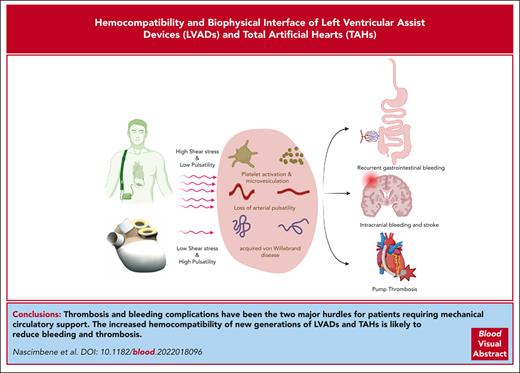

Visual Abstract

Over the past 2 decades, there has been a significant increase in the utilization of long-term mechanical circulatory support (MCS) for the treatment of cardiac failure. Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) and total artificial hearts (TAHs) have been developed in parallel to serve as bridge-to-transplant and destination therapy solutions. Despite the distinct hemodynamic characteristics introduced by LVADs and TAHs, a comparative evaluation of these devices regarding potential complications in supported patients, has not been undertaken. Such a study could provide valuable insights into the complications associated with these devices. Although MCS has shown substantial clinical benefits, significant complications related to hemocompatibility persist, including thrombosis, recurrent bleeding, and cerebrovascular accidents. This review focuses on the current understanding of hemostasis, specifically thrombotic and bleeding complications, and explores the influence of different shear stress regimens in long-term MCS. Furthermore, the role of endothelial cells in protecting against hemocompatibility-related complications of MCS is discussed. We also compared the diverse mechanisms contributing to the occurrence of hemocompatibility-related complications in currently used LVADs and TAHs. By applying the existing knowledge, we present, for the first time, a comprehensive comparison between long-term MCS options.

Introduction

Mechanical circulatory support (MCS) is increasingly utilized in treating cardiac failure. Currently, HeartMate3 (HM3) is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved device for both bridge-to-transplant and destination therapy.1 Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) associated morbidity has been considerably reduced overtime. However, significant complications persist closely related to LVAD hemocompatibility, include pump thrombosis or recurrent bleeding.2 In parallel with the development and clinical use of LVADs, interest in developing total artificial hearts (TAHs) was sparked after the first TAH was implanted on 4 April 1969, by Cooley in Houston, TX.3 As of 2023, 2 TAHs have indications or are in active clinical development.4 First, there is a pneumatically driven TAH (SynCardia, Tucson, AZ) with synthetic blood-contacting surfaces and mechanical valves, requiring high levels of anticoagulation.5,6 It uses external air compressors to activate the pump, constraining patient’s quality of life. Aeson, a bioprosthetic TAH (A-TAH; Carmat, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France) has thus been developed to address the poor hemocompatibility observed with SynCardia and/or external biventricular assist devices to further improve patient quality of life. The primary original design feature of the A-TAH is the use of bovine pericardial tissue inside the ventricles, which are exposed to blood.7 The hemodynamics introduced by LVADs and TAHs differ significantly, but despite the potential for such a comparison to offer new insights into the underlying mechanisms of clinical complications associated with these devices, they have not been comparatively evaluated. This review aims to address some of these knowledge gaps by focusing on the differential hemocompatibilities of LVADs and TAHs, their biophysical interfaces with blood, and their clinical complications.

Hemodynamics of LVADs and TAHs

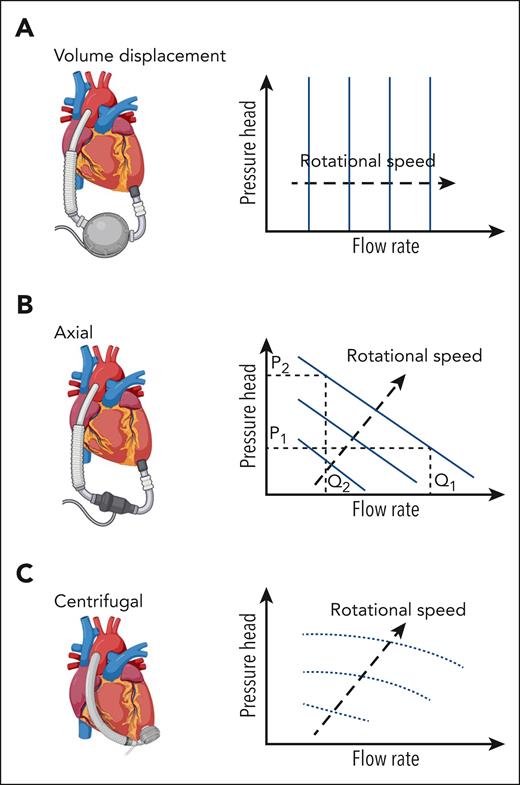

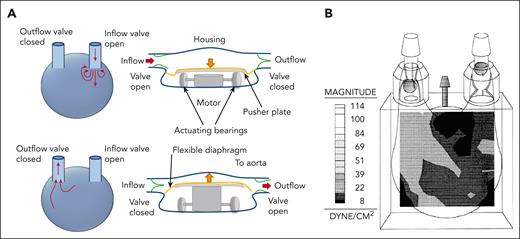

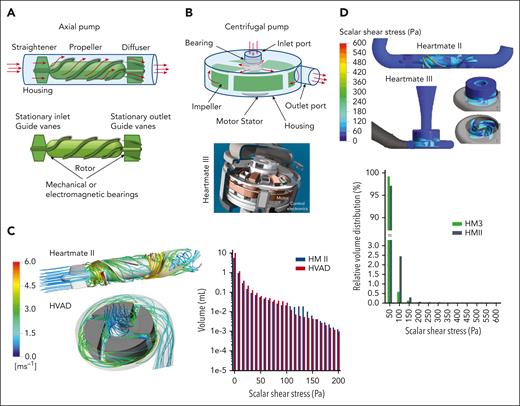

Pumps in MCS are categorized as positive displacement or rotary continuous flow, with performance defined by pressure head and flow rates. Positive displacement pumps have a flow rate that depends only on the pump volume and speed, which is independent from the pressure head. For rotary pumps, the relationship depends on pump style (axial or centrifugal) and speed (Figure 1). Precise flow fields in these devices are complex, varying spatially and temporally throughout the cardiac cycle and with pumping output. Flow field refers to the distribution of fluid velocity throughout a region in space at an instance in time. First-generation pumps are positive displacement models. They are larger and work by driving blood into and out of the pump through expansion and contraction of a pumping chamber, typically using a membrane and pusher plate (Figure 2A). One-way valves ensure unidirectional flow during pumping. Shear stress in these pumps is estimated at 100 to 500 dynes/cm2, depending on pump size and rate8-10 (Figure 2B). Comparatively, native valves and bioprosthetic valves are estimated to reach a maximum shear stress of 100 dynes/cm211 and shear stress in healthy circulation remains below 72 dynes/cm2.12,13 Despite flow fields similar to native ventricles, these pumps lost favor owing to their size, lack of durability, and hemostatic complications and infection. Second- and third-generation ventricular pumps are generally categorized as rotary continuous-flow (CF) pumps with fewer moving parts, a smaller profile, and a lower power consumption compared with positive displacement pumps.14 These pumps contain rotating impellers or propellers that drive blood while increasing the pressure head (Figure 3). Compared with positive displacement pumps, rotary pumps produce higher supraphysiological shear stress (Table 1) and can also generate turbulence.15,21,23 Impellers and propellers rotate on a mechanical bearing in second-generation devices, but this is replaced by magnetic levitation in third-generation devices to increase durability and reduce thrombosis in the bearing region, with some devices being pulsatile-capable. Rotary pumps are subdivided into axial (Figure 3A) or centrifugal (Figure 3B). Axial pumps typically operate with a propeller that pushes blood in line with the axis of rotation and can increase flow (1.5-6 L/min) with a lower rise in pressure (50-140 mmHg) at high rotational speeds of 6000 to 45 000 rpm (Figure 1B), leading to supraphysiologically high shear stress (5000-24 000 dynes/cm2, Figure 3C-D and Table 1) and turbulence.18,19,24 Since shear stress varies spatially and temporally, the volume distribution is presented in the figure. Since axial pump performance is sensitive to the incoming flow direction an initial stationary guide vane straightens the flow proximal to a propeller (Figure 3A). Stationary outlet guide vanes convert kinetic energy to pressure and can lead to thrombosis due to flow separation.18 Centrifugal pumps have an impeller that pulls and expels blood radially, generating high pressure at lower flow rates (Figure 3B). Centrifugal pumps utilize a levitated rotor driven by electromagnetism with rotational speeds from 1500 to 3000 rpm and pressure heads of 65 to 285 mmHg (Figure 1C).19 Despite lower shear stress than axial pumps, it can exceed 500 dynes/cm2, transiently reaching up to 3200 dynes/cm2 (Figure 3C-D).21,23 The primary material for rotary pumps is a titanium alloy with an additional polyester outflow graft. A summary of reported shear stress values for the different pump types is provided in Table 1, noting that physiological shear stress remains below 72 dynes/cm2, substantially lower than rotary pumps, especially axial pumps, and pathological shear stress associated with atherosclerotic plaque prone to thrombosis can reach 400 dynes/cm2, or even higher.12,13,25

Cartoon of pump attached to the heart relative to representative plots of pressure head (pressure difference between ventricle and greater vessel) and flow rate for various pump speeds. Pressure head is a term used for rotary mechanical pumps that quantitatively defines the pressure increase across the pump, that is, the pressure difference between the aorta and left ventricle for an LVAD. (A) A volume displacement pump: flow rate is driven relatively independently of the pressure head. (B) Axial rotary pumps: for a rotary pump the relationship between pressure head and flow rate depends on the pump style and speed. An axial pump with a pressure head, P1 and a specific rotor speed (separate curves), the flow rate through the pump is Q1. If pressure in the aorta increased, for example, through an increased peripheral vascular resistance, this would lead to an increase in pressure head, P2, leading to a decrease in flow rate for the axial pump, Q2. (C) Centrifugal rotary pumps produce high pressures at lower flow rates when compared to axial pumps, with the pressure head being driven by the rotational speed of the impeller, which may go from 1500 to 3000 rpm for pressure heads of 65 to 285 mmHg.

Cartoon of pump attached to the heart relative to representative plots of pressure head (pressure difference between ventricle and greater vessel) and flow rate for various pump speeds. Pressure head is a term used for rotary mechanical pumps that quantitatively defines the pressure increase across the pump, that is, the pressure difference between the aorta and left ventricle for an LVAD. (A) A volume displacement pump: flow rate is driven relatively independently of the pressure head. (B) Axial rotary pumps: for a rotary pump the relationship between pressure head and flow rate depends on the pump style and speed. An axial pump with a pressure head, P1 and a specific rotor speed (separate curves), the flow rate through the pump is Q1. If pressure in the aorta increased, for example, through an increased peripheral vascular resistance, this would lead to an increase in pressure head, P2, leading to a decrease in flow rate for the axial pump, Q2. (C) Centrifugal rotary pumps produce high pressures at lower flow rates when compared to axial pumps, with the pressure head being driven by the rotational speed of the impeller, which may go from 1500 to 3000 rpm for pressure heads of 65 to 285 mmHg.

Pulsatile volume displacement pump. (A) Illustration of pulsatile volume displacement pump demonstrating how a typical pump works. Blood flow enters the pump as the flexible diaphragm/membrane is pulled downward in the image. This movement is driven by a pusher plate controlled by a motor. The mechanism varies, depending on the specific pump. With one-way valves at the inlet and outlet, this leads to fluid entering from the ventricle, while the outflow valve remains closed. Flow exits the pump as the pusher plate pushes upward, thereby deflecting the flexible diaphragm, which increases pressure within the pump. The pressure change closes the inflow valve and opens the outflow valve. Blood flow is then driven out of the pump. (B) The shear stress distribution within an example pediatric 15 cubic centimeter volume displacement pump during the ejection of blood from the pump.8 Note that shear stress is pump-specific and depends on the pump volume. It also varies in time and along the depth of the image.

Pulsatile volume displacement pump. (A) Illustration of pulsatile volume displacement pump demonstrating how a typical pump works. Blood flow enters the pump as the flexible diaphragm/membrane is pulled downward in the image. This movement is driven by a pusher plate controlled by a motor. The mechanism varies, depending on the specific pump. With one-way valves at the inlet and outlet, this leads to fluid entering from the ventricle, while the outflow valve remains closed. Flow exits the pump as the pusher plate pushes upward, thereby deflecting the flexible diaphragm, which increases pressure within the pump. The pressure change closes the inflow valve and opens the outflow valve. Blood flow is then driven out of the pump. (B) The shear stress distribution within an example pediatric 15 cubic centimeter volume displacement pump during the ejection of blood from the pump.8 Note that shear stress is pump-specific and depends on the pump volume. It also varies in time and along the depth of the image.

Rotary pumps. (A) Illustration of an axial pump, where flow is driven past a straightener consisting of stationary vanes, enters the rotor region that pushes blood through the pump, before it exits the diffuser that contains additional stationary guide vanes. The rotor rotates along mechanical bearings in second-generation devices and is magnetically levitated and driven in third-generation devices. (B) Illustration of centrifugal pump, where the impeller rotates along mechanical bearings in second-generation devices or with magnetic levitation in third-generation devices. The rotation of the impeller pulls blood through the inlet port and expels/throws it radially outward based on guidance of vanes/channels, as it subsequently travels through a volute until it reaches the outlet port. An example cross section is shown for the HeartMate III with an image taken from the instruction manual provided by Abbott. (C) Flow simulations through an axial pump, the Heartmate II (HMII) and a retired centrifugal pump, the Heartware ventricular assistance device (HVAD). Flow streamlines (or paths) are shown to demonstrate how flow travels through each type of pump.15 The color is the speed of the blood as it travels through the pump, with a corresponding legend provided in the figure. A plot is also shown that shows the volume distribution of shear stress, that is, how much volume of fluid in each pump experiences a particular shear stress range (1 Pa = 10 dynes/cm2).15 The shear stress in the HM2 is comparable to the HVAD. (D) The wall shear stress distribution is shown for both a axial flow HMII and a centrifugal flow HM3.16 Shear stress relative to fluid volume is also shown for these simulations.16 Overall shear stress is higher in the axial flow HMII. It becomes very high along the rotor surface (up to 6000 dynes/cm2), but as demonstrated by the volume to shear stress plot, this does not extend far into the fluid.

Rotary pumps. (A) Illustration of an axial pump, where flow is driven past a straightener consisting of stationary vanes, enters the rotor region that pushes blood through the pump, before it exits the diffuser that contains additional stationary guide vanes. The rotor rotates along mechanical bearings in second-generation devices and is magnetically levitated and driven in third-generation devices. (B) Illustration of centrifugal pump, where the impeller rotates along mechanical bearings in second-generation devices or with magnetic levitation in third-generation devices. The rotation of the impeller pulls blood through the inlet port and expels/throws it radially outward based on guidance of vanes/channels, as it subsequently travels through a volute until it reaches the outlet port. An example cross section is shown for the HeartMate III with an image taken from the instruction manual provided by Abbott. (C) Flow simulations through an axial pump, the Heartmate II (HMII) and a retired centrifugal pump, the Heartware ventricular assistance device (HVAD). Flow streamlines (or paths) are shown to demonstrate how flow travels through each type of pump.15 The color is the speed of the blood as it travels through the pump, with a corresponding legend provided in the figure. A plot is also shown that shows the volume distribution of shear stress, that is, how much volume of fluid in each pump experiences a particular shear stress range (1 Pa = 10 dynes/cm2).15 The shear stress in the HM2 is comparable to the HVAD. (D) The wall shear stress distribution is shown for both a axial flow HMII and a centrifugal flow HM3.16 Shear stress relative to fluid volume is also shown for these simulations.16 Overall shear stress is higher in the axial flow HMII. It becomes very high along the rotor surface (up to 6000 dynes/cm2), but as demonstrated by the volume to shear stress plot, this does not extend far into the fluid.

Shear stress for different pump types compared to typical range of shear stresses in blood vessels

| Pump . | Examples . | Maximum shear stress (dynes/cm2) . |

|---|---|---|

| Typical range of wall shear stress in blood vessels17 | Large arteries | 14-36 |

| Arterioles | 20-72 | |

| Veins | 0.7-9 | |

| Stenotic vessels | 36-450 | |

| Positive displacement | Heartmate I | 100-5008-10,18 |

| Thoratec PVAD | ||

| Novacor N100 | ||

| Rotary axial | Heartmate II | 2 000-24 00015,16,19,20 |

| Jarvik 2000 | ||

| Micromed DeBakey | ||

| Rotary centrifugal | DuraHeart | 500-3 20015,16,21,22 |

| Heartware VAD (HVAD) | ||

| Levacor | ||

| HeartMate 3 |

| Pump . | Examples . | Maximum shear stress (dynes/cm2) . |

|---|---|---|

| Typical range of wall shear stress in blood vessels17 | Large arteries | 14-36 |

| Arterioles | 20-72 | |

| Veins | 0.7-9 | |

| Stenotic vessels | 36-450 | |

| Positive displacement | Heartmate I | 100-5008-10,18 |

| Thoratec PVAD | ||

| Novacor N100 | ||

| Rotary axial | Heartmate II | 2 000-24 00015,16,19,20 |

| Jarvik 2000 | ||

| Micromed DeBakey | ||

| Rotary centrifugal | DuraHeart | 500-3 20015,16,21,22 |

| Heartware VAD (HVAD) | ||

| Levacor | ||

| HeartMate 3 |

The first approved TAH is SynCardia, an updated version of Liotta, Jarvik-7, Symbion, and Cardiowest TAHs.5,6 It is a pulsatile TAH with long-term support exceeding 5 years. TAHs are volume displacement pumps, providing high cardiac output (up to 9 L/min) with normal pressures. Biocompatible polyurethane ventricles replace native ones, having a total displacement volume of around 400 cm3. The rate adjusts to fill 50 to 60 mL in each cycle for the 70-mL version and 30 to 40 mL for the 50-mL version. Healthy ventricle volume is ∼78 cm3/m2 or around 140 cm3 for an average person. The typical device rate is 125 beats per minute, resulting in cardiac outputs of 6.3 to 7.5 L/min and 3.8 to 5.1 L/min for 70 and 50 mL SynCardia versions, respectively. Another TAH currently in use is the Aeson bioprosthetic artificial heart (Figure 4A). A hybrid membrane divides each ventricle into a blood compartment and an actuating liquid compartment. The blood-contacting layer of this membrane consists of bovine pericardial tissue chemically treated with glutaraldehyde.7 The principal pump shuttles the actuating liquid between the right and left ventricles, pulling and pushing the hybrid membranes, ensuring full ejection of the blood cavities to avoid stasis. The beat rate ranges from 30 to 150 beats per minute, with a maximum stroke volume of 65 mL. A fluid structure interaction model shows that shear stress is below 10 dynes/cm2 for 90% of the flow, with a maximal value approaching 1500 dynes/cm2 for <0.001% of the flow.7,26 A fluid structure interaction couples the stress produced between a moving solid structure and fluid, thus enabling the quantification of forces endured by the bloodstream inside an A-TAH. A-TAH is currently used clinically in auto mode to provide a mechanism for adapting pump outputs to the daily activities of patients and returning to circadian pattern of hemodynamic function.27 Hemodynamic data extracted from the pivotal study showed that autoregulated A-TAHs have good physiologic responses according to venous return. The A-TAH uses embedded pressure sensors to govern pump output. Right and left ventricular outputs are spontaneously balanced. The operator sets target values, and the A-TAH algorithm sets stroke volume and beat rate, and thus, cardiac output. Patients have a range of average inflow pressures between 5 and 20 mmHg during their daily activities, resulting in a cardiac output between 4.3 and 7.3 L/min.28

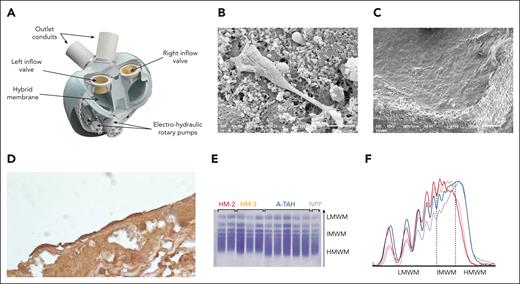

The A-TAH is a hemocompatible device. (A) All A-TAH components, except external batteries, are embodied in a single device, mimicking the normal heart. Electrical-hydraulic rotary pumps activate silicone oil, deploying back and forth hybrid membranes. Endothelial recovery of explanted glutaraldehyde–treated membranes of ventricle in feasibility study. Electron microscopy showed pseudotube formations on this fibrin cap observed in a patient 72 days postimplantation. (B) There was a genuine endothelial covering of the cap in a patient with 270 days of implantation (C). (D) All of the membranes show cells with an endothelial phenotype confirmed by immunohistochemical labeling for VE-cadherin (CD144). (E) Representative VWF multimers contained in plasma samples from patient on HMII, HM3, or A-TAH were detected using the semiautomated Hydragel von Willebrand multimers assay kit (Hydrasis 2 Scan instrumentation, Sébia). Plasma pooled from healthy subjects was examined as standard reference. (F) Multimers densitometry from left low molecular weight multimers (LMWM, peaks 1-5) to the right high molecular weight multimers (HMWM, peaks over 10). Intermediate molecular weight VWF multimers (IMWM) are peaks 6 to 10. VWF multimers from healthy volunteer is indicated by a solid black line, A-TAH samples are in blue, while HMII and HM-3 are respectively in red and orange.

The A-TAH is a hemocompatible device. (A) All A-TAH components, except external batteries, are embodied in a single device, mimicking the normal heart. Electrical-hydraulic rotary pumps activate silicone oil, deploying back and forth hybrid membranes. Endothelial recovery of explanted glutaraldehyde–treated membranes of ventricle in feasibility study. Electron microscopy showed pseudotube formations on this fibrin cap observed in a patient 72 days postimplantation. (B) There was a genuine endothelial covering of the cap in a patient with 270 days of implantation (C). (D) All of the membranes show cells with an endothelial phenotype confirmed by immunohistochemical labeling for VE-cadherin (CD144). (E) Representative VWF multimers contained in plasma samples from patient on HMII, HM3, or A-TAH were detected using the semiautomated Hydragel von Willebrand multimers assay kit (Hydrasis 2 Scan instrumentation, Sébia). Plasma pooled from healthy subjects was examined as standard reference. (F) Multimers densitometry from left low molecular weight multimers (LMWM, peaks 1-5) to the right high molecular weight multimers (HMWM, peaks over 10). Intermediate molecular weight VWF multimers (IMWM) are peaks 6 to 10. VWF multimers from healthy volunteer is indicated by a solid black line, A-TAH samples are in blue, while HMII and HM-3 are respectively in red and orange.

MCS-associated complications

Pump-related complications are closely related to changes in hemodynamics and their effects on blood cells and plasma proteins.

Pump thrombosis

The Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) defined pump thrombosis as follows: clinical and biochemical markers are (1) lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) >2.0 times upper limit of normal, (2) plasma-free hemoglobin >40 mg/dL, (3) hemoglobinuria, (4) altered pump parameters, (5) abnormal pump sounds, and (6) organized fibrin in inlet after explantation.29 Initial pivotal trial and later post-marketing approval studies30-32 reported an incidence of pump thrombosis with Heartmate2 (HMII) between 2% and 4%, with 0.03 events per patient per year (EPPY; 0.03 EPPY would be multiplied by 100 patients to get the number patients out of 100 experiencing an event on average per year, which would be equivalent to 3% per year) at 1 year of follow-up during the bridge-to-transplant clinical trial,32 0.024 EPPY at 2 years during the destination therapy trial31 and 0.038 EPPY in the additional 281-patient registry.33 However, real-world data signaled a significant increase in pump thrombosis in HMII after 2011 with rates up to 8.4% at 3 months34 and 6% at 6 months post implant,35 and once more data were made available, ultimately pump thrombosis was estimated in 18.6% and 17.9% in the first 2 years and in the following 5 years after implant, respectively.36 The third-generation pump design (ie, HM3) has significantly reduced the rate of pump thrombosis as reported in the Momentum 3 trial37 and is currently estimated between 1.2% and 2.8% for the first 2 years and between the third and fifth year post implant.36 Patients are maintained on a similar antithrombotic regimen based on aspirin, at a dose of 81 to 325 mg daily and warfarin, with the target range of the international normalized ratio (INR) at 2.0 to 3.0 (Table 2). In the rare eventuality that pump thrombosis does occur surgical pump exchange remains the definite treatment for pump thrombosis.1 Medical management for LVAD thrombosis remains controversial38 because efficacy is not based on randomized clinical studies and might be an option as a temporary measure, as a bridge-to-transplant, or as a palliative measure in patients not deemed suitable for surgical intervention. In a recent case series of 26 patients with pump thrombosis, thrombolytic therapy alone was only successful in 11.5% of patients (n = 3), whereas 69.2% of them (n = 18) ultimately required a device exchange, despite an initial and significant improvement in plasma-free hemoglobin and LDH.39 Earlier series from the HMII experience support the limited efficacy of medical management for the treatment of LVAD thrombosis: among 40 thromboses in 40 patients who did not undergo transplantation or pump replacement, actuarial mortality was 48.2% (95% confidence interval, 31.6-65.2) in following 6 months after the initial diagnosis.34 Limited histologic reports on clots retrieved post-LVAD implants40 suggest a clot heterogeneity that may explain the real-life limited response to TPA in clinical settings. If successful (ie, resolution of power spike with normalization of LDH and plasma-free hemoglobin levels) patient should be treated with higher anticoagulation targets (ASA 325 mg/d and INR 2.5-3, with possible second antiplatelets agent). A number of patient-related factors were identified to be associated with pump thrombosis: younger age, White race, higher body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) >20%, and hemolysis quantified as LDH levels higher than 500 units per dL for >1 month.34,35

First, hemolysis in MCS can contribute to thrombosis through plasma-free hemoglobin. There is also evidence that free hemoglobin can bind to von Willebrand factor (VWF), which increases affinity for binding to platelet GPIbα.41 This could enhance VWF-dependent platelet adhesion and aggregation. It is found in ∼2% of patients on LVAD support42 and is generally considered to be caused by red blood cells reaching a threshold level of physical strain.43-45 Hemolysis occurs in <1.4% of patients with an A-TAH and appears not to be associated with the device itself.46,47 Second, endothelial dysfunction is a key proponent for thrombosis through multiple pathways. In LVADs, endothelial dysfunction has been described after implantation; however, differences in control groups give rise to conflicting results and interpretation.48-52 Loss of pulsatile in LVAD flow has been shown to increase plasma levels of flow-sensitive miRNAs, which contribute to endothelial dysfunction.53-59 In A-TAH, endothelial dysfunction has been associated with the manual mode for A-TAH, potentially as a consequence of the vascular permeability associated with earlier A-TAH iteration, but it is not found when the A-TAH operates in an autoregulated mode used in pivotal study and in post-marketing studies.60,61 In the context of MCS, it has been demonstrated that pulsatility was the trigger of endothelial release of new VWF and counterbalance VWF degradation induced by the shear stress.62 Thus, by reversing endothelial phenotype with release of VWF, pulsatility can correct consequence of shear stress induced by continuous flow. Thrombosis with an A-TAH has not been reported in a preclinical study63 or in clinical trials.46,47,64,65 The A-TAH ventricles exhibit antithrombotic properties, as explanted A-TAHs exhibit no signs of thrombosis in cavities, which likely results from newly formed endothelial cells on hybrid membranes (Figure 4B-D).66 The endothelialization could be a result of circulating stem or progenitor cells being captured to the xenopericardial tissue.67,68 Finally, LVADs expose a large surface to blood, leading to plasma proteins adsorption, including fibrinogen, VWF, albumin, and coagulation proteins. Fibrinogen and VWF immobilization binds platelets.69 Proenzymes (factor XII [FXII], prekallikrein, and FXI) and kininogen initiate coagulation through the intrinsic pathway, generating FXIIa and active kallikrein on the LVAD surface.70,71 Moreover, in patients supported by LVADs exhibited chronic inflammation and immune dysfunction appears after implantation72-74 correlated with higher mortality.75-78 Increased levels of tumor necrosis factor α in LVAD patients has been proposed as a central regulator of both angiogenesis with pericyte apoptosis and suppression of angiopoietin-1.79 LVAD implantation has been found to be associated with neutrophil activation80-82 that have been have been recognized as integral players in the context of thrombosis.83

Bleeding

Early bleeding often results from surgical intervention, but LVAD–specific platelet dysfunctions84 and changes in the adhesive ligand VWF85 can also become apparent as early as 24 hours postimplantation.86 Real challenges arise in a significant subset of individuals who develop recurrent mucosal bleeding, which became immediately apparent as a relevant cause of morbidity for CF-LVADs during the clinical transition period from pulsatile devices. Gastrointestinal bleeding significantly increased from 0.068 EPPY in the pulsatile LVADs to 0.63 EPPY in CF-LVADs.87 Microscopic bleeding was found in 19% to 40% of patients supported by the CF-LVAD HMII30,88 and ∼30% of patients in the initial study for Heartware LVADs.89 A subsequent head-to-head comparison between HMII and Heartware LVADs shows similar rates of early- and late-bleeding complications.90 Gastrointestinal bleeding in patients on HM3 LVADs is reduced in comparison with those on HMII (Table 3). Bleeding can occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, but is most common in the upper GI tract in 35% to 50% of cases, lower GI source in 22%, and in the small bowel in ∼15% of bleeding events.92 Occult bleeding without an identifiable source is frequent and occurs in 20% to 44% of cases. Arteriovenous malformations are responsible for more than one-half of lesions, followed by gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. Other locations of mucocutaneous bleeding include nasopharyngeal bleeding, oral bleeding, and vaginal bleeding. Patients with blood group O have ∼25% lower VWF and FVIII levels than non-O patients (A, B, or AB) as previously reported by Gill et al,93 and not surprisingly, blood group O has been found to be significantly associated with a higher risk of bleeding (hazard ratio, 2.42; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-5.70; P = .044).94 As of today, warfarin remains the standard of care for LVAD anticoagulation while maintaining INR between 2 and 3. Limited evidence is available to lower INR targets in HeartMate 3 (ie, INR between 1.5 and 1.9)95 while ongoing trials are investigating the aspirin 100 mg daily vs placebo (eg, ARIES trial, NCT04069156).96 Blood products (DDAVP, cryoprecipitates, VWf concentrates) are rarely utilized and limited in life-threatening situations because of the concern of procoagulant rebound while patients remain on LVAD support. Multiple additional agents have been utilized based on limited evidence and are not currently endorsed by best practice guidelines97-99 Because of drastically elevated shear stress in LVAD-driven blood, efforts to identify the underlying causes of LVAD-induced mucosal bleeding have quickly been focused on VWF and its interaction with platelets. VWF changes associated with LVAD implantation are collectively termed aVWS,100 a condition that is originally found in patients with aortic valve stenosis (Heyde syndrome).101 LVAD-associated aVWS is defined by a lack of large VWF multimers and reduced adhesive activity in peripheral blood samples from patients on LVAD supports. It develops soon after LVAD implantation,102 resolves rapidly after LVAD explantation103 and is not observed in heart transplant recipients,100 suggesting that it is caused by hydrodynamic changes induced by the mechanical device. Indeed, high molecular weight multimer loss in human blood after implantation of LVADs has been observed after initiating the pump after 5 minutes and their quick recovery was observed in a rabbit model of reversible arterial stenosis.102 aVWS could be caused by high shear stress (force per unit area to slide 1 layer of fluid over another), elongational flow (flow gradients in the direction of flow), reduced pulsatility, or flow turbulence.62 One widely held belief is that high shear stress in LVAD-driven blood flow causes aVWS by increasing VWF cleavage by the metalloprotease ADAMTS-13. However, this tentative mechanism is not fully supported, and several significant gaps remain. First, aVWS is observed in nearly all patients, but only 10% to 20% of patients bleed.90 Second, high shear stress is known to induce VWF cleavage by ADAMTS-13,104,105 which reduces VWF adhesive activity, but it was also shown to activate VWF to bind platelets long before ADAMTS-13 was discovered.12,106,107 Both cleavage and activation of VWF multimers can be induced in vitro at ∼100 to 800 dynes/cm2 of shear stress,45,108-111 raising questions as to how the 2 opposing processes reach an equilibrium state in healthy subjects and whether this VWF homeostasis is disrupted in LVAD–derived blood flow. Finally, excessive VWF cleavage has never been directly detected in peripheral blood samples from patients on LVAD supports using conventional laboratory assays. This is because these conventional assays measure VWF cleavage by non- or semi-quantitative immunoblot,112 by surrogate markers, such as VWF binding to collagen112 and levels of ADAMTS-13 antigen, or by the cleavage of a recombinant 73-mer peptide from the VWF A2 domain.113,114 The peptide cleavage assay is quantitative, but it does not measure the cleavage of VWF in patients on LVAD support. Several lines of evidence suggest that VWF in LVAD patients is more likely to be activated than being excessively cleaved. High shear stress unfolds VWF for oxidation115 in the oxidative stress environment found in LVAD patients.78,116,117 The methionine oxidation makes VWF resistant to cleavage115,118 and ADAMTS-13 less active in cleaving VWF.119 (2) LVADs often induce hemolysis to release hemoglobin, which binds VWF and blocks its cleavage by ADAMTS-13.109,120 The A1 and A2 domains of plasma VWF form a complex during homeostasis to prevent VWF from activating platelets or being cleaved by ADAMTS-13.121 A1-A2 dissociation exposes A1 for binding platelets122 and induces accumulation of hyperadhesive VWF in the circulation.115,118 There is a significant increase in circulating levels of VWF-bound extracellular vesicles from platelets in the peripheral blood of LVAD patients,123 suggesting that VWF is activated to bind and activate platelets. An interesting note is that these platelet-derived and VWF-bound extracellular vesicles promote aberrant angiogenesis,123 which is the structural basis of angiodysplasia that develops in the gastrointestinal tract and other mucosal tissues of patients on LVAD supports and is a common site of post-LVAD bleeding.124 Together, these observations demonstrate the importance of quantifying VWF activity and cleavage in LVAD patients. We have developed a mass spectrometry method to quantify VWF cleavage by detecting the ADAMTS-13-cleaved tryptic peptides EQAPNLVY or MVTGNPASDEIK from the A2 domain. Using this method, we have shown that VWF multimers are excessively cleaved in some patients but activated to bind platelets in most patients on LVAD supports.114,123,125 This assay may be used to refine the contribution of VWF cleavage to the development of aVWS and clinical bleeding in patients on LVAD supports in large clinical studies.

Current recommendation of antithrombotic treatments in LVAD and TAH

| . | Antithrombotic treatment . | Initiation . | Duration/survey . |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVAD | UFH | As soon as drains allow anticoagulation | Stop when INR > 2 |

| Warfarin | After drain removal | 2 < INR < 3 long-term treatment | |

| Aspirin | Around day 2 | Long-term treatment | |

| SynCardia | UFH | After surgery as soon as possible | Stop when INR >2 |

| Warfarin | After drain removal | 2.5 < INR < 3.5 long-term treatment | |

| Aspirin | Around day 2 | Long-term treatment | |

| Aeson | UFH | As soon as drains allow anticoagulation | Anti-Xa around 0.2 until drain removal |

| LMWH | After drain removal | No biological follow-up long-term treatment | |

| Aspirin | At least 4 d after drain removal | Long-term treatment |

| . | Antithrombotic treatment . | Initiation . | Duration/survey . |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVAD | UFH | As soon as drains allow anticoagulation | Stop when INR > 2 |

| Warfarin | After drain removal | 2 < INR < 3 long-term treatment | |

| Aspirin | Around day 2 | Long-term treatment | |

| SynCardia | UFH | After surgery as soon as possible | Stop when INR >2 |

| Warfarin | After drain removal | 2.5 < INR < 3.5 long-term treatment | |

| Aspirin | Around day 2 | Long-term treatment | |

| Aeson | UFH | As soon as drains allow anticoagulation | Anti-Xa around 0.2 until drain removal |

| LMWH | After drain removal | No biological follow-up long-term treatment | |

| Aspirin | At least 4 d after drain removal | Long-term treatment |

LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; UFH, unfractionated heparin; LVAD, left ventricular assistance device; INR, International normalized ratio.

Hemocompatibility-related adverse events in patients supported with magnetic levitated LVAD (HM3) vs Axial Flow LVAD (HMII) based on MOMENTUM 3 data at 2 and 5 years

| . | Heartmate II . | Heartmate 3 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strokes 2 y | 0.07 | 0.04 | .008 |

| Strokes 5 y | 0.136 | 0.05 | <.001 |

| Other neurologic events | 0.073 | 0.065 | .49 |

| Pump thrombosis 5 y | 0.108 | 0.010 | <.001 |

| Bleeding at 5 y | |||

| Any | 0.765 | 0.430 | <.001 |

| GIB | 0.423 | 0.252 | <.001 |

| . | Heartmate II . | Heartmate 3 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strokes 2 y | 0.07 | 0.04 | .008 |

| Strokes 5 y | 0.136 | 0.05 | <.001 |

| Other neurologic events | 0.073 | 0.065 | .49 |

| Pump thrombosis 5 y | 0.108 | 0.010 | <.001 |

| Bleeding at 5 y | |||

| Any | 0.765 | 0.430 | <.001 |

| GIB | 0.423 | 0.252 | <.001 |

SynCardia patients often experience bleeding (up to 43% reported).6 In the study by Sénage et al, 22% needed surgery to stop bleeding, whereas in the study by Copeland et al, 25% had mediastinal explorations for hemorrhage.5,6 Bleeding usually occurs within 24 hours post implantation, with 44% mortality in reoperations. However, bleeding in A-TAH does not seem to be a significant outcome47 and ongoing clinical outcome trials may provide a more definitive conclusion. In contrast to the extensive studies on LVAD patients, there is limited and contradictory information on how TAH implantation affects VWF cleavage and activity. A study by Zieger et al noted the absence of acquired von Willebrand syndrome (aVWS) after SynCardia implantation,126 but 2 other studies show the loss of large VWF multimers in patients with SynCardia.127,128 aVWS has not been detected in preclinical or clinical studies on patients implanted with A-TAH in either manual62,66 or auto mode47 (Figure 4E-F). Consistent with these clinical observations, calves implanted with A-TAH have early hemostatic recovery and do not develop aVWS during a short follow-up period, even with the pump output up to 10 L/min.64 The role of platelet and VWF dysfunction in bleeding events after LVAD implantation is still under investigation and withdrawal of antiplatelet agent is currently being tested in the ARIES study (NCT04069156).96 Furthermore, anti-VWF antibody that partially blocked VWF-ADAMTS13 interactions and could prevent excessive degradation of high molecular weight VWF multimers, is also being investigated.129 Finally, the responsibility of anticoagulation in bleeding complications after LVAD or TAH implantation is crucial for managing these potential complications (Table 2). Current standard of care includes antiplatelet agent, such as acetylsalicylic acid and a vitamin K antagonist are used in therapeutic doses. A low intensity anticoagulation targeting an INR between 1.5 and 1.9 has been tested in the MAGENTUM 1 study (Minimal AnticoaGulation EvaluatioN To aUgment hemocompatibility) without any increase of thrombotic events.95,130 Thrombosis rates in SynCardia TAH are around 16% with high anticoagulation,131 whereas Aeson trials described no thrombosis, even with nontherapeutic anticoagulation.132

MCS–related cerebrovascular accidents

The 2022 INTERMACS reported overall 7% stroke rate in patients on durable LVAD in the first year with significant difference between different devices.2 Management in an LVAD patient is analog to non-LVAD patient with prompt imaging to determine the underlying nature. Anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy should be withheld until the hemorrhagic nature of the cerebrovascular lesion has been ruled out, while the decision of anticoagulation reversal should be entertained with neurology and neurosurgical evaluation on a case-by-case scenario owing to the limited data availability.133 Anticoagulation is usually reinstated to a lower INR target while antiplatelets is usually discontinued.134 The introduction of third-generation device (eg, HM3) has marked a significant reduction in stroke incidence, although it remains a significant cause of death in LVAD patient (19%)135 as described in Table 3. Stroke pathophysiology is still somehow elusive and it may result from concurrent factors, including intrinsic thrombogenicity of LVADs due to direct contact between blood and biomaterials, chronic anticoagulation in high-risk populations, and shear stress modifying rheology, red blood cells, platelets, and VWF. Surgical technique and anatomical variant in outflow graft position may play a role in further shear stress increase.136 Known risk factors for LVAD stroke are female sex, atrial fibrillation, history of stroke, hypertension, bacteremia, pump thrombosis, gastrointestinal bleeding and type of LVAD implanted.137 In addition, patients with advanced heart failure (ie, underlying condition for LVAD implantation) have an increased risk of stroke, estimated between 0.013 and 0.035 EPPY.138 A link between infection and stroke has been confirmed by Aggarwal et al,139 suggesting that a chronic hypercoagulable state can evolve into overt thromboembolic events in the presence of specific triggers (eg, infection). The trend toward a mild form of chronic anticoagulation targeting lower INR levels140 in patients on second-generation devices fell out favor after an abrupt increase in the incidence of pump thrombosis34,35 and in concurrent observation by Najjar et al.141

Conclusion

MCS and LVADs are essential tools for treating advanced heart failure. Thrombosis and bleeding complications have been the 2 major hurdles for patients requiring MCS. The increased hemocompatibility of new generations of LVADs would improve patient quality of life by reducing bleeding and thrombosis. Improved hemocompatibility has been achieved with new TAHs. Success will rely on the ability to maintain pulsatility of flow blood, limit supraphysiological shear stress and turbulence in new MCS design.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Jing-fei Dong from Bloodworks Research, University of Washington School of Medicine for working hard on this review. The authors thank Aurélien Philippe, Christophe Peronino, and Nicolas Gendron for the preparation of Figure 4. The authors also thank the Cellular and Molecular Imaging Platform (US25 INSERM, UAR3612 CNRS – Faculte de Pharmacie de Paris, Bruno Saubaméa, Universite Paris Cite, Paris, France) for technical help in histological analysis.

A.N. is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grant 1R01HL163549-01A1. D.B. is supported by grants from the NIH, NHLBI (R01HL164424), and the NIH, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (R21EB034579). D.M.S. is supported by grants from INSERM, Paris-Cité University and the Promex Stiftung für die Forschung.

Authorship

Contribution: A.N., D.B., and D.M.S. wrote sections of the manuscript; and all authors contributed to manuscript revision, and read and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.M.S. received consulting fees from CARMAT-SA. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David M. Smadja, European Georges Pompidou Hospital, INSERM Innovative Therapies in Haemostasis, 56 rue Leblanc, F-75015 Paris, France; email: david.smadja@aphp.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal