Key Points

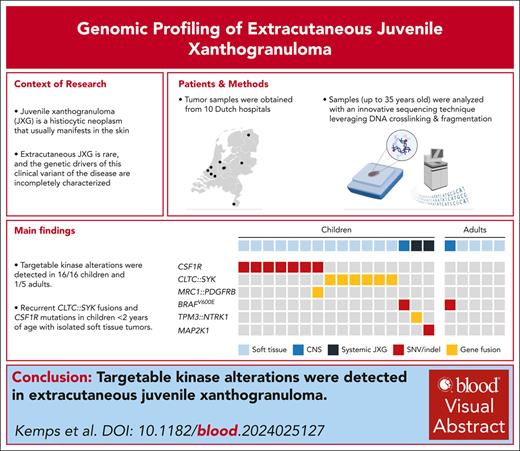

CLTC::SYK fusions and CSF1R mutations are recurrent genetic alterations in JXG of soft tissue.

BRAF, MAP2K1, or NTRK1 alterations may be detected in CNS- or systemic JXG, enabling targeted therapy when necessary.

Visual Abstract

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is a histiocytic neoplasm that usually presents in the skin. Rarely, extracutaneous localizations occur; the genetic drivers of this clinical variant of JXG remain incompletely characterized. We present detailed clinicopathologic and molecular data of 16 children with extracutaneous JXG and 5 adults with xanthogranulomas confined to the central nervous system (CNS) or soft tissue. Tissue samples were obtained through the Dutch Nationwide Pathology Databank and analyzed with an innovative sequencing technique capable of detecting both small genomic variants and gene rearrangements. Targetable kinase alterations were detected in 16 of 16 children and 1 of 5 adults. Alterations included CLTC::SYK fusions in 6 children and CSF1R mutations in 7 others; all below 2 years of age with soft tissue tumors. One child had a CSF1R mutation and MRC1::PDGFRB fusion. Most were treated surgically, although spontaneous regression occurred in 1 of 6 with CLTC::SYK and 2 of 7 with CSF1R mutations, underscoring that treatment is not always necessary. Tumors with CLTC::SYK fusions generally lacked Touton giant cells but exhibited many other histologic features of JXG and concordant methylation profiles. Using multispectral immunofluorescence, phosphorylated–spleen tyrosine kinase expression was localized to CD163+ histiocytes; tumors with CLTC::SYK fusions also demonstrated mTOR activation, cyclin D1 expression, and variable phosphorylated–extracellular signal-regulated kinase expression. BRAFV600E was detected in 1 child and 1 adult with CNS-xanthogranulomas; both responded to BRAF inhibition. Finally, a TPM3::NTRK1 fusion or MAP2K1 deletion was detected in 2 children with systemic JXG who experienced spontaneous disease regression. This study advances the molecular understanding of histiocytic neoplasms and may guide diagnostics and clinical management.

Introduction

Xanthogranuloma (XG) family lesions are a group of histiocytic diseases that usually present in the skin.1 Various subtypes can be distinguished based on the clinical setting and histopathologic features.1 In children, “juvenile XG (JXG)” or “JXG family lesions” are used as umbrella terms for these subtypes, which have overlapping histomorphology and a shared immunophenotype.2,3 The term JXG is used in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of hematolymphoid tumors.4 Most JXG lesions appear during the first years of life,5 and skin lesions often resolve spontaneously within months to years.1 Rarely, extracutaneous localizations of JXG occur, which may pose a diagnostic challenge and can behave more aggressively.2,3,6 Recent studies have identified somatic genetic alterations in many histiocytic diseases,7-12 including JXG. However, the genetic drivers of the rare form of extracutaneous JXG remain incompletely characterized. Here, we demonstrate targetable somatic genetic alterations in extracutaneous JXG, including recurrent CLTC::SYK fusions and CSF1R mutations in children below 2 years of age with large soft tissue tumors.

Methods

Study design

We searched for children diagnosed with extracutaneous JXG between 1971 and 2022 in the Dutch Nationwide Pathology Databank (Palga).13 In addition, we searched for adults with isolated extracutaneous XG family lesions, a disease presentation that does not fit with the clinical phenotype of Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD).14 Notably, the term “juvenile” in JXG only indicates a XG family lesion in a child (aged <18 years at diagnosis); JXG, adult XG, and ECD share similar morphologic patterns and a common immunophenotype.2 First, we retrieved all pseudonymized pathology reports with a pathologist-assigned diagnostic code for a histiocytic disorder.5,15 Relevant cases were then identified based on free-text queries (directed at terminology for organs other than the skin), because no separate diagnostic code for extracutaneous JXG exists.15 Archival tissue slides and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks were requested from pathology laboratories through the “Palga intermediary procedure.”16 In addition, the pathology laboratories referred us to the treating physicians, who provided pseudonymized clinical data and images. Central pathology review was performed by an experienced soft tissue pathologist (P.C.W.H.), and additional immunohistochemical stains were performed when indicated. Inclusion criteria were: (1) XG morphology and immunophenotype, as detailed in the WHO classification of hematolymphoid tumors (chapter JXG),4 with expression of at least 1 of the histiocyte markers CD68 and CD163; (2) the presence of at least 1 extracutaneous disease manifestation, which encompasses subcutaneous/soft tissue lesions (sometimes referred to as “deep” or “giant” JXG lesions17-20); and (3) sufficient leftover tissue for molecular analysis - unless comprehensive molecular analysis had already been performed through routine diagnostics. Excluded were cases diagnosed as ECD based on characteristic clinical and radiologic features14 or as ALK+ histiocytosis, malignant histiocytosis, or mixed histiocytosis based on pathologic findings.4,9,21 Antibody clones and immunohistochemistry protocols are provided in the supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website. This retrospective study was approved by the Palga Scientific Council and Privacy Committee (LZV-2016-183) and the institutional review board of Leiden University Medical Center (B19.074); the requirement for informed consent was waived. In addition, the study was approved by the Biobank and Data Access Committee of the Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology (PMCLAB2024.0512).

Targeted locus capture–based sequencing

Unless cases had been comprehensively analyzed through routine molecular diagnostics, DNA was isolated from microdissected FFPE tissue fragments or from FFPE tissue punches and subjected to targeted locus capture–based next-generation sequencing (TLC-NGS) according to a published protocol.10,22,23 TLC-NGS leverages DNA crosslinking and fragmentation and is therefore particularly suitable for analyzing (old) FFPE samples in which DNA is inherently crosslinked and fragmented.23 Moreover, TLC-NGS enables the detection of both small genomic variants and chromosomal rearrangements. For this study, a custom capture probe panel (Roche) was designed, capturing all exons of 126 genes frequently mutated in histiocytic and other hematologic neoplasms, as well as introns of 55 of 126 genes. A list of targeted genes is provided in the supplemental Methods. NGS reads were aligned to the human GRCh37/hg19 reference genome before the detection of gene fusions and other structural variants using the computational framework proximity ligation–based identification of rearrangements (PLIER).22,23 To detect small genetic variants, sequencing data were subjected to a published somatic variant calling pipeline,24 using variant caller Mutect2.25 Variants were analyzed by a certified clinical molecular biologist in pathology (T.v.W.) using Geneticist Assistant software (SoftGenetics), as described previously.10,26

Multimodal detection and characterization of CLTC::SYK fusions

For polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Sanger sequencing, DNA was isolated from FFPE tissue using the automated Tissue Preparation System (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics).27 Primers spanning the fusion break points were designed with Primer3 software28 and obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies. Primer sequences and detailed PCR and Sanger sequencing methodology are available in the supplemental Methods. In short, PCR was performed on a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System with SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories), with an annealing temperature of 60°C for 40 cycles. The PCR product was purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and subjected to Sanger sequencing on an Applied Biosystems 3730XL system.

For SYK break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), bacterial artificial chromosome clones were obtained from the Wellcome Sanger Institute. One bacterial artificial chromosome clone proximal of SYK (RP11-555F9, chr9: 93146180-93322501, GRCh37/hg19) and 1 distal of SYK (RP11-440G5, chr9: 94132889-94301786, GRCh37/hg19) were used.29 The proximal probe was labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP and the distal probe with biotin-11-dUTP (Roche), as described earlier.30 FISH was then performed on 6-μM thick FFPE tissue sections according to previously described methodology with minor modifications.30,31 Details are available in the supplemental Methods.

Whole transcriptome sequencing was performed in the routine workflow of the Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology.32 Gene fusions were detected with STAR-Fusion software.33

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 3-μm thick FFPE tissue sections using commercially available antibodies for spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK), phosphorylated-SYK (p-SYK), p-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (p-ERK), p-Akt, p-ribosomal protein S6 (p-S6), and cyclin D1. In addition, multispectral immunofluorescence staining of CD163, SYK, and p-SYK was performed; antibody clones and protocols are available in the supplemental Methods.

Genome-wide methylation profiling and copy number analysis

Genome-wide methylation profiling and copy number analysis was performed using the Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0 array (Illumina) in the routine workflow of Heidelberg University Hospital.34 In addition to 15 tissue samples of patients with extracutaneous JXG, we profiled 14 FFPE samples of patients with isolated cutaneous XGs. As control, we profiled 10 FFPE samples of common dermatofibromas and 8 FFPE samples of atypical dermatofibromas.35 Unsupervised hierarchical clustering was performed using the 20 000 most variably methylated 5'-C-phosphate-G-3' (CpG) sites across the data set according to standard deviation, Euclidean distance, and the complete linkage method. Details of data analysis are provided in the supplemental Methods.

Results

Sixteen children with extracutaneous JXG were identified (Table 1), with a median age at diagnosis of 4.5 months (range, 0-2.8 years). Thirteen had isolated soft tissue tumors, 1 had central nervous system (CNS)–JXG, and 2 had systemic JXG affecting ≥2 organ systems. In addition, 5 adults with XGs confined to the CNS or soft tissue were included, with a median age of 47 years (range, 18-58). Patients were diagnosed between 1987 and 2022 at 10 different hospitals across The Netherlands; the median follow-up was 4.3 years (range, 0-25). All 13 children with soft tissue tumors were below 2 years old; their tumors manifested in diverse anatomic locations, including the scalp, trunk, extremities, and trachea. Both children with systemic JXG did not meet diagnostic criteria for pediatric ECD.36

Molecular and clinical features of included patients

| No. . | Genetic alteration(s) . | Detection method . | Age . | Sex . | Disease extent . | Organ(s) . | Disease site(s) . | Description . | Therapy . | Outcome . | Status (follow-up duration) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XG of soft tissue | |||||||||||

| 1 | CSF1R exon 12 deletion | TLC-NGS | 0.1 y (C) | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue and skin | Chest | Large tumor (3 cm) ventral of the clavicle, restricted to the skin and subcutaneous tissue, and with recurrent ulceration | Subtotal resection | Relapse in scar (1.2 × 0.7 cm) with slow spontaneous regression | Alive with minor disease in scar (2.6 y) |

| 2 | CLTC::SYK fusion | TLC-NGS | 0.2 y (C) | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Forearm | Large forearm tumor (7 × 5.5 cm) | Active monitoring | Spontaneous regression of lesion | Alive with NED (12.1 y) |

| 3 | CSF1R exon 12 indel | TLC-NGS | 0.2 y (C) | M | SS multifocal | Soft tissue and skin | Neck and upper leg | Two subcutaneous tumors; 1 in the neck and 1 on the upper leg | Resection neck tumor; active monitoring of the lesion on the leg | Spontaneous regression of leg lesion∗ | Alive with NED (2.4 y) |

| 4 | CSF1R exon 12 indel | TLC-NGS | 0.2 y | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Scalp | Large extra/intracranial tumor of the frontal, temporal and parietal skull | Resection | N/A | Alive with disease (0.1 y) |

| 5 | CSF1R exon 12 indel | TLC-NGS | 0.3 y (C) | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue and skin | Forearm | Subcutaneous forearm tumor (2.8 × 1.6 × 4.2 cm), extending inward between the flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus | Active monitoring | Spontaneous regression of lesion | Alive with NED (11.8 y) |

| 6 | MRC1::PDGFRB fusion and CSF1R deletion of exons 21-22 | TLC-NGS | 0.3 y | F | SS multifocal | Soft tissue | Abdomen | Large tumor involving the greater omentum; small lesions on intestinal walls and in the liver hilum | Subtotal resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (24.9 y) |

| 7 | CSF1R exon 12 indel | TLC-NGS | 0.4 y | M | SS multifocal | Soft tissue/muscle | Scalp and back | Subcutaneous mass scalp; intramuscular tumor below the scapula | Subtotal resections scalp lesion (3× within 4 months); resection tumor below the scapula | Relapse of scalp lesion in scar; complete remission after re-resections | Alive with NED (9.8 y) |

| 8 | CLTC::SYK fusion | TLC-NGS | 0.4 y | F | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Scalp | Parietal tumor | Subtotal resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (25.3 y) |

| 9 | CLTC::SYK fusion | TLC-NGS and WTS | 0.4 y | F | SS unifocal | Soft tissue/muscle | Inguinal region | Intramuscular tumor in the vastus medialis of the quadriceps muscle group | Resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (0.03 y) |

| 10 | CLTC::SYK fusion | TLC-NGS and WTS | 0.6 y | F | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Thoracic wall | Parasternal tumor below the pectoralis major with extension between the second and third rib to the parietal pleura (2.7 × 2 × 3.2 cm) | Subtotal resection† | Complete remission | Alive with NED (13.5 y) |

| 11 | CLTC::SYK fusion | TLC-NGS | 0.8 y | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue/muscle | Abdominal wall | Tumor on the fascia of the abdominal external oblique muscle | Resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (0.6 y) |

| 12 | CLTC::SYK fusion | TLC-NGS and WTS | 1.1 y | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Upper leg | Subcutaneous nodule in the lateral upper leg positioned just above the fascia of the underlying muscle | Resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (0.03 y) |

| 13 | CSF1R exons 9-10 missense mutations | WES (clinical) | 1.2 y | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Trachea | Midendotracheal pedunculated tumor, originating from the anterior wall | Resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (2.2 y) |

| 14 | TBL1XR1::BOD1L1 fusion | TLC-NGS and WTS | 18.9 y | F | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Nasopharynx | Large submucosal tumor of the nasopharynx (3.7 × 2.5 cm) with invasion of prevertebral muscles | 1. Corticosteroid injection 2. Debulking surgery 3. Resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (11.8 y) |

| 15 | None detected | TLC-NGS | 36.6 y | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Paranasal sinus | Submucosal tumor left paranasal sinus | Resection | N/A | N/A |

| 16 | None detected | TLC-NGS | 47 y | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Pubic region | Large tumor (5.5 cm) in the proximal upper leg, adjacent to the pectineal line of the pubis | Resection | N/A | N/A |

| 17 | None detected | TLC-NGS | 58.2 y | F | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Scalp | Parietal subcutaneous soft tissue tumor with bone destruction | Resection‡ | Complete remission | Alive with NED (5.2 y) |

| No. . | Genetic alteration(s) . | Detection method . | Age . | Sex . | Disease extent . | Organ(s) . | Disease site(s) . | Description . | Therapy . | Outcome . | Status (follow-up duration) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XG of soft tissue | |||||||||||

| 1 | CSF1R exon 12 deletion | TLC-NGS | 0.1 y (C) | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue and skin | Chest | Large tumor (3 cm) ventral of the clavicle, restricted to the skin and subcutaneous tissue, and with recurrent ulceration | Subtotal resection | Relapse in scar (1.2 × 0.7 cm) with slow spontaneous regression | Alive with minor disease in scar (2.6 y) |

| 2 | CLTC::SYK fusion | TLC-NGS | 0.2 y (C) | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Forearm | Large forearm tumor (7 × 5.5 cm) | Active monitoring | Spontaneous regression of lesion | Alive with NED (12.1 y) |

| 3 | CSF1R exon 12 indel | TLC-NGS | 0.2 y (C) | M | SS multifocal | Soft tissue and skin | Neck and upper leg | Two subcutaneous tumors; 1 in the neck and 1 on the upper leg | Resection neck tumor; active monitoring of the lesion on the leg | Spontaneous regression of leg lesion∗ | Alive with NED (2.4 y) |

| 4 | CSF1R exon 12 indel | TLC-NGS | 0.2 y | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Scalp | Large extra/intracranial tumor of the frontal, temporal and parietal skull | Resection | N/A | Alive with disease (0.1 y) |

| 5 | CSF1R exon 12 indel | TLC-NGS | 0.3 y (C) | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue and skin | Forearm | Subcutaneous forearm tumor (2.8 × 1.6 × 4.2 cm), extending inward between the flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus | Active monitoring | Spontaneous regression of lesion | Alive with NED (11.8 y) |

| 6 | MRC1::PDGFRB fusion and CSF1R deletion of exons 21-22 | TLC-NGS | 0.3 y | F | SS multifocal | Soft tissue | Abdomen | Large tumor involving the greater omentum; small lesions on intestinal walls and in the liver hilum | Subtotal resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (24.9 y) |

| 7 | CSF1R exon 12 indel | TLC-NGS | 0.4 y | M | SS multifocal | Soft tissue/muscle | Scalp and back | Subcutaneous mass scalp; intramuscular tumor below the scapula | Subtotal resections scalp lesion (3× within 4 months); resection tumor below the scapula | Relapse of scalp lesion in scar; complete remission after re-resections | Alive with NED (9.8 y) |

| 8 | CLTC::SYK fusion | TLC-NGS | 0.4 y | F | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Scalp | Parietal tumor | Subtotal resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (25.3 y) |

| 9 | CLTC::SYK fusion | TLC-NGS and WTS | 0.4 y | F | SS unifocal | Soft tissue/muscle | Inguinal region | Intramuscular tumor in the vastus medialis of the quadriceps muscle group | Resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (0.03 y) |

| 10 | CLTC::SYK fusion | TLC-NGS and WTS | 0.6 y | F | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Thoracic wall | Parasternal tumor below the pectoralis major with extension between the second and third rib to the parietal pleura (2.7 × 2 × 3.2 cm) | Subtotal resection† | Complete remission | Alive with NED (13.5 y) |

| 11 | CLTC::SYK fusion | TLC-NGS | 0.8 y | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue/muscle | Abdominal wall | Tumor on the fascia of the abdominal external oblique muscle | Resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (0.6 y) |

| 12 | CLTC::SYK fusion | TLC-NGS and WTS | 1.1 y | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Upper leg | Subcutaneous nodule in the lateral upper leg positioned just above the fascia of the underlying muscle | Resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (0.03 y) |

| 13 | CSF1R exons 9-10 missense mutations | WES (clinical) | 1.2 y | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Trachea | Midendotracheal pedunculated tumor, originating from the anterior wall | Resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (2.2 y) |

| 14 | TBL1XR1::BOD1L1 fusion | TLC-NGS and WTS | 18.9 y | F | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Nasopharynx | Large submucosal tumor of the nasopharynx (3.7 × 2.5 cm) with invasion of prevertebral muscles | 1. Corticosteroid injection 2. Debulking surgery 3. Resection | Complete remission | Alive with NED (11.8 y) |

| 15 | None detected | TLC-NGS | 36.6 y | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Paranasal sinus | Submucosal tumor left paranasal sinus | Resection | N/A | N/A |

| 16 | None detected | TLC-NGS | 47 y | M | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Pubic region | Large tumor (5.5 cm) in the proximal upper leg, adjacent to the pectineal line of the pubis | Resection | N/A | N/A |

| 17 | None detected | TLC-NGS | 58.2 y | F | SS unifocal | Soft tissue | Scalp | Parietal subcutaneous soft tissue tumor with bone destruction | Resection‡ | Complete remission | Alive with NED (5.2 y) |

| No. . | Genetic alteration(s) . | Detection method . | Age . | Sex . | Disease extent . | Organ(s) . | Description . | Therapy . | Outcome . | Status (follow-up duration) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated CNS-XG | ||||||||||

| 18 | BRAF p.V600E | NGS (clinical) | 0.5 y | F | SS unifocal | CNS | Intramedullary spinal cord tumor at level Th9-L1 | Dabrafenib (initially + trametinib) | Complete remission while on targeted therapy | Alive with NED (4.3 y) |

| 19 | BRAF p.V600E | PCR (clinical) and TLC-NGS | 50.2 y | F | SS multifocal | CNS | Multifocal brain and spinal cord tumors | 1. Subtotal resection; 2. Steroids (MPS); 3. 2-CDA (2 courses), followed by MPS; 4. Vemurafenib (0.5 y; lost access); 5. PEG-IFN-α; 6. Steroids (MPS); 7. Vemurafenib | Progressive disease with conventional therapy; partial remission with vemurafenib | Alive with disease (9.6 y) |

| Systemic JXG | ||||||||||

| 20 | TPM3::NTRK1 fusion and MAP3K1 exon 20 deletion | TLC-NGS | 0.02 y (C) | F | MS | Hematopoietic system, liver, skin, spleen | Anemia, trombocytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly (with calcifications in the spleen, which was 10 cm in length); an unifocal skin nodule on the right shoulder | Supportive care (including transfusions) | Spontaneous regression of the skin lesion, cytopenias, and hepatosplenomegaly | Alive with NED (0.6 y) |

| 21 | MAP2K1 exon 2 deletion | TLC-NGS | 2.8 y | F | MS | Pituitary, lungs, lymph nodes, skin | Thickened pituitary; bilateral lung consolidations; bilateral enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes (maximum size of lymph node collection: 3.8 cm); papular skin lesions on the trunk, legs, arms, and face | Active monitoring | Slow spontaneous regression of skin lesions, lung abnormalities and enlarged lymph nodes; persistent thickened pituitary stalk | Alive in clinical remission (15.7 y) |

| No. . | Genetic alteration(s) . | Detection method . | Age . | Sex . | Disease extent . | Organ(s) . | Description . | Therapy . | Outcome . | Status (follow-up duration) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated CNS-XG | ||||||||||

| 18 | BRAF p.V600E | NGS (clinical) | 0.5 y | F | SS unifocal | CNS | Intramedullary spinal cord tumor at level Th9-L1 | Dabrafenib (initially + trametinib) | Complete remission while on targeted therapy | Alive with NED (4.3 y) |

| 19 | BRAF p.V600E | PCR (clinical) and TLC-NGS | 50.2 y | F | SS multifocal | CNS | Multifocal brain and spinal cord tumors | 1. Subtotal resection; 2. Steroids (MPS); 3. 2-CDA (2 courses), followed by MPS; 4. Vemurafenib (0.5 y; lost access); 5. PEG-IFN-α; 6. Steroids (MPS); 7. Vemurafenib | Progressive disease with conventional therapy; partial remission with vemurafenib | Alive with disease (9.6 y) |

| Systemic JXG | ||||||||||

| 20 | TPM3::NTRK1 fusion and MAP3K1 exon 20 deletion | TLC-NGS | 0.02 y (C) | F | MS | Hematopoietic system, liver, skin, spleen | Anemia, trombocytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly (with calcifications in the spleen, which was 10 cm in length); an unifocal skin nodule on the right shoulder | Supportive care (including transfusions) | Spontaneous regression of the skin lesion, cytopenias, and hepatosplenomegaly | Alive with NED (0.6 y) |

| 21 | MAP2K1 exon 2 deletion | TLC-NGS | 2.8 y | F | MS | Pituitary, lungs, lymph nodes, skin | Thickened pituitary; bilateral lung consolidations; bilateral enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes (maximum size of lymph node collection: 3.8 cm); papular skin lesions on the trunk, legs, arms, and face | Active monitoring | Slow spontaneous regression of skin lesions, lung abnormalities and enlarged lymph nodes; persistent thickened pituitary stalk | Alive in clinical remission (15.7 y) |

2-CDA, cladribine; C, congenital; F, female; indel, insertion-deletion; L, lumbar; M, male; MPS, methylprednisolone; MS, multisystem; N/A, not available; NED, no evidence of disease; PEG-IFN-α, pegylated interferon alfa; SS, single system; Th, thoracic; TLC, targeted locus capture; WES, whole exome sequencing; WTS, whole transcriptome sequencing.

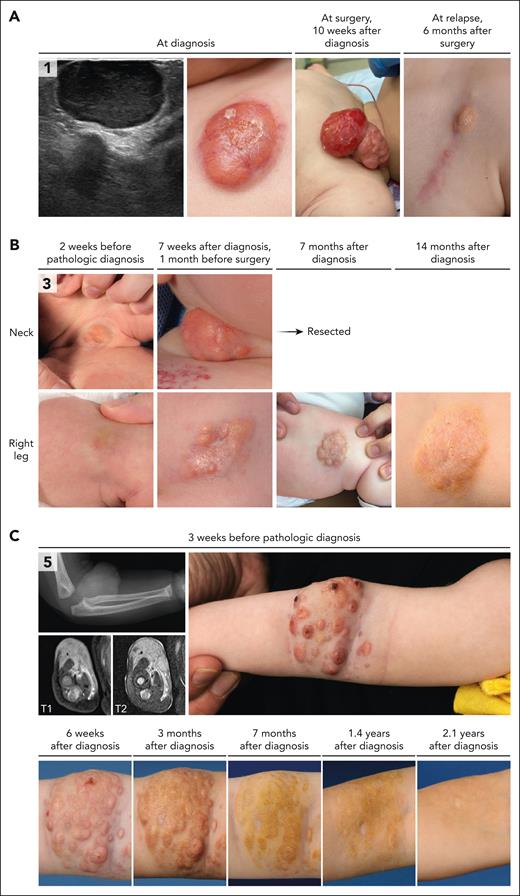

After diagnosis, both lesions progressed (Figure 1B). The tumor in the neck limited the child and was therefore resected. The upper leg lesion continued to grow for several months, but eventually regressed spontaneously.

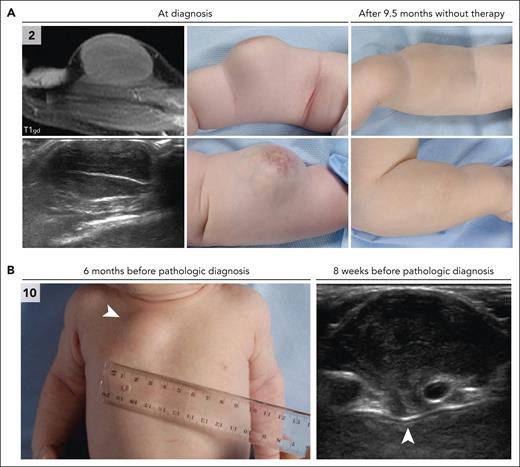

Initially, a diagnosis of self-limiting sternal tumor of childhood was assumed, and the patient was managed by active monitoring. However, ultrasound revealed slow progression of the parasternal lesion during follow-up; therefore, subtotal resection was performed at 6.5 months after presentation.

Initially, an active monitoring strategy was pursued. The lesion slowly progressed; therefore, resection was performed 7.5 months after the diagnostic biopsy.

Clinicopathologic features of histiocytic neoplasms with CSF1R mutations

CSF1R alterations were detected in 7 children, including 6 males and 1 female (Table 1). Five had a deletion in exon 12 of CSF1R (NM_005211.3), whereas 1 patient had multiple missense mutations in exons 9 and 10, and the female patient had a large deletion of exons 21 and 22, in addition to an MRC1::PDGFRB fusion. The 5 children with exon 12 deletions were between 1 and 4 months old at the time of histopathologic diagnosis; 3 of 5 had tumors at birth. The tumors were up to 4 cm large, with occasional ulceration and a remarkable nodular aspect of some lesions (Figure 1). Two patients had multifocal tumors, including case 3 with a neck and upper leg lesion (Figure 1B) and case 7 with a subcutaneous scalp lesion and intramuscular tumor on the back. In case 5, the subcutaneous tumor extended inward between the forearm muscles (Figure 1C). Most tumors were resected surgically, although spontaneous regression of lesions was observed in 2 patients (Figure 1B-C). At last follow-up, 3 of 5 patients were in complete remission (at 2-11 years after diagnosis), whereas 2 of 5 still had active disease.

Clinical and radiologic features of patients with CSF1R mutations. (A) Ultrasound and clinical images of the lesion of case 1. This infant was noted to have a small red/purple lesion on the chest at birth. The lesion increased in size over time and developed a central crust. Ultrasound revealed a well-demarcated, homogeneous, hypoechoic lesion with rich vascularization. A biopsy was taken 7 weeks after birth, leading to a diagnosis of JXG. The lesion continued to grow rapidly, with recurrent ulceration and occasional bleeding, before it was resected at 10 weeks after diagnosis. A small recurrence was observed in the scar at 6 months after surgery; this lesion was left untreated and slowly regressed over the following 2 years. (B) Clinical images of the multifocal lesions in case 3. Both lesions were present at birth and progressed over time. A biopsy was taken of the right upper leg lesion 8 weeks after birth and revealed JXG. In the following weeks, the right sided neck lesion grew significantly, and the infant developed a head turning preference for the left side. Therefore, it was decided to resect the neck tumor. The right upper leg lesion continued to grow for several months but eventually regressed spontaneously. (C) Radiologic and clinical images of the tumor in case 5. This infant was noted to have 2 small lesions on the proximal right lower arm at birth. In the following months, a large tumor developed in the lower arm, with a remarkable nodular aspect. Conventional radiography demonstrated intact osseous structures. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at 4 months after birth revealed a 2.8 × 1.6 × 4.2 cm large soft tissue tumor, extending inward between the flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus. A biopsy was taken, leading to a diagnosis of JXG. The patient was managed by active monitoring and experienced spontaneous regression of the tumor. T1, longitudinal relaxation time; T2, transverse relaxation time.

Clinical and radiologic features of patients with CSF1R mutations. (A) Ultrasound and clinical images of the lesion of case 1. This infant was noted to have a small red/purple lesion on the chest at birth. The lesion increased in size over time and developed a central crust. Ultrasound revealed a well-demarcated, homogeneous, hypoechoic lesion with rich vascularization. A biopsy was taken 7 weeks after birth, leading to a diagnosis of JXG. The lesion continued to grow rapidly, with recurrent ulceration and occasional bleeding, before it was resected at 10 weeks after diagnosis. A small recurrence was observed in the scar at 6 months after surgery; this lesion was left untreated and slowly regressed over the following 2 years. (B) Clinical images of the multifocal lesions in case 3. Both lesions were present at birth and progressed over time. A biopsy was taken of the right upper leg lesion 8 weeks after birth and revealed JXG. In the following weeks, the right sided neck lesion grew significantly, and the infant developed a head turning preference for the left side. Therefore, it was decided to resect the neck tumor. The right upper leg lesion continued to grow for several months but eventually regressed spontaneously. (C) Radiologic and clinical images of the tumor in case 5. This infant was noted to have 2 small lesions on the proximal right lower arm at birth. In the following months, a large tumor developed in the lower arm, with a remarkable nodular aspect. Conventional radiography demonstrated intact osseous structures. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at 4 months after birth revealed a 2.8 × 1.6 × 4.2 cm large soft tissue tumor, extending inward between the flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus. A biopsy was taken, leading to a diagnosis of JXG. The patient was managed by active monitoring and experienced spontaneous regression of the tumor. T1, longitudinal relaxation time; T2, transverse relaxation time.

The 2 patients with alternative CSF1R mutations had distinctive clinical features. Case 13 with multiple mutations in exons 9 and 10 was a 1-year-old male with an endotracheal pedunculated tumor. The tumor was resected, without evidence of local recurrence or distant spread at 2.2 years of follow-up. Case 6 with a large deletion of CSF1R exons 21 and 22 and an additional MRC1::PDGFRB fusion was a 3-month-old female with a large intra-abdominal tumor involving the greater omentum. In addition, multiple small lesions on the intestinal walls and in the liver hilum were observed during laparoscopy. Subtotal surgical resection was performed, and the patient achieved complete remission without disease relapse during 24 years of follow-up.

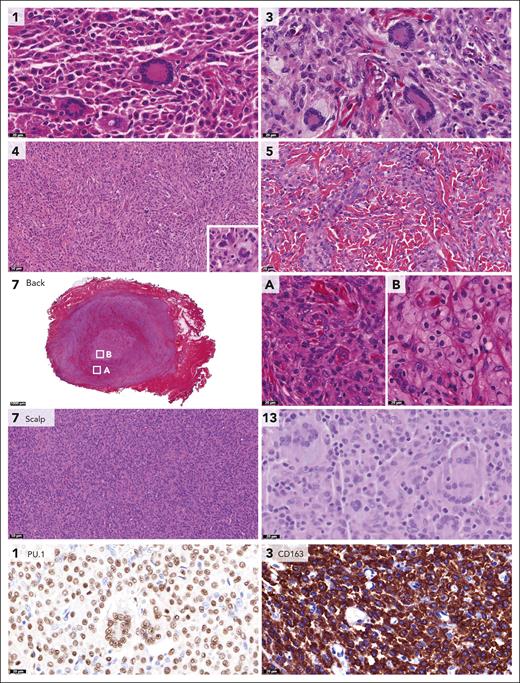

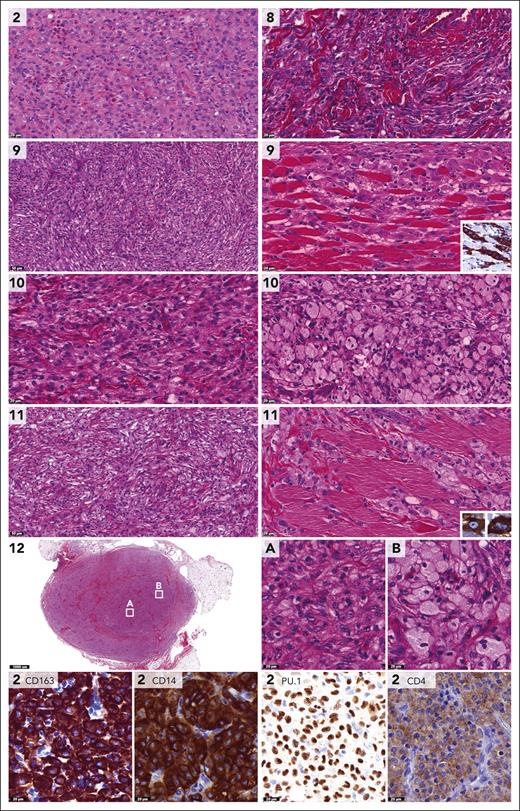

Histopathologic features of CSF1R-mutated tumors were those of the JXG family (Figure 2).1,2 Lesions were characterized by dense infiltrates of cells with round to ovoid or sometimes elongated nuclei, often conspicuous nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasm. Mitotic rates were low, and cytological atypia was not observed. Touton giant cells were abundant in some (cases 1, 3, and 13), occasional in others (cases 4-5) and absent in 2 of 7 (cases 6-7). A storiform-like pattern was noted in cases 4 and 6 (Figure 2). The number of xanthomatous cells varied between patients and samples; for example, the intramuscular tumor on the back in case 7 contained large collections of foamy histiocytes, whereas the scalp lesion of this patient consisted of a dense monomorphic infiltrate without lipidized histiocytes (Figure 2). Collections of foamy histiocytes were also observed in case 6 with a CSF1R deletion and an MRC1::PDGFRB fusion (supplemental Figure 1). Tumor cells stained positive for CD68, CD163, and PU.1 (supplemental Table 3).

Pathologic features of histiocytic neoplasms with CSF1R mutations. Photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–, PU.1-, or CD163-stained slides. Numbers indicate cases. Shown are the histiocytic lesions with multiple Touton giant cells in cases 1 and 3, the storiform-like histologic pattern in case 4 (with a multinucleated cell in the inlet), and the monomorphic histiocytic infiltrate dissecting through the dermal collagen bundles in case 5. In addition, the intramuscular tumor of case 7 is depicted, which was located on the back and contained large collections of foamy histiocytes. In contrast, the scalp lesion of case 7 consisted of a dense monomorphic infiltrate without lipidized histiocytes. Finally, the endotracheal tumor of case 13 was characterized by multiple Touton and Touton-like giant cells (the latter have no or limited foamy cytoplasm), in addition to many mononucleated histiocytes with predominantly round to ovoid nuclei. Histiocytes stained positive for PU.1 and CD163, as illustrated by photomicrographs of the tumors of cases 1 and 3. Histology of the abdominal tumor of case 6 with a CSF1R deletion and an MRC1::PDGFRB fusion is provided in supplemental Figure 1.

Pathologic features of histiocytic neoplasms with CSF1R mutations. Photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–, PU.1-, or CD163-stained slides. Numbers indicate cases. Shown are the histiocytic lesions with multiple Touton giant cells in cases 1 and 3, the storiform-like histologic pattern in case 4 (with a multinucleated cell in the inlet), and the monomorphic histiocytic infiltrate dissecting through the dermal collagen bundles in case 5. In addition, the intramuscular tumor of case 7 is depicted, which was located on the back and contained large collections of foamy histiocytes. In contrast, the scalp lesion of case 7 consisted of a dense monomorphic infiltrate without lipidized histiocytes. Finally, the endotracheal tumor of case 13 was characterized by multiple Touton and Touton-like giant cells (the latter have no or limited foamy cytoplasm), in addition to many mononucleated histiocytes with predominantly round to ovoid nuclei. Histiocytes stained positive for PU.1 and CD163, as illustrated by photomicrographs of the tumors of cases 1 and 3. Histology of the abdominal tumor of case 6 with a CSF1R deletion and an MRC1::PDGFRB fusion is provided in supplemental Figure 1.

Clinicopathologic features of histiocytic neoplasms with CLTC::SYK fusions

CLTC::SYK fusions were detected in 6 children, including 3 males and 3 females (Table 1). Patients were between 2 and 12 months old at the time of histopathologic diagnosis; 1 of 6 had a noticeable tumor at birth. All children had unifocal soft tissue tumors, which were up to 7 cm large and were generally characterized by no or limited superficial skin changes (Figure 3). The tumors were frequently located on or just above the fascia of a muscle, although case 9 had an intramuscular tumor. In case 10, the parasternal mass extended between the ribs to the parietal pleura (Figure 3). Five patients were treated surgically, whereas case 2 was managed by active monitoring and experienced spontaneous regression of the tumor (Figure 3). At last follow-up, all 6 patients had no evidence of disease nor had experienced a relapse, including 3 patients with long-term follow-up (12 to 25 years).

Clinical and radiologic features of patients with CLTC::SYK fusions. (A) Radiologic and clinical images of the tumor in case 2. The tumor of the right lower arm was present at birth and had rapidly increased in size over time. On physical examination, the tumor was firm, adherent to the underlying musculature, and separate from the skin. The overlying skin exhibited telangiectatic changes, possibly because of fast growth of the tumor. Ultrasound revealed a well-demarcated, hypoechoic, vascularized lesion. MRI demonstrated that the tumor was closely related to the underlying extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle. A biopsy was taken 2 months after birth and a diagnosis of JXG was made. The patient was managed by active monitoring and the tumor gradually decreased in size and consistency. At a follow-up visit 1.6 years after diagnosis, the tumor was no longer recognizable. (B) Clinical and ultrasound images of the tumor in case 10. This infant presented 4 weeks after birth with a thoracal mass that had been noted by the parents for 1 day. On physical examination, the mass was firm-elastic, nontender, adherent to the underlying tissue, and separate from the skin. The patient had no other symptoms; therefore, a diagnosis of self-limiting sternal tumor of childhood37 was assumed, and the patient was managed by active monitoring. Follow-up ultrasound evaluations revealed slow progression of the parasternal lesion, which extended between the second and third ribs to the parietal pleura. Therefore, subtotal surgical resection was eventually performed at 6.5 months after presentation; pathological analysis resulted in a diagnosis of JXG. At 2 months after surgery, the parasternal lesion was not detectable using ultrasound and the child was in clinical remission.

Clinical and radiologic features of patients with CLTC::SYK fusions. (A) Radiologic and clinical images of the tumor in case 2. The tumor of the right lower arm was present at birth and had rapidly increased in size over time. On physical examination, the tumor was firm, adherent to the underlying musculature, and separate from the skin. The overlying skin exhibited telangiectatic changes, possibly because of fast growth of the tumor. Ultrasound revealed a well-demarcated, hypoechoic, vascularized lesion. MRI demonstrated that the tumor was closely related to the underlying extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle. A biopsy was taken 2 months after birth and a diagnosis of JXG was made. The patient was managed by active monitoring and the tumor gradually decreased in size and consistency. At a follow-up visit 1.6 years after diagnosis, the tumor was no longer recognizable. (B) Clinical and ultrasound images of the tumor in case 10. This infant presented 4 weeks after birth with a thoracal mass that had been noted by the parents for 1 day. On physical examination, the mass was firm-elastic, nontender, adherent to the underlying tissue, and separate from the skin. The patient had no other symptoms; therefore, a diagnosis of self-limiting sternal tumor of childhood37 was assumed, and the patient was managed by active monitoring. Follow-up ultrasound evaluations revealed slow progression of the parasternal lesion, which extended between the second and third ribs to the parietal pleura. Therefore, subtotal surgical resection was eventually performed at 6.5 months after presentation; pathological analysis resulted in a diagnosis of JXG. At 2 months after surgery, the parasternal lesion was not detectable using ultrasound and the child was in clinical remission.

Similar to the CSF1R-mutated neoplasms, the overall morphologic and immunophenotypic features of tumors with CLTC::SYK fusions were those of the JXG family (Figure 4). Again, lesions were characterized by dense infiltrates of cells with round to ovoid nuclei and sometimes more spindled morphology. Mitotic rates were low, and cytological atypia was not observed. In cases 9 and 11, a storiform-like pattern and histiocytes dissecting through the musculature were noted (Figure 4). Xanthomatous histiocytes were dominant, with collections of foamy cells in multiple samples (Figure 4). Eosinophilic granulocytes were frequent in some tumors (cases 2 and 9) but rare in others. The main difference with CSF1R-mutated neoplasms was that tumors with CLTC::SYK fusions generally lacked Touton giant cells, with only a rare Touton-type giant cell observed in case 12 (supplemental Figure 2). The absence of Touton giant cells was previously noted by Crowley et al in 3 cases38 and by Glembocki et al in a single case39; the clinicopathologic features of these 4 cases and our 6 patients with CLTC::SYK fusions are summarized in Table 2. Tumor cells stained positive for CD68, CD163, PU.1, and CD14, whereas CD4 was often more weakly positive and OCT2 weak to negative (Table 2; Figure 4). Negative stains included S100, CD1a, cytokeratin AE1/3, and smooth muscle actin.

Pathologic features of histiocytic neoplasms with CLTC::SYK fusions. Photomicrographs of H&E-, CD163-, CD14-, PU.1-, or CD4-stained slides. Numbers indicate cases. Depicted are the dense histiocytic lesion with interspersed eosinophilic granulocytes in case 2, and histiocytic cells in between hyalinized collagen in case 8. In addition, the storiform-like histologic patterns in cases 9 and 11 are shown, as well as the histiocytes dissecting through the musculature that were observed in these cases. The inlets demonstrate that the cells stained positive for CD163 and had variable nuclear contours. The images of cases 10 and 12 depict dense populations of cells with xanthomatized eosinophilic cytoplasm, as well as collections of foamy histiocytes. As illustrated by photomicrographs of the tumor of case 2, histiocytes stained positive for CD163, CD14, and PU.1, whereas CD4 was more weakly positive.

Pathologic features of histiocytic neoplasms with CLTC::SYK fusions. Photomicrographs of H&E-, CD163-, CD14-, PU.1-, or CD4-stained slides. Numbers indicate cases. Depicted are the dense histiocytic lesion with interspersed eosinophilic granulocytes in case 2, and histiocytic cells in between hyalinized collagen in case 8. In addition, the storiform-like histologic patterns in cases 9 and 11 are shown, as well as the histiocytes dissecting through the musculature that were observed in these cases. The inlets demonstrate that the cells stained positive for CD163 and had variable nuclear contours. The images of cases 10 and 12 depict dense populations of cells with xanthomatized eosinophilic cytoplasm, as well as collections of foamy histiocytes. As illustrated by photomicrographs of the tumor of case 2, histiocytes stained positive for CD163, CD14, and PU.1, whereas CD4 was more weakly positive.

Clinical, molecular, and pathologic features of cases with CLTC::SYK fusions

| . | This study . | Prior reports . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case no. | 2 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | G1 | C1 | C2 | C3 |

| Clinical features | ||||||||||

| Age at diagnosis, months | 2 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 15 |

| Sex | M | F | F | F | M | M | F | ? | F | F |

| Location soft tissue tumor | Forearm | Scalp | Groin | Chest wall | Abdom wall | Upper leg | Scap region | Chest wall | Upper arm | Scalp |

| Progression/relapse | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Follow-up, years | 12.1 | 25.3 | 0.03 | 13.5 | 0.6 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 4.0 |

| Fusion detection | ||||||||||

| DNA sequencing | + | + | + | + | + | + | NP | + | + | + |

| Breakpoint-specific PCR | + | + | + | + | + | + | NP | NP | NP | NP |

| RNA sequencing | NP | NP | + | + | Failed | + | + | + | Failed | NP |

| SYK FISH | Failed | + | + | + | Failed | + | NP | + | + | + |

| CNV analysis | − | − | − | − | − | − | NP | NP | − | NP |

| Pathologic features | ||||||||||

| Touton giant cells | No | No | No | No | No | No∗ | No | No | No | No |

| CD68 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| PU.1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| CD14 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| CD163 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| CD4 | dim+ | dim+ | dim+ | dim+ | dim+ | + | + | |||

| OCT2 | −/bl | −/bl | −/bl | −/bl | −/bl | −/bl | ||||

| S100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CD1a | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Cyclin D1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| SYK | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| p-SYK | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| p-S6 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| p-ERK | rare+ | rare+ | rare+ | rare+ | + | + | ||||

| p-AKT | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||||

| Cytokeratin AE1/3 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| (Smooth muscle) actin | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| . | This study . | Prior reports . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case no. | 2 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | G1 | C1 | C2 | C3 |

| Clinical features | ||||||||||

| Age at diagnosis, months | 2 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 15 |

| Sex | M | F | F | F | M | M | F | ? | F | F |

| Location soft tissue tumor | Forearm | Scalp | Groin | Chest wall | Abdom wall | Upper leg | Scap region | Chest wall | Upper arm | Scalp |

| Progression/relapse | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Follow-up, years | 12.1 | 25.3 | 0.03 | 13.5 | 0.6 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 4.0 |

| Fusion detection | ||||||||||

| DNA sequencing | + | + | + | + | + | + | NP | + | + | + |

| Breakpoint-specific PCR | + | + | + | + | + | + | NP | NP | NP | NP |

| RNA sequencing | NP | NP | + | + | Failed | + | + | + | Failed | NP |

| SYK FISH | Failed | + | + | + | Failed | + | NP | + | + | + |

| CNV analysis | − | − | − | − | − | − | NP | NP | − | NP |

| Pathologic features | ||||||||||

| Touton giant cells | No | No | No | No | No | No∗ | No | No | No | No |

| CD68 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| PU.1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| CD14 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| CD163 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| CD4 | dim+ | dim+ | dim+ | dim+ | dim+ | + | + | |||

| OCT2 | −/bl | −/bl | −/bl | −/bl | −/bl | −/bl | ||||

| S100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CD1a | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Cyclin D1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| SYK | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| p-SYK | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| p-S6 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| p-ERK | rare+ | rare+ | rare+ | rare+ | + | + | ||||

| p-AKT | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||||

| Cytokeratin AE1/3 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| (Smooth muscle) actin | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |||

+, positive; −, negative; ?, unknown; −/bl, weak blush to negative; Abdom, abdominal; CNV, copy number variation; dim, weakly; F, female; M, male; NP, not performed/not reported; p, phosphorylated; rare, rare cells; Scap, scapular.

Potentially rare Touton giant cell (see supplemental Figure 2).

Multimodal detection and characterization of CLTC::SYK fusions

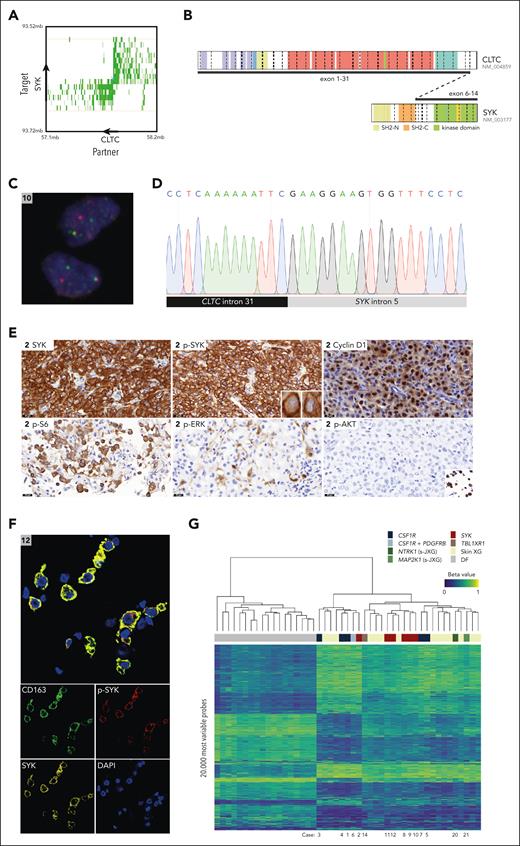

SYK fusions detected by TLC-NGS were validated by break point–specific PCR and Sanger sequencing in 6 of 6 cases (Figure 5; supplemental Figure 3). In addition, we confirmed the presence of the translocation in the lesional cell population using SYK break-apart FISH, which was interpretable in 4 of 6 cases. Genomic break points of the CLTC::SYK fusions were located in either exon 5 or intron 5 of SYK. Whole transcriptome sequencing of the tumors of cases 9, 10, and 12 demonstrated that break points in exon 5 or intron 5 both lead to fusion of CLTC exon 31 to SYK exon 6 at the messenger RNA level. Thus, exon 5 break points seem to result in alternative splicing through exon skipping.

Multimodal detection and characterization of CLTC::SYK fusions. (A) Exemplary butterfly plot of TLC-NGS data, uncovering the CLTC::SYK fusion in case 12. Proximity ligation products between the target gene (SYK) and rearrangement partner (CLTC) are depicted in green. The shade of green indicates the coverage. Strand directions are indicated by arrows. Details of TLC-NGS methodology are available in a prior publication by Allahyar et al.22 (B) Illustration of the CLTC::SYK fusion, which leads to a transcript joining CLTC exon 31 to SYK exon 6, as demonstrated by RNA sequencing. (C) Photomicrograph showing separation of red and green signals in lesional cells of the tumor of case 10 using SYK break-apart FISH. The green signal represents the FITC-labeled probes (which bind proximal of SYK), whereas the red signal represents the Cy3-labeled probes (which bind distal of SYK). (D) Sanger sequence demonstrating the fusion of CLTC intron 31 to SYK intron 5 in case 9. Sanger sequencing results for all patients with CLTC::SYK fusions are depicted in supplemental Figure 3. (E) Exemplary photomicrographs of the tumor of case 2, demonstrating expression of SYK, p-SYK, cyclin D1, and p-S6 (a marker of mTOR activation). In addition, rare p-ERK+ cells can be observed, whereas tumor cells were negative for p-Akt despite adequate positive external controls (endometrial cancer with PIK3CAH1047R mutation; SignalSlide Akt Family IHC Control from Cell Signaling). The SignalSlide Akt Family IHC Control is shown in the inlet. P-ERK expression of all tumors with CLTC::SYK fusions is depicted in supplemental Figure 2. (F) Exemplary multispectral immunofluorescence image of the tumor of case 12, demonstrating SYK and p-SYK expression by CD163+ histiocytes. (G) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of 29 XG family lesions and 18 common or atypical dermatofibromas (DF; included as controls) using the methylation data of the 20 000 most variable probes. In the heat map, columns represent samples, and rows represent probes. The level of DNA methylation is indicated by beta values and depicted using a color scale. A beta value of 1 corresponds to a fully methylated CpG site; a value of 0 to an unmethylated site. Above the heat map, the clinical and/or molecular subgroup is shown for each sample; below the heat map, case numbers of patients described in this study are depicted. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; IHC, immunohistochemistry. Panel B illustration made with the St Jude ProteinPaint web application.

Multimodal detection and characterization of CLTC::SYK fusions. (A) Exemplary butterfly plot of TLC-NGS data, uncovering the CLTC::SYK fusion in case 12. Proximity ligation products between the target gene (SYK) and rearrangement partner (CLTC) are depicted in green. The shade of green indicates the coverage. Strand directions are indicated by arrows. Details of TLC-NGS methodology are available in a prior publication by Allahyar et al.22 (B) Illustration of the CLTC::SYK fusion, which leads to a transcript joining CLTC exon 31 to SYK exon 6, as demonstrated by RNA sequencing. (C) Photomicrograph showing separation of red and green signals in lesional cells of the tumor of case 10 using SYK break-apart FISH. The green signal represents the FITC-labeled probes (which bind proximal of SYK), whereas the red signal represents the Cy3-labeled probes (which bind distal of SYK). (D) Sanger sequence demonstrating the fusion of CLTC intron 31 to SYK intron 5 in case 9. Sanger sequencing results for all patients with CLTC::SYK fusions are depicted in supplemental Figure 3. (E) Exemplary photomicrographs of the tumor of case 2, demonstrating expression of SYK, p-SYK, cyclin D1, and p-S6 (a marker of mTOR activation). In addition, rare p-ERK+ cells can be observed, whereas tumor cells were negative for p-Akt despite adequate positive external controls (endometrial cancer with PIK3CAH1047R mutation; SignalSlide Akt Family IHC Control from Cell Signaling). The SignalSlide Akt Family IHC Control is shown in the inlet. P-ERK expression of all tumors with CLTC::SYK fusions is depicted in supplemental Figure 2. (F) Exemplary multispectral immunofluorescence image of the tumor of case 12, demonstrating SYK and p-SYK expression by CD163+ histiocytes. (G) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of 29 XG family lesions and 18 common or atypical dermatofibromas (DF; included as controls) using the methylation data of the 20 000 most variable probes. In the heat map, columns represent samples, and rows represent probes. The level of DNA methylation is indicated by beta values and depicted using a color scale. A beta value of 1 corresponds to a fully methylated CpG site; a value of 0 to an unmethylated site. Above the heat map, the clinical and/or molecular subgroup is shown for each sample; below the heat map, case numbers of patients described in this study are depicted. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; IHC, immunohistochemistry. Panel B illustration made with the St Jude ProteinPaint web application.

Tumors with CLTC::SYK fusions strongly expressed p-SYK, indicative of SYK activation (Figure 5E). Using multispectral immunofluorescence, p-SYK expression was demonstrated in CD163+ histiocytes rigorously (Figure 5F). The tumor cells also stained positive for cyclin D1 and p-S6, a marker of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation.40,41 Moreover, p-ERK expression was observed in both mononucleated and multinucleated cells in cases 11 and 12, whereas rare p-ERK+ cells were seen in the other 4 cases (supplemental Figure 2). p-Akt immunohistochemistry was consistently negative.

Genome-wide methylation profiling revealed that histiocytic tumors with CLTC::SYK fusions did not have a distinct methylation profile from other XG family lesions (Figure 5G). Although XG family lesions clustered separately from common and atypical dermatofibromas (control), there was no segregation of molecular and/or clinical subgroups within the XG family lesions. More specifically, both CSF1R mutations and CLTC::SYK fusions were present in each of the 2 major clusters identified within the XG family lesions. Considering the pronounced similarities between these 2 clusters, the biological significance of their distinction is questionable; instead, one could also deduce that XG family lesions have a common methylation profile. Furthermore, tumors with CLTC::SYK fusions did not have a distinct copy number signature, as they displayed flat copy number profiles like CSF1R-mutated lesions (supplemental Figure 4).

Adults with soft tissue XGs

The 4 adults were between 18 and 58 years old at diagnosis and had unifocal tumors in the nasopharynx (case 14), paranasal sinus (case 15), pubic region (case 16) or scalp (case 17) that were surgically resected. The TBL1XR1::BOD1L1 fusion in case 14 was detected on both the DNA and RNA levels, using TLC-NGS, FISH, and whole transcriptome sequencing. In addition, the reciprocal BOD1L1::ABHD10 fusion was detected by TLC-NGS. The tumor had XG histology with abundant Touton giant cells and collections of foamy histiocytes (supplemental Figure 5) and a flat copy number profile (supplemental Figure 6). The tumors in cases 15 and 16 also contained Touton giant cells, whereas the scalp lesion in case 17 was mostly characterized by mononucleated foamy histiocytes, with remarkable extension into the underlying bone.

Patients with isolated CNS-XGs

The 2 patients were a 5-month-old girl with an intramedullary spinal cord tumor (case 18) and a 50-year-old woman with multifocal tumors in the brain and spinal cord (case 19). Complete systemic assessments revealed no lesions outside the nervous system. Both patients harbored BRAFV600E and were successfully treated with BRAF inhibitors, as described in detail elsewhere.42 The resected cerebellar tumor of case 19 exhibited XG histology with abundant Touton giant cells (supplemental Figure 7). In case 18, mostly bland histiocytes and rare multinucleated giant cells with a ring of nuclei, suggestive of a Touton giant cell, were seen (supplemental Figure 7). The histology was somewhat atypical, with an elevated Ki67 proliferation index (30-40%) and rare mitotic figures (up to 1-2 per 10 high power field). However, no atypical mitoses or other histologic features supporting a diagnosis of malignant histiocytosis were observed; therefore, a diagnosis of CNS-JXG was made. The tumor was found to harbor multiple copy number alterations (supplemental Figure 6), which may have contributed to the atypical histologic features.

Children with systemic JXG

The 2 children included 1 female infant with a single skin lesion and congenital anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly who required multiple transfusions (case 20) and a 2-year-old girl with a thickened pituitary stalk, bilateral lung lesions, enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, and papular skin lesions (case 21; supplemental Figure 8). Spontaneous disease regression was observed in both patients, although this took multiple years in case 21 (supplemental Figure 8). Touton giant cells were abundant in case 20 and absent in case 21 (supplemental Figure 8). In both, mitotic rates were low, cytological atypia was not observed, and flat copy number profiles were obtained (supplemental Figure 6).

Discussion

We present detailed clinicopathologic and molecular data of 16 children with extracutaneous JXG and 5 adults with XGs confined to the CNS or soft tissue. Using an innovative sequencing technique, we identified recurrent CLTC::SYK fusions and CSF1R mutations in children below 2 years of age with soft tissue tumors. In 1 child, we identified both a CSF1R deletion and an MRC1::PDGFRB fusion. In addition, we detected targetable alterations of BRAF, MAP2K1, or NTRK1 in patients with CNS-XG or systemic JXG.

CSF1R encodes for colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF-1R), a receptor tyrosine kinase involved in monocyte and macrophage development.43-46CSF1R mutations have previously been described in patients with different histiocytic neoplasms, but clinicopathologic data were often scarce.8,11,47-49 Most reported JXG cases had CSF1R exon 12 indels,8,11 which were also detected in 5 of our cases and have been rarely described in adults with ECD or malignant histiocytosis.8,47,49 These mutations affect the intracellular, autoinhibitory, juxtamembrane domain of CSF-1R, leading to constitutive activation of the receptor.8,49 Activation of CSF-1R induces signal transduction through the MAPK and PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathways,8,49 with preferential activation of the latter.49 The activation of multiple downstream signaling pathways has therapeutic implications, as illustrated by a recent case report of a woman with CSF1R-mutated ECD who did not respond to the MEK inhibitor cobimetinib but did have a complete response to the CSF-1R inhibitor pexidartinib.49 None of our patients required systemic therapy, and cases 3 and 5 demonstrate that lesions may regress spontaneously (Figure 1). Thus, treatment decisions should be taken with prudence, avoiding mutilating surgery in these young children.

The CSF1R missense mutations in case 13 were mostly located in exon 10, wherein a deletion has previously been detected in a child with LCH.8 Exon 10 mutations affect the extracellular region of CSF-1R and might enhance receptor dimerization.8 In contrast, the large deletion of CSF1R exons 21 and 22 in case 6 affects the intracellular c-CBL binding domain.50 Binding of c-CBL to CSF-1R leads to receptor ubiquitination, which targets it for degradation.50,51CSF1R exon 21 or 22 mutations have been described in different histiocytoses and likely prevent the c-CBL–mediated degradation of CSF-1R.8,11,48 As in our case, CSF1R exon 21/22 mutations were sometimes accompanied by another kinase alteration.48 Durham et al already demonstrated that expression of a CSF1R exon 10 or exon 22 mutation in Ba/F3 cells conferred cytokine-independent growth, supporting their pathogenicity.8

CLTC::SYK fusions were only recently described in histiocytic neoplasms.38,39 All 4 patients in the literature were below 2 years old and had isolated soft tissue tumors, just as our 6 cases. Although Crowley et al considered the tumors to be histopathologically distinct from JXG, we and Glembocki et al advocate that the overall morphologic and immunophenotypic features are those of the JXG family, despite the general absence of Touton giant cells. Notably, Touton giant cells are not an essential diagnostic criterium for JXG.4 Accordingly, Touton giant cells were also absent in other JXG lesions, such as those from cases 6 and 7. In addition, we observed striking histologic similarities between histiocytic lesions with SYK fusions and those with CSF1R mutations (Figures 2 and 4). The tumors with SYK fusions also lacked a distinct methylation profile and exhibited flat copy number profiles like CSF1R-mutated lesions. Finally, the clinical course was characteristic of JXG, with spontaneous regression of lesions or complete remission after (sub)total resection. Therefore, we regard histiocytic tumors with CLTC::SYK fusions as a molecular subtype of the JXG family.

SYK is a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase that is primarily expressed in hematopoietic cells, including B cells, monocytes, and macrophages.52 SYK has diverse biological functions, including mediating signals from B cell receptors, Fc receptors, and adhesion receptors.52 SYK and CSF-1R are also connected, as SYK can be activated by CSF-1R signaling through the intermediary DAP12 protein.44 The kinase domain of SYK is held in an inactive confirmation by the Src homology 2 (SH2) domains.53 The CLTC::SYK fusion results in the deletion of these SH2 domains (Figure 5B) and thereby in a continuously active kinase. CLTC encodes for the clathrin heavy chain; the CLTC::SYK fusion could position the SYK kinase domains at the inside of a clathrin sphere, where they could be protected from proteasomal degradation while still being accessible to their substrate (supplemental Figure 9).

SYK fusions have been described in different hematologic neoplasms, including ITK::SYK in follicular T cell lymphoma54,55 and ETV6::SYK in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL)56 and atypical myeloid neoplasms with eosinophilia and histiocytic skin lesions.57-60 Similar to CLTC::SYK, these fusions result in a transcript joining a gene fusion partner to SYK exon 6.56-58 Expression of these SYK fusions in Ba/F3 cells conferred cytokine-independent growth and activation of SYK and its downstream targets, including the MAPK and PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathways.57,58,61,62 Although we observed p-ERK expression in some of our cases (supplemental Figure 2), a consistent lack of p-Akt expression was noted in tumors with CLTC::SYK fusions. All tumors stained positive for p-S6, suggesting that Akt-independent mechanisms of mTOR activation may be at play.63,64 Activation of mTOR is targetable, with clinical efficacy of the mTOR inhibitor sirolimus already demonstrated in ECD65 and in some cases of JXG.66 Furthermore, all tumors stained positive for cyclin D1, which is an emerging marker of neoplastic histiocytes.9,21,67-71 Cyclin D1 expression is generally attributed to MAPK pathway activation,67,69 although strong expression has also been observed in cases without MAPK pathway mutations and/or lack of p-ERK expression.21,70,71 MAPK pathway inhibition is often effective in histiocytic neoplasms,72-74 and the ETV6::SYK fusion appears to confer partial susceptibility to MEK inhibition.59 Thus, tumors with CLTC::SYK fusions may also respond to this targeted therapy. Finally, several oral SYK inhibitors have been developed, such as fostamatinib and entospletinib.75ETV6::SYK-transformed cells were sensitive to SYK inhibition in vitro,58 and a patient with an ETV6::SYK–rearranged myeloid neoplasm experienced a partial response to fostamatinib.60 Although none of our patients with CLTC::SYK fusions required systemic therapy, the discovery of activating SYK fusions opens novel opportunities for targeted therapy when necessary.

The MRC1::PDGFRB fusion detected in case 6 has been previously described in a child with JXG of soft tissue3; therefore, we establish it as another recurrent genetic abnormality in extracutaneous JXG. Strikingly, this patient from the literature had a chemotherapy-refractory left chest wall mass and was treated with dasatinib.3 In contrast, subtotal surgical resection was performed in our case, without disease recurrence after 24 years of follow-up. Thus, the clinical course of patients with identical kinase alterations can be variable. The significance of the TBL1XR1::BOD1L1 (and reciprocal BOD1L1::ABHD10) fusion in case 14 is uncertain. Although TBL1XR1 loss-of-function mutations have been described in lymphomas76 and the gene is a recurrent fusion partner,77-80 the fusion with BOD1L1 has not been previously described. BOD1L1 is a genome stability factor,81 whereas ABHD10 is a mitochondrial protein82; neither has been implicated in oncogenic gene fusions. When another tumor harboring this fusion is identified, functional studies are warranted. Finally, BRAFV600E is an established driver of CNS-XG,2 and MAP2K1 and NTRK1 are recurrently altered in histiocytic neoplasms.7,8,83-85 Activating alterations of these genes are targetable, with robust and durable responses to BRAF inhibition in both of our patients with CNS-XG.42 For systemic JXG, therapy is not always needed, as illustrated by our 2 cases.

Although we identified cases from a nationwide pathology databank, we cannot rule out some selection bias limiting our study. Because no separate diagnostic code for extracutaneous JXG exists, we were reliant on free-text queries of retrieved pathology reports. It is remarkable that we did not identify cases with BRAF fusions, because these rearrangements have been previously identified in (extracutaneous) XG family lesions.86 Furthermore, staging was performed according to standard-of-care practices at local institutions; therefore, not all patients were systematically evaluated using the same imaging techniques (eg, positron emission tomography). Yet, both patients with ECD-associated BRAFV600E mutations did not have extracutaneous lesions by magnetic resonance imaging (case 18) or positron emission tomography (case 19). Finally, we used a targeted sequencing approach (TLC-NGS); therefore, we might have missed relevant genetic alterations, for example in cases 15 to 17. More comprehensive molecular techniques are probably required to uncover (novel) genomic drivers in such cases. With TLC-NGS, however, we could analyze up to decades-old FFPE samples of this rare neoplasm.

In conclusion, we identify targetable kinase alterations in extracutaneous JXG, including recurrent CLTC::SYK fusions and CSF1R mutations. Supported by detailed clinicopathologic data, our study advances the molecular understanding of this rare disease and may provide guidance for the diagnosis and clinical management of patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the immunolaboratories of the Departments of Pathology of Leiden University Medical Center and the Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology for performing additional immunohistochemical stains and M. J. Koudijs (Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology) for performing RNA sequencing. The authors also thank the Departments of Pathology of Maastricht University Medical Center, Haga Hospital, and Deventer Hospital for providing individual tissue samples; J. C. Jansen, J. P. W. Don Griot, M. Donker, and J. H. Allema for providing clinical information and/or images of individual patients. Finally, they thank the patients and/or their parents for allowing the use of medical photographs.

This work was supported by a grant from Stichting de Merel (P.G.K., T.v.W., A.G.S.v.H., and P.C.W.H.). P.G.K. received an MD/PhD grant from Leiden University Medical Center.

Authorship

Contribution: P.G.K., A.G.S.v.H., and P.C.W.H. designed the study; H.J.B. and K.S. performed and/or supervised fluorescence in situ hybridization experiments; R.H.P.V. subjected the sequencing data to the published somatic variant calling pipeline24; M.H.L. performed the in silico structural analysis of the CLTC::SYK fusion; B.K. helped with multispectral immunofluorescence imaging; I.H.B.-d.B. supervised immunohistochemistry; M.A.-H. provided tissue samples of common and atypical dermatofibromas for methylation profiling; S.W.L., J.V.M.G.B., A.H.G.C., R.M.V., C.J.M.v.N., M.R.v.D., M.A.S.-V., and P.C.W.H. were involved in the routine pathologic evaluation of included patients and/or provided archived tissue samples; P.C.W.H. performed the central pathology review; A.H.B. helped with selecting the Palga search strategy and assisted in the Palga intermediary procedure; J.A.M.v.L., A.C.H.d.V., W.J.E.T., and C.v.d.B. were involved in the clinical care of patients and provided pseudonymized clinical data and images; J.F.S. and E.S. assisted in targeted locus capture–based next-generation sequencing (TLC-NGS) panel design, performed TLC-NGS, and analyzed sequencing data for structural variants; A.v.D. coordinated the DNA methylation profiling; T.v.W. reviewed genetic variants called by the variant calling pipeline; P.G.K. collected all information, performed experiments, made the figures and tables, and drafted the manuscript; T.v.W., A.G.S.v.H., and P.C.W.H. revised the manuscript; all authors have reviewed and approved the manuscript before submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.F.S. and E.S. are employees of Cergentis BV (a Solvias company). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Paul G. Kemps, Department of Pathology, Leiden University Medical Center, PO Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands; email: p.g.kemps@lumc.nl.

References

Author notes

The RNA sequencing data (.cram and .crai files) are deposited under restricted access to the European Genome-Phenome Archive (ID number EGAD50000000834).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal