We have developed a real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay using TaqMan technology (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for monitoring donor cell engraftment in allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. For this purpose, we selected 19 specific sequence polymorphisms belonging to 11 human biallelic loci located on 9 different chromosomes. Using a set of specially designed primers and fluorogenic probes, we evaluated the 19 markers' informativity on a panel of 126 DNA samples from 63 recipient/donor pairs. In more than 90% of these pairs, discrimination between recipient and donor genetic profile was possible. By using serial dilutions of mixed DNAs, we evaluated the linearity and sensitivity of the method. A linear correlation with rhigher than 0.98 and a sensitivity of 0.1% proved reproducible. Fluorescent-based PCR of short tandem repeats (STR-PCR) and real-time PCR chimerism assay were compared with a panel of artificial cell mixtures. The main advantage of the real-time PCR method over STR-PCR chimerism assays is the absence of PCR competition and plateau biases, and results evidenced greater sensitivity and linearity with the real-time PCR method. Furthermore, different samples can be tested in the same PCR run with a final result in fewer than 48 hours. Finally, we prospectively analyzed patients who received allografts and present 4 different clinical situations that illustrate the informativity level of our method. In conclusion, this new assay provides an accurate quantitative assessment of mixed chimerism that can be useful in guiding early implementation of additional treatments in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Introduction

During the last 3 decades, allogenic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) has been extensively used to treat patients with malignant hematological diseases or nonmalignant hematological diseases, such as severe aplastic anemia, severe combined immunodeficiency, or hemoglobinopathies.1 The major causes of treatment failure are disease relapse, graft rejection, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

One of the main goals of posttransplantation monitoring is to predict these negative events in order to set up the relevant preventive therapeutics. In this context, mixed chimerism quantification has been proposed as an important method in monitoring post-BMT outcome. In fact, several previous works suggest that an accurate quantitative analysis of chimerism kinetics would permit early differentiation between the absence of engraftment and a delay in engraftment as well as early detection of patients with a high risk of GVHD2-5 or those liable to relapse.6-8

The simple demonstration of the existence of mixed chimerism by qualitative methods is of little interest as regards the clinical consequences for the patient. Conversely, the characterization of an increase in the proportion of host cells in the post-BMT period strongly suggests a risk of disease recurrence.9-12 In this case, an early diagnosis is an important aspect of the prognosis since relapsing patients may enter durable second remission through a donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI), whose efficiency can be monitored by a conversion of mixed myeloid chimerism to a complete donor-type pattern.13,14 Moreover, new therapeutic approaches such as nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation must be monitored by an analysis of early chimerism pattern to set up additional therapeutic interventions, for example, DLI.15-17

Until now, various techniques have been used to document chimerism after allogenic BMT (allo-BMT), such as fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) with XY chromosome–specific probes or polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based amplification of variable number tandem repeats or short tandem repeats (STRs). The main drawback of the XY-FISH chimerism assay is its poor informativity (restricted to sex-mismatched allografts). Thus, fluorescent-based PCR analysis of STR has become the gold standard for quantitative chimerism analysis so far. This so-called STR-PCR method offers the highest informativity (nearly 100% of unrelated allografts are evaluable) and good accuracy for quantification. However, the sensitivity of this method is relatively low (detection level of a minor genotype is between 0.4% and 5%), mainly as a consequence of PCR competition biases. In the present study, we propose a new approach for determining mixed chimerism based on real-time quantitative PCR using the TaqMan technology. Real-time quantitative PCR (or real-time quantitative reverse-transcription PCR [RT-PCR]) with TaqMan technology relies on the detection and measurement of the PCR process itself. This is done by means of a sequence-specific hybridization probe, inserted between the forward and reverse primers. During the extension phase of the PCR process, this fluorogenic probe is cleaved and therefore emits a fluorescent signal, which is analyzed in a dedicated thermocycler. As amplifiable PCR products, and therefore the amount of cleaved probe, double during each cycle of a regular PCR process, a strict linear relationship is observed between the logarithm of starting amplifiable DNA or RNA copy number and the rank of the first PCR cycle where a significant increase in the fluorescent signal is detected (termed cycle threshold [Ct]). Used mainly for specific messenger RNA quantification, this real-time PCR technology has proved very sensitive, accurate, and linear over a 4 or 5 log10 quantification range and is now a reference method for quantitative RT-PCR assays. Thus, real-time quantitative TaqMan PCR technology also appears promising for the detection and quantification of a minor DNA genotype in a major one, ie, for chimerism quantitative evaluation. For this purpose, we searched and selected informative human DNA sequence polymorphisms and designed primers and TaqMan fluorogenic probes, allowing their specific real-time PCR amplification. Independent real-time PCRs for donor- and recipient-specific alleles were combined into a single PCR-run chimerism assay protocol. We demonstrated that this real-time PCR procedure enables rapid, accurate, and robust quantification of mixed chimerism with a sensitivity of 0.1% regardless of sex mismatch. Informativity of the assay was tested on a panel of 63 bone marrow transplant recipient/donor pairs, and its linearity and sensitivity were tested by means of serial dilutions of mixed DNAs. Comparison with STR-PCR chimerism assay was done on a panel of 11 artificial chimeric DNAs and revealed greater linearity and sensitivity in the real-time PCR chimerism assay. Furthermore, the method was prospectively applied to the post-BMT or post-DLI monitoring of patients; 4 different clinical situations are illustrated in “Results.”

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients

We analyzed 126 pre-BMT DNA samples from 63 patients who underwent allo-BMT from 1993 to 2000 at Pontchaillou Hospital (Rennes, France) and from their donors—mainly HLA-identical siblings (n = 55), but also including unrelated volunteers (n = 8)—to evaluate the selected genetic markers. Sequential post-BMT DNA samples from 4 of these 63 patients—whose main characteristics are detailed in “Results”—were prospectively analyzed to assess the feasibility and usefulness of real-time quantitative PCR chimerism assay.

Sample preparation

High–molecular weight DNA was extracted from peripheral blood or bone marrow nuclear cells by means of a salting-out procedure.18 The concentration and purity of each DNA sample was evaluated by means of measurement of optical density at 260 and 280 nm with a UV spectrophotometer.

Genetic marker selection and primer and probe generation

We first selected sequence polymorphisms from an extensive bibliographical search and the list of human biallelic short insertion/deletion polymorphisms from the Marshfield Clinic (Marshfield, WI) (available at:http://www.marshfieldclinic.org/research/genetics/QueryResults/searchSIDP.htm.) Among the sequence polymorphisms found, a first selection was made according to the following criteria: biallelic polymorphisms, differing by at least 2 consecutive variable bases and showing a high level of heterozygozity in the general population.

Second, for each selected biallelic polymorphism, specific primer and probe sequences were designed virtually by means of Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) to select those acceptable in terms of TaqMan PCR requirements. For each biallelic system, one of the primers was chosen in the polymorphic region to specifically amplify each allele, whereas the second one was located in the common region. The TaqMan probe was common to both alleles.

Third, for each biallelic system selected after the first 2 steps, a pair of primers was tested in order to check its specificity and informativity, with the use of conventional qualitative PCR under the same conditions as those required for the real-time quantitative PCR chimerism assay. This analysis was done on the panel of 126 pre-BMT DNA samples.

Finally, the effective amount of amplifiable DNA input in each sample was assessed by means of an active reference system, and a pair of primers and a TaqMan probe specific for a constant and monomorphic gene were generated and used as the active reference in the real-time quantitative PCR chimerism assay. The T-cell receptor (TCR) CB gene was used first, followed by the glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene.

Real-time quantitative PCRs

Real-time quantitative PCRs were performed by means of TaqMan technology and ABI PRISM 7700 apparatus (Applied Biosystems). The TaqMan reaction is based on the 5′ nuclease activity of Taq polymerase to cleave a specific dual-labeled fluorogenic hybridization probe during the extension phase of PCR.19One fluorescent dye serves as a reporter (6-carboxyfluorescein [FAM]), and its emission spectrum is quenched by a second fluorescent dye (6-carboxy-tetramethyl-rhodamine [TAMRA]).

During the extension phase of the PCR cycle, the exonuclease activity of the DNA-polymerase cleaves the probe and releases the reporter dye, thereby increasing the fluorescence signal. For each sample, ABI PRISM 7700 software plotted an amplification curve by relating the fluorescence signal intensity (ΔRn) to the cycle number. The ΔRn value corresponded to the variation in reporter fluorescence intensity during each PCR cycle, normalized to the fluorescence of an internal passive reference. A specific Ct was determined for each PCR. The Ct was defined as the cycle number at which a significant increase in the fluorescence signal was first detected (the higher the starting copy number, the lower the Ct).

PCR reaction parameters were as follows: (1) reaction mix: 250 ng DNA mixed with 20 μL Master Mix 2X Buffer (Applied Biosystems), 600 nM each primer, and 200 nM TaqMan probe in a final volume of 40 μL. (2) PCR cycles: 2 minutes at 50°C followed by 10 minutes at 95°C and 40 amplification cycles (95°C for 45 seconds and 60°C for 60 seconds).

Standard amplification curves

To evaluate the validity and sensitivity of real-time quantitative PCR chimerism analysis, standard amplification curves were plotted for recipient- and donor-specific allele PCRs from artificial chimeric DNA samples made with 14 serial halved dilutions of recipient DNA in donor DNA and vice versa (ie, from 1:0 to 1:8000 recipient-to-donor or donor-to-recipient DNA ratio) in a constant final amount of 250 ng chimeric DNA.

Real-time quantitative PCR chimerism assay

Before quantification, the donor and recipient were genotyped by means of typing trays stored at −20°C ready to use and containing primers and probes specific for all the 19 genetic markers in the same concentrations as for the quantification assay. In addition, a negative well (absence of primers) was included in each tray. For the genotyping, 100 ng DNA was added in each well, and real-time PCR was carried out with the same amplification program as for quantification. Positive alleles were defined by a Ct value ranging between 20 to 23, whereas negativity for a specific allele was assessed by a Ct value exceeding 36. An allele was considered informative when positive on recipient DNA and negative on donor DNA, or conversely negative on recipient DNA and positive on donor DNA. When more than one allele was informative, only one marker was used for each genotype profile, since quantitative analyses were similar regardless of the genetic marker used, as illustrated in “Results.” The chimerism assay protocol included the following PCRs performed in duplicate on post-BMT DNA samples as well as on pre-BMT recipient and donor DNA samples: recipient-specific allele amplification, donor-specific allele amplification, and active reference amplification.

In addition, standard amplification curves were plotted for recipient- and donor-specific allele PCRs, with the use of artificial chimeric DNA samples made with pre-BMT recipient and donor DNA, respectively.

Results analysis and quantification formula

Data analysis steps were as follows: (1) A specific Ct was determined for each real-time quantitative PCR. (2) Standard amplification curves generated on the basis of the relationship between Ct value and the logarithm of the DNA copy number defined PCR efficiency for recipient- and donor-specific allele amplification. PCR efficiency was deduced from each standard curve by ABI PRISM 7700 software and expressed as E = 10−1/s − 1, where s is the curve slope. (3) For the real-time PCR of each recipient and donor marker, the Ct value was individually normalized according to the effective DNA amount in each sample tested. This was done with the use of the active reference Ct value of the sample considered and expressed as follows: normalized Ct = ΔCt = Ct target sequence − Ct active reference. (4) For real-time quantitative PCRs for recipient and donor markers, the pre-BMT recipient and donor DNA samples, respectively, were used as calibrator samples and give ΔCt corresponding by definition to the amplification of a 100% fraction of recipient and donor genotype. (5) Finally, the fraction of the target DNA sequence in the unknown sample (FU) was calculated as the ratio of the normalized quantity in the unknown sample (QU) divided by the normalized quantity in the calibrator sample (QC). The formula used for this calculation was,

where QU is the quantity of target DNA sequence in the unknown sample; QC is the quantity of target DNA sequence in the calibrator (pre-BMT) sample; ΔCtU is ΔCt in the unknown sample; ΔCtC is ΔCt in the calibrator sample; and E is PCR efficiency of the target DNA sequence calculated as described above.

Comparison of fluorescent-based PCR analysis of STR with real-time PCR chimerism assays

To compare the real-time PCR chimerism assay and the fluorescent-based PCR analysis of STR, we designed a set of 11 artificial chimeric DNAs. For this purpose, 50 mL peripheral blood from 2 unrelated volunteers was collected. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by means of standard density gradient separation procedure (Ficoll hypaque). The 2 cell suspensions were precisely numerated, and cell viability was assessed to be superior to 95% by optical counting with trypan blue exclusion dye. Then, PBMCs from the individual named “recipient” were serially diluted in PBMCs from the “donor,” leading to 11 different recipient/donor cell mixtures covering the assumed sensitivity range of real-time PCR assay. Percentages of recipient PBMCs in donor PBMCs were as follows: 80%, 40%, 20%, 10%, 5%, 2.5%, 1.25%, 0.62%, 0.31%, 0.15%, and 0.07%. DNA from these 11 cell mixtures and from pure recipient and donor cell fractions was extracted as described. Chimerism analysis of these artificial chimeric samples was performed with real-time PCR assay and fluorescent-based PCR analysis of STR assay.

STR-PCR analysis was carried out in the Hematology Laboratory of Hospital Henri Mondor (Créteil, France), which routinely performed chimerism analysis by this method. PCR was performed on 100 ng spectrophotometrically quantified DNA with the use of the fluorescent primers already described for SE33, D21S11, and Tho1 STR.20-22 The amplification reaction and cycling conditions were as previously described.23 One microliter of PCR product was run on 6% acrylamide sequencing gel on an Applied Biosystem 377 sequencing apparatus. Gels were analyzed for peak areas by means of GeneScan software (Applied Biosystems).

Results

Informativity of the genetic markers

Out of 100 human biallelic genetic systems considered as potentially informative through bibliographical and database querying, 30 were found to be compatible with TaqMan PCR requirements, after an attempt to generate specific primers and probe by means of Primer Express software. All these biallelic markers were tested by conventional PCR with the use of TaqMan-specific conditions, resulting in the selection of 19 specific markers belonging to 11 different loci located on 9 different chromosomes. Primer and probe sequences of the 19 selected markers are detailed in Table1. Informativity of the 19 selected markers was evaluated on the panel of 126 pre-BMT DNA samples from 63 recipient/donor pairs. Results are detailed in Table 1. These results demonstrate the high level of overall informativity obtained with our set of biallelic systems: recipient genotype discrimination was possible in 8 of 8 unrelated pairs and 52 of 55 related pairs, and donor genotype discrimination in 8 of 8 unrelated pairs and 46 of 55 related pairs. The mean number of informative systems for each recipient/donor pair was 3 (1 to 8). Thus, informative results with real-time quantitative PCR chimerism assay could exceed 90% of recipient/donor pairs, even in sex-matched related pairs.

Characteristics of specific genetic markers analyzed by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

| Marker name . | Location . | Informativity, % . | Position . | 5′ Primer 3′ . | TaqMan (FAM-TAMRA) probe . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S 01a | 17q | 23.6 | F | GGTACCGGGTCTCCACATGA | CTGGGCCAGAATCTTGGTCCTCACA |

| R* | GGGAAAGTCACTCACCCAAGG | ||||

| S 01b | F | GTACCGGGTCTCCACCAGG | |||

| S 02 | Y | 36.4 | F | GCTTCTCTGGTTGGAGTCACG | CTGCACCACCAAATCATCCCCGTG |

| R | GCTTGCTGGCGGACCCT | ||||

| S 03 | 6q | 16.4 | F | CTTTTGCTTTCTGTTTCTTAAGGGC | CATACGTGCACAGGGTCCCCGAGT |

| R | TCAATCTTTGGGCAGGTTGAA | ||||

| S 04a | 9 | 23.6 | F* | CTGGTGCCCACAGTTACGCT | TCCTGGCAGTGTGGTCCCTTCAGAA |

| R | AAGGATGCGTGACTGCTATGG | ||||

| S 04b | 12.7 | R | AGGATGCGTGACTGCTCCTC | ||

| S 05a | 20 | 1.8 | F | AAAGTAGACACGGCCAGACTTAGG | CCCTGGACACTGAAAACAGGCAATCCT |

| R* | CATCCCCACATACGGAAAAGA | ||||

| S 05b | 27.3 | F | AGTTAAAGTAGACACGGCCTCCC | ||

| S 06 | 1p | 31.0 | F | CAGTCACCCCGTGAAGTCCT | CCCATCCATCTTCCCTACCAGACCAGG |

| R | TTTCCCCCATCTGCCTATTG | ||||

| S 07a | X | 31.0 | F | TGGTATTGGCTTTAAAATACTGGG | TCCTCACTTCTCCACCCCTAGTTAAACAG |

| R | TGTACCCAAAACTCAGCTGCA | ||||

| S 07b | 21.8 | F | GGTATTGGCTTTAAAATACTCAACC | ||

| R | CAGCTGCAACAGTTATCAACGTT | ||||

| S 08a | 1q | 16.4 | F | CTGGATGCCTCACTGATCCA | CTCCCAACCCCCATTTCTGCCTG |

| R* | TGGGAAGGATGCATATGATCTG | ||||

| S 08b | 20.2 | F | GCTGGATGCCTCACTGATGTT | ||

| S 09a | 17q | 7.3 | F* | GGGCACCCGTGTGAGTTTT | TGGAGGATTTCTCCCCTGCTTCAGACAG |

| R | TCAGCTTGTCTGCTTTCTGGAA | ||||

| S 09b | 14.5 | R | CAGCTTGTCTGCTTTCTGCTG | ||

| S 10a | 18 | 25.5 | F | GCCACAAGAGACTCAG | CAGTGTCCCACTCAAGTACTCCTTTGGA |

| R | TGGCTTCCTTGAGGTGGAAT | ||||

| S 10b | 20.2 | F | TTAGAGCCACAAGAGACAACCAG | ||

| S 11a | 11 | 25.5 | F | TAGGATTCAACCCTGGAAGC | CAAGGCTTCCTCAATTCTCCACCCTTCC |

| R* | CCAGCATGCACCTGACTAACA | ||||

| S 11b | 7.3 | F | CCCTGGATCGCCGTGAA | ||

| GAPDH | F | GGACTGAGGCTCCCACCTTT | CATCCAAGACTGGCTCCTCCCTGC | ||

| R | GCATGGACTGTGGTCTGCAA |

| Marker name . | Location . | Informativity, % . | Position . | 5′ Primer 3′ . | TaqMan (FAM-TAMRA) probe . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S 01a | 17q | 23.6 | F | GGTACCGGGTCTCCACATGA | CTGGGCCAGAATCTTGGTCCTCACA |

| R* | GGGAAAGTCACTCACCCAAGG | ||||

| S 01b | F | GTACCGGGTCTCCACCAGG | |||

| S 02 | Y | 36.4 | F | GCTTCTCTGGTTGGAGTCACG | CTGCACCACCAAATCATCCCCGTG |

| R | GCTTGCTGGCGGACCCT | ||||

| S 03 | 6q | 16.4 | F | CTTTTGCTTTCTGTTTCTTAAGGGC | CATACGTGCACAGGGTCCCCGAGT |

| R | TCAATCTTTGGGCAGGTTGAA | ||||

| S 04a | 9 | 23.6 | F* | CTGGTGCCCACAGTTACGCT | TCCTGGCAGTGTGGTCCCTTCAGAA |

| R | AAGGATGCGTGACTGCTATGG | ||||

| S 04b | 12.7 | R | AGGATGCGTGACTGCTCCTC | ||

| S 05a | 20 | 1.8 | F | AAAGTAGACACGGCCAGACTTAGG | CCCTGGACACTGAAAACAGGCAATCCT |

| R* | CATCCCCACATACGGAAAAGA | ||||

| S 05b | 27.3 | F | AGTTAAAGTAGACACGGCCTCCC | ||

| S 06 | 1p | 31.0 | F | CAGTCACCCCGTGAAGTCCT | CCCATCCATCTTCCCTACCAGACCAGG |

| R | TTTCCCCCATCTGCCTATTG | ||||

| S 07a | X | 31.0 | F | TGGTATTGGCTTTAAAATACTGGG | TCCTCACTTCTCCACCCCTAGTTAAACAG |

| R | TGTACCCAAAACTCAGCTGCA | ||||

| S 07b | 21.8 | F | GGTATTGGCTTTAAAATACTCAACC | ||

| R | CAGCTGCAACAGTTATCAACGTT | ||||

| S 08a | 1q | 16.4 | F | CTGGATGCCTCACTGATCCA | CTCCCAACCCCCATTTCTGCCTG |

| R* | TGGGAAGGATGCATATGATCTG | ||||

| S 08b | 20.2 | F | GCTGGATGCCTCACTGATGTT | ||

| S 09a | 17q | 7.3 | F* | GGGCACCCGTGTGAGTTTT | TGGAGGATTTCTCCCCTGCTTCAGACAG |

| R | TCAGCTTGTCTGCTTTCTGGAA | ||||

| S 09b | 14.5 | R | CAGCTTGTCTGCTTTCTGCTG | ||

| S 10a | 18 | 25.5 | F | GCCACAAGAGACTCAG | CAGTGTCCCACTCAAGTACTCCTTTGGA |

| R | TGGCTTCCTTGAGGTGGAAT | ||||

| S 10b | 20.2 | F | TTAGAGCCACAAGAGACAACCAG | ||

| S 11a | 11 | 25.5 | F | TAGGATTCAACCCTGGAAGC | CAAGGCTTCCTCAATTCTCCACCCTTCC |

| R* | CCAGCATGCACCTGACTAACA | ||||

| S 11b | 7.3 | F | CCCTGGATCGCCGTGAA | ||

| GAPDH | F | GGACTGAGGCTCCCACCTTT | CATCCAAGACTGGCTCCTCCCTGC | ||

| R | GCATGGACTGTGGTCTGCAA |

Eleven biallelic genetic systems were used (S 01 to S 11). For 3 genetic systems (S 02, S 03, S 06), only one allele was found to be informative. Chromosome location, percentage of informativity evaluated on 63 donor/recipient pairs, and sequence of probes and primers are indicated. In the majority of cases (all except the S 07 system), one primer was common for both alleles. GAPDH was the constant genetic system used as active reference.

S 01, S 03, and S 04 markers were selected from references 31, 32, and 33, respectively.

FAM indicates 6-carboxyfluorescein; TAMRA, 6-carboxy-tetramethyl-rhodamine; F, forward primer; R, reverse primer; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase.

Common primer.

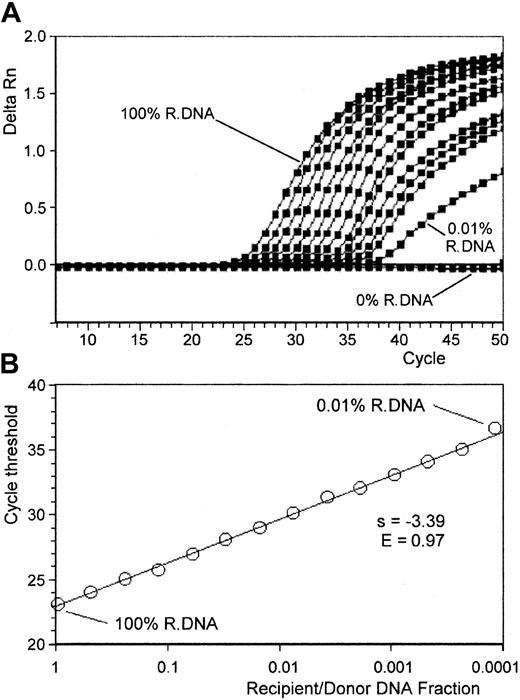

Validity and sensitivity of the assay

Each selected polymorphism was tested by means of an artificial reconstruction mixture of varying percentages of informative pretransplant recipient and donor DNAs to determine the validity and the sensitivity of the method. Using 14 serial halved dilutions, we simulated a range of mixed chimerisms varying from 100% to 0.01%. In addition, a negative control (100% donor DNA for recipient marker amplification and the converse for donor marker amplification) was included in the assay. All the experiments were run twice. Figure1A shows specific amplification plots of 14 different overlaid PCR amplifications obtained from such a dilution experiment. The amplifications were performed on a 1:2 serial dilution. The amplification plots shift to the right to higher threshold cycles as the input target quantity is reduced. As expected, the Ct values increased by approximately 1 for each 2-fold dilution until a point that defined the limits of method sensitivity. To provide an experimental margin for error, this point was defined as the dilution point before linearity was disrupted. This point reached at least 0.1% for all the systems tested. For instance, for the genetic marker, illustrated in Figure 1, the last dilution giving linear results was 0.02%, resulting in a sensitivity of 0.05%. Beyond this dilution, Ct values were not considered interpretable. No amplification was visualized for the negative control until cycle 50. Figure 1B represents the Ct values plotted versus the relative amount of target DNA. In this example, PCR efficiency derived from the curve slope was E = 0.97. In our experience, the standard curve slope values ranged between −3.58 and −3.21, corresponding to PCR efficiency exceeding 0.9. Starting with an amount of 250 ng, quantification of target DNA was shown to be linear over 3 logs (correlation coefficient greater than 0.98), and the assay can measure as few as 37 copies of DNA per tube (theoretical value corresponding to 0.05% of 250 ng). With the use of higher amounts of DNA, lower fractions (less than 0.05%) of target sequence can be determined without ambiguity with the same limit as 37 DNA copies.

Standardized amplification curves made with serial dilutions of recipient/donor DNA.

Artificial chimeric DNA samples were made with serial dilutions of recipient DNA in donor DNA (14 serial halved dilutions from 100% to 0.01% of recipient DNA in a total amount of 250 ng chimeric DNA). (A) ABI PRISM 7700 recipient-specific marker ΔRn curves for the 14 chimeric DNA samples. Regular positive amplification curves are observed until 0.01% recipient DNA dilution, and ΔRn curves shift to the right as recipient DNA fraction decreased. By contrast, no amplification occurred with the donor DNA (0% recipient DNA, used as a negative control for recipient-specific marker amplification). (B) The recipient marker standardized amplification curve plotted from these results: recipient marker Ct values correlated linearly with the logarithm of recipient/donor DNA fraction (r = 0.995). PCR efficiency derived from the slope of the curve was E = 0.97 for this assay.

Standardized amplification curves made with serial dilutions of recipient/donor DNA.

Artificial chimeric DNA samples were made with serial dilutions of recipient DNA in donor DNA (14 serial halved dilutions from 100% to 0.01% of recipient DNA in a total amount of 250 ng chimeric DNA). (A) ABI PRISM 7700 recipient-specific marker ΔRn curves for the 14 chimeric DNA samples. Regular positive amplification curves are observed until 0.01% recipient DNA dilution, and ΔRn curves shift to the right as recipient DNA fraction decreased. By contrast, no amplification occurred with the donor DNA (0% recipient DNA, used as a negative control for recipient-specific marker amplification). (B) The recipient marker standardized amplification curve plotted from these results: recipient marker Ct values correlated linearly with the logarithm of recipient/donor DNA fraction (r = 0.995). PCR efficiency derived from the slope of the curve was E = 0.97 for this assay.

Unknown sample quantification: precision and accuracy

To assess the effective performance of real-time PCR chimerism assay in posttransplantation monitoring, 80 post-BMT samples from 12 recipient/donor pairs were studied. In an initial step, pre-BMT recipient and donor DNAs were genotyped for all the biallelic genetic systems by conventional PCR to determine 2 markers specific, respectively, for the donor and the recipient.

For the chimerism quantification, 3 different PCRs were independently conducted for each assay sample: the recipient-specific marker PCR, the donor-specific marker PCR, and the active reference PCR. The active reference system allows normalization for any minor variations in input DNA concentration in the calibrator and in the unknown sample. In addition to the assay sample, for the recipient genetic-profile analysis, 2 standard curves were plotted (target system and active reference system) from pre-BMT recipient DNA as described above and were used to assess the sensitivity of the assay and to determine PCR efficiency. For the donor genetic-profile analysis, the donor DNA was used in the same conditions.

Each PCR was performed in duplicate. Mean intra-assay variation of Ct values evaluated on the 160 duplicates (80 recipient and 80 donor marker analysis) was 0.15 (range, 0.00-0.56). Moreover, to test the reproducibility of the assay, 47 experiments were replicated twice, on each of 2 separate days (Figure2). For a final quantification of a genotype expressed as a fraction (F), mean SD in the final quantification was F ± 0.22 F for these 47 pairs of results. As shown in Figure 2, such reproducibility allows for an extremely accurate absolute quantification of a minor marker, although quantification of a major marker appears to be less accurate. This drawback in the precision obtained for the major genetic profile in the sample is explained by the actual principle of PCR methodology, with a variation as low as 1 Ct leading to 100% variation in the final quantification. In our series, 44 of the 47 pairs of results showed a reproducibility of F ± 0.4 F, corresponding to real-time PCR precision of ± 0.5 Ct.

Reproducibility of real-time quantification PCR chimerism assay.

A total of 47 post–allo-BMT DNA samples were analyzed twice, once on each of 2 separate days. The figure shows results from the second assay (vertical axis) plotted against results from the first assay (horizontal axis). The margin for error is proportional to the value of each genotype fraction (F) and is F ± 0.4 F. This margin for error roughly corresponds to a Ct measurement error of ± 0.5 Ct.

Reproducibility of real-time quantification PCR chimerism assay.

A total of 47 post–allo-BMT DNA samples were analyzed twice, once on each of 2 separate days. The figure shows results from the second assay (vertical axis) plotted against results from the first assay (horizontal axis). The margin for error is proportional to the value of each genotype fraction (F) and is F ± 0.4 F. This margin for error roughly corresponds to a Ct measurement error of ± 0.5 Ct.

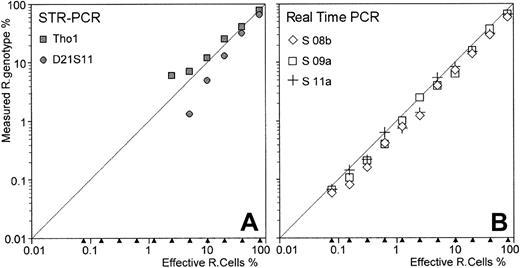

Comparison between fluorescent-based PCR analysis of STR and real-time PCR chimerism assays

As described in “Patients, materials, and methods,” this comparison was made on 11 artificial chimeric DNA samples extending over the entire assumed range of sensitivity of real-time PCR chimerism assay. For fluorescent-based PCR assay, only 2 markers (Tho1 and D21S11) were informative among the 3 tested. Recipient genotype fractions were detected until the 2.5% recipient cell fraction with Tho1 marker, and until the 5% recipient cell fraction with D21S11 marker (Table 2). Peak area analysis for D21S11, shown in Figure 3 for 3 DNA mixtures (40%, 10%, and 1.25% recipient cell fractions), demonstrated underestimation of recipient genotype fraction, most likely related to PCR competition bias between shorter donor- and longer recipient-specific alleles. Moreover, some discrepancies appear between Tho1 and D21S11 results as recipient cell fraction decreased (Table 2 and Figure4A).

Comparison of short tandem repeat polymerase chain reaction and real-time polymerase chain reaction results

| Effective recipient cells, % . | Measured recipient genotype, % . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STR-PCR . | Real-time PCR . | ||||

| Tho1 . | D21S11 . | S 08b . | S 09a . | S 11a . | |

| 80 | 78 | 72 | 58 | 65 | 65 |

| 40 | 40 | 31 | 29 | 35 | 30 |

| 20 | 25 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 15 |

| 10 | 12 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 8 |

| 5 | 7 | 1.3 | 4 | 4 | 5.5 |

| 2.5 | 6 | nd | 1.20 | 2.50 | 1.40 |

| 1.25 | nd | nd | 0.80 | 0.99 | 0.73 |

| 0.62 | nd | nd | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.63 |

| 0.31 | nd | nd | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.22 |

| 0.15 | nd | nd | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| 0.07 | nd | nd | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Effective recipient cells, % . | Measured recipient genotype, % . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STR-PCR . | Real-time PCR . | ||||

| Tho1 . | D21S11 . | S 08b . | S 09a . | S 11a . | |

| 80 | 78 | 72 | 58 | 65 | 65 |

| 40 | 40 | 31 | 29 | 35 | 30 |

| 20 | 25 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 15 |

| 10 | 12 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 8 |

| 5 | 7 | 1.3 | 4 | 4 | 5.5 |

| 2.5 | 6 | nd | 1.20 | 2.50 | 1.40 |

| 1.25 | nd | nd | 0.80 | 0.99 | 0.73 |

| 0.62 | nd | nd | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.63 |

| 0.31 | nd | nd | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.22 |

| 0.15 | nd | nd | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| 0.07 | nd | nd | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

Effective percentage of recipient cells in donor cells for the 11 artificial cell mixtures and recipient genotype percentages measured with 2 informative markers by short tandem repeat–polymerase chain reaction assay and 3 recipient-specific markers by real-time polymerase chain reaction assay are indicated.

STR indicates short tandem repeat; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; nd, recipient genotype not detected.

Comparison of STR-PCR and real-time PCR chimerism assays.

DNA extracted from different cell mixtures was evaluated for recipient genotype fraction by both fluorescent-based STR-PCR and real-time PCR chimerism assays. Panels A, C, and E show the results obtained on 3 DNAs (until the 1.25% recipient cell fraction) with STR-PCR using the D21S11 marker. Recipient-specific alleles (black peaks) and donor-specific alleles (gray peaks) define peak areas proportional to each individual-genotype fraction. In this case, longer recipient genotype–specific alleles seem less efficiently amplified than shorter donor alleles. Panels B, D, and F show the results obtained with real-time PCR on 3 DNAs (until the 0.15% recipient cell fraction). As the recipient cell fraction decreased in amplified DNA, amplification curves of allelic marker S 09a, specific for recipient genotype (black dotted lines), shift to the right; by contrast, amplification curves of the allelic marker S 09b, specific for the donor genotype, shift slightly to the left. In fact, these specific amplifications were independently performed in real-time PCR assay, and the sensitivity level for minor genotype detection is greatly improved, compared with STR-PCR assay results (compare panels E and F).

Comparison of STR-PCR and real-time PCR chimerism assays.

DNA extracted from different cell mixtures was evaluated for recipient genotype fraction by both fluorescent-based STR-PCR and real-time PCR chimerism assays. Panels A, C, and E show the results obtained on 3 DNAs (until the 1.25% recipient cell fraction) with STR-PCR using the D21S11 marker. Recipient-specific alleles (black peaks) and donor-specific alleles (gray peaks) define peak areas proportional to each individual-genotype fraction. In this case, longer recipient genotype–specific alleles seem less efficiently amplified than shorter donor alleles. Panels B, D, and F show the results obtained with real-time PCR on 3 DNAs (until the 0.15% recipient cell fraction). As the recipient cell fraction decreased in amplified DNA, amplification curves of allelic marker S 09a, specific for recipient genotype (black dotted lines), shift to the right; by contrast, amplification curves of the allelic marker S 09b, specific for the donor genotype, shift slightly to the left. In fact, these specific amplifications were independently performed in real-time PCR assay, and the sensitivity level for minor genotype detection is greatly improved, compared with STR-PCR assay results (compare panels E and F).

Comparison of STR-PCR and real-time PCR assays.

Eleven artificial cell mixtures, containing decreasing proportions of recipient cells in donor cells, were constructed. DNA extracted from these cell mixtures was evaluated by both fluorescent-based STR-PCR assay (with the 2 informative Tho1 and D21S11 markers) and real-time PCR assay (with the 3 recipient-specific markers S 08b, S 09a, and S 11a). In the STR-PCR results (A), recipient genotypes were detected until the 5% and 2.5% recipient cell fraction with D21S11 and Tho1 STR markers, respectively. In addition, these 2 STRs evidenced diverging results as the recipient genotype fraction decreased. In the real-time PCR assay (B), recipient genotypes were detected and properly quantified until 0.07% recipient cell fraction, regardless of the allelic marker used.

Comparison of STR-PCR and real-time PCR assays.

Eleven artificial cell mixtures, containing decreasing proportions of recipient cells in donor cells, were constructed. DNA extracted from these cell mixtures was evaluated by both fluorescent-based STR-PCR assay (with the 2 informative Tho1 and D21S11 markers) and real-time PCR assay (with the 3 recipient-specific markers S 08b, S 09a, and S 11a). In the STR-PCR results (A), recipient genotypes were detected until the 5% and 2.5% recipient cell fraction with D21S11 and Tho1 STR markers, respectively. In addition, these 2 STRs evidenced diverging results as the recipient genotype fraction decreased. In the real-time PCR assay (B), recipient genotypes were detected and properly quantified until 0.07% recipient cell fraction, regardless of the allelic marker used.

Real-time PCR results were compared with these STR-PCR results. First, genotyping of recipient and donor was performed, and 3 allelic markers (S 08b, S 09a, and S 11a) of the 19 tested were found to be specific to the recipient genotype. Thus, we analyzed all chimeric DNAs for recipient genotype quantification with these 3 informative recipient-specific alleles (Table 2). In contrast to STR-PCR assay, recipient genotype fractions were detected and quantified close to the expected values for all the 11 chimeric DNA samples and for each allelic marker tested. Figure 3 shows amplification curves of S 09a recipient-specific marker, overlaid with S 09b donor-specific marker amplification curves for 3 DNA mixtures (40%, 10%, and 0.15% recipient cell fractions). As these 2 specific alleles (and also the active reference monomorphic gene) were actually independently amplified, no competition bias occurred in the real-time PCR assay. Moreover, as illustrated in Table 2 and Figure 4, the 3 different pairs of primers used for recipient genotype quantification in the real-time PCR assay performed equivalently in terms of sensitivity and linearity.

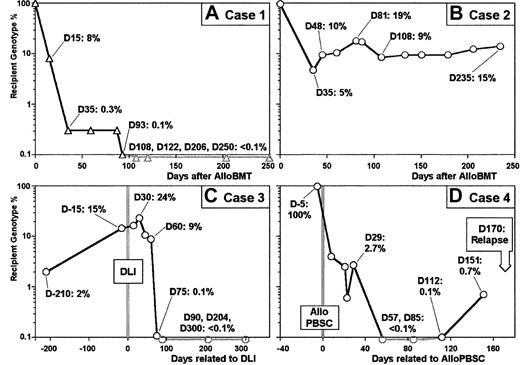

Clinical results

Four clinical situations showing the potential usefulness and limits of studying chimerism are illustrated as follows. All patients except for case 3 received HLA-identical sibling bone marrow.

Case 1.

This is a 16-year-old female with stage IV anaplastic non-Hodgkin lymphoma CD30+ NPM/ALK+with blood and bone marrow involvement. She underwent an allogenic bone marrow transplant with good partial response after salvage therapy following relapse. The patient is alive and well in complete remission (CR) 7 months after undergoing BMT: RT-PCR and PCR analysis for NPM/ALK and TCR-γ rearrangement, respectively, do not show evidence of minimal residual disease (MRD) in bone marrow. Figure5A shows the progressive decrease in recipient cells within 200 days after transplantation. As early as day 35 after infusion, the percentage of recipient cells was less than 1%, and residual recipient cells were undetectable at day 108.

Real-time quantitative PCR chimerism determination.

(A) Recipient genotype percentages assessed from 10 post–allo-BMT DNA samples (vertical axis) are plotted against time after allo-BMT (horizontal axis) for clinical case 1 (see text). Complete donor chimerism (day 108) followed decrease of recipient genotype percentage (day 0 to day 93) after allo-BMT. (B) Recipient genotype percentages assessed from 12 post–allo-BMT DNA samples (vertical axis) are plotted against time after allo-BMT (horizontal axis) for clinical case 2 (see text). Decrease of recipient genotype percentage (day 35) is followed by stable mixed chimerism until day 235. (C) Recipient genotype percentages assessed from 10 post–allo-BMT DNA samples are plotted against time centered around DLI date for clinical case 3 (see text). Mixed chimerism associated with the relapse (day 210 and day 15) is followed 2 months after DLI by a decrease (day 60 and day 75) and a disappearance of recipient genotype fraction (days 90, 204, and 300). (D) Recipient genotype percentages assessed from 9 post–allo-BMT DNA samples are plotted against time centered around the allogenic peripheral blood stem cell (allo-PBSC) infusion date for clinical case 4 (see text). Mixed chimerism associated with first relapse (day 5) is followed after chemotherapy and allo-PBSC infusion by recipient genotype percentage decrease and disappearance (day 57). Reappearance of recipient genotype fraction is observed in 2 DNA samples (day 112 and day 151) before diagnosis of second relapse.

Real-time quantitative PCR chimerism determination.

(A) Recipient genotype percentages assessed from 10 post–allo-BMT DNA samples (vertical axis) are plotted against time after allo-BMT (horizontal axis) for clinical case 1 (see text). Complete donor chimerism (day 108) followed decrease of recipient genotype percentage (day 0 to day 93) after allo-BMT. (B) Recipient genotype percentages assessed from 12 post–allo-BMT DNA samples (vertical axis) are plotted against time after allo-BMT (horizontal axis) for clinical case 2 (see text). Decrease of recipient genotype percentage (day 35) is followed by stable mixed chimerism until day 235. (C) Recipient genotype percentages assessed from 10 post–allo-BMT DNA samples are plotted against time centered around DLI date for clinical case 3 (see text). Mixed chimerism associated with the relapse (day 210 and day 15) is followed 2 months after DLI by a decrease (day 60 and day 75) and a disappearance of recipient genotype fraction (days 90, 204, and 300). (D) Recipient genotype percentages assessed from 9 post–allo-BMT DNA samples are plotted against time centered around the allogenic peripheral blood stem cell (allo-PBSC) infusion date for clinical case 4 (see text). Mixed chimerism associated with first relapse (day 5) is followed after chemotherapy and allo-PBSC infusion by recipient genotype percentage decrease and disappearance (day 57). Reappearance of recipient genotype fraction is observed in 2 DNA samples (day 112 and day 151) before diagnosis of second relapse.

Case 2.

This is a 51-year-old male with stage III follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma who was undergoing BMT in CR2 6 years after initial diagnosis. At 6 months after the BMT, the patient is still in CR with negative bone marrow biopsy and no evidence of Bcl2 rearrangement. The results of chimerism analysis are shown in Figure 5B. The percentage of autologous cells dropped from 100% to 5% on day 35 after transplantation, followed by stable mixed chimerism (10% recipient cells) for 7 months.

Case 3.

This is a 48-year-old female who underwent a molecular and cytogenetic relapse of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) 10 years after receiving a bone marrow transplant from an HLA-identical unrelated donor. She received 1 × 107 CD3+ cells per kilogram from the same donor and entered molecular and cytogenetic CR. Recipient cell fraction was undetectable at day 90 after DLI, as illustrated in Figure 5C.

Case 4.

This is a 22-year-old female who underwent BMT in CR1 of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). At 12 months later, she relapsed and received high-dose chemotherapy (high dose cytarabine and etoposide and mitoxantrone), followed 10 days later by peripheral blood stem cell transplantation from her donor. Figure 5D shows chimerism kinetics during the follow-up of this second allogenic transplantation. The recipient cell fraction progressively decreased and was undetectable from day 57 until day 112. Interestingly, reappearance of recipient cells was detected at day 112 (0.1%) and confirmed at day 151 (0.7%), 19 days before the second sudden AML relapse diagnosed upon blast reappearance in peripheral blood.

Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to explore the applicability of TaqMan real-time quantitative PCR technology for quantitative assessment of mixed chimerism after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Chimerism evaluation after allo-BMT is crucial in several situations. Formankova et al24 have shown that increasing mixed chimerism in 10 CML patients after BMT correlated with an increasing signal of MRD. Recently, Serrano et al6 reported monitoring CML relapse after BMT by using the chimerism assessment in myeloid cells in association with p190BCR-ABL messenger RNA. The study of residual host hematopoiesis after BMT may be of particular interest in hematological malignancies where specific tumor markers are not available. In fact, several studies showed that chimerism status closely parallels disease evolution7,25-28 and can be used to indicate prognosis. Furthermore, in new strategies, such as nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation,16 measurement of donor chimerism after transplantation is a prerequisite for manipulating engraftment by altering patient immunosuppression and by DLI. In this respect, recent research by Childs et al29emphasizes the importance of monitoring posttransplantation chimerism following nonmyeloablative procedures and suggests that the establishment of full-donor T-lymphoid chimerism is an important factor in determining GVHD and graft-versus-leukemia effects. For all these clinical applications, the optimal methodological approach needs to be informative, sensitive, and quantitatively accurate.

Here, we described a new method that is based on the TaqMan technology and that fits all these criteria. Compared with XY-FISH methodology, which is applicable only in sex-mismatched situations, a selection of 11 human genetic loci enabled easy discrimination of more than 90% of recipient/donor pairs. We tested the linearity and sensitivity of the method in DNA dilution experiments. A linear correlation with anr between 0.98 and 0.99 was found for all markers, and a sensitivity of 0.1% proved reproducible, which was higher than that obtained by fluorescent-based PCR of multiplex amplification of STR30 and comparable to that achieved with radioactive labeling. Moreover, standard PCR-based methods evaluate the quantity of PCR product at the plateau phase, whose level depends on a large number of variables. By contrast, the real-time quantitative PCR procedure measures the quantity of PCR product at the onset of the exponential phase, which is directly proportional to the initial amount of the target DNA sequence. Furthermore, variable-number tandem repeats or STR-PCR procedures are based on the assumption that the alleles of donor and recipient should be amplified in the same tube without any competition despite the use of the same pair of primers. In the procedure used here, each allele was separately amplified by means of a specific pair of primers. We clearly demonstrated the greater sensitivity and linearity of real-time PCR chimerism assay over fluorescent-based STR-PCR, using a panel of 11 artificial chimeric DNA cell mixtures. One log10 gain in sensitivity was achieved by means of the real-time PCR chimerism assay. Moreover, the accuracy and sensitivity levels appear to be independent of the specific markers used, and more reliable results are obtained for minor genotype detection and quantification than with the STR-PCR assay. Despite the high accuracy and precision of our approach in the detection of small percentages of host or donor DNA, as in all PCR-based methods, it is difficult to achieve precision higher than 40%, as discussed above. However, since one crucial point in clinical situations is to detect significant variations in low ranges early, this precision level appears satisfactory in practical use. Another advantage of the real-time PCR procedure is that whatever the genetic system tested, the same cycling conditions are used, providing the ability to analyze more than one marker in the same run and therefore to test different recipient/donor pairs simultaneously. Moreover, the practicability of the assay allows a final result in fewer than 48 hours.

From a clinical point of view, recipient/donor chimerism evaluation cannot necessarily be correlated with MRD-specific evaluation, as illustrated in case 2, where persistence of recipient cells around 10% could not be related to resurgence of malignant cells. Further evaluation is needed to understand this kind of profile. However, quantitative evaluation of chimerism often appears to be closely related to therapeutic events and to disease-free status, as illustrated in clinical cases 1, 3, and 4.

In cases 1 and 3, which showed both progressive decrease and disappearance of recipient genotype fraction after either allo-BMT or DLI, the time needed to obtain a complete donor chimerism profile is related to the assay sensitivity level, reaching 3 months at the 0.1% minor genotype detection threshold. This relationship between time and detection threshold is illustrated in case 4 for minor recipient genotype reappearance, supporting the benefit of high sensitivity level for relapse prediction. In this case, a sudden second relapse of AML, diagnosed on day 170 after allo-PBSC infusion, was preceded by reappearance at day 112 and a further increase at day 151 of recipient genotype fraction with very low levels (probably undetectable with the STR-PCR method). Thus, information provided by the high sensitivity level of real-time PCR chimerism assay may be of great interest in assessing the diagnosis of hematological or medullar relapse early. All together, these clinical cases evidenced the advantage of real-time PCR chimerism assay and underlined the need for prospective studies to further evaluate the relationship between chimerism status and clinical events.

In conclusion, in the present report, we propose a new assay for rapid, sensitive, and accurate measurement of post-BMT chimerism based on real-time quantitative PCR. This new assay, which can be carried out through a single PCR run, appears to be a valuable diagnostic tool for monitoring engraftment in more than 90% of recipient/donor pairs, even in sex-matched related pairs, with a reproducible sensitivity of up to 1:1000 cells. Serial and quantitative analysis of hematopoietic chimerism in patients with allogenic transplants may help to identify those with a high risk of relapse and to set up immunomodulation therapeutic strategies such as DLI. Moreover, in allogenic nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation, the induction of mixed chimerism, which has to be precisely evaluated, provides a platform for the delivery of adoptive cellular immunotherapy with DLI, whose effects also require monitoring by quantitative analysis of chimerism.

We would like to thank Marie-Antoinette Le Gall and Tracey Westcott for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Supported by grants from the Ligue Contre le Cancer 56, ADHO Bretagne, and PHRC 2001.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Erwann Quelvennec, Laboratoire Universitaire d'Immunologie, Faculté de Médecine, 2 Avenue du Pr Léon Bernard, CS 34317, 35043 Rennes cedex, France; e-mail:erwann.quelvennec@univ-rennes1.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal