P-selectin is a leukocyte adhesion receptor expressed on activated vascular endothelium and platelets that mediates leukocyte rolling and attachment. Because P-selectin is critically involved in inflammation, we used phage display libraries to identify P-selectin–specific peptides that might interfere with its proinflammatory function. Isolated phage contained a highly conserved amino acid motif. Synthetic peptides showed calcium-dependent binding to P-selectin, with high selectivity over E-selectin and L-selectin. The peptides completely antagonized adhesion of monocyte-derived HL60 cells to P-selectin and increased their rolling velocities in flow chamber experiments. Peptide truncation and alanine-scanning studies indicated that an EWVDV (single-letter amino acid codes) consensus motif sufficed for effective inhibition. Intriguingly, the apparent avidity of the peptides was increased 200-fold when presented in a tetrameric form (2 μM versus 10 nM), which is consistent with the proposed divalent interaction of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1) with P-selectin. As the EWVDV peptides inhibit the binding of an established glycoside ligand for P-selectin (sulfated Lewis A), it is conceivable that EWVDV interacts with or in close proximity to the actual carbohydrate recognition domain of P-selectin, without being a direct structural mimic of sialyl Lewisx. These ligands are among the most potent antagonists of P-selectin yet designed. Their high affinity, selectivity, and accessible synthesis provide a promising entry to the development of new anti-inflammatory therapeutics and might be a powerful tool to provide important information on the binding site of P-selectin.

Introduction

A critical event in early inflammatory responses is the recruitment of leukocytes from the bloodstream to sites of injury or infection. The first step in the cell adhesion cascade of inflammation is the initiation of leukocyte rolling along the activated endothelium. This process is mediated mainly by the selectins; calcium-dependent low-affinity adhesion molecules consisting of L-selectin (leukocytes), E-selectin (endothelium), and P-selectin (platelets and endothelium; for reviews, see Tedder et al,1 and Vestweber and Blanks2). The rolling process effectively reduces the velocity of leukocyte movement, which is a prerequisite for the second step, firm adhesion and subsequent transmigration of leukocytes into the subendothelium. Although all 3 selectins are involved in the initial leukocyte recruitment, studies in mice deficient in E-, L-, or P-selectin revealed a predominant role for P-selectin.3 4

P-selectin is stored in α granules of platelets and Weibel-Palade bodies of endothelial cells and is rapidly translocated to the cell surface in response to a variety of inflammatory and thrombogenic stimuli.5,6 On expression, endothelial and platelet P-selectin mediate adhesion to leukocytes,7,8mainly via its high-affinity ligand P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1).9-12 Studies using P-selectin–deficient mice and P-selectin–specific blocking antibodies have shown that P-selectin participates in the pathophysiology of numerous acute and chronic inflammatory diseases13,14 including ischemia/reperfusion injury.15,16 In addition, there is a clear contribution of P-selectin in cardiovascular diseases that have a large inflammatory component such as atherosclerosis,17,18restenosis,19,20 and thrombosis.21 Evidently, inhibition of P-selectin function would be effective as a therapy in various diseases involving leukocyte adherence to vascular endothelial cells or to platelets. However, examples of both potent and specific P-selectin antagonists remain mostly limited to P-selectin–blocking antibodies and PSGL-1 derivatives.

In this study, we describe the use of recombinant phage display technology22 to identify novel calcium-dependent peptide ligands that are specific for P-selectin and demonstrate that these peptides are able to inhibit the interaction between PSGL-1 and P-selectin under static and flow conditions. We further demonstrate that tetramerization of these P-selectin–binding peptides increases their avidity and biologic potency, which is in agreement with the presumed multivalent interaction between P-selectin and PSGL-1.

Materials and methods

Phage libraries

The pComb8 phage-displayed peptide library CX15C (in which X is any amino acid and C is a fixed cysteine residue) was generated at the Department of Biochemistry, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. The pIF4 (X15 and X28) phage libraries were kindly provided by Dr P. Monaci (Instituto di Ricerche di Biologia Moleculaire [IRBM], Rome, Italy).

Antibodies and chimeric proteins

Human P-selectin and human CD4 IgG were kindly provided by Dr B. Appelmelk (Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Human E-selectin IgG was kindly donated by Dr W. Van Dijk (Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Mouse P-selectin IgG, human L-selectin IgG, and monoclonal anti–P-selectin antibodies AK-4 and AC1.2 were from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). WASP12.2 was isolated from HB-299 cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA). Soluble recombinant P-selectin was from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Recombinant PSGL-Ig was kindly donated by Dr R. Schaub (Genetics Institute, Cambridge, MA).

Cells

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably transfected with human P-selectin (CHO-P) and CHO cells with an empty vector (CHO-C)23 were kindly donated by Dr P. Modderman (University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands). HL60 cells were from ATCC.

Isolation of human P-selectin–binding phage

First, 10 μg/mL Fc-specific goat antihuman IgG (Sigma, St Louis, MO) in coating buffer (50 mM NaHCO3, pH 9.6) was incubated overnight at 4°C in a high-binding 96-well plate (Costar, Corning, NY) at 100 μL/well. The next day, wells were washed with assay buffer (20 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with blocking buffer (3% bovine serum albumin [BSA] in assay buffer). After washing, wells were incubated with 0.3 μg/mL human P-selectin–IgG (PS-IgG; 2 hours at 37°C), washed, and subsequently incubated for 2 hours at room temperature (RT) with the phage libraries at 1010 colony-forming units in 100 μL binding buffer (0.1% BSA, 0.5% Tween 20 in assay buffer). Wells were washed 10 times with binding buffer and binding phage were eluted by incubation for 5 minutes at RT with 100 μL elution buffer (0.1 M glycine/HCl, pH 2.2). Phage were titrated, amplified, and purified as described.24 Amplified phage were used for further selection rounds. For DNA sequencing of enriched phage pools, plasmid DNA was isolated from single colonies using the Wizard Plus SV Miniprep DNA Purification System (Qiagen, Westburg, Belgium). DNA sequencing of the plasmids was conducted at the DNA-sequencing facility of the Leiden University Medical Center using a standard M13 primer.

Peptides

Synthetic N-terminal biotinylated peptides TM1, TM2, TM11, TM16, TM17, TM31, and TM32 were prepared by standard solid-phase methods at the Division of Immunology (Dr. Ruurd van der Zee, Utrecht University, The Netherlands). All other peptides were purchased from Eurosequence (Groningen, The Netherlands). The quality of the peptides was checked by mass spectroscopy and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Competition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (strepPO; Amersham Freiburg, Germany) was incubated for 2 hours at RT with TM11-biotin in a 1:4 molar ratio, thereby forming a tetrameric TM11/strepPO-complex (TM11-PO). For competition studies, microtiter wells were coated with human PS-IgG as described in “Isolation of human P-selectin–binding phage.” Wells were incubated for 1 hour at 4°C with 5 nM TM11-PO in assay buffer, in the presence or absence of titered amounts of peptides. After washing 6 times with assay buffer, the wells were incubated for 15 minutes at RT with 100 μL TMB/H2O2 (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The reaction was stopped by adding 2 M H2SO4 and the absorbance was read at 450 nm. For competition studies using HSO3-Lea-PAA-biotin (Dextra Laboratories, Reading, United Kingdom), P-selectin–coated wells were incubated with HSO3-Lea-PAA-biotin (0.3 μg/mL in assay buffer containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 0.1% BSA) in the presence of 0 to 200 μM peptides (2 hours at 37°C), washed, and incubated with strepPO (1:3000 in assay buffer) for 30 minutes. Binding was determined as described above for TM11-PO.

HL60 adhesion assay and flow chamber perfusion studies

HL60 cells were labeled with 5 μM calcein-am (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) for 30 minutes at 37°C. HL60 cells (50 000/well) were added to CHO-P cells (seeded in 96-well plates) in the presence or absence of antagonists (1 hour at 4°C). After gentle washing, fluorescence was measured. Flow chamber studies using CHO-P monolayers and calcein-am–labeled HL60 cells (2 × 106/mL) were performed as described,25 at a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min (wall shear rate 300 s−1).

Surface plasmon resonance (Biacore) analysis

A Biacore 2000 instrument (Biacore AB, Uppsala, Sweden) was used to analyze the interaction between human PS-IgG and the biotinylated peptides. All experiments were performed at 20°C using running buffer (20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.005% Surfactant P20, pH 7.4). Streptavidin (Promega, Madison, WI; 10 μg/mL in acetate buffer, pH 4.8) was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip at 5 μL/min (∼2000 response units) using standard amine coupling according to the manufacturer's instructions. Biotinylated peptides were allowed to bind the immobilized streptavidin. Binding kinetics of human PS-IgG to the immobilized peptides was determined by injecting a concentration range (0-40 nM) of human PS-IgG onto the immobilized streptavidin-peptide at a flow rate of 20 μL/min. Control chimeric or recombinant proteins were injected at 160 nM. In some studies, the injection of PS-IgG was followed by injections of P-selectin antibodies at 10 μg/mL. At the end of each injection, the sensor chips were regenerated with 100 mM NaOH and equilibrated with running buffer. All curves were corrected for nonspecific binding by an online baseline subtraction of ligand binding to immobilized streptavidin/biotin in a control flow channel. Binding kinetics were analyzed using BIAevaluation software (V2.1; Pharmacia Biosensor, Uppsala, Sweden).

Results

Screening of phage-displayed peptide libraries against human P-selectin

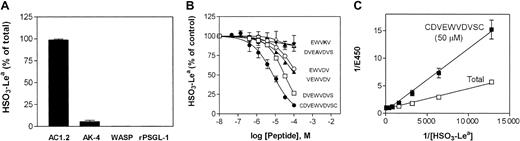

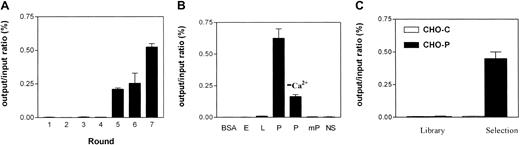

We used a 15-amino acid cysteine-constrained phage-displayed peptide library (pComb8-CX15C) to identify novel P-selectin–binding peptides. For selections, chimeric P-selectin, consisting of human IgG1 fused to the binding domain of human P-selectin (PS-IgG),26 was immobilized onto microtiter wells via an anti-IgG antibody. A biopanning protocol involving gentle washes in the first 2 rounds, and more stringent washes combined with decreasing amounts of chimeric receptor in later rounds, resulted in an approximate 200-fold enrichment of P-selectin–binding phage for the pComb8-constrained library, after 5 rounds of biopanning (Figure1A). The enriched phage pool showed no binding to human E-selectin and mouse P-selectin, and only little binding to L-selectin, although all 3 selectins were functional and showed comparable HSO3-Lea and HL60 cell binding (not shown). Human P-selectin binding was calcium dependent (Figure 1B), as was observed both in the absence of calcium and in the presence of EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid). The enriched phage pool specifically bound to human P-selectin–transfected CHO cells (CHO-P) in contrast to the starting library, confirming that the phage also effectively interacted with membrane-bound P-selectin (Figure 1C).

Isolation and specificity of human P-selectin–binding phage.

(A) Selection on immobilized human PS-IgG using the pComb8 phage display peptide library, resulting in a 200-fold enrichment of P-selectin–binding phage in the fifth round of selection. (B) The enriched phage pools were specific for PS-IgG compared with human E-selectin–Ig (E-Sel-IgG) and L-selectin–IgG, and mouse PS-IgG (mP). Binding was reduced in the absence of calcium. Nonspecific phage pools (NS) showed little binding to human P-selectin. (C) Selected phage pools (Selection) specifically bound human P-selectin–transfected CHO cells compared with nonselected library phage (Library). Values are expressed as the ratio of acid-eluted phage (output) and input titer (generally 109-1010colony-forming units) and represent means of duplicate experiments ± variation.

Isolation and specificity of human P-selectin–binding phage.

(A) Selection on immobilized human PS-IgG using the pComb8 phage display peptide library, resulting in a 200-fold enrichment of P-selectin–binding phage in the fifth round of selection. (B) The enriched phage pools were specific for PS-IgG compared with human E-selectin–Ig (E-Sel-IgG) and L-selectin–IgG, and mouse PS-IgG (mP). Binding was reduced in the absence of calcium. Nonspecific phage pools (NS) showed little binding to human P-selectin. (C) Selected phage pools (Selection) specifically bound human P-selectin–transfected CHO cells compared with nonselected library phage (Library). Values are expressed as the ratio of acid-eluted phage (output) and input titer (generally 109-1010colony-forming units) and represent means of duplicate experiments ± variation.

DNA sequence analysis of the P-selectin–binding phage of the fifth, sixth, and seventh round of selection revealed a consensus peptide motif E(D)-W(F)-V(C)-D-V that was shared by 5 phage clones isolated from the constrained pComb8 library (Table1). Interestingly, subsequent selections using nonconstrained pIF libraries of 15 and 28 amino acids (pIF-X15 and pIF-X28) resulted in the isolation of a comparable motif, strongly pointing out the importance of this region and suggesting that linear sequences perform equally well (Table1). All sequenced clones from the 3 different libraries contained a conserved aspartic acid residue, mostly flanked by 2 valine residues and an aromatic tryptophan or phenylalanine residue (80% and 20% of the sequenced clones, respectively). A glutamic or aspartic acid residue was observed in all sequenced clones at a distance of 2 to 6 amino acids downstream from the conserved aspartic acid residue of the consensus motif.

Binding of synthetic peptides to human P-selectin

Synthetic peptides derived from phage clones TM1, TM2, TM11, TM16, TM17, TM31, and TM32 were initially tested for binding to human P-selectin by using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) spectrometry, in which molecular interactions are reflected by an increase in response units. Peptides were immobilized onto a Biacore sensor chip and the kinetics of interaction between human PS-IgG and the immobilized peptides were measured, showing the highest increase in response units for TM11 and TM31 (not shown).

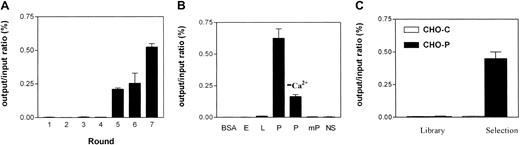

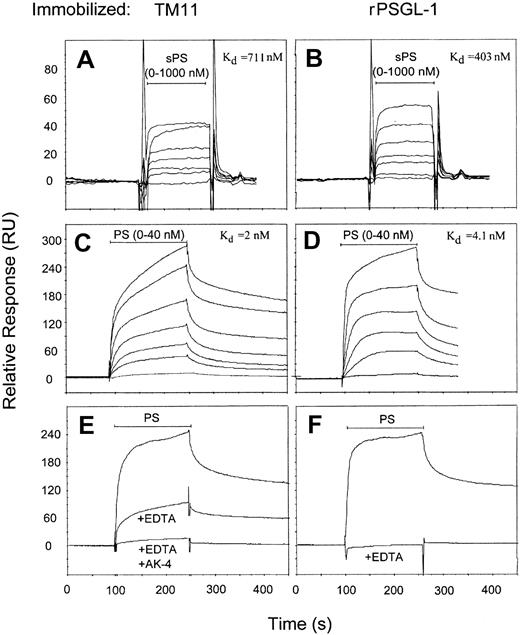

The binding kinetics of monomeric soluble P-selectin (sPS) and PS-IgG to TM11 was measured by injecting increasing concentrations of both proteins over the TM11-immobilized sensor chip. For comparison, a separate flow channel was coated with recombinant PSGL-1–IgG (rPSGL-Ig) and subjected to the same injections. All curves were corrected for nonspecific binding by online baseline subtraction of ligand binding to immobilized streptavidin/biotin in a control flow channel.

Injection of sPS (0-1000 nM) resulted in a fast increase of response units on TM11- and PSGL-1–immobilized surfaces (Figure2A and B, respectively), which was not observed when sPS was coinjected with blocking antibody WASP 12.2 (not shown). The Kd for TM11 (711 nM) and PSGl-1 (403 nM) was calculated by plotting the equilibrium response versus the sPS concentration (BIAevaluation software). The Kd of sPS binding to immobilized PSGL-1, as well as the observed rapid binding kinetics, are in accordance with data reported by Mehta et al.27

Binding of human P-selectin to immobilized TM11 peptide and rPSGL-Ig.

Biotinylated TM11 was bound to the sensor surface through conjugation to immobilized streptavidin (A,C,E). rPSGL-Ig was directly immobilized onto the sensor chip (B,D,F). Soluble P-selectin (sPS) and PS-IgG (PS) were injected over both surfaces at a flow rate of 20 μL/min for 30 and 150 seconds, respectively, as indicated by the horizontal bar. Bound selectins were removed by a short injection of 10 mM NaOH (not shown) and were reused for subsequent injections. The figure shows an overlay of the sensorgrams. (A,B) Increasing concentrations of sPS (0-1000 nM, 2-fold dilutions) show binding to TM11 and PSGL-1 surfaces, as indicated by an increase in response units. The Kd values calculated by Biacore software are indicated in the figure. (C,D) Binding of increasing concentrations of PS (0-40 nM, 2-fold dilutions) show enhanced binding kinetics. (E,F) Binding of PS (20 nM) to TM11 and PSGL-1 was reduced in the presence of EDTA (10 mM). Residual binding of PS to TM11 in the presence of EDTA could be inhibited by coinjection of blocking antibody AK-4.

Binding of human P-selectin to immobilized TM11 peptide and rPSGL-Ig.

Biotinylated TM11 was bound to the sensor surface through conjugation to immobilized streptavidin (A,C,E). rPSGL-Ig was directly immobilized onto the sensor chip (B,D,F). Soluble P-selectin (sPS) and PS-IgG (PS) were injected over both surfaces at a flow rate of 20 μL/min for 30 and 150 seconds, respectively, as indicated by the horizontal bar. Bound selectins were removed by a short injection of 10 mM NaOH (not shown) and were reused for subsequent injections. The figure shows an overlay of the sensorgrams. (A,B) Increasing concentrations of sPS (0-1000 nM, 2-fold dilutions) show binding to TM11 and PSGL-1 surfaces, as indicated by an increase in response units. The Kd values calculated by Biacore software are indicated in the figure. (C,D) Binding of increasing concentrations of PS (0-40 nM, 2-fold dilutions) show enhanced binding kinetics. (E,F) Binding of PS (20 nM) to TM11 and PSGL-1 was reduced in the presence of EDTA (10 mM). Residual binding of PS to TM11 in the presence of EDTA could be inhibited by coinjection of blocking antibody AK-4.

Similar SPR studies with PS-IgG (0-40 nM) revealed completely different binding kinetics than observed for sPS, both for TM11- and for PSGL-1–coated surfaces (Figure 2C-D). The apparent Kdvalues were 2.0 and 4.1 nM for TM11 and PSGL-1, respectively, suggesting an enhanced avidity for TM11 and PSGL-1 due to the dimerized nature of PS-IgG. Although binding of PS-IgG to TM11 was very much comparable to its binding to PSGL-1, there also was an intriguing difference. Whereas binding of PS-IgG to PSGL-1 was completely dependent on Ca++ (Figure 2F), that to TM11 was only partially inhibited in the presence of EDTA (Figure 2E), or in the absence of calcium (not shown). The residual, Ca++-independent, binding could be abolished by the blocking antibody AK-4.

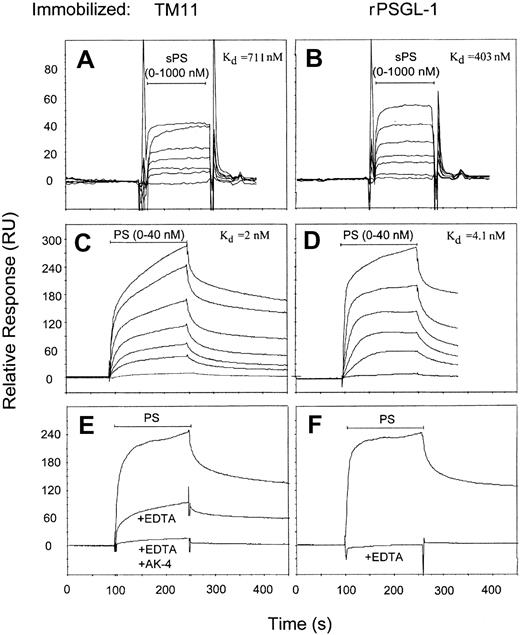

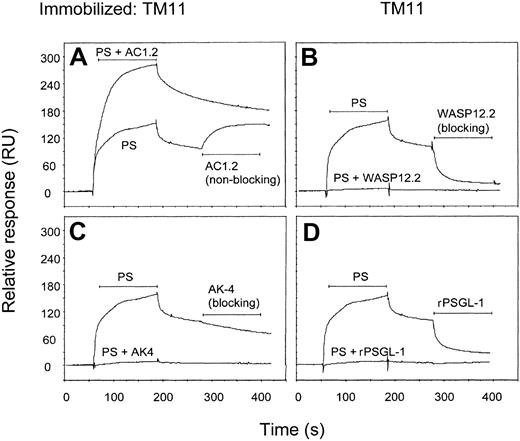

We investigated the effect of P-selectin antibodies and PSGL-1 on P-selectin binding to TM11. In the first set of experiments, PS-IgG was coinjected with various antibodies or PSGL-1 over the TM11 surface. Binding of PS-IgG was completely blocked by the blocking antibodies WASP (Figure 3B) and AK-4 (Figure 3C), as well as by PSGL-1 (Figure 3D). In contrast, non–blocking antibody AC1.2 increased the binding response, due to the higher molecular weight of the AC1.2/P-selectin complex as compared with that of P-selectin (Figure 3A). In a second set of experiments, PS-IgG was allowed to bind TM11 in a preinjection, followed by a second injection containing the antibody or PSGL-1. Non–blocking antibody AC1.2 was able to bind the TM11-associated P-selectin without disturbing the interaction between peptide and P-selectin (Figure 3A). Blocking antibody WASP 12.2 (Figure 3B) and PSGL-1 (Figure 3D) completely displaced P-selectin from the peptide. Unexpectedly, blocking antibody AK-4 was not able to bind or displace P-selectin from TM11 (Figure 3C), suggesting that the binding of P-selectin to TM11 changes the AK-4 recognition site or renders the AK-4 epitope inaccessible. All of the 3 antibodies were able to bind P-selectin that was directly immobilized onto the sensor chip (not shown).

Displacement of TM11: association to P-selectin by blocking antibodies and rPSGL-Ig.

Human P-selectin (20 nM, 50 μL) was injected over the TM11 surface, followed by blocking or non–blocking antibodies (10 μg/mL). In the same figures, coinjections of P-selectin and antibodies or rPSGL-Ig are shown. The horizontal bars indicate the infusion periods. (A) Non–blocking antibody AC1.2 was able to bind TM11-associated P-selectin as indicated by an increase in response units. Coinjection of P-selectin with AC1.2 resulted in a higher response than injection of P-selectin alone, due to the formation of a P-selectin/AC1.2 complex. (B) Blocking antibody WASP 12.2 displaced P-selectin from TM11. (C) Blocking antibody AK-4 was not able to bind or displace TM11-bound P-selectin when it was injected after P-selectin, although coinjection with P-selectin led to complete inhibition of TM11 binding. (D) rPSGL-Ig displaced P-selectin from TM11. Results represent typical sensorgrams of at least 2 experiments.

Displacement of TM11: association to P-selectin by blocking antibodies and rPSGL-Ig.

Human P-selectin (20 nM, 50 μL) was injected over the TM11 surface, followed by blocking or non–blocking antibodies (10 μg/mL). In the same figures, coinjections of P-selectin and antibodies or rPSGL-Ig are shown. The horizontal bars indicate the infusion periods. (A) Non–blocking antibody AC1.2 was able to bind TM11-associated P-selectin as indicated by an increase in response units. Coinjection of P-selectin with AC1.2 resulted in a higher response than injection of P-selectin alone, due to the formation of a P-selectin/AC1.2 complex. (B) Blocking antibody WASP 12.2 displaced P-selectin from TM11. (C) Blocking antibody AK-4 was not able to bind or displace TM11-bound P-selectin when it was injected after P-selectin, although coinjection with P-selectin led to complete inhibition of TM11 binding. (D) rPSGL-Ig displaced P-selectin from TM11. Results represent typical sensorgrams of at least 2 experiments.

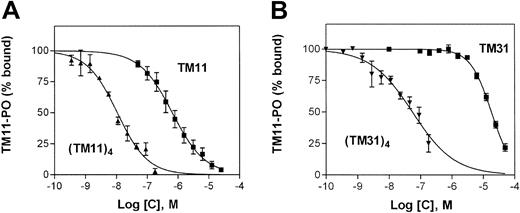

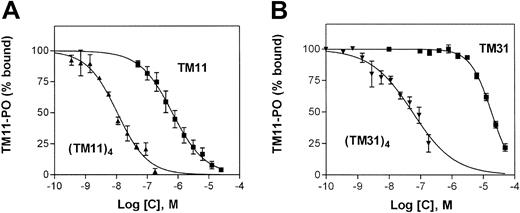

For competition studies, a preformed complex of biotinylated TM11 with streptavidin-peroxidase (TM11-PO) was used. TM11-PO bound specifically and calcium dependently to immobilized human P-selectin (not shown). Competition studies were performed by coincubation of the TM11-PO complex with increasing concentrations of TM11 and TM31 peptides (Figure 4A-B). Surprisingly, the obtained inhibiting concentrations (IC50) for TM11 and TM31 were 2 and 19 μM, respectively, which is 1000-fold higher than the Kd value for TM11 in the SPR study (2 nM). Because we had also observed a differential avidity of TM11 for monomeric and dimeric P-selectin in SPR studies, these results strongly suggest that both the ligand and its receptor need to be multivalent to obtain high-avidity binding. To investigate the effect of multimerization on the peptide activity, biotinylated TM11 and TM31 were incubated with streptavidin in a 4:1 molar ratio to form the tetrameric complexes (TM11)4 and (TM31)4. Competition studies with these tetrameric complexes showed that (TM11)4 and (TM31)4 displayed approximately 200-fold higher affinities for P-selectin as compared with the monomeric peptides (IC50 10 and 61 nM, respectively, Figure 4A-B).

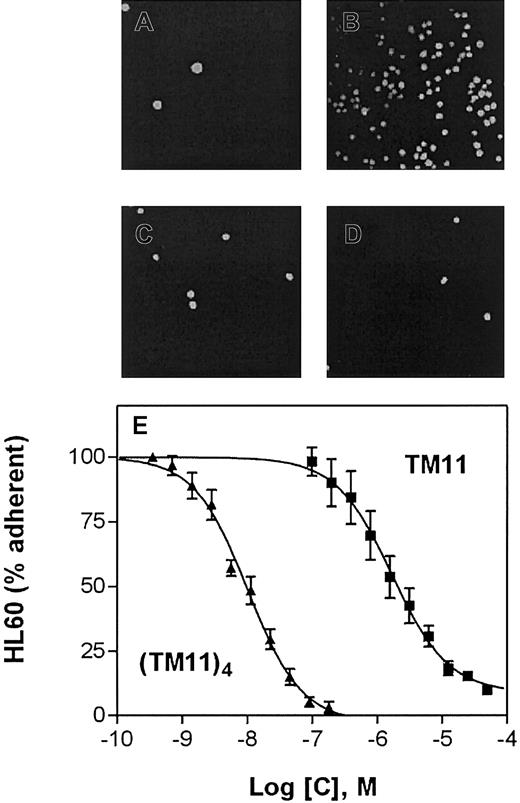

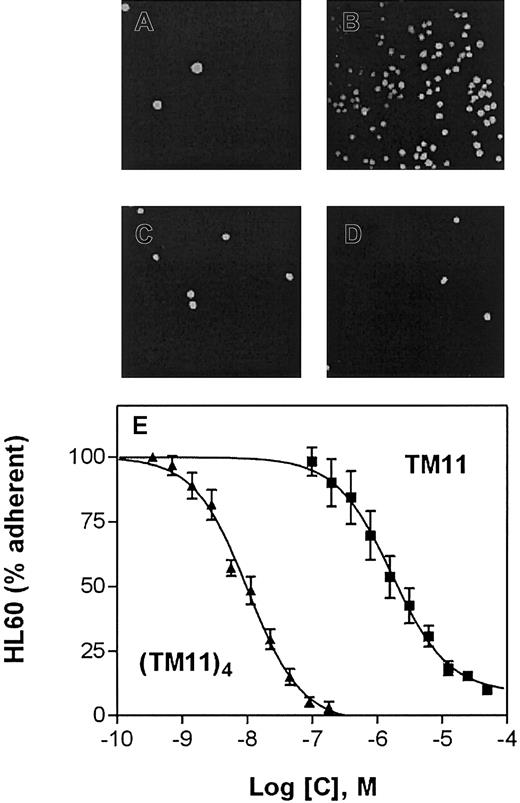

Blocking of P-selectin–mediated cell adhesion by synthetic peptides

The endogenous P-selectin ligand, PSGL-1, interacts with P-selectin only in the presence of calcium. The calcium dependence of P-selectin–binding phage and their corresponding peptides in SPR and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), combined with the antibody studies on TM11-associated P-selectin, already suggested that the peptides interact in proximity to the actual ligand-binding site of P-selectin. If so, the peptide ligand might be able to antagonize P-selectin–mediated cell adhesion. An HL60/P-selectin cell adhesion assay was set up to investigate this. Monocyte-derived HL60 cells have a high expression of PSGL-128 and are adherent to P-selectin–transfected CHO cells (Figure5B), but not to control CHO cells (Figure5A). The P-selectin–mediated cell adhesion was completely blocked in the presence of 12.5 μM TM11 or 45 nM (TM11)4, indicating that the monomeric peptide and the tetrameric complex are antagonizing the biologic function of P-selectin (Figure 5C-D). Effective concentrations (EC50) for the inhibition of HL60 adhesion to P-selectin correlated well with the IC50 values obtained in the TM11-PO competition studies, in which the multimer was 200-fold more potent than the monomeric TM11 peptide (Figure 5E; EC50 10 nM versus 2 μM, respectively).

Tetramerization of peptides results in high-affinity binding.

Competition studies of synthetic peptides with TM11-PO (2 nM) for P-selectin binding were performed in an ELISA. (A) Competition of TM11 (▪) with TM11-PO resulted in an IC50 of 2 μM. A 200-fold increase in affinity was observed when TM11 was presented as a tetramer, (TM11)4, by conjugation of TM11-biotin to streptavidin (▴, IC50 = 10 nM). (B) The IC50 of monomeric TM31 (▪, 19 μM) was 300-fold lower than that of tetrameric TM31 (▴, IC50 = 61 nM). Values represent means of triplicate experiments ± variation.

Tetramerization of peptides results in high-affinity binding.

Competition studies of synthetic peptides with TM11-PO (2 nM) for P-selectin binding were performed in an ELISA. (A) Competition of TM11 (▪) with TM11-PO resulted in an IC50 of 2 μM. A 200-fold increase in affinity was observed when TM11 was presented as a tetramer, (TM11)4, by conjugation of TM11-biotin to streptavidin (▴, IC50 = 10 nM). (B) The IC50 of monomeric TM31 (▪, 19 μM) was 300-fold lower than that of tetrameric TM31 (▴, IC50 = 61 nM). Values represent means of triplicate experiments ± variation.

TM11 inhibits HL60 adhesion to P-selectin.

Monomeric and tetrameric TM11 were tested for their capacity to inhibit P-selectin–mediated cell adhesion. HL60 cells, expressing PSGL-1, were labeled with calcein and allowed to adhere to P-selectin–transfected CHO cells (CHO-P) in the presence or absence of TM11 and (TM11)4. (A) HL60 cells did not adhere to control CHO cells. (B) Specific adhesion of HL60 cells to CHO-P was observed in the absence of peptides. (C) HL60 cell adhesion to CHO-P could be completely blocked by 12.5 μM TM11, or (D) by 45 nM (TM11)4. HL60 cells were visualized by calcein fluorescence detection. Original magnification, × 100 (A-D). (E) TM11 (▪) and (TM11)4 (▴) inhibit HL60 adhesion to CHO-P at concentrations comparable to ELISA IC50 values (Figure 4). EC50 values are 2.2 μM and 11 nM for TM11 and (TM11)4, respectively. Values represent means of quadruplicate experiments ± variation.

TM11 inhibits HL60 adhesion to P-selectin.

Monomeric and tetrameric TM11 were tested for their capacity to inhibit P-selectin–mediated cell adhesion. HL60 cells, expressing PSGL-1, were labeled with calcein and allowed to adhere to P-selectin–transfected CHO cells (CHO-P) in the presence or absence of TM11 and (TM11)4. (A) HL60 cells did not adhere to control CHO cells. (B) Specific adhesion of HL60 cells to CHO-P was observed in the absence of peptides. (C) HL60 cell adhesion to CHO-P could be completely blocked by 12.5 μM TM11, or (D) by 45 nM (TM11)4. HL60 cells were visualized by calcein fluorescence detection. Original magnification, × 100 (A-D). (E) TM11 (▪) and (TM11)4 (▴) inhibit HL60 adhesion to CHO-P at concentrations comparable to ELISA IC50 values (Figure 4). EC50 values are 2.2 μM and 11 nM for TM11 and (TM11)4, respectively. Values represent means of quadruplicate experiments ± variation.

Identification of the minimal essential binding motif

Based on the striking homology among the P-selectin–binding peptides, we assumed that the recognition of P-selectin by phage and peptides was mediated mainly by this consensus motif. Gradual truncation of the amino acids from TM11 flanking the consensus motif showed that EWVDV (single-letter amino acid codes) was the minimal motif of TM11 able to bind P-selectin and exert a biologic effect (Table 2, A15-19, A29). Deletion of the glutamic acid within EWVDV (A138) resulted in a dramatic (more than 100-fold) decrease in the apparent affinity. Alanine and other amino acid substitutions confirmed the critical role of amino acids within the WVDV motif (A20-27, A129-137), in particular the aspartic acid (A135, A136). Val→Ala substitutions within the core motif, involving only a minor structural change, completely abolished binding (A24, A26). The Glu→Ala substitution within DVEWVDVS reduced the IC50 by almost 7-fold, indicating that this amino acid is clearly not as critical for binding P-selectin as the WVDV core sequence (A22). At this position, negative (Asp: A29), neutral (Ala: A131), or even positively charged residues (Lys: A130) were allowed, but glutamic acid was preferred (A29). Although it was expected from the peptide sequences of the selected phage clones that Trp→Phe (A132) and Val→Cys (A133) conversions were tolerated, these substitutions reduced the IC50 in ELISA by 33-and 14-fold, respectively. Furthermore, the avidity of cysteine-constrained peptides tended to be slightly higher than their linear counterparts (TM11, A15, A17).

Rolling velocities in flow chamber perfusion studies

We assessed the ability of the novel peptides to have an effect on P-selectin–mediated cell adhesion under flow conditions, as a model for the inflamed vascular wall. Adhesion assays were performed on CHO-P monolayers, in a parallel plate flow chamber at a shear rate of 300 s−1 The interaction of PSGL-1–expressing HL60 cells with P-selectin was monitored in the presence or absence of antagonists. The average rolling velocity of the HL60 cells to CHO-P monolayers in the absence of inhibitor was 19 μm/s. The presence of EWVDV (20 μM) and (TM11)4 tetramer (100 nM) increased the rolling velocity by almost 2-fold (Figure 6,P < .01), reflecting the impaired interaction between PSGL-1 and P-selectin. Injection of P-selectin–blocking antibody WASP 12.2 (10 μg/mL) abolished more than 99% of HL60 rolling, excluding the presence of non–P-selectin–mediated cell rolling (not shown).

TM11 increases HL60 rolling velocities in flow chamber perfusion experiments.

The rolling of calcein-am–labeled HL60 cells over CHO-P–coated coverslips was measured by real-time video microscopy in the presence or absence of peptides. Rolling velocities were calculated from the average rolling distance per elapsed time period. Rolling velocities were significantly enhanced by almost 2-fold in the presence of 100 nM (TM11)4 and DVEWVDVS (20 μM) compared with their controls [(Biotin)4 and DEAVDVS, respectively;P < .01]. Values represent means of rolling velocities of at least 20 cells in 3 separate experiments.

TM11 increases HL60 rolling velocities in flow chamber perfusion experiments.

The rolling of calcein-am–labeled HL60 cells over CHO-P–coated coverslips was measured by real-time video microscopy in the presence or absence of peptides. Rolling velocities were calculated from the average rolling distance per elapsed time period. Rolling velocities were significantly enhanced by almost 2-fold in the presence of 100 nM (TM11)4 and DVEWVDVS (20 μM) compared with their controls [(Biotin)4 and DEAVDVS, respectively;P < .01]. Values represent means of rolling velocities of at least 20 cells in 3 separate experiments.

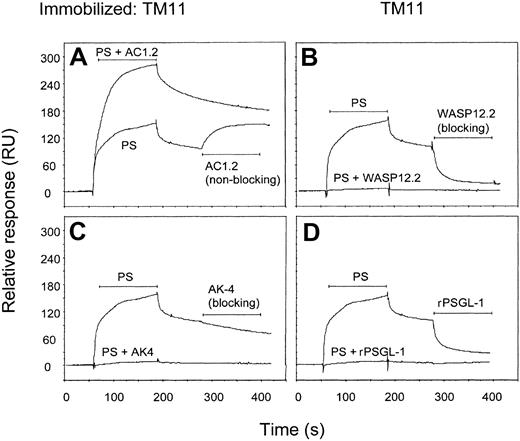

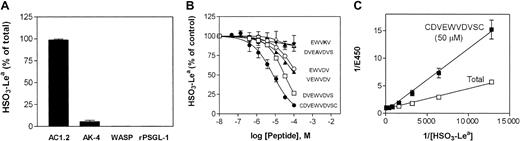

Determination of the peptide-binding site on P-selectin

As previously suggested, P-selectin interacts with 2 separate domains within PSGL-1: the sulfated peptide backbone and the sialyl Lewisx (sLex) moiety.29 30 Because the affinity of sLex for P-selectin is very low (mM range), competition studies were conducted using the sLex analog sulfated Lewisa (HSO3-Lea), which is conjugated to polyacrylic acid to increase its affinity. Binding of HSO3-Lea to PS-IgG was inhibited by PSGL-1 and by the blocking antibodies WASP 12.2 and AK-4, but not by non–blocking antibody AC1.2 (Figure 7A). Binding of HSO3-Lea could be completely inhibited by EWVDV-containing peptides, but not by control sequences (Figure 7B). However, the IC50 values for inhibition of HSO3-Lea binding (EWVDV = 158 μM, VEWVDV = 119 μM, DVEWVDVS = 32 μM, CDVEWVDVSC = 7.6 μM) seemed to inversely correlate with the length of the peptide, suggesting that although EWVDV might bind proximal to the actual carbohydrate recognition domain of P-selectin, the size of the EWVDV-flanking domains appear to govern the extent of inhibition of HSO3-Lea binding.

EWVDV-containing peptides inhibit HSO3-Lea binding to human P-selectin.

Competition studies of HSO3-Lea-PAA-biotin (0.3 μg/mL) binding to P-selectin by synthetic peptides were performed in an ELISA. (A) HSO3-Lea-PAA-biotin binding is inhibited by blocking antibodies AK-4, WASP 12.2, and by rPSGL-Ig, but not by non–blocking antibody AC1.2. (B) Binding of HSO3-Lea-PAA-biotin is inhibited by EWVDV-containing peptides, but not by control peptides. IC50 values are dependent on the length of the peptide. Bold letters indicate the amino acids that differ from the original TM11 sequence. (○) EWVDV, IC50 = 158 μM; (▵) EWVKV; (▴) VEWVDV, IC50 = 119 μM; (■) DVEWVDVS, IC50 = 32 μM; (♦) DVEAVDVS; (●) CDVEWVDVSC, IC50 = 7.6 μM. (C) Lineweaver-Burke plot of HSO3-Lea-PAA-biotin binding in the presence and absence of 50 μM CDVEWVDVSC. Linear regression analysis reveals that both curves cross the y-axis through the same point (E450 = 1.01 ± 0.01 for control and 1.08 ± 0.03 for inhibitor) indicative of competitive inhibition.

EWVDV-containing peptides inhibit HSO3-Lea binding to human P-selectin.

Competition studies of HSO3-Lea-PAA-biotin (0.3 μg/mL) binding to P-selectin by synthetic peptides were performed in an ELISA. (A) HSO3-Lea-PAA-biotin binding is inhibited by blocking antibodies AK-4, WASP 12.2, and by rPSGL-Ig, but not by non–blocking antibody AC1.2. (B) Binding of HSO3-Lea-PAA-biotin is inhibited by EWVDV-containing peptides, but not by control peptides. IC50 values are dependent on the length of the peptide. Bold letters indicate the amino acids that differ from the original TM11 sequence. (○) EWVDV, IC50 = 158 μM; (▵) EWVKV; (▴) VEWVDV, IC50 = 119 μM; (■) DVEWVDVS, IC50 = 32 μM; (♦) DVEAVDVS; (●) CDVEWVDVSC, IC50 = 7.6 μM. (C) Lineweaver-Burke plot of HSO3-Lea-PAA-biotin binding in the presence and absence of 50 μM CDVEWVDVSC. Linear regression analysis reveals that both curves cross the y-axis through the same point (E450 = 1.01 ± 0.01 for control and 1.08 ± 0.03 for inhibitor) indicative of competitive inhibition.

We investigated whether the EWVDV peptides are competitive inhibitors of HSO3-Lea binding to P-selectin by Lineweaver-Burke analysis at which the reciprocal of HSO3-Lea binding (extinction) is plotted versus that of the HSO3-Lea concentration in the absence or presence of CDVEWVDVSC (Figure 7C) or analogues. The calculated Bmax values were 1.01 ± 0.01 in the absence and 0.98 ± 0.03 (EWVDV), 0.97 ± 0.03 (DVEWVDVS), and 1.08 ± 0.03 (CDVEWVDVSC) in the presence of 50 μM (CDVEWVDVSC) or 100 μM of the inhibiting peptides. The fact that the Bmaxvalues are essentially identical suggests that the peptides are competitive inhibitors of HSO3-Lea binding and that the peptides interact with the C-type lectin domain on P-selectin.

Discussion

P-selectin is proposed to play a key role in many inflammatory diseases by mediating the adhesion of leukocytes to activated platelets and endothelium (for a review, see Vestweber and Blanks2). Therefore, intervention strategies focusing on the inhibition of P-selectin–mediated cell adhesion hold great promise for anti-inflammatory therapy. Studies in P-selectin–deficient mice13,17-19,31,32 and in various animal models in which P-selectin was functionally disrupted by specific anti–P-selectin antibodies or PSGL-1 derivatives15,33 34 indeed showed that clinically relevant effects can be established by blocking P-selectin function. In this paper, we describe the identification of small peptides that bind specifically and calcium dependently to P-selectin, inhibit the interaction between P-selectin and its natural ligand, PSGL-1, and increase rolling velocities of HL60 on CHO-P cells in flow chamber perfusion studies.

In recent years, the development of potent P-selectin inhibitors has been the subject of extensive investigation and included mostly synthetic analogs of PSGL-1 and its sLex moiety (reviewed by Lefer35), including sulfopeptides, which are based on the N-terminal domain of PSGL-1.29,36 However, it has been difficult to design P-selectin–specific antagonists from these parent compounds, because PSGL-1 and sLex also display affinity for E-selectin and L-selectin.26,37,38 The peptides we identified show a highly preferred binding to P-selectin, whereas no binding to E-selectin is observed. The low binding of the peptides and phage particles to L-selectin suggests that L-selectin becomes a target only at higher peptide concentrations. Although simultaneous targeting of selectins might be beneficial or even a prerequisite in several pathophysiologic conditions,14,39 selective targeting of P-selectin might confer the advantage of a specific intervention in atherothrombotic events while leaving the other selectins operative to mediate cell adhesion processes in response to more general inflammatory stimuli. For instance, mice deficient in P-selectin and E-selectin are more susceptible to infections.40 41Moreover, specific P-selectin ligands will be interesting from a mechanistic viewpoint, because they will enable investigators to delineate the notoriously intricate process of ligand binding to the selectins.

To identify novel ligands with high specificity for P-selectin, we used recombinant phage display technology, an unbiased combinatorial approach that has been successfully applied to discover novel peptides (for a review, see Cortese et al22) for several target proteins. The selections on chimeric P-selectin revealed a conserved sequence in the isolated phage pools that already pointed at the importance of the WVDV motif for the recognition of P-selectin. Truncation studies confirmed that EWVDV is the smallest fragment with comparable avidity to P-selectin as its parent peptide, TM11. As predicted from the isolated phage sequences, it was expected that EFVDV and EWCDV would be equally active in their avidity and biologic potential as EWVDV, especially because the substitutions involved structurally comparable amino acids. However, the observed more than 10-fold lower affinities for EFVDV and EWCDV suggest that some substitutions are well tolerated in the phage context, but not in a nonphage peptide context. Apparently, the structural environment and conformation of the binding motif is an additional determinant of P-selectin recognition.

Recently, multivalent polylysine conjugates of a low-affinity sLex analog have been reported to display a much higher affinity for E-selectin.42 We show that multimerization of TM31 and TM11 results in a 200-fold enhanced avidity (on a molar basis) in ELISAs and cell adhesion assays. Likewise, the SPR data showed a similar high avidity for dimeric P-selectin to immobilized TM11 as compared with monomeric P-selectin, suggesting that dimerization of TM11 would be sufficient for optimal recognition by P-selectin. Importantly, P-selectin is also present in the cell membrane as a homodimer.43 Although the membrane-bound homodimer may not have the exact same spatial arrangement as the chimeric P-selectin dimer, we also observed superior binding of peptide tetramers to CHO-P cells. The tetrameric streptavidin/peptide complex might allow, to some extent, a flexible orientation of the EWVDV motif, hereby compensating for a difference between dimeric PS-IgG and the naturally occurring dimeric P-selectin. The stimulatory effect of ligand multimerization bears an interesting resemblance to PSGL-1. PSGL-1 forms homodimers covalently linked by a single disulfide bridge.44Recently, it has been shown that the paired dimerization of PSGL-1 and P-selectin stabilizes cell rolling and enhances tether strength under flow conditions.45 Although studies addressing the question of whether PSGL-1 dimerization is a prerequisite for high-affinity binding to P-selectin have been controversial,46-50 our results underline that multimerization of P-selectin ligands in general can be an effective strategy to increase their avidity and biologic potency. The EWVDV-based peptides are among the few selective and potent ligands for P-selectin and completely antagonize HL60 adhesion to P-selectin under static conditions. Under flow conditions, HL60 adhesion blockade is not complete, but the reduced interaction between HL60 and P-selectin is reflected by an increased rolling velocity. The differential inhibition of static and rolling adhesion may be related to the higher shear forces under flow conditions (rolling). As has been reported for recognition of vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)51 and von Willebrand factor (VWF),52,53 shear can markedly modulate receptor-ligand interaction due to ligand tethering, protein folding, or site accessibility, which leads to a partial inhibition by the peptides. Interestingly, differential inhibition of P-selectin–mediated cell adhesion under static and rolling conditions was also observed for rPSGL-Ig, which gave full inhibition in static assays, but only enhancement of the rolling velocity under flow (Dr R. Schaub, personal oral communication, November 2001). Nevertheless, as recently shown, a 60% increase in leukocyte rolling velocity by rPSGL-Ig is sufficient to diminish leukocyte accumulation in inflamed tissue.33 In this respect, cocrystallization studies on EWVDV with P-selectin will provide unique information on strategies to enhance the avidity or specificity of selectin antagonists as has been performed for sLex.30We anticipate, based on the striking resemblance of EWVDV with PSGL-1 in terms of calcium dependency and antagonistic capacity, that EWVDV will provide a unique tool for studying the interaction of PSGL-1 with P-selectin. Studies on structures based on the N-terminal domain of PSGL-1 have shown that the sulfated peptide backbone in PSGL-1 binds to a different location on P-selectin than the sLex-containing moiety.29,30 36 Our results suggest that EWVDV interacts with the sLex site in the P-selectin C-type lectin domain, thereby precluding PSGL-1 binding. However, the structural features, specificity, high avidity, and partial calcium dependency of the peptides as compared with sLex led us to believe that the peptides are not direct, structural, mimics of sLex.

In conclusion, we describe in this paper the design of an entirely new class of small calcium-dependent P-selectin antagonists based on an EWVDV core motif. Whereas these peptide antagonists already have low micromolar avidity for P-selectin, derived tetramers display nanomolar affinity and are among the most potent synthetic ligands yet designed. These peptides provide a valuable lead for the further development of novel anti-inflammatory and antiatherothrombotic therapeutics.

We thank Jim van Dijk and Ben Appelmelk for their gift of chimeric adhesion molecules, and Piet Modderman for providing the P-selectin–transfected CHO cells. We are also grateful to Paolo Monaci (IRBM, Rome, Italy) for the use of his phage-displayed peptide libraries and to Robert Schaub (Genetics Institute) for providing recombinant PSGL-1.

T.J.M.M. and C.C.M.A. are members of the UNYPHAR project, a network collaboration between the universities of Groningen, Utrecht, Leiden, and Yamanouchi Europe.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 5, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0641.

Supported in part by grants 2000D040 and M93.001 from the Netherlands Heart Foundation (J.K. and E.A.L.B.) and by Yamanouchi Europe (C.C.M.A. and T.J.M.M.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Erik A. L. Biessen, Division of Biopharmaceutics, Leiden/Amsterdam Center for Drug Research, Leiden University, PO Box 9502, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands; e-mail: biessen@lacdr.leidenuniv.nl.

![Fig. 6. TM11 increases HL60 rolling velocities in flow chamber perfusion experiments. / The rolling of calcein-am–labeled HL60 cells over CHO-P–coated coverslips was measured by real-time video microscopy in the presence or absence of peptides. Rolling velocities were calculated from the average rolling distance per elapsed time period. Rolling velocities were significantly enhanced by almost 2-fold in the presence of 100 nM (TM11)4 and DVEWVDVS (20 μM) compared with their controls [(Biotin)4 and DEAVDVS, respectively;P < .01]. Values represent means of rolling velocities of at least 20 cells in 3 separate experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/10/10.1182_blood-2002-02-0641/4/m_h82223404006.jpeg?Expires=1765154103&Signature=dUNH8b3rLNyZd8nVCyebYcn3MRdcdwdCK2ENnmNvZBgqMsK3RO0VdzDzcdlfRK-lufKtpePj7GBhr3Jw8UDv52eyWWkeuBqxSvh3rVohx0rzS2Ak86ibKxkAlpUBpd11jWoSJYOikxZHdwXPy5m92HFe1DtYgBjUcvpXyFPWoLdLSwEB-NUPSU2NSfEYzujU09J2ah3EVEveHQ2YEikF~fPTQ9EMKdzP-nMx2V5SujDLR8fA2aVMILjpWrNK5qXZBmlzXj0ZXqr8BmdNc4aDnlEie-13ebG9CE5GWP02AANoR1mzDAeuZooKRaO6xZd~4xQJBZ~9YZ-WC-49sJGedg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. TM11 increases HL60 rolling velocities in flow chamber perfusion experiments. / The rolling of calcein-am–labeled HL60 cells over CHO-P–coated coverslips was measured by real-time video microscopy in the presence or absence of peptides. Rolling velocities were calculated from the average rolling distance per elapsed time period. Rolling velocities were significantly enhanced by almost 2-fold in the presence of 100 nM (TM11)4 and DVEWVDVS (20 μM) compared with their controls [(Biotin)4 and DEAVDVS, respectively;P < .01]. Values represent means of rolling velocities of at least 20 cells in 3 separate experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/10/10.1182_blood-2002-02-0641/4/m_h82223404006.jpeg?Expires=1765163501&Signature=XtAM0PgrHPkk4dy0IxQL8GERzp-5-2NH71dOKIOrMX5QeSwaKyyByG~ZPpGYghSeEBG6Uaa4WAMZbPuQ1qmzYwhPwPcKgX~EEjE85oeq3ilARHp0~lA4E7X4a37QVd34Ts0jJenJw5Sau06wG7f~jLm-jOPuu~SGZUwZpmCxnQJXXDHnjqdHUn4TemVJ3p4cO9phx4yMf3xrSMdJMuYjWakXpJtEpn7We5sBXda5kmtaJc5rqLYIE7RtZonSY8g5GKYtzXjhg3R2Uwg1X34HFLPjvmAExTODDYFIMNn9PSzILEUv4Z53q0Ec4vY5mK8UwbmHZKodIqlya2YwnszNGw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)