Reconstitution of T-cell immunity after bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is often delayed, resulting in a prolonged period of immunodeficiency. Donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) has been used to enhance graft-versus-leukemia activity after BMT, but the effects of DLI on immune reconstitution have not been established. We studied 9 patients with multiple myeloma who received myeloablative therapy and T-cell–depleted allogeneic BMT followed 6 months later by infusion of lymphocytes from the same donor. DLI consisted of 3 × 107 CD4+ donor T cells per kilogram obtained after in vitro depletion of CD8+ cells. Cell surface phenotype of peripheral lymphocytes, T-cell receptor (TCR) Vβ repertoire, TCR rearrangement excision circles (TRECs), and hematopoietic chimerism were studied in the first 6 months after BMT and for 1 year after DLI. These studies were also performed in 7 patients who received similar myeloablative therapy and BMT but without DLI. Phenotypic reconstitution of T and natural killer cells was similar in both groups, but patients who received CD4+ DLI developed increased numbers of CD20+ B cells. TCR Vβ repertoire complexity was decreased at 3 and 6 months after BMT but improved more rapidly in patients who received DLI (P = .01). CD4+ DLI was also associated with increased numbers of TRECs in CD3+ T cells (P < .001) and with conversion to complete donor hematopoiesis (P = .05). These results provide evidence that prophylactic infusion of CD4+ donor lymphocytes 6 months after BMT enhances reconstitution of donor T cells and conversion to donor hematopoiesis as well as promoting antitumor immunity.

Introduction

Although allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) provides potentially curative therapy for patients with a variety of hematologic malignancies, previous studies have documented prolonged periods of cellular immunodeficiency following transplantation.1-3 This prolonged period of immunodeficiency places patients at high risk for infection with opportunistic organisms and often results in significant morbidity and mortality.4,5 Many aspects of T-cell function have been examined after allogeneic BMT.4,6,7 These studies have documented a variety of cellular defects in B- and T-cell function that gradually improve after transplantation.8-13 These functional deficiencies often persist for long periods after recovery of phenotypically normal numbers of B and T cells in peripheral blood. For example, several studies have demonstrated that 1 to 2 years are required for the reconstitution of a normal T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire in patients who receive myeloablative therapy.14-16 Reconstitution of a normal T-cell repertoire may occur more rapidly in children who have higher levels of thymic function, and this observation suggests that it may be possible to develop methods for enhancing functional T-cell recovery after allogeneic BMT.8,17 18

In patients with hematologic malignancies, reconstitution of normal allogeneic stem cells is also associated with the development of immunity to residual tumor cells that have not been eliminated by the transplantation preparative regimen.19,20 The effectiveness of this graft-versus-tumor response has been demonstrated by the high response rates observed in patients who receive donor lymphocyte infusions (DLIs) for treatment of relapse after allogeneic BMT. Responses occur most often in patients with chronic myelocytic leukemia (CML),21,22 but patients with multiple myeloma and B-cell lymphoma also frequently respond to single infusions of donor lymphocytes without additional therapy.23-26 The most significant toxicity associated with DLI is the development of graft versus host (GVH) disease. Recent clinical trials have suggested that the incidence and severity of GVH disease can be reduced by in vitro depletion of CD8+ T cells from the DLI product.23,27,28 Importantly, graft-versus-leukemia activity appears to be maintained with infusion of defined numbers of CD4+ donor cells. Although the immunologic targets of the antileukemia response have not yet been well defined, previous studies have demonstrated profound immunologic effects of CD4+ DLI in patients who respond to this treatment.29-31 These immunologic effects have included increased levels of T-cell differentiation from hematopoietic stem cells, which results in increased diversity of the TCR repertoire.30 32

The immunologic effects of DLI in patients with relapsed disease suggested that DLI might provide a general method for enhancing cellular immune function following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. We therefore examined reconstitution of cellular immunity in a cohort of 9 patients with multiple myeloma who received prophylactic infusion of CD8-depleted donor lymphocytes and compared these results to a group of 7 similar patients who did not receive DLI. All patients received myeloablative therapy followed by infusion of CD6 T-cell–depleted donor bone marrow (BM) from HLA-identical siblings.33 Patients who received prophylactic DLI received a single infusion of CD4+ T cells (3 × 107/kg) from the same donor 6 months after BMT. In patients with persistent disease after transplantation, CD4+ DLI resulted in further reductions in tumor burden. Analysis of peripheral blood lymphocytes revealed no significant differences in the numbers of circulating CD3+ T cells, but patients who received DLI developed increased numbers of CD20+ B cells. CD4+ DLI was also associated with increased levels of T-cell neogenesis and more rapid reconstitution of the TCR repertoire. CD4+ DLI was also associated with conversion of mixed chimerism to complete donor hematopoiesis. Taken together, these results suggest that, in addition to specifically enhancing antitumor immunity, prophylactic infusion of CD4+ donor cells can provide a method for generally improving reconstitution of T-cell immunity after allogeneic BMT. Further studies can now be undertaken to examine the potential clinical utility of this approach.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patient treatment and preparation of patient samples

Blood and marrow samples were obtained after informed consent from healthy donors and patients enrolled on clinical trials of allogeneic stem cell transplantation. All patients received myeloablative therapy followed by infusion of marrow stem cells from HLA-identical sibling donors. Nine patients with multiple myeloma received CD6+ T-cell–depleted marrow followed by prophylactic infusion of CD8-depleted lymphocytes from the same donor 6 months after marrow transplantation.33 These 9 patients received a defined dose of CD3+CD4+ DLI as previously described.23 33 Five patients with multiple myeloma and 2 patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma received myeloablative therapy and infusion of CD6+ T-cell–depleted marrow from HLA-identical sibling donors without subsequent DLI. Clinical protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, and informed consent was obtained from each patient. Heparinized blood samples from patients were obtained after BMT and at various times after CD4+ DLI. Individual samples from 7 healthy donors were also studied. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll/Hypaque, cryopreserved with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide, and stored in vapor phase liquid nitrogen until the time of analysis.

Flow cytometry analysis

PBMCs (3 × 105-5 × 105) were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with fluorescein- or phycoerythrin-conjugated monoclonal antibodies specific for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD20, CD16, and CD56 (Beckman Coulter, Hialeah, FL). Isotype- and fluorochrome-matched irrelevant monoclonal antibodies were used as a negative control. After incubation, cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline and stored in the dark until analysis. Flow cytometry was performed on a Coulter EPICS XL (Beckman Coulter). A minimum of 10 000 cellular events were acquired, and data were analyzed using EXPO software (Beckman Coulter).

RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and polymerase chain reaction

RNA was extracted from 10 × 106 PBMCs using RNeasy Mini Kit (Quiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. First-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was generated from 2 μg total RNA using random hexanucleotides (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology, Piscataway, NJ) and reverse transcriptase (Superscript, GIBCO, Gaithersburg, MD). Each TCR Vβ segment was amplified with one of the 24 Vβ subfamily-specific primers previously described and a Cβ primer recognizing both Cβ1 and Cβ2 regions.29 34 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of Vβ5 and Vβ13 required the use of 2 sets of primers to identify the entire Vβ subfamily. The Cβ primer was conjugated to fluorescent dye 6-FAM (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for CDR3 size analysis.

TCR Vβ CDR3 size analysis

The size distribution of each TCR Vβ CDR3 fluorescent PCR product was determined by electrophoresis on an automated 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) using 4% polyacrylamide gels, and data were analyzed by GeneScan software (Perkin Elmer Cetus Instruments, Emeryville, CA). A normal transcript size distribution, reflecting polyclonal cDNA, contains 8 to 10 peaks for each Vβ subfamily.35 The appearance of dominant peaks indicates the presence of excess cDNA of identical size, suggesting the presence of oligoclonal or clonal T-cell populations.

Analysis of hematopoietic chimerism

Genomic DNA was extracted from 2 × 106 PBMCs using Wizard Genomic DNA Purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Prior to amplification, all DNA samples were quantified by UV spectrophotometry and diluted to working concentrations. Genomic DNA was extracted from samples of each donor-recipient pair before transplantation and amplified by PCR with a panel of 7 primer pairs specific for polymorphic microsatellite regions to identify an informative locus. The previously described primer sequences are designated as B7, H10, H12, H4, 3p2, pi, and CAR.15,36,37 The 3′ primer of each pair was conjugated to fluorescent 6-FAM or Hex dye (Genosys Biotechnologies, The Woodlands, TX). PCR conditions included an initial denaturation of the DNA template at 94°C for 5 minutes, followed by denaturation at 94°C for 60 seconds, primer annealing at 55°C for 60 seconds, and primer extension at 72°C for 60 seconds for 40 cycles.30 A final 10-minute extension at 72°C followed the last cycle. Aliquots of the PCR products were electrophoresed on an automated 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) using 4% polyacrylamide gel and analyzed by GeneScan software (Perkin Elmer Cetus Instruments). To quantify the donor-recipient ratio in patient samples, results were compared with standards derived from amplification of different mixtures of donor and recipient DNA (ranging from 90:10 to 10:90).

TCR rearrangement excision circles

To detect signal-joint TCR rearrangement excision circles (TRECs), a real-time quantitative PCR method was used.32 38 This method utilizes a fluoresceinated probe that hybridizes between the PCR primers. Each PCR reaction was performed in a 50 μL volume containing 0.09 μg genomic DNA, 1 × Taqman buffer A (Perkin Elmer Cetus Institute), 3 mM MgCl2, 300 nM each primer, 100 nM probe, 200 nM dATP, 200 nM DCTP, 200 nM DGTP, 400 nM dUTP, 17 units UNG, and 2 units AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin Elmer). The PCR primer sequences were sense 5′-CGTGAGAACGGTGAATGAAGAGCAGACA-3′, antisense 5′-CATCCCTTTCAACCATGCTGACACCTCT-3′. The probe sequence was 5′-VIC-TTTTTGTAAAGGTGCCCACTCCTGTGCACGGTGA-TAMRA-3′. A series of standard dilutions of plasmid containing the signal-joint breakpoint was used to quantitate TRECs in each patient and control DNA sample. By comparing the PCR cycle at which fluorescence was first significantly elevated above background (the CT or threshold cycle) in a patient sample relative to the standard curve of known concentration of the plasmid, it was possible to accurately quantitate the starting copy number of TRECs in the sample. Each patient and control DNA sample was run in duplicate on a 96-well plate along with the dilution series of the TREC plasmid. The same samples were also run on the same plate with established primers and probes for GAPDH. The GAPDH copy number served as a control for both the quality and amount of genomic DNA in the sample.

Statistical analysis

Univariate analyses were done using the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney rank sum test to compare median cell counts, change in cell counts, and complexity scores between those patients who received DLI and those who did not receive DLI at each time point. The Fisher exact test was used to compare the percent of patients who returned to the normal complexity score and the percent of patients who converted to complete donor chimerism over the first 18 months following BMT. The normal complexity score was defined as 137.6, the 95% lower confidence interval of scores for the 7 healthy donors.15 The median time to complete donor chimerism was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between the 2 groups using the Gehan Wilcoxon statistic. A mixed model using an autoregressive correlation structure and the method of restricted maximum likelihood39 was fit to account for repeated measures over time for the absolute cell counts, change in cell counts, complexity score, and change from baseline in the log (base 10)–transformed number of TREC copies per 105 CD3+ T cells. Those samples with TREC values lower than the limit of detection were set equal to the limit of detection (100 copies per 105CD3+ cells)

Results

Patient characteristics

Nine patients with multiple myeloma received myeloablative therapy followed by infusion of BM from HLA-identical siblings and infusion of CD4+ lymphocytes from the same donor 6 months later (Table1). The median age was 47 years (range, 43-54 years). Eight patients received total body irradiation (14 Gy) and cyclophosphamide (120 mg/kg), and 1 patient received cyclophosphamide (120 mg/kg) plus busulfan (16 mg/kg). In each case, donor marrow was depleted of CD6+ T cells as previously described, and patients did not receive prophylactic immunosuppressive therapy after BMT.40 None of these patients developed greater than grade 1 acute GVH disease after BMT. At the time of transplantation, 7 patients were in partial response (PR) and 2 were in complete remission (CR). Prior to DLI 6 months after BMT, 2 patients had evidence of progressive disease, 3 were in PR, 2 had stable disease, and 2 were in CR. After DLI, all 7 patients with evidence of disease demonstrated evidence of a further response.33Five patients achieved CR, and 2 demonstrated a further PR. Two patients in CR before DLI remained in CR.

Clinical characteristics of patients who received DLI

| Patient no. . | Age, y, at BMT/sex . | BMT conditioning regimen . | Disease status at BMT . | GVH disease stage after BMT . | BM CD3+ cells per kilogram infused . | DLI CD4+ cells per kilogram infused . | Disease status before DLI . | Disease status after DLI . | Acute GVH disease stage after DLI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54/M | CTX/TBI | PR | 1 | 0.30 × 106 | 3 × 107 | PD | CR | 2 |

| 2 | 50/M | CTX/TBI | PR | 0 | 0.19 × 106 | 3 × 107 | PR | CR | 1 |

| 3 | 46/M | CTX/TBI | PR | 1 | 2.70 × 106 | 3 × 107 | PR | CR | 3 |

| 4 | 49/F | CTX/TBI | PR | 1 | 0.30 × 106 | 3 × 107 | SD | PR | 0 |

| 5 | 47/F | CTX/TBI | CR | 0 | 0.11 × 106 | 3 × 107 | PD | CR | 0 |

| 6 | 42/M | CTX/TBI | CR | 0 | 3.30 × 106 | 3 × 107 | CR | CR | 0 |

| 7 | 43/F | CTX/TBI | PR | 0 | 0.20 × 106 | 3 × 107 | SD | PR | 3 |

| 8 | 51/M | CTX/TBI | PR | 0 | 0.09 × 106 | 3 × 107 | CR | CR | 3 |

| 9 | 46/F | CTX/BUS | PR | 0 | 0.67 × 106 | 3 × 107 | PR | CR | 3 |

| Patient no. . | Age, y, at BMT/sex . | BMT conditioning regimen . | Disease status at BMT . | GVH disease stage after BMT . | BM CD3+ cells per kilogram infused . | DLI CD4+ cells per kilogram infused . | Disease status before DLI . | Disease status after DLI . | Acute GVH disease stage after DLI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54/M | CTX/TBI | PR | 1 | 0.30 × 106 | 3 × 107 | PD | CR | 2 |

| 2 | 50/M | CTX/TBI | PR | 0 | 0.19 × 106 | 3 × 107 | PR | CR | 1 |

| 3 | 46/M | CTX/TBI | PR | 1 | 2.70 × 106 | 3 × 107 | PR | CR | 3 |

| 4 | 49/F | CTX/TBI | PR | 1 | 0.30 × 106 | 3 × 107 | SD | PR | 0 |

| 5 | 47/F | CTX/TBI | CR | 0 | 0.11 × 106 | 3 × 107 | PD | CR | 0 |

| 6 | 42/M | CTX/TBI | CR | 0 | 3.30 × 106 | 3 × 107 | CR | CR | 0 |

| 7 | 43/F | CTX/TBI | PR | 0 | 0.20 × 106 | 3 × 107 | SD | PR | 3 |

| 8 | 51/M | CTX/TBI | PR | 0 | 0.09 × 106 | 3 × 107 | CR | CR | 3 |

| 9 | 46/F | CTX/BUS | PR | 0 | 0.67 × 106 | 3 × 107 | PR | CR | 3 |

CTX indicates cyclophosphamide; BUS, busulfan; TBI, total body irradiation; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; and CR, complete response.

Seven patients (5 with multiple myeloma and 2 with non-Hodgkin lymphoma) received similar myeloablative therapy followed by infusion of CD6 T-cell–depleted marrow from HLA-identical sibling donors. These patients did not receive prophylactic DLI after BMT. Clinical characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table2. The total number of CD3+cells per kilogram infused was similar in both groups. However, 2 patients in the no-DLI group developed significant GVH disease after BMT. Patient no. 10 relapsed 9 months after BMT and was excluded from further immunologic analysis after this time.

Clinical characteristics of patients without DLI

| Patient no. . | Disease . | Age, y, at BMT/sex . | BMT conditioning regimen . | Disease status at BMT . | BM CD3+ cells per kilogram infused . | Disease status after BMT . | Acute GVH disease stage after BMT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | MM | 45/M | CTX/BUS | PR | 0.25 × 106 | PD | 0 |

| 11 | MM | 38/F | CTX/TBI | PR | 0.47 × 106 | CR | 0 |

| 12 | MM | 49/M | CTX/TBI | PR | 0.97 × 106 | CR | 2 |

| 13 | MM | 43/F | CTX/TBI | PR | 0.06 × 106 | CR | 3 |

| 14 | NHL | 34/M | CTX/TBI | CR | 0.85 × 106 | PR | 0 |

| 15 | NHL | 32/M | CTX/TBI | CR | 0.43 × 106 | PR | 0 |

| 16 | MM | 50/M | CTX/TBI | PR | 1.60 × 106 | PR | 0 |

| Patient no. . | Disease . | Age, y, at BMT/sex . | BMT conditioning regimen . | Disease status at BMT . | BM CD3+ cells per kilogram infused . | Disease status after BMT . | Acute GVH disease stage after BMT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | MM | 45/M | CTX/BUS | PR | 0.25 × 106 | PD | 0 |

| 11 | MM | 38/F | CTX/TBI | PR | 0.47 × 106 | CR | 0 |

| 12 | MM | 49/M | CTX/TBI | PR | 0.97 × 106 | CR | 2 |

| 13 | MM | 43/F | CTX/TBI | PR | 0.06 × 106 | CR | 3 |

| 14 | NHL | 34/M | CTX/TBI | CR | 0.85 × 106 | PR | 0 |

| 15 | NHL | 32/M | CTX/TBI | CR | 0.43 × 106 | PR | 0 |

| 16 | MM | 50/M | CTX/TBI | PR | 1.60 × 106 | PR | 0 |

MM indicates multiple myeloma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; CTX, cyclophosphamide; BUS, busulfan; TBI, total body irradiation; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; and CR, complete response.

Lymphocyte reconstitution following BMT and CD4+DLI

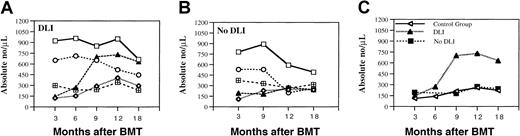

To identify the immunologic effects of prophylactic CD4+ DLI, we first examined well-defined lymphocyte subsets in peripheral blood during the first 6 months after BMT and for 1 year after DLI. The absolute number of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells, CD20+ B cells, and CD56+ natural killer (NK) cells present at various times is summarized in Figure 1A. Each of these subsets had recovered by 3 months after BMT, but CD4+ T cells and CD20+ B cells were only present at low levels. There was little change in these subsets 6 to 9 months after BMT, but the number of CD3+CD8+ cells decreased at 12 and 18 months after BMT. There was no significant change in the number of NK cells throughout this period. The number of CD20+ B cells increased from a median of 144 (range, 99-243 cells) 3 months after BMT to 730 (range, 160-1257 cells) 12 months after BMT and 631 (range, 159-3167 cells) at 18 months after BMT. These differences were statistically significant at 9 and 12 months (P = .03 andP = .05, respectively). The increase in CD20+B cells occurred in patients who achieved CR as well as in patients who continued to demonstrate only PR after DLI. The number of CD3+CD4+ T cells was low and stable in the first 6 months after BMT and gradually increased at later time points. No significant differences were found in lymphocyte subpopulations between patients who developed GVH disease (grade 2-4) and patients without GVH disease after DLI. A similar analysis of lymphocyte subsets in patients who did not receive prophylactic DLI is shown in Figure 1B. When compared with patients who received CD4+ DLI, the only statistically significant difference was the lower absolute number of CD20+ B cells at 9 (P = .001) and 12 months (P = .04) after BMT. No significant differences between the 2 groups at any time point were detected in the absolute number of CD3+ (P = .23), CD4+(P = .60), CD8+ (P = .18), or CD56+ (P = .10) cells.

Analysis of blood lymphocytes.

(A) Phenotypic analysis of lymphocyte subsets in patients with myeloma who underwent T-cell–depleted allogeneic BMT followed by prophylactic DLI. (B) Patients with myeloma and lymphoma who did not receive DLI. Lymphocyte reconstitution was determined by flow cytometric analysis of PBMCs. Values represent median absolute cell numbers for total CD3+ (open squares), CD3+CD4+ (open diamonds), CD3+CD8+ (open circles), CD20+(filled triangles), and CD56+ (checked boxes) cells in each sample. (C) Comparison of the number of CD20+ B cells in 3 patient groups: 9 patients with myeloma who received DLI (DLI group), 7 patients with myeloma and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma who did not receive DLI (no-DLI group), and 87 patients with other hematologic malignancies who did not receive DLI (control group).

Analysis of blood lymphocytes.

(A) Phenotypic analysis of lymphocyte subsets in patients with myeloma who underwent T-cell–depleted allogeneic BMT followed by prophylactic DLI. (B) Patients with myeloma and lymphoma who did not receive DLI. Lymphocyte reconstitution was determined by flow cytometric analysis of PBMCs. Values represent median absolute cell numbers for total CD3+ (open squares), CD3+CD4+ (open diamonds), CD3+CD8+ (open circles), CD20+(filled triangles), and CD56+ (checked boxes) cells in each sample. (C) Comparison of the number of CD20+ B cells in 3 patient groups: 9 patients with myeloma who received DLI (DLI group), 7 patients with myeloma and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma who did not receive DLI (no-DLI group), and 87 patients with other hematologic malignancies who did not receive DLI (control group).

B-cell reconstitution was also analyzed in a cohort of 87 patients with other hematologic malignancies who received the same myeloablative conditioning regimen followed by CD6 T-cell–depleted BMT (Figure1C).6 40 The median absolute number of B cells in this additional control group of patients was 111.5 (range, 12.5-678.2 cells) (n = 41), 139.5 (range, 17.6-563 cells) (n = 31), 211.1 (range, 57.6-1242 cells) (n = 25), 260.2 (range, 28-1164 cells) (n = 39), and 221.1 (range, 67.2-678.7 cells) (n = 15) at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 18 months, respectively. As shown in Figure 1C, there was no difference between the 2 groups who received only T-cell–depleted BMT;P = .43, P = .44, P = .99,P = .73 at 3, 9, 12, and 18 months after BMT, respectively. Because we did not find any difference between these 2 groups, they were combined and compared with the group of patients who received DLI. In this analysis, B-cell reconstitution was significantly greater in patients who received DLI (P = .0012).

Reconstitution of TCR Vβ repertoire

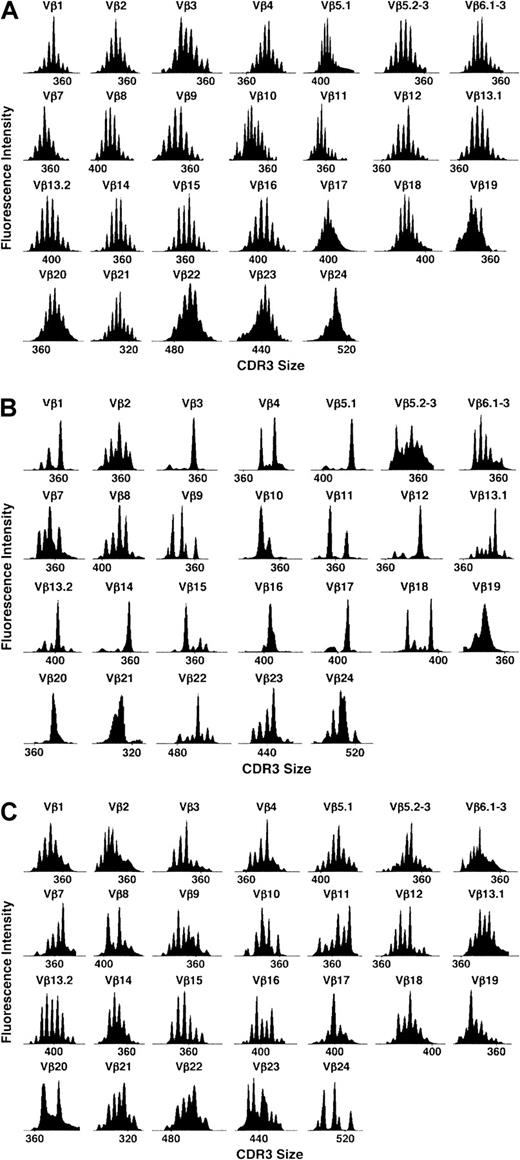

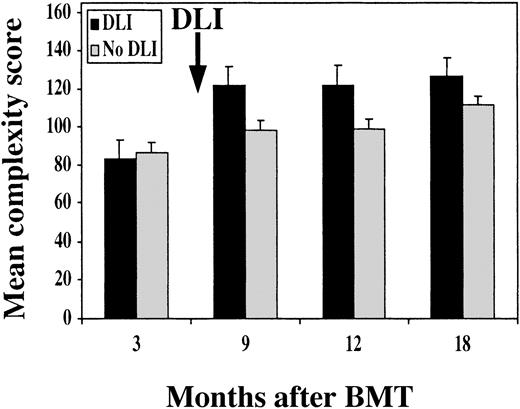

Reconstitution of TCR repertoire was monitored by TCR Vβ spectratyping. As shown for patient no. 6 in Figure2B, Vβ spectratype profiles 3 months after BMT were markedly abnormal compared with normal donor spectratype shown in Figure 2A. Most patient profiles contained only clonal or oligoclonal peaks, indicating marked limitation of the TCR repertoire. In contrast, spectratype profiles 3 months after CD4+ DLI (Figure 2C) demonstrated marked improvement with few oligoclonal profiles. To compare TCR repertoires in different patients, we utilized a complexity score to quantify changes in repertoire after BMT and DLI.15 Based on the analysis of 7 healthy donors, we calculated a score of 137 to be the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval for the mean of the healthy donors. As shown in Figure 3, all patients in both groups had low complexity scores 3 months after BMT compared with the healthy donors—median score of 82 (range, 75-111) in the DLI group and 84 (range, 80-98) in the no-DLI group. In patients who received DLI, complexity scores pre-DLI (6 months after BMT) were not significantly higher than at 3 months after BMT (data not shown). TCR complexity scores improved at 9 months after BMT in patients who received CD4+ DLI. In contrast, complexity scores remained low in patients who did not receive DLI. In comparison with patients who received DLI, these values were significantly lower at all subsequent time points; P = .02, P = .05, andP = .04 at 9, 12, and 18 months, respectively. Comparison of the rate of recovery confirmed that complexity scores improved more rapidly after BMT in patients who received DLI (P = .01).

Representative examples of TCR Vβ repertoire profiles.

Profiles are in a healthy donor (A), patient no. 6 at 3 months after BMT (B), and the same patient 3 months after DLI (C).

Representative examples of TCR Vβ repertoire profiles.

Profiles are in a healthy donor (A), patient no. 6 at 3 months after BMT (B), and the same patient 3 months after DLI (C).

Mean TCR repertoire complexity score.

Score is shown at different times after BMT in patients who received prophylactic DLI (black bars) and patients without DLI (gray bars).

Mean TCR repertoire complexity score.

Score is shown at different times after BMT in patients who received prophylactic DLI (black bars) and patients without DLI (gray bars).

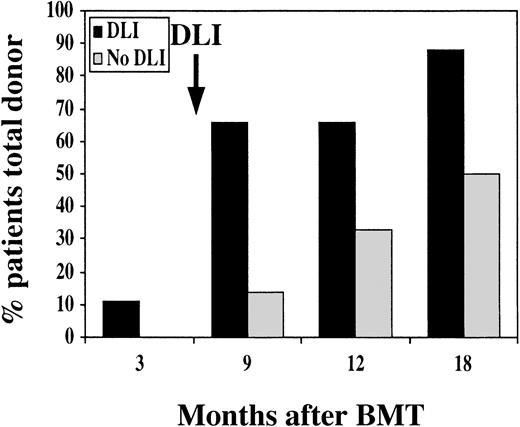

Effect of CD4+ DLI on hematopoietic chimerism

Analysis of informative polymorphic microsatellite regions was used to distinguish between donor and recipient cells and to quantify the extent of hematopoietic chimerism after BMT. All patients had evidence of engraftment with donor cells, but only 1 patient in the DLI group had established complete donor hematopoiesis at 3 and 6 months after BMT (Figure 4). All other patients in the DLI group were found to have stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism prior to DLI, with 25% to 80% donor cells in peripheral blood. By 3 months after DLI, 5 additional patients had established complete donor chimerism. By 1 year after DLI, 8 of 9 patients had complete donor hematopoiesis and only 1 patient had persistent mixed chimerism. All patients who did not receive DLI also had evidence of mixed hematopoietic chimerism 3 months after BMT. With further follow-up, a gradual increase in the fraction of patients who converted to complete donor hematopoiesis was also noted in this group. However, at 9 months after BMT, only 1 of 7 patients had established complete donor hematopoiesis, and only 1 additional patient developed complete donor hematopoiesis 1 year after BMT without DLI. Although the fractions of patients who eventually converted to complete donor chimerism in the 2 groups were not significantly different (P = .26), the median time to achieve complete donor chimerism was 9 months with DLI and 18 months without DLI. This difference is statistically significant (P = .05, Wilcoxon).

Hematopoietic chimerism after BMT.

The graph indicates the percentage of patients with complete donor hematopoiesis at various times after BMT. Black bars indicate patients who received prophylactic DLI, and gray bars indicate patients without DLI.

Hematopoietic chimerism after BMT.

The graph indicates the percentage of patients with complete donor hematopoiesis at various times after BMT. Black bars indicate patients who received prophylactic DLI, and gray bars indicate patients without DLI.

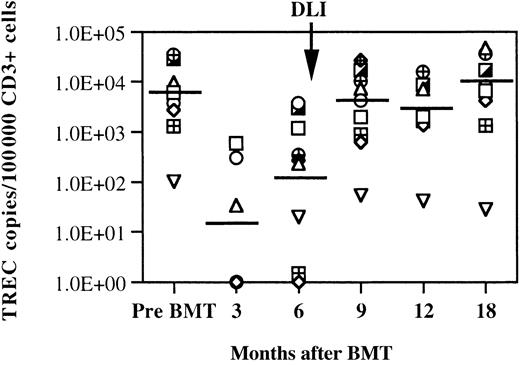

Quantitative analysis of TCR excision circles

Quantitative measurement of TRECs was also used to examine reconstitution of T cells after BMT and DLI. TRECs are produced in individual T cells as a byproduct of TCR gene rearrangement. Previous studies have demonstrated that these episomal DNA fragments can therefore be used to identify recent thymic emigrants and to measure recovery of T-cell neogenesis after BMT.32 38 Using a quantitative PCR assay, TRECs were measured in the same samples used to evaluate TCR Vβ repertoire, lymphocyte phenotype, and chimerism. Because only CD3+ cells contain TRECs, results of assays summarized in Figure 5 show the number of TREC copies measured per 105 CD3+ T cells. Prior to transplantation, the median TREC count was 6.1 × 103 copies. This value was not statistically different from the TREC counts of 10 healthy donors of similar ages (data not shown). The median value of TREC counts 3 months after BMT was significantly lower than pretransplantation values (P = .04), and TREC counts were below the limit of detection for this assay (< 100 copies per 105CD3+ cells) in 4 patients. TREC values increased 6 months after BMT but remained significantly lower than pre-BMT values (P = .01). At 6 months after BMT, only 3 patients still had undetectable TRECs in circulating T cells. By 9 months after BMT, TREC values had returned to pretransplantation levels and were significantly higher than pre-DLI values (P = .022). TREC levels remained normal throughout the 1-year follow-up period after DLI. Also shown in Figure 5, 1 patient had relatively low TREC values at all the time points evaluated. This patient had relatively low TREC copies before transplantation and was also the single individual who demonstrated persistent mixed hematopoietic chimerism after DLI. TREC values were compared in patients who developed grade 2-4 GVH disease (n = 5) and patients without GVH disease (n = 4) after DLI and were not significantly different (P > .06 Mann-Whitney rank sum test).

Quantitative assessment of TRECs after BMT in patients who received CD4+ DLI.

Lines at each time point represent the median number of TREC copies per 100 000 CD3+ cells. Data points on the x-axis represent samples without detectable TREC copies. The limit of the sensitivity of the assay is 100 copies per 100 000 CD3+ cells.

Quantitative assessment of TRECs after BMT in patients who received CD4+ DLI.

Lines at each time point represent the median number of TREC copies per 100 000 CD3+ cells. Data points on the x-axis represent samples without detectable TREC copies. The limit of the sensitivity of the assay is 100 copies per 100 000 CD3+ cells.

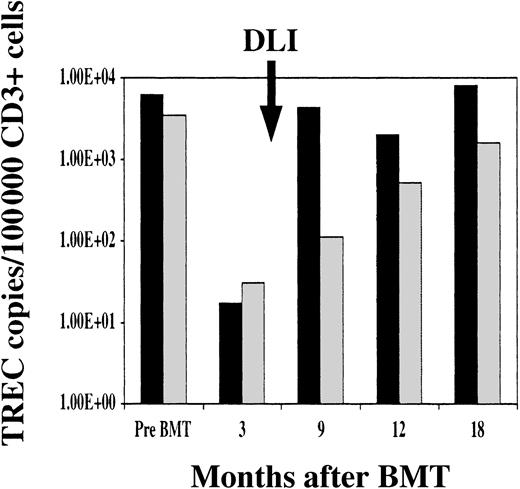

TRECs were also measured in patients who did not receive DLI. As shown in Figure 6, median TREC counts in peripheral blood CD3+ cells were similar in both groups prior to BMT and at 3 months after transplantation. TREC values returned to normal levels 9 months after BMT in patients who received DLI, but TREC values remained significantly low in patients who did not receive DLI. TREC values increased in patients who did not receive DLI at 12 and 18 months after BMT, but recovery of normal TREC counts was significantly slower in patients who did not receive DLI (P < .0001).

TREC recovery after BMT.

Comparison of median TREC copies per 100 000 CD3+ cells in patients who received prophylactic DLI (black bars) and patients without DLI (gray bars).

TREC recovery after BMT.

Comparison of median TREC copies per 100 000 CD3+ cells in patients who received prophylactic DLI (black bars) and patients without DLI (gray bars).

Discussion

Previous reports from several centers have documented high response rates following DLI in patients with multiple myeloma who relapse after allogeneic BMT. Responses are maintained when CD8+ cells are depleted from the donor lymphocytes prior to infusion, and previous clinical trials have demonstrated that approximately 50% of patients with relapsed multiple myeloma have clinical responses after infusion of 3 × 107 to 15 × 107 CD4+ cells per kilogram.23 To determine whether earlier infusion of donor lymphocytes would provide more effective control of myeloma, we undertook a clinical trial to examine the antitumor effects of prophylactic DLI in patients who received myeloablative therapy followed by infusion of CD6 T-cell–depleted BM from HLA-identical sibling donors.33 No prophylactic immune suppressive therapy was administered, and patients without GVH disease received a single infusion of 3 × 107 CD4+ from the same donor 6 months after BMT. Despite administration of myeloablative therapy, most patients continued to have evidence of persistent myeloma 6 months after BMT. Importantly, all patients with persistent disease had evidence of further disease response following CD4+DLI. These observations confirmed previous studies indicating that allogeneic immune responses contribute to the control of multiple myeloma following BMT and support the further use of donor immune responses to improve outcomes of allogeneic BMT in this disease.

The prophylactic infusion of donor lymphocytes in a defined cohort of patients also provided us with an opportunity to examine the immunologic effects of this treatment. Although the antitumor activity of DLI has been well documented, the immunologic mechanisms responsible for tumor rejection have not been defined, and the effects of DLI on cellular immune function in the recipient have not been well characterized. To examine these immunologic effects, serial samples of PBMCs were obtained over an 18-month period from a cohort of 9 patients enrolled in this clinical trial who received prophylactic DLI. The immunologic studies carried out with these samples were designed to provide a quantitative assessment of reconstitution of T-cell immunity rather than the recovery of T-cell responsiveness to specific antigens. For comparison, similar studies were carried out with cryopreserved samples from 7 patients who underwent similar therapy except that they did not receive prophylactic DLI.

We first examined the reconstitution of well-defined lymphocyte subsets of PBMCs using flow cytometry. Although all patients received T-cell–depleted donor marrow, CD3+ cells had recovered by 3 months after BMT. Consistent with the results of previous studies, these cells were predominately CD8+, and the number of CD4+ T cells recovered very slowly after BMT.6NK cells recovered rapidly after BMT, but B cells recovered slowly. Infusion of CD4+ donor lymphocytes at 6 months after BMT had no discernable effect on the number of CD4+ or CD8+ CD3+ T cells or NK cells. However, CD20+ B cells were significantly increased in patients who received CD4+ DLI. The increase in circulating B cells was most evident at 3 and 6 months after DLI, and this observation was confirmed in further comparison with a large cohort of 87 patients with other hematologic malignancies who had undergone T-cell–depleted BMT without DLI. The demonstration of increased B-cell reconstitution after CD4+ DLI is consistent with previous studies indicating that tumor rejection following DLI results from a coordinated immune response that includes B-cell as well as T-cell responses.41 Thus, patients who respond to DLI often have marrow infiltration with polyclonal plasma cells, and high-titer antibody responses to a variety of leukemia-associated antigens have been documented in these patients.41

The effect of DLI on T-cell reconstitution was also examined through analysis of TCR repertoire. Healthy individuals maintain a highly complex T-cell repertoire, and this can be quantified through examination of TCR Vβ profiles (spectratype) generated for each of the Vβ subfamilies. We have previously used this method to examine T-cell reconstitution after allogeneic BMT and found that spectratype complexity is markedly deficient in the first 3 to 6 months after BMT and that complexity gradually increases thereafter.15 In contrast to the rapid recovery of normal numbers of phenotypically mature CD3+ T cells, reconstitution of a complex TCR spectratype is a relatively slow process that often requires 12 to 18 months after transplantation. Infusion of mature CD4+ donor lymphocytes at 6 months after BMT significantly improved the rate of reconstitution of a highly complex spectratype pattern for all TCR Vβ families. This improvement became evident 3 months after DLI and continued throughout the next 9 months of follow-up.

In conjunction with assessment of TCR repertoire, we also examined the number of TRECs in CD3+ PBLs. TRECs are generated as a byproduct of TCRα gene rearrangement and therefore provide an independent measure of T-cell neogenesis from undifferentiated hematopoietic stem cells. Although the thymus undergoes involution in adults, analysis of TRECs in healthy individuals has demonstrated that T-cell neogenesis continues despite thymic involution, and this contributes to the maintenance of a diverse T-cell repertoire.16,42,43 The mature T cells present in peripheral blood early after recovery from myeloablative therapy have a very restricted repertoire, and TREC levels in these cells are very low. TREC values begin to recover by 6 months after BMT, indicating recovery of thymic function and the increased generation of new T cells from hematopoietic progenitors.32,38 44 Importantly, CD4+ DLI appears to accelerate the recovery of thymic function. This is most evident at 3 months after DLI, at which time TREC values had returned to normal levels in patients who had received DLI but remained low in patients who did not receive DLI. We did not find any difference in absolute lymphocyte subsets, Vβ repertoire score, and TREC copy number in patients who developed GVH disease and patients without GVH disease after DLI. Taken together with increasing complexity of TCR spectratypes, the enhanced recovery of TREC provides clear evidence for increasing levels of T-cell neogenesis in patients who receive CD4+ DLI.

Although the mechanism by which infusion of a relatively small number of mature CD4+ donor T cells can enhance thymic function and T-cell neogenesis is not known, we have previously observed that reconstitution of a normal T-cell repertoire was also associated with the establishment of complete donor hematopoiesis.15 We therefore included an examination of hematopoietic chimerism in our assessment of T-cell reconstitution and found that CD4+ DLI also appeared to enhance the conversion of mixed chimerism to complete donor hematopoiesis. Five patients converted to complete donor hematopoiesis 3 months after DLI, and 8 of 9 patients had complete donor hematopoiesis 1 year after DLI. Interestingly, the single individual who maintained mixed hematopoietic chimerism after DLI was also the only individual who had minimal recovery of TRECs after DLI. These observations suggest that reconstitution of cellular immunity after transplantation is facilitated by the establishment of full donor hematopoiesis, but further studies will be necessary to determine the mechanism whereby this occurs in these patients.

In summary, our examination of cellular immunity after prophylactic DLI provides consistent evidence that CD4+ DLI initiates a profound and long-lasting effect on T-cell immunity after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Interestingly, these immunologic effects reflect changes in global reconstitution of T-cell immunity and appear to occur independently of any specific response to residual recipient tumor cells or tumor-associated antigens. Further studies in animal model systems as well as in patients who receive DLI will be necessary to better define the mechanism underlying this immunologic effect. Nevertheless, these studies suggest that infusion of CD4+donor T cells may provide a clinically simple and straightforward method for enhancing reconstitution of T-cell immunity as well as promoting antitumor immunity after allogeneic BMT. This hypothesis can be examined in future clinical trials to determine whether prophylactic CD4+ DLI might improve clinical outcomes by reducing the incidence of opportunistic infections after allogeneic stem cell transplantation

Supported by NIH grants AI29530, HL04293, and CA78378. R.J.S. is a Clinical Research Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. K.C.A. is a Doris Duke Distinguished Clinical Scientist.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Jerome Ritz, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 44 Binney St—M530, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail:jerome_ritz@dfci.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal