CD19-directed CAR T and time-limited ibrutinib are a deliverable and effective combination in relapsed/refractory MCL.

Novel combination therapy may overcome negative clinical and molecular features, including BTKi refractoriness and TP53 mutation.

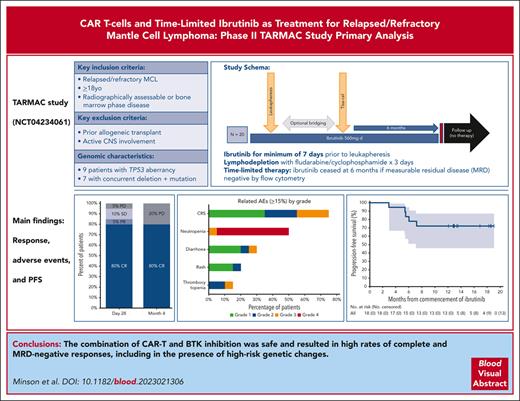

Visual Abstract

CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-T) achieve high response rates in patients with relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). However, their use is associated with significant toxicity, relapse concern, and unclear broad tractability. Preclinical and clinical data support a beneficial synergistic effect of ibrutinib on apheresis product fitness, CAR-T expansion, and toxicity. We evaluated the combination of time-limited ibrutinib and CTL019 CAR-T in 20 patients with MCL in the phase 2 TARMAC study. Ibrutinib commenced before leukapheresis and continued through CAR-T manufacture for a minimum of 6 months after CAR-T administration. The median prior lines of therapy was 2; 50% of patients were previously exposed to a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi). The primary end point was 4-month postinfusion complete response (CR) rate, and secondary end points included safety and subgroup analysis based on TP53 aberrancy. The primary end point was met; 80% of patients demonstrated CR, with 70% and 40% demonstrating measurable residual disease negativity by flow cytometry and molecular methods, respectively. At 13-month median follow-up, the estimated 12-month progression-free survival was 75% and overall survival 100%. Fifteen patients (75%) developed cytokine release syndrome; 12 (55%) with grade 1 to 2 and 3 (20%) with grade 3. Reversible grade 1 to 2 neurotoxicity was observed in 2 patients (10%). Efficacy was preserved irrespective of prior BTKi exposure or TP53 mutation. Deep responses correlated with robust CAR-T expansion and a less exhausted baseline T-cell phenotype. Overall, the safety and efficacy of the combination of BTKi and T-cell redirecting immunotherapy appears promising and merits further exploration. This trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT04234061.

Introduction

Therapeutic advances in the treatment of relapsed/refractory (R/R) mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) have led to markedly improved outcomes compared to that achieved with repeated exposure to cytotoxic chemotherapy.1 Covalent Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi) are widely accepted as a second-line therapy, are highly active in the majority of patients, and several are now approved for use.2-4 However, as a class, their clinical efficacy is typically limited in duration to a median of 1 to 3 years, and they result in relatively low rates of measurable residual disease (MRD) negativity, which is established as a strong predictor of subsequent relapse.5,6 Furthermore, they are less effective in patients with high-risk disease features, such as TP53 aberrancy or blastoid morphology.7-12 The chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) products brexucabtagene autoleucel and lisocabtagene maraleucel have efficacy in patients with R/R MCL, including biologically high-risk disease,13 and present significant appeal as a time-limited, once-off treatment. However, broad application of CAR-T can be limited by the kinetics of relapse after BTKi failure,7 which may lead to progression during manufacturing, significant rates of observed toxicity, including cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity, and considerable rates of disease relapse after infusion.14,15 The 4-1BB–stimulated CD19-directed CAR-T product tisagenlecleucel has not been extensively tested in MCL but has demonstrated prolonged responses in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and is associated with lower rates of adverse events, particularly neurotoxicity.16,17

The combination of ibrutinib and CAR-T can be safely administered in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and in this context, it is associated with a number of hypothesized advantages.18,19 Ibrutinib has positive effects on T-cell fitness, including the potential to reverse T-cell exhaustion and overcome senescence,20-22 and results in improved CAR T-cell expansion in vivo.18,23 The effects of ibrutinib after infusion of CAR T cells may also contribute to lower severity of important adverse events, most significantly CRS.18 Given the sensitivity of MCL to both BTKi and CAR T-cell therapy, there is a rationale to test the combination in this population. In light of the prolonged responses seen in CAR-T monotherapy and the benefits of fixed-course therapy, there is appeal in the concept of MRD-directed treatment withdrawal in patients with disease responding deeply to the combination. We therefore conducted a phase 1/2 investigator-initiated study of time-limited ibrutinib combined with CTL019 (the investigational form of tisagenlecleucel) in R/R MCL.

Methods

Patient selection and study design

We included patients with radiologically or histologically detectable R/R MCL after ≥1 prior line of therapy, which could include a BTKi. Key exclusions included prior allogeneic stem cell transplantation, prior CAR-T therapy, or active central nervous system lymphoma. Full eligibility criteria are contained in the supplemental Materials (available on the Blood website). Histology was confirmed centrally, and diagnosis required evidence of typical histology and immunophenotype, with or without evidence of IGH::CCND1 fusion by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). All patients provided written informed consent; the study was approved by the hospital Human Research Ethics Committee and performed according to the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (ICHGCP). The study was sponsored by the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and was conducted at 3 sites in Australia.

Patients received ibrutinib 560 mg daily with appropriate dose reduction for toxicity: those on ibrutinib at the time of study entry continued treatment. Ibrutinib was given for a minimum of 7 days before leukapheresis and continued throughout CAR-T manufacturing, lymphodepletion, and after CAR-T infusion. Platelet transfusion was provided in the event of central line placement without ibrutinib cessation. Additional bridging therapy was delivered at the discretion of the treating physician. Lymphodepletion was administered for all patients and consisted of fludarabine 25 mg/m2 and cyclophosphamide 250 mg/m2 each daily for 3 days, followed 2 to 5 days later by a single dose of autologous CTL019 (the investigational form of tisagenlecleucel) at a dose between 0.6 × 108 and 6.0 × 108 CAR+ cells. Patients were monitored for at least 4 hours after infusion, with further hospitalization at investigator discretion. Owing to the experience of fatal arrhythmia during CRS in another trial of patients receiving ibrutinib and CAR T cells,18 interruption of ibrutinib and continuous cardiac telemetry and electrolyte monitoring was recommended if grade ≥2 CRS occurred. For those in complete response (CR) and without MRD by flow cytometry at 10–5 in peripheral blood (PB) at 6 months after infusion, ibrutinib was ceased.

End points and assessments

The primary end point of the study was investigator-determined CR rate (CRR) at month 4 after CTL019 infusion according to Lugano 2014 criteria.24 Secondary end points included the incidence and severity of adverse events, overall response rates (ORR), MRD-negative rates at months 1, 4, 6, 9, and 12, progression-free survival (PFS), duration of response, and overall survival (OS). Protocol-specified subgroup analyses included analysis of responses according to TP53 mutation status.

Responses were measured using a combination of computed tomography and positron emission tomography. Bone marrow biopsy was performed in all patients at screening and at 1 and 4 months after CTL019 infusion; at other timepoints, it was used to confirm an apparent MRD-negative CR. MRD in PB and bone marrow (BM) was assessed centrally in real-time by multiparameter flow cytometry with a sensitivity of 10–4 to 10–5. Response assessments were performed before lymphodepletion, at months 1, 4, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 after CAR-T infusion, and then every 12 months thereafter.

Adverse events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0, with the exception of CRS and immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), which were graded according to the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) criteria.25

Exploratory analyses

Baseline genomic profiling was performed on archival tumor samples and included FISH for del(17p) and mutational analysis using a custom Agilent SureSelect panel (PanHaem) targeting genes recurrently mutated in hematological malignancies.38 Copy number aberrations and structural variants were analyzed applying a suite of bioinformatics tools to next-generation sequencing (NGS) data as previously published.26,38 Molecular MRD was performed on PB and BM retrospectively using high-throughput immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) sequencing (ClonoSEQ; Adaptive Biotechnologies) at select timepoints with sensitivity ranging from 10-5 to 10-6. CAR-T quantitation was by digital polymerase chain reaction directed against FMC63 on days 6, 14, 28, and later timepoints after CTL019 infusion and expressed as CAR copies per μg of genomic DNA.27 Immunologic profiling of baseline and on-treatment PB samples was described using spectral flow cytometry and compared with healthy controls. Total metabolic tumor volume (TMTV) was performed using a threshold method based on 41% of standardised uptake value (SUVmax).28 Further details of methods are included in the supplemental Methods.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are summarized as median and range, and qualitative variables are summarized as counts and percentages. Unless stated otherwise, the calculation of proportions does not include the missing category in the denominator. All P values and confidence intervals (CIs) are 2-sided.

Response rates are described with 95% CIs using the exact method. Time to event end points (PFS and OS) were described using the Kaplan-Meier method. PFS was calculated from the date of study treatment to the date of first progression or death from any cause. OS was calculated from the date of study treatment to date of death from any cause. Median follow-up was estimated using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method. The survival curves are presented with 95% CIs using the log-log transformation. Safety results are presented as maximum toxicity grade per patient of each adverse event (AE) in table format.

The sample size was determined based on a null hypothesis of CRR at month 4 of 20% with standard treatment available at the time the study was designed in 2019. CRR to ibrutinib monotherapy in BTKi-naïve populations is ∼9% at month 4,29 and CRR to salvage chemotherapy treatment at any timepoint in BTKi-exposed populations is ∼19%.30,31 Assuming a CRR of 48% at month 4 with the combination of CTL019 and ibrutinib, a cohort of 20 evaluable patients has an 83% power to reject the null hypothesis with 1-sided 5% level of significance.

Statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.0.3 (2020-10-10) (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), STATA version 16, and GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1. Additional R packages used were: BaCT2 v1.5, dplyr v1.0.9, flextable v0.7.0, ggplot2 v3.3.5, Hmisc v4.7.0, magrittr v2.0.2, officer v0.4.2, plyr v1.8.6, RODBC v1.3.19, and survival v3.3.1.

Results

Patient characteristics and prior therapies

A total of 21 patients were enrolled between June 2020 and July 2021. One patient withdrew consent before treatment and was replaced, per protocol. All 20 evaluable patients (100%) had successful CAR-T manufacture and received a single infusion with a median cell dose of 3.0 × 108 CAR+ cells (range, 1.3 × 108 to 4.6 ×108) (supplemental Table 1). The median time from study enrollment to CAR-T infusion was 60 days (range, 48-126), and the median time of CAR -T manufacture (from order to infusion) was 49 days (range, 43-65)

Baseline characteristics at study entry are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 66 years, and 75% were male. The median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1-5 lines). At study entry, the median TMTV was 166 cm3 (range, 0-1520). Nineteen patients (95%) had prior rituximab and chemotherapy exposure, including 16 (80%) with exposure to a cytarabine containing regimen and 3 (15%) with prior bendamustine treatment. Fifty-five percent of patients had prior autologous stem cell transplantation. Ten patients (50%) had prior BTKi exposure; 9 were refractory to BTKi therapy (45%), with 3 (15%) having received >1 BTKi. Seven patients (35%) were receiving ibrutinib at the time of study entry, with all other patients commencing at enrollment. The median time on continuous ibrutinib before leukapheresis was 12 days (range, 7-1027). Patients without prior BTKi exposure (BTKi-naïve) had fewer prior lines of therapy (median, 1; range, 1-2) than those with prior BTKi exposure (BTKi-exposed) (median, 3; range, 2-5). Patients exposed to BTKi were more likely to have disease refractory to the last line of treatment.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic, n (%) . | All patients (n = 20) . | BTKi naïve (n = 10) . | BTKi exposed (n = 10) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| Median (range) | 66 (41-74) | 60 (46-72) | 69 (41-74) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 15 (75%) | 7 (70%) | 8 (80%) |

| Female | 5 (25%) | 3 (30%) | 2 (20%) |

| Stage | |||

| II | 5 (26%) | 4 (44%) | 1 (10%) |

| III | 1 (5%) | 1 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

| IV | 13 (68%) | 4 (44%) | 9 (90%) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| TMTV | |||

| Median, cm3 (range) | 166 (0-1520) | 145 (0-468) | 169 (20-1520) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Bone marrow involvement | |||

| Involved | 11 (58%) | 4 (40%) | 7 (78%) |

| Not involved | 8 (42%) | 6 (60%) | 2 (22%) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| ECOG | |||

| 0 | 14 (70%) | 7 (70%) | 7 (70%) |

| 1 | 6 (30%) | 3 (30%) | 3 (30%) |

| Histology | |||

| Pleomorphic | 5 (25%) | 4 (40%) | 1 (10%) |

| Blastoid | 3 (15%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (10%) |

| Ki67% | |||

| <30% | 5 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (71%) |

| >=30% | 12 (71%) | 10 (100%) | 2 (29%) |

| Missing | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| sMIPI score category | |||

| Low risk (<5.7) | 9 (47%) | 6 (67%) | 3 (30%) |

| Intermediate risk (5.7 to <6.2) | 8 (42%) | 3 (33%) | 5 (50%) |

| High risk (≥6.2) | 2 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (20%) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| TP53 status | |||

| Deleted | 8 (40%) | 3 (30%) | 5 (50%) |

| Mutated | 8 (40%) | 3 (30%) | 5 (50%) |

| Both deleted and mutated | 7 (35%) | 2 (20%) | 5 (50%) |

| Not assessed (molecular) | 2 (10%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (10%) |

| Median number of prior therapies, n (range) | 2 (1-5) | 1 (1-2) | 3 (2-5) |

| Number of prior therapies | |||

| 1 | 9 (45%) | 9 (90%) | 0 (0%) |

| 2 | 5 (25%) | 1 (10%) | 4 (40%) |

| 3+ | 6 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (60%) |

| POD24 after initial therapy | 13 (65%) | 6 (60%) | 7 (70%) |

| Refractory to most recent line of therapy | 10 (50%) | 1 (10%) | 9 (90%) |

| Prior therapy, n (%) | |||

| Rituximab | 19 (95%) | 10 (100%) | 9 (90%) |

| Bendamustine | 3 (15%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (20%) |

| Anthracycline | 17 (85%) | 9 (90%) | 8 (80%) |

| Cytarabine | 16 (80%) | 8 (80%) | 8 (80%) |

| Autologous transplant | 11 (55%) | 7 (70%) | 4 (40%) |

| Venetoclax | 4 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (20%) |

| BTK inhibitor/s∗ | 10 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (100%) |

| Characteristic, n (%) . | All patients (n = 20) . | BTKi naïve (n = 10) . | BTKi exposed (n = 10) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| Median (range) | 66 (41-74) | 60 (46-72) | 69 (41-74) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 15 (75%) | 7 (70%) | 8 (80%) |

| Female | 5 (25%) | 3 (30%) | 2 (20%) |

| Stage | |||

| II | 5 (26%) | 4 (44%) | 1 (10%) |

| III | 1 (5%) | 1 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

| IV | 13 (68%) | 4 (44%) | 9 (90%) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| TMTV | |||

| Median, cm3 (range) | 166 (0-1520) | 145 (0-468) | 169 (20-1520) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Bone marrow involvement | |||

| Involved | 11 (58%) | 4 (40%) | 7 (78%) |

| Not involved | 8 (42%) | 6 (60%) | 2 (22%) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| ECOG | |||

| 0 | 14 (70%) | 7 (70%) | 7 (70%) |

| 1 | 6 (30%) | 3 (30%) | 3 (30%) |

| Histology | |||

| Pleomorphic | 5 (25%) | 4 (40%) | 1 (10%) |

| Blastoid | 3 (15%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (10%) |

| Ki67% | |||

| <30% | 5 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (71%) |

| >=30% | 12 (71%) | 10 (100%) | 2 (29%) |

| Missing | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| sMIPI score category | |||

| Low risk (<5.7) | 9 (47%) | 6 (67%) | 3 (30%) |

| Intermediate risk (5.7 to <6.2) | 8 (42%) | 3 (33%) | 5 (50%) |

| High risk (≥6.2) | 2 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (20%) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| TP53 status | |||

| Deleted | 8 (40%) | 3 (30%) | 5 (50%) |

| Mutated | 8 (40%) | 3 (30%) | 5 (50%) |

| Both deleted and mutated | 7 (35%) | 2 (20%) | 5 (50%) |

| Not assessed (molecular) | 2 (10%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (10%) |

| Median number of prior therapies, n (range) | 2 (1-5) | 1 (1-2) | 3 (2-5) |

| Number of prior therapies | |||

| 1 | 9 (45%) | 9 (90%) | 0 (0%) |

| 2 | 5 (25%) | 1 (10%) | 4 (40%) |

| 3+ | 6 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (60%) |

| POD24 after initial therapy | 13 (65%) | 6 (60%) | 7 (70%) |

| Refractory to most recent line of therapy | 10 (50%) | 1 (10%) | 9 (90%) |

| Prior therapy, n (%) | |||

| Rituximab | 19 (95%) | 10 (100%) | 9 (90%) |

| Bendamustine | 3 (15%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (20%) |

| Anthracycline | 17 (85%) | 9 (90%) | 8 (80%) |

| Cytarabine | 16 (80%) | 8 (80%) | 8 (80%) |

| Autologous transplant | 11 (55%) | 7 (70%) | 4 (40%) |

| Venetoclax | 4 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (20%) |

| BTK inhibitor/s∗ | 10 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (100%) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; sMIPI, secondary mantle cell international prognostic index; POD24, progression of disease within 24 months.

Seven patients had previously received ibrutinib alone, 1 patient had previously received ibrutinib and pirtobrutinib, 1 patient had previously received zanubrutinib and pirtobrutinib, and 1 patient had previously received TG-1701 and ibrutinib.

High-risk features were common; 65% of patients had experienced progression of disease within 24 months (POD24) after initial therapy, 63% had intermediate or high secondary mantle cell lymphoma international prognostic index (MIPI) score at study entry, and 15% had blastoid morphology.

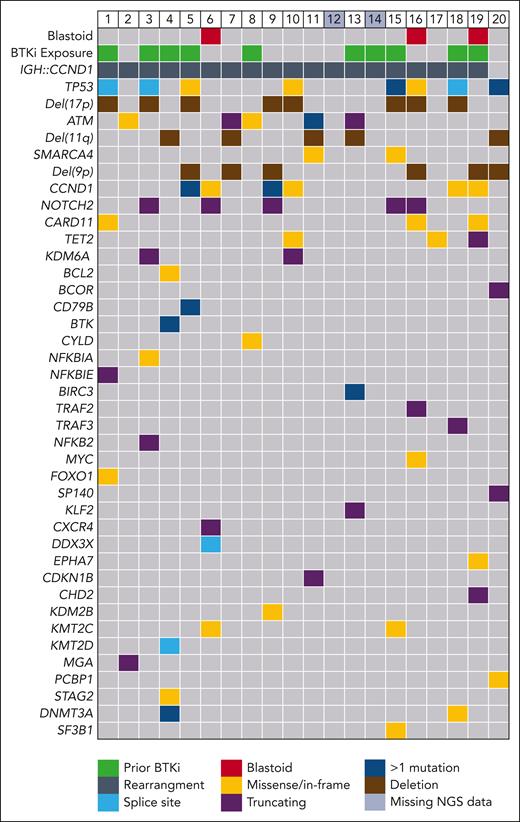

MCL genomic characteristics

Nineteen patients (95%) had MCL with confirmed IGH::CCND1 fusion by FISH, and 1 patient was diagnosed based on cyclin D1 and SOX11 expression by immunohistochemistry. Genomic profiling by NGS was available for 18 patients (90%) (Figure 1). Recurrent abnormalities included mutations in CCND1 (30%), ATM (25%), and NOTCH2 (25%).

Key MCL-related clinical, pathologic, and genomic characteristics in evaluable patients. Each column represents an individual patient. Relevant genes with abnormalities detected in at least 1 patient (≥5% prevalence) are shown. Colored squares indicate the presence of a genomic abnormality or clinical feature and individual colors the nature of the change. Deletions were detected by a combination of fluorescent in-situ hybridization, or where not available by next-generation sequencing-based copy number analysis. Multihit is defined as the presence of >1 mutations occurring in the same gene in the same sample. Two patients did not have next-generation sequencing data available (patients 12 and 14).

Key MCL-related clinical, pathologic, and genomic characteristics in evaluable patients. Each column represents an individual patient. Relevant genes with abnormalities detected in at least 1 patient (≥5% prevalence) are shown. Colored squares indicate the presence of a genomic abnormality or clinical feature and individual colors the nature of the change. Deletions were detected by a combination of fluorescent in-situ hybridization, or where not available by next-generation sequencing-based copy number analysis. Multihit is defined as the presence of >1 mutations occurring in the same gene in the same sample. Two patients did not have next-generation sequencing data available (patients 12 and 14).

Del(17p) and TP53 mutation status was known in 20 (100%) and 18 (90%) patients, respectively, with 9 patients (45%) demonstrating TP53 aberrancy. One patient (5%) had del(17p) without mutation, and 1 patient (5%) had multiple TP53 mutations without deletion. The remaining 7 patients (35%) had evidence of concurrent del(17p) and TP53 mutations. Alterations in the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex were seen in 8 (40%), with 2 (10%) having mutations in SMARCA4 and 6 (30%) demonstrating del(9p) involving SMARCA2.

Treatment and responses

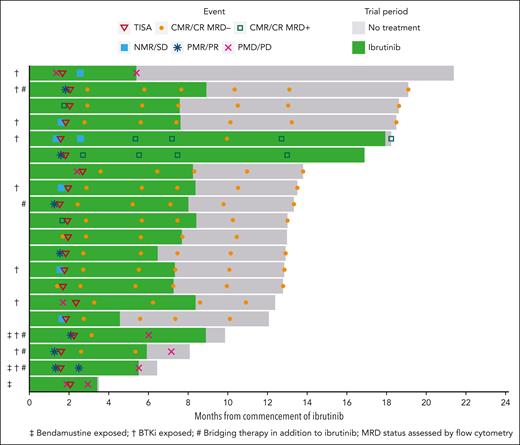

All 20 evaluable patients were on ibrutinib from the time of study enrollment, and 5 required additional bridging therapy during CTL019 manufacture, consisting of 1 to 2 cycles of rituximab, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin (n = 4) or venetoclax (n = 1). Eleven patients (55%) achieved objective response before lymphodepletion (7 partial response [PR] and 4 CR), 5 had stable disease (SD), and 4 had progressive disease (PD) (Figure 2).

Swimmer plot of patient responses. Each line represents an individual patient. The solid green indicates the duration of ibrutinib therapy. Per protocol, ibrutinib was ceased in patients who were MRD-negative by flow cytometry at month 6 (when results of the test became available). Two patients (lanes 5 and 6) were MRD positive and continued ibrutinib beyond 6 months. The patient in lane 18 had an equivocal response assessment at month 4 after CTL019 infusion and continued ibrutinib until an early follow-up scan confirmed progressive disease (progression was deemed to have occurred at the earlier timepoint).

Swimmer plot of patient responses. Each line represents an individual patient. The solid green indicates the duration of ibrutinib therapy. Per protocol, ibrutinib was ceased in patients who were MRD-negative by flow cytometry at month 6 (when results of the test became available). Two patients (lanes 5 and 6) were MRD positive and continued ibrutinib beyond 6 months. The patient in lane 18 had an equivocal response assessment at month 4 after CTL019 infusion and continued ibrutinib until an early follow-up scan confirmed progressive disease (progression was deemed to have occurred at the earlier timepoint).

The median ibrutinib dose intensity was 100% (range, 57%-100%); 5 patients required ibrutinib dose adjustments and 3 required dose interruption for CRS (n = 2) and rash (n = 1). Patients received ibrutinib on study for a median of 7.3 months (range, 3.8-18).

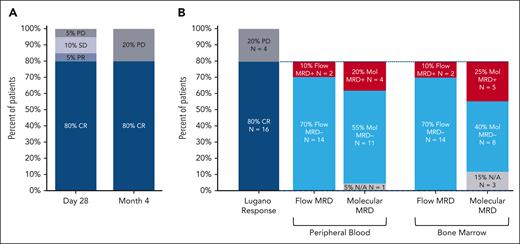

After CTL019 infusion, all 20 patients were evaluable for response. At 1 month after infusion, the ORR was 85% (CRR, 80%), with 2 patients demonstrating SD (10%) and 1 patient PD (5%) (Figure 2). At the primary end point of 4 months after infusion, the ORR and CRR were both 80% (Figure 3A). One patient deepened their response beyond the first assessment (SD to CR). Of the 16 patients in CR at 4 months, 14 were negative for MRD by flow cytometry, resulting in a 70% overall MRD negativity rate at the primary end point (Figure 3B). All 14 patients with flow MRD negativity ceased ibrutinib at the 6-month timepoint. Molecular MRD results were available from BM samples in 14 and from PB in 15 of the 16 patients with CR. In total, 5 patients demonstrated detectable molecular MRD positivity in the marrow (4 were also positive in PB), of whom 3 were negative by flow cytometry. One patient had a concomitant plasma cell dyscrasia at baseline (monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance), and therefore, molecular positivity may have reflected detection of a clonally related plasma cell neoplasm (flow cytometry was negative in the same sample). One patient with molecular MRD positivity in the BM and PB had progressive disease at 6 months, 2 remained on ibrutinib without progression (16.9 and 18.2 months of follow-up), and the remaining patient remains progression free after 12.8 months of observation despite ceasing active therapy.

Response to treatment. Response to treatment represented as (A) best response at any time point and at the primary end point of 4 months after CTL019 infusion and (B) MRD status in the 16 patients in CR at month 4 by PB immunophenotyping and immunoglobulin high-throughput sequencing in PB and bone marrow aspirate samples. N/A, not available; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Response to treatment. Response to treatment represented as (A) best response at any time point and at the primary end point of 4 months after CTL019 infusion and (B) MRD status in the 16 patients in CR at month 4 by PB immunophenotyping and immunoglobulin high-throughput sequencing in PB and bone marrow aspirate samples. N/A, not available; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

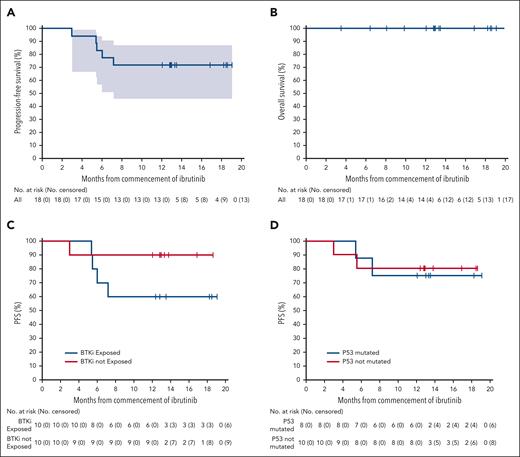

At a median follow-up of 13 months (range, 3-21), the median PFS had not been reached (Figure 4). The estimated PFS and OS rates at 12 months were 75% and 100%, respectively. No patient had died at the time of data cutoff.

Survival outcomes. Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS and OS in evaluable patients (A-B) and PFS in patients with prior BTKi exposure (C) and patients with TP53 mutated MCL (D).

Survival outcomes. Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS and OS in evaluable patients (A-B) and PFS in patients with prior BTKi exposure (C) and patients with TP53 mutated MCL (D).

Safety

Adverse events of any grade were recorded in 100% of patients, and grade 3 to 4 events occurred in 75% (supplemental Table 2). The most common adverse events considered related to study therapy were CRS of any grade (75%), neutropenia (50%), diarrhea (30%), rash (20%), and thrombocytopenia (15%) (supplemental Figure 2). Grade 3-4 anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia were present in 0%, 15%, and 25% of patients at day 28 (n = 20), no patients at day 90 (n = 19), and 0%, 7%, and 0% at month 12 (n = 14), respectively. Eight infection episodes were observed in a total of 4 patients (20%) within the first month after infusion and a further 8 episodes in 5 patients (25%) beyond that timepoint and were predominantly grade 1-2 (supplemental Table 3). This included 1 patient with symptomatic grade 3 COVID-19 infection during the follow-up period, who recovered after 4 days. There was 1 event of atrial fibrillation that occurred before CTL019 infusion and in the setting of sepsis; no other significant arrhythmias were observed.

CRS occurred in 75%, was grade 1-2 in 55%, and grade 3 in 20% (Table 2). Baseline median TMTV was similar in patients without CRS (183cm3; range, 0-1520), those with grade 1-2 CRS (131cm3; range 0-1436), and those with grade ≥3 CRS (145cm3; range 109-169). In the 4 patients experiencing grade 3 CRS, all had measurable disease at the time of CTL019 infusion. For all patients, the median onset of CRS overall was at day 3 (range, 1-12 days), and the median duration was 4 days (range, 1-15). No grade 4 CRS occurred. ICANS was observed in 2 patients (grade 1, n = 1; grade 2, n = 1), lasted for 2 and 4 days, and resolved completely (Table 2). Tocilizumab was administered in 9 patients (45%) (median doses, 2; range, 1-2), dexamethasone in 7 patients (35%) (median doses, 1; range, 1-2), and vasopressors in 2 patients (10%).

CRS, ICANS, and management

| CRS . | . |

|---|---|

| Any grade, n (%) | 15 (75%) |

| Grade 1 | 7 (35%) |

| Grade 2 | 4 (20%) |

| Grade 3 | 4 (20%) |

| Grade 4 | 0 (0%) |

| Median time to onset, d (range) | 3 (1-12) |

| Median duration of CRS, d (range) | 4 (1-15) |

| Tocilizumab use, n (%) | 8 (40%) |

| Vasopressor use, n (%) | 2 (10%) |

| CRS . | . |

|---|---|

| Any grade, n (%) | 15 (75%) |

| Grade 1 | 7 (35%) |

| Grade 2 | 4 (20%) |

| Grade 3 | 4 (20%) |

| Grade 4 | 0 (0%) |

| Median time to onset, d (range) | 3 (1-12) |

| Median duration of CRS, d (range) | 4 (1-15) |

| Tocilizumab use, n (%) | 8 (40%) |

| Vasopressor use, n (%) | 2 (10%) |

| Neurotoxicity (ICANS) . | . |

|---|---|

| Any grade, n (%) | 2 (10%) |

| Grade 1 | 1 (5%) |

| Grade 2 | 1 (5%) |

| Corticosteroid dose, median cumulative dexamethasone equivalent (range) | 25 mg (20-30) |

| Duration of neurotoxicity, median days (range) | 3 (2-4) |

| Resolution to grade 0 | 2 (100%) |

| Neurotoxicity (ICANS) . | . |

|---|---|

| Any grade, n (%) | 2 (10%) |

| Grade 1 | 1 (5%) |

| Grade 2 | 1 (5%) |

| Corticosteroid dose, median cumulative dexamethasone equivalent (range) | 25 mg (20-30) |

| Duration of neurotoxicity, median days (range) | 3 (2-4) |

| Resolution to grade 0 | 2 (100%) |

ICANS, immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome.

PB B-cell aplasia was present in all patients after CTL019 infusion and persisted for at least 6 months in all patients (supplemental Figure 3). Hypogammaglobulinemia was present in 4 patients at baseline and developed in 10 further patients throughout the study (supplemental Figure 4); 1 received gammaglobulin replacement. B-cell recovery, defined as PB B cells >1% of total lymphocytes,32 was observed in 6 patients at a median of 9 months (range, 6-12).

Deep and durable responses were seen in high-risk subgroups

Subgroup analysis at month 4 demonstrated CRR of 90% and 70% in BTK-naïve and BTK-exposed populations, respectively (supplemental Figure 5). Seven of the 8 patients (88%) with TP53 mutation achieved CR, with 4 of 6 evaluable responding patients (67%) demonstrating molecular MRD negativity. Comparable CRRs were observed irrespective of prior ASCT status, preinfusion response, blastoid histology, or Ki67%. There was no significant difference in TMTV between the responders and nonresponders, with a median TMTV of 123 cm3 (range, 0-1520) vs 223 cm3 (range, 0-468), respectively (P = .6).

These deep responses translated into durable PFS (Figure 4C-D). The PFS estimate at 12 months in patients naïve to BTKi was 90%, compared with 60% in those exposed to BTKi. Estimates at 12 months were similar for patients with or those without TP53 mutation or SWI-SNF aberrancy (80% vs 75% and 88% vs 70%, respectively).

Three patients had prior bendamustine exposure, with time from last bendamustine exposure to leukapheresis of 1.8, 3.9, and 10.3 months. No patient exposed to bendamustine achieved a durable response, with all 3 patients demonstrating disease progression at or prior to the primary end point (Figure 2). Patients exposed to bendamustine were older and had generally high-risk clinical features, including elevated sMIPI scores, increased median number of prior therapies, and higher rates of POD24, although TP53 aberrancy was not observed in this group (supplemental Table 4).

CAR-T cellular kinetic patterns were associated with deep responses

CAR-T peak expansion was observed at a median of 14 days (range, 6-14) at a level of 6515 CAR copies per μg of genomic DNA (gDNA) (range, 2764-17 858) (supplemental Figure 1A). A delayed time to peak was observed in patients with prior BTKi exposure compared with BTK-naïve patients (median, 14 vs 6 days, respectively), although no difference was noted in peak levels or area under the curve to day 28 (AUCd28) between the groups (supplemental Figure 1B and supplemental Table 5).

Cellular kinetics were significantly associated with depth of response. Patients achieving CR with MRD negativity by flow cytometry at month 4 (deep responders) demonstrated more robust expansion, with higher peak levels (7691 vs 2587 CAR copies/μg gDNA; P = .03) and AUCd28 (107 899 vs 42 804 CAR copies/μg gDNA; P = .04), than progressors or patients with MRD positivity (supplemental Figure 1C).

We also observed inferior CAR-T expansion in patients exposed to bendamustine (supplemental Figure 1D), with lower peak CAR (median, 2561 CAR copies/μg gDNA; range, 1884-4610 vs 7515 CAR copies/μg gDNA; range, 1124-71 005; P = .05) and AUCd28 (36 220 CAR copies/μg gDNA × days vs 105 450 CAR copies/μg gDNA × days; P = .09).

CAR T-cell numbers in the PB decreased over time and approached zero, but low levels of CAR copies remained present (above the limit of detection) at the final timepoint tested for each patient (median, 6 months after infusion; supplemental Figure 3). There was no clear association between B-cell recovery, CAR-T levels, and development of PD; all 5 patients with PD demonstrated detectable CAR copies and ongoing B-cell aplasia at the time of progression. Analysis of PB samples at the time of progression showed detectable MCL by flow cytometry in 2 of the 5 progressing patients; 1 patient demonstrated CD19 negativity and the other a CD19dim phenotype.

Immunologic assessment: an exhausted T-cell phenotype is associated with treatment resistance or early failure and may be improved with ibrutinib therapy

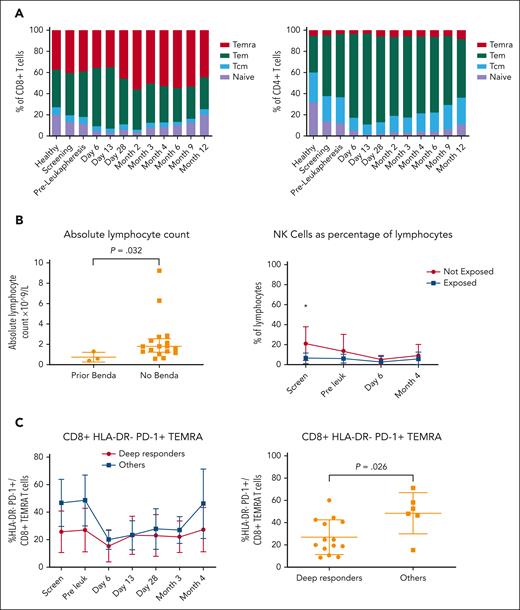

At the time of screening, enrolled patients demonstrated on average a lower percentage of naïve T cells and a higher percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ terminally differentiated effector memory subsets than healthy controls (Figure 5A), an effect that was more pronounced in patients with shorter exposure to ibrutinib at that time (supplemental Figure 6A). Immediately after lymphodepleting chemotherapy and CTL019 infusion, there was a further reduction in the naïve T-cell fraction, expansion of the CD4+/CD8+ effector memory phenotype, and increased checkpoint expression (HLA-DR, TIM3, and LAG-3), followed by a gradual re-equilibration of subsets closer to healthy controls by month 12.

Immunologic analysis by spectral flow cytometry and clinical correlation. (A) Panel depicts CD8+ (left) and CD4+ (right) T-cell subset changes, respectively, at various timepoints from screening to month 12 after CTL019 infusion and compared with healthy donors (n = 16). (B) Panel shows a comparison between the absolute lymphocyte count (left) and percentage of NK cells as a proportion of mononuclear cells (right) at screening in patients exposed and those not exposed to bendamustine. (C) Panel depicts a comparison of CD8+/HLA–DR–/PD-1+ TEMRAs as a proportion of T cells at various timepoints (left) and preleukapheresis (right) in deep responders vs all other patients. Deep responder was defined as a patient with negative MRD by flow cytometry at month 4. NK cells, natural killer cells; Tcm, T central memory cells; Tem, T effector memory cells; TEMRAs, terminally differentiated effector memory cells (CD45RA+).

Immunologic analysis by spectral flow cytometry and clinical correlation. (A) Panel depicts CD8+ (left) and CD4+ (right) T-cell subset changes, respectively, at various timepoints from screening to month 12 after CTL019 infusion and compared with healthy donors (n = 16). (B) Panel shows a comparison between the absolute lymphocyte count (left) and percentage of NK cells as a proportion of mononuclear cells (right) at screening in patients exposed and those not exposed to bendamustine. (C) Panel depicts a comparison of CD8+/HLA–DR–/PD-1+ TEMRAs as a proportion of T cells at various timepoints (left) and preleukapheresis (right) in deep responders vs all other patients. Deep responder was defined as a patient with negative MRD by flow cytometry at month 4. NK cells, natural killer cells; Tcm, T central memory cells; Tem, T effector memory cells; TEMRAs, terminally differentiated effector memory cells (CD45RA+).

Based on the clinical observation of poor efficacy in patients exposed to bendamustine, we explored absolute lymphocyte numbers and immunophenotypic differences in this population. Patients exposed to bendamustine had a lower PB total lymphocyte count (median, 0.6 × 109/L vs 1.8 × 109/L; P = .03), lower absolute CD3+ T-cell counts (median, 0.5 × 109/L vs 1.0 × 109/L; P = .15), and lower percentage of natural killer cells at study entry (Figure 5B).

To explore the potential role of preleukapheresis T-cell exhaustion as a contributor to poor CAR-T function, we examined T-cell subsets in depth at baseline and before T-cell collection (Figure 5C). Deep responders demonstrated a lower proportion of CD8+/HLA–DR–/PD-1+ terminally differentiated effector memory subsets at screening and preleukapheresis, consistent with a less exhausted CD8+ T-cell phenotype. Although our study did not include a control population of patients without concurrent ibrutinib at the time of leukapheresis, 5 patients had received an extended period of continuous ibrutinib immediately before T-cell collection (>100 days). Patients with extended ibrutinib exposure demonstrated a higher baseline proportion of CD8+ naïve T cells, a lower proportion of baseline effector memory cells, and reduced CD8+/PD-1+ central memory T cells at baseline and after CAR-T infusion (supplemental Figure 6B). Extended ibrutinib exposure was also associated with higher peak CAR-T levels and AUCd28, however, these did not reach statistical significance (supplemental Figure 7).

Discussion

CD19-directed CAR T cells are a recently established and remarkably active therapy in BTKi-resistant MCL with high rates of CR. However, their use is associated with significant toxicity, which can often be severe. Furthermore, MCL is commonly aggressive in its kinetics of relapse, with a large proportion of patients experiencing BTKi failure being unable to receive a subsequent treatment, potentially limiting the applicability of this effective therapy.33 In those whose disease responds to CAR T-cell therapy, more than 50% will experience relapse within 3 years.13,34

We therefore sought to test the hypothesis that the combination of ibrutinib and CTL019 would be safely deliverable and lead to improved outcomes in patients irrespective of prior BTKi-exposure. For patients with BTKi exposure, many of whom had disease resistance to BTKi-therapy, the ibrutinib was rationalized as a way to improve T-cell function and abrogate CAR T-cell toxicity, while also preventing explosive progression during manufacturing. For patients who achieved deep response to the combination, we also sought to limit the ongoing use of ibrutinib, hypothesizing that the driver for disease eradication was the CAR T-cell therapy, and that there could be a quality of life or adverse event benefit to patients by providing fixed-course therapy.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is one of the first to prospectively test CAR T cells as part of second-line therapy and the first to report the combination of a BTKi and CAR T cells in MCL, building upon the positive experience in prior CLL studies.18,19 In this setting, we demonstrated high rates of CR, including a significant proportion of patients achieving flow and molecular MRD negativity. The genomic characteristics of our cohort were comprehensively described, showing that the combination retained efficacy despite the presence of high-risk genetic changes that typically convey resistance to cytotoxic agents and many targeted treatments used as monotherapy or in combination. Specifically, patients whose MCL harbored SWI-SNF or TP53 mutations, which were in most cases accompanied by del(17p), achieved rates of CR equivalent to those with wildtype disease. Our cohort adds significantly to the limited literature on the effectiveness of novel immunotherapies in these difficult to treat populations.

Overall, the efficacy of the combination appeared comparable with that seen in the ZUMA-2 and TRANSCEND-NHL-001 studies (CRR, 67% and 59%, respectively) and real-world data,34,35 with a CRR of 80% at month 4 that remained durable at 12 months (estimated PFS, 75%). In patients who were naïve to BTKi, the CRR was 90%, with no patient with responsive disease in this category demonstrating disease progression at the time of data cutoff (12-month estimated PFS, 90%). Although the independent antitumor activity of ibrutinib undoubtedly contributed to responses in this group, the rates of complete and MRD-negative response are far higher than what would be expected with ibrutinib alone. Furthermore, these results compare favorably with other real-world experiences of brexucabtagene autoleucel monotherapy in patients naïve to BTKi, in which CRRs ranging from 79% to 88% have been reported and PFS at 12 months was 75%.34,36 Detailed immunologic assessment demonstrated improved rates and depth of response in patients with a less-exhausted baseline T-cell phenotype. Exhaustion markers were reduced in patients with longer ibrutinib exposure immediately before leukapheresis. CAR T-cell peak expansion (geometric mean, 7138 vs 5530 copies/μg gDNA) and AUC (geometric mean, 96 627 vs 64 600 copies/μg gDNA × days) were higher than that observed with tisagenlecleucel alone when used for DLBCL on the JULIET study. Improved expansion kinetics were again more pronounced in patients with longer ibrutinib exposure. Although our study did not include a control arm without concurrent ibrutinib, these indirect observations suggest that ibrutinib positively contributed to CAR-T fitness and postinfusion kinetics; however, this ultimately requires confirmation in a randomized study.

In line with prior observations, we also observed reduced efficacy in patients with prior bendamustine exposure.13,34 Indeed, none of the 3 patients with prior bendamustine exposure experienced a lasting response beyond the primary end point. Although we are cautious of overinterpreting this small cohort of older patients with generally higher-risk clinical features, correlative analysis largely corroborated the clinical findings, particularly with demonstration of lower T-cell numbers at baseline and impaired postinfusion cellular kinetics. Although our findings do not necessarily preclude durable outcomes after bendamustine therapy, they support active consideration of the timing and sequencing of CAR T-cell therapy after T-cell depleting therapies.

Despite the previously demonstrated potential for ibrutinib to abrogate CRS in the setting of CLL,18 we observed rates of CRS, including grade 2 events, in similar proportions to that seen with alternative CAR T-cell products.14,15 However, in contrast to the >30% of patients who experience grade ≥3 ICANS with brexucabtagene autoleucel,14,34 neurotoxicity was rare in our cohort. This may ultimately reflect the characteristics of CTL019/tisagenlecleucel itself, which has low rates of neurotoxicity in other contexts such as DLBCL,37 although a mitigating role from ibrutinib is also possible. We observed no significant arrhythmias in the postinfusion phase.

Our study has limitations, both in its small size and the lack of control arm, which impairs direct interrogation of the relative contribution of ibrutinib in modifying CAR T-cell fitness and toxicity in this context. Furthermore, the inclusion of both patients exposed to BTKi and those naïve to BTKi reduces the sample sizes from which to draw potential conclusions. The optimal duration of ibrutinib after CAR T-cell infusion is also uncertain, with many patients achieving deep MRD-negative remissions at 1 month, raising the possibility that earlier MRD-directed cessation of BTK inhibition may have resulted in equally good outcomes.

Nonetheless, this study contributes significantly to the emerging experience of combining BTK inhibition with T-cell redirecting therapies, demonstrating both feasibility and effectiveness in MCL irrespective of prior BTKi exposure or the presence of high-risk clinical or molecular features. Work is ongoing to translate these lessons into other novel combinations, including a follow-on study of BTK inhibition in combination with a T-cell redirecting bispecific antibody (NCT05833763).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding support from Roche, the Wilson Centre for Blood Cancer Genomics, the Snowdome Foundation, the Royal College of Pathologists Australasia Foundation Grant and Mike and Carol Ralston Travelling Fellowship Grant, and the Gilead Fellowship Grant.

Authorship

Contribution: M.D. and A.M. designed the study and wrote the manuscript; M.D., A.M., N. Hamad, C.Y.C., M.A.A., A.K., and M.R. recruited and treated patients; R.K., D.R., P.B., J.F.S., A.M., and M.D. designed the research program, which was performed by R.K., D.R., P.B., I.C., G.R., S.L., H.M., and N. Holzwart performed research; J.X. and A.M. performed statistical analysis; J.S. and Z.S. performed imaging analysis; and all authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.M. reports honoraria and/or research funding from Roche and Novartis. N. Hamad reports membership on the board of directors or advisory committees and speakers bureau in Novartis. C.Y.C. reports receiving consultancy fee, honoraria, and/or research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Roche, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Gilead, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Janssen, Eli Lilly and Company, TG Therapeutics, and BeiGene. C.T. reports honoraria and/or research funding from Loxo, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, AbbVie, and Janssen. P.B. reports consultancy fee and/or honoraria from Adaptive Biotechnologies:, AstraZeneca, and Servier. S.L. reports consultancy fee from EUSA Pharma. D.R. reports honoraria and/or research funding from BMS, Takeda, Novartis, Amgen, and MSD. R.K. reports research funding from CRISPR Therapeutics. M.A.A. reports honoraria from Roche, Takeda, Novartis, Gilead, AstraZeneca, Janssen, and AbbVie; and is currently employed with Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, which receives milestone payments in relation to venetoclax, to which the author is entitled to a share. A.K. reports honoraria from BMS, Janssen, Celgene, Roche, and Mundipharma; and travel grant from Novartis. J.F.S. reports honoraria and/or consultacy fee and/or research funding from and/or membership on board of directors or advisory committees or speaker’s bureau in Gilead, Genor Biopharma, TG Therapeutics, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Celgene, BMS, AbbVie, Janssen, and AstraZeneca. M.D. reports honoraria and/or consultancy fee and/or research funding from Roche, BMS, Novartis, Kite, Gilead, Nkarta, AdiCet Bio, Interius, Janssen, MSD, Amgen, Takeda, and Celgene. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael Dickinson, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, 305 Grattan Street, Melbourne, VIC, Australia 3000; email: Michael.dickinson@petermac.org.

References

Author notes

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author, Michael Dickinson (michael.dickinson@petermac.org).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal