Truncating mutations in MS4A1 with subsequent antigen loss is a major mechanism of resistance to CD3 × CD20 bispecific antibodies.

Spatial heterogeneity and branching evolution underlie progression in lymphoma during CD19 and CD20 targeting immunotherapy.

Visual Abstract

CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells and CD20 targeting T-cell–engaging bispecific antibodies (bispecs) have been approved in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma lately, heralding a new clinical setting in which patients are treated with both approaches, sequentially. The aim of our study was to investigate the selective pressure of CD19- and CD20-directed therapy on the clonal architecture in lymphoma. Using a broad analytical pipeline on 28 longitudinally collected specimen from 7 patients, we identified truncating mutations in the gene encoding CD20 conferring antigen loss in 80% of patients relapsing from CD20 bispecs. Pronounced T-cell exhaustion was identified in cases with progressive disease and retained CD20 expression. We also confirmed CD19 loss after CAR T-cell therapy and reported the case of sequential CD19 and CD20 loss. We observed branching evolution with re-emergence of CD20+ subclones at later time points and spatial heterogeneity for CD20 expression in response to targeted therapy. Our results highlight immunotherapy as not only an evolutionary bottleneck selecting for antigen loss variants but also complex evolutionary pathways underlying disease progression from these novel therapies.

Introduction

T-cell–engaging bispecific antibodies (bispecs) targeting CD20 (encoded by MS4A1) have entered the therapy of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.1-4 As first in class, mosunetuzumab showed durable responses in relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma and was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration in patients after ≥2 lines of systemic therapy.5 Likewise, glofitamab and epcoritamab were approved for aggressive lymphoma in 2023.2,6 Now, these agents are even moving to frontline therapy, being evaluated in combination with established regimens.7 However, despite a significant proportion of long-lasting remissions, the majority of patients not achieving complete remission continue to relapse from CD20/CD3 bispec monotherapy for reasons that are yet to be determined.

CD19 is another B-cell antigen and target of a number of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell products or tafasitamab, an immunoglobulin G monoclonal antibody (mAb) approved in combination with lenalidomide in relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).8 As these novel approaches will become available and approved in similar therapeutic settings, a key challenge is how to sequence these agents to benefit the patient best. In this context, knowledge about resistance mechanisms will be important to inform clinical practice. Targeting single-surface molecules with T-cell–based therapies puts a strong selective pressure on the clonal architecture potentially selecting for antigen loss variants. CD19 loss was reported as a rare tumor escape mechanism in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and lymphoma relapsing from CAR T-cell therapy.9,10 Whether this holds true for CD20 and whether target loss is persistent at subsequent relapses are largely unknown. Similarly, the biological underpinnings of relapse with retained wild-type receptor expression and its impact on subsequent immunotherapies remain poorly understood.

To address these issues, we analyzed a unique set of patients being treated with CD20 bispecs, CD19 CAR T cells, and CD19 mAbs using a comprehensive multidimensional analytical pipeline. We show that the loss of CD20 protein expression is linked to genomic aberrations in the MS4A1 gene and that immunotherapy can be considered an evolutionary bottleneck selecting for antigen loss variants, whereas branching evolution and spatial heterogeneity can be observed.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the local ethics committee (reference no. 20220207_02). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before study enrollment.

Patient samples

Ultrasound-guided lymph node core biopsies were performed with a 14G PlusSpeed S System (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website).

Immunostaining on biopsy paraffin sections

CD79A, CD20, and CD19 protein expression was determined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) biopsy sections using monoclonal mouse anti–human antibodies (supplemental Table 1) according to standard procedures. Staining was evaluated by an expert pathologist (A.R.) to acquire qualitative labels of antigen expression (supplemental Table 1).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed as a part of the clinical workflow. For phenotypic analysis of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma cells CD45, CD22, CD19, CD20, CD10, and CD5 antibodies (supplemental Table 1) were used. Cells were analyzed using BD Biosciences fluorescence-activated cell sorting model Canto II (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo Software (Tree Star Inc).

Single-cell RNA sequencing processing

Single-cell suspensions from fresh biopsy samples were obtained by mincing in RPMI media and filtering through a cell strainer, followed by erythrocyte lysis, and loaded into the 10x Chromium controller at a concentration of 1000 cells per μL. Libraries were generated using the 3′ single-cell reagent v2 or v3 kit (10x Genomics; supplemental Table 3). Library quantification was performed (QubitTM 2.0, Thermo Fisher) and complementary DNA size distribution was checked (Bioanalyzer; HS DNA kit, Agilent) before sequencing using S2 flow cells on a NovaSeq6000 (Illumina). supplemental Table 3 lists all the libraries and their associated metrics.

scRNA-seq data analysis

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data were demultiplexed and mapped to GRCh38 using CellRanger (version 6.0.2; supplemental Table 3). SoupX (version 1.6.1) was used to remove ambient RNA signals.11 Downstream analyses, including normalization, scaling, quality filtering (supplemental Table 3), dimensional reduction, unsupervised Louvain clustering, and differential gene expression analysis were performed using the Seurat framework (version 4.1.1)12 in R (version 4.1.0). Batch variations in T-cell analyses were addressed using fastMNN batch-correction.13 Gene signature scores in single-cells were computed using the Seurat function AddModuleScore, with gene signatures summarized in supplemental Table 3. ProjecTILs was used for reference-based CD8 T-cell state prediction.14 Gene ontology–enrichment was performed using ClusterProfiler.15 Copy number variations (CNV) were inferred with infer-CNV.16 More details are provided in supplemental Methods.

Isolation of genomic DNA and total RNA from FFPE curls

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) and bulk RNA-seq was performed on unsorted biopsy FFPE samples on a germ line blood sample for each patient (supplemental Table 2). Genomic DNA and total RNA were isolated using the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen). Procedural details are provided in supplemental Methods.

Exome and transcriptome library construction and sequencing

WES library preparation was performed with the Twist Human Core Exome Kit + Twist human RefSeq Panel (Twist Biosciences), and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated on a NovaSeq6000 to a median mean calculated coverage of 146× (supplemental Table 2). Transcriptome library preparation was performed with the Illumina TruSeq RNA Exome technology and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated on a NovaSeq6000. Details are provided in supplemental Methods.

WES and bulk RNA-seq quality trimming

An initial quality assessment of all fastq-files was performed using FastQC (version 0.11.9). Low-quality reads and adapter sequences were trimmed with TrimGalore (version 0.6.4) powered by Cutadapt (version 2.8).17

WES data analysis

Trimmed reads were mapped to the human reference genome (hg19) using BWA (version 0.7.17)18 and sorted and indexed using Picard (version 2.25.0) and SAMtools (version 1.10),19 respectively. Duplicates were marked with Picard. Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) was used for base recalibration (version 4.0.9.0) and coverage calculations (version 3.8).20

Somatic substitutions and small indels were called with GATK-Mutect2 (version 4.1.9.0) VarScan (version 2.4.4),21 Strelka (version 2.9.2),22 and Scalpel (version 0.5.4)23 and inspected using Integrative Genomics Viewer (version 2.12).24 Variants were annotated with ANNOtate VARiation (ANNOVAR) (version 2019-10-24).25 LymphGen (version 2.0) classifier was used to assign DLBCL cases into genetic subgroups as proposed by Wright.26 Control-FREEC (version 11.6)27 and sequenza (version 3.0.0)28 were used to identify CNVs in tumor samples, with germ line for normalization. Additionally, sequenza was used for cellularity predictions. Subclonal structures were inferred as described previously,29 using SciClone (version 1.1.0).30 SciClone clusters were used for constructing mock phylogenetic trees. Details are provided in supplemental Methods.

RNA-seq data analysis

Spliced Transcript Alignment to a Reference (STAR) (version 2.7.6a)31 was used to map trimmed reads to GRCh37 (release 19). SAMtools (version 1.10) was used for sam-to-bam conversions, sorting, and indexing of the alignment-files. Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) were calculated with Cufflinks (version 2.2.1).32 Replicate multivariate analysis of transcript splicing (rMATS) (version 4.1.2)33 with the novelSS flag was used to identify alternative splicing events, and rmats2sashimiplot (https://github.com/Xinglab/rmats2sashimiplot/) was used to visualize the results. Arriba (version 2.1.0) was used for RNA-fusion detection with default settings.34

Statistical analysis

The nonparametric, 2-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare gene expression values or gene signature scores among groups of cells. The Student t test was used to compare means among groups of samples. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality. A P value < .05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

We selected 7 patients (Figure 1A; supplemental Table 1) who were heavily pretreated with a median number of 4 lines before CD20 bispecs (3-6) and CD19 CAR T cells (2-7), respectively. The number of patients relapsing from CD20- and CD19-directed immunotherapy was 5 and 5, respectively (Figure 1B). Three patients were treated with both, CD20- and CD19-targeted T-cell–redirecting therapies. Individual treatment history and sampling time points are shown in Figure 1A. We investigated lymphoma evolution and resistance mechanisms in 28 ultrasound-guided biopsies, applying scRNA-seq (supplemental Figure 1), bulk RNA-seq, WES, flow cytometry, and IHC. The analytical panel was adjusted in cases with a limited number of cells (Figure 1A; supplemental Table 1). For 2 patients we had access to paired biopsy samples obtained from distinct locations to investigate spatial differences (patients 1 and 3; Figure 1A; supplemental Table 1).

Treatment history and sampling of studied patients. (A) Twenty-eight samples from 7 patients treated with CD20 bispecs, CD19 CAR T cells, or both sequentially were obtained using ultrasound-guided biopsy. The samples were studied using a comprehensive analytical panel including scRNA-seq, bulk RNA-seq, WES, flow cytometry, and IHC. The analytical panel was adjusted according to the amount and quality of available material. The median of prior lines of therapy before CD20 bispecs and CD19 CAR T cells was 4 (range, 3-6) and 4 (range, 2-7), respectively. (B) Table indicating whether therapy relapse from CD19- and CD20-targeting T-cell–redirecting therapies or tafasitamab (CD19 mAb) was associated with antigen loss (antigen negative) or antigen retainment (antigen positive). Forward-slash indicates that a patient was not treated with the respective therapy or response was not assessable. Allo Tx, allogeneic stem cell transplantation; Auto Tx, autologous stem cell transplantation; BEAM, carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan; Benda, bendamustine; CHOEP, CHOP + etoposide; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; Cis, cisplatin; Dexa, dexamethasone; DHAP, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin; FCM, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone; GemOx, gemcitabine-oxaliplatin; HD, high-dose; ICE, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide; Ifo, ifosfamide; MTX, methotrexate; O, obinutuzumab; Pola, polatuzumab vedotin; Pred, prednisone; R, rituximab; Rev, lenalidomide (Revlimid); Tafa, tafasitamab; Vin, vincristine.

Treatment history and sampling of studied patients. (A) Twenty-eight samples from 7 patients treated with CD20 bispecs, CD19 CAR T cells, or both sequentially were obtained using ultrasound-guided biopsy. The samples were studied using a comprehensive analytical panel including scRNA-seq, bulk RNA-seq, WES, flow cytometry, and IHC. The analytical panel was adjusted according to the amount and quality of available material. The median of prior lines of therapy before CD20 bispecs and CD19 CAR T cells was 4 (range, 3-6) and 4 (range, 2-7), respectively. (B) Table indicating whether therapy relapse from CD19- and CD20-targeting T-cell–redirecting therapies or tafasitamab (CD19 mAb) was associated with antigen loss (antigen negative) or antigen retainment (antigen positive). Forward-slash indicates that a patient was not treated with the respective therapy or response was not assessable. Allo Tx, allogeneic stem cell transplantation; Auto Tx, autologous stem cell transplantation; BEAM, carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan; Benda, bendamustine; CHOEP, CHOP + etoposide; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; Cis, cisplatin; Dexa, dexamethasone; DHAP, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin; FCM, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone; GemOx, gemcitabine-oxaliplatin; HD, high-dose; ICE, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide; Ifo, ifosfamide; MTX, methotrexate; O, obinutuzumab; Pola, polatuzumab vedotin; Pred, prednisone; R, rituximab; Rev, lenalidomide (Revlimid); Tafa, tafasitamab; Vin, vincristine.

CD20 loss is caused by genomic aberrations

Antigen loss is a key immune escape mechanism.35 Thus, we focused on the 5 patients who relapsed from CD20 bispec therapy and determined CD20 expression status on IHC and/or flow cytometry. Indeed, 3 of them showed loss of CD20 expression at relapse (patients 1, 3, and 6), and 1 patient (2), who had CD20+ status at relapse, showed CD20 loss at a subsequent relapse (Figures 1B and 2A; supplemental Table 1).

WES and bulk RNA-seq reveal genomic mechanisms of CD20 loss. (A) CD79A and CD20 protein expression determined using IHC on FFPE biopsy sections. The images show staining from a lesion located to the left axilla of patient 3 obtained shortly after the start of CD20 bispec treatment (sample 3.1) and at relapse (sample 3.2), which is representative of the CD20⁻ relapses. (B) Schematic illustration showing CD20 loss was accompanied by genomic alterations, namely an RNA fusion between NHLRC3- NXT1P1 intergenic region and MS4A1 in patient 1 (positions refer to hg19), an intronic T>C mutation leading to cryptic splicing and frameshift in patient 2 (exon5:c.573+2T>C; allelic frequency, 82.10%-100%; tumor content, 80%), a nucleotide deletion with frameshift in patient 3 (exon3:c.212delT:p.M71Rfs∗12; allelic frequency, 16.60%-20.60%; tumor content, 80%), and a biallelic deletion of MS4A1 in patient 6.

WES and bulk RNA-seq reveal genomic mechanisms of CD20 loss. (A) CD79A and CD20 protein expression determined using IHC on FFPE biopsy sections. The images show staining from a lesion located to the left axilla of patient 3 obtained shortly after the start of CD20 bispec treatment (sample 3.1) and at relapse (sample 3.2), which is representative of the CD20⁻ relapses. (B) Schematic illustration showing CD20 loss was accompanied by genomic alterations, namely an RNA fusion between NHLRC3- NXT1P1 intergenic region and MS4A1 in patient 1 (positions refer to hg19), an intronic T>C mutation leading to cryptic splicing and frameshift in patient 2 (exon5:c.573+2T>C; allelic frequency, 82.10%-100%; tumor content, 80%), a nucleotide deletion with frameshift in patient 3 (exon3:c.212delT:p.M71Rfs∗12; allelic frequency, 16.60%-20.60%; tumor content, 80%), and a biallelic deletion of MS4A1 in patient 6.

To unravel the biological underpinnings of target loss, we performed WES and bulk RNA-seq of FFPE biopsy samples and detected somatic aberrations in the MS4A1 gene coding for CD20 in all patients with target loss (supplemental Table 2). These included an RNA-fusion, cryptic splicing, frameshift, or biallelic deletion (Figure 2B), as suggested by somatic CNVs in the tumor normalized to germ line WES (supplemental Figure 2).

In detail, the RNA-fusion event in patient 1 generated a novel transcript encompassing only exons 6 and 7 of MS4A1, thereby inducing CD20 loss (Figure 2B; supplemental Table 2). The clonal cryptic splicing event in patient 2 was caused by an intronic splice site mutation and resulted in retention of 13 intronic nucleotides after exon 5, ultimately inducing frameshift (supplemental Figure 3). This event was biallelic because of a concomitant chromosomal deletion from 11q12.1 to 11q21.2 at the other allele (supplemental Table 2). In contrast, the frameshift deletion in patient 3 was subclonal and monoallelic (supplemental Table 2), and we did not identify mechanisms conferring CD20 loss in other subclones in this patient. Both the cryptic splicing in patient 2 and the deletion-induced frameshifts in patient 3 were located in regions coding for transmembrane domains of CD20 (Figure 2B). In patient 6, we found a deletion of 11q and an additional focal homozygous deletion affecting the second allele of MS4A1, resulting in a clonal biallelic event. In line, scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq confirmed loss of MS4A1 expression in this patient (supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

In summary, our results show a link between genomic aberrations of CD20 and immune escape in our set of patients.

Association of CD20+ relapse with exhaustion of T cells

Two patients (2 and 7) relapsed with retained CD20 expression on IHC and flow cytometry during bispec therapy (Figure 3A). Of note, in these patients, no in-frame deletions or nontruncating mutations that could potentially compromise CD20 bispec efficacy were identified for MS4A1. Potential isoforms could be ruled out in patient 2.

Exhausted effector T cells in patients with CD20+ relapse from CD20 bispecs. (A) CD79A and CD20 protein expression determined using IHC on FFPE biopsy sections. The images show staining from patient 2 before CD20 bispec treatment (sample 2.1) and at relapse (sample 2.4), demonstrating relapse with retained CD20. (B) Schematic illustration showing the strategy used to compare scRNA-seq T cells from samples obtained during CD20 bispec treatment, including tumor-free or responsive lesions (n = 2, sample 3.3 and 7.1), CD20⁻ relapse (n = 1, sample 3.2) and CD20+ relapse (n = 3; sample 2.4, 2.5, and 7.2). T cells were combined into a joint embedding, and exhaustion was interrogated based on an established exhaustion gene signature within CD8 subpopulations. The exhaustion scores within CD8 effector T cells were compared between patients who experienced CD20+ relapse (patients 2 and 7) and the patient who did not experience CD20+ relapse (patient 3). (C) Joint UMAP embedding of 6381 T cells from 6 samples. T cells are color-coded based on identified subpopulation. (D) Heat map showing T-cell subset and state gene signature scores across subpopulations, underlying the subpopulation annotation in panel C. (E) Cells are color-coded based on their exhaustion signature score, which was computed across CD8 subpopulations. The gene list underlying the exhaustion score can be found in supplemental Table 3. (F) Box plot depicting the exhaustion scores within CD8 effector T cells across samples. Statistical significance was assessed using a pairwise, 2-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test against combined samples 3.2 and 3.3 (∗∗∗P < 2.22 × 10⁻16). Center line indicates the median, box limits indicate the upper and lower quantiles, and whiskers indicate the 1.5× interquartile range. (G) Bar plot demonstrating proportions of T-cell subpopulations across samples. eff, effector; IFN, interferon; NK, natural killer; NKT, natural killer T cell; Tfh, T follicular helper; Th, T helper; Treg, regulatory T cell; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

Exhausted effector T cells in patients with CD20+ relapse from CD20 bispecs. (A) CD79A and CD20 protein expression determined using IHC on FFPE biopsy sections. The images show staining from patient 2 before CD20 bispec treatment (sample 2.1) and at relapse (sample 2.4), demonstrating relapse with retained CD20. (B) Schematic illustration showing the strategy used to compare scRNA-seq T cells from samples obtained during CD20 bispec treatment, including tumor-free or responsive lesions (n = 2, sample 3.3 and 7.1), CD20⁻ relapse (n = 1, sample 3.2) and CD20+ relapse (n = 3; sample 2.4, 2.5, and 7.2). T cells were combined into a joint embedding, and exhaustion was interrogated based on an established exhaustion gene signature within CD8 subpopulations. The exhaustion scores within CD8 effector T cells were compared between patients who experienced CD20+ relapse (patients 2 and 7) and the patient who did not experience CD20+ relapse (patient 3). (C) Joint UMAP embedding of 6381 T cells from 6 samples. T cells are color-coded based on identified subpopulation. (D) Heat map showing T-cell subset and state gene signature scores across subpopulations, underlying the subpopulation annotation in panel C. (E) Cells are color-coded based on their exhaustion signature score, which was computed across CD8 subpopulations. The gene list underlying the exhaustion score can be found in supplemental Table 3. (F) Box plot depicting the exhaustion scores within CD8 effector T cells across samples. Statistical significance was assessed using a pairwise, 2-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test against combined samples 3.2 and 3.3 (∗∗∗P < 2.22 × 10⁻16). Center line indicates the median, box limits indicate the upper and lower quantiles, and whiskers indicate the 1.5× interquartile range. (G) Bar plot demonstrating proportions of T-cell subpopulations across samples. eff, effector; IFN, interferon; NK, natural killer; NKT, natural killer T cell; Tfh, T follicular helper; Th, T helper; Treg, regulatory T cell; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

With the hypothesis that deficits in the T-cell effector compartment contributed to relapse in these cases, we undertook a focused analysis of T cells. First, we integrated scRNA-seq data of all lymph node biopsies acquired during CD20 bispec therapy with sufficient numbers of T cells representing CD20+ relapse lesions (n = 3; samples 2.4, 2.5, and 7.2), CD20⁻ relapse lesions (n = 1; sample 3.2), and tumor-free or responding lesions (n = 2; samples 3.3 and 7.1; Figure 3B). We identified 9 T-cell subpopulations defined by expression of T-cell subset and state gene signatures (Figure 3C-D; supplemental Table 3). An established exhaustion gene signature,36 including PDCD1 (PD-1), HAVCR2 (TIM-3), and LAG3 among others, was used to interrogate the functional state of CD8+ T-cell subpopulations (supplemental Table 3). Overall, we observed the highest exhaustion scores within the CD8 effector T cells (Figure 3E; supplemental Figure 4A).

In line with our hypothesis, the exhaustion signature scored significantly higher in CD8 effector T cells from samples of the 2 patients with CD20+ relapse (patients 2 and 7) than in samples from the patient without CD20+ relapse (patient 3; Figure 3F; supplemental Figure 4B; P < 2.22 × 10⁻16, 2-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test). Likewise, we found that the exhaustion scores in CD20+ relapse samples were significantly higher than that in bone marrow–derived CD8 effector T cells from patients with multiple myeloma during B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) bispec therapy (data set from Friedrich et al37; supplemental Figure 5). In the same patients, we noted high abundances of CD8 effector T cells, supporting expansion and subsequent exhaustion of CD8 effector T cells (Figure 3G). Of note, presence of terminally exhausted CD8 T cells in the patients with CD20+ relapse was validated by interrogating our data with the ProjecTILs framework for reference-based T-cell state prediction (supplemental Figure 6).14 These findings are consistent with an association between expanded and exhausted CD8 effector T cells and relapse in patients with retained CD20 expression.

Frequency and mechanism of CD19 loss

Resistance to CD19-directed immunotherapies has been intensively studied lately,10,38-42 with conflicting results on the frequency and mechanism of target loss, which will be discussed later in more detail (see “Discussion”). In our set, 2 out of 4 patients showed CD19 loss (patients 1 and 4) after respective CAR T-cell therapy on IHC and flow cytometry (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 7A-B). Similarly, scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq showed lack of CD19 expression in these cases (supplemental Table 1). WES was available for 1 of them without revealing single nucleotide variants or structural aberrations affecting CD19, ultimately suggesting epigenetic remodeling or transcriptomic adaptation.43 We interrogated T-cell exhaustion in patients with CD19+ relapse (patients 2 and 5; Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 7C-D) using scRNA-seq data. Exhaustion markers were highly expressed in CD8 effector T cells of 1 patient (patient 5, sample 5.1; supplemental Figure 8), whereas T-cell numbers were insufficient for analysis in the other patient (patient 2; sample 2.7). Together, we confirmed loss of CD19 expression at both protein and transcriptome level but were not able to fully describe the biologic mechanism of CD19 loss despite our comprehensive analytical approach. In the patient who progressed from CD19 mAb, we did not observe target loss.

Longitudinal evolution of antigen loss under sequential T-cell–redirecting therapy

Immunotherapy can be considered as an evolutionary bottleneck selecting for resistance variants, and a prime example for this assumption was patient 1. This 68-year-old male responded well to CD19 CAR T-cell therapy but relapsed with a CD19⁻ clone 2 months after CAR T-cell infusion. The patient was salvaged with CD20 bispecs, achieving partial remission and eventually relapsed with CD19/CD20 double-negative disease, in line with linear evolution and 2 evolutionary bottlenecks (Figure 4A-B; also see the visual abstract in the online version of this article).

Sequential CD19 and CD20 loss and branching evolution in lymphoma under the pressure of T-cell–redirecting immunotherapy. (A) Schematic timeline of the treatment history and sampling from patient 1 around the 4 sampling time points. Samples 1.2 and 1.4 were both obtained from a lymph node lesion at the left clavicula during CD20 bispecs and 80 days later, respectively. (B) CD79A, CD19, and CD20 protein expression determined using IHC on FFPE biopsy sections of sample 1.2 showing CD19/CD20 double-negative tumor after CD19 CAR T and CD20 bispec treatment, demonstrating sequential antigen loss. (C) Log-normalized MS4A1 expression color-coded and projected on the UMAP representation of sample 1.4 B cells/malignant cells demonstrates the recurrence of MS4A1-positive cells at a single-cell transcriptomic level. (D) Bar plot showing the proportion of MS4A1 expressing cells, determined by at least 1 count of MS4A1. (E) CD79A and CD20 protein expression determined using IHC on FFPE biopsy sections of sample 1.4 with a partially positive CD20 stain, validating CD20 recurrence on protein level. (F) Schematic timeline of the treatment history and sampling of patient 2 around the 4 sampling time points of samples that were subjected to WES (2.2, 2.4 or 2.5, 2.7, and 2.8). Sample ID, site, CD19 status, and CD20 status are indicated. (G) Mock phylogenetic tree constructed from SciClone clusters (indicated by colors) based on WES. The number at the start edge indicates the number of aberrations in the most recent common ancestor, and numbers on branches indicate the amount of acquired mutations. Length of branches does not indicate the extent of differences between subclones. Samples corresponding to subclone branches are indicated; see supplemental Figure 10 for details. IN, inguinal.

Sequential CD19 and CD20 loss and branching evolution in lymphoma under the pressure of T-cell–redirecting immunotherapy. (A) Schematic timeline of the treatment history and sampling from patient 1 around the 4 sampling time points. Samples 1.2 and 1.4 were both obtained from a lymph node lesion at the left clavicula during CD20 bispecs and 80 days later, respectively. (B) CD79A, CD19, and CD20 protein expression determined using IHC on FFPE biopsy sections of sample 1.2 showing CD19/CD20 double-negative tumor after CD19 CAR T and CD20 bispec treatment, demonstrating sequential antigen loss. (C) Log-normalized MS4A1 expression color-coded and projected on the UMAP representation of sample 1.4 B cells/malignant cells demonstrates the recurrence of MS4A1-positive cells at a single-cell transcriptomic level. (D) Bar plot showing the proportion of MS4A1 expressing cells, determined by at least 1 count of MS4A1. (E) CD79A and CD20 protein expression determined using IHC on FFPE biopsy sections of sample 1.4 with a partially positive CD20 stain, validating CD20 recurrence on protein level. (F) Schematic timeline of the treatment history and sampling of patient 2 around the 4 sampling time points of samples that were subjected to WES (2.2, 2.4 or 2.5, 2.7, and 2.8). Sample ID, site, CD19 status, and CD20 status are indicated. (G) Mock phylogenetic tree constructed from SciClone clusters (indicated by colors) based on WES. The number at the start edge indicates the number of aberrations in the most recent common ancestor, and numbers on branches indicate the amount of acquired mutations. Length of branches does not indicate the extent of differences between subclones. Samples corresponding to subclone branches are indicated; see supplemental Figure 10 for details. IN, inguinal.

In this context, a key question is whether antigen loss is persistent at subsequent relapses because it would be anticipated in cases with clonal antigen loss caused by genomic aberrations. To address this question, we analyzed another sample collected after 8 weeks of further chemotherapy with bendamustine (Figure 4A). Indeed, relapse was dominated by a CD20⁻ clone, yet scRNA-seq and IHC detected a CD20+ subclone with a cancer-cell fraction of ∼7% (Figure 4C-E). Identification of widespread CNVs on scRNA-seq data validated MS4A1-expressing cells as malignant (supplemental Figure 9A). Obviously, this subclone has survived treatment and started to proliferate in the absence of CD20 bispec immunotherapy. Interestingly, the MS4A1-positive cells showed upregulation of genes associated with energy metabolism and a higher proportion of cells actively cycling than their MS4A1-negative counterparts, suggesting a fitness advantage (supplemental Figure 9B-D; supplemental Table 4). Of note, the size of the subclone was too small to call subclone-specific mutations using WES; thus, we cannot exclude a distinct mutational profile driving this fitness advantage.

An even more winding path of branching evolution was observed in patient 2, who progressed from CD20 bispecs with retained CD20 expression and was then salvaged with CD19 CAR T cells, to which he responded with complete metabolic response for 3 months. At relapse, however, a CD20-negative clone (sic) was detected using scRNA-seq and IHC while CD19 was still expressed (Figure 4F, supplemental Table 1). Using SciClone, we reconstructed a phylogenetic tree for subclones from patient 2, which showed 4 branches including the MS4A1-loss variant in the post–CD20-loss samples (Figure 4G;, supplemental Figure 10). These findings can be interpreted as the existence of substantial hidden subclonal diversity, including CD20 loss variants providing the fuel for relapse. Both cases highlight branching evolution to be active in lymphoma under the pressure of immunotherapy.

Spatial heterogeneity and mixed response

Current knowledge on spatial heterogeneity in lymphoma and its impact on immunotherapy is scarce. For 2 patients (patients 1 and 3), we had access to paired biopsy samples from distinct locations and leveraged the opportunity to study spatial heterogeneity in more detail. Patient 1 showed progression from CD20 bispecs, and 2 lymph nodes were biopsied. In the first lymph node located to the left clavicle (sample 1.2), results of both IHC and flow cytometry analyses showed complete loss of CD20 expression, whereas in a second cervical lesion (sample 1.3), approximately half of the tumor cells still expressed CD20 (supplemental Figure 11). Except for MS4A1 expression, only minor differences could be found using differential gene expression analysis between CD20+ and CD20⁻ tumor cells in the cervical lesion, mainly related to ribosomal gene expression and cytoplasmic translation (supplemental Figure 12; supplemental Table 4).

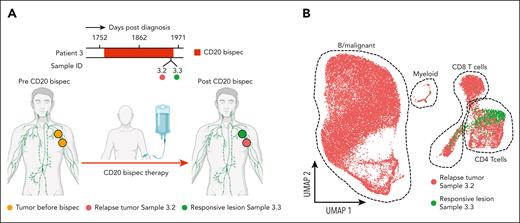

In patient 3, 2 neighboring lesions were biopsied, with one of them progressing in size and the other shrinking during CD20 bispec therapy (Figure 5A). Our scRNA-seq results showed no remaining tumor or B cells in the responding lesion, which was confirmed using IHC. The cellularity of this responding lymph node was mainly composed of CD4 T cells with smaller CD8 T-cell (CD4/CD8 ratio = 3.85) and myeloid compartments. In contrast, the relapse lesion consisted mainly of tumor cells that lacked CD20 expression on IHC and flow cytometry (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 13; supplemental Table 1).

Spatial heterogeneity of CD20 loss. (A) Schematic illustration showing the spatial response heterogeneity in patient 3 to CD20-targeted bispec therapy. (B) UMAP representation of single-cell transcriptomes (25 824 cells) from samples 3.2 and 3.3 colored by sample. Dashed outlines delineate cell type clusters. The schematic was partially created using BioRender.com.

Spatial heterogeneity of CD20 loss. (A) Schematic illustration showing the spatial response heterogeneity in patient 3 to CD20-targeted bispec therapy. (B) UMAP representation of single-cell transcriptomes (25 824 cells) from samples 3.2 and 3.3 colored by sample. Dashed outlines delineate cell type clusters. The schematic was partially created using BioRender.com.

We believe these 2 cases highlight the presence of spatial heterogeneity affecting target expression in lymphoma. They also underscore the limitations of studying evolutionary processes in cancer when only a limited set of biopsies is available.

Discussion

The selective pressure of novel immunotherapies on the clonal architecture in lymphoma is poorly understood. Here, we described a genomic mechanism of CD20 loss in patients treated with anti-CD20 bispecs. WES and bulk RNA-seq revealed a variety of genomic aberrations encompassing the MS4A1 gene in all 4 patients who relapsed with CD20-loss variants. Our concordant results suggest a major mechanism of relapse in our patient set; however, we fully appreciate that a larger study is warranted to determine the exact frequency of CD20-loss relapses in this setting. In this context, correlative data on mosunetuzumab were presented at the 2022 American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting and showed CD20 loss in 27% of patients at the time of disease progression.44 In detail, the authors investigated a large set of 62 patients with predose and/or postdose biopsy samples, including 55 patients with sequential biopsies (7 with predose biopsies; 26 with predose and on-treatment biopsies; 5 with predose, on-treatment, and at-progression biopsies; 24 with predose and at-progression biopsies). In line with our study, 20 different MS4A1 mutations were identified by WES in 14 patients, 6 of whom were associated with loss of CD20 expression, and the other were found at earlier time points, such as at baseline.

Antigen loss can be considered the ultimate adaptation of a cancer cell to targeted immunotherapy. However, intact receptor expression may be necessary for sustained viability, whereas its loss could lead to decreased clonal fitness or even apoptosis. Interestingly, the biological function of CD20 in B cells, if any, has yet to be elucidated.45 Germ line mutations in the MS4A1 gene with subsequent loss of CD20 expression exhibit only minor effects on humoral immunity and B-cell proliferation in humans and mice.45-47 As a general rule, receptors with only minor physiological significance are more prone to be lost than essential antigens. CD19 loss has been described in DLBCL and B-cell ALL with a frequency of 7% to 25%.9,48-50 Taking our results on genomically driven antigen loss into perspective, we observe a similar pattern in multiple myeloma, in which GPRC5D loss is rather common, whereas biallelic events causing loss of BCMA represent a rare mechanism of resistance to T-cell–redirecting therapies.51-54 Similar to CD20, the function of GPRC5D is unknown, whereas BCMA plays a crucial role in plasma cell survival, being the receptor for a proliferation-inducing ligand and B-cell activiating factor, involved in NF-κB signaling.55

An unsolved question is the level of tumor antigen expression being necessary for successful killing by CAR T cell or bispec. In the ZUMA-1 and JULIET trials, similar response rates were observed in patients with and without baseline CD19 expression on IHC and flow cytometry.48,56 Using single molecule microscopy, Nerreter et al showed that CD19 CAR T cells were able to eliminate malignant cells in vitro that express <100 CD19 molecules on their surface, a number that is below the limit of detection of IHC or flow cytometry.57 Wild-type receptor expression below the limit of detection of standard diagnostics could serve as an explanation for CAR T-cell responses in patients with “CD19-negative disease” at baseline. These observations suggest a potential limitation of using CD19 detection using IHC or flow cytometry as the only criterion for true CD19 negativity. The patients in our study developed CD19 loss at relapse from CAR T-cell therapy and antigen loss was confirmed because of lacking CD19 RNA expression. Future studies incorporating transcriptomics in the work-up of antigen loss are warranted. In this context, a recent study reported CD20 downregulation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia via alternative splicing in the messenger RNA 5′-untranslated region, which generates an extended 5′-untranslated region isoform that cooperatively inhibits translation. This mechanism of resistance was also observed in follicular lymphoma cases with CD20 negativity at relapse after mosunetuzumab.58 Last but not least, tumor-intrinsic factors, such as complex structural variants or apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide mutational signatures associated with genomic instability, also contributed to relapse from CD19 CAR T-cell therapy in another study.10

We also described a tumor-extrinsic factor contributing to CD20 bispec resistance. Patients relapsing with retained antigen expression showed highly expanded yet exhausted T cells in their tumor microenvironment, in line with deficits in their effector cell compartment. In an elegant study, dysfunctional hyperexpanded T-cell clonotypes were linked to resistance to bispecs.37 Treatment-free intervals reinvigorate exhausted T cells in another study on bispecs.59 T-cell exhaustion was also found in B-cell ALL tumors with impaired death receptor signaling.60 We previously reported on the role of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells in B-precursor ALL and their negative impact on outcomes in patients treated with CD19 bispecs.61 It is important to note that T-cell exhaustion is a physiological process, for example, arising from chronic stimulation. Thus, T-cell exhaustion could still be associated with tumor-intrinsic or microenvironmental stimuli, which we were not able to capture in our study. We cannot fully solve the chicken-and-egg problem with T-cell exhaustion and progression from immunotherapy.

Embarking on the clinical consequences, the high rate of antigen loss including sequential loss-of-tumor surface antigens argues for repeated tissue evaluation if retreatment is considered.62 In this context, Yu et al63 reported on a pediatric patient with primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma who experienced transient CD20 and CD30 downregulation after rituximab and brentuximab, and persistent CD19 loss after CAR T-cell therapy in longitudinally collected tumor biopsy samples.63 Spatial heterogeneity, however, poses a challenge to such evaluations because a given tissue sample may not be representative for the entire tumor. The branching evolutionary pathways we described herein point out to a substantial amount of clonal diversity existing in our patients which cannot be captured by biopsies only. Assessing circulating tumor cells in the peripheral blood or radiomic approaches will be necessary to adjust for spatial differences in future efforts.64-66 Overcoming antigen loss will increase efficacy of novel T-cell–based immunotherapies and multitargeted approaches, such as bispecific CD20/CD19 or CD19/CD22 CAR T cells, which are being investigated in several trials.67,68

The major limitation of our study is the number of only 7 patients, precluding defining the exact frequency or the full spectrum of resistance mechanism to CD19 and CD20 immunotherapies. A larger data set is also warranted to address the question whether some of the recently proposed DLBCL molecular subgroups26,69 are more prone to antigen loss than other subgroups. Although we used fresh material for scRNA-seq and flow cytometry, WES and bulk RNA-seq were performed on paraffin-embedded tissues, limiting copy number analysis and subsequent clonality estimation. A strength of our study, however, was a significant number of paired and longitudinally collected samples, which allowed us to study the spatiotemporal evolution of lymphoma during T-cell–redirecting immunotherapy. Thus, our set of samples is rare because repeated tissue evaluation is not often performed in the clinical routine. Although we expect a growing number of patients being treated with sequential CD19 and CD20 therapies, we agree that future studies are warranted to further validate our observations.

In conclusion, our study sheds light on the evolutionary processes underlying resistance to novel T-cell–based immunotherapies in lymphoma. The branching evolutionary pathways that we have observed make it difficult to predict antigen expression status at relapse, emphasizing the need for serial antigen testing in the clinical routine. Whether we need transcriptomics and DNA data in addition to IHC and flow cytometry to confirm antigen negativity, is yet to be determined. The link between genomic aberrations and CD20 antigen loss as well as our observation on sequential losses of CD19 and CD20 will foster the development of multitargeted approaches.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study.

A.M.L., F.I., A-E.S., and L.R. thank the Single Cell Center Würzburg for support. A.M.L. and A.-E.S. acknowledge National Institutes of Health, National Human Genome Research Institute grant 1R01HG011868-02. A.M.L., A.-E.S., and L.R. thank the Else Kröner Forschungskolleg Twinsight for support. A.M.L. and A.-E.S. are supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) via the SFB DECIDE (Z02 project). A.-E.S. and O.D. are supported by the DFG GRK2157. L.R. was supported by the German Cancer Aid via the MSNZ program, the BMBF (TissueNET), and the Paula and Rodger Riney Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: J.D., A.M.L., A.-E.S., and L.R. contributed to study design; J.D., V.F., H.R.-W., M.D.V., F.E., N.A., L.G., H.E., A.R., and M.S.T. provided study material or patients; V.F., H.R.-W., and A.R. performed immunostainings; A.R. interpreted immunostainings; J.D. performed ultrasound-guided biopsies; J.D. and F.E. performed flow cytometry and J.D. interpreted flow cytometry; O.D., C.T., F.I., and A.-E.S. performed scRNA-seq; A.M.L. performed scRNA-seq data analysis; S.A. and N.W. performed WES data analysis, and S.A. performed bulk RNA-seq data analysis; A.M.L. conceived the figures with input from J.D., S.A., A.-E.S., and L.R.; A.M.L. and L.R. wrote the manuscript with input from J.D., S.A., and A.-E.S.; and all authors approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.D. has received research support from Regeneron and Incyte, and has received honoraria from Incyte and MorphoSys. H.E. has participated in scientific advisory boards for Janssen, Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb, Amgen, Novartis, and Takeda; has received research support from Janssen, Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb, Amgen, and Novartis; and has received honoraria from Janssen, Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb, Amgen, Novartis, and Takeda. L.R. received honoraria from Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, and research support from Skyline Dx. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Leo Rasche, Department of Internal Medicine 2, University Hospital Würzburg, Oberdürrbacherstr 6, 97080 Würzburg, Germany; email: rasche_l@ukw.de; and Antoine-Emmanuel Saliba, Institute of Molecular Infection Biology, University of Würzburg, Helmholtz Institute for RNA-based Infection Research, Josef-Schneider-Str 2, 97080 Würzburg, Germany; email: emmanuel.saliba@helmholtz-hiri.de.

References

Author notes

J.D. and A.M.L. contributed equally to this work.

scRNA-seq, bulk RNA-seq, and WES data generated in this study are deposited at European Genome-Phenome-Archive (study ID EGAS00001006133).

R code used for analysis of scRNA-seq data have been deposited in GitHub at https://github.com/saliba-lab/Lymphoma-CD20bispec-resistance.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal