This phase 2 trial assessed high-dose IV ascorbic acid in TET2 mutant clonal cytopenia. Eight of 10 patients were eligible for response assessment, with no responses at week 20 by International Working Group Myelodysplasia Syndromes/Neoplasms criteria. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT03418038.

TO THE EDITOR:

Clonal cytopenia(s) of undetermined significance (CCUS) is defined as persistent cytopenia(s) with myeloid neoplasm (MN)–associated somatic mutations (MTs) in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), not meeting the diagnostic criteria for MN.1 Individuals with CCUS have a 2-year cumulative incidence of progression to MN of 2.8% to 12.6%.2,3 Currently, no US Food and Drug Administration–approved therapies exist,4 and the inclusion, exclusion, and response criteria for CCUS clinical trials remain undefined.5

Although oral ascorbic acid (AA) exhibited minimal anticancer activity, high-dose IV AA at pharmacologic concentrations demonstrates anticancer effects through hydrogen peroxide–induced oxidative stress and DNA demethylation via TET activation.6-8 TET2, a methylcytosine (mC) dioxygenase, oxidizes 5 mC to 5 hydroxymethylcytosine, resulting in DNA demethylation.9 AA is a critical cofactor for TET2, binding to its catalytic domain and enhancing TET activity.10,11 Given the high prevalence of truncating and hypomorphic TET2MT in CCUS, we hypothesized that IV AA could induce epigenetic changes by enhancing TET activity, primarily acting on the wild-type allele and by exploiting functional redundancies in TET1 and TET3, thus restoring DNA methylation, with potential to improve cytopenias.

This investigator-initiated phase 2 trial (NCT03418038) evaluated the safety and preliminary efficacy of IV AA in patients with high-risk CCUS, who are likely to progress to MNs. Eligibility criteria required TET2MT and at least 1 clinically significant cytopenia to be considered as high risk: hemoglobin (Hb) ≤10 g/dL, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≤1 × 109 per liter, and platelet count (PLT) ≤100 × 109 per liter.12 Bone marrow biopsy slides were reviewed at Mayo Clinic, confirming CCUS diagnosis, while excluding bona fide MNs based on the fourth edition World Health Organization criteria (2016).13 IV AA (1 g/kg; maximum 100 g in 1 liter of sterile water) was administered thrice weekly at 0.75 to 1.0 g per minute for 12 weeks via a central venous line. Responses were evaluated at 20 and 52 weeks (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website). The primary end point was hematologic response at week 20, per Myelodysplasia Syndromes/Neoplasms (MDS) International Working Group 2018 criteria,12 reported as hematologic improvement in erythropoietic cells, platelets, and neutrophils. Secondary end points included safety and adverse events (AEs), graded by NCI-CTCAE v4.03.14 Exploratory end points included clonal dynamics and progression to MNs. Correlative studies assessed longitudinal changes in TET2MT variant allele fraction (VAF) and DNA methylation/hydroxymethylation changes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (see the supplemental Material for methods).15

Ten patients were enrolled; 9 were eligible for baseline characteristic analysis (patient 7 was enrolled with a diagnosis of TET2, SRSF2, and KRAS mutant CCUS but in hindsight met the criteria for chronic myelomonocytic leukemia [CMML]); and 8 were eligible for response assessment (patient 5 came off study during cycle 1 due to a central line–associated thrombosis). The median age was 71.7 years (range, 65-79); 78% were male. Among 11 TET2 variants, 64% were truncating, and the remainder were hypomorphic. The median number of somatic MTs was 2 (range, 1-3), with 89% having co-MTs. All but 1 patient had a normal karyotype (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics for the assessable cohort of patients on the clinical trial

| Patient . | Age at diagnosis, y . | Sex . | Baseline Hb, gm/dL . | Baseline PLTs, ×109 per liter . | Baseline ANC, ×109 per liter . | Baseline AMC, ×109 per liter . | Baseline monocyte % . | AA deficiency at baseline . | No. of somatic MTs at time of enrollment . | TET2 MT and VAF, % . | Somatic co-MTs . | Bone marrow karyotype at enrollment . | Bone marrow atypia at enrollment . | Bone marrow cellularity at enrollment . | Clinical outcomes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 73.8 | M | 12.5 | 81 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 14.7% | N | 2 | Q1555V (36%) | SRSF2 P95L (42%) | 46, XY [20] | Slight | Hypercellularity (60%) | Week 20: ANC improvement from CTACE grade 2 to grade 1. Duration of improvement: 18 d |

| 2 | 69.1 | F | 13.5 | 134 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 25.7% | N | 1 | Y163L (31%) | — | 46, XX [20] | None | Normal cellularity | Stable disease at week 20 and week 52, and ANC showed a durable improvement from week 52 onward |

| 3 | 77.4 | M | 12.1 | 117 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 12% | N | 3 | N275I (60%) | ZRSR2 K98Nfs∗10 (27%) | 46, XY [20] | None | Hypercellularity (40%) | Week 20: ANC improvement from CTACE grade 3 to grade 2. Duration of improvement: 119 d. |

| 4 | 64.7 | M | 13.1 | 32 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 17.5% | Y | 2 | R1808∗ (15%) | SRSF2 P95L (43%) | 46, XY,del(20)(q11.2q13.3)[1]/46,XY[16] | Slight | Hypercellularity (—) | Week 20: Met fourth edition WHO criteria for CMML-1 |

| 5 | 73.7 | M | 13.6 | 72 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 11.8% | N | 3 | N1743I (51%) R1214W (16%) | SRSF2 P95R (40%) | 46, XY [20] | Moderate | Normal cellularity | Withdrew from the study due to PICC line thrombosis |

| 6 | 67.4 | M | 7.8 | 409 | 4.9 | 0.4 | 4.5% | N | 2 | L1447R (45%) | SRSF2 P95H (49.9%) | 46, XY [20] | Slight | Hypercellularity (—) | Stable disease at week 20 and week 52 |

| 8 | 77.3 | M | 12.8 | 172 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 25.5% | N | 3 | R250∗ (39%) | ASXL1 L732Yfs∗12 (39%); ZRSR2 Y347Tfs∗? (73%) | 46, XY [20] | Slight | Hypercellularity (60%) | Week 20: Progression to MDS-EB-1 |

| 9 | 79.0 | F | 14.8 | 39 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 22.9% | Y | 2 | C1378Lfs∗70 (39%) | SRSF2 P95H (28%) | 46, XX [20] | None | Hypercellularity (35%) | Stable disease at week 20 and week 52 |

| 10 | 64.9 | M | 12.1 | 100 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 38.9% | N | 3 | G259∗ c.3955-1G>A (39%) | ZRSR2 E49∗ (74%) | 45, X, –Y [20] | Slight | Hypercellularity (—) | Stable disease at week 20, with progression to MDS-EB-1 at week 52 |

| Patient . | Age at diagnosis, y . | Sex . | Baseline Hb, gm/dL . | Baseline PLTs, ×109 per liter . | Baseline ANC, ×109 per liter . | Baseline AMC, ×109 per liter . | Baseline monocyte % . | AA deficiency at baseline . | No. of somatic MTs at time of enrollment . | TET2 MT and VAF, % . | Somatic co-MTs . | Bone marrow karyotype at enrollment . | Bone marrow atypia at enrollment . | Bone marrow cellularity at enrollment . | Clinical outcomes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 73.8 | M | 12.5 | 81 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 14.7% | N | 2 | Q1555V (36%) | SRSF2 P95L (42%) | 46, XY [20] | Slight | Hypercellularity (60%) | Week 20: ANC improvement from CTACE grade 2 to grade 1. Duration of improvement: 18 d |

| 2 | 69.1 | F | 13.5 | 134 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 25.7% | N | 1 | Y163L (31%) | — | 46, XX [20] | None | Normal cellularity | Stable disease at week 20 and week 52, and ANC showed a durable improvement from week 52 onward |

| 3 | 77.4 | M | 12.1 | 117 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 12% | N | 3 | N275I (60%) | ZRSR2 K98Nfs∗10 (27%) | 46, XY [20] | None | Hypercellularity (40%) | Week 20: ANC improvement from CTACE grade 3 to grade 2. Duration of improvement: 119 d. |

| 4 | 64.7 | M | 13.1 | 32 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 17.5% | Y | 2 | R1808∗ (15%) | SRSF2 P95L (43%) | 46, XY,del(20)(q11.2q13.3)[1]/46,XY[16] | Slight | Hypercellularity (—) | Week 20: Met fourth edition WHO criteria for CMML-1 |

| 5 | 73.7 | M | 13.6 | 72 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 11.8% | N | 3 | N1743I (51%) R1214W (16%) | SRSF2 P95R (40%) | 46, XY [20] | Moderate | Normal cellularity | Withdrew from the study due to PICC line thrombosis |

| 6 | 67.4 | M | 7.8 | 409 | 4.9 | 0.4 | 4.5% | N | 2 | L1447R (45%) | SRSF2 P95H (49.9%) | 46, XY [20] | Slight | Hypercellularity (—) | Stable disease at week 20 and week 52 |

| 8 | 77.3 | M | 12.8 | 172 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 25.5% | N | 3 | R250∗ (39%) | ASXL1 L732Yfs∗12 (39%); ZRSR2 Y347Tfs∗? (73%) | 46, XY [20] | Slight | Hypercellularity (60%) | Week 20: Progression to MDS-EB-1 |

| 9 | 79.0 | F | 14.8 | 39 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 22.9% | Y | 2 | C1378Lfs∗70 (39%) | SRSF2 P95H (28%) | 46, XX [20] | None | Hypercellularity (35%) | Stable disease at week 20 and week 52 |

| 10 | 64.9 | M | 12.1 | 100 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 38.9% | N | 3 | G259∗ c.3955-1G>A (39%) | ZRSR2 E49∗ (74%) | 45, X, –Y [20] | Slight | Hypercellularity (—) | Stable disease at week 20, with progression to MDS-EB-1 at week 52 |

(−) indicates the percentage of cellularity was not reported.

Both patients 4 and 9 had baseline AA levels of 0.2 mg/dL.

Although patients 2, 9, and 10 had AMC >0.5 × 109 per liter and <1.0 × 109 per liter, they did not meet CMML diagnostic criteria per the revised fourth edition of the WHO criteria (2016), which we used for inclusion criteria in this study. These criteria were revised in 2022 by the ICC and WHO, lowering the AMC threshold for CMML to ≥0.5 ×109 per liter. The high number of patients with monocytosis is likely due to the well-established mechanism(s) by which TET2 MTs, especially biallelic TET2 MTs or TET2/SRSF2 co-MTs, result in epigenetic dysregulation, clonal hematopoietic stem cell dominance, and monocytic lineage skewing (granulocyte-monocyte progenitor–biased hematopoiesis).16 Although patient 7 exhibited relative and absolute monocytosis, with WBC 13.7 × 109 per liter and TET2, SRSF2, and KRAS MTs, on bone marrow biopsy review, no bone marrow dysplasia/atypia was found, and this patient had a classical monocyte fraction (M01) <94% by monocyte repartitioning flow cytometry.17,18 The final diagnosis by the pathologist was TET2, SRSF2, and KRAS mutant CCUS; however, we excluded this patient from our analyses.

∗10 indicates that the frameshift leads to a premature stop codon 10 amino acids downstream from the mutation, causing the protein to be truncated early.

∗∗? indicates uncertainty about where the stop codon occurs after the frameshift.

AMC, absolute monocyte count; F, female; ICC, International Consensus Classification; M, male; N, no; WBC, white blood cell; WHO, World Health Organization; Y, yes.

At baseline, all patients had normal Hb, except patient 6 who was red blood transfusion dependent. Four patients (44%) had PLT <100 × 109 per liter, including 2 (patients 4 and 9) with PLT ≤50 × 109 per liter; 56% had ANC <1 × 109 per liter, including 2 (patients 8 and 10) with ANC <0.5 × 109 per liter.

IV AA was well tolerated, with the most common AEs being transient (resolved within 48 hours of completing therapy) polyuria (56%), and polydipsia (44%). Grade 1 constipation, headaches, and dyspepsia were reported in 2 patients (22%). One patient discontinued therapy after cycle 1 due to central line–associated thrombosis. No grade 3 or 4 treatment-related AEs or deaths occurred. No patients developed oxalate nephrolithiasis, a known complication of high-dose IV AA.19

The median follow-up duration was 31.6 months (range, 17.6-37). No significant differences in laboratory values (Hb, ANC, and PLT) or TET2MT VAF were observed at baseline, week 20, and week 52, as assessed by repeated measures analyses (supplemental Figures 2-4). Two patients (22%) acquired additional somatic MTs: patient 8 (RUNX1 p. Ser322∗) and patient 9 (CBL p. Cys384Arg and p. Thr406Asnfs∗26). VAF changes in other MTs are shown in supplemental Table 2.

At week 20, no responses were observed per International Working Group 2018 MDS response criteria. Three patients (33%; patients 4, 8, and 10) developed bona fide MN (2 MDS and 1 CMML). Two patients (patients 4 and 9) had baseline AA deficiency that normalized after therapy. Although patient 9 had stable disease at week 20, patient 4 progressed to CMML-1 at 52 weeks. No significant differences in clinical characteristics were found between stable and progressing patients (supplemental Table 1). All patients were alive at the last follow-up.

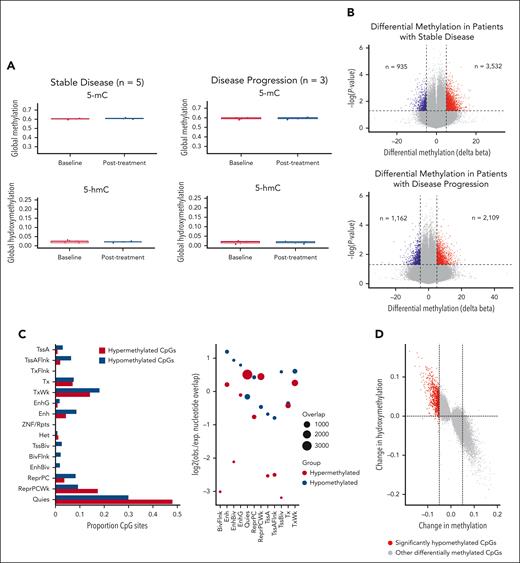

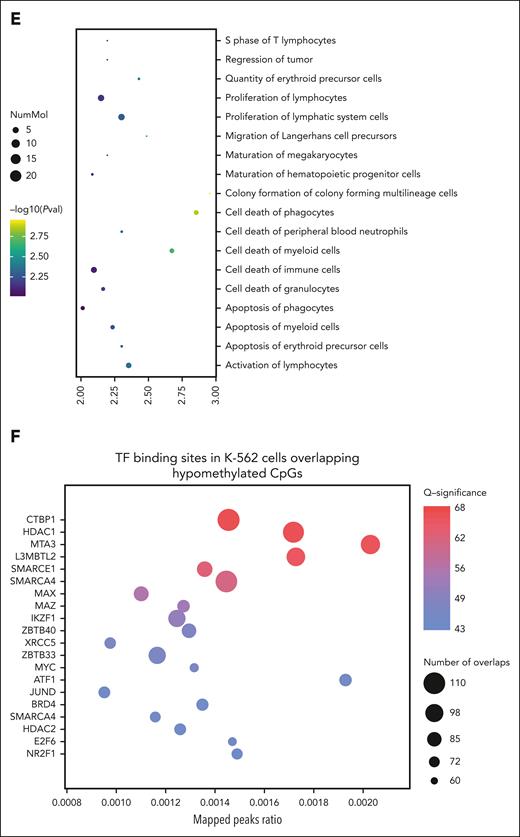

To quantify the impact of IV AA on TET activity, we profiled DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation in blood samples before and after treatment. Using the Illumina MethylationEPIC array paired with oxidative bisulfite treatment, we identified differentially methylated and hydroxymethylated regions. Initial analysis of global levels of 5 mC and 5 hydroxymethylcytosine before and after treatment across all patients revealed no significant differences (supplemental Figure 5). This finding persisted when patients were grouped by stable disease (n = 5) or disease progression (n = 3) (Figure 1A). However, given TET2's defined role at enhancer regions, global methylation averages may not fully capture its activity in TET2MT cases. Therefore, we next focused on site-specific methylation changes before (cycle 1, day 1 predose) and after treatment (end of cycle 3, postdose). Significant methylation changes were observed in both stable disease and disease progression groups (Figure 1B). Using peripheral blood mononuclear cells genome annotations from the Roadmap Epigenomics project,20 we examined whether AA treatment affected methylation at different genomic regions. In patients with stable disease, hypomethylated cytosine-phosphate-guanine sites (CpGs) were enriched at enhancer sites (enhancer [Enh]; bivalent enhancer [EnhBiv], and genic enhancer [EnhG]), whereas hypermethylated CpGs were enriched in quiescent and repressed regions (Quies and ReprPCWk; Figure 1C). This enhancer enrichment was absent in patients with disease progression (supplemental Figure 6). In stable disease patients, we integrated methylation changes with observed hydroxymethylation changes after treatment and found that hypomethylation correlated with increased hydroxymethylation (Figure 1D), suggesting these CpGs as potential targets of IV AA–enhanced TET activity.

DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation results. (A) Global methylation and hydroxymethylation at baseline and after treatment (week 12). No significant changes were observed in either the patients with stable disease or the patients who demonstrated disease progression. (B) Volcano plots showing methylation changes in patients with stable disease (n = 5) and patients with disease progression (n = 3). Cytosine-phosphate-guanine sites (CpGs) with delta beta >5% and P values < .05 were considered significant. (C) Bar chart showing the proportion of differentially methylated CpGs in chromatin states from peripheral blood mononuclear cells reference in patients with stable disease (n = 5). Genomic association tester was used to determine whether the proportion of CpGs in each chromatin state showed significant enrichment. Only the hypomethylated CpGs showed significant enrichment in Enh, EnhBiv, and EnhG regions. (D) Correlation of methylation changes with hydroxymethylation changes in patients with stable disease (n = 5). CpGs with P values < .05 were plotted to demonstrate the impact on both 5 mC and 5 hydroxymethylcytosine at that site. The CpGs highlighted in red are the 935 hypomethylated CpGs identified in panel B. (E) Diseases and functions associated with hypomethylated CpGs in patients with stable disease. Data were analyzed using ingenuity pathway analysis. (F) Overlap of hypomethylated CpGs in patients with stable disease with publicly available K-562 TF binding data using ReMapEnrich. Enh, enhancer; EnhBiv, bivalent enhancer; EnhG, genic enhancer; PVal, P value.

DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation results. (A) Global methylation and hydroxymethylation at baseline and after treatment (week 12). No significant changes were observed in either the patients with stable disease or the patients who demonstrated disease progression. (B) Volcano plots showing methylation changes in patients with stable disease (n = 5) and patients with disease progression (n = 3). Cytosine-phosphate-guanine sites (CpGs) with delta beta >5% and P values < .05 were considered significant. (C) Bar chart showing the proportion of differentially methylated CpGs in chromatin states from peripheral blood mononuclear cells reference in patients with stable disease (n = 5). Genomic association tester was used to determine whether the proportion of CpGs in each chromatin state showed significant enrichment. Only the hypomethylated CpGs showed significant enrichment in Enh, EnhBiv, and EnhG regions. (D) Correlation of methylation changes with hydroxymethylation changes in patients with stable disease (n = 5). CpGs with P values < .05 were plotted to demonstrate the impact on both 5 mC and 5 hydroxymethylcytosine at that site. The CpGs highlighted in red are the 935 hypomethylated CpGs identified in panel B. (E) Diseases and functions associated with hypomethylated CpGs in patients with stable disease. Data were analyzed using ingenuity pathway analysis. (F) Overlap of hypomethylated CpGs in patients with stable disease with publicly available K-562 TF binding data using ReMapEnrich. Enh, enhancer; EnhBiv, bivalent enhancer; EnhG, genic enhancer; PVal, P value.

Pathway analysis revealed that hypomethylated sites in patients with stable disease are involved in the development, function, and survival of HSPCs (Figure 1E). Previous studies suggest TET2MT could predispose to malignancy through methylation-driven disruption of transcription factor (TF) binding.21 To assess this, we overlapped the differentially methylated regions identified with chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing data from the K-562 cell line for 413 TF available through ReMap.22 This highlighted key TFs involved in HSPC differentiation and function, such as IKZF1 and MAZ, and others regulating transcriptional repression and chromatin remodeling, including CTBP1, HDAC1, SMARCA4, and SMARCE1 (Figure 1F).23,24 These findings suggest that, in select cases, IV AA may enhance TET activity to counteract methylation dysregulation at enhancer regions.

This study assessed single-agent high-dose IV AA in patients with TET2MT CCUS, demonstrating safety, while longitudinally monitoring for responses, including genetic and epigenomic changes. Although there were no clinical responses based on MDS criteria, the efficacy of high-dose IV AA may have been hindered by the clonal complexity of enrolled patients. Despite the absence of significant changes in TET2 mutational allele burdens over time, we observed an epigenetic impact on critical enhancer regions in HSPCs among patients with stable disease, likely due to augmented TET2/TET3 activity. These findings justify further investigation of IV AA, potentially in combination with other epigenetic agents.25 As a next step, we have initiated a pilot study (NCT03418038, Arm E), combining high-dose IV AA with standard-dose decitabine in patients with TET2MT CMML.

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their heartfelt gratitude to the patients who participated in this clinical trial. Their invaluable contribution and commitment to advancing medical knowledge have been instrumental in the progress of the clonal cytopenia(s) of undetermined significance research. Z.X. acknowledges training from the American Society of Hematology Clinical Research Training Institute.

This study was supported in part by the Predolin Foundation Biobank at Mayo Clinic and received the generous support of Mayo Clinic Philanthropy. M.M.P. acknowledges support from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (grant R01 CA272496-02) and SPORE (grant CA97274).

Authorship

Contribution: Z.X., M.M.P., and T.E.W. wrote the clinical trial protocol and led the clinical trial; Z.X. and B.R.L. led the data collection and analysis; Z.X. and M.M.P. contributed to the interpretation of results and wrote the first draft; T.L., C.F., and J.F. conducted the methylation analysis; M.A., A.A.M., N.G., and M.E. actively participated in patient recruitment; K.K.R. performed the immunohistochemistry stain; K.B.M. contributed to data collection; and all authors collaboratively drafted and revised the manuscript, bringing together their unique expertise to produce a cohesive and impactful contribution to this work.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: N.G. served on the advisory boards for Disc Medicine and Agios. M.M.P. has received research funding from Kura Oncology, Epigenetix, Polaris, Solu Therapeutics, and Stemline Therapeutics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mrinal M. Patnaik, Hematology Division, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St SW, Rochester, MN 55901; email: patnaik.mrinal@mayo.edu; and Zhuoer Xie, Department of Malignant Hematology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL 33612; email: zhuoer.xie@moffitt.org.

References

Author notes

Z.X. and J.F. are joint first authors.

All relevant clinical and methylation data can be made available on request from the corresponding authors, Zhuoer Xie (zhuoer.xie@moffitt.org) and Mrinal M. Patnaik (patnaik.mrinal@mayo.edu).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal