Key Points

Fetal MLL::ENL expression conveys a selective disadvantage leading to loss of self-renewal programs, myeloid bias, and leukemia resistance.

MLL3 enforces AML resistance following fetal MLL::ENL exposure, whereas cooperating mutations can overcome the resistant state.

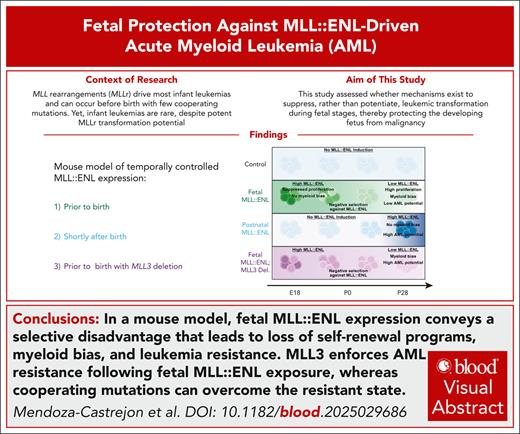

Visual Abstract

MLL rearrangements (MLLrs) are the most common cause of congenital and infant leukemias. MLLrs arise prior to birth and can transform fetal/neonatal progenitors with the help of only a few additional cooperating mutations. Despite the low threshold for transformation, infant leukemias are rare, and congenital leukemias, which arise before birth, are even less common. These observations raise the question of whether mechanisms exist to suppress leukemic transformation during fetal life, thereby protecting the developing fetus from malignancy during a period of rapid hematopoietic progenitor expansion. To test this possibility, we used a mouse model of temporally controlled MLL::ENL expression to show that fetal MLL::ENL exposure establishes a heritable, leukemia-resistant state within hematopoietic progenitors that persists after birth. When we induced MLL::ENL expression prior to birth and transplanted hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, very few recipient mice developed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) despite robust engraftment. When we induced MLL::ENL expression shortly after birth, all recipient mice developed a highly penetrant AML. Fetal MLL::ENL expression imposed a negative selective pressure on hematopoietic progenitors before birth followed by loss of self-renewal gene expression and enhanced myeloid differentiation after birth that precluded transformation. These changes did not occur when MLL::ENL expression initiated shortly after birth. The fetal barrier to transformation was enforced by the histone methyltransferase MLL3, and it could be overcome by cooperating mutations, such as NrasG12D. Heritable fetal protection against leukemic transformation may contribute to the low incidence of congenital and infant leukemias in humans.

Introduction

Infant leukemias are rare, difficult-to-treat malignancies that occur in the first year of life and are genetically distinct from later childhood and adult leukemias.1-3 Approximately 50% of infant acute myeloid leukemias (AML) and ∼70% of infant B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias (B-ALL) carry an MLL/KMT2A rearrangement (MLLr) as the primary driver mutation.3,4 Infant leukemias are thought to arise from a fetal cell of origin that acquires a prenatal MLLr.5-10 They carry fewer cooperating mutations than adult leukemias,2,3 suggesting that fetal/neonatal progenitors might be particularly prone to transformation. Indeed, prior studies with either mouse or human models have shown that MLL fusion proteins transform fetal/neonatal hematopoietic progenitors more efficiently than adult progenitors.11-13 This has become a working explanation for both the high frequencies at which MLLr occur in infant leukemias and the relatively small number of cooperating mutations required for transformation.

Despite its simplicity, other lines of evidence argue against a model in which fetal blood progenitors are efficiently transformed by MLLr mutations. While MLLr cause a high percentage of infant leukemias, the overall incidence of MLLr infant leukemia is actually quite low. The incidence of infant AML is only ∼15 cases per million, ∼20-fold lower than the incidence of AML in a 70-year old.14 The incidence of congenital leukemia (ie, leukemias that occur before birth) is lower still (∼3 cases per million).14,15 When also accounting for lymphoblastic leukemias, the incidence of congenital leukemias is ∼10-fold lower than infant leukemias and >100-fold lower than childhood leukemia overall.14 This is counterintuitive for 2 reasons. First, fetal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and multipotent progenitors (MPPs) divide more rapidly than postnatal HSCs and MPPs,16 thus affording MLLr clones ample opportunity to expand before birth. Second, as noted earlier, only a small number of cooperating mutations are required for infant leukemias to transform. In principle, these factors suggest that congenital leukemias should occur more frequently than they actually do. It is possible that the low incidence of congenital and infant leukemias simply reflects high integrity of the genome early in life, despite high rates of cell proliferation, but these observations nevertheless raise the question of whether additional mechanisms exist to suppress leukemic transformation during fetal ontogeny.

In prior work, we used a doxycycline-inducible model of MLL::ENL-driven AML to test whether AML initiation efficiency changes with age.13 We found that mice with a doxycycline-regulated MLL::ENL transgene (Tet-Off-ME mice) developed AML with greatest penetrance when MLL::ENL was induced shortly after birth rather than before birth.13 This observation suggests that fetal progenitors may resist AML initiation, and that leukemias that do emerge from fetal cells of origin must overcome intrinsic or extrinsic barriers to transformation that are not present in neonatal cells. The underlying mechanisms remain unclear. We and others showed that a fetal-specific RNA binding protein, LIN28B, can actively suppress MLL::ENL-driven leukemogenesis.13,17 However, in subsequent loss-of-function studies, we showed that genetic inactivation of Lin28b failed to accelerate leukemogenesis after fetal MLL::ENL induction.18 Additional mechanisms must help protect against transformation when MLL::ENL is expressed before birth.

We now show that MLL::ENL imposes a negative selective pressure on fetal progenitors that leads to a heritable, AML-resistant state. MLL::ENL suppresses fetal HSC/MPP proliferation to an extent not seen after birth. Furthermore, fetal MLL::ENL induction leads to a postnatal decline in expression of select stemness genes (eg, Pbx1, Nkx2-3, Myct1, and Hlf), and it enhances postnatal myeloid priming. The heritable, AML-resistant state is enforced by MLL3, an epigenetic regulator that promotes myeloid differentiation. Cooperating mutations, such as NrasG12D, can overcome fetal-derived AML resistance, thus affording a path to transformation. Our data argue for a nuanced interpretation of how ontogeny influences leukemogenesis. In addition to conveying lasting epigenomic changes to infant leukemias,19 fetal identity affords a layer of protection against malignant transformation that dissipates after birth.

Methods

Mouse lines

Flow cytometry

CITE-seq and scATAC-seq library construction, sequencing, and analysis

Cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes followed by sequencing (CITE-seq) and single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (scATAC-seq) were performed using the 10x Genomics platforms. Complete details are provided in the supplemental Methods.

EdU and cell cycle assays

EdU (5-ethynyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine; Invitrogen) was administered by intraperitoneal injections (100 mg/kg per dose) given every 8 hours beginning 24 hours prior to bone marrow or fetal liver harvest. Assays were performed using the AF488 Click-it Plus EdU Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Molecular Probes, C10633). Cell cycle analyses were performed by fixing stained cells with Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer (BD Biosciences) and then staining with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole).

CRISPR/Cas9 editing and transplantations

Lineage–Sca1+Kit+ (LSKs)/granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs) were cultured overnight and electroporated with guide RNA (gRNA)/Cas9 complexes. Complete details are provided in the supplemental Methods.

All procedures were performed according to an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee–approved protocol at Washington University School of Medicine.

Results

MLL::ENL induction in fetal progenitors conveys heritable protection against transformation

Prior work with a mouse model of temporally controlled MLL::ENL expression showed that postnatal MLL::ENL induction leads to faster and more penetrant AML initiation than fetal induction.13 The approach utilized Vav1-Cre; Rosa26LSL-tTA; Col1a1TetO-MLL::ENL (Tet-Off-ME) mice in which blood-specific Vav1-Cre induced tet-transactivator (tTA) expression in hematopoietic progenitors at embryonic day (E)10.5. The tTA then drove MLL::ENL expression in the absence of doxycycline. Mice developed AML with 61% penetrance and a median survival of 204 days following fetal MLL::ENL induction.13 When MLL::ENL expression was suppressed with doxycycline until postnatal day (P)0, Tet-Off-ME mice developed AML with 100% penetrance and a median survival of 127 days.13 Thus, fetal MLL::ENL exposure caused a delay in AML initiation, relative to postnatal induction, that persisted well after birth. This observation suggests that MLL::ENL reprograms fetal hematopoietic progenitors toward an AML-resistant state that is heritable across multiple cell divisions.

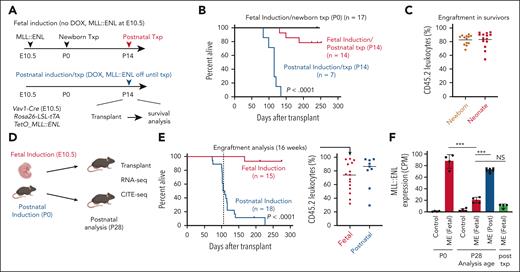

To test whether fetal MLL::ENL exposure conveys heritable protection against AML, we induced MLL::ENL in Tet-Off-ME mice at E10.5 and then transplanted P0 or P14 progenitors into adult recipient mice (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1A-B). None of the recipients of P0 liver cells, and only a minority of recipients of P14 cells, developed AML despite high levels of donor cell engraftment (Figure 1B-C; supplemental Figure 1C). In contrast, when we suppressed MLL::ENL expression until P14 and then induced transgene expression in conjunction with transplantation, we observed rapid-onset AML in all recipient mice (Figure 1A-B; supplemental Figure 1D-E). Thus, fetal but not postnatal MLL::ENL induction elicits heritable changes in hematopoietic progenitors that limit transformation potential even after transplantation into adult recipient mice.

Fetal MLL::ENL (ME) induction conveys heritable protection against leukemogenesis. (A) Summary of experimental design for ME induction and transplantation experiments. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for recipient mice transplanted with 300 000 P0 liver cells or 500 LSK cells after ME induction at E10.5 or P14. (C) Donor (CD45.2) leukocyte engraftment in surviving recipient mice at 8 months after transplantation. (D) Summary of experimental design for panels E-F and for CITE-seq experiments in Figure 2. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curves and 16-week donor chimerism for recipient mice after ME induction at E10.5 or P0, and transplantation at P28. (F) ME transgene expression (CPM) based on RNA sequencing. n = 4 biological replicates per group, ∗∗∗P < .001 by 1-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test. For all survival curves, group sizes and P values are shown in the panels. P values were calculated by the log-rank test. CPM, counts per million; DOX, doxycycline; txp, transplant.

Fetal MLL::ENL (ME) induction conveys heritable protection against leukemogenesis. (A) Summary of experimental design for ME induction and transplantation experiments. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for recipient mice transplanted with 300 000 P0 liver cells or 500 LSK cells after ME induction at E10.5 or P14. (C) Donor (CD45.2) leukocyte engraftment in surviving recipient mice at 8 months after transplantation. (D) Summary of experimental design for panels E-F and for CITE-seq experiments in Figure 2. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curves and 16-week donor chimerism for recipient mice after ME induction at E10.5 or P0, and transplantation at P28. (F) ME transgene expression (CPM) based on RNA sequencing. n = 4 biological replicates per group, ∗∗∗P < .001 by 1-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test. For all survival curves, group sizes and P values are shown in the panels. P values were calculated by the log-rank test. CPM, counts per million; DOX, doxycycline; txp, transplant.

We repeated the fetal and postnatal induction and transplantation experiments with a slightly altered time line so that parallel gene expression profiling experiments could be performed, and so that MLL::ENL transgene expression could be assessed. We induced MLL::ENL before or after birth and then isolated LSK cells at P28 for transplantation and RNA sequencing (Figure 1D). We also isolated LSK cells from P0 mice and recipient mice (∼8 months after transplant) to quantify expression of the human MLL::ENL transgene. Transplantation assays redemonstrated a profound difference in recipient survival after fetal and postnatal MLL::ENL induction (Figure 1E). After fetal induction, MLL::ENL was highly expressed at P0, indicating robust transgene induction, but expression levels dropped by P28 and remained low after transplantation (Figure 1F). MLL::ENL expression in HSCs/MPPs remained low even into adulthood after fetal induction, relative to fully transformed AML (supplemental Figure 2A). In contrast, MLL::ENL expression was high at P28 following doxycycline removal at P0 (Figure 1F). Postnatal and posttransplant declines in transgene expression were not observed when another transgene, Tet-Off-H2B-GFP, was expressed from the Col1a1 locus (supplemental Figure 2B-C). Thus, age-related differences in MLL::ENL expression are not attributable to nonspecific differences in regulation of the Rosa26LSL-tTA or Col1a1 loci. The data suggest that MLL::ENL imposes a negative selective pressure on fetal progenitors that favors outgrowth of cells with low transgene expression and limited transformation potential.

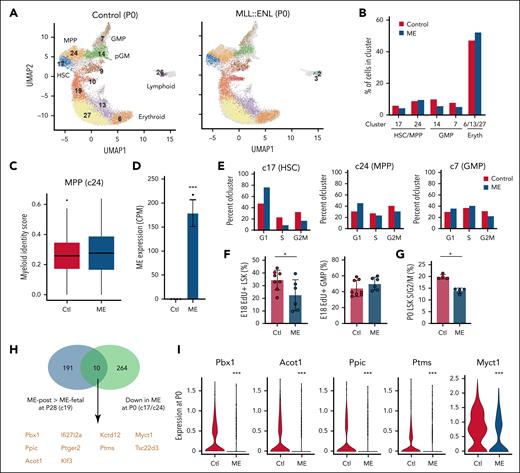

Fetal MLL::ENL induction causes precocious myeloid differentiation and loss of stemness gene expression after birth

To understand how MLL::ENL differentially regulates gene expression and cell identity after fetal and postnatal induction, we performed CITE-seq on P28 Lineage–Kit+ (LK) progenitors after fetal or postnatal MLL::ENL induction (Figure 1D; supplemental Table 1). Cre– littermates were included as controls. In the postnatal induction cohort, progenitors were exposed to MLL::ENL for 1 to 2 weeks after doxycycline removal at P0, based on analysis of analogously treated Tet-Off-H2B-GFP mice that showed delayed transgene induction due to prolonged doxycycline clearance (supplemental Figure 2D). CITE-seq data were analyzed by Iterative Clustering with Guide-gene Selection, version 2,23 to generate clusters and uniform manifold approximation and projection plots. We annotated the clusters based on surface marker phenotypes and gene expression (Figure 2A-B; supplemental Figure 3A-B). Slingshot24 was used to infer differentiation trajectories, which appeared similar in wild-type and MLL::ENL-expressing cells irrespective of when MLL::ENL was induced (Figure 2A). Clusters containing CD150+CD48–LSK HSCs and CD48+LSK MPPs (clusters 19 and 29, respectively) were underrepresented after fetal MLL::ENL induction, relative to the control group (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 3C). Likewise, clusters containing Lineage–Sca1–c-Kit+CD16/32– pre-GMPs (pGMs) and Lineage–Sca1–Kit+CD16/32+ GMPs, clusters 12, 22, and 9, were overrepresented after fetal MLL::ENL induction (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 3C). These shifts were not observed after postnatal induction (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 3D). Flow cytometry also demonstrated greater depletion of HSC and MPP populations after fetal MLL::ENL induction than after postnatal induction (supplemental Figure 3E-H). MLL::ENL transcript expression was lower in both HSC/MPP and pGM/GMP clusters after fetal induction than after postnatal induction, consistent with bulk RNA sequencing results (Figure 2E). However, known MLL::ENL targets, such as Hoxa9, Hoxa10, and Mecom, were still upregulated after fetal induction (Figure 2F; supplemental Figure 4A). Altogether, the data show that fetal MLL::ENL induction leads to a postnatal reduction in HSC/MPP frequency, increased myeloid differentiation, and selection against cells with high oncogene expression.

Fetal ME induction enhances postnatal myeloid priming. (A) UMAPs representing single-cell gene expression in P28 LK cells after fetal or postnatal ME induction. Controls reflect Cre– littermates. Black lines reflect differentiation trajectories as calculated by Slingshot. (B) Cell identities by cluster based on surface marker phenotypes. (C-D) Distribution of cells within indicated clusters of P28 LK progenitors following fetal or postnatal ME induction. ∗∗∗P < .001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (E) MLL::ENL transgene expression in all clusters (left panel), HSC/MPP (c19, middle panel), and pGM/GMP (c12/22, right panel) based on alignment of the human MLL::ENL transcript in n = 4 pseudoreplicates. ∗∗∗P < .001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (F) Hoxa9 expression in control and ME-expressing HSCs/MPPs (cluster 19), ∗∗∗P < .001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (G) Quadratic programming-derived myeloid identity scores for clusters along the HSC/MPP to GMP-neu trajectory in P28 wild-type mice. (H) Histogram showing distribution of myeloid identity score in all cells along the HSC/MPP to GMP-neu trajectory after fetal or postnatal ME induction. (I) Distribution of myeloid identity score in all cells and immature myeloid progenitors (c19 and c29) after fetal or postnatal ME induction. ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (J) EdU incorporation for P28 LSKs and GMPs following E10.5 ME induction. ∗∗P < .01 by Student t test. (K) Expression of self-renewal genes in HSCs/MPPs after fetal or postnatal ME induction. ∗∗∗P < .001 relative to age-matched control by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Ctl, control; N.S., not significant; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

Fetal ME induction enhances postnatal myeloid priming. (A) UMAPs representing single-cell gene expression in P28 LK cells after fetal or postnatal ME induction. Controls reflect Cre– littermates. Black lines reflect differentiation trajectories as calculated by Slingshot. (B) Cell identities by cluster based on surface marker phenotypes. (C-D) Distribution of cells within indicated clusters of P28 LK progenitors following fetal or postnatal ME induction. ∗∗∗P < .001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (E) MLL::ENL transgene expression in all clusters (left panel), HSC/MPP (c19, middle panel), and pGM/GMP (c12/22, right panel) based on alignment of the human MLL::ENL transcript in n = 4 pseudoreplicates. ∗∗∗P < .001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (F) Hoxa9 expression in control and ME-expressing HSCs/MPPs (cluster 19), ∗∗∗P < .001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (G) Quadratic programming-derived myeloid identity scores for clusters along the HSC/MPP to GMP-neu trajectory in P28 wild-type mice. (H) Histogram showing distribution of myeloid identity score in all cells along the HSC/MPP to GMP-neu trajectory after fetal or postnatal ME induction. (I) Distribution of myeloid identity score in all cells and immature myeloid progenitors (c19 and c29) after fetal or postnatal ME induction. ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (J) EdU incorporation for P28 LSKs and GMPs following E10.5 ME induction. ∗∗P < .01 by Student t test. (K) Expression of self-renewal genes in HSCs/MPPs after fetal or postnatal ME induction. ∗∗∗P < .001 relative to age-matched control by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Ctl, control; N.S., not significant; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

To better quantify the degree of myeloid differentiation that occurs in HSCs and MPPs following fetal MLL::ENL induction, we used quadratic programming to assign myeloid identity scores to each cluster along the HSC to GMP/neutrophil (neu) differentiation trajectory (Figure 2A,G).25 Each cell was assigned a score between 0 and 1 based on expression of genes that distinguished the HSC/MPP cluster 19 from the GMP/neu cluster 12 in wild-type P28 mice (Figure 2G). Fetal MLL::ENL induction increased myeloid identity scores across the entire differentiation trajectory, including HSC/MPP and MPP/pGM clusters (Figure 2H-I). Postnatal MLL::ENL induction also drove a statistically significant increase in myeloid differentiation, but to a far less extent than was observed after fetal induction (Figure 2I). Thus, fetal MLL::ENL induction enhances myeloid priming after birth, even in HSCs and MPPs.

We next performed pseudobulk gene expression analysis for HSC/MPP and pGM/GMP clusters, followed by gene set enrichment analysis and gene set variance analysis to identify genes and gene signatures that distinguish fetal and postnatal induction cohorts (supplemental Table 2). MYC targets, E2F targets, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)-associated genes, and oxidative phosphorylation-associated genes were all elevated after fetal but not postnatal MLL::ENL induction, particularly in the HSC/MPP cluster (supplemental Figure 4B-D). In addition, a higher percentage of HSC/MPP cells appeared to be in S-phase after fetal MLL::ENL induction than after postnatal induction (supplemental Figure 4E). EdU incorporation assays confirmed that P28 HSCs/MPPs cycle more frequently after fetal but not postnatal MLL::ENL induction, relative to controls (Figure 2J). MLL::ENL did not alter GMP proliferation after either induction age (supplemental Figure 4F). Fetal MLL::ENL induction significantly reduced expression of several self-renewal genes within the HSC/MPP cluster, including Hlf, Pbx1, Nkx2-3, and Myct1 (Figure 2K; supplemental Figure 4G). This was not observed after postnatal induction. Thus, fetal MLL::ENL induction leads to postnatal transcriptional changes in HSCs/MPPs that enhance myeloid priming, reduce self-renewal, and increase proliferation rates.

MLL::ENL drives precocious myeloid gene expression without corresponding changes in chromatin architecture

We next tested whether MLL::ENL elicits changes in chromatin accessibility after fetal and postnatal induction, given that fetal resistance to AML initiation is heritable across cell divisions and, thus, potentially sustained through epigenome remodeling. We induced MLL::ENL before or after birth, and isolated LK cells at P28 for scATAC-seq. The cells were clustered using ArchR.26 CITE-seq data were then integrated to annotate clusters based on gene expression and to assess concordance between differentiation states, as defined by chromatin accessibility and gene expression (Figure 3A-B). scATAC-seq cluster distributions were surprisingly similar after fetal and postnatal MLL::ENL induction (Figure 3A,C). Furthermore, there was clear discordance between cluster assignments that were based solely on chromatin accessibility and assignments based on integrated CITE-seq transcript data. For example, scATAC-seq clusters 6 and 3 had cells assigned to CITE-seq clusters 22 (pGM) or 12 (GMP-neu) based on integrated transcript expression. A lower percentage of cells in each scATAC-seq cluster were defined, transcriptionally, as pGM after fetal MLL::ENL induction than after postnatal induction, and a greater percentage were defined as GMP-neu (Figure 3D) despite having similar chromatin accessibility profiles. To quantify these changes in individual cells, we performed quadratic programming on cells in each scATAC-seq cluster using integrated CITE-seq data from Figure 2. For every scATAC-seq cluster, the degree of myeloid bias, as defined by integrated transcript expression, was significantly higher after fetal MLL::ENL induction than after postnatal induction (Figure 3E). Thus, fetal MLL::ENL exposure causes precocious myeloid differentiation at the transcript level without altering chromatin accessibility.

Fetal ME induction causes myeloid-biased gene expression without altering chromatin accessibility. (A) UMAP representing control and ME-expressing P28 LK cells based on scATAC-seq profiles. Clustering was performed in ArchR. (B) Cluster assignments based on inferred gene expression. The assignments follow the clustering nomenclature specified in Figure 2A. (C) Distribution of cells from fetal and postnatal ME induction groups within scATAC-seq clusters. (D) Inferred CITE-seq identities for cells within scATAC-seq clusters 3 and 6. (E) Myeloid identity scores, based on quadratic programming using integrated CITE-seq data, for cells within the indicated scATAC-seq clusters after fetal or postnatal ME induction. (F) Pseudotime analysis of transcription factors with concordant differential expression (based on integrated CITE-seq data) and motif accessibility (based on scATAC-seq) through the course of myeloid differentiation, after fetal or postnatal ME induction. Genes in red were identified in both cohorts. The trajectory is shown above the heat map. (G) Sox4, Mef2c, and Mybl2 transcript expression in individual cells, projected as heat maps on the UMAPs from panel A. Ranges of min/max expression are identical for fetal and postnatal induction cohorts for each gene. (H) Enrichment for SOX4, MEF2C, and MYBL2 motifs within individual cells, projected as heat maps. min, minimum; max, maximum; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

Fetal ME induction causes myeloid-biased gene expression without altering chromatin accessibility. (A) UMAP representing control and ME-expressing P28 LK cells based on scATAC-seq profiles. Clustering was performed in ArchR. (B) Cluster assignments based on inferred gene expression. The assignments follow the clustering nomenclature specified in Figure 2A. (C) Distribution of cells from fetal and postnatal ME induction groups within scATAC-seq clusters. (D) Inferred CITE-seq identities for cells within scATAC-seq clusters 3 and 6. (E) Myeloid identity scores, based on quadratic programming using integrated CITE-seq data, for cells within the indicated scATAC-seq clusters after fetal or postnatal ME induction. (F) Pseudotime analysis of transcription factors with concordant differential expression (based on integrated CITE-seq data) and motif accessibility (based on scATAC-seq) through the course of myeloid differentiation, after fetal or postnatal ME induction. Genes in red were identified in both cohorts. The trajectory is shown above the heat map. (G) Sox4, Mef2c, and Mybl2 transcript expression in individual cells, projected as heat maps on the UMAPs from panel A. Ranges of min/max expression are identical for fetal and postnatal induction cohorts for each gene. (H) Enrichment for SOX4, MEF2C, and MYBL2 motifs within individual cells, projected as heat maps. min, minimum; max, maximum; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

We next compared differentiation programs of MLL::ENL-expressing progenitors after fetal and postnatal induction. We plotted a myeloid differentiation trajectory in pseudotime and identified transcription factors that (1) were differentially expressed through the course of myeloid differentiation based on integrated CITE-seq data, and (2) had corresponding changes in binding site accessibility (Figure 3F). We observed distinct patterns of transcription factor expression between the 2 induction ages (Figure 3G; supplemental Figure 5A). For example, 2 transcription factors that have known roles in maintaining stemness, Sox4 and Mef2c,27,28 were expressed more diffusely and at higher levels after postnatal induction than after fetal induction (Figure 3G). In contrast, Mybl2, a transcription factor with an established role in myeloid differentiation,29 was more highly and diffusely expressed after fetal MLL::ENL induction (Figure 3G). Despite clear differences in transcription factor expression, binding site accessibility patterns were largely identical between the fetal and postnatal induction groups (Figure 3H; supplemental Figure 5B), underscoring the discordance between effects of MLL::ENL on gene expression and chromatin accessibility.

MLL::ENL suppresses HSC/MPP proliferation during late gestation

We next evaluated MLL::ENL-dependent changes in gene expression in newborn mice, given that the selective pressure against MLL::ENL expression is established during this time period. We performed CITE-seq on P0 control and Tet-Off-ME LK progenitors after fetal MLL::ENL induction (supplemental Table 1). We clustered and annotated cells based on gene expression and surface marker phenotypes (Figure 4A; supplemental Figure 6A). Unlike what was observed at P28, fetal MLL::ENL induction did not cause precocious myeloid differentiation at P0. HSC, MPP, and GMP cluster frequencies and myeloid identity scores were similar between the control and MLL::ENL-expressing samples (Figure 4A-D). MLL::ENL appeared to suppress HSC proliferation, in contrast to the enhanced proliferation that was evident at P28 (Figure 4E). EdU incorporation and cell cycle assays confirmed that MLL::ENL suppresses HSC/MPP proliferation during late gestation and at birth, though GMP proliferation was unaffected (Figure 4F-G; supplemental Figure 6B).

Fetal ME induction suppresses HSC/MPP proliferation during late gestation. (A) UMAP representing P0 LK cells, cluster identities, and annotation based on CITE-seq performed after fetal ME induction. (B) Cluster distributions from control and ME-expressing cohorts. (C) Myeloid identity scores for cells in MPP cluster 24, as calculated by quadratic programming. (D) MLL::ENL transgene expression in HSC cluster 17 based on n = 4 pseudoreplicates. ∗∗∗P < .001. (E) Percent of cells within HSC (c17), MPP (c24), and GMP (c7) clusters at indicated cell cycle phases based on single-cell gene expression. (F) EdU incorporation in E18 LSK and GMP cells. n = 8 mice for control and n = 6 mice for Tet-Off-ME samples, ∗P < .05 by 2-tailed Student t test. (G) Percent of P0 LSK cells in S/G2/M phase of the cell cycle. n = 4 per group, ∗P < .05 by 2-tailed Student t test. (H) Venn diagram indicating genes that are more highly expressed in HSC/MPP clusters after postnatal ME induction relative to fetal induction, and genes that are downregulated by ME at P0 after fetal induction. (I) Expression of a subset of genes from the overlap in panel H. ∗∗∗P < .001 based on Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Ctl, control; Eryth, erythroid; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

Fetal ME induction suppresses HSC/MPP proliferation during late gestation. (A) UMAP representing P0 LK cells, cluster identities, and annotation based on CITE-seq performed after fetal ME induction. (B) Cluster distributions from control and ME-expressing cohorts. (C) Myeloid identity scores for cells in MPP cluster 24, as calculated by quadratic programming. (D) MLL::ENL transgene expression in HSC cluster 17 based on n = 4 pseudoreplicates. ∗∗∗P < .001. (E) Percent of cells within HSC (c17), MPP (c24), and GMP (c7) clusters at indicated cell cycle phases based on single-cell gene expression. (F) EdU incorporation in E18 LSK and GMP cells. n = 8 mice for control and n = 6 mice for Tet-Off-ME samples, ∗P < .05 by 2-tailed Student t test. (G) Percent of P0 LSK cells in S/G2/M phase of the cell cycle. n = 4 per group, ∗P < .05 by 2-tailed Student t test. (H) Venn diagram indicating genes that are more highly expressed in HSC/MPP clusters after postnatal ME induction relative to fetal induction, and genes that are downregulated by ME at P0 after fetal induction. (I) Expression of a subset of genes from the overlap in panel H. ∗∗∗P < .001 based on Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Ctl, control; Eryth, erythroid; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

We compared the transcriptional profiles of P0 HSCs/MPPs to P28 HSCs/MPPs with the goal of identifying genes that distinguish the developmental stages. MLL::ENL drove expression of a large number of genes in P0 HSCs/MPPs when compared to controls. These included several Hoxa family genes, as well as known fetal regulators such as Lin28b and Hmga2, consistent with prior observations (supplemental Table 3).13 We looked for genes that were upregulated after postnatal MLL::ENL induction but downregulated after fetal MLL::ENL induction, anticipating that this list might include genes that maintain stemness. Of 201 genes that were more highly expressed in P28 HSCs/MPPs after postnatal MLL::ENL induction, 10 were downregulated at P0 after fetal MLL::ENL induction (Figure 4G-H; supplemental Table 4). These included self-renewal genes Pbx1 and Myct1. For the most part, the overlapping genes were expressed at consistent levels throughout the course of normal ontogeny (supplemental Figure 7). Pbx1 and Myct1 were expressed primarily in HSCs/MPPs, and fully transformed pediatric AML (which is usually monocytic)30,31 demonstrated only low levels of expression (supplemental Table 4).3 Thus, fetal MLL::ENL exposure leads to reduced expression of a subset of self-renewal genes in neonatal HSCs/MPPs, in addition to suppressing proliferation. These changes coincide with emergence of an AML-resistant state.

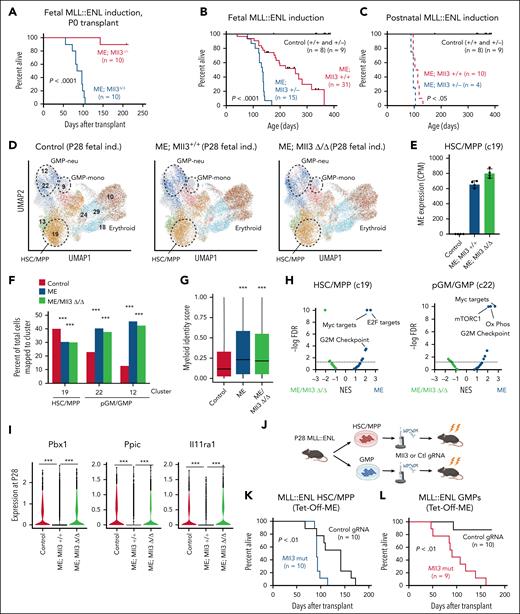

MLL3 enforces AML resistance in myeloid-primed, MLL::ENL-expressing progenitors

We next sought mechanisms that maintain the fetal barrier to AML initiation. The lack of MLL::ENL-dependent changes in chromatin accessibility argued against chromatin remodeling factors, but persistence of the AML-resistant state, even after transplantation, argued for an epigenetic mechanism. We focused our attention on MLL3, a histone methyltransferase that promotes HSC and GMP differentiation but does not modulate bulk ATAC-seq profiles of HSCs, MPPs, or GMPs.20 While Mll3 itself is not differentially expressed through ontogeny or in response to MLL::ENL (supplemental Figure 8A-F), it has been shown to limit HSC self-renewal capacity, promote MPP differentiation, and restrict GMP expansion and mobilization in response to cytokine stimulation.20,32 Thus, Mll3 has critical roles in modulating normal hematopoiesis. Furthermore, MLL3 is an established myeloid tumor suppressor protein,33 and inherited deleterious variants at the human MLL3 locus have been associated with infant leukemogenesis.34 Finally, MLL3 has been shown to compete with MLL1/MENIN complexes to promote myeloid differentiation in MLLr AML cells.35 These observations raised the question of whether MLL3 helps maintain an AML-resistant state after fetal MLL::ENL induction.

To test whether Mll3 helps maintain the heritable fetal-derived AML barrier, we crossed Tet-Off-ME mice to previously described Mll3f/f mice,20,32 induced MLL::ENL at E10.5 and transplanted P0 liver progenitors as in Figure 1A. As expected, almost all recipients of Mll3+/+ LK cells survived >200 days after transplant (Figure 5A). In contrast, all recipients of Mll3-deficient (Mll3Δ/Δ) cells died with a median survival of 90 days (Figure 5A), indicating a role for MLL3 in sustained AML resistance. We next crossed Tet-Off-ME mice to Mll3+/− mice, and evaluated survival after fetal or postnatal MLL::ENL induction without performing transplants. As in prior experiments, fetal MLL::ENL induction on an Mll3+/+ background led to AML but with incomplete penetrance and long latency (Figure 5B). Deleting just a single Mll3 allele greatly accelerated AML onset (Figure 5B). Mll3 deletion had only a modest effect on leukemogenesis after postnatal MLL::ENL induction (Figure 5C). Mll3+/− AML had reduced expression of genes associated with cell cycle expression relative to Mll3+/+ AML, but canonical MLL::ENL target genes were not differentially expressed (supplemental Figure 8G). Altogether, these data show that MLL3 is necessary to maintain AML resistance after fetal MLL::ENL induction.

Mll3 sustains a leukemia-resistant state in myeloid-primed ME-expressing postnatal progenitors. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for recipients of Tet-Off-ME; Mll3Δ/Δ P0 liver cells after fetal ME induction. (B-C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Tet-Off-ME; Mll3+/+ and Tet-Off-ME; Mll3+/− mice after fetal or postnatal ME induction. (D) UMAPs representing CITE-seq profiles for P28 LK cells from control, Tet-Off-ME; Mll3+/+, and Tet-Off-ME; Mll3Δ/Δ mice. Cluster annotations were assigned based on Symphony alignment to the data shown in Figure 2A. (E) MLL::ENL transgene expression in HSC/MPP cluster 19. (F) Percentages of cells for each genotype in clusters 19, 22, and 12. (G) Distribution of myeloid identity scores in all cells along the HSC/MPP to GMP/neu trajectory, as calculated by quadratic programming. ∗∗∗P < .001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (H) Volcano plots showing normalized enrichment scores and false discovery rates for Hallmark gene sets, as calculated from 4 pseudoreplicates per genotype for the HSC/MPP and pGM/GMP populations. (I) Expression of Pbx1, Ppic, and Il11ra1 in HSC/MPP clusters at P28 after fetal ME induction. ∗∗∗P < .001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (J) Approach to mutagenize Mll3 in HSCs/MPPs and GMPs from P28 Tet-Off-ME mice after postnatal induction. (K-L) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for recipients of Tet-Off-ME HSCs/MPPs (K) or GMPs (L) after targeted mutagenesis of an intragenic region on chromosome 8 or Mll3. For all survival curves, group sizes and P values are shown in the panels. P values are indicated and were calculated by the log-rank test. Ctl, control; CPM, counts per million; gRNA, guide RNA; NES, normalized enrichment score; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

Mll3 sustains a leukemia-resistant state in myeloid-primed ME-expressing postnatal progenitors. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for recipients of Tet-Off-ME; Mll3Δ/Δ P0 liver cells after fetal ME induction. (B-C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Tet-Off-ME; Mll3+/+ and Tet-Off-ME; Mll3+/− mice after fetal or postnatal ME induction. (D) UMAPs representing CITE-seq profiles for P28 LK cells from control, Tet-Off-ME; Mll3+/+, and Tet-Off-ME; Mll3Δ/Δ mice. Cluster annotations were assigned based on Symphony alignment to the data shown in Figure 2A. (E) MLL::ENL transgene expression in HSC/MPP cluster 19. (F) Percentages of cells for each genotype in clusters 19, 22, and 12. (G) Distribution of myeloid identity scores in all cells along the HSC/MPP to GMP/neu trajectory, as calculated by quadratic programming. ∗∗∗P < .001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (H) Volcano plots showing normalized enrichment scores and false discovery rates for Hallmark gene sets, as calculated from 4 pseudoreplicates per genotype for the HSC/MPP and pGM/GMP populations. (I) Expression of Pbx1, Ppic, and Il11ra1 in HSC/MPP clusters at P28 after fetal ME induction. ∗∗∗P < .001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (J) Approach to mutagenize Mll3 in HSCs/MPPs and GMPs from P28 Tet-Off-ME mice after postnatal induction. (K-L) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for recipients of Tet-Off-ME HSCs/MPPs (K) or GMPs (L) after targeted mutagenesis of an intragenic region on chromosome 8 or Mll3. For all survival curves, group sizes and P values are shown in the panels. P values are indicated and were calculated by the log-rank test. Ctl, control; CPM, counts per million; gRNA, guide RNA; NES, normalized enrichment score; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

To determine how MLL3 contributes to sustained AML resistance, we performed CITE-seq on Tet-Off-ME; Mll3+/+ and Tet-Off-ME; Mll3Δ/Δ LK progenitors harvested at P28 after MLL::ENL induction at E10.5 (supplemental Table 1). We used Symphony36 to assign cells to clusters using the same identities as were assigned in Figure 2A so that we could evaluate changes in cluster distribution and myeloid priming consistently across the different experiments (Figure 5D). MLL::ENL transcript expression was comparable between the Mll3+/+ and Mll3Δ/Δ populations (Figure 5E). Thus, Mll3 deletion did not accelerate leukemogenesis by enhancing MLL::ENL expression. MLL::ENL-dependent myeloid priming occurred in both Tet-Off-ME; Mll3+/+ and Tet-Off-ME; Mll3Δ/Δ progenitors (Figure 5F-G), indicating that MLL3 is not necessary to enforce myeloid bias after fetal MLL::ENL induction. However, Mll3 deletion mitigated the changes in metabolic and cell cycle gene expression that were evident following fetal MLL::ENL induction (Figure 5H), and it modestly but significantly enhanced expression of Hoxa9 and Meis1 (supplemental Figure 9A-B). Furthermore, a subset of genes that were downregulated following fetal MLL::ENL induction, including Pbx1, Ppic, and Il11ra1, were not downregulated in Tet-Off-ME; Mll3Δ/Δ progenitors (Figure 5I; supplemental Table 5).

We performed similar CITE-seq experiments at P0 to determine whether Mll3 modulates responses to MLL::ENL prior to birth (supplemental Figure 9C-D; supplemental Tables 1 and 5). Indeed, several of the genes that were upregulated in Tet-Off-ME; Mll3Δ/Δ HSCs/MPPs and pGMs/GMPs at P28 were also upregulated in corresponding cell populations at P0. These again included Pbx1, Ppic, and Il11ra1. Altogether, these data show that MLL3 restricts the capacity of myeloid-primed cells to transform after fetal MLL::ENL induction, rather than enforcing the myeloid bias itself. Furthermore, MLL3 modulates transcriptional responses to MLL::ENL in multiple progenitor populations, even prior to birth.

In light of these findings, we tested whether Mll3 deficiency enables efficient transformation of MLL::ENL-expressing GMPs, as one might expect if MLL3 enforces a barrier to transformation in myeloid-biased cells. Prior work has shown that MPPs, pGMs, and GMPs can all serve as a cell of origin for MLL::ENL-driven AML, but GMPs are much less efficiently transformed.21 We induced MLL::ENL postnatally in Tet-Off-ME mice and isolated HSCs/MPPs (LSK cells) or GMPs at P28. We used CRISPR/Cas9 to mutate Mll3 and transplanted 4000 cells per recipient into lethally irradiated recipient mice (Figure 5J). As expected for the postnatal induction age, all recipients of Tet-Off-ME HSCs/MPPs developed AML, though Mll3 deletion significantly reduced survival time (Figure 5K). Very few recipients of control Tet-Off-ME GMPs developed AML, whereas all recipients of Mll3 mutated GMPs succumbed to AML (Figure 5L). Thus, MLL3 enforces an AML-resistant state in myeloid committed progenitors.

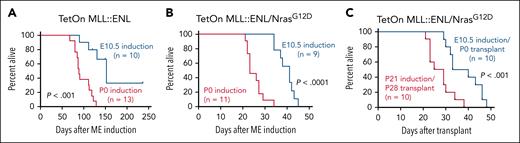

RAS pathway activation overrides fetal AML resistance

We next tested whether an NrasG12D mutation could enable rapid AML initiation, even after fetal MLL::ENL induction, given that RAS pathway mutations are common in infant leukemias, and RAS pathway mutations have been shown to enhance transformation of GMPs.2,3,37,38 For these experiments, we generated mice with Tet-On-ME alleles (Vav1-Cre; Rosa26LSL-rtTA; Col1a1TetO-MLL::ENL), with or without a Cre-inducible NrasG12D allele.39 We induced MLL::ENL expression at either E10.5 or P0 and monitored survival of the progeny. In the absence of NrasG12D, fetal MLL::ENL induction led to incompletely penetrant AML initiation with a median survival of ∼5 months (Figure 6A). Postnatal induction caused fully penetrant AML with a median survival of ∼3 months (Figure 6A). These findings are similar to what we previously observed using the Tet-Off-ME model.13 All Tet-On-ME/NrasG12D mice developed AML, though latency was significantly longer after fetal MLL::ENL induction as compared to postnatal induction (Figure 6B). When we transplanted Tet-On-ME/NrasG12D progenitors, all recipients developed AML, albeit with longer latency after fetal as compared to postnatal MLL::ENL induction (Figure 6C). Thus, cooperating mutations, such as NrasG12D, can overcome heritable AML resistance after fetal MLL::ENL induction.

NrasG12D cooperating mutation overcomes heritable resistance to AML initiation. (A-B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves after E10.5 or P0 ME induction using Tet-On-ME and Tet-On-ME/NrasG12D models. (C) Survival curves of recipient mice after transplantation of P0 or P28 LSK after ME induction at E10.5 or P21, respectively. P values are indicated and were calculated by the log-rank test.

NrasG12D cooperating mutation overcomes heritable resistance to AML initiation. (A-B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves after E10.5 or P0 ME induction using Tet-On-ME and Tet-On-ME/NrasG12D models. (C) Survival curves of recipient mice after transplantation of P0 or P28 LSK after ME induction at E10.5 or P21, respectively. P values are indicated and were calculated by the log-rank test.

Discussion

Our data offer a potential explanation for why congenital and infant leukemias are rare despite high rates of prenatal progenitor expansion, documented prenatal acquisition of MLLr, and low mutation thresholds required for transformation. MLL::ENL imposes a negative selective pressure that is much stronger when the mutation arises before birth rather than after birth. The fusion protein suppresses fetal HSC/MPP proliferation to an extent not seen after birth (Figures 2 and 3), and it imposes different transcriptional changes in fetal progenitors than in adult progenitors. These differences could reflect temporally distinct binding sites for the fusion protein, interactions with heterochronic transcription factors, or differences between fetal liver and postnatal bone marrow microenvironments that favor transformation during neonatal and juvenile stages of life. The negative selective pressure conveyed by fetal MLL::ENL ultimately leads to postnatal outgrowth of progenitors that maintain only low levels of MLL::ENL expression, and that lose critical stemness programs in favor of precocious myeloid differentiation (Figure 2). The changes are heritable across multiple cell divisions and likely epigenetic in nature, given that they persist after transplantation.

While corresponding events are difficult to resolve in human fetuses, the murine data suggest that when an MLLr occurs during human fetal hematopoiesis, affected progenitors will usually differentiate toward stable, nonmalignant fates rather than progressing to AML or B-ALL. This may seem counterintuitive in light of prior studies showing that infant leukemias, particularly B-ALL, co-opt oncofetal programs.40,41 However, our murine data do not challenge the prior human studies. Instead, they add a critical layer of nuance. Infant leukemias, when they arise, retain extant features of their fetal cells of origin, but transformation events may nevertheless be rare because most fetal progenitors are hard wired to resist transformation. Future efforts to model MLLr leukemia initiation in human fetal or umbilical cord blood progenitors will benefit from simultaneous efforts to characterize progenitors that do not give rise to leukemia. We anticipate fetal-specific transcriptional responses to MLL fusion proteins that limit transformation potential. It will be interesting to test whether fetal-specific responses differ between lymphoid and myeloid lineages.

The data raise the question as to why congenital and infant leukemias occur at all, given that expression of an MLL fusion protein in fetal progenitors conveys a sustained, selective disadvantage. It is important to note that the fetal barrier to transformation is relative rather than absolute, and we have identified 2 mechanisms that can circumvent it. First, a recurrent cooperating mutation, NrasG12D, did enable highly penetrant transformation even after fetal MLL::ENL induction (Figure 6). Second, Mll3 deletion mitigated the barrier by extending efficient transformation capacity to more differentiated progenitors, thus expanding the repertoire of potential cells of origin (Figure 5). Deleterious germ line variants in human MLL3 have been associated with infant leukemia predisposition.34 While that study described patients with non-MLLr infant AML, MLL3 variants may play a similar role in MLLr infant leukemogenesis. Altogether, the data suggest that after fetal progenitors acquire an MLLr, they have a narrow window of time to acquire additional cooperating mutations before they are outcompeted and lose leukemogenic potential. Germ line predisposition (eg, variants in MLL3 or other critical tumor suppressors) may lower the fetal barrier to transformation. These factors make infant and congenital leukemias rare, but not impossible.

One of the most fascinating aspects of developmental biology is that single blastocysts can expand exponentially to become trillion-celled organisms with near-perfect fidelity. The fidelity is not simply spatial and functional. It also reflects the absence of neoplasia in the setting of rapidly expanding, highly stimulated developmental fields. Our data suggest that low rates of in utero cancers may reflect active diversion of mutant cells toward nonmalignant fates, in addition to the lower mutation burdens inherent to early life.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Bryder for providing TetO-MLL::ENL mice.

This work was supported by grants to J.A.M. from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant R01HL152180), the National Cancer Institute, NIH (grant R01CA285272), Gabrielle's Angel Foundation, the Edward P. Evans Foundation, and the Children’s Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children's Hospital. J.M.-C. was supported by a National Cancer Institute, NIH career development grant (F31CA268923). J.A.M. is a Scholar of Blood Cancer United.

Authorship

Contribution: J.A.M. designed and oversaw all experiments, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript with J.M.-C.; J.M.-C. designed, conducted, and interpreted the experiments; W.Y. performed all bioinformatic analyses; E.D., H.C.W., E.B.C., R.M., R.M.P., J.Y., and Y.L. performed the experiments; R.C. interpreted data and performed experiments for Figure 5, particularly panels B and C; J.M.W. and L.F.Z.B. provided critical technical assistance; and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jeffrey A. Magee, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63110; email: mageej@wustl.edu.

References

Author notes

All cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes sequencing, single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing, and RNA sequencing data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE291041).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal