honoraria from Novartis and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and M.S. has received honoraria from Octapharma and Sanquin. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Satu Mustjoki, Hematology Research Unit Helsinki, Helsinki University Central Hospital, Haartmaninkatu 8, PO Box 700, FIN-00290 Helsinki, Finland, e-mail: satu.mustjoki@helsinki.fi; Mikko Seppänen, Immunodeficiency Unit, Division of Infectious Diseases, Helsinki University Central Hospital, PO Box 348, FI-00290 Helsinki, Finland; e-mail: mikko.seppanen@hus.fi; and Janna Saarela, Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland, University of Helsinki, Tukholmankatu 8, PO Box 20, FIN-00290 Helsinki, Finland; e-mail: janna.saarela@helsinki.fi.