Key Points

BCL2L1 is associated with HbF gene activation.

Abstract

Fetal hemoglobin (HbF) expression is partially governed by the trans-acting quantitative trait loci BCL11A and MYB and a cis-acting locus linked to the HBB gene cluster. Our previous analysis of the Genotype-Tissue Expression database suggested that BCL2L1 was associated with HbF gene expression. In erythroid progenitors from patients with sickle cell disease, BCL2L1 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels were positively correlated with HBG mRNA and total HbF concentration (r2 = 0.72, P = .047 and r2 = 0.68, P = .01, respectively). Inhibition of BCL2L1 protein activity in HbF-expressing HUDEP-1 cells decreased HBG expression in a dose-dependent manner. Overexpression of BCL2L1 in these cells increased HBG expression fourfold (P < .05) and increased F cells by 13% (P < .05). Overexpression of BCL2L1 in erythroid progenitors derived from primary adult CD34+ cells upregulated HBG expression 11-fold (P < .05), increased F cells by 18% (P < .01), did not significantly affect cell differentiation or proliferation, and had a minor effect on survival. Although the mechanism remains unknown, our results suggest that BCL2L1 is associated with HbF gene activation.

Introduction

The γ-globin chains (HBG2 and HBG1) characterizing fetal hemoglobin (HbF) are encoded by 2 nonallelic linked genes, HBG2 and HBG1, whose polypeptides differ (136 glycine in HBG2 and 136 alanine in HBG1).1,2 Expression quantitative trait loci (QTL) can be used as a quantitative phenotype to ascertain the expression of individual genes, such as HBG2 and HBG1, and to provide insight into whether HbF QTL effect 1 or both γ-globin genes (together referred to as HBG). Using the Genotype-Tissue Expression database, we studied HBG gene expression along with the regulatory elements of these genes and the effects of genetic variations of these elements.3 In the course of these studies, pathway and correlation analysis suggested that BCL2L1 (BCLX) was a potential HbF activator. We show that BCL2L1 expression is correlated with HBG messenger RNA (mRNA) and HbF levels in erythroid progeny of CD34+ cells from patients with sickle disease. In HUDEP-1 cells, an immortalized cell line that predominantly expresses HbF,4 inhibition of BCL2L1 protein activity decreased HBG expression in a dose-dependent manner, and BCL2L1 overexpression upregulated HBG expression. In primary adult CD34+ cells obtained from normal donors, BCL2L1 overexpression upregulated HBG expression and F-cell production without affecting cell differentiation or proliferation, and it had a minor effect on survival. QTL on chromosomes 2, 6, and 11 explain 20% to 80% of HbF variation, which suggests that additional regulatory elements exist.5,,,,-10 BCL2L1 might be 1 of these regulators.

Methods

Cell lines, plasmids, antibodies, and BCL-XL inhibitor

HUDEP clone 1 was used as previously described.4 HUDEP-1 cells were expanded in StemSpan SFEM (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) supplemented with 10−6 M dexamethasone (Millipore Sigma A, St. Louis, MO), 100 ng/mL human stem cell factor (SCF; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), 3 IU/mL erythropoietin (R&D Systems), 1% l-glutamine, and 2% penicillin/streptomycin (both from Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Doxycycline (1 mg/mL; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was included in the culture to induce expression of the human papilloma virus type 16 E6/E7 genes.4,11 HUDEP-1 cells were differentiated in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 330 mg/mL holo-transferrin (Millipore Sigma A), 10 μg/mL recombinant human insulin (Life Technologies), 2 IU/mL heparin (Millipore Sigma A), 5% human plasma AB (Millipore Sigma A), 3 IU/mL erythropoietin (R&D Systems), 100 ng/mL human SCF (R&D Systems), 1 mg/mL doxycycline (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1% l-glutamine (Life Technologies), and 2% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies).4,11

293T cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with 10% FBS (both from Life Technologies).

The BCL2L1 expression vector pCDH-puro-BCL-XL was acquired from Addgene (plasmid #46972; Watertown, MA) as previously described.12 PerCP-conjugated mouse anti-human HbF, FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human CD71, PE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD235, FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human CD235, and PE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD34 antibodies were acquired from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA).

A selective and highly potent BCL-XL inhibitor A-1155663 was acquired from Millipore Sigma A.

Transfection and lentivirus production

The 293T packaging cell line was cotransfected with BCL2L1 expression plasmid pCDH-puro-BCL-XL or empty pCDH-puro vector together with TAT, REV, G/P, or VsVg using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). After 48 hours, the medium containing lentivirus was collected, filtered, and concentrated with a Lenti-X Concentrator (cat. #631231; TaKaRa).

Stable expression of BCL2L1 in HUDEP-1 cells

HUDEP-1 cells were transfected with lentivirus that contained pCDH-puro-BCL-XL or empty pCDH-puro vector control. On day 3 after infection, cells were cultured in the presence of 0.5 μg/mL puromycin in SPAM I expansion medium for 14 days to select stable BCL2L1-expressing cells. The BCL2L1-expressing or vector control cells were harvested for BCL2L1 mRNA analysis. BCL2L1-overexpressing cells were cultured in differentiation medium for 5 days, HBG mRNA was analyzed by quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), and F cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

HUDEP-1 cell treatment with BCL-XL inhibitor

HUDEP-1 cells were treated with the selective BCL-XL inhibitor A-1155663 (Millipore Sigma A) at concentrations of 0.1 nM, 1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM, and 10 μM for 24 hours in SPAM I culture medium and then switched to differentiation medium without added inhibitors for 3 days. Cells were harvested for HBG mRNA analysis by qRT-PCR. Cells were also examined for proliferation at the end of these studies.

CD34+ cells

Mononuclear cells from deidentified adult peripheral blood (Research Blood Components, Boston, MA) were isolated on Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), and CD34+ cells were purified using a CD34 MicroBead Kit Ultrapure, human (cat. #130-100-453) and MS columns (cat. #130-042-201; both from Miltenyi Biotec). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), counted, and incubated with FcR blocking reagent and CD34 MicroBeads for 30 minutes at 4°C, layered onto the prepared MACS column, and washed; CD34+ cells were eluted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Isolated CD34+ cells were cultured and expanded in StemSpan SFEM II (cat. #09605) by adding StemSpan CD34+ Expansion Supplement (cat. #02691; both from STEMCELL Technologies).

Ectopic expression of BCL2L1 in erythroid progenitors derived from adult CD34+ cells

Adult CD34+ cells were infected with lentivirus that contained pCDH-puro-BCL-XL or empty pCDH-puro vector control for 5 hours and then cultured in StemSpan SFEM II medium for 48 hours. The cells were further cultured in the presence of 0.5 μg/mL puromycin for 5 days to select BCL2L1-expressing cells and then the cells were switched to differentiation medium for 12 to 14 days. The BCL2L1-infected CD34+ cells were differentiated in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 330 mg/mL holo-transferrin (Millipore Sigma A), 10 μg/mL recombinant human insulin (Life Technologies), 2 IU/mL heparin (Millipore Sigma A), 5% human plasma AB (Millipore Sigma A), 5 IU/mL erythropoietin (R&D Systems), 50 ng/mL human SCF (R&D Systems), 1% l-glutamine (Life Technologies), and 2% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies). Erythroid progenitor differentiation was confirmed by Wright-Giemsa staining and CD71 and CD235 immunostaining. The cells were collected at day 12 of the differentiation phase for mRNA analysis and at day 14 for F-cell analysis by flow cytometry. Cell viability was assessed on days 1, 3, 7, and 14 by trypan blue staining followed by hemocytometry.

RNA preparation, complementary DNA synthesis, and reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from 4 × 105 cells using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD), following the manufacturer’s directions. First-strand complementary DNA was synthesized using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression was performed using TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Branchburg, NJ) and the ABI QuantStudio 12K Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and the ΔΔCt method was then used to process the qRT-CR data. Relative abundance of BCL2L1, HBG, HBB and HBA mRNA was determined using β-actin mRNA as an internal control. TaqMan Gene Expression primers were obtained from Life Technologies.

F-cell, CD71, and CD235 analyses

On day 14 of the differentiation phase, cultured CD34+ cell–derived erythroid progenitors or HUDEP-1 cells were analyzed for the fraction of cells expressing HbF (F cells), CD71 (transferrin receptor), or CD235a (glycophorin A) by immunofluorescent staining and flow cytometry. Cells were fixed with 3% formaldehyde (Millipore Sigma A) in PBS/0.1% bovine serum albumin for 20 minutes at room temperature and permeabilized with 0.5% saponin (Millipore Sigma A) in PBS/0.1% bovine serum albumin for 10 minutes. Following washing, cells were stained for 30 minutes with a PerCP-conjugated mouse anti-human HbF antibody or a PerCP mouse isotype control (BD Biosciences). The samples were analyzed on a BD FACSCalibur using CellQuest software (both from BD Biosciences). The fraction of F cells was determined by setting gates based on unstained isotype controls and compared between vector control cells and BCL2L1-expressing cells.

Cells were also stained with PE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD235a and FITC-conjugated anti-human CD71 antibodies and PE or FITC mouse isotype control (BD Biosciences) to determine the maturation of erythroid progenitor cells.

Cells were double stained with PerCP-conjugated mouse anti-human HbF antibody and FITC-conjugated anti-human CD235a antibody, or PerCP and FITC mouse isotype control (BD Biosciences) to determine the fraction of F cells in the CD235a+ population.

Giemsa staining and differentiation curve

At days 1, 7, and 14 of differentiation, CD34 cells were fixed with methanol and stained with Wright-Giemsa. The enucleated cells were counted, and the enucleation ratio was calculated. Cells were photographed using an Olympus microscope.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using a paired Student t test. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Gene expression in CD34+ cells from sickle cell anemia

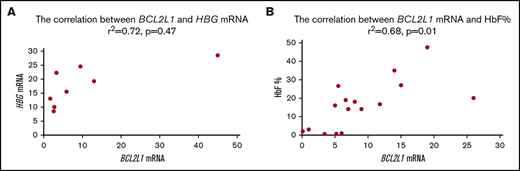

BCL2L1 and HBG mRNA expression levels were correlated from CD34+ cells acquired from 8 patients with sickle cell anemia13,-15 (r2 = 0.72, P = .047; Figure 1A). BCL2L1 mRNA and HbF levels were correlated from CD34+ cells acquired from 15 patients with sickle cell anemia (r2 = 0.68, P = .01; Figure 1B).

BCL2L1 mRNA levels were positively correlated with HBG mRNA and HbF protein.BCL2L1 mRNA was positively correlated with HBG mRNA (r2 = 0.72, P = .047) from 8 patients with sickle cell anemia.13,-15 (A) and with HbF protein (r2 = 0.55, P = .04) from 15 patients with sickle cell anemia13,-15 (B).

BCL2L1 inhibition by a selective small molecular inhibitor decreased HBG gene expression and ectopic expression of BCL2L1 increased HBG gene expression and F-cell production in HUDEP-1 cells

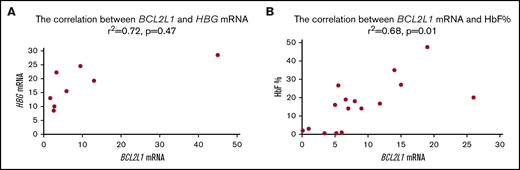

In HUDEP-1 cells treated with A-1155663, a selective and highly potent BCL-XL inhibitor, there was a dose-dependent decrement in HBG expression (Figure 2A), from 30% inhibition at 0.1 nM to 80% inhibition at 10 μm. HBG expression in HUDEP-1 cells is 300-fold that of HBB expression (Figure 2A). We did not detect a significant inhibition of HBB expression at A-1155663 concentrations of 0.1 nM to 100 nM (Figure 2A), but minor inhibition was detected at concentrations of 1 μM and 10 μM. BCL2L1 overexpression in HUDEP-1 cells increased mRNA levels sixfold and HBG mRNA levels 4.3-fold; F cells increased by 13% (Figure 2B-C). Cell proliferation was not affected by inhibitor concentrations up to 100 nM (Figure 2D) or by the ectopic expression of BCL2L1 (Figure 2E), suggesting that the effects on HBG expression were unrelated to cell proliferation in culture.

BCL2L1 regulates HBG gene expression and F-cell production in HUDEP-1 cells. HUDEP-1 cells were treated with the selective BCL-XL inhibitor at the indicated concentrations for 24 hours and then switched to differentiation medium, without added inhibitors, for 3 days. Cells were harvested for HBG mRNA analysis by qRT-PCR and examined for proliferation at the end point of these studies. (A) Effects of BCL-XL inhibitor on HBG and HBB expression. BCL-XL inhibitor suppressed HBG expression in a dose-dependent manner; mRNA was normalized to β-actin (n = 3) (left panel). BCL-XL inhibitor on HBB expression; mRNA was normalized to β-actin (n = 3) (right panel). (B) BCL2L1 ectopic expression upregulated HBG gene expression (n = 3). (C) BCL2L1 ectopic expression increased F-cell production (n = 3; upper panel). Representative flow cytometric analysis of F cells (lower panels). Effect of BCL-XL inhibitor (D) and BCL2L1 ectopic expression (E) on HUDEP-1 cell proliferation (n = 3). *P < .05.

BCL2L1 regulates HBG gene expression and F-cell production in HUDEP-1 cells. HUDEP-1 cells were treated with the selective BCL-XL inhibitor at the indicated concentrations for 24 hours and then switched to differentiation medium, without added inhibitors, for 3 days. Cells were harvested for HBG mRNA analysis by qRT-PCR and examined for proliferation at the end point of these studies. (A) Effects of BCL-XL inhibitor on HBG and HBB expression. BCL-XL inhibitor suppressed HBG expression in a dose-dependent manner; mRNA was normalized to β-actin (n = 3) (left panel). BCL-XL inhibitor on HBB expression; mRNA was normalized to β-actin (n = 3) (right panel). (B) BCL2L1 ectopic expression upregulated HBG gene expression (n = 3). (C) BCL2L1 ectopic expression increased F-cell production (n = 3; upper panel). Representative flow cytometric analysis of F cells (lower panels). Effect of BCL-XL inhibitor (D) and BCL2L1 ectopic expression (E) on HUDEP-1 cell proliferation (n = 3). *P < .05.

Ectopic expression of BCL2L1 in primary CD34+ cells increased HBG gene expression and F-cell production

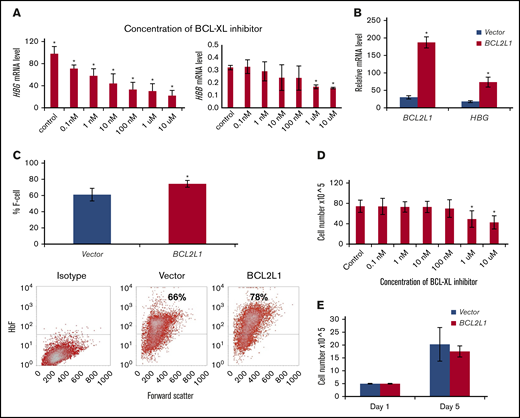

CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors were transfected with BCL2L1-expressing lentivirus and induced to erythroid differentiation for 2 weeks. The HBG mRNA level was significantly induced by BCL2L1 overexpression (Figure 3A); the BCL2L1 mRNA level was induced 57-fold (P = .03), and the HBG mRNA level was induced 11-fold (P = .05) (Figure 3A). There was a threefold and twofold induction of HBB and HBA, but these changes were not significant (P = .12 and .24, respectively; Figure 3B). By flow cytometric analysis, F cells increased 19% from vector control cells (P = .01; Figure 3C), and they increased 16% from the GlyA+ population in a double staining with HbF and GlyA antibodies (P = .01; Figure 3D).

BCL2L1 regulates HBG gene expression and F-cell production in erythroid progenitors derived from adult CD34+cells. (A) BCL2L1 ectopic expression upregulated HBG gene expression. BCL2L1 and HBG mRNA were normalized to β-actin (n = 3). (B) BCL2L1 predominantly regulated HBG, with a minor effect on HBB and HBA. BCL2L1, HBG, HBB, and HBA mRNA in BCL2L1-overexpressed and vector-expressed cells was normalized to β-actin, and the fold changes in BCL2L1, HBG, HBB, and HBA mRNA are shown (n = 3). (C) BCL2L1 ectopic expression increased F-cell production (n = 3; upper panel). Representative flow cytometric analyses of F cells (lower panels). (D) BCL2L1 ectopic expression increased F-cell production from the CD235 population (n = 3; upper panel). Representative flow cytometric analyses of HbF and CD235 double staining (lower panels). *P < .05, **P < .01.

BCL2L1 regulates HBG gene expression and F-cell production in erythroid progenitors derived from adult CD34+cells. (A) BCL2L1 ectopic expression upregulated HBG gene expression. BCL2L1 and HBG mRNA were normalized to β-actin (n = 3). (B) BCL2L1 predominantly regulated HBG, with a minor effect on HBB and HBA. BCL2L1, HBG, HBB, and HBA mRNA in BCL2L1-overexpressed and vector-expressed cells was normalized to β-actin, and the fold changes in BCL2L1, HBG, HBB, and HBA mRNA are shown (n = 3). (C) BCL2L1 ectopic expression increased F-cell production (n = 3; upper panel). Representative flow cytometric analyses of F cells (lower panels). (D) BCL2L1 ectopic expression increased F-cell production from the CD235 population (n = 3; upper panel). Representative flow cytometric analyses of HbF and CD235 double staining (lower panels). *P < .05, **P < .01.

Effects on erythroid progenitor cell differentiation, cell proliferation, and survival

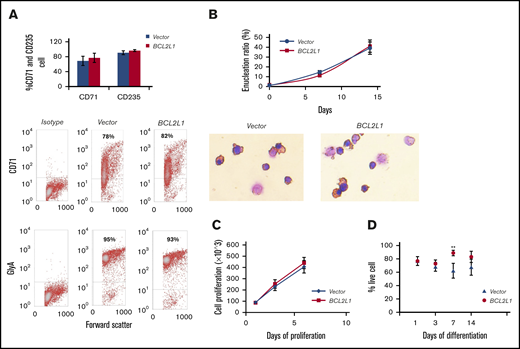

Following BCL2L1 overexpression, there was no significant change in CD235 and CD71 expression level, as assessed by flow cytometry analysis (Figure 4A) and no significant change in enucleated cell number during differentiation when assessed by Wright-Giemsa staining (Figure 4B). This suggested that differentiation might not be a major factor in BCL2L1-mediated HBG gene expression and F-cell induction.

Effect of BCL2L1 overexpression on cell differentiation, proliferation, and survival. (A) Effect of BCL2L1 ectopic expression on CD71 and CD235 expression (n = 3; upper panel). Representative flow cytometric analyses of CD71 and GlyA (lower panels). (B) Effect of BCL2L1 ectopic expression on cell enucleation during differentiation (n = 3; upper panel). Representative images of Wright-Giemsa staining (lower panels, original magnification ×40). (C) Effect of BCL2L1 ectopic expression on erythroid progenitor cell proliferation. The BCL2L1- or vector only–expressing CD34+ cells were cultured in StemSpan SFEM II medium, and cell numbers were counted at days 1, 3, and 6 (n = 3). (D) Effect of BCL2L1 ectopic expression on erythroid progenitor cell survival during the differentiation. BCL2L1- or vector only–expressing CD34+ cells were cultured in differentiation medium. Cells stained with trypan blue were counted and the percentages of live cells are shown (n = 4). **P < .01.

Effect of BCL2L1 overexpression on cell differentiation, proliferation, and survival. (A) Effect of BCL2L1 ectopic expression on CD71 and CD235 expression (n = 3; upper panel). Representative flow cytometric analyses of CD71 and GlyA (lower panels). (B) Effect of BCL2L1 ectopic expression on cell enucleation during differentiation (n = 3; upper panel). Representative images of Wright-Giemsa staining (lower panels, original magnification ×40). (C) Effect of BCL2L1 ectopic expression on erythroid progenitor cell proliferation. The BCL2L1- or vector only–expressing CD34+ cells were cultured in StemSpan SFEM II medium, and cell numbers were counted at days 1, 3, and 6 (n = 3). (D) Effect of BCL2L1 ectopic expression on erythroid progenitor cell survival during the differentiation. BCL2L1- or vector only–expressing CD34+ cells were cultured in differentiation medium. Cells stained with trypan blue were counted and the percentages of live cells are shown (n = 4). **P < .01.

BCL2L1 overexpression did not cause a significant change in cell proliferation at days 1, 3, and 6 of culture (Figure 4C). The survival of adult erythroid progenitors was estimated at days 1, 3, 7, and 14 of differentiation. Although survival increased 1.2-fold at day 7 when BCL2L1 was overexpressed compared with the vector-only control (P = .004), on other days there were no significant changes (Figure 4D). These results suggest that BCL2L1 had no adverse effects on cell proliferation and only a small effect on survival of CD34+ cell–derived erythroid progenitors during differentiation in culture.

Discussion

Pathway and correlation analysis using the Genotype-Tissue Expression database showed an unexpected association of BCL2L1 (BCLX; 20q11.21) with HbF gene expression.3 To further explore this result, we used immortalized human erythroid cells expressing HbF, erythroid progenitors derived from primary human CD34+ cells that primarily express adult hemoglobin, and CD34+ cells from patients with sickle cell anemia to study the relationships between BCL2L1 and HBG expression and HbF. We show that overexpression of BCL2L1 in CD34+ erythroid progenitors upregulated HBG expression 11-fold and increased F-cell production (Figure 3), inhibition of BCL2L1 activity in HUDEP-1 cells resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in HBG expression (Figure 2A), BCL2L1 mRNA levels were positively correlated with HBG mRNA and HbF levels in patients with sickle cell anemia (Figure 1A-B), and erythroid cell differentiation and proliferation appeared to be unaffected (Figure 4A-C) and the effect on erythroid cell survival was minor (Figure 4D).

BCL2L1 is a member of the BCL-2 gene family and has 2 major protein isoforms (BCL-XL and BCL-XS) that are the result of alternative splicing. It is capable of homodimerization and heterodimerization with other members of the BCL-2 family. BCL-XL is antiapoptotic, whereas BCL-XS is proapoptotic.16,17 BCL-XL induces erythroid cell differentiation and is involved in erythroid lineage fate decision.18,-20 BCL-XL–deficient mice showed apoptosis of liver hematopoietic cells.21 BCL-XL prevents ineffective erythropoiesis due to apoptosis in late-stage hemoglobin-synthesizing erythroblasts.22 The BCL2L1 promoter contains various transcription factor binding motifs, including 1 for GATA-1, a regulator of many erythroid genes. Induction of BCL2L1 expression by erythropoietin and GATA-1 was critical for the survival of late proerythroblasts and early normoblasts, suggesting some role in erythropoiesis.23,-25

Despite the role of BCL2L1 in regulating differentiation, apoptosis, and cell survival, our in vitro studies showed that BCL2L1 overexpression had little effect on cell differentiation and proliferation (Figure 4A-C), with only a minor increase in cell survival at day 7 of differentiation (Figure 4D). This suggests that BCL2L1-mediated modulation of HBG gene expression might not be a result of changes in erythroid cell differentiation or survival. At this point in our studies, we cannot exclude the possibility that BCL2L1 regulates progenitor cell survival in vivo during stages when HBG is primarily expressed or that it might extend the lifespan of F cells. We also cannot exclude the possibility that BCL2L1 interacts with other proteins involved in regulating HBG expression. Further studies are needed to confirm the relationship between BCL2L1 and HBG and to define the mechanism through which BCL2L1 is associated with activation of HBG expression. It is possible that this could lead to the discovery of new drug targets or small molecules to induce HbF in β hemoglobinopathies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL068970, RC2HL101212, R01HL87681 [M.H.S.]; T32HL007501 [E.M.S.]; and R01HL133350 [G. Murphy and M.H.S., principal investigators]) and National Cancer Institute (R21CA141036) (Y.D.), as well as by the Evans Foundation (Y.D.).

Authorship

Contribution: Y.D., P.S., J.J.F., D.H.K.C., and M.H.S. supervised the research and wrote and edited the manuscript; Y.D. and E.M.S. conceived the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; and J.P., C.A.W., L.Y.L., and M.R.W. performed experiments.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yan Dai, Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine, EBRC 427, 650 Albany St, Boston, MA 02118; e-mail: yandai@bu.edu.