Key Points

D-R maintenance improved MRD-negative conversion rate in patients with NDMM who were MRD-positive after transplant vs R maintenance.

PFS favored D-R maintenance, with an improved 30-month PFS rate vs R alone, and D-R was well tolerated with no new safety concerns.

Visual Abstract

No randomized trial has directly compared daratumumab and lenalidomide (D-R) maintenance with standard-of-care lenalidomide (R) alone after transplant. Herein, we report the primary results of the phase 3 AURIGA study evaluating D-R vs R maintenance in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) who had very good or better partial response, were minimal residual disease (MRD)-positive (10–5) and anti-CD38–naïve after transplant. Two hundred patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to D-R (n = 99) or R (n = 101) maintenance for up to 36 cycles. The MRD-negative (10–5) conversion rate by 12 months from start of maintenance (primary end point) was significantly higher for D-R than R (50.5% vs 18.8%; odds ratio [OR], 4.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.37-8.57; P < .0001). MRD-negative (10–6) conversion rate was similarly higher with D-R (23.2% vs 5.0%; OR, 5.97; 95% CI, 2.15-16.58; P = .0002). At median follow-up (32.3 months), D-R achieved a higher overall MRD-negative (10–5) conversion rate (D-R, 60.6% vs R, 27.7%; OR, 4.12; 95% CI, 2.26-7.52; P < .0001) and complete response rate or better (75.8% vs 61.4%; OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.08-3.69; P = .0255) vs R. Progression-free survival (PFS) favored D-R vs R (hazard ratio, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.29-0.97); estimated 30-month PFS rates were 82.7% for D-R and 66.4% for R. Incidences of grade 3/4 cytopenias (54.2% vs 46.9%) and infections (18.8% vs 13.3%) were slightly higher with D-R than R. In conclusion, D-R maintenance achieved a higher MRD-negative conversion rate and improved PFS after transplant vs R, with no new safety concerns. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT03901963.

Introduction

Induction therapy followed by high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), consolidation, and maintenance with lenalidomide (R) is considered the standard of care (SoC) for transplant-eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM).1 Despite rapid advancements in multiple myeloma (MM) treatment, most patients ultimately relapse. Therefore, there is a continued need to optimize treatment strategies to improve depth of response and long-term outcomes, especially in the maintenance setting following frontline ASCT.

Although long-term clinical end points, such as progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival, remain the gold standard for identifying optimal treatment strategies, surrogate end points are used to provide reliable efficacy readouts at an earlier treatment stage, allowing for rapid and informed assessment of treatment options. The achievement of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity is associated with improved long-term outcomes2 and has evolved into an important clinical efficacy end point in clinical trials.3,4 In recognition of the increasingly important role of MRD, the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee recently voted unanimously in favor of using MRD testing as an early surrogate end point in myeloma clinical trials to support the accelerated approval of new treatments.5

Daratumumab is a human immunoglobulin G kappa monoclonal antibody targeting CD38, and is approved as monotherapy and in combination regimens for the treatment of relapsed or refractory MM, as well as combination therapy for NDMM.6,7 These approvals are based on many clinical studies of daratumumab combined with SoC regimens and encompass treatment regimens comprising multiple phases of therapy, including induction/consolidation and maintenance. To date, however, no randomized trial has directly compared daratumumab-based maintenance therapy with SoC maintenance therapy in transplant-eligible patients with NDMM.

The randomized phase 3 AURIGA study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier, NCT03901963) was designed to evaluate whether patients who were anti-CD38–naïve, were MRD-positive, and had achieved very good partial response or better (≥VGPR) after induction therapy and ASCT could achieve improved outcomes when daratumumab was added to the standard R maintenance therapy. Herein, we report the primary end point and key secondary efficacy and safety end points among patients in the AURIGA study.

Methods

Study design and oversight

This multicenter, randomized, open-label, active-controlled, phase 3 study enrolled patients between 4 June 2019 and 4 May 2023 from 52 sites across the United States and Canada. The study protocol and all amendments were approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each participating site. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use good clinical practice guidelines and the principles that originated in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study abided by all applicable regulatory and country-specific requirements, including institutional review board approval of the protocol and any required amendments. All patients provided written informed consent.

Patients

Eligible patients were aged 18 to 79 years, had NDMM with a history of ≥4 cycles of induction therapy, had received high-dose therapy and ASCT within 12 months of the start of induction therapy, and were within 6 months of ASCT on the date of study randomization. In addition, eligible patients must have achieved a ≥VGPR as assessed per International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) 2016 criteria at the time of screening,8 had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of 0 to 2, and were MRD-positive (threshold 10–5) according to next-generation sequencing (NGS) (Adaptive Biotechnologies, Seattle, WA) after ASCT at the time of screening. Patients with prior exposure to anti-CD38 therapies were excluded. Additional eligibility criteria are listed in the supplemental Methods (available on the Blood website).

Study treatments

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive daratumumab and lenalidomide (D-R) or R maintenance treatment. Randomization was stratified by cytogenetic risk per investigator’s assessment (standard risk/unknown vs high risk). High risk was defined as the presence of ≥1 of the following cytogenetic abnormalities: del(17p), t(4;14), and t(14;16).

All patients received 10-mg R daily starting from day 1 through day 28 of each 28-day cycle; after 3 cycles, the dose could be increased to 15 mg if tolerated and at the discretion of the investigator. Patients in the D-R group also received subcutaneous daratumumab (1800 mg coformulated with recombinant human hyaluronidase PH20 [2000 U/mL; ENHANZE drug delivery technology; Halozyme Therapeutics, Inc, San Diego, CA]) weekly during cycles 1 and 2, every 2 weeks during cycles 3 through 6, and every 4 weeks from cycle 7 onward (all 28-day cycles). Study treatment continued for a planned maximum duration of 36 cycles or until disease progression, unacceptably toxicity, or consent withdrawal. To prevent injection-related reactions, patients receiving daratumumab also received preinjection and postinjection medications (supplemental Methods). For the management of drug-related toxicities, R dose reductions or treatment schedule modifications were permitted per institutional standards. No dose modifications were permitted for daratumumab; daratumumab-related toxicities were instead managed using dose delay. After the end of the study treatment period of 36 months, patients benefiting from treatment with daratumumab and/or R could continue receiving treatment per investigator’s discretion.

End points and assessments

The primary end point was MRD-negative conversion rate by NGS from baseline to 12 months after maintenance treatment, defined as the proportion of patients who achieved MRD-negative status (threshold 10–5) by 12 months after the initiation of maintenance treatment and before progressive disease or subsequent antimyeloma therapy. Key secondary end points and their complete definitions are provided in the supplemental Methods.

MRD was assessed using NGS of bone marrow aspirate samples at a central laboratory (clonoSEQ; Adaptive Biotechnologies, Seattle, WA). MRD-negative status was assessed at a minimum sensitivity threshold of 10–5 (1 tumor cell per 105 nucleated cells). Bone marrow samples were collected at screening and after 12, 18, 24, and 36 months, with an accepted ±30-day window of the scheduled visit. Response and disease progression were assessed with a validated computerized algorithm in accordance with IMWG 2016 response criteria.8

Besides determination of cytogenetic risk by investigator assessment for stratification purposes, a separate analysis was conducted to determine cytogenetic risk at diagnosis using available local fluorescence in situ hybridization/karyotype test. Central and local cytogenetic data were not mixed to define high cytogenetic risk status for a patient. High-risk cytogenetics were evaluated both per the standard definition (≥1 of the following abnormalities: del[17p], t[4;14], and t[14;16]) and per the revised definition (also including t[14;20] and/or gain/amp[1q21]).

Statistical analysis

It was estimated that a sample size of approximately 214 patients (107 patients per group at a 1:1 randomization ratio) would be needed to demonstrate a 20% treatment difference in MRD-negative conversion rate by the end of 12 months of maintenance with a power of ≥85% and a 2-sided alpha of 0.05 using a continuity-corrected χ2 test. Because of recruitment challenges (eg, the COVID-19 pandemic and increased use of daratumumab during induction), trial enrollment ended after 200 patients had been randomly assigned, providing sufficient power (84%) to detect a 20% absolute difference in the primary end point. The primary analysis was conducted after all randomly assigned patients had completed 12 months of maintenance, had disease progression, died, or discontinued study treatment. The primary analysis was performed in the intention-to-treat population, defined as all patients who were randomly assigned to the study treatment.

The primary end point (MRD-negative conversion rate by 12 months of study treatment) was evaluated between treatment groups using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by the baseline cytogenetic risk per investigator’s assessment (high risk vs standard/unknown risk), as was used for randomization of the study. Common odds ratios (ORs) were estimated using a Mantel-Haenszel test, and 2-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. The P value was provided by Fisher exact test. The supplemental Methods section includes information on other categorical end points.

Results

Patients and treatment

A total of 200 patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to D-R maintenance (n = 99) or R maintenance alone (n = 101). Baseline demographic and disease characteristics were generally well balanced between treatment groups (Table 1). The median age of patients was 62 years (range, 35-78 years), 59.5% were male, 22.0% were Black, and 24.3% had International Staging System stage III disease at diagnosis. Among patients with evaluable cytogenetic risk data at diagnosis of MM, 20.4% (37/181) had high risk per the standard definition (D-R, 23.9% [22/92]; R, 16.9% [15/89]), and 34.1% (62/182) had high risk per the revised definition (D-R, 34.4% [32/93]; R, 33.7% [30/89]). Although treatment randomization was stratified by cytogenetic risk at study entry per investigator’s assessment, a higher percentage of patients were identified as having high cytogenetic risk at diagnosis in the D-R arm because of investigators mixing cytogenetic risk assessments; for randomization, some assessments were made based on screening cytogenetics and some on cytogenetics from diagnosis. Before study entry, patients in both treatment groups received a median of 5 (range, 4-8) induction cycles. Most patients received ≥2 induction cycles in which both bortezomib (V) and R were included as therapy components (D-R, 78.8% [78/99]; R, 83.2% [84/101]). Additional information on induction therapy is provided in the supplemental Results.

Patient demographic and disease characteristics in the ITT population

| . | D-R . | R . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | n = 99 | n = 101 |

| Median (range) | 63 (35-77) | 62 (35-78) |

| Category, n (%) | ||

| <65 | 61 (61.6) | 61 (60.4) |

| 65-70 | 23 (23.2) | 21 (20.8) |

| ≥70 | 15 (15.2) | 19 (18.8) |

| Sex, n (%) | n = 99 | n = 101 |

| Male | 61 (61.6) | 58 (57.4) |

| Female | 38 (38.4) | 43 (42.6) |

| Race, n (%) | n = 99 | n = 101 |

| White | 67 (67.7) | 68 (67.3) |

| Black or African American | 20 (20.2) | 24 (23.8) |

| Asian | 5 (5.1) | 1 (1.0) |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 0 | 1 (1.0) |

| Other∗ | 5 (5.1) | 5 (5.0) |

| Not reported | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| ECOG PS score, n (%) | n = 99 | n = 101 |

| 0 | 45 (45.5) | 55 (54.5) |

| 1 | 52 (52.5) | 44 (43.6) |

| 2 | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| ISS disease stage, n (%) | n = 91 | n = 98 |

| I | 40 (44.0) | 38 (38.8) |

| II | 28 (30.8) | 37 (37.8) |

| III | 23 (25.3) | 23 (23.5) |

| No. of induction cycles | n = 98 | n = 99 |

| Median (range) | 5.0 (4.0-8.0) | 5.0 (4.0-8.0) |

| Cytogenetic risk at diagnosis | n = 92 | n = 89 |

| Standard risk | 63 (68.5) | 66 (74.2) |

| High risk† | 22 (23.9) | 15 (16.9) |

| del(17p) | 13 (14.1) | 3 (3.4) |

| t(4;14) | 10 (10.9) | 12 (13.5) |

| t(14;16) | 6 (6.5) | 7 (7.9) |

| Unknown | 7 (7.6) | 8 (9.0) |

| Revised cytogenetic risk at diagnosis | n = 93 | n = 89 |

| Standard risk | 52 (55.9) | 53 (59.6) |

| High risk‡ | 32 (34.4) | 30 (33.7) |

| del(17p) | 13 (14.0) | 3 (3.4) |

| t(4;14) | 10 (10.8) | 12 (13.5) |

| t(14;16) | 6 (6.5) | 7 (7.9) |

| t(14;20) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) |

| gain/amp(1q21) | 16 (17.2) | 22 (24.7) |

| Unknown | 9 (9.7) | 6 (6.7) |

| . | D-R . | R . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | n = 99 | n = 101 |

| Median (range) | 63 (35-77) | 62 (35-78) |

| Category, n (%) | ||

| <65 | 61 (61.6) | 61 (60.4) |

| 65-70 | 23 (23.2) | 21 (20.8) |

| ≥70 | 15 (15.2) | 19 (18.8) |

| Sex, n (%) | n = 99 | n = 101 |

| Male | 61 (61.6) | 58 (57.4) |

| Female | 38 (38.4) | 43 (42.6) |

| Race, n (%) | n = 99 | n = 101 |

| White | 67 (67.7) | 68 (67.3) |

| Black or African American | 20 (20.2) | 24 (23.8) |

| Asian | 5 (5.1) | 1 (1.0) |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 0 | 1 (1.0) |

| Other∗ | 5 (5.1) | 5 (5.0) |

| Not reported | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| ECOG PS score, n (%) | n = 99 | n = 101 |

| 0 | 45 (45.5) | 55 (54.5) |

| 1 | 52 (52.5) | 44 (43.6) |

| 2 | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| ISS disease stage, n (%) | n = 91 | n = 98 |

| I | 40 (44.0) | 38 (38.8) |

| II | 28 (30.8) | 37 (37.8) |

| III | 23 (25.3) | 23 (23.5) |

| No. of induction cycles | n = 98 | n = 99 |

| Median (range) | 5.0 (4.0-8.0) | 5.0 (4.0-8.0) |

| Cytogenetic risk at diagnosis | n = 92 | n = 89 |

| Standard risk | 63 (68.5) | 66 (74.2) |

| High risk† | 22 (23.9) | 15 (16.9) |

| del(17p) | 13 (14.1) | 3 (3.4) |

| t(4;14) | 10 (10.9) | 12 (13.5) |

| t(14;16) | 6 (6.5) | 7 (7.9) |

| Unknown | 7 (7.6) | 8 (9.0) |

| Revised cytogenetic risk at diagnosis | n = 93 | n = 89 |

| Standard risk | 52 (55.9) | 53 (59.6) |

| High risk‡ | 32 (34.4) | 30 (33.7) |

| del(17p) | 13 (14.0) | 3 (3.4) |

| t(4;14) | 10 (10.8) | 12 (13.5) |

| t(14;16) | 6 (6.5) | 7 (7.9) |

| t(14;20) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) |

| gain/amp(1q21) | 16 (17.2) | 22 (24.7) |

| Unknown | 9 (9.7) | 6 (6.7) |

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ISS, International Staging System; ITT, intent to treat.

Patients reporting multiple races are included under “other.”

High risk is defined as positive for any of del(17p), t(14;16), or t(4;14).

Revised high-risk cytogenetics is defined as ≥1 abnormality from del(17p), t(4;14), t(14;16), t(14;20), and gain/amp(1q21).

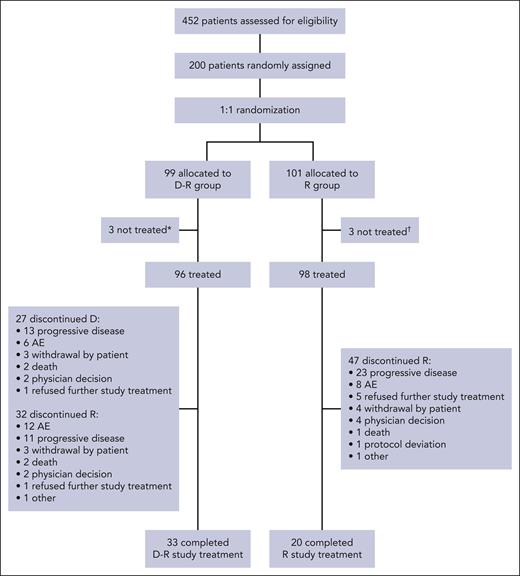

Treatment disposition is summarized in Figure 1. At the time of this analysis, among patients who received treatment (D-R, n = 96; R, n = 98), 33.3% (n = 32) in the D-R group and 48.0% (n = 47) in the R group had discontinued ≥1 component of study treatment. Seven patients in the D-R group and 15 patients in the R group discontinued the study (excluding discontinuations due to death), primarily because of patient withdrawal (D-R, 4.0% [n = 4]; R, 10.9% [n = 11]) and physician decision (D-R, 1.0% [n = 1]; R, 2.0% [n = 2]). Additional information on subsequent therapy is provided in the supplemental Results. At the time of primary analysis (after all patients completed at least 12 months of maintenance, had disease progression, died, or discontinued/withdrew), the median follow-up duration was 32.3 months (D-R, 33.2 months; R, 30.3 months) (supplemental Table 1 includes additional data on study treatment duration).

CONSORT diagram for AURIGA. Summary of treatment disposition in AURIGA. ∗Three patients were randomly assigned but not treated because of physician decision, too intense study schedule, and protocol deviation (n = 1 each). †Three patients were randomly assigned but not treated because of study tests being too hard, patient not wanting to be on the R-only treatment arm, and patient withdrawal of consent (n = 1 each).

CONSORT diagram for AURIGA. Summary of treatment disposition in AURIGA. ∗Three patients were randomly assigned but not treated because of physician decision, too intense study schedule, and protocol deviation (n = 1 each). †Three patients were randomly assigned but not treated because of study tests being too hard, patient not wanting to be on the R-only treatment arm, and patient withdrawal of consent (n = 1 each).

The median (range) duration of study treatment was 30.7 (0.7-37.5) months in the D-R group and 20.6 (0-37.7) months in the R group (supplemental Table 1). Patients received a median (range) of 33.0 (1-36) cycles in the D-R group and 21.5 (1-36) cycles in the R group, and 88.5% (85/96) of D-R patients and 78.6% (77/98) of R patients completed ≥12 maintenance cycles. The median (range) relative dose intensity for R was similar across both groups (D-R, 86.7% [29.7-137.3]; R, 87.3% [37.7-145.5]) and was 100% (75.0-100.0) for daratumumab in the D-R group (supplemental Table 1). R dose adjustments occurred in 71.9% (69/96) of D-R patients and 58.2% (57/98) of R patients, most of which were due to adverse events (AEs). A summary of treatment cycle delays and dose modifications is provided in supplemental Table 2.

Efficacy

The primary end point of MRD-negative (10–5) conversion rate from baseline to 12 months of maintenance treatment was achieved in 50 patients (50.5%) in the D-R group and 19 patients (18.8%) in the R group (OR, 4.51; 95% CI, 2.37-8.57; P < .0001) (Figure 2), representing a statistically significant difference. Considering only the MRD-evaluable patients (D-R, 88.9% [88/99]; R, 81.2% [82/101]), higher rates of MRD-negative (10–5) conversion by 12 months were also observed for D-R than for R (56.8% [50/88] vs 23.2% [19/82], respectively; OR, 4.40; 95% CI, 2.26-8.58; P < .0001). Among patients who achieved a complete response or better (≥CR) at any time during the study, similar trends favoring the D-R arm were observed (61.3% [46/75] vs 25.8% [16/62], respectively; OR, 4.62; 95% CI, 2.20-9.70; P < .0001). Among randomly assigned patients, the MRD-negative (10–5) ≥CR conversion rate by 12 months of maintenance treatment was also higher for D-R than for R (44.4% [44/99] vs 14.9% [15/101], respectively; OR, 4.61; 95% CI, 2.34-9.09; P < .0001). D-R also demonstrated a consistent benefit in MRD-negative (10–5) conversion rate by 12 months across all clinically relevant subgroups, including patients with high cytogenetic risk at diagnosis (per the standard and revised definition) and older adults (Figure 3).

MRD-negative (10–5) conversion rate from baseline to 12 months of maintenance treatment. ∗Mantel-Haenszel estimate of the common OR for stratified tables is used. The stratification factor is baseline cytogenetic risk per investigator assessment (high vs standard/unknown), as was used for randomization. An OR >1 indicates an advantage for D-R. †P value <.0001, from Fisher exact test. ‡The ITT analysis set was defined as all patients who were randomly assigned to treatment. §Patients who achieved ≥CR at any time during the study per IMWG computerized algorithm. ||The MRD-evaluable analysis set includes all randomly assigned patients who had an MRD assessment at baseline and had ≥1 postbaseline MRD evaluation. ITT, intent to treat.

MRD-negative (10–5) conversion rate from baseline to 12 months of maintenance treatment. ∗Mantel-Haenszel estimate of the common OR for stratified tables is used. The stratification factor is baseline cytogenetic risk per investigator assessment (high vs standard/unknown), as was used for randomization. An OR >1 indicates an advantage for D-R. †P value <.0001, from Fisher exact test. ‡The ITT analysis set was defined as all patients who were randomly assigned to treatment. §Patients who achieved ≥CR at any time during the study per IMWG computerized algorithm. ||The MRD-evaluable analysis set includes all randomly assigned patients who had an MRD assessment at baseline and had ≥1 postbaseline MRD evaluation. ITT, intent to treat.

Subgroup analysis of MRD-negative (10–5) conversion rate from baseline to 12 months of maintenance treatment. ∗High risk is defined as positive for any of the following abnormalities: del(17p), t(14;16), or t(4;14). †Revised high-risk cytogenetics are defined as ≥1 of the following abnormalities: del(17p), t(4;14), t(14;16), t(14;20), and gain/amp(1q21). ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ISS, International Staging System.

Subgroup analysis of MRD-negative (10–5) conversion rate from baseline to 12 months of maintenance treatment. ∗High risk is defined as positive for any of the following abnormalities: del(17p), t(14;16), or t(4;14). †Revised high-risk cytogenetics are defined as ≥1 of the following abnormalities: del(17p), t(4;14), t(14;16), t(14;20), and gain/amp(1q21). ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ISS, International Staging System.

At a median follow-up of 32.3 months, the overall MRD-negative (10–5) conversion rate was greater for D-R than for R (60.6% [60/99] vs 27.7% [28/101], respectively; OR, 4.12; 95% CI, 2.26-7.52; P < .0001). The rate of sustained MRD negativity lasting ≥6 months for D-R was ∼2.5 times that of R (35.4% [35/99] vs 13.9% [14/101], respectively; OR, 3.40; 95% CI, 1.69-6.83; P = .0005), and D-R had a higher rate of sustained MRD negativity lasting ≥12 months compared with R (17.2% [17/99] vs 5.0% [5/101]; OR, 4.08; 95% CI, 1.43-11.62; P = .0065) (supplemental Table 3). MRD analyses at the 10−6 threshold showed a similar trend, with higher rates of MRD-negative conversion by 12 months for D-R than for R (23.2% [23/99] vs 5.0% [5/101], respectively; OR, 5.97; 95% CI, 2.15-16.58; P = .0002), and higher rates of overall MRD-negative conversion at the time of follow-up for D-R than for R (36.4% [36/99] vs 12.9% [13/101]; OR, 3.91; 95% CI, 1.91-7.99; P = .0001).

According to IMWG 2016 criteria, best overall confirmed response favored D-R over R, with a greater proportion of patients in the D-R group achieving a best overall confirmed response of ≥CR compared with the R group (75.8% [75/99] vs 61.4% [62/101], respectively; OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.08-3.69; P = .0255). Among patients who entered the study with a baseline response of VGPR (D-R, n = 71; R, n = 71), a greater number of patients in the D-R group had their response improve to ≥CR (n = 21 reached CR; n = 26 reached stringent CR) compared with the R group (n = 14 reached CR; n = 18 reached stringent CR) (supplemental Table 4).

At a median follow-up of 32.3 months, 19 PFS events (19.2%) occurred in the D-R group, as opposed to 26 events (25.7%) in the R group. PFS favored D-R over R (hazard ratio [HR], 0.53; 95% CI, 0.29-0.97), with a 47% risk reduction in disease progression or death; however, the nominal P value of .0361 did not cross the stopping boundary of .015 for this PFS interim analysis. The estimated 30-month PFS rate was 82.7% (95% CI, 72.8-89.3) for D-R and 66.4% (95% CI, 54.0-76.2) for R (Figure 4A). PFS also favored D-R over R across most clinically relevant subgroups, including those with standard or high cytogenetic risk per both the standard and revised definitions, as well as older patients (supplemental Figure 1). As shown in Figure 4B, a PFS benefit was observed among patients who achieved MRD negativity conversion relative to those who remained MRD-positive, regardless of treatment. Estimated 30-month PFS rates were higher for those who achieved MRD-negative conversion by 12 months (D-R, 95.2% [95% CI, 81.9-98.8]; R, 94.1% [95% CI, 65.0-99.1]) compared with those who remained MRD-positive (D-R, 69.0% [95% CI, 52.2-80.9]; R, 59.3% [95% CI, 45.0-71.0]). Five events (5.1%) of death occurred in the D-R group, as opposed to 9 (8.9%) in the R group, trending favorably for the D-R arm (HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.17-1.50) (supplemental Figure 2).

PFS analysis. PFS analysis in the ITT population∗ overall (A) and by MRD-negative (10–5) conversion status by 12 months (B). † Estimated 30-month PFS rates are shown. ∗At a median follow-up of 32.3 months, median PFS was 37.9 months in the D-R group and was not reached in the R group. †MRD-negative by 12 months refers to patients who were MRD-positive at baseline and achieved MRD-negative status (at a threshold of 10–5) by bone marrow aspirate from randomization to 12 months (+2-month window), but before progressive disease and subsequent antimyeloma therapy. Otherwise, patients were considered MRD-positive. ‡Per study protocol, disease assessments stopped at the end of study treatment (cycle 36), after which patients were only followed for survival. At the time of this analysis, the number of patients who reached the end of study treatment was low, thus resulting in a low number of patients at risk. Two D-R events occurred at the tail end of study assessments: 1 reported at 1134 days (37.26 months) and 1 at 1153 days (37.88 months). Because of these events, there was a sudden and steep drop in the Kaplan-Meier curve for D-R. ITT, intent to treat.

PFS analysis. PFS analysis in the ITT population∗ overall (A) and by MRD-negative (10–5) conversion status by 12 months (B). † Estimated 30-month PFS rates are shown. ∗At a median follow-up of 32.3 months, median PFS was 37.9 months in the D-R group and was not reached in the R group. †MRD-negative by 12 months refers to patients who were MRD-positive at baseline and achieved MRD-negative status (at a threshold of 10–5) by bone marrow aspirate from randomization to 12 months (+2-month window), but before progressive disease and subsequent antimyeloma therapy. Otherwise, patients were considered MRD-positive. ‡Per study protocol, disease assessments stopped at the end of study treatment (cycle 36), after which patients were only followed for survival. At the time of this analysis, the number of patients who reached the end of study treatment was low, thus resulting in a low number of patients at risk. Two D-R events occurred at the tail end of study assessments: 1 reported at 1134 days (37.26 months) and 1 at 1153 days (37.88 months). Because of these events, there was a sudden and steep drop in the Kaplan-Meier curve for D-R. ITT, intent to treat.

Safety

A total of 194 patients (D-R, n = 96; R, n = 98) received ≥1 dose of study treatment and comprised the safety analysis set. Treatment-related AEs of any grade were reported in 99.0% of patients in both treatment groups. Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 74.0% of patients in the D-R group and 67.3% of patients in the R group. The most common AEs of any grade (occurring in ≥20% of patients in either group) and grade 3/4 treatment-emergent AEs (occurring in ≥5% in either group) are reported in Table 2.

Most common AEs reported in the safety population

| AE, n (%) . | D-R (n = 96) . | R (n = 98) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade . | Grade 3/4 . | Any grade . | Grade 3/4 . | |

| Hematologic | ||||

| Neutropenia | 62 (64.6) | 45 (46.9) | 60 (61.2) | 41 (41.8) |

| Leukopenia | 25 (26.0) | 9 (9.4) | 29 (29.6) | 6 (6.1) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 23 (24.0) | 3 (3.1) | 28 (28.6) | 2 (2.0) |

| Lymphopenia | 23 (24.0) | 10 (10.4) | 13 (13.3) | 5 (5.1) |

| Anemia | 22 (22.9) | 4 (4.2) | 17 (17.3) | 3 (3.1) |

| Nonhematologic | ||||

| Diarrhea | 59 (61.5) | 3 (3.1) | 54 (55.1) | 5 (5.1) |

| Fatigue | 44 (45.8) | 2 (2.1) | 46 (46.9) | 3 (3.1) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 40 (41.7) | 0 | 26 (26.5) | 0 |

| Cough | 37 (38.5) | 0 | 36 (36.7) | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 33 (34.4) | 7 (7.3) | 36 (36.7) | 6 (6.1) |

| Arthralgia | 32 (33.3) | 1 (1.0) | 36 (36.7) | 1 (1.0) |

| Back pain | 31 (32.3) | 0 | 20 (20.4) | 1 (1.0) |

| COVID-19 | 28 (29.2) | 1 (1.0) | 29 (29.6) | 3 (3.1) |

| Nausea | 26 (27.1) | 0 | 26 (26.5) | 0 |

| Nasal congestion | 25 (26.0) | 0 | 19 (19.4) | 0 |

| Headache | 24 (25.0) | 1 (1.0) | 17 (17.3) | 0 |

| Constipation | 22 (22.9) | 0 | 26 (26.5) | 0 |

| Muscle spasms | 22 (22.9) | 0 | 21 (21.4) | 0 |

| Pain in extremity | 22 (22.9) | 1 (1.0) | 17 (17.3) | 0 |

| Maculopapular rash | 21 (21.9) | 1 (1.0) | 17 (17.3) | 2 (2.0) |

| Hypertension | 14 (14.6) | 7 (7.3) | 10 (10.2) | 4 (4.1) |

| Pneumonia | 10 (10.4) | 5 (5.2) | 14 (14.3) | 4 (4.1) |

| Infusion-related reactions | 13 (13.5) | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| AE, n (%) . | D-R (n = 96) . | R (n = 98) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade . | Grade 3/4 . | Any grade . | Grade 3/4 . | |

| Hematologic | ||||

| Neutropenia | 62 (64.6) | 45 (46.9) | 60 (61.2) | 41 (41.8) |

| Leukopenia | 25 (26.0) | 9 (9.4) | 29 (29.6) | 6 (6.1) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 23 (24.0) | 3 (3.1) | 28 (28.6) | 2 (2.0) |

| Lymphopenia | 23 (24.0) | 10 (10.4) | 13 (13.3) | 5 (5.1) |

| Anemia | 22 (22.9) | 4 (4.2) | 17 (17.3) | 3 (3.1) |

| Nonhematologic | ||||

| Diarrhea | 59 (61.5) | 3 (3.1) | 54 (55.1) | 5 (5.1) |

| Fatigue | 44 (45.8) | 2 (2.1) | 46 (46.9) | 3 (3.1) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 40 (41.7) | 0 | 26 (26.5) | 0 |

| Cough | 37 (38.5) | 0 | 36 (36.7) | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 33 (34.4) | 7 (7.3) | 36 (36.7) | 6 (6.1) |

| Arthralgia | 32 (33.3) | 1 (1.0) | 36 (36.7) | 1 (1.0) |

| Back pain | 31 (32.3) | 0 | 20 (20.4) | 1 (1.0) |

| COVID-19 | 28 (29.2) | 1 (1.0) | 29 (29.6) | 3 (3.1) |

| Nausea | 26 (27.1) | 0 | 26 (26.5) | 0 |

| Nasal congestion | 25 (26.0) | 0 | 19 (19.4) | 0 |

| Headache | 24 (25.0) | 1 (1.0) | 17 (17.3) | 0 |

| Constipation | 22 (22.9) | 0 | 26 (26.5) | 0 |

| Muscle spasms | 22 (22.9) | 0 | 21 (21.4) | 0 |

| Pain in extremity | 22 (22.9) | 1 (1.0) | 17 (17.3) | 0 |

| Maculopapular rash | 21 (21.9) | 1 (1.0) | 17 (17.3) | 2 (2.0) |

| Hypertension | 14 (14.6) | 7 (7.3) | 10 (10.2) | 4 (4.1) |

| Pneumonia | 10 (10.4) | 5 (5.2) | 14 (14.3) | 4 (4.1) |

| Infusion-related reactions | 13 (13.5) | 0 | N/A | N/A |

AEs of any grade that occurred in ≥20% of patients and grade 3/4 AEs that occurred in ≥5% of patients in either treatment group.

N/A, not applicable.

Serious AEs were reported in 30.2% and 22.4% of D-R and R patients, respectively; the most frequent across both groups was pneumonia (4.2% and 4.1%, respectively). The proportion of patients with AEs leading to treatment discontinuation of any treatment component was 14.6% in the D-R group and 8.2% in the R group, most commonly due to myelodysplastic syndrome (D-R, 2.1%; R, 1.0%) for D-R and peripheral sensory neuropathy (0; 2.0%) for R. AEs with an outcome of death were reported in 2 patients within the D-R group (COVID-19 pneumonia and Legionella pneumonia, n = 1 each) and 1 patient in the R group (COVID-19 pneumonia).

Cytopenias of any grade were more common for D-R than for R (75.0% vs 69.4%), including grade 3/4 cytopenias (54.2% vs 46.9%). Neutropenia accounted for most grade 3/4 cytopenias reported in both groups (D-R, 46.9%; R, 41.8%). The overall incidence of grade 3/4 infections in the 2 treatment groups was 18.8% and 13.3% for D-R and R, respectively, with the most common being pneumonia (5.2% vs 4.1%). Grade 3/4 COVID-19 occurred in 1.0% of D-R patients vs 3.1% of R patients, with serious COVID-19 infections reported in 2.1% of D-R patients and 3.1% of R patients. In the D-R group, 13.5% of patients had ≥1 infusion-related reaction, none of which were grade ≥3 or serious (Table 2). Most infusion-related reactions occurred with the first injection (11.5%), with incidences decreasing for the second injection (3.1%) and subsequent injections (4.2%).

A complete summary of secondary primary malignancies (SPMs) is provided in supplemental Table 5. A total of 7.3% of patients in the D-R group and 4.1% in the R group had SPMs. Hematologic SPMs were observed in 2.1% of patients in the D-R group and 3.1% of patients in the R group. Noncutaneous and cutaneous SPMs were observed in 3.1% and 2.1% of patients in the D-R group, respectively, and 1.0% and 0% in the R group.

Discussion

In the randomized, phase 3 AURIGA study, the addition of daratumumab to R maintenance resulted in a significantly higher MRD-negative conversion rate among transplant-eligible patients with NDMM who had ≥VGPR, were MRD-positive, and were anti-CD38–naïve after ASCT, compared with R maintenance alone. This increase in MRD-negative conversion was clinically meaningful given that D-R maintenance trended toward improved PFS, higher overall MRD-negative conversion rates, and deeper responses compared with R maintenance alone, with no unexpected safety concerns.

Achieving MRD negativity has been associated with improved disease control and prolonged survival2,9 and has been demonstrated to be a surrogate marker for PFS.10 Additionally, a recent meta-analysis of 11 clinical trials reported that a difference of ∼12% in MRD-negative rates was associated with a PFS improvement of ∼12 months.11 In AURIGA, the MRD-negative (10–5) conversion rate by 12 months for D-R maintenance was 2.7 times the rate of R alone (50.5% vs 18.8%, respectively), with improvements also observed at the 10−6 threshold and across all clinically relevant subgroups, including patients with high-risk disease. D-R maintenance also led to higher rates of sustained MRD negativity lasting ≥6 months.

At a median follow-up of 32.3 months, PFS favored D-R maintenance over R maintenance alone, with an observed 47% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death and estimated 30-month PFS rates of 82.7% in the D-R arm and 66.4% in the R arm. At the time of data analysis, the number of patients who reached the end of study treatment in the ongoing AURIGA study was low, resulting in a low number of patients at risk at this time point. However, given that the Kaplan-Meier curve for D-R was consistently above the curve for R before the end of study treatment (cycle 36) and that the HR for PFS favored D-R, the data demonstrate that PFS favored D-R over R. A PFS advantage was also observed for patients who achieved MRD-negative conversion compared with those who remained MRD-positive, regardless of treatment arm. Thus, the higher MRD-negative conversion rate at 12 months in the D-R arm vs the R arm resulted in a PFS benefit in the D-R arm and demonstrated the value of daratumumab in maintenance therapy.

Although this was, to our knowledge, the first randomized trial to directly compare daratumumab-based maintenance therapy with SoC maintenance, findings are consistent with those observed in the CASSIOPEIA study. In the CASSIOPEIA study of transplant-eligible patients with NDMM, patients received bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (VTd) with or without daratumumab as induction/consolidation in part 1. In part 2, patients with a partial response or better were rerandomized to receive daratumumab monotherapy every 8 weeks as maintenance or observation.12,13 After a median follow-up of 70.6 months, daratumumab maintenance significantly reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 51% compared with observation. The longest PFS was observed in patients who received daratumumab plus VTd (D-VTd) induction/consolidation followed by the daratumumab maintenance arm, with a substantial difference compared with patients who received D-VTd followed by observation (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.58-1.00; P = .0480).14 This PFS benefit for daratumumab maintenance in patients who received D-VTd was not apparent at the primary study analysis, but manifested itself with longer follow-up. Thus, the updated CASSIOPEIA data demonstrate the benefit of daratumumab maintenance, both in patients who received VTd and those who received D-VTd induction/consolidation.

Other studies have included daratumumab as part of the maintenance regimen in transplant-eligible patients with NDMM. Specifically, the phase 2 GRIFFIN study and phase 3 PERSEUS study evaluated the addition of daratumumab to bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (D-VRd) induction/consolidation and R maintenance (D-R).15,16 In both studies, D-VRd induction/consolidation followed by D-R maintenance led to deep and durable responses that improved with maintenance therapy, with both studies reporting a reduced risk of disease progression or death by 55% to 58%.

One critical remaining question is whether the benefit of D-R maintenance, as observed in AURIGA, is applicable to patients who receive D-VRd or another daratumumab-containing regimen as induction therapy. As discussed previously, the CASSIOPEIA study demonstrated that daratumumab monotherapy improved PFS in patients who received D-VTd, but patients in the control arm did not receive any maintenance therapy. Neither the GRIFFIN nor the PERSEUS studies were designed to isolate the contribution of maintenance therapy to primary and secondary end points, as no rerandomization was conducted before maintenance initiation. However, a post hoc analysis of the phase 3 PERSEUS study indicated that D-R maintenance can confer clinical benefit in patients who received D-VRd induction/consolidation. Specifically, 60.2% of patients who were MRD-positive following D-VRd induction/consolidation and ASCT successfully converted to MRD negativity (10–5) with D-R maintenance, whereas only 40.5% of patients who were MRD-positive following VRd induction/consolidation and ASCT achieved MRD negativity (10–5) conversion with R maintenance alone.17 This difference was even more pronounced at a threshold of 10–6, with 56.7% of D-VRd patients converting to MRD negativity with D-R maintenance vs 25.2% of VRd patients converting to MRD negativity with R maintenance.17 However, in the absence of rerandomization, this analysis cannot eliminate the potential impact of daratumumab in induction and consolidation on the MRD-conversion rates during maintenance. Further investigations are needed to conclusively isolate the benefit of D-R maintenance vs R alone following daratumumab-based induction regimens. The ongoing DRAMMATIC SWOG1803 study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier, NCT04071457) will provide more definitive information on the clinical benefit of D-R vs R maintenance and whether maintenance therapy can be discontinued after attainment of sustained MRD negativity. The GMMG HD7 study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT03617731) will also provide information on anti-CD38 therapies in this setting.

The addition of daratumumab to R maintenance did not result in any unexpected or new safety concerns, with a safety profile consistent with that previously known for daratumumab.12,18,19 Rates of grade 3/4 AEs, serious AEs, and SPMs were slightly greater in the D-R arm than in the R arm alone, as were rates of infections or cytopenias. These higher rates should be interpreted in the context of the longer treatment duration in the D-R arm (30.7 months) compared with the R arm (20.6 months), leading to a longer AE reporting interval. Similarly, the longer follow-up time (33.2 months for D-R vs 30.3 months for R) led to a longer reporting interval for SPMs. The rate of treatment discontinuation of any component of study therapy due to AEs was higher with D-R than R maintenance alone (D-R group, 14.6%; R group, 8.2%).

In summary, among transplant-eligible patients with NDMM who had ≥VGPR, were MRD-positive after ASCT, and were anti-CD38–naïve, the addition of daratumumab to SoC R maintenance resulted in improved rates of MRD-negative conversion, deeper responses, and improved PFS rates. No new safety concerns were observed. These results support the addition of daratumumab not only to induction/consolidation, but also to SoC R maintenance for these patients. Future studies should continue to assess the implementation of daratumumab-based maintenance in other patient populations and determine the optimal point of treatment initiation and cessation.

It is worth mentioning that the AURIGA study eligibility requirement for patients to be anti-CD38–naïve limited the recruitment pool. This was partially due to the D-VRd regimen gaining popularity and increased use in the myeloma community for transplant-eligible patients with NDMM, even before the publication of the long-term results of the randomized GRIFFIN and PERSEUS studies.15,16 An additional limitation was that nearly 10% of patients in each treatment arm had “unknown” cytogenetic risk. Furthermore, there was an imbalance in patients with high cytogenetic risk between the D-R and R maintenance arms at diagnosis (23.9% and 16.9%, respectively), per the standard definition, due to erroneous high-risk assessments used for stratification. Despite these imbalances in favor of the control arm, the current study still met its primary end point, with higher MRD-negative conversion rates observed for the D-R arm, making the AURIGA data more impactful. Of note, many patients have not reached both the 24- and 36-month MRD assessments. Per the study protocol, MRD was assessed after certain numbers of treatment cycles rather than after fixed intervals, and each 28-day cycle was slightly shorter than 1 month. Thus, most participants who achieved initial MRD negativity at 12 months were not assessable for ≥6 months or ≥12 months of sustained MRD negativity until they reached the 24-cycle or 36-cycle MRD assessment, respectively. Longer follow-up is needed to determine whether higher sustained MRD-negativity rates are observed at subsequent data cutoffs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who volunteered to participate in this trial, their families, and the staff members at the trial sites who cared for them. In addition, the authors thank all the study personnel at the participating sites. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Holly Clarke and Charlotte D. Majerczyk, of Lumanity Communications Inc., and were funded by Janssen Biotech, Inc.

This study was sponsored by Janssen Biotech, Inc.

Authorship

Contribution: A.B. participated in investigation, patient enrollment, analysis of data, and writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript; L.F. participated in investigation, acquisition of data, and writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript; L.D.A. participated in investigation, data collection, writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript, supervision of the investigation, and data collection; C.P.C. participated in investigation, patient enrollment, and writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript; E.P. participated in patient enrollment and writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript; A.J.C. and C.C. participated in writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript, and investigation; S.L. participated in patient enrollment, data collection, and writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript; D.W.S. participated in conceptualization, investigation, writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript, and supervision; K.H.S. participated in patient enrollment, the study steering committee, and reviewing and editing of the manuscript; R.S. participated in investigation, resources, validation, and writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript; N.S. participated in patient enrollment, the steering committee, and writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript; A. Chung and M.K. participated in writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript; H.P. participated in statistical analysis and reviewing and editing of the manuscript; S.P., V.K. and A. Cortoos participated in data curation, supervision, project administration, and writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript; R.C. participated in supervision and writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript; T.S.L. participated in conceptualization, study design, supervision, and writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript; and P.V. participated in conceptualization, investigation, resourcing, and writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.B. received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), GSK, BeiGene, Roche, and Janssen. L.F. served on advisory boards and as a site principal investigator for BMS and Janssen Biotech Inc. L.D.A. served as a consultant and on advisory boards for Janssen, Celgene, BMS, Amgen, GSK, AbbVie, BeiGene, Cellectar, Sanofi, and Prothena and served on the data safety monitoring board for Prothena. C.P.C. received honoraria from Janssen and Sanofi Genzyme. A.J.C. served as a consultant or in an advisory role for Sebia, Janssen, BMS, Sanofi, HopeAI, Adaptive Biotechnologies, and AbbVie and received research funding from Janssen, BMS, Juno/Celgene, Sanofi, Regeneron, IGM Biosciences, Nektar, Harpoon, and Caelum. C.C. served as a consultant for BMS, Janssen, Pfizer, Karyopharm, and Genentech and received research funding from BMS, Janssen, Takeda, Ionis, Poseida, and Harpoon. S.L. received research funding from Janssen, Allogene (Inst), Bioline (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), BMS (Inst), Regeneron (Inst), Sanofi (Inst), Ionis (Inst), and ImmPACT Bio (Inst) and owns stock or stock options for TORL Biotherapeutics. D.W.S. served as a consultant or in an advisory role for GSK, Janssen, Sanofi, AbbVie, BMS, Pfizer, Arcellx, Bioline, AstraZeneca, and Genentech and received research funding from Pfizer. K.H.S. served on an advisory board for Janssen, Sanofi, and GSK; received research funding from AbbVie and Karyopharm; and received honoraria from Karyopharm, Janssen, Adaptive Biotechnologies, GSK, BMS, Sanofi Genzyme, and Regeneron. R.S. served as a consultant or in an advisory role for Sanofi-Aventis, Janssen Oncology, and Oncopeptides and received research funding from Sanofi. N.S. is a current employee and stockholder of AstraZeneca. A. Chung served as a consultant and on an advisory board for Janssen and received research funding from AbbVie, BMS, Caelum, CARsgen, Cellectis, Janssen, K36 Therapeutics, and Merck. M.K., H.P., S.P., V.K., A. Cortoos, R.C., and T.S.L. are employees of Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) and may hold stock. P.V. served as a consultant for, received honoraria from, and holds a membership on the board of directors or advisory committees for AbbVie, BMS, Karyopharm, Regeneron, and Sanofi. E.P. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ashraf Badros, Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Maryland, 22 S Greene St, Baltimore, MD 21201; email: abadros@umm.edu.

References

Author notes

The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this website, requests for access to the study data can be submitted through the Yale University Open Data Access Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal