Key Points

This article provides a defined GMP-grade medium and erythroid culture protocol, resulting in >90% enucleated RBC.

This article provides a high-resolution database of RNA expression dynamics at daily intervals during terminal erythroid differentiation.

Abstract

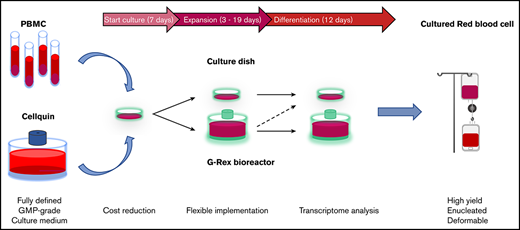

Transfusion of donor-derived red blood cells (RBC) is the most common form of cellular therapy. Donor availability and the potential risk of alloimmunization and other transfusion-related complications may, however, limit the availability of transfusion units, especially for chronically transfused patients. In vitro cultured, customizable RBC would negate these concerns and further increase precision medicine. Large-scale, cost-effective production depends on optimization of culture conditions. We developed a defined medium and adapted our protocols to good manufacturing practice (GMP) culture requirements, which reproducibly provided pure erythroid cultures from peripheral blood mononuclear cells without prior CD34+ isolation, and a 3 × 107-fold increase in erythroblasts in 25 days (or from 100 million peripheral blood mononuclear cells, 2 to 4 mL packed red cells can be produced). Expanded erythroblast cultures could be differentiated to CD71dimCD235a+CD44+CD117−DRAQ5− RBC in 12 days. More than 90% of the cells enucleated and expressed adult hemoglobin as well as the correct blood group antigens. Deformability and oxygen-binding capacity of cultured RBC was comparable to in vivo reticulocytes. Daily RNA sampling during differentiation followed by RNA-sequencing provided a high-resolution map/resource of changes occurring during terminal erythropoiesis. The culture process was compatible with upscaling using a G-Rex bioreactor with a capacity of 1 L per reactor, allowing transition toward clinical studies and small-scale applications.

Introduction

Blood transfusion is the most applied cellular therapy, with >80 million transfusion units administered worldwide each year.1 Inherent risks of donor-transfusion material are alloimmunization and presence of bloodborne diseases. Oxygen-carrier substitutes have shown to be applicable in case of immediate emergency but cannot replace long-term blood transfusions.2 The potential to culture red blood cells (RBC) for transfusion purposes has long been recognized.3-10 Transfusion medicine and the care of chronic transfusion patients with prophylactic antigen matching has already substantially decreased the rate of alloimmunization (<5%). There are many variables that result in alloimmunization, including access to centers that are molecularly typing both donors and recipients to precisely match the unit to the patient. Cultured RBC (cRBC) that are antigen-compatible will decrease the risk of alloimmunization in patients. Cost-effective, large-scale culture of blood group–matched RBC will provide a degree of donor independency and minimization of donor-patient blood type variation. In addition, cRBC can be used as vehicles for enzyme replacement therapy11 or as therapeutic delivery systems targeting specific body parts.12 Several groups have already cultured enucleated cRBC from cord blood CD34+ cells.13-15 However, these cells produce fetal hemoglobin (Hb) with a higher tendency to denature and to cause membrane damage compared with adult Hb.16 We have previously shown that enucleated cRBC can be generated starting from adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), a better accessible source than cord blood CD34+ cells, and allows adult autologous cRBC.17 Importantly, the erythroid yield from PBMC is increased 10- to 15-fold compared with CD34+ cells isolated from a similar amount of PBMC because of support from CD14+ cells present in PBMC.17-19

One transfusion unit contains about 2 × 1012 RBC, reflecting the high requirement for erythroblast expansion to obtain sufficient numbers of cRBC. Previous attempts to culture the required number of enucleated cRBC from CD34+ cells isolated from PBMC were hampered by low expansion or poor enucleation.20,21 Expansion of CD71highCD235adim erythroblasts can be prolonged by exploiting the cooperative action of erythropoietin (EPO), stem cell factor (SCF), and glucocorticoids involved in stress-erythropoiesis in a serum/plasma-free environment,7,17,18,22,23 whereas differentiation is induced by increasing concentrations of EPO and dispensing with SCF and glucocorticoids. Here, we describe a 3-stage good manufacturing practice (GMP)–grade culture protocol using culture dishes or G-Rex bioreactors, both with high expansion and enucleation to generate PBMC-derived cRBC. To this end, we have developed a completely defined GMP-grade medium. This 3-stage culture protocol can be used for small-scale GMP-grade production, yielding >90% enucleated reticulocytes with adult hemoglobinization.

Material and methods

Cell culture

Human PBMC from whole blood were purified by density separation using Ficoll-Paque (per manufacturer’s protocol). Informed consent was given in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Dutch National and Sanquin Internal Ethic Boards. PBMC were seeded at 5 to 10 × 106 cells/mL (CASY Model TCC; Schärfe System GmbH, Reutlingen, Germany) in Cellquin medium based on HEMA-Def7,17 with significant modification (supplemental Table 1 lists all components) supplemented with EPO (2 U/mL; ProSpec, East Brunswick, NJ), human recombinant stem cell factor (100 ng/mL; ITK Diagnostics BV, Uithoorn, The Netherlands), dexamethasone (Dex; 1 μM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and 0.1% human ultra-clean albumin (cHA; kindly provided by Sanquin Plasma Products, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; perturbation with albumin, see supplemental Methods and material), referred to as expansion medium (EM). Interleukin-3 was added (1 ng/mL; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) to EM on the first day (stage 1). Media was partially replenished every 2 days with EM. Around day 6, upon erythroblast detection, the cells were maintained 1 to 2 × 106 cells/mL for 15 to 25 days (stage 2). Erythroblasts differentiation (stage 3) was induced in differentiation medium (DM) containing Cellquin supplemented with EPO (10 U/mL), 5% Omniplasma (Octopharma, Wien, Austria), holotransferrin (700 µg/mL; Sanquin), and heparin (5 U/mL; LEO Pharma BV, Breda, The Netherlands). At day 2, half of a medium change was performed. At day 5, storage components (Sanquin Plasma Products) were added and media was refreshed (half) every 2 days until fully differentiated at days 10 through 12 of differentiation. For reticulocyte filtration see supplemental Methods and material.

Flow cytometry

Cells were washed and resuspended in N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid buffer supplemented with 1% human albumin (HA). Cells were incubated with primary antibodies for 30 minutes at 4°C, measured on FACS Canto II or LSRFortessa (both BD Biosciences, Oxford, United Kingdom) and analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo v10, Ashland, OR). Reticulocyte RNA was stained with thiazole orange (Sigma) as described previously (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Antibodies are listed in supplemental Methods and material).

RBC deformability

RBC deformability was measured by the Automated Rheoscope and Cell Analyzer as described previously.24 A 10-Pa shear stress was used and 3000 cells were measured and grouped in 30 bins according to increasing elongation or cell projection area (as a measure of membrane surface area). Both the extent of elongation (major cell radius divided by minor cell radius) and the area (in square millimeters) was plotted against the normalized frequency of occurrence.

HPLC

Culture lysates were prepared and stored at −80°C before analysis as described previously.24 In short, Hb separation was performed by high-performance cation exchange liquid chromatography (HPLC) on Alliance 2690 equipment (Waters, Milford, MA) using 30 minutes of elution over a combined 20 to 200 mM NaCl and pH 7.0 to 6.6 gradient in 20 mM BisTris/HCl and 2 mM KCN. A PolyCAT A 100/4.6 mm, 3 mm, 1500Å column (PolyLC, Columbia, MD) was used.

Coomassie

Ghosts (RBC membranes) were generated as described before,25 subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and total proteins were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. In short, proteins were fixed in 30% ethanol, 2% (v/v) phosphoric acid overnight, washed 2 times for 10 minutes in 2% phosphoric acid and equilibrated for 30 minutes in 2% phosphoric acid containing 18% ethanol and 15% (wt/v) ammonium sulfate. Gels were stained by diluting Coomassie Blue G-250 dissolved in water (0.2%) slowly to a final concentration of 0.02% (0.2 mg/mL).

Cytospins

Cells were cytospun using Shandon Cytospin II (Thermo Scientific), dried, and fixed in methanol. Cells were stained with benzidine in combination with the Differential Quick Stain Kit (PolySciences, Warrington, PA) (per manufacturer’s protocol). Slides were dried, subsequently embedded in Entellan (Merck-Millipore), and covered with a coverslip. Images were taken using microscope DM2500 with ×40 or ×10 object (Leica DM-2500; Germany).

RNA-sequencing analysis

Erythroid cultures on differentiation medium were sampled daily for 12 days. Sequencing libraries were prepared using Trizol RNA isolation, complementary DNA amplification, and ribosomal RNA depletion using HyperPrep Kit with RiboErase (KAPA Biosystems, Pleasanton, CA) as described by the manufacturer. Reads were mapped to ChGR38.v85 and differential expression analysis was performed with EdgeR.26 A detailed description can be found in supplemental Methods and material.

Results

Large-scale erythroblast expansion from PBMC using a G-Rex bioreactor and GMP-grade medium

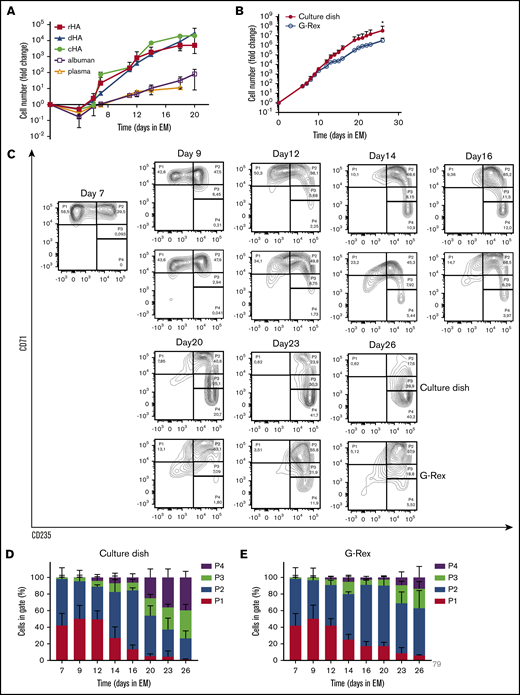

To establish medium conditions to obtain and prolong erythroid expansion from adult PBMC, we first tested distinct sources of albumin. Different EM (supplemental Table 1) with 0.1% cHA, 2.5% plasma, 2.5% Albuman, 0.1% detoxified Albuman (dHA), or 0.1% recombinant HA (rHA) were used (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1). Plasma or Albuman resulted in (1) low erythroblast yield, (2) presence of non-erythroid cells (negative for CD71 and CD235), and (3) premature differentiation of erythroblasts, indicated by a loss of CD71 expression in conjunction with increased CD235a expression (supplemental Figure 1A).27,28 In contrast, EM supplemented with cHA, dHA, or rHA showed a significantly increased erythroid expansion potential with limited spontaneous differentiation and a complete absence of nonerythroid cells (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1). Of note, PBMC contain primarily T cells, myeloid cells, and B cells and only on average 0.16% CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells that are capable of differentiating into erythroid cells.17,19 Therefore, expansion curves using PBMC as a starting material show a drop in expansion between day 0 and day 5, caused by a loss of these nonproliferating immune effector cells.17,18 By consequence, a fold change increase of erythroid cells from PBMC of ∼105-fold corresponds to an ∼108-fold increase from the CD34+ cell compartment.

Efficient expansion of erythroblasts in plasma/serum-free GMP-grade medium. (A) PBMC were cultured toward erythroblasts in GMP-grade medium supplemented with EPO, SCF, and Dex (EM) for 26 days. Medium was prepared using either cHA, dHA, rHA, Albuman, or plasma. Cell counts at day 0 were normalized to 1 PBMC at the start of culture. Cultures were kept at 0.7 to 2 × 106 by dilution. Symbols indicate mean fold-change at any day compared with 1 PBMC seeded, error bars indicate standard deviation (SD) (n = 4). (B) PBMC from 4 independent donors were cultured from PBMC in Cellquin medium (cHA) supplemented with EPO (2 U/mL), SCF (100 ng/mL), and Dex (1 μM) in culture dishes until a pure erythroblast population was obtained (at day 7). Erythroblasts were further expanded in a G-Rex bioreactor or in culture dishes. Mean fold-change (± SD) was calculated and compared (2-way analysis of variance, *P < .05; n = 4). (C) Representative density plots indicating cell surface expression levels of CD71 and CD235 in cultures as described in panel B. Quadrants are labeled (P1-P4) and relative cell numbers per quadrant indicated as (D-E) percentage quantification of percentages per quadrant in dot blots similar to those shown in panel C. Error bars indicate SD (n = 4). (D) Cells cultured in dishes. (E) Cells cultured in G-Rex.

Efficient expansion of erythroblasts in plasma/serum-free GMP-grade medium. (A) PBMC were cultured toward erythroblasts in GMP-grade medium supplemented with EPO, SCF, and Dex (EM) for 26 days. Medium was prepared using either cHA, dHA, rHA, Albuman, or plasma. Cell counts at day 0 were normalized to 1 PBMC at the start of culture. Cultures were kept at 0.7 to 2 × 106 by dilution. Symbols indicate mean fold-change at any day compared with 1 PBMC seeded, error bars indicate standard deviation (SD) (n = 4). (B) PBMC from 4 independent donors were cultured from PBMC in Cellquin medium (cHA) supplemented with EPO (2 U/mL), SCF (100 ng/mL), and Dex (1 μM) in culture dishes until a pure erythroblast population was obtained (at day 7). Erythroblasts were further expanded in a G-Rex bioreactor or in culture dishes. Mean fold-change (± SD) was calculated and compared (2-way analysis of variance, *P < .05; n = 4). (C) Representative density plots indicating cell surface expression levels of CD71 and CD235 in cultures as described in panel B. Quadrants are labeled (P1-P4) and relative cell numbers per quadrant indicated as (D-E) percentage quantification of percentages per quadrant in dot blots similar to those shown in panel C. Error bars indicate SD (n = 4). (D) Cells cultured in dishes. (E) Cells cultured in G-Rex.

Large-scale cRBC production in culture dishes is practically impossible; therefore, a G-Rex bioreactor from Wilson Wolf Manufacturing (Saint Paul, MN) was used in which a gas-permeable membrane at the bottom allowed proliferation in larger volume/surface conditions.29,30 The G-Rex bioreactor does not support adherent cells, such as the CD14+ PBMC that promote erythroid yield by increasing CD34+ cell survival,18 which compromises stage 1 yield (data not shown). Therefore, PBMC cultures were started in culture dishes/cell stacks until an erythroblast population was obtained around day 7 of culture in EM supplemented with cHA. Subsequently (stage 2), cultured erythroblasts were either transferred to G-Rex systems or retained in culture dishes and could be maintained for at least 26 days (Figure 1B). Transfer to a G-Rex bioreactor briefly delayed erythroid expansion but showed a similar expansion rate between days 15 and 25. Although the G-Rex bioreactor yielded slightly fewer cells (3 × 106 vs 3 × 107), less donor variation was observed. Erythroid cells can be staged from CD71highCD235dim erythroblasts (P1) to enucleated CD71−CD235+ reticulocytes (P4), with intermediate stages in which cells are characterized by increased CD235a and reduced CD71 expression (Figure 1C).28 At day 7, no nonerythroid cells (CD71−CD235−) were observed, indicating a pure erythroid culture (day 0 to day 7 culture progression was previously published by our laboratory18 ). During erythroblast expansion in stage 2, erythroblasts gained expression of CD235a from day 10 onwards, resulting in a pure population of CD71highCD235+ erythroblasts that could be expanded for at least 26 days (Figure 1C-E; supplemental Figure 1A). Previously, we showed that these CD71highCD235+ erythroblasts, cultured in the presence of Epo/SCF/Dex, express low levels of Hb and have a morphology overlapping proerythroblasts and basophilic erythroblasts. When using the general term “erythroblasts” in this manuscript, we are indicating this stage. Expansion of erythroblasts in EM medium limits their differentiation to CD71low polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts to a small fraction of cells that escapes the differentiation block. During prolonged culture in EM, spontaneously differentiating cells accumulate (Figure 1C-E). Interestingly, cells expanded in the G-Rex system maintained a less differentiated state for a prolonged culture period (>16 days), as shown by delayed CD235a upregulation and maintenance of high CD71 expression (Figure 1E). In conclusion, a defined GMP-grade medium enabled pure erythroblast cultures from a mixed PBMC cell pool with significantly delayed onset of spontaneous differentiation, resulting in a large expansion potential in both culture dishes and a G-Rex bioreactor.

Erythroid cultures from G-Rex and normal culture dishes fully enucleate

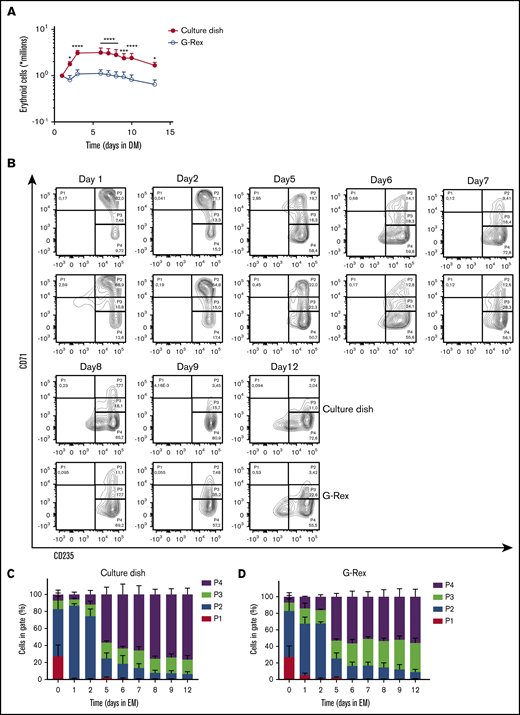

Differentiation of erythroblasts to polychromatic erythroblasts, orthochromatic erythroblasts, and eventually to enucleated reticulocytes (stage 3) is induced by removing SCF and Dex while increasing the EPO and holo-transferrin concentration and supplementing with 5% Omniplasma. Heparin is added to prevent the medium from clotting (DM). Erythroblast differentiation is characterized by (1) a transient proliferation burst with decreased cell-cycle time resulting in a reduced cell volume; (2) hemoglobinization; (3) erythroid specific protein expression of, for example, blood group antigens; and (4) enucleation.13,17,27,28,31 During the first days of differentiation, in particular in culture dishes, proliferation was observed followed by cell growth arrest (Figure 2A). Note that the number of cells after the initial short proliferation burst did not decrease, suggesting no negative effect on culture viability. In contrast, cells differentiated in a G-Rex bioreactor did not show increased expansion. During erythroblast differentiation, both erythroid cells cultured in dishes and the G-Rex system increased expression of CD235a and lost expression of CD71, although erythroblasts differentiated slightly faster in culture dishes (Figure 2B-D). Differentiation was accompanied with a decrease in cell size (forward scatter area). Both CD71 and c-KIT (CD117) expression increased at day 1, followed by a sharp downregulation (supplemental Figure 2A-B). Furthermore, CD44 was progressively reduced in expression as reported previoulsy.17 Although CD235 expression increases in early differentiation, as cells become smaller, it decreases slightly, which may be due to loss of membrane surface during enucleation.

Differentiation of erythroblasts in culture dishes or a G-Rex bioreactor. (A) Erythroblast cultures were established in culture dishes. Erythroblasts were washed and reseeded at 1 × 106/mL in Cellquin medium supplemented with EPO (10 U/mL), Transferrin (700 μg/mL), 5% human plasma, and heparin (5 U/mL) (DM) in culture dishes (closed symbol) or G-Rex (open symbol). Erythroblasts were differentiated for 12 days. Cell density was measured at days indicated. Mean cell numbers were calculated. Error bars indicate SD Cell expansion was compared by 2-way analysis of variance; *P < .05, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001; n = 4. (B) Representative density plots indicate cell surface expression levels of CD71 and CD235 in cultures as described in panel A. Quadrants are labeled (P1-P4) and relative cell numbers per quadrant indicated as (C-D) percentage quantification of percentages per quadrant in dot blots similar to those shown in panel C. Error bars indicate SD (n = 4). (C) Cells cultured in dishes. (D) Cells cultured in G-Rex.

Differentiation of erythroblasts in culture dishes or a G-Rex bioreactor. (A) Erythroblast cultures were established in culture dishes. Erythroblasts were washed and reseeded at 1 × 106/mL in Cellquin medium supplemented with EPO (10 U/mL), Transferrin (700 μg/mL), 5% human plasma, and heparin (5 U/mL) (DM) in culture dishes (closed symbol) or G-Rex (open symbol). Erythroblasts were differentiated for 12 days. Cell density was measured at days indicated. Mean cell numbers were calculated. Error bars indicate SD Cell expansion was compared by 2-way analysis of variance; *P < .05, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001; n = 4. (B) Representative density plots indicate cell surface expression levels of CD71 and CD235 in cultures as described in panel A. Quadrants are labeled (P1-P4) and relative cell numbers per quadrant indicated as (C-D) percentage quantification of percentages per quadrant in dot blots similar to those shown in panel C. Error bars indicate SD (n = 4). (C) Cells cultured in dishes. (D) Cells cultured in G-Rex.

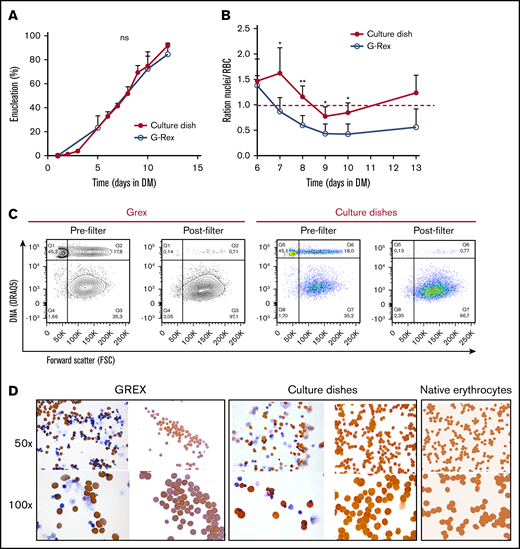

Factors that affect enucleation at the end of erythroid differentiation

At blood banks, RBC are stored in media that contain specific components protecting viability, which were not present in DM. Therefore, a specific storage component solution was added at day 5 of differentiation, when the first reticulocytes arose in culture. This increased the number and frequency of enucleated cRBC, particularly in the G-Rex bioreactor (data not shown). Nonetheless, initial differentiation experiments in the G-Rex system yielded low numbers of enucleated cells compared with culture dishes (supplemental Figure 3A). Importantly, EM is completely replaced by DM upon initiating differentiation in dishes, whereas only 90% EM could be replaced with DM in the G-Rex system. Indeed, replacing 90% of the culture medium in dishes resulted in a reduction of enucleation, compared with complete medium replacement (56% vs 85%; supplemental Figure 3B). Reduction of Dex (from 1 µM to 10 nM) 2 days before differentiation induction did not affect enucleation (supplemental Figure 3D). However, SCF removal from the culture medium 2 days before differentiation in culture dishes increased enucleation 1.5-fold (56% vs 85%; supplemental Figure 3C). This indicated that residual SCF at the start of differentiation negatively affects enucleation during terminal differentiation. Enucleation was observed from day 5 onwards, resulting in >90% enucleation after 12 days of differentiation in culture dishes and almost 85% enucleation in the G-Rex system (Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 3E). A slight difference in the ratio nuclei/cRBC between culture dishes and a G-Rex bioreactor was observed (Figure 3B). The flow cytometry data and cytospin images at the end of differentiation revealed pyrenocytes (nuclei encapsulated by plasma membrane) and some nucleated cells (Figure 3C-D; supplemental Figure 3E). Filtration using neonatal leukoreduction filters resulted in 99% removal of nuclei and remaining nucleated cells and yielded a homogenous population of enucleated cRBC that is comparable to native erythrocytes on cytospin (Figure 3C-D). Of note, these cRBC resemble late reticulocytes populations as previously observed by us.19,32

Efficient enucleation is observed after 10 days in differentiation medium. (A-C) Enucleated cells and nuclei were measured by flow cytometry, using DRAQ5 DNA staining against size (forward scatter) as shown in panel C. (A) The percentage of enucleated erythroid cells was measured during differentiation in culture dishes (closed symbols) and a G-Rex system (open symbols). Error bars indicate SD (n = 4). Comparisons were made by unpaired Student t test. (B) Ratio of nuclei vs cRBC during differentiation in culture dishes or G-Rex (<1 means more cRBC than nuclei). Mean ± SD (unpaired Student t test, *P < .05, **P < .01; n = 3-4). (C) Enucleation percentages of 10 days differentiated erythroid cultures before and after passage through a leukoreduction filter. Q1, nuclei; Q2, nucleated cells; Q3+Q4, enucleated cRBC. (D) Cytospins of the samples analyzed in panel C stained for hemoglobin with benzidine and general cytological stains. As comparison, cytospins of native peripheral blood erythrocytes are shown.

Efficient enucleation is observed after 10 days in differentiation medium. (A-C) Enucleated cells and nuclei were measured by flow cytometry, using DRAQ5 DNA staining against size (forward scatter) as shown in panel C. (A) The percentage of enucleated erythroid cells was measured during differentiation in culture dishes (closed symbols) and a G-Rex system (open symbols). Error bars indicate SD (n = 4). Comparisons were made by unpaired Student t test. (B) Ratio of nuclei vs cRBC during differentiation in culture dishes or G-Rex (<1 means more cRBC than nuclei). Mean ± SD (unpaired Student t test, *P < .05, **P < .01; n = 3-4). (C) Enucleation percentages of 10 days differentiated erythroid cultures before and after passage through a leukoreduction filter. Q1, nuclei; Q2, nucleated cells; Q3+Q4, enucleated cRBC. (D) Cytospins of the samples analyzed in panel C stained for hemoglobin with benzidine and general cytological stains. As comparison, cytospins of native peripheral blood erythrocytes are shown.

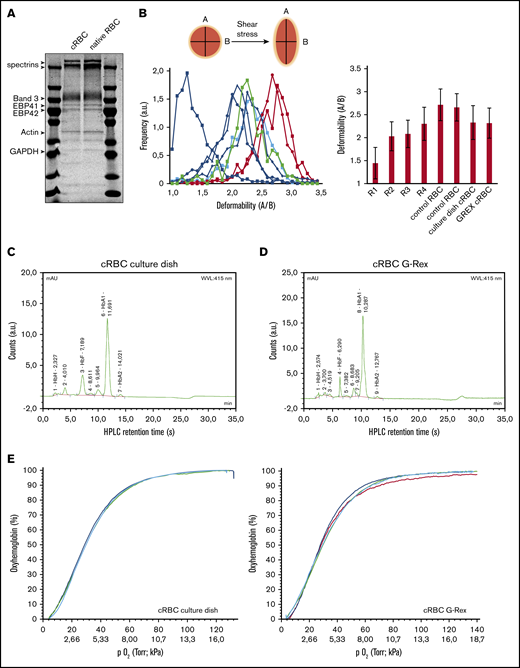

cRBC resemble mature reticulocytes

Filtered cRBC displayed a spheroid morphology, indicative of a reticulocyte population (Figure 3C). Expression of the major membrane proteins α/β-spectrin, Band 3, protein 4.1, protein 4.2, and GAPDH were comparable between cRBC from culture dishes and peripheral blood RBC (Figure 4A). Reticulocytes released from the bone marrow have a low deformability, which increases during maturation toward RBC.33 Both cRBC cultured in culture dishes and the G-Rex system showed a deformability index comparable to late peripheral blood reticulocytes (Figure 4B). Furthermore, cell pellets from cRBC turned dark red and HPLC data showed that cRBC both derived from G-Rex and culture dishes mainly express adult Hb (HbA1 73.4% G-Rex vs 62% dish; HbA2 2.1% G-Rex vs 1.4% dish) and low levels of HbF (8.8% G-Rex vs 7.1% dish; Figure 4C-D). In addition, hemoglobin oxygen association and dissociation rates of cRBC and peripheral blood RBC were similar at variable oxygen pressure (Figure 4E). Blood group expression of the cRBC was assessed by flow cytometry and compared with the original donor RBC. Blood group expression was in complete agreement with the original donors (Table 1). The functional similarities between cRBC and peripheral blood RBC indicate that the 3-stage culture model using culture dishes or a G-Rex bioreactor yields functional enucleated erythroid cells.

cRBC are highly similar to donor RBC. (A) Ghosts from cRBC and peripheral blood RBC were lysed and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Gel was stained with Coomassie and depicts the most abundant proteins in RBC membranes. (B) Deformability of cRBC was measured under shear stress by the Automated Rheoscope and Cell Analyzer, which elongates cells and measures length over width as deformability parameter. Progressively maturating reticulocytes were isolated from peripheral blood (in order of maturation: R1, RNAhighCD71high; R2, blue squares; RNAhighCD71low, R3, blue circles; RNAhighCD71−, blue triangles; R4: RNAlowCD71−, blue diamonds; as described previously24 ) were compared with fully mature RBC (red curves) and filtered cRBC from normal culture dishes (thick green line) or the G-Rex bioreactor (thick blue line). Right bar graph represents the quantification of >1000 cells per culture condition. (C-D) Expression of hemoglobin variants was determined by HPLC in cRBC in culture dishes before filtering (C) or G-Rex after filtering (D). Hemoglobin variants are indicated; exact retention time is indicated for each peak. (E) Oxygen association and dissociation curve for peripheral blood RBC (teal and red) and cRBC cultured in a G-Rex bioreactor (blue and green). The percentage oxygenated hemoglobin is measured at a gradient of oxygen tension given in Torr (upper line x-axes) and kPa (lower line x-axes).

cRBC are highly similar to donor RBC. (A) Ghosts from cRBC and peripheral blood RBC were lysed and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Gel was stained with Coomassie and depicts the most abundant proteins in RBC membranes. (B) Deformability of cRBC was measured under shear stress by the Automated Rheoscope and Cell Analyzer, which elongates cells and measures length over width as deformability parameter. Progressively maturating reticulocytes were isolated from peripheral blood (in order of maturation: R1, RNAhighCD71high; R2, blue squares; RNAhighCD71low, R3, blue circles; RNAhighCD71−, blue triangles; R4: RNAlowCD71−, blue diamonds; as described previously24 ) were compared with fully mature RBC (red curves) and filtered cRBC from normal culture dishes (thick green line) or the G-Rex bioreactor (thick blue line). Right bar graph represents the quantification of >1000 cells per culture condition. (C-D) Expression of hemoglobin variants was determined by HPLC in cRBC in culture dishes before filtering (C) or G-Rex after filtering (D). Hemoglobin variants are indicated; exact retention time is indicated for each peak. (E) Oxygen association and dissociation curve for peripheral blood RBC (teal and red) and cRBC cultured in a G-Rex bioreactor (blue and green). The percentage oxygenated hemoglobin is measured at a gradient of oxygen tension given in Torr (upper line x-axes) and kPa (lower line x-axes).

Blood group analysis of peripheral blood RBC and cRBC using flow cytometry

| Blood group . | RBC 1 . | RBC 2 . | RBC 3 . | cRBC 1 . | cRBC 2 . | cRBC 3 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | — | — | + | — | — | + |

| B | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| RhD | + | + | — | + | + | — |

| RhE | — | + | — | — | + | — |

| RhC | + | — | — | + | — | — |

| Rhe | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Rhc | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| K | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| k | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Kp-a | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Kp-b | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lu-a | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Lu-b | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| P1 | + | — | + | + | — | + |

| S | + | — | — | + | — | — |

| s | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Fya | + | — | + | + | — | + |

| Fyb | — | + | + | — | + | + |

| Jka | — | + | — | — | + | — |

| Jkb | + | — | + | + | — | + |

| M | + | — | + | + | — | + |

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Blood group . | RBC 1 . | RBC 2 . | RBC 3 . | cRBC 1 . | cRBC 2 . | cRBC 3 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | — | — | + | — | — | + |

| B | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| RhD | + | + | — | + | + | — |

| RhE | — | + | — | — | + | — |

| RhC | + | — | — | + | — | — |

| Rhe | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Rhc | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| K | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| k | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Kp-a | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Kp-b | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lu-a | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Lu-b | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| P1 | + | — | + | + | — | + |

| S | + | — | — | + | — | — |

| s | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Fya | + | — | + | + | — | + |

| Fyb | — | + | + | — | + | + |

| Jka | — | + | — | — | + | — |

| Jkb | + | — | + | + | — | + |

| M | + | — | + | + | — | + |

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + |

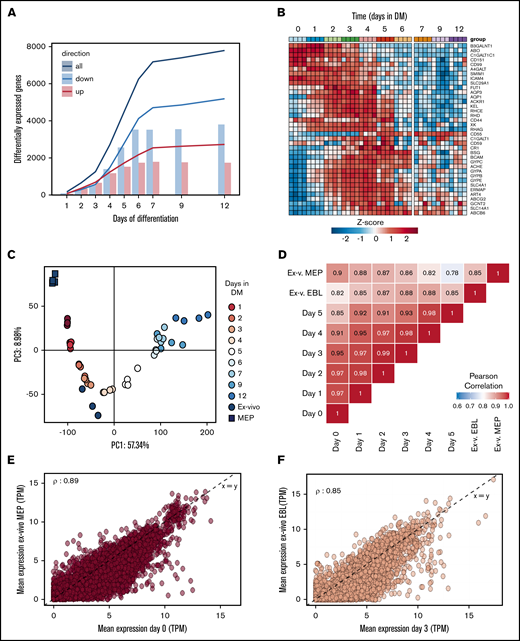

Terminal differentiation of erythroblasts to enucleated reticulocytes completely changes the transcriptome

Differentiation of nonhemoglobinized erythroid progenitor cells to functional enucleated cells involves significant changes in morphology, cell volume, and protein content. Identification of regulatory processes is crucial to enhance and optimize the production and the yield of in vitro erythropoiesis. A comparison of the in vitro transcriptome to existing databases of in vivo transcriptomes allows to benchmark the in vitro differentiation process. Differentiation was started from CD117+CD71+CD235−/dimCD44high early erythroblast populations (phase 3, day 0) from 4 distinct donors and daily RNA samples were collected until terminal enucleation state at day 12 (95%; changes in surface marker expression in supplemental Figure 2). In reference to the early erythroblast population (day 0), 75% of the analyzed transcripts changed during differentiation (7792 transcripts with a false discovery rate < 0.01 and fold-change >4) with 5189 downregulated, 2726 upregulated, and 124 that were transiently up- or downregulated (Figure 5A; supplemental Table 2). These major transcriptome alterations occurred primarily during the first 6 days (phase 3). The expression of transcripts encoding proteins crucial for the function and immunological properties of RBC can be scrutinized. Figure 5B shows that RNA expression of different blood group antigen bearing proteins from these donors is differentially regulated over time. In addition, globin subunit expression dynamics indicated rapid hemoglobinization during the first 72 hours of differentiation coinciding with increased CD71 expression. Note that expression of β globin subunits is significantly higher compared with γ globins (supplemental Figure 5A). cKIT RNA was rapidly downregulated and CD235 (GPA) rapidly upregulated, in agreement with flow cytometry results (supplemental Figure 5A). In line with the major transcriptional changes over the course of differentiation, principal component analysis captured ∼57% of variance in the 2000 most variable genes. The first component associated with differentiation progression, sequentially grouping samples from subsequent days (Figure 5C). Cultured RBC showed good functional and morphological correspondence with in vivo RBC (Figure 4). This raised the question how the cultured cells would compare with ex vivo cells at the transcriptome level. Comparing published transcriptomes of bone marrow megakaryoid/erythroid progenitors (CD38+CD34+CD10−CD45RA−CD123−CD90−) and CD71+CD235+ erythroblasts34 to in vitro cultured erythroid cells revealed that the ex vivo MEP grouped before the sequence of cultured cells, while the CD71+CD235+ grouped along with the cultured cells, with the same marker expression (supplemental Figure 4B). Note that the in vitro cultures showed little variation between donors, indicating a reproducible synchronized differentiation process. Ex vivo cells showed relatively more variation in the principal component analysis, which may be a consequence of the more broadly expressed erythroid surface markers used to isolate these cells. The major differences between cultured and ex vivo cells accounted for 18% of the variance (supplemental Figure 5A). Still, Pearson correlation between samples using all differentially expressed genes indicated that ex vivo MEP were most similar to erythroblasts cultured under expansion conditions (day [d]0) whereas ex vivo CD235+CD71+ erythroblasts were most similar to d3 differentiated polychromatic erythroblasts (ρ = 0.89 and ρ = 0.85, respectively; Figure 5D). Direct comparison of RNA expression between the ex vivo MEP and d0 erythroid cells, and of the CD235+CD71+ ex vivo erythroblast and d3 differentiated cells showed comparable transcript levels (Figure 5E-F). Overall, the main difference between cultured and freshly isolated cells originates from genes that were predominantly expressed at increased levels in cultured cells compared with ex vivo cells (supplemental Table 3). Of note, transcripts with increased expression in cultured cells were further downregulated upon differentiation progression in line with decreased expression observed in the more asynchronous ex vivo erythroid cells (supplemental Figure 4B). Removing the low expression filter also revealed a set of 380 genes expressed at lower levels in cultured cells that consisted of pseudogenes and transcripts encoding mitochondrial or ribosomal proteins (supplemental Table 4), probably reflecting a difference in technical processing of samples. The similarities in the transcriptome of cultured cells and the related stage in vivo indicates that close recapitulation of transcriptional changes is at the basis of the functional and morphological characteristics of the cultured erythroid cells.

RNA expression profiles during in vitro erythroid differentiation are similar to ex vivo isolated erythroid precursors. RNA was isolated at subsequent days of differentiation to identify changes in the transcriptome (4 independent donors). (A) Bars represent the number of transcripts that are up- (red) or downregulated (blue) each day in reference to the start of the culture (false discovery rate <0.01 and log fold change >2, or <−2). Lines reflect cumulative number of unique genes differentially expressed over the time course. (B) Heatmap of z-transformed expression values (log2-CPM) for all genes encoding for blood group antigens and or blood group bearing moieties. (C) The transcriptome of MEP (black squares) and CD71highCD235high erythroblasts (black circles) isolated from bone marrow was compared with the transcriptome of differentiating cRBC using principle component analysis (PC1 vs PC3). (D) A Pearson correlation matrix of all samples used in panels A-C. Mean transcript levels (transcripts per million mapped reads) were compared between MEP and cRBC d0 (E) and between freshly isolated erythroblasts and cRBC d3 (F).

RNA expression profiles during in vitro erythroid differentiation are similar to ex vivo isolated erythroid precursors. RNA was isolated at subsequent days of differentiation to identify changes in the transcriptome (4 independent donors). (A) Bars represent the number of transcripts that are up- (red) or downregulated (blue) each day in reference to the start of the culture (false discovery rate <0.01 and log fold change >2, or <−2). Lines reflect cumulative number of unique genes differentially expressed over the time course. (B) Heatmap of z-transformed expression values (log2-CPM) for all genes encoding for blood group antigens and or blood group bearing moieties. (C) The transcriptome of MEP (black squares) and CD71highCD235high erythroblasts (black circles) isolated from bone marrow was compared with the transcriptome of differentiating cRBC using principle component analysis (PC1 vs PC3). (D) A Pearson correlation matrix of all samples used in panels A-C. Mean transcript levels (transcripts per million mapped reads) were compared between MEP and cRBC d0 (E) and between freshly isolated erythroblasts and cRBC d3 (F).

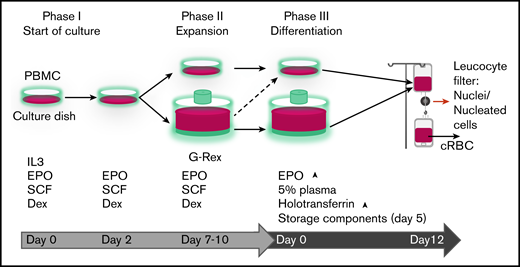

Discussion

Widescale clinical application of cRBC is faced by several constraints, such as the inability to generate large cell numbers that are required, the high costs of ill-defined media, and the low yield of enucleated, biconcave cRBC.35 The culture protocol presented here challenges these constraints by boosting advances with respect to high enucleation rates, matching erythroid characteristic at different levels, and redefining medium composition and maximum expansion without the necessity to first isolate CD34+ cells (Figure 6). Using a defined medium and exploiting stress erythropoiesis, we achieve 107-fold erythroblasts expansion within 26 days. Despite starting from total PBMC, pure erythroid cultures expressing CD71 and CD235adim are obtained validating the GMP-grade medium, yielding similar cell numbers as previously reported using commercial Stemspan media.17,18 Using total PBMC not only allows outgrowth of all CD34+ progenitors, but also CD34− hematopoietic progenitors present in blood that have the capacity to differentiate toward erythroid cells.17,18 Glucocorticoids are essential for stress erythropoiesis in the mouse and synergy of glucocorticoids with EPO and SCF induces erythroblasts proliferation while inhibiting differentiation.7,23,31,36,37 The addition of glucocorticoids also supports erythropoiesis by differentiating peripheral blood monocytes or CD34+ cells to erythroid supporting macrophages during culture from PBMC, further increasing the erythroid yield.19,38 In contrast to our plasma/serum-free expansion, many large-scale red cell culture protocols use glucocorticoid agonists in combination with serum and/or plasma during expansion. Here, we showed that the addition of plasma causes premature differentiation of erythroblasts also in the presence of glucocorticoids.9,10,13,39,40 Increased spontaneous differentiation upon addition of plasma during erythroblast expansion may be due to additional growth factors or other plasma components. Optimal expansion in absence of plasma/serum is important to reach the amount of cRBC required for transfusion, but also to establish erythroid cultures from small blood aliquots of specific anemic patients. We have recently shown that 3 mL of blood is sufficient to culture enough cells to reprogram erythroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSC).41 In addition to direct use, the expanded erythroblast can be frozen and defrosted without loss of expansion potential (data not shown), similar to what we previously reported for starting cultures from frozen PBMC.42 This introduces flexibility concerning actual production of products (eg, with the generation of IPSC form cryopreserved patient material).43-45 The use of adult PBMC also facilitates the availability of starting material and introduces the possibility to culture autologous cRBC. This is important considering alloimmunization caused by blood group mismatches and matching from cord blood–derived RBC may be complicated in either conventional transfusion or with novel therapeutic blood products. The culture process was compatible with up-scaling for clinical studies and applications using a G-Rex bioreactor. The G-Rex bioreactor allowed for 3 × 106-fold expansion per PBMC (∼1 × 109-fold from CD34+ cells in these PBMC; taken the accepted 0.16% of CD34+ cells present in total PBMCs18 ). Of note, we have submitted cells that have been expanded for 10 days and the maximum of 25 days to DM and found that enucleation and differentiation progression is unperturbed (data not shown). Remaining nuclei and enucleated cells after differentiation could be efficiently removed using a leukoreduction filter, as generally used by blood banks, to obtain a pure cRBC population. The total costs of 1 5 L GREX producing ∼4.5 mL GMP-grade cRBC from 100 million PBMC (roughly 80 mL of blood) is ∼28 000 euros and would take 27 days (15 days of EM and 12 days of DM). Of note, it would take roughly 36 days (24 days of EM and 12 days of DM) to culture a transfusion unit starting from 100 million PBMCs. Two of the major challenges, besides bioreactor development, that need to be tackled are (1) reducing prices of major cost drivers and (2) increasing the efficiency of filters because currently ∼30% of cRBC can be recovered from the leukocyte filters. Costs can be significantly reduced if specific major cost drivers were to be produced in a bulk recombinant manner (eg, growth factors). For instance, the recombinant GMP-grade SCF, 1 of the major cost drivers in our protocol, presently is ∼3500 times more expensive compared with insulin. Exchange of human albumin by novel agents such as polyvinyl alcohol that have been shown to promote HS(P)C expansion could potentially cut costs significantly.46 Also, novel cell-permeable iron chelators that could be used as replacement for transferrin may cut costs. It has been estimated that around 5 to 10 mL of erythrocytes will be needed for specific therapeutic delivery of cargo. Thus, currently the costs to produce this amount, taking a filter efficiency of 30%, would be between 80 000 and 200 000 euros. Considering expensive enzyme replacement therapies, the costs of in vitro cRBC may be competitively priced. However, it is clear that additional optimization and cost reduction is needed as well as research into loading and stability of therapeutics within the in vitro cultured cells.

Progression of erythroid cells during culture. Overview of the 3-phase erythroid culture system using culture dishes or a G-Rex bioreactor. A pure erythroblast culture is established in dishes from PBMC during the first 7 days. From day 7 erythroblasts are expanded in G-Rex or in dishes. When transferred from expansion to differentiation medium, erythroblasts in dishes or in G-Rex can mature to enucleated cells. The small remnant of nucleated cells and nuclei (pyrenocytes) can be removed by passage through a leukocyte filter. The growth factors and hormones used in culture are indicated at the lower half of the graph.

Progression of erythroid cells during culture. Overview of the 3-phase erythroid culture system using culture dishes or a G-Rex bioreactor. A pure erythroblast culture is established in dishes from PBMC during the first 7 days. From day 7 erythroblasts are expanded in G-Rex or in dishes. When transferred from expansion to differentiation medium, erythroblasts in dishes or in G-Rex can mature to enucleated cells. The small remnant of nucleated cells and nuclei (pyrenocytes) can be removed by passage through a leukocyte filter. The growth factors and hormones used in culture are indicated at the lower half of the graph.

The defined Iscove modified Dulbecco medium–based culture medium, termed Cellquin, solely contains GMP grade components and finds its basis in HEMA-def.7 Knowing the exact concentrations of all components within Cellquin now allows quantitative tracking of erythroid requirements by combining the transcriptome/proteome with metabolomics. This may help to culture cells at higher densities and to cater specific media components exclusively needing erythroid, leading to considerable cost reduction and aiding upscaling. Currently, the cost of Cellquin is lower compared with commercially available media while performing at least similarly.

One Cellquin component paramount to its effectiveness is albumin. We observed that the isolation and manufacturing process of human albumin critically influences the erythroid expansion potential. Using ultra-clean, detoxified, or recombinant additive-free HA significantly increased the erythroid expansion potential. Albumin binds substances including proteins, metabolites, and fatty acids, including toxins, drugs, and other therapeutics.47-49 Replacing ultrapure cHA in EM by Albuman reduced erythroblast expansion potential, which could be reverted by charcoal and ion exchanger treatment of Albuman. Interestingly, the process to manufacture Albuman includes a saturation step to restrain the albumin binding potential, rendering it mostly inert. This suggests that the binding and/or transport function of albumin is important to ensure continued erythroblast expansion.

The technical improvements to the culture protocol result in excellent yield of in vitro cultured erythroblasts combined with >90% enucleation, adult hemoglobin expression, correct blood group expression, deformability, and oxygen saturation dynamics similar to donor peripheral blood enucleated cells. In addition, we present the first transcriptomic analysis from erythropoiesis originating from stress-erythropoiesis cultures. Comparison of this dataset to datasets from ex vivo erythroid cells shows that, next to similarities in RBC characteristics, the cRBC are comparable to similar ex vivo cells at the transcript level. These observations together make the transcriptome dataset provided here a valuable resource to address erythroid regulatory mechanisms.

In 2011, Timmins et al demonstrated an ultra-high yield of cRBC with > 90% enucleation from cord blood-derived CD34+ cells in the absence of plasma.15 This reported erythroid yield was similar to our serum/plasma-free adult PBMC-derived erythroid expansion. However, >90% enucleation during terminal differentiation using our differentiation protocol (stage 3) was only recapitulated in presence of plasma, whereas adding 5% Omniplasma increases enucleation from 20% to 25% to more than 90% (data not shown). Whether this reflects a difference in cord blood vs adult erythroid cultures remains unknown but is important to investigate along with identifying the components in plasma that are key to this increased enucleation in our system.

Combining the advances of the presented protocol facilitates both easy implementation in other laboratories and study of erythropoiesis in healthy individuals or in patients for which limited sample volumes are available. It adds to the feasibility of using adult peripheral blood as starting material for cRBC cultures, which is an important step toward precision medicine, such as in using custom-engineered cRBC as cargo vesicles for drug delivery. In addition, the synchronized cultures contain young reticulocytes that have a theoretical lifespan of ∼120 days. Chronic anemia patients that receive blood transfusions every 2 months may benefit from transfusions with in vitro cultured long-lived RBC, potentially increasing the time between transfusions and thereby reducing the costs. Currently we are working toward a clinical trial that will allow to test the in vivo lifespan of transfused PBMC-derived cRBC.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Wilson Wolf Manufacturing (Saint Paul, MN) for providing the G-Rex bioreactors. The authors also thank Rob van Zwieten, Martijn Veldthuis, and Jeffrey Berghuis (Department of Blood Cell Research, Sanquin) for the technical assistance and data acquisition regarding the HPLC data and deformability assays, and the Central Facility of Sanquin for its assistance regarding flow cytometry analysis.

This work was supported by grants from The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (grants ZonMw-TOP, 40-00812-98-12128 [S.H.] and ZONMW-TAS, 40-41400-98-1327 [P.B., M.T.-V., and E.S.]), Landsteiner Foundation for Blood Transfusion Research (grant LSBR:1141) (E.A. and E.H.), and Sanquin (grant PPOR:15-30) (A.V.).

Authorship

Contribution: P.B., M.T.-V., E.S., E.H., S.H., E.O., E.V., and A.V. performed the experiments; E.v.d.A., E.H., and P.B. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; J.H.A.M. performed the RNA isolation and sequencing; M.v.L. contributed to the experiment design and writing of the manuscript; and all authors critically revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Emile van den Akker, Department of Hematopoiesis, Sanquin Research, Plesmanlaan 125, 1066CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: e.vandenakker@sanquin.nl.

References

Author notes

S.H., E.H., and P.B. contributed equally to this work.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

The RNA-sequencing data in this article have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE124363).